Abstract

Background

In the context of increasing awareness about the need for assessment of sleep duration in community and clinical settings, the use of questionnaire-based tools may be fraught with reporter bias. Conversely, actigraphy provides objective assessments of sleep patterns. In this study, we aimed to determine the potential discrepancies between parentally-based sleep logs and concurrent actigraphic recordings in children over a one-week period.

Methods

We studied 327 children aged 3–10 years, and included otherwise healthy, nonsnoring children from the community who were reported by their parents to be nonsnorers and had normal polysomnography, habitually-snoring children from the community who completed the same protocol, and children with primary insomnia referred to the sleep clinic for evaluation in the absence of any known psychiatric illness. Actigraphy and parental sleep log were concomitantly recorded during one week.

Results

Sleep logs displayed an average error in sleep onset after bedtime of about 30 minutes (P < 0.01) and of a few minutes before risetime in all groups. Furthermore, subjective parental reports were associated with an overestimated misperception of increased sleep duration of roughly one hour per night independent of group (P < 0.001).

Conclusion

The description of a child’s sleep by the parent appears appropriate as far as symptoms are concerned, but does not result in a correct estimate of sleep onset or duration. We advocate combined parental and actigraphic assessments in the evaluation of sleep complaints, particularly to rule out misperceptions and potentially to aid treatment. Actigraphy provides a more reliable tool than parental reports for assessing sleep in healthy children and in children with sleep problems.

Keywords: actigraphy, insomnia, sleep logs, snoring, sleep duration

Introduction

The assessment of sleep-wake patterns is a major component of sleep medicine in both the clinical and research settings. The availability of an unobtrusive, cost-effective, and practical tool for prolonged ambulatory recordings and for objective measures of both diurnal and nocturnal behaviors is highly desirable, particularly in pediatric populations. Therefore, the principle of assessing movement (ie, actigraphy), most commonly of the wrist, has emerged as a valuable objective technique in the sleep field. In this context, periods of activity and inactivity based on movement are being recorded by the actigraph, and further interpreted as an objective estimate of wake and sleep patterns. The actigraph stores information from accelerometers which register movement sampled several times a second.1,2 Actigraphic analyses principally depend on information regarding lights on/off over a 24-hour period commonly provided by the caregiver, either via a sleep log or sleep diary. Additionally, its placement, such as on the nondominant wrist, leg, or waist, and the scoring algorithm, are important factors to consider when using actigraphs3–5 and when comparing results.6,7 Nonetheless, since the late 1970s, a growing number of studies has demonstrated the validity of modern actigraphy in distinguishing between sleep and wakefulness, and in providing useful and reliable measures of sleep-wake organization and sleep quality, and our experience corroborates such findings in healthy children.3,8,9 Nonetheless, the validity of actigraphy interpretation remains limited by the fact that it does not measure brain waves, as does polysomnography, nor does it assess the subjective experience of sleep, such as sleep logs, diaries, or questionnaires. Furthermore, only a handful of studies have focused on school-aged children, and have tested the reliability and validity of actigraphy within a pediatric clinical sample.8,10–18

Sleep logs have often been used in the evaluation of children with common sleep problems, even though subjective reports are presumed to underestimate sleep disorders or misperceive sleep duration.8,19–21 Although subjective parental reports are essential in the evaluation of children’s sleep, we should recognize that a sleep problem in the child will affect the whole family. Therefore, the sleep patterns of children should be assessed in the context of potential responder bias concerning the definition, causation, and maintenance of pediatric sleep problems.22–24 Werner et al21 recently calculated agreement rates between actigraphy and a questionnaire in 50 otherwise healthy children aged 5–7 years using Bland and Altman plots to determine the interchangeability of the two methods. Agreement between actigraph and questionnaire was interpreted as acceptable, ie, displaying ≤30 minutes difference, for sleep start, sleep end, and assumed sleep duration, yet disagreement was apparent for total sleep duration and nocturnal wake time. Sadeh25–27 further emphasized the value of actigraphy as a more reliable measure than parental reports, provided that at least seven nights of recording were performed. These observations prompted us to hypothesize that sleep log-based parental reports of children’s sleep will be more accurate in children with sleep-related symptoms, but that such reports will overestimate sleep duration.

Methods

Subjects

This study was approved by the University of Louisville Human Research Committee, and informed consent was obtained from the legal caregiver for each participant. Subjects were randomly recruited from two ongoing studies and the pediatric sleep medicine clinic at Kosair Children’s Hospital. The parents were approached by a clinical psychologist or physician, and children were excluded if they had any chronic medical conditions, genetic, craniofacial syndromes, or neurobehavioral disorders.

Procedure

Children were prospectively recruited using a validated questionnaire28–30 from the Louisville public school community, and were otherwise healthy and nonsnoring or were habitual snorers. Children were also recruited from the sleep clinic if they were referred for evaluation and treatment of sleep onset or sleep maintenance insomnia in the absence of a known psychiatric illness. All children were assessed at home for a week, and underwent overnight polysomnography in the laboratory.

The assessment week was initiated on the night of the sleep study at the Pediatric Sleep Medicine Center, and included placement of an actigraph. Parents were instructed to complete daily sleep logs documenting their child’s sleep pattern. The sleep log requested information on the date, time for their child to fall asleep after lights off, bedtime and rise time, and consisted of an hourly divided timeline starting from 6 pm through 6 am with midnight clearly marked, and the night-time period centered on the log sheet. Parents were asked to indicate when the child was “out of bed”, “in bed”, and “asleep”. Qualitative information included comments such as, for example, “child moved to our bed”, medications taken, or information related to the use of actigraphy.

Actigraphy

The Actiwatch (MiniMitter Actiwatch®-64 Co, Inc, 1998–2003, version 3.4) is a 28 × 27 × 10 mm device weighing 17.5 g. For the actigraph, epoch registration of activity counts are determined by comparison, ie, counts for the epoch in question and those immediately surrounding that epoch are weighted with a threshold sensitivity value (activity count) that was originally set at 40 (activity 40, default, being medium sensitivity). The score = E − 2*(1/25) + E − 1*(1/5) + E0 + E + 1*(1/5) + E + 2*(1/25), with En being activity counts for the epoch and E0 being the scored epoch. Instructions involved marking on the sleep log when the device was taken off and why (for example “went swimming from 6 pm to 10 pm”), and parents were instructed to have their children wear the device continuously during the day on the nondominant wrist,3 except when at risk of getting wet. The actigraphy recordings and sleep log reports were concomitantly obtained. Activity counts that were equal to or below the threshold sensitivity value were scored as “sleep”, whereas they were considered as “awake” when exceeding the threshold sensitivity value. The activity-sleep interval was manually marked for each record, based on sleep log bedtime and risetime. The activity parameter of interest was total sleep time by activity, representing the amount of time between sleep start and sleep end, scored as “sleep”. Sleep start and sleep end were determined automatically as the first 10-minute period in which no more than one epoch (one minute) was scored as mobile, and likewise for the last 10-minute period, respectively. The activity algorithm enabled summation of the number of epochs that did not exceed the threshold sensitivity value, and therefore provided individual total sleep time for each night of recording.

Polysomnographic assessment

All children were accompanied by one of their caregivers who slept in the same room. Overnight polysomnography was performed in a quiet, darkened room with an ambient temperature of 24°C. The following sleep parameters31 were measured: chest and abdominal wall movement by respiratory impedance or inductance plethysmography, heart rate by electrocardiogram, and air flow, which was triply monitored with a sidestream end-tidal capnograph which also provided breath-by-breath assessment of end-tidal carbon dioxide levels (PETCO2; BCI SC-300, Menomonee Falls, WI), a nasal pressure cannula, and an oronasal thermistor. Arterial oxygen saturation was assessed by pulse oximetry (Radical; Masimo, Irvine, CA), with simultaneous recording of the pulse waveform. The bilateral electro-oculogram, eight channels of electroencephalogram, chin and anterior tibial electromyograms, and analog output from a body position sensor (Braebon Medical Corporation, Ogsdenburg, NY) were also monitored. All measures were digitized using a commercially available polysomnography system (Rembrandt, MedCare Diagnostics, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Tracheal sound was monitored with a microphone sensor (Sleepmate, Midlothian, VA), and a digital time-synchronized video recording was made.

Sleep architecture was evaluated by standard techniques32 and by scorers blinded to the condition of the child. Conventional sleep parameters were evaluated, ie, proportion of time spent in each sleep stage was expressed as a percentage of total sleep time, additionally subdivided into supine, side, and prone sleep position. Central, obstructive, and mixed apneic events were counted. Obstructive apneas are defined as the absence of airflow with continued chest wall and abdominal movement for a duration of at least two breaths.33 Hypopneas were defined as a decrease in oronasal flow of ≥50% with a corresponding decrease in arterial oxygen saturation of 4% or more and/or electroencephalographic arousal.33,34 The obstructive apnea hypopnea index was defined as the number of obstructive apneas and hypopneas per hour of total sleep time. Similarly, indices for apneic events in the supine, side, and prone sleep positions were calculated for rapid eye movement sleep and nonrapid eye movement sleep. Spontaneous arousal index and respiratory arousal index were defined as recommended by the American Sleep Disorders Association Task Force report, and were expressed as the total number of arousals per hour of sleep time.34,35

Statistical analysis

Paired t-tests and general linear modeling were used to analyze differences between sleep log reports and actigraphically derived parameters, in addition to descriptive statistics. General linear modeling with gender included as a potential confounder assessed group differences for parent-reported bedtime and risetime on the sleep log, and sleep onset and offset times were recorded by actigraphy. All analyses were two-tailed, and a value of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. SPSS version 17 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Sample characteristics

A total of 327 children (including 158 girls) aged 3.33–9.58 years (mean ± standard deviation, 6.58 ± 1.07) participated in this study. Three groups of children were studied, ie, a control group of 110 otherwise healthy, nonsnoring children from the community (48% female; mean age 6.6 ± 1.2 years), who were reported by their parents to be nonsnorers and had normal polysomnography; a group of 112 habitually snoring children from the community (39% female; mean age 6.2 ± 0.6 years), of whom 32 had an obstructive apnea hypopnea index of less than one/hour of total sleep time, 46 had an obstructive apnea hypopnea index of 1–5/hour of total sleep time, and 34 had an obstructive apnea hypopnea index of more than 5/hour of total sleep time; and a group of 105 children referred to the sleep clinic for insomnia in the absence of any known psychiatric illness (42% female; mean age 6.8 ± 1.4 years), with normal polysomnography. The groups did not differ in age [F(2,160) = 2.006, P = 0.138] or gender distribution [χ2(1) = 1.51, P = 0.273]. There were more African American children in the habitual snoring group [35%, χ2(1) = 8.51, P < 0.005], and there were more white Caucasians in the insomnia group [89%, χ2(1) = 7.42, P < 0.02].

Bedtime and sleep onset time

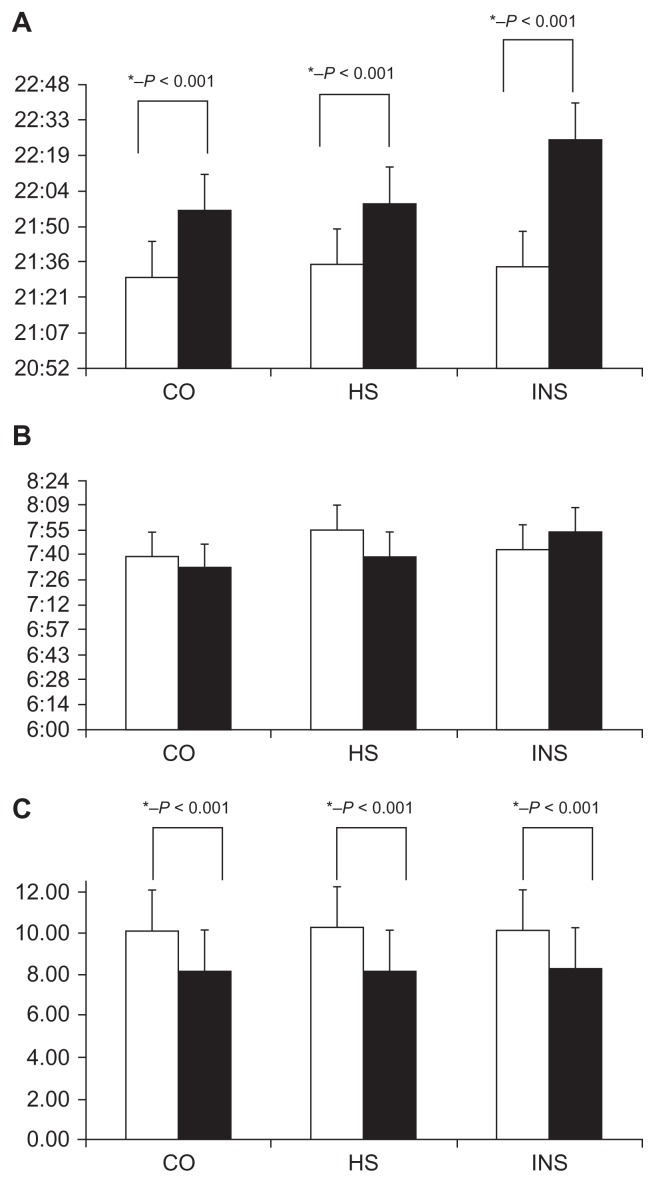

Averaged over all seven nights of the week, actigraphic sleep onset time was approximately 0:26 ± 0:03 minutes after parent-reported bedtime among children in the control group (see Table 1). For habitual snorers, weekly averaged sleep onset time was 0:36 ± 0:08 minutes and for the insomnia group was 0:49 ± 0:09 minutes later than reported by parents. Figure 1A reflects the average bedtime recorded by parents and sleep onset time per group.

Table 1.

Daily bedtime and sleep onset time

| Parental sleep log bedtime mean ± SD | Actigraphy sleep onset time mean ± SD | t-test | P value | Sleep start difference mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | |||||

| Control | 21:30 ± 1:03 | 22:00 ± 1:05 | t(95) = 7.76 | 0.000 | 0:30 ± 0:02 |

| Habitually snoring | 21:42 ± 1:00 | 22:16 ± 1:13 | t(22) = 3.08 | 0.006 | 0:34 ± 0:13 |

| Insomnia | 21:21 ± 1:02 | 22:08 ± 1:07 | t(43) = 5.25 | 0.000 | 0:47 ± 0:05 |

| Day 2 | |||||

| Control | 21:34 ± 1:01 | 21:59 ± 1:00 | t(94) = 8.01 | 0.000 | 0:25 ± 0:01 |

| Habitually snoring | 21:23 ± 1:02 | 21:57 ± 1:14 | t(22) = 2.52 | 0.020 | 0:34 ± 0:12 |

| Insomnia | 21:40 ± 1:12 | 22:33 ± 1:20 | t(41) = 5.35 | 0.000 | 0:53 ± 0:08 |

| Day 3 | |||||

| Control | 21:46 ± 1:05 | 22:15 ± 1:10 | t(91) = 10.15 | 0.000 | 0:29 ± 0:05 |

| Habitually snoring | 21:26 ± 1:02 | 21:58 ± 1:06 | t(21) = 2.88 | 0.009 | 0:32 ± 0:04 |

| Insomnia | 21:37 ± 1:06 | 22:40 ± 1:21 | t(41) = 5.62 | 0.000 | 1:03 ± 0:15 |

| Day 4 | |||||

| Control | 21:38 ± 1:03 | 22:02 ± 1:07 | t(94) = 6.91 | 0.000 | 0:24 ± 0:04 |

| Habitually snoring | 21:19 ± 0:55 | 21:57 ± 0:56 | t(21) = 3.29 | 0.004 | 0:38 ± 0:01 |

| Insomnia | 21:37 ± 1:14 | 22:25 ± 1:22 | t(38) = 5.34 | 0.000 | 0:48 ± 0:08 |

| Day 5 | |||||

| Control | 21:26 ± 0:54 | 21:52 ± 1:01 | t(94) = 6.91 | 0.000 | 0:26 ± 0:07 |

| Habitually snoring | 21:29 ± 0:53 | 22:01 ± 1:15 | t(20) = 2.54 | 0.020 | 0:32 ± 0:22 |

| Insomnia | 21:39 ± 0:57 | 22:17 ± 1:10 | t(40) = 4.77 | 0.000 | 0:38 ± 0:13 |

| Day 6 | |||||

| Control | 21:21 ± 0:54 | 21:50 ± 1:03 | t(93) = 6.50 | 0.000 | 0:29 ± 0:09 |

| Habitually snoring | 21:40 ± 1:28 | 22:27 ± 1:29 | t(20) = 2.78 | 0.012 | 0:47 ± 0:01 |

| Insomnia | 21:25 ± 1:05 | 22:17 ± 1:19 | t(40) = 6.17 | 0.000 | 0:52 ± 0:14 |

| Day 7 | |||||

| Control | 21:18 ± 0:52 | 21:40 ± 0:50 | t(92) = 4.56 | 0.000 | 0:22 ± 0:02 |

| Habitually snoring | 21:40 ± 1:28 | 22:27 ± 1:29 | t(18) = 3.56 | 0.002 | 0:47 ± 0:01 |

| Insomnia | 21:27 ± 1:19 | 22:14 ± 1:24 | t(40) = 4.78 | 0.000 | 0:47 ± 0:05 |

| Mean | |||||

| Control | 21:23 ± 0:54 | 21:50 ± 0:50 | t(92) = 8.42 | 0.000 | 0:24 ± 0:04 |

| Habitually snoring | 21:43 ± 1:26 | 22:28 ± 1:31 | t(18) = 7.56 | 0.000 | 0:48 ± 0:03 |

| Insomnia | 21:31 ± 1:21 | 22:16 ± 1:19 | t(40) = 8.78 | 0.000 | 0:45 ± 0:05 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Note: In P value column, figures that are in bold P < 0.00001, remaining figures P < 0.05.

Figure 1.

(A) Bedtime (open columns) and sleep onset (filled columns), (B) risetime (open columns), and sleep offset time (filled columns), and (C) sleep duration (open columns indicate parent reports and closed columns indicate actigraphy derived values).

Abbreviations: CO, contros; HS, habitual snorers; INS, insomniacs.

When controlling for gender, parent-reported bedtimes were not different among the three groups [F(2,157) = 0.123, P = 0.884]. Indeed, for the control group, bedtime was 21:31 ± 0:43, for the habitual snoring group was 21:35 ± 0:47, and for the insomnia group was 21:34 ± 0:55. Measured by actigraphy, averaged weekly sleep onset time occurred later in the habitual snoring group than in the other two groups [F(2,157) = 3.48, P = 0.033; controls 21:57 ± 0:46 after adjusting for gender; habitual snorers 22:00 ± 1:08; and insomniacs 22:26 ± 1:02]. Even though parent-reported bedtime did not differ among the groups, as can be seen in Table 1, the largest difference between bedtime and sleep onset time was found for the insomniac children. The greatest variance between parental report and actigraphy estimate of bedtime was found in controls (P < 0.01).

Risetime and sleep offset time

With respect to risetime, control children awoke on average about 10 minutes earlier by actigraphic measurement (10.2 ± 1.2 minutes) than by parental sleep log reports, but only on three of seven days of the week (see Table 2). For habitual snoring children, awakening differences between parent-reported risetime by sleep log and actigraphy did not reach statistical significance, whereas insomniac children awoke on two of seven days about 17 minutes later (16.9 ± 1.3 minutes), as measured by actigraphy. Figure 1B shows the average risetime recorded by parent-reported and actigraphy sleep-measured offset time for each of the groups.

Table 2.

Daily risetime and sleep offset time

| Parental sleep log risetime mean ± SD | Actigraphy sleep offset mean ± SD | t-test | P value | Sleep end difference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 1 | |||||

| Control | 7:33 ± 0:55 | 7:30 ± 1:00 | t(95) = 0.76 | 0.451 | 0:03 ± 0:05 |

| Habitually snoring | 7:42 ± 1:14 | 7:45 ± 1:06 | t(22) = −0.30 | 0.764 | 0:03 ± 0:08 |

| Insomnia | 7:29 ± 1:02 | 7:47 ± 1:06 | t(43) = −2.65 | 0.011 | 0:18 ± 0:04 |

| Day 2 | |||||

| Control | 7:51 ± 1:02 | 7:41 ± 0:56 | t(95) = 2.34 | 0.022 | 0:10 ± 0:06 |

| Habitually snoring | 7:31 ± 1:01 | 7:25 ± 1:11 | t(22) = 0.85 | 0.403 | 0:06 ± 0:10 |

| Insomnia | 7:52 ± 1:14 | 8:00 ± 0:54 | t(42) = −0.99 | 0.328 | 0:08 ± 0:20 |

| Day 3 | |||||

| Control | 7:57 ± 0:58 | 7:49 ± 1:04 | t(95) = 2.19 | 0.031 | 0:08 ± 0:06 |

| Habitually snoring | 7:31 ± 1:02 | 7:21 ± 1:00 | t(21) = 1.56 | 0.134 | 0:10 ± 02 |

| Insomnia | 7:51 ± 1:01 | 8:08 ± 1:03 | t(42) = −1.60 | 0.117 | 0:17 ± 0:02 |

| Day 4 | |||||

| Control | 7:49 ± 0:54 | 7:36 ± 0:52 | t(95) = 3.15 | 0.002* | 0:13 ± 0:02 |

| Habitually snoring | 7:41 ± 1:20 | 7:24 ± 1:23 | t(21) = 1.38 | 0.182 | 0:17 ± 0:03 |

| Insomnia | 7:47 ± 1:02 | 7:53 ± 0:59 | t(41) = −1.02 | 0.314 | 0:06 ± 0:03 |

| Day 5 | |||||

| Control | 7:35 ± 1:02 | 7:35 ± 1:06 | t(95) = 0.09 | 0.930 | 0:00 ± 0:04 |

| Habitually snoring | 8:32 ± 2:53 | 8:28 ± 1:14 | t(20) = 1.06 | 0.301 | 0:04 ± 0.4 |

| Insomnia | 7:47 ± 1:08 | 7:54 ± 1:13 | t(41) = −0.85 | 0.403 | 0:07 ± 0:05 |

| Day 6 | |||||

| Control | 7:33 ± 0:57 | 7:26 ± 0:51 | t(95) = 1.62 | 0.109 | 0:07 ± 0:06 |

| Habitually snoring | 7:50 ± 1:21 | 7:45 ± 1:30 | t(20) = 0.30 | 0.769 | 0:05 ± 0:09 |

| Insomnia | 7:33 ± 1:04 | 7:49 ± 1:05 | t(42) = −2.24 | 0.030 | 0:16 ± 0:01 |

| Day 7 | |||||

| Control | 7:32 ± 0:58 | 7:25 ± 0:56 | t(95) = 1.79 | 0.077 | 0:07 ± 0:02 |

| Habitually snoring | 8:05 ± 1:05 | 7:46 ± 1:03 | t(18) = 1.46 | 0.161 | 0:19 ± 0:02 |

| Insomnia | 7:51 ± 1:21 | 7:46 ± 0:59 | t(42) = 0.23 | 0.818 | 0:05 ± 1.22 |

| Mean | |||||

| Control | 7:35 ± 0:58 | 7:28 ± 0:56 | t(95) = 1.57 | 0.077 | 0:07 ± 0:02 |

| Habitually snoring | 8:06 ± 1:04 | 7:48 ± 1:03 | t(18) = 1.33 | 0.161 | 0:18 ± 0:02 |

| Insomnia | 7:47 ± 1:23 | 7:42 ± 0:57 | t(42) = 0.34 | 0.818 | 0:06 ± 0.02 |

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Note: In P value column, figures that are in bold P < 0.05,

indicates P < 0.01.

When controlling for gender, parent-reported risetimes were not different among the three groups [F(2,157) = 0.769, P = 0.465; controls 7:41 ± 0:39; habitual snorers 7:54 ± 1:03; insomniacs 7:44 ± 0:51]. When assessed by actigraphy, average sleep offset time occurred later for both habitual snorers and insomniacs when compared with controls [F(2,157) = 3.53, P = 0.032; controls 07:33 ± 0:40; habitual snorers 07:40 ± 1:01; insomniacs 07:54 ± 0:47].

Sleep duration over one week

Weekly sleep duration as reported by parental sleep logs versus objective actigraphically measured sleep duration, overestimated actual sleep duration by about one hour and 53 minutes per night in control children [t(95) = 27.84, P = 0.0000; 10:10 ± 0:36 versus 8:17 ± 0:35, Figure 1C]. A similar overestimate of about 2 hours 8 minutes per night occurred in the habitual snoring group [t(25) = 11.85, P = 0.0000; 10:24 ± 0:59 versus 8:16 ± 1:07], while in insomniac children, the overestimate was 1 hour 41 minutes per night [t(42) = 10.06, P = 0.0000; 10:10 ± 0:59 versus 8:29 ± 0:53].

Sleep onset latency

Sleep onset latency was assessed by asking parents to estimate the usual time that it took their children to fall asleep after lights out. These estimates were 23.7 ± 4.5 minutes for controls, 16.4 ± 7.5 minutes for habitual snorers, and 72.9 ± 17.5 minutes for insomniacs (P < 0.001 for insomniacs versus other groups; P < 0.05 habitual snorers versus controls). Actigraphic estimates of sleep onset latency were much shorter for insomniacs (P < 0.001 versus parent estimate of sleep onset latency, Table 1), and longer for the other two groups (P < 0.01 versus parental estimates in sleep logs, Table 1). Although trends emerged similar to those for parental estimates, there were no significant differences in sleep latency across the three groups (controls 39.7 ± 6.5 minutes; habitual snorers 35.4 ± 5.8 minutes; insomniacs 46.8 ± 15.9 minutes).

Discussion

The main objectives of this study were to assess potential discrepancies between parental sleep log reports and actigraphy in three groups of children with different sleep-related patterns, namely habitual snoring, clinically referred insomnia, and healthy nonsnorers. Regardless of the groups, parental estimates of sleep indicated significantly longer sleep duration when compared with actual sleep duration as derived from actigraphic recordings, with an overestimate of more than 60 minutes in all groups. We therefore view actigraphy as a more accurate estimate of sleep duration, and would recommend the use of daily sleep logs as a complementary tool in the evaluation of sleep problems in children.

Before we address the potential implications of our study, some limitations need to be mentioned. As with most sleep logs, bedtime is dependent on parental recording, and arrows denote in/out of bed with filled areas reflecting sleep. Thus, logs per se do not prompt the annotation of more “detailed” information from parents. Indeed, qualitative differences between sleep logs were noted across parents (for example, how many times the child got out of bed after bedtime, how many calls for a parent happened after lights-off, and what was the nature of such calls) and, in future, modifications of sleep logs and a more structured analysis of such information may provide valuable insights into different sleep disorders and parental perception. Additionally, we examined weekly sleep duration without filtering weekdays and weekends, such that our findings reflect a mixture of week and weekend recordings. Furthermore, we did not analyze intraindividual and interindividual variability in sleep patterns, since our main goal was to compare the two tools, but without attempting to define agreement between them. We also did not aim at clinical validation or diagnosis of the sleep disorders studied, but rather aimed to obtain both a subjective and an objective assessment of sleep concomitantly. Subjective assessments could theoretically provide more information on the perception and assessment of sleep quality, but in children the respondent is often the parent, and therefore such assessment is likely to be distorted by parental bias. Thus, adding actigraphy to sleep log tools should provide a valuable ambulatory and prolonged measurement that should enable better understanding of the child’s sleep patterns in the context of health and disease.

Our findings clearly reiterate the previously reported discrepancies between objectively measured sleep onset and sleep offset times when compared with subjective reports.33,36 However, we present for the first time valuable data that clearly show marked similarities in the discrepancies between objective and subjective sleep reporting, independent of whether the child is healthy or whether the child presents with sleep-related symptomatology. Accordingly, a clinical question beyond the child’s sleep quantity, aimed at assessing sleep quality, should be pursued, along with a special focus on processes revolving around determinants of sleep onset latency.36 In other words, the discrepancy in information between log and Actiwatch could be a valid starting point for identification of problems related to sleep onset in clinical practice. Scientifically, studies on these issues may preferably aim to investigate to what extent different methods are discrepant from one another, and thus enable utilization of their complementary values and compensate for their caveats in clinical sleep assessments.

Tryon6 elegantly discussed critical issues on how much a proxy sleep measure should approximate the “golden standard”, and summarized this issue into five major points: validity of actigraphy scores are good when compared with validity results of common medical and psychological tests; additional arguments towards the urge for actigraphy to perform better than the common medical or psychological tests need to be developed, especially knowing that actigraphy systematically differs from the “assumed errorless” polysomnography, because sleep onset is a gradual process, supplemental devices aiding the rather discretely measuring actigraph might be valuable (eg, a sleep switch device), and polysomnographic sleep scoring is not perfect, ie, actigraphy cannot agree more with polysomnography than polysomnography with itself; comparison of a unichannel with a multichannel measurement system has inherent and intrinsic limitations; and actigraphic inferences of sleep and wake states should be in the realm of committee practice standards guidelines and its limitations.

This investigator further stated “Knowing that actigraphy always identifies sleep onset latency before polysomnography means that actigraphy underestimates sleep onset latency and overestimates total sleep time and, therefore, percentage of sleep and sleep efficiency. This means that actigraphic measures establish upper bounds to sleep-onset latency and lower bounds to total sleep time, percentage sleep, and sleep efficiency. It is possible to effectively reason within these limits.” For such reasons, we propose to extrapolate the suggestions elaborated by Tryon6 to delineate the characteristics of a sleep onset spectrum (ie, quiescence and immobility, decreased muscle tone, and electroencephalographic sleep stage 1) and apply such concepts to the existence of a sleep offset spectrum, denoting a gradual process which is hard to capture by discrete measures, such as actigraphy or questionnaires. Possibly, the gradual shift from external to internal environment regarding sleep onset, or the inverse process for sleep offset, is likely to be best characterized when it is self-reported. In other words, a child can be immobile with decreased muscle tone but not asleep, and this state would not be then recognized by actigraphy. In contrast, self-report or polysomnography would recognize it. Thus, the small discrepancies noted for insomniac children in our study might underscore the presumed processes discussed above, and serve to promote the inherent increases in parental involvement and awareness of their children’s sleep that ultimately led to their referral for evaluation of insomnia.

The overestimation of total sleep time by more than one hour with subjective reporting was recently reported in a population-based study of 969 aging adults.37 Our study is suggestive that more accurate reporting in actigraphy, such as use of signals to indicate specific events in the transition from bedtime to actual sleep onset, may potentially aid accuracy, particularly when assessments of sleep duration in insomnia are needed. However, a number of other factors might play a role in promoting inaccurate estimates, such as use of medication, level of cognitive functioning, psychopathology, and sleep environment, as well as estimation of time per se, all of which may manifest a rather wide spectra of individual variability. Thus, filling out a rather rudimentary sleep log to capture such complexities may not yield very reliable reporting, especially over a lengthy period of time. As such, addition of an objective measurement such as actigraphy to the daily log and questionnaire might substantially aid in establishing more accurate reporting, and when the child is old enough, a frequently overlooked opportunity in general pediatric clinical practice, he/she should be regarded as a source-full informant.4 Age-adjusted questions or report forms should be applied. For instance, insomnia is a subjective complaint characterized by difficulty in initiating or maintaining sleep, or waking up too early, or nonrestorative sleep, accompanied by daytime impairment, occurring despite adequate opportunity and circumstances for sleep.37 Indeed, Van Den Berg et al37 in their study in the elderly made two remarkable findings, ie, firstly, when actigraphy was used as a surrogate reporter of poor sleep, participants subjectively estimated longer total sleep time, and secondly, subjectively poor sleepers mentioned in their diary a shorter total sleep time than corresponding actigraphic recordings. Indeed, sense of time is an interesting phenomenon when studying sleep, particularly perception of time following an awakening at night. To our knowledge, no study has addressed misperception of time in and by children.

In summary, our findings clearly indicate that sleep logs filled out by parents overestimate sleep duration, even when clinically referred insomnia is the presenting sleep problem. Improved integration of actigraphic recordings and sleep logs may be the preferable approach for sleep assessments in children.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants to DLM (HL-070911) and DG (HL-65270). The authors thank the parents and children for their cooperation and participation in this research.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Littner M, Hirshkowitz M, Davila D, et al. Practice parameters for the use of auto-titrating continuous positive airway pressure devices for titrating pressures and treating adult patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 2002;25:143–147. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Morgenthaler TI, Lee-Chiong T, Alessi C, et al. Practice parameters for the clinical evaluation and treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine report. Sleep. 2007;30:1445–1459. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.11.1445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadeh AJ, Urbach D, Lavie P. Actigraphically based automatic bedtime sleep-wake monitor scoring: validity and clinical applications. J Ambul Monit. 1989;2:209–216. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paavonen EJ, Fjallberg M, Steenari MR, Aronen ET. Actigraph placement and sleep estimation in children. Sleep. 2002;25:235–237. doi: 10.1093/sleep/25.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sadeh A, Sharkey KM, Carskadon MA. Activity-based sleep-wake identification: an empirical test of methodological issues. Sleep. 1994;17:201–207. doi: 10.1093/sleep/17.3.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tryon WW. Issues of validity in actigraphic sleep assessment. Sleep. 2004;27:158–165. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.1.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ancoli-Israel S, Cole R, Alessi C, Chambers M, Moorcroft W, Pollak CP. The role of actigraphy in the study of sleep and circadian rhythms. Sleep. 2003;26:342–392. doi: 10.1093/sleep/26.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadeh A, Lavie P, Scher A, Tirosh E, Epstein R. Actigraphic home-monitoring sleep-disturbed and control infants and young children: a new method for pediatric assessment of sleep-wake patterns. Pediatrics. 1991;87:494–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Spruyt K, Gozal D, Dayyat E, Roman A, Molfese DL. Sleep assessments in healthy school-aged children using actigraphy: concordance with polysomnography. J Sleep Res. 2011;20:223–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2010.00857.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Montgomery-Downs HE, Crabtree VM, Gozal D. Actigraphic recordings in quantification of periodic leg movements during sleep in children. Sleep Med. 2005;6:325–332. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sitnick SL, Goodlin-Jones BL, Anders TF. The use of actigraphy to study sleep disorders in preschoolers: some concerns about detection of nighttime awakenings. Sleep. 2008;31:395–401. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.3.395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Acebo C, Sadeh A, Seifer R, Tzischinsky O, Hafer A, Carskadon MA. Sleep/wake patterns derived from activity monitoring and maternal report for healthy 1- to 5-year-old children. Sleep. 2005;28:1568–1577. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.12.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tani P, Lindberg N, Nieminen-von Wendt T, et al. Actigraphic assessment of sleep in young adults with Asperger syndrome. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;59:206–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2005.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wiggs L, Stores G. Sleep patterns and sleep disorders in children with autistic spectrum disorders: insights using parent report and actigraphy. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2004;46:372–380. doi: 10.1017/s0012162204000611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Allik H, Larsson JO, Smedje H. Sleep patterns of school-age children with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J Autism Dev Disord. 2006;36:585–595. doi: 10.1007/s10803-006-0099-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wiggs L, Montgomery P, Stores G. Actigraphic and parent reports of sleep patterns and sleep disorders in children with subtypes of attentiondeficit hyperactivity disorder. Sleep. 2005;28:1437–1445. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.11.1437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crabtree VM, Ivanenko A, Gozal D. Clinical and parental assessment of sleep in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder referred to a pediatric sleep medicine center. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2003;42:807–813. doi: 10.1177/000992280304200906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Corkum P, Tannock R, Moldofsky H, Hogg-Johnson S, Humphries T. Actigraphy and parental ratings of sleep in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Sleep. 2001;24:303–312. doi: 10.1093/sleep/24.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Owens JA, Spirito A, McGuinn M, Nobile C. Sleep habits and sleep disturbance in elementary school-aged children. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2000;21:27–36. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200002000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paavonen EJ, Aronen ET, Moilanen I, et al. Sleep problems of school-aged children: a complementary view. Acta Paediatr. 2000;89:223–228. doi: 10.1080/080352500750028870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Werner H, Molinari L, Guyer C, Jenni OG. Agreement rates between actigraphy, diary, and questionnaire for children’s sleep patterns. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(4):350–358. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.4.350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stores G. Practitioner review: assessment and treatment of sleep disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1996;37:907–925. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1996.tb01489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gregory S. A Clinical Guide to Sleep Disorders in Children and Adolescents. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lumeng JC, Chervin RD. Epidemiology of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:242–252. doi: 10.1513/pats.200708-135MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadeh A. Evaluating night wakings in sleep-disturbed infants: a methodological study of parental reports and actigraphy. Sleep. 1996;19:757–762. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.10.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tikotzky L, Sadeh A. Sleep patterns and sleep disruptions in kindergarten children. J Clin Child Psychol. 2001;30:581–591. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sadeh A, Acebo C. The role of actigraphy in sleep medicine. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:113–124. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2001.0182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spruyt K, Gozal D. Pediatric sleep questionnaires as diagnostic or epidemiological tools: a review of currently available instruments. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.07.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gozal D. Sleep-disordered breathing and school performance in children. Pediatrics. 1998;102:616–620. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.3.616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Montgomery-Downs HE, O’Brien LM, Holbrook CR, Gozal D. Snoring and sleep-disordered breathing in young children: subjective and objective correlates. Sleep. 2004;27:87–94. doi: 10.1093/sleep/27.1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Standards and indications for cardiopulmonary sleep studies in children. American Thoracic Society. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 1996;153:866–878. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.153.2.8564147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rechtschaffen A, Kales A. A Manual of Standardized Terminology, Techniques and Scoring Systems for Sleep Stages of Human Subject. Washington, DC: National Institutes of Health; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Montgomery-Downs HE, O’Brien LM, Gulliver TE, Gozal D. Polysomnographic characteristics in normal preschool and early school-aged children. Pediatrics. 2006;117:741–353. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson AL, Jr, Quan SF. The AASM Manual for the Scoring of Sleep and Associated Events. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 35.EEG arousals: scoring rules and examples: a preliminary report from the Sleep Disorders Atlas Task Force of the American Sleep Disorders Association. Sleep. 1992;15:173–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spruyt K, O’Brien LM, Cluydts R, Verleye GB, Ferri R. Odds, prevalence and predictors of sleep problems in school-age normal children. J Sleep Res. 2005;14:163–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2005.00458.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Den Berg JF, Van Rooij FJ, Vos H, et al. Disagreement between subjective and actigraphic measures of sleep duration in a population-based study of elderly persons. J Sleep Res. 2008;17:295–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2008.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]