Abstract

Purpose

Population based studies have demonstrated that children and adolescents often complain of low back pain. A group-randomized controlled trial was carried out to investigate the effects of a postural education program on school backpack habits related to low back pain in children aged 10–12 year.

Methods

The study sample included 137 children aged 10.7 years (SD = 0.672). Six classes from two primary schools were randomly allocated into experimental group (EG) (N = 63) or control group (CG) (N = 74). The EG received a postural education program over 6 weeks consisting of six sessions, while the CG followed the usual school curriculum. A questionnaire was fulfilled by the participants at pre-test, post-test, and 3 months after the intervention finished. The outcomes collected were: (1) try to load the minimum weight possible, (2) carry school backpack on two shoulders, (3) belief that school backpack weight does not affect to the back, and (4) the use of locker or something similar at school. A sum score was computed from the four items.

Results

Single healthy items mostly improved after the intervention and remained improved after 3-month follow-up in EG, while no substantial changes were observed in the CG. Healthy backpack use habits score was significantly increased at post-test compared to baseline in the EG (P < 0.000), and remained significantly increased after 3-month, compared to baseline (P = 0.001). No significant changes were observed in the CG (P > 0.2).

Conclusions

The present study findings confirm that children are able to learn healthy backpack habits which might prevent future low back pain.

Keywords: Early intervention (education), Schools, Public health, Back pain, Backpacks

Introduction

Years ago, when the schoolchildren began to replace the satchel for backpacks, nobody could imagine that this seemingly harmless attachment would lead to numerous inquiries and investigations from health authorities. Variables such as weight of the school backpack, how to carry it or backpack features are currently under study in relation with low back pain (LBP).

The scientific literature has established that to carry backpacks that exceed 10 % of the schoolchildren’s weight causes adverse health effects such as changes in spinal curvature and repositioning error [1], abnormal changes in body balance and gait performance [2, 3], and modification of natural standing position [4, 5]. In addition overweight backpacks reduce pedestrian safety [7]. However, numerous studies show that most children carry a higher percentage than 10 % of body weight [8–10].

The schools are considered a privileged framework for developing an efficient healthcare education program. Some previous postural education programs have shown to be useful and efficient in preventing LBP as demonstrated in studies conducted on 9–12 year old boys and girls [11–13].

Population based studies have demonstrated that children and adolescents often complain of LBP, as shown by a study conducted in Majorca (Spain) among 16,357 participants aged 13–15 years, where 50.9 % of boys and 69.3 % of girls have suffered LBP at least once [14]. Due to the high LBP prevalence detected in this region, there is a need to carry out school-age interventions. Information on the effectiveness of schoolbased backpack health promotion programs is sparse [15–17]. In the present study, we aimed to investigate the effects of a postural education program on school backpack habits related to low back pain in children aged 10–12 year.

Methods

The study was performed in Majorca (Spain) during the academic year 2007–2008. The target group was children aged between 10 and 12 years, who belonged to the fifth and sixth grades. The rationale for choosing this age group was based on previous studies conducted in Majorca, which demonstrated that non-specific LBP prevalence is very low among children younger than 7 years old (1 %), whereas it is rather large in 13–15 years old children (i.e., 59.9 % in boys and 69.3 % in girls) [14]. These data suggest the need to intervene already in primary school children.

The schools were stratified in 12 strata according to three variables: setting (“urban”—town over 50,000 inhabitant-, or “rural”), size of the school (“small”—less than 25 children of the same age, meaning that all of them were grouped in the same class- or “big”—if split into more than one class-), and ownership and ruling body (“private”—privately owned, run, and financed-, “public”—owned, run, and totally financed by the State-, “concerted”—privately owned and run, but ruled by the State and mostly financed with public funds-). One school of each strata was randomly selected. Finally, two schools (6 classes) from the two largest strata (i.e., public + urban + big and public + rural + small) were selected to participate in the current back care education program.

Individual randomization is usually not possible in intervention studies at school settings, since the natural school groups (classes) must be kept as organized by the school. The current study is therefore a group-randomized controlled trial, in which groups instead of individuals are randomized. The six classes were randomized into experimental (3 classes) and control (3 classes) group.

Written permission from schools and parents of participants were required to participate in the study. All the participants and their parents were previously informed about the protocol and purposes of the study. The study protocol was approved by the local Ethical Committee at the University of Balearic Islands.

The study outcomes were assessed by means of a questionnaire that was fulfilled by the children at the three measurement times (baseline, post-test, and follow-up), and included data on LBP prevalence and potential risk factors that have proved to be associated with a higher risk for LBP in young people, such as the use of school backpacks [18–20].

Data on LBP prevalence included: lifetime LBP (never/once/sometimes/often/almost constantly) and last week LBP (yes/no). Data on potential risk factors included: gender (male/female), age, self-reported weight (kg), self-reported height (cm), self-reported physician diagnosis of scoliosis (yes/no/do not know), and asymmetry between the length of the legs (yes/no/don’t know). Healthy backpack habits included: try to load the minimum weight possible (yes/no), carry backpack on two shoulders (yes/no), belief that backpack weight does not affect to the back (yes/no), the use of locker or something similar at school (yes/no).

The questionnaire used in this study was previously tested [21] in a separate sample of 178 children of similar age (mean = 11.1 years old). Three different traits of the questionnaire were examined: (1) comprehensibility of the questionnaire and feasibility, (2) validity, (3) test–retest reliability (repeatability).

The present study examined the effect of the postural education program on the following study outcomes: try to load the minimum weight possible, carry backpack on two shoulders, belief that school backpack weight does not affect the back, and the use of locker or similar at school. Each item was coded as 0 = no and 1 = yes. A sum score was computed from the four items, namely healthy backpack use habits score (range from 0 to 4), so that the higher the score the healthier backpack use habits related to LBP.

A 6 weeks intervention program was implemented. Participants were evaluated three times: before the intervention (baseline, Month 0), after the intervention (post-test, Month 1.5), and 3 months after the intervention finished (follow-up, Month 4.5).

The intervention consisted of six sessions of 1 h (one per week, 4 theoretical, and 2 practical ones). All sessions were given by the same person (member of the research group) to avoid the possible influence of different teachers’ attitudes. The theoretical sessions were given during the school timetable as part of the subject Social and Natural Studies and the practical sessions were given during Physical Education classes.

The intervention program was based on current scientific literature [22–24]. During the theoretical sessions, the following topics were addressed: the human anatomy and physiology, the fundaments of LBP and risk factors, the promotion of physical exercise, ergonomics, and postural hygiene, and an analysis of the use of school bags. The practical sessions consisted of postural analysis, carrying objects (including backpacks), balance, breathing, and relaxation. The control group followed the regular school curriculum indicated by the National and Local educations programs.

The analyses were performed with those participants that had complete data at the three measurement points (baseline, post-test, and month 3) using PASW (Predictive Analytics SoftWare, formerly SPSS), version 19.0 SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA. The level of significance was set at <0.05 for all the analyses. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Chi-squared tests were performed, as appropriate, to study group differences at baseline. In order to examine the effect of the intervention, we used repeated measures analysis of co-variance (ANCOVA); with healthy backpack habits score at baseline, post-test, and follow-up outcome values as dependent variable, study group (experimental vs. control) as fixed factor, and sex and age as covariates. A significant interaction between group and time from baseline to post-test indicate an effect attributed to the intervention. Post hoc analyses were also performed to test if significant changes took place in experimental and control group between the different measurement points. For exploratory purposes, we also run a non-parametric test (Wilcoxon matched-pair signed-rank) to examine if this decision could affect the results.

Results

A total of 145 participants completed the baseline assessment; 142 participants completed the assessment at post-test (dropout rate = 1.01 %) and 137 at follow-up (dropout rate = 1.06 %). Dropout rates were similar in the experimental and control (1.1 vs 1.0 %, respectively) groups.

Characteristics of the study sample by study group are shown in Table 1. Participants were 10.7 years old and had 40 kg, 146 cm and 19 kg/m2 of weight, height, and body mass index, respectively. Lifetime LBP prevalence rate was 69.3 % in the whole study sample (31.4 % only once, 22.6 % sometimes, 1.5 % often, 2.9 % almost constantly). Ignoring the cases in which participants only had LBP once, the prevalence was 38 % (from sometimes to almost constantly). Last week LBP prevalence was 13.9 %. The average weight of backpack was 4.83 kg, and in terms of percentage of body weight of the children was 12.57 %. The percentage of children having healthy backpack use habits is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study sample at baseline by study group

| Total sample (N = 137) | Experimental group (N = 63) | Control group (N = 74) | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 10.72 (0.672) | 10.83 (0.636) | 10.64 (0.694) | 0.099 |

| Weight (kg) | 39.77 (7.992) | 39.17 (7.166) | 40.28 (8.648) | 0.420 |

| Height (cm) | 146.2 (9.177) | 147.8 (9.706) | 144.9 (8.529) | 0.058 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 18.51 (2.711) | 17.86 (2.347) | 19.06 (2.887) | 0.009 |

| Bag weight (kg) | 4.834 (1.525) | 4.429 (1.493) | 5.178 (1.475) | 0.004 |

| Bag weight-to-body weight ratio (%) | 12.57 (4.595) | 11.53 (4.563) | 13.45 (4.466) | 0.014 |

| Healthy backpack use habits score | 2.394 (0.902) | 2.174 (0.959) | 2.581 (0.811) | 0.008 |

| Total sample (N = 137) | Experimental group (N = 63) | Control group (N = 74) | Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Lifetime LBP (ever) | 42 (30.7 %) | 18 (28.6 %) | 24 (32.4 %) | 0.711 |

| Lifetime LBP: sometimes/often/almost constantly | 52 (38.0 %) | 27 (42.9 %) | 25 (33.8 %) | 0.294 |

| Last week LBP | 19 (13.9 %) | 6 (9.5 %) | 13 (17.6 %) | 0.177 |

| Diagnosis of scoliosis | 14 (10.2 %) | 7 (11.1 %) | 7 (9.5 %) | 0.753 |

| Asymmetry of legs’ length | 10 (7.3 %) | 3 (4.8 %) | 7 (9.5 %) | 0.296 |

| Try to load the minimum weight possible | 114 (83.2 %) | 48 (76.2 %) | 66 (89.2 %) | 0.065 |

| Carry backpack on two shoulders | 121 (88.3 %) | 54 (85.7 %) | 67 (90.5 %) | 0.431 |

| Belief that backpack weight does not affect to the back | 19 (13.9 %) | 5 (7.9 %) | 14 (18.9 %) | 0.083 |

| The use of locker or similar at school | 74 (54.0 %) | 30 (47.6 %) | 44 (59.5 %) | 0.174 |

LBP indicates low back pain

aOne-way analyses of variance and Chi-squared tests were used to analyse group differences in continuous and nominal variables, respectively

No differences in the percentage of boys and girls (52.8 and 48.2 %, respectively) were observed between the study groups (P = 0.9). Participants from both study groups had similar characteristics at baseline, except for body mass index, school backpack, and school backpack-to-body weight ratio, that were lower in the experimental group (~1 kg/m2, P = 0.01). LBP prevalence and healthy backpack use habits did not differ between study groups. Initial differences were observed in the healthy backpack use habits score between the study groups (P = 0.008).

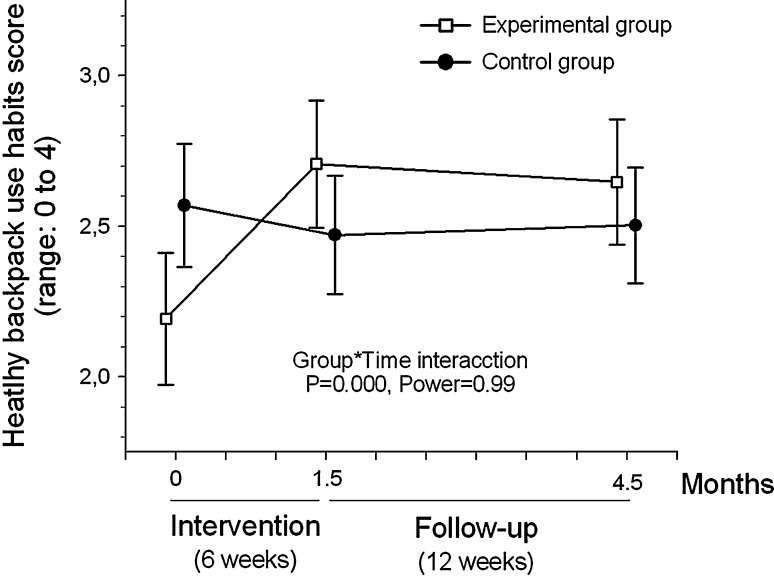

Figure 1 graphically shows how single healthy items mostly improved after the intervention and remained improved after 3 months of follow-up in experimental group, while no substantial changes are observed in the control group. Repeated measures ANCOVA (Fig. 2) revealed a significant increase in healthy backpack use habits score in the experimental group compared with the control group, after adjusting for age and sex (Group × time interaction, P < 0.001). A high statistical power was observed (i.e., power = 0.99). The effects remained unchanged after additional adjustment for baseline levels of the healthy backpack use habits score or baseline body mass index. Post hoc analyses showed that healthy backpack use habits score was significantly increased at post-test compared to baseline in the experimental group (P < 0.001), and remained significantly increased after 3 months of follow-up, compared to baseline (P = 0.001). No significant changes were observed in the control group (P > 0.2).

Fig. 1.

Percentage of participants having healthy school backpack habits according to study group at baseline, post-test, and follow-up. Items studied: A try to load the minimum weight possible, B carry backpack on two shoulders, C belief that school backpack weight does not affect to the back, D the use of locker or similar at school

Fig. 2.

Healthy backpack use habits score at the three times of measurement by study group, after adjustment for age and sex. Circles and squares represent means and error bars represent 95 % confidence intervals

However, when the study is a group-randomized controlled trial instead of individual-randomized controlled trial, there are often differences at baseline. To test if this fact could affect the outcome of this study, we repeated the analysis using one-way ANCOVA, with the difference pre-post as dependent variable, group as fixed factor and additional adjustment for habit score at baseline (to control for initial differences). The results did not change, i.e., the experimental group increased significantly after the intervention (P = 0.001) and the score level remained high 3 months later (P = 0.012). No changes were observed in the control group.

Wilcoxon matched-pair signed rank tests confirmed the results indicated above (data not shown). The experimental group had a significantly better healthy backpack use habit score after the intervention (P < 0.001) and did not change from the post-test to the follow-up assessment (P = 0.773). The control group did not change from baseline to post-test (P = 0.191) or from post-test to follow up (P = 0.772) assessments.

Discussion

The heavy weight of school bag in terms of the percentage of body weight of the children was reported as 12.57 % in the present study, 10.7 % in the United States [25], 9.6 and 9.9 % in England [26], 14.7 % in Greece [8], 19.9 % in Italy [6], 14.7 % in Holland [9].

The results suggest that a postural education program implemented in children can positively influence backpack habits related to LBP. In addition, this positive effect seems to remain after 3 months of follow-up. Due to the high prevalence of LBP in adolescents [14, 26] and in adults [27], as well as to the high budget associated to LBP [28], it is important to invest time, effort, and economic resources on preventing LBP. In this context, much research is still needed to establish the potential of school-based postural education program on incident LBP. The present study provides some promising findings suggesting that children are sensitive to learn and change attitudes if they are properly stimulated, in agreement with previous studies in elementary schoolchildren [10, 16, 29].

Feingold and Jacobs [10] implemented a back education program in 17 participants (11–12 year), randomly sorted into a control group and an intervention group. The back care promotion program consisted of a lecture describing why it was important to wear a school backpack properly; the effects of wearing a backpack improperly; techniques describing how to wear a backpack properly; and a hands-on session in which participants learned to load, lift, adjust, and wear a backpack properly. Results of the quantitative data provided no conclusive evidence to show that education on proper backpack wearing had an effect on posture in middle school students. On the other hand, the qualitative data demonstrated that quality of life (musculoskeletal discomfort) was improved for members of the intervention group, and the 100 % of them commented on how they changed the way they wore their backpack.

Goodgold and Nielsen [16] conducted a backpack health promotion program in 252 children aged 10–12 years. The program consisted in one session evaluating the backpack use (type, how carried), locker usage, use of strategies to reduce backpack weight, self-perceptions (heaviness, comfort), history of back pain and recurrence, and belief that improper backpack use can cause injury. The postural program resulted in positive changes, 42 % of participants changed the way they used their backpack and 63 % reported that the backpack program was worthwhile.

In future research it would be interesting to involve parents to improve the quality of the intervention program, because a major problem is that most of parents do not know the weight of their children’s backpacks, as demonstrated in a study in 2003 [30].

This study has several limitations. The use of self-reported postural behavior can be a limitation. More objective techniques such as direct observation or the use of a candid camera are available, but it is extremely difficult to follow a child over a whole day or week. In this study, we assessed school backpack habits using dichotomic questions (i.e., answers Yes/No). Future studies should consider the possibility to include more answer options (e.g., Likert-type) to improve the precision of the measure. The study sample participating in this study is relatively small, yet a high statistical power was observed in our analyses. Another limitation could be the relatively short period of follow-up. Longer follow-up periods will provide information about how long the positive effects of the intervention can be retained by the children. This would allow to identify how often the postural education sessions need to be implemented to succeed. Moreover, studies using a longer time frame would be able to examine the long-term effects of this intervention on LBP. An inherent limitation to all studies of low back pain is the need to rely on participant recall. A strength of this study is the small dropout rate observed (1 %). This fact limits the possibility of biased results, and avoids the need of applying sensitivity analyses and multiple computation methods. Of note is also that the questionnaire used in this study was previously tested [24] for correct understanding of the children, validity and reliability in a sample of similar characteristics.

The present study findings confirm that children are able to learn healthy backpack habits which might prevent future LBP. We are aware that implementation of programs in school is difficult due to the fact that the school curriculum has to cover many other subjects and time is limited. Our results are promising and suggest that incorporating back care education in the training of future primary school teachers, and also encourage researchers to carry out intervention studies to determine the best way to reduce the prevalence of back pain, especially among children.

Acknowledgments

No grant or external financial supports were received for this research. CEIP Establiments and CEIP Gabriel Comas I Ribas, both are primary schools from Majorca, and their students and staff are thanked for their contribution to this research.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Chow DHK, Ou ZY, Wang XG, et al. Short-term effects of backpack load placement on spine deformation and repositioning error in schoolchildren. Ergonomics. 2010;53(1):56–64. doi: 10.1080/00140130903389050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.LaFiandra M, Wagenaar RC, Holt KG, et al. How do load carriage and walking speed influence trunk coordination and stride parameters? J Biomech. 2003;36(1):87–95. doi: 10.1016/S0021-9290(02)00243-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chow DH, Kwok ML, Cheng JC, et al. The effect of backpack weight on the standing posture and balance of schoolgirls with adolescent idiopathic scoliosis and normal controls. Gait Posture. 2006;24(2):173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al-Khabbaz YS, Shimada T, Hasegawa M. The effect of backpack heaviness on trunk-lower extremity muscle activities and trunk posture. Gait Posture. 2008;28(2):297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bauer DH, Freivalds A. Backpack load limit recommendation for middle school students based on physiological and psychophysical measurements. Work. 2009;32:339–350. doi: 10.3233/WOR-2009-0832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Negrini S, Carabalona R. Backpacks on! Schoolchildren’s perceptions of load, associations with back pain and factors determining the load. Spine. 2002;27(2):187–195. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200201150-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwebel DC, Pitts DD, Stavrinos D. The influence of carrying a backpack on college student pedestrian safety. Accid Anal Prev. 2009;41:352–356. doi: 10.1016/j.aap.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korovessis P, Koureas G, Papazisis Z. Correlation between backpack weight and way of carrying, sagittal and frontal spinal curvatures, athletic activity, and dorsal and low back pain in schoolchildren and adolescents. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004;17:33. doi: 10.1097/00024720-200402000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Van Gent C, Dols JJ, de Rover CM, et al. The weight of schoolbags and the occurrence of neck, shoulder, and back pain in young adolescents. Spine. 2003;28(9):916–921. doi: 10.1097/01.BRS.0000058721.69053.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feingold AJ, Jacobs K. The effect of education on backpack wearing and posture in a middle school population. Work. 2002;18:287–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cardon GM, De Clercq DL, De Bourdeaudhuij IM. Back education efficacy in elementary schoolchildren: a 1-year follow-up study. Spine. 2002;27:299–305. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200202010-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mendez FJ, Gomez-Conesa A. Postural hygiene program to prevent low back pain. Spine. 2001;26:1280–1286. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200106010-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vidal J, Borras PA, Ortega FB, et al. Effects of postural education on daily habits in children. Int J Sports Med. 2011;32(4):303–308. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1270469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kovacs FM, Gestoso M, Gil del Real MT, et al. Risk factors for non-specific low back pain in schoolchildren and their parents: a population based study. Pain. 2003;103:259–268. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00454-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cardon G, De Bourdeaudhuij I, De Clercq D. Knowledge and perceptions about back education among elementary school students, teachers, and parents in Belgium. J Sch Health. 2002;72:100–106. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2002.tb06524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodgold SA, Nielsen D. Effectiveness of a school-based backpack health promotion program: backpack Intelligence. Work. 2003;21:113–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Skaggs DL, Early SD, D’Ambra P, et al. Back pain and backpack in school children. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26:358–363. doi: 10.1097/01.bpo.0000217723.14631.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chiang HY, Jacobs K, Orsmond G. Gender-age environmental associates of middle school students’ low back pain. Work. 2006;26:19–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Diepenmaat AC, van der Wal MF, de Vet HC, et al. Neck/shoulder, low back, and arm pain in relation to computer use, physical activity, stress, and depression among Dutch adolescents. Pediatrics. 2006;117:412–416. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siambanes D, Martinez JW, Butler EW, et al. Influence of school backpacks on adolescent back pain. J Pediatr Orthop. 2004;24:211–217. doi: 10.1097/01241398-200403000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Palou P, Kovacs FM, Vidal J, et al. Validation of a questionnaire to determine risk factors for back pain in 10–12 year-old school children. Gazz Med Ital Arch Sci Med. 2010;169(5):199–205. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burton AK, Balague F, Cardon G, et al. Chapter 2. European guidelines for prevention in low back pain: November 2004. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(suppl 2):S136–S168. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-1070-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Geldhof E, Cardon G, De Bourdeaudhuij I, et al. Effects of back posture education on elementary schoolchildren’s back function. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:829–839. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-0199-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Tulder M, Becker A, Bekkering T, et al. Chapter 3. European guidelines for the management of acute nonspecific low back pain in primary care. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(suppl 2):S169–S191. doi: 10.1007/s00586-006-1071-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moore MJ, White GL, Moore DL. Association of relative backpack weight with reported pain, pain sites, medical utilization, and lost school time in children and adolescents. J Sch Health. 2007;77(5):232–239. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00198.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jones GT, Watson KD, Silman AJ, et al. Predictors of low back pain in British schoolchildren: a population-based prospective cohort study. Pediatrics. 2003;111:822–828. doi: 10.1542/peds.111.4.822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Costa-Black KM, Loisel P, Anema JR, et al. Back pain and work. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:227–240. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maniakis A, Gray A. The economic burden of back pain in the UK. Pain. 2000;84:95–103. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00187-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cardon G, Balague F. Low back pain prevention’s effects in schoolchildren. What is the evidence? Eur Spine J. 2004;13:663–679. doi: 10.1007/s00586-004-0749-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Forjuoh SN, Little D, Schuchmann JA, et al. Parental knowledge of school backpack weight and contents. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:18–19. doi: 10.1136/adc.88.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]