ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE

Physicians are mandated to offer treatment choices to patients, yet not all patients may want the responsibility that entails. We evaluated predisposing factors for, and long-term consequences of, too much and not enough perceived decision-making responsibility among breast cancer patients.

DESIGN

Longitudinal assessment, with measurements collected just after surgical treatment (baseline) and 6-month follow-up.

PARTICIPANTS

Women with early-stage breast cancer treated surgically at eight NYC hospitals, recruited for a randomized controlled trial of patient assistance to improve receipt of adjuvant treatment.

MEASUREMENTS

Using logistic regression, we explored multivariable-adjusted associations between perceived treatment decision-making responsibility and a) baseline knowledge of treatment benefit and b) 6-month decision regret.

RESULTS

Of 368 women aged 28–89 years, 72 % reported a “reasonable amount”, 21 % “too much”, and 7 % “not enough” responsibility for treatment decision-making at baseline. Health literacy problems were most common among those with “not enough” (68 %) and “too much” responsibility (62 %). Only 29 % of women had knowledge of treatment benefits; 40 % experienced 6-month decision regret. In multivariable analysis, women reporting “too much” vs. “reasonable amount” of responsibility had less treatment knowledge ([OR] = 0.44, [95 % CI] = 0.20–0.99; model c = 0.7343;p < 0.01) and more decision regret ([OR] = 2.,91 [95 % CI] = 1.40–6.06; model c = 0.7937;p < 0.001). Findings were similar for women reporting “not enough” responsibility, though not statistically significant.

CONCLUSION

Too much perceived responsibility for breast cancer treatment decisions was associated with poor baseline treatment knowledge and 6-month decision regret. Health literacy problems were common, suggesting that health care professionals find alternative ways to communicate with low health literacy patients, enabling them to assume the desired amount of decision-making responsibility, thereby reducing decision regret.

KEY WORDS: breast cancer, treatment decision-making, treatment knowledge, decision regret, health literacy

BACKGROUND

Physicians are mandated to offer treatment choices to breast cancer patients,1 and for many women, greater involvement in, or responsibility for cancer treatment decisions can improve knowledge of treatment benefits, enhance decision satisfaction and improve quality of life.2–4 Prior studies show that breast cancer patients who feel they are not given enough responsibility for treatment decision-making have poorer treatment knowledge, and report lower satisfaction and worse quality of life.2–4 However, not all women want to take more responsibility for their cancer treatment decisions,5,6 and may feel overwhelmed, distressed or anxious immediately following their diagnosis,7,8 leaving them ill-prepared to handle the choices they are given. One study has documented cross-sectional associations between both higher and lower than preferred level of decision-making and decision regret.9 However, to our knowledge no studies have examined longer-term consequences.

To enhance our understanding of the characteristics of, and consequences for, women who feel they have more decision-making responsibility than preferred, we explored the associations between breast cancer patients’ perceived degree of responsibility for treatment decision-making and a) knowledge of the benefit of surgical and adjuvant treatments discussed with one’s physician and b) regret of decisions after 6 months. Treatment knowledge and decision regret are important metrics, as insufficient knowledge of treatment benefit has been associated with non-use and early discontinuation of breast cancer treatments in prior research,10–12 and decision regret is itself a negative emotion and adverse psychological event.13 We also explored how sociodemographic, clinical and other factors (health literacy, self-efficacy, trust in physician, communication with physician) were associated with perceived degree of responsibility for treatment decision-making. Identifying modifiable factors associated with patients’ perceived responsibility for decision-making may help to shape interventions to improve treatment knowledge and reduce future decision regret.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

Participants for this descriptive study included women enrolled in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) evaluating the effect of patient-assistance programs on receipt of adjuvant therapies among minority and non-minority women recently operated on for early stage breast cancer. Women were identified from pathology reports and recruited from eight New York City hospitals, including four tertiary referral centers and four municipal hospitals between October 2006 and August 2009. If women had undergone definitive surgical treatment for a new, primary stage I or II breast cancer at one of the participating sites, and were candidates for adjuvant treatment, they were eligible for inclusion in the trial. In addition, women had to speak English or Spanish, and their surgeon had to provide consent before they could be contacted. Women were considered ineligible if they had received neo-adjuvant therapy, were not capable of consent, had a poor prognosis (i.e. serious health condition likely to impact breast cancer treatment or long-term survival), or were not consented within 6 months after their definitive surgery. Institutional review board (IRB) approval was obtained from all participating sites.

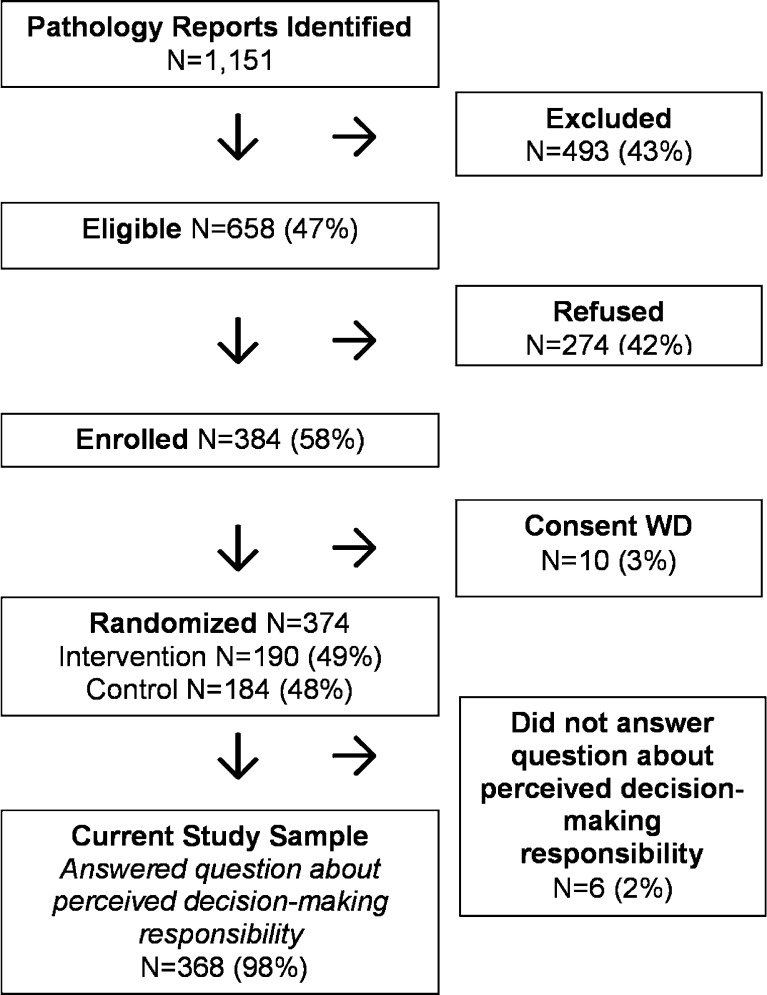

A total of 374 women were enrolled in the original RCT (see Fig. 1 for eligibility/exclusions). RCT results will be published in a separate paper. Our analysis included the 368 women from the RCT who provided information on perceived degree of responsibility for treatment decision-making at baseline. Baseline surveys were conducted after women underwent surgical treatment and had met with an oncologist to discuss adjuvant treatment options. Spanish-speaking women were interviewed in Spanish by trained bilingual interviewers. Surveys were translated into Spanish and back-translated into English to ensure consistency across language. A total of 327 women also completed a 6-month follow-up telephone interview and were considered for the analysis of 6-month decision regret. Trained study interviewers also performed follow-up telephone interviews.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of enrollment/exclusions for study population.

Measurements

Baseline telephone surveys assessed women’s perceived responsibility for treatment decision-making, self-efficacy (e.g. comfort voicing concerns to physician), health literacy, trust in and communication with physician, and knowledge about the benefits of breast cancer treatments they had discussed with their physician. Women were then surveyed 6 months after baseline to assess decision regret.

The independent variable of interest, measured at baseline, was perceived degree of responsibility for making decisions about breast cancer treatment; “How much responsibility for making treatment decisions did you have?” (“not enough”, a “reasonable amount”, “too much”).

Dependent variables included a) treatment knowledge measured at baseline, and b) regret of decisions measured at 6-month follow-up. Adequate treatment knowledge was defined as answering the following questions correctly: “A woman can have a mastectomy or have a lumpectomy with radiation. Which treatment do you think is more likely to keep the cancer from coming back?” (correct answer = mastectomy);14 for those who discussed chemotherapy with their physician, “Do you believe that chemotherapy makes it less likely for the cancer to come back?” (correct answer = yes); and for those who discussed hormone therapy with their physician, “Do you believe that hormonal treatment makes it less likely for the cancer to come back?” (correct answer = yes). Surgical knowledge alone was considered adequate for women who had not discussed chemotherapy or hormonal treatments with their physician. Decision regret at 6 months was measured with the following question: “If I had to do it over, I would make a different decision about breast cancer treatment”. Original response categories included: “strongly agree”, “somewhat agree”, “neither agree nor disagree”, “somewhat disagree”, “strongly disagree”. We considered those who “strongly disagreed” to have no decision regret, while we considered those who “less than strongly disagreed” to have decision regret.

Covariates of interest measured at baseline included age, race/ethnicity, marital status, income, education, health insurance and stage at diagnosis. Health literacy was measured with a single item assessing frequency of problems understanding written information about one’s medical condition. Original response categories included: never, occasionally, sometimes, often, and always. We dichotomized responses (“never” vs. “occasionally /more frequently”). A single item measured self-efficacy; “At the time of your breast cancer diagnosis in general when talking with doctors, how much would you say you spoke up for yourself and voiced your concerns?” Original response categories included: “none”, “a little bit”, “somewhat”, and “a great deal”. Responses were dichotomized (“a great deal” vs. “< a great deal”).

Using principal components factor analysis with orthogonal rotation to group similar items into scales, six items grouped together as a trust in physician scale (α = 0.71) (I am confident in my doctor’s judgment about my medical care; I can tell my doctor anything; My doctor sometimes pretends to know things when he is not sure; My doctor would always tell me the truth about my health; even if there was bad news; My doctor is well qualified to manage medical problems like mine; How much do you trust your doctor (on a scale of 1–10)?).15 Five other items grouped together as a physician communication scale (α = 0.82) (Your doctor gave you the information you needed to make a decision about your cancer treatment; Your doctor discussed different types or choice of treatment(s); Your doctor discussed the pros and cons of each choice with you; Your doctor explained what to expect during the treatment process; How much did your doctor ask you for your input or opinion about which treatment you preferred?).16 Questions with missing responses were imputed to the midpoint, and scales were recalibrated to a 100 point scale.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to profile the baseline sample (n = 368). Summary statistics were computed according to perceived degree of responsibility for treatment decision-making, comparing groups by age, race/ethnicity, income, education, and other covariates. We used chi-square tests for categorical variable comparisons, and t-tests for continuous variable comparisons. Key factors significantly associated with perceived responsibility for decision-making in bivariate analyses (p < 0.05) are highlighted in the Results.

To explore the association between perceived degree of treatment decision-making responsibility and a) baseline treatment knowledge and b) 6-month decision regret, we used logistic regression to model binary outcomes for each relationship. Odds ratios compare women with “too much” and “not enough” perceived decision-making responsibility to those with a “reasonable amount” of perceived responsibility, as the referent category. For each analysis, covariates included in adjusted models were those significantly associated with independent and dependent variables of interest in bivariate analysis.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Of 368 women aged 28–89 years enrolled at baseline, 45 % were White, 20 % Black, 31 % Hispanic and 5 % Asian/Pacific Islander/other (see Table 1). Seventy-eight percent had a high school education or higher; 28 % earned < $15,000/year. Fifty-two percent of women had commercial insurance, while 26 % were uninsured/covered by Medicaid. The majority completed interviews in English (77 %).

Table 1.

Description of Study Sample (N = 368)

| Patient demographic characteristics |

N = 368 n (%)* |

|---|---|

| Age (mean [range]) | 56.6 [28–89] |

| Age group | |

| < 50 years | 120 (32.6) |

| 50–64 years | 156 (42.4) |

| ≥ 65 years | 92 (25.0) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 72 (19.6) |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 164 (44.7) |

| Hispanic | 113 (30.8) |

| Asian/Pacific Islander/other | 18 (4.9) |

| Marital status | |

| Single, separated, divorced or widowed | 186 (51.5) |

| Married or living with a partner | 175 (48.5) |

| Annual household income | |

| Under $15,000 | 102 (28.0) |

| $15,000 to $50,000 | 72 (19.8) |

| $50,000–$100,000 | 51 (14.0) |

| Over $100,000 | 101 (27.8) |

| Refused | 38 (10.4) |

| Education | |

| < High school | 74 (21.5) |

| High school | 60 (17.4) |

| Some college | 49 (14.2) |

| College degree or beyond | 162 (46.9) |

| Type of health insurance | |

| Commercial | 185 (51.8) |

| Medicare | 80 (22.4) |

| Medicaid/no insurance | 92 (25.8) |

| Language of interview | |

| English | 280 (76.9) |

| Spanish | 84 (23.1) |

*Percentages based on non-missing values

Seventy-two percent of women reported a “reasonable amount”, 21 % “too much”, and 7 % “not enough” responsibility for treatment decision-making. These groups differed significantly (p < 0.05) with respect to race/ethnicity, household income, education, health insurance, health literacy, self-efficacy, trust in physician, and communication with physician (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Description of Sample (N = 368) by Degree of Responsibility for Decision-Making

| Reasonable amount 264 (72 %) n (%)* |

Not enough 26 (7 %) n (%)* |

Too much 78 (21 %) n (%)* |

p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age (mean [range]) | 56.1 [28–89] | 59.3 [32–85] | 57.5 [31–84] | 0.337 |

| Age group | ||||

| < 50 years | 88 (33.3) | 7 (26.9) | 25 (32.0) | 0.922 |

| 50–64 years | 110 (41.7) | 11 (42.3) | 35 (44.9) | |

| ≥ 65 years | 66 (25.0) | 8 (30.8) | 18 (23.1) | |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Black (non-Hispanic) | 57 (21.7) | 11 (42.3) | 4 (5.1) | < 0.001 |

| White (non-Hispanic) | 140 (53.2) | 6 (23.1) | 18 (23.1) | |

| Hispanic | 51 (19.4) | 9 (34.6) | 53 (67.9) | |

| Asian/Pacific Islander/other | 15 (5.7) | 0 | 3 (3.9) | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single, separated, divorced or widowed | 125 (48.6) | 18 (69.2) | 43 (55.1) | 0.104 |

| Married or living with a partner | 132 (51.4) | 8 (30.8) | 35 (44.9) | |

| Annual household income | ||||

| Under $15,000 | 54 (20.8) | 6 (23.1) | 42 (53.8) | < 0.001 |

| $15,000 to $50,000 | 50 (19.2) | 9 (34.6) | 13 (16.7) | |

| $50,000–$100,000 | 47 (18.1) | 0 | 4 (5.1) | |

| Over $100,000 | 85 (32.7) | 4 (15.4) | 12 (15.4) | |

| Refused | 24 (9.2) | 7 (26.9) | 7 (9.0) | |

| Education | ||||

| < High school | 37 (15.0) | 9 (39.1) | 28 (36.8) | < 0.001 |

| High school | 44 (17.9) | 1 (4.4) | 15 (19.7) | |

| Some college | 35 (14.2) | 4 (17.4) | 10 (13.2) | |

| College degree or beyond | 130 (52.9) | 9 (39.1) | 23 (30.3) | |

| Type of health insurance | ||||

| Commercial | 155 (61.0) | 10 (38.6) | 20 (26.0) | < 0.001 |

| Medicare | 59 (23.2) | 6 (23.1) | 15 (19.5) | |

| Medicaid/no insurance | 40 (15.8) | 10 (38.5) | 42 (54.5) | |

| Health-related characteristics | ||||

| Breast cancer stage | ||||

| Stage 1A–1B | 159 (60.2) | 13 (50.0) | 38 (48.7) | 0.148 |

| Stage 2A–2B | 105 (39.8) | 13 (50.0) | 40 (51.3) | |

| Health literacy: frequency of problems understanding written information about medical condition | ||||

| Never | 131 (50.2) | 8 (32.0) | 29 (37.7) | 0.050 |

| Occasionally or more frequently | 130 (49.8) | 17 (68.0) | 48 (62.3) | |

| Self-efficacy and experience with medical professionals | ||||

| Self-efficacy: degree of speaking up for oneself & voicing concerns | ||||

| A great deal | 162 (61.4) | 8 (30.8) | 50 (64.1) | 0.007 |

| Less than a great deal | 102 (38.6) | 18 (69.2) | 28 (35.9) | |

| Trust in physician scale [1–100] (mean ± sd) | 95.6 ± 7.4 | 88.9 ± 11.5 | 96.3 ± 6.9 | < 0.001 |

| Physician communication scale [1–100] (mean ± sd) | 88.1 ± 15.1 | 61.2 ± 23.9 | 91.4 ± 11.2 | < 0.001 |

| Treatment knowledge and decision regret | ||||

| Knowledge of treatment benefit | ||||

| Insufficient | 173 (66.5) | 20 (76.9) | 66 (84.6) | 0.007 |

| Sufficient | 87 (33.5) | 6 (23.1) | 12 (15.4) | |

| Decision regret at 6 months | ||||

| No regret | 161 (69.1) | 8 (36.4) | 23 (35.4) | < 0.001 |

| Any regret | 72 (30.9) | 14 (63.6) | 42 (64.6) | |

*Percentages based on non-missing values

The majority of women reporting a “reasonable amount” of responsibility were White (53 %), earned > $150,000/year (33 %), completed college (53 %), had commercial health insurance (61 %) and a great deal of self-efficacy (61 %). In contrast, the majority with “not enough” responsibility were Black (42 %), earned < $50,000/year (58 %), did not finish high school (39 %), did not have commercial insurance (62 %) and had low self-efficacy (69 %). The majority with “too much” responsibility were Hispanic (68 %), earned < $15,000/year (54 %), did not finish high school (37 %), and had Medicaid or no insurance (55 %), despite having a great deal of self-efficacy (64 %).

Health literacy problems were most common among women with “not enough” and “too much” responsibility for treatment decision-making (68 % and 62 % respectively) compared to women with a “reasonable amount” of responsibility (50 %). On average, women with low health literacy completed fewer years of education; only 33 % completed college compared to 63 % of women with no health literacy problems. In addition, a great deal of self-efficacy was most common among women with “too much” responsibility (64 %) as compared to women with “not enough” responsibility, who were least likely to voice their concerns (31 %).

Trust in physician was lowest among women with “not enough” responsibility (mean score = 89 ± 12); physician communication was poorest in this group as well (mean score = 61 ± 24). Overall, trust and communication scores were positively correlated with one another (ρ = 0.33), and mean scores for both trust and communication were similar between women with a “reasonable amount” and “too much” responsibility for treatment decision-making (see Table 2).

Both baseline knowledge of treatment benefit and 6-month decision regret were associated with perceived decision-making responsibility. Overall, 29 % of women had adequate knowledge of treatment benefit, and this percentage differed according to degree of responsibility for decision-making; 33 % of those reporting a “reasonable amount”, versus 23 % of those reporting “not enough” and 15 % of those reporting “too much” responsibility. Forty percent of women in the sample reported decision regret at 6 months, and this percentage also differed according to degree of treatment decision-making responsibility; 31 % of women reporting a “reasonable amount” of responsibility, versus 64 % of women reporting “not enough” and 65 % of women reporting “too much” responsibility (see Table 2).

Logistic Regression Analysis

Treatment Knowledge at Baseline

In multivariable analysis adjusted for age group, race/ethnicity, household income, education, health insurance, breast cancer stage, health literacy, self-efficacy and physician communication, women reporting “too much” responsibility for treatment decision-making were significantly less likely than those reporting a “reasonable amount” of responsibility to have adequate knowledge about the benefits of breast cancer treatment ([OR] = 0.44 [95 % CI] 0.20–0.99; model c = 0.7343, p < 0.01) (see Table 3). Women reporting “not enough” responsibility were also less likely to have adequate treatment knowledge, although in this small group, the result was not statistically significant ([OR] = 0.73 [95 % CI] 0.22–2.47).

Table 3.

Multivariable-Adjusted Analysis

| Treatment knowledge (baseline) (n = 328)* adjusted OR† | Decision regret (6 months) (n = 291)* adjusted OR‡ | |

|---|---|---|

| Degree of responsibility for treatment decision-making | ||

| Reasonable amount | Ref | Ref |

| Not enough | 0.73 (0.22, 2.47) | 2.82 (0.77, 10.3) |

| Too much | 0.44 (0.20, 0.99) | 2.91 (1.40, 6.06) |

*Includes total number of participants with non-missing values for all covariates included in model

†Adjusted for age group, race/ethnicity, marital status, household income, education, insurance type, stage, health literacy, self-efficacy, physician communication, RCT group; model c-statistic = 0.7343, p < 0.01

‡Adjusted for intervention group, race/ethnicity, household income, education, insurance type, trust in MD, health literacy, self-efficacy, physician communication , RCT group; model c-statistic =0.7937, p < 0.001

Decision Regret at 6 Months

Women reporting “too much” responsibility for treatment decision-making were significantly more likely than those reporting a “reasonable amount” of responsibility to express decision regret at 6 months ([OR] = 2.91 [95 % CI] 1.40–6.06; model c = 0.7937 p < 0.001), after adjusting for race/ethnicity, household income, education, health insurance, trust in physician, health literacy, self-efficacy, and physician communication (see Table 3). Women reporting “not enough” responsibility were also more likely to express decision regret. The result was not statistically significant ([OR] = 2.82 [95 % CI] 0.77–10.3).

DISCUSSION

Healthcare mandates are often created with an ideal, clear purpose in mind, but when implemented across a variety of diverse practices and populations, unintended consequences may appear. Few would argue with the importance of informing patients about necessary treatments for breast cancer, or the importance of enabling choice about equivalent treatment options. However, in reality, not all patients are uniformly equipped or adequately prepared to make these treatment choices. Similarly, not all physicians are equipped to tailor informational approaches across a diverse population of patients who may approach complex decision-making in very different ways. Despite these key variabilities, physicians are mandated to offer treatment choices to their patients in an era of patient-centered care.1

It is well-established that many women wish to be actively involved in cancer treatment decisions,17,18 and greater involvement among those who desire it can improve knowledge of cancer treatment benefits and enhance decision satisfaction and quality of life among breast cancer patients.2–4 However, our results show that 21 % of women felt they had “too much” treatment decision-making responsibility. Some women may feel overwhelmed or burdened by treatment choices,19,20 particularly if they are not also given the tools to understand and weigh the benefits and harms of these choices.7,8,21

Despite the recognition that such a group of women exists, prior work has largely overlooked potential negative experiences of women who express having “too much” treatment decision-making responsibility. While one other study also reported that having more involvement in treatment decision-making than preferred was associated with decision regret,9 the analysis was cross-sectional, making determination of causality impossible. In contrast, our study incorporated a longitudinal design, and demonstrated a lasting consequence of having “too much” perceived treatment decision-making responsibility—the persistence of decision regret after 6 months.

Several key differences among women according to perceived degree of decision-making responsibility are worth noting. The majority of women reporting “too much” responsibility were Hispanic, compared to those reporting “not enough” responsibility, who were primarily Black, and those reporting a “reasonable amount” of responsibility, who were primarily White. These differences in preferred degree of responsibility by race/ethnicity may reflect underlying cultural differences. Historically, trust of medical professionals has been an issue among Black patients.22,23 Patients with limited trust in their physicians may wish to be more involved in their own treatment decisions as a result of this mistrust. Trust-in-physician scores were in fact lowest among women reporting “not enough” responsibility for decision-making, many of whom were Black. In contrast, Hispanic/Latina women may prefer for their physicians to make most of the decisions about treatment,24–26 and may be more prone to feeling they have “too much” responsibility in the face of complex decisions.

Health literacy and education were also strongly linked to women’s sense of responsibility for treatment decision-making in our analysis, suggesting that patients’ health literacy could be used to guide physicians’ discussions of breast cancer treatment. Women who perceived their degree of decision-making responsibility as either “too much” or “not enough” had low levels of health literacy and education, despite variation in self-efficacy and physician communication scores. Improving patient knowledge about cancer treatments can enable patients to become more engaged in their own treatment decisions, resulting in improved satisfaction with treatment outcomes.7,27–30

A great deal of self-efficacy, the tendency to voice concerns, was most common among women reporting “too much” responsibility. Conversely, women reporting “not enough” responsibility, were least likely to voice their concerns. These findings suggest that physicians may require alternative strategies or tools to accurately assess how much responsibility women want, especially for those who may not be the most assertive or talkative with their physicians. Adding to their burden, we observed poor health literacy and poor physician communication in the group of women reporting “not enough” responsibility, which, when combined with low self-efficacy, is likely to leave women ill-prepared to make complex decisions about cancer treatment, despite their desire to be involved.

Of equal concern is the finding that women who felt they had “too much” decision-making responsibility expressed this sentiment, despite reporting a great deal of self-efficacy. This suggests that even among women with a high degree of self-efficacy and high degree of physician communication, without adequate health literacy, information communicated by physicians may be poorly understood,5 leaving these women ill-prepared to take control over treatment decisions.

In the current era of patient-centered care, by finding ways to tailor communication to low health literacy patients, physicians can equip patients with better knowledge and understanding of treatment choices to enable women to want to take more responsibility for their treatment decisions. While tailoring communication during the treatment decision-making process represents a formidable challenge for breast cancer physicians, doing so may help improve patients’ knowledge of treatment benefits and reduce future decision regret.

Existing breast cancer decision-aid tools have been shown to improve patient knowledge, enabling patients to take a more active role in their own treatment decisions, and resulting in improved satisfaction with treatment outcomes.7,27–30 Better integration of such tools into practice could help breast cancer physicians, general practitioners, clinical staff and patient educators working with breast cancer patients to tailor their communication about treatment options to patients with varying levels of health literacy.

Some important limitations to our study deserve mention. The overall sample was small, and only 27 women comprised the group indicating “not enough” treatment decision-making responsibility. Perhaps as a result, we did not observe statistically significant findings in this group of women. In addition, women were recruited from eight NYC hospitals, which may not be representative of other hospitals in the U.S. Finally, women who declined to participate may have differed from participants.

CONCLUSIONS

Poor treatment knowledge at baseline and experience of 6-month decision regret was common among breast cancer patients, particularly among women who felt they had “too much” responsibility for making their cancer treatment decisions. Few would argue against the need for women to be informed of their treatment options. However, we must pay attention to those who are likely to feel unduly burdened by this responsibility. As health care professionals, we must equip all women with better decision-making tools upfront, so they can become better-informed about treatment options and more comfortable with the responsibility for making these complex decisions. By finding alternative ways to communicate with low health literacy breast cancer patients, we can aim to improve knowledge of treatment benefit and reduce long-term decision regret.

Acknowledgements

Funding Source

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA107051).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Epstein RM, Street RLJ. Patient-Centered Communication in Cancer Care: Promoting Healing and Reducing Suffering. Bethesda: National Cancer Institute; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hack TF, et al. Do patients benefit from participating in medical decision making? Longitudinal follow-up of women with breast cancer. Psychooncology. 2006;15(1):9–19. doi: 10.1002/pon.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moyer A, Salovey P. Patient participation in treatment decision making and the psychological consequences of breast cancer surgery. Womens Health. 1998;4(2):103–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaston CM, Mitchell G. Information giving and decision-making in patients with advanced cancer: a systematic review. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(10):2252–64. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hawley ST, et al. Factors associated with patient involvement in surgical treatment decision making for breast cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65(3):387–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz SJ, et al. Patient involvement in surgery treatment decisions for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(24):5526–33. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gustafson DH, et al. CHESS: a computer-based system for providing information, referrals, decision support and social support to people facing medical and other health-related crises. Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care. 1992;161–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Hegel MT, et al. Distress, psychiatric syndromes, and impairment of function in women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. Cancer. 2006;107(12):2924–31. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lantz PM, et al. Satisfaction with surgery outcomes and the decision process in a population-based sample of women with breast cancer. Health Serv Res. 2005;40(3):745–67. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bickell NA, et al. Underuse of breast cancer adjuvant treatment: patient knowledge, beliefs, and medical mistrust. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(31):5160–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.9773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lash TL, et al. Adherence to tamoxifen over the five-year course. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;99(2):215–20. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9193-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Oates DJ, Silliman RA. Health literacy: improving patient understanding. Oncology (Williston Park) 2009;23(4):376–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brehaut JC, et al. Validation of a decision regret scale. Med Decis Making. 2003;23(4):281–92. doi: 10.1177/0272989X03256005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Veronesi U, et al. Twenty-year follow-up of a randomized study comparing breast-conserving surgery with radical mastectomy for early breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(16):1227–32. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Safran DG, et al. Linking primary care performance to outcomes of care. J Fam Pract. 1998;47(3):213–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heisler M, et al. The relative importance of physician communication, participatory decision making, and patient understanding in diabetes self-management. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(4):243–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.10905.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stacey D, Paquet L, Samant R. Exploring cancer treatment decision-making by patients: a descriptive study. Curr Oncol. 2010;17(4):85–93. doi: 10.3747/co.v17i4.527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tariman JD, et al. Preferred and actual participation roles during health care decision making in persons with cancer: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2010;21(6):1145–51. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hubbard G, Kidd L, Donaghy E. Preferences for involvement in treatment decision making of patients with cancer: a review of the literature. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(4):299–318. doi: 10.1016/j.ejon.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh JA, et al. Preferred roles in treatment decision making among patients with cancer: a pooled analysis of studies using the Control Preferences Scale. Am J Manag Care. 2010;16(9):688–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fagerlin A, et al. An informed decision? Breast cancer patients and their knowledge about treatment. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64(1–3):303–12. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Scharff DP, et al. More than Tuskegee: understanding mistrust about research participation. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(3):879–97. doi: 10.1353/hpu.0.0323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerend MA, Pai M. Social determinants of Black–White disparities in breast cancer mortality: a review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17(11):2913–23. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ashing-Giwa KT, et al. Understanding the breast cancer experience of Latina women. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2006;24(3):19–52. doi: 10.1300/J077v24n03_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Buki LP, et al. Latina breast cancer survivors’ lived experiences: diagnosis, treatment, and beyond. Cult Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2008;14(2):163–7. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.14.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Napoles-Springer AM, et al. Information exchange and decision making in the treatment of Latina and white women with ductal carcinoma in situ. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2007;25(4):19–36. doi: 10.1300/J077v25n04_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gustafson DH, et al. Effect of computer support on younger women with breast cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(7):435–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gustafson DH, et al. CHESS: 10 years of research and development in consumer health informatics for broad populations, including the underserved. Int J Med Inform. 2002;65(3):169–77. doi: 10.1016/S1386-5056(02)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molenaar S, et al. Decision support for patients with early-stage breast cancer: effects of an interactive breast cancer CDROM on treatment decision, satisfaction, and quality of life. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(6):1676–87. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2001.19.6.1676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sepucha K, Belkora J. Importance of decision quality in breast cancer care. Psicooncologia. 2010;7(2–3):313–28. [Google Scholar]