Abstract

Until recently, since the Human Genome Project, the general view has been that the majority of the human genome is composed of junk DNA and has little or no selective advantage to the organism. Now we know that this conclusion is an oversimplification. In April 2003, the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) launched an international research consortium called Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) to uncover non-coding functional elements in the human genome. The result of this project has identified a set of new DNA regulatory elements, based on novel relationships among chromatin accessibility, histone modifications, nucleosome positioning, DNA methylation, transcription, and the occupancy of sequence-specific factors. The project gives us new insights into the organization and regulation of the human genome and epigenome. Here, we sought to summarize particular aspects of the ENCODE project and highlight the features and data that have recently been released. At the end of this review, we have summarized a case study we conducted using the ENCODE epigenome data.

Keywords: chromatin, ENCODE, human genome, nucleosome positioning, regulatory elements

Introduction

The Human Genome Project was started in 1990 and completed by the International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium in April 2003 [1]. Even though the human whole genome sequencing was one of the biggest achievements in human genetics, still more remains to be done. In September 2003, the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) launched an international research group called Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE) to identify all functional regulatory regions across the entire human genome [2]. For this project, an international group of 442 members from 32 institutions studied 147 different types of cells with 24 types of different experiments (http://www.genome.gov/ENCODE) [3, 4]. The ENCODE project consists of a pilot and a technology development phase [5]. Methods used for the first phase were mainly chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) and quantitative PCR. A set of regions, corresponding to 30,000 kilobases (~1% of whole human genome), have been targeted [6]. The studies highlighted the success on characterizing functional elements in the human genome and were published in June 2007 in Nature [6] and Genome Research [7]. In the second phase of this project, several new advanced technologies were employed to gain higher accuracy and increase coverage. The key technology was so-called next-generation sequencing. Many software tools were developed within the ENCODE project, such as Clustered Aggregation Tool (CAGT) [8]. This tool has been applied to the datasets of chromatin marks and transcription factors to generate a comprehensive archive of histone modifications and nucleosome positioning around transcription factor binding sites. On September 5, 2012, the results of the ENCODE studies were published in 30 papers in Nature, Genome Research, and Genome Biology to express 5 years of progress toward the goal of the project [9]. The subjects of the ENCODE project to date include:

- Transcription factor motifs

- Chromatin patterns at transcription factor binding sites

- Characterization of intergenic regions and gene definition

- RNA and chromatin modification patterns around promoters

- Epigenetic regulation of RNA processing

- Noncoding RNA characterization

- DNA methylation patterns

- Enhancer discovery and characterization

- Three-dimensional connections across the genome

- Characterization of network topology

- Machine learning approaches to genomics

- Impact of functional information on understanding variation

- Impact of evolutionary selection on functional regions

All ENCODE information and data are freely available for immediate use.

What Did the ENCODE Discover about the Genome?

Accessible (open) chromatin

Until recently, it was generally believed that 80% of human genome was noncoding or junk DNA [10] and regulatory regions located in close proximity of genes to be expressed. The ENCODE project estimated that 2.94% of the whole human genome was protein coding, while 80.4% of sequences governed how those genes are regulated [11]. Open chromatin regions (nucleosome-depleted regions that are sensitive to cleavage by the DNase I enzyme) have been widely used to identify active DNA regulatory elements, including promoters, enhancers, silencers, insulators, and locus control regions [12, 13]. Open chromatin has been mapped by two approaches. A total of 2.89 million DNase hypersensitive sites (DHSs) mapped by DNase I digestion, followed by next-generation sequencing in 125 cell types and 4.8 million sites across 25 cell types that exhibited reduced nucleosomal crosslinking, were mapped based on formaldehyde-assisted isolation of regulatory elements assay [11]. On average, approximately 200,000 DHSs were found to be active in any one cell [14]. Open chromatin regions have different proportions, based on their genomic location, and they cover approximately 2% of the genome [15]. Open chromatin regions are enriched for regulatory information and located at or near transcription start sites [6].

DNA methylation and histone modification

The methylation status for the ENCODE cell lines has been obtained by three techniques: 1) sodium bisulfite conversion, 2) reduced representation bisulfite sequencing, and 3) methylation-sensitive restriction enzyme (methyl-seq). They profiled the DNA methylation status of over than one million CpG in all ENCODE cell lines and have provided quantitative determination of the proportion of CpG methylation at each site [5, 11, 16-18]. The result has added a lot to our present knowledge of cell-type selective patterns of methylation associated with genomic occupancy of transcriptions factors [17]. The ENCODE team has identified the specific patterns of post-translational histone modifications (e.g., H3K36me3, H3K27ac, and H3K27me3) by ChIP sequencing technique [6]. Then, histone modifications have been connected to the regulatory regions, such as promoters, enhancers, transcribe domains, and silenced regions [6, 11]. The maps of various histone modifications have been constructed genomewide in different cell lines.

Nucleosome positioning

In contrast to histone modifications, which are identified by ChIP-seq, nucleosome positioning data were generated without immunoprecipitation by using micrococcal nuclease digestion followed by sequencing [19-21]. The method that distinguishes nucleosome positioning is based on the ability of nucleosomes to protect related DNA from digestion by enzyme [22]. Protected fragments are sequenced to produce genomewide maps of nucleosome localization. By using a new tool, the ENCODE project has identified the differences in patterns of nucleosome positioning around the majority of transcription factor binding sites [8]. These data have tremendous value for analyzing the relationship between transcription factor binding, histone modifications, and gene expression regulation.

Transcription factors

Transcription factors can bind to DNA and alter the expression of genes [23]. The ENCODE Consortium has detected 45 million different events where transcription factors occupy DNA across 41 diverse cell types [16]. For this, high-throughput sequencing (ChIP-seq) technology was applied to create occupancy maps for binding sites for a variety of DNA binding factors [5]. The architecture of the network of human transcription factors was found to be quite complex [24].

Annotation of the outputs of genomewide association studies

A large number of polymorphisms associated with increased risks of certain diseases or particular quantitative traits have been discovered by genomewide association studies. The identified genetic markers or risk variants, mostly composed of single nucleotide polymorphisms, were enriched within the genomic regions that were previously thought to be 'junk DNA' [11, 16, 17, 24-28]. The results of the ENCODE project have demonstrated that variants that fall in regulatory regions could indirectly influence coding genes linked to diseases or clinical traits. With the DHS map in hand, a research group studied more than 5,500 genome-wide association study (GWAS) single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). The result of their research revealed that approximately 75% of GWAS diseases- and trait-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). are concentrated in or near DNase I hypersensitive sites [29]. Together, they give new insights to the researchers who are carrying out GWASs.

A case epigenomic study based on the ENCODE data

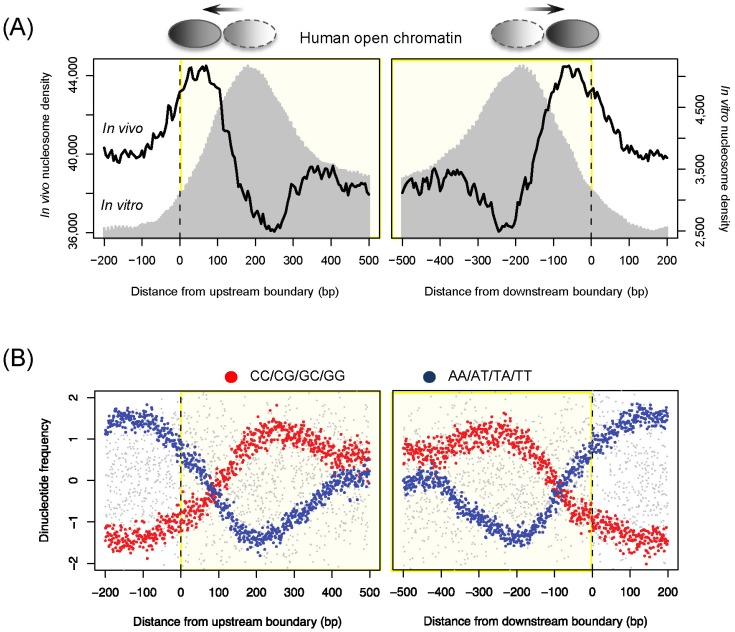

All ENCODE data are freely available for download and analysis. The ENCODE website at the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) genome browser (http://encodeproject.org or http://genome.ucsc.edu/ENCODE) provides information about how to access the data. More than 100 researchers who were not part of the ENCODE project have used the ENCODE data for their studies. We had a question about the conflicts between the openness of transcription factor binding regions and the existence of histones for various modifications. Whereas regulatory DNA elements underlying open chromatin are made accessible by nucleosome-depleted states, the presence of nucleosomes is required for specific histone modifications that mediate the specific regulation of open chromatin regions [30]. To handle this question, we downloaded the data for chromatin accessibility (DHS), in vivo nucleosome occupancy, 15 chromatin states, histone modifications, and transcription factor binding sites for the GM12878 lymphoblastoid cell line from the ENCODE tracks of the UCSC genome browser. We discovered the presence of boundary nucleosomes just inside of open chromatin (black curve in Fig. 1A). In vivo nucleosomes that were reconstituted purely based on naked DNA [21, 31] also peaked right inside of open chromatin (gray shade in Fig. 1A). The corresponding DNA sequences displayed an increase in the C/G dinucleotide frequency (red dots in Fig. 1B) and a significant decrease in the A/T dinucleotide frequency (blue dots in Fig. 1B), exhibiting nucleosome-favoring features. However, there was a difference in the peak position between the in vivo and in vitro nucleosomes, indicating cellular reprogramming of sequence-encoded nucleosome positioning. The similar patterns were found in yeast (data not shown here). This evolutionarily conserved feature provides a platform for histone modifications associated with promoters and enhancers. We examined histone modification levels for the regulatory areas whose borders were occupied by DNA-encoded nucleosomes and those that were free of nucleosome sequences. Among 15 different chromatin states [30], active promoters, poised promoters, and strong enhancers tended to contain nucleosome-encoding sequences. Highest enrichment was found for poised promoters, and the lowest percentage was found with heterochromatin states. All these data indicate intrinsic nucleosome positioning present in the regulatory regions that are frequently accessed or poised for later activation but are not supposed to be silent. As with other ENCODE data users, the main goal of our study was to add a few more new directions to the ENCODE epigenetics road map.

Fig. 1.

Sequenced-directed positioning of boundary nucleosome in open chromatin. (A) In vivo (black curve) and in vitro (gray shade) nucleosome occupancy across open chromatin in human GM12878 lymphoblastoid cell line. (B) Normalized frequencies of C/G and A/T dinucleotides across the boundaries of open chromatin.

Conclusion

The ENCODE project results have dramatically increased our knowledge about chromatin and its regulation. The results have forced us to think better about genetics. The ENCODE consortium has developed multiple technologies and approaches to discover the functional elements encoded in the human genome. This project generated more than 15 trillion bytes of raw data, mapping diverse chromatin properties in several cell types. Data generated by the ENCODE project are freely available and have been used by many researchers. By using the ENCODE data, we discovered the presence of boundary nucleosomes for specific histone modifications in open chromatin. Although the ENCODE project has provided a unique and informative window through which to view evolutionary change, it has looked only at 147 types of cells, and the human body has 1,000 cell types. The project is just the start of a long journey to understanding the mysteries of our genome.

References

- 1.International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature. 2004;431:931–945. doi: 10.1038/nature03001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.ENCODE Project Consortium. The ENCODE (ENCyclopedia Of DNA Elements) Project. Science. 2004;306:636–640. doi: 10.1126/science.1105136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alberts B. The end of "small science"? Science. 2012;337:1583. doi: 10.1126/science.1230529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Decoding ENCODE. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:871. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.ENCODE Project Consortium. Myers RM, Stamatoyannopoulos J, Snyder M, Dunham I, Hardison RC, et al. A user's guide to the encyclopedia of DNA elements (ENCODE) PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1001046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.ENCODE Project Consortium. Birney E, Stamatoyannopoulos JA, Dutta A, Guigó R, Gingeras TR, et al. Identification and analysis of functional elements in 1% of the human genome by the ENCODE pilot project. Nature. 2007;447:799–816. doi: 10.1038/nature05874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weinstock GM. ENCODE: more genomic empowerment. Genome Res. 2007;17:667–668. doi: 10.1101/gr.6534207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kundaje A, Kyriazopoulou-Panagiotopoulou S, Libbrecht M, Smith CL, Raha D, Winters EE, et al. Ubiquitous heterogeneity and asymmetry of the chromatin environment at regulatory elements. Genome Res. 2012;22:1735–1747. doi: 10.1101/gr.136366.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Maher B. ENCODE: the human encyclopaedia. Nature. 2012;489:46–48. doi: 10.1038/489046a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Karlin S, McGregor J. The evolutionary development of modifier genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1972;69:3611–3614. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.12.3611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.ENCODE Project Consortium. Dunham I, Kundaje A, Aldred SF, Collins PJ, Davis CA, et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:57–74. doi: 10.1038/nature11247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cockerill PN. Structure and function of active chromatin and DNase I hypersensitive sites. FEBS J. 2011;278:2182–2210. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song L, Zhang Z, Grasfeder LL, Boyle AP, Giresi PG, Lee BK, et al. Open chromatin defined by DNaseI and FAIRE identifies regulatory elements that shape cell-type identity. Genome Res. 2011;21:1757–1767. doi: 10.1101/gr.121541.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ecker JR, Bickmore WA, Barroso I, Pritchard JK, Gilad Y, Segal E. Genomics: ENCODE explained. Nature. 2012;489:52–55. doi: 10.1038/489052a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Natarajan A, Yardimci GG, Sheffield NC, Crawford GE, Ohler U. Predicting cell-type-specific gene expression from regions of open chromatin. Genome Res. 2012;22:1711–1722. doi: 10.1101/gr.135129.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Neph S, Vierstra J, Stergachis AB, Reynolds AP, Haugen E, Vernot B, et al. An expansive human regulatory lexicon encoded in transcription factor footprints. Nature. 2012;489:83–90. doi: 10.1038/nature11212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Thurman RE, Rynes E, Humbert R, Vierstra J, Maurano MT, Haugen E, et al. The accessible chromatin landscape of the human genome. Nature. 2012;489:75–82. doi: 10.1038/nature11232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang H, Maurano MT, Qu H, Varley KE, Gertz J, Pauli F, et al. Widespread plasticity in CTCF occupancy linked to DNA methylation. Genome Res. 2012;22:1680–1688. doi: 10.1101/gr.136101.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson SM, Tan FJ, McCullough HL, Riordan DP, Fire AZ. Flexibility and constraint in the nucleosome core landscape of Caenorhabditis elegans chromatin. Genome Res. 2006;16:1505–1516. doi: 10.1101/gr.5560806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valouev A, Ichikawa J, Tonthat T, Stuart J, Ranade S, Peckham H, et al. A high-resolution, nucleosome position map of C. elegans reveals a lack of universal sequence-dictated positioning. Genome Res. 2008;18:1051–1063. doi: 10.1101/gr.076463.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Valouev A, Johnson SM, Boyd SD, Smith CL, Fire AZ, Sidow A. Determinants of nucleosome organization in primary human cells. Nature. 2011;474:516–520. doi: 10.1038/nature10002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carey M, Smale ST. Micrococcal nuclease-Southern blot assay: I. MNase and restriction digestions. CSH Protoc. 2007;2007:pdb.prot4890. doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot4890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee TI, Young RA. Transcription of eukaryotic protein-coding genes. Annu Rev Genet. 2000;34:77–137. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.34.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gerstein MB, Kundaje A, Hariharan M, Landt SG, Yan KK, Cheng C, et al. Architecture of the human regulatory network derived from ENCODE data. Nature. 2012;489:91–100. doi: 10.1038/nature11245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Boyle AP, Hong EL, Hariharan M, Cheng Y, Schaub MA, Kasowski M, et al. Annotation of functional variation in personal genomes using RegulomeDB. Genome Res. 2012;22:1790–1797. doi: 10.1101/gr.137323.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaub MA, Boyle AP, Kundaje A, Batzoglou S, Snyder M. Linking disease associations with regulatory information in the human genome. Genome Res. 2012;22:1748–1759. doi: 10.1101/gr.136127.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vernot B, Stergachis AB, Maurano MT, Vierstra J, Neph S, Thurman RE, et al. Personal and population genomics of human regulatory variation. Genome Res. 2012;22:1689–1697. doi: 10.1101/gr.134890.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spivakov M, Akhtar J, Kheradpour P, Beal K, Girardot C, Koscielny G, et al. Analysis of variation at transcription factor binding sites in Drosophila and humans. Genome Biol. 2012;13:R49. doi: 10.1186/gb-2012-13-9-r49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Maurano MT, Humbert R, Rynes E, Thurman RE, Haugen E, Wang H, et al. Systematic localization of common disease-associated variation in regulatory DNA. Science. 2012;337:1190–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.1222794. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ernst J, Kheradpour P, Mikkelsen TS, Shoresh N, Ward LD, Epstein CB, et al. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature. 2011;473:43–49. doi: 10.1038/nature09906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kaplan N, Moore IK, Fondufe-Mittendorf Y, Gossett AJ, Tillo D, Field Y, et al. The DNA-encoded nucleosome organization of a eukaryotic genome. Nature. 2009;458:362–366. doi: 10.1038/nature07667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]