Abstract

The aim of this article is to document the levels of HIV stigma reported by persons living with HIV infections and nurses in Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Swaziland and Tanzania over a one-year period. HIV stigma has been shown to affect negatively the quality of life for people living with HIV infection, their adherence to medication, and their access to care. Few studies have documented HIV stigma by association as experienced by nurses or other health care workers who care for people living with HIV infection. This study used standardized scales to measure the level of HIV stigma over time. A repeated measures cohort design was used to follow persons living with HIV infection and nurses involved in their care from five countries over a one-year period in a three-wave longitudinal design. The average age of PLHAs (n = 948) was 36.15 years (SD= 8.69), and 67.1% (n= 617) were female. The average age of nurses (n = 887) was 38.44 years (SD=9.63), and 88.6% (n=784) were females. Eighty-four percent of all PLHAs reported one or more HIV stigma event at baseline. This declined, but was still significant one year later when 64.9% reported experiencing at least one HIV stigma event. At baseline, 80.3% of the nurses reported experiencing one or more HIV stigma events and this increased to 83.7% one year later. The study documented high levels of HIV stigma as reported by both PLHAs and nurses in all five of these African countries. These results have implications for stigma reduction interventions, particularly focused at health care providers who experience HIV stigma by association.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, stigma, Africa, nurses, PLHAs

Introduction

The Africa-UCSF HIV/AIDS Stigma project has been studying the presentation of HIV-related stigma in Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Swaziland and Tanzania for the last six years. Over this period we have published qualitative descriptions of this form of illness-related stigma (Dlamini, et al., 2007; Greeff, et al., 2008; Kohi, et al., 2006; Makoae, et al., 2008; Naidoo, et al., 2007; Uys, et al., 2005), developed a conceptual model of HIV stigma (Holzemer, Uys, Makoae, et al., 2007), developed two instruments to measure the phenomenon as experienced by persons living with HIV infection (PLHAs) (Holzemer, Uys, Chirwa, et al., 2007) and by nurses (Uys, et al., 2009), and measured the interactions between stigma and quality of life over time (Greeff, et al., In review). The current paper describes the level of stigma over time in the five African countries.

There is general recognition of the fact that in some cases, and some places, HIV stigma is a serious problem (Parker & Aggleton, 2003). However, since quantitative measures of stigma have not been available in the African context until quite recently (Visser, Kershaw, Makin, & Forsyth, 2008), it has not been possible to describe the prevalence of such problems, and therefore the public health importance of the issue. As we have talked about our study, presented results at conferences and interacted with PLHAs and health service providers, the questions “So, how high is the level of stigma in our country?” or “How many people are experiencing HIV-related stigma?” were asked repeatedly. In some debates, the argument has been raised that other issues in HIV care should take precedence over stigma reduction. Some activists see arguments about HIV stigma as an excuse by health service providers and policy makers to explain poor service delivery. It is important not only to acknowledge that stigma exists, but also to describe the prevalence of HIV stigma in the lives of PLHAs in specific settings.

In our studies we have consistently worked with both PLHAs and nurses, exploring the experiences of HIV stigma of both groups, and developing instruments to measure HIV stigma in both groups. From our clinical experiences we know that PLHAs experience significant HIV stigma and we also have observed that nurses and other health care workers not only experience stigma themselves, but also stigmatize patients. This was supported when we interviewed PLHAs and heard many stories of their experiences with being stigmatized by health care workers. Since nurses are the largest number of health care workers (World Health Organization, 2006) and most of the authors are nurses, we focused this work on both PLHAs and nurses. This article describes HIV stigma experienced and reported by nurses and PLHAs over time in five countries in Africa.

Literature Review

Most quantitative studies reporting on the level of HIV-related stigma have focused on community-level stigma (Berger, Ferrans, & Lashley, 2001; Mak, et al., 2006). The first quantitative instrument of this kind developed for the African setting was published by Kalichman and colleagues (2005) and focuses on the level of stigma as manifested by communities about HIV or AIDS. Their research was done in South Africa, and they reported only on the qualities of their scale and not on the levels of stigma they found in the communities sampled. This strategy was previously criticized by Parker and Aggleton (2003) who were concerned with studies that focused so heavily “on the beliefs and attitudes of those who are perceived to stigmatize others” (p.15) on the basis that it leads to interventions that aim at “increasing tolerance” of PLHAs or “increasing empathy” with PLHAs, and results in inadequate attention being given to the social character of the stigma phenomenon itself.

Very few studies have addressed the issue of the prevalence or level of HIV stigma in a quantitative manner in the African context, from the perspective of those experiencing HIV stigma. These are mainly from our own study and address relationships between HIV stigma and other variables, such as missing ARVs (Dlamini, et al., 2009), quality of life (Greeff, et al., In review), and taking of ARVs (Makoae, et al., In press).

In reviewing the literature, we found no studies that addressed the issue of measuring HIV stigma by association among nurses or other health care workers, although this form of stigma has been described by many researchers in the African setting. In our study, we have found a robust relationship between the level of stigma experienced by nurses and their job satisfaction (Chirwa, et al., 2009), as well as their intent to migrate (Kohi, et al., in review). Mahendra, Gilborn, Bharat, et al. (2007) evaluated an HIV stigma reduction strategy in three Indian hospitals, but their instrument does not measure stigma by association, focusing on the attitudes of the general public.

Study Aim

The focus of this article is to report the level of stigma reported by a sample of PLHAs and nurses in five African countries over time. A major limitation of this data is that the sample was not drawn randomly, but represents a convenience sample.

The research questions were:

How much HIV stigma is being experienced by PLHAs and nurses?

Does the amount of HIV stigma being experienced by these two groups change over time?

Is there a difference between how the two types of nurse HIV stigma change over time?

Are there country differences in the amount of HIV stigma being experienced by these two groups?

Methodology

Research design

A repeated measures cohort design was used to follow persons living with HIV infection and nurses involved in their care in Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Swaziland and Tanzania over a one-year period in a three-wave longitudinal design.

Setting and Sample

Data were collected three times, from January 2006 to March 2007. Each site sought to gather data from 300 persons living with HIV infection and 300 nurses involved in their care, chosen using a purposive voluntary sampling approach. The PLHAs were recruited from HIV clinics, support groups, flyers in the community, and word-of-mouth referrals, and were invited to join the study. If they were interested in the study, appointments were made for them to meet with field workers in a convenient setting. Participants completed the instruments independently or were assisted in completing instruments by researchers or field workers. Respondents were reimbursed for transport and lunch was provided. For nurses, managers of the various health settings were approached to identify potential participants. Nurses received a small token of appreciation for their willingness to participate. The available sample of PLHAs and nurses who completed the instruments over all three points in time was approximately on-third less that the initial desired sample.

Instruments

Three instruments were used.

Demographic Questionnaire: The multi-item demographic questionnaire was used to obtain demographic, job, and illness related information from the nurses and PLHAs.

HASI-N (HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument –Nurses) (Uys, et al., 2009) is a 19-item instrument comprised of two factors. Factor I, Nurses Stigmatizing Patients, included items such as “A nurse provided poorer quality care to an HIV patient than to other patients” and “A nurse shouted at or scolded an HIV patient.” Factor II, Nurses Being Stigmatized, includes items such as “People said nurses who provide HIV/AIDS care are HIV-positive” and “Someone called a nurse names because she takes care of HIV/AIDS patients.” Nurses responded to the question, “Please mark how often you observed the event during the past three months.” A four-point Likert scale was used to capture their responses, including never, once or twice, several times, most of the time. The Cronbach alpha for the total instrument of 19 items was 0.90. Concurrent validity was tested by comparing the level of stigma with job satisfaction and quality of life. A significant negative correlation was found between stigma and job satisfaction. The HASI-N was inductively derived and measures the stigma experienced and enacted by nurses (Uys, et al., 2009).

HASI-P (HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument – People Living with HIV/AIDS) (Holzemer, Uys, Chirwa, et al., 2007) is a 33-item instrument that measures six dimensions of HIV-related stigma. PLHAs respond to the question, “In the past three months, how often did the following event happen because of your HIV status?” A four-level Likert response format was used that included never, once or twice, several times, or most of the time. The six factors include: (I) Verbal Abuse - Verbal behavior intended to harm the PLWA (e.g. ridicule, insults, blame), 8 items, alpha= 0.886; (II) Negative Self-Perception - Negative evaluation of self based on HIV status, 5 items, alpha=0.906; (III) Health Care Neglect - In a health care setting (e.g. hospital, clinic), offering a patient less care than is expected in the situation or than is given by others, or disallowing access to services, based on one’s HIV status, 7 items, alpha=0.832; (IV) Social Isolation - Deliberately limiting social contact with PLWA and/or breaking off relationships, based on one’s HIV status, 5 items, alpha=0.890; (V) Fear of Contagion - Any behavior which shows fear of close or direct contact with the PLWA or things s/he has used, for fear of being infected (e.g. not wanting close proximity; not wanting to touch; not wanting to touch/share an object; not wanting to eat together), 6 items, alpha=0.795; and (VI) Workplace Stigma -Disallowing access to employment/work opportunities based on one’s status, 2 items, alpha=0.758.

Protection of Human Subjects

The research protocol was approved by all of the seven Universities involved (see author list). Permission to conduct the study was also obtained from the appropriate local and central government authorities. People who were interested in the study were given information about its background, and were told that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time. They were also assured of confidentiality of information obtained. Following this explanation, those who agreed to participate each signed a written consent form. The consent process and the survey were conducted in either English or the local language of the country. In South Africa participants used English and Tswana; Malawi, Chichewa; Lesotho, Sesotho; Swaziland, SiSwazi; and Tanzania, Kiswahili.

Data Management and Analysis

Survey data were entered into Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) for Windows Version 15.0 software (2007). Data entry accuracy was assessed by having 10% of the surveys double entered and the two files were compared. We also ran descriptive statistics examining ranges to ensure the accuracy of the data. Discrepancies were resolved by examining the original surveys.

Stigma was measured by counting the number of times a stigma event was reported, with a potential maximum of 33 stigma events for PLHAs and 19 stigma events for nurses. For instance, the HASI-P scale has an item “People cut down on visiting me”. If a respondent ticked that this had happened during the last three months, it counted as one event, even though it might have happened more than once.

Results

The purpose of this article is to explore and estimate the amount of HIV stigma around persons living with HIV infection and nurses in five African countries.

Sample Description

The average age of the PLHAs (n = 948) was 36.15 years (SD= 8.69) and 67.1% (n= 617) were female. The average age of the nurses (n = 887) was 38.44 years (SD=9.63) and 88.6% (n=784) were female. Thirty-nine percent of the PLHAs had no post-school qualification, while 67% of the nurses had diplomas or advanced qualifications post-school. The majority of the PLHAs (34.9%) had never been married, while the majority of the nurses (62.5%) were married (see Table 1 for more details).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics at Baseline

| Variable | PLHAs (N = 948) | Nurses (N = 887) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Gender | ||

| Female | 617 (67.1%) | 784 (88.6%) |

| Male | 302 (32.9%) | 101 (11.4%) |

|

| ||

| Age | 36.15 | 38.44 years |

| SD = 8.69 | SD = 9.63 | |

|

| ||

| Post-school education | ||

| No post school | 151 (39.8%) | - |

| Certificate | 194 (51.2%) | 279 (32.2%) |

| Diploma/advanced | 34 (9%) | 587 (67.8%) |

|

| ||

| Marital status | ||

| Never married | 328 (34.9%) | 194 (23.3%) |

| Married | 259 (27.6%) | 519 (62.5%) |

| Widowed | 212 (22.6%) | 63 (7.6%) |

| Divorced | 86 (9.1%) | 42 (5.1%) |

| Cohabiting | 52 (5.5%) | 13 (1.6%) |

Stigma Experienced by PLHAs and Nurses

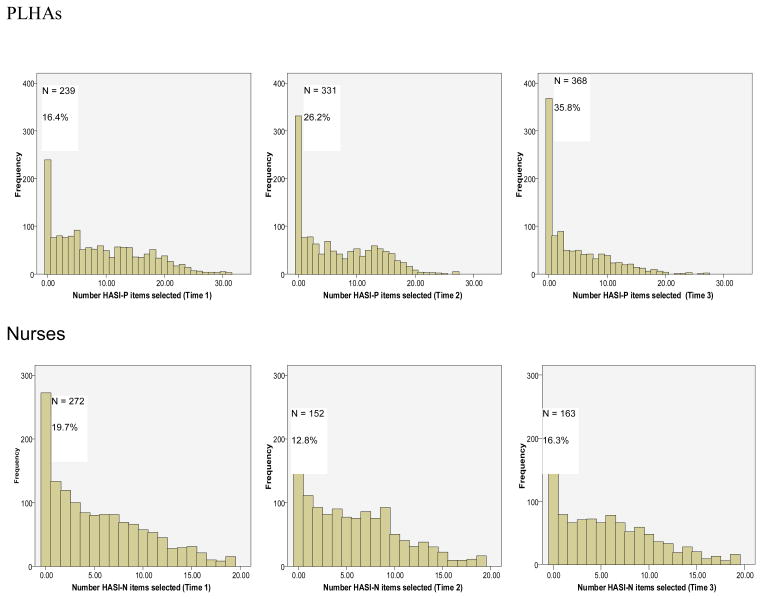

There is tremendous variation in self-reported stigma among both the PLHAs and nurses (see Figure 1). Note that in Figure 1 the horizontal (X) axis has a maximum of 33 events (items) for PLHAs and a maximum of 19 events (items) for nurses. The histograms presented in Figure 1 show that many PLHAs reported no experiences of HIV stigma during the past three months at each point in time, and that the frequency of HIV stigma events declined over time. The first column, which indicates how many PLHAs reported having experienced no stigma events over the last three months, increased from 16.4% (n=239) at baseline to 35.8% (n=368) at 12 months. The corresponding data for nurses do not indicate such an improvement in the stigma experience over time. Approximately 20% (n=272) of nurses reported experiencing no stigma events during the last three months at baseline, and this decreased to 16.3% (n=163) at Time 3. Nurses reported experiencing more stigma events over time whereas PLHAs reported less stigma events over time.

Figure 1.

Frequency of Reported HIV Stigma among PLHAs and Nurses over time

Figure 1 also indicates that fewer PLHAs report high levels of stigma events (25 events or more) as compared with the nurses (15 events of more). This is particularly evident at six (Time 2) and twelve (Time 3) months. In summary, 83.6% of all PLHAs reported one or more HIV stigma events at baseline and this decreased, but was still significant one year later when 64.9% reported experiencing at least one HIV stigma event. At baseline, 80.3% of the nurses reported experiencing one or more HIV stigma events and this increased to 83.7% one year later.

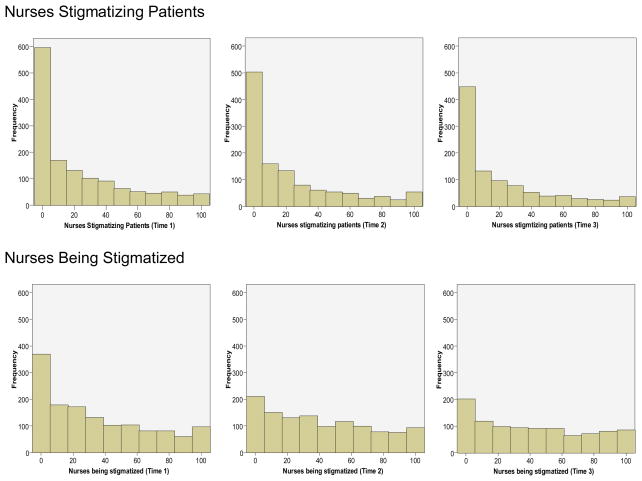

To explore the nurse data further, we standardized the frequency of reporting HIV stigma events for nurses for each of the two sub-scales. We divided the number of events selected for each scale by the number of items in that scale and multiplied the proportion by 100. Histograms (Figure 2) were prepared demonstrating that nurses are reporting fewer episodes of Factor 1, Nurses Stigmatizing Patients, but an increase in events in Factor 2, Nursing Being Stigmatized.

Figure 2.

Comparison of Factor 1 (Nurses stigmatizing patients) with Factor 2 (Nurses being stigmatized) over time

To explore the change in mean number of nurse stigma events over time, we conducted two separate ANOVAs for each of the nurse stigma factor scores (Table 2). There was no significant difference over time for Factor 1, Nurses Stigmatizing Patients. There was a significant difference over time for Factor 2, Nurses Being Stigmatized (F=30.41; df = 2, 1766; p = < .000). Nurses reported experiencing more Factor 2 HIV stigma events at Times 2 and 3 than at Time 1.

Table 2.

Two Repeated Measures ANOVA for the Two Nurse Stigma Factors.

| Country | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||

| N | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | F | df | p | |

| Factor 1: | ||||||||||

| Nurses Stigmatizing Patients (10 items; Range: 0–10) | 887 | 2.23 | 2.85 | 2.25 | 2.90 | 2.13 | 2.85 | 0.882 | 2,1772 | 0.41 |

| Factor 2: | ||||||||||

| Nurses Being Stigmatized (9 items; Range 0–9) | 884 | 2.99 | 2.90 | 3.69 | 2.92 | 3.73 | 3.02 | 30.41 | 2,1766 | 0.000 η2 = .03 |

PLHAs Stigma Events over Time by Country

PLHAs reported a significant decrease in stigma events over the three points in time (Table 3) (F = 154.97, df=2, 1886, p=<0.000; η2 = 0.14). While the PLHAs reported an average of 8.69 stigma events at baseline, the events decreased to an average of 4.42 at Time 3.

Table 3.

Country (5 levels) by Time (3 levels) Repeated Measures ANOVA Comparing PLHA’s Total Stigma Score

| Country | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Totals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||

| N | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SE | |

| Lesotho | 174 | 13.40 | 5.92 | 10.50 | 5.40 | 3.58 | 4.02 | 9.16 | 0.33 |

| Malawi | 189 | 6.94 | 7.21 | 3.19 | 5.73 | 3.75 | 5.75 | 4.64 | 0.31 |

| South Africa | 281 | 6.61 | 5.75 | 5.19 | 5.45 | 3.41 | 4.61 | 5.07 | 0.26 |

| Swaziland | 130 | 7.15 | 7.01 | 6.78 | 6.14 | 5.47 | 5.03 | 6.47 | 0.38 |

| Tanzania | 174 | 10.50 | 5.40 | 6.47 | 6.76 | 6.80 | 6.17 | 8.35 | 0.33 |

|

| |||||||||

| Totals | 948 | 8.69 | 7.42 | 6.47 | 6.33 | 4.42 | 5.28 | ||

Time Main Effects: F = 154.97; df = 2, 1866; p = < 0.000

Country Main Effects: F = 41.18; df = 4, 943; p = < 0.000

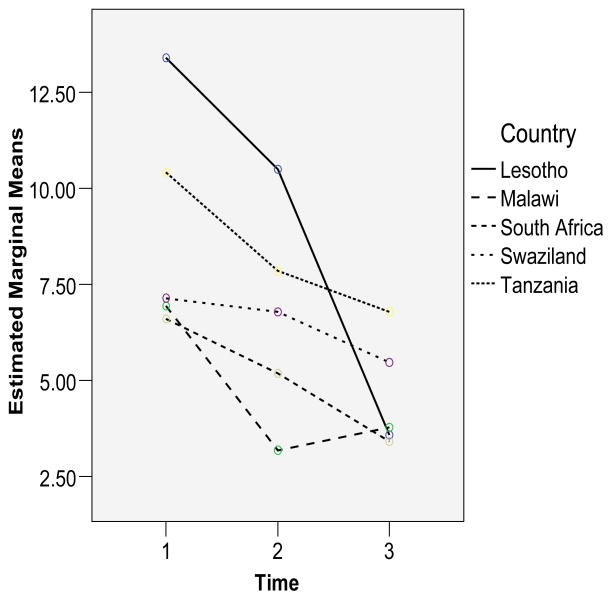

We explored potential country differences to see whether the decrease in experience of HIV stigma events was similar across the five countries. There is a significant difference between countries (F = 41.18, df = 4, 943, p=<0.000; η2 = 0.15). Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons showed that Lesotho and Tanzania reported higher stigma scores than Malawi, South Africa and Swaziland at the 0.05 level. While PLHAs in all countries reported significantly less stigma over time, Tanzania reported significantly less stigma at Time 3 (10.5 at baseline to 8.35 at Time 3). The interaction between country and time was also significant (F = 21.60, df=8, 1886, p=<0.000; η2 = 0.08).

To illustrate change in total stigma score for PLHAs over time, we plotted the total stigma scores (See Figure 3). The report by PLHAs of HIV stigma events decreased in all countries, although the countries demonstrated different patterns of change over time. These patterns cannot be interpreted easily given that the samples in each country were convenience samples.

Figure 3.

Mean Stigma Frequency by Country over time for PLHAs

Nurse Stigma Events Reported Over Time by Country

A country (five levels) by time (3 levels) repeated measures ANOVA for total Nurse stigma scale was calculated (Table 4). Reports of HIV stigma events increased significantly between baseline and Times 2 and 3 (F = 7.47, df=2, 1764, p=<0.001; η2 = 0.01) and there were significant differences between countries (F = 7.03, df=4,882, p=<0.000; η2 = 0.03). The Bonferroni post-hoc comparisons showed that Lesotho scored higher than South Africa and Tanzania. The interaction between country and time was also significant (F = 5.10, df=8, 1764, p=<0.000; η2 = 0.02). Overall, the effect sizes were very small, so that one can conclude that there were few meaningful differences among the nurses by countries over time.

Table 4.

Country (5 levels) by Time (3 levels) Repeated Measures ANOVA Comparing Nurses Total Stigma Scores.

| Country | Time 1 | Time 2 | Time 3 | Totals | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SE | |

| Lesotho | 168 | 6.67 | 5.16 | 6.95 | 4.39 | 6.84 | 4.71 | 6.82 | 0.29 |

| Malawi | 171 | 5.99 | 4.42 | 5.38 | 4.12 | 5.67 | 4.84 | 5.68 | 0.29 |

| South Africa | 185 | 4.92 | 4.95 | 5.99 | 5.08 | 5.65 | 4.80 | 5.52 | 0.28 |

| Swaziland | 137 | 5.80 | 4.70 | 5.90 | 5.36 | 5.97 | 4.91 | 5.58 | 0.32 |

| Tanzania | 226 | 3.43 | 4.31 | 5.64 | 4.87 | 5.36 | 4.91 | 4.81 | 0.25 |

|

| |||||||||

| Totals | 887 | 5.21 | 4.83 | 5.95 | 4.80 | 5.86 | 4.85 | ||

Country Main Effects: F = 7.03; df = 4, 882; p = <0.000.

Time Main Effects: F = 7.47; df = 2, 1764; p = <0.001

Discussion

This study documents that PLHAs and nurses reported high levels of HIV stigma events in all five African countries. One year after our study began, 64.2% of all PLHAs and 83.7% of nurses reported experiencing one or more HIV stigma event over the last three months. Because the scoring of these stigma scales in this analyses ignores the frequency with which these events happened, these can be considered conservative estimates of the percentage of individuals experiencing HIV stigma events.

The findings represent both encouraging and discouraging evidence of the amount of stigma being experiences by PLHAs and nurses. The significant reduction in reporting HIV stigma events over time amongst PLHAs is an important finding, and it was true for all five countries. However, the number of HIV stigma events experienced by PLHAs remained high over time. There is a need to remain vigilant in the search for effective HIV stigma reduction interventions, and in providing assistance to PLHAs to manage the HIV stigma that they experience. Nurses reported high levels of experiencing HIV stigma events over time and, unlike the PLHAs, this experience of HIV stigma events did not reduce over time, but rather increased. At the last measurement point, 83% of nurses reported experiencing one or more HIV stigma event over the last three months.

Most of the published measures of stigma have focused upon HIV stigma in the general population or as experienced only by PLHAs. No studies have documented stigma experienced by nurses or health care workers, or HIV stigma by association. These results indicate that stigma by association requires more attention, especially since our work indicates a link between job dissatisfaction and intentions to migrate among nurses, and HIV stigma experience (Chirwa, et al., 2009; Kohi, et al., in review).

Country differences are difficult to interpret due to the convenience sampling strategy adopted in this study. Nevertheless, the results indicate that it is important to do regional surveys of HIV stigma and not assume similarity across countries and regions.

This study reports data on a large sample of PLHAs and nurses, providing the first normative data using standardized instruments giving us a glimpse of what the level of HIV stigma events experiences by PLHAs and nurses is in five African countries. The limitations of the study included the convenient sampling of both PLHAs and nurses, and the fact that in larger countries only one geographical area was used. No normative data is available at the moment with which to compare the findings. We recommend that HIV stigma reduction strategies target health workers who experience HIV stigma by association, as well as continued attention to the stigma experienced by PLHAs.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH Research Grant #R01 TW06395 funded by the Fogarty International Center, the National Institute of Mental Health, and the Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Government

Contributor Information

William L. Holzemer, University of California, San Francisco, School of Nursing

Lucy N. Makoae, National University of Lesotho

Minrie Greeff, North-West University, Potchefstroom Campus, South Africa.

Priscilla S. Dlamini, University of Swaziland

Thecla W. Kohi, Muhimbili University of Health and Allied Sciences

Maureen L. Chirwa, College of Medicine, University of Malawi

Joanne R. Naidoo, University of KwaZulu-Natal

Kevin Durrheim, University of KwaZulu-Natal.

Yvette Cuca, University of California, San Francisco, School of Nursing.

Leana R. Uys, University of KwaZulu-Natal

References

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing and Health. 2001;24(6):518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chirwa ML, Greeff M, Kohi TW, Naidoo JR, Makoae LN, Dlamini PS, et al. HIV stigma and nurse job satisfaction in five African countries. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2009;20(1):14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2008.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlamini PS, Kohi TW, Uys LR, Phetlhu RD, Chirwa ML, Naidoo JR, et al. Verbal and physical abuse and neglect as manifestations of HIV/AIDS stigma in five African countries. Public Health Nurs. 2007;24(5):389–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2007.00649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dlamini PS, Wantland D, Makoae LN, Chirwa M, Kohi TW, Greeff M, et al. HIV Stigma and Missed Medications in HIV-Positive People in Five African Countries. Aids Patient Care and STDS. 2009 doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeff M, Phetlhu R, Makoae LN, Dlamini PS, Holzemer WL, Naidoo JR, et al. Disclosure of HIV status: experiences and perceptions of persons living with HIV/AIDS and nurses involved in their care in Africa. Qualitative Health Research. 2008;18(3):311–324. doi: 10.1177/1049732307311118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greeff M, Uys LR, Wantland D, Makoae L, Chirwa M, Dlamini P, et al. Perceived HIV stigma and life satisfaction among persons living with HIV infection in five African countries. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.09.008. (In review) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzemer WL, Uys L, Makoae L, Stewart A, Phetlhu R, Dlamini PS, et al. A conceptual model of HIV/AIDS stigma from five African countries. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2007;58(6):541–551. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holzemer WL, Uys LR, Chirwa ML, Greeff M, Makoae LN, Kohi TW, et al. Validation of the HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument - PLWA (HASI-P) AIDS Care. 2007;19(8):1002–1012. doi: 10.1080/09540120701245999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Jooste S, Toefy Y, Cain D, Cherry C, et al. Development of a brief scale to measure AIDS-related stigma in South Africa. AIDS and Behavior. 2005;9(2):135–143. doi: 10.1007/s10461-005-3895-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohi T, Makoae L, Chirwa M, Holzemer WL, Phetlhu DR, Leana Uys, Naidoo J, Dlamini PS, Greeff M. HIV and AIDS stigma violates human rights in five African countries. Nursing Ethics. 2006;13(4):405–414. doi: 10.1191/0969733006ne865oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohi TW, Portillo CJ, Durrheim K, Dlamini PS, Makoae LN, Greeff M, et al. Predictors of intent to migrate among nurses in five African countries. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.09.004. (in review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahendra VS, Gilborn L, Bharat S, Mudoi R, Gupta I, George B, et al. Understanding and measuring AIDS-related stigma in health care Settings: A developing country perspective. Sahara J. 2007;4(2):616–625. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2007.9724883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak WW, Mo PK, Cheung RY, Woo J, Cheung FM, Lee D. Comparative stigma of HIV/AIDS, SARS, and Tuberculosis in Hong Kong. Soc Sci Med. 2006;63(7):1912–1922. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makoae LN, Greeff M, Phetlhu RD, Uys LR, Naidoo JR, Kohi TW, et al. Coping with HIV-related stigma in five African countries. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2008;19(2):137–146. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makoae LN, Portillo CJ, Uys LR, Dlamini PS, Greeff M, Chirwa M, et al. The impact of ARV medication use on perceived HIV stigma in persons living with HIV infection in five African countries. AIDS Care. doi: 10.1080/09540120902862576. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naidoo J, Uys L, Greeff M, Holzemer W, Makoae L, Dlamini P, et al. Urban and rural differences in HIV/AIDS stigma in five African countries. African Journal of AIDS Research. 2007;6(1):17–23. doi: 10.2989/16085900709490395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual framework and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SPSS. SPSS Base 15.0 for Windows User’s Guide. Chicago, IL: SPSS Inc; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Uys LR, Chirwa M, Dlamini P, Greeff M, Kohi T, Holzemer WL, et al. Eating plastic, winning the lotto, joining the WWW: Descriptions of HIV/AIDS in Africa. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2005;16(3):11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2005.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uys LR, Holzemer WL, Chirwa ML, Dlamini PS, Greeff M, Kohi TW, et al. The development and validation of the HIV/AIDS Stigma Instrument - Nurse (HASI-N) AIDS Care. 2009;21(2):150–159. doi: 10.1080/09540120801982889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Visser MJ, Kershaw T, Makin JD, Forsyth BW. Development of parallel scales to measure HIV-related stigma. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(5):759–771. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9363-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global Workforce. Geneva: WHO; 2006. [Google Scholar]