Background: Vaccinia protein H5 is a multifunctional protein involved in several aspects of viral replication.

Results: H5 is a nucleic-acid binding, elongated rod-like tetramer with an instrinsically disordered N terminus and an α-helical C terminus.

Conclusion: H5 functions as a hub protein in vaccinia virus replication linking otherwise unique viral processes.

Significance: Understanding the mechanism of H5 function in vaccinia virus replication is crucial for studying vaccinia biology.

Keywords: DNA Binding Protein, Intrinsically Disordered Proteins, Pox Viruses, RNA Binding Protein, Scaffold Proteins, H5, Hub Protein, Sequence Non-specific Nucleic Acid Binding Protein, Vaccinia Virus

Abstract

H5 is a constitutively expressed, phosphorylated vaccinia virus protein that has been implicated in viral DNA replication, post-replicative gene expression, and virus assembly. For the purpose of understanding the role of H5 in vaccinia biology, we have characterized its biochemical and biophysical properties. Previously, we have demonstrated that H5 is associated with an endoribonucleolytic activity. In this study, we have shown that this cleavage results in a 3′-OH end suitable for polyadenylation of the nascent transcript, corroborating a role for H5 in vaccinia transcription termination. Furthermore, we have shown that H5 is intrinsically disordered, with an elongated rod-shaped structure that preferentially binds double-stranded nucleic acids in a sequence nonspecific manner. The dynamic phosphorylation status of H5 influences this structure and has implications for the role of H5 in multiple processes during virus replication.

Introduction

Vaccinia virus is the prototypical and best studied member of the poxvirus family. Members of this family are large (∼200 kb) double-stranded DNA viruses that replicate exclusively in the host cell cytoplasm and therefore encode all the enzymes and factors required for DNA and RNA metabolism (1). Viral transcription is regulated as a temporal cascade with three different classes of transcripts (early, intermediate, and late) (1, 2). Transcription requires a multi-subunit RNA polymerase, several stage-specific transcription factors, and multi-subunit enzymes for cap formation and polyadenylation. Early transcription occurs before viral DNA replication and early gene products serve as factors for viral DNA replication and intermediate transcription. Intermediate and late transcription (collectively termed post-replicative) are coupled to viral DNA replication. Each stage of transcription employs different mechanisms of transcription termination. Early transcription termination requires a cis-acting sequence and several trans-acting factors yielding 5′ and 3′ co-terminal transcripts (3–9). Post-replicative transcription termination results in heterogenous length transcripts, 1–4-kb-long, that are 5′ co-terminal (10). Although several factors have been shown to modulate post-replicative transcription termination, no cis-acting sequence similar to early transcription termination has been identified (11–13). However, a pyrimidine-rich sequence in the coding strand has been identified immediately preceding the 3′ ends of these post-replicative transcripts (14). Viral DNA replication requires a viral DNA polymerase (E9), a heterodimeric processivity factor (A20 and D4), and several other accessory proteins (I3, D5, H5, B1, J2, F4/I4, G5, A22, A50, I6, and A32) that support viral DNA replication either directly or indirectly (1). Viral DNA replication, postreplicative transcription, and virion assembly take place in discrete cytoplasmic sites termed virus factories. Virion assembly and morphogenesis involves the formation of crescent shaped viral membrane structures within factories, followed by packaging of condensed viroplasm and DNA within the viral membranes to form spherical immature virions and immature virions with nucleoids. Proteolysis of major virion structural proteins and metamorphosis of the immature virions with nucleoids into mature virions is required before transport of the mature virions out of the factory. Several viral proteins are required for all of these events (15).

Ongoing investigations of poxvirus RNA metabolism, DNA replication, and virion morphogenesis have consistently highlighted a role for the vaccina H5 protein in all of these processes. H5 is absent from the entomopoxviruses but present in all chordopoxviruses. H5 is a constitutively expressed, 22.3-kDa phosphoprotein that is localized in viral factories and packaged into virions (16–21). H5 is phosphorylated by both viral kinases (F10 and B1) and by cellular kinases; the pattern of its phosphorylation appears to be dynamic and temporally regulated (15, 18). Although the native molecular mass of the H5 polypeptide based on its amino acid sequence is only 22 kDa, this protein behaves aberrantly in several biochemical estimations of molecular weight, suggesting that it may exhibit transient polymorphic structures. H5 fractionates on SDS-PAGE at 35 kDa; this anomaly has been attributed to a rigid amphipathic helix located in the C terminus of the protein and/or to a proline-rich domain in the N terminus capable of producing kinks in the protein structure (18, 19). Another unusual characteristic of the purified protein is that it elutes from gel filtration columns with an extremely large apparent molecular mass (>400 kDa) regardless of the source of purified protein (vaccinia-expressed or Escherichia coli-expressed), suggesting multimerization of the protein and possibly an unusual shape/structure (22).

There is substantial evidence to suggest that H5 is involved in viral DNA replication. H5 interacts with viral DNA replication enzymes A20, the viral DNA polymerase processivity factor and B1, the viral protein kinase that inhibits the host antiviral protein, BAF, during viral DNA replication (23, 24). A temperature-sensitive mutant (Dts57) that maps to the H5 gene has been characterized to have a block in viral DNA replication (DNA-negative) confirming a direct role for H5 in viral DNA replication (25).

In addition to playing a role in DNA replication, H5 has been shown to function in all aspects of post-replicative transcription: initiation, elongation, and termination. Kovacs and co-workers (20) have shown that H5 possesses a post-replicative stimulatory activity in vitro. In addition, several studies (23, 26, 27) have shown that this protein interacts with viral late transcription initiation (A2 and G8), elongation (G2), and termination (A18) factors. Importantly, an H5 mutant has been isolated that is resistant to isatin β-thiosemicarbazone, an antipoxvirus drug known to affect vaccinia postreplicative gene elongation, further cementing a role for H5 in postreplicative gene transcription (28). As mentioned earlier, post-replicative transcription termination results in 3′ heterogenous length transcripts. However, at least four late genes have been identified to yield transcripts that have homogenous 3′ ends (29–33). For two of these exceptions (ATI and F17R), the uniform 3′ ends are generated by post-transcriptional site-specific endoribonucleolytic cleavage. We have characterized the vaccinia H5 protein as being associated with this activity, suggesting a role for H5 in late transcription termination (22). This cleavage was characterized to be possibly RNA sequence or structure specific, and phosphorylation was determined to be essential for cleavage activity.

Consistent with an apparent role for H5 in viral DNA replication and post-replicative transcrition, published data suggest that H5 is a nucleic acid binding protein with affinity for both DNA and RNA (18, 20, 34, 35). Vaccinia-expressed H5 was purified using either single-stranded or double-stranded DNA cellulose columns in these studies (18, 20, 34). However, an extensive study characterizing this binding has not been performed.

Finally, a role for H5 in virion morphogenesis is evident by phenotypic analysis of two temperature-sensitive mutants, tsH5–4 and Dts57 (25, 36). Data from these studies indicate that H5 is involved in multiple steps of viral morphogenesis, including membrane biogenesis, encapsidation of viroplasm to form immature virions, and maturation of immature virions into mature virions.

In the current study, we have characterized the biochemical and biophysical properties of H5 and propose that H5 functions as a hub/scaffold protein that links otherwise discrete vaccinia virus processes. To understand the role of H5 in post-replicative transcription termination, we have determined the nature of 3′ ends during the endoribonucleolytic cleavage reaction and determined that H5-associated cleavage results in a 3′-OH end. We have further defined the nucleic acid binding properties of the H5 protein and shown that this protein can bind nucleic acids with high affinity in a sequence nonspecific manner requiring a minimum of 40 nt. Using structure modeling, circular dichroism, sedimentation equilibrium, and small-angle x-ray scattering (SAXS),2 we have demonstrated that the basic structure of unphosphorylated H5 protein is an elongated rod-like tetramer with the intrinsically disordered N terminus of each subunit contributing to its rod-like structure. Phosphorylation of the protein likely causes aggregation of H5 tetramers to form higher order complexes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Eukaryotic Cells, Viruses, and Bacterial Hosts

BSC40 cells, wild type vaccinia strain Western reserve (WR), and the conditions for their growth and infection have been described previously (37–41). HeLa S3 cells were grown in suspension culture in Eagle's minimal essential medium (Joklik's modification) containing 5% calf serum and 2% fetal calf serum. E. coli BL21(DE3) harboring the plasmid pET14b and containing the H5 ORF was a gift from Dr. Paula Traktman.

EhisH5 is a recombinant vaccinia virus that contains the 10x His and factor Xa sequences (MGHHHHHHHHHHSSGHIEGRH) from plasmid pET16b at the N terminus of the endogenous H5R. For the construction of ehisH5, BSC40 cells were infected with Dts57-WR virus (Dts57-WR is a reconstructed temperature-sensitive virus in the WR background that contains the Dts57 lesion, G189R in the C terminus of the WR-H5 protein) and transfected with a PCR product that contained the H4R-H5R region of vaccinia WR with the pET16b polyhistidine and factor Xa sequence inserted at the N terminus of H5R. Infection transfection was carried out at 37 °C to select for recombinant WT virus. The harvested lysates were then plaque assayed. Several plaques were picked and analyzed by Western blotting using an anti-His monclonal antibody (Novagen). Plaque lysates that tested positive by Western blotting were then propagated in cell culture and the sequence of His-tagged H5 was confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Purification of His-H5 Protein

The purification schemes for vaccinia-expressed and E. coli-expressed His-tagged H5 proteins were as described previously (22). For further purification by gel filtration, the H5 protein eluted from the nickel affinity column (His-Trap, GE Healthcare) was pooled, concentrated using an Amicon concentrator (Ultra cel 5K; Millipore) to ≤500 μl and applied to a Superdex 200 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7, containing 1 m NaCl and protease inhibitor mixture (1:100, Sigma). (This buffer also contained 5% glycerol and/or 2 mm DTT in situations where these reagents did not affect downstream events.) Molecular weight standards (high and low molecular weight standards; Amersham Biosciences) were used to calibrate the gel filtration column.

Determining the Nature of 3′ Ends of H5 Cleaved RNA

The cleavage substrate (430-nt ssRNA) was prepared by in vitro transcription and uniformly labeled with 32P α-CTP as described previously (33). The 430-nt RNA substrate was either directly used in the cleavage assay or 30 pmol of RNA were incubated at 30 °C for 10 min with 30 units of tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (TAP; Epicenter, 10 units/μl) in a total volume of 6.6 μl. Cleavage was carried out under standard cleavage conditions as described previously by incubating 10 fmol of RNA substrate with vaccinia-expressed nickel affinity-purified H5 protein in a reaction containing 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8, 7.5 mm MgCl2, and 300 mm NaCl for 1 h at 30 °C (33). The reactions were then treated with either 1 unit of Terminator exonuclease (Epicenter) or buffer (as control) for 2 h at 37 °C. Following Terminator exonuclease treatment, 30 μl of formamide-loading buffer was added, and the samples were denatured at 90–95 °C for 5 min, flash cooled, centrifuged, and loaded on a 6% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 m urea (Sequagel, National Diagnostics). The gels were then fixed, dried, and analyzed using the STORM PhosphorImager and ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare). For [5′-32P]pCp labeling, the cleavage substrate was prepared using the RNA megascript kit (Ambion) to yield large quantities of “cold” substrate. The substrate was then cleaved with vaccinia-expressed nickel affinity-purified H5 protein under the conditions mentioned above. The residual substrate and the cleaved products were then purified using phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol purification and resuspended in nuclease-free water. This RNA (and RNA not subjected to the cleavage reaction) was then labeled in a reaction containing 150 μCi of [5′-32P]pCp (3000 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer Life Sciences) and 10 units of RNA ligase (New England Biolabs) at 4 °C overnight. The labeled RNA was then purified using phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol purification. The pellets were resuspended in 10 μl of formamide-loading dye and denatured at 90–95 °C for 5 min, flash cooled, centrifuged, and loaded on a 6% polyacrylamide gel containing 8 m urea (Sequagel, National Diagnostics). The gels were then processed as described above.

Filter Binding Assays

Double sandwich filter binding assays were carried out following instructions of Lohman and Wong (42) with some modifications. One hundred microliter reactions were prepared in duplicate by equilibrating various concentrations of E. coli-expressed H5 (or vaccinia-expressed H5) with 10–100 pm nucleic acid (1 μl/reaction containing 1–10 fmol nucleic acid of different lengths and sequence as described under “Results”) on ice in rinse buffer (25 mm HEPES, pH 7.5, 50 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, 5 mm DTT) containing 10 μg of BSA. After 30 min, 90 μl of the reaction mixture was vacuum filtered through a nitrocellulose (Bio-Rad) and nylon membrane (Hybond N+, GE Healthcare) sandwiched within a Schleicher and Schuell minifold. An equal volume of rinse buffer was then filtered through to rinse out the wells. The membranes were then separated, dried, and analyzed using a STORM PhosphorImager and ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare). The percentage of nucleic acid binding to the nitrocellulose membrane was computed from these results and plotted against increasing concentrations of H5 protein using GraphPad Prism software to estimate a dissociation constant (KD) for each binding reaction. The KD for each experiment was determined using technical duplicates and the results shown are from at least two different experiments. All of the optimization data shown in Fig. 2 were obtained using 100 pm 32P-labeled ssRNA (430 nt; uniformly labeled) and vaccinia-expressed H5 protein (ehisH5). Experiments at pH 6 were done in MES buffer, those at pH 7–8 were done in HEPES, and those at pH 10 were done in 3-(cyclohexylamino)propanesulfonic acid buffer. The pH of all buffers was adjusted either with HCl or NaOH. 5′-Cy5-tagged nucleic acids (Sigma Genosys) of varying lengths were used in the binding experiments that determined length dependence of H5 binding. All 32P-labeled substrates were gel-purified; 5′-Cy5-tagged substrates were obtained PAGE-purified from the manufacturer. For the preparation of double-stranded 5′-Cy5-tagged nucleic acids, complementary sequences of equal lengths and concentration were mixed in 1× TE buffer containing 50 mm NaCl and annealed by heating to 100 °C for 10 min in a Thermocycler. The temperature was then decreased to 4 °C gradually using a gradient of 1 °C/min. The hybrids were then analyzed on non-denaturing polyacrylamide gels. Greater than 95% of the annealed oligonucleotides were observed as double-stranded molecules and, therefore, these hybrids were not gel-purified.

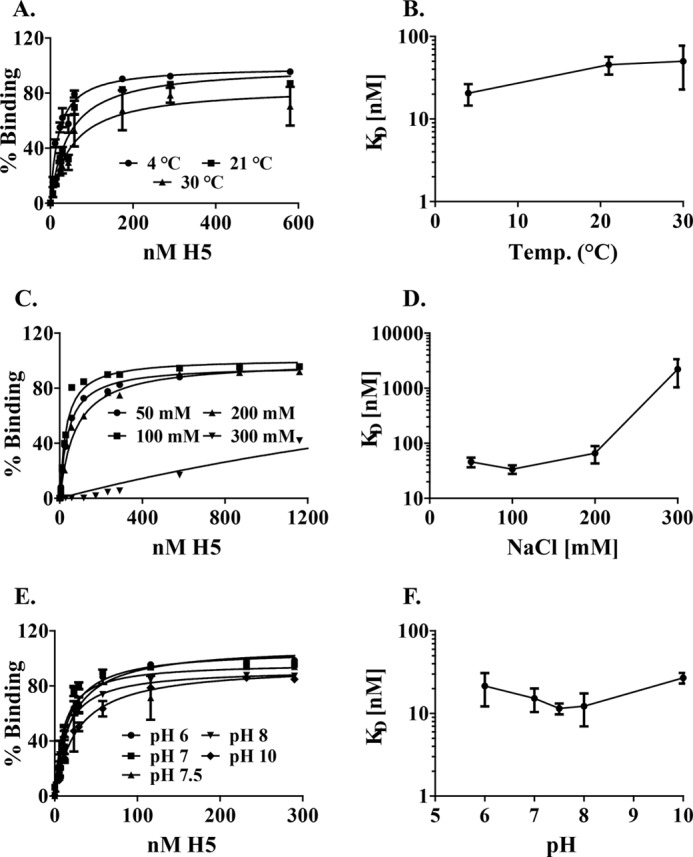

FIGURE 2.

Optimization of the conditions of nucleic acid binding. A and B, effect of temperature on nucleic acid binding. A, equilibrium binding curve for H5 binding to 430nt ssRNA at 4 °C (ice), 21 °C (room temperature), and 30 °C. The data plotted are from four replicates, and the mean and S.E. are plotted. B, temperature dependence of KD. Dissociation constants for H5 binding were plotted as a function of the temperatures tested in the assay. C and D, effect of salt on nucleic acid binding. C, equilibrium binding curves for H5 binding to 430-nt ssRNA between 50–300 mm NaCl. The data plotted are from four replicates, and the mean and S.E. are plotted. D, salt dependence of KD. Dissociation constants for H5 binding were plotted as a function of the salt concentration tested in the assay. E and F, effect of pH on nucleic acid binding. E, equilibrium binding curves for H5 binding to 430-nt ssRNA between pH 6–10. The data plotted are from four replicates, and the mean and S.E. for each point are plotted. F, pH dependence of KD. Dissociation constants for H5 binding were plotted as a function of the pH tested in the assay.

Intrinsic Disorder Prediction and Homology Modeling

The PONDR-Fit algorithm was used to calculate the intrinsic disorder disposition in vaccinia H5 protein (43). The PONDR-Fit intrinsic disorder disposition versus residue number plot was scaled by sequence alignment to the published sequence of H5 (vaccinia WR) to better compare the different regions on the H5 monomer. Homology models of H5 were also made based on the published H5 sequence (WR) using the ROBETTA server (44). These were combined and a composite H5 model made, H5model.

CD

The CD data were collected on an Aviv 414 CD spectrometer. The data were collected between 200 and 260 nm at 25 °C. Three hundred and fifty microliters of sample were used at 0.4 mg/ml of H5. The data, collected in triplicate, were averaged across the 50 scans and the triplicate experiments to improve the signal to noise ratio. The averaged data were then scaled to molar ellipticity values to account for concentration differences and to compare with other CD spectra. The collected data were processed using in-house algorithms to determine the secondary structural propensity of H5 (45).

SAXS

The SAXS data were collected at the Cornell High Energy Synchrotron Source MacCHESS G1 beamline. The data were collected at a wavelength of 1.444 Å (8.58 keV). Twenty-five second exposures were used at a detector distance of 800 mm to collect data between q values of 0.008 and 0.3 nm−1. Two milligrams per milliliter sample concentrations were used with 30 μl of sample volume in plastic cuvettes. 10× and 20× attenuation levels were used to achieve optimum signal to noise ratio while at the same time having minimal radiation damage to the sample. The images were processed for intensity and q values using the DATASQUEEZE (University of Pennsylvania) and BioXTAS RAW programs (46).

The ATSAS suite of programs was used to further process the data after raw image processing (47). GNUPLOT was used for data plotting and radius of gyration (Rg) calculations. Pairwise distribution functions and radius of gyration values were calculated using the GNOM program from the ATSAS suite. DAMMIN was used to generate the three-dimensional ab initio model. Ten DAMMIN simulations were averaged using the DAMAVER program to generate a final density profile. This was converted to a SITUS volume map for docking purposes and the H5model was docked manually into the map using the CHIMERA program (48). Theoretical SAXS curves from the H5model structure of the monomer and possible multimers were computed using the CRYSOL. GNOM, DAMMIN, DAMAVER, and CRYSOL are all located within the ATSAS suite. All visualizations were made using University of California, San Francisco Chimera.

Sedimentation Equilibrium Ultracentrifugation

Sedimentation equilibrium were performed using absorption optics in a Beckman XLA analytical ultracentrifuge at 4 °C in 25 mm Tris, 1 m NaCl, and 2 mm DTT, pH 7, and analyzed as described previously (49, 50). Absorption was measured at 280 nm as a function of radius for samples of 100 and 150 μl. The gradient was invariant for 24 h after equilibrium was achieved at 6,200 rpm, and then additional equilibrium data were obtained at 13,200. Samples were examined after the run by SDS-PAGE and showed no evidence of degradation. The subunit partial specific volume was estimated from the amino acid content. The four sets of data (two samples of different volumes, each at two different angular velocities) were fit simultaneously with fitting parameters of c, the concentration at the base of the centrifuge cell for each data set, and M, the mass. The Marquard-Levenberg method was employed for nonlinear, least-squares curve fitting.

RESULTS

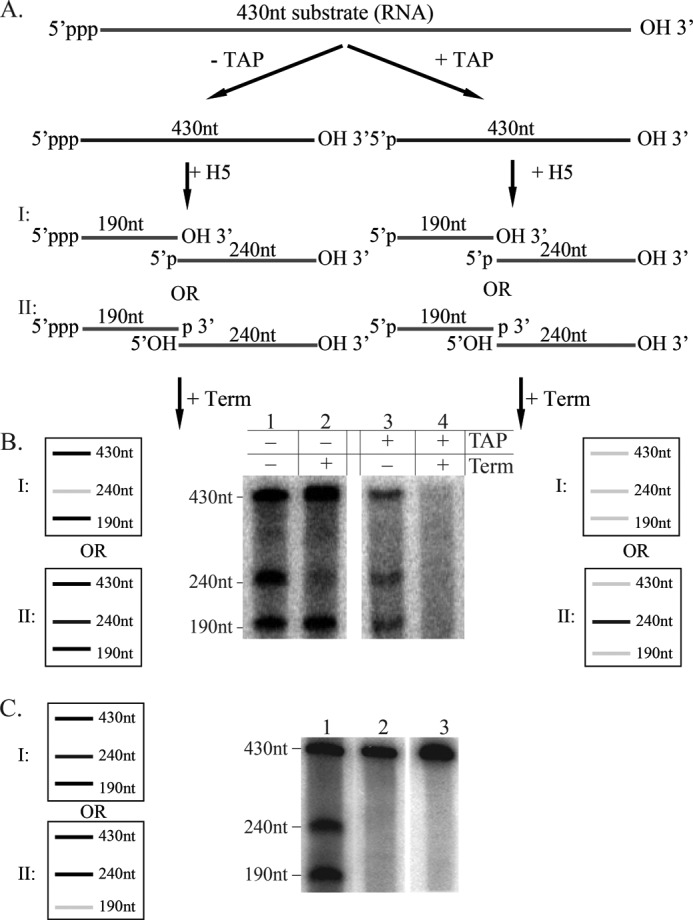

The Nature of 3′ Ends Generated by H5 Cleavage of RNA

We have shown that vaccinia virus protein, H5 is associated with endo-ribonucleolytic cleavage of at least two homogenous late transcripts (ATI and F17) in vitro (22). Furthermore, because H5-associated cleavage activity is postulated to function at the level of vaccinia post-replicative termination (22), we hypothesize that cleavage would result in a free 3′-hydroxyl end unlike most RNases, including RNase A and T1, which cleave RNA to yield a 3′ phosphate. The substrate for H5-associated cleavage is a 430-nt uniformly labeled, in vitro-synthesized ssRNA with a 5′-triphosphate. Cleavage of this RNA yields two products: the upstream product is 190 nt in length, and the downstream product is 240 nt in length (Fig. 1A). The cleaved products and the residual substrate are routinely fractionated on a polyacrylamide gel, and the results are analyzed by phosphorimaging analyses as shown in Fig. 1B. To determine the nature of the 3′ ends during the H5-associated cleavage reaction, we treated the H5 cleavage products with Terminator exonuclease, an RNase that degrades 5′-monophosphate RNA in a 5′ → 3′ orientation (Fig. 1B). Additionally, as a control for Terminator exonuclease activity, we treated the 430-nt ssRNA substrate with tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (+TAP) to yield a 5′-monophosphate 430-nt ssRNA. If H5-associated cleavage of the 430-nt ssRNA substrate results in a 5′-PO4 (scenario I) on the downstream cleavage product, treatment with Terminator exonuclease (−TAP) will cause degradation of the 240-nt downstream product of H5 cleavage but not of the 430-nt substrate and the 190-nt upstream product (outcome I). This result was observed in lane 1 (Fig. 1B), indicating that H5-associated cleavage results in a 5′-PO4. However, if the 430-nt ssRNA substrate is first treated with tobacco acid pyrophosphatase (+TAP) prior to the H5-associated cleavage, the 430-nt ssRNA substrate will also have a 5′-monophosphate. Under these conditions, if H5-associated cleavage of the 430-nt ssRNA substrate results in 5′-PO4 (scenario I), treatment with Terminator exonuclease will degrade both the substrate and the two cleavage products (outcome I). This result was observed in lane 4 (Fig. 1B), confirming that H5-associated cleavage of the ssRNA substrate results in a 5′-PO4. To confirm these data, we also analyzed the H5-cleaved products for the presence of a 3′-OH on the upstream H5 cleavage product (190 nt). To do so, we prepared unlabeled (cold) 430-nt ssRNA substrate in vitro and treated it with cleavage-competent H5 or enzyme dilution buffer under the normal conditions for H5-associated cleavage as mentioned previously. The residual substrate and the two cleaved products from H5 or control reactions were then purified and labeled with [5′-32P]pCp using RNA ligase (Fig. 1C, lanes 1 and 2). Cleavage substrate not subjected to the cleavage reaction was also labeled as described above (Fig. 1C, lane 3). Because H5-associated cleavage results in a 3′-OH as determined in Fig. 1B, we observed 32P-labeling of residual substrate and both cleaved products as shown in Fig. 1C, lane 1, confirming that H5-associated cleavage of the ssRNA substrate results in a 3′-OH.

FIGURE 1.

Endoribonucleolytic cleavage with purified H5 protein results in a 3′-OH. A, schematic of potential cleavage products for the TAP-treated (+TAP) or untreated (−TAP) 430-nt ssRNA substrate. I and II, possible scenarios depending on the nature of 3′ ends after cleavage. Ends denoted in boldface type indicate possible results of cleavage. B, schematic of the potential and actual products after treatment of the cleavage reaction with Terminator exonuclease (Term). I and II, possible outcomes depending on the nature of 3′ ends after cleavage. Gray line, RNA degraded by Terminator; black line, RNA not degraded by Terminator. C, schematic of the potential and actual products after [5′-32P]pCp treatment of unlabeled, purified RNA substrate and products from a cleavage reaction. Black line, RNA labeled with [5′-32P]pCp; gray line, RNA not labeled with [5′-32P]pCp. Lane 1, RNA substrate treated with H5 in cleavage assay, purified, and labeled with [5′-32P]pCp; lane 2, RNA substrate treated with buffer in cleavage assay, purified, and labeled with [5′-32P]pCp; lane 3, RNA substrate labeled with [5′-32P]pCp.

Protein-Nucleic Acid Interaction

There is some evidence that H5 is a nucleic acid binding protein (18, 20, 34). Given the role of H5 in both DNA and RNA metabolism, we were interested to determine the parameters of H5-nucleic acid interaction. In addition, to better understand the function of its nucleic acid binding characteristics, we determined whether H5 has a preference for one type of nucleic acid over another. To determine the binding affinity of H5 for each nucleic acid, we employed the double-sandwich filter binding assay based on the method of Wong and Lohman (42) and as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Given that vaccinia-expressed H5 (but not E. coli-expressed H5) is associated with endoribonucleolytic cleavage, we first analyzed the binding of vaccinia-expressed H5 to the in vitro-generated 430-nt ssRNA cleavage substrate and to its reverse complement, which is not a substrate for cleavage (33). Both substrates bound vaccinia-expressed (cleavage competent) affinity-purified H5 protein comparably and with high affinity (KD, 4–45 nm), suggesting that binding of H5 to nucleic acid is nucleic acid sequence-independent (data not shown). Additionally, we showed that both vaccinia-expressed (cleavage competent) and E. coli-expressed (cleavage incompetent) affinity-purified H5 bound the 430-nt ssRNA cleavage substrate with comparable affinities (KD, 10–50 nm), suggesting that nucleic acid binding and cleavage activity are discrete events (data not shown).

Interaction Parameters

Effect of Temperature on Binding

To determine the optimal temperature for studying the nucleic acid binding properties of H5, we analyzed the binding of affinity-purified, vaccinia-expressed H5 to the 430-nt ssRNA cleavage substrate at three different temperatures (Fig. 2A). The KD of binding at the three temperatures were as follows: 20.5 ± 6.0 nm (ice); 45.5 ± 11.1 nm (room temperature); and 50.0 ± 27.2 nm (30 °C). A plot of these dissociation constants as a function of temperature (Fig. 2B) suggests that temperature did not drastically affect the affinity of H5 for this RNA. Because the KD of the reaction was lowest when the binding reaction was incubated on ice, we have used this temperature for the remainder of the filter binding assays

Effect of Salt on Binding

Given that binding of H5 to the cleavage substrate was sequence-independent; we examined the role of electrostatic interactions in the binding of H5 to the 430-nt ssRNA substrate as a function of ionic strength using 50–500 mm NaCl. No binding was observed in 500 mm salt at the concentrations of H5 tested (data not shown). The binding of H5 to the RNA substrate at salt concentrations between 50–300 mm is shown in Fig. 2C. A plot of these dissociation constants (Fig. 2D) as a function of salt concentration shows that at salt concentrations over 200 mm, the KD increases significantly, suggesting that electrostatic forces play an important role in stabilizing the binding of H5 to the RNA substrate. We have used 50 mm NaCl in characterizing the remainder of the binding conditions.

Effect of pH on Binding

To determine the role of titratable groups in the interaction of H5 with ssRNA, we determined the KD for this interaction at pH values ranging from 6–10 (Fig. 2E). The difference in KD at these pH values were not significant (Fig. 2F), indicating that the groups titratable in this pH range do not play a role in stabilizing the interaction of H5 with nucleic acid. HEPES buffer, pH 7.5, was chosen as the buffer for characterizing the rest of the binding conditions.

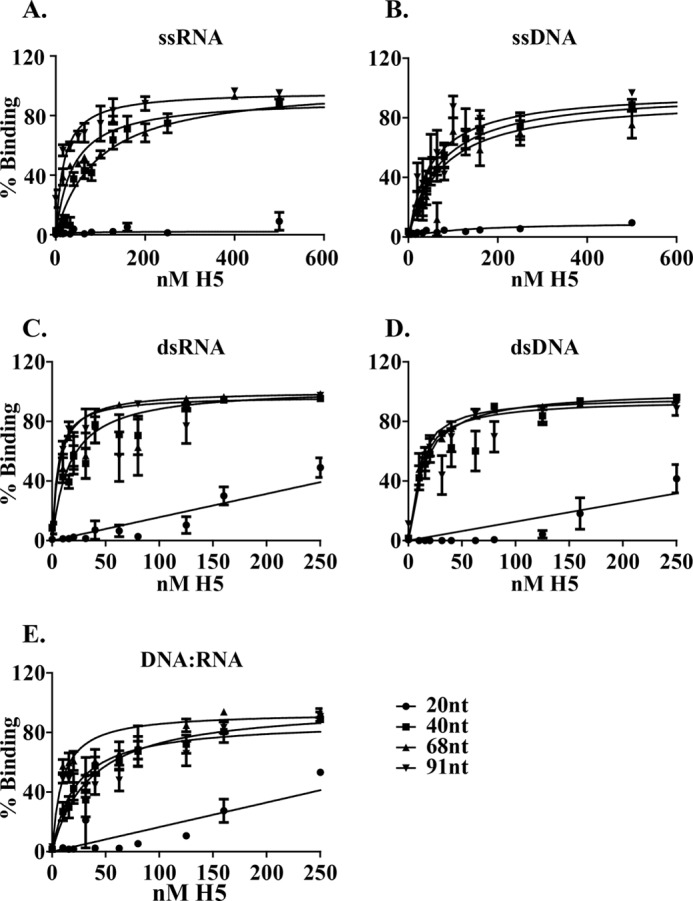

Substrate Specificity

Next, we compared the affinity of H5 for single-stranded and double-stranded DNA and RNA. Fig. 3 shows the saturation curves of H5 binding to 20-, 40-, 68-, and 91-nt length oligomers of ssDNA, ssRNA, dsDNA, dsRNA, and DNA:RNA hybrids. Because the binding of cleavage competent vaccinia-expressed H5 and cleavage incompetent E. coli-expressed H5 to nucleic acid was comparable, we used E. coli expressed H5 for the remainder of the binding experiments. Additionally, the nucleic acid substrates for this set of experiments were synthesized with a Cy5 label on the 5′ end of the nucleic acid oligomer. For all of the nucleic acids tested, H5 was unable to bind with high affinity to any of the 20-nt nucleic acid oligomers. Additionally, the binding of H5 to the 20-mer of every set of nucleic acid oligomers tested was significantly different from the binding to the 40–91-mers within the same set (p ≤ 0.0001). The average dissociation constants (between 6 and 18 replicates were averaged for each data set) for H5 binding to each oligomer in all five sets of nucleic acids are shown in Table 1. Using the unpaired Student's t test, we determined that with the exception of ssRNA, within a given set, the dissociation constants for H5 binding to lengths of 40–91-nt oligomers were not significantly different from each other based on 95% confidence (p ≥ 0.16). For ssRNA, there appeared to be a significant difference in dissociation constants (p = 0.01) between H5 binding 40-nt ssRNA versus 91-nt ssRNA only. Therefore, excluding the data obtained for the 20-mers, we calculated a mean KD for H5 binding to each of the nucleic acid polymers as shown in Table 1 and in supplemental Fig. 1 using row mean statistics. The binding affinity of H5 to the five different sets of nucleic acid polymers sorted themselves into three categories. The KD was the lowest for binding of H5 to dsDNA (13.9 ± 1.6 nm) and dsRNA (11.7 ± 2.1 nm), intermediate for DNA:RNA hybrids (21.4 ± 3.9 nm) and the highest for H5 binding to ssDNA (62.9 ± 8.8 nm) and ssRNA (44.2 ± 10.4 nm). The binding of H5 to double-stranded nucleic acids (DNA and RNA) was significantly different from binding to single-stranded nucleic acids and both these categories were significantly different from binding to DNA:RNA hybrids (supplemental Fig. 1). The data indicate that H5 preferentially binds homoduplexed nucleic acids best, followed by heteroduplexed nucleic acid. The binding to single-stranded nucleic acids in comparison was weakest.

FIGURE 3.

Equilibrium curves for H5 binding to different lengths of nucleic acid oligomers. The KD for each curve is computed with data obtained from at least three individual experiments with each experiment done in duplicate, and the mean and the S.E. for each data point is plotted. A, ssRNA; B, ssDNA; C, dsRNA; D, dsDNA; E, DNA:RNA hybrids.

TABLE 1.

Dissociation constants for H5 binding to different lengths of nucleic acid

The 20-nt curves did not reach saturation at the concentrations of H5 tested (ND, not determined).

|

KD (nm) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 nt | 40 nt | 68 nt | 91 nt | Mean KD (40–91 nt) | |

| ssRNA | ND | 94.8 ± 16.2 | 39.2 ± 5.8 | 18.0 ± 3.7 | 44.2 ± 10.4 |

| ssDNA | ND | 69.5 ± 10.8 | 75.3 ± 15.8 | 51.8 ± 10.0 | 62.9 ± 8.8 |

| dsRNA | ND | 16.4 ± 1.5 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | 5.3 ± 0.8 | 11.7 ± 2.1 |

| dsDNA | ND | 13.7 ± 1.0 | 8.8 ± 0.8 | 9.8 ± 1.7 | 13.9 ± 1.6 |

| DNA:RNA | ND | 35.5 ± 6.7 | 9.2 ± 1.3 | 21.8 ± 4.4 | 21.4 ± 3.9 |

Biophysical Properties of H5

Structure and Modeling

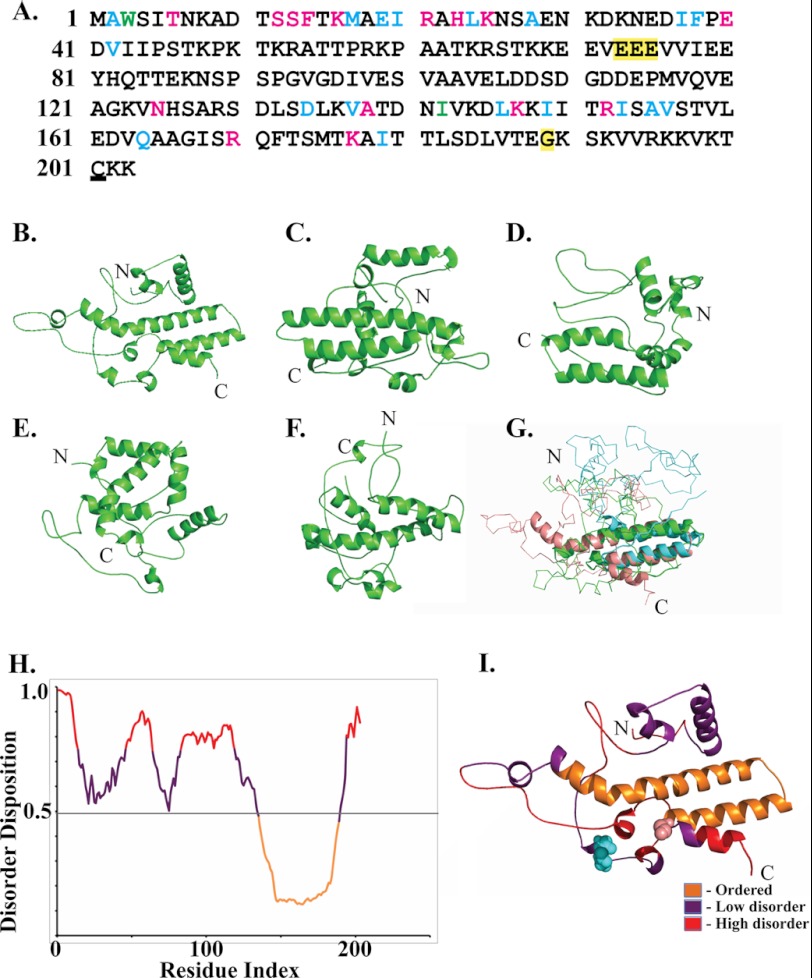

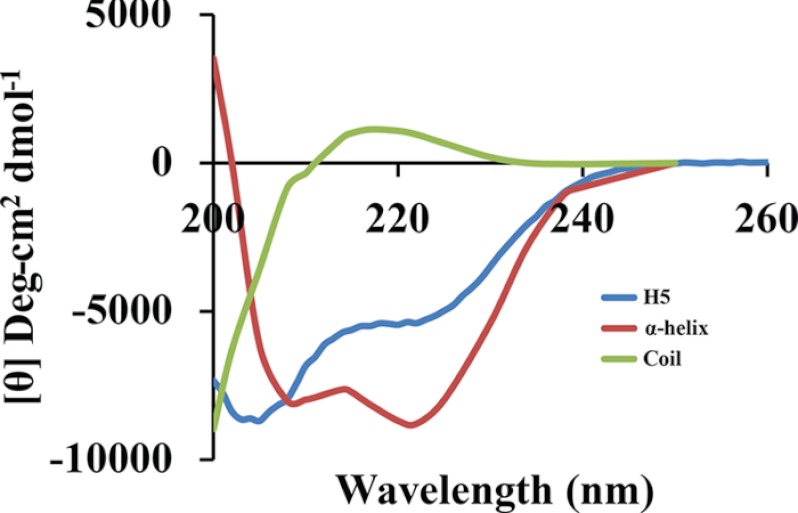

H5 is phosphorylated and consists of 203 amino acids. Potential sites of phosphorylation include 18 serines, 19 threonines, and 1 tyrosine interspersed through the length of the protein. A single cysteine is present at the C terminus of H5 (Fig. 4A). Within the poxvirus family, H5 is present in the chordopoxviruses but absent from the entomopoxviruses. Among the chordopoxviruses, different H5 orthologs within the orthopoxvirus genera show strong conservation (data not shown). However, only a modest conservation is observed for the H5 orthologs within different genera of the chordopoxviruses. The H5 polypeptide sequence for representatives from each chordopoxvirus genera were aligned using the multiple sequence alignment software, MUSCLE at the European Bioinformatics Institute website (supplemental Fig. 2). Significant conservation was observed in the most N-terminal region and in the C terminus of the protein, whereas the middle region of H5 (between residues 50–120) appeared non-conserved but high in charged residues. A tertiary structure of H5 was generated using the homology modeling program ROBETTA (Fig. 4, B–G). Five models were generated based on the sequence (Fig. 4, B–F). The models all showed an α-helical propensity at the C terminus and a mixed/helix motif loop through the remainder of the structure. Fig. 4G shows a structural superimposition of three best fit models (models depicted in Fig. 4, B–D) and highlights the conserved α-helices predicted in the C terminus of H5 and ∼ 50% of the N terminus as unstructured or disordered. Previously, we observed that purified H5 (both cleavage-competent and -incompetent) eluted from a gel filtration column with a significantly large apparent molecular mass (∼460 kDa), suggesting either complex formation or a non-globular structure (22). To further analyze these findings, the protein sequence of H5 was examined using the PONDR-Fit algorithm that predicts the degree of disorder in the secondary structure of a protein (Fig. 4H). The PONDR-fit algorithm predicted a high intrinsic disorder disposition in the N-terminal region of the H5 protein, shown as loops in the homology model (Fig. 4I). Experimentally, these data were confirmed using circular dichroism (Fig. 5). Secondary structural propensity as determined by the CD data processing indicated a 50% α-helix and a 50% random coil propensity, which are in agreement with the homology models. Interestingly, the CD data also showed a profile consistent with an intrinsically disordered or unstructured protein.

FIGURE 4.

Structural modeling of H5. A, sequence of the WR strain of H5. Nineteen serines and 20 threonines are interspersed throughout the sequence. The single cysteine residue in the C terminus is underlined. An alignment of the H5 polypeptide sequence from representative H5 orthologs within the chordopoxvirus (supplemental Fig. 2) indicates that the residues in green are identical, residues in cyan are highly conserved, and residues colored magenta are weakly conserved. The mutations in tsH5–4 (EEE to AAA) and Dts57 (G187A) are highlighted. B–F, homology models of H5. Five independent tertiary structures for the H5 protein were modeled by analyzing the H5 protein sequence using the ROBETTA server. G, consensus H5 model, H5model (based on models B–D obtained by least squares structure superposing using the program COOT). H, intrinsic disorder in H5 determined using the PONDR-Fit algorithm and scaled to align to the H5 sequence. The degree of disorder disposition is plotted as a function of the amino acid residue from the N to C terminus of the protein. A threshold of 0.5 is used to indicate a high level of disorder. I, homology model of H5 in B depicted with the degree of disorder in the structure. The position of the Dts57 mutation is indicated in pink, and the tsH5–4 mutations are indicated in cyan.

FIGURE 5.

Circular dichroism spectra of H5. The molar ellipticity values of H5 are plotted as a function of the wavelength between 200–260 nm and compared with the spectra for α-helix and coil structures.

H5 Has an Unusual Structure

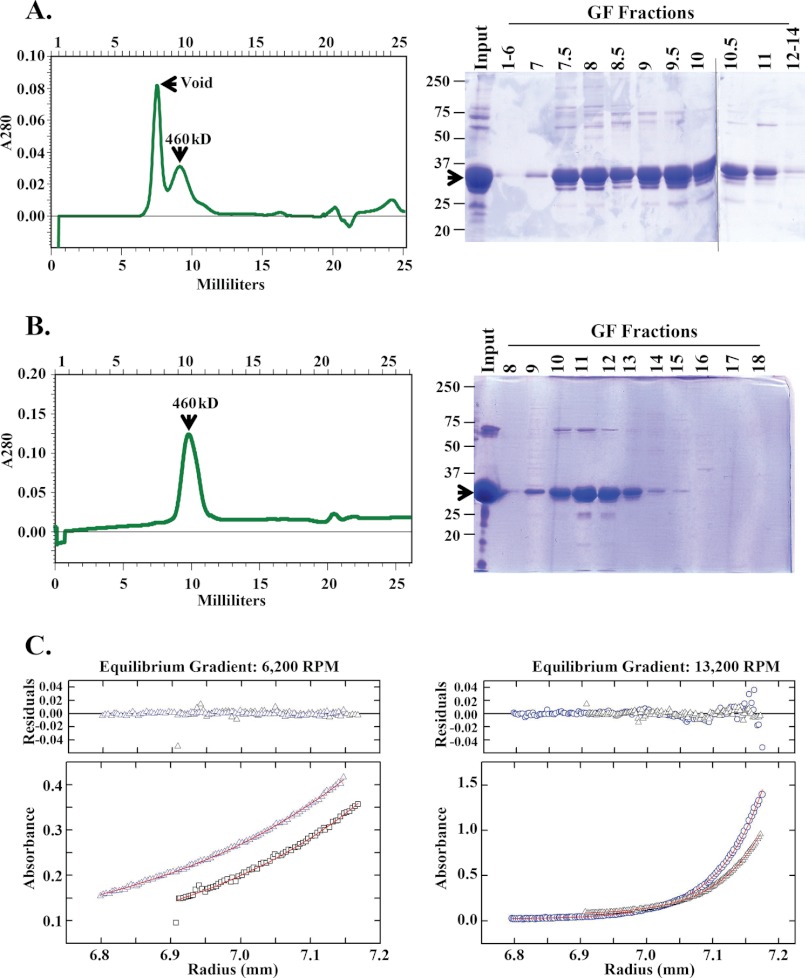

We chromatographed vaccinia-expressed, affinity-purified H5 over Superdex 200, a gel filtration resin that separates globular proteins between 3 and 650 kDa. Two distinct peaks, one in the void volume and the other at ∼460 kDa, were reproducibly observed. Interestingly however, affinity-purified, E. coli-expressed H5 elutes reproducibly with a single peak at ∼460 kDa when applied to the same gel filtration column. Representative chromatograms and Coomassie-stained fractions from these columns are shown in Fig. 6, A and B, respectively. It is noteworthy that vaccinia-expressed H5 has a complex pattern of phosphorylation as compared with E. coli-expressed H5, which is most likely unphosphorylated. Therefore, we hypothesize that although both the vaccinia-expressed and E. coli-expressed H5 have the propensity to form higher order structures, vaccinia-expressed H5 must have a different molecular structure than E. coli-expressed H5 and forms even larger structures than E. coli-expressed H5. To test this hypothesis, we used an independent biophysical measurement of mass, sedimentation equilibrium ultracentrifugation. Gel filtration-purified H5 fractions that eluted with a molecular mass of 460 kDa were pooled, concentrated, and analyzed at two different concentrations and two different g forces. The absorbance of the protein at different radii in the centrifuge cell was measured, and the data were plotted as a function of the distance from the top of centrifuge cell (Fig. 6C). The behavior of the 460-kDa fractions of E. coli-expressed H5 in the centrifuge was ideal: soluble, homogenous, and stable. Globally fitting the data from two samples of different concentrations at two different g forces and forcing M = 22,300 × 4 (molecular mass of H5 is 22,300 Da) gives residuals that show no measurable systematic error. Alternatively, fitting to M for all samples simultaneously gives M = 91 ± 2 kDa (Fig. 6C; partial specific volume, 0.721; and density ρ20, 1.0053). These data suggest that E. coli-expressed H5 exists as a homogenous tetramer. The 460-kDa gel filtration fractions of vaccinia-expressed H5 and the peak of H5 protein in the void volume were also similarly analyzed (data not shown). The H5 in the void peak appeared to be completely aggregated and sedimented at the bottom of the centrifuge cell even at the lowest g force applied. The behavior of the 460-kDa gel filtration fractions of vaccinia-expressed H5 was also not ideal; it appeared heterogeneous with the tetrameric form being the primary structure. However, higher order structures, including octamers, were also identified in this preparation. These data suggest that the basic structure of the H5 protein is tetrameric with a tendency to form higher order complexes as a result of phosphorylation.

FIGURE 6.

H5 transient polymorphic structures. A, gel filtration profile for vaccinia-expressed, affinity-purified H5 protein. Left, chromatogram showing the two peaks of H5 protein, one in the void and one at 460 kDa. Fraction numbers are indicated on the top of the chromatogram. Right, Coomassie-stained gel of fractions. H5 is indicated with an arrow. A molecular mass ladder in kDa is shown at the left of gel. B, gel filtration profile for E. coli-expressed purified H5 protein. Left, chromatogram with a single peak of H5 protein at 460 kDa. Fraction numbers are indicated on the top of the chromatogram. Right, Coomassie-stained gel of fractions. H5 is indicated with an arrow. Molecular mass markers in kDa are shown on the left of the gel. C, sedimentation equilibrium ultracentrifugation of gel filtration purified E. coli-expressed H5 protein (fraction 11 from plate B). Two different concentrations of H5 protein were each centrifuged at two different g forces. The A280 values of the protein at the different radii in the centrifuge cell are plotted as a function of the distance from the top of the cell. Left, 6200 rpm; Right, 13,200 rpm. The residuals from fitting all of the data simultaneously to M = 91,000 are plotted on the top for each gradient.

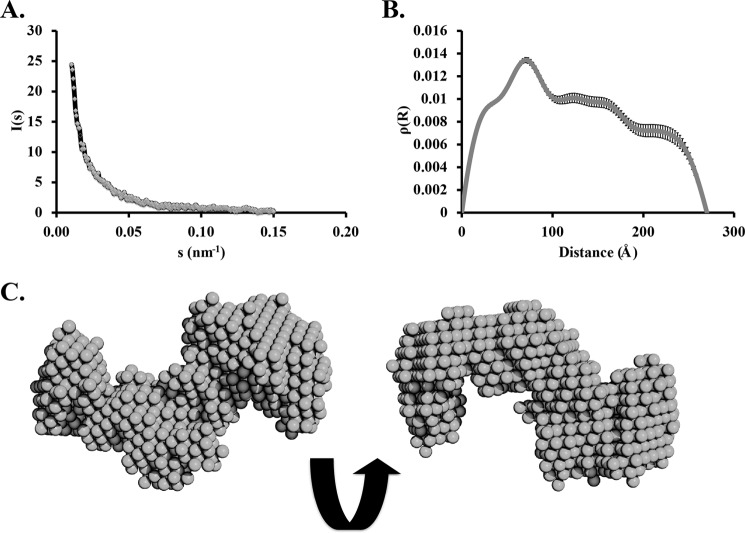

Given the discrepancy between the apparent molecular mass of H5 on a gel filtration column and by sedimentation equilibrium ultracentrifugation, we were interested in analyzing the structure of H5 by yet another independent biophysical measurement, SAXS (Fig. 7). The SAXS data indicated that the protein showed a tendency to aggregate. The apparent intrinsic disorder of the protein might have a role in the aggregation process. A low resolution three-dimensional reconstruction based on SAXS data showed an elongated rod-like structure that fitted four of the homology model monomers. Consistent with the sedimentation equilibrium data, the SAXS data suggests that H5 exists as a tetramer in solution. The radius of gyration determined from the data is also in agreement with the dimensions of a tetramer.

FIGURE 7.

Small-angle x-ray scattering analyses of H5. A, one-dimensional scattering data. B, pairwise distribution function. C, low resolution three-dimensional reconstruction of the model shows an elongated rod-like structure that can fit four translated and staggered H5model monomers.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we have characterized the biochemical and biophysical properties of the multi-functional vaccinia protein, H5. We have shown that H5 endoribonucleolytically cleaves the ssRNA cleavage substrate in vitro to yield a 3′-OH end. H5 binds both single-stranded and double-stranded nucleic acids, requiring at least 40 nt for efficient binding but prefers double-stranded nucleic acids over single-stranded as follows: dsDNA/dsRNA > DNA:RNA > ssDNA/ssRNA. The interaction of H5 with nucleic acid is sequence nonspecific and electrostatic: salt affects binding and pH has no effect on binding, suggesting binding to the phosphodiester backbone. The N terminus of H5 is intrinsically disordered but the C terminus has an α-helical structure. The purified E. coli-expressed H5 protein is a stable and homogenous tetramer (90 kDa) with an elongated rod-like structure. We suggest that the unusual rod-like shape of the tetrameric protein in conjunction with the intrinsic disorder of the N terminus of each monomer contributes to its large apparent molecular mass upon gel filtration. Gel filtration data consistent with apparent mass greater than actual mass are expected for intrinsically disordered proteins because of increased hydrodynamic volume relative to that of ordered proteins of the same mass (51). However, the molecular mass of purified vaccinia-expressed H5 appears to be more complex with a heterogenous mix of protein structures ranging from tetramers to octamers and even higher order structures. We predict that the dynamic phosphorylation pattern of vaccinia-expressed H5 plays a key role in this difference.

Viral proteins, in general, are very abundant in intrinsically disordered regions (52–55). Intrinsically disordered proteins have been identified in both DNA and RNA viruses with a larger number present in RNA viruses (52–55). However, unlike the intrinsically disordered proteins found in eukaryotes, viral intrinsically disordered proteins are characterized to have short, disordered segments. Because viral genomes are unusually compact with overlapping reading frames, a single mutation can affect more than one protein. Additionally, the viral lifestyle requires multiple interactions with proteins, membranes, DNA, and RNA of the host in conjunction with the ability to adapt to new/alternative hosts. Thus, the ability to interact with different and multiple partners accompanied with the high rate of evolution can be linked to disorder and conformational flexibility.

The cleavage of ssRNA by H5 to yield a 3′-OH is consistent with its role in post-replicative transcription termination. Although most RNases such as RNase A and RNase T1 cleave RNA to form a 3′-PO4, other specialized RNases, including β-lactamases (e.g. CPSF73, the cleavage factor of the eucaryotic cleavage and polyadenylation complex, and RNase Z, the tRNA maturation nuclease), RNase III (Dicer), and RNase H (cleaves DNA:RNA hybrids) produce a 3′-OH during cleavage (56–59). A 3′-OH in the cleavage reaction suggests that the nascent transcript can be a substrate for vaccinia poly(A) polymerase during vaccinia post-replicative transcription. Alternatively, the endoribonucleolytic function of H5 may be involved in viral DNA replication. H5 interacts with a vaccinia protein of unknown function, A49 (23). Blast analysis of the A49 protein sequence against the non-redundant database indicates the presence of a DnaI conserved motif in the C terminus of the protein. DnaI proteins are components of the Bacillus subtilis replication restart primosome (60). Another vaccinia protein required for viral DNA replication, D5, has been characterized as a primase, suggesting the formation of Okazaki fragments on the lagging strand during viral replication (61). Given the role of H5 as a viral endoribonuclease and the fact that H5 binds DNA:RNA hybrids with high affinity, it is possible that H5 has RNase H-like activity and cleaves the RNA primer in the lagging strand during DNA replication. However, preliminary experiments to characterize RNase H activity in H5 were negative (data not shown). Additionally, other nucleases such as the FEN-1-like endonuclease (vaccinia protein G5), the nicking and joining enzyme (K2), and the holiday junction resolvase (A22) are present in vaccinia and may be involved in this role for vaccinia DNA replication (62–64).

Independent evidence suggests that H5 exists as a multimeric protein. Wright et al. (27) observed self-interaction of H5 both by yeast two-hybrid analyses and by in vitro pulldown assays. DeMasi et al. (36) have shown that a temperature-sensitive mutant of H5 (tsH5–4) has a dominant negative phenotype: when both a WT and mutant copy of H5 are expressed on the same viral genome, the function of H5 in morphogenesis is affected, suggesting that WT and mutant H5 protein interact with each other affecting function. Additionally, Boyle and Traktman3 have shown that unfractionated extracts from another temperature-sensitive mutant of H5 (Dts57, affected in DNA replication) elutes with a smaller apparent molecular mass from gel filtration (150 versus 460 kDa for WT protein), suggesting the mutant protein has an altered ability to form multimers. Unlike tsH5–4, the phenotype for Dts57 is not dominant negative (the phenotype of this mutant was rescued using wild type H5). The mutation in tsH5–4 is in the N-terminal region of the protein (EEE to AAA at amino acid positions 73–75), and in Dts57, the C-terminal region of the protein is altered (G189R). Taken together, these observations suggest that the higher order structure of H5 is key to its function both in morphogenesis and DNA replication, and we suggest that this multimerization of H5 is possibly via its C-terminal domain.

Extrapolating from data in this study and previous studies, it is clear that H5 functions as a hub protein in vaccinia virus replication. Hub proteins are highly connected nodes that are capable of binding several partners and linking several independent biological functions (65). These partners can be both nucleic acid and protein. Several hub proteins, including the family of high mobility group proteins (HMGA), have been shown to bind bent or folded DNA in a sequence-nonspecific manner via the minor groove. Most hub proteins are known to have at least some degree of intrinsic disorder in their structure to achieve flexibility while interacting with several binding partners. Finally, post-translational modifications such as phosphorylation, acetylation, and methylation have been shown to add to this flexibility. H5 fits the criteria for all of the above characteristics of hub proteins: it is dynamically phosphorylated, has a highly disordered N-terminal region, can self-interact, and also bind several viral proteins (A20, B1, A2, G2, G8, A18, and A49) and nucleic acids (23, 26, 27, 66).

A recent literature search revealed another protein with surprisingly similar characteristics - coilin (67). Coilin is an intrinsically disordered, 576-amino acid, constitutively expressed protein that is a marker for Cajal bodies but is also present in high abundance in the nucleoplasm. Cajal bodies are sub-nuclear sites of RNA-related metabolic processes, including small nuclear ribonucleic protein biogenesis and maturation, histone mRNA processing, and telomere maintenance (68). Cajal bodies are assembled during interphase and disassembled during mitosis. Coilin is thought to function as a scaffold to seed Cajal body formation. This protein interacts with itself and with other proteins important for small nuclear ribonucleic protein biogenenesis. Coilin is dynamically phosphorylated: it is hyperphosphorylated during mitosis causing a decrease in self-interaction and association with its binding partners. This hyperphosphorylation is thought to cause disassembly of the Cajal bodies. Broome et al. (67) showed that purified coilin binds non-specifically to dsDNA and cleaves U2 pre-snRNA at a CU-rich site in vitro. Furthermore, depletion of coilin mRNA in vivo caused an increase in both U1 and U2 pre-snRNA, suggesting that coilin binds non-specifically to chromatin and is required for the maturation of U1 and U2 pre-snRNA in Cajal bodies. Similar to H5, coilin does not bear resemblance to any known ribonucleases. The disordered N terminus of coilin was found to be required for its nuclease activity. Superposing of the H5model with a coilinmodel did not reveal any common structural features.

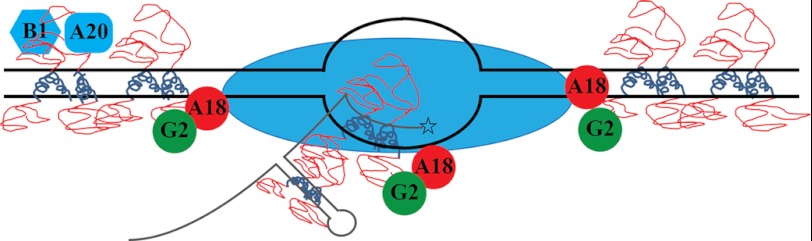

We have constructed a model that posits H5 as a hub via which several viral functions can be linked (Fig. 8). This model makes several predictions. 1) The minimal structure of H5 is tetrameric and shaped like an elongated rod. 2) The intrinsically disordered N terminus is free and interacts with several protein partners, including A20, B1, G2, and A18 causing an induced-fit conformation change. 3) The α-helical C-terminal domain of each monomer is required for interaction of the protein with itself and for interaction with the sugar-phosphate backbone of nucleic acid. 4) The dynamic phosphorylation status of H5 changes the structure of H5 from tetrameric to higher order structures and also determines the affinity of H5 to its binding partners.

FIGURE 8.

Model of H5 function in vaccinia virus replication. C termini of tetrameric H5 (blue coils) bind and coat dsDNA (black double lines with transcription bubble) or dsRNA (gray stem-loop nascent mRNA) or DNA:RNA hybrid. Disordered N termini of tetrameric H5 (red loops) recruit H5 binding partners to the site of DNA replication and transcription. Blue oval, RNA polymerase.

With these predictions in place, we propose that the tetrameric form of the protein requires at least 40 nt of nucleic acid to bind with high affinity. We also propose that H5 binds and coats double-stranded nucleic acids and recruits several viral replication partners, transcription factors, and viral proteins effecting morphogenesis, depending on its phosphorylation status. We propose that membrane formation and early stages of virion assembly, including crescent formation and virosome encapsidation, is facilitated by or occurs on an H5 matrix. The phosphorylation of H5 by F10 may play a critical role in this process. Finally, we believe the role of H5 in cleavage may be unusual. We propose that H5 recognizes structure rather than sequence of the late mRNA around the cleavage site and binds to the double-stranded region to cause cleavage mechanically by kinking the RNA or enzymatically via endoribonucleolytic cleavage. This would cause destabilization of the transcription ternary complex and allow for termination catalyzed by A18, the vaccinia termination factor. This hypothesis is predicated on the torpedo model of transcription termination in eukaryotes (69).

In conclusion, H5 is an intrinsically disordered, sequence-nonspecific double-stranded DNA (or RNA) binding, dynamically phosphorylated protein that has endoribonucleolytic activity in vitro and is capable of self-interaction as well as transient interaction with several other vaccinia viral proteins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Kathy Boyle and Dr. Paula Traktman for Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) harboring the plasmid pET14b-H5 and Dr. Paul Gollnick for helpful discussions and reviewing the manuscript.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant RO1 18094 (to R. C. C.).

This article contains supplemental Figs. 1 and 2.

K. Boyle and P. Traktman, personal communication.

- SAXS

- small-angle x-ray scattering

- TAP

- tobacco acid pyrophosphatase

- nt

- nucleotide

- ts

- temperature-sensitive

- pCp

- cytidine-3′,5′-bis-phosphate.

REFERENCES

- 1. Moss B. (2007) Poxviridae: the viruses and their replication in Fields Virology (Knipe D. M., Howley P. M., eds) pp. 2906–2945, Wolters, Kluwer-Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, Philadelphia [Google Scholar]

- 2. Condit R. C., Niles E. G. (2002) Regulation of viral transcription elongation and termination during vaccinia virus infection. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1577, 325–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Shuman S., Broyles S. S., Moss B. (1987) Purification and characterization of a transcription termination factor from vaccinia virions. J. Biol. Chem. 262, 12372–12380 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Christen L. M., Sanders M., Wiler C., Niles E. G. (1998) Vaccinia virus nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase I is an essential viral early gene transcription termination factor. Virology 245, 360–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mohamed M. R., Niles E. G. (2000) Interaction between nucleoside triphosphate phosphohydrolase I and the H4L subunit of the viral RNA polymerase is required for vaccinia virus early gene transcript release. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 25798–25804 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deng L., Shuman S. (1998) Vaccinia NPH-I, a DExH-box ATPase, is the energy coupling factor for mRNA transcription termination. Genes Dev. 12, 538–546 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shuman S., Moss B. (1988) Factor-dependent transcription termination by vaccinia virus RNA polymerase. Evidence that the cis-acting termination signal is in nascent RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 263, 6220–6225 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yuen L., Moss B. (1987) Oligonucleotide sequence signaling transcriptional termination of vaccinia virus early genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 6417–6421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rohrmann G., Yuen L., Moss B. (1986) Transcription of vaccinia virus early genes by enzymes isolated from vaccinia virions terminates downstream of a regulatory sequence. Cell 46, 1029–1035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mahr A., Roberts B. E. (1984) Arrangement of late RNAs transcribed from a 7.1-kilobase EcoRI vaccinia virus DNA fragment. J. Virol. 49, 510–520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Black E. P., Condit R. C. (1996) Phenotypic characterization of mutants in vaccinia virus gene G2R, a putative transcription elongation factor. J. Virol. 70, 47–54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lackner C. A., Condit R. C. (2000) Vaccinia virus gene A18R DNA helicase is a transcript release factor. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 1485–1494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Latner D. R., Xiang Y., Lewis J. I., Condit J., Condit R. C. (2000) The vaccinia virus bifunctional gene J3 (nucleoside-2′-O-)-methyltransferase and poly(A) polymerase stimulatory factor is implicated as a positive transcription elongation factor by two genetic approaches. Virology 269, 345–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Yang Z., Martens C. A., Bruno D. P., Porcella S. F., Moss B. (2012) Pervasive initiation and 3′-end formation of poxvirus postreplicative RNAs. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 31050–31060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Condit R. C., Moussatche N., Traktman P. (2006) In a nutshell: structure and assembly of the vaccinia virion. Adv. Virus Res. 66, 31–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Domi A., Beaud G. (2000) The punctate sites of accumulation of vaccinia virus early proteins are precursors of sites of viral DNA synthesis. J. Gen. Virol. 81, 1231–1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rosel J. L., Earl P. L., Weir J. P., Moss B. (1986) Conserved TAAATG sequence at the transcriptional and translational initiation sites of vaccinia virus late genes deduced by structural and functional analysis of the HindIII H genome fragment. J. Virol. 60, 436–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Beaud G., Beaud R., Leader D. P. (1995) Vaccinia virus gene H5R encodes a protein that is phosphorylated by the multisubstrate vaccinia virus B1R protein kinase. J. Virol. 69, 1819–1826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Gordon J., Mohandas A., Wilton S., Dales S. (1991) A prominent antigenic surface polypeptide involved in the biogenesis and function of the vaccinia virus envelope. Virology 181, 671–686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kovacs G. R., Moss B. (1996) The vaccinia virus H5R gene encodes late gene transcription factor 4: purification, cloning, and overexpression. J. Virol. 70, 6796–6802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Beaud G., Beaud R. (1997) Preferential virosomal location of underphosphorylated H5R protein synthesized in vaccinia virus-infected cells. J. Gen. Virol. 78 ( Pt 12), 3297–3302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. D'Costa S. M., Bainbridge T. W., Condit R. C. (2008) Purification and properties of the vaccinia virus mRNA processing factor. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 5267–5275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. McCraith S., Holtzman T., Moss B., Fields S. (2000) Genome-wide analysis of vaccinia virus protein-protein interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 4879–4884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ishii K., Moss B. (2001) Role of vaccinia virus A20R protein in DNA replication: construction and characterization of temperature-sensitive mutants. J. Virol. 75, 1656–1663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. D'Costa S. M., Bainbridge T. W., Kato S. E., Prins C., Kelley K., Condit R. C. (2010) Vaccinia H5 is a multifunctional protein involved in viral DNA replication, postreplicative gene transcription, and virion morphogenesis. Virology 401, 49–60 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Black E. P., Moussatche N., Condit R. C. (1998) Characterization of the interactions among vaccinia virus transcription factors G2R, A18R, and H5R. Virology 245, 313–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Dellis S., Strickland K. C., McCrary W. J., Patel A., Stocum E., Wright C. F. (2004) Protein interactions among the vaccinia virus late transcription factors. Virology 329, 328–336 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cresawn S. G., Condit R. C. (2007) A targeted approach to identification of vaccinia virus postreplicative transcription elongation factors: genetic evidence for a role of the H5R gene in vaccinia transcription. Virology 363, 333–341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Parsons B. L., Pickup D. J. (1990) Transcription of orthopoxvirus telomeres at late times during infection. Virology 175, 69–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Patel D. D., Ray C. A., Drucker R. P., Pickup D. J. (1988) A poxvirus-derived vector that directs high levels of expression of cloned genes in mammalian cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85, 9431–9435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Patel D. D., Pickup D. J. (1989) The second-largest subunit of the poxvirus RNA polymerase is similar to the corresponding subunits of procaryotic and eucaryotic RNA polymerases. J. Virol. 63, 1076–1086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Antczak J. B., Patel D. D., Ray C. A., Ink B. S., Pickup D. J. (1992) Site-specific RNA cleavage generates the 3′ end of a poxvirus late mRNA. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 12033–12037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. D'Costa S. M., Antczak J. B., Pickup D. J., Condit R. C. (2004) Post-transcription cleavage generates the 3′ end of F17R transcripts in vaccinia virus. Virology 319, 1–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Nowakowski M., Bauer W., Kates J. (1978) Characterization of a DNA-binding phosphoprotein from vaccinia virus replication complex. Virology 86, 217–225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Mohandas A. R., Dekaban G. A., Dales S. (1994) Vaccinia virion surface polypeptide Ag35 expressed from a baculovirus vector is targeted to analogous poxvirus and insect virus components. Virology 200, 207–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. DeMasi J., Traktman P. (2000) Clustered charge-to-alanine mutagenesis of the vaccinia virus H5 gene: isolation of a dominant, temperature-sensitive mutant with a profound defect in morphogenesis. J. Virol. 74, 2393–2405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Condit R. C., Motyczka A. (1981) Isolation and preliminary characterization of temperature-sensitive mutants of vaccinia virus. Virology 113, 224–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Condit R. C., Motyczka A., Spizz G. (1983) Isolation, characterization, and physical mapping of temperature-sensitive mutants of vaccinia virus. Virology 128, 429–443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Condit R. C., Lewis J. I., Quinn M., Christen L. M., Niles E. G. (1996) Use of lysolecithin-permeabilized infected-cell extracts to investigate the in vitro biochemical phenotypes of poxvirus ts mutations altered in viral transcription activity. Virology 218, 169–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Fuerst T. R., Niles E. G., Studier F. W., Moss B. (1986) Eukaryotic transient-expression system based on recombinant vaccinia virus that synthesizes bacteriophage T7 RNA polymerase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 83, 8122–8126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bayliss C. D., Condit R. C. (1995) The vaccinia virus A18R gene product is a DNA-dependent ATPase. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 1550–1556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wong I., Lohman T. M. (1993) A double-filter method for nitrocellulose-filter binding: application to protein-nucleic acid interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 90, 5428–5432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Xue B., Dunbrack R. L., Williams R. W., Dunker A. K., Uversky V. N. (2010) PONDR-FIT: a meta-predictor of intrinsically disordered amino acids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1804, 996–1010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kim D. E., Chivian D., Baker D. (2004) Protein structure prediction and analysis using the Robetta server. Nucleic Acids Res. 32, W526-W531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Greenfield N., Fasman G. D. (1969) Computed circular dichroism spectra for the evaluation of protein conformation. Biochemistry 8, 4108–4116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Nielsen S. S., Toft K. N., Snakenborg D., Jeppesen M. G., Jacobsen J. K., Vestergaard B., Kutter J. P., Arleth L. (2009) BioXTAS RAW, a software program for high-throughput automated small-angle x-ray scattering data reduction and preliminary analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 42, 959–964 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Petoukhov M. V., Konarev P. V., Kikhney A. G., Svergun D. I. (2007) ATSAS 2.1 - towards automated and web-supported small-angle scattering data analysis. J. Appl. Cryst. 40, S223–228 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Pettersen E. F., Goddard T. D., Huang C. C., Couch G. S., Greenblatt D. M., Meng E. C., Ferrin T. E. (2004) UCSF chimera - A visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J. Comput. Chem. 25, 1605–1612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bubb M. R., Spector I., Bershadsky A. D., Korn E. D. (1995) Swinholide A is a microfilament disrupting marine toxin that stabilizes actin dimers and severs actin filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 3463–3466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bubb M. R., Lewis M. S., Korn E. D. (1991) The interaction of monomeric actin with two binding sites on Acanthamoeba actobindin. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 3820–3826 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Uversky V. N. (2010) Targeting intrinsically disordered proteins in neurodegenerative and protein dysfunction diseases: another illustration of the D(2) concept. Expert. Rev. Proteomics. 7, 543–564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tokuriki N., Oldfield C. J., Uversky V. N., Berezovsky I. N., Tawfik D. S. (2009) Do viral proteins possess unique biophysical features? Trends Biochem. Sci. 34, 53–59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Xue B., Dunker A. K., Uversky V. N. (2012) Orderly order in protein intrinsic disorder distribution: disorder in 3500 proteomes from viruses and the three domains of life. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 30, 137–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Xue B., Mizianty M. J., Kurgan L., Uversky V. N. (2012) Protein intrinsic disorder as a flexible armor and a weapon of HIV-1. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 69, 1211–1259 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xue B., Williams R. W., Oldfield C. J., Goh G. K., Dunker A. K., Uversky V. N. (2010) Viral disorder or disordered viruses: do viral proteins possess unique features?. Protein Pept. Lett. 17, 932–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. MacRae I. J., Doudna J. A. (2007) Ribonuclease revisited: structural insights into ribonuclease III family enzymes. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 17, 138–145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wintersberger U. (1990) Ribonucleases H of retroviral and cellular origin. Pharmacol. Ther. 48, 259–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Mayer M., Schiffer S., Marchfelder A. (2000) tRNA 3′ processing in plants: nuclear and mitochondrial activities differ. Biochemistry 39, 2096–2105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wickens M., Gonzalez T. N. (2004) Knives, Accomplices, and RNA. Science 306, 1299–1300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Bruand C., Farache M., McGovern S., Ehrlich S. D., Polard P. (2001) DnaB, DnaD and DnaI proteins are components of the Bacillus subtilis replication restart primosome. Mol. Microbiol. 42, 245–255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. De Silva F. S., Lewis W., Berglund P., Koonin E. V., Moss B. (2007) Poxvirus DNA primase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 18724–18729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Da Silva M., Shen L., Tcherepanov V., Watson C., Upton C. (2006) Predicted function of the vaccinia virus G5R protein. Bioinformatics 22, 2846–2850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Garcia A. D., Moss B. (2001) Repression of vaccinia virus Holliday junction resolvase inhibits processing of viral DNA into unit-length genomes. J. Virol. 75, 6460–6471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Eckert D., Williams O., Meseda C. A., Merchlinsky M. (2005) Vaccinia virus nicking-joining enzyme is encoded by K4L (VACWR035) J. Virol. 79, 15084–15090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Dunker A. K., Cortese M. S., Romero P., Iakoucheva L. M., Uversky V. N. (2005) Flexible nets. The roles of intrinsic disorder in protein interaction networks. FEBS J. 272, 5129–5148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Ishii K., Moss B. (2002) Mapping interaction sites of the A20R protein component of the vaccinia virus DNA replication complex. Virology 303, 232–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Broome H. J., Hebert M. D. (2012) In vitro RNase and nucleic acid binding activities implicate coilin in U snRNA processing. PLoS One 7, e36300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Morris G. E. (2008) The Cajal body. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1783, 2108–2115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Luo W., Bentley D. (2004) A ribonucleolytic rat torpedoes RNA polymerase II. Cell 119, 911–914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.