Background: Endothelium-expressed intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) is considered critical for the development of cerebral malaria (CM).

Results: ICAM-1 expression on leukocytes alone was sufficient for the development of experimental CM.

Conclusion: Endothelial expression of ICAM-1 is not required for development of CM.

Significance: Vascular occlusion in CM requires ICAM-1 expression on leukocytes but not endothelial cells.

Keywords: Adhesion, Endothelial Cell, Immunology, Leukocyte, Malaria, Neuroimmunology, Parasitology, Trafficking

Abstract

Cerebral malaria (CM) is a severe clinical complication of Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection and is characterized by a high fatality rate and neurological damage. Sequestration of parasite-infected red blood cells in brain microvasculature utilizes host- and parasite-derived adhesion molecules and is an important factor in the development of CM. ICAM-1, an alternatively spliced adhesion molecule, is believed to be critical on endothelial cells for infected red blood cell sequestration in CM. Using ICAM-1 mutant mice, we found that the full-length ICAM-1 isoform is not required for development of murine experimental CM (ECM) and that ECM phenotype varies with the combination of ICAM-1 isoforms expressed. Furthermore, we observed development of ECM in transgenic mice expressing ICAM-1 only on leukocytes, indicating that endothelial cell expression of this adhesion molecule is not required for disease pathogenesis. We propose that ICAM-1-dependent cellular aggregation, independent of ICAM-1 expression on the cerebral microvasculature, contributes to ECM.

Introduction

Cerebral malaria (CM)2 is thought to arise from a confluence of inflammatory events in which infected RBCs (iRBC), activated leukocytes, and platelets are sequestered on inflamed endothelium due to increased expression of adhesion molecules (1). Among the large number of adhesion molecules implicated in CM development, ICAM-1 has long been known to bind and retain iRBCs in the central nervous system (CNS) microvasculature (2–4). ICAM-1 binds to Plasmodium falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1 (PfEMP1) through its N-terminal Ig domain (5–7) and to several members of the β2-integrin family of adhesion molecules including LFA-1, Mac-1, and p150,95 (8). ICAM-1 is expressed on essentially all cell types contributing to CM development including lymphocytes, myeloid cells, platelets, and endothelial cells (9) (8, 10, 11). The increased expression of ICAM-1 and other adhesion molecule receptor/ligand pairs within the microvasculature sets the stage for vessel occlusion under inflammatory conditions driven by proinflammatory cytokines produced during malaria infection (12, 13).

The importance of ICAM-1 in CM is based on studies demonstrating the relationship between increased endothelial cell ICAM-1 expression and iRBC sequestration in human and murine CM (1, 14). In experimental cerebral malaria (ECM), the animal model of CM, treatment with anti-ICAM-1 antibodies markedly inhibited rolling and iRBC sequestration in the central nervous system (3, 4, 15). Anti-ICAM-1 antibodies also inhibited adherence and rolling of iRBCs on LPS-primed brain sections or ICAM-1-transfected cells (3). Furthermore, there are reports that ICAM-1 polymorphisms are associated with severe forms of malaria, particularly CM, although this remains controversial (16–18). Although these data indicate a critical role for ICAM-1 in iRBC binding to endothelium, no study has directly addressed the requirement of ICAM-1 in the development of ECM.

Multiple isoforms of ICAM-1, arising from alternative splicing, have been described in humans and mice (19–24). However, their function, changes in expression, and relative expression on various cell types involved in the development of ECM remain unknown. We show here that ICAM-1 mutant mice deficient in all ICAM-1 isoforms (Icam1null) are highly resistant to the development of ECM. In contrast, mice expressing different combinations of three of the six known isoforms, but not the full-length molecule (Icam1tm1Jcgr and Icam1tm1Bay mice), are more susceptible to ECM. These data demonstrate that although the full-length ICAM-1 protein is not required for disease initiation, ECM is attenuated in its absence. We also report the unexpected finding that ICAM-1 expression on CNS microvasculature is not required for ECM development. For these studies, Icam1null mice were bred with newly developed transgenic mice that express the full-length ICAM-1 isoform under the control of the leukocyte-specific promoter CD2. We observed that these transgenic mice, unlike Icam1null mice, were highly susceptible to ECM. These observations suggest that ICAM-1-mediated aggregation of leukocytes, platelets, and iRBC within the vascular space, independent of expression on the microvasculature, is critical for promoting vessel occlusion during the development of ECM.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Mice and Treatment Procedures

Icam1null mutant mice (Icam1tm1Alb) were backcrossed at least 12 generations onto C57BL/6 (25). Icam1tm1Jcgr and Icam1tm1Bay C57BL/6J (N10) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) and have been previously described (26, 27). CD2-Icam1fl/Icam1null mice were generated by inserting the full-length ICAM-1 cDNA into a CD2 minigene cassette vector (28, 29). Male and female mice between the ages of 8–12 weeks were used for all experiments. Plasmodium berghei ANKA (PbA) was maintained by passage in BALB/c mice as described previously (30). ECM was induced by injecting mice intraperitoneally with 5 × 105 PbA-infected RBCs, and parasitemia and disease progression were monitored twice daily as described previously (31).

Flow Cytometry

CD2-restricted expression of ICAM-1 on leukocytes was determined by flow cytometry as described previously (32). Inbred C57BL/6 mice were used as controls for all experiments. T cell infiltration into brains at day 6 after infection was assessed by flow cytometry as described previously (33).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical significance of ECM survival was calculated using the log rank test using Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The Mann-Whitney test was used to determine significant differences in ECM clinical scores. Data are shown as mean ± S.E. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Icam1null Are Highly Resistant to ECM, whereas Icam1tm1Jcgr and Icam1tm1Bay Are Partially Resistant

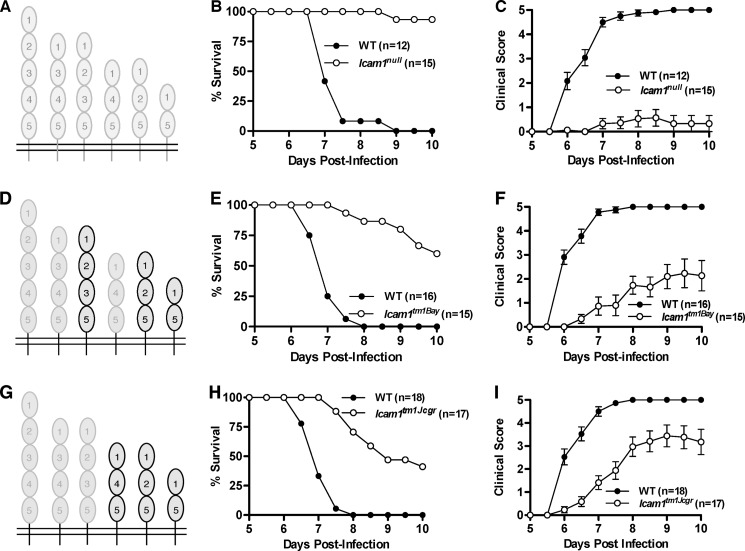

Although changes in ICAM-1 expression are well documented in both severe and cerebral malaria (1, 14), no study has directly assessed ECM severity and development using mice deficient in all ICAM-1 isoforms. For these studies, we used three different lines of ICAM-1 mutant mice, including Icam1null mice, which lack all known ICAM-1 isoforms (Fig. 1A). We observed that Icam1null mice were highly resistant to ECM, with >90% of mice surviving past day 10, whereas all wild type mice succumbed to disease on or before day 9 (Fig. 1B, Table 1, p = 0.0001, Log rank test). Icam1null mice had a corresponding reduction in clinical scores (Fig. 1C, Table 1, cumulative disease index: 1.4 versus 18.3, p < 0.0001, Mann-Whitney test) and a marked reduction in CNS T cell infiltration (CD4+, 65% decrease; CD8+, 84% decrease) as compared with wild type mice. In contrast, two ICAM-1 mutant strains of mice that express only three of the six known ICAM-1 isoforms, but not the full-length isoform (Icam1tm1Bay and Icam1tm1Jcgr, Fig. 1, D and G, respectively), develop more severe ECM than Icam1null mice. Icam1tm1Bay mice were previously shown to develop attenuated ECM as compared with wild type mice (34), a finding we replicate in the present study (Fig. 1, E and F, Table 1). Icam1tm1Bay mice, however, have lower survival and worse clinical scores as compared with Icam1null mice (60% versus 93% survival, cumulative disease index 5.5 versus 1.4, respectively). T cell infiltration into the CNS was also reduced in these mice as compared with wild type mice (CD4+, 31% decrease; CD8+, 84% decrease). In contrast, Icam1tm1Jcgr mice were most susceptible to ECM of the three ICAM-1 mutant mice, with the lowest survival rate and highest clinical scores (Fig. 1, H and I, Table 1). The extent of CNS T cell infiltration in Icam1tm1Jcgr mice corresponded to increased disease severity with a modest reduction in CD4+ T cells (30% decease), but an increase in CD8+ T cells (12% increase) as compared with wild type mice.

FIGURE 1.

ICAM-1 mutant mice are resistant to the development of ECM. Wild type, Icam1tm1Jcgr, and Icam1tm1Bay mice were injected intraperitoneally with 5 × 105 PbA-iRBC, and clinical scores and survival were monitored twice daily for 10 days as described in Ref. 37. A, schematic of ICAM-1 with isoforms missing in Icam1null mice shown in light gray. B, Icam1null mice (n = 15) were significantly resistant to disease-induced mortality (p = 0.0001, log rank test; 93% survival past day 10) as compared with wild type mice (n = 12). C, Icam1null mice had significantly reduced clinical signs of disease (p < 0.0001 from day 6 onward, Mann-Whitney test) as compared with wild type mice. D, schematic of ICAM-1 with isoforms expressed by Icam1tm1Bay mice shown in black outline. E, Icam1tm1Bay mice (n = 15) were significantly resistant to disease-induced mortality (p = 0.0001, log rank test; 60% survival past day 10) as compared with wild type mice (n = 16). F, Icam1tm1Bay mice had significantly reduced clinical signs of disease (p < 0.0001 from day 6 onward, Mann-Whitney test) as compared with wild type mice. G, schematic of ICAM-1 with isoforms expressed by Icam1tm1Jcgr mice shown in black outline. H, Icam1tm1Jcgr mice (n = 17) were significantly resistant to disease-induced mortality (p = 0.0001, log rank test; 41% survival past day 10) as compared with wild type mice (n = 17). I, Icam1tm1Jcgr mice had significantly reduced clinical signs of disease (p < 0.0001 from day 6 onward, Mann-Whitney test) as compared with wild type mice. Shown is the mean ± S.E. of 3–4 independent experiments for all groups of mice.

TABLE 1.

Survival and clinical scores for wild type and ICAM-1 mutant mice with ECM

| ICAM-1 genotype | % of survivala | Clinical disease (WT vs. mutant)b |

|---|---|---|

| Wild type (n = 12–18) | 0 | |

| Icam1null (n = 15) | 93 | 18.3 vs. 1.4c |

| Icam1tm1Bay (n = 15) | 60 | 19.4 vs. 5.5c |

| Icam1tm1Jcgr (n = 17) | 41 | 19 vs. 9.4c |

| CD2-Icam1fl/Icam1null (n = 18) | 6 | 18.5 vs. 9.9d |

a Percentage of mice that survive to day 10 after infection with PbA.

b The area under the curve for the clinical scores from days 1–10.

c p < 0.05, days 6–10.

d p < 0.05, days 6–8.5.

ICAM-1 Isoform Expression Solely on Leukocytes Is Sufficient for ECM Development

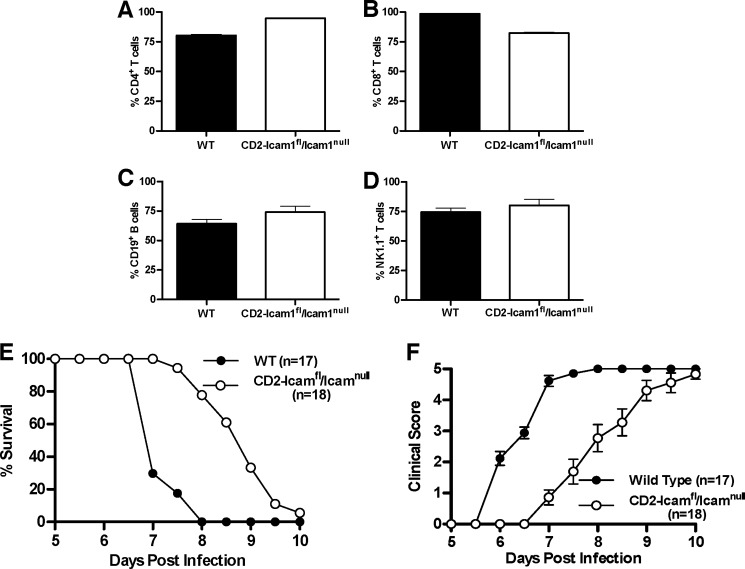

It has been assumed that ICAM-1 contributes to CM predominately, if not exclusively, via expression on endothelial cells based on its function in the classic rolling/firm adhesion/transmigration paradigm used by leukocytes for trafficking to sites of inflammation or into lymphoid tissues (35–38). To directly determine whether ICAM-1 expression on the microvasculature is required for ECM development, we generated transgenic mice with an ICAM-1-deficient background that expressed only the full-length ICAM-1 isoform on leukocytes (CD2-Icam1fl/Icam1null). Expression of the full-length isoform on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, CD19+ B cells, and natural killer cells from CD2-Icam1fl/Icam1null mice was comparable with that seen on wild type mice (Fig. 2, A–D). We then performed ECM using wild type and CD2-Icam1fl/Icam1null mice. We observed that CD2-Icam1fl/Icam1null mice were fully susceptible to ECM; however, they progressed to fatal ECM significantly more slowly than wild type mice (p < 0.0001, Log rank test, ∼2-day delay) with a corresponding decline in clinical scores (Fig. 2, E and F, Table 1). These results demonstrate that expression of a single ICAM-1 isoform, in this case the full-length ICAM-1 isoform, on leukocytes alone is sufficient to drive development of ECM, independent of expression on endothelium.

FIGURE 2.

Leukocyte-specific expression of the full-length ICAM-1 isoform in the Icam1null background leads to ECM development. A–D, expression of the full-length ICAM-1 isoform on CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, CD19+ B cells, and natural killer cells from CD2-Icam1fl/Icam1null mice is comparable with expression on leukocytes isolated from wild type mice, as determined by flow cytometry (n = 3 for each group). E, CD2-Icam1fl/Icam1null mice (n = 18) were significantly resistant to disease-induced mortality (p < 0.0001, log rank test; 6% survival past day 10) as compared with wild type mice (n = 17). F, CD2-Icam1fl/Icam1null mice had significantly reduced clinical signs of disease (p < 0.0001 from days 6–8.5, Mann-Whitney test) as compared with wild type mice. Shown is the mean ± S.E. of 3–4 independent experiments for all groups of mice.

Our results indicate that ICAM-1 is critical to the development of ECM because deletion of all isoforms essentially prevents disease development. However, the disease phenotypes of the Icam1tm1Jcgr and Icam1tm1Bay mice raise two important points. 1) The absence of the full-length ICAM-1 isoform does not prevent the development of ECM, and 2) variable combinations of ICAM-1 isoforms in the absence of the full-length isoform result in distinct ECM phenotypes, indicating that multiple isoforms can contribute to disease outcome. This is remarkable because Icam1tm1Jcgr and Icam1tm1Bay mice share two of the three expressed isoforms (Fig. 1, D and G). It is worth noting that in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), the disease phenotype of Icam1tm1Jcgr and Icam1tm1Bay mice is reversed as compared with what we report here for ECM (39). Thus Icam1tm1Bay mice developed severe EAE, whereas Icam1tm1Jcgr mice developed mild EAE. This contrast in disease phenotypes suggests differential utilization and/or signaling mechanisms based on the combination of ICAM-1 isoforms expressed on leukocytes and endothelium.

Perhaps the most interesting finding in our study was the observation that leukocyte expression of a single ICAM-1 isoform, in an otherwise Icam1null background, was sufficient for ECM development. These data, combined with the results of the Icam1tm1Jcgr and Icam1tm1Bay studies (Fig. 1), demonstrate that expression of different ICAM-1 isoforms results in dramatically different ECM phenotypes, suggesting distinct effector functions for a given isoform or combination of isoforms. These effector functions likely result from the integration of isoform-specific signaling pathways initiated by binding to single or multiple receptors. In the setting of ECM, we hypothesize that leukocyte/platelet/iRBC aggregates form in an ICAM-1-dependent fashion through use of β2-integrins (LFA-1 and Mac-1), which are then further stabilized by fibrinogen receptor binding (gpIIa/IIIb; CD41/CD61) on platelets. Such aggregates could form under the inflammatory conditions characteristic of malaria and CM and potentially occlude microvessels irrespective of the adhesive state of the endothelium. The powerfully protective effect of anti-LFA-1 treatment and in LFA-1-deficient mice in ECM suggests that LFA-1 is an important ICAM-1 counter receptor in aggregate formation (40–43). In addition, recent studies have suggested that blood brain barrier opening due to vascular leakage contributes significantly to the development of ECM (42). The data we report here suggest that both mechanisms may be simultaneously at work, with brain edema initiated and/or exacerbated by sporadic to widespread vessel occlusion. Taken together, our results indicate a more central role for ICAM-1 in CM than previously appreciated and suggest that ICAM-1-based therapeutics may be an effective treatment strategy in CM.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the support of Drs. Julian Rayner and Oliver Billker at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and the guidance and technical expertise of Dr. Robert Kesterson and the staff in the UAB Transgenic Mouse Facility. We acknowledge Pumba and David Summerford for continuing inspiration.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants T32 AI07051 (to T. N. R.), F31NS077811 (to T. N. R.), and P30 CA13148 and P30 AR048311. This work was also supported by National Multiple Sclerosis Society Grant PP1058 (to S. R. B. and D. C. B.).

- CM

- cerebral malaria

- ECM

- experimental cerebral malaria

- ICAM-1

- intercellular adhesion molecule-1

- iRBC

- infected RBC

- PbA

- P. berghei ANKA

- EAE

- experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis.

REFERENCES

- 1. van der Heyde H. C., Nolan J., Combes V., Gramaglia I., Grau G. E. (2006) A unified hypothesis for the genesis of cerebral malaria: sequestration, inflammation, and hemostasis leading to microcirculatory dysfunction. Trends Parasitol. 22, 503–508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Berendt A. R., Simmons D. L., Tansey J., Newbold C. I., Marsh K. (1989) Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 is an endothelial cell adhesion receptor for Plasmodium falciparum. Nature 341, 57–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Willimann K., Matile H., Weiss N. A., Imhof B. A. (1995) In vivo sequestration of Plasmodium falciparum-infected human erythrocytes: a severe combined immunodeficiency mouse model for cerebral malaria. J. Exp. Med. 182, 643–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Yipp B. G., Hickey M. J., Andonegui G., Murray A. G., Looareesuwan S., Kubes P., Ho M. (2007) Differential roles of CD36, ICAM-1, and P-selectin in Plasmodium falciparum cytoadherence in vivo. Microcirculation 14, 593–602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ockenhouse C. F., Betageri R., Springer T. A., Staunton D. E. (1992) Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocytes bind ICAM-1 at a site distinct from LFA-1, Mac-1, and human rhinovirus. Cell 68, 63–69 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Smith J. D., Craig A. G., Kriek N., Hudson-Taylor D., Kyes S., Fagan T., Pinches R., Baruch D. I., Newbold C. I., Miller L. H. (2000) Identification of a Plasmodium falciparum intercellular adhesion molecule-1 binding domain: a parasite adhesion trait implicated in cerebral malaria. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 1766–1771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tse M. T., Chakrabarti K., Gray C., Chitnis C. E., Craig A. (2004) Divergent binding sites on intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) for variant Plasmodium falciparum isolates. Mol. Microbiol. 51, 1039–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Springer T. A. (1994) Traffic signals for lymphocyte recirculation and leukocyte emigration: the multistep paradigm. Cell 76, 301–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Dustin M. L., Rothlein R., Bhan A. K., Dinarello C. A., Springer T. A. (1986) Induction by IL-1 and interferon, tissue distribution, biochemistry, and function of a natural adherence molecule (ICAM-1). J. Immunol. 137, 245–254 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Limb G. A., Webster L., Soomro H., Janikoun S., Shilling J. (1999) Platelet expression of tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), TNF receptors, and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1) in patients with proliferative diabetic retinopathy. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 118, 213–218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tailor A., Cooper D., Granger D. N. (2005) Platelet-vessel wall interactions in the microcirculation. Microcirculation 12, 275–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hunt N. H., Grau G. E. (2003) Cytokines: accelerators and brakes in the pathogenesis of cerebral malaria. Trends Immunol. 24, 491–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hafalla J. C., Silvie O., Matuschewski K. (2011) Cell biology and immunology of malaria. Immunol. Rev. 240, 297–316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dietrich J. B. (2002) The adhesion molecule ICAM-1 and its regulation in relation with the blood-brain barrier. J. Neuroimmunol. 128, 58–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ho M., Hickey M. J., Murray A. G., Andonegui G., Kubes P. (2000) Visualization of Plasmodium falciparum-endothelium interactions in human microvasculature: mimicry of leukocyte recruitment. J. Exp. Med. 192, 1205–1211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fernandez-Reyes D., Craig A. G., Kyes S. A., Peshu N., Snow R. W., Berendt A. R., Marsh K., Newbold C. I. (1997) A high frequency African coding polymorphism in the N-terminal domain of ICAM-1 predisposing to cerebral malaria in Kenya. Hum. Mol. Genet. 6, 1357–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Craig A., Fernandez-Reyes D., Mesri M., McDowall A., Altieri D. C., Hogg N., Newbold C. (2000) A functional analysis of a natural variant of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1Kilifi). Hum. Mol. Genet. 9, 525–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fry A. E., Auburn S., Diakite M., Green A., Richardson A., Wilson J., Jallow M., Sisay-Joof F., Pinder M., Griffiths M. J., Peshu N., Williams T. N., Marsh K., Molyneux M. E., Taylor T. E., Rockett K. A., Kwiatkowski D. P. (2008) Variation in the ICAM1 gene is not associated with severe malaria phenotypes. Genes Immunity 9, 462–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. King P. D., Sandberg E. T., Selvakumar A., Fang P., Beaudet A. L., Dupont B. (1995) Novel isoforms of murine intercellular adhesion molecule-1 generated by alternative RNA splicing. J. Immunol. 154, 6080–6093 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Giorelli M., De Blasi A., Defazio G., Avolio C., Iacovelli L., Livrea P., Trojano M. (2002) Differential regulation of membrane bound and soluble ICAM 1 in human endothelium and blood mononuclear cells: effects of interferon β-1a. Cell Commun. Adhes. 9, 259–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Werner A., Martin S., Gutierrez-Ramos J. C., Raivich G. (2001) Leukocyte recruitment and neuroglial activation during facial nerve regeneration in ICAM-1-deficient mice: effects of breeding strategy. Cell Tissue Res. 305, 25–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ochietti B., Lemieux P., Kabanov A. V., Vinogradov S., St-Pierre Y., Alakhov V. (2002) Inducing neutrophil recruitment in the liver of ICAM-1-deficient mice using polyethyleneimine grafted with Pluronic P123 as an organ-specific carrier for transgenic ICAM-1. Gene Ther. 9, 939–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. van Den Engel N. K., Heidenthal E., Vinke A., Kolb H., Martin S. (2000) Circulating forms of intercellular adhesion molecule (ICAM)-1 in mice lacking membranous ICAM-1. Blood 95, 1350–1355 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Robledo O., Papaioannou A., Ochietti B., Beauchemin C., Legault D., Cantin A., King P. D., Daniel C., Alakhov V. Y., Potworowski E. F., St-Pierre Y. (2003) ICAM-1 isoforms: specific activity and sensitivity to cleavage by leukocyte elastase and cathepsin G. Eur. J. Immunol. 33, 1351–1360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dunne J. L., Collins R. G., Beaudet A. L., Ballantyne C. M., Ley K. (2003) Mac-1, but not LFA-1, uses intercellular adhesion molecule-1 to mediate slow leukocyte rolling in TNF-α-induced inflammation. J. Immunol. 171, 6105–6111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xu H., Gonzalo J. A., St Pierre Y., Williams I. R., Kupper T. S., Cotran R. S., Springer T. A., Gutierrez-Ramos J. C. (1994) Leukocytosis and resistance to septic shock in intercellular adhesion molecule 1-deficient mice. J. Exp. Med. 180, 95–109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Sligh J. E., Jr., Ballantyne C. M., Rich S. S., Hawkins H. K., Smith C. W., Bradley A., Beaudet A. L. (1993) Inflammatory and immune responses are impaired in mice deficient in intercellular adhesion molecule 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 90, 8529–8533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zhumabekov T., Corbella P., Tolaini M., Kioussis D. (1995) Improved version of a human CD2 minigene based vector for T cell-specific expression in mice. J. Immunol. Methods 185, 133–140 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chewning J. H., Dugger K. J., Chaudhuri T. R., Zinn K. R., Weaver C. T. (2009) Bioluminescence-based visualization of CD4 T cell dynamics using a T lineage-specific luciferase transgenic model. BMC Immunol. 10, 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Sinden R. E., Butcher G. A., Beetsma A. L. (2002) Maintenance of the Plasmodium berghei life cycle. Methods Mol. Med. 72, 25–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ramos T. N., Darley M. M., Weckbach S., Stahel P. F., Tomlinson S., Barnum S. R. (2012) The C5 convertase is not required for activation of the terminal complement pathway in murine experimental cerebral malaria. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 24734–24738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Cox M. A., Barnum S. R., Bullard D. C., Zajac A. J. (2013) ICAM-1-dependent tuning of memory CD8 T-cell responses following acute infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 1416–1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wohler J. E., Smith S. S., Zinn K. R., Bullard D. C., Barnum S. R. (2009) γδ T cells in experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis: early trafficking events and cytokine requirements. Eur. J. Immunol, 39, 1516–1526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Favre N., Da Laperousaz C., Ryffel B., Weiss N. A., Imhof B. A., Rudin W., Lucas R., Piguet P. F. (1999) Role of ICAM-1 (CD54) in the development of murine cerebral malaria. Microbes Infect. 1, 961–968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Steeber D. A., Venturi G. M., Tedder T. F. (2005) A new twist to the leukocyte adhesion cascade: intimate cooperation is key. Trends Immunol. 26, 9–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. von Andrian U. H., Mackay C. R. (2000) T-cell function and migration. Two sides of the same coin. N. Engl. J. Med. 343, 1020–1034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Liu L., Kubes P. (2003) Molecular mechanisms of leukocyte recruitment: organ-specific mechanisms of action. Thromb. Haemost. 89, 213–220 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Springer T. A. (1990) Adhesion receptors of the immune system. Nature 346, 425–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hu X., Barnum S. R., Wohler J. E., Schoeb T. R., Bullard D. C. (2010) Differential ICAM-1 isoform expression regulates the development and progression of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Mol. Immunol. 47, 1692–1700 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Grau G. E., Pointaire P., Piguet P. F., Vesin C., Rosen H., Stamenkovic I., Takei F., Vassalli P. (1991) Late administration of monoclonal antibody to leukocyte function-antigen 1 abrogates incipient murine cerebral malaria. Eur. J. Immunol. 21, 2265–2267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Falanga P. B., Butcher E. C. (1991) Late treatment with anti-LFA-1 (CD11a) antibody prevents cerebral malaria in a mouse model. Eur. J. Immunol. 21, 2259–2263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Nacer A., Movila A., Baer K., Mikolajczak S. A., Kappe S. H., Frevert U. (2012) Neuroimmunological blood brain barrier opening in experimental cerebral malaria. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ramos T. N., Bullard D. C., Barnum S. R. (2012) Deletion of the complement phagocytic receptors CR3 and CR4 does not alter susceptibility to experimental cerebral malaria. Parasite Immunol. 34, 547–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]