Abstract

Objective

Threats to external validity including pretest sensitization and the interaction of selection and an intervention are frequently overlooked by researchers despite their potential to significantly influence study outcomes. The purpose of this investigation was to conduct secondary data analyses to assess the presence of external validity threats in the setting of a randomized trial designed to promote mammography use in a high risk sample of women.

Design

During the trial, recruitment and intervention implementation took place in three cohorts (with different ethnic composition), utilizing two different designs (pretest-posttest control group design; posttest only control group design).

Results

Results reveal that the intervention produced different outcomes across cohorts, dependent upon the research design used and the characteristics of the sample.

Conclusion

These results illustrate the importance of weighing the pros and cons of potential research designs before making a selection and attending more closely to issues of external validity.

Keywords: external validity, research design, methodology, cancer screening, randomized controlled trial

INTRODUCTION

The pretest-posttest control group design (Shadish, Cook, & Campbell, 2002) is one of the most frequently used study designs in behavioral and psychosocial intervention research. Although use of this design controls for the majority of threats to internal validity, several important threats to external validity remain, including the interaction of testing and the intervention (i.e., pretest sensitization effects) and the interaction between participant selection and the intervention. Pretest sensitization occurs when the effect of an intervention, assessed at follow-up, is influenced by or dependent upon the presence of a pretest. Although pretest sensitization has been proposed as a significant problem in research (Kim, 2010; Lana, 2009; Shadish et al., 2002), it is unknown how frequently it occurs. The interaction between selection and the intervention occurs when the intervention effect is specific to the particular characteristics of the study sample, and would not be present if the intervention were to be implemented in a different sub-group or the population as a whole. These threats to external validity are frequently overlooked despite their potential to significantly influence study outcomes (Kim, 2010) and the effectiveness of policy or practice applications of the findings.

There has been a growing recognition of the need to enhance the external validity of intervention research across multiple disciplines, including increasing the representativeness of participant samples (Glasgow et al., 2006; Green & Glasgow, 2006). However, the best methods of doing so are not clear. Suggestions have included less reliance on randomized trials with strict research protocols and greater use of alternative designs with adoption of sophisticated statistical analyses to control for confounds (Bonell et al., 2011; Cousens et al., 2011; Glasgow, Lichtenstein, & Marcus, 2003; Green, 2001). Although implementing such suggestions may reduce the effect of selection on the outcome, the resultant loss of internal validity, may be undesirable. The effect of pretest sensitization can be reduced or controlled by selecting a post-test only or Solomon four-group design (e.g., intervention and control conditions, with and without a pretest) (Shadish et al., 2002; Solomon, 1949). In addition to providing a means of controlling pretest sensitization, the Solomon design allows one to assess the presence and magnitude of pretest sensitization and the interaction of sensitization and the intervention. Although scientifically advantageous, these designs are infrequently utilized. Researchers are often hesitant to use post-test only designs because they will not be able to confirm equality of randomized groups at baseline or, conversely, detect a failure of randomization. Solomon four-group designs are often considered unfeasible or prohibitively expensive in the context of an intervention trial, given the resultant increase in the sample size required compared to a two-group design.

In an attempt to assess the presence of external validity threats in controlled trials, we conducted retrospective analyses utilizing data from a randomized trial designed to increase mammography use in women at increased risk for breast cancer due to a family history of the disease (Bastani, Maxwell, & Bradford, 1996; Bastani, Maxwell, Bradford, Das, & Yan, 1999). Recruitment and intervention implementation took place in three cohorts, utilizing two different designs. The same intervention was delivered both in the context of a pretest-posttest control group design and a posttest only design providing an opportunity to observe the potential interaction between our intervention and the pretest. Further, the intervention was delivered across three cohorts of participants that varied on a number of demographic characteristics allowing for examination of the effect of the intervention across different participant samples.

METHODS

Overview of research designs

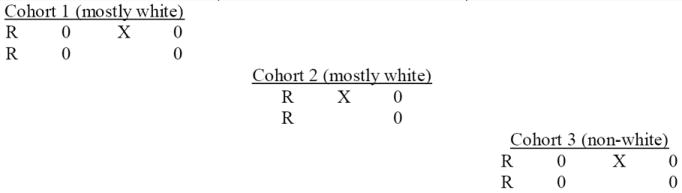

Three cohorts of first-degree relatives of breast cancer survivors were successively recruited into randomized experiments to assess the effectiveness of a mailed, personalized risk notification intervention in increasing screening mammography rates. Figure 1 provides an overview of the research designs utilized in each of the three cohorts. Cohort 1 involved a pretest-posttest control group design in a sample of predominantly white high-risk women. Cohort 2 was also predominantly white but the research design was a post-test only control group design. Cohorts 1 and 2, in combination, simulate a Solomon four-group design (Shadish et al., 2002; Solomon, 1949) with the factors being presence or absence of a pretest and presence or absence or the intervention. The two experiments do not qualify as a pure Solomon four-group design because they were not conducted simultaneously in time, but rather were separated by a period of one year. Cohort 3 was nearly exclusively non-white and utilized a pretest-posttest control group design.

Figure 1. Overview of Research Design by Cohort.

Notes: Baseline surveys (Cohorts 1 and 3) assessed knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and behavior; Follow-up surveys across all cohorts assessed content similar to the baseline surveys; R=random assignment; X=Intervention, 0 = Survey

Recruitment of participants and data collection

Under the Statewide Cancer Reporting Act of 1985, all newly diagnosed cancer cases in California are reported to the California Cancer Registry (CCR). For all three cohorts, contact information for women diagnosed with breast cancer was received from the CCR. For Cohorts 1 and 2 the CCR identified random samples of female breast cancer survivors diagnosed in 1988 (N=2500) and 1989 (N=2500). For Cohort 3 we obtained contact information for all Latina (N=2334), African-American (N=1541) and Asian (N=1400) survivors diagnosed in California in 1989 and 1990. Contact information for these women was obtained from the registry in late 1990, 1991 and 1992 respectively. Initially, the physician of record was sent a letter to inquire about any contraindication to contacting the individual (e.g., death or incapacitation). Breast cancer survivors whose physicians provided information that would preclude contact were excluded from the sample. Next, survivors were contacted by mail to inform them of the study and solicit information on their female first degree relatives, > 30 years of age. Eligible relatives identified in the above step were then contacted for recruitment into the study as described below.

Cohort 1 (white, with pretest) and Cohort 3 (non-white, with pretest)

Relatives in Cohorts 1 (white, with pretest) and 3 (non-white, with pretest) were sent an informational letter regarding the study and told to expect a telephone call in the next few weeks. A return form was included with the letter to allow participants to indicate good times for the telephone interview and their language preference (English or Spanish). Two to three weeks following the mailed notification, eligible relatives were contacted by telephone to recruit them into the study and to obtain baseline information on eligibility, risk factors, screening behavior, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and other psycho-social variables. Eligibility criteria included being the mother, sister or daughter of the index case, being 30 years of age or older, residing in the United States or Canada, and having no personal history of breast cancer. Following the baseline survey, participants were randomized into an intervention or control group. Intervention participants received a mailed intervention consisting of a personalized, tailored risk assessment as well as a brochure and bookmark targeting high risk women that included messages regarding the importance of obtaining regular screening mammography. Approximately one year following the baseline survey participants were re-contacted and asked to complete a post-test survey to assess screening behavior, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs and other psycho-social variables. Participants in Cohort 1 were randomly assigned to complete the follow-up survey by mail or by telephone. All participants in Cohort 3 were invited to complete the follow-up survey by telephone.

Cohort 2 (white, no pretest)

Relatives in Cohort 2 (white, no pretest) were sent an informational letter regarding the study accompanied by a brief risk assessment form to be returned by mail. The risk assessment form only included items needed to assess breast cancer risk factors that were used for tailoring the intervention. Unlike Cohorts 1 and 3, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and screening behavior were not assessed at baseline. The protocol used to deliver the intervention (timing, content, etc) to this cohort was identical to that used in Cohorts 1 and 3. Twelve-month follow-up data were obtained via a mailed survey, which was identical to that used in Cohorts 1 and 3. Additional details related to participant recruitment and the intervention are reported elsewhere (Bastani et al., 1996; Bastani et al., 1999). No difference in mammography rates at follow-up were observed between participants providing post-test data by mail versus the telephone.(Bastani et al., 1999). The research was approved by the institutional review board of the University of California, Los Angeles.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics by Cohort

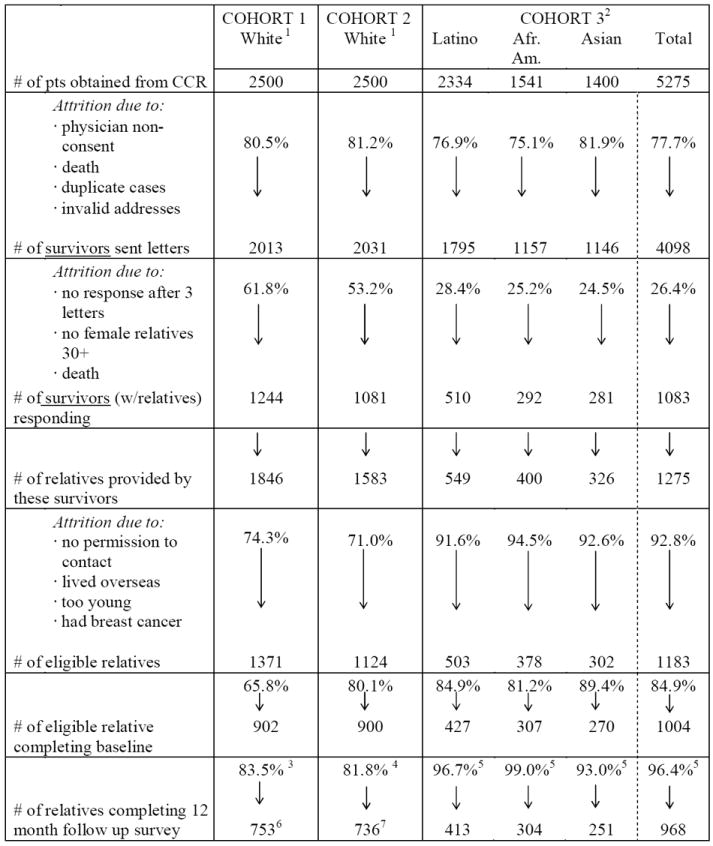

Table 1 displays response rates at the various stages of participant accrual as well as the process used to collect follow-up data across the three cohorts. Cohorts 1 and 2 (mostly white) are very similar with respect to response rates at each step. Cohort 3 (non-white), on the other hand, is dramatically different. Over 50% of survivors in Cohort 1 and 2 responded to our letter requesting contact information for their first degree relatives. In contrast, the response rate among non-white survivors (Cohort 3) was only around 25%. However, response rates among eligible relatives referred to the study by survivors were uniformly higher among non-white (85%, for Cohort 3) compared to white participants (72%, Cohorts 1 and 2 combined). Retention rates at the 12-month follow-up were high and quite similar across all three cohorts.

Table 1.

Ethnic Differences in Accrual of First Degree Female Relatives of Breast Cancer Survivors Identified through the California Cancer Registry (CCR)

|

Notes:

Cohort 1 & 2 were random samples of cases diagnosed in 1988 and 1989 in California. The vast majority of survivors were white.

Cohort 3 consisted of all non-white breast cancer survivors diagnosed in 1989 and 1990 in California.

Half of the follow-up interviews were conducted by phone, half by mail

All of the follow-up interviews were conducted by mail.

All of the follow-up interviews were conducted by phone.

678 out of 753 relatives self-identified as being white (90%).

678 out of 736 relatives self-identified as being white (92%).

Table 2 provides a comparison of the demographic characteristics of the three cohorts. Cohorts 1 and 2 (white) were very similar to one another on all demographic variables. Both cohorts were over 90% white, with relatively high levels of income and education. Also, control group posttest rates were similar in Cohorts 1 and 2 (see Table 3), further supporting a priori comparability of these two groups. In contrast, Cohort 3 was mostly non-white (i.e., 42%Latino, 31% African American, 27% Asian). Income and education levels were somewhat lower in Cohort 3 compared to the other two cohorts, as was the proportion of participants who were married or living as married. Insurance coverage was high across all three cohorts.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Respondents

| Cohort 1 (N=753) % |

Cohort 2 (N=736) % |

Cohort 3 (N=993) % |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 30-39 | 27 | 27 | 33 |

| 40-49 | 26 | 28 | 27 | |

| 50-64 | 25 | 22 | 26 | |

| > 65 | 22 | 23 | 15 | |

|

| ||||

| Ethnicity | White | 90 | 93 | 1 |

| Latino | 3 | 1 | 42 | |

| African-American | 2 | 3 | 31 | |

| Asian | - | - | 24 | |

| Other 1 | 4 | 3 | 2 | |

|

| ||||

| Education | Less than high school | 4 | 7 | 13 |

| High school diploma | 27 | 30 | 27 | |

| 1 - 3 years college | 35 | 31 | 35 | |

| College degree or higher | 34 | 32 | 25 | |

|

| ||||

| Marital Status | Married or living as married | 71 | 70 | 61 |

|

| ||||

| Income | < 20,000 | 14 | 16 | 23 |

| 20,000 - 29,000 | 19 | 15 | 15 | |

| 30,000 - 39,999 | 17 | 15 | 19 | |

| 40,000 - 49,999 | 15 | 14 | 12 | |

| ≥ 50,000 | 36 | 41 | 30 | |

|

| ||||

| Insurance | Yes | 93 | 92 | 88 |

Note:

Includes Asians in Cohorts 1 and 2

Table 3.

Screening Rates by Cohort

| Baseline % | Follow-Up % | Change % | P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cohort 1 (mostly white, pretest) | I (N=382) | 55.0 | 65.2 | 10.2 | ||

| C (N=371) | 54.9 | 57.7 | 2.5 | .05 1 | ||

| Cohort 2 (mostly white, no pretest) | I (N=370) | ----- | 59.0 | |||

| C (N=366) | ----- | 58.0 | .84 2 | |||

| Cohort 3 (non-white, pretest) | I (N=493) | 45.0 | 50.1 | 5.1 | ||

| C (N=502) | 47.2 | 47.0 | -0.2 | .001 1 |

Notes:

significance of I/C. difference in change scores, chi-square test

significance of I/C. difference in follow-up scores, chi-square test

Analysis of the Intervention Effect by Cohort

The main outcome of interest in all three experiments/cohorts was whether or not participants obtained a screening mammogram in the period between study enrollment and the 12 month follow-up survey. Table 3 displays screening rates at baseline and follow-up by intervention versus control condition for all three cohorts. For Cohorts 1 and 3, no differences were observed in baseline mammography rates between intervention and control groups. To assess intervention effectiveness, change scores calculated separately for the intervention and control groups were directly compared, within each cohort, using the Mann-Whitney U test. First, two indicator variables were created for each woman to note whether she had a mammogram in the 12 months preceding baseline and in the 12 months between baseline and follow-up. For each variable, a “0” indicated no mammogram and a “1” indicated receipt of a mammogram. For each woman, a change score was created by subtracting the value of the indicator variable for baseline from the follow-up value. Significantly greater increases in mammography rates were observed in the intervention compared to control groups for both Cohorts 1 and 3, indicating a significant intervention effect. Logistic regression analysis, controlling for baseline mammography rates and covariates, yielded identical results.

In Cohort 2, direct comparison of post-test rates between intervention and control groups yielded non-significant results in chi-square analyses. To complete the picture, post-test comparisons were also conducted in Cohorts 1. A significant intervention versus control group difference at post-test was observed for Cohort 1 (p < .05).

The pattern of results obtained revealed significant intervention effects in Cohorts 1 and 3, but not in Cohort 2, suggesting that the intervention was only effective in the presence of a pretest. This illustrates the classic external validity threat of “the interaction of testing and X” described by Campbell and Stanley in 1966, in which the pretest may prompt participants to be more receptive to the intervention. Also, a comparison of the control group rates for Cohorts 1 and 3 seems to indicate that the pretest alone resulted in a slight increase in screening among the predominantly white women in Cohort 1 but not in the minority women in Cohort 3. Furthermore, the intervention effect appeared somewhat greater among white compared to ethnic minority women, providing support for an “interaction of selection and the intervention” in which the demographic characteristics of the participants may have influenced the study outcome. Additional evidence that participant ethnicity was an important factor in influencing the effectiveness of the intervention is provided in Table 4, which displays outcomes separately for the three ethnic minority groups within Cohort 3. No intervention effect appears to be present within African Americans or Latinos (< 3% point difference in mammography rates between intervention and control groups). However, the effect of the intervention among Asians is substantially larger compared to other ethnic groups (9% point advantage for intervention versus control condition), although the intervention effect is not statistically significant due to the small size of this group (n = 251). Therefore, in the presence of a pretest, it appears that there is an unambiguous intervention effect in the white cohort. In the non-white cohort, the effect is smaller and less clearly visible. Namely, the results depended upon the design utilized and the particular ethnic group examined.

Table 4.

Screening Rates by Ethnicity for Cohort 3

| Baseline % | Follow-Up % | Change % | P-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African American | I (N=151) | 44.4 | 50.0 | 5.6 | |

| C (N=156) | 46.7 | 50.0 | 3.3 | 0.50 | |

| Latino | I (N=205) | 46.5 | 46.1 | -0.4 | |

| C (N=219) | 48.5 | 50.0 | 1.5 | 0.73 | |

| Asian | I (N=141) | 45.7 | 52.8 | 7.1 | |

| C (N=128) | 46.4 | 44.6 | -1.8 | 0.101 |

Notes:

significance of I/C. difference in change scores, chi-square test

DISCUSSION

The present study demonstrates the effects of two often overlooked threats to external validity in randomized trials: pretest sensitization and the participant selection. Examination of the intervention effect in any of the three cohorts in isolation would have lead to inaccurate conclusions. The randomized pretest-posttest control group design employed in Cohorts 1 and 3 would lead us to conclude that our intervention was effective among Whites as well as among minority participants. We would likely feel justified in encouraging wide adoption of this “evidence based” intervention in community practice. However, examination of the results of our intervention in all three cohorts collectively provides a much different picture. We discover in Cohort 2 that when the intervention was delivered to a sample of White women at high risk for breast cancer (almost identical to the Cohort 1 sample) without administering a pretest, screening rates did not increase, suggesting that our intervention was only effective when implemented following a pretest. This is a classic illustration of the interaction of the pretest and the intervention. Given that most intervention trials utilize a two-group pretest-posttest randomized design, the frequency at which pretest sensitization occurs is largely unknown. It is conceivable that researchers often erroneously assume that an intervention is effective, when in fact the outcome improvements observed would occur only in the context of a pretest. This may, in part, explain the failure of many interventions, found to be effective in randomized controlled trials, to be successful when implemented in “real life” settings without a pretest.

Our results also provide support for the presence of an interaction of selection and the intervention such that the intervention was not uniformly effective across all ethnic groups. The effect of our intervention was more pronounced among white versus ethnic minority women suggesting that the intervention effect was influenced by characteristics of the sample. Upon taking a closer look at the effect of the intervention among ethnic minority women, we found that the effect was present only for Asian women. These results illustrate the importance of stratified and exploratory analyses to assess not only whether an intervention is effective but for whom it has an effect.

Stratified sampling (e.g., oversampling ethnic minority populations) is only one method to enhancing the ability to examine “for whom did an intervention work.” Often stratification is not feasible, and therefore one may want to consider statistical methods to explore these issues (e.g., subgroup, moderator, or responder analyses). One advantage to utilizing stratification is that one decides a priori, based on theoretical or data-based assumptions what factors are anticipated to be related to the effect of the intervention and an attempt is make to ensure sufficient sample sizes within each subgroup for analyses. Statistical methods of examining “for whom” an intervention is effective may be an acceptable alternative. However, statistical methods have their limits, particularly if the resultant study sample is very homogeneous or heterogeneous, small in size, or when analyses are based primarily on post-hoc observations (Pocock, Assmann, Enos, & Kasten, 2002; Senn & Julious, 2009; Wang, Lagakos, Ware, Hunter, & Drazen, 2007). Statistical methods of control also rely heavily on the quality of measures implemented and the assumption that the all of the important concepts have been assessed. Meta-analysis is another method of reducing the biases that may occur when interpreting results of individual studies (Egger & Smith, 1997). However, the strengths of meta-analysis and data-synthesis techniques are diminished with greater heterogeneity of the existing literature (Higgins & Thompson, 2002; Howard, Maxwell, & Fleming, 2000). In addition, meta-analysis represents only a long-term solution, since these analyses can only be utilized after multiple studies using similar methods have been published within a particular area of research.

Threats to external validity, including pretest sensitization and the interaction of testing and the intervention, have historically not been given due attention in the field of intervention research (Kim, 2010; Moore & Moore, 2011). This realization has resulted in a relatively recent move towards effectiveness studies and away from strictly controlled efficacy trials and has fed the rapidly developing fields of dissemination, implementation, and translational research (Glasgow et al., 2006; Glasgow et al., 2003; Green & Glasgow, 2006). Although increasingly acknowledged as important, only a handful of recent studies in the fields of health psychology, behavioral medicine, and public health have directly examined the impact of threats to external validity on research outcomes (Donovan, Wood, Frayjo, Black, & Surette, 2012; Kim, 2010; Rubel et al., 2011; Spence, Burgess, Rodgers, & Murray, 2009). Thus, this study provides a valuable contribution to the literature.

The present study was not conducted as a true Solomon four-group design therefore our ability to determine the extent of the effect of pretest sensitization is diminished. The contribution of differences in the treatment of the three cohorts and the effect of time on the pattern of results obtained cannot be directly assessed. Despite these limitations, our study serves as a powerful illustration of the potential effect of these two threats to external validity.

Failure to acknowledge the influence of pretest sensitization or selection may lead researchers to make misguided and inaccurate conclusions about an intervention’s effectiveness. In the present study, these factors led to false positive results. Given the goal of population-wide dissemination of evidence based interventions, it becomes important to closely examine our criteria for what is “evidence based”. Researchers should increase their attention to issues of external validity when making decisions regarding intervention research design.

References

- Bastani R, Maxwell A, Bradford C. A tumor registry as a tool for recruiting a multi-ethnic sample of women at high risk for breast cancer. Journal of Registry Management. 1996;23:74–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bastani R, Maxwell AE, Bradford C, Das IP, Yan KX. Tailored risk notification for women with a family history of breast cancer. Prev Med. 1999;29(5):355–364. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1999.0556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonell CP, Hargreaves J, Cousens S, Ross D, Hayes R, Petticrew M, et al. Alternatives to randomisation in the evaluation of public health interventions: design challenges and solutions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(7):582–587. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.082602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cousens S, Hargreaves J, Bonell C, Armstrong B, Thomas J, Kirkwood BR, et al. Alternatives to randomisation in the evaluation of public-health interventions: statistical analysis and causal inference. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(7):576–581. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.082610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donovan E, Wood M, Frayjo K, Black RA, Surette DA. A randomized, controlled trial to test the efficacy of an online, parent-based intervention for reducing the risks associated with college-student alcohol use. Addict Behav. 2012;37(1):25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egger M, Smith GD. Meta-Analysis. Potentials and promise. BMJ. 1997;315(7119):1371–1374. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7119.1371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Green LW, Klesges LM, Abrams DB, Fisher EB, Goldstein MG, et al. External validity: we need to do more. Ann Behav Med. 2006;31(2):105–108. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3102_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasgow RE, Lichtenstein E, Marcus AC. Why don’t we see more translation of health promotion research to practice? Rethinking the efficacy-to-effectiveness transition. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1261–1267. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW. From research to “best practices” in other settings and populations. Am J Health Behav. 2001;25(3):165–178. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.25.3.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green LW, Glasgow RE. Evaluating the relevance, generalization, and applicability of research: issues in external validation and translation methodology. Eval Health Prof. 2006;29(1):126–153. doi: 10.1177/0163278705284445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard GS, Maxwell SE, Fleming KJ. The proof of the pudding: an illustration of the relative strengths of null hypothesis, meta-analysis, and Bayesian analysis. Psychol Methods. 2000;5(3):315–332. doi: 10.1037/1082-989x.5.3.315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim ES, W VL. Evaluation pretest effects in pre-post studies. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2010;70(5):744–759. [Google Scholar]

- Lana RE. Pretest Sensitization. In: Rosenthal R, Rosonow RL, editors. Artifacts in behavioral research: Robert Rosenthal and Ralph L Rosnow’s classic books. New York, New York: Oxford University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Moore L, Moore GF. Public health evaluation: which designs work, for whom and under what circumstances? J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65(7):596–597. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.093211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock SJ, Assmann SE, Enos LE, Kasten LE. Subgroup analysis, covariate adjustment and baseline comparisons in clinical trial reporting: current practice and problems. Stat Med. 2002;21(19):2917–2930. doi: 10.1002/sim.1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubel SK, Miller JW, Stephens RL, Xu Y, Scholl LE, Holden EW, et al. Testing the effects of a decision aid for prostate cancer screening. J Health Commun. 2011;15(3):307–321. doi: 10.1080/10810731003686614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senn S, Julious S. Measurement in clinical trials: a neglected issue for statisticians? Stat Med. 2009;28(26):3189–3209. doi: 10.1002/sim.3603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for generalized causal inference. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon RL. An extension of control group design. Psychol Bull. 1949;46(2):137–150. doi: 10.1037/h0062958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence JC, Burgess J, Rodgers W, Murray T. Effect of pretesting on intentions and behaviour: a pedometer and walking intervention. Psychol Health. 2009;24(7):777–789. doi: 10.1080/08870440801989938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Lagakos SW, Ware JH, Hunter DJ, Drazen JM. Statistics in medicine--reporting of subgroup analyses in clinical trials. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(21):2189–2194. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr077003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]