Abstract

Objective

To empirically investigate the ways in which patients and providers discuss Complementary and Alternative Medicine (CAM) treatment in primary care visits.

Methods

Audio recordings from visits between 256 adult patients aged 50 years and older and 28 primary care physicians were transcribed and analyzed using discourse analysis, an empirical sociolinguistic methodology focusing on how language is used to negotiate meaning.

Results

Discussion about CAM occurred 128 times in 82 of 256 visits (32.0%). The most frequently discussed CAM modalities were non-vitamin, non-mineral supplements and massage. Three physician–patient interactions were analyzed turn-by-turn to demonstrate negotiations about CAM use. Patients raised CAM discussions to seek physician expertise about treatments, and physicians adopted a range of responses along a continuum that included encouragement, neutrality, and discouragement. Despite differential knowledge about CAM treatments, physicians helped patients assess the risks and benefits of CAM treatments and made recommendations based on patient preferences for treatment.

Conclusion

Regardless of a physician's stance or knowledge about CAM, she or he can help patients negotiate CAM treatment decisions.

Practice implications

Providers do not have to possess extensive knowledge about specific CAM treatments to have meaningful discussions with patients and to give patients a framework for evaluating CAM treatment use.

Keywords: Discourse analysis, Primary care visits, Complementary medicine, Alternative medicine, Patient participation, Treatment decision making

1. Introduction

Complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) are increasingly being used to manage health problems [1,2]. However, physicians and patients do not consistently talk about CAM during office visits [3–6]. A recent U.S. national survey of people over 50 found that 47% were currently using some form of CAM, and of those only 58% had ever talked to a biomedical provider about their CAM use [4]. The primary reasons for not talking about CAM included the provider did not ask (42%) and patients did not know that they should talk about CAM (30%) [4]. In addition, many older patients do not see their biomedical health providers as important resources for CAM information and instead turn to friends, family, print resources, or the Internet [4].

CAM communication has been shown to improve provider–patient relationships [7,8] and shared decision-making [9], but little is known about how or why CAM conversations affect these outcomes. When CAM discussions occur, they are most often initiated by patients [5,10–12], especially by those who believe that their healthcare provider encourages active participation in medical decision-making [13,14]. Although patient initiations often lead to discussions about CAM use [10,11], physicians ignore as much as 28% of patient-initiated CAM discussions [11]. This raises concerns about missed opportunities for engaging patients about treatment preferences and health beliefs.

CAM communication research has mostly utilized patient and physician self-report methods and to our knowledge only three previous studies have used audio- or video-recorded physician–patient encounters to characterize actual CAM discussions [8,10,12]. Two of these direct observational studies were conducted with oncologists in Australia [11] and/or New Zealand [11], and one was with primary care physicians in the United States [12]. These studies indicate that CAM discussions are infrequent, occurring in 19–24% of oncology visits [11] and in only 10% of primary care visits with patients aged 50 and older [12]. Results from the study with primary care physicians may be limited because the data may be dated and may not reflect increased rates of CAM use in the older population [12]. All three direct observational studies employed content analysis to examine CAM conversations to describe the CAM modalities discussed [10,11] and to characterize patterns of physician–patient communication [10,11]. Collectively, these studies demonstrated that patients usually initiate CAM discussions [8,10,12], and that these discussions are initiated more often by statements rather than by asking direct questions [8,12]. Further, these studies show that physician responses to patient-initiated CAM discussion could be characterized as encouraging, neutral, discouraging, or disregarding [8,12]. While these studies provide some insight into patterns of CAM discussions between physicians and patients, neither do they examine how participants interactively negotiate the meaning of CAM treatment nor do they suggest how these negotiations might influence patient decisions about CAM treatments. An examination of actual turn-by-turn negotiations is needed to inform the role of physician–patient discussions on patient CAM decision-making.

This study uses discourse analysis to examine the communication dynamics between primary care physicians and older patients about CAM use. Older patients generally have more medical problems and, thus, have more potential for considering CAM treatments, and older patients view primary care providers as an important resource for healthcare decision-making [15–17]. The primary aim of the study is to examine the role of provider responses to patient-initiated CAM discussions about treatment decision-making. We also explored the ways in which physicians and older patients negotiate common understandings about CAM treatment decisions.

2. Methods

2.1.Data collection

As part of an intervention to improve communication about newly prescribed medications, 256 patient medical visits were audio-recorded with 28 primary care physicians (22 Internal Medicine and 6 Family Medicine) in Southern California, USA. Thirteen providers were practicing physicians, and 15 were resident physicians. All patients were aged 50 or older, spoke English, and had a new, worsening, or uncontrolled problem. The original purpose of the study was unrelated to CAM use. The University of California, Los Angeles institutional review board approved this study.

2.2. Discourse analysis

Discourse analysis (DA) is a qualitative sociolinguistic research methodology [18] that investigates the organization of social life through language use as social action [19–21]. Historically, DA has a long history studying healthcare settings [20–23]. Theoretically, DA prioritizes social context as a site for creating and interpreting meaning [19,24] and assumes that language does not simply reflect inner knowledge, attitudes, and beliefs, but rather through social interaction, participants' language use negotiates different types of meaning [19,25,26].

Methodologically, DA uses empirical materials, such as audiovisual recordings or textual documents, to show how participants manage multiple meanings in context. For example, when discussing CAM, patients can simultaneously express treatment preferences, demonstrate knowledge about alternative treatments, and solicit providers' professional opinions. Finally, DA recognizes that some meanings may be more explicit than others, depending on contextual features of the social situation [24,27,28].

To construct our analysis, all audio recordings were first transcribed verbatim (see Table 1 for transcript conventions) and all transcripts were loaded into Atlas.ti [29]. Each author read at least one-third of all transcripts to identify segments in which CAM modalities were discussed [19,25]. We identified CAM treatment modalities using criteria developed by the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) [4]. Next, the authors qualitatively examined the sequential organization around CAM mentions to understand how patients initiated CAM talk and how physicians responded, thereby demonstrating some orientation, or stance [30], to patient CAM use.

Table 1.

Transcription conventions.

| MD:/PT: | Speaker identifications are for physician (MD) and patient (PT). |

| wor- | Hyphens indicate a preceding sound is cut off or self-interrupted. |

| word. | Periods represent falling or turn-final intonation contours. |

| word, | Commas represent continuing or turn-continuative intonation contours. |

| word? | Question marks represent rising intonation contours. |

| ((word)) | Double parenthesis filled indicates transcriber's description or characterization of some event. |

Our interdisciplinary team included two experts in health communication (CJK, EYH) and one practicing family physician (DMT) who provided insight into the communicative ecology [19] of primary care. We met regularly to discuss observations and to develop preliminary collections of similar CAM discussion segments for systematic comparative analyses [19,31]. After reviewing all patient-initiated CAM talk, we created a comprehensive inventory of all provider responses. Because all responses could be understood as points along a continuum, we looked for critical cases [18] to show the most disparate points: encouraging, neutral, and discouraging responses. Finally, we reached consensus in selecting three concise cases that best illustrated the providers' response continuum.

The analysis focuses on patient-initiated CAM talk segments because patients initiated CAM talk more frequently than providers. Additionally, when patients initiate talk, such as asking questions about a CAM modality, providers may be normatively expected to respond [32], demonstrating a position, or stance [30], to it. Thus, patient-initiated CAM talk shows the turn-by-turn process in which the meaning of CAM use is interactively negotiated according to patient's current condition.

3. Results

The 256 patients in the study had a mean age of 64.8 (SD = 10.5), approximately 60% were Caucasian, and almost half were college graduates. Of these patients, 82 (32.0%) discussed at least one CAM modality during their office visit and 30 (11.7%) discussed two or more. There were no significant differences in age, gender, or race/ethnicity between those who discussed CAM during their visit and those who did not, but CAM discussions occurred more frequently in those who had more education (P < 0.01) (Table 2). Participants discussed a variety of CAM modalities with the most frequent mentions being about non-vitamin, non-mineral supplements (25%) and massage (13.3%) (Table 3).

Table 2.

Patient characteristics.

| Overall | No CAM discussion occurred | CAM discussion occurred | P-value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 256 | 174 | 82 | ||

| Mean age (SD) | 64.8 (10.5) | 65.4 (10.9) | 63.4 (9.6) | 0.17 |

| Female, % | 58.6% | 56.7% | 62.7% | 0.36 |

| Race/ethnicity, % | 0.71 | |||

| Caucasian | 60.2% | 57.8% | 66.7% | |

| African-American | 16.0% | 17.9% | 12.3% | |

| Hispanic | 9.0% | 9.3% | 8.6% | |

| Asian | 7.0% | 7.5% | 6.2% | |

| Other | 7.8% | 7.5% | 6.2% | |

| Education, % | <0.01 | |||

| High school or less | 17.7% | 22.5% | 7.3% | |

| Some college | 33.3% | 30.1% | 40.2% | |

| College graduate | 49.0% | 47.4% | 52.4% | |

| # previous visits to doctor seen, % | 0.28 | |||

| Never | 14.8% | 11.7% | 21.0% | |

| 1–2 times | 14.4% | 13.6% | 16.1% | |

| 3–5 times | 20.2% | 21.0% | 18.5% | |

| 6–12 times | 19.7% | 22.2% | 14.8% | |

| >12 times | 30.9% | 31.5% | 29.6% |

P-value comparing patients who did and did not discuss CAM during their office visit.

Table 3.

Types of CAM therapies.

| Type of CAM therapy | n |

|---|---|

| Alternative medical systems | 22 (17.2%) |

| Acupuncture | 12 (9.4%) |

| Homeopathy | 1 (0.8%) |

| Integrative medicine clinica | 9 (7.0%) |

| Biologically based therapies | 57 (44.5%) |

| Folk medicine/home remedies | 12 (9.4%) |

| Non-vitamin, non-mineral supplements | 32 (25%) |

| Non-vitamin, non-mineral natural product | 5 (3.9%) |

| Diet-based | 8 (6.2%) |

| Manipulative and body based therapies | 29 (22.7%) |

| Acupressure/pressure points | 1 (0.8%) |

| Chiropractic care | 10 (7.8%) |

| Massage | 17 (13.3%) |

| Pilates | 1 (0.8%) |

| Mind-body therapies | 20 (15.6%) |

| Yoga | 9 (7.0%) |

| Tai Qi | 2 (1.6%) |

| Relaxation techniques | 2 (1.6%) |

| Other mind-body therapiesb | 7 (5.4%) |

| Total | 128 |

‘Integrative medicine clinic' is the pseudonym used for a CAM clinic that is associated with the medical system where this study took place.

Other mind-body therapies include biofeedback, guided imagery, deep breathing, music therapy, and other spiritual health practices.

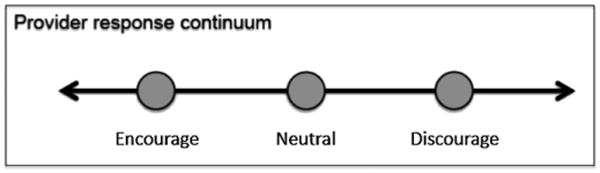

How a provider responded to patient-initiated CAM discussion was key for how participants negotiated CAM treatment. Providers adopted a range of responses, which we conceptualized as focal moments along a continuum (see Fig. 1). In the following sections, we present case studies from different physicians to illustrate three key responses – encouragement, neutrality, discouragement – in which providers interactively negotiate the appropriateness of CAM use for each patient's unique therapeutic needs. We did not analyze segments in which physicians ignored patient-initiated CAM talk because disattentive responses aborted further discussion, and thus oped out of negotiation about CAM use.

Fig. 1.

In response to patient-initiated CAM mentions, we conceptualize providers enacting their stance along a continuum. The three points (Encourage, Neutral, and Discourage) represent key responses where provider and patient interactively negotiate the meaning of CAM use.

3.1. Encouraging CAM use

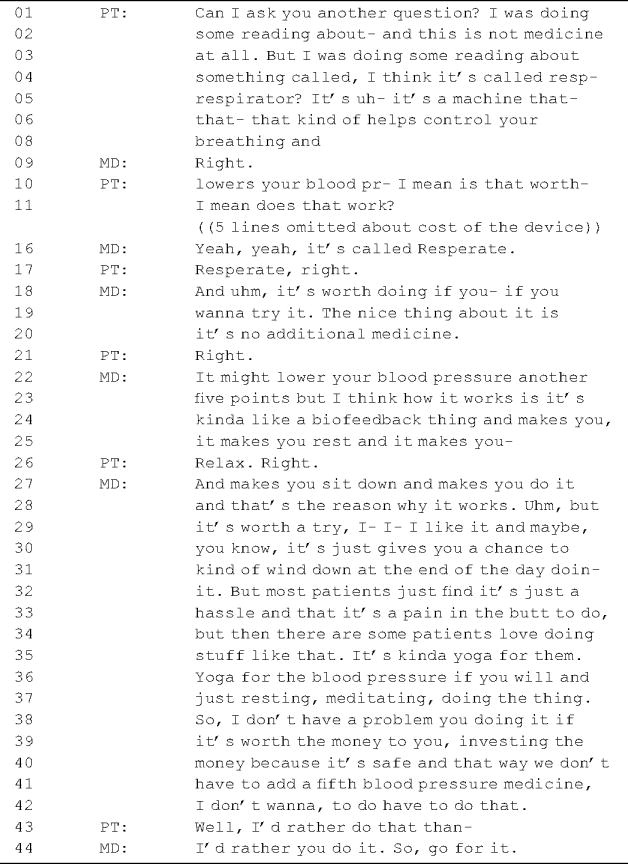

One physician stance toward CAM talk is to encourage patient CAM use by validating a CAM modality as a good treatment option. When physicians adopt an encouraging response, they may explicitly endorse CAM based on patients' specific clinical conditions, as the following extract shows. In this visit, a patient with hypertension asks about a CAM device that lowers blood pressure through a combination of conscious breathing and biofeedback (Table 4).

Table 4.

Extract 1. Resperate.

|

In this extract, the patient initiates CAM discussion by asking a direct question (line 01) framed as CAM-related talk (lines 02–08). Next, the patient asks, “I mean is that worth- I mean does that work?” (lines 10–11). In response, the physician identifies (line 16) and affirms the efficacy of the CAM product (lines 18–20), and he suggests that an additional benefit to using the product is no additional medication (lines 19–20), which may be necessary without using it (lines 40–42). Further, the physician estimates the device's impact on the patient's blood pressure (lines 22–23) and explains how the CAM modality works (lines 23–25, 27–32). While the physician encourages the patient to try it, he acknowledges potential differences in patient preferences: while most patients find this type of CAM treatment a hassle (line 32–33), “some patients love doing stuff like that” (lines 34–35). Finally, the physician recommends the CAM product (line 38), but leaves the final decision up to the patient to weigh the cost of the device (lines 39–40) against the benefit of avoiding additional medication (lines 40–42). The patient agrees to try the device (line 43), which the physician supports (line 44).

This extract demonstrates that physicians can encourage patient CAM use by orienting to the CAM modality as appropriate and potentially helpful for the patient's medical condition. When physicians encourage CAM use, they may explicitly recommend using a CAM modality by helping patients weigh the costs, benefits, and possible risks of using a CAM treatment. In this extract, if the patient uses the CAM treatment, he may obtain better blood pressure control and avoid taking additional medication. This physician is explicit in stating his recommendation in support of using the CAM device, but he is careful not to overstsate either the evidence for or the drawbacks against this complementary treatment. Instead, he helps the patient to negotiate a treatment decision by explicitly discussing the patient's preferences, financial means, and willingness to comply with the CAM treatment.

3.2. Neutral response to CAM use

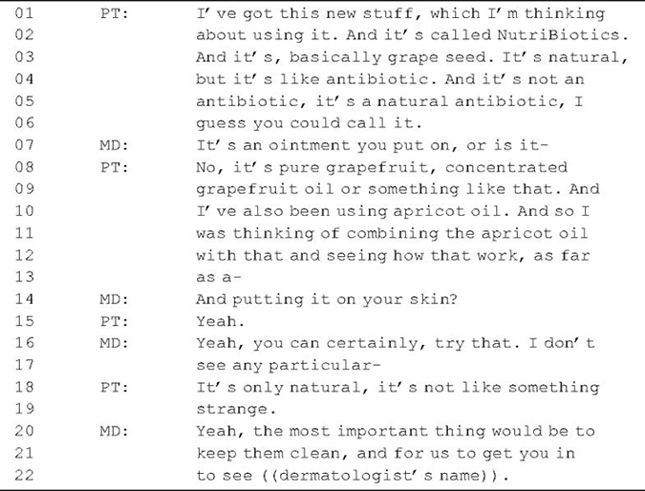

Providers can also adopt a neutral stance towards patient-initiated CAM talk. In these cases, providers do not give concrete recommendations about CAM use. Rather, a neutral stance may orient to CAM treatment as neither harmful nor helpful in managing a patient's health, as Extract 2 shows. In this visit, the patient presents long-standing painful skin lesions for which the physician recommends a dermatology referral. In response, the patient announces that he is considering a natural CAM product to help manage the problem (Table 5).

Table 5.

Extract 2. NutriBiotics.

|

By mentioning the CAM product, the patient solicits the physician's advice (lines 01–02), thereby opening an opportunity for the physician to help the patient negotiate a decision about using CAM as an alternative treatment. The physician responds by soliciting two additional pieces of information about the product, specifically, its form (line 07) and where the product is administered (line 14). Next, the physician adopts a neutral stance towards the patient's prospective CAM use, “you can certainly try that. I don't see any particular” (lines 16–17). Note that the physician has an opportunity to recommend for or against the CAM product, but he declines doing so by suggesting the CAM product is generally non-problematic. In response, the patient invites additional talk about the CAM product, “It's only natural, it's not like something strange” (lines 18–19). This may be an attempt to solicit a more explicit stance while simultaneously implying the CAM modality is acceptable because of its natural origin. Rather than provide a more concrete recommendation, the physician remains neutral about the CAM product and focuses instead on counseling the patient in the care of his condition until the future dermatology appointment (lines 20–22).

This extract shows that physicians can adopt a neutral stance towards patients' CAM use by orienting to the CAM as neither harmful nor helpful for the patient's condition. When physicians do not explicitly articulate a recommendation for or against the CAM product (e.g. “you can certainly try”), patients must decide themselves whether to use the CAM treatment without the benefit of the physician to help negotiate the decision.

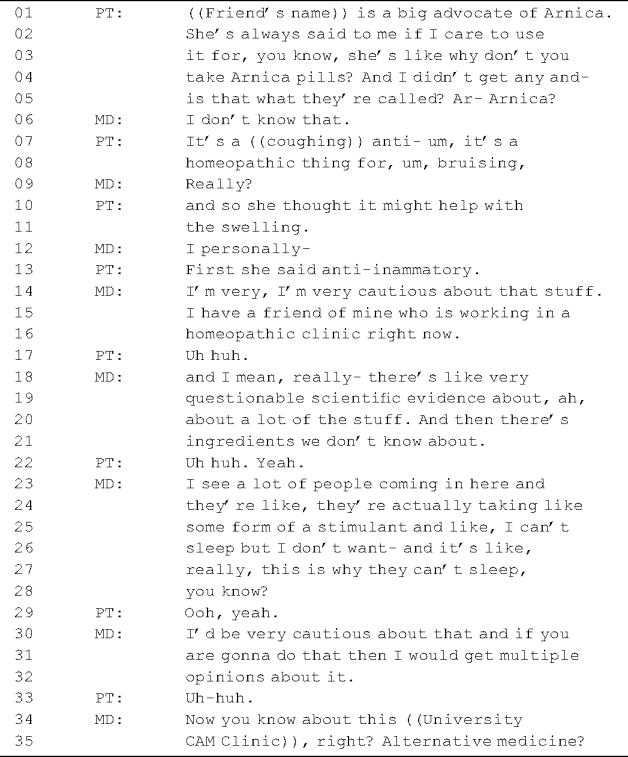

3.3. Discouraging CAM use

Finally, providers can discourage patients from using a CAM modality. When physicians adopt a discouraging stance, they may use their medical authority to advocate against CAM treatments in favor of more familiar treatment forms, as Extract 3 shows. In this visit, the patient complains about having swollen, painful hands. When the physician solicits more information, the patient initiates talk about a homeopathic CAM product, Arnica (lines 01–06) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Extract 3. Arnica.

|

The patient initiates discussion by stating that a friend encouraged her to use it (lines 01–04). Through this initiation, she orients to the physician as a health expert (line 05), inviting her help in understanding this CAM treatment form. When the physician disavows knowledge of the product (line 06), the patient provides more explanation about it, its typical use, and its reported benefits (lines 07–08, 10–11).

In response, the physician initially adopts a cautious stance (line 14). To support that stance, she similarly invokes a friend who works at a homeopathic clinic (lines 15–16) and offers two reasons for caution about homeopathic products: questionable scientific evidence (lines 18–20) and unknown ingredients (lines 20–21). Additionally, the physician typifies her own clinical experience with a story about patients who experience side effects when taking CAM products (lines 23–27). The implication is that patients taking CAM products may sometimes experience unwanted and unintended effects due to unknown ingredients. Based on her clinical experience, the physician discourages the patient from using the product based on evidence and personal experience (line 30). However, recognizing the patient's interest in CAM (lines 30– 31), the physician offers a different CAM resource (lines 34–35). This suggests that although the physician discourages one CAM modality, she does not necessarily adopt an overall discouraging stance towards CAM use. At the end of this exchange, it is not clear whether the patient will try the CAM treatment recommended by her friend, choose the CAM clinic based on the physician's recommendation, or do both.

This extract shows that physicians can discourage patient CAM use by orienting to the CAM modality as inappropriate or potentially harmful for the patient's medical condition while still acknowledging patient preferences. When physicians discourage CAM use, they may explicitly recommend against using a CAM modality by providing reasons and explanations about possible risks associated with CAM use. In this extract, the physician discourages CAM use due to lack of general scientific evidence base, lack of knowledge about ingredients in homeopathic CAM remedies, and her own clinical experience. Providing an explicit recommendation and explanation enables the patient to understand the basis behind the physician's recommendation and to take those reasons into consideration when making treatment decisions about CAM use.

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

This study used discourse analysis to illustrate physician–older patient negotiations about CAM use as a viable treatment option. We showed that provider responses and the stances they embodied (encouragement, neutrality, or discouragement) are key to the negotiation of patient treatment decisions. In each of the cases analyzed, patients raised CAM discussions to seek physician expertise about using CAM treatments. This suggests that patient-initiated CAM prevalent in many studies [5,10–12] may be either explicit or implicit requests for advice about CAM treatment decisions, and may invite substantive provider responses.

Regardless of a physician's stance toward a specific CAM modality, CAM discussions can help patients negotiate treatment decisions more generally. As both the encouraging and discouraging cases demonstrated, providers can help patients assess the risks and benefits of CAM treatments and make informed decisions about CAM use (e.g. safety, efficacy, mechanism of action, cost). Further, through these discussions physicians can also explore patient treatment preferences, which previous research has suggested is important in CAM communication [8,33,34]. When adopting a neutral stance towards CAM use, physicians leave the door open to CAM use without explicit encouragement or discouragement. When discouraging CAM use, physicians can affirm a patient's interest to try CAM by endorsing alternative treatment options, regardless of whether they are related to CAM or biomedicine. The encouraging and discouraging cases show that CAM conversations can perform a variety of functions, such as creating collaborative decision-making and honoring patient beliefs and treatment preferences. These types of negotiations have been shown to help patients better manage the uncertainty of their healthcare and ongoing illness trajectories [34,35].

Although physicians may not always have sufficient knowledge to help patients fully evaluate CAM treatment [36–38], through their responses they can help orient patients about the process of evaluating the risks and benefits of treatments and provide resources about where to seek additional information about CAM modalities. Previous research has shown that physicians want more education about CAM [6,38–40] and physicians may discourage patient CAM use due to lack of knowledge about safety and efficacy of CAM [38]. However, this study suggests that there are ways in which physicians may use the knowledge that they do have to help patients make informed decisions about CAM in particular and about treatment in general.

This study has several limitations. First, participants may have altered their behavior due to being audio-recorded, though previous research has suggested this may be minimal [41,42]. Second, crosssectional sampling limits observation to a single episode, excluding possible CAM talk and negotiations that may have occurred previously. Third, we did not collect data on providers' native language, and are unable to assess whether subtle cultural-linguistic issues might have affected interactions. Fourth, findings concerning the types and frequencies of CAM discussions may have limited generalizability because the sampled population was predominantly white, aged 50 and older, and most possessed some college education. While we did not investigate differences in the ways in which young–old and old–old participants initiated CAM talk, future empirical research can investigate variation in the patterns of negotiation between these groups that may be due to differences in lifecourse trajectories, neuroplasticity, and socio-cognitive functioning. Additionally, California has high rates of CAM use [43], and there was an integrative medicine clinic within the healthcare system in which the data were collected, which may have increased participants’ knowledge of and opportunity for CAM communication. It is unlikely that the physician stances and negotiation segments would differ substantively with alternate patient populations, but future research can examine this question. Finally, DA relies on participants' actual language use for analysis. Both patients and providers may have attitudes or beliefs about CAM to which DA may not be privy. Future research can combine methods to examine the outcomes of CAM conversations by following patients over multiple visits or by sampling other populations.

4.2. Conclusion

This study demonstrates that physician–patient discussions about CAM treatments can effectively help patients negotiate decisions about CAM use, regardless of a physician's stance toward or knowledge about CAM. Patient-initiated CAM discussions provide an opportunity for providers to explore patient treatment preferences and for researchers to examine how providers and patients negotiate treatment decision-making. Providers can adopt a range of stances toward patient CAM use, but how a provider responds to patient-initiated CAM discussion may be important for helping patients evaluate the risks and benefits of CAM in particular and treatment in general. Because ultimately patients will make their own decisions about whether to pursue a CAM treatment, CAM discussion is valuable because it can engage patients as active participants in their own medical care through exploring patient treatment preferences with a medical professional.

4.3. Practice implications

When patients initiate CAM discussions during primary care visits, they may be seeking professional expertise to help them make important treatment decisions. Healthcare providers can have useful CAM conversations without being experts in all forms of CAM [8]. While providers are becoming more aware of CAM research [44], many are still unaware of the variety of CAM treatment options available. Physicians can use patient-initiated CAM talk as an opportunity to share their current knowledge, their evaluative criteria, their stance, where to seek more information about CAM, and perhaps most importantly, to learn about patient treatment preferences and health beliefs. Regardless of stance, providers should explain their position on CAM use to provide patients with a better framework for evaluating CAM use. These steps can contribute to greater patient-centered care, thereby enhancing the therapeutic alliance.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the physicians and patients who generously agreed to be recorded and to Jeffry Good, PhD for providing research assistance on this study.

Funding support: Data used in this study were collected with a University of California, Los Angeles Mentored Clinical Scientist Development Award (5K12AG001004). Dr. Tarn was supported by this award and by the University of California, Los Angeles Older Americans Independence Center (NIH/NIA Grant P30-AG028748). Additional support was provided to Dr. Ho by the University of San Francisco Faculty Development Fund. None of the funding agencies had any involvement in the choosing of the project, data collection, analysis, writing, or submission of the article.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: None of the authors have any conflicts of interest with this research.

References

- 1.Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children United States, 2007. CDC National Health Statistics Report. 2008;(#12) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Advance data from vital and health statistics no 343. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2004. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, AARP. Consumer Survey Report. NCCAM, AARP; 2007. Complementary and alternative medicine: what people 50 and older are using and discussing with their physicians. [Google Scholar]

- 4.National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, AARP. Complementary and alternative medicine: what people aged 50 and older discuss with their health care providers. NCCAM, AARP; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Robinson A, McGrail MR. Disclosure of CAM use to medical practitioners: a review of qualitative and quantitative studies. Complement Ther Med. 2004;12:90–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sewitch MJ, Cepoiu M, Rigillo N, Sproule D. A literature review of health care professional attitudes toward complementary and alternative medicine. Complement Health Pract Rev. 2008;13:139–54. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts CS, Baker F, Hann D, Runfola J, Witt C, McDonald J, et al. Patient–physician communication regarding use of complementary therapies during cancer treatment. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2005;23:35–60. doi: 10.1300/j077v23n04_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schofield P, Diggens J, Charleson C, Marigliani R, Jefford M. Effectively discussing complementary and alternative medicine in a conventional oncology setting: communication recommendations for clinicians. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;79:143–51. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perlman AI, Eisenberg DM, Panush RS. Talking with patients about alternative and complementary medicine. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 1999;25:815–22. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(05)70102-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juraskova I, Hegedus L, Butow P, Smith A, Schofield P. Discussing complementary therapy use with early-stage breast cancer patients: exploring the communication gap. Integr Cancer Ther. 2010;9:168–76. doi: 10.1177/1534735410365712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schofield PE, Juraskova I, Butow PN. How oncologists discuss complementary therapy use with their patients: an audio-tape audit. Support Care Cancer. 2003;11:348–55. doi: 10.1007/s00520-002-0420-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sleath B, Rubin RH, Campbell W, Gwyther L, Clark T. Ethnicity and physician–older patient communication about alternative therapies. J Altern Complement Med. 2001;7:329–35. doi: 10.1089/107555301750463206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sleath B, Callahan L, DeVellis RF, Sloane PD. Patients' perceptions of primary care physicians' participatory decision-making style and communication about complementary and alternative medicine for arthritis. J Altern Complement Med. 2005;11:449–53. doi: 10.1089/acm.2005.11.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sleath B, Callahan LF, Devellis RF, Beard A. Arthritis patients' perceptions of rheumatologists' participatory decision-making style and communication about complementary and alternative medicine. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:416–21. doi: 10.1002/art.23307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bastiaens H, Royen P, Pavlic DR, Raposo V, Baker R. Older people's preferences for involvement in their own care: a qualitative study in primary health care in 11 European countries. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;68:33–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.03.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belcher VN, Fried TR, Agostini JV, Tinetti ME. Views of older adults on patient participation in medication-related decision making. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;21:298–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00329.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boon H, Westlake K, Deber R, Moineddin R. Problem-solving and decisionmaking preferences: no difference between complementary and alternative medicine users and non-users. Complement Ther Med. 2005;13:213–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2005.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Crabtree BF, Miller WL. Doing qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roberts C, Sarangi S. Theme-oriented discourse analysis of medical encounters. Med Educ. 2005;39:632–735. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2005.02171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Drew P, Heritage J, editors. Talk at work: interaction in institutional settings. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heritage J, Maynard D, editors. Communication in medical care: interaction between physicians and patients. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher S, Todd A, editors. The social organization of doctor–patient communication. Norwood, NJ: Ablex; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 23.West C. Routine complications: troubles in talk between doctors and patients. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gee PG. An introduction to discourse analysis: theory and method. 3rd. New York: Routeledge; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hodges BD, Kuper A, Reeves S. Qualitative research: discourse analysis. Brit Med J. 2008;337:7669. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shaw SE, Bailey J. Discourse analysis: what is it and why is it relevant to family practice? Fam Pract. 2009;26:413–9. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmp038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Goffman E. The neglected situation. Am Anthropol. 1964;66:133–6. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Goffman E. The interaction order. Am Sociol Rev. 1983;48:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Muhr T. Atlas ti 6 x. Berlin, Germany: Scientific Software; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jaffe AM, editor. Stance: sociolinguistic perspectives. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.ten Have P. Doing conversation analysis: a practical guide. London: Sage; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sacks H, Schegloff EA, Jefferson G. A simplest systematics for the organization of turn-taking for conversation. Language. 1974;50:696–735. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ben-Arye E, Frenkel M. Referring to complementary and alternative medicine: a possible tool for implementation. Compl Ther Med. 2008;16:325–30. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2008.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fraenkel L, McGraw S. What are the essential elements to enable patient participation in medical decision making? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:614–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0149-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Frenkel M, Ben-Arye E, Cohen L. Communication in cancer care: discussing complementary and alternative medicine. Integr Cancer Ther. 2010;9:177–85. doi: 10.1177/1534735410363706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corbin Winslow L, Shapiro H. Physicians want education about complementary and alternative medicine to enhance communication with their patients. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:1176–81. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.10.1176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Flannery MA, Love MM, Pearce KA, Luan JJ, Elder WG. Communication about complementary and alternative medicine: perspectives of primary care clinicians. Altern Ther Health Med. 2006;12:56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milden SP, Stokols D. Physicians' attitudes and practices regarding complementary and alternative medicine. Behav Med. 2004;30:73–82. doi: 10.3200/BMED.30.2.73-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Owen DJ, Fang ML. Information-seeking behavior in complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): an online survey of faculty at a health sciences campus. J Med Libr Assoc. 2003;91:311–21. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sawni A, Thomas R. Pediatricians' attitudes, experience and referral patterns regarding complementary/alternative medicine: a national survey. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2007;7:18. doi: 10.1186/1472-6882-7-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mackenzie CF, Xiao Y. Video techniques and data compared with observation in emergency trauma care. Qual Saf Health Care. 2003;12(Suppl II):ii51–7. doi: 10.1136/qhc.12.suppl_2.ii51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Penner LA, Orom H, Albrecht TL, Franks MM, Foster TS, Ruckdeschel JC. Camera-related behaviors during video recorded medical interactions. J Nonverbal Behav. 2007;31:99–117. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldstein MS, Brown ER, Ballard-Barbash R, Morgenstern H, Bastani R, Lee J, et al. The use of complementary and alternative medicine among California adults with and without cancer. Evidence Based Complement Altern Med. 2005;2:557–65. doi: 10.1093/ecam/neh138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wye L, Shaw A, Sharp D. Patient choice and evidence based decisions: the case of complementary therapies. Health Expect. 2009;12:321–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2009.00542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]