Abstract

The fundamental processes of membrane fission and fusion determine size and copy numbers of intracellular organelles. While SNARE proteins and tethering complexes mediate intracellular membrane fusion, fission requires the presence of dynamin or dynamin-related proteins. Here we study these reactions in native yeast vacuoles and find that the yeast dynamin homolog Vps1 is not only an essential part of the fission machinery, but also controls membrane fusion by generating an active Qa SNARE- tethering complex pool, which is essential for trans-SNARE formation. Our findings provide new insight into the role of dynamins in membrane fusion by directly acting on SNARE proteins.

Introduction

Both size and copy number of intracellular organelles can alter in reproducible ways upon changes in environmental conditions or in response to the cell cycle. Examples of these organelles include endosomes, lysosomes, vacuoles and mitochondria1–3. Critical for the determination of the organelle size is the magnitude of ongoing fusion and fission reactions, which must be tightly regulated. Membrane fusion in the endomembrane system involves cognate sets of v- (vesicular or R) and t- (target or Qa, Qb and Qc) SNAREs. SNAREs from two fusing membranes form trans-complexes between the membranes4–7. Many tethers, like the vacuolar HOPS complex, physically interact with SNAREs and may stimulate the formation of trans-SNARE complexes by bringing the opposing membranes in closer contact8,9. In addition to tethering complexes, many other proteins have been identified to interact with SNAREs, including Munc13, V-ATPase, dynamins, complexins, synaptotagmins and Sec1/Munc18 proteins10,11. How these proteins help to coordinate the SNARE mediated fusion process with the antagonistic membrane fission reaction is an area, which has remained unexplored.

It is not clear whether the fission machinery for different organelles is related, or fission occurs in unique, organelle-specific ways. One potential common factor is dynamin-like GTPases, which are important for vacuolar and mitochondrial fission2, 3. Under suitable conditions, dynamins form spiral- or ring-like collars on artificial liposomes leading to their tubulation and fragmentation upon GTP hydrolysis12–14. The GTPase effector domain and the middle domain of dynamin have been shown to be needed for self-assembly and allosteric regulation of the GTPase activity13,15. Interestingly, recent studies have revealed the involvement of dynamin in granular exocytosis16. In an earlier study we showed a dual function of the dynamin like protein, Vps1 in membrane fission and fusion17 however, the underlying molecular mechanism allowing Vps1 to regulate both processes has remained unexplored. Here, we investigate the molecular mechanism of how Vps1 controls membrane fusion and coordinates fusion with the antagonistic fission process.

Results

Vps1 controls trans-SNARE formation

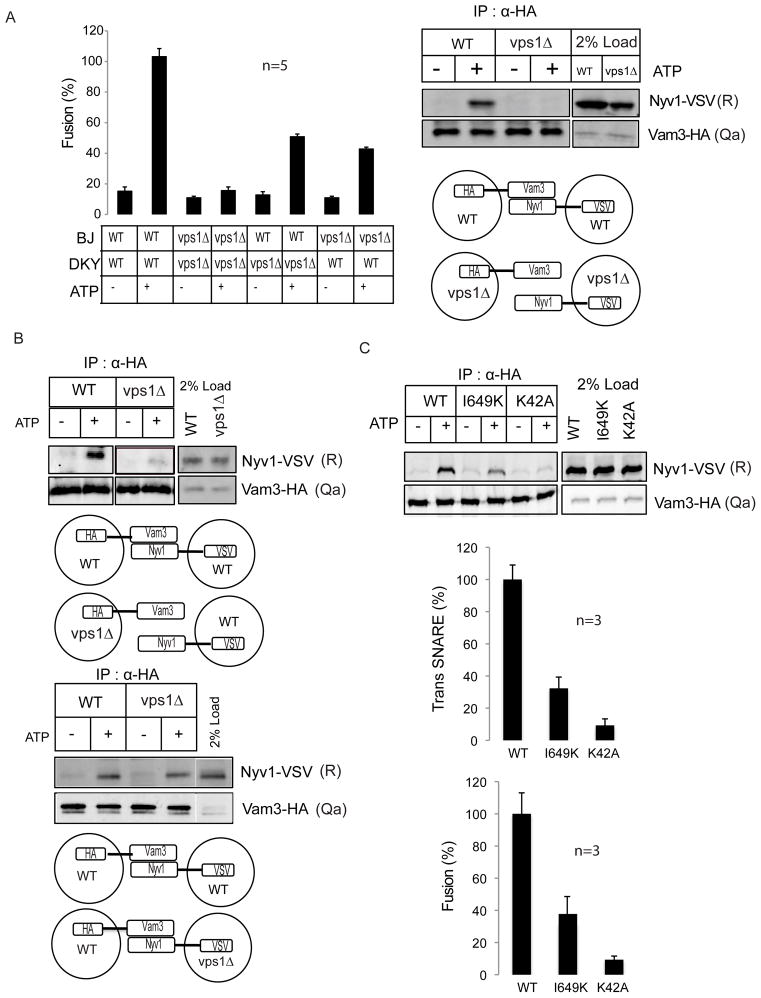

Vacuoles purified from vps1Δ strains are fusion-incompetent17. In contrast to pure vps1Δ fusions, mixed fusions employing wild type and vps1Δ vacuoles displayed considerable fusion activity (~50% of wild type levels, Fig.1A). Fusion efficiency was determined by measuring alkaline phosphatase activity (ALP); pro-ALP in the BJ vacuoles is activated by maturation enzymes contained in DKY vacuoles17. Since trans SNARE complex formation is essential for successful fusion, we asked first whether the absence of trans-SNARE formation accounts for the fusion defect of vps1Δ vacuoles. Yeast vacuoles harbor four SNAREs that are required for their fusion18. The Qa SNARE Vam3, the Qb SNARE Vti1, the Qc SNARE Vam7 and the R-SNARE Nyv1 form the trans-SNARE complexes necessary for fusion. A characteristic feature of vacuolar fusion is its homotypic architecture, meaning that both fusion partners harbor the same SNARE composition on their respective surfaces18. To analyze trans-SNARE complex formation, we tagged either Nyv1 or Vam3 on wild type and vps1Δ vacuoles. Addition of the HA or VSV tag to the C-terminus did not impair SNARE function (Supplementary Fig. S1A). Priming and docking occur in the presence of ATP. Accordingly, no trans-SNARE interactions were detectible in the absence of ATP. When Vam3-HA was precipitated from wild type vacuoles in the presence of ATP, Nyv1-VSV co-precipitated from wild type vacuoles, indicating that normal trans-SNARE formation had occurred (Fig.1A). However, when Vam3-HA was precipitated from vps1Δ vacuoles, no co-precipitating Nyv1-VSV could be detected suggesting that Vps1 might be an essential factor for successful trans-SNARE formation.

Figure 1. Vps1 controls trans-SNARE formation.

(A) Vacuoles derived from wild type (BJ & DKY) and vps1Δ (BJ & DKY) strains were incubated under standard fusion condition. Mixed fusions containing wild type and vps1Δ vacuoles displayed 50% fusion activity when compared to pure wild type fusions. Five independent experiments are shown as means +/− S.D. Vacuoles harboring either Vam3-HA or Nyv1-VSV were isolated from wild type and vps1Δ yeast cells. Trans-SNARE assays were performed as described in the Methods section. Vacuoles purified from vps1Δ vacuoles do not establish trans-SNAREs.

(B) Vacuoles harboring either Vam3-HA or Nyv1-VSV were isolated from wild type and vps1Δ yeast cells. Trans-SNARE assays were performed as mentioned in the Methods section. In the top panel, trans-SNARE formation of Vam3-HA tagged vacuoles derived from wild type or vps1Δ strains with Nyv1-VSV tagged vacuoles purified from wild type cells are displayed. In the bottom panel, Vam3-HA tagged vacuoles from wild type cells were mixed with wild type or vps1Δ vacuoles harboring Nyv1-VSV. On vps1Δ vacuoles only the Qa SNARE Vam3 but not the R-SNARE Nyv1 is impaired in its capability to enter into trans-SNARE complexes.

(C) Vacuoles purified from wild type, I649K and K42A strains harboring Vam3-HA or Nyv1-VSV were examined for trans-SNARE complex formation. Means ± S.D. of three independent experiments are shown. Vacuoles purified from wild type, I649K and K42A strains were examined for fusion activity as described in the Methods section. Three independent experiments are shown as means +/− S.D.

An earlier study showed that Vps1 controls Vam3 function17. Moreover, mixed fusions between wild type and vps1Δ vacuoles retained 50 % of fusion activity (Fig. 1A) suggesting that not all SNAREs are functionally affected by the vps1Δ mutation. Therefore, we asked what topology of trans-SNARE complex formation might account for the mixed fusion array. Again, when Vam3-HA was precipitated from wild type vacuoles upon addition of ATP, Nyv1-VSV co-precipitated from wild type vacuoles, indicating that normal trans-SNARE formation had occurred (Fig. 1B top panel). However, when Vam3-HA was originating from vps1Δ vacuoles, Nyv1-VSV did not co-precipitate even from wild type vacuoles (Fig. 1B top panel). Another picture emerged when Vam3-HA was precipitated from wild type vacuoles. In this case, Nyv1-VSV from wild type or vps1Δ vacuoles was able to interact in trans with Vam3-HA from wild type vacuoles (Fig. 1B bottom panel). These data suggest that the vps1Δ phenotype does not lead to a general disability of all vacuolar SNAREs, but specifically hits the Qa SNARE Vam3 in its function to enter into trans-SNARE complexes, further confirming the role of Vps1 in controlling Vam3 activity during membrane fusion.

Next we tested whether point mutations in Vps1 might confer defects on vacuolar fusion and trans-SNARE complex formation. The K42A mutation leads to a GTP-hydrolysis defective Vps1 protein19–21 and the I649 mutation affects the self-assembly of Vps122, 23 (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Vacuoles purified from these strains exhibited dramatically reduced fusion activity and concomitantly little or no trans-SNARE complex formation (Fig. 1C). These data suggest that the amount of trans-SNARE complex formation is directly connected to the physical state of Vps1. In order to promote efficient trans-SNARE formation, Vps1 needs to hydrolyze GTP and has to be present in a polymeric state.

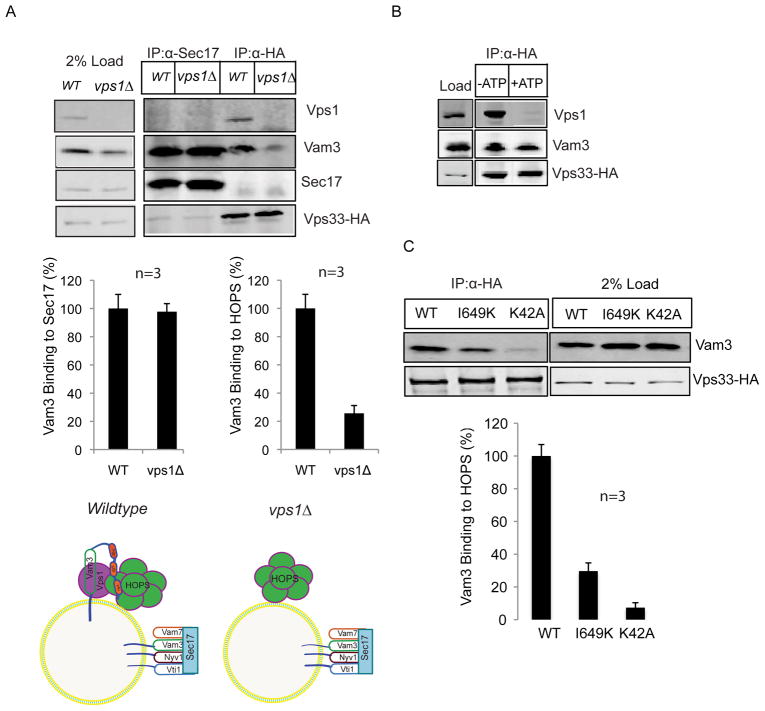

The interaction of the Qa SNARE Vam3 with HOPS requires Vps1

To further elucidate the molecular impact of Vps1 mutations on the function of Vam3 in vacuolar fusion and trans-SNARE establishment, we investigated the abundance of different Vam3 pools on wild type and vps1Δ vacuoles. Vam3 can reside in different states on the vacuolar surface, either as a single SNARE bound to the tethering complex HOPS or interacting with the NSF/Sec18 adapter protein Sec17/α-SNAP and other SNAREs as part of vacuolar cis-SNARE complexes24. We selectively precipitated Sec17 and Vps33 from detergent extracted wild type and vps1Δ vacuoles using antibodies specific for Sec17 or the HA-extension of Vps33. Vps33 is the vacuolar SM-protein and an integral part of the HOPS complex25. Addition of the HA-extension to the C-terminus did not impair Vps33 function (Supplementary Fig. S2). We found Vps1 to be significantly enriched in the Vps33-HA fraction precipitated from wild type detergent extracts and almost totally absent in the Sec17 pull down (Fig. 2A). A significantly lower level of Vam3 co-precipitated with Vps33-HA in vps1Δ vacuoles when compared to wild type Vps33-HA precipitations, although the total amount of precipitated Vps33 was almost equal (Fig. 2A). However, the amount of Vam3 associated with Sec17 in vps1Δ vacuoles was comparable to wild type levels. This suggests that only in the presence of Vps1, Vam3 is able to interact with the HOPS-complex and is not exclusively found in Sec17-associated cis-SNARE complexes (Fig. 2A). SNAREs must interact with the tethering complex HOPS in order to establish trans-SNARE complexes25–27. We found that Vam3 is associated with the HOPS complex and Vps1 (Fig. 2B). However the composition of this complex was changed upon addition of ATP. When Vps33-HA was precipitated from wild type vacuoles in the presence of ATP, Vps1 was released from the Vam3-HOPS complex (Fig. 2B). Most likely this reaction is controlled by NSF/Sec18, since temperature inactivation of this ATPase led to impaired release activity of Vps1 from the Vam3-HOPS complex (Supplementary Fig. S3). Based on the observation that Vps1 controls SNARE-HOPS associations and trans-SNARE formation, we determined whether mutations in Vps1 might affect these interactions. We measured the Qa-SNARE density on the HOPS complex by precipitating Vps33-HA from wild type and mutant vacuoles. Interestingly, we detected a correlation between the extent of Vam3-HOPS co-precipitation rates and fusion efficiency (Figs 2C&1C). Whereas the K42A mutant exhibited rates much like the vps1Δ strain, the I649K mutant showed about 35% of the wild type Vam3-HOPS co-precipitation signal, which matched the fusion efficiency of this mutant (Figs 2C&1C) when compared to wild type.

Figure 2. The interaction of Vam3 with HOPS requires Vps1.

(A) Wild type and vps1Δ vacuoles were detergent extracted and immunoprecipitated either with anti Sec17 antibodies or with anti HA antibodies. Immunoprecipitation assay was done as explained in the Methods section. Vam3 binding to Sec17 and Vam3 binding to Vps33-HA were quantified using Odyssey software. Means ± S.D. of three independent experiments are shown. The diagrammatic model displays the different Vam3-containing complexes on wild type and vps1Δ vacuoles

(B) Vps1 is released from HOPS-Vam3 in the presence of ATP. Wild type vacuoles were incubated for 15 min in the absence and presence of ATP. After detergent extraction, Vps33-HA was precipitated and co-precipitating proteins were analyzed by Western blotting.

(C) Vacuoles purified from wild type, K42A and I649K strains were processed as described in Fig.2B. Vps33-HA was precipitated from detergent extracts and co-precipitating proteins were analyzed. The band intensity was quantified from three independent experiments. Means ± S.D. of three independent experiments are shown.

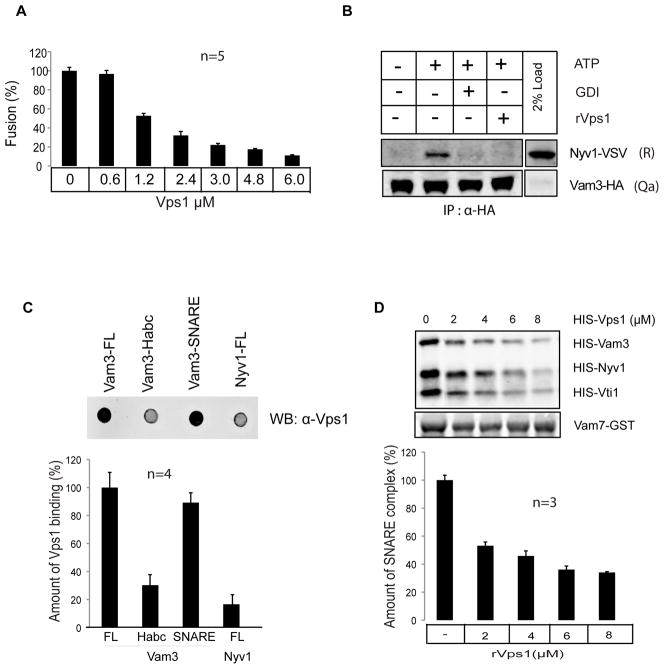

Vps1 specifically binds to the Vam3 SNARE domain

As the release activity of Vps1 from Vam3 is a prerequisite17 for successful vacuolar fusion (Fig. 2B), we asked, whether the addition of excess rVps1 might compensate for the release of endogenous Vps1 from Vam3 and hence might inhibit vacuolar fusion. We confirmed this by adding an increasing amount of rVps1 to fusion reactions (IC 50 ~ 1.8 μM, Fig. 3A, Supplementary Fig. S4) and moreover, addition of rVps1 (5μM) to vacuoles completely suppressed trans-SNARE formation (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3. Vps1 specifically binds to the Qa SNARE Vam3.

(A) Recombinant Vps1 inhibits vacuole fusion. Vacuoles derived from BJ3505 and DKY6805 strains were incubated with increasing concentration of rVps1 in standard fusion reaction as described in the Methods section. Vacuolar fusion was completely inhibited at a concentration of 6μM rVps1.

(B). Recombinant Vps1 inhibits trans-SNARE formation. The trans-SNARE assay was performed as described. Recombinant Vps1 was added to the assay at a concentration of 6μM. GDI, which extracts the small G-protein Ypt7 from the vacuolar membrane, was added as an inhibitor of trans-SNARE formation at a concentration of 5 μM. At the given concentration, rVps1 suppressed trans-SNARE formation much like GDI.

(C) Vps1 binds to SNARE domain of Vam3

1 μg of full-length Vam3, N-terminal domain of Vam3 (1–190), SNARE domain of Vam3 (190–252) and full-length Nyv1 were immobilized on a nitrocellulose membrane and incubated with rVps1 overnight. Detection of bound rVps1 was performed as described in the Methods section. Means ± S.D. of three independent experiments are shown. Only full-length Vam3 and the SNARE domain of Vam3 displayed binding towards rVps1.

(D) Recombinant Vps1 inhibits SNARE complex formation

The indicated recombinant proteins (2μg for all SNAREs) were incubated with increasing concentrations of rVps1 for 1 hr at 4°C and subsequently Vam7-GST was precipitated. Co-precipitating proteins were analyzed using SDS-PAGE and Western blotting. In the presence of 6μM rVps1 SNARE complex formation is suppressed up to 65%. Three independent experiments are shown as means +/−S.D.

Having established that Vps1 controls Vam3 function during trans-SNARE formation (Fig. 1B), we sought for an experimental approach, which would allow us to convincingly demonstrate the specificity of Vps1 binding towards Vam3. Additionally, we were interested in what domain of Vam3 might interact with Vps1. We therefore performed dot blot experiments by immobilizing full- length Vam3, the N-terminal Habc domain, the SNARE domain of Vam3 and full-length Nyv1 onto nitrocellulose membranes. When the immobilized proteins were exposed to rVps1, only full-length Vam3 and the SNARE domain of Vam3 exhibited binding towards Vps1 (Fig. 3C). We determined the Kd of Vam3-Vps1 interactions by biolayer interferometry using an Octet Red 96 instrument (ForteBio Inc.) at 3.63 10−7 M (Supplementary Fig. S5).

To confirm that Vps1 mainly interact with the SNARE domain of Vam3, we investigated SNARE-complex formation of recombinantly expressed SNAREs in the presence of increasing concentrations of rVps1 (Fig. 3D). We speculated that Vps1 might sequester Vam3 from the SNARE complex, leading to decreased numbers of tetrameric SNARE complexes. Indeed, in the presence of rVps1, SNARE complex formation was suppressed up to 65% (Fig. 3D).

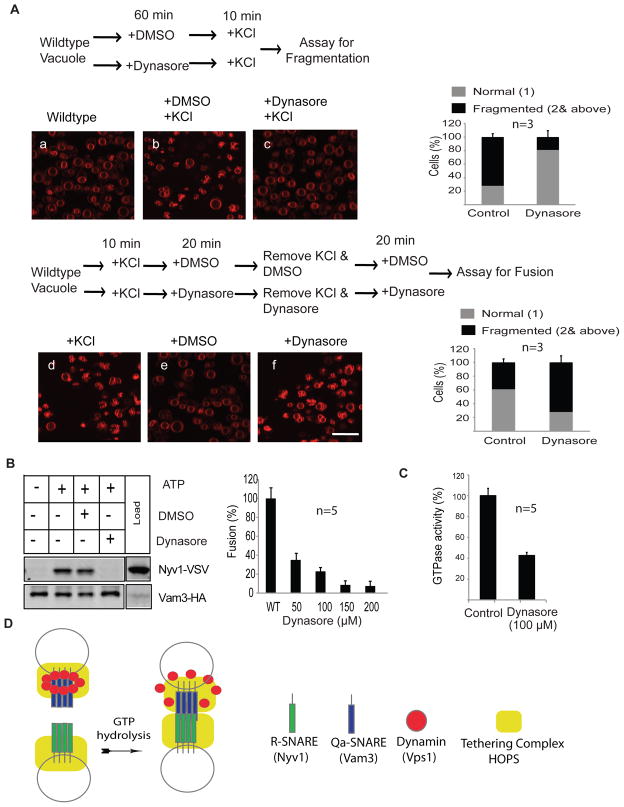

Dynasore inhibits vacuolar fission and fusion in vivo

Yeast vacuoles fragment upon cellular exposure to hypertonic stress17 or at the onset of bud emergence3 as visualized by fluorescence microscopy after staining with the fluorescent dye FM4-6417. Using the hypertonic stress response, we visualize the inhibition of vacuolar fission and fusion in vivo by dynasore. Dynasore is a small molecule, selective non-competitive inhibitor of the protein dynamin28. Logarithmic phase yeast cells were stained with FM4-64. To first explore the effect of dynasore on vacuolar fission, we added either dynasore or the solvent DMSO to the stained cells and subsequently induced fission by a brief high salt exposure (Fig. 4A, upper panel). DMSO did not inhibit vacuolar fragmentation as visualized by the increased number of smaller vacuoles (70% of vacuoles fragmented; Fig. 4A upper panel), whereas dynasore diminished this amount drastically (only 20 % of vacuoles fragmented; Fig. 4A upper panel). To assess the in vivo effect of dynasore on vacuolar fusion, we fragmented the stained vacuoles by brief salt exposure and subsequently added dynasore or DMSO (Fig. 4A lower panel). After release of the vacuoles from the hypertonic media, vacuoles started to refuse, but this was significantly less efficient in the presence of dynasore (only 50% of the DMSO control, Fig. 4A lower panel). Along with our in vivo investigations, we confirmed the inhibitory effect of dynasore on vacuole fusion and trans-SNARE formation in vitro. In the presence of 100μM dynasore we could not observe any trans-SNAREs formation and vacuolar fusion (Fig. 4B). The GTPase activity of rVps1 was inhibited up to 60% by dynasore (Fig. 4C). These data indicate that Vps1 function is critical for controlling vacuolar fission and fusion.

Figure 4. Dynasore inhibits vacuolar fission and fusion in vivo.

(A) Vacuoles of wild type yeast cells were labeled with FM4-64 using the standard procedure as described in the Methods section. In the assay for fragmentation, a) shows the normal vacuole structure of logarithmic phase wild type cells, b) shows salt-induced fragmentation of vacuoles in the presence of solvent DMSO. c) depicts the salt-induced phenotype of vacuoles in the presence of 100μM dynasore. The percentage of cells showing normal or fragmented vacuoles was quantified. 100 cells were counted randomly in each experiment. Three independent experiments are shown as means +/− S.D. In the assay for fusion d) shows the fragmented vacuoles after salt exposure. e) shows the effect of the solvent DMSO on re-fusion of fragmented vacuoles. f) displays the influence of dynasore on re-fusion of fragmented vacuoles. The percentage of cells exhibiting normal or fragmented vacuoles was quantified. 100 cells were counted randomly in each experiment. Three independent experiments are shown as means +/− S.D. Scale bar 5 μm

(B) Dynasore at a concentration of 100 μM inhibits in vitro vacuole fusion and trans SNARE complex formation.

(C) Dynasore inhibits the GTPase activity of recombinant Vps1.

(D) Model explaining the role of Vps1 in trans-SNARE formation.

Vps1 in its polymeric state recruits multiple Qa-SNARE to the tether HOPS. Since Vps1 is bound to the SNARE-domain of Vam3, it has to be released prior to the formation of trans-SNARE. After GTP hydrolysis and concomitant Vps1-release have occurred, multiple trans-SNAREs form at the fusion site. In the absence of Vps1 or in the presence of mutations in Vps1 leading to defects in GTP hydrolysis or polymerization, the number of formed trans-SNAREs does not reach the necessary threshold at the fusion site to promote complete membrane fusion.

Discussion

We have demonstrated that Vps1 is an essential factor in vacuolar fusion. In the absence of Vps1 as well as in the presence of excess rVps1, vacuolar fusion and trans-SNARE establishment are impaired. We interpret the data in a two-step process. First, Vps1 induces a population of Vam3 that associates with HOPS rather than pairing with other SNAREs. While cis-SNARE complexes can be considered as a reservoir for single SNAREs dependent on activation through Sec18/NSF, the HOPS associated fraction of Vam3 is likely essential for organizing SNARE nucleation and trans-SNARE formation27,29. Our data suggest that the population of HOPS associated Vam3 is absent on vps1Δ vacuoles. Since Vps1 predominantly interacts with the SNARE domain of Vam3, it prevents the formation of SNARE complexes in the initial phase of membrane fusion. Consequently, to initiate SNARE nucleation and trans-SNARE interactions, Vps1 has to be released from Vam317. Addition of excess recombinant Vps1 impairs this process and inhibits vacuolar fusion and trans-SNARE formation, emphasizing the importance of the release event.

A second function of Vps1 might be the control of SNARE density with the tethering complex HOPS. Vps1 might actively increases SNARE density at the contact site of two fusing membrane by recruiting several Qa SNAREs to the tethering complex (Fig. 4D). Dynamin with its tendency to polymerize under the appropriate conditions and with its ability to interact with SNARE proteins is likely to be an important regulator of SNARE complex density at the fusion site. This is supported by our data showing that in the GTPase and polymerization deficient Vps1 mutants K42A and I649K the amount of HOPS-associated Vam3 and extent of trans-SNARE formation is significantly lower compared to wild type. Currently, there is ample discussion about the exact number of trans-SNARE complexes needed to promote full content mixing between two fusing membranes, varying between one and four30. Based on our observations made in the I649K Vps1 mutant, we prefer the idea of multiple trans-SNARE complexes per fusion site to promote full membrane bilayer merging.

Methods

Vacuole isolation

Vacuoles were isolated as described previously17. DKY6281 and BJ3505 strains carrying tagged SNAREs were grown in YPD at 30°C at 225 rpm to OD600=2 and harvested (3 min, 5000xg). Vacuoles were isolated through hydrolyzing yeast cell walls using lyticase31, recombinantly expressed in E. coli RSB805 (provided Dr. Randy Schekman, Berkeley) and prepared from a periplasmic supernatant. Harvested cells were resuspended in reduction buffer (30 mM Tris/Cl pH 8.9, 10 mM DTT) and incubated for 5 min at 30°C. After harvesting as described above, cells were resuspended in 15 ml digestion buffer (600 mM sorbitol, 50 mM K-phosphate pH7.5 in YP medium with 0.2% glucose and 0.1 mg/ml lyticase preparation). After 20 min at 30°C, cells were centrifuged (1 min 5800 rpm in JLA25.5 rotor). The spheroplasts were resuspended in 2.5 ml 15% Ficoll-400 in PS buffer (10 mM PIPES/KOH pH 6.8, 200 mM sorbitol) and 200 μl DEAE-Dextran (0.4 mg/ml in PS). After 90 sec of incubation at 30°C, the cells were transferred to SW41 tubes and overlaid with steps of 8%, 4% and 0% Ficoll-400 in PS. Cells were centrifuged for 75 min at 2 °C and 30000 rpm in a SW41 rotor. .

Vacuole fusion

In vitro Vacuole fusion assay was carried out as described previously17. In brief, DKY6281 and BJ3505 vacuoles were adjusted to a protein concentration of 0.5 mg/ml and incubated in a volume of 30 μl PS buffer (10 mM PIPES/KOH pH 6.8, 200 mM sorbitol) with 125 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MnCl2, 1 mM DTT. Inhibitors were added before starting the fusion by addition of the ATP-regenerating system (0.25 mg/ml creatine kinase, 20 mM creatine phosphate, 500 μM ATP, 500 μM MgCl2). After 60 min at 27°C, or on ice, 1 ml of PS buffer was added, vacuoles were centrifuged (2 min, 20000xg, 4°C) and resuspended in 500 μl developing buffer (10 mM MgCl2, 0.2% TX-100, 250 mM TrisHCl pH 8.9, 1 mM p-nitrophenylphosphate). After 5 min at 27°C, the reactions were stopped with 500 μl 1 M Glycin pH 11.5 and the OD was measured at 400 nm.

Trans-SNARE assay

Vacuoles were adjusted to a protein concentration of 0.5 mg/ml. The total volume of one assay was 1 ml containing equal amounts of the two fusion partners in PS buffer with 125 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MnCl2 and 1 mM DTT. Mixed vacuoles were incubated for 5 min at 27°C in the absence of ATP. The fusion reaction was started by adding ATP-regenerating system (0.25 mg/ml creatine kinase, 20 mM creatine phosphate, 500 μM ATP, 500 μM MgCl2). After 30 min at 27°C, the vacuoles were centrifuged for 2 min at 4°C at 20,000 g. The pellet was resuspended in 1.5 ml solubilization buffer (0.5% Triton, 50 mM KCl, 3 mM EDTA, 1 mM DTT in PS). After centrifugation for 4 min at 4°C (20,000 g), the supernatant was incubated with 30 μl Protein G beads (Roche) and 15 μg HA-antibodies (Covance, mouse monoclonal) for 1 hour at 4°C with gentle shaking. The Protein G beads were washed three times with 50 mM KCl, 0.25% Triton, 3 mM DTT and 3 mM EDTA in PS buffer, and incubated for 5 min at 60 °C in 2x reducing SDS sample buffer.

In vivo fragmentation and re-fusion assay

Logarithmic grown BJ3505 cells were stained with FM4-64 (10 μM) for 30 min at 30 °C in YPD and subsequently chased for another 60 min. To visualize dynasore’s effect on fragmentation, stained cells were incubated for 1hr in YPD in the presence of 100μM dynasore. Thereafter, cells were briefly centrifuged and further incubated in YPD supplemented with 200 mM KCl and 100μM dynasore. After 10 min cells were inspected for fragmentation using fluorescence confocal microscopy. To investigate dynasore’s impact on fusion, stained cells were first fragmented by a brief incubation in YPD containing 400 mM KCl (10 min). Dynasore then was added at a concentration of 100μM and cells were incubated for a further 10 min in the high salt YPD. Afterwards, cells were briefly centrifuged and released from the osmotic pressure by addition of normal YPD containing 100μM dynasore. After 20 min, cells were inspected for re-fusion of fragmented vacuoles using fluorescence confocal microscopy.

HOPS precipitation assay

Vacuoles were isolated from BJ3505 wildtype and vps1Δ strains harboring Vps33-HA. 2 mg of vacuoles purified from each strain were incubated with or without ATP in PS buffer containing 100 mM KCl and 500 μM MnCl2 for 15 min at 27°C. Subsequently, the vacuoles were solubilized in buffer containing 100 mM KCl, 500 μM MnCl2, and 0.3% TritonX-100. The samples were centrifuged at 20000g for 10 min and 10 μg of HA antibody (Covance) and Protein G beads were added to the solubilizate. After incubation for 1 hr at 4°C with end-to-end rotation, the samples were centrifuged for 1 min and the beads were washed twice with solubilization buffer. SDS sample buffer was added to the beads and incubated at 90 °C for 2 min. The eluted proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and analyzed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies.

GST-pulldown assay

Nyv1, Vam3 and Vti1 were expressed as full-length proteins devoid of the transmembrane domain from pET289 vectors harboring a poly-His tag on their N-terminus. Vam7 was expressed from a pGEX vector as a N-terminally tagged GST protein. Vps1 was expressed as a full-length protein harboring a poly-His tag on the N-terminus2. A solution containing 2μg each of GST-Vam7, His-Vam3, His-Vti1 and His-Nyv1 was incubated for 1h at 4°C with various amounts of His-Vps1 in PS buffer with 100 mM KCl and 1 mM DTT in the presence of GSH-beads. Thereafter, samples were briefly centrifuged and washed three times using the same buffer. Following, 2x concentrated reducing SDS sample buffer was added to the beads and precipitated proteins were analyzed using SDS-PAGE and Western blotting.

Dot blot assay

Vam3 proteins were expressed as full length, N-terminal domain and SNARE domain from pTYB12 vector with an intein tag on the N-terminus. Vam3 full-length (1–252), the N-terminal domain (1–190) and the SNARE domain (190–252) were cloned into a pTYB12 vector using SpeI and XhoI sites. Proteins were purified as recommended in the IMPACT manual (New England Biolabs). Briefly, BL21(DE3) cells transformed with the plasmid were induced at OD600 of 0.8–1.0 with 0.5mM IPTG at 16°C overnight and bound to chitin beads after cell lysis in 20mM HEPES, 500mM NaCl, pH 8.0. On column cleavage was performed for 16 hours at room temperature in the same buffer with the addition of 50mM DTT. This was dialyzed with 20mM Tris-HCl, 50mM NaCl, pH 7.0. Vps1 was expressed as His-Vps1 was purified as described earlier2. Vam3 samples (1μg) were applied to a nitrocellulose membrane and blocked with 5% skim milk for 1 hr at room temperature. Vps1 at a concentration of 10 μg/ml in 5% skim milk was added to the membrane and incubated over night at 4°C. The membrane was washed with PBS for 5 minutes and incubated with anti Vps1 antibodies for 1 hr at room temperature. Subsequently, the membrane was washed with PBS for 5 minutes and incubated with anti-rabbit secondary antibodies.

GTPase assay

GTP hydrolysis was followed by monitoring release of Pi, which was quantified by a colorimetric method as described32. For basal GTPase assays, Vps1 was diluted to 1 μM in GTPase assay buffer (20 mM HEPES-KOH pH7.5, 150 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT). Vps1 was incubated with dynasore at a concentration of 100 μM for 20–30 min at room temperature with shaking. The inhibitor stock was freshly prepared at a final concentration of 3 mM in DMSO. GTP was added to the samples at a final concentration of 1 mM and incubated at 37°C for 15 min with shaking. The reactions were stopped with 100 mM EDTA pH 8.0. The free orthophosphate was measured using a malachite green phosphate assay kit (Bioassay System)

Microscopy

Images were taken from a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope using an argon laser. Images were exported as TIFF files. Images were cropped from TIFF files and pasted into Adobe Illustrator CS3. The final figure file was saved as adobe illustrator (.ai) format.

Western Blot images

The Western blot images were taken from a LI-COR Odyssey Infrared Imager. The files were exported as TIFF and processed in adobe illustrator CS3. The band intensity was quantified using densitometry software supplied with the Odyssey Infrared Imager.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Monique Reinhardt and Veronique Comte, University of Lausanne, Swetha Mandaloju, Rice University for their technical assistance. This work was supported by NIH grant GM087333 to Christopher Peters; SNF 3100A0-128661/1 to Andreas Mayer; NIH grant GM088803 and Welch Foundation (Q-581) to Florante A. Quiocho.

Footnotes

Author Contributions

K.A and C.P designed research; K.A., A.K and C.P performed research; S.N., S.S., K.S., K.A., M.Z., A.S., A.M., M.E and F.Q contributed reagents; K.A and C.P wrote the manuscript.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Luzio JP, Pryor PR, Bright NA. Lysosomes: fusion and function. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:622–632. doi: 10.1038/nrm2217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Okamoto K, Shaw JM. Mitochondrial morphology and dynamics in yeast and multicellular eukaryotes. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:503–536. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.38.072902.093019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weisman LS. Organelles on the move: insights from yeast vacuole inheritance. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:243–252. doi: 10.1038/nrm1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pelham HR. SNAREs and the specificity of membrane fusion. Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:99–101. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)01929-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weber T, Zemelman BV, McNew JA, Westermann B, Gmachl M, Parlati F, Sollner TH, Rothman JE. SNAREpins: minimal machinery for membrane fusion. Cell. 1998;92:759–772. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81404-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ungermann C, Sato K, Wickner W. Defining the functions of trans-SNARE pairs. Nature. 1998;396:543–548. doi: 10.1038/25069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fukuda R, McNew JA, Weber T, Parlati F, Engel T, Nickel W, Rothman JE, Sollner TH. Functional architecture of an intracellular membrane t-SNARE. Nature. 2000;407:198–202. doi: 10.1038/35025084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pieren M, Schmidt A, Mayer A. The SM protein Vps33 and the t-SNARE H(abc) domain promote fusion pore opening. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2010;17:710–717. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brocker C, Engelbrecht-Vandre S, Ungermann C. Multisubunit tethering complexes and their role in membrane fusion. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R943–952. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Galas MC, Chasserot-Golaz S, Dirrig-Grosch S, Bader MF. Presence of dynamin--syntaxin complexes associated with secretory granules in adrenal chromaffin cells. J Neurochem. 2000;75:1511–1519. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0751511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malsam J, Kreye S, Sollner TH. Membrane fusion: SNAREs and regulation. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2814–2832. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8352-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pawlowski N. Dynamin self-assembly and the vesicle scission mechanism: how dynamin oligomers cleave the membrane neck of clathrin-coated pits during endocytosis. Bioessays. 2010;32:1033–1039. doi: 10.1002/bies.201000086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schmid SL, Frolov VA. Dynamin: Functional Design of a Membrane Fission Catalyst. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2011;27:79–105. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinshaw JE. Dynamin and its role in membrane fission. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:483–519. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramachandran R. Vesicle scission: dynamin. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011;22:10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2010.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anantharam A, Axelrod D, Holz RW. Real-time imaging of plasma membrane deformation reveals pre-fusion membrane curvature changes and a role for dynamin in the regulation of fusion pore expansion. J Neurochem. 2012;122:661–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2012.07816.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peters C, Baars TL, Buhler S, Mayer A. Mutual control of membrane fission and fusion proteins. Cell. 2004;119:667–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ungermann C, von Mollard GF, Jensen ON, Margolis N, Stevens TH, Wickner W. Three v-SNAREs and two t-SNAREs, present in a pentameric cis-SNARE complex on isolated vacuoles, are essential for homotypic fusion. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:1435–1442. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.7.1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smaczynska-de R, II, Allwood EG, Aghamohammadzadeh S, Hettema EH, Goldberg MW, Ayscough KR. A role for the dynamin-like protein Vps1 during endocytosis in yeast. J Cell Sci. 2010;123:3496–3506. doi: 10.1242/jcs.070508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Smaczynska-de R, II, Allwood EG, Mishra R, Booth WI, Aghamohammadzadeh S, Goldberg MW, Ayscough KR. Yeast dynamin Vps1 and amphiphysin Rvs167 function together during endocytosis. Traffic. 2012;13:317–328. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2011.01311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chappie JS, Acharya S, Leonard M, Schmid SL, Dyda F. G domain dimerization controls dynamin’s assembly-stimulated GTPase activity. Nature. 2010;27:435–40. doi: 10.1038/nature09032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mishra R, Smaczynska-de R, II, Goldberg MW, Ayscough KR. Expression of Vps1 I649K a self-assembly defective yeast dynamin, leads to formation of extended endocytic invaginations. Commun Integr Biol. 2011;4:115–117. doi: 10.4161/cib.4.1.14206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song BD, Yarar D, Schmid SL. An assembly-incompetent mutant establishes a requirement for dynamin self-assembly in clathrin-mediated endocytosis in vivo. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:2243–2252. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-01-0015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins KM, Thorngren NL, Fratti RA, Wickner WT. Sec17p and HOPS, in distinct SNARE complexes, mediate SNARE complex disruption or assembly for fusion. EMBO J. 2005;24:1775–1786. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Seals DF, Eitzen G, Margolis N, Wickner WT, Price A. A Ypt/Rab effector complex containing the Sec1 homolog Vps33p is required for homotypic vacuole fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:9402–9407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alpadi K, Kulkarni A, Comte V, Reinhardt M, Schmidt A, Namjoshi S, Mayer A, Peters C. Sequential analysis of trans-SNARE formation in intracellular membrane fusion. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001243. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kulkarni A, Alpadi K, Namjoshi S, Peters C. A tethering complex dimer catalyzes trans-SNARE complex formation in intracellular membrane fusion. Bioarchitecture. 2012;1:59–69. doi: 10.4161/bioa.20359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Macia E, Ehrlich M, Massol R, Boucrot E, Brunner C, Kirchhausen T. Dynasore, a cell-permeable inhibitor of dynamin. Dev Cell. 2006;10:839–850. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Collins KM, Wickner WT. Trans-SNARE complex assembly and yeast vacuole membrane fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:8755–8760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702290104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohrmann R, Sørensen JB. SNARE Requirements En Route to Exocytosis: from Many to Few. J Mol Neurosci. 2012;48:387–94. doi: 10.1007/s12031-012-9744-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Scott JH, Schekman R. Lyticase: endoglucanase and protease activities that act together in yeast cell lysis. J Bacteriol. 1980;142:414–423. doi: 10.1128/jb.142.2.414-423.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leonard M, Song BD, Ramachandran R, Schmid SL. Robust colorimetric assays for dynamin’s basal and stimulated GTPase activities. Methods Enzymol. 2005;404:490–503. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)04043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.