Abstract

CD8+ T cells are key factors mediating hepatitis B virus (HBV) clearance. However, these cells are killed through HBV-induced apoptosis during the antigen-presenting period in HBV-induced chronic liver disease (CLD) patients. Interferon-inducible protein 6 (IFI6) delays type I interferon-induced apoptosis in cells. We hypothesized that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the IFI6 could affect the chronicity of CLD. The present study included a discovery stage, in which 195 CLD patients, including chronic hepatitis B (HEP) and cirrhosis patients and 107 spontaneous recovery (SR) controls, were analyzed. The genotype distributions of rs2808426 (C > T) and rs10902662 (C > T) were significantly different between the SR and HEP groups (odds ratio [OR], 6.60; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.64 to 26.52, p = 0.008 for both SNPs) and between the SR and CLD groups (OR, 4.38; 95% CI, 1.25 to 15.26; p = 0.021 and OR, 4.12; 95% CI, 1.18 to 14.44; p = 0.027, respectively). The distribution of diplotypes that contained these SNPs was significantly different between the SR and HEP groups (OR, 6.58; 95% CI, 1.63 to 25.59; p = 0.008 and OR, 0.15; 95% CI, 0.04 to 0.61; p = 0.008, respectively) and between the SR and CLD groups (OR, 4.38; 95% CI, 1.25 to 15.26; p = 0.021 and OR, 4.12; 95% CI, 1.18 to 14.44; p = 0.027, respectively). We were unable to replicate the association shown by secondary enrolled samples. A large-scale validation study should be performed to confirm the association between IFI6 and HBV clearance.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus, IFI6, single nucleotide polymorphism

Introduction

Between 350 and 400 million people worldwide are chronically infected with the hepatitis B virus (HBV) [1, 2]. In most HBV-infected patients, spontaneous recovery (SR) by the host immune system is common. However, 5% to 10% of patients fail to recover and remain as HBV-induced chronic liver disease (CLD) patients [3]. CLD, including HBV-induced chronic hepatitis B (HEP) and HBV-induced cirrhosis (CIR), is a major cause of hepatocellular carcinoma, which can lead to liver-related death [4]. The high mortality of CLD is a major problem in HBV-endemic countries [5]. In Korea, which is an HBV endemic area, more than 70% of CLD patients are infected by HBV [6, 7].

CD8+ T cells are key factors involved in the chronicity of CLD. The major roles of CD8+ T cells in HBV clearance are the production of interferon (IFN)-γ, which inhibits HBV gene expression and the assembly of HBV RNA-containing capsids, and the induction of apoptosis of virus-infected hepatocytes, which requires physical contact with CD8+ T cells [8-11]. However, the CD8+ T cells of CLD patients undergo activation-induced apoptosis instead of proliferation in the presence of antigen-presenting cells [12, 13]. Apoptosis of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in CLD patients and lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus (LCMV)-infected type I IFN receptor-null mice is mediated by B-cell lymphoma (Bcl)-2 [12, 14-16], indicating that type I IFN is critical to the survival of antigen-specific CD8+ T cells during the transition from acute to chronic HBV infection. Kolumam et al. [16] reported that type I IFN acts directly on CD8+ T cells to allow clonal expansion and memory formation in response to LCMV infection. Type I IFN receptor-null CD8+ T cells neither produce antiviral molecules, including IFN-γ, granzyme B, and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α nor show reduced survival after antigen-induced stimulation [16].

Type I IFN on CD8+ T cells is critical for survival, proliferation, and antiviral functions [16]. IFNs are a well-known family of cytokines with antiviral effects [17, 18]. IFNs modulate cellular proliferation and stimulate immune responses through several IFN-stimulated genes (ISGs) [19]. IFN-α-inducible protein 6 (IFI6) is a type I ISG [20-22] that maps to chromosome 1p35 [23] and is regulated by the Janus tyrosine kinase signal transducer and activator of transcription signaling pathway [24]. IFI6 is a mitochondria-targeted protein; it inhibits the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria and delays the apoptotic process initiated and transduced by the TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand/caspase 8 pathway [25]. The role of IFI6 is strongly associated with the immune system, but its antiviral effects are not well known [26].

In the present study, we hypothesized that IFI6 may be a survival-promoting factor for CD8+ T cells and therefore a determinant of the chronicity of HEP. The frequencies of IFI6 polymorphisms in CLD patients and SR controls were compared using logistic regression.

Methods

Subjects for the case-control study

A discovery stage included 305 blood samples obtained from the outpatient clinic of the Gastroenterology Department and from the Center for Health Promotion of Ajou University Hospital (Suwon, Korea) without gender or age restrictions between March 2002 and February 2006. Samples were derived from genetically unrelated Korean patients. The experimental protocol was approved by the institutional review board. Samples were divided into SR control (n = 107), HEP (n = 111), and CIR (n = 87) groups, according to serological markers and biopsy results. Three samples in the HEP group were not genotype-replicated and were excluded from the analysis. Finally, 107 SR control, 108 HEP, and 87 CIR patients were analyzed.

In the replication stage, 736 blood samples were collected from Ajou University Hospital and Keiymung University (Daegu, Korea) between February 2006 and September 2012. Samples were derived from genetically unrelated Korean patients. The experimental protocol was approved by the institutional review board. Samples were divided into two 205 SR controls, 437 HEP patients, and 94 CIR patients according to serological markers and biopsy results.

All samples were infected with HBV and classified into one of the three groups, according to their HBV infection status, clinical data, and serological profile, by a pathologist. Every 6 months for >12 months, the 218 patients were subjected to serological tests for serum levels of hepatitis B core antibody (Anti-HBc II Reagent Kit; Abbott Laboratories, South Pasadena, CA, USA), hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) (Anti-HBs; Abbott Laboratories), and hepatitis B surface antibody (HBsAb) (HBsAg; Abbott Laboratories). Liver function was evaluated by measuring aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), albumin, and bilirubin levels using commercially available assays. All samples showed elevated ALT at least once during the follow-up period and were positive for HBV DNA, irrespective of hepatitis B e antigen (HBeAg) positivity. Patients in the SR group were HBsAg-negative, HBeAg-negative, anti-HBs-positive, and anti-HBc-positive and had recovered from HBV infection. Patients in the CLD group, including those in the HEP and CIR groups, were HBsAg-positive for more than 6 months with elevated ALT and AST (≥2 times the normal upper limit). Samples that were positive for anti-hepatitis C virus (Genedia HCV ELISA 3.0; GreenCross, Yoingin, Korea) or anti-immunodeficiency virus antibodies (HIV Ag/Ab combo; Abbott Laboratories) were excluded.

Sample preparation

All blood samples were stored at -80℃ for the handling of human genomic DNA. Genomic DNA was purified using G-DEX blood genomic DNA (gDNA) purification kits (Intron Biotechnology Inc., Seongnam, Korea).

The gDNA for the discovery analysis was quantified using the picogreen dsDNA quantification reagent following a standard protocol (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA). The plates were read using a VICTOR3 1420 Multilabel counter (excitation 480 nm, emission 520 nm; PerkinElmer Inc., Waltham, MA, USA), and a standard curve for gDNA concentration was generated using known concentrations of lambda DNA.

The quality of the gDNA analyzed in the replication stage was determined using a NanoDrop ND-1000 UV-Vis Spectrophotometer (Thermo, Eugene, OR, USA). Genomic DNA was diluted to a concentration of 10 ng/µL in 96-well PCR plates.

Single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) selection and genotyping

In the discovery stage, six SNPs were selected from a public SNP database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/snp/) for the genotyping assay: 1) polymorphic in Chinese and Japanese; 2) tag SNPs in Asian; 3) might have functionality in protein or expression level. The selected SNPs were 1) one SNP in the 5' flanking region (rs2808426); 2) three intronic SNPs (rs10902662, rs1316896, and rs4908351); 3) one SNP in the untranslated region (rs1141747); and 4) one SNP in the 3' flanking region (rs2808430). The genotyping was performed using the GoldenGate kit according to a standard protocol (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Oligos were amplified by allele-specific primer extension. After hybridization to a sentrix array matrix, signal intensities were read by BeadArray Reader (Illumina Inc.). Genotyping analysis was performed using GenomeStudio software (version 1.5.16; Illumina Inc.).

In the replication stage, rs2808426, which was identified in the discovery stage, was genotyped using Taqman technology. The probes were labeled with FAM or VIC dye at the 5' end and a minor groove binder and nonfluorescent quencher at the 3' end. All reactions were performed following the supplier's protocol. SNP genotyping reactions were performed on the ABI PRISM 7900HT real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). After the PCR amplification, allelic discrimination was performed on the ABI PRISM 7900HT. Allele calls were made with SDS v2.4 software (Applied Biosystems).

Statistical analysis

The genetic models for the association test were divided according to additive (AA vs. Aa vs. aa), dominant (AA vs. Aa plus aa), and recessive (AA plus Aa vs. aa) models. The χ2 test was used to assess the Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE) in the SR, HEP, CIR, and CLD groups. The difference between groups was determined by the odds ratio (OR). ORs were presented with 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) and adjusted for age and sex. Each individual haplotype was inferred from the EM algorithm using the SAS haplotype procedure (version 9.1; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Linkage disequilibrium (LD) blocks were checked by the Gabriel method using Haploview software (version 4.2; Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA). All statistical tests were performed using SAS software, and the significance level was set at p < 0.05. The probability values obtained were corrected for multiple testing by using Bonferroni's correction and permutation test. Bonferroni's p-value for reaching significance was 0.025 (0.05/2). The Plink program was used to confirm the results and permutation test (n = 100,000; http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/).

Results

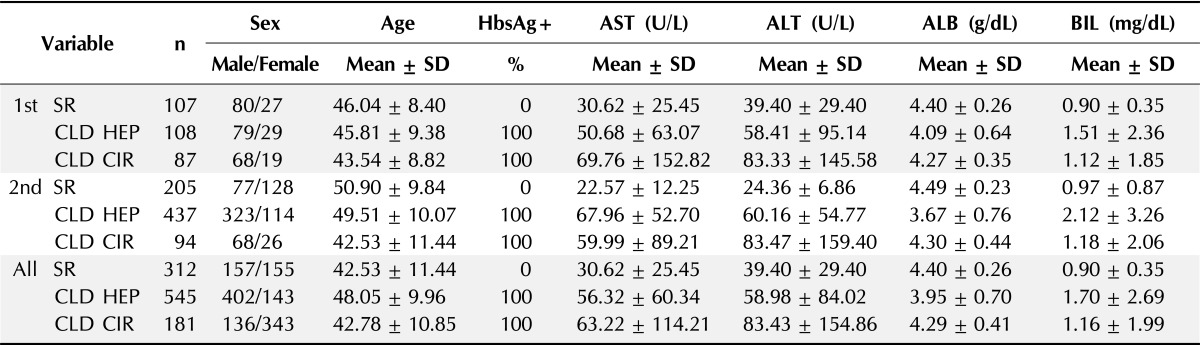

The fate of the patients infected with HBV was determined by several factors, including host immune reactions. Type I IFNs play a key role in the defense against HBV infection and therefore in the prevention of chronic hepatitis. IFI6 is induced by type I IFN. To test the effect of IFI6 polymorphisms on the chronicity of HEP, samples were collected from SR controls (HBsAg-), who recovered from HBV infection without any treatment, and CLD patients, including HEP and CIR groups (HBsAg+), who were at risk of HBV infection. To analyze first whether variations in the IFI6 gene were associated with the susceptibility to HEP in the Korean population, 107 controls in the SR group, 108 patients in the HEP group, and 95 patients in the CIR group were analyzed for six SNPs of IFI6 (n = 302). The characteristics of the study subjects are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of study subjects

Age, aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, albumin, and bilirubin are summarized and expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD).

HbsAg+, hepatitis B surface antigen positive; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALB, albumin; BIL, bilirubin; SR, spontaneous recovery; CLD, chronic liver disease; HEP, chronic hepatitis B; CIR, liver cirrhosis.

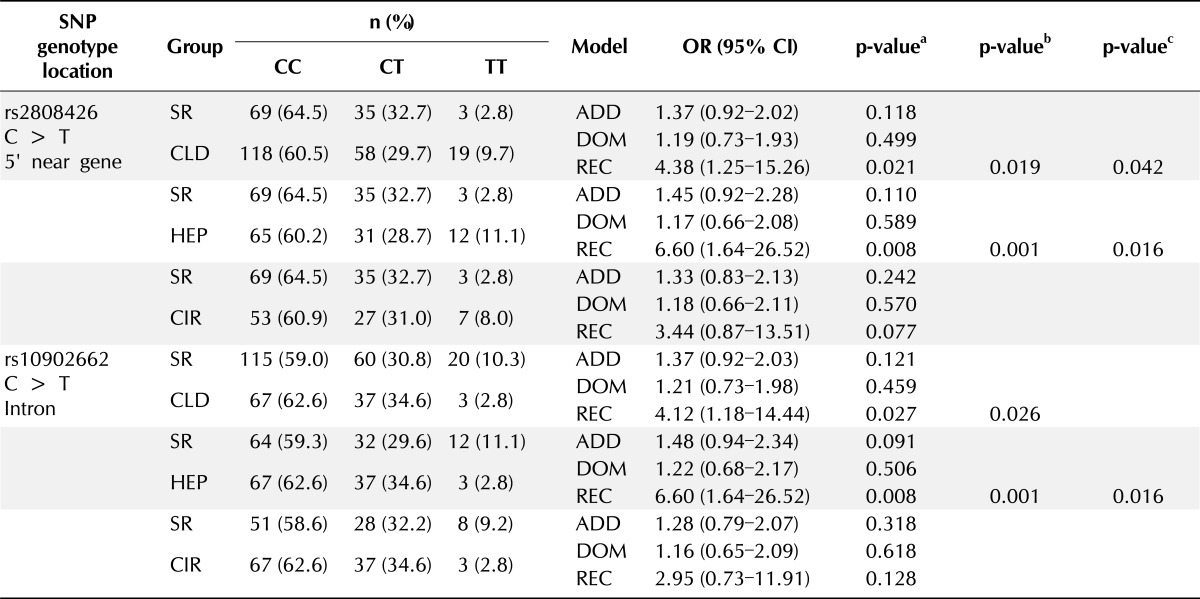

In the first phase or discovery stage, four out of six SNPs (rs1316896, rs4908351, rs1141747, and rs2808430) were monomorphic. Genetic variants of rs2808426 and rs10902662 did not show evidence of departure from minor allele frequency and HWE in either of the groups (p > 0.05). Two genotypes had minor allele frequencies greater than 1% (Table 2). The results of the genotype analysis showed that the CC genotype was the most common in the rs2808426 and rs10902662 polymorphisms in all groups. To analyze the genetic association between IFI6 polymorphisms and clearance from CLD, HEP, and CIR, multiple logistic regression analysis with adjustment for gender and age was performed.

Table 2.

Genotype frequencies and associations between SR and CLD in IFI6 SNPs

SR, spontaneous recovery; CLD, chronic liver disease; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphisms; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ADD, additive; DOM, dominant; REC, recessive; HEP, chronic hepatitis B; CIR, liver cirrhosis.

aThe p-values were obtained from logistic regression with additive, dominant, and recessive models; bThe p-values were calculated by Permutation test; cThe p-values were calculated by Bonferroni's correction.

In the comparison between SR and CLD patients, rs2808426 was associated with CLD in a recessive model (OR, 4.38; 95% CI, 1.25 to 15.26; p = 0.021). In addition, rs10902662 showed significant differences between the SR and CLD groups in a recessive model (OR, 4.12; 95% CI, 1.18 to 14.44; p = 0.027). After the permutation test, the rs2808426 and rs10902662 SNPs still had significant correlations (p < 0.026). After Bonferroni's correction, only rs2808426 had significant correlations (p = 0.042) (Table 2).

Comparison between the SR and HEP groups showed that the IFI6 SNPs rs2808426 and rs10902662 in the promoter region were associated with a higher risk that correlated with the homozygous variant TT genotype in a recessive model (OR, 6.60; 95% CI, 1.64 to 26.52; p = 0.008). After the permutation test, the rs2808426 and rs10902662 SNPs still had significant correlations (p = 0.001 in both genotype analyses), which were maintained after Bonferroni's correction (p = 0.016 in both genotype analyses) (Table 2).

The results of the multiple logistic regression analysis comparing the SR and CIR groups showed that the rs2808426 and rs10902662 SNPs were not associated in all genetic models (Table 2).

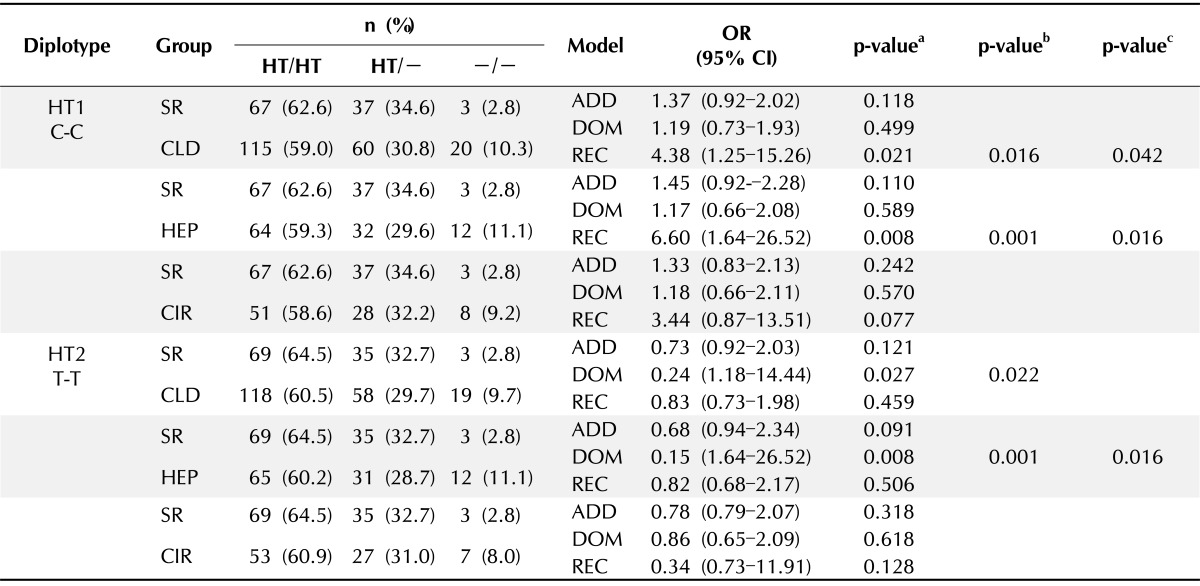

The possible genetic linkage between the rs2808426 and rs10902662 polymorphisms in the protection against chronic HBV infection was examined. LD blocks were constructed by the Gabriel method using Haploview software. The complete LD block consisted of rs2808426 and rs10902662 and showed a pairwise |D'| = 1 and r2 = 0.942, which reflect strong LD. The variants across IFI6 consisted of a single LD block structure composed of two haplotypes (HTs). The diplotype consisted of HT1 C-C (C allele of rs2808426; C allele of rs10902662) and HT2 T-T (T allele of rs2808426; T allele of rs10902662). The results of the HT estimation showed that the CC and TT haplotypes accounted for over 99% distribution in all groups. According to three genetic models, estimated HTs were used for diplotype analysis by logistic regression, adjusting for age and sex.

In the recessive model, HT1 frequency was significantly different between the SR and the CLD (OR, 0.021; 95% CI, 1.25 to 15.26; p = 0.021) and HEP (OR, 6.67; 95% CI, 1.64 to 26.52; p = 0.008) groups. Analysis of the HT2 diplotype showed a significant difference between the SR and HEP (OR, 0.15; 95% CI, 1.64 to 26.52; p = 0.008) and CLD (OR, 0.24; 95% CI, 1.18 to 14.44; p = 0.027) groups in the dominant model (Table 3). All diplotype p-values remained significant after the permutation test (p < 0.022), and with the exception of HT2 in the SR and CLD groups, almost all of the diplotype p-values remained significant after Bonferroni's correction (p < 0.042).

Table 3.

Diplotype frequencies and associations between SR and CLD in IFI6 SNPs

SR, spontaneous recovery; CLD, chronic liver disease; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; HT, haplotype; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; ADD, additive; DOM, dominant; REC, recessive; HEP, chronic hepatitis B; CIR, liver cirrhosis.

aThe p-values were obtained from logistic regression with additive, dominant, and recessive models; bThe p-values were calculated by Permutation test; cThe p-values were calculated by Bonferroni's correction.

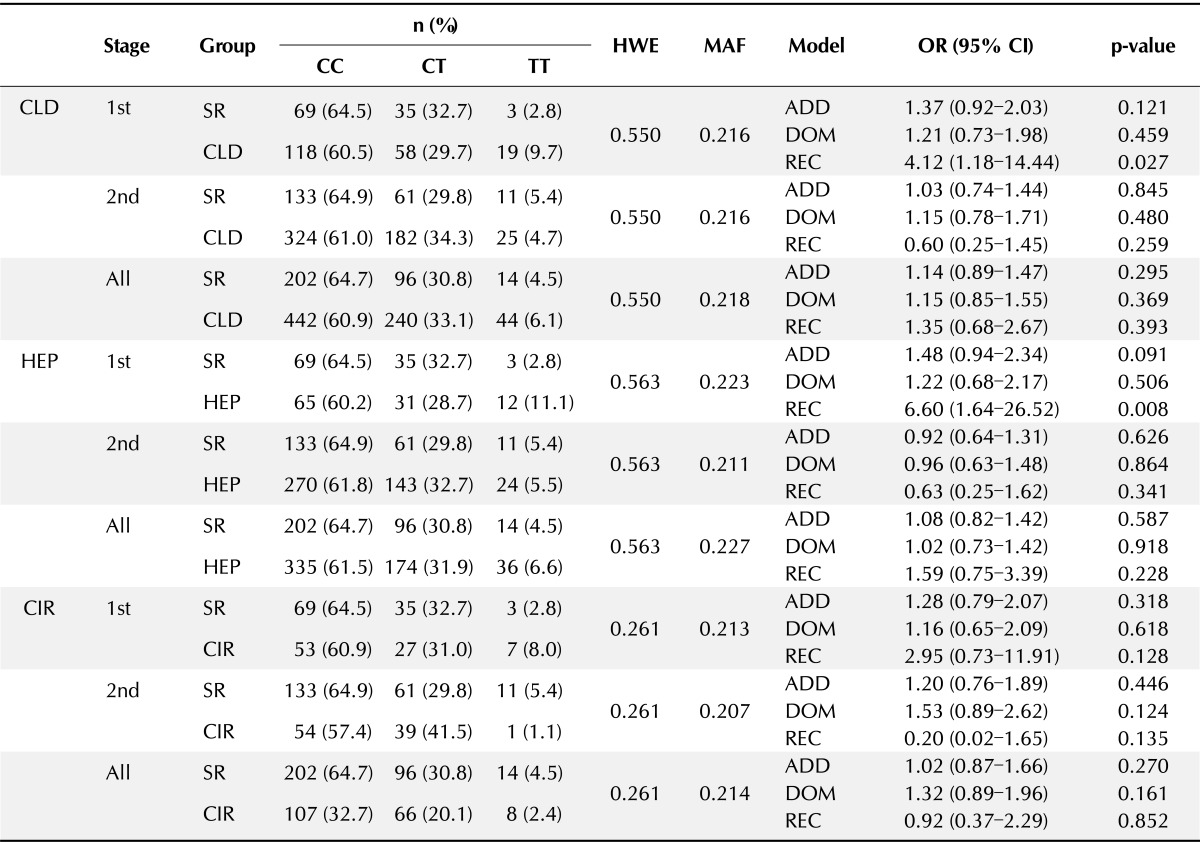

To replicate the significant associations of the SNP rs2808426, 736 samples, consisting of 205 SR, 437 HEP, and 94 CIR patients, were collected. The clinical information of the patients included in the analysis is summarized in Table 1. The second-stage genotyping was performed using the Taqman assay. The association of rs2808426 with CLD was assessed using the three genetic models, and multiple logistic regression with adjustment for gender and age was used as the first-stage analysis. The results of the genotype analysis of the second set of samples in association with CLD are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Multistage genotype analysis of rs2808426 (C > T) in IFI6 gene

HWE, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; MAF, minor allele frequency; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; CLD, chronic liver disease; SR, spontaneous recovery; HEP, chronic hepatitis B; CIR, Chronic liver disease; ADD, Additive; DOM, Dominant; REC, Recessive.

The significance of the results of the first genotype analysis was not maintained in the second genotype analysis. Furthermore, no significant associations were detected in a meta-analysis of the first-stage and second-stage samples (Table 4).

Discussion

The rs2808426 and rs10902662 SNPs are located in the 5' flanking region and the first intron of the IFI6 gene, respectively. These SNPs by themselves are known to regulate gene expression by causing alternative splicing or by changing the binding to a transcription factor or microRNA [21]. The presence of the rs2808426 SNP in the promoter region of IFI6 led us to screen for transcription factors with binding sites near or on rs2808426 (C > T). The binding of several transcription factors, including isoforms of the glucocorticoid receptor α, STAT4, v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog 1 (ETS1), and ETS2, to the protective allele (C) was predicted by ALLGEN PROMO (version 3.0.2; http://alggen.lsi.upc.es/cgi-bin/promo_v3/promo/promoinit.cgi?dirDB=TF_8.3) [27].

Interestingly, the binding of ETS1 to the region containing rs2808426 T was not predicted. Differential binding of ETS1 according to the genotype of rs2808426 may affect the expression of IFI6. IFI6 expression by type I IFNs triggers the formation of IFN-stimulated gene factor 3 (ISGF3) complexes containing activated STAT1/STAT2 and IFN regulatory factor 9 and their translocation into the nucleus, where they bind to the tandem IFN-stimulated regulatory element (ISRE) in the promoter of IFI6 [21, 28-31]. Tandem binding of ISGF3 to the ISRE is required for maximum expression of IFI6 [32], and the promoter region, including rs2808426, enhances IFI6 expression more than the ISRE region alone [21]. The ISGF3-binding site for the ISRE is separated from the ETS1-binding site by about 1.35 kb. The transcription factor ETS1 may regulate the expression of intracellular adhesion molecule-1 by protein-protein interaction with STAT1, which is a component of ISGF3 [33]. Overexpression of ETS1 in the MCF-7 breast cancer cell line enhances the expression of IFI6 up to 18.4-fold [34]. These data led us to speculate that the interaction between ETS1 and STAT1 in the ISGF3 complex may increase the expression of IFI6.

The present study investigated the association between the rs2808426 and rs10902662 polymorphisms of the IFI6 gene and the clearance of HBV in the Korean population by multistage comparison between the SR and CLD groups, including the HEP and CIR groups.

In the first stage of the analysis, significant associations between the rs2808426 and rs10902662 polymorphism genotypes and diplotypes were detected. A risk that was associated with the TT genotype in rs2808426 and rs10902662 was detected in the comparison between the SR and the CLD and HEP groups. Strong LD was found between the SNPs rs2808426 and rs10902662, containing most of the promoter region. In addition, diplotype analysis showed that the C-C HT was associated with a higher chance of SR than the T-T/T-T diplotype and that the C-C HT had a protective effect. The results of the first-stage analysis suggested that rs2808426 and rs10902662 may serve as candidate genetic screening markers for HBV clearance or that causative variants that are responsible for HBV clearance may be present in this LD block.

The association between IFI6 polymorphisms and HBV-induced chronic disease suggest that these polymorphisms might change the expression level of IFI6 according to transcription factor binding. Therefore, an increase in IFI6 expression that is associated with polymorphisms of the gene could inhibit the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria and block the transmission of the apoptosis signals through Bim in HBV-specific CD8+ T cells. HBV-specific CD8+ T cells would thus escape from antigen-induced apoptosis, proliferate, and then differentiate into activated CD8+ T cells to eliminate HBV from the host.

The results of the first-stage analysis suggested that IFI6 polymorphisms play a significant role. In previous studies, CD8+ T cell-related gene polymorphisms, such as those of secreted phosphoprotein 1, interleukin-18, and cyclin D2, were reported to affect the natural course of chronic HBV infections in the Korean population, but the effect of their genetic association is minor (OR, 0.69 to 1.44) [35, 36]. Furthermore, genomewide association studies of human leukocyte antigen (HLA) region polymorphisms, including HLA-DPA1, HLA-DPB1, and HLA-DQ, demonstrated their association with the chronicity of HBV [37-43]. In our first-stage analysis, the protective effect of the rs2808426 and rs10902662 polymorphisms was stronger than that reported previously in studies addressing the association with HBV (OR, 6.60). The genotype and diplotype distribution in both groups remained significant after multiple testing by Bonferroni's correction and permutation test. These results might support that genetic variation in IFI6 affects the clearance of HBV.

A second set of samples was used to replicate the results of the first-stage analysis. However, in the second association analysis, the comparison of the SR and the HEP and CIR groups did not yield significant results, even when merging the first- and second-stage samples in a meta-analysis. This could have been due to variation in the sampling cohort, environmental interactions, inadequate statistical power, or gene interactions [1, 44-49]. Furthermore, information on factors important for the progression of liver disease was lacking in the samples analyzed, such as data on alcohol consumption [50].

Although our data could not be reproduced, the results showing an association between IFI6 polymorphisms and HBV chronicity are significant. Our study is the first study to investigate the association between IFI6 polymorphisms and HBV clearance as an ISG. In addition, SR patients were used as controls instead of normal healthy subjects to show the effect of genomic background on the chronicity of HBV infection. Normal controls that never contracted HBV are not suitable to show the genetic effects.

Future studies should include a larger sample size and additional information in the replication study to validate the significance of the results through epistasis and environmental interactions. In addition, IFI6 promoter variations should be characterized using next-generation sequencing techniques, causal variants should be identified, and mechanisms underlying the effect of IFI6 on HBV clearance that is mediated by HBV antigen-specific CD8+ T cell survival need to be investigated.

In the present study, an initial discovery stage showed that the rs2808426 and rs10902662 genotypes and the corresponding diplotype were associated with a higher probability of HBV clearance in a Korean population. However, the results could not be replicated in a second stage with a different patient sample. Further studies should be aimed at showing how IFI6 affects HBV clearance by promoting HBV antigen-specific CD8+ T cell survival. Moreover, identification of causal variants in the IFI6 by including a large number of samples may help clarify the role of IFI6 on HBV clearance.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to every individual who gave us informed consent for this study. Informed consent was acquired from each patient, and the sampling protocols and informed consent forms used were approved by the IRB of Ajou University and Keiymung University. Protocols for handling the human genomic materials and all of the experimental procedures used were approved by the IRB of CHA University. This work was funded by grants from the Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (A010383, A080734), and the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2009-0093821).

References

- 1.Lok AS, McMahon BJ. Chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology. 2007;45:507–539. doi: 10.1002/hep.21513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee WM. Hepatitis B virus infection. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1733–1745. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thio CL, Thomas DL, Karacki P, Gao X, Marti D, Kaslow RA, et al. Comprehensive analysis of class I and class II HLA antigens and chronic hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol. 2003;77:12083–12087. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.22.12083-12087.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cha C, Dematteo RP. Molecular mechanisms in hepatocellular carcinoma development. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:25–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2004.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavanchy D. Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. J Viral Hepat. 2004;11:97–107. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2893.2003.00487.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheong JY. Management of chronic hepatitis B in treatment-naive patients. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2008;51:338–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park NH, Chung YH, Lee HS. Impacts of vaccination on hepatitis B viral infections in Korea over a 25-year period. Intervirology. 2010;53:20–28. doi: 10.1159/000252780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wieland SF, Eustaquio A, Whitten-Bauer C, Boyd B, Chisari FV. Interferon prevents formation of replication-competent hepatitis B virus RNA-containing nucleocapsids. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:9913–9917. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504273102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robek MD, Wieland SF, Chisari FV. Inhibition of hepatitis B virus replication by interferon requires proteasome activity. J Virol. 2002;76:3570–3574. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.7.3570-3574.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robek MD, Boyd BS, Wieland SF, Chisari FV. Signal transduction pathways that inhibit hepatitis B virus replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:1743–1747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308340100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thimme R, Wieland S, Steiger C, Ghrayeb J, Reimann KA, Purcell RH, et al. CD8(+) T cells mediate viral clearance and disease pathogenesis during acute hepatitis B virus infection. J Virol. 2003;77:68–76. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.68-76.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lopes AR, Kellam P, Das A, Dunn C, Kwan A, Turner J, et al. Bim-mediated deletion of antigen-specific CD8 T cells in patients unable to control HBV infection. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:1835–1845. doi: 10.1172/JCI33402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chisari FV, Isogawa M, Wieland SF. Pathogenesis of hepatitis B virus infection. Pathol Biol (Paris) 2010;58:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O'Connor L, Strasser A, O'Reilly LA, Hausmann G, Adams JM, Cory S, et al. Bim: a novel member of the Bcl-2 family that promotes apoptosis. Embo J. 1998;17:384–395. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.2.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bouillet P, Metcalf D, Huang DC, Tarlinton DM, Kay TW, Köntgen F, et al. Proapoptotic Bcl-2 relative Bim required for certain apoptotic responses, leukocyte homeostasis, and to preclude autoimmunity. Science. 1999;286:1735–1738. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5445.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kolumam GA, Thomas S, Thompson LJ, Sprent J, Murali-Krishna K. Type I interferons act directly on CD8 T cells to allow clonal expansion and memory formation in response to viral infection. J Exp Med. 2005;202:637–650. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McNair AN, Kerr IM. Viral inhibition of the interferon system. Pharmacol Ther. 1992;56:79–95. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(92)90038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu SY, Sanchez DJ, Cheng G. New developments in the induction and antiviral effectors of type I interferon. Curr Opin Immunol. 2011;23:57–64. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stark GR, Kerr IM, Williams BR, Silverman RH, Schreiber RD. How cells respond to interferons. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:227–264. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kelly JM, Porter AC, Chernajovsky Y, Gilbert CS, Stark GR, Kerr IM. Characterization of a human gene inducible by alpha- and beta-interferons and its expression in mouse cells. Embo J. 1986;5:1601–1606. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04402.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Porter AC, Chernajovsky Y, Dale TC, Gilbert CS, Stark GR, Kerr IM. Interferon response element of the human gene 6-16. Embo J. 1988;7:85–92. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1988.tb02786.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parker N, Porter AC. Identification of a novel gene family that includes the interferon-inducible human genes 6-16 and ISG12. BMC Genomics. 2004;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itzhaki JE, Barnett MA, MacCarthy AB, Buckle VJ, Brown WR, Porter AC. Targeted breakage of a human chromosome mediated by cloned human telomeric DNA. Nat Genet. 1992;2:283–287. doi: 10.1038/ng1292-283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Friedman RL, Manly SP, McMahon M, Kerr IM, Stark GR. Transcriptional and posttranscriptional regulation of interferon-induced gene expression in human cells. Cell. 1984;38:745–755. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90270-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cheriyath V, Glaser KB, Waring JF, Baz R, Hussein MA, Borden EC. G1P3, an IFN-induced survival factor, antagonizes TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human myeloma cells. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:3107–3117. doi: 10.1172/JCI31122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tahara E, Jr, Tahara H, Kanno M, Naka K, Takeda Y, Matsuzaki T, et al. G1P3, an interferon inducible gene 6-16, is expressed in gastric cancers and inhibits mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis in gastric cancer cell line TMK-1 cell. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2005;54:729–740. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0645-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farré D, Roset R, Huerta M, Adsuara JE, Roselló L, Albà MM, et al. Identification of patterns in biological sequences at the ALGGEN server: PROMO and MALGEN. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31:3651–3653. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghislain JJ, Wong T, Nguyen M, Fish EN. The interferon-inducible Stat2:Stat1 heterodimer preferentially binds in vitro to a consensus element found in the promoters of a subset of interferon-stimulated genes. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2001;21:379–388. doi: 10.1089/107999001750277853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bluyssen AR, Durbin JE, Levy DE. ISGF3 gamma p48, a specificity switch for interferon activated transcription factors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1996;7:11–17. doi: 10.1016/1359-6101(96)00005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schindler C, Levy DE, Decker T. JAK-STAT signaling: from interferons to cytokines. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:20059–20063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700016200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wesoly J, Szweykowska-Kulinska Z, Bluyssen HA. STAT activation and differential complex formation dictate selectivity of interferon responses. Acta Biochim Pol. 2007;54:27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li X, Leung S, Burns C, Stark GR. Cooperative binding of Stat1-2 heterodimers and ISGF3 to tandem DNA elements. Biochimie. 1998;80:703–710. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(99)80023-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yockell-Lelièvre J, Spriet C, Cantin P, Malenfant P, Heliot L, de Launoit Y, et al. Functional cooperation between Stat-1 and ets-1 to optimize icam-1 gene transcription. Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;87:905–918. doi: 10.1139/o09-055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Jung HH, Lee J, Kim JH, Ryu KJ, Kang SA, Park C, et al. STAT1 and Nmi are downstream targets of Ets-1 transcription factor in MCF-7 human breast cancer cell. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:3941–3946. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Shin HD, Park BL, Cheong HS, Yoon JH, Kim YJ, Lee HS. SPP1 polymorphisms associated with HBV clearance and HCC occurrence. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:1001–1008. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cheong JY, Cho SW, Oh B, Kimm K, Lee KM, Shin SJ, et al. Association of interleukin-18 gene polymorphisms with hepatitis B virus clearance. Dig Dis Sci. 2010;55:1113–1119. doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0819-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kamatani Y, Wattanapokayakit S, Ochi H, Kawaguchi T, Takahashi A, Hosono N, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies variants in the HLA-DP locus associated with chronic hepatitis B in Asians. Nat Genet. 2009;41:591–595. doi: 10.1038/ng.348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Howell JA, Visvanathan K. A novel role for human leukocyte antigen-DP in chronic hepatitis B infection: a genomewide association study. Hepatology. 2009;50:647–649. doi: 10.1002/hep.23147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cheriyath V, Leaman DW, Borden EC. Emerging roles of FAM14 family members (G1P3/ISG 6-16 and ISG12/IFI27) in innate immunity and cancer. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31:173–181. doi: 10.1089/jir.2010.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Brien TR, Kohaar I, Pfeiffer RM, Maeder D, Yeager M, Schadt EE, et al. Risk alleles for chronic hepatitis B are associated with decreased mRNA expression of HLA-DPA1 and HLA-DPB1 in normal human liver. Genes Immun. 2011;12:428–433. doi: 10.1038/gene.2011.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang L, Wu XP, Zhang W, Zhu DH, Wang Y, Li YP, et al. Evaluation of genetic susceptibility loci for chronic hepatitis B in Chinese: two independent case-control studies. PLoS One. 2011;6:e17608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guo X, Zhang Y, Li J, Ma J, Wei Z, Tan W, et al. Strong influence of human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-DP gene variants on development of persistent chronic hepatitis B virus carriers in the Han Chinese population. Hepatology. 2011;53:422–428. doi: 10.1002/hep.24048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mbarek H, Ochi H, Urabe Y, Kumar V, Kubo M, Hosono N, et al. A genome-wide association study of chronic hepatitis B identified novel risk locus in a Japanese population. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:3884–3892. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shriner D, Vaughan LK, Padilla MA, Tiwari HK. Problems with genome-wide association studies. Science. 2007;316:1840–1842. doi: 10.1126/science.316.5833.1840c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams SM, Canter JA, Crawford DC, Moore JH, Ritchie MD, Haines JL. Problems with genome-wide association studies. Science. 2007;316:1840–1842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ott J. Association of genetic loci: replication or not, that is the question. Neurology. 2004;63:955–958. doi: 10.1212/wnl.63.6.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ioannidis JP. Non-replication and inconsistency in the genome-wide association setting. Hum Hered. 2007;64:203–213. doi: 10.1159/000103512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pearson TA, Manolio TA. How to interpret a genome-wide association study. JAMA. 2008;299:1335–1344. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.11.1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lasky-Su J, Lyon HN, Emilsson V, Heid IM, Molony C, Raby BA, et al. On the replication of genetic associations: timing can be everything! Am J Hum Genet. 2008;82:849–858. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2008.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Greene CS, Penrod NM, Williams SM, Moore JH. Failure to replicate a genetic association may provide important clues about genetic architecture. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]