Abstract

Pistacia integerrima Stew. ex Brand (Anacardiaceae) is an ethanobotanically important plant species traditionally used in the treatment of chronic wounds, jaundice, dysentery, etc. The crude extract from Pistacia integerrima and its fractions were tested for cytotoxic activity against Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 human breast cancer cell line. We have also investigated that crude stem extract of this plant also exhibits the antitumour as well as antifungal potential activities. Moreover, we have also studied that the crude extract inhibited Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 cell viability in a dose-dependent manner; the poor toxicity (1.6%) at 10 μg/ml to moderate toxicity (55.4%) at 100 μg/ml. The IC50 values calculated were 90.9 μg/ml. The ethyl acetate and chloroform fractions at a concentration of 200 μg/ml showed ~100 and 97.4% inhibition against Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 cell line, respectively. The crude methanol extract also showed good antitumour (IC50 125 ppm) activity, but weak antifungal activity. These findings reveal that the ethyl acetate and chloroform fractions of Pistacia integerrima are potent cytotoxic fractions, and could be an alternate candidate for the development of novel biologically active compounds.

Keywords: Antifungal, antitumour, cytotoxic, Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 cell line, Pistacia integerrima

The value of natural products in the treatment of ailments is well-known. Amongst the various natural sources, plants are an important source of bioactive constituents, including anticancer, antifungal and antimicrobial drugs. More than 1000 plant species are known for their anticancer potential[1]. Majority of them are now being used in the treatment of cancer, and the selection of these plants is based on either their ethanobotanical importance or bioassays results. An interesting example is Vinca alkaloids (vincristine and vinblastine) from Catharanthus roseus L. (Apocynaceae). The crude methanol extract of C. roseus exhibited significant anticancer activity against a number of cell lines in in vitro studies[2]. Similarly, etoposide from Podophyllum peltatum L. (Berberidaceae) also showed significant anticancer activity[3]. The stem bark extract of Taxus brevifolia (Taxaceae) and different parts of Camptotheca acuminata (Nyssaceae) also proved active during anticancer screening and finally lead to the isolation of the anticancer drugs, taxol and camptothecin derivatives, respectively[4].

Pistacia integerrima Stew. ex Brand (Anacardiaceae) is a large deciduous tree traditionally used in the treatment of coughs, phthisis, jaundice, antiseptic, chronic wounds, asthma and dysentery[5,6]. The aqueous extract of P. integerrima was found to be effective in the treatment of hepatic injury in carbon chloride (CCl4)-treated rats[7]. The hypouricemic, analgesic, antiinflammatory, and antioxidant activities of P. integerrima galls extract have also been evaluated[8,9]. The antioxidant, radical-scavenging and xanthine oxidase inhibitory activities were also found significant in leaf extract[9,10]. To the best of our knowledge, the anticancer activity of P. integerrima has not yet been investigated. We report herein antitumour and anticancer potential of P. integerrima against Michigan Cancer Foundation-7 (MCF-7) cell line through potato disc method and MTT assays, respectively. The antifungal activity and qualitative phytochemical analysis of the plant extract have also been demonstrated.

The fresh P. integerrima Stew. ex Brand plant material was collected in May 2007 from Margalla Hills, Islamabad, Pakistan and identified by Dr. Mir Ajab Khan, Department of Plant Sciences, Quaid-i-Azam University, Pakistan after comparison with an already present specimen in herbarium. Plant material was thoroughly washed, and dried under shade-controlled conditions. The dried material was ground to fine powder with a heavy duty grinding machine.

The cold maceration technique was used for extractions. The powdered plant material (2 kg) was soaked in 2000 ml methanol which was kept at room temperature. After 1 week, the extract was filtered under vacuum through Whatman Filter Paper No. 1. The residue was again soaked in methanol for additional 7 days and filtered thereafter. The filtrates were combined and methanol was evaporated under vacuum using rotary evaporator (Buchi Rotavapor R-200) at 45°. The dried extract (400 g) was stored at 4° until further analysis.

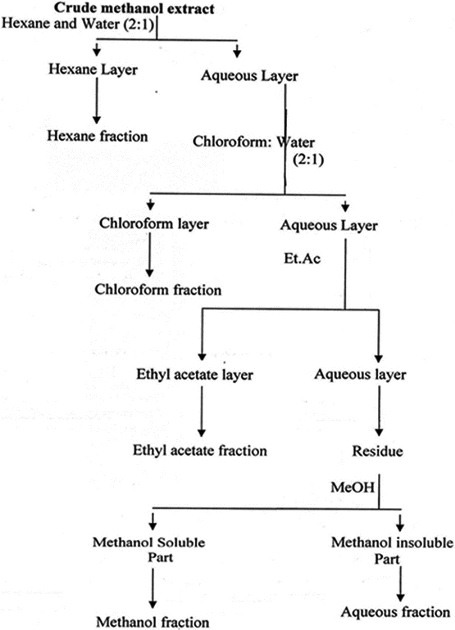

The fractionation of the crude extract was carried out by suspending 400 g of extract in 200 ml water and then partitioning with different organic solvents (hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate and methanol) in order of increasing polarity (fig. 1) by using a separating funnel. Each of the six fractions was dried by evaporating the respective solvent using a rotary evaporator. The quantities obtained were of 15, 100, 180, 40 and 30 g in hexane, chloroform, ethyl acetate, methanol and aqueous fractions, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Fractionation scheme of plants crude extracts

The antitumour activity is investigated by following the procedure reported by Fatima et al.[11]. The Agrobacterium tumefaciens virulent strain At10 was cultured for 48 h in Luria broth medium containing rifampicin (10 μg/ml). Under aseptic conditions, the red skinned potatoes were surface-sterilised with 0.1% mercuric chloride solution (w/v) for ~8 min, and thoroughly washed with autoclaved, distilled water. The potato discs (2×8 mm) were made with cork borer and placed on agar (2%) plates (10 discs per Petri plate). Inoculum-containing extract dissolved in DMSO (10, 100 and 1000 ppm) and Agrobacterium culture (OD600=1.0) was applied on the surface of each disc. Petri plates were sealed with Parafilm and incubated at 28°. After 21 days, few drops of Lugol's solution (10% KI and 5% I2) were applied on the surface of each disc in order to stain the discs. The normal potato cells containing starch were stained and the tumour cells lacking starch, remained unstained which become visible in the stained background. The number of tumours per disc was counted under the dissecting microscope. The test was performed in triplicate and percentage inhibition was calculated by the formula: % Inhibition=100−[Average number of tumours in sample/Average number of tumours in control]×100

Human breast adenocarcinoma MCF-7 cell line was donated by Portsmouth University Cell Culture Lab, United Kingdom. The cells were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin (10,000 units), streptomycin (10 mg/ml), and L-glutamine (200 mM) at 37° under 5% CO2 and relative humidity 95%. Crude extract and fractions were separately dissolved in dimethyl sulphoxide (DMSO) at a concentration of 2 mg/ml. Required dilutions in μg/ml were made under sterile conditions by adding calculated amounts of DMEM.

Standard 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay was used to evaluate cell line viability in the presence and absence of extracts[12]. In a 96-well plate, 100 μl of medium (RPMI 1640) was poured in each well and seeded with 5000 MCF-7 cells/well. Cells were allowed to attach on the surface of well overnight and then various concentrations of the crude extract (10-500 μl) and fractions (200 μl) were added to the respective wells. After 24 h incubation at 37°, 5% CO2 and relative humidity 95%, MTT reagent (10 μl) was added to each well. After further 4-h incubation, 100 μl of DMSO solution was added to each well to solubilise MTT crystals. The plates were again incubated overnight under the conditions mentioned above. The plates were read for optical density at 570 nm, using a plate reader. The test was performed in triplicate as independent experiment and data obtained from fractions assay were statistically analysed by analysis of variance (ANOVA) and least significant difference (LSD) using MSTATC.

The agar tube dilution method[11] was performed to determine the antifungal activity of plant extract. Three fungal strains were used which were Mucor species, Aspergillus fumigatus and Fusarium moliniforme. Fungal cultures were maintained on Sabouraud dextrose agar media in tubes in slanting position at 27°.

To perform the assay, media were prepared by mixing 32.5 g Sabouraud dextrose agar (Merck) in 500 ml of distilled water. It was dissolved on heating and 5 ml was poured in each screw cap tube. Tubes were labelled and autoclaved at 121° for 20 min. The tubes were allowed to cool and 100 μl of plant extract (20 mg/ml in DMSO) was added just before solidification to obtain a concentration of 400 μg/ml. For positive control, 83 μl of fluconazole (12 mg/ml in DMSO) was added in each tube to get a concentration of 200 μg/ml. Pure DMSO (100 μl/tube) was used as negative control. Tubes were shaken well and allowed to solidify in a slanting position at room temperature. A piece of fungal inoculum (4 mm diameter) from a 7-day old culture was inoculated in each tube. The tubes were incubated at 27° for 7 days. The growth was determined by measuring linear growth (mm). Test was performed in triplicate and growth inhibition was calculated with reference to negative control using the formula: % Inhibition of fungal growth=100−(Linear growth in test/Linear growth in control)×100

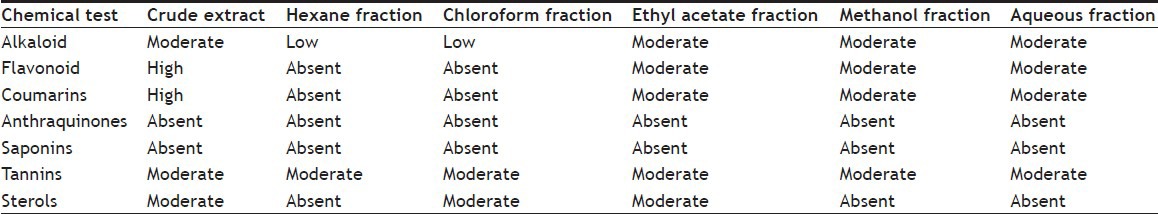

Different chemical tests were conducted for the preliminary qualitative analysis to determine the presence or absence of different phytochemicals in the crude extract and fractions. The change in intensity of the reaction mixture colour or turbidity/precipitation was visually observed to define the absence, low, moderate or high concentrations of phytoconstituents according to the standard protocol as described by Bibi et al.[13].

All the tests were performed in triplicate as independent experiments. The data obtained from cytotoxic activity of fractions were further analysed for ANOVA and LSD test at P<.05 using MSTATC to determine the significance of percentage inhibition values between the extracts.

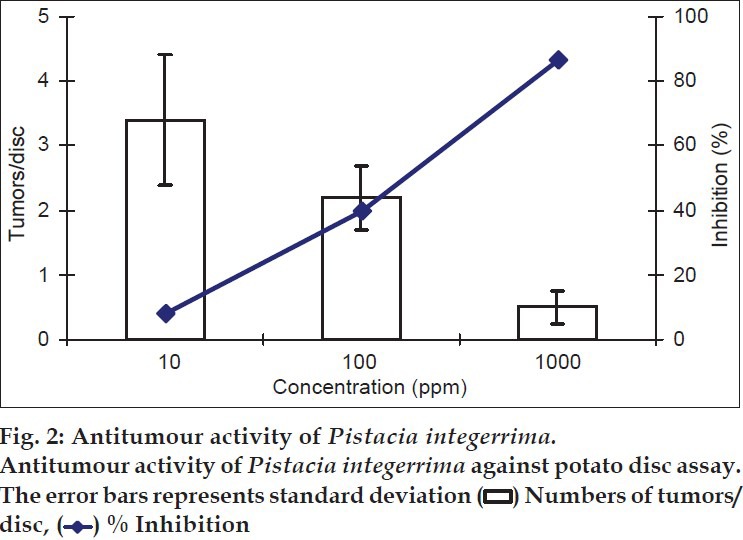

The crude methanol extract of Pistacia integerrima showed moderate cytotoxic, good antitumour and weak antifungal activities, whereas fractions exhibited varying cytotoxic activity against human breast cancer MCF-7 cell line. The crude extract exhibited tumour inhibition on potato discs in a dose-dependent manner. The minimum inhibition (8.1%) with average number of tumours 3.4 was observed at a concentration of 10 ppm. At 100 ppm, 40% tumour inhibition was observed with average number of tumours 2.2 whereas 86.4% inhibition was calculated at 1000 ppm, where average number of tumours was 0.5 per disc (fig. 2). The theoretically calculated IC50 was ~125 ppm. The tumorigenesis occurs in the living systems both in animal and plants[14]. The tumour inhibition on potato discs through methanol extract envisages the potential of P. integerrima against cancer cell lines.

Fig. 2.

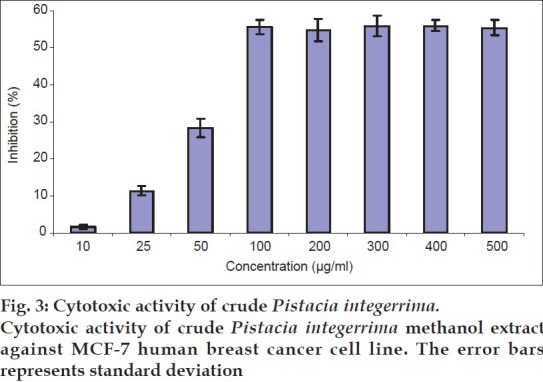

Anticancer potential was further confirmed by subjecting the crude extract of P. integerrima against MCF-7 cell line. The crude extract of P. integerrima showed moderate cytotoxicity in a dose-dependent manner up to 100 μg/ml concentration with a maximum inhibition of 55.4±2% at this concentration (fig. 3). At much higher concentrations (100 to 500 μg/ml), cytotoxicity of P. integerrima crude extract against MCF-7 cell line was static. The dose-dependent activity of extracts has also been reported in Sandoricum koetjape (Meliaceae)[15], Tinospora cordifolia (Menispermaceae)[16] and Aspidosperma tomentosum (Apocynaceae)[17]. The theoretically calculated IC50 value was ~90.9 μg/ml.

Fig. 3.

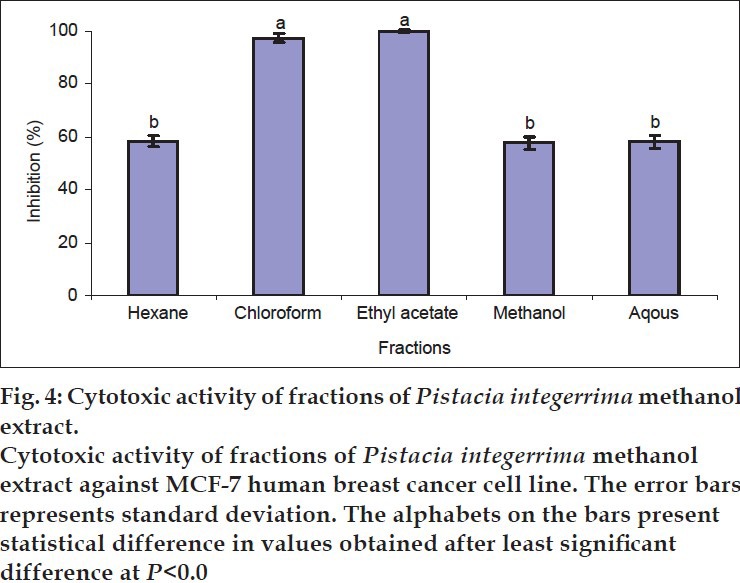

The crude extract was fractionated, and the fractions at a concentration of 200 μg/ml were also tested against MCF-7 cell line. The highest inhibition (100%) was calculated in ethyl acetate fraction followed by chloroform fraction (97.4±1.5%). The other three fractions showed moderate activity. Hexane fraction demonstrated 58.2±2% activity whereas methanol and aqueous fraction showed almost equal activities 57.6 and 58.1%, respectively (fig. 4). Similar results were also found in studies on bioactivities of Nephelium longan where all fractions proved active, whereas maximum cytotoxic activity was shown by ethyl acetate and chloroform fractions[18]. The ethyl acetate fraction of Bacopa monnieri extract was also found more potent among other tested extracts[19]. These results also proved that the fractions of P. integerrima are remarkably more active compared to its crude extract. Similarly fractions of Vitex negundo (Lamiaceae) were also found more cytotoxic in comparison with crude extract of that plant[20].

Fig. 4.

The lack of activity in crude extract compared to its fractions has already been reported. The low activity of the crude extracts might be due to presence of compounds which antagonise active components[21]. The antagonistic interactions may exist in the crude extract as well as its fractions making their activities weak[22]. The different components of a class might have different activity, which can exert synergistic or antagonistic effects within themselves or on other class of compounds[23–25]. The varying level of activity in polar and non-polar fractions (fig. 4) might be due to the presence of different active components. The maximum activity in the two fractions (ethyl acetate and chloroform) can serve as guideline for the further isolation of bioactive components. Fractionation is an advantage to separate highly active fractions for further isolation studies[26].

In the case of antifungal assay, the extract did not show any activity against Mucor and Fusarium moliniforme. However, the extract was moderately active against Aspergillus fumigatus showing 40% inhibition (with reference to negative control). Our results contradict previous findings on stem extract of P. integerrima, where antifungal activity was tested by agar well diffusion method and it showed strong inhibition against other fungal strains, i.e., Aspergillus niger, Alternaria alternate, Fusarium chlamydosporum, Rhizoctonia bataticola[27].

Preliminary phytochemical analysis showed the presence of alkaloids, flavonoids, coumarins, sterols and tannins in the crude extract (Table 1). The alkaloids were present in all fractions up to varying degrees. The flavonoids and coumarins appeared in the ethyl acetate, methanol and also in aqueous fractions, whereas they were absent in hexane and chloroform fractions. The anthraquinones and saponins were absent in all fractions as were in crude extract. Tannins were present in all fractions equally. These phytochemicals might be responsible for the activities of the crude extract. The distribution of these phytochemicals in different fractions might be responsible for varying activity either due to synergistic or antagonistic effects.

TABLE 1.

QUALITATIVE PHYTOCHEMICAL ANALYSIS OF CRUDE EXTRACT AND FRACTIONS OF PISTACIA INTEGERRIMA

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that the preliminary fractionation of even moderately active crude extracts is helpful for the isolation of active components. On the basis of these findings, we envision that the chloroform and ethyl acetate fractions of P. integerrima would be good candidates to explore more biological studies, and for investigation of novel bioactive components and their application in pharmaceutical purposes.

Footnotes

Bibi, et al.: Biological Activities of Pistacia integerrima

REFERENCES

- 1.Mukherjee AK, Basu S, Sarkar N, Ghosh AC. Advances in cancer therapy with plant based natural products. Curr Med Chem. 2001;8:1467–86. doi: 10.2174/0929867013372094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ueda JY, Tezuka Y, Banskota AH, Le Tran Q, Tran QK, Harimaya Y, et al. Antiproliferative activity of Vietnamese medicinal plants. Biol Pharm Bull. 2002;25:753–60. doi: 10.1248/bpb.25.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harvey AL. Medicines from nature. Are natural products still relevant to drug discovery? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1999;20:196–8. doi: 10.1016/s0165-6147(99)01346-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perdue RE, Smith RL, Wall ME, Hartwell JL, Abbott BJ. Camptotheca acuminata Decaisne [Nyssaceae] source of camptothecin, an antileukemia alkaloid. USDA Tech Bull. 1970;1415:26. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Main A, Khan MA, Ashraf M, Qureshi RA. Traditional use of herbs, shurbs and trees of Shogran valley, Mansehra, Pakistan. Pak J Biol Sci. 2001;4:1101–7. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chopra RN, Nayar SL, Chopra IC. Glossary of Indian Medicinal Plants (Including the Supplement) New Delhi: Council of Scientific and Indust Res; 1986. pp. 79–81. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Khan MA, Malik SA, Shad AA, Shafi M, Bakht J. Hepatocurative potentials of Pistacia integerrima in CCl4-treated rats. Sarhad J Agri (Pak) 2004;20:279–85. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ansari SH, Ali M. Analgesic and antiinflammatory activity of tetracyclic triterpenoids isolated from Pistacia integerrima galls. Fitoterapia. 1996;67:103–5. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmad NS, Farman M, Najmi MH, Mian KB, Hasan A. Activity of polyphenolic plant extracts as scavengers of free radicals and inhibitors of xanthine oxidase. J Basic Appl Sci. 2006;2:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ahmad NS, Farman M, Najmi MH, Mian KB, Hasan A. Pharmacological basis for use of Pistacia integerrima leaves in hyperuricemia and gout. J Ethnopharmacol. 2008;117:478–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2008.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fatima N, Zia M, Rehman UR, Rizvi ZF, Ahmad S, Mirza B, et al. Biological activities of Rumex dentatus L.: Evaluation of methanol and hexane extracts. Afr J Biotechnol. 2009;8:6545–51. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bibi Y, Nisa S, Waheed A, Zia M, Sarwar S, Ahmed S, et al. Evaluation of Viburnum foetens for anticancer and antibacterial potential and phytochemical analysis. Afr J Biotechnol. 2010;9:5611–5. [Google Scholar]

- 14.McLaughlin JL. Crown gall tumors on potato discs and brine shrimp lethality: Two single bioassays for plant screening and fraction. In: Hostetsmann K, editor. Methods in Plant Biochemistry. London: London Academic Press; 1991. pp. 1–31. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aisha AF, Sahib HB, Abu-Salah KM, Darwis Y, Abdul-Majid AM. Cytotoxic and anti-angiogenic properties of the stem bark extract of Sandoricum koetjape. Int Cancer Res. 2009;5:105–14. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jagetia GC, Rao SK. Evaluation of cytotoxic effects of dichloromethane extract of Guduchi (Tinospora cordifolia Miers ex Hook F and THOMS) on cultured HeLa cells. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2006;3:267–72. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nel011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kohn LK, Pizao PE, Foglio MA, Antonio MA, Amaral MCE, Bittric V, et al. Antiproliferative activity of crude extract and fractions obtained from Aspidosperma tomentosum. Rev Bras Pl Med. 2006;8:110–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ripa FA, Haque M, Bulbul IJ. In vitro antibacterial, cytotoxic and antioxidant activities of plant Nephelium longan. Pak J Biol Sci. 2010;13:22–7. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2010.22.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghosh T, Maity TK, Bose A, Dash GK, Das M. Antimicrobial activity of various fractions of ethanol extract of Bacopa monnieri Linn. aerial parts. Indian J Pharm Sci. 2007;69:312–4. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chowdhury JA, Islam MS, Asifuzzaman SK, Islam MK. Antibacterial and cytotoxic activity screening of leaf extracts of Vitex negundo (Fam: Verbenaceae) J Pharm Sci Res. 2009;1:103–8. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alam MA, Sarder M, Awal MA, Sikder MM, Daulla KA. Antibacterial activity of the crude ethanolic extract of Xylocarpus granatum stem barks. Bangladesh J Vet Med. 2006;4:69–72. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Okokon JE, Nwafor PA. Antimicrobial activity of root extract and crude fractions of Croton zambesicus. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2010;23:114–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rice-Evans CA, Miller NJ, Paganga G. Structure-antioxidant activity relationships of flavonoids and phenolic acids. Free Radic Biol Med. 1996;20:933–56. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(95)02227-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moran JF, Klucas RV, Grayer RJ, Abian J, Becana M. Complexes of iron with phenolic compounds from soybean nodules and other legume tissues: Prooxidant and antioxidant properties. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;22:861–70. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00426-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lien EJ, Ren S, Bui HH, Wang R. Quantitative structure-activity relationship analysis of phenolic antioxidants. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26:285–94. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(98)00190-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pisutthanan S, Plianbangchang P, Pisutthanan N, Ruanruay S, Muanrit O. Brine shrimp lethality activity of Thai medicinal plants in the family Meliaceae. Naresuan Univ J. 2009;12:13–8. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Farrukh A, Iqbal A. Broad spectrum antibacterial and antifungal activities of certain traditionally used Indian medicinal plants. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;19:653–7. [Google Scholar]