SUMMARY

We recently reported that two homologous yeast proteins, Rai1 and Dxo1, function in a quality control mechanism to clear cells of incompletely 5′-end capped mRNAs. Here we report that their mammalian homolog, Dom3Z, possesses pyrophosphohydrolase, decapping and 5′-3′ exoribonuclease activities, and will be referred to as DXO. Surprisingly, we find that DXO preferentially degrades defectively capped pre-mRNAs in cells. Further studies show that incompletely capped pre-mRNAs are inefficiently spliced at all introns, in contrast to current understanding, and poorly cleaved for polyadenylation. Crystal structures of DXO in complex with substrate mimic and products at up to 1.5Å resolution provide elegant insights into the catalytic mechanism and molecular basis for its three apparently distinct activities. Our data reveal a pre-mRNA 5′-end capping quality control mechanism in mammalian cells, with DXO as the central player for this mechanism, and demonstrate an unexpected intimate link between proper 5′-end capping and subsequent pre-mRNA processing.

Keywords: pre-mRNA quality control, pre-mRNA decapping, 5′-3′ exoribonuclease

INTRODUCTION

The 5′-end 7-methylguanosine (m7G) cap of eukaryotic mRNAs is the first modification of nascent transcripts (pre-mRNAs) shortly after the initiation of transcription and plays critical roles in mRNA biogenesis and stability (Furuichi and Shatkin, 2000; Ghosh and Lima, 2010; Liu and Kiledjian, 2006; Merrick, 2004; Meyer et al., 2004; Shatkin, 1976). The N7-methyl group on the cap is essential for recognition by the cap binding proteins, CBP and eIF4E (Fischer, 2009; Gingras et al., 1999; Goodfellow and Roberts, 2008), and for efficient splicing, polyadenylation, mRNA export, and translation. Removal of the 5′-end cap is catalyzed by Dcp2 (Dunckley and Parker, 1999; Lykke-Andersen, 2002; Wang et al., 2002) and Nudt16 (Li et al., 2011; Song et al., 2010) decapping enzymes, releasing m7GDP and 5′ monophosphate RNA. Decapping is associated with mRNA decay, turnover and quality control, as the 5′ monophosphorylated RNA is rapidly degraded by the cytoplasmic, processive 5′-3′ exoribonuclease Xrn1 (Decker and Parker, 1993; Hsu and Stevens, 1993). In contrast, the primary transcripts, with 5′-end triphosphate group, and other capping intermediates cannot serve as substrates for the classical decapping enzymes and would be protected from degradation by the 5′-3′ exoribonucleases. Therefore it was generally believed that the capping process always proceeds to completion.

Our recent studies on the yeast proteins, Rai1 and its homolog Dxo1 (Ydr370C), have demonstrated new catalytic activities that can remove incomplete caps from mRNAs indicating that capping may be less efficient than initially thought. Specifically, Rai1 possesses RNA 5′ pyrophosphohydrolase (PPH) activity, hydrolyzing the 5′-end triphosphate to release pyrophosphate (Xiang et al., 2009). Rai1 also has a distinct ‘decapping’ activity, hydrolyzing the entire cap structure from an unmethylated 5′-end capped RNA to release GpppN (Jiao et al., 2010). In comparison, Dxo1 lacks PPH activity but possesses ‘decapping’ activity on both methylated and unmethylated capped RNAs (Chang et al., 2012).

The identification of such catalytic activities suggests the hypothesis that mRNAs with incomplete 5′-end caps are produced in yeast and Rai1 and Dxo1 function as quality control mechanisms to mediate the clearance of such defective mRNAs. In fact, the catalytic activities of Rai1 and Dxo1 ultimately generate RNAs with 5′-end monophosphate, which can be readily degraded by 5′-3′ exoribonucleases. Dxo1 also possesses a distributive 5′-3′ exoribonuclease activity, enabling this enzyme to single-handedly decap and degrade incompletely capped mRNAs (Chang et al., 2012).

Studies in yeast cells have confirmed the existence of this mRNA 5′-end capping quality control. Unmethylated 5′-end capped mRNAs were more stable in cells disrupted for the Rai1 gene, and exposure of these cells to nutrient stress generated mRNAs with incompletely capped 5′-ends (Jiao et al., 2010). More importantly, yeast cells where both Rai1 and Dxo1 were disrupted produced mRNAs with incomplete caps even under normal growth conditions (Chang et al., 2012). It appears that yeast possess two partially redundant proteins that can detect and degrade incompletely capped mRNAs, which are generated under both stress and nonstress conditions.

Rai1 and Dxo1 have a weak sequence homolog in mammals, known as Dom3Z (Xue et al., 2000). It has a similar three-dimensional structure (Xiang et al., 2009), but its biochemical activities and biological functions have not been characterized. Here we report that Dom3Z possesses PPH, decapping, and exoribonuclease activities. Crystal structures of Dom3Z in complex with substrate mimic and products at up to 1.5Å resolution provide elegant insights into the catalytic mechanism and the molecular basis for the three apparently distinct activities of these enzymes. Importantly, Dom3Z preferentially functions on incompletely capped pre-mRNAs in mammalian cells, in sharp contrast to yeast cells where Rai1 and Dxo1 function on incompletely capped mRNAs. Our studies also reveal unexpected insights into the connection between 5′-end capping and splicing, showing that defective capping inhibits splicing at internal introns while current data suggest the cap affects splicing of only the first intron.

RESULTS

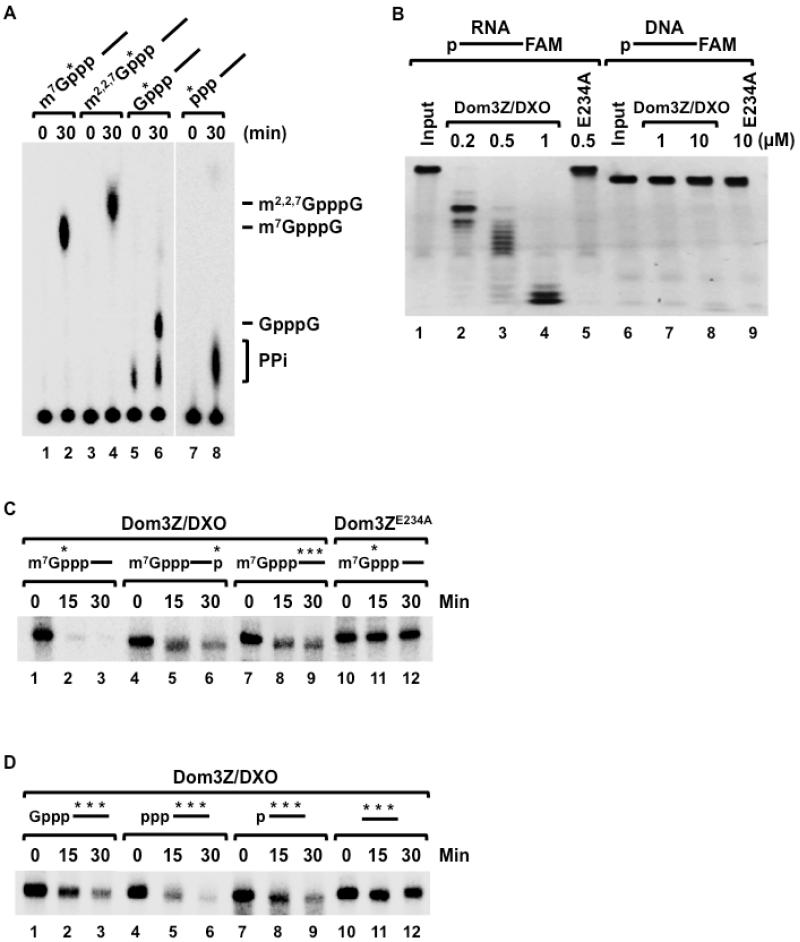

Dom3Z/DXO has decapping, PPH and exonuclease activities

Mammalian Dom3Z is a weak sequence homolog of yeast Rai1 and Dxo1 but has strong structural similarity to them (Chang et al., 2012; Xiang et al., 2009). We therefore tested which biochemical activities Dom3Z shares with Rai1 and Dxo1. Mouse Dom3Z (Figure S1) readily decapped unmethylated capped RNA (GpppG-RNA) to release the GpppG cap structure (Figure 1A, lanes 5 and 6), and it possessed PPH activity as well, releasing PPi from pppRNA (lanes 7 and 8). Interestingly, Dom3Z also showed strong decapping activity toward both monomethylated (lanes 1-2) and trimethylated capped RNAs (lanes 3-4). The observed activities are a function of Dom3Z as two different mutations within the putative active site (E234A and D236A) abrogated the decapping activity (Figure S2). These data demonstrate that Dom3Z possesses decapping and PPH activities on incompletely capped mRNAs and also functions on m7G- and m2,2,7G-capped mRNAs.

Figure 1. Dom3Z/DXO possesses pyrophosphohydrolase, decapping and 5′-3′ exoribonuclease activities.

(A) Decapping activity of Dom3Z/DXO toward RNAs with various 5′ ends depicted schematically at the top is shown where the RNA is represented by a line. The asterisk denotes the 32P position. Reactions were carried out with 25nM pcP RNA and 25nM recombinant His-tagged Dom3Z protein at 37°C for the indicated times. Decapping products were resolved on PEI-TLC developed in 0.45 M (NH4)2SO4 (lanes 1-6) or 0.75M KH2PO4 (pH 3.4; lanes 7-8)). Migrations of cap analoge markers are indicated.

(B) Wild type and mutant Dom3Z/DXO proteins were incubated with 5′-end monophosphate 30-nt RNA or DNA substrates labeled at the 3′-end with the FAM (6-carboxyfluorescein) fluorophore. Remaining RNA or DNA fragments were resolved by 5% denaturing PAGE and visualized under UV light confirming the distributive, 5′-3′ exoribonuclease activity. The RNA or DNA is denoted by a line, the 5′ monophosphate is represented by the p at the beginning of the line. The catalytically inactive E234A mutant is shown.

(C) In vitro decay reactions were carried out with 100nM recombinant His-tagged Dom3Z/DXO for the indicated times with methyl-capped RNAs (25 nM) represented schematically with the 32P labeling indicated by the asterisk. RNAs remaining were resolved by 5% denaturing PAGE. Catalytically inactive Dom3Z/DXO mutant (Dom3ZE234A) was used as a negative control.

(D) The 5′ end substrate specificity of Dom3Z/DXO was tested as in (A) above with RNAs containing distinct 5′ ends as denoted schematically. RNAs with a 5′ hydroxyl were not degraded by Dom3Z/DXO.

We next tested whether Dom3Z also possesses 5′-3′ exoribonuclease activity, based on our observations with Dxo1 (Chang et al., 2012). A 30 nucleotide RNA substrate with a 5′-end monophosphate and a 3′-end FAM (6-carboxyfluorescein) fluorophore (Sinturel et al., 2009a) was degraded by wild-type Dom3Z from the 5′-end with clear intermediates detected (Figure 1B, lanes 2-4)), but not by a catalytically inactive Dom3Z (lane 5), suggesting that Dom3Z has distributive, 5′-3′ exoribonuclease activity. The lack of detectable activity on a ssDNA substrate (lanes 6-9) demonstrates the Dom3Z exonuclease activity is RNA-specific.

To determine whether capped RNAs can be degraded by Dom3Z, methyl-capped RNAs labeled at the 5′-end, 3′-end or uniform labeled were incubated with Dom3Z and their decay followed over time in vitro. All the RNAs were efficiently degraded by Dom3Z (Figure 1C). Dom3Z activity was also tested on RNAs with different 5′-end modifications, including unmethylated cap, triphosphate group, monophosphate group, and hydroxyl group. All the substrates were degraded except the one with a 5′-end hydroxyl (Figure 1D), demonstrating that the Dom3Z 5′-3′ exonuclease activity requires a 5′-end monophosphate on the RNA substrate, analogous to Xrn1 and Xrn2.

Overall, our data demonstrate that Dom3Z has three catalytic activities: decapping activity that removes the entire methylated or unmethylated cap structure, PPH activity, and distributive 5′-3′ exonuclease activity. We will refer to Dom3Z as Decapping Exoribonuclease, DXO, from here on in.

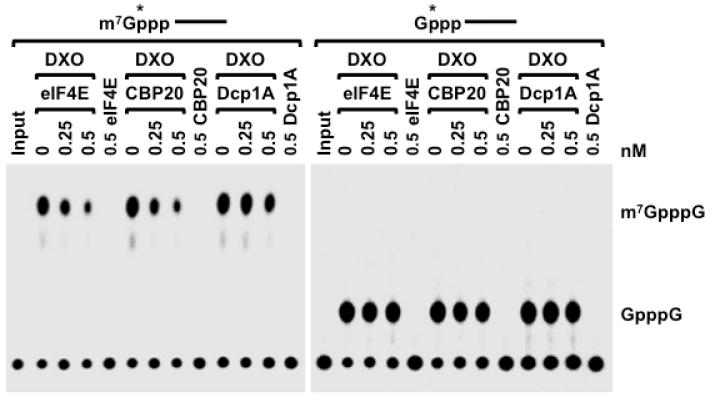

While DXO showed decapping activity toward methylated capped RNAs in vitro, we suspected that such an activity would be thwarted in cells by cap binding proteins, which preferentially bind the methylated cap (Calero et al., 2002; Marcotrigiano et al., 1997; Matsuo et al., 1997; Mazza et al., 2002) and thereby can protect the RNA against decapping by DXO. Consistent with this hypothesis, both the nuclear and the cytoplasmic cap binding proteins, CBP20 and eIF4E (Figure S1), efficiently inhibited DXO decapping of methylated capped RNA in vitro, but had no protective effect on unmethylated capped RNA (Figure 2). These data indicate that DXO should preferentially target defectively capped RNAs in cells.

Figure 2. Cap binding proteins compete for DXO decapping on methyl-capped RNA in vitro.

Decapping activity of 20nM DXO on 32P 5′-end labeled methyl-capped or unmethyl-capped RNA in the presence of the indicated eIF4E, CBP20 or Dcp1A proteins are shown. Decapping assay was carried out as described in legend to Fig 1. Both eIF4E and CBP20 can compete DXO decapping on methyl-capped RNA but not unmethyl-capped RNA.

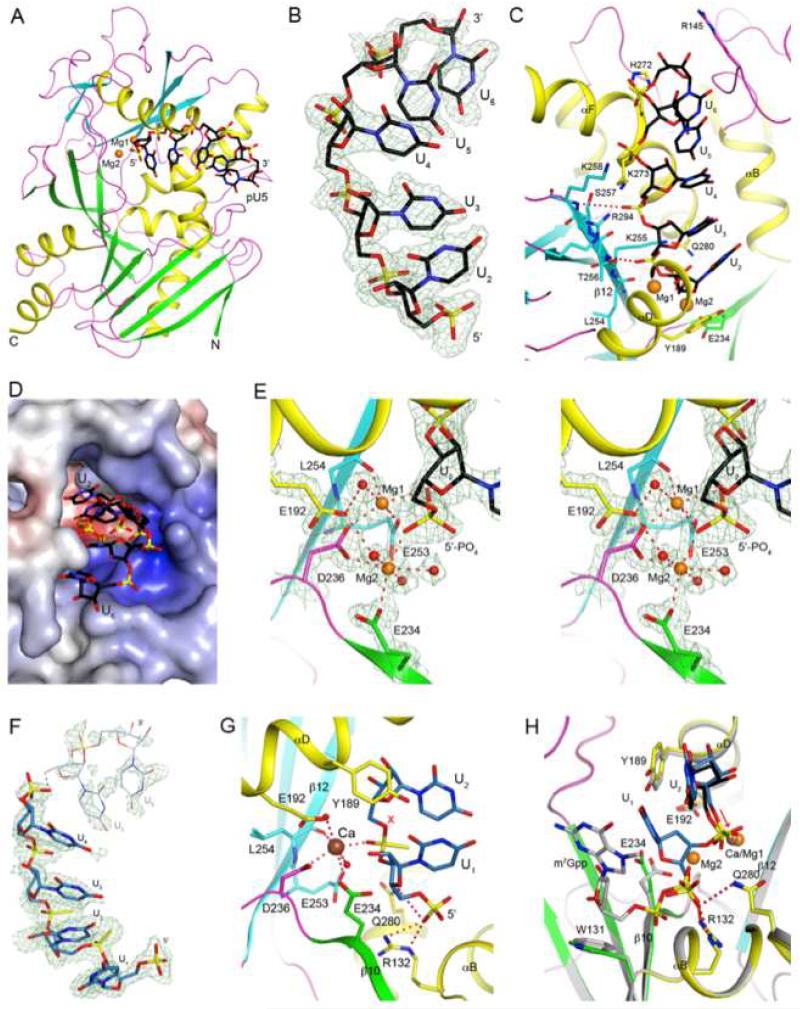

Crystal structure of DXO in complex with a RNA oligonucleotide product

DXO, Rai1 and Dxo1 have three apparently distinct catalytic activities: RNA 5′-end pyrophosphohydrolase (PPH), decapping, and 5′-3′ exoribonuclease, although a common product is generated by these activities, the RNA body with a 5′-end monophosphate. While our biochemical data suggest that the activities are mediated by a common active site, the molecular mechanism for them is not clear. These proteins share four conserved sequence motifs in the putative active site region (Chang et al, 2012), corresponding to residues Arg132 (motif I), Glu192 (motif II, GΦxΦE, where Φ is an aromatic or hydrophobic residue, x any residue), Glu234 and Asp236 (motif III, EhD, where h is a hydrophobic residue), Glu253 and Lys255 (motif IV, EhK) in mouse DXO (Figure S3). Residues Glu192, Asp236, and Glu253 are known to coordinate a Mg2+ ion in the active site (through a water for Glu192) (Xiang et al., 2009). The functional roles of the other conserved residues in substrate binding and/or catalysis are not known.

To understand the catalytic mechanism(s) of these enzymes, we determined the crystal structure of wild-type mouse DXO in complex with magnesium ion and a RNA penta-nucleotide with a 5′-end phosphate, pU5, at 1.8 Å resolution (Figure 3A). The complex was prepared by soaking crystals of DXO free enzyme with a solution containing 10 mM pU5 and 10 mM MgCl2 for 90 min. The structure has excellent agreement with the X-ray diffraction data and the expected bond lengths, bond angles and other geometric parameters (Table 1).

Figure 3. Crystal structure of wild-type murine DXO in complex with pU5 and two Mg2+ ions.

(A). Schematic drawing of the structure of DXO (in green and cyan for the large and small β-sheets, respectively, yellow for the helices, and magenta for the loops) in complex with pU5 RNA oligonucleotide (in black for carbon atoms) and Mg2+ ions (orange).

(B). Simulated-annealing omit Fo-Fc electron density at 1.8 Å resolution for pU5, contoured at 2.5σ.

(C). Interactions between the pU5 RNA with the DXO active site.

(D). Molecular surface of the active site region of DXO. The pU5 RNA is shown as sticks.

(E). The coordination spheres of the two Mg2+ ions, and detailed interactions between the 5′-end phosphate group of pU5 and the two Mg2+ ions.

(F). Simulated-annealing omit Fo-Fc electron density at 1.7 Å resolution for pU(S)6, contoured at 2.2σ. Very weak electron density is observed for the last two nucleotides, and they are not included in the atomic model.

(G). Interactions between the first two nucleotides of pU(S)6 with DXO. The oligo is shown in light blue, and the Ca2+ ion is shown as a sphere in brown. The red X indicates the expected position of a water/hydroxide ion to initiate hydrolysis based on the observed conformation of the phosphorothioate group.

(H). Overlay of the structures of the pU(S)6 and pU5 complexes in the active site region of DXO. The pU(S)6 oligo is shown in light blue, pU5 in black. DXO in the pU(S)6 complex is shown in color, and that in the pU5 complex in gray. The red arrow indicates the O5-P bond, and the two phosphate groups differ by ~60° rotation around this bond. The m7Gpp portion of the methylated cap (see Fig. 4 for more information) is also shown (gray). All the structure figures were produced with PyMOL (www.pymol.org).

Table 1. Summary of crystallographic information.

| Structure | pU5-Mg2+ complex | pU(S)6-Ca2+ complex | m7GpppG complex |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution range (Å) 1 | 30-1.8 (1.86–1.8) | 30-1.7 (1.76-1.7) | 40-1.5 (1.55-1.5) |

| Number of observations | 123,120 | 156,109 | 274,259 |

| Redundancy | 3.2 (2.7) | 3.4 (2.9) | 4.1 (3.6) |

| Rmerge (%) | 7.6 (30.2) | 6.5 (35.7) | 6.7 (43.8) |

| I/σI | 14.5 (2.7) | 17.1 (2.6) | 19.7 (2.9) |

| Number of reflections | 37,023 | 43,982 | 64,292 |

| Completeness (%) | 93 (76) | 92 (72) | 96 (88) |

| R factor (%) | 18.3 (26.8) | 18.3 (29.6) | 17.2 (23.6) |

| Free R factor (%) | 21.5 (31.1) | 21.3 (29.3) | 20.0 (26.3) |

| rms deviation in bond lengths (Å) | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.011 |

| rms deviation in bond angles (°) | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.6 |

| PDB accession code2 |

The numbers in parentheses are for the highest resolution shell.

Clear electron density was observed for the first three nucleotides of pU5 (Figure 3B). The remaining 2 nucleotides have weaker electron density, and there is a break in the electron density between the third and fourth nucleotide. The structural analysis suggests that the pU5 RNA is bound in the active site of DXO as a product, with the 5′-end phosphate being the scissile phosphate of the substrate (see below). Hence the nucleotides are numbered from 2 to 6 (Figure 3C), with the expectation that nucleotide 1 would be the leaving group in the substrate. Although pU5 can serve as a substrate for the 5′-3′ exonuclease activity of DXO, its binding mode in the current crystal is consistent with that of a product.

The first nucleotide of the oligo, U2, has extensive interactions with DXO, especially the 5′-end phosphate group (see below). The rest of the oligo runs along strand β12, and there are two hydrogen bonds between the main-chain amides of this β-strand (residues 256 and 258) and the backbone phosphate groups of the oligo (U3 and U4) (Figure 3C). In addition, three positively charged side chains, Lys258, Lys273, and Arg294, interact with the phosphate groups of the RNA, with Lys273 and Arg294 being conserved among the DXO/Rai1/Dxo1 homologs (Figure S3). On the other hand, the bases of the nucleotides are not recognized specifically by DXO, and they have weaker electron density as well (Figure 3B), consistent with our biochemical data that DXO does not have sequence specificity. The active site pocket is only large enough to accommodate a single-stranded substrate (Figure 3D), and we observed earlier that Dxo1 stalls at double-stranded portions of the substrate (Chang et al., 2012).

Unexpectedly, the structure reveals that a second metal ion is bound in the active site in the presence of the pU5 oligo (Figure 3E). Both metal ions are located in an octahedral coordination sphere. The first metal ion (Mg1) is in the same position as observed earlier in the free enzyme (Xiang et al., 2009), while binding of the second metal ion (Mg2) is only possible in the presence of the RNA, as one of the terminal oxygen atoms on the 5′-end phosphate of the RNA is a bridging ligand to both metal ions. The side chain of Asp236 (motif III) makes a bidentate coordination of both metal ions, and the side chain of Glu192 (motif II) makes a hydrogen bond to one water ligand on each of the metal ions. Mg1 is also coordinated by the side chain of Glu253 (motif IV), the main-chain carbonyl of residue 254, as well as another terminal oxygen atom of the 5′-end phosphate group of the RNA. Therefore, this phosphate group replaces two of the water ligands of Mg1 in the free enzyme (Xiang et al., 2009). For Mg2, the side chain of Glu234 (the second acidic residue of motif III) and two additional water molecules complete the octahedral coordination.

The ribose of U2 is packed against the side chain of Tyr189 (motif II) (Figure 3C and S4). This residue is most often a Phe or Tyr among these enzymes. In addition, the 2′ hydroxyl group of the ribose is hydrogen-bonded to the main-chain carbonyl of residue 185 (Figure S4). This residue is in the middle of helix αD, but a small kink in the helix in this region makes the carbonyl oxygen available for hydrogen-bonding to the ribose.

Crystal structure of DXO in complex with a RNA oligonucleotide substrate mimic

To observe the binding mode of the 5′-end nucleotide of a substrate RNA in the DXO active site, we used a hexa-nucleotide with a 5′-end monophosphate and with the phosphodiester group between nucleotides 1-2 and 2-3 replaced with a phosphorothioate group to inhibit the hydrolysis of this RNA. Therefore this pU(S)6 oligonucleotide has the sequence pU1-SU2-SU3-U4-U5-U6. In addition, we replaced the Mg2+ ion with Ca2+ ion during crystallization, to further block hydrolysis of the RNA. Our enzymatic assays showed that DXO is essentially inactive with Ca2+ as the divalent metal ion (data not shown).

We have determined the crystal structure of mouse DXO in complex with Ca2+ and the pU(S)6 oligonucleotide at 1.7 Å resolution (Table 1, Figure S5,). Clear electron density was observed for the first four nucleotides of the RNA (Figure 3F). Very weak electron density was observed for the bases of the last two nucleotides, and they were not included in the atomic model.

The RNA is bound in the active site with the phosphorothioate group between nucleotides 1 and 2 located next to the catalytic site (Fig. 3G). The 5′-end phosphate group of the oligo interacts with the side chain of Arg132 (motif I) and it is also close to the side chain of Gln280 (Figure 3G). The base of the first nucleotide maintains π-stacking with that of the second nucleotide. The binding modes of nucleotides 2-4 are highly similar to their equivalents in the pU5 complex (Figure S5).

Only one Ca2+ ion is observed in the complex, at the same position as Mg1 in the pU5 complex (Figure 3G). The terminal oxygen atom of the phosphorothioate linkage between nucleotides 1 and 2 is a ligand to the metal ion. The conformation of this phosphorothioate group is different from that of the 5′-end phosphate group of the pU5 complex (Figure 3H), equivalent to ~60° rotation around the O5-P bond. The sulfur atom in pU(S)6 cannot have strong interaction with the metal ion and may have (at least partly) driven this conformational change. In fact, this sulfur atom is positioned furthest away from the metal ion (Figure 3G). Besides the phosphorothioate group, a conformational change in the Tyr189 side chain is also observed in the pUS(6) complex, due to the presence of the U1 base (Figure 3H). In addition, the side chain of Glu234 assumes a different conformation due to the absence of the second metal ion.

While the first nucleotide of the pU(S)6 RNA may mimic the 5′-end of the RNA substrate for exonuclease activity, the phosphorothioate group between nucleotides 1 and 2 is not in the correct conformation for catalysis. The water molecule (or hydroxide ion) that would need to attack the phosphorus atom would not be in the correct position to be activated by any functional group in the active site (Figure 3G). Therefore, conformational changes are expected in this phosphate group, and possibly those atoms covalently attached to it, to make this a true substrate. The conformation of the 5′-end phosphate in the pU5 oligo might be a better mimic for the scissile phosphate group.

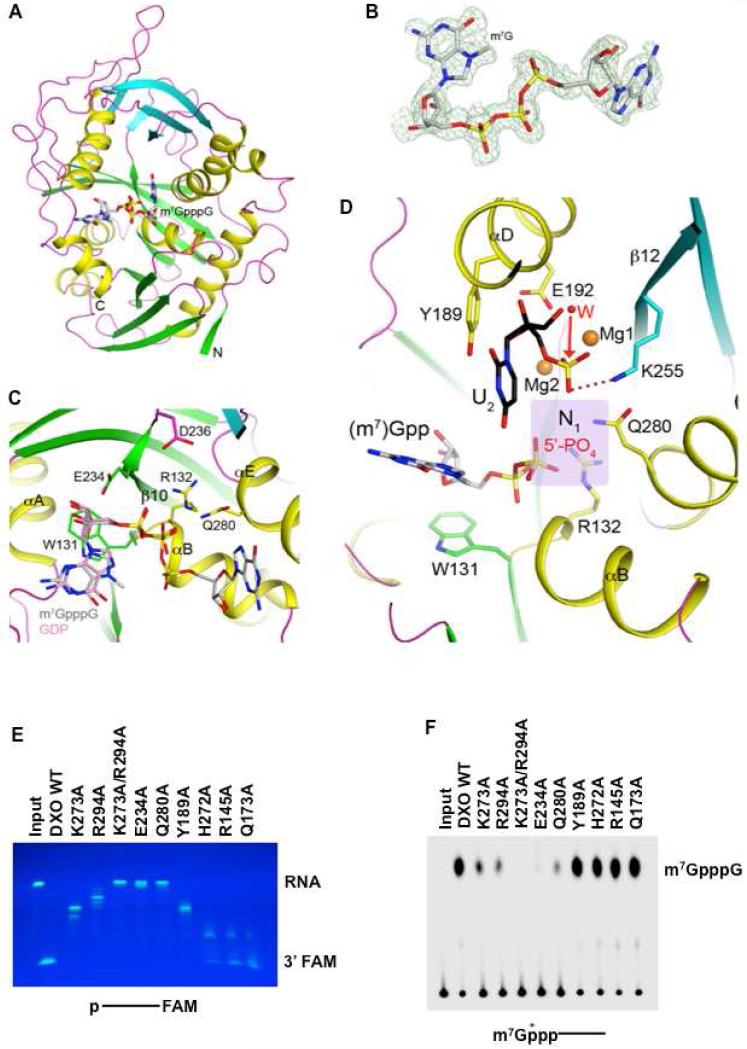

Crystal structure of DXO in complex with the m7GpppG cap

To understand how the RNA cap is recognized by DXO, we determined the structure of wild-type murine DXO in complex with m7GpppG at 1.5 Å resolution (Table 1, Figure 4A). There are only a few conformational differences in the active site region between this structure and that in complex with pU5, the most important of which is the side chain of Glu234. It is somewhat disordered in the cap complex as well as the free enzyme, and it becomes well ordered as a ligand to Mg2 in the pU5 complex.

Figure 4. Crystal structure of wild-type murine DXO in complex with the m7GpppG cap.

(A) Schematic drawing of the structure of DXO (in green and cyan for the two β-sheets, yellow for the helices, and magenta for the loops) in complex with the m7GpppG cap (in gray for carbon atoms).

(B) Simulated-annealing omit Fo-Fc electron density at 1.5 Å resolution for m7GpppG, contoured at 3σ.

(C) Interactions between the m7GpppG cap with the DXO active site.

(D) Overlay of the structures of DXO in complex with pU5 (in black) and two Mg2+ ions (orange) and m7Gpp (gray).

(E) The indicated DXO wild type and mutant proteins were incubated with 5′-end monophosphate 30-nt RNA substrate labeled at the 3′-end with the fluorophore FAM. Remaining RNA fragments were resolved by 15% denaturing PAGE and visualized under UV light confirming the distributive, 5′-3′ exonuclease activity.

(F) The indicated DXO wild type and mutant proteins were tested for decapping activity. Methyl-capped RNA labeled with 32P at the 5′-end was used in decapping reactions. Reaction conditions and labeling are as described in the legend to Figure 1.

The m7Gpp group of the cap has good electron density (Figure 4B) and is bound in the active site region at a position similar to that of GDP observed earlier (Xiang et al., 2009) (Figure 4C). The 7-methyl group of guanine is not recognized specifically by the enzyme, consistent with our biochemical data showing that DXO is nonselective with regard to the methylation status of the cap (Figure 1A). In fact, residues that contact this guanine base are not well conserved among the enzymes (Figure S3). The ribose is packed against the side chain of Trp131, the residue just preceding motif I, which is conserved as an aromatic residue in most DXO and Rai1 homologs (Figure S3). One of the terminal oxygen atoms on the α-phosphate has ionic interactions with the side chain of Arg132 (motif I) and is hydrogen-bonded to the main-chain amide of Glu234, while the other terminal oxygen atom is hydrogen-bonded to the main-chain amide of Arg132, at the N-terminal end of helix αB. Therefore, the α-phosphate also has favorable interactions with the dipole of this helix. The β-phosphate is located near the side chains of Arg132 and Gln280, and in fact this β-phosphate overlaps with the 5′-end phosphate of the pU(S)6 nucleotide (Figure 3H).

The second guanosine group of the cap is packed against the wall of the active site pocket, and there is no room to attach another nucleotide to the 3′ hydroxyl group of its ribose (Figure 4C). Therefore, this guanosine group is not in a productive binding mode in this complex, and needs to assume a different conformation in the complex with the (m7)GpppG-RNA substrate.

Mutagenesis studies support the structural observations

To assess the importance of residues in the active site region of DXO, the following structure-based mutants (Figure S1) were created, K273A, R294A and K273A/R294A (interacting with the backbone phosphate, Figure 3C), Q280A (interacting with the 5′-end phosphate of the substrate, Figure 3G), Y189A (interacting with the ribose of U2, Figure 3C), H272A and R145A (interacting with U6 at the opening of the active site pocket, Figure 3C). The Q173A mutant was created as a control, which is located far away from the active site.

The K273A, R294A, and Y189A substitutions led to reduced exonuclease activity, while the K273A/R294A, E234A and Q280A mutants ablated exonuclease activity (Figure 4E). The H272A and R145A mutants at the opening of the active site retain a majority of the wild type exonuclease activity. The effects of these mutations on the decapping activity mostly follow those for the exonuclease activity, with one exception being that the Y189A mutant had essentially normal decapping activity (Figure 4F). Overall, our structural observations provide the molecular framework for the decapping, PPH and exonuclease activities of DXO.

DXO preferentially functions on defectively capped pre-mRNAs in vivo

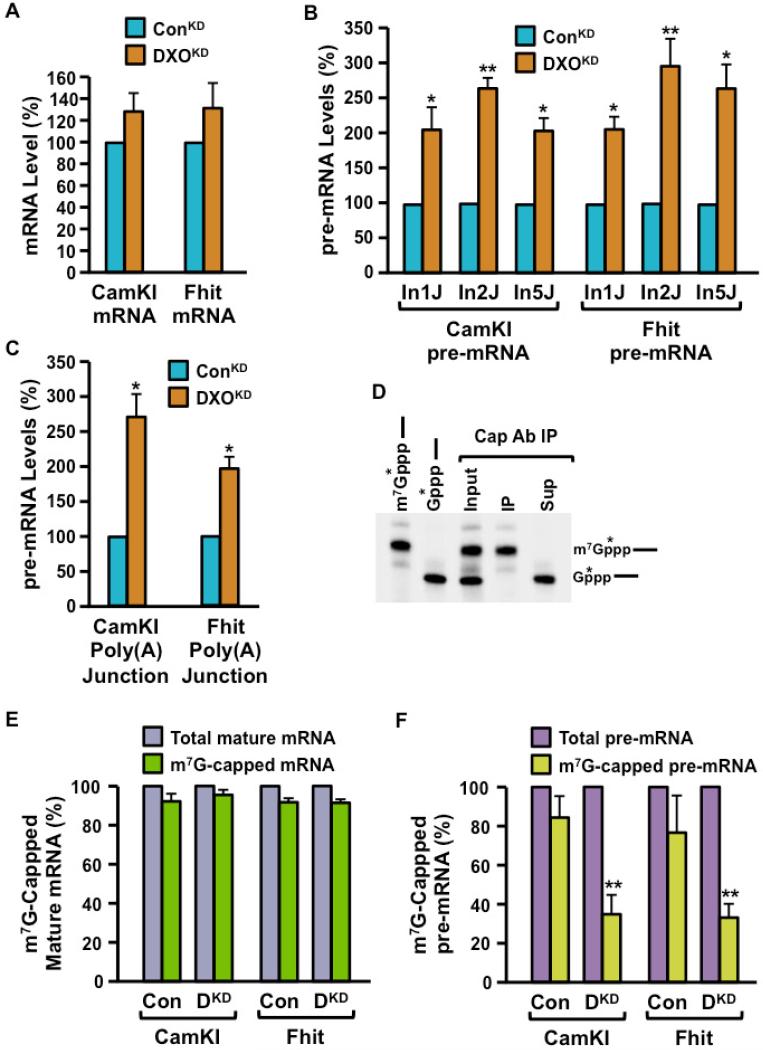

Having established the biochemical activities and the molecular mechanism of DXO, we next characterized the functions of this protein in mammalian 293T cells with an shRNA-directed >95% reduction of DXO (DXOKD, Figure S6). Our previous studies with Rai1 and Dxo1 showed that they mediate the clearance of incompletely capped mRNA in yeast cells (Jiao et al 2010, Chang et al 2012). Using primer pairs that span two different exons to detect spliced mRNA from two randomly selected mRNAs, CamKI and Fhit, we observed only a modest 20% increase in the steady-state levels of these mRNAs between control and DXOKD cells, (Figure 5A). However, analysis of the pre-mRNAs of the same genes revealed a more dramatic accumulation in the DXOKD cells. Using primers that span the exon 1-intron 1 junction to detect unspliced, intron 1-containing RNAs, we observed a 2-fold increase of both CamKI and Fhit pre-mRNAs under reduced DXO levels (Figure 5B). Since a link between capping and splicing of the first intron (but not subsequent introns) has been reported (Edery and Sonenberg, 1985; Izaurralde et al., 1994; Konarska et al., 1984), we next tested whether the increased level of pre-mRNA in the DXOKD cells was restricted to splicing of only the first intron. Surprisingly, the increase in CamKI and Fhit pre-mRNA levels were also detected when assessing several different downstream unspliced introns (Figure 5B), demonstrating that unspliced pre-mRNAs accumulate in DXOKD cells. These findings demonstrate an unexpected link of the capping process to splicing beyond only the first intron. Moreover, analysis of whether these transcripts are properly polyadenylated by qRT-PCR amplification through the poly(A) addition site shows an increase in uncleaved 3′ ends for both genes in the DXOKD cells relative to control cells (Figure 5C), suggesting a defect in the cleavage reaction of 3′-end processing in DXOKD cells. Collectively, these data indicate a role for DXO in degrading unprocessed pre-mRNAs and the first demonstration using an endogenously produced defectively capped pre-mRNA with defective processing.

Figure 5. DXO preferentially functions to clear incompletely capped pre-mRNAs in cells.

(A) Total RNA isolated from control shRNA expressing (ConKD) or DXO-specific shRNA expressing (DXOKD) cells were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis with primers specific to the CamKI and Fhit mRNA. Values were normalized to the GAPDH mRNA and plotted relative to the control shRNA, which was arbitrarily set to 100.

(B) The relative levels of CamKI and Fhit pre-mRNA in ConKD and DXOKD cells were quantitated with primers that span intron-exon junctions 1, 2 and 5 (In1J, In2J, In5J respectively). The level in ConKD cells was arbitrarily set to 100.

(C) Total RNA isolated from ConKD and DXOKD cells subjected to qRT-PCR analysis with primers that span the CamKI and Fhit gene poly(A) addition site were used to determine the relative level of unpolyadenylated transcripts in DXOKD cells. Levels in the ConKD cells were arbitrarily set to 100.

(D) Methyl-capped RNAs were purified with monoclonal anti-trimethylguanosine antibody column under conditions that resolve methyl-capped from incompletely capped RNAs as described (Chang et al., 2012; Jiao et al., 2010). 0.5μg of total 293T RNA was spiked with in vitro generated N7-methylated and unmethylated cap-labeled RNAs prior to capped RNA affinity purification. RNAs bound or unbound to the column were isolated and resolved by denaturing urea PAGE. Identity of the individual RNAs used, the input mixture and the resulting resolved RNAs are indicated.

(E and F) Methyl-capped RNAs were purified with monoclonal anti-trimethylguanosine antibody column as in (D) (Chang et al., 2012; Jiao et al., 2010) and levels of methyl-capped CamKI and Fhit mRNA (E) or pre-mRNA (F) were quantitated by qRT-PCR and presented relative to the corresponding total level of mRNA or pre-mRNA respectively. Levels of the corresponding total mRNA was arbitrarily set to 100.

Data in all four panels were derived from at least three independent experiments and the error bars represent +/− SD. * represents p < 0.05; ** represents p < 0.01.

The preferential function of DXO on incompletely capped RNAs (Figures 1 and 2) and earlier in vitro demonstrations that suggested the polyadenylation cleavage step was facilitated by the mRNA cap (Cooke and Alwine, 1996; Flaherty et al., 1997; Gilmartin et al., 1988; Hart et al., 1985) suggests the increase in pre-mRNA observed in Figure 5B and 5C would correspond to incompletely capped pre-mRNAs. To test this hypothesis, methyl-capped or incompletely capped RNA populations were resolved with anti-cap immunoprecipitation under conditions that retain methyl-capped, but not unmethylated capped or uncapped RNAs (Figure 5D) (Chang et al., 2012; Jiao et al., 2010). As expected, the level of methyl-capped mature CamKI and Fhit mRNAs were comparable between control and DXOKD cells (Figure 5E). In contrast, a significant decrease in the level of methylated capped pre-mRNAs was detected in the DXOKD cells relative to the corresponding total pre-mRNA when compared to that observed in control cells (Figure 5F). The relative decrease in methyl-capped pre-mRNA as a proportion of total pre-mRNA in the DXOKD cells indicates a corresponding increase of defectively capped pre-mRNAs relative to total pre-mRNA.

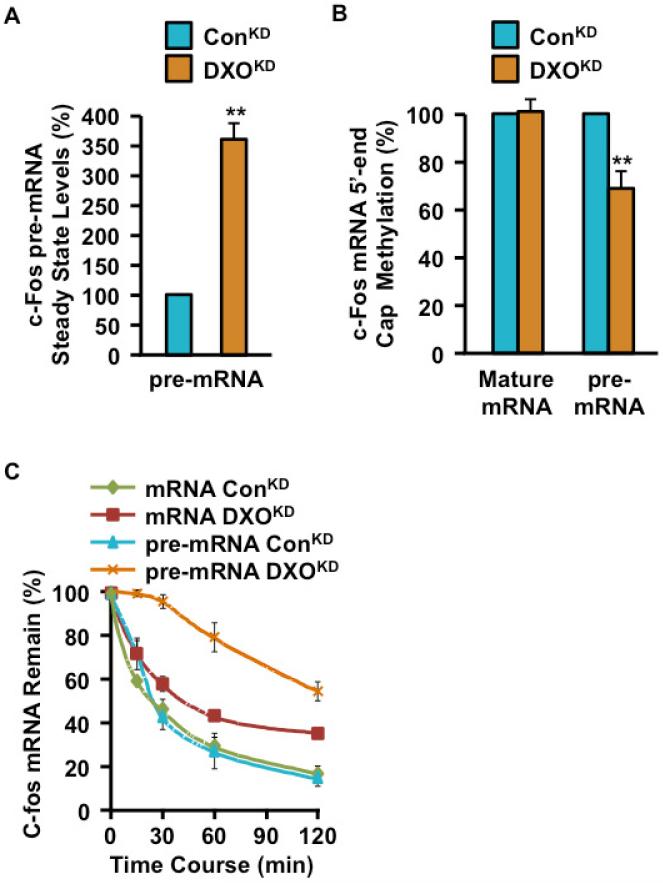

To determine whether the increased level of pre-mRNAs in the DXOKD cells can be attributed to pre-mRNA stability, we next characterized the effect of DXO on a short-lived mRNA, c-fos. Similar to CamKI and Fhit, levels of c-fos pre-mRNA also increased in the DXOKD cells (Figure 6A) while methyl-capped pre-mRNA decreased (Figure 6B), corresponding to an increase in defectively capped pre-mRNAs. Moreover, as would be predicted from the above data, DXO selectively influenced stability of the c-fos pre-mRNA, but not the c-fos mRNA following actinomycin D directed transcriptional silencing (Figure 6C). Stability of the c-fos pre-mRNA increased >5 fold in DXOKD cells relative to control cells with a t1/2 of 130 min versus 25 min. A similar increase was not detected with the c-fos mRNA indicating that DXO preferentially functions on pre-mRNAs lacking a normal m7G cap at the 5′ end.

Figure 6. Defectively capped c-fos pre-mRNAs were stabilized in the absence of DXO in cells.

(A) Steady state levels of c-fos pre-mRNA in 293T cells expressing control shRNA (ConKD) or DXO-specific shRNA (DXOKD) were determined by qRT-PCR with primers that span intron 1 exon 2-junction and presented relative to GAPDH mRNA levels. Levels of c-fos pre-mRNA in the ConKD cells were arbitrarily set to 1.

(B) Methyl capped RNAs were isolated as in Figure 5D-F from ConKD and DXOKD cells and levels of mature c-fos mRNA determined with primers that span exons 1 and 2 and c-fos pre-mRNA as in (A) above. A reduce level of methylated capped c-fos, pre-mRNA was detected in the DXOKD cells.

(C) Stability of c-fos mRNA and pre-mRNA was determined in the indicated cells following actinomycin D transcriptional arrest. Data are presented relative to corresponding levels of GAPDH mRNA.

Data in all three panels were derived from three independent assays with ±SD denoted by the error bars.

DISCUSSION

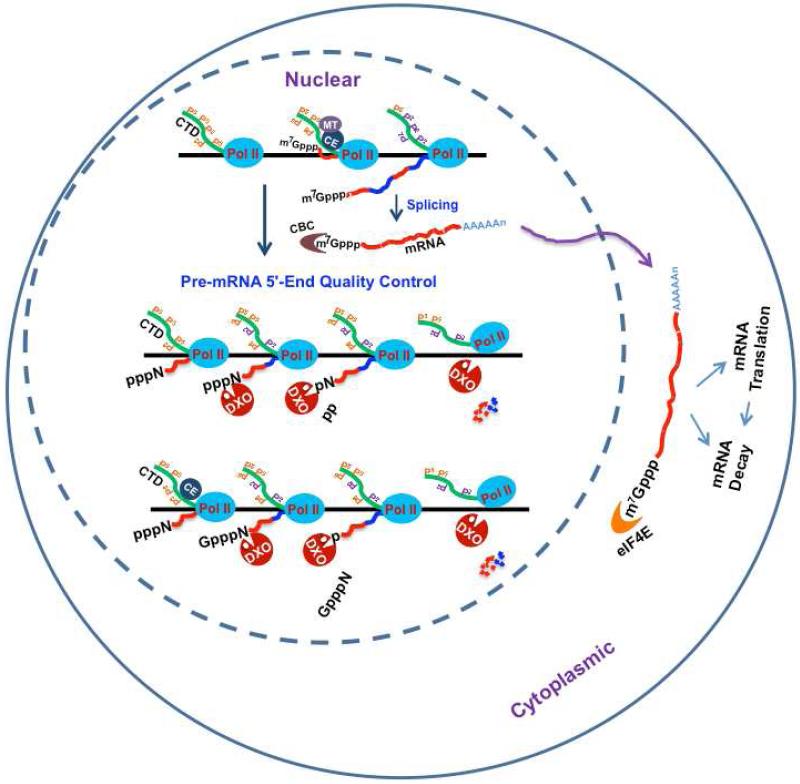

We report here that the mammalian Dom3Z/DXO protein is a dual nuclease that preferentially functions on incompletely capped pre-mRNAs. DXO removes the entire cap structure to generate a 5′-end monophosphate that subsequently serves as a substrate for a second catalytic activity intrinsic to the same DXO active site, a 5′- 3′ exoribonuclease activity to degrade the RNA body and defectively capped RNAs accumulate in DXOKD cells. These findings reinforce our recent demonstrations in S. cerevisiae (Chang et al., 2012; Jiao et al., 2010) that cap addition is not a default process that always proceeds to completion. Importantly, our data also reveal that pre-RNAs in mammalian cells with an aberrant 5′ end do not efficiently proceed into the normal RNA processing pathways of splicing and polyadenylation. The lack of efficient processing of incompletely capped pre-mRNAs that are more apparent following DXO knock down implicates DXO in a pre-mRNA quality control mechanism that detects and degrade defective pre-mRNAs (summarized in Figure 7).

Figure 7. Model of 5′-end quality control in mammalian cells.

Incompletely 5′-end capped pre-mRNA (unmethylated capped and uncapped 5′ triphosphate pre-mRNA) would be preferentially detected by DXO and subjected to 5′-end cleavage and degradation. The RNA Polymerase II (Pol II), the carboxyl terminal domain of RNAP II (CTD), the triphosphatase-guanylyltransferase capping enzyme (CE), the methyltransferase (MT), the nuclear cap binding complex (CBC) and the cytoplasmic cap binding protein, eIF4E, are as indicated.

Biochemical Activities of DXO

We have thus far identified two fungal proteins that possess decapping activity on incompletely capped mRNAs, the nuclear Rai1 protein (Jiao et al., 2010; Xiang et al., 2009) and the previously uncharacterized Ydr370C gene product, which encodes the predominantly cytoplasmic Dxo1 protein (Chang et al., 2012). Based on sequence homology, DXO was initially proposed to be the mammalian homolog of Rai1 (Xue et al. 2000), however, structural analysis reveals all three proteins share extensive identity (Chang et al., 2012; Xiang et al., 2009) and biochemical studies suggest DXO is a hybrid of both fungal proteins. In vitro, Rai1 functions on unmethylated capped RNA (GpppRNA) and 5′ triphosphate RNA (pppRNA) (Jiao et al., 2010; Xiang et al., 2009). Dxo1 functions on methylated (m7GpppRNA) and unmethylated (GpppRNA) capped RNA, but not 5′ pppRNA while DXO can function on all three substrates (Figure 1). Both Dxo1 and DXO possess intrinsic 5′ to 3′ exonuclease activity ((Chang et al., 2012); and Figure 1). One unanimous function for all three proteins is their preferential decapping of GpppRNA (summarized in Table S1). Collectively, Rai1, Dxo1 and DXO identify a novel class of proteins that function in a quality control mechanism to ensure proper mRNA 5′-end fidelity where DXO preferentially functions to contain incompletely capped pre-mRNAs (Figure 7).

Molecular basis of the distinct DXO catalytic activities

The structures of the pU5, pU(S)6 and cap complexes provide elegant insights into the catalytic mechanism of DXO and related enzymes, and indicate that the three distinct catalytic activities are mediated by the same active site machinery. The pU5 RNA is bound as a product, mimicking the RNA body. The 5′-end phosphate group of pU5 is the scissile phosphate, recognized by the enzyme through two metal ions. The catalytic nucleophile is a water/hydroxide bound to and activated by one of the metal ions, most likely the sole water ligand of Mg1 in the pU5 complex, which is also activated by Glu192 (Figure 3E). This water is located about 3.9 Å from the phosphorus atom, and is at the correct position for an inline attack. The terminal oxygen atom opposite of this water is then the leaving group, and the oxyanion can be stabilized by the side chain of Lys255 (motif IV) (Figure 4D). This two metal ion mechanism is similar to that employed by many other nucleases (Yang, 2011).

The structure shows that the cap (m7GpppG) is accommodated on the other side of the catalytic machinery from the RNA body (the pU5 oligo) (Figure 4D), thereby explaining the decapping activity that removes (m7)GpppG. Similarly, the structure of the pU(S)6 complex shows that the 5′-end nucleotide (pN1) or pyrophosphate group can also be accommodated across the active site (Figure 4D), giving rise to 5′-3′ exonuclease or PPH activity. Therefore, the three catalytic activities of these enzymes use the same catalytic machinery, and it is the distinct binding modes of the three different substrates that dictate the outcome of the reaction. Nevertheless, each of the DXO/Rai1/Dxo1 enzymes also has its unique properties, such as the lack of PPH activity by Dxo1 and the selectivity between GpppRNA and m7GpppRNA by Rai1 and Dxo1 (Chang et al., 2012; Xiang et al., 2009). Further studies will be needed to define the molecular mechanism for these unique properties.

DXO in methylated capped mRNA decapping

The ability of DXO to function on m7G capped RNA in vitro (Figure 1) indicates that DXO may also contribute to m7G capped RNA decapping and decay. The finding that cap-binding proteins can efficiently inhibit DXO activity (Figure 2) suggests any such activity is likely regulated and would require removal of cap binding proteins. The modest 20% increase in mRNA levels observed in the DXOKD cells (Figure 3A) is consistent with a potential limited role on m7G-capped mRNAs. In addition, the nuclear localization of DXO (Zheng et al., 2011) and its function on m2,2,7G capped RNA (Figure 1) also indicates that DXO may modulate trimethyl capped UsnRNAs. Future studies will address this possibility.

m7G cap and pre-mRNA processing

Our findings that incompletely capped pre-mRNAs are inefficiently spliced and polyadenylated demonstrates the cap is more intimately linked to splicing and polyadenylation than previously perceived. Initial studies that established a link between the cap and first intron splicing (Edery and Sonenberg, 1985; Inoue et al., 1989; Izaurralde et al., 1995; Izaurralde et al., 1994; Konarska et al., 1984) utilized either m7G capped mRNA with depleted cap-binding protein, or introduction of unmethylated capped pre-mRNA. In all cases, a requirement for the cap-binding protein was observed for first intron splicing consistent with the exon definition of splicing (Colot et al., 1996; Fortes et al., 1999; Izaurralde et al., 1994; Lewis et al., 1996). An important distinction with the current study is that we are following nascent transcripts that are generated without a proper cap. An appealing model could be that co-transcriptional cap addition is required to facilitate subsequent pre-mRNA processing and implies a co-transcriptional coordination of the capping process with splicing and polyadenylation factors to dictate pre-mRNA processing. One candidate that can coordinate these processes could be the cap-binding complex, CBC, which co-transcriptionally associates with the capped 5′ end and indirectly affects alternative splicing of a subset of genes in a transcript specific manner (Lenasi et al., 2011). Whether it is necessary, and involved, in recruiting splicing factors to intron-containing genes remains to be determined.

Our data reveal that incompletely capped pre-mRNAs do not efficiently proceed into the normal RNA processing pathways of splicing and polyadenylation and instead appear to be degraded by DXO. Importantly, such a quality control mechanism provides a dual layer of surveillance to prevent accumulation of potentially deleterious defectively capped pre-mRNAs whereby they are inefficiently processed into mature mRNA and selectively decapped and degraded by DXO from the 5′ end. Future studies will begin to uncover the molecular mechanism underlying such a surveillance process.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids and recombinant protein expression

Mutagenesis

Structure based site-specific mutations were created by PCR-based methods using the QuikChange kit (Stratagene) and sequenced to confirm correct incorporation of the mutations.

Protein expression, purification and crystallization

The protocols for expression, purification and crystallization of mouse DXO have been reported earlier (Xiang et al., 2009). The mutant proteins were purified by Ni-NTA and gel filtration chromatography, following the same protocol as that for the wild-type enzyme. Free enzyme crystals of DXO were obtained with the sitting-drop vapor diffusion method at 20 °C, using a reservoir solution containing 20% (w/v) PEG 3350. The pU5-Mg2+ complex was obtained by soaking the free enzyme crystals with 10 mM pU5 and 10 mM MgCl2 for 90 min in the presence of 15% ethylene glycol. The pU(S)6-Ca2+ complex was obtained by soaking with 10 mM pU(S)6 (6-mer oligoU RNA with a 5′-end phosphate and phosphorothioate groups between U1-U2 and U2-U3) and 20 mM CaCl2 for 120 min in the presence of 15 % ethylene glycol. The m7GpppG complex was obtained by soaking with 5 mM m7GpppG for 30 min in the presence of 15% ethylene glycol. Crystals were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen for diffraction analysis and data collection at 100 K.

Data collection and structure determination

X-ray diffraction data were collected at the National Synchrotron Light Source (NSLS) beamline X29A. The diffraction images were processed and scaled with the HKL package (Otwinowski et al., 1997). The crystals belong to space group P21, with cell parameters of a=50.0 Å, b=87.7 Å, c=53.9 Å and =112.2°. There is one molecule of DXO in the crystallographic asymmetric unit. The structure refinement was carried out with the CNS program (Brunger et al., 1998). The atomic model was built with the program Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004). The crystallographic information is summarized in Table 1.

Cell culture and generation of stably transformed knock-down cell line

Human 293T embryonic kidney cells were obtained from ATCC and cultured according to the supplier. DXO-specific shRNA plasmid and control nonspecific shRNA plasmids were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and transfections were carried out with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Monoclonal lines of stably transformed DXO cells expressing DXO-specific shRNA (DXOKD) were selected with puromycin (3μg/ml) and confirmed by Western Blotting. Monoclonal stably transformed 293T cells expressing FLAG tagged DXO were generated with pIRES-puro-FLAG-DXO plasmid.

RNA generation

RNA corresponding to the pcDNA3 polylinker (pcP) region with a 3′end containing 16 guanosines were transcribed in vitro using T7 polymerase to generated pcP RNA with an N7-methylated or unmethylated 5′ cap, or no cap as previously described (Chang et al., 2012; Jiao et al., 2010). Tri-methylated 32P-cap-labeled pcP RNA was generated in the capping reaction in the presence of human recombinant tri-methyltransferase (Benarroch et al., 2010) and SAM. 3′-end 32P-labeled RNA was generated with T4 RNA Ligase and [32P]pCp (Wang and Kiledjian, 2000a). In vitro transcriptions were carried out in the presence of [γ32P]GTP for 5′-end 32P-labeled triphosphate RNA or with [α32P]GTP to obtain 32P-uniform-labeled RNAs as described (Jiao et al., 2006). 5′-monophosphate 32P-uniform-labeled RNAs were generated by digesting methyl-capped 32P-uniform-labeled RNA with human Dcp2 decapping enzyme. RNA lacking a phosphate at the 5′-end was generated by treating 32P-uniform-labeled triphosphate RNA with Calf-intestinal alkaline phosphatase (CIP). Fluorescently labeled RNA oligos (Chang et al., 2012) were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT).

RNA decapping and in vitro decay assay

Decapping reactions used either His-tagged mouse DXO wild type or mutant recombinant protein (25nM) was incubated with 32P-cap-labeled or 32P-5′end-labeled pcP RNAs in decapping buffer as previously described (Jiao et al., 2010) at 37°C 30 minutes. Exoribonuclease assays were carried out with 100nM His-DXO in the same buffer. The decapping products were resolved by polyethyleneimine-cellulose TLC (PEI-TLC) plates and the decay reactions were resolve by 5% denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Exonuclease assays with fluorescently labeled RNA

The 3′-FAM labeled 30-mer RNA with 5′-end monophosphate (Sinturel et al., 2009b) and the equivalent ssDNA oligos were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT). Exonuclease assays were performed at 37 °C for 30 min with reaction mixtures containing 30 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 50 mM NH4Cl, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM DTT, 25 g ml−1 BSA, 2 μM 3′-FAM labeled oligos and indicated amount of recombinant DXO. The products were fractionated by 5% denaturing polyacrylamide gel and visualized on a UV illuminator. Assays were repeated at least three times to ensure reproducibility.

RNA isolation

Total RNAs were isolated with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) under the manufacturer’s protocol and treated with RQ1 DNase (Promega) to remove the genomic DNA contamination. For mRNA in vivo stability assay, the transcriptions of 293T control or DXOKD cells were blocked by actinomycin D (5μg/ml). Cells were harvested at indicated time points following treatment.

Methylated capped RNA immunoprecipitation

Methylated capped RNAs were immunoprecipitated utilizing monoclonal anti-trimethylguanosine antibody column (Calbiochem) as previously described (Chang et al., 2012; Jiao et al., 2010) from 30ng rRNA minus RNA using one round immunoprecipitation. Ribosomal RNA depletion was carried out from 0.5μg total RNA using the RiboMinus kit (Invitrogen).

Real-Time Quantitative Reverse Transcription and PCR

RNAs were reverse transcribed into cDNA with random primers and M-MLV reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer (Promega). For detecting pre-mRNA, the reverse transcription was preformed with gene specific pre-mRNA primers. Real-time PCR was performed using iTaq Supermix (BioRad) on ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Jiao 2006, Jiao 2010). Each gene was amplified using the appropriate specific primers (Table S2). mRNA levels were computed by the comparative Ct method and normalized to internal control 18S rRNA or glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) mRNA.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

-

-

Dom3Z/DXO has pyrophosphohydrolase, decapping and 5′-3′ exoribonuclease activities.

-

-

Dom3Z/DXO preferentially degrades incompletely capped pre-mRNAs.

-

-

Incompletely capped pre-mRNAs are inefficiently spliced at internal introns.

-

-

Incompletely capped pre-mRNAs are inefficiently cleaved for polyadenylation.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank S. Shuman (Memorial Sloan-Kettering) for providing the expression plasmid for the tri-methyltransferase. This research was supported by NIH grants GM090059 to LT and GM067005 to MK.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information including Extended Experimental Procedures, 6 figures and 2 tables can be found with this article on line.

ACCESSION NUMBERS

The atomic coordinates have been deposited at the Protein Data Bank, with accession codes 4J7L, 4J7M and 4J7N

REFERENCES

- Benarroch D, Jankowska-Anyszka M, Stepinski J, Darzynkiewicz E, Shuman S. Cap analog substrates reveal three clades of cap guanine-N2 methyltransferases with distinct methyl acceptor specificities. RNA. 2010;16:211–220. doi: 10.1261/rna.1872110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT, Adams PD, Clore GM, DeLano WL, Gros P, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Jiang JS, Kuszewski J, Nilges M, Pannu NS, et al. Crystallography & NMR system: A new software suite for macromolecular structure determination. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 1998;54:905–921. doi: 10.1107/s0907444998003254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calero G, Wilson KF, Ly T, Rios-Steiner JL, Clardy JC, Cerione RA. Structural basis of m7GpppG binding to the nuclear cap-binding protein complex. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:912–917. doi: 10.1038/nsb874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JH, Jiao X, Chiba K, Kiledjian M, Tong L. Dxo1, a novel eukaryotic enzyme with both decapping and 5′-3′ exoribonuclease activity. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2381. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colot HV, Stutz F, Rosbash M. The yeast splicing factor Mud13p is a commitment complex component and corresponds to CBP20, the small subunit of the nuclear cap-binding complex. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1699–1708. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke C, Alwine JC. The cap and the 3′ splice site similarly affect polyadenylation efficiency. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2579–2584. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.6.2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decker CJ, Parker R. A turnover pathway for both stable and unstable mRNAs in yeast: evidence for a requirement for deadenylation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:1632–1643. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.8.1632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunckley T, Parker R. The DCP2 protein is required for mRNA decapping in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and contains a functional MutT motif. EMBO J. 1999;18:5411–5422. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.19.5411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edery I, Sonenberg N. Cap-dependent RNA splicing in a HeLa nuclear extract. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985;82:7590–7594. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.22.7590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2004;60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer PM. Cap in hand: targeting eIF4E. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:2535–2541. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.16.9301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flaherty SM, Fortes P, Izaurralde E, Mattaj IW, Gilmartin GM. Participation of the nuclear cap binding complex in pre-mRNA 3′ processing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:11893–11898. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.11893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortes P, Kufel J, Fornerod M, Polycarpou-Schwarz M, Lafontaine D, Tollervey D, Mattaj IW. Genetic and physical interactions involving the yeast nuclear cap-binding complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:6543–6553. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.10.6543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furuichi Y, Shatkin AJ. Viral and cellular mRNA capping: past and prospects. Adv Virus Res. 2000;55:135–184. doi: 10.1016/S0065-3527(00)55003-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh A, Lima CD. Enzymology of RNA cap synthesis. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2010;1:152–172. doi: 10.1002/wrna.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin GM, McDevitt MA, Nevins JR. Multiple factors are required for specific RNA cleavage at a poly(A) addition site. Genes Dev. 1988;2:578–587. doi: 10.1101/gad.2.5.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gingras AC, Raught B, Sonenberg N. eIF4 initiation factors: effectors of mRNA recruitment to ribosomes and regulators of translation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1999;68:913–963. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.68.1.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodfellow IG, Roberts LO. Eukaryotic initiation factor 4E. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2008;40:2675–2680. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2007.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart RP, McDevitt MA, Nevins JR. Poly(A) site cleavage in a HeLa nuclear extract is dependent on downstream sequences. Cell. 1985;43:677–683. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90240-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu CL, Stevens A. Yeast cells lacking 5′-->3′ exoribonuclease 1 contain mRNA species that are poly(A) deficient and partially lack the 5′ cap structure. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:4826–4835. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.8.4826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue K, Ohno M, Sakamoto H, Shimura Y. Effect of th cap structure on pre-mRNA splicing in Xenopus oocyte nuclei. Genes Dev. 1989;3:1472–1479. doi: 10.1101/gad.3.9.1472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaurralde E, Lewis J, Gamberi C, Jarmolowski A, McGuigan C, Mattaj IW. A cap-binding protein complex mediating U snRNA export. Nature. 1995;376:709–712. doi: 10.1038/376709a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izaurralde E, Lewis J, McGuigan C, Jankowska M, Darzynkiewicz E, Mattaj IW. A nuclear cap binding protein complex involved in pre-mRNA splicing. Cell. 1994;78:657–668. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90530-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao X, Wang Z, Kiledjian M. Identification of an mRNA-Decapping Regulator Implicated in X-Linked Mental Retardation. Mol Cell. 2006;24:713–722. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao X, Xiang S, Oh C, Martin CE, Tong L, Kiledjian M. Identification of a quality-control mechanism for mRNA 5′-end capping. Nature. 2010;467:608–611. doi: 10.1038/nature09338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konarska MM, Padgett RA, Sharp PA. Recognition of cap structure in splicing in vitro of mRNA precursors. Cell. 1984;38:731–736. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenasi T, Peterlin BM, Barboric M. Cap-binding protein complex links pre-mRNA capping to transcription elongation and alternative splicing through positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb) J Biol Chem. 2011;286:22758–22768. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.235077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis JD, Izaurralde E, Jarmolowski A, McGuigan C, Mattaj IW. A nuclear cap-binding complex facilitates association of U1 snRNP with the cap-proximal 5′ splice site. Genes Dev. 1996;10:1683–1698. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.13.1683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Song M, Kiledjian M. Differential utilization of decapping enzymes in mammalian mRNA decay pathways. RNA. 2011;17:419–428. doi: 10.1261/rna.2439811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Kiledjian M. Decapping the message: a beginning or an end. Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:35–38. doi: 10.1042/BST20060035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lykke-Andersen J. Identification of a human decapping complex associated with hUpf proteins in nonsense-mediated decay. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:8114–8121. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.23.8114-8121.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcotrigiano J, Gingras AC, Sonenberg N, Burley SK. Cocrystal structure of the messenger RNA 5′ cap-binding protein (eIF4E) bound to 7-methyl-GDP. Cell. 1997;13:951–961. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80280-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuo H, Li H, McGuire AM, Fletcher CM, Gingras AC, Sonenberg N, Wagner G. Structure of translation factor eIF4E bound to m7GDP and interaction with 4E-binding protein. Nat Struct Biol. 1997;4:717–724. doi: 10.1038/nsb0997-717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazza C, Segref A, Mattaj IW, Cusack S. Large-scale induced fit recognition of an m(7)GpppG cap analogue by the human nuclear cap-binding complex. EMBO J. 2002;21:5548–5557. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merrick WC. Cap-dependent and cap-independent translation in eukaryotic systems. Gene. 2004;332:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer S, Temme C, Wahle E. Messenger RNA turnover in eukaryotes: pathways and enzymes. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2004;39:197–216. doi: 10.1080/10409230490513991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shatkin AJ. Capping of eucaryotic mRNAs. Cell. 1976;9:645–653. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90128-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinturel F, Pellegrini O, Xiang S, Tong L, Condon C, Benard L. Real-time fluorescence detection of exoribonucleases. RNA. 2009a;15:2057–2062. doi: 10.1261/rna.1670909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinturel F, Pellegrini O, Xiang S, Tong L, Condon C, Benard L. Real-time fluorescence detection of exoribonucleases. RNA. 2009b;15:2057–2062. doi: 10.1261/rna.1670909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MG, Li Y, Kiledjian M. Multiple mRNA decapping enzymes in mammalian cells. Mol Cell. 2010;40:423–432. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Jiao X, Carr-Schmid A, Kiledjian M. The hDcp2 protein is a mammalian mRNA decapping enzyme. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:12663–12668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192445599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Kiledjian M. Identification of an erythroid-enriched endoribonuclease activity involved in specific mRNA cleavage. EMBO J. 2000a;19:295–305. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang S, Cooper-Morgan A, Jiao X, Kiledjian M, Manley JL, Tong L. Structure and function of the 5′-->3′ exoribonuclease Rat1 and its activating partner Rai1. Nature. 2009;458:784–788. doi: 10.1038/nature07731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue Y, Bai X, Lee I, Kallstrom G, Ho J, Brown J, Stevens A, Johnson AW. Saccharomyces cerevisiae RAI1 (YGL246c) is homologous to human DOM3Z and encodes a protein that binds the nuclear exoribonuclease Rat1p. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4006–4015. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4006-4015.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W. Nucleases: diversity of structure, function and mechanism. Q Rev Biophys. 2011;44:1–93. doi: 10.1017/S0033583510000181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng D, Chen CY, Shyu AB. Unraveling regulation and new components of human P-bodies through a protein interaction framework and experimental validation. RNA. 2011;17:1619–1634. doi: 10.1261/rna.2789611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.