Abstract

Evidence accumulating in 2011–2012 indicates that there is significant intra- and inter-species transmission of influenza A viruses at agricultural fairs, which has renewed interest in this unique human/swine interface. Six human cases of influenza A (H3N2) variant (H3N2v) virus infections were epidemiologically linked to swine exposure at fairs in the United States in 2011. In 2012, the number of H3N2v cases in the Midwest had exceeded 300 from early July to September, 2012. Prospective influenza A virus surveillance among pigs at Ohio fairs resulted in the detection of H3N2pM (H3N2 influenza A viruses containing the matrix (M) gene from the influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 virus). These H3N2pM viruses were temporally and spatially linked to several human H3N2v cases. Complete genomic analyses of these H3N2pM isolates demonstrated >99% nucleotide similarity to the H3N2v isolates recovered from human cases. Actions to mitigate the bidirectional interspecies transmission of influenza A virus between people and animals at agricultural fairs may be warranted.

Keywords: human H3N2v, H3N2pM, influenza, fair, swine

Introduction

The commingling of pigs and people at agricultural fairs represents a potentially important and inadequately evaluated interface in the evolution and transmission of zoonotic influenza A viruses. This interface may be a critical point for the movement of influenza A viruses and/or genes between human and swine populations.1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12 Interspecies transmission of influenza A viruses has been sporadically confirmed at agricultural fairs.7,13,14,15 Recent cases of influenza A (H3N2) variant virus (H3N2v) infection in humans have been epidemiologically associated with exposures to swine at agricultural fairs in North America.16,17 Since 2009, we have conducted a prospective influenza A virus surveillance study among pigs exhibited at county fairs in Ohio. In July 2012, as part of routine sampling, H3N2pM viruses (H3N2 influenza A viruses containing the matrix (M) gene from the influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 virus) were recovered from pigs at a county fair associated with concurrent cases of human H3N2v infections among its participants.17 Here we report that next generation sequencing of the complete H3N2pM virus genomes, isolated from pigs at the fair, exhibited >99% similarity at the nucleotide level to H3N2v isolates concurrently recovered from the human cases.

Materials and methods

As part of our ongoing surveillance project, nasal swabs were collected from 34 randomly selected pigs (out of a total of 348 pigs) exhibited at an Ohio county fair on the last day of the fair, 28 July 2012, approximately 7 days after the pigs arrived at the fair. Visual examination of all pigs in the barns immediately prior to sample collection did not reveal any pigs with overt clinical signs consistent with influenza-like illness (ILI) although swine exhibitors reported pigs at the fair had a variety of maladies (diarrhea, vomiting and fever) 3–5 days prior to the sampling day, which resulted in the early dismissal of a few pigs from the fair. Swabs were placed singly into vials containing viral transport media18 and stored at −80 °C until they were tested. Real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (RRT-PCR) was used to screen the original samples for the presence of influenza A virus,19,20 to determine hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase subtypes, and to characterize the M gene lineage.21 Viral transport media supernatant was also inoculated onto Madin–Darby canine kidney cells for virus isolation.22 Representative influenza A virus isolates were sent to the United States Department of Agriculture National Veterinary Services Laboratories for confirmational testing and complete genome sequencing using integrated semiconductor sequencing (Ion Torrent).23

All eight segments of two isolates were amplified using gene-specific and universal primers for each segment. The cDNA was purified and cDNA libraries were prepared for the Ion Torrent using the IonXpress Plus Fragment Library Kit (Life Technologies Corp., Grand Island, NY, USA) with Ion Xpress barcode adapters (Life Technologies Corp.). Prepared libraries were quantitated by qPCR using the Ion Library Quantitation Kit (Life Technologies Corp.). Quantitated libraries were diluted and pooled for library amplification using the Ion One Touch and ES systems (Life Technologies Corp.). Following enrichment, DNA was loaded onto an Ion 314 chip (Life Technologies Corp.) and sequenced using the Ion PGM 200 Sequencing Kit (Life Technologies Corp.).

Sequences were assembled using Lasergene DNAStar SeqMan NGen 4.0 software (DNASTAR, Inc., Madison, WI, USA). Reference based assemblies were performed using H3N2pM reference sequences generated at National Veterinary Services Laboratories (full open reading frames). Single nucleotide polymorphisms and short insertions and deletions were evaluated as potential errors. The number of bases used for reference-based assembly was equal to the open reading frame length, i.e. 2280 bp for the PB2 gene, 1701 bp for the HA gene, etc. The output of the assemblies generated a full-length contiguous sequence for each gene segment spanning the complete open reading frame. Full-length sequences from the two swine-origin influenza A virus isolates reported here, A/swine/Ohio/12TOSU268/2012(H3N2) and A/swine/Ohio/12TOSU293/2012(H3N2), have been deposited in GenBank (accession numbers JX534958–JX534973).

On 27 July 2012, the Ohio Department of Health was notified by a county health department of two individuals who presented with ILI to local medical facilities and had significant direct swine contact over a number of days at their local county fair. Specimens were submitted for preliminary testing to the Ohio Department of Health laboratory and then forwarded to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for final confirmation. Genetic sequence results confirmed H3N2v infection in both patients. Over the next 3 weeks, an additional 20 cases of human illness associated with this county fair were confirmed to be caused by H3N2v. Most of the cases had direct exposure to swine. Sequences from the influenza A virus isolates recovered from the swine were compared to the human-origin influenza A H3N2v virus sequences (partial and full length) of A/Ohio/13/2012(H3N2), A/Ohio/14/2012(H3N2), A/Ohio/15/2012(H3N2), A/Ohio/16/2012(H3N2) and/or A/Ohio/20/2012(H3N2) recovered from people with ILI following exposure to swine at the fair (Global Initiative on Sharing All Influenza Data and the Influenza Research Database).

All segments were analyzed separately, and their evolutionary history was inferred using the Maximum Parsimony or Maximum Likelihood methods. A bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 500 replicates is taken to represent the evolutionary history of the taxa analyzed.24 Branches corresponding to partitions reproduced in less than 50% bootstrap replicates are collapsed. The matrix protein tree was obtained using the Close-Neighbor-Interchange algorithm25 with search level 1 in which the initial trees were obtained with the random addition of sequences (10 replicates). The trees are drawn to scale, with branch lengths calculated using the average pathway method25 and are in the units of the number of changes over the whole sequence. Evolutionary analyses were conducted in Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis software version 5.0.26

Results

Influenza A (H3N2) viruses containing the M gene from the influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 virus (H3N2pM) were detected in 31 of the 34 swine nasal swabs using RRT-PCR and H3N2pM viral isolates were recovered from 29 of the 31 RRT-PCR-positive samples. Analysis of the HA gene placed the concurrently recovered H3N2v and H3N2pM isolates tightly within the contemporary Cluster IV H3 viruses circulating in the US swine herd (Figure 1). The clustering of all HA genes of the human- and swine-origin viruses from this fair suggests common source dissemination. Furthermore, the phylogenetic structure of the HA gene suggests that H3 from the new variant viruses are evolving away from the classical Cluster IV H3. Neuraminidase (Figure 2), the polymerase complex (Figure 3), nucleoprotein (Figure 4) and non-structural (Figure 5) genes all show a similar trend with near 99% nucleotide similarity between the swine-origin H3N2pM and human-origin H3N2v viruses (Table 1). The M genes of both the H3N2pM and the analyzed H3N2v influenza A viruses clustered into a single clade with H1N1pdm segments from 2009 and 2012 and were separated from M genes from older, as well as more recent classical H3N2 viruses (Figure 6). For some segments, isolates from pigs and people from Illinois (2011) and Nebraska clustered with the H3N2v genes.

Figure 1.

Phylogeny of HA gene segment from swine lineages of H3N2 viruses. The percentage of replicate trees in which the associated HA gene segments clustered together in the bootstrap test using the Maximum Parsimony method are shown next to the branches.24 The analysis involved 45 nucleotide sequences and there were a total of 863 positions in the final dataset. The cluster-based classification is derived from previously established nomenclature.34,35 The four major clusters of H3 that have been circulating in the swine populations are shown. All H3N2v/H3N2pM HA segments (identified by a dot alongside the isolate) clustered together as a sublineage of previously described Cluster IV viruses.

Figure 2.

Maximum Parsimony analysis of NA gene from classical swine H3N2 and H3N2pM/H3N2v viruses. The NA genes of all the isolates (identified by a dot alongside the isolates) clustered together in a single lineage suggesting a clonal pattern. NA, neuraminidase.

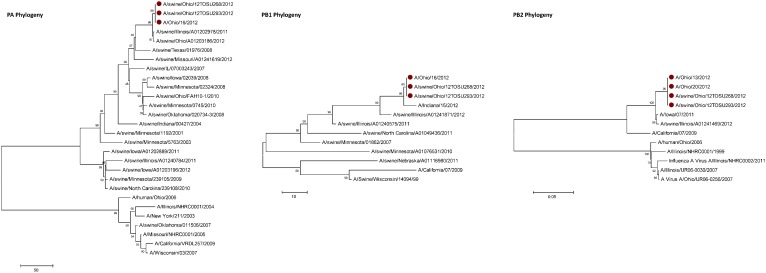

Figure 3.

Phylogenies of the polymerase complex (PA, PB1, PB2) genes. All sequences of the respective genes from the H3N2v/H3N2pM viruses clustered together. PA, polymerase A; PB1, polymerase B1; PB2, polymerase B2.

Figure 4.

Molecular phylogenetic analysis for NP gene. Shown is the evolutionary history of NP segment from swine-origin H3N2pM and human-origin H3N2v isolates inferred by using the Maximum Likelihood method based on the Hasegawa–Kishino–Yano model.25 All NP sequences from the H3N2pM/H3N2v (Ohio and other geographical locations) share high levels of identity. Initial tree(s) for the heuristic search were obtained automatically as follows. When the number of common sites was <100 or less than one-fourth of the total number of sites, the maximum parsimony method was used; otherwise BIONJ method with MCL distance matrix was used. A discrete Gamma distribution was used to model evolutionary rate differences among sites (five categories (+G, parameter=0.3714)). The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of substitutions per site. The analysis involved 22 nucleotide sequences. There were a total of 1497 positions in the final dataset. BIONJ, BIO neighbor joining; MCL, Markov cluster; NP, nucleocapsid protein.

Figure 5.

Phylogenetic analysis of the NS gene. The bootstrap consensus tree inferred using the Maximum Parsimony method is taken to represent the evolutionary history of the NS segments analyzed.25 The analysis involved 16 nucleotide sequences with a total of 838 positions in the final dataset. All NS genes of H3N2v/H3N2pM influenza A viruses clustered in a single clade suggesting clonality. NS, non-structural protein.

Table 1. Variations in nucleotide sequences of cDNA from human-origin H3N2v and swine-origin H3N2pM influenza A viruses.

| Gene segment (nucleotide position) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Strain name | NP | NA | NA | M | M | NS |

| (666) | (222) | (1410) | (221) | (366) | (414) | |

| A/Ohio/14/2012(H3N2) | G | G | A | C | C | T |

| A/Ohio/16/2012(H3N2) | G | G | A | C | T | C |

| A/swine/Ohio/12TOSU268/2012(H3N2) | G | G | A | Y | T | T |

| A/swine/Ohio/12TOSU293/2012(H3N2) | A | A | R | Y | T | T |

Abbreviations: M, matrix; NA, neuraminidase; NP, nucleocapsid protein; NS, non-structural protein.

Figure 6.

Phylogenetic analysis of gene coding for the MP from the (H1N1) pdm09, H3N2v/H3N2pM, North American swine-origin H3N2 and human-origin seasonal H3N2 influenza A viruses. Shown is a bootstrap consensus tree inferred using the Maximum Parsimony method. The analysis involved 22 nucleotide sequences of matrix genes from human, swine and recent pandemic influenza A viruses. All positions containing gaps and missing data were eliminated. There were a total of 978 positions in the final dataset. Matrix of all H3N2v/H3N2pM isolates clustered with the pandemic H1N1 segment sequence (boxed sequences in the tree). There is an indication of minor microscale evolution away from influenza A (H1N1) pdm09 virus within this segment with specific polymorphisms that favor human infection being maintained. MP, matrix protein.

Discussion

This study presents clear molecular evidence that pigs and humans were concurrently infected with the same strain of influenza A virus at an Ohio county fair in July 2012. The most recent ancestors of all the genetic segments of the H3N2v/H3N2pM viruses can be found in various triple reassortant H3N2, H1N2 and H1N1 influenza A viruses which have been detected in pigs in North America. The cocirculation of the genetic elements found in the H3N2v/H3N2pM viruses makes reassortment events occurring in swine the most likely path of emergence. Although similar influenza A H3N2pM viruses have been previously reported in pigs and in commercial swine herds,27 they had not been reported in exhibition pigs temporally and spatially linked to human cases of H3N2v until July 2012. Twelve pigs at the LaPorte County Fair in Northwestern Indiana tested positive for H3N2pM in early July 2012,28 but to date, there has been no documented comparison of genomic sequences of the viruses recovered from people and pigs. The temporal and spatial proximity of the human cases and swine reported here, the frequency of virus isolation from the pigs, and the >99% sequence identity of the swine- and human-origin viruses originating from this fair clearly demonstrates inter- and intra-species transmission of H3N2pM/H3N2v viruses (Figures 1–6). However, the route by which the virus was introduced into the swine and human populations at the fair has not been resolved.

Pigs are unique in their ability to serve as hosts of avian-, swine- and human-origin influenza A viruses and thus have been identified as a source of novel reassortant strains with zoonotic potential.29,30 The remarkable nucleotide sequence similarity between the swine-origin and human-origin H3N2 viruses reported here provides evidence that there are few or no adaptive genetic changes needed for the virus to replicate in either host. None of the nucleotide differences between the H3N2pM and H3N2v isolates resulted in a change in the predicted amino acid sequence, although the ambiguous base call at position 221 in the M genes of the H3N2pM isolates makes it unable to predict the resulting amino acid in that position (Table 1). Historically, as an influenza A virus emerges in a new host, there is commonly a series of genotypic changes that occur as the virus adapts to grow and transmit more efficiently in the new host. The lack of difference between the genotypes of these isolates suggests that there are virtually no innate species barriers preventing bidirectional interspecies transmission of H3N2pM/H3N2v viruses between humans and pigs. Furthermore, this close phylogenetic relationship between the swine and human viruses is consistent with a recent interspecies transmission. Fortunately, the symptoms exhibited among most human cases of H3N2v in 2012 have been relatively mild and sustained human-to-human transmission of these viruses has not been observed. However, with the growing number of documented human cases during recent months, the continuing evolution H3N2v is a concern.

Agricultural fairs are unique settings where pigs and people from multiple sources and immunological status are concentrated at one location, creating an interface where new or existing influenza A viruses and/or genes can move within or between human and swine populations. The repeated swine–swine and human–swine interactions occurring at agricultural fairs are distinctly different from those occurring in commercial swine production settings. These unique interactions undoubtedly facilitate bidirectional zoonotic transmission of influenza A viruses at fairs. This statement is supported by the increasing number of human H3N2v cases in the United States in late summer 201216,17,28,31,32,33 and previously documented influenza A virus transmission from humans-to-swine and swine-to-humans at agricultural fairs.7,9,13,15 Appropriate steps to prevent and/or reduce intra- and inter-species transmission of influenza A viruses at fairs should be undertaken to protect animal and human health while considering short- and long-term implications for the cultural value of livestock exhibitions. Potential strategies to mitigate the transmission of influenza A viruses between pigs and people are available from several sources including The Ohio State University's Animal Influenza Ecology and Epidemiology Research Program website (http://vet.osu.edu/preventive-medicine/AIEERP), Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and United States Department of Agriculture information publications.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the assistance of Mary DiOrio, Brian Fowler, Kathy Smith (Ohio Department of Health, USA), Tony Forshey (Ohio Department of Agriculture, USA) and Sabrina Swenson (United States Department of Agriculture, USA) for support during the investigation. This work has been funded by the Minnesota Center of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance with federal funds from the Centers of Excellence for Influenza Research and Surveillance, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services, under contract NO. HHSN266200700007C and the USDA/APHIS NVSL. Any mention of trade names or commercial products is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the US Department of Agriculture.

References

- Beaudoin A, Gramer M, Gray GC, Capuano A, Setterquist S, Bender J. Serologic survey of swine workers for exposure to H2N3 swine influenza A. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2010;4:163–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2009.00127.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray GC, McCarthy T, Capuano AW, Setterquist SF, Olsen CW, Alavanja MC. Swine workers and swine influenza virus infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13:1871–1878. doi: 10.3201/eid1312.061323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easterday BC. The epidemiology and ecology of swine influenza as a zoonotic disease. Comp Immunol Microbiol Infect Dis. 1980;3:105–109. doi: 10.1016/0147-9571(80)90045-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers KP, Olsen CW, Setterquist SF, et al. Are swine workers in the United States at increased risk of infection with zoonotic influenza virus. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:14–20. doi: 10.1086/498977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wentworth DE, McGregor MW, Macklin MD, Neumann V, Hinshaw VS. Transmission of swine influenza virus to humans after exposure to experimentally infected pigs. J Infect Dis. 1997;175:7–15. doi: 10.1093/infdis/175.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen CW, Carey S, Hinshaw L, Karasin AI. Virologic and serologic surveillance for human, swine and avian influenza virus infections among pigs in the north-central United States. Arch Virol. 2000;145:1399–1419. doi: 10.1007/s007050070098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray GC, Bender JB, Bridges CB, et al. Influenza A(H1N1)pdm09 Virus among Healthy Show Pigs, United States. Emerg Infects Dis. 2012;18:3. doi: 10.3201/eid1809.120431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander DJ. Ecological aspects of influenza A viruses in animals and their relationship to human influenza: a review. J R Soc Med. 1982;75:799–811. doi: 10.1177/014107688207501010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman L, Wells D, Schonberger L, Davis JP, Idtse F, Hinshaw V. Swine influenza surveillance, Wisconsin agricultural fairs, 1989 and 1990. JAMA. 1992;267:2741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JP, Leibler JH, Price LB, et al. The animal-human interface and infectious disease in industrial food animal production: rethinking biosecurity and biocontainment. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:282–299. doi: 10.1177/003335490812300309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson M, Gramer M, Vincent A, Holmes EC. Global transmission of influenza viruses from humans to swine. Journal Gen Virol. 2012;93 (Pt10:2195–2203. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.044974-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forgie SE, Keenliside J, Wilkinson C, et al. Swine outbreak of pandemic influenza A virus on a Canadian research farm supports human-to-swine transmission. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:10–18. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells DL, Hopfensperger DJ, Arden NH, et al. Swine influenza virus infections. Transmission from ill pigs to humans at a Wisconsin agricultural fair and subsequent probable person-to-person transmission. JAMA. 1991;265:478–481. doi: 10.1001/jama.265.4.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincent AL, Swenson SL, Lager KM, Gauger PC, Loiacono C, Zhang Y. Characterization of an influenza A virus isolated from pigs during an outbreak of respiratory disease in swine and people during a county fair in the United States. Vet Microbiol. 2009;137:51–59. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Killian ML, Swenson SL, Vincent AL, et al. Simultaneous infection of pigs and people with triple-reassortant swine influenza virus H1N1 at a US county fair Zoonoses Public Health9 July 2012; DOI: 10.1111/j.1863-2378.2012.01508.x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Schnirring L.Three states report new cases of variant H3N2. Minneapolis; CIDRAP; 2012. Available at http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/cidrap/content/influenza/swineflu/news/aug1612variant.html (accessed 22 August 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Anonymous More H3N2v cases reported, still linked to pig exposure. Atlanta; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2012. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/flu/spotlights/more-h3n2v-cases-reported.htm (accessed 22 August 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Slemons RD, Johnson DC, Osborn JS, Hayes F. Type-A influenza viruses isolated from wild free-flying ducks in California. Avian Dis. 1974;18:119–124. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spackman E, Senne DA, Myers TJ, et al. Development of a real-time reverse transcriptase PCR assay for type A influenza virus and the avian H5 and H7 hemagglutinin subtypes. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:3256–3260. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.9.3256-3260.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slomka MJ, Densham AL, Coward VJ, et al. Real time reverse transcription (RRT)-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods for detection of pandemic (H1N1) 2009 influenza virus and European swine influenza A virus infections in pigs. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2010;4:277–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2010.00149.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon K, Bower L, Kim WI, Pentella M, Yoon KJ. A matrix gene-based multiplex real-time RT-PCR for detection and differentiation of 2009 pandemic H1N1 and other influenza A viruses in North America. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2010;4:405–410. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2010.00153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swenson SL.Swine influenza Manual of diagnostic tests and vaccines for terrestrial animals. Paris; World Organization for Animal Health (OIE)2010. Available at http://www.oie.int/manual-of-diagnostic-tests-and-vaccines-for-terrestrial-animals/ (accessed 11 April 2011). [Google Scholar]

- Rothberg JM, Hinz W, Rearick TM, et al. An integrated semiconductor device enabling non-optical genome sequencing. Nature. 2011;475:348–352. doi: 10.1038/nature10242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tajima F. Simple methods for testing the molecular evolutionary clock hypothesis. Genetics. 1993;135:599–607. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.2.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa M, Kishino H, Yano T. Dating of the human-ape splitting by a molecular clock of mitochondrial DNA. J Mol Evol. 1985;22:160–174. doi: 10.1007/BF02101694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2731–2739. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson MI, Vincent AL, Kitikoon P, Holmes EC, Gramer MR. Evolution of novel reassortant A/H3N2 influenza viruses in North American swine and humans, 2009–2011. J Virol. 2012;86:8872–8878. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00259-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roos R.H3N2 found in most pigs tested following human cases. Minneapolis; CIDRAP; 2012. Available at http://www.cidrap.umn.edu/cidrap/content/influenza/swineflu/news/aug0712swine.html (accessed 23 August 2012) [Google Scholar]

- Ito T, Couceiro JN, Kelm S, et al. Molecular basis for the generation in pigs of influenza A viruses with pandemic potential. J Virol. 1998;72:7367–7373. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7367-7373.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma W, Lager K, Lekcharoensuk P, et al. Viral reassortment and transmission after co-infection of pigs with classical H1N1 and triple-reassortant H3N2 swine influenza viruses. J Gen Virol. 2010;91 Pt 9:2314–2321. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.021402-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention CDC confirms the 6th and 7th cases of swine-origin influenza A H3N2 virus with 2009 H1N1 M gene. ‘Have you heard?' Atlanta; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2011. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/media/haveyouheard/stories/h3n2_virus2.html (accessed 10 December 2011). [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Swine-origin influenza A (H3N2) virus infection in two children—Indiana and Pennsylvania, July-August 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:1213–1215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Update: Influenza A (H3N2)v transmission and guidelines - five states, 2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;60:1741–1744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webby RJ, Swenson SL, Krauss SL, Gerrish PJ, Goyal SM, Webster RG. Evolution of swine H3N2 influenza viruses in the United States. Journal Virol. 2000;74:8243–8251. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8243-8251.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen CW, Karasin AI, Carman S, et al. Triple reassortant H3N2 influenza A viruses, Canada, 2005. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12:1132–1135. doi: 10.3201/eid1207.060268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]