Background: The TP0796 lipoprotein of Treponema pallidum belongs to the poorly characterized ApbE superfamily.

Results: TP0796 hydrolyzed FAD into FMN and AMP, consistent with the general enzymatic mechanism of an FAD pyrophosphatase.

Conclusion: This novel metal-dependent enzyme probably plays an essential role in flavin homeostasis in T. pallidum.

Significance: This is the first description of a metal-dependent FAD pyrophosphatase in bacteria.

Keywords: Enzyme Structure, FAD, Flavin, Flavoproteins, Protein Structure, FAD Pyrophosphatase, Treponema pallidum, Flavin Turnover, Lipoprotein, Syphilis

Abstract

Treponema pallidum, an obligate parasite of humans and the causative agent of syphilis, has evolved the capacity to exploit host-derived metabolites for its survival. Flavin-containing compounds are essential cofactors that are required for metabolic processes in all living organisms, and riboflavin is a direct precursor of the cofactors FMN and FAD. Unlike many pathogenic bacteria, Treponema pallidum cannot synthesize riboflavin; we recently described a flavin-uptake mechanism composed of an ABC-type transporter. However, there is a paucity of information about flavin utilization in bacterial periplasms. Using a discovery-driven approach, we have identified the TP0796 lipoprotein as a previously uncharacterized Mg2+-dependent FAD pyrophosphatase within the ApbE superfamily. TP0796 probably plays a central role in flavin turnover by hydrolyzing exogenously acquired FAD, yielding AMP and FMN. Biochemical and structural investigations revealed that the enzyme has a unique bimetal Mg2+ catalytic center. Furthermore, the pyrophosphatase activity is product-inhibited by AMP, indicating a possible role for this molecule in modulating FMN and FAD levels in the treponemal periplasm. The ApbE superfamily was previously thought to be involved in thiamine biosynthesis, but our characterization of TP0796 prompts a renaming of this superfamily as a periplasmic flavin-trafficking protein (Ftp). TP0796 is the first structurally and biochemically characterized FAD pyrophosphate enzyme in bacteria. This new paradigm for a bacterial flavin utilization pathway may prove to be useful for future inhibitor design.

Introduction

Treponema pallidum, the bacterial agent of syphilis, is an obligate parasite of humans (1, 2). As part of its infection strategy, T. pallidum has evolved the capacity to exploit many host-derived metabolites for its survival. Consistent with this, T. pallidum lacks many of the genes typically involved in the biosynthetic pathways for fatty acids, nucleotides, most of the amino acids, and many other vital metabolites (3, 4). As such, the organism depends primarily on an extracellular supply of nutrients, such as glucose, purines, amino acids, and fatty acids as well as cofactors and vitamins that are abundantly available in the human host. The mechanism(s) by which the parasite acquires and utilizes these essential nutrients can potentially help explain the peculiar membrane biology of T. pallidum, elucidate key aspects of its parasitic strategy, and prompt new avenues of investigation for potentially novel antimicrobial drug targets. To this end, we have found that many of the likely transport systems of T. pallidum are predicated on the organism's membrane lipoproteins (5–13), and, as a result, the organism devotes a large percentage of its genome to encoding these lipoproteins (3, 14, 15). Unfortunately, many of the putative lipoproteins are hypothetical (i.e. they have no known or predicted functions) (3). Inasmuch as T. pallidum still cannot be cultivated in vitro (growth is achieved in laboratory rabbits), approaches to discern the functions of T. pallidum proteins and lipoproteins are severely limited. Given this constraint, we have been exploiting a “structure-to-function” approach to study uncharacterized lipoproteins of T. pallidum. Bioinformatics, combined with structural, biochemical, and biophysical studies on recombinant versions of the lipoproteins, are being employed to gain deeper insights into the molecular mechanisms and biological functions of these lipoproteins in the context of treponemal survival in the human host (5–10, 12, 13).

Although primary sequence homologies can be useful for inferring the biochemical functions of homologous proteins, they have had relatively little impact on predicting the functions of treponemal lipoproteins (5, 6, 8–10, 12, 13). However, examining the functions of homologs to treponemal proteins can provide initial guidance for further biochemical characterizations. For example, based on BLAST analysis, the TP0796 lipoprotein from T. pallidum is classified as a putative member of the ApbE superfamily (Pfam02424). This prokaryotic family of proteins is related to the periplasmic ApbE lipoprotein of Salmonella typhimurium (16, 17). In S. typhimurium, ApbE has been shown to be involved in thiamine biosynthesis and may serve in the conversion of aminoimidazole ribotide to 4-amino-5-hydroxymethyl-2-methylpyrimidine (16). T. pallidum is predicted to lack the thiamine pathway as well as the enzymes involved in aminoimidazole ribotide metabolism (3, 4, 18). Second, the periplasmic location of ApbE prompts questions concerning how it could participate in a cytoplasmic pathway. Third, ApbE proteins are relatively understudied biochemically, and representative crystal structures (PDB3 entries 1VRM and 2O18) have failed to definitively elucidate their functions. A recent crystal structure of the Salmonella enterica homolog of TP0796 (ApbE_Se), classified it merely as an FAD-binding protein (19).

These intriguing information gaps regarding TP0796 and ApbE-like proteins piqued our interest in TP0796 as a putative ApbE homolog. As an initial approach, we cloned, expressed, and purified TP0796 that had been heterologously hyperexpressed. We then determined the crystal structures of recombinant TP0796 with constitutively bound Mg2+, in a substrate complex with Mg2+-FAD, in a product complex with Mg2+-AMP, or in an inhibitor complex with Mg2+-ADP. Crystallographic and solution biochemical analyses revealed TP0796 to be a previously uncharacterized Mg2+-dependent FAD pyrophosphatase that hydrolyzed FAD into AMP and FMN. Although ApbE family members have been predicted to bind FAD, none have been reported to hydrolyze it. Moreover, whereas the FAD biosynthetic pathway in bacteria has been well characterized, there is a paucity of information regarding bacterial FAD degradation pathways. Thus, the FAD pyrophosphatase activity of TP0796 is potentially to generate a flavin pool via its product inhibition mechanism (by AMP), probably playing an important role in flavoprotein biogenesis. Our combined studies have allowed us to present a new conceptual flavin turnover model that serves to satisfy flavin cofactor requirements within the bacterial periplasm.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

Unless otherwise noted, all chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or Hampton Research.

Protein Preparation

A DNA fragment corresponding to amino acids 2–340 (without the lipid-modified N-terminal Cys residue; the numbering reflects the assignment of this Cys as residue 1 of the processed protein) of the mature form of TP0796 from T. pallidum was generated by PCR amplification of T. pallidum genomic DNA using primers with flanking restriction sites for BsaI and XbaI. The digested PCR fragment was ligated into the pE-SUMOpro fusion vector with kanamycin resistance (LifeSensors), which had been digested with the same two enzymes, to generate the expression vector. The plasmid was then transformed into Escherichia coli BL21 (DE3). Bacteria were grown at 37 °C in LB medium supplemented with 40 μg/ml kanamycin until the A600 reached ∼0.5. Isopropyl 1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside was added to a final concentration of 0.6 mm for 3 h to induce expression of the recombinant protein. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in the lysis buffer (50 mm NaPi, pH 8.0, 0.2 m NaCl, 10 mm imidazole), and lysed by sonication (6). The supernatant was applied to a 4-ml Ni2+-agarose column (Qiagen), immobilizing the tagged protein. The elution of the TP0796 followed a previously developed methodology (8). The eluted protein was further purified by size exclusion chromatography on a Superdex 200 (16/60) column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with buffer A (20 mm Hepes, pH 7.5, 0.1 m NaCl, 2 mm β-octyl glucoside). Pooled fractions were digested with SUMO protease 1 (LifeSensors) to remove the His-SUMO tag, and the digestion mixture was separated by size exclusion chromatography (described above).

The purity of the eluted fractions was determined by SDS-PAGE. Fractions containing pure TP0796 were pooled and concentrated using an Amicon Ultra filter device (Millipore) to ∼10 mg/ml for crystallization and biochemical analyses. Protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically using an extinction coefficient of 21,680 m−1 cm−1 at 280 nm, which was calculated using the ProtParam utility of ExPASy.

The E. coli ApbE (ApbE_Ec) fusion construct (in pET-21 NESG vector) was obtained from the DNASU plasmid repository. The plasmid was transformed into E. coli BL21 (DE3), and the recombinant protein was hyperproduced as described above. Both liganded and ligand-free ApbE_Ec were prepared as described for PnrA (8). The concentration was determined at 280 nm using an extinction coefficient of 46,410 m−1 cm−1 (calculated as above). All purified proteins were stored at 4 °C and were stable for 2 weeks.

Crystallization and Data Collection

All crystals were obtained using the hanging drop vapor diffusion method. One small plate crystal of apo-TP0796 (no bound nucleotide) appeared in 7 weeks in 0.7 m sodium acetate, 0.1 m sodium cacodylate (pH 6.5) at 20 °C. The crystal was cryoprotected by successive transfer over the course of 10 min at 20 °C in increasing steps of 5% ethylene glycol to a final solution of 20% (v/v) ethylene glycol, 0.1 m MES (pH 6.5), 0.8 m sodium acetate, 0.1 m NaCl. The crystal was mounted into a nylon loop, flash-cooled in liquid nitrogen, and then used for data collection. TP0796 crystals exhibited the symmetry of space group C2 with unit cell parameters of a = 117.6 Å, b = 47.3 Å, c = 57.6 Å, and β = 102.4° and contained one molecule of TP0796 per asymmetric unit and ∼40% solvent. The crystals of ternary complexes were routinely obtained in 2–3 days by co-crystallizing TP0796 in the presence of a 5 mm concentration of the chloride salt of the divalent metal ion and 5 mm AMP or ADP using 0.1 m MES (pH 6.5), 0.7 m sodium acetate as precipitant; these co-crystals were isomorphous to the apo-crystals. The complex crystals were generally larger than the apo-crystal and were cryoprotected as above for data collection with a final concentration of 35% ethylene glycol. The crystals for the FAD-Mg2+ complex were obtained by the addition of 5 mm FAD to the protein prior to crystallization, with no added Mg2+ ion. Data for the Mn2+-AMP complex were collected using incident radiation at the manganese K-absorption edge. Data were indexed, integrated, and scaled using the HKL-3000 program package (20). Data collection statistics are provided in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Data collection, phasing, and refinement statistics for TP0796 structures

Data for the outermost shell are given in parentheses. NA, not applicable.

| Data collection | |||||

| Crystal | Apo | FAD-Mg2+ | AMP-Mg2+ | AMP-Mn2+ | ADP-Mg2+ |

| Energy (eV) | 12,684.5 | 12,684.1 | 12,804.1 | 8,280.4 | 12,684.1 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 36.6–1.83 (1.86–1.83) | 28.6–1.45 (1.48- 1.45) | 28.6–1.45 (1.48–1.45) | 35.8–1.90 (1.93–1.90) | 36.5–2.30 (2.34–2.30) |

| Unique reflections | 27,231 (1,354) | 53,215 (2,571) | 53,906 (2,616) | 24,023 (1,156) | 13,766 (667) |

| Multiplicity | 4.0 (3.9) | 4.0 (3.3) | 4.9 (3.9) | 6.0 (5.9) | 3.9 (3.4) |

| Data completeness (%) | 99.7 (99.9) | 98.4 (95.3) | 99.4 (96.7) | 99.4 (98.6) | 99.0 (94.9) |

| Rmerge (%)a | 7.6 (57.4) | 4.0 (62.8) | 6.0 (55.9) | 4.6 (23.2) | 13.4 (38.8) |

| I/σ(I) | 18.4 (2.0) | 33.0 (1.79) | 19.5 (1.88) | 42.1 (7.16) | 8.9 (1.94) |

| Wilson B-value (Å2) | 19.1 | 17.4 | 16.0 | 20.4 | 18.3 |

| Refinement statistics | |||||

| Crystal | Apo | FAD-Mg2+ | AMP-Mg2+ | AMP-Mn2+ | ADP-Mg2+ |

| Resolution range (Å) | 28.8–1.83 (1.89–1.83) | 28.6–1.45 (1.49–1.45) | 28.6–1.43 (1.46–1.43) | 29.6–1.90 (1.99–1.90) | 29.7–2.30 (2.48–2.30) |

| No. of reflections Rwork/Rfree | 27,219/1,364 (2,446/129) | 50,440/2,687 (3,488/195) | 53,888/2,731 (808/43) | 24,011/1,187 (2,762/141) | 13,721/673 (2,518/135) |

| Data completeness (%) | 99.4 (96.0) | 98.0 (92.4) | 96.0 (31.0) | 99.3 (98.0) | 98.7 (96.0) |

| Atoms (non-hydrogen protein/solvent/metals/nucleotide) | 2,538/169/1/0 | 2,610/256/2/53 | 2,594/264/2/23 | 2,601/160/2/23 | 2,501/161/2/27 |

| Rwork (%) | 16.9 (21.6) | 17.2 (30.2) | 17.7 (29.8) | 15.9 (15.3) | 17.7 (21.3) |

| Rfree (%) | 21.7 (26.4) | 20.3 (32.4) | 21.1 (35.4) | 20.3 (21.6) | 23.8 (28.9) |

| r.m.s. deviation, bond length (Å) | 0.018 | 0.022 | 0.014 | 0.015 | 0.013 |

| r.m.s. deviation, bond angle (degrees) | 1.28 | 2.23 | 1.28 | 1.27 | 0.80 |

| Mean B-value (Å2) (protein/solvent/metals/nucleotide) | 28.4/31.8/11.6/NA | 25.1/32.0/19.7/35.0 | 25.4/36.7/19.8/15.7 | 30.1/32.0/16.4/16.7 | 19.2/22.9/14.8/14.7 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) (favored/additional/disallowed)b | 99.4/0.6/0.0 | 98.2/0.9/0.9 | 98.5/1.2/0.3 | 97.6/2.1/0.3 | 97.5/2.5/0.0 |

| Maximum likelihood coordinate error | 0.19 | 0.05 | 0.14 | 0.17 | 0.25 |

| Missing residues | 2–4, 201–206 | 2–4, 201–206 | 2–7, 201–206 | 2–4, 201–206 | 2–5, 114–115, 201–206 |

a Rmerge = 100 ΣhΣi|Ih,i − 〈Ih〉|/ΣhΣiIh,i, where the outer sum (h) is over the unique reflections and the inner sum (i) is over the set of independent observations of each unique reflection.

b As defined by the validation suite MolProbity (28).

Phase Determination and Structure Refinement

Phases for apoTP0796 were obtained via the molecular replacement method in the program Phaser (21) using suitably edited coordinates for the Thermatoga maritima tm1553 homolog (18) (PDB entry 1VRM) with data to a resolution of 3.5 Å. Phases were improved via density modification with the program Parrot (22), resulting in an overall figure of merit of 0.49 for data between 36.6 and 1.83 Å. An initial model containing about 93% of all residues was automatically generated by multiple alternating cycles of the programs Buccaneer (23) and ARP/wARP (24), followed by improved density modification in Parrot.

Additional residues were manually modeled in the programs O (25) and Coot (26). Refinement was performed with data to a resolution of 1.83 Å using the program Phenix (27), with a random 5% of all data set aside for an Rfree calculation; riding hydrogens were included. The current model for apo-TP0796 contains one monomer; included are residues 5–200, 207–340, one Mg2+ ion, and 169 waters. The Rwork is 0.169, and the Rfree is 0.217. A Ramachandran plot generated with MolProbity (28) indicated that 99.4% of all protein residues are in the most favored regions, with the remaining 0.6% in additionally allowed regions. Refinement of the complex structures was carried out in a similar manner, with the exception that the Mg2+-FAD complex was refined in Refmac (29). Model refinement statistics are provided in Table 1.

Accession Codes

The coordinates and structure factors for apo-TP0796 (4IFU), and its complexes (4IG1, the Mg2+-AMP complex; 4IFZ, the Mn2+-AMP complex; 4IFX, the FAD complex; and 4IFW, the ADP complex) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank.

FAD Pyrophosphatase Activity of TP0796

Flavin stock solutions were prepared in MilliQ (Millipore) water and stored at −20 °C. The concentrations of flavin solutions were determined spectrophotometrically using extinction coefficients (ϵ450 = 11.3 mm−1 cm−1 for FAD and 12.2 mm−1 cm−1 for FMN) (30, 31).

The assay for FAD pyrophosphatase (EC 3.6.1.18) activity was adapted from the method of Forti and Sturani (32). It exploits the fact that fluorescence of FMN is higher than that of an FAD solution of the same concentration and that pyrophosphatase catalyzes the conversion of FAD to FMN and AMP. Thus, FAD hydrolysis (or FMN formation) was monitored using a differential fluorescence (ΔF, expressed in arbitrary relative fluorescence units (RFU)) assay on a Tecan plate reader (Tecan). The ΔF was calculated from the expression, ΔF = FTP0796 − FFAD, where ΔF is the fluorescence change due to the product formation, FTP0796 is the fluorescence generated by TP0796, and FFAD is the fluorescence of FAD. We set up 200-μl reactions in 96-well plates with 1 μm enzyme in buffer A and 5 mm MgCl2, and allowed the reactions to incubate at 37 °C. After 10 min of incubation, 10 μm FAD was added, and the reactions were allowed to incubate for an additional 5 min at 37 °C. Increasing fluorescence intensity was monitored at excitation and emission wavelengths of 430 and 510 nm, respectively, with a gain setting of 60, and at room temperature. Data for all experiments were collected in duplicate or triplicate, and the background signal, which constitutes the reaction mixture without enzyme, was subtracted.

Activity was also measured with various divalent metal cations in the reaction buffer. To determine the pH dependence of the reaction, individual assays were performed in 50 mm BIS-TRIS propane containing 0.1 m NaCl at various pH values.

Inhibition Studies

Inhibition was assayed by incubating the enzyme reaction mixture either with 1 mm AMP, ADP, or ATP prior to the addition of FAD. EDTA inhibition was examined by adding 5 mm EDTA prior to the addition of metal cofactor to the reaction mixture.

Quantitation of FMN

FMN fluorescence values were quantitated on the basis of an FMN standard curve. The standard curve was prepared by measuring the fluorescence emission of a solution containing increasing concentrations of FMN in buffer A. Based on measurements of FMN standards, 1 μm FMN was assumed to be equivalent to 700 RFU.

Thin Layer Chromatography (TLC) Analysis

TLC of the products of FAD hydrolysis by TP0796 was performed on plates of silica gel (20 × 20 cm; thickness, 0.25 mm; pore size, 60 Å; Sigma) (33, 34). For TLC analysis, reactions were performed in buffer A as described for the enzyme assay, except that 20 μm protein was incubated with 50 μm FAD. Following incubation at 37 °C, the reactions were boiled for 10 min and centrifuged to remove protein precipitates. Approximately 20 μl of the yellow supernatant was applied to the TLC plate. Equal volumes of individual flavin-containing standards were loaded at concentrations of 50 μm, and the plate was allowed to air-dry. The mobile phase was a solution of butanol/acetic acid/water (12:3:5) and developed for 6 h at room temperature. The fluorescence of flavin-containing compounds on air-dried TLC plates was photographed with UV illumination and compared with the standards. Some FMN bands were scraped from the TLC plate and extracted with 50% (v/v) ethanol for MALDI-TOF mass analyses.

FAD Binding Activity

Ligand-free ApbE_Ec was prepared by an on-column denaturation/renaturation method (8). To determine the FAD binding affinity to the ligand-free protein, changes in fluorescence (ΔF) upon binding of different concentrations of FAD were measured (as described above), and the binding affinity was calculated using the GraphPad software. The relative ΔF at emission wavelength of 510 nm upon FAD binding was defined as ΔF = FFAD − FApbE, where ΔF is the changes in fluorescence due to FAD binding, FFAD is fluorescence of the added FAD, and FApbE is the fluorescence upon FAD binding to the ApbE protein. The experiment was performed as described above for the enzyme assay by incubating a 1 μm concentration of ligand-free ApbE with 0.00, 0.05, 0.10, 0.30, 0.50, 1.00, 2.00, 5.00, or 10 μm FAD. Titrations in the absence of protein were performed as a reference.

Analytical Ultracentrifugation

All analytical ultracentrifugation studies were performed at 4 °C in a Beckman-Coulter Optima XL-I centrifuge. TP0796 or ApbE_Ec was diluted to the experimental concentration with Buffer A. The protein solution was injected into an assembled ultracentrifugation cell that featured a charcoal-filled Epon centerpiece sandwiched between two sapphire windows. The cells were placed in an An50-Ti rotor (Beckman-Coulter, Indianapolis, IN) and allowed to incubate at the experimental temperature under vacuum overnight. Centrifugation at 50,000 rpm was commenced and continued until the sedimentation was complete (∼9 h). Absorbance optics were used to acquire radial concentration profiles at a wavelength of 280 nm from the cells at an ∼10-min interval. These data were analyzed using the continuous c(s) model (35, 36) in SEDFIT. The figure derived from this analysis was made using GUSSI.

In Vivo Cross-linking of Associated Proteins

Treponemal protein cross-linking was performed according to the method described previously (12, 37). Briefly, ∼1 × 108 freshly harvested bacteria from rabbit tissue in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) were incubated with 1% (v/v) methanol-free formaldehyde (Thermo Scientific) for 90 min at room temperature with gentle rocking. To stop the cross-linking reaction, glycine was added to a final concentration of 125 mm and incubated for 5 min at room temperature. A control reaction was performed similarly but without adding formaldehyde. Both cross-linked and non-cross-linked treponemes were harvested by centrifugation at 16,000 × g and rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS to remove excess unreacted cross-linker. They were frozen at −70 °C until needed for analysis. Cross-linked complexes were detected by immunoblotting with TP0796-specific antibodies (12). Antiserum recognizing TP0796 was obtained from rats by injecting purified recombinant antigens. Antibodies from the antiserum were then affinity-purified using an antibody purification kit (Thermo Scientific). The specificity of the purified antibodies was documented against recombinant test and control antigens (not shown).

RESULTS

Purification and Biophysical Properties of the Proteins

Recombinant TP0796 and ApbE_Ec were hyperexpressed in E. coli and purified to homogeneity. Unlike the TP0796 solution, the solution containing ApbE_Ec was bright yellow, suggesting that the protein bound a flavin-containing compound. Further, this yellow protein solution displays a UV-visible flavin spectrum that was characteristic for flavin-containing molecules (not shown).

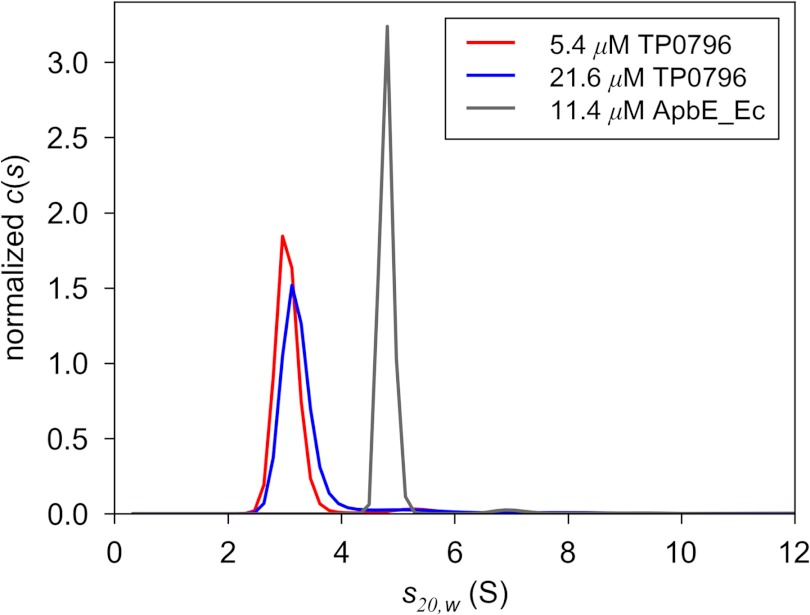

To investigate the oligomeric statuses of both TP0796 and ApbE_Ec, analytical ultracentrifugation was performed. Sedimentation velocity demonstrated that ApbE_Ec was a dimer under our solution conditions but that TP0796 was mostly monomeric (Fig. 1). The estimated molar mass of AbpE_Ec was 77,900 g/mol; this value is consistent with a dimer of the protein, which was expected to be 75,206 g/mol. The sedimentation coefficient of ApbE_Ec (s20,w = 4.8 S) was insensitive to varying its concentration. TP0796, however, had a significantly smaller s-value (s20,w ∼3.1 S) and estimated molar mass (32,700 g/mol). The expected molar mass for a monomer of TP0796 calculated from its sequence is 36,593 g/mol. Thus, the majority of the protein is monomeric. However, there is a weak tendency for the sedimentation coefficient to increase with increasing concentrations of TP0796 (Fig. 1). This observation indicates that TP0796 apparently dimerizes under our solution conditions, but the dimerization constant must be very high (≫20 μm).

FIGURE 1.

Hydrodynamic behavior of TP0796 and ligand-bound ApbE_Ec. Shown are c(s) distributions for two concentrations (5.4 and 21.6 μm, red and blue lines, respectively) of TP0796 and one (gray line) of ApbE_Ec. The distributions have been normalized by the total amount of absorbance found in each respective experiment.

TP0796 Apo-structure

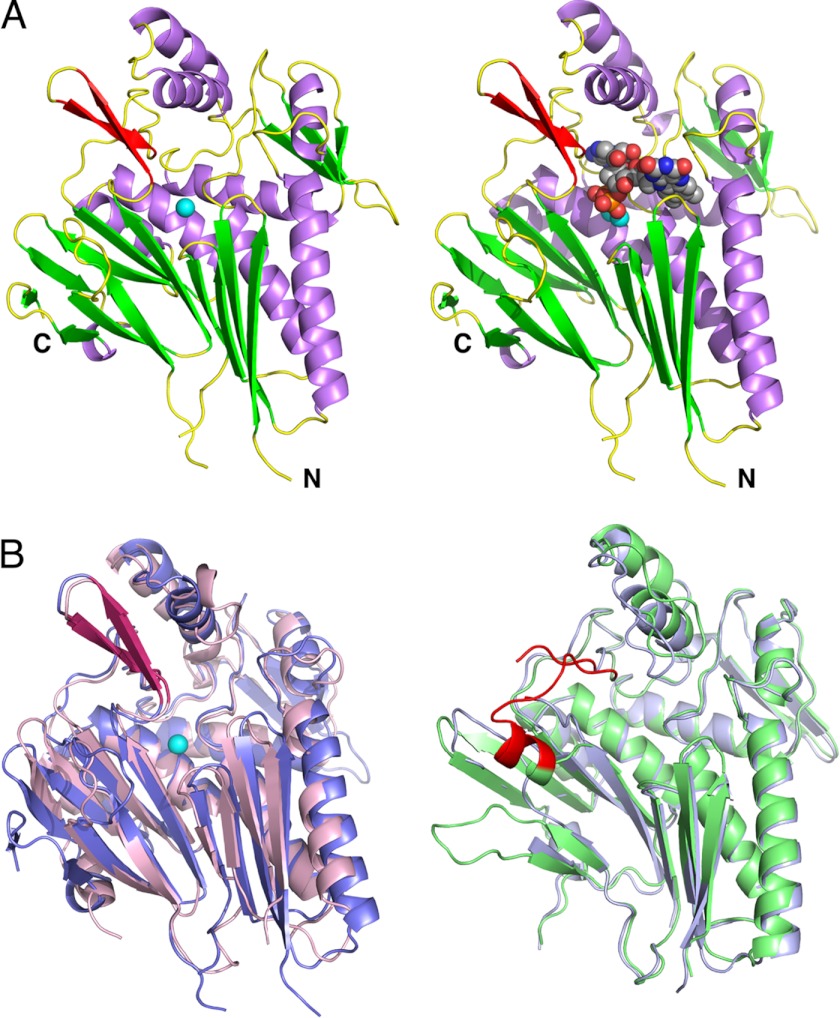

The crystal structure of apo-TP0796 (Fig. 2A) demonstrates that it adopts the canonical ApbE superfamily fold observed in the previously determined structural homologs from S. enterica, T. maritima (18, 19), and E. coli (PDB entry 2O18). Whereas ApbE_Se and ApbE_Ec are dimers in the solid state, TP0796 is a monomer in the crystalline lattice as determined via analysis with the Protein Interfaces, Surfaces, and Assemblies Service (PISA) at the European Bioinformatics Institute (38, 39), a distinction it shares with T. maritima ApbE (ApbE_Tm), with which it shares the highest primary sequence homology (32%).

FIGURE 2.

TP0796 belongs to the ApbE superfamily. A, shown on the left is the structure of apo-TP0796, with helices in lavender, β-strands in green, and loops in yellow. The β-hairpin loop insert to the canonical ApbE fold is shown in red, and the bound Mg2+ ion is a cyan sphere. On the right is the FAD-Mg2+-bound TP0796 model, with the FAD represented as spheres and the two Mg2+ ions as cyan spheres. B, superpositions of the two subgroups of the ApbE superfamily. On the left is the structure of apo-TP0796 in slate blue superimposed with ApbE_Tm in pink. The β-hairpin loop insert is shown in red, and the Mg2+ ion is a cyan sphere. On the right is ApbE_Se in light green superimposed with ApbE_Ec in light blue. The regions that correspond to the β-hairpin loop insert in TP0796 are shown in red.

Structure-based sequence alignments of TP0796 to the ApbE homologs (Table 2) reveal that they cluster into two closely related subgroups (Fig. 2B and supplemental Fig. 1). TP0796 and ApbE_Tm both contain an additional β-hairpin loop not found in the ApbE_Se and ApbE_Ec structures. This β-hairpin loop, which comprises residues 244–256 in TP0796, positions several residues close to the respective nucleotide-binding sites in these proteins. The analogous regions of polypeptide in the proteins of the other subgroup are either a long, flexible, and partially disordered loop in the ApbE_Ec structure or a helix and long flexible loop in the ApbE_Se structure, in which these residues are not in close proximity to the respective ligand-binding sites. The Desulfovibrio vulgaris Hildenborough hypothetical protein adopts an ApbE-like fold but appears to retain only 60% of the secondary structural elements found in the other homologs. For this reason, at present we do not consider this protein to be a true member of the ApbE family.

TABLE 2.

Native TP0796 alignments to ApbE homologs

All alignments were performed using the Dalilite server.

| Organism | PDB entrya | Resolution | Sequence ID | r.m.s. deviation | C-α atomsb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Å | % | Å | |||

| T. maritima | 1VRM | 1.58 | 32 | 2.0 | 298 |

| E. coli | 2O18 | 2.20 | 24 | 2.3 | 286 |

| S. enterica | 3PND | 2.75 | 25 | 2.5 | 295 |

| D. vulgaris | 2O34 | 1.95 | 18 | 2.8 | 186 |

a Chain A for each ApbE homolog was used for alignment to TP0796.

b Number of C-α atoms aligned.

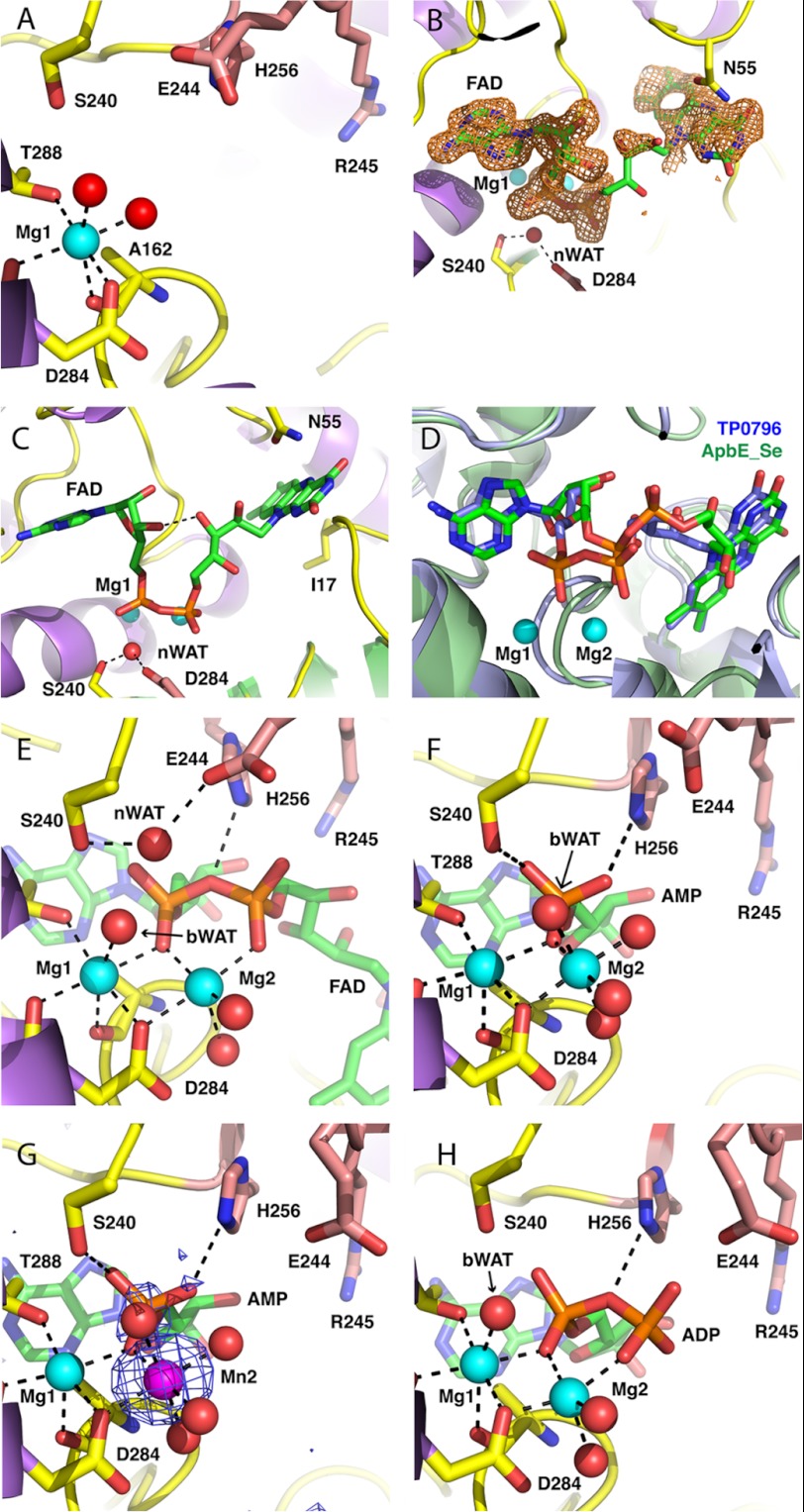

Inspection of the electron density map for apo-TP0796 revealed an atom octahedrally coordinated to the OD1 carboxylate and main-chain oxygens of Asp284, the main-chain oxygen of Ala162, the OG1 oxygen of Thr288, and two water molecules (Fig. 3A). This atom has been assigned as a Mg2+ ion due to the coordination geometry, the nature of the coordinated ligands, the average bond distance of 2.3 Å (Table 3), and the refined electron density. These geometric parameters correspond well with those found for crystallographically refined Mg2+ ions in other protein structures (40, 41). The metal-binding residues Asp284 and Thr288 are conserved across the ApbE structural homologs. The presence of the bound metal ion in the structure was unexpected because Mg2+ was not specifically added to the apoprotein during purification or crystallization. The region in the apo-TP0796 structure that has been identified as an FAD binding site in ApbE_Se is occupied by water molecules, with no clear pattern that might indicate any other type of bound ligand. This corresponds with the observation that the TP0796 protein used for crystallization screening was colorless upon purification.

FIGURE 3.

Coordination about the bimetal active site in TP0796 structures. The carbon atoms of protein side chains are yellow, the carbon atoms from residues of the β-hairpin insert are salmon, the FAD is green, Mg2+ ions are cyan spheres, the Mn2+ ion is a magenta sphere, waters are red spheres, nitrogens are blue, and oxygens are red. Black dotted lines represent metal first coordination spheres and important hydrogen-bonding interactions. The candidate nucleophilic water is labeled nWAT, and the bridging water is labeled bWAT. For clarity, some protein residues have been selectively removed from the images. A, metal site 1 (Me1) in apo-TP0796. B, omit electron density around FAD ligand. Shown in orange mesh is the |Fo − Fc| omit electron density, contoured at the 2σ level and superimposed on the FAD of the FAD-Mg2+ TP0796 structure. The map was calculated by omitting the FAD from the model and conducting three rounds of maximum likelihood positional and B-factor refinement. C, bent conformation of the substrate in the FAD-Mg2+-bound TP0796. D, superposition of the FAD-Mg2+-bound TP0796 (blue carbon atoms) and FAD-bound Apbe_Se (green carbon atoms). E, FAD-Mg2+-bound TP0796. F, AMP-Mg2+-bound TP0796. G, AMP-Mg2+-Mn2+-bound TP0796. Superimposed on the atoms is the anomalous difference map, contoured at the 3σ level, calculated from data collected at the manganese K-absorption edge. H, ADP-Mg2+-bound TP0796.

TABLE 3.

Active site geometric parameters for TP0796 structures

| Apo | FAD-Mg2+ | AMP-Mg2+ | AMP-Mn2+ | ADP-Mg2+ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolution (Å) | 1.83 | 1.48 | 1.45 | 1.90 | 2.30 |

| Me1 identitya | Mg2+ | Mg2+ | Mg2+ | Mg2+ | Mg2+ |

| Me1 B-factor (Å2) | 11.6 | 15.1 | 15.2 | 14.1 | 3.2 |

| Me2 identity | Mg2+ | Mg2+ | Mn2+ | Mg2+ | |

| Me2 B-factor (Å2) | 24.3 | 16.8 | 18.7 | 26.4 | |

| Me1 C.N.b | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 6 |

| Me2 C.N. | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | |

| Bond distances (Å) | |||||

| Me1--Me2 | 3.30 | 3.14 | 3.24 | 3.27 | |

| Me1--T284OD1 | 2.42 | 2.32 | 2.31 | 2.32 | 2.42 |

| Me1--T284O | 2.38 | 2.30 | 2.26 | 2.24 | 2.26 |

| Me1--A162O | 2.45 | 2.51 | 2.42 | 2.41 | 2.47 |

| Me1--T288OG1 | 2.38 | 2.40 | 2.29 | 2.31 | 2.39 |

| Me1--bWATc | 2.21 | 2.50 | 3.99d | 3.64 | 2.23 |

| Me1--H2O | 2.20 | ||||

| Me1–αPiO | 2.34 | 2.33 | 2.23 | 2.21 | |

| Average Me1 distances | 2.34 | 2.40 | 2.32 | 2.30 | 2.33 |

| Me2--T284OD1 | 2.34 | 2.10 | 2.15 | 2.01 | |

| Me2–αPiO | 2.24 | 2.07 | 2.20 | 2.60 | |

| Me2–βPiO | 2.23 | 2.27 | |||

| Me2--bWAT | 3.49 | 2.13 | 2.23 | 3.31 | |

| Me2--H2O | 2.17 | 2.12 | 2.24 | 2.29 | |

| Me2--H2O | 2.61 | 2.03 | 2.26 | 2.15 | |

| Me2--H2O | 2.07 | 2.18 | |||

| Average Me2 distances | 2.32 | 2.09 | 2.21 | 2.26 | |

| Lys165 NZ--βPiO | 2.33 | 3.35 | |||

| Ser240 OG--αPiO O2A | 3.42 | 2.72 | 2.75 | 3.06 | |

| Ser240 OG--bWAT | 2.95 | 2.72 | 2.91 | 3.03 | 2.83 |

| PA--bWAT | 3.74 | 3.64 | 3.68 | 3.55 | |

| nWATe–αPiO O2A | 2.41 | ||||

| Glu244 OE2--nWAT | 2.64 | ||||

| PA--nWAT | 3.04 | ||||

| Bond angles (degrees) | |||||

| bWAT--PA--O5B | 154 | 148 | 152 | 150 | |

| nWAT--PA--O5B | 156 | ||||

a Me, metal.

b C.N., coordination number.

c bWAT, bridging water.

d Distances in italic type are not assumed to represent first sphere metal ion coordination but are included for reference.

e nWAT, nucleophilic water.

Superposition of the backbone coordinates for all TP0796 structures reported herein range from 0.3 to 0.5 Å root mean square deviations for 327 C-α atoms, indicating the high level of isomorphism among the various complexes. The primary structural differences are reflected in the active site coordination of the bound ligands by protein residues, metals, and waters (see below).

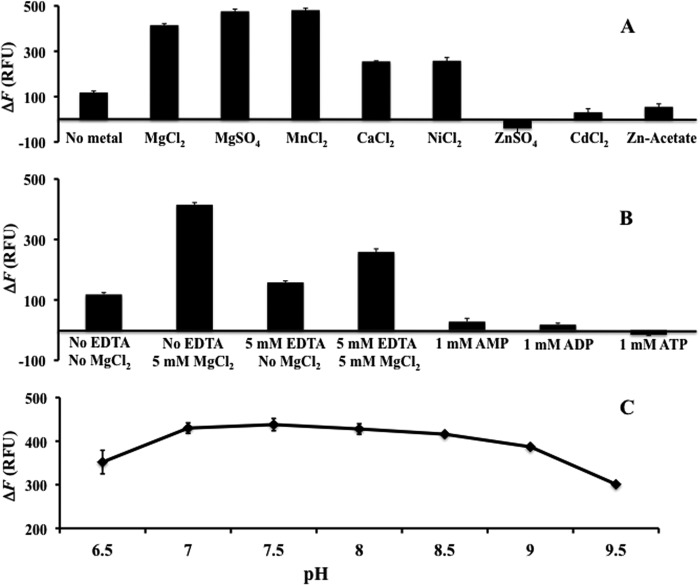

Characterization of FAD Pyrophosphatase Activity of TP0796

The crystal structure of TP0796 in the presence of FAD (no added Mg2+) (see below) showed the presence of a bimetal center near the phosphate moieties of bound FAD. These observations led us to investigate whether TP0796 could act as a hydrolase. TP0796 was incubated with FAD in the presence of divalent metal ions, and the formation of FMN was monitored via its differential fluorescence compared with FAD (32). TP0796 hydrolyzed FAD under these conditions (Fig. 4). When the effects of different cations at 5 mm concentrations were tested (Fig. 4A), both Mg2+ and Mn2+ most efficiently supported FAD hydrolysis. Other cations (Ca2+ or Ni2+) could replace Mg2+/Mn2+ but with lower catalytic efficiencies. To verify whether divalent metal ions are essential for FAD hydrolysis by TP0796, we assayed the enzyme in the presence of EDTA. As shown in Fig. 4B, EDTA inhibited the enzyme activity; thus, the activity of TP0796 is dependent on the presence of divalent metal ions. AMP, ADP, and ATP all strongly inhibited the hydrolase reactions (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Functional characterization of the recombinant T. pallidum FAD hydrolase activity. Enzyme activity was measured as described under “Experimental Procedures.” A, activation and metal dependence of FAD hydrolase activity. All metals were at 5 mm concentration. B, inhibition of FAD hydrolase activity. C, the pH dependence of FAD hydrolase activity. Error bars, S.D.

The optimum pH for the FAD pyrophosphatase activity of TP0796 was determined using a series of BIS-TRIS propane buffers ranging from pH 6.5 to 9.5. The enzyme showed a broad pH activity profile, with an optimum at pH 7.5 (Fig. 4C), which is physiologically relevant.

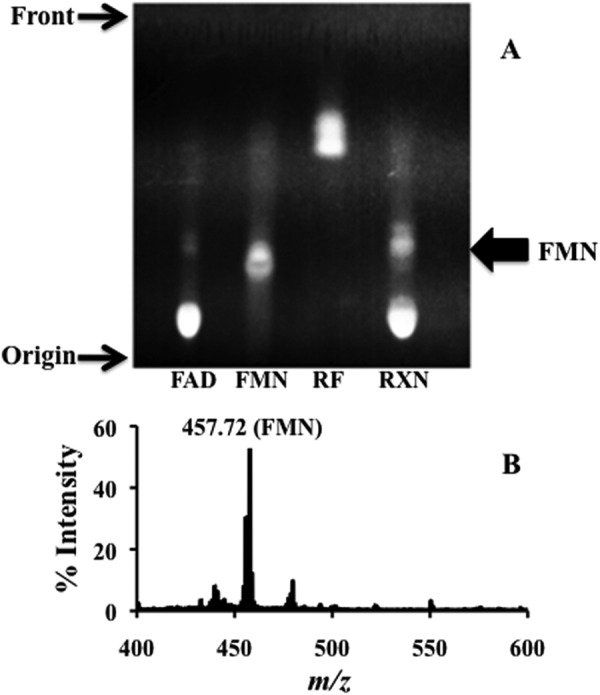

The hydrolysis of FAD by TP0796 produced a fluorescent compound when the reaction mixture was separated by TLC. Although the detection method used above assumed the formation of FMN (and AMP), we sought confirmation of this assumption. The flavin-containing reaction product was identified as FMN based on its identical migration to an FMN standard on a TLC plate (Fig. 5A). Additionally, MALDI-TOF mass analyses of the TLC-purified product gave the same mass as an FMN standard (457.72 m/z) (Fig. 5B). Based on the crystallographically observed Mg2+-AMP-bound structure (Fig. 3F) and in-solution identification of the reaction product (Fig. 5), it can be concluded that TP0796 hydrolyzes FAD into FMN and AMP, consistent with the general enzymatic mechanism of an FAD-pyrophosphatase (EC 3.6.1.18).

FIGURE 5.

Identification of the FAD hydrolase reaction product. A, thin layer chromatography of FAD hydrolase reaction products. Flavin standards (FAD, FMN, and riboflavin (RF)) and enzyme reaction mixture (RXN) were spotted on the TLC plate (see “Experimental Procedures”). B, MALDI-TOF spectrum of FAD hydrolase-produced FMN.

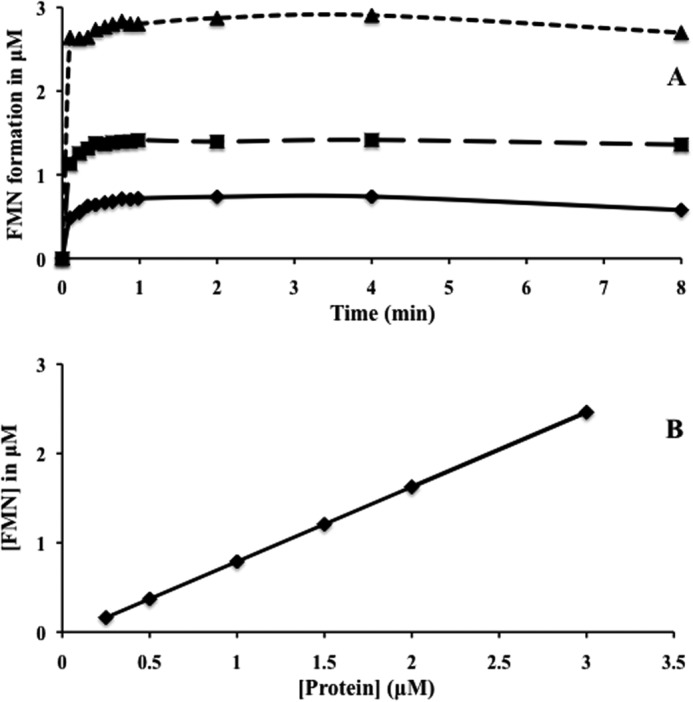

We attempted to examine the kinetics of the reaction catalyzed by TP0796 to determine the rate constant of FAD hydrolysis. However, the reactions were characterized by an initial burst of product followed by a linear phase, indicating a single-turnover reaction (Fig. 6A). This observation is consistent with the crystallographically observed product-bound structure and inhibition of the pyrophosphatase activity by AMP. The rate of burst is dependent on the enzyme concentration. These reactions were too fast for manual assays on a Tecan plate reader, so that even the earliest points in the time traces were at the end of the exponential phase. For this reason, we measured the extent and kinetics of FMN formation in single turnover FAD pyrophosphatase reactions that were catalyzed by TP0796. As shown in Fig. 6B, the plot of FMN formation against the enzyme concentration is strongly correlated, suggesting a single turnover mechanism. A calculated ratio of ∼0.7 μmol of FMN generated per μmol of enzyme was obtained. Given the possibility that a fraction (∼30%) of the “as-purified” protein is either liganded or inactive, we conclude that one molecule of FMN is generated by one molecule of protein under our assay conditions. Together, the results indicate that TP0796 can quantitatively hydrolyze FAD to FMN and AMP, and we propose that it be designated an FAD pyrophosphatase (EC 3.6.1.18).

FIGURE 6.

Reaction kinetics of FAD pyrophosphatase. A, single-turnover kinetics showing the burst phase of the FAD pyrophosphatase reaction. Kinetics of the burst phase of the reaction were obtained by recording the fluorescence changes (ΔF) immediately after the addition of the FAD substrate (10 μm) to the preincubated enzyme reaction mixtures containing 1 μm (solid line), 2 μm (dashed line), and 4 μm (dotted line) enzyme. Measured fluorescence changes (ΔF) were converted to FMN concentrations using an FMN standard curve and plotted as a function of time. B, linear relationship between FMN formation and protein concentration during turnover. The points represent the FMN concentrations derived from the changes in fluorescence (ΔF) experiments using an FMN standard curve.

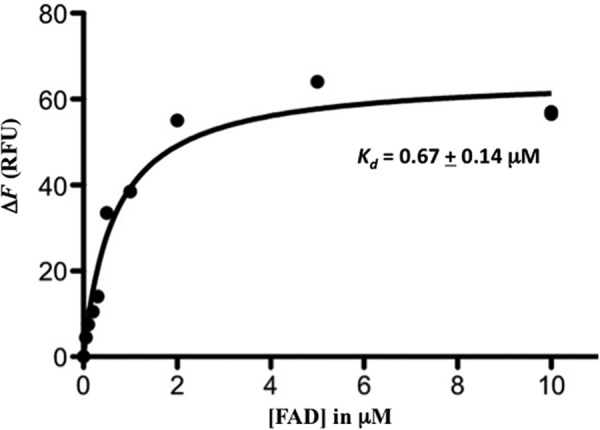

To investigate the hydrolytic activity of homologs of TP0796, we compared its activity with those of ApbE_Se and ApbE_Ec. Although ApbE_Se was reported to be an FAD-binding protein, no FAD hydrolytic activity was associated with the ApbE_Se (19). Our own studies on ligand-free ApbE_Ec demonstrated a decrease in the emission fluorescence of FAD in our assays (data not shown). This result indicated that ApbE_Ec might be an FAD-binding protein but not a hydrolase. Fluorescence titrations were thus used to determine the FAD binding affinity (Kd value) to ApbE_Ec. As shown in Fig. 7, the Kd of FAD binding to ApbE_Ec was ∼0.7 μm. This high value of Kd could explain why there is no bound FAD in the reported ApbE_Ec crystal structure. We attempted to crystallize fully reconstituted FAD-bound ApbE_Ec under previously reported conditions and obtained colorless ApbE_Ec crystals. Analysis of x-ray diffraction data collected from one of these crystals revealed no discernible FAD electron density in the nucleotide-binding site (data not shown). Unlike the TP0796-catalyzed reaction, the binding event to ApbE_Ec was metal-independent (data not shown). Further, no metal was included in the FAD-bound ApbE_Se crystallographic model (19), although the amino acid residues involved in the metal binding of TP0796 are conserved among the known ApbE structures. This observation suggests that the catalytic function of TP0796 is related to the presence of the bimetal center, and FAD pyrophosphatase activity may have evolved as an additional trait in a subset of ApbE proteins.

FIGURE 7.

FAD binding to ApbE_Ec. Changes in fluorescence emission (ΔF) of ligand-free ApbE_Ec protein upon exposure to FAD were plotted as a function of FAD concentration. The solid line reflecting the best fit curve was used to derive the Kd value using GraphPad software.

TP0796 Substrate Complex (FAD-Mg2+)

To assess whether TP0796 is an FAD-binding protein, TP0796 was incubated with 5 mm FAD prior to crystallization, and complex crystals isomorphous to the apo were grown under similar conditions; the structure was refined to a resolution of 1.45 Å. Despite the bright yellow color of the initial protein preparation, the crystals were only slightly yellow in color, and upon initial inspection of the electron density map, it appeared as if the protein contained bound ADP and two Mg2+ atoms and not FAD-Mg2+. Further refinement revealed weak electron density for the FMN portion of the bound substrate. This led us to consider the possibility that TP0796 had enzymatically cleaved the FAD, with the most likely activity being that of an FAD pyrophosphatase that would produce one molecule each of AMP and FMN as products. Crystallographic refinement of the bound ligands as a mixture of FAD (substrate) and AMP (product) resulted in a large amount of positive difference electron density in the β-phosphate region of the substrate, and there was no observation of multiple conformations for residues that surround the diphosphate-binding site. Because it was not expected that there was a significant amount of ADP as an impurity in the freshly made FAD solutions used for crystal growth, in the final cycles of refinement, the ligand was modeled as an FAD at 100% occupancy, and the B-factors of the ligand atoms were allowed to vary. As a result, there is no longer a large amount of positive (or negative) difference density in the diphosphate region of the FAD (Fig. 3B).

The conditions for crystal growth of the FAD-Mg2+ complex included 5 mm FAD, but no Mg2+ was added during the crystallization or purification of TP0796. Apo-TP0796 crystallization also did not include the explicit addition of Mg2+ to the purification or crystallization buffer. Thus, the metal ions observed in these structures were probably obtained as trace elements from the purification and crystallization chemicals or were adsorbed to the laboratory glassware and were thus at submicromolar (or lower) concentrations. Because the concentration of the nucleotide in the crystallization buffer was much higher than that of the catalytically required metal ion, significant amounts of FAD hydrolysis were not expected to occur in the time frame of crystal nucleation and growth.

TP0796 binds FAD in a bent conformation, centered around the diphosphate (Fig. 3C), which is in an eclipsed conformation, such that the ribose O3B atom is 2.8 Å from the ribitol O3′ atom. The overall bent conformation is similar to that found in the ApbE_Se structure but differs greatly in the central portion of the molecule (Fig. 3D). Whereas the adenine and isoalloxazine rings in the two structures align quite well, the central diphosphate and ribitol portions of the FAD adopt quite different conformations in the two structures. It is presumed that the coordination of two Mg2+ ions to the FAD diphosphate and to the protein side chains in the TP0796 structure is the cause of these differences because there are no metal ions identified in the ApbE_Se structure. The AMP portion of the FAD in TP0796 is more buried compared with the ApbE_Se structure, with solvent-accessible surface areas of 1.4 and 9.2%, respectively (42).

In order for substrate to bind, hydrolysis to occur, and product to be released, it appears that TP0796 must undergo a conformational change that we do not observe in any of our structures. Thus, the FAD-Mg2+ complex structure appears to be a substrate complex that is unable to undergo hydrolysis in the solid state, presumably due to an inability to adopt a conformation consistent with the transition state and subsequent release of products. We do see evidence of FMN formation under the crystallization conditions in the solution state, where TP0796 would be free to adopt a myriad of possible conformations.

The relatively weaker density for portions of the bound FAD in the TP0796 structure is probably due to the dearth of specific protein contacts for the ribitol and isoalloxazine rings in the spacious FMN region of the substrate-binding cavity. In comparison with the AMP portion of the FAD molecule, the FMN portion is relatively solvent-exposed, with a solvent-accessible surface area of 31.1%. In the ApbE_Se FAD-bound structure, specific hydrogen-bonding interactions occur between protein side chains and the ribitol hydroxyls, and the isoalloxazine ring is sandwiched between the side chains of Tyr-78 and Met-41. The equivalent residues in TP0796 are Asn-55 and Ile-17, respectively. Whereas these side chains contact the isoalloxazine ring in the TP0796 complex, the amount of buried surface area is smaller than in the ApbE_Se complex, with an average solvent-accessible surface area of 24.2% for the FMN portion of the FAD. The polar carboxamide of Asn-55 contact with this ring is undoubtedly less stabilizing than the π-stacking interaction of the aromatic ring of Tyr-78 in the ApbE_Se structure. The only contact to the ribitol portion of the FAD in the TP0796 structure is with the guanadinium moiety of Arg245, although the electron density for this side chain is also weak relative to the main chain protein atoms, implying some flexibility. An attempt to model a molecule of NADP(H) into the binding site revealed steric clashes between the ribose O2B phosphate and the conserved residue Asp159, thereby explaining the inability of ApbE homologs to bind this coenzyme.

Of the two metal ions bound near the FAD diphosphate, one is in the same location as in the apo-TP0796 structure (hereafter designated as Me1), and the other metal (Me2) is pentagonally coordinated to the OD1 of Asp284, one oxygen each of the α- and β-phosphates, and two water molecules (Fig. 3E). One of the waters coordinated to Me1 has been replaced with an α-phosphate oxygen of the FAD. Assignment of both Me1 and Me2 as Mg2+ ions is based on average bond distances of 2.4 and 2.3 Å, respectively (Table 3), coordination geometry, and the identity of metal ligands. This assessment was confirmed via the refined electron density. The bimetal distance of 3.3 Å corresponds to the range of 3–4 Å commonly observed for binuclear metallohydrolases (43), and the monodentate aspartate bridging the metal centers has, for example, been observed in the human and E. coli ecto-5′-nucleotidase structures (44, 45).

Phosphoryl transfer reactions, such as the hydrolytic one studied herein, typically proceed through an associative SN2 mechanism, whereby the nucleophile undergoes an in-line attack of the phosphate to form a pentagonal bipyramidal transition state with resulting inversion of configuration of the product (46). Efficient catalysis requires 1) proper positioning of the substrate, transition state, and product during the reaction; 2) a sufficiently nucleophilic species for attack, such as H2O/OH−; 3) appropriate positioning of the nucleophile for in-line attack of the substrate; 4) charge neutralization by one or more positively charged groups of the doubly negatively charged pentavalent transition state as it forms; 5) a proton donor to the transition state to protonate the leaving group; and 6) charge neutralization of the product during formation and prior to release. In bimetal-activated phosphoryl transfer hydrolysis reactions, the bimetal center potentially serves a multifunctional role (47). It may contribute to positioning the substrate, transition state, and products during catalysis by coordinating phosphate oxygens and assist in neutralizing negative charge during formation of the transition state, product formation, and release. One or both of the metals may help to preconfigure protein active site residues for catalysis, bind or assist in activation of the attacking nucleophile, and position the proton donor for efficient proton transfer to the transition state. In addition to the two Mg2+ ions, three protein residues in the FAD-binding site are noteworthy in their interactions near the site of phosphate hydrolysis. The NE2 of His256 is 3.2 Å from the bridging O3P of the FAD diphosphate and could assist in neutralization of the negatively charged phosphoanion transition state or could serve as the proton donor. The OG of Ser240 is within hydrogen-bonding distance of the Me1-coordinated water molecule, and the carboxylate of Glu244 coordinates a water molecule that bridges between the Ser240 OG and the FAD α-phosphate (Table 3). This water molecule is situated 3.0 Å from the site of hydrolysis at the α-phosphate atom, and it forms an angle of 156° to the PA-O5B atoms of the FAD. Thus, because it is in position for an in-line nucleophilic attack on the α-phosphate and is potentially activated as a nucleophile by its interaction with Glu244, we have designated this water as “nWAT.” Another water coordinated to Me1 is also positioned to form an angle of 154° to the PA-O5B atoms of the FAD, but it is significantly farther (3.7 Å) from the phosphorus atom site of attack and is thus a less likely candidate as a nucleophile. In the other TP0796 ligand complex structures, this water appears to switch coordination from Me1 to Me2 (see below); therefore, we have designated this water as “bWAT” to designate it as the water that “bridges” the metal sites. Stabilization of the transition state and leaving group phosphates could also occur through phosphoryl oxygen interactions with the NZ atom of Lys165 and the guanadinium group of Arg245. His256 and Ser240 are conserved over all ApbE homologs, and Glu244 is an arginine and Lys165 is a glutamate in the ApbE_Se and ApbE_Ec structures.

TP0796 Product Complex (AMP-Mg2+)

After obtaining the high resolution FAD-Mg2+ complex structure, an attempt was made to obtain a higher resolution apo-structure from crystals grown from “as purified” TP0796. Inspection of the electron density map calculated from a 1.5 Å data set collected on one of these crystals revealed that there was a substoichiometric amount of AMP-Mg2+ in the ligand-binding site (data not shown). Subsequently, the protein was incubated with 5 mm AMP and 5 mm Mg2+, and complex crystals isomorphous to the apo were grown under similar conditions; this structure was refined to a resolution of 1.45 Å. As in the substrate complex, there are two metal ions bound in sites Me1 and Me2, which have been assigned as Mg2+ ions (Fig. 3F and Table 3). In contrast to the apo and substrate FAD complex structures, Me1 is 5-coordinate and has no waters in its first coordination sphere. The OD1 of Asp284, an AMP phosphate oxygen, and four water molecules coordinate Me2.

Compared with the substrate FAD-Mg2+ complex, NE2 of His256 is at approximately the same distance (3.1 Å) from the O3P of AMP, the OG of Ser240 is closer to the Me1-coordinated water by 0.7 Å, and Glu244 has adopted a rotamer that places it farther away from the AMP α-phosphate, probably due to charge repulsion.

TP0796 Metal Identification

Potential identities of the ions in sites Me1 and Me2 that are consistent with the bond lengths and coordination numbers observed include Na+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+. In an attempt to unambiguously identify the bound metal ions, AMP-Mn2+ complex crystals were generated by incubation of TP0796 with 5 mm AMP and 5 mm Mn2+. The coordination of the nucleotide and metals in this structure was isomorphous to the AMP-Mg2+ complex structure. X-ray diffraction data to 1.90 Å resolution were collected at the Mn2+ K-edge energy, and an anomalous difference map was calculated (Fig. 3G). A strong peak at the Me2 site was observed as well as a smaller peak at the AMP phosphate that is due to the small amount of anomalous signal expected for phosphorus at this energy (48). No anomalous signal was observed at the Me1 site, which is probably a reflection of the high affinity of this site for a non-exchangeable metal ion that does not absorb x-rays at the incident wavelength. This is in agreement with our observation that TP0796 protein has a tendency to precipitate when stored for long periods when isolated without added metal ion but is stable for weeks at 4 °C when stored in a buffer containing 5 mm Mg2+ (not shown). This instability may be a function of less than 100% incorporation of Mg2+ ion in the Me1 site. The absence of anomalous signal at site Me1 indicates that K+ is not a likely candidate ion because the expected anomalous signal at the manganese K-absorption edge for potassium is almost 3 times that expected for phosphorus. Attempts to refine the metal in site Me1 as a Ca2+ in all structures presented in this work resulted in a large amount of negative difference electron density at Me1. This negative electron density disappeared in the difference density maps once Me1 was refined as a Mg2+ ion. B-Factors of the refined metal ions are reported in Table 3. The low value of 3.2 Å2 for the Mg2+ in Me1 for the ADP-Mg2+ complex is not unexpected, given that the B-factors for the first coordination sphere atoms at this metal site range from 3.4 to 11.5 Å2 for non-solvent atoms, with an average value of 7.0 Å2. Coordination numbers of 5 and 6 are most common for Mg2+ ions and less likely for Ca2+ and Na+ ions (40). We conclude that the data reported throughout this paper are most consistent with Mg2+ ions bound at sites Me1 and Me2 (when present). The lack of Mn2+ exchange described above at site Me1 therefore probably indicates that the dissociation of Mg2+ from Me1 is very slow on the time scale of our incubation and crystallization protocols.

TP0796 Inhibitor Complex (ADP-Mg2+)

To investigate the nature of inhibition of the FAD pyrophosphatase activity of TP0796, protein was incubated with 5 mm ADP and 5 mm Mg2+, complex crystals isomorphous to the apo were grown under similar conditions, and the structure was refined to a resolution of 2.30 Å. The two metal ions bound in sites Me1 and Me2 were assigned as Mg2+ ions (Table 3) and were coordinated in a similar fashion as observed in the substrate FAD-Mg2+ complex (Fig. 3H). The main differences between the two structures are that the OG of Ser240 is closer to the Me1-coordinated water by 0.4 Å, the lack of a Glu244-coordinated water that is within 3 Å of the α-phosphate of the ADP, and the ∼1-Å lengthening of the distance between the Lys165 NZ and the β-phosphate of the ADP. Glu244 has adopted a rotamer that removes it from the ADP phosphate-binding site, probably due to charge repulsion. The inability of TP0796 to hydrolyze ADP or ATP probably stems from the lack of both an appropriate nucleophile and the catalytic residue Glu244 in the active site. These results demonstrate that the mechanism of ADP inhibition of TP0796 is competitive; by occupying part of the FAD binding site, it sterically excludes the binding of the substrate.

Enzymatic Mechanism

Recent studies of the ApbE protein from Salmonella spp. (17, 19) have proposed an FAD-binding role for this class of bacterial periplasmic lipoproteins and implicated it in the thiamine biosynthetic pathway for this organism. We initiated a detailed molecular study of TP0796, inasmuch as the T. pallidum genome does not include genes for thiamine biosynthesis, and thus the role of this protein was unclear. We have obtained solution evidence that TP0796 rather functions as a bimetal Mg2+-dependent FAD pyrophosphatase and not simply as a periplasmic binding protein. The broad pH profile for enzyme activity is consistent with a solvent-derived hydroxide ion nucleophile for which we have structural evidence in a substrate complex with FAD. There are reports of this enzyme activity associated with plant chloroplasts and mitochondria (49), yeast mitochondria (50), rat liver mitochondria (51), and human mitochondria (52–54). It has been reported that purified 5′-nucleotidase from human placental mitochondria possesses metal-dependent FAD pyrophosphatase activity (53), which is inhibited by EDTA and stimulated by Co2+ and to a lesser degree by Mn2+. This glycoenzyme, which is present as an ectoenzyme bound to the outer plasma membrane, was specific for FAD and did not hydrolyze ADP, ATP, NAD(H), or FMN. Several structures are available for human soluble and mitochondrial 5′-nucleotidases, which are oligomeric multidomain proteins that contain a Rossmann fold core and a cap domain and belong to the haloacid dehalogenase superfamily of hydrolases (44, 55, 56). It is tempting to speculate that, due to the correlations in metal dependence and specific activity between TP0796 and the human placental mitochondrial enzyme, they may share some similarities in active site configurations despite any detectable sequence or overall structural similarities.

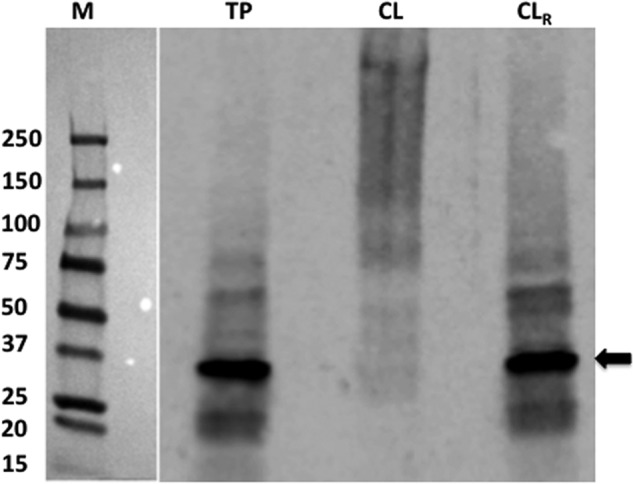

Native TP0796 Is Associated with Other Proteins in Vivo

As mentioned earlier, AMP, a product of the TP0796-catalyzed reaction, inhibited the enzyme activity of TP0796. However, it remains unclear how TP0796 releases the AMP product. It is possible that an interaction with an unidentified protein(s) results in a conformational change that may facilitate AMP release. Therefore, to examine the potential in vivo interactions of native TP0796 with other partner proteins, treponemes were either untreated or treated with formaldehyde and then processed for immunoblot analysis using antibody against recombinant TP0796. As shown in Fig. 8, when treponemes were incubated under conditions without formaldehyde, only monomeric TP0796 was observed (lane TP). Cross-linking treatment of treponemes with formaldehyde resulted in a disappearance of the TP0796 monomer, with concomitant formation of multiple, diffuse, high molecular mass protein bands (lane CL, above ∼100 kDa). This result probably reflected the interaction of TP0796 with unknown protein partners. The larger complexes revealed by formaldehyde cross-linking were essentially undetected after boiling (TP0796 monomer was the dominant band, lane CLR). These results strongly support the contention that the high molecular mass protein bands observed on immunoblots contained TP0796 complexed with other interacting partners. In addition to the major polypeptide bands observed in immunoblots, some minor reactivities probably represented spurious (artifactual) bands resulting from the highly sensitive chemiluminescent detection method. Based on the combined results, we conclude that there are protein-protein interactions between native TP0796 and unidentified protein partners in vivo.

FIGURE 8.

In vivo formaldehyde cross-linking of TP0796. Samples were resolved in a gel and then electrotransferred to a membrane. The membrane was then probed with an anti-TP0796 antibody and visualized by enhanced chemiluminescent detection using an anti-goat IgG-HRP. Lane TP, T. pallidum not exposed to the formaldehyde; lane CL, formaldehyde-cross-linked treponemes; lane CLR, boiled treponemes (to break the cross-links prior to SDS-PAGE). The arrow represents the position of the native TP0796 subunit. The positions of the prestained molecular mass standards (M; values are in kDa) are indicated at the left.

DISCUSSION

Herein we demonstrate a novel Mg2+-FAD pyrophosphatase activity for a previously uncharacterized bacterial periplasmic lipoprotein (TP0796), an activity previously assumed to exist for flavin homeostasis only in eukaryotes (50, 57). In yeast, the mitochondrial enzyme maintains a redox-active flavin (FMN and FAD) pool for a number of dehydrogenases and oxidase-catalyzed reactions that play a crucial function in both bioenergetics and cellular regulation (50). Bacteria lack the organelles of higher organisms, which typically are involved in flavin homeostasis and redox reactions. One potential way for bacterial diderms to compensate for this deficiency is to exploit their periplasmic space. T. pallidum and other bacteria appear to have acquired a distinct bimetal-dependent FAD pyrophosphatase to ensure the supply of flavin cofactors (FMN and FAD) either for redox reactions, flavoprotein biogenesis, or both. The treponemal enzyme is product-inhibited by AMP, AMP and FAD share the same binding cleft, and thus the product inhibition could be the means of regulating FMN and FAD concentrations in the treponemal periplasm. However, it is unclear why FAD must be hydrolyzed to FMN, because nothing is known about the subsequent physiological impact of the FAD-hydrolyzing enzyme. Although in bacteria the majority of enzymes are found in the cytoplasm, there is precedence for periplasmic enzymes that hydrolyze nucleotides for subsequent utilization inside the cell (45, 58, 59). In further support of the FAD pyrophosphatase enzymatic activity, recombinant proteins from Treponema denticola, Enterococcus faecalis, and Listeria monocytogenes exhibit the same in vitro activity.4

We have obtained the highest resolution x-ray crystal structures to date for any member of the ApbE protein family and herein report the structures of TP0796 in multiple forms, including the apo-form and substrate-, product-, and inhibitor-bound. Metal ions are found in all forms of the protein and have been identified as Mg2+ based upon solution studies, geometric considerations, and crystallographic refinement results. Catalytically important residues involved in substrate binding, solvent nucleophile activation, and proton donation include Ser240, Glu244, and His256.

Subtle structural differences between TP0796 and ApbE_Se are probably responsible for their functional differences. The positioning of the Glu244-Arg245-His256 residues of the β-hairpin loop in the active site, the presence of bound metal ions, a solvent molecule hydrogen-bonded to Ser240 and Glu244 in a conformation suitable for in-line nucleophilic attack, and the absence of stabilizing hydrophobic residues near the isoalloxazine ring in TP0796 all contribute to placing the FAD in a conformation suitable for phosphoester hydrolysis and FMN product release. We predict that the close structural and sequence homolog ApbE_Tm (see above) also is likely to be an FAD pyrophosphatase, but this remains to be verified experimentally.

Although no metal ions have been identified in the ApbE_Se structure, the other ApbE homolog structures contain various mono- or divalent cations in sites analogous to Me1. In the ApbE_Ec structure (PDB entry 2O18), this ion has been identified as a Ca2+, probably based upon the average bond lengths of around 2.7–2.8 Å. Because this structure was solved and refined by a National Institutes of Health Protein Structure Initiative (PSI) group (Northeast Structural Genomics Consortium), there is no publication that accompanies this structure, and it can thus be presumed that no solution or crystallographic experiments were conducted to prove or disprove the metal identity. This structure was refined using the CNS crystallographic software package, which is known to tightly restrain metal-ligand bond distances, so it is possible that the actual metal ion in this structure is Mg2+, and the long bond distances are simply a refinement artifact. In the ApbE_Tm structure (18) (PDB entry 1VRM), there is a water molecule modeled in the Me1 site, but it is octahedrally coordinated with an average bond length of 2.4 Å to the main chain and OD1 oxygens of Asp303, the OG1 of Thr307, the main chain oxygen of Gly191, and two water molecules. The B-factor of this atom is 4.8 Å2, which is significantly lower than the average B-factor of 31.0 Å2 for all of the water molecules in this structure and lower than the average B-factor of 12.0 Å2 for the protein. Once again, this is a structure that was solved and refined by a PSI group (Joint Center for Structural Genomics), and there is no primary citation for the work. Thus, we feel this atom probably was mistakenly assigned as water and should be Mg2+. The D. vulgaris Hildenborough structure (PDB entry 2O34) was solved and refined by yet another PSI group (New York SGX Research Center for Structural Genomics) with no primary citation, and this structural model contains Na+ ions in the analogous Me1 site of both monomers in the asymmetric unit, with average bond lengths of 2.3–2.4 Å. The B-factors and bond lengths of this ion are reasonable, but due to the one-electron difference between Na+ and Mg2+, it is difficult to identify the bound ion with certainty from the data presented. Despite the structural similarity of this protein to the other ApbE homologs, the relatively small size of the protein and the absence of a clear binding pocket for nucleotides (either AMP, ADP or FAD) call its function into question as either an FAD-binding protein or FAD pyrophosphatase.

FMN product release from TP0796 could be facilitated by interaction with Arg245 and Lys165 and also by the accessibility of the bulk solvent to this product. It is unclear how TP0796 releases the product AMP, although it is possible that an interaction of native TP0796 with a yet unidentified protein (TP0796 apparently interacts with several unidentified proteins in vivo; see Fig. 8) results in a conformational change that facilitates release. This could occur, for example, by an interaction that causes the β-hairpin loop to become poorly ordered and thus removes important ligand binding residues from the enzyme active site.

It is not unusual for enzymes to exhibit single turnover in vitro due to the absence of interacting partners that are required for the in vivo activity. Prominent examples include the multienzyme E. coli MutM-MutY-MutT DNA repair system that removes the adenine in 7,8-dihydro-8-oxo-2′-deoxyguanosine (OG):A base pairs. In the absence of the other two enzymes, MutY exhibits single turnover, product inhibition, and slow product release with the OG:A mispair substrate (60). Slow product release may be biologically relevant so as to prevent premature release of the OG to the MutM enzyme, which would result in a DNA double-strand break. Dissociation of the product from MutY in vitro is enhanced by the inclusion of either of the apurinic-apyrimidinic endonucleases III or IV in the reaction mixture, and the C-terminal domain of MutY is required for this enhancement, presumably through protein-protein interactions (61).

Another example of in vitro single turnover and product inhibition is that of E. coli chorismate lyase, which converts chorismate to 4-hydroxybenzoate in the ubiquinone biosynthesis pathway. The crystal structure of the enzyme reveals the tightly bound product in a hydrophobic pocket completely shielded from the bulk solvent by two helix-turn-helix loops that would be required to make large conformational changes for substrate binding and product release (62). This sequestration of product by the cytosolic chorismate lyase may be biologically relevant because association with the next enzyme in the pathway, the membrane-bound enzyme 4-hydroxybenzoate octaprenyltransferase, may be required for delivery of the 4-hydroxybenzoate substrate (63). The chorismate lyase fold has also been found to serve an effector binding function in the C-terminal domain of the E. coli PhnF transcriptional regulator, where the crystal structure of the domain contains a β-d-fructopyranose molecule in the hydrophobic binding pocket (64). Thus, the chorismate lyase fold is an example of a common fold adapted for regulatory as well as enzymatic function.

We propose to rename the ApbE superfamily as a periplasmic “flavin-trafficking protein” (Ftp) to reflect its proper biochemical function. Genome analyses, along with the available limited structural data, have failed to identify this previously uncharacterized FAD pyrophosphatase activity within the ApbE superfamily. This is primarily due to the lack of precise biochemical characterization of the deposited structures (65), which has led to the misannotation of the ApbE superfamily as members of a thiamine biosynthetic pathway (16). Some of the family members bind FAD, as in the case of S. enterica and E. coli, whereas others have evolved to catalyze the hydrolysis of FAD, but they both traffic flavin. Although Ftp is predominantly a prokaryotic protein superfamily, it is also found in lower eukaryotes, such as Trypanosoma spp. (the causative agents of sleeping sickness and Chagas disease) and Leishmania spp. (the causative agent of leishmaniasis), where it is fused or coupled with a mitochondrial NADH-dependent fumarate reductase, a flavin-requiring multimeric enzyme associated with the respiratory chain for electron transfer from either NADH or FADH2/FMNH2 to fumarate (66–68).

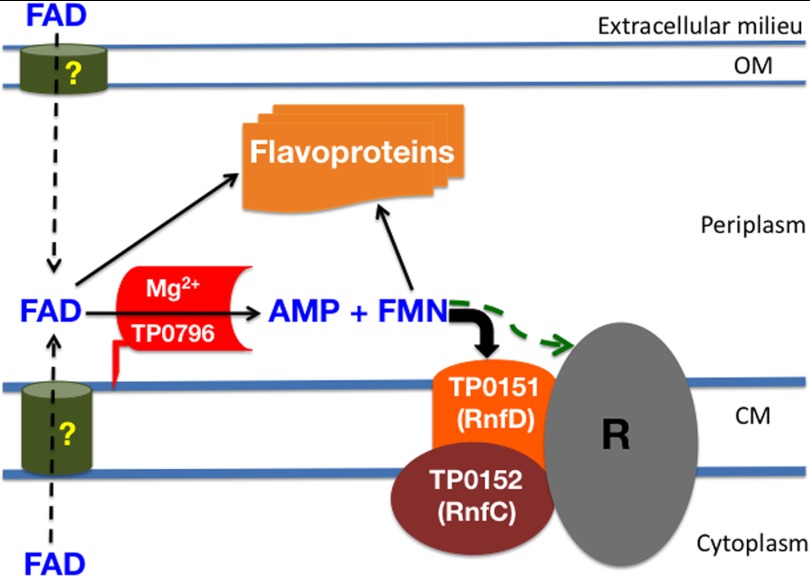

Our discovery of a treponemal FAD pyrophosphatase implies that flavin homeostasis could play an important role in maintaining periplasmic flavin-containing compounds for utilization by putative periplasmic flavoproteins. The Universal Protein Resource Knowledgebase comprehensive resource for protein sequence and annotation data predicts that the T. pallidum genome encodes several flavoproteins in both the periplasm and cytoplasm. These are TP0081 (a putative FAD-binding protein), TP0171 (a putative periplasmic FMN-binding protein, also known as TP15), TP0298 (RfuA, a periplasmic riboflavin-binding protein), TP0572 (a putative FMN-binding protein), TP0735 (GltA, an FAD requiring glutamate synthase), TP0736 (HydG, a putative FAD-binding protein), TP0814 (trxB, an FAD thioredoxin reductase), TP0888 (RibF, an FAD synthetase), TP0921 (Nox, a flavin-requiring NADH oxidase), and TP0925 (fldA, a flavodoxin). T. pallidum may utilize some of these flavoproteins either in redox processes or in flavin-dependent non-redox reactions as described herein. Nonetheless, flavin-containing compounds (FMN and FAD) are the cofactors of flavoproteins, and their reported functions include transferring electrons from and to reactive redox centers (69). In Gram-negative bacteria, genes encoding the RnfABCDGE system are believed to be involved in a redox-driven ion pump. Topological analyses indicate that the FMN cofactor in RnfD and RnfG of the RnfABCDGE system are exposed on the outer leaflet of the cytoplasmic membrane (70, 71). Although T. pallidum is thought to lack an Rnf-type electron transport complex (3, 4), other treponemes, such as T. denticola (71), Treponema phagedenis (Weinstock et al., NCBI database), Treponema brennaborense (Lucas et al., NCBI database), Treponema azotonutricium (Tetu et al., NCBI database), and Treponema succinifaciens (72), are reported to have a complete RnfABCDGE system. However, their biochemical characterization is lacking, and therefore, most of the available information is derived only from bioinformatics. Our UniProtKB search revealed that the T. pallidum genome encodes at least two likely Rnf homologs: tp0151 (RnfD), which probably requires an FMN cofactor, and tp0152 (RnfC), a protein with sequence signatures suggesting that it contains an Fe-S cluster. The presence of these components in the colinear gene cluster tp0147–tp0153 (3) suggests that T. pallidum could have a membrane-bound electron transfer complex that employs these proteins, at least one of which apparently requires FMN. Thus, in T. pallidum and other bacteria, there very likely are periplasmic proteins that require FMN for their function. The apparent absence of quinone-synthesizing enzymes in T. pallidum (4) suggests that its Rnf components (and thus Ftp) play a critical role in energy transduction (73) in this bacterium.

These data raise the question of how bacteria supply FMN to periplasmic proteins. There are reports that bacteria of the genus Shewanella secrete their endogenously synthesized FAD via an unknown cytoplasmic membrane exporter to be processed in the periplasm by an UshA nucleotidase for extracellular flavin-requiring electron shuttles (59, 74, 75). However, this mechanism is not likely to be applicable to T. pallidum. Unlike most bacteria, T. pallidum lacks the riboflavin biosynthesis pathway and relies on its uptake from the host via an ABC-type transport system (76). We therefore propose that periplasmic FMN is supplied by the action of TP0796 on exogenously acquired FAD (Fig. 9). In this model, FAD diffuses into the periplasm via a putative outer membrane porin (77). Its relative abundance in human plasma makes FAD the likeliest candidate as an FMN source (78). Once in the periplasm, FAD undergoes hydrolysis by Ftp, thereby providing the necessary FMN for flavoproteins (Fig. 9). The proposed model not only explains how FMN is supplied to the electron transport complex but also accounts for an FMN pool for periplasmic flavoprotein biogenesis. The physical interaction of the T. pallidum Ftp with several other proteins (Fig. 8) adds credence to this proposed bifunctional role. This model also may hold true for Ftp-containing bacteria that require periplasmic FMN but lack the Shewanella export/nucleotidase pair. There is an analogous mechanism for NAD uptake and processing by an NAD pyrophosphatase in the periplasm of Haemophilus influenza, which has a requirement for the cofactor (79, 80). Nonetheless, the possibility of FAD pyrophosphatases in other pathogenic bacteria deserves further investigation. Moreover, the proposed new conceptual flavin turnover processes implied by our studies may be common to all bacteria utilizing an Rnf redox system as the physiological electron donor; further studies of the Ftp proteins and their in vivo interactions will broaden our overall understanding of flavin homeostasis and turnover in bacteria (Fig. 9). Finally, Ftp is found both in pathogenic bacteria and in the human parasites Trypanosoma and Leishmania. Given that the mammalian FAD pyrophosphatase is probably a member of a different superfamily, it is tempting to speculate that the Ftp family may offer potential promising targets for drug therapy, without serious side effects to the mammalian host.

FIGURE 9.

Model of flavin turnover and utilization pathways within the T. pallidum periplasm. Following the uptake of FAD (either endogenously or externally) via unknown mechanisms into the T. pallidum periplasm, FAD is hydrolyzed by the bimetal-dependent FAD pyrophosphatase (Mg2+-TP0796, also known as Ftp) into AMP and FMN. AMP inhibits the reaction to maintain a balance of FAD and FMN during the growth. FMN is then utilized by either the periplasmic flavoproteins or the periplasmic faces of a putative FMN-based cytoplasmic membrane redox center containing the RnfC and RnfD homologs that are present in T. pallidum. The oval labeled with R represents putative additional members of the redox complex in T. pallidum; in other bacteria, it represents the remaining members of the RnfABCDGE redox complex. The green arrow represents the fact that, whereas in other bacteria the periplasmic FMN probably supplies RnfG with its cofactor, it is not established whether any member of the putative R-complex requires FMN. CM, cytoplasmic membrane; OM, outer membrane.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Martin Goldberg for technical assistance and the scientists in the University of Texas Southwestern Protein Chemistry Core for protein sequence and mass analyses. The structures shown in this report are derived from work performed on beamline 19-ID at Argonne National Laboratory, Structural Biology Center at the Advanced Photon Source. Argonne is operated by UChicago Argonne, LLC, for the United States Department of Energy, Office of Biological and Environmental Research under Contract DE-AC02-06CH11357.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant AI056305 (to M. V. N.).

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 4IFU, 4IG1, 4IFZ, 4IFX, and 4IFW) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank (http://wwpdb.org/).

This article contains supplemental Fig. 1.

R. K. Deka, C. A. Brautigam, W. Z. Liu, D. R. Tomchick, and M. V. Norgard, unpublished data.

- PDB

- Protein Data Bank

- ApbE_Se

- S. enterica ApbE protein

- ApbE_Ec

- E. coli ApbE protein

- ApbE_Tm

- T. maritima ApbE protein

- Ftp

- flavin-trafficking protein

- RFU

- relative fluorescence units

- Rnf

- Rhodobacter nitogen fixation

- BIS-TRIS propane

- 1,3-bis[tris(hydroxymethyl)methylamino]propane

- PSI

- Protein Structure Initiative

- r.m.s.

- root mean square.

REFERENCES

- 1. Sell S., Norris S. J. (1983) The biology, pathology, and immunology of syphilis. Int. Rev. Exp. Pathol. 24, 203–276 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Robinson W. N., Jr., Hitchcock P. J., McGee Z. A. (1993) Syphilis. Disease with a history from mechanisms of microbial disease. in Syphilis with a History (Schoechter M., Medoff G., Eisenstein B. I., eds) pp. 334–342, Williams and Wilkins, Baltimore [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fraser C. M., Norris S. J., Weinstock G. M., White O., Sutton G. G., Dodson R., Gwinn M., Hickey E. K., Clayton R., Ketchum K. A., Sodergren E., Hardham J. M., McLeod M. P., Salzberg S., Peterson J., Khalak H., Richardson D., Howell J. K., Chidambaram M., Utterback T., McDonald L., Artiach P., Bowman C., Cotton M. D., Fujii C., Garland S., Hatch B., Horst K., Roberts K., Sandusky M., Weidman J., Smith H. O., Venter J. C. (1998) Complete genome sequence of Treponema pallidum, the syphilis spirochete. Science 281, 375–388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Norris S. J., Cox D. L., Weinstock G. M. (2001) Biology of Treponema pallidum. Correlation of functional activities with genome sequence data. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 3, 37–62 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Deka R. K., Machius M., Norgard M. V., Tomchick D. R. (2002) Crystal structure of the 47-kDa lipoprotein of Treponema pallidum reveals a novel penicillin-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 41857–41864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deka R. K., Neil L., Hagman K. E., Machius M., Tomchick D. R., Brautigam C. A., Norgard M. V. (2004) Structural evidence that the 32-kilodalton lipoprotein (Tp32) of Treponema pallidum is an l-methionine-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55644–55650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Deka R. K., Goldberg M. S., Hagman K. E., Norgard M. V. (2004) The Tp38 (TpMglB-2) lipoprotein binds glucose in a manner consistent with receptor function in Treponema pallidum. J. Bacteriol. 186, 2303–2308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deka R. K., Brautigam C. A., Yang X. F., Blevins J. S., Machius M., Tomchick D. R., Norgard M. V. (2006) The PnrA (Tp0319; TmpC) lipoprotein represents a new family of bacterial purine nucleoside receptor encoded within an ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-like operon in Treponema pallidum. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 8072–8081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Deka R. K., Brautigam C. A., Tomson F. L., Lumpkins S. B., Tomchick D. R., Machius M., Norgard M. V. (2007) Crystal structure of the Tp34 (TP0971) lipoprotein of Treponema pallidum. implications of its metal-bound state and affinity for human lactoferrin. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 5944–5958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Machius M., Brautigam C. A., Tomchick D. R., Ward P., Otwinowski Z., Blevins J. S., Deka R. K., Norgard M. V. (2007) Structural and biochemical basis for polyamine binding to the Tp0655 lipoprotein of Treponema pallidum: putative role for Tp0655 (TpPotD) as a polyamine receptor. J. Mol. Biol. 373, 681–694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Luthra A., Zhu G., Desrosiers D. C., Eggers C. H., Mulay V., Anand A., McArthur F. A., Romano F. B., Caimano M. J., Heuck A. P., Malkowski M. G., Radolf J. D. (2011) The transition from closed to open conformation of Treponema pallidum outer membrane-associated lipoprotein TP0453 involves membrane sensing and integration by two amphipathic helices. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 41656–41668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Deka R. K., Brautigam C. A., Goldberg M., Schuck P., Tomchick D. R., Norgard M. V. (2012) Structural, bioinformatic, and in vivo analyses of two Treponema pallidum lipoproteins reveal a unique TRAP transporter. J. Mol. Biol. 416, 678–696 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]