Abstract

Long working hours and sleep deprivation have been a facet of physician training in the US since the advent of the modern residency system. However, the scientific evidence linking fatigue with deficits in human performance, accidents and errors in industries from aeronautics to medicine, nuclear power, and transportation has mounted over the last 40 years. This evidence has also spawned regulations to help ensure public safety across safety-sensitive industries, with the notable exception of medicine.

In late 2007, at the behest of the US Congress, the Institute of Medicine embarked on a year-long examination of the scientific evidence linking resident physician sleep deprivation with clinical performance deficits and medical errors. The Institute of Medicine’s report, entitled “Resident duty hours: Enhancing sleep, supervision and safety”, published in January 2009, recommended new limits on resident physician work hours and workload, increased supervision, a heightened focus on resident physician safety, training in structured handovers and quality improvement, more rigorous external oversight of work hours and other aspects of residency training, and the identification of expanded funding sources necessary to implement the recommended reforms successfully and protect the public and resident physicians themselves from preventable harm.

Given that resident physicians comprise almost a quarter of all physicians who work in hospitals, and that taxpayers, through Medicare and Medicaid, fund graduate medical education, the public has a deep investment in physician training. Patients expect to receive safe, high-quality care in the nation’s teaching hospitals. Because it is their safety that is at issue, their voices should be central in policy decisions affecting patient safety. It is likewise important to integrate the perspectives of resident physicians, policy makers, and other constituencies in designing new policies. However, since its release, discussion of the Institute of Medicine report has been largely confined to the medical education community, led by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME).

To begin gathering these perspectives and developing a plan to implement safer work hours for resident physicians, a conference entitled “Enhancing sleep, supervision and safety: What will it take to implement the Institute of Medicine recommendations?” was held at Harvard Medical School on June 17–18, 2010. This White Paper is a product of a diverse group of 26 representative stakeholders bringing relevant new information and innovative practices to bear on a critical patient safety problem. Given that our conference included experts from across disciplines with diverse perspectives and interests, not every recommendation was endorsed by each invited conference participant. However, every recommendation made here was endorsed by the majority of the group, and many were endorsed unanimously. Conference members participated in the process, reviewed the final product, and provided input before publication. Participants provided their individual perspectives, which do not necessarily represent the formal views of any organization.

In September 2010 the ACGME issued new rules to go into effect on July 1, 2011. Unfortunately, they stop considerably short of the Institute of Medicine’s recommendations and those endorsed by this conference. In particular, the ACGME only applied the limitation of 16 hours to first-year resident physicans. Thus, it is clear that policymakers, hospital administrators, and residency program directors who wish to implement safer health care systems must go far beyond what the ACGME will require. We hope this White Paper will serve as a guide and provide encouragement for that effort.

Resident physician workload and supervision

By the end of training, a resident physician should be able to practice independently. Yet much of resident physicians’ time is dominated by tasks with little educational value. The caseload can be so great that inadequate reflective time is left for learning based on clinical experiences. In addition, supervision is often vaguely defined and discontinuous. Medical malpractice data indicate that resident physicians are frequently named in lawsuits, most often for lack of supervision. The recommendations are:

The ACGME should adjust resident physicians workload requirements to optimize educational value. Resident physicians as well as faculty should be involved in work redesign that eliminates nonessential and noneducational activity from resident physician duties

Mechanisms should be developed for identifying in real time when a resident physician’s workload is excessive, and processes developed to activate additional providers

Teamwork should be actively encouraged in delivery of patient care. Historically, much of medical training has focused on individual knowledge, skills, and responsibility. As health care delivery has become more complex, it will be essential to train resident and attending physicians in effective teamwork that emphasizes collective responsibility for patient care and recognizes the signs, both individual and systemic, of a schedule and working conditions that are too demanding to be safe

Hospitals should embrace the opportunities that resident physician training redesign offers. Hospitals should recognize and act on the potential benefits of work redesign, eg, increased efficiency, reduced costs, improved quality of care, and resident physician and attending job satisfaction

Attending physicians should supervise all hospital admissions. Resident physicians should directly discuss all admissions with attending physicians. Attending physicians should be both cognizant of and have input into the care patients are to receive upon admission to the hospital

Inhouse supervision should be required for all critical care services, including emergency rooms, intensive care units, and trauma services. Resident physicians should not be left unsupervised to care for critically ill patients. In settings in which the acuity is high, physicians who have completed residency should provide direct supervision for resident physicians. Supervising physicians should always be physically in the hospital for supervision of resident physicians who care for critically ill patients

The ACGME should explicitly define “good” supervision by specialty and by year of training. Explicit requirements for intensity and level of training for supervision of specific clinical scenarios should be provided

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) should use graduate medical education funding to provide incentives to programs with proven, effective levels of supervision. Although this action would require federal legislation, reimbursement rules would help to ensure that hospitals pay attention to the importance of good supervision and require it from their training programs

Resident physician work hours

Although the IOM “Sleep, supervision and safety” report provides a comprehensive review and discussion of all aspects of graduate medical education training, the report’s focal point is its recommendations regarding the hours that resident physicians are currently required to work. A considerable body of scientific evidence, much of it cited by the Institute of Medicine report, describes deteriorating performance in fatigued humans, as well as specific studies on resident physician fatigue and preventable medical errors.

The question before this conference was what work redesign and cultural changes are needed to reform work hours as recommended by the Institute of Medicine’s evidence-based report? Extensive scientific data demonstrate that shifts exceeding 12–16 hours without sleep are unsafe. Several principles should be followed in efforts to reduce consecutive hours below this level and achieve safer work schedules. The recommendations are:

Limit resident physician work hours to 12–16 hour maximum shifts

A minimum of 10 hours off duty should be scheduled between shifts

Resident physician input into work redesign should be actively solicited

Schedules should be designed that adhere to principles of sleep and circadian science; this includes careful consideration of the effects of multiple consecutive night shifts, and provision of adequate time off after night work, as specified in the IOM report

Resident physicians should not be scheduled up to the maximum permissible limits; emergencies frequently occur that require resident physicians to stay longer than their scheduled shifts, and this should be anticipated in scheduling resident physicians’ work shifts

Hospitals should anticipate the need for iterative improvement as new schedules are initiated; be prepared to learn from the initial phase-in, and change the plan as needed

As resident physician work hours are redesigned, attending physicians should also be considered; a potential consequence of resident physician work hour reduction and increased supervisory requirements may be an increase in work for attending physicians; this should be carefully monitored, and adjustments to attending physician work schedules made as needed to prevent unsafe work hours or working conditions for this group

“Home call” should be brought under the overall limits of working hours; work load and hours should be monitored in each residency program to ensure that resident physicians and fellows on home call are getting sufficient sleep

Medicare funding for graduate medical education in each hospital should be linked with adherence to the Institute of Medicine limits on resident physician work hours

Moonlighting by resident physicians

The Institute of Medicine report recommended including external as well as internal moonlighting in working hour limits. The recommendation is:

All moonlighting work hours should be included in the ACGME working hour limits and actively monitored. Hospitals should formalize a moonlighting policy and establish systems for actively monitoring resident physician moonlighting

Safety of resident physicians

The “Sleep, supervision and safety” report also addresses fatigue-related harm done to resident physicians themselves. The report focuses on two main sources of physical injury to resident physicians impaired by fatigue, ie, needle-stick exposure to blood-borne pathogens and motor vehicle crashes. Providing safe transportation home for resident physicians is a logistical and financial challenge for hospitals. Educating physicians at all levels on the dangers of fatigue is clearly required to change driving behavior so that safe hospital-funded transport home is used effectively.

Fatigue-related injury prevention (including not driving while drowsy) should be taught in medical school and during residency, and reinforced with attending physicians; hospitals and residency programs must be informed that resident physicians’ ability to judge their own level of impairment is impaired when they are sleep deprived; hence, leaving decisions about the capacity to drive to impaired resident physicians is not recommended

Hospitals should provide transportation to all resident physicians who report feeling too tired to drive safely; in addition, although consecutive work should not exceed 16 hours, hospitals should provide transportation for all resident physicians who, because of unforeseen reasons or emergencies, work for longer than consecutive 24 hours; transportation under these circumstances should be automatically provided to house staff, and should not rely on self-identification or request

Training in effective handovers and quality improvement

Handover practice for resident physicians, attendings, and other health care providers has long been identified as a weak link in patient safety throughout health care settings. Policies to improve handovers of care must be tailored to fit the appropriate clinical scenario, recognizing that information overload can also be a problem. At the heart of improving handovers is the organizational effort to improve quality, an effort in which resident physicians have typically been insufficiently engaged. The recommendations are:

Hospitals should train attending and resident physicians in effective handovers of care

Hospitals should create uniform processes for handovers that are tailored to meet each clinical setting; all handovers should be done verbally and face-to-face, but should also utilize written tools

When possible, hospitals should integrate hand-over tools into their electronic medical records (EMR) systems; these systems should be standardized to the extent possible across residency programs in a hospital, but may be tailored to the needs of specific programs and services; federal government should help subsidize adoption of electronic medical records by hospitals to improve signout

When feasible, handovers should be a team effort including nurses, patients, and families

Hospitals should include residents in their quality improvement and patient safety efforts; the ACGME should specify in their core competency requirements that resident physicians work on quality improvement projects; likewise, the Joint Commission should require that resident physicians be included in quality improvement and patient safety programs at teaching hospitals; hospital administrators and residency program directors should create opportunities for resident physicians to become involved in ongoing quality improvement projects and root cause analysis teams; feedback on successful quality improvement interventions should be shared with resident physicians and broadly disseminated

Quality improvement/patient safety concepts should be integral to the medical school curriculum; medical school deans should elevate the topics of patient safety, quality improvement, and teamwork; these concepts should be integrated throughout the medical school curriculum and reinforced throughout residency; mastery of these concepts by medical students should be tested on the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) steps

Federal government should support involvement of resident physicians in quality improvement efforts; initiatives to improve quality by including resident physicians in quality improvement projects should be financially supported by the Department of Health and Human Services

Monitoring and oversight of the ACGME

While the ACGME is a key stakeholder in residency training, external voices are essential to ensure that public interests are heard in the development and monitoring of standards. Consequently, the Institute of Medicine report recommended external oversight and monitoring through the Joint Commission and Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The recommendations are:

Make comprehensive fatigue management a Joint Commission National Patient Safety Goal; fatigue is a safety concern not only for resident physicians, but also for nurses, attending physicians, and other health care workers; the Joint Commission should seek to ensure that all health care workers, not just resident physicians, are working as safely as possible

Federal government, including the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, should encourage development of comprehensive fatigue management programs which all health systems would eventually be required to implement

Make ACGME compliance with working hours a “ condition of participation” for reimbursement of direct and indirect graduate medical education costs; financial incentives will greatly increase the adoption of and compliance with ACGME standards

Future financial support for implementation

The Institute of Medicine’s report estimates that $1.7 billion (in 2008 dollars) would be needed to implement its recommendations. Twenty-five percent of that amount ($376 million) will be required just to bring hospitals into compliance with the existing 2003 ACGME rules. Downstream savings to the health care system could potentially result from safer care, but these benefits typically do not accrue to hospitals and residency programs, who have been asked historically to bear the burden of residency reform costs. The recommendations are:

The Institute of Medicine should convene a panel of stakeholders, including private and public funders of health care and graduate medical education, to lay down the concrete steps necessary to identify and allocate the resources needed to implement the recommendations contained in the IOM “Resident duty hours: Enhancing sleep, supervision and safety” report. Conference participants suggested several approaches to engage public and private support for this initiative

Efforts to find additional funding to implement the Institute of Medicine recommendations should focus more broadly on patient safety and health care delivery reform; policy efforts focused narrowly upon resident physician work hours are less likely to succeed than broad patient safety initiatives that include residency redesign as a key component

Hospitals should view the Institute of Medicine recommendations as an opportunity to begin resident physician work redesign projects as the core of a business model that embraces safety and ultimately saves resources

Both the Secretary of Health and Human Services and the Director of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services should take the Institute of Medicine recommendations into consideration when promulgating rules for innovation grants

The National Health Care Workforce Commission should consider the Institute of Medicine recommendations when analyzing the nation’s physician workforce needs

Recommendations for future research

Conference participants concurred that convening the stakeholders and agreeing on a research agenda was key. Some observed that some sectors within the medical education community have been reluctant to act on the data. Several logical funders for future research were identified. But above all agencies, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is the only stakeholder that funds graduate medical education upstream and will reap savings downstream if preventable medical errors are reduced as a result of reform of resident physician work hours.

Keywords: resident, hospital, working hours, safety

Preface

In its landmark 1999 report “To Err is Human”, the Institute of Medicine estimated on the basis of two statewide studies1–3 that up to 98,000 patients die each year in the US due to medical error.4 Since that time, considerable efforts have been made to understand the causes and consequences of these errors, and to implement interventions to prevent or intercept them. Nevertheless, errors appear to be as common today as they were a decade ago. In November 2010, the US Department of Health and Human Service’s Office of the Inspector General estimated that up to 180,000 patients per year may die as a result of medical care,5 an extrapolation that would make harm due to medical care the third leading cause of death nationwide.6 Nearly half of these incidents were preventable, ie, due to error. In the same month, the North Carolina Patient Safety Study reported the results of a 10-center, six-year study that found no reduction over time in the baseline rate (25 harms per 100 admissions) due to medical care in North Carolina.7,8

While there are numerous reasons that errors and injuries due to medical care remain so prevalent, the traditional long working hours of providers, particularly resident physicians, appear to be an important root cause. The Harvard Work Hours, Health, and Safety Group found that interns working extended shifts reported making more medical errors (including those that harm or kill patients),9 had a 60% increased odds of suffering an occupational injury,10 and have twice the odds of suffering motor vehicle crashes on the drive home from work.11 Furthermore, in a randomized controlled trial, serious medical errors were found to be 36% more common on a traditional schedule with frequent extended shifts than on an intervention schedule that eliminated scheduled shifts longer than 16 consecutive hours.12,13 Subsequent studies have largely substantiated these findings. A systematic review of interventions that reduced or eliminated shifts over 16 hours found that 64% resulted in improved safety or quality; no intervention led to worse quality or safety.14 Similarly, a systematic review of the relationship between extended shifts and resident physician and patient safety found that outcomes were improved by shorter resident physician work shifts in 74% of studies; only 6% of the studies found any outcome to be worse with shorter shifts.15

In light of these emerging data and public concern over resident physician working hours,16 Congress and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality asked the Institute of Medicine to convene a committee to review all data on resident physician working hours and safety.17,18 After a year-long comprehensive study, the committee published a report in 2009, concluding that “the scientific evidence base establishes that human performance begins to deteriorate after 16 hours of wakefulness”, and called for the elimination of all resident physician shifts exceeding 16 hours without sleep. In addition, they called for numerous improvements in the organization and supervision of residency training, as well as external oversight by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), the professional body that has historically overseen residency programs.

The recommendations of the Institute of Medicine have profound implications for patients, residency programs, and the health care system. The conclusion that resident physicians’ traditional 24-hour work shifts are unsafe has created an upheaval in academic medicine, but one with the potential to yield a safer health care system. However, in order to realize this potential, the Institute of Medicine’s report needs to move from being merely a list of recommendations to being a well coordinated series of concrete changes in health care delivery and regulation.

To address this need, a diverse group of stakeholders was invited to attend a conference at Harvard Medical School in June 2010, at which the recommendations of the Institute of Medicine committee were discussed. From this discussion, we produced this White Paper which outlines the group’s recommendations regarding how to move forward.

In response to the Institute of Medicine report, the ACGME in September 2010 issued new standards to come into effect on July 1, 2011. Unfortunately, the new rules stop considerably short of the Institute of Medicine’s recommendations and those endorsed by this conference. In particular, the ACGME only applied the limitation of 16 consecutive work hours to first-year resident physicians and reduced the minimum time off between shifts from 10 to 8 hours. Policy makers, hospital administrators, and residency program directors who wish to implement safer health care systems must go far beyond what the ACGME will require. This White Paper should serve as a guide for that effort. We hope the exciting examples of programs that have been redesigned to provide a better educational experience within the necessary restrictions of working hours will encourage others to do likewise. The safety of our patients and our trainees requires nothing less. We believe that it is only through fundamental redesign of systems, including especially the redesign of residency care systems, that we will achieve the potential of the patient safety movement to reduce errors substantially and save lives.

Christopher P. Landrigan, MD, MPH and

Lucian Leape, MD

Conference Moderators

Introduction

The Institute of Medicine’s “Resident duty hours: Enhancing sleep, supervision and safety”18 is arguably the most comprehensive examination of the training of physicians since the publication of the Flexner Report 100 years ago. Formed at the behest of Congress, the Institute of Medicine’s panel of experts was chaired by Dr Michael Johns, an otolaryngology surgeon and chancellor of Emory University. Its 17 members included physicians and nurse educators, sleep scientists, patient safety and organizational development experts, a consumer, and a resident physician.

The group was directed to examine the scientific evidence linking acute and chronic sleep deprivation among resident physicians with clinical performance deficits leading to medical error.18 Twelve months, six days of public hearings, and countless discussions and drafts later, the committee produced a document which encompassed far more than reform of the hours that resident physicians spend in the hospital.

The report recommended new limits on resident physician work hours and workload, increased supervision, a heightened focus on resident physician safety, training in structured handovers and quality improvement, more rigorous external oversight of work hours and other aspects of residency training, and identification of expanded funding sources necessary to implement the recommended reforms successfully. The recommendations were based on the committee’s belief that:

“There is enough evidence from studies of resident physicians and additional scientific literature on human performance and the need for sleep to recommend changes to resident physician training and duty hours aimed at promoting safer working conditions for resident physicians and patients by reducing resident physician fatigue”

“Providing safe patient care during residency is a matter not just of hours at work, but also of the amount of effective supervision, sleep obtained, and a balanced workload”18

In the 18 months following its release, the Institute of Medicine report was discussed extensively by the ACGME, the organization that oversees the training of physicians in the US. The ACGME formed a Duty Hours Task Force made up of board of trustee members and other medical educators.19 The group began work soon after the Institute of Medicine report was published, a date coinciding with the ACGME’s promised five-year review of its 2003 Duty Hour Standards. The task force worked for 18 months. Multiple experts were invited to present before the group, and three additional research studies were commissioned.20–22 The prevailing sentiment, captured effectively in an extensive collection of testimonies provided at the June 2009 ACGME Congress on Duty Hours, was that many of the Institute of Medicine’s recommendations (and specifically those focusing on reduction of duty hours) should not be implemented.

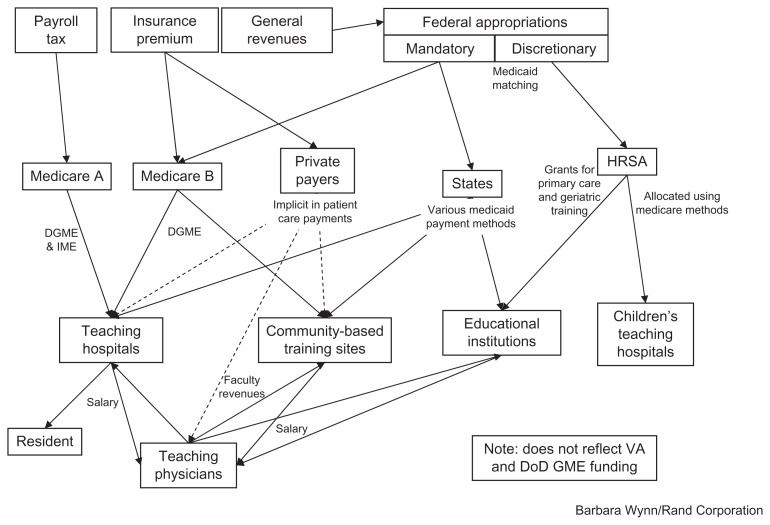

ACGME president and chief executive officer, Dr Thomas Nasca, addressed the Harvard conference participants on June 17, 2010. He estimated that resident physicians ( approximately 109,500 in 2010) represented about one quarter of all hospital-based physicians in the US. Taxpayers, through their contributions to the Medicare system, fund graduate medical education, at a cost of over $9 billion in 2009.23

Given the public’s investment in physician training and its expectation of receiving safe, high-quality care in the nation’s 1100-plus teaching hospitals,24 the Institute of Medicine report deserves broad and deep examination, and should involve not only input from the graduate medical education community, but from patients, resident physicians, policy makers, and the many other constituencies potentially affected by its far-reaching recommendations.

To that end, a conference entitled “Enhancing sleep, supervision and safety: What will it take to implement the Institute of Medicine recommendations?” was held at Harvard Medical School on June 17–18, 2010. Twenty-six stakeholders participated in the invitation-only roundtable discussion. They included quality improvement experts, medical educators and hospital administrators, consumers, regulators, sleep scientists, policy makers, a resident physician, and a medical student (see Appendix D for biographic information on participants). The group also included two members of the Institute of Medicine committee that produced the “Sleep, supervision and safety” report.

The two-day conference, moderated by Drs Christopher P Landrigan and Lucian Leape, was structured around the 10 major recommendations made by the Institute of Medicine. Each recommendation was introduced and discussed by an initial presenter as well as at least two additional respondents, followed by informal discussion. This format provided an opportunity for experts and a diverse group of stakeholders to present, discuss, and debate implementation strategies, including opportunities, obstacles, and concrete steps to address this important patient safety issue. Not every recommendation was endorsed by each invited conference participant. However, every recommendation made here was endorsed by the majority of this diverse group of experts and many were endorsed unanimously.

The goals of the conference were to produce and disseminate widely a White Paper that would:

Broaden exposure to the Institute of Medicine report beyond the medical community

Share the collective wisdom of experts in their fields and diverse stakeholders about how best to implement the 10 Institute of Medicine recommendations, ie, best practices for medical education innovators

Provide an impetus for change that will help pave the way towards creating a safer and more effective system for training the nation’s physicians

In September 2010 the ACGME issued new rules to go into effect on July 1, 2011, but unfortunately these stop considerably short of the Institute of Medicine’s recommendations and those endorsed by this conference. In particular, the ACGME only applied the limitation of 16 hours to firstyear resident physicians and reduced the minimum time off between shifts from 10 to 8 hours. In addition, other important IOM recommendations were disregarded. Hospitals, medical educators and policy makers committed to implementing safer systems of care must go further. This White Paper should serve as encouragement that further change is both possible and desirable.

Resident physician workload and supervision

“To improve the quality of care delivered to current and future patients, and to meet long term educational objectives, the committee recommends improvements to the content of residents’ work, a patient workload and intensity appropriate to learning, and more frequent consultations between residents and their supervisors.”

Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision and Safety (Medicine 2009, p. 19)

“Extreme time demands dilute the relationships between residents and faculty.”

Joel Katz, MD, Program Director, Internal Medicine

Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA

Harvard IOM Conference, June 17, 2010

Successful medical training combines formal education and experiential learning under the supervision of experienced physicians. By the end of training, a resident physician should be able to practice independently. Yet too often, a resident physician’s time is dominated by tasks with little educational value and a caseload so great that inadequate reflective time is left for learning based on clinical experience. In addition, supervision is often vaguely defined, discontinuous, and poorly monitored.

The Institute of Medicine’s “Sleep, supervision and safety” report describes in detail the underlying reasons for this deterioration, ie, a system of reimbursement that results in patients being sicker upon admission (and discharge) and exerts financial pressure to reduce length of hospital stay. More clinical service is expected both of resident physicians and attending physicians in shorter periods of time. These economic pressures, which started to be recognized by the late 1980s,25 were further exacerbated after 2003 when the ACGME enacted its first limits on working hours. Many teaching hospitals met this unfunded mandate by simply demanding more work from physicians-in-training and attending physicians alike.

Today the responsibilities of attending physicians “on service” are often so stressful and demanding that the typical schedule has been reduced from one month to two weeks or less. This discontinuity further dilutes the resident-attending physician relationship. Too much work and too little supervision may result in near-misses and preventable medical errors. In addition, patients overwhelmingly disapprove of resident physician working shifts that exceed 16 hours in duration, and believe that increasing their supervision could improve care.16

How can resident physicians receive the appropriate level of patient exposure and clinical training while ensuring patient safety? How is high-quality supervision defined, funded, monitored, and enforced? Conference participants considered these questions when reviewing the Institute of Medicine’s recommendations regarding resident physician workload and supervision (see Appendix B for a compilation of the 10 Institute of Medicine recommendations). Addressing excessive hospital workload and inadequate supervision could provide safer patient care and improve the training environment for resident physicians, as well as resident physician and attending satisfaction.27 Such changes could also potentially result in financial savings sufficient to pay for the additional cost of a care model in which resident physicians cover fewer patients and have more supervision.

Recommendations for resident physician workload

The ACGME should adjust resident workload requirements to optimize educational value; resident physicians as well as faculty should be involved in work redesign that eliminates nonessential and noneducational activity from resident physician duties

Mechanisms should be developed for identifying in real time when a resident physician’s workload is excessive, and processes developed to activate additional providers

Teamwork should be actively encouraged in delivery of patient care; historically, much medical training has focused on individual knowledge, skills, and responsibility; health care delivery has become more complex, so it will be essential to train resident and attending physicians in effective teamwork that emphasizes collective responsibility for patient care and recognizes the signs, both individual and systemic, of a schedule and other working conditions that are too demanding to be safe

Hospitals should embrace the opportunities that resident physician training redesign offers; hospitals should recognize and act on the potential benefits of work redesign, eg, increased efficiency, reduced costs, improved quality of care, and resident and attending job satisfaction

Lack of supervision has consequences. Resident physicians are held to the standard of a “reasonable provider” and are frequently named in malpractice lawsuits. Their errors result in malpractice payouts by insurers. The Malpractice Insurer’s Medical Error Prevention Study26 reviewed more than 1400 closed malpractice cases from five different insurers in 1984–2004, of which 889 were identified whereby both error and injury to a patient occurred. Of those, 240 (27%) involved trainees whose role in the error was judged to be at least moderately important. In 82% of the cases involving lack of supervision (106 of 129), failure of attending physicians to supervise was at issue.

The Controlled Risk Insurance Company (CRICO) insures more than 11,400 physicians, including 3700 resident physicians/fellows at 25 hospitals affiliated with the Harvard Medical School in the Boston area. According to Controlled Risk Insurance Company data, 15%–20% of the physicians named as defendants in historical malpractice cases (about 40 per year) were resident physicians.

A review of unpublished closed case data for the Controlled Risk Insurance Company between January 1, 2005 and May 31, 2010, revealed that:

One or more residents were involved as defendants in 154 cases, and 20% of those cases involved just a resident physician

Sixty percent (99 cases) were considered of high severity, and 15% higher in injury severity when note was taken of resident physician supervision and working hours

Disposition of cases involving resident physicians dropped/denied/dismissed in 39%, a defense verdict given in 24%, a plaintiff verdict in 1%, and settled in 36% of cases

Top major allegations against resident physicians that resulted in payouts involved surgical treatment (52 cases, $14.6 million), diagnosis-related issues (34 cases, $18.1 million), medical treatment (27 cases, $11.07 million), obstetric-related treatment (18 cases, $9.7 million), medication-related issues (eight cases, $2.1 million), and anesthesia-related treatment (seven cases, $1.9 million)

Top contributing factors (a case may have multiple factors identified) were supervision (29%), communication among providers regarding patient’s condition (26%), lack of/ inadequate assessment and/or failure to note clinical information (16%), and possible technical problems (16%)

High-quality supervision of resident physicians must be fostered in all disciplines of medicine. “Supervision in the operating room (and other procedure-based training) is both different and similar to supervision in the cognitive fields of medicine”, noted Dr James Whiting, director of surgical education at Maine Medical Center. “Doing an operation with a trainee is akin to dancing with a partner, who starts off dancing on your feet and then – as a chief resident – can do a complex dance and you say – go ahead and lead. Yet on the issue of independence, surgery isn’t different. At some point we want them to be able to ‘do this on their own’. How do you assess competency and give them independence while maintaining supervision? How are they going to respond in a crisis?”

But how do we get from the status quo to a training environment with high-quality supervision? Restructuring resident physician team structure, workload, and supervision can improve education, satisfaction, and quality of care. This hypothesis was tested in the internal medicine residency program at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. 27 The intervention group comprised a population of 15 intensive care patients (average 4–5 patients per intern), a team consisting of two resident physicians, two interns, two seniors and coattendings (one hospitalist and one primary care provider or medical specialist) who had extensive contact with trainees and patients, and a reduced frequency of overnight call. The control group, ie, the general medicine service, had a maximum ACGME census (average 6–8 patients per intern), and a team of one resident, two interns, and multiple care attendings with a variable degree of contact with trainees and patients, and a traditional overnight call schedule. Trainees worked an average of about 62 hours per week. The study found that, as compared with the control general medicine service, on the intensive care intervention service:

Resident physicians spent more of their time in educational activities (29% versus 7%)

Resident physicians were more satisfied (78% versus 55%)

Attending physicians were more satisfied, in that 70.7% felt the model was closest to their ideal teaching experience, and 90.2% approved of the dual attending-physician model

Patient satisfaction did not differ significantly between teams

Length of stay was shorter (4.10 versus 4.61 days); the cost of implementing the intensive care intervention was estimated at $500,000; this was counterbalanced by decreased intensive care costs of $600,000 due to shortened length of stay in the intensive care unit

The investigators concluded the importance of:

Strengthening connections between formal and experiential learning

Increasing opportunities for reflection to improve resident physicians’ educational experiences; this needs to be balanced with case volume

Increasing contact with a devoted teaching faculty enhances resident physicians’ experience

-

Fully engaging supervisors (senior resident physicians and faculty) in the direct care process without taking decision-making power away from the intern through;

clear role definitions

shared responsibility and accountability (requires longitudinal relationship)

integrated team building of trainee, supervisor and patient (eg, bedside rounds)

bidirectional feedback (eg, performance, teaching and documentation)

faculty compensation

faculty development

Conference recommendations for supervision

Attending physicians should supervise all hospital admissions; resident physicians should directly discuss all admissions with attending physicians; attending physicians should be both cognizant and have input into the care patients are to receive upon admission to the hospital

Inhouse supervision should be required for all critical care services, including emergency rooms, all intensive care units, and trauma services; resident physicians should not be left unsupervised to care for critically ill patients; in high acuity settings, physicians who have graduated from residency should provide direct supervision of resident physicians; supervising physicians should always be physically in the hospital to provide supervision of critically ill patients

The ACGME should explicitly define “good” supervision by specialty and by year of training; explicit requirements for intensity and level of training for supervision of specific clinical scenarios should be provided

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services should use graduate medical education funding to provide incentives for programs with proven effective levels of supervision. Although implementation of this recommendation may require federal legislation, reimbursement rules would help to ensure that hospitals pay attention to the importance of good supervision and require it from their training programs.

Resident physician working hours

“The Committee reviewed the scientific literature on sleep and human performance as well as evidence that continues to emerge concerning the benefits to patient safety, resident learning, and overall resident work life of well-structured limits to resident duty hours. The evidence was sufficient to recommend action now.”

Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision and Safety (Medicine 2009, p. 7)

“What work redesign and culture changes are needed to reduce work hours to the IOM-recommended levels?”

Charles A. Czeisler, MD, PhD,

Chief, Division of Sleep Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Although the “Sleep, supervision and safety” report provides a comprehensive review and discussion of all aspects of graduate medical education training, the report’s main focus is its recommendation for changes to the hours that resident physicians are currently required to work. Indeed, it was the quest to understand the link between resident physician work hours and patient safety that caused a subcommittee of the Oversight and Investigations of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce to request that the Department of Health and Human Services sponsor a study by the Institute of Medicine.

The Institute of Medicine recommended a significant departure from the current limits placed on resident physician work by the ACGME, which currently allow shifts of 30 consecutive hours (24 plus six more hours for continuity of care/transition of patient information). The Institute of Medicine concluded that no resident physician should work for more than 16 consecutive hours without sleep. If residency programs wanted to continue the practice of 30-hour shifts, the Institute of Medicine recommended that a protected five-hour sleep period occur between the hours of 10 pm and 8 am, and that no new patient care duties be allowed after 16 hours.

A considerable body of scientific evidence (much of it cited by the Institute of Medicine report) describes deteriorating studies on resident physician fatigue and preventable medical errors. A meta-analysis of 60 studies on the effect of sleep deprivation found, on average, after 24–30 hours of wakefulness, that “for clinical performance physicians performed at the 7th percentile of the comparison group”.28

Tired resident physicians make errors. In one study, one in every five interns reported making a fatigue-related mistake that injured a patient (a 700% increase when interns worked greater than 24 hours) and one in every 20 interns admitted to a fatigue-related mistake that resulted in the death of a patient (a 300% increase in months that interns worked five or more 24-hour shifts).9

Since the 2009 publication of the Institute of Medicine report, the peer-reviewed evidence has continued to describe preventable medical errors due to physician fatigue. There were 171% more surgical complications (eg, organ damage, hemorrhage) that occurred in day-time operations when the attending surgeon had had fewer than six hours of sleep opportunity after performing a night-time procedure.29

Reducing the marathon shifts that resident physicians now work poses both logistic and economic challenges. Unfortunately these challenges are often not addressed, because the ACGME’s core constituencies and multiple specialty societies hold fast to the belief that long hours are required of resident physicians in order to ensure competency and instill professionalism.30

The question before this conference was what work redesign and culture changes are needed to reform work hours as recommended by the Institute of Medicine’s evidence-based report?

Work redesign and culture change can (and are) being done with positive results. One study14 systematically reviewed the effects of reducing or eliminating shifts greater than 16 hours on patient safety and quality of care. Of the 11 programs described in previously published reports, seven reported significant improvement in patient safety and quality of care and four reported no change.

The conference featured case study experiences of innovative residency presented by program directors in three different specialties in the US, including internal medicine, general surgery, and obstetrics and gynecology. Also presented was a best practice entitled “Hospital at Night” from the UK, where implementation of the European Working Time Directive reduced work hours for trainees from 72 hours per week to 56 hours in 2004, and to 48 hours in 2009 (see Appendix A). What “lessons learned” did these pioneers impart?

Change is difficult and will always be resisted, such that if program directors wait until there is attending/ resident physician consensus for change, it will never happen

Program leadership is needed to redesign schedules to reduce hours; there will be inevitable early complaints, but the concerns diminish when resident physicians experience the benefits of the change

Involve resident physicians in the work redesign; they are able to identify where the schedule is dysfunctional and suggest changes

Continuity of care is enhanced, with fewer handovers when day and night float team care for the same patients

Tailor redesign to the program, no two programs are the same, so work redesign will differ among programs and within hospitals

Reform is more successful with buy-in from hospital administration; this should be framed in terms of reform leading to streamlined discharges, reduced length of stay, and improved resident physician/faculty job satisfaction; additional upfront costs can be recouped

Use technology (eg, simulation laboratories) to boost the learning curve

Where redesign involves additional attending physician responsibility and time, additional compensation may also be required

Schedule shifts with a buffer time period; work hours should be scheduled to allow resident physicians to stay longer to fulfill patient responsibilities and pursue educational opportunities, eg, a schedule should be made to allow a 13–14-hour shift to extend to 16 hours (see Tables 1, 2 and 3)

Table 1.

Innovation case study – internal medicine

| Summa Health System (affiliate of North East Ohio University College of Medicine), Akron, OH. | |

|---|---|

| Program Director – David B. Sweet, MD (sweetd@summa-health.org). | |

| 563 Bed Hospital: | 100–120 Medicine residency beds |

| Resident Physicians: | 68–45 IM Categorical + 6 IM Prelim PGY 1 + 10 Trans Yr Prelim PGY 1 + 7 FTE Rotators. [IM = Internal Medicine; PGY = Postgraduate Year; FTE = full time employee] |

| Schedule: | < 2004 – traditional 24 + 6 call > 2006 – 80% 12–13 hour calls / 20% 16 hour calls with Saturday cross-coverage to preserve 1 free “golden weekend” per month. |

| Impetus for Change: | Consistently over hours limits; literature supported reduced hours; support from ACGME Educational Innovation Project. |

| Obstacles to Implementation: | Inertia (fear of change / it can’t be done). |

| Cost: | No hiring of additional personnel; 3 elective months lost in 3 yrs; re-schedule continuity clinic on post-admitting days. |

| Secrets to Success: | Involve resident physicians and study work flow; minimize change for PGY 3s; create schedule to allow a buffer time to finish care tasks; expect to revise the schedule in the second year; use quality (education and continuity of care) metrics; promote more organized handovers. |

| Outcome: | Found that rested resident physicians read more, attended more didactic sessions; 7 of 16 June 2010 graduates presented research at national or international meetings. |

Table 2.

Innovation case study – Ob-Gyn

| Santa Clara Valley Medical Center (affiliated with Stanford University School of Medicine). | |

|---|---|

| Assoc. Program Director – Jennifer Domingo, MD (Jennifer.domingo@hhs.sccgov.org). | |

| 574 Bed Hospital: | with busy OB service (~5000 deliveries) |

| Resident Physicians: | 20–22 (15 OB, 3-4/mo FP, 2-3/yr FP Ob Fellows and 1 Trans/mo) |

| Problems with Previous Current Call System: |

|

| Changed to Night Float System July 1, 2010. NEW Schedule Establishes: |

|

| Advantages to New Schedule |

|

| Postscript |

|

Table 3.

Innovation case study in surgery

| Maine Medical Center (affiliate of Tufts School of Medicine), Portland, ME. | |

|---|---|

| Program Director – James F. Whiting, MD (whitij@mmc.org). | |

| 637 Bed Hospital | |

| Resident Physicians: | 20 |

| July 2008: | 270 work hour violations (in one month) as I assumed program director position. Non-compliance in every area; data inaccurate or nonexistent; no one knew the rules and attendings didn’t feel there was a problem. |

| Phase 1 – Figure out the problem: | Established administrative compliance policy; all violations looked into; sessions with resident physicians; attending retreat. |

| Phase 1 – Results: | Good compliance with work hour recording; learned certain services habitual offenders; systemic violations. |

| Phase 2: | Continuation of oversight and monitoring; tweaks to schedule to eliminate systemic violations; one large service split in two as service was too big to round efficiently. Mock ACGME survey was conducted and mandatory recovery day instituted (if resident physician looks like they would be tracking too many hours they’d go home). Attendings pay more attention to hours (Note: On-call surgical attendings are encouraged not to schedule elective surgery on post-call day). |

| Phase 3 – Culture change: | “Despite a failure to demonstrate any significant detrimental impact of the work hour rules through data, it has recently become fashionable to blame work hour rules for eroding the surgical culture of accountability and ownership. According to this line of thought, work hour rules come with significant unintended consequences: surgical residents are acquiring the mentality of shift workers, no longer assuming the same ownership that we attained through working 100 hour plus weeks. This is not something that can be measured, but we know it is happening nevertheless…. “This kind of thing would be much easier to ignore if it was not so corrosive to the morale of surgical residents and if it did not fly in the face of what I see in the role of surgical program director every day. What is the major number of hours that one must work to learn the lessons of responsibility and accountability anyway?... The ‘average’ surgeon in the United States works 60 to 70 hours a week, but somehow understands this noble quality of patient ownership whereas today’s residents are ‘shift workers?’….Responsibility and ownership will never go out of style, but how those values are manifested is changing. Our residents know that accountability and collaboration are not mutually exclusive. “I believe that the current generation of surgical residents are better than we were, and work hour restrictions are part of the reason. They are a technologically savvy, cooperative, balanced generation. They are more efficient than we were, more open to new ideas, and just as committed to their patients. They understand the public’s uneasiness with our infatuation with endurance as a stand-in for excellence….It is time to grow up and stop whining. The dinosaurs went extinct and our surgical heritage deserves to evolve.” |

| James F. Whiting Of Puppies and Dinosaurs: Why the 80-Hour Work Week is the Best Thing That Ever Happened in American Surgery Archives of Surgery, Vol. 145 (No. 4), April 2010 |

|

Home call: a problem still waiting to be addressed

Since the ACGME instituted its 2003 working hour limits, more residency programs, particularly in the surgical subspecialties, have moved some of their inhouse call to home call. The incentive for such programs is that the ACGME counts home call towards the 80-hour/week limit only when a resident physician or fellow has to come into the hospital to care for a patient. It is common sense that, like all medical staff, resident physicians prefer to work from home. Home call can provide good training for post-residency life an attending physicians. But when the workload is too great and/or the pages trivial, home call can become a safety problem whereby home call can worsen the accumulation of chronic sleep deprivation because, unlike hospital call where resident physicians only work a half-day post call, resident physicians/fellows on home call are expected to work a full post-call day, even if they have been awakened many times during the night to answer pages. Moreover, fellows often take home call in one-week blocks. This work pattern adds to chronic sleep deprivation.

Recommendations on work hours

Limit resident physician work hours to 12–16-hour maximum shifts

A minimum of 10 hours between shifts

Resident physician input in work redesign should be actively solicited

Schedules should be designed that adhere to principles of sleep and circadian science; this includes careful consideration of the effects of multiple consecutive night shifts, and provision of adequate time off after night work

Resident physicians should not be scheduled up to the maximum permissible limits; emergencies frequently occur that require resident physicians to stay longer than their scheduled shifts, and this should be anticipated in scheduling

Resident physicians’ work shifts

Hospitals should anticipate the need for iterative improvement as new schedules are initiated; be prepared to learn from the initial phase-in, and change the plan as needed

As resident physician work hours are redesigned, attending physicians should also be considered. A potential consequence of resident work hour reduction and increased supervisory requirements may be an increase in work for attending physicians. This should be carefully monitored, and adjustments to attending physician work schedules made as needed to prevent unsafe work hours or working conditions for this group

“Home call” should be brought under the overall limits of work hours. Work load and hours should be monitored in each residency program to ensure that resident physicians and fellows on home call are getting sufficient sleep

Medicare funding for direct medical education for each hospital should be tied to adherence to the resident physician work hour limits set down by the Institute of Medicine

Moonlighting by resident physicians

“ The Committee concludes that all moonlighting for patient care, whether at the training facility (internal moonlighting) or elsewhere (external moonlighting), should come within the 80-hour weekly limit and that all other duty hour parameters should apply.”

Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision and Safety (Medicine 2009, p. 251)

“Residents have an allergic reaction to limiting moonlighting, but if you care about patient safety then you have to care about monitoring moonlighting carefully”.

Farbod Raiszadeh, MD, PhD

Cardiology Fellow, Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, NY

President, Committee of Interns and Residents/SEIU Healthcare

Harvard IOM Conference Presentation, June 17, 2010

The Institute of Medicine report recommended including external as well as internal moonlighting in working hour limits. The report also called on hospitals that permit moonlighting to ensure a process whereby resident physicians would have to apply for permission and be able to evaluate that there was no adverse effect on the resident’s performance. The Institute of Medicine reported no recent national assessment of the degree to which resident physicians and fellows moonlight. 18 Conference discussion revealed that some specialties (eg, surgery) prohibit moonlighting, and that resident physicians who are permitted to moonlight view it as an important way to supplement their income, and as a valuable part of their training experience. Most participants felt that hospitals do a poor job of monitoring external moonlighting by resident physicians.

Recommendations on moonlighting

All moonlighting should be included in the ACGME’s working hour limits, and actively monitored. Hospitals should formalize a moonlighting policy and establish systems for actively monitoring moonlighting by resident physicians. If moonlighting is found to impair resident physician performance, it should be restricted as needed

Safety of resident physicians

“As residents acquire needed skills during their educational training, the degree of fatigue and workload they experience places them at risk for workplace injury, driving incidents, decreased physical and mental health, and weakened professional and personal relationships”.

Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision and Safety (Medicine 2009, p. 159)

“Of course we have to provide adequate transportation – it’s not a matter of finance, it’s a matter of priorities, this is what we have to do. But the real question is why are we putting them at risk in the first place?”

David Cohen, MD

Executive Vice President for Clinical and Academic

Development, Maimonides Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY

Patients are not the only victims of punishing schedules (see Table 4). The “Sleep, supervision and safety” report also addressed the harm done to resident physicians themselves. The report focused on two main sources of physical injury to resident physicians impaired by fatigue, ie, needle-stick exposure to blood-borne pathogens and motor vehicle crashes. The report also discussed numerous other personal and professional hazards, including burnout, depression, and the health deficits of likely weight gain.18

Table 4.

A hospital is a dangerous place – especially if you are tired

| Wide Range of Hazards | |

|

|

| Shift Work, Long Hours Impairs Functioning of Many Body Systems | |

|

|

| Sleep Deprivation Weakens the Healthcare Team Model | |

|

|

| Claire C. Caruso PhD, RN, Research Health Scientist National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health Harvard IOM Conference presentation, June 17, 2010 |

|

The Institute of Medicine made the strong recommendation that “sponsoring institutions immediately begin to provide safe transportation options (eg, taxi or public transportation vouchers) for any resident physician who for any reason is too fatigued to drive home safely”.18 Presumably the committee believed that its recommendation to reduce the number of hours that resident physicians were scheduled to work would address the other serious health consequences of fatigue.

Dangers of needle-stick injuries and motor vehicle crashes

Percutaneous injury puts resident physicians at risk of acquiring a blood-borne pathogen, eg, hepatitis C or human immunodeficiency virus. Results of a survey of 2737 interns documented a higher rate of exposure to injury when fatigued. First-year resident physicians reported sustaining more than twice the number of percutaneous injuries at night than during the day (odds ratio 2.04, confidence interval [CI] 1.98–2.11) and sustaining such injuries nearly twice as often while working extended shifts (24 hours or longer) compared with working a day shift only (odds ratio 1.61, CI 1.46–1.78).10

Similarly, working marathon shifts also increases the risk of motor vehicle crashes, injuring both resident physicians and others. In a national survey of interns, it was found that every extended work shift (more than 24 hours) scheduled in a month increased the monthly risk of a motor vehicle crash by 9.1% (95% CI 3.4–14.7) and increased the monthly risk of a crash during the commute home from work by 16.2% (95% CI 7.8–24.7).11

Responsibility for resident physician safety in the hospital rests with the employer. On the way to and from a resident physician’s home, it is less clear who is legally responsible for the safety of resident physicians. “Dram shop liability” refers to the body of law governing the liability of hospitals in which resident physicians cause death or injury to third parties (those not having a relationship with the hospital) as a result of fatigue-related car crashes and other accidents. Dram shop laws vary across states, but in some states the law may hold hospitals legally accountable for resident physicians’ motor vehicle crashes that happen on the way home from an extended-duration shift.

Providing safe transport home for resident physicians is a logistic and financial challenge for hospitals. Conference participants agreed that those supervising resident physicians should dictate when a resident physician is not allowed to drive home if drowsy. Most also agreed that forcing fatigued resident physicians not to drive themselves home was no more a threat to their personal liberty and self-reliance than a man at a bar who is inebriated and for whom the bartender calls a cab. Departing from the Institute of Medicine recommendations, the conference participants decided that after all 24-hour calls, the hospital has an obligation to provide resident physicians with a ride home from the hospital. Public transport was not viewed as a viable solution. “Being comatose on the subway can be dangerous,” commented conference participant Dr Farbod Raiszadeh, who described a time on the New York City subway system when he was supposed to get off at 86th Street and ended up 11 stops later on 14th Street.

Most importantly, providing safe transport home does not address the root cause of the increased risk of a motor vehicle crash, ie, fatigue. Reduce the risk of resident physicians reaching debilitating fatigue a priori, and the problem begins to disappear on its own.

There is still much work to be done on educating both resident and attending physicians about the dangers of fatigue. “This will require a fundamental shift in the medical training culture,” said Dr Kavita Patel. “The attitude is ‘being able to stay up 48 hours makes me better than someone else’. We need to work towards a place where physicians in a position of authority are willing to say ‘I’ve had enough; I know my limits. Maybe you need to get to know yours.”

Recommendations on resident physician safety

Fatigue-related injury prevention (including not driving while drowsy) should be taught in medical school and residency and reinforced with attending physicians; hospitals and residency programs must be informed that resident physicians’ ability to judge their own level of impairment is impaired when they are sleep-deprived; hence, leaving decisions about whether to drive or not to impaired resident physicians is not recommended

Hospitals should provide transport for all residents who report feeling too tired to drive safely; in addition, although consecutive working hours should not exceed 16, hospitals should provide transport for all resident physicians who for unforeseen reasons or emergencies work for longer than 24 consecutive hours; transport under this circumstance should be automatically provided to house staff, and should not rely on self-identification or a request

Training in effective handovers and quality improvement

“System changes are needed in addition to enhanced supervision, workload adjustment and fatigue prevention methods to enhance conditions for resident performance and patient safety. … A transformation in the medical environment is needed so that a system-wide culture of safety develops and a system of blame is replaced with one of shared responsibility”.

Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep Supervision and Safety (Medicine 2009, p. 263)

“I was blind to the mayhem,” described a resident, after spending a week observing all of the disciplines at work on an inpatient unit as part of a quality improvement project. “I never understood how this place works.”

As described by Maureen Bisognano, President and CEO, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Boston, MA

Harvard IOM Conference, June 17, 2010

The IOM “Sleep, supervision and safety” report recommends that resident physicians be trained in effective handover techniques and the science and practice of quality improvement. Resident physicians represent an estimated one out of every four hospital-based physicians, yet including them in hospital quality improvement efforts has been difficult to achieve.

Handover practice for resident physicians, attending physicians, and other health care providers has long been identified as a weak link in patient safety throughout all health care settings. The process by which resident physicians transfer responsibility of care at various transition points poses a potential opportunity to omit or dilute information that could affect patient care. A resident physician’s familiarity with a patient is extremely important, but resident physicians cannot remain continuously by the bedside of all their patients. Resident physician fatigue also poses a significant threat to patient safety.12

Policies to improve handovers must be tailored to f it the appropriate clinical scenario, recognizing that information overload can also be a problem; beyond the characteristics commonly acknowledged as part of quality handover practice (face-to-face in a quiet space, with minimal interruption, and use of both verbal and written communication tools), conference participants also stressed the need for multidisciplinary rounds at the bedside involving, whenever possible, patients and/or family members.

Electronically printed handovers have been demonstrated to improve resident physician performance and patient outcomes by reducing rates of adverse events and allowing resident physicians more time to spend on direct patient care;31 however, electronic reports cannot be seen as a substitute for teaching resident physicians how to exchange quality information, develop good overall communication skills, and recognize the importance of working in teams.

Communication errors and fatigue

Root cause analysis case reports from the Veterans Affairs National Center for Patient Safety from 153 medical centers and over six million patients found that approximately 70% of the root contributing factors in an adverse patient event or near miss are attributed to communication failures, and approximately 30% of these events are related to fatigue and scheduling

A Joint Commission review of sentinel events from 1995–2008 yielded similar statistics

Communication failure related to handoffs is a frequently cited contributing factor in malpractice claims

Multiple qualitative studies and surveys indicate that resident physicians view ineffective patient handoffs as common causes of adverse events

Edward J. Dunn, MD, ScD

Associate Chief, Performance Improvement, Lexington VA

Medical Center, Lexington, KY

Harvard IOM Conference presentation, June 17, 2010

At the heart of improving handovers is an attempt to improve quality. Quality improvement is the foundation of health services research, and has become a major focus of hospital administrators across the country, with various drivers, including Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services requirements, the Joint Commission, and the Affordable Care Act. Educating resident physicians about quality improvement has been shown to have a positive effect on patient outcomes,32,33 and is increasingly a requirement of medical training and certification, eg, the American Board of Medical Specialties Maintenance of Certification Program and the ACGME core competencies (Practice-Based Learning and Improvement and Systems-Based Practice) which apply to all US physicians in training.

Ferrari and the nature of a good handover

Highly reliable health care depends upon highly reliable handovers. Health care is now learning lessons from other industries, eg, racing and aviation, on how to improve handovers. Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in London set out to improve handovers between surgery and intensive care after a serious adverse event occurred when a child was transferred from the operating room to the intensive care unit but the room, staff, and ventilator were not ready. Hospital staff visited Ferrari in Maranello, Italy, to learn from those who have perfected the pit stop, ie, the epitome of perfect handovers and succinct, effective communication about racing crew changeovers. They showed Ferrari a video of a typical patient handover at Great Ormond Street Hospital. The Ferrari staff were appalled, and set out to redesign the process by:

Training each staff member for a specific task set

Developing protocols for each member of the team, with resident physicians leading in handover management

Sequencing the steps

Using the anesthesiologist as a “lollipop man” to wave the patient into a completely prepared ICU room

As a result, there was a 42% reduction in average number of technical errors per handover, and information omissions during handovers fell by 49%, with a slightly reduced time to transfer

Maureen Bisognano

President and CEO, Institute for Healthcare Improvement, Boston, MA

Harvard IOM Conference presentation, June 17, 2010

Recommendations on training in handovers

Hospitals should train attending and resident physicians in standardized effective handovers

Hospitals should create uniform processes for handovers that are tailored to meet each clinical setting. All handovers should be done verbally and face-to-face, but should also utilize written tools

When possible, hospitals should integrate handover tools into their electronic medical records systems. Electronic medical records systems should be standardized to the extent possible across residency programs in a hospital, but may be tailored to the needs of specific programs and services. The federal government should help subsidize hospital adoption of electronic medical records to improve signout

When feasible, handovers should include nurses, patients, and families

Involving resident physicians in quality improvement projects has the potential to demonstrate, at a critical time in medical training, that a focus on quality can improve care. However, moving from this abstract notion to concrete implementation is not always easily done. From the conference proceedings, one clear barrier identified to teaching quality improvement was a hospital culture which does not value quality improvement. Perhaps better understanding of the effect on patient outcomes would foster a culture in which resident physician involvement in quality improvement projects was made a priority. At the level of the faculty and resident physician interface, another barrier to engaging trainees is time constraints and overseeing multiple simultaneous quality improvement projects.34 A third barrier to effective quality improvement training is the lack of best practices and data to evaluate the effectiveness of the quality improvement teaching experience.

The conference attendees identified several ways to include resident physicians in meaningful “real life” quality improvement work. Examples included assigning resident physicians to root cause analysis teams and hospital patient safety committee meetings. Interdisciplinary morbidity and mortality case conferences should include a systems analysis component so that resident physicians learn how to analyze and carry out system fixes. Resident physicians should be required as part of their training to identify a real system problem, and devise a project to fix it.

Recommendations on training in quality improvement

Quality improvement and patient safety measures in hospitals require the participation of resident physicians; the ACGME should specify in their core competency requirement that resident physicians work on quality improvement projects. Likewise, the Joint Commission should require that resident physicians be included in quality improvement and patient safety programs at teaching hospitals. Hospital administrators and residency program directors should create opportunities for resident physicians to become involved in ongoing quality improvement projects and root cause analysis teams. Feedback on successful quality improvement interventions should be shared with residents and broadly disseminated

Quality improvement/patient safety concepts should be integral to the medical school curriculum. Medical school deans should elevate the topics of patient safety, quality improvement, and teamwork. These concepts should be integrated throughout the medical school curriculum and reinforced throughout residency. Mastery of these concepts by medical students should be tested in the United States Medical Licensing Examination steps

Federal government should support involvement of resident physicians in quality improvement efforts. Initiatives to improve quality by including resident physicians in quality improvement projects should be financially supported by the Department of Health and Human Services

Monitoring and oversight of the ACGME

“The committee concludes that the advantages of a strengthened ACGME monitoring process along with external oversight by both CMS and the Joint Commission would help assure the public that programs would be more likely to adhere to the rules, problems with duty hours compliance would be uncovered and dealt with properly, and there would be more rapid implementation of the committee’s recommended adjustments to duty hours.”

Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision and Safety (Medicine 2009, p. 81)

“It’s important that the public has trust in us. We’ve probably lost that trust and lost the trust in ourselves.”

David B. Sweet, MD

Program Director, Internal Medicine, Summa Health

System, Akron, OH

Harvard IOM Conference June 18, 2010

On June 17, 2010, the first day of the conference, participants were fortunate to hear a presentation from Dr Thomas Nasca, president and chief executive officer of the ACGME. Dr Nasca reported that, after publication of the Institute of Medicine study, the ACGME “convened the profession” to determine the best way to go about setting new standards. The process included the formation of a task force in May 2009 to review literature and testimony from organizations and individuals. Key elements were identified, which Dr Nasca described as:

Supervision

Graded authority and responsibility

Handovers and continuity of care from the patient’s standpoint

Resident, residency, graduate medical education “enterprise” engagement in patient safety and quality improvement programs

Range of sensitivity to fatigue

Resident safety

Impact of proposed changes on maturation of professionalism

On the issue of compliance, Dr Nasca emphasized that the ACGME “chose to take this on rather than give it to another entity because professional self-regulation is very important to us”. The ACGME believes that compliance with the new standards can be improved with the introduction of an annual Sponsor Site Visit Program. He told conference participants these site visits “could be unannounced,” that the sponsoring institution’s chief executive officer would be held responsible for the accuracy of the information provided, and that after the first year, the site visit information would be published on the ACGME website, so that “the degree of compliance or quality of education milieu will be ascertained in this visit and be publicly disclosed.”

Asked if this change were sufficient to assure the public, Dr Nasca replied: “We will leave it to them to tell us whether we’ve done enough. The ACGME is making its best effort to provide transparency and accountability. I don’t know what else we can do. We anticipate a significant amount of push-back from teaching hospitals, and we’re trying to make this (monitoring) as inexpensive as possible.”

Dr Nasca explained that there would be a 90-day comment period following publication of the proposed new rules, and that the ACGME would announce its final rules at the end of September 2010, with implementation of the new rules required by July 1, 2011.

Funding for the preannounced visits will come from additional fees charged to each institution. Dr Nasca explained that there are almost 9000 residency programs and that to monitor each annually would cost upwards of $50 million. However, limiting the annual visits to the 700 sponsoring institutions was believed to be a realistic goal. The ACGME will produce an annual report of each visit, noting deficiencies that must be corrected, although it was not clearly stated what the repercussions for unchanged deficiencies would be.