ABSTRACT

The clinical breast exam (CBE) is an important tool in the care of women. However, the utility of the screening CBE has been called into question. This article discusses the importance of the CBE as a physical diagnosis tool. Recommendations regarding screening with CBE are reviewed, and evidence surrounding breast cancer screening using CBE is briefly summarized. Clinicians should strive to provide high quality CBEs as part of the general clinical exam for women, particularly those who present with breast complaints, and for patients who choose to have CBE screening. In conclusion, there is a role for the CBE in the care of women, and clinicians should be proficient at performing these exams. Simulation teaching technologies are now available at Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) facilities to enable clinicians to improve their CBE skills.

KEY WORDS: clinical breast exam, women’s health, medical education, simulation

The clinical breast exam (CBE) is an important tool in the care of women. It is utilized for the evaluation of breast complaints and, more controversially, in breast cancer screening. The Department of Veteran Affairs (VA) Women’s Health Services Office has recently coordinated the distribution of breast exam simulation equipment to VA facilities in order to enhance CBE competency training for VA providers. Since the utility of the screening CBE has been called into question,1 the issue may be raised as to whether this training is pertinent. The following summary will provide rationale that the CBE is an important physical diagnosis skill that should not be discarded, and that simulation equipment is a helpful tool in training clinicians.

Clearly, the CBE is required for the evaluation of patients with breast complaints, particularly those with a breast lump. In one study of primary care clinics, 11 % of women complaining of a breast lump and 4 % of women with any breast complaint were found to have a malignancy.2 In addition, a significant number of patients with breast cancer present with a palpable breast mass. Haakinson et al.3 reported that 34 % of women with invasive breast cancer initially presented with a palpable lesion. 13 % of the women with a palpable breast mass who were found to have invasive cancer had a normal mammogram within the previous year. Likewise, a large study of diagnostic mammograms reported that the sensitivity of mammography in women with a self-reported breast lump was 87.3 %.4 This suggests that approximately 13 % of clinically evident breast cancers may be missed by mammography imaging. Therefore, identifying these tumors by palpation is a pertinent clinical issue, and providers should be proficient at discerning abnormal breast findings.

The more divisive issue is whether the clinical breast exam should be used in conjunction with mammography for breast cancer screening in asymptomatic patients. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) states that there is insufficient evidence to recommend for or against routine screening with the CBE.1 However, the American Cancer Society5 and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists6 recommend offering periodic CBE screening every 1–3 years for women ages 20–40 years, and annually in conjunction with mammography for women over the age of 40. This discrepancy between USPSTF guidelines and those of other groups may leave clinicians confused regarding the utility of the screening CBE.

Randomized trials demonstrating decreased mortality from CBE alone are lacking. However, screening CBE is supported by indirect evidence from studies in which a breast exam was included with mammography in breast cancer screening. A meta-analysis demonstrated that CBE contributed to cancer detection independently from mammography, with sensitivity and specificity of CBE estimated at 54 % and 94 %, respectively.7 It should be noted that this calculation was based on pooled data in which the method of CBE varied from study to study. In community based studies, without the implementation of standard breast exam guidelines, CBE detected about 5 % of cancers that were not visible on mammography.8 The Canadian National Breast Cancer Study-2 investigated the effects of mammography alone compared to careful standardized clinical breast examination plus mammography, and found that breast cancer mortality was the same in both groups after 13 years of follow-up.9

Cancers revealed by CBE are more aggressive compared to those found on mammogram. Ma et al. demonstrated that cancers detected by SBE (self breast exam) and CBE were “larger tumors (2.4 cm vs. 1.3 cm), higher grade, more frequently ER- (29 % vs. 16 %), triple-negative (21 % vs. 10 %), and lymph node-positive (39 % vs. 18 %); all P ≤ 0.01”.10 Interestingly, 17 % of the women with palpable malignant tumors had negative screening mammography within the past year.10 Since cancers detected by CBE in patients with negative mammograms tend to be biologically more aggressive, this may negatively bias measurements of the effect of CBE on mortality. Similarly, lead-time bias may cause overestimation of the effect.11

Mammography is less sensitive in women under 35, due to denser breast tissue.12 Therefore, CBE may be particularly important in the evaluation of younger women who undergo screening or who present with breast complaints. VA based providers should be aware of this, because of the growing population of younger women veterans.

CBE alone has been suggested as a screening method in countries with limited financial resources.13 A simulation study of breast cancer in India estimated that the cost of one mammogram is 3.34 times higher than that of one CBE. The same study also estimated that annual CBE achieves nearly the same number of life-years saved as biennial mammography, but at approximately half the cost.14 A cluster randomized controlled trial is on-going in India, comparing no screening to CBE performed by female health workers who were trained on silicone models. Preliminary results reveal more early stage breast cancers diagnosed in the screening group. The sensitivity and specificity of CBE was calculated at 51.7 % and 94.3 %, respectively,15 which is consistent with that in other studies.7 It is not yet known whether diagnosing these cancers will change outcomes. Mortality data will be forthcoming.

Although there is improved identification of early stage breast cancers with screening CBE, clinicians must consider the potential benefit versus harm. There is little data evaluating the harms of CBE screening. Theoretical concerns include the potential for false positive results that may lead to anxiety, as well as unnecessary imaging and procedures.1 A Canadian cohort study revealed that sensitivity for cancer detection was better in patients that had both mammography and CBE; however, there were more false positives in the CBE group. Their analysis revealed that for each additional cancer detected by CBE per 10,000 women, there would be 55 additional false positives.16

Likewise, over-diagnosis due to positive findings may lead to unwarranted treatment in patients with breast cancer that would never become clinically significant. The impact of over-diagnosis related to false positive CBE is not known. It is estimated that approximately 15–25 % percent of cancers identified by mammography are overdiagnosed.17 The false positive rate is lower with CBE than with mammography,18 so it is likely that over-diagnosis would be less frequent. This may cause some to consider CBE as an alternative to mammography screening.

Patients are commonly informed of the benefits of breast cancer screening, but potential harms are not routinely mentioned. Women indicate that they desire to be actively involved in decision-making regarding medical testing related to breast health;19 however, physicians report that they often do not discuss breast cancer screening methods with their patients.20 Discomfort during exam and the patient’s perception of efficacy of CBE have been reported as factors that deter some women from adherence to screening CBE.21 Discussing the fact that mammogram screening is not perfect and that some tumors may not be detected on mammography may convince more women to be compliant with screening CBE. Likewise, patients that do not desire mammography or do not follow-up for mammogram imaging may be even more likely to benefit from periodic CBE.

In addition to education on benefits of breast cancer screening methods, all women should be informed of potential harms of screening, including false positives and potential over-diagnosis. Improved tools for counseling patients on the benefits/risks of CBE and mammogram screening also need to be developed. In the developing era of patient-centered care, it will be important to have careful conversations with women regarding their preferences involving screening modalities.

Clinicians should be proficient at performing breast exams for patients who present with breast complaints and for women who choose to have CBE screening. Competency varies widely among clinicians that do breast exams. Using proper technique and spending an adequate amount of time are key factors when assessing physician accuracy in detecting abnormal lumps in silicone breast models.7 A careful exam should take approximately 3 min for the average size breast. Breast palpation should be performed with the pads of the fingers in circular motions. Each area of the breast should be palpated using three different pressures (light, medium and deep). The best coverage of breast tissue occurs by examining the breast in vertical strips beginning at the axilla and extending down the mid-axillary line to the bra line, then moving medially in rows to the center of the chest.22

Ideal educational modalities include simulation training along with exposure to patients. Trainees that participated in a structured CBE curriculum (including didactic, simulation practice and standardized patients) were more proficient at identifying abnormal breast findings in silicone models than those that did not receive training. However, false positive rates were no higher in the training group.23 Similarly, comfort level improved when students were trained on silicone breast models,24 and medical students who learned how to perform CBE on breast palpation simulators performed as well or better than those who learned using the more costly standardized patients.25 Future research needs to evaluate outcomes of simulation training, including applicability to human subjects.

The VA Women’s Health Services Office strives to improve the ability of providers to deliver quality care to women veterans. Training by simulation technology coupled with the instruction of experienced clinicians is an important tool in achieving this goal. Each Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) distributes simulation models in cooperation with the Designated Learning Officer at local facilities. The following breast simulation task trainers are now available to VA providers:

Kyoto breast task trainer:26 This visual-tactile breast simulator model allows training in differentiation of four typical breast lumps, including a cancer with dimple sign (Fig. 1). Palpable clavicle and ribs are also embedded under the soft breast tissue. The compact size (20 × 28 × 15H cm, 2 kg) allows for convenient storage and transport.

Gaumard breast task trainer:27 A task trainer with left and right breasts attached to an adult upper torso provides realistic breast exam training (Fig. 2). The left breast provides pathologies for breast self examination (BSE) training, while the right breast provides pathologies for CBE training. This model replicates life-like examination. However, the larger, heavier size makes it less convenient to transport and store.

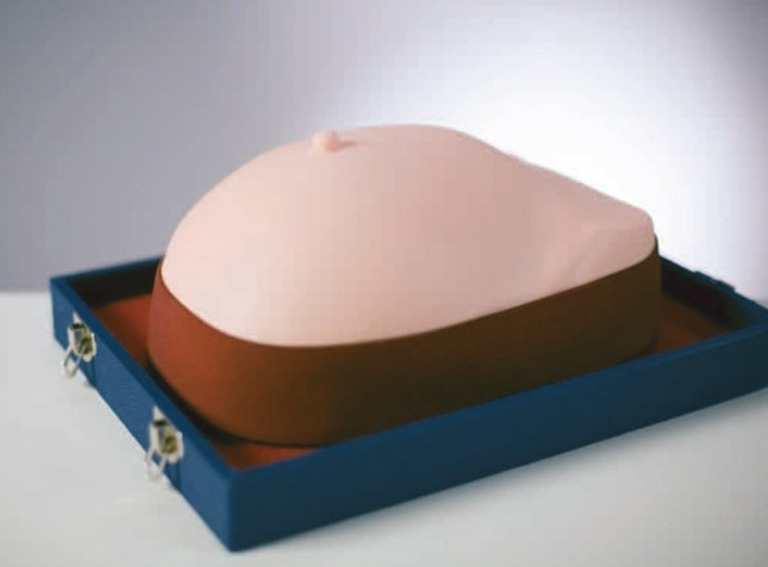

MammaCare CBE simulation training28 (includes laptop computer and four breast models): Developed with the support of the National Cancer Institute and the National Science Foundation, this program is a self-directed software based course that emulates breast exam protocols (Fig. 3). A breast model is placed on a Palpation Training and Assessment Device, which is linked to a laptop computer. Learners are led through a series of training modules aimed at improving the ability to detect abnormal findings and providing complete coverage of the breast. Participants receive immediate feedback via computer screen and speakers as they proceed through the program. This allows the advantage of self-directed learning without a preceptor present during the entire session. Disadvantages include higher cost and the need for instructors trained in the MammaCare technology.

Figure 1.

Kyoto breast task trainer.

Figure 2.

Gaumard breast task trainer.

Figure 3.

Mammacare clinical breast exam (CBE) simulation training.

In addition to use in the training of students and residents, simulation models may be a cost-effective means of providing training to clinicians and allied health workers that do not have access to more structured CME activities, such as those in rural areas.

Although the issue of CBE for breast cancer screening is likely to remain controversial, all would agree that the breast exam is useful in evaluating women who present with breast complaints. Providers championing quality care for women veterans need to be skilled in assessing patients regarding breast health, and simulation training may be a helpful tool in achieving this goal.

In conclusion, there remains a role for the CBE in the care of women and clinicians should be proficient at performing high quality exams. VA clinicians who desire to utilize simulation task trainers should contact the Women Veteran’s Program Manager or Designated Learning Officer at their facility. They may also participate in simulation training at VA-sponsored Women’s Health Mini-Residency Courses.

Acknowledgments

Conflict of Interest

The authors are not affiliated with any CBE simulation products. They have no acknowledgement or funding sources to disclose. The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Veterans Health Administration.

Contributor Information

Teresa Bryan, Phone: +1-205-9343007, FAX: +1-205-9757797, Email: Teresa.bryan@va.gov, Email: tbc500@uab.edu.

Erin Snyder, Email: esnyder@uab.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Preventive US. Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151(10):716–726. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-10-200911170-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barton MB, Elmore JG, Fletcher SW. Breast symptoms among women enrolled in a health maintenance organization: frequency, evaluation, and outcome. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(8):651–657. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-8-199904200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Haakinson DJ, Stucky CH, Dueck AC, et al. A significant number of women present with palpable breast cancer even with a normal mammogram within 1 year. Am J Surg. 2010;200(6):712–717. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2010.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barlow WE, Lehman CD, Zheng Y, et al. Performance of diagnostic mammography for women with signs or symptoms of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(15):1151–1159. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.15.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith RA, Cokkinides V, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2012: a review of current American cancer society guidelines and issues in cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62(2):129–142. doi: 10.3322/caac.20143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.The American College of Obstetricians-Gynecologists Practice bulletin no. 122: breast cancer screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:372–382. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31822c98e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barton MB, Harris R, Fletcher SW. Does this patient have breast cancer? The screening clinical breast examination: should it be done? JAMA. 1999;282(13):1270–1280. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.13.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bobo JK, Lee NC, Thames SF. Findings from 752,081 clinical breast examinations reported to a national screening program from 1995 through 1998. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(12):971–976. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.12.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller AB, To T, Baines CJ, Wall C. Canadian National Breast Screening Study-2: 13-year results of a randomized trial in women aged 50–59 years. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92(18):1490–1499. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.18.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ma I, Dueck A, Gray R, et al. Clinical and self breast examination remain important in the era of modern screening. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;5:1484–1490. doi: 10.1245/s10434-011-2162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss NS. Breast cancer mortality in relation to clinical breast examination and breast self-examination. Breast J. 2003;9(Suppl 2):S86–S89. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.9.s2.9.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Checka CM, Chun JE, Schnabel FR, Lee J, Toth H. The Relationship of Mammographic Density and Age: Implications for Breast Cancer Screening. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012; 198(3):W292–5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Corbex M, Burton R, Sancho-Garnier H. Breast cancer early detection methods for low and middle income countries, a review of the evidence. Breast. 2012;21:428–434. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2012.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Okonkwo, Draisma G, Kinderen A, Brown ML, Koning H. Breast cancer screening policies in developing countries. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(18):1290–1300. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sankaranarayanan R, Ramadas K, Thara S, et al. Clinical breast examination: preliminary results from a cluster randomized controlled trial in India. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2011;103(19):1476–1480. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djr304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chiarelli AM, Majpruz V, Brown P, Thériault M, Shumak R, Mai V. The contribution of clinical breast examination to accuracy of breast screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(18):1236–1243. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalager M, Adami H, Bretthauer M, Tamimi RM. Overdiagnosis of invasive breast cancer due to mammogram screening: results from the Norwegian Screening Program. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(7):491–499. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-7-201204030-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elmore JG, Barton MB, Moceri VM, Polk S, Arena PJ, Fletcher SW. Ten-year risk of false positive screening mammograms and clinical breast examinations. N Eng J Med. 1998;338(16):1089–1096. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199804163381601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davey HM, Barratt AL, Davey E, Butow PN, et al. Medical tests: women’s reported and preferred decision-making roles and preferences for information on benefits, side-effects and false results. Health Expect. 2002;5(4):330–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2002.00194.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dunn AS, Shridharani KV, Lou W, Bernstein J, Horowitz CR. Physician-patient discussions of controversial cancer screening tests. Am J Prev Med. 2001;20(2):130–134. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(00)00288-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kurtz ME, Given B, Given CW, Kurtz JC. Relationships of barriers and facilitators to breast self-examination, mammography, and clinical breast examination in a worksite population. Cancer Nurs. 1993;16(4):251–259. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199308000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saslow D, Hannon J, Osuch J, et al. Clinical breast examination: practical recommendations for optimizing performance and reporting. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54(6):327–344. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.6.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Steiner E, Austin DF, Prouser NC. Detection and description of small breast masses by residents trained using a standardized clinical breast exam curriculum. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(2):129–134. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0444-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pugh CM, Salud LH. Fear of missing a lesion: use of simulated breast models to decrease student anxiety when learning clinical breast examinations. Am J Surg. 2007;193:766–770. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schubart JR, Erdahl L, Smith JS, Purichia H, Kauffman GL, Kass RB. Use of breast simulators compared with standardized patients in teaching the clinical breast examination to students. J Surg Educ. 2012;69(3):416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kyoto Kagaku Co., LTD. http://www.kyotokagaku.com/products/detail01/m44.html. Accessed January 1, 2013.

- 27.Gaumard-Simulators for Healthcare Education. http://www.gaumard.com/breast-examination-simulator-s230-42/ Accessed January 1, 2013.

- 28.MammaCare- Clinical Breast Exam Certification and Breast Self-Exam Teaching. http://www.mammacare.com/index.php. Accessed January 1, 2013.