Abstract

Proteins in DNAJ/K families are ubiquitous, from prokaryotes to eukaryotes, and function as molecular chaperones. For systematic phylogenomics of the DNAJ/K families, we developed the Eukaryotic DNAJ/K Database (EDD). A total of 12,908 DNAJs and 4,886 DNAKs were identified from 339 eukaryotic genomes in the EDD. Kingdom-wide comparison of DNAJ/K families provides new insights on the evolutionary relationship within these families. Empowered by 'class', 'cluster', and 'taxonomy' browsers and the 'favorite' function, the EDD provides a versatile platform for comparative genomic analyses of DNAJ/K families.

Keywords: database, HSP40 heat-shock proteins, HSP70 heat-shock proteins

Introduction

Ubiquitous heat shock proteins (HSPs) play essential roles as molecular chaperones that protect cells through protein folding as a stress response under heat shock [1]. The HSPs are well conserved in all eukaryotes and prokaryotes [2]. The HSPs are classified on the basis of their approximate molecular mass (e.g., the 70-kDa species is the Hsp70 family). DNAJ and DNAK are members of the Hsp40 and Hsp70 families, respectively [3]. These proteins are known to cooperate in many cellular processes, such as DNA replication, protein folding, protein export, and stress response in an ATP hydrolysis-dependent manner [4-6]. The cooperation of DNAJ and DNAK is dependent on the interactions between the J domain of DNAJ and the ATPase domain of DNAK [7].

DNAJ proteins were classified using the J, zinc finger, and carboxy-terminal domains [8]. Type I DNAJs contain all three domains, while type II proteins have a J domain linked directly to a carboxy-terminal domain without a zinc finger domain. The type III proteins include only the J domain. However, such domain architectures of DNAJ were not deliberated on most eukaryotic genome annotations, which might cause overestimation of DNAJ entries [9, 10]. Likewise, many studies of DNAKs have been used without any unified nomenclature or notation [11, 12], although ATPase and peptide-binding domains had been defined [13]. Recent classifications and identifications based on functional domains of the DNAJ/K families revealed 22, 89, and 41 DNAJs [9, 10, 14], and 14, 18, and 17 DNAKs [11, 12, 15] in the yeast, Arabidopsis, and human genomes, respectively. However, there is no informative platform that archives the previously identified DNAJ/Ks. Furthermore, only a few genomes have systematically identified DNAJ/K families, although hundreds of genomic sequences are publicly available. This problematic circumstance has demanded the development of a comprehensive platform that archives sequence information, classifies them according to their domain structures, and analyzes them using bioinformatics tools. The platform should provide user-friendly interfaces and easy access. Therefore, we developed a web-based phylogenomic platform called the Eukaryotic DNAJ/K Database (EDD).

Methods and Results

Identification and classification of DNAJ/K family from 339 eukaryotic genomes

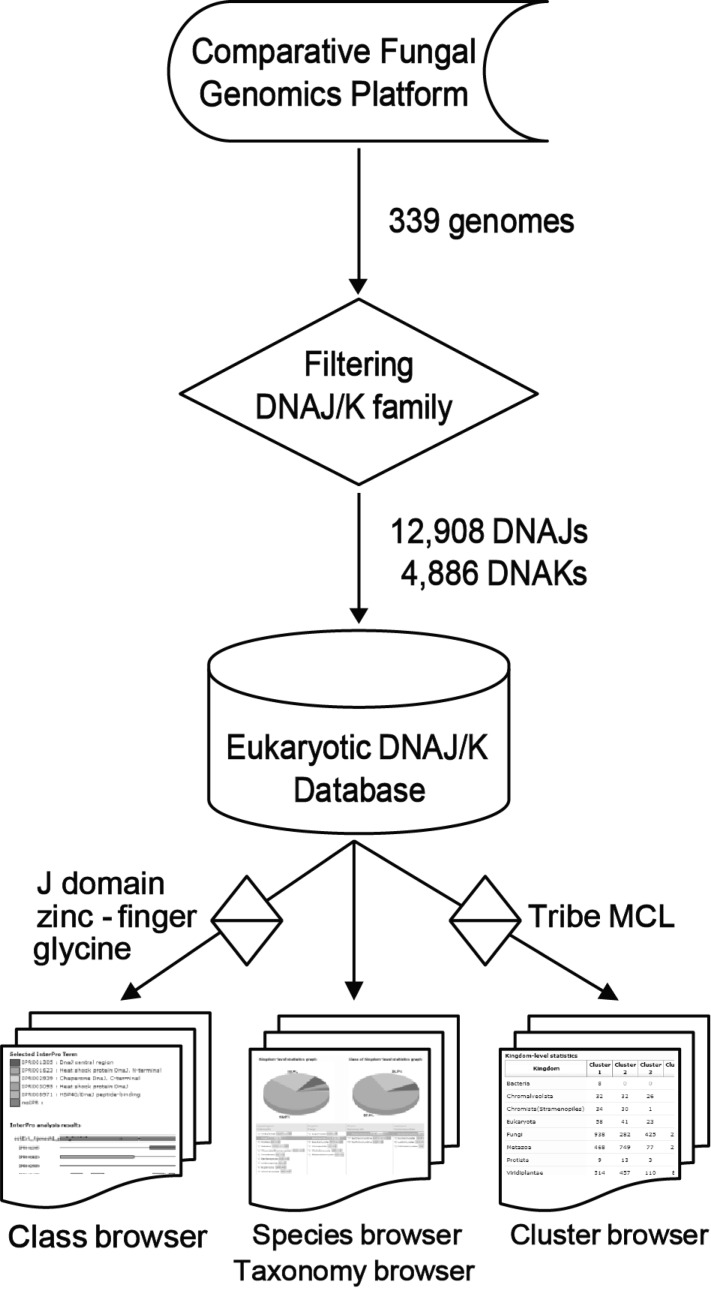

An automated pipeline was programmed to identify and classify the DNAJ/K families (Fig. 1). All protein sequences of the 339 genomes deposited in the Comparative Fungal Genomics Platform (CFGP; http://cfgp.snu.ac.kr) [16] were filtered according to the following description. Six InterPro terms (release 12.0) for DNAJ (IPR012724, IPR008971, IPR003095, IPR001305, IPR002939, and IPR001623) and three for DNAK (IPR013126, IPR001023, and IPR012725) were used to retrieve corresponding sequences. When the J domain or any of the DNAK domains was at least 50 amino acids (aa), it was defined as 'putative', and the others were tagged as 'candidate DNAJ/Ks'. The HPD tripeptide motif and glycine-rich region were identified from the 'putative DNAJ' sequences. The DNAK family was clustered by sequence similarity (BLAST E-value cutoff e-5) using the Tribe Markov clustering (MCL) algorithm [17], because no class has been made in this family. Finally, 12,908 DNAJs and 4,886 DNAKs were identified and deposited into EDD. In the DNAJ family, 895, 3,172, and 8,700 proteins were classified as type I, II, and III, respectively. Twenty-one clusters were determined in DNAK, and 4,853 proteins (99.1%) belonged to the first four clusters.

Fig. 1.

System architecture and data processing pipeline in the Eukaryotic DNAJ/K Database. MCL, Markov clustering.

Web-based interfaces of the EDD

First, all protein and nucleic acid sequences identified as DNAJ/Ks can be accessed according to class, species, and cluster through user-friendly interfaces, such as the 'class' and 'cluster' browsers on the EDD website. For example, statistics pages of each class were displayed using tables and diagrams in the 'class' browser. The statistics pages are automatically updated when new data are added to the EDD. Secondly, the EDD allows users to browse the detailed information on DNAJ/Ks and to analyze it via 'favorite'. It is a customized cyber-workbench where users can create folders, store favored items, and perform 10 bioinformatics analyses, such as BLAST search, BLASTMatrix, ClustalW, DNAJ/K statistics, a DNAJ class viewer, a DNAJ/K domain viewer, and a glycine ratio viewer. Especially, 'favorite', implemented in the EDD, is specialized for the functional analysis of DNAJ/K proteins (e.g., DNAJ/K domain view). The data saved in 'favorite' can be shared with CFGP 2.0 for further comparative analysis [16]. Finally, a highlighted function of the EDD is a 'taxonomy' browser powered by the 'Species-driven User Interface', which provides an interactive interface for displaying the taxonomical hierarchy for DNAJ/Ks. Users can drag and drop any taxon or taxa and perform sequence download, statistics, class and cluster analyses, ClustalW alignment, and BLAST search.

Conclusion

The comprehensive information on DNAJ/Ks conserved in 339 genomes over seven phyla is a useful resource for molecular chaperone studies in eukaryotes. Phylogenetic analysis between phyla or kingdoms as well as genomic analysis within a species can be performed in the EDD. The user-friendly web interfaces and various analysis tools implemented in this database will accelerate the management of large-scale data. The EDD will be a novel platform for phylogenomic studies and a model for comprehensive genomic analyses.

Acknowledgments

The National Research Foundation of Korea (2012-0001149 and 2012-0000141), the TDPAF (309015-04-SB020), and the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program of Rural Development Administration in Korea (PJ00821201) grants to Y.-H. Lee. K. Cheong is grateful for a graduate fellowship through the Brain Korea 21 Program.

References

- 1.Hendrick JP, Hartl FU. Molecular chaperone functions of heat-shock proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:349–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindquist S, Craig EA. The heat-shock proteins. Annu Rev Genet. 1988;22:631–677. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.003215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Georgopoulos C, Welch WJ. Role of the major heat shock proteins as molecular chaperones. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:601–634. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.003125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Langer T, Lu C, Echols H, Flanagan J, Hayer MK, Hartl FU. Successive action of DnaK, DnaJ and GroEL along the pathway of chaperone-mediated protein folding. Nature. 1992;356:683–689. doi: 10.1038/356683a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wild J, Altman E, Yura T, Gross CA. DnaK and DnaJ heat shock proteins participate in protein export in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 1992;6:1165–1172. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.7.1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yochem J, Uchida H, Sunshine M, Saito H, Georgopoulos CP, Feiss M. Genetic analysis of two genes, dnaJ and dnaK, necessary for Escherichia coli and bacteriophage lambda DNA replication. Mol Gen Genet. 1978;164:9–14. doi: 10.1007/BF00267593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greene MK, Maskos K, Landry SJ. Role of the J-domain in the cooperation of Hsp40 with Hsp70. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:6108–6113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheetham ME, Caplan AJ. Structure, function and evolution of DnaJ: conservation and adaptation of chaperone function. Cell Stress Chaperones. 1998;3:28–36. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(1998)003<0028:sfaeod>2.3.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Qiu XB, Shao YM, Miao S, Wang L. The diversity of the DnaJ/Hsp40 family, the crucial partners for Hsp70 chaperones. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2560–2570. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6192-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walsh P, Bursać D, Law YC, Cyr D, Lithgow T. The J-protein family: modulating protein assembly, disassembly and translocation. EMBO Rep. 2004;5:567–571. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brocchieri L, Conway de Macario E, Macario AJ. hsp70 genes in the human genome: conservation and differentiation patterns predict a wide array of overlapping and specialized functions. BMC Evol Biol. 2008;8:19. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-8-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin BL, Wang JS, Liu HC, Chen RW, Meyer Y, Barakat A, et al. Genomic analysis of the Hsp70 superfamily in Arabidopsis thaliana. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001;6:201–208. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0201:gaoths>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhu X, Zhao X, Burkholder WF, Gragerov A, Ogata CM, Gottesman ME, et al. Structural analysis of substrate binding by the molecular chaperone DnaK. Science. 1996;272:1606–1614. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miernyk JA. The J-domain proteins of Arabidopsis thaliana: an unexpectedly large and diverse family of chaperones. Cell Stress Chaperones. 2001;6:209–218. doi: 10.1379/1466-1268(2001)006<0209:tjdpoa>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahsen, Pfanner Molecular chaperones: towards a characterization of the heat-shock protein 70 family. Trends Cell Biol. 1997;7:129–133. doi: 10.1016/S0962-8924(96)10056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park J, Park B, Jung K, Jang S, Yu K, Choi J, et al. CFGP: a web-based, comparative fungal genomics platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008;36:D562–D571. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enright AJ, Van Dongen S, Ouzounis CA. An efficient algorithm for large-scale detection of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:1575–1584. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.7.1575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]