Abstract

Lateral inhibition produces the centre-surround organization of retinal receptive fields, in which inhibition driven by the mean luminance enhances the sensitivity of ganglion cells to spatial and temporal contrast. Surround inhibition is generated in both synaptic layers; however, the synaptic mechanisms within the inner plexiform layer are not well characterized within specific classes of retinal ganglion cell. Here, we compared the synaptic circuits generating concentric centre-surround receptive fields in ON and OFF brisk-sustained ganglion cells (BSGCs) in the rabbit retina. We first characterized the synaptic inputs to the centre of ON BSGCs, for comparison with previous results from OFF BSGCs. Similar to wide-field ganglion cells, the spatial extent of the excitatory centre and inhibitory surround was larger for the ON than the OFF BSGCs. The results indicate that the surrounds of ON and OFF BSGCs are generated in both the outer and the inner plexiform layers. The inner plexiform layer surround inhibition comprised GABAergic suppression of excitatory inputs from bipolar cells. However, ON and OFF BSGCs displayed notable differences. Surround suppression of excitatory inputs was weaker in ON than OFF BSGCs, and was mediated largely by GABAC receptors in ON BSGCs, and by both GABAA and GABAC receptors in OFF BSGCs. Large ON pathway-mediated glycinergic inputs to ON and OFF BSGCs also showed surround suppression, while much smaller GABAergic inputs showed weak, if any, spatial tuning. Unlike OFF BSGCs, which receive strong glycinergic crossover inhibition from the ON pathway, the ON BSGCs do not receive crossover inhibition from the OFF pathway. We compare and discuss possible roles for glycinergic inhibition in the two cell types.

Key points

ON and OFF cells in the retina are excited by increases and decreases in visual contrast, respectively. ON and OFF brisk-sustained ganglion cells (BSGCs) have antagonistic ‘centre-surround’ receptive fields; a visual stimulus that excites the centre is inhibitory in the surround. Such lateral inhibition enhances sensitivity to contrast borders.

This study provides the first detailed comparison of visually evoked, excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs driving the centres and surrounds of ON and OFF BSGCs.

GABAergic lateral inhibition suppresses excitatory inputs to BSGCs presynaptically, via GABAC receptors at ON BSGCS and GABAA and GABAC receptors at OFF BSGCs. Feed-forward glycinergic inhibition, driven through the ON pathway, contributes to centre but not surround responses in both cell types.

Centre excitation is mediated by AMPA receptors in ON BSGCs, and NMDA and AMPA receptors in OFF BSGCs.

The results reveal mechanistic differences in homologous neural circuits that perform a similar neural computation in the visual system.

Introduction

Lateral inhibition is a ubiquitous feature of the CNS. In the retina, where the basic neural circuitry is well delineated, one role of lateral inhibition is to produce the antagonistic centre-surround receptive field organization seen in many retinal ganglion cells (Kuffler, 1953). The surround suppresses mean luminance signals and enhances sensitivity to local contrast (Kuffler, 1953; Rodieck & Stone, 1965; Enroth-Cugell & Robson, 1966; Srinivasan et al. 1982; Lipin et al. 2010). Suppression of the centre responses of ganglion cells, by stimulation of the receptive field surround, is generated both by horizontal cells at the first synapse between the photoreceptors and bipolar cells in the outer plexiform layer (OPL; Mangel, 1991; Lankheet et al. 1992; Dacey et al. 2000; Kamermans et al. 2001; McMahon et al. 2004; Ichinose & Lukasiewicz, 2005), and by inhibitory amacrine cells in the second synaptic layer, the inner plexiform layer (IPL; Thibos & Werblin, 1978; Cook & McReynolds, 1998; Demb et al. 1999; Taylor, 1999; Roska et al. 2000; Flores-Herr et al. 2001; Zaghloul et al. 2007; Passaglia et al. 2009).

In the mammalian retina wide-field amacrine cells are GABAergic (Pourcho & Goebel, 1983), and are presumed to mediate IPL lateral inhibition, while the functional roles of glycinergic amacrine cells, which tend to be narrow-field cells (Menger et al. 1998), are less well understood. Wide-field GABAergic amacrine cells are thought to generate complex receptive field properties, which display strong spatial or spatiotemporal asymmetries, such as orientation selectivity and direction selectivity (Barlow & Levick, 1965; Caldwell et al. 1978; Taylor & Vaney, 2002; Venkataramani & Taylor, 2010). In contrast, the symmetric connectivity between horizontal cells and photoreceptors in the OPL would appear sufficient to generate surround inhibition in concentric centre-surround cells, such as the X and Y cells in cat (Boycott & Wässle, 1974), the brisk-sustained and brisk-transient cells in rabbit (Vaney et al. 1981), and the midget and parasol cells in primate (de Monasterio, 1978). Indeed, the surround of parasol cells appears to be accounted for by OPL mechanisms (McMahon et al. 2004). However, for specific types of concentric ganglion cells in the rabbit retina, blocking GABA receptors decreases the strength of surround antagonism, suggesting a symmetric IPL contribution (Caldwell & Daw, 1978b). The mechanisms by which specific amacrine cells contribute to the receptive field structure of various types of concentric ganglion cells remain largely unknown.

Inner plexiform surrounds may be generated presynaptically, by feedback inhibition onto bipolar cell terminals (Matsui et al. 2001), or postsynaptically, by feed-forward inhibition directly onto the ganglion cell dendrites (Flores-Herr et al. 2001). Transient ON–OFF ganglion cells in the rabbit retina have been shown to receive GABAergic inputs that increase with stimulus size (Sivyer et al. 2011), consistent with postsynaptic surround inhibition. By contrast, in sluggishly responding local edge detectors, which are also ON–OFF ganglion cells, both excitation and inhibition are suppressed by large stimuli, consistent with a primarily presynaptic surround mechanism (van Wyk et al. 2006; Russell & Werblin, 2010). Interestingly, both transient ON–OFF ganglion cells and local edge detectors had different surround dimensions for ON and OFF spike responses.

To examine further the synaptic basis for differences in surround antagonism between the ON and OFF pathways, we studied the centre-surround antagonism of synaptic inputs in homologous ON and OFF brisk-sustained ganglion cells (BSGCs) in the rabbit retina (Caldwell & Daw, 1978a; Vaney et al. 1981; Amthor et al. 1989; Devries & Baylor, 1997). These concentric centre-surround cells are similar to ON and OFF X cells in the cat, and the ON and OFF midget cells in the primate in that they comprise a high spatial frequency pathway for visual signals (Enroth-Cugell & Robson, 1966; Cleland et al. 1971; Boycott & Wässle, 1974; Hochstein & Shapley, 1976; Shapley & Victor, 1978; de Monasterio, 1978; Vaney et al. 1981; Troy, 1983). Recent evidence has shown that the receptive field properties of homologous ON and OFF ganglion cells in primate, guinea pig and mouse retinas are not functionally mirror symmetric (Chichilnisky & Kalmar, 2002; Zaghloul et al. 2003; Sagdullaev et al. 2006; Pandarinath et al. 2010), but can display marked differences. The synaptic mechanisms and functional implications of these differences require further investigation. Therefore, in addition to exploring the synaptic basis for surround antagonism in ON and OFF BSGCs, we have analysed inhibitory synaptic mechanisms contributing to the centre inputs to the ON-BSGCs for comparison with results obtained previously in the homologous OFF-BSGCs (Buldyrev et al. 2012).

Methods

Ethical approval

Procedures involving animals were performed in accordance with National Institute of Health guidelines and with approval from the Oregon Health & Science University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Tissue preparation and maintenance

Pigmented rabbits aged 5 weeks and older were dark adapted for at least 1 h before sedation by intramuscular injection of ketamine (50 mg kg−1) and xylazine (10 mg kg−1), followed by surgical anaesthesia using intravenous sodium pentobarbital (40 mg kg−1). After the eyes were removed, the animal was killed via an injection of sodium pentobarbital (100 mg kg−1) and potassium chloride (10 ml, 1 m). A central portion of the inferior retina was excised, placed photoreceptor side down in a glass-bottomed recording chamber and held down by a platinum–iridium wire harp with nylon strings. The recording chamber was continuously perfused at a rate of 5 mL min−1 with bicarbonate buffered, pH 7.4, Ames medium (US Biological, Swampscott, MA, USA), equilibrated with a mixture of 95% O2 and 5% CO2 and maintained at 36–37°C. All manipulations were carried out under dim red illumination.

Electrophysiology and BSGC identification

Ganglion cell somas within ∼2 mm of the visual streak were targeted for extracellular recordings based on their small size (≤15 μm in diameter). The ganglion cells were visualized through a 40× 0.75NA water immersion objective, using a video camera mounted on an upright Olympus BX-51 microscope with infrared (900 nm) differential interference contrast optics. BSGCs were physiologically identified from extracellular spike recordings made with borosilicate patch electrodes of 4–6 MΩ resistance, and filled with the extracellular medium. In some experiments 0.4% Alexa-594 hydrazide or 0.4% Alexa-488 hydrazide (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was included in the intracellular recording solution to visualize cell morphology, and anatomically identify the cells at the conclusion of patch-clamp recording.

For voltage-clamp recordings, the intracellular solution contained (in mm): 128 Cs-methylsulfonate, 6 CsCl, 10 Na-Hepes, 1 EGTA, 2 Mg-ATP, 1 Na2-GTP, 2.5 Na2 phosphocreatine and 3 QX-314 (lidocaine-N-ethyl-Cl). Unless otherwise noted reagents were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St Louis, MO, USA). The QX-314 was included to block spikes generated by voltage-gated sodium channels. Recordings were performed using a Multiclamp 700A patch-clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Signals were digitized at 5 kHz, and filtered at 2 kHz through the 4-pole Bessel filter in the amplifier. Currents were further digitally filtered during off-line analysis with a –3 dB corner frequency of 100 Hz.

Holding potentials were corrected for a −13 mV liquid junction potential. Up to 70% of the series resistance error was compensated for online. The average series resistance for OFF BSGCs was 22 ± 6 MΩ and for ON BSGCs was 21 ± 7 MΩ (mean ± SD), and the resting input resistance measured over the linear range (−100 mV to ∼−30 mV) was 323 ± 25 MΩ for OFF and 311 ± 21 MΩ for ON. Additionally, voltages were corrected for uncompensated series resistance off-line as detailed previously (Venkataramani & Taylor, 2010). The dendritic arbours of BSGCs are small, and are expected to be electrically compact; therefore, with application of on-line and off-line compensation, series resistance errors should not have a significant impact on the accuracy of our conductance estimates.

Bath-applied drugs included SR95531 (6-imino-3-(4-methoxyphenyl)-1(6H)-pyridazinebutanoic acid hydrobromide; 25 μm), l-(+)-2-amino-4-phosphonobutyric acid (l-AP4; 50 μm; Abcam Biochemicals, Cambridge, MA, USA), TPMPA (1,2,5,6-tetrahydropyridin-4-yl) methylphosphinic acid; 100 μm), strychnine (1 μm) and the pH buffer Hepes. The pH of both the Hepes-containing and the control Ames solutions was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH. In experiments where NMDA (Tocris, Ellisville, MO, USA) was puffed onto the ganglion cell, synaptic transmission was blocked with 100 μm CdCl2 and a standard patch electrode was filled with 2 mm NMDA dissolved in Ames medium and positioned above a hole in the inner limiting membrane approximately 30 μm from the cell body. Puffs, 100 ms in duration, were generated using a Picospritzer microinjector (Parker Hannifin, Cleveland, OH, USA).

Conductance analysis

Stimulus-activated synaptic conductance was measured from current–voltage (I–V) relations obtained over a range of holding potentials between –98 and +27 mV. I–V relations were measured at 10 ms intervals to determine the time course of the synaptic conductances. At each time point, the membrane potential was corrected for uncompensated series resistance errors, using the whole-cell current, and the series resistance value was estimated just prior to the stimulus run. The net light-activated synaptic I–V relation was obtained by subtracting the mean current during the 200 ms prior to stimulus onset from the current during the light response. At positive potentials, the intracellular currents appeared insufficient to completely suppress outward rectification, and during the voltage steps the currents often displayed a slow sag. This sloping baseline was subtracted from the records at positive potentials to obviate errors in measuring the amplitudes of the net light-activated synaptic currents.

Synaptic inputs comprised excitation, with a reversal potential VE = 0 mV, and inhibition, with a reversal potential at the chloride equilibrium potential, ECl, which was calculated as −68 mV under our conditions. In addition to these two linear, voltage-independent conductances, part of the excitatory input to BSGCs was mediated by NMDA receptors, which have a non-linear I–V relation due to voltage-dependent channel block by extracellular Mg2+ ions. Analysis of the NMDA component of the synaptic conductance was performed as described previously (Manookin et al. 2010; Venkataramani & Taylor, 2010; Buldyrev et al. 2012). The magnitude of the NMDA component was scaled by a factor of 0.28 to reflect the proportion of available channels close to the typical resting membrane potential of −60 mV.

Light stimulation and analysis of receptive field dimensions

The procedures for light stimulation have been described previously (Venkataramani & Taylor, 2010; Buldyrev et al. 2012). The standard stimulus comprised a circular spot centred on the receptive field and square-wave modulated at 1 Hz on a steady background of approximately 3 × 103 photons s−1 μm−2 at the retina, which is in the photopic range. Contrast was defined as C = 100(Lmax − Lmin)/(Lmax + Lmin), where Lmax and Lmin are the maximum and minimum intensities of the spot. Receptive field sizes were estimated from area–response functions (diameters were 25–1000 μm) obtained at a contrast of 20%, which elicited strong but sub-saturating responses in both ON and OFF BSGCs (see Fig. 5; Buldyrev et al. 2012, Fig. 4). To avoid the effects of adaptation, stimuli were presented at 6 s intervals and the order of stimulus diameters was interleaved. Additionally, for each condition (control or drug), there were at least two trials with a different order of stimulus diameters. The dimensions and relative amplitudes of the excitatory centre and inhibitory surround of the receptive field were estimated by fitting a difference of Gaussian (DOG) integrals to the area–response functions (Rodieck, 1965). In ON and OFF BSGCs, this simple linear model provided a good empirical fit to the area–response functions generated from peri-stimulus spike-time histograms (Fig. 1E and F). The area–response curve was fitted to the equation

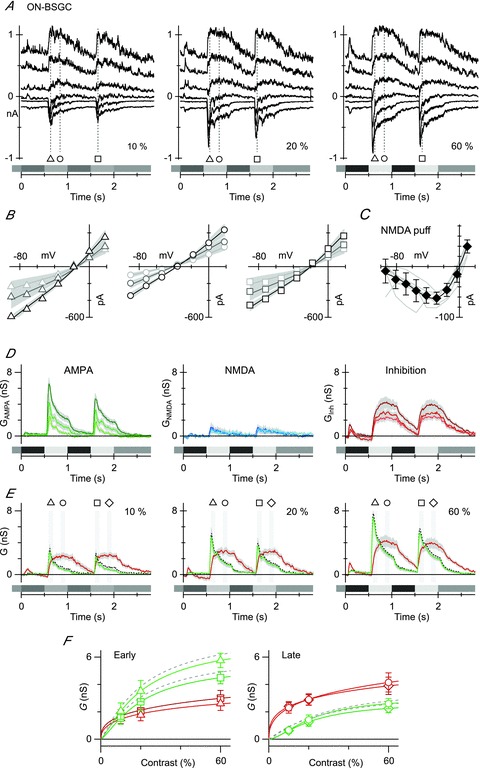

Figure 5. Contrast dependence of light-evoked synaptic inputs to ON BSGCs.

A, currents recorded from an ON BSGC held at six potentials at 25 mV intervals between –98 and +27 mV. The stimulus was a 125 μm-diameter spot, square-wave modulated at 1 Hz. The contrast is shown at the bottom right of each panel. Markers show the time points for the I–V relations shown in B. B, the symbols show the light-evoked, series resistance-corrected I–V relation averaged from individual I–V relations in nine ON cells. The fits, shown by the continuous lines, represent the average of the fits to the individual cells. The shaded regions show the SEM for the fits across the group of cells. C, leak-subtracted I–V curves of individual responses to pressure ejection of 2 mm NMDA onto seven ON BSGCs (light grey lines). Individual I–V curves have been normalized to the average slope conductance for the dataset calculated for the most positive three data points. The diamonds show the mean ± SD. The continuous line shows the fit to the mean data of the function describing the voltage dependence of NMDA receptor conductance. D, conductance components calculated every 10 ms for the duration of the light stimulus (see Methods). The shaded regions show the SEM. The linear AMPA conductance (GAMPA) is shown in green, the NMDA conductance (GNMDA) is shown in blue and the inhibitory conductance (Gi) is shown in red, here and in all subsequent figures. The darkest lines indicate the highest contrast. E, average conductance components calculated for the same data as D, except green traces represent the total excitatory conductance as determined from a linear fit to the I–V curves. The dashed grey line shows the average excitatory conductance from a sum of the AMPA and NMDA conductances from D. Note that it falls within the SEM (grey shading) of the conductance generated via linear fits. F, the average amplitude of the excitatory and inhibitory conductance components measured as a function of stimulus contrast at the time points shown in E. The smooth lines show empirical fits to the data. At the early time point, inhibition saturated at a lower contrast than excitation and was smaller (left panel), while at the late time point inhibition was larger than excitation, but still saturated at a lower contrast (right panel).

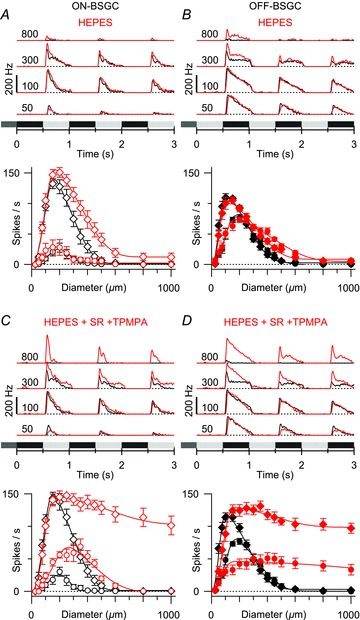

Figure 4. Effect of Hepes on BSGC RF properties.

Average peri-stimulus time histograms (top) and mean spike rates plotted against stimulus diameter (bottom). Black shows control data, and red shows data in the presence of 20 mm Hepes. A, mean responses from five ON BSGCs and five OFF BSGCs showing that 20 mm Hepes has a small effect on the surround, but did not significantly reduce SI. C and D, responses in 20 mm Hepes with 25 μm SR95531 and 100 μm TPMPA. The addition of Hepes reduced the SI below that seen with SR95531 and TPMPA alone (compare with Figs 2 and 3). (DOG fits to the mean data for the early phase in Hepes: ON, 2σinh = 1004 μm, SI = 93%; OFF, 2σinh = 914 μm, SI = 92%; Hepes + SR95531 + TPMPA: ON, 2σinh = 1556 μm, SI = 31%; OFF, 2σinh = 1284 μm, SI = 25%.)

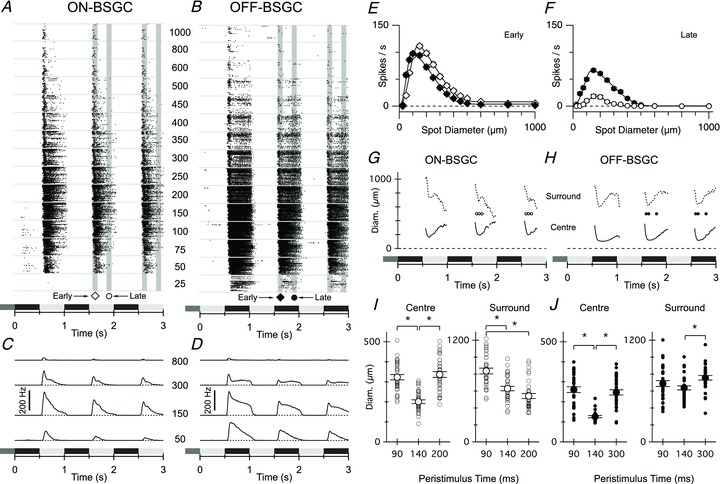

Figure 1. Spatiotemporal properties of ON and OFF BSGC receptive fields.

A and B, spike raster plots of responses from each of the 33 ON BSGCs (A) and 32 OFF BSGCs (B) during stimulation with a centred spot, square-wave modulated at 1 Hz. Stimulus timing and contrast is indicated by the shaded rectangles beneath the records in A–F, and in all subsequent figures. Each row of dots within the bins delineated by the horizontal grey lines represents a train of action potentials recorded from a single BSGC. The stimulus spot diameters (μm) are indicated by the centre column of numbers. The shaded vertical bars delineate the 100 ms time periods over which the spike rate was averaged for quantification in this and subsequent figures (early, diamond, centred on the time of peak firing for the 150 and 200 μm spots (∼120 ms delay), and late, circle, centred at a 400 ms delay). C and D, average peri-stimulus spike-time histograms for ON (C) and OFF (D) BSGCs measured at the spot diameters indicated. Note that the ON BSGCs are relatively more transient and less sensitive for the smallest diameter spot. E and F, mean spike rate versus stimulus diameter measured at the time points indicated in A and B. Continuous lines show DOG integral fits to the data. The rightward shift in the ON data shows that the centre size for the ON BSGCs (centre diameter = 228 ± 6 μm) was ∼1.5-fold larger than the OFF BSGCs (centre diameter = 156 ± 5 μm). The ON surround diameter (776 ± 26 μm) was ∼1.1-fold larger than the OFF (703 ± 22 μm). G and H, the time course of the centre (continuous line) and surround (dashed line) diameters calculated from DOG fits to the spike-time histograms at 10 ms intervals as described in the Methods. Centre space constants of both ON and OFF BSGC reach minimum values with a latency of ∼120–150 ms, corresponding with the time at which responses to the smallest spots were first observed. I and J, the centre and surround diameters of individual cells calculated from DOG fits to their area–response curves are shown at the three 10 ms time intervals during the response (corresponding to symbols in G and H). Significant changes in diameters are marked by asterisks (P < 0.05).

where R is the spike rate evoked by a stimulus of diameter s, Kexc and Kinh are the amplitudes of the excitatory and inhibitory Gaussians, respectively, and σexc and σinh are their space constants. Diameters of the receptive field centres and surrounds are quoted as 2σexc and 2σinh, which accounts for 95% of the modelled receptive field areas for the two components. To quantify the strength of surround suppression, we used a suppression index (SI), which was calculated as a ratio of the excitatory and inhibitory Gaussian areas (Sceniak et al. 1999):

To determine the strength of surround suppression of synaptic conductances where responses to only three spot sizes (100, 300 and 900 μm) were sampled, we used the ratio of the conductances evoked by the 900 μm (G900) and 100 μm (G100) stimuli:

For both spike rates and conductances, complete suppression of the centre response is achieved as SI approaches 100%.

Statistical analysis

Conductance analysis was performed on current traces from individual cells. Mean conductances for groups of cells are shown with shading designating the standard error of the mean (SEM). Unless otherwise noted, error bars in the figures show SEM. Mann–Whitney U tests were used to assess the statistical significance of drug effects on the SI of BSGC spike output and paired Student's t tests were used for experiments with conductances, where surround suppression was not complete. To determine the statistical significance of changes in receptive field size over time, a repeated-measures ANOVA with a Tukey post hoc test was used. An alpha level of 0.05 was used for all statistical tests. Analysis and statistical tests were performed using Igor Pro (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR, USA).

Results

ON BSGCs have larger receptive fields and more transient responses than OFF BSGCs

To investigate the role of GABAergic circuits in shaping the spatial dimensions of ON and OFF BSGC receptive fields, we first estimated the centre and surround sizes from the effect of stimulus size on spike output. Spikes were measured in response to contrast-reversing spots with a peak-to-peak amplitude of 20% relative to a photopic background over a range of spot diameters (Fig. 1A and B). To obviate non-linearities due to saturation of spiking, we analysed responses only during the second and third stimulus cycles, for which spiking never approached maximum rates (∼250–300 Hz for OFF and ∼300–350 Hz for ON BSGCs), probably due to adaptation seen in the excitatory inputs (see below). Notably, however, the overall spatio-temporal profile of spike responses was similar between the first and subsequent stimulus cycles as evident from the average peristimulus spike-time histograms shown in Fig. 1C and D. ON BSGCs were more transient than OFF BSGCs (Fig. 1A–D). The peak firing rate for optimal spot sizes, measured at an early time point during the second and third stimulus cycles, was 12.8% higher for ON BSGCs (contrast 20%, Fig. 1E: 114 ± 3 Hz ON, n = 33, vs. 101 ± 3 Hz, OFF, n = 32, P = 0.008). This relationship was inverted late in the stimulus cycles, with the average firing rate becoming 2.2-fold higher for OFF cells (Fig. 1F: 22 ± 3 Hz ON vs. 70 ± 3 Hz, OFF, P < 0.0001).

Receptive fields of ON and OFF BSGCs were well described by a symmetric DOG function (see Methods) that assumes a concentric, centre-surround organization; however, estimates of the centre and surround sizes can depend on the measurement time relative to stimulus onset (Ruksenas et al. 2007). This was evident in ON and OFF BSGCs, where the centre size was initially larger, but contracted significantly, and passed through a minimal size ∼120–150 ms after stimulus onset (Fig. 1G and H continuous lines; Fig. 1I and J, centre diameter for ON BSGCs was 323 ± 13 μm at 90 ms peristimulus vs. 202 ± 10 μm at 140 ms; and for OFF cells it was 262 ± 12 μm at 90 ms vs. 126 ± 11 μm at 140 ms). Similarly, the extent of the surround became significantly smaller in ON cells after the onset of the response (Fig. 1I and J, 837 ± 34 μm at 90 ms, 630 ± 26 μm at 140 ms, and 542 ± 30 μm at 200 ms, repeated-measures ANOVA, P < 0.05), and for the OFF BSGCs passed through a clear minimum with a comparable delay, significantly increasing at later time points (dotted lines, Fig. 1H; Fig. 1J, 638 ± 24 μm at 140 ms vs. 757 ± 27 μm at 300 ms). The time at which the minimal receptive field size was reached corresponded, within ∼10 ms, to the peak of the spike discharge for both ON and OFF BSGCs. Therefore, to compare the spatial properties of ON and OFF BSGC receptive fields, spike rate measurements in individual BSGCs were centred on the time of peak firing (determined from responses to optimal spot sizes) and averaged over 100 ms (shaded areas Fig. 1A and B). The resulting average centre sizes were 46% larger for ON BSGCs (228 ± 6 μm, n = 33, Fig. 1E) than for the OFF BSGCs (156 ± 5 μm, n = 32; P < 0.0001). Similarly, the surround diameters were 10.4% broader for the ON cells than for the OFF (776 ± 26 μm ON vs. 703 ± 22 μm OFF; P = 0.03). The surround suppression index (SI), expressed as a percentage, was calculated from the ratio of the integrals of the inhibitory and excitatory Gaussians (see Methods). An SI close to 100% represents complete suppression of spiking for the largest stimuli, while 0% would indicate a complete lack of surround suppression. At the peak of the responses, the SI was 94 ± 1% for the ON cells and 98 ± 1% for OFF cells (Fig. 1E, P = 0.03 Mann–Whitney U test). At later times during the stimulus, surround suppression was complete in both cell types, as the spiking responses became more transient for larger stimuli (Fig. 1F).

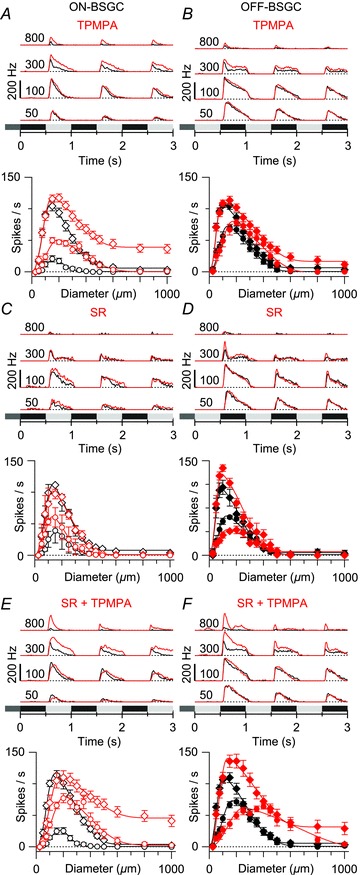

Surround inhibition is mediated by GABAC receptors in ON BSGCs and GABAA and GABAC receptors in OFF BSGCs

GABAA and GABAC receptors are activated by lateral inputs from amacrine cells and can modulate transmitter release from cone bipolar cells (Matsui et al. 2001; Freed et al. 2003; Demas et al. 2006; Sagdullaev et al. 2006; Eggers et al. 2007). In the mammalian retina, GABAA and GABAC receptors are found throughout the IPL, and are localized synaptically at bipolar cell axon terminals (Wässle et al. 1998; Shields et al. 2000), and to the dendrites of ganglion cells (Rotolo & Dacheux, 2003). Different bipolar cell subtypes have been shown to differ in the proportions of GABAA and GABAC receptor input, with OFF bipolar cells having a larger GABAA component (Shields et al. 2000; Zhou & Dacheux, 2005; Sagdullaev et al. 2006). Although data indicate that GABAergic mechanisms in the IPL mediate spatial tuning in some ganglion cells (Cook & McReynolds, 1998; Taylor, 1999; Flores-Herr et al. 2001), the sub-types of GABA receptors involved are largely unknown. To address this issue, we used selective GABA receptor antagonists to investigate the roles of GABAA and GABAC receptors in generating surround inhibition in BSGCs.

The GABAC antagonist TPMPA decreased the SI of the peak centre response in ON BSGCs by 25% from 95 ± 2 to 70 ± 5% (Fig. 2A, n = 9, P = 0.004), while in OFF BSGCs TPMPA had a smaller but still significant effect (Fig. 2B, 9% decrease, n = 8, control, SI = 95 ± 1%; TPMPA, SI = 86 ± 4%, P = 0.008). In contrast to TPMPA, the GABAA antagonist SR95531 had no significant effect on the SI in either OFF or ON BSGCs (Fig. 2C and D OFF, n = 3, control, SI = 96 ± 4%; SR, SI = 97 ± 1%, P = 1.25; ON, n = 3, control, SI = 94 ± 1%; SR, SI = 99 ± 1%, P = 0.25), suggesting that GABAA receptors do not contribute to surround antagonism. Consequently, if GABAC receptors mediate the entire GABAergic surround suppression in the IPL, blocking GABAC receptors should reveal the surround suppression mediated by the non-GABAergic mechanisms in the OPL that are common to both ON and OFF bipolar cells, and therefore should be of similar strength and spatial extent. However, in the presence of TPMPA, the surround in OFF BSGCs was clearly stronger than in the ON BSGCs (compare Fig. 2A and B). To rule out any possible role for GABAergic transmission in generating the surrounds of OFF BSGCs, we blocked both GABAA and GABAC receptors. Complete GABAergic block decreased the SI in OFF BSGCs by 17% from 97 ± 1.5 to 80 ± 6% (Fig. 2F, n = 7, P = 0.03), which was closer to that seen in ON BSGCs, either with GABAC block alone (Fig. 2A) or with both GABAC and GABAA antagonists (Fig. 2E, 31% decrease, control SI = 97 ± 1%; GABAergic block SI = 66 ± 7%, n = 10, P = 0.002). In OFF cells, the effect of application of the GABAA and GABAC antagonists together, relative to the GABAC antagonist alone, was especially evident in the increased responses to the largest spots during the first stimulus cycle (Fig. 2F). However, we did not quantify the SI because peak spike rates during the first cycle approached saturation in the presence of these inhibitory blockers, which would have led to an underestimation of surround suppression.

Figure 2. Effects of GABAA and GABAC receptor antagonists on BSGC receptive field properties.

A, top: average peri-stimulus spike-time histograms (top) for the stimulus diameters indicated (μm); bottom: mean spike rates plotted against stimulus diameter at the same time points as shown in Fig. 1. Black shows control, and red shows the effect of the GABAC receptor antagonist TPMPA (100 μm) in nine ON BSGCs. The continuous lines show DOG fits to the data as in Fig. 1. All subsequent panels have the same format. B, effect of 100 μm TPMPA on the surround suppression in eight OFF BSGCs. C and D, the GABAA receptor antagonist SR95531 (25 μm) applied alone did not significantly affect surround suppression in three ON BSGCs or three OFF BSGCs. E, mean responses from ten ON BSGCs show that blocking of both GABAA and GABAC receptors did not produce additional reduction in surround suppression above that seen with GABAC block alone (DOG fits to the mean data for the early phase in TPMPA: 2σinh = 936 μm, SI = 70%; TPMPA + SR: 2σinh = 1114 μm, SI = 63%). F, mean responses from seven OFF cells show that blocking both GABAA and GABAC receptors reduced surround suppression more strongly than seen with GABAC block alone (DOG fits to the mean data for the early phase in TPMPA: 2σinh = 994 μm, SI = 86%; TPMPA + SR: 2σinh = 992 μm, SI = 80%).

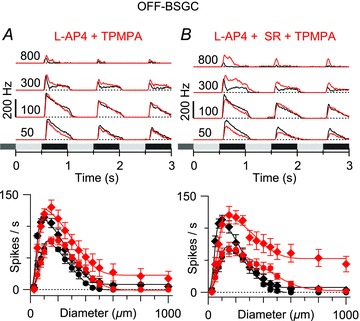

Previously, we have shown that OFF BSGCs receive crossover inhibition from the ON pathway (Buldyrev et al. 2012), and therefore we tested for possible involvement of crossover inhibition in generating the stronger surround antagonism in OFF BSGCs by blocking ON pathway transmission with l-AP4 during the application of GABA antagonists. The SI observed when blocking both the ON pathway and GABAC receptors (100 μm TPMPA + 50 μm l-AP4) was similar to that seen with GABAC block alone (Fig. 3A, n = 5, SI = 85 ± 7%, compare to Fig. 2B, TPMPA, SI = 86 ± 4%). Similarly, blocking the ON pathway, and GABAA and GABAC receptors, resulted in a decrease of 37% in SI for OFF BSGCs (Fig. 3B, control, SI = 95 ± 2%; drug treatment, SI = 58 ± 11%, n = 6, P = 0.03), an effect that was larger than, but not significantly different from, with GABAergic block alone (Fig. 2F, P = 0.06). Together, these data indicate that blocking the ON pathway does not consistently affect surround inhibition in OFF BSGCs, but that the combination of GABAA and GABAC antagonists weakens the surround antagonism in OFF BSGCs to a quantitatively similar level as seen in ON BSGCs with the GABAC antagonist alone.

Figure 3. Effect of blocking the ON pathway on OFF BSGC receptive field (RF) properties.

Average peri-stimulus time histograms (top) and mean spike rates plotted against stimulus diameter (bottom). Black shows control, and red shows the effect of drug treatment. A, mean responses from five OFF BSGCs showing the effect of 50 μm l-AP4 with 100 μm TPMPA on the area–response relation. B, mean responses from six OFF BSGCs show the effect of 50 μm l-AP4 with 25 μm SR5531 and 100 μm TPMPA on the area–response relation. Comparison with the data in Fig. 2F indicates that the effect of adding l-AP4 was not significant (P = 0.06). (DOG fits to the mean data for the early phase in l-AP4 + TPMPA: 2σinh = 882 μm, SI = 83%; l-AP4 + SR + TPMPA: 2σinh = 934 μm, SI = 60%.)

Under GABAergic block, the extents of the surrounds in ON and OFF BSGCs were similar and much broader than control (ON: 1183 ± 106 vs. 780 ± 42 μm in control, P = 0.009; OFF: 998 ± 130 vs. 700 ± 60 μm in control, P = 0.02) as predicted if the residual surround reflected the broad OPL mechanism mediated by horizontal cells that is common to all retinal neurons postsynaptic to the photoreceptors. To test whether the remaining surround antagonism was mediated by a non-GABAergic OPL mechanism, we added 20 mm Hepes to the extracellular solution, as this has been shown to block horizontal cell feedback to cone photoreceptors and suppress surround antagonism in retinal ganglion cells (Hirasawa & Kaneko, 2003; Vessey et al. 2005; Cadetti & Thoreson, 2006; Davenport et al. 2008; Fahrenfort et al. 2009). Application of 20 mm Hepes alone did not significantly decrease the SI of either ON or OFF BSGCs (Fig. 4A and B; ON, n = 5, P = 0.125; OFF, n = 5, P = 0.19), although applying Hepes in the presence of GABA antagonists decreased the SI for the early phase of the response in both ON and OFF BSGCs to significantly lower levels than achieved with GABA antagonists alone (Fig. 4C and D; ON, SI = 34 ± 7%, n = 5, OFF: SI = 27 ± 6%, n = 6. Comparing the data in Figs 4C with 2E, and 4D with 2F and 3B yielded significant differences; ON, P = 0.016; OFF, P = 0.001). These results suggest that a non-GABAergic OPL mechanism contributes to generating the surround antagonism for ON and OFF BSGCs, and combined with the IPL GABAergic inhibition can account for most of the surround suppression of the spike output for transient responses. There was a notable difference between ON and OFF BSGCs in the SI measured at the late time point of the response. During application of Hepes and the GABAergic antagonists, the SI derived from fitting the DOG function to the mean of the responses was reduced to 23% in OFF BSGCs but remained at 100% for ON BSGCs (Fig. 4C and D). The reasons for this difference are unclear but are discussed further below.

This analysis of spiking responses has suggested differences in circuitry within the IPL that drives surround inhibition in the ON and OFF BSGCs. In the next series of experiments we investigated the synaptic basis for these differences by measuring the light-evoked inhibitory and excitatory synaptic inputs to BSGCs. Previously we have demonstrated that the synaptic input generating the centre responses of OFF BSGCs is mediated by NMDA receptors, AMPA receptors and glycine receptors (Buldyrev et al. 2012), although similar data are not available for the ON BSGCs. Therefore, to investigate the effects of surround activation on the ON BSGC centre responses, we first characterized the centre synaptic inputs to these cells.

Synaptic inputs activated by centre stimulation of ON BSGCs

Centre responses were driven in ON BSGCs using a square-wave (1 Hz) modulated 100 μm-diameter spot. The spot size was smaller than the centre diameter estimated above by the DOG analysis, and therefore should produce little activation of the surround. Three stimulus intensities were applied to test the contrast dependence of the light-evoked currents. We recorded currents under voltage clamp at a range of holding potentials (Fig. 5A) and measured the net light-evoked I–V relations as a function of contrast (Fig. 5B). The I–V relations were remarkably linear, consistent with co-activation of linear excitatory and inhibitory inputs, and suggesting that NMDA receptors contributed little to the responses. Nonetheless, to estimate the upper bound to the level of NMDA input, we fitted the data using a basis function to account for the voltage dependence of the NMDA I–V relations (Manookin et al. 2010; Venkataramani & Taylor, 2010; Buldyrev et al. 2012). The NMDA basis function was evaluated from responses to puffs of 2 mm NMDA (continuous line in Fig. 5C, see Methods), and was used to resolve the synaptic conductance into a non-linear NMDA component, and linear excitatory (AMPA/kainate), and inhibitory components (Fig. 5D), as described previously for the OFF BSGCs (Buldyrev et al. 2012). In marked contrast to the OFF BSGCs, the average NMDA input to ON BSGCs was small (<25% of the total excitation, Fig. 5D). A recent modelling study suggests that inhibition that is co-activated with excitation can exacerbate space clamp errors and lead to under-estimation of excitatory inputs, and NMDA inputs in particular (Poleg-Polsky & Diamond, 2011). However, as shown below, even when inhibition was blocked, the NMDA component in ON BSGCs remained relatively small (Fig. 7G). The NMDA component was small enough that the synaptic currents could be adequately accounted for by a sum of linear excitation and inhibition (Fig. 5E). This simpler linear model was used to quantify the effects of stimulus size on excitation and inhibition in the analysis presented below.

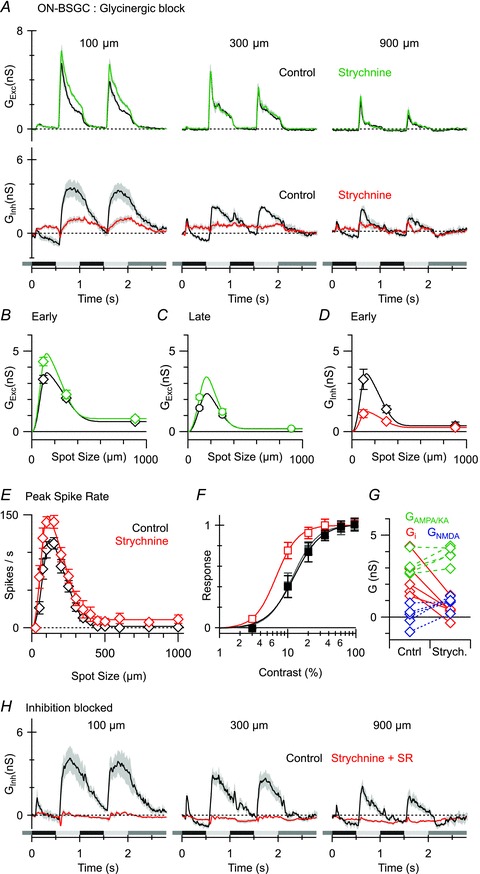

Figure 7. The effect of glycine and GABAA receptor blockade on light-evoked conductances and spike output in ON BSGCs.

A, average light-evoked conductances (n = 5; excitation, top panels; inhibition, bottom panels) in control (black) and in the presence of the glycine receptor antagonist strychnine (1 μm, coloured traces). B–D, mean conductances from the time points shown in Fig. 6Ca. E, mean spike rates (n = 5) during the early phase of the response plotted against stimulus diameter in control (black) and in the presence of strychnine (red). Note the doubling of spike rates for the smallest spot sizes. F, mean spike rates plotted against stimulus contrast in the same set of cells, in control, (black), in the presence of strychnine (red) and after drug washout (grey). Contrast–response curves were empirically fit with the Hill equation. The half maximum response contrast was decreased from 12% in control to 7% in the presence of strychnine. G, plot showing the effect of strychnine application on the magnitudes of each component of the light-evoked conductance in each of the cells from A. Strychnine strongly suppressed inhibition (red), did not significantly affect the linear component of excitation (green) and produced a small but significant increase in the NMDA component (blue). H, average responses (n = 4) in control (black traces) and in the presence of 1 μm strychnine and 25 μm SR95531 showing complete suppression of inhibitory input.

Similar to the OFF cells (Buldyrev et al. 2012), the inhibitory inputs to ON BSGCs were driven primarily through the ON pathway, as they were blocked by application of l-AP4 (data not shown). Therefore, the major inhibitory input was evoked in-phase with excitation in the ON cells and out of phase with excitation in the OFF cells. The role of this direct inhibition in either cell type remains unclear, although in the ON BSGCs the inhibition tended to activate more slowly and be more sustained than the excitation (Fig. 5E and F), and therefore could contribute to the relatively more transient spiking in ON versus OFF BSGCs. The experimental evidence below shows that the direct inhibitory inputs to ON BSGCs are largely glycinergic, similar to the OFF BSGCs (Buldyrev et al. 2012). The contrast–response data suggest that the synaptic input approached saturation at 60% contrast (Fig. 5F), and demonstrate that the 20% stimulus contrast used in the remainder of this study was sub-saturating. The inhibitory input increased by about 1.7-fold between 10 and 60% contrast, while excitation increased 2.9-fold, indicating that the inhibition saturated at lower contrast (Fig. 5F).

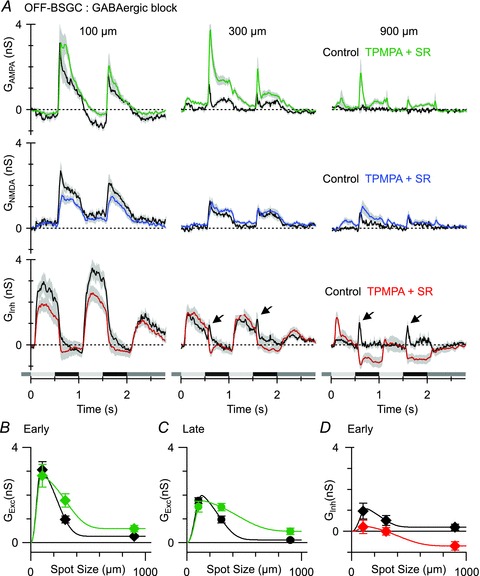

Synaptic mechanisms for surround suppression in both ON and OFF BSGCs

Past studies of lateral inhibition have focused on the modulation of bipolar cell output by OPL and GABAergic mechanisms (Dong & Werblin, 1998; Ichinose & Lukasiewicz, 2005; Eggers & Lukasiewicz, 2006; Chavez et al. 2010; Vigh et al. 2011). Retinal ganglion cells are also known to receive direct GABAergic inputs, but there is limited evidence that such inputs contribute to surround inhibition (Flores-Herr et al. 2001; Chen et al. 2010; Sivyer et al. 2011). Resolving the light-evoked excitatory and inhibitory inputs to ON and OFF BSGCs allowed us to explore whether the suppression of spike output by GABAergic surround mechanisms was due to presynaptic inhibition of bipolar cells or direct inhibitory inputs into BSGC dendrites.

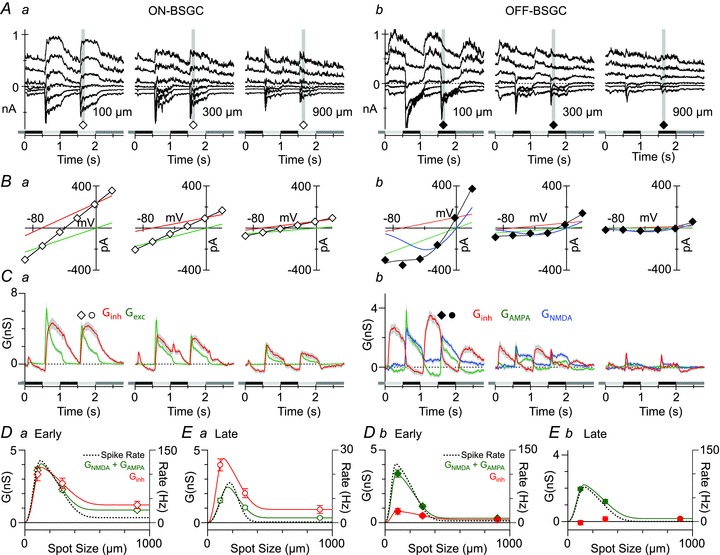

We recorded voltage-clamped current responses to 100, 300 and 900 μm spots, at a series of six holding potentials in 20 OFF and 15 ON BSGCs, and calculated the light-evoked inhibitory and excitatory conductances from the I–V curves (Fig. 6A and B). These cells were a subset of the control group used for extracellular recordings in Fig. 1. Inspection of the currents (Fig. 6A and B) and calculated conductances (Fig. 6C) show that surround activation produced strong suppression of both excitatory and inhibitory inputs to both the ON and the OFF BSGCs. For comparison with the spike rate data, the amplitudes of light-evoked conductances were measured at the early (Fig. 6D) and late (Fig. 6E) time points in the stimulus cycle.

Figure 6. Stimulus–size dependence of light-evoked synaptic inputs to ON and OFF BSGCs.

A, light evoked currents recorded in representative ON and OFF BSGCs at holding potentials starting at −98 mV and increasing by 25 mV. Each trace shows a single response. The stimulus spot, 20% contrast, was modulated at 1 Hz. The diameter is indicated in the bottom right corner of panels. B, current–voltage relations measured as the average current amplitude during the grey bars in A. The black lines show the fits to the I–V relations, which for the ON BSGCs are the sum of the inhibitory (red) and excitatory (green) conductances, and for the OFF BSGC show the sum of the linear inhibition and excitation, and the non-linear NMDA component (blue). C, light-evoked excitatory (green) and inhibitory (red) conductances averaged from 15 ON BSGCs and 20 OFF BSGCs, and calculated from the slopes of the I–V fits as shown in B. Blue lines show the NMDA component scaled to show the chord conductance at −70 mV. D and E, mean conductances measured at the time points indicated by the symbols in C. Dashed lines are the DOG integral fits to the area–response functions of the spike output measured in the same sets of cells at the same time points from extracellular recordings made prior to patch clamping the cells. Green points represent the total excitatory input, which is the sum of the AMPA and NMDA components for OFF BSGCs.

For the ON and OFF BSGCs, the suppression of the excitation at both the early and the late time points (green symbols, Fig. 6D and E) tracked the suppression of the spikes (dotted lines, Fig. 6D and E). However, for the largest stimulus sizes, at both time points, the spike responses were more strongly suppressed than the synaptic inputs, especially for ON BSGCs (ON early: 94 ± 1% spiking, 75 ± 3% excitation, P < 0.0001; ON late: 100% spike suppression in every cell, 75 ± 5% excitation. OFF early: 98 ± 1% suppression spiking vs. 90 ± 2% excitation, P ∼ 10−4; OFF late: 100 ± 0.5% spiking, 92 ± 2% excitation, P < 0.0001). The difference in suppression for spike rate versus synaptic conductance presumably is due to non-linearities associated with spike initiation.

The finding that postsynaptic inhibition does not increase with stimulus size for either the ON or the OFF BSGCs indicates that surround inhibition is not mediated by direct, feed-forward inhibition of BSGCs. This is particularly evident for OFF cells, where the inhibition is largely activated out of phase with excitation, and the surround suppression of the inhibition is almost complete (Fig. 6Cb). However, surround suppression of inhibitory inputs to the ON cells was not complete, and it is possible that the remaining inhibition seen for large stimuli may elevate spike threshold, and thereby contribute to the stronger surround suppression seen in the spike output. Previously we have shown that inhibitory inputs to OFF BSGCs are largely glycinergic (Buldyrev et al. 2012). The relatively weaker surround suppression of inhibitory inputs to ON BSGCs raises the possibility that these inputs might be mediated by GABA receptors, as GABAergic amacrine cells are generally wide-field cells in mammalian retina, and therefore should display correspondingly larger surrounds. However, it is also possible that the direct inhibitory inputs are mediated in part by glycine receptors. In the next experiments, we tested for a direct glycinergic input to ON BSGCs by applying the glycine receptor antagonist strychnine.

Direct inhibition to ON BSGCs is largely glycinergic

Application of 1 μm strychnine blocked a large fraction of the inhibitory input activated during the ON phase of the stimulus (n = 5, Fig. 7A and D), consistent with the presence of a direct glycinergic input. Blocking glycine receptors did not affect the excitatory input for larger spot sizes (Fig. 7A–C), suggesting that glycinergic inhibition does not contribute to surround suppression. This conclusion was supported by an analysis of area–response functions measured for spikes. Strychnine did not significantly affect the centre or surround space constant (n = 5, P = 0.2, P = 0.8) or the surround suppression index (SI = 99 ± 1% in control, and 94 ± 3% in strychnine, P = 0.15, Fig. 7E). However, strychnine did increase responses to the smallest four stimuli in all five cells, which suggests a role for glycinergic inhibition in setting the spike threshold or controlling the gain of the spike output during centre excitation. We tested whether the glycinergic input to ON BSGCs might modulate the gain of the contrast response function by applying stimuli ranging from 3 to 95% contrast within the receptive field centre. ON BSGCs were able to detect 3% contrast stimuli with strychnine in the bath, whereas this stimulus never elicited spikes with glycinergic inhibition intact (Fig. 7F). The contrast response function was well described by the Hill equation (continuous lines Fig. 7F). Strychnine reversibly decreased the half maximal contrast from 12 ± 2 to 7 ± 1% (P = 0.04), with little change in the Hill coefficient, indicating that the presence of the glycinergic input increases the threshold contrast in ON BSGCs, and allows them to encode a greater contrast range.

It seems most likely that the potentiation of spike responses during glycinergic block was due largely to the decrease in postsynaptic inhibition (Fig. 7G, red, control 2.4 ± 0.5 nS, strychnine 0.5 ± 0.3 nS, P = 0.007), although a small increase in the excitatory input was observed (Fig. 7A and B) that may also play a role. This increase in excitation for the smallest spots was significant for the NMDA component (Fig. 7G, blue, control 0.1 ± 0.3 nS; strychnine 0.9 ± 0.2 nS, P = 0.03), but did not reach significance for the AMPA component (Fig. 7G, green, control 3.2 ± 0.3 nS; strychnine 3.8 ± 0.2 nS; P = 0.05), although the trend appeared to be similar. It is unclear whether this increased excitation resulted from a decrease in presynaptic glycinergic inhibition, or whether the excitation simply became more visible due to better voltage clamp after inhibition was blocked (Poleg-Polsky & Diamond, 2011).

A minor component of inhibition in ON BSGCs is mediated by GABAA receptors

A residual inhibitory input was activated in the presence of strychnine, which was not strongly modulated by contrast, and was only partially suppressed as the stimulus size increased (Fig. 7A and D). Co-application of 25 μm SR95531 and 1 μm strychnine completely suppressed inhibition, consistent with the presence of a GABAA receptor-mediated input (n = 4, Fig. 7H). As this GABAA input did not increase with stimulus size, it did not represent a direct postsynaptic component of surround suppression. Our observation that only the GABAC receptor antagonist TPMPA affected surround suppression of spiking (Fig. 2A), and that no postsynaptic light-evoked GABAC receptor inputs were observed, suggests that the GABAC-mediated surround suppression in ON BSGCs is largely presynaptic.

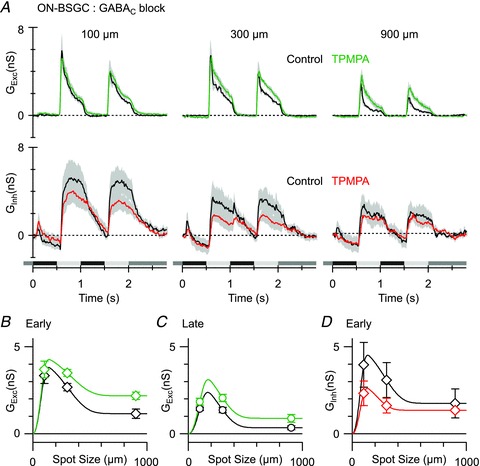

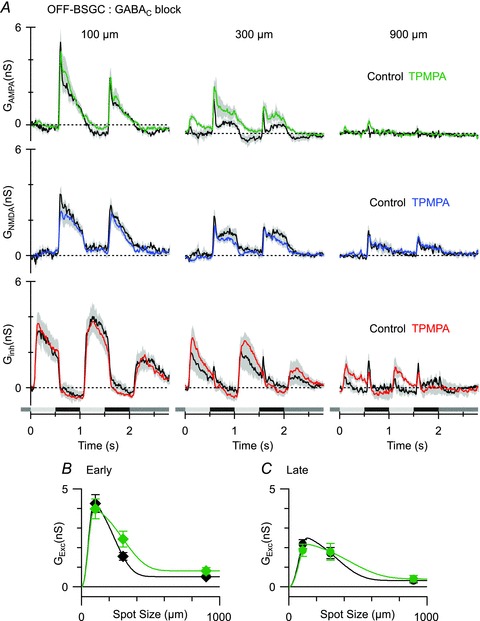

GABAC receptors contribute to ON BSGC surround inhibition by inhibiting ON bipolar cell output

If GABAC receptors mediate surround inhibition presynaptically at bipolar cell terminals, then TPMPA should potentiate excitatory inputs. Consistent with this idea, application of 50 μm TPMPA potentiated excitatory conductances (Fig. 8A), and reduced surround suppression of the excitatory inputs from 65 ± 7 to 40 ± 5% (n = 4, Fig. 8B; P = 0.015). The apparent reduction in inhibition in ON BSGCs (Fig. 8A) in the presence of TPMPA was not significant (Fig. 8D; P = 0.16 for 100 μm spot, P = 0.18 for 300 μm spot). As the variable effects of TPMPA seemed most obvious for small spot diameters, we cannot discount the possibility that blocking GABAC receptors can indirectly affect the output of narrow-field glycinergic amacrine cells. However, any effects on direct inhibition were not significant and cannot account for the reduced SI of spike output caused by GABAC block. Therefore, GABAC receptors mediate surround inhibition in ON BSGCs through presynaptic suppression of bipolar cell output. Presynaptic suppression of synaptic input also appeared to be the major mechanism for surround suppression in OFF BSGCs (Fig. 6Cb), and because GABA receptors are differentially expressed in the ON and OFF pathways, we were interested to examine the sensitivity of OFF BSGCs to GABAergic antagonists.

Figure 8. The effect of GABAC receptor block on light-evoked conductances in ON BSGCs.

A, mean light-evoked conductances (n = 4, 20% contrast, excitation, top panels; inhibition, bottom panels) in control (black) and in the presence of the GABAC receptor antagonist TPMPA (50 μm, coloured traces). B–D, mean conductances measured at the time points shown in Fig. 6Ca.

GABAC and GABAA receptors contribute to surround antagonism in OFF BSGCs

In agreement with measurements of the spike responses (Fig. 2B), blocking GABAC receptors did not significantly change the surround suppression of excitatory inputs in OFF BSGCs as measured for the 900 μm spot (Fig. 9A and B; n = 6, SI for total excitation: early phase 87 ± 3% in control and 78 ± 4% in TPMPA, P = 0.1; late phase 86 ± 5% control and 76 ± 7% in TPMPA, P = 0.3). However, TPMPA did reduce suppression evoked by the medium (300 μm) spot by 29% from 62 ± 5% in control to 33 ± 13% (Fig. 9B, P = 0.05). This effect is consistent with the small decrease in SI for spike output in the presence of TPMPA shown in Fig. 2B. Blocking both GABAA and GABAC receptors significantly reduced surround suppression of the spike responses (Figs 2F, 3B), and therefore we expected to see a significant effect on the synaptic inputs.

Figure 9. The effect of GABAC receptor blockade on light-evoked conductances in OFF BSGCs.

A, mean light-evoked conductances (n = 6, 20% contrast, AMPA, top panels; NMDA, middle panels; inhibition, bottom panels) in control (black) and in the presence of the GABAC receptor antagonist TPMPA (50 μm, coloured traces). B and C, mean conductances measured at the time points shown in Fig. 6Cb. Note that the data points show the total excitatory input, i.e. the sum of the NMDA and AMPA components.

Application of both SR95531 and TPMPA reduced surround suppression of the excitatory synaptic input during the early phase of the stimulus (Fig. 10A and B; SI decreased by 22% from 90 ± 2 to 78 ± 4%, n = 9, P = 0.01), and even more so during the late phase of the stimulus (Fig. 10A and C; SI decreased by 32% from 94 ± 3 to 62 ± 13%, P = 0.04). The co-application of SR95531 and TPMPA also blocked a transient inhibitory input that was evident at the onset of the stimulus cycle for the larger spots (arrows 300 and 900 μm, Fig. 10A; Fig. 10D; P = 0.008 for 900 μm). This transient component is also evident in the data shown in Figs 6Cb and 9A, but was unaffected by application of TPMPA (Fig. 9A lower right traces). Given that SR95531 caused a relatively small (0.8 ± 0.1 nS) increase of the excitatory input for the 900 μm stimulus, at least for the second stimulus cycle (Fig. 10B), it seems likely that suppression of the ∼1 nS inhibitory component (Fig. 10D) might have contributed to the spiking seen for larger spots in Fig. 2F, indicating that postsynaptic GABAA receptors may contribute to surround suppression in OFF BSGCs.

Figure 10. The effect of GABAC and GABAA receptor blockade on light-evoked conductances in OFF BSGCs.

A, mean light-evoked conductances (n = 9, 20% contrast, AMPA, top panels; NMDA, middle panels; inhibition, bottom panels) in control (black) and in the presence of 50 μm TPMPA and 25 μm SR95531 (coloured traces). Arrows indicate the peak of the transient inhibition that is activated at the start of the stimulus cycle and is most evident for large stimuli (see text for details). B–D, mean conductances measured at the time points shown in Fig. 6Cb. Note that in B and C the data points show the total excitatory input, i.e. the sum of the NMDA and AMPA components.

Overall, the effects of GABAergic block on the synaptic conductances were in agreement with the effects on the spiking responses (Fig. 2), and were largely due to the relief of presynaptic suppression of the excitatory inputs. Unlike the ON BSGCs, the results indicate that GABAergic surround inhibition in OFF BSGCs is mediated in part by GABAA receptor-mediated modulation of the output of OFF cone bipolar cells.

Discussion

Our analysis of ON and OFF BSGCs elucidates how inhibitory mechanisms in the IPL shape the spatio-temporal properties of these homologous cell types. In doing so we have also provided the first quantitative analysis of the excitatory and inhibitory synaptic inputs that drive the centre responses of ON BSGCs. These results, in combination with our previous analysis of OFF BSGCs (Buldyrev et al. 2012), show that the ON and OFF pathways providing inputs to these functionally homologous cell types drive spiking through distinct patterns of excitatory and inhibitory inputs that are not simply mirror-symmetric (Chichilnisky & Kalmar, 2002; Zaghloul et al. 2003; Pandarinath et al. 2010). Differences in GABAergic mechanisms between the ON and OFF pathways, with GABAC receptors apparently more active in the ON pathway, are in line with previous analysis of GABAC receptor knockout mice (Sagdullaev et al. 2006). The comparison of the ON and OFF BSGCs also demonstrates that for static luminance stimuli, the centre-surround organization in the two cell types is mediated in large part by OPL mechanisms, but that GABAergic mechanisms in the IPL provide a further level of tuning that involves distinct circuitry in the ON and OFF pathways.

Glycinergic inputs to ON and OFF BSGCs

We showed that ON BSGCs receive direct glycinergic inhibition, which is similar to glycinergic inhibition seen in the OFF BSGCs (Buldyrev et al. 2012), in that it is driven during the positive contrast phase of a flickering stimulus, and reflects input via the ON pathway. As the glycinergic input is driven through the ON pathway in both cell types, it is in phase with excitation in the ON BSGCs and out of phase in the OFF BSGCs. The different phase, relative to the preferred stimulus, suggests different functional roles in the two cell types. Previously we have suggested that glycinergic inputs may augment excitation in the OFF BSGCs, as it represents a push–pull arrangement with the excitation in these cells (Buldyrev et al. 2012). For ON BSGCs, the inhibition opposes excitation, and we propose that the amplitude of this inhibition, relative to excitation, might modulate the gain and dynamic range of ON BSGCs. Consistent with this notion, we found that blocking the glycinergic input shifted the contrast response relation towards lower contrasts (Fig. 7F). In this context, it is noteworthy that the inhibition was slower to activate and more sustained than excitation, and therefore may represent a mechanism for contrast adaptation on time scales of tens to hundreds of milliseconds.

Glycinergic inhibition in large- and small-field concentric cells

Our analysis of the circuitry driving BSGCs reveals interesting similarities with large-field α-type ganglion cells in guinea pig (Zaghloul et al. 2003) and mouse (Pang et al. 2003; van Wyk et al. 2009). Similar to the ON BSGCs, as we have shown here, the ON α cells receive glycinergic inhibition from the ON pathway. Moreover, similar to the OFF BSGCs, OFF α cells in these species receive glycinergic crossover inhibition from the ON pathway. However, the crossover inhibition to OFF α cells is tonically active at rest, and is suppressed during the OFF phase of a stimulus, while in the OFF BSGCs, the crossover inhibition is inactive at rest and is activated during the ON phase of the stimulus. The different modes of action of this ON pathway inhibition in the two cell types suggest that it arises from distinct glycinergic amacrine cells. Indeed, the AII amacrine cell is the source of the inhibition for OFF α cells (Zaghloul et al. 2003; Manookin et al. 2008; van Wyk et al. 2009), while the AII was eliminated as a possible source in the OFF BSGCs (Buldyrev et al. 2012). Recently we have shown that other OFF ganglion cell types receive crossover inhibition that is not mediated by AII amacrine cells (Venkataramani & Taylor, 2010). Thus glycinergic amacrine cells appear to contribute to the centre receptive field properties in a variety of retinal ganglion cell types. It is noteworthy that the glycinergic inhibition in these diverse ganglion cell types represents a conductance comparable to, or in some cells larger than, the excitatory inputs. However, for typical resting potentials, the driving force for inhibition will be much smaller than for excitation, and therefore it seems likely that the spiking output will be more strongly influenced by the characteristics of the excitatory inputs.

Synaptic mechanisms generating surround antagonism

The surrounds measured from the area–response curves of spike output in both ON and OFF BSGCs were consistent with contributions from both plexiform layers. The voltage clamp analysis indicated that in both the ON and the OFF BSGCs, presynaptic mechanisms suppressed both excitatory and inhibitory synaptic input to the centre of the receptive field. As surround antagonism did not involve an increase in inhibitory input to the ganglion cells, the major mechanism producing surround antagonism of spiking responses was suppression of excitatory inputs. Presynaptic suppression of excitation could involve horizontal cell activity in the OPL, or amacrine cell activity in the IPL, but the relative contributions of these two mechanisms remain to be determined for most ganglion cells. As most evidence indicates that horizontal cells produce surround inhibition by non-GABAergic feedback modulation of calcium channel activity in the photoreceptors either by an ephaptic or a pH-dependent mechanism (Byzov & Shura-Bura, 1986; Kamermans et al. 2001; Hirasawa & Kaneko, 2003; Verweij et al. 2003; Vessey et al. 2005; Cadetti & Thoreson, 2006) it seems likely that GABA receptor antagonists effectively isolate the outer plexiform mechanisms. Indeed, in agreement with prevous studies showing that extracellular Hepes can suppress the non-GABAergic OPL surround inhibition, we found that the addition of 20 mm Hepes to the extracellular solution, in the presence of GABAergic antagonists, further reduced SI by ∼30% in ON BSGCs and ∼35–55% in OFF BSGCs. However, in agreement with previous results in fish horizontal cells (Fahrenfort et al. 2009), surround suppression was not eliminated under these conditions, perhaps because the Hepes does not completely suppress the OPL surround mechanism in rabbit. The finding that suppressing only the OPL surround using Hepes alone had minimal effect, while GABAergic antagonists alone decreased SI by ∼20–40% (compare Fig. 4A and B to Figs 2E, F and 3B), indicates that the IPL surround mechanisms provide a major portion of the spatial tuning in ON and OFF BSGCs.

However, although the evidence remains inconclusive, horizontal cells have been proposed to mediate GABAergic surround inhibition, by activating receptors on either bipolar cell dendrites or photoreceptor terminals (Wu et al. 1981; Ayoub & Lam, 1984; Schwartz, 1987; Vardi et al. 1992). Despite the presence of GABA receptors on cone terminals (Pattnaik et al. 2000), GABA antagonists have not been found to affect surround inhibition in cone photoreceptors (Thoreson & Burkhardt, 1990; Verweij et al. 1996). Similarly, GABA receptors have been localized to bipolar cell dendrites (Enz et al. 1996; Haverkamp et al. 2000), but for these receptors to be functionally effective, GABA should depolarize ON bipolar cells and hyperpolarize OFF bipolar cells (Vardi & Sterling, 1994). Differential expression of the Na–K–Cl co-transporters (Vardi et al. 2000) has been proposed as a mechanism to elevate chloride concentration in ON bipolar cell dendrites. However, direct estimates of chloride gradients in ON cone bipolar cell dendrites indicate that GABA is not likely to produce marked depolarization (Billups & Attwell, 2002; Duebel et al. 2006). Therefore, it seems most likely that the GABA antagonists are active on GABA receptors in the IPL.

Further support for this interpretation is the observation that under conditions that were expected to completely block IPL surround mechanisms (GABAA and GABAC blockers in OFF BSGCs, GABAC blockers in ON BSGCs), the space constants for surround antagonism became broader and were very similar in the ON and OFF BSGCs (∼1 mm diameter), as expected for a common horizontal cell-mediated mechanism in the OPL (Lankheet et al. 1990; Zhang et al. 2011). However, under these same conditions, the surround suppression of the excitatory inputs to the ON BSGCs (43%) was weaker than that for the OFF BSGCs (78%, Figs 8B and 10B). If the surround under GABAergic blockade largely reflects a common OPL mechanism, these results suggest that compared to the OFF cone bipolar cells, glutamate release from ON cone bipolar cells is less susceptible to OPL surround suppression. One possible explanation for this difference derives from previous work showing that the glutamate release from OFF bipolar cells is more strongly rectified than for the ON bipolar cells (Zaghloul et al. 2003; Liang & Freed, 2010), which might allow surround antagonism to produce a disproportionately larger suppression of glutamate release from the OFF versus the ON bipolar cells.

Such considerations cannot account for the difference in spatial tuning between the ON and OFF BSGCs observed at the late time point during spiking responses, under conditions designed to suppress OPL and IPL surround mechanisms (Fig. 4C and D). However, as noted above, the 20 mm Hepes did not suppress the OPL surround completely (Fahrenfort et al. 2009). Moreover, ON BSGCs produce more transient spiking responses than OFF BSGCs, probably due to more transient excitatory inputs. Perhaps the residual OPL surround suppressed the relatively transient excitatory inputs in the ON BSGCs below spike threshold at the late time point in Fig. 4.

IPL surround mechanisms

Presynaptic inhibition of excitatory inputs, probably mediated by wide-field amacrine cells, accounted for most of the GABAergic surround suppression in ON and OFF BSGCs (Figs 8B and 10B). This inhibition is consistent with the extensive expression of GABAA and GABAC receptors in the IPL (Greferath et al. 1995; Koulen et al. 1998), where they have been localized to cone bipolar cell terminals (Shields et al. 2000; Zhou & Dacheux, 2005). In comparing the ON and OFF BSGCs, we found that blocking GABAA receptors did not significantly affect surround suppression in either cell type, whereas blocking GABAC receptors reduced the surround antagonism more in ON than in OFF BSGCs, which seems consistent with the stronger expression of GABAC receptors in ON bipolar cells (Shields et al. 2000; Zhou & Dacheux, 2005). It is interesting to note that lateral inhibition in rat rod bipolar cells, which are also ON-type cells, is mediated exclusively by GABAC receptors, whereas GABAA receptors mediate local feedback (Chavez et al. 2010).

In OFF BSGCs, both GABAA and GABAC receptor blockade was required to reduce surround antagonism of spike output to the same extent as was observed in ON BSGCs with only GABAC receptor block. The apparently synergistic effects of GABAA and GABAC receptors might be explained by the presence of serial inhibitory synapses in the amacrine cell network (Zhang et al. 1997). For example, blocking GABAA receptors might lead to enhanced GABAC receptor activation, in a similar way that blocking GABAA receptors increases glycinergic inhibition in mouse OFF cone bipolar cells (Eggers & Lukasiewicz, 2010). Thus, the loss of GABAA-mediated inhibition might be compensated for by an increase in GABAC activity. Such an arrangement seems plausible, because GABAergic amacrine cells receive only GABAA receptor inputs, while OFF bipolar cells express both GABAA and GABAC receptors at their terminals (Enz et al. 1996; Koulen et al. 1998; Eggers & Lukasiewicz, 2010).

An alternative possibility is that parallel GABAA and GABAC pathways produce surround inhibition with different spatial scales (Vigh et al. 2011). For example, if GABAC receptors mediated a narrow surround relative to GABAA receptors, then blocking GABAC receptors might increase the firing rate in response to moderately sized spots, leaving GABAA receptors to suppress responses to larger spots (Fig. 2B). Similarly, GABAC block would only affect the excitatory input for the intermediate (300 μm) spot (Fig. 9A and B). Conversely, blocking GABAA receptors would have no effect on its own, because the larger spots required to activate this pathway would have maximally activated the narrow-field circuit that drives GABAC receptors (Fig. 2D). Blocking both receptor types would be required to suppress inner plexiform surround inhibition, and reveal the contribution from the OPL. Certainly, the considerable diversity among GABAergic amacrine cell morphology (Pourcho & Goebel, 1983) and the ability of some of these cells to transmit information over long distances via action potentials (Taylor, 1996; Bloomfield & Volgyi, 2007) would allow IPL inhibition to operate on multiple spatial scales.

Postsynaptic mechanisms

Under control conditions (Fig. 6) and during GABAergic block (Figs 8B and 10B), presynaptic suppression of excitation in the ON BSGCs was weaker than that for OFF BSGCs, yet the surround suppression of spiking was similar in both cell types (Fig. 2). It seems likely that the inhibitory inputs, which are active in-phase with the excitation in the ON BSGCs, account for this equivalence by increasing the threshold for spike initiation in the ON BSGCs. Thus, although the postsynaptic inhibition is also subject to surround suppression, it may play an indirect role in sharpening the spatial tuning properties of ON BSGCs. Such a mechanism has been proposed for cortical neurons, where a weakly tuned or un-tuned inhibitory input combines with selective excitatory inputs to enhance spike output tuning by raising spike threshold, and thereby suppressing spikes in response to less optimal stimuli that generate weak excitation (reviewed by Isaacson & Scanziani, 2011). Similarly, although inhibition to OFF BSGCs is largely activated out-of-phase with excitation, the small transient inhibitory inputs activated in-phase with excitation may contribute to the stronger surround suppression of spikes (SI = 98%) compared with the excitatory inputs (SI = 90%, Fig. 10D).

In summary, surround antagonism for luminance signals is presynaptic to the ganglion cells, suppresses glutamate release from bipolar cells and is mediated in part by non-GABAergic mechanisms, probably due to horizontal cell feedback onto cone photoreceptor terminals in the OPL. Blocking GABAergic inhibition in the IPL produces significant effects on the spike output of ganglion cells, consistent with the notion that IPL mechanisms refine the luminance surround generated in the OPL. The GABA receptor-mediated component of the surround probably results from inhibition of bipolar cells, and we propose that the GABA receptors are located on the bipolar cell axon terminals in the IPL. However, our results do not absolutely exclude a role for GABA receptors on the dendrites of bipolar cells.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grant EY014888 (W.R.T.), an award from Research to Prevent Blindness (RPB) to W.R.T., and an unrestricted grant from RPB to the Casey Eye Institute.

Glossary

- BSGC

brisk-sustained ganglion cell

- IPL

inner plexiform layer

- OPL

outer plexiform layer

Author contributions

I.B. collected the data, and I.B. and W.R.T. designed the experiments, analysed and interpreted the data, and wrote the paper.

References

- Amthor FR, Takahashi ES, Oyster CW. Morphologies of rabbit retinal ganglion cells with concentric receptive fields. J Comp Neurol. 1989;280:72–96. doi: 10.1002/cne.902800107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub GS, Lam DM. The release of γ-aminobutyric acid from horizontal cells of the goldfish (Carassius auratus) retina. J Physiol. 1984;355:191–214. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barlow HB, Levick WR. The mechanism of directionally selective units in rabbit's retina. J Physiol. 1965;178:477–504. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1965.sp007638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billups D, Attwell D. Control of intracellular chloride concentration and GABA response polarity in rat retinal ON bipolar cells. J Physiol. 2002;545:183–198. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.024877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloomfield SA, Volgyi B. Response properties of a unique subtype of wide-field amacrine cell in the rabbit retina. Vis Neurosci. 2007;24:459–469. doi: 10.1017/S0952523807070071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boycott BB, Wässle H. The morphological types of ganglion cells of the domestic cat's retina. J Physiol. 1974;240:397–419. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buldyrev I, Puthussery T, Taylor WR. Synaptic pathways that shape the excitatory drive in an OFF retinal ganglion cell. J Neurophys. 2012;107:1795–1807. doi: 10.1152/jn.00924.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byzov AL, Shura-Bura TM. Electrical feedback mechanism in the processing of signals in the outer plexiform layer of the retina. Vision Res. 1986;26:33–44. doi: 10.1016/0042-6989(86)90069-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cadetti L, Thoreson WB. Feedback effects of horizontal cell membrane potential on cone calcium currents studied with simultaneous recordings. J Neurophys. 2006;95:1992–1995. doi: 10.1152/jn.01042.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JH, Daw NW. New properties of rabbit retinal ganglion cells. J Physiol. 1978a;276:257–276. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JH, Daw NW. Effects of picrotoxin and strychnine on rabbit retinal ganglion cells: changes in centre surround receptive fields. J Physiol. 1978b;276:299–310. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell JH, Daw NW, Wyattt HJ. Effects of picrotoxin and strychnine on rabbit retinal ganglion cells: lateral interactions for cells with more complex receptive fields. J Physiol. 1978;276:277–298. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1978.sp012233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chavez AE, Grimes WN, Diamond JS. Mechanisms underlying lateral GABAergic feedback onto rod bipolar cells in rat retina. J Neurosci. 2010;30:2330–2339. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5574-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Hsueh H, Greenberg K, Werblin FS. Three forms of spatial temporal feedforward inhibition are common to different ganglion cell types in rabbit retina. J Neurophys. 2010;103:2618–2632. doi: 10.1152/jn.01109.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chichilnisky EJ, Kalmar RS. Functional asymmetries in ON and OFF ganglion cells of primate retina. J Neurosci. 2002;22:2737–2747. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-07-02737.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleland BG, Dubin MW, Levick WR. Sustained and transient neurones in the cat's retina and lateral geniculate nucleus. J Physiol. 1971;217:473–496. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1971.sp009581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook PB, McReynolds JS. Lateral inhibition in the inner retina is important for spatial tuning of ganglion cells. Nat Neurosci. 1998;1:714–719. doi: 10.1038/3714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dacey D, Packer OS, Diller L, Brainard D, Peterson B, Lee B. Center surround receptive field structure of cone bipolar cells in primate retina. Vision Res. 2000;40:1801–1811. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(00)00039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davenport CM, Detwiler PB, Dacey DM. Effects of pH buffering on horizontal and ganglion cell light responses in primate retina: evidence for the proton hypothesis of surround formation. J Neurosci. 2008;28:456–464. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2735-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demas J, Sagdullaev BT, Green E, Jaubert-Miazza L, McCall MA, Gregg RG, Wong RO, Guido W. Failure to maintain eye-specific segregation in nob, a mutant with abnormally patterned retinal activity. Neuron. 2006;50:247–259. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.03.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demb JB, Haarsma L, Freed MA, Sterling P. Functional circuitry of the retinal ganglion cell's nonlinear receptive field. J Neurosci. 1999;19:9756–9767. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-22-09756.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devries SH, Baylor DA. Mosaic arrangement of ganglion cell receptive fields in rabbit retina. J Neurophys. 1997;78:2048–2060. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.4.2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong CJ, Werblin FS. Temporal contrast enhancement via GABAC feedback at bipolar terminals in the tiger salamander retina. J Neurophys. 1998;79:2171–2180. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.79.4.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duebel J, Haverkamp S, Schleich W, Feng G, Augustine GJ, Kuner T, Euler T. Two-photon imaging reveals somatodendritic chloride gradient in retinal ON-type bipolar cells expressing the biosensor Clomeleon. Neuron. 2006;49:81–94. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers ED, Lukasiewicz PD. Receptor and transmitter release properties set the time course of retinal inhibition. J Neurosci. 2006;26:9413–9425. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2591-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers ED, Lukasiewicz PD. Interneuron circuits tune inhibition in retinal bipolar cells. J Neurophys. 2010;103:25–37. doi: 10.1152/jn.00458.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eggers ED, McCall MA, Lukasiewicz PD. Presynaptic inhibition differentially shapes transmission in distinct circuits in the mouse retina. J Physiol. 2007;582:569–582. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2007.131763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enroth-Cugell C, Robson JG. The contrast sensitivity of retinal ganglion cells of the cat. J Physiol. 1966;187:517–552. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1966.sp008107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enz R, Brandstätter JH, Wässle H, Bormann J. Immunocytochemical localization of the GABAC receptor ρ subunits in the mammalian retina. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4479–4490. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-14-04479.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrenfort I, Steijaert M, Sjoerdsma T, Vickers E, Ripps H, van Asselt J, Endeman D, Klooster J, Numan R, ten Eikelder H, von Gersdorff H, Kamermans M. Hemichannel-mediated and pH-based feedback from horizontal cells to cones in the vertebrate retina. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6090. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Herr N, Protti DA, Wässle H. Synaptic currents generating the inhibitory surround of ganglion cells in the mammalian retina. J Neurosci. 2001;21:4852–4863. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-13-04852.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freed MA, Smith RG, Sterling P. Timing of quantal release from the retinal bipolar terminal is regulated by a feedback circuit. Neuron. 2003;38:89–101. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(03)00166-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greferath U, Grunert U, Fritschy JM, Stephenson A, Mohler H, Wassle H. GABAA receptor subunits have differential distributions in the rat retina: in situ hybridization and immunohistochemistry. J Comp Neurol. 1995;353:553–571. doi: 10.1002/cne.903530407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haverkamp S, Grunert U, Wassle H. The cone pedicle, a complex synapse in the retina. Neuron. 2000;27:85–95. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00011-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirasawa H, Kaneko A. pH changes in the invaginating synaptic cleft mediate feedback from horizontal cells to cone photoreceptors by modulating Ca2+ channels. J Gen Physiol. 2003;122:657–671. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochstein S, Shapley RM. Quantitative analysis of retinal ganglion cell classifications. J Physiol. 1976;262:237–264. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1976.sp011594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichinose T, Lukasiewicz PD. Inner and outer retinal pathways both contribute to surround inhibition of salamander ganglion cells. J Physiol. 2005;565:517–535. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.083436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS, Scanziani M. How inhibition shapes cortical activity. Neuron. 2011;72:231–243. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]