Abstract

Purpose

Since 1999, in conjunction with the internationally known and award-winning Your Disease Risk (yourdiseaserisk.org) risk assessment tool, the “Eight Ways to Stay Healthy and Prevent Cancer” message campaign has provided an evidence-based, but user-friendly, approach to cancer prevention. The scientific evidence behind the campaign is robust and while not a complete list, provides a great deal of benefit in the reduction of cancer risk. With 12 million cancer survivors in the United States, there is a need for a parallel set of recommendations that oncologists and primary care providers may routinely use for individuals following a cancer diagnosis focused on improving the quantity and quality of life after diagnosis. With increasing survival rates and many cancer survivors dying from noncancer causes, survivorship care necessarily focuses on more than just risk of cancer recurrence and cancer-related mortality.

Methods

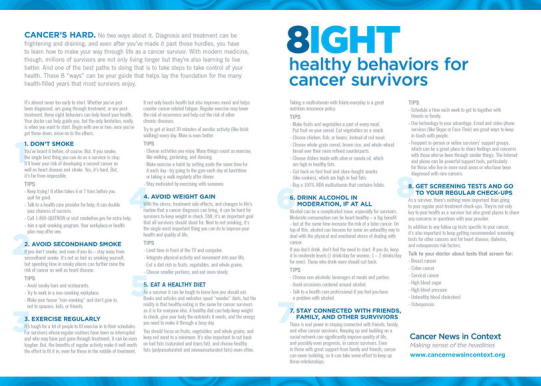

To provide a foundation for living a healthy life after a cancer diagnosis, we developed a set of evidence-based health messages for cancer survivors. “Cancer Survivors’ Eight Ways to Stay Healthy After Cancer,” published by the Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes Jewish Hospital, documents both the evidence supporting the recommendations as well as tips for implementing them.

Results

The one-line summary messages are: (1) don’t smoke, (2) avoid secondhand smoke, (3) exercise regularly, (4) avoid weight gain, (5) eat a healthy diet, (6) drink alcohol in moderation, if at all, (7) stay connected with friends, family, and other survivors, (8) get screening tests and go to your regular checkups.

Conclusions

The cancer survivors’ eight ways are the foundation for an evidence-based health promotion program for survivors.

Keywords: Lifestyle, Smoking, Obesity, Exercise, Diet, Survivorship

Since 1999, in conjunction with the internationally known and award-winning Your Disease Risk (yourdiseaserisk.org) risk assessment tool, the “Eight Ways to Stay Healthy and Prevent Cancer” message campaign has provided an evidence-based, but user-friendly approach to cancer prevention. The scientific evidence behind the campaign is robust and while not a complete list, provides a great deal of benefit in the reduction of cancer risk [1, 2].

With nearly 12 million cancer survivors in the United States [3], there is a need for a parallel set of recommendations that oncologists and primary care providers may routinely use for individuals following a cancer diagnosis, focused on improving the quantity and quality of life. Nearly, 65 %of cancer survivors live 5 or more years after diagnosis and 5-year survival rates exceed 95 %for two of the most common cancers, breast and prostate [3]. Survivors are at increased risk for second malignancies, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and osteoporosis [4–7]. Furthermore, cancer survivors die from noncancer causes [1, 4, 5, 8]. Thus, survivorship care necessarily focuses on more than just risk of cancer recurrence and cancer-related mortality and functional limitations [1, 5]. Data suggest that the majority of cancer survivors have at least one comorbid condition [1, 3, 9–12]. Despite the evidence for the benefits of maintaining a healthy lifestyle after a cancer diagnosis, only 20 % of oncologists provide guidelines on lifestyle issues [3–7, 9, 13]. Cancer survivors are also subject to long-term and late effects of treatment and diminished quality of life. The cancer survivors’ eight ways provides a foundation for living a healthy life after a cancer diagnosis.

“Cancer Survivors’ Eight Ways to Stay Healthy After Cancer” (Fig. 1), published by the Siteman Cancer Center at Washington University School of Medicine and Barnes Jewish Hospital, documents both the evidence supporting the recommendations as well as tips for implementing them. Successful implementation of survivorship programming is necessary to improve patient outcomes [3–7, 13, 14]. The one-line summary messages are as follows:

Don’t smoke

Avoid secondhand smoke

Exercise regularly

Avoid weight gain

Eat a healthy diet

Drink alcohol in moderation, if at all

Stay connected with friends, family, and other survivors

Get screening tests and go to your regular check-ups.

Fig. 1.

Cancer Survivors’ Eight Ways to Stay Healthy After Cancer. Educational materials from the Siteman Cancer Center at Barnes Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine. Available at www.cancernewsincontext.org

The messages contained in the review were developed by the authors, building on our epidemiologic, behavioral medicine and health communication expertise and our previous work in cancer prevention and based on our review of the epidemiologic and behavioral medicine literature in cancer survivorship. As this was not a scientific document, a formal systematic literature review was not done. During the course of developing the guidelines and brochure, two authors (GAC, KYW) presented the guidelines at several community-based events, and this feedback was used to make minor modifications to the language used. The published brochures are available in Siteman Cancer Center clinic and patient education areas across institution locations, and the content is also available on the institution website. As such, patients can access it at numerous points in their care, including at diagnosis, during treatment or during posttreatment follow-up and surveillance visits. A formal evaluation of patient or provider perceptions has yet to be conducted.

Here, we review the evidence base behind the cancer survivor’s eight ways. (For the purposes of our report, we employ the National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship definition of survivor, from the point of diagnosis onward [4–8, 14, 15].) Figure 1 provides an action plan for implementing counseling recommendations. We also provide references to evidence-based interventions in survivor populations for the recommendations when available. The body of evidence specifically evaluating interventions in this population is rapidly expanding.

Don’t smoke

While the original eight ways for cancer prevention focused on the risks of developing cancer and mortality associated with smoking, cancer survivors are subject to their own set of smoking-related risks [4, 5, 8, 15–18]. Survivors who smoke have increased risk of mortality, recurrence, and second primary tumors [5, 16–22]. Smoking also increases treatment-related complication rates [19–24] and reduces quality of life among survivors [23–26]. Finally, smoking is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease, stroke, and osteoporosis [15, 25, 26], important comorbidities among cancer survivors.

Smoking cessation increases survival, lowers risk of new primary tumors and metastases, as well as tumor recurrence [15]. Cessation also improves treatment response and reduces treatment toxicities [15, 27].

Despite the harms associated with smoking among cancer survivors, the prevalence of smoking among survivors remains similar to that of the US general population and is higher among young adult survivors than older survivors [27–29] and may be higher than among their nonsurvivor peers [28–30]. Smoking rates among survivors vary by diagnosis [30–32].

Evidence does indicate that smoking cessation interventions in cancer survivors are successful [31–33]. Yet, the evidence of the harms, provision of clinical practice guidelines, and an ability to intervene have not led to regular provision of cessation counseling by providers [13, 33]. Interventions are not well disseminated or integrated into clinical care [13, 34], though some dissemination studies are underway [34, 35]. It is estimated that less than half of cancer centers have a designated tobacco treatment provider [35, 36].

Avoid secondhand smoke

Given the particular importance for survivors of remaining smoke-free, and the known associations of smoke-free homes with successful quitting, living (and working) in a smoke-free environment is key for survivor health. Data suggest that exposure to secondhand smoke significantly increases the odds of survivors of continuing to smoke and of reporting poor health regardless of their own smoking status [36, 37]. Secondhand smoke is also associated with increased risk of many chronic diseases, including heart disease and stroke [37, 38].

Exercise regularly

The 2010 American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) Exercise Guidelines for Cancer Survivors concluded that exercise is safe for cancer survivors during and after treatment [38, 39]. Exercise is associated with myriad benefits among survivors [39–42]. While high-quality observational data have shown exercise reduces risk of recurrence and mortality [38–43], a wealth of intervention trials have shown exercise has more proximal benefits, including improving quality of life, reducing cancer-related fatigue, reducing depressive symptoms, and preventing or minimizing treatment-related side effects [38, 39, 43, 44]. Exercise also reduces risk of diabetes and heart disease [44]. For most cancer survivors, the ACSM guidelines parallel the US Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans [44, 45], advocating that, first and foremost, survivors avoid inactivity, progressing as tolerated to 150 min a week of aerobic exercise with complementary flexibility and resistance training. While it can initially seem counterintuitive, exercise is also a recommended treatment for cancer-related fatigue [45]. Despite the wealth of data supporting the benefits of exercise, several challenges to widespread program implementation have been identified [1, 11, 13, 39]. Community-based programs targeted to cancer survivors are growing, such as the programs provided at YMCA’s across the country in partnership with LIVESTRONG (http://www.livestrong.org/What-We-Do/Our-Actions/Programs-Partnerships/LIVESTRONG-at-the-YMCA/LIVESTRONG-at-the-YMCA-Locations).

Avoid weight gain

As with exercise, excess weight is a known cancer risk factor but has also been shown to drive outcomes after diagnosis, including recurrence, survival, quality of life, and side effects treatment, such as for lymphedema [13, 46, 47, 54, 55, 56]. Weight at diagnosis is the strongest lifestyle predictor of disease and quality of life outcomes in women with breast cancer [48]. Regardless of baseline weight, weight gain after diagnosis also significantly increased the risk of mortality among breast cancer survivors [49]. In prostate cancer, obesity at the time of diagnosis is associated with an elevated risk of prostate specific antigen (PSA) failure [50]. In colon cancer, limited data suggest that class II and III obesity may increase the risk of mortality and recurrence in survivors [50–52, 53]. Risk of both cardiovascular disease and diabetes increases with weight and weight gain as well.

Balanced against the risk associated with excess weight is the knowledge that cancer treatment can result in unintended weight loss and malnourishment. In these individuals, additional weight loss poses problems, decreasing quality of life, interfering with treatment adherence, and increasing complication risk.

Despite the difficulty of losing weight, several interventions have shown promise and delivered significant changes in weight among cancer survivors, including both face-to-face [57, 58] and distance-based interventions employing print and phone modalities[59, 60]. However, maintaining the weight loss remains a challenge in cancer survivors [61].

Eat a healthy diet

Many individuals come to a cancer diagnosis with a history of unhealthy eating habits, but the point of diagnosis provides an opportunity to make dietary choices that improve health. As with physical activity and obesity, some of the benefits to a healthy diet in cancer survivors come from the reduction in risk of other chronic diseases, including diabetes and heart disease [62]. However, evidence also points to direct cancer-related benefits to a healthy diet.

The Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study (WINS) randomized women with early-stage breast cancer to a low-fat diet and found a significant reduction in risk of recurrence [63]. However, the women on the low-fat diet also lost weight, which may confound the dietary findings. In contrast, the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) study found no effect of a high fiber, fruit, and vegetable and low-fat diet on recurrence among breast cancer survivors [64]. Despite the known benefits of a healthy diet in preventing cancer [65, 66], few specific diet components have been evaluated in cancer survivors. Data from the Nurses’ Health Study showed a significant reduction in mortality among breast cancer survivors adhering to a diet high in fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, poultry, and fish [67]. Earlier analyses in this population suggested no effect of a low-fat diet [68], but a more recent report indicated dietary fat intake after diagnosis increases mortality risk in women with breast cancer [69]. Similar results have been seen in other observational studies that evaluated dietary patterns [70–72]. A high-fiber diet was nonsignificantly associated with reduced risk of mortality in a cohort of breast cancer survivors [73]. Observational data have also linked dietary components to reduced risk of recurrence for men with prostate cancer, specifically intake of fish, tomato sauce, and monounsaturated fats [72, 74]. Fruit and vegetable consumption is also associated with improved quality of life, physical, and cognitive function in survivors [54, 75].

Eating a healthy diet should not be confused with the intake of dietary supplements, which have shown little or no benefit for prognosis after cancer and may in fact result in worse outcomes [76]. The exception to this is intake of vitamin D and calcium, which are recommended to preserve bone health in those who have undergone hormone therapies [77]. As a result, both the American Cancer Society (ACS) [78] and the World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research have advocated meeting dietary needs through food [65].

WHEL and WINS both demonstrated that interventions in cancer survivors can demonstrate significant dietary changes. Other studies have also had success in improving the diets of survivors. For example, in a 10-month tailored print material intervention, FRESH START significantly decreased saturated fat and improved fruit and vegetable consumption as well as overall diet quality and maintained those changes 2 years after the study started [79, 80].

Drink alcohol in moderation, if at all

The dual health effects of alcohol make concise pubic health recommendations a challenge, even more so for cancer survivors. There is good evidence that moderate alcohol consumption lowers the risk of cardiovascular disease [81, 82], but alcohol also increases cancer risk. In cancer survivors, alcohol consumption has been linked to worse prognosis [83]. However, with half of deaths in cancer survivors attributable to cardiovascular disease [76], there is a need to balance risks and benefits. Because of the potential harms, nondrinkers should not start drinking to reduce cardiovascular disease risk and should turn to other lifestyle strategies. Those who drink moderately need not stop. Heavy drinkers should cut back to moderate levels or stop drinking altogether. Alcohol consumption may vary widely across diagnoses. One study of testicular cancer survivors [84] noted that over 75 %of those surveyed reported regular alcohol consumption, while in a study of colorectal cancer survivors reported that only 8 %were heavy drinkers [75].

Stay connected with friends, family, and other survivors

Maintaining social support from friends and family is an evidence-based approach to improving quality of life after a cancer diagnosis. Social support, including that obtained through formal support groups, has been shown to reduce stress, depression, and fatigue in cancer survivors and lead to improvements in mood, self-image, and global quality of life [85–89]. While social support has not been shown to reduce risk of recurrence or mortality [85, 90–92], the quality of life benefits are real and meaningful. Social support also facilitates other positive behavioral changes, such as increasing physical activity [93].

Get screening tests and go to your regular check-ups

While many cancer survivors receive recommendations for ongoing surveillance of their cancer recurrence risk, preventive testing related to other causes of disease and death can lag. A recent report indicated that prostate cancer survivors were less likely than noncancer controls to be compliant with colorectal cancer screening [94]. Among colon cancer survivors, nearly all (97 %) were compliant with colonoscopy, but 20 % were not compliant with mammography and 37 % were not compliant with Pap smear [95]. Similarly, a national study found the majority of cancer survivors had multiple cardiovascular disease risk factors and more than a third were at high cardiac risk [8]. Such findings highlight the need not just for cancer screening but also for cardiovascular risk factor screening, diabetes screening, and even osteoporosis screening. Together, this indicates a need for regular noncancer care to ensure cancer survivors lead healthy lives engaging in behaviors that reduce their risk of disability and death.

The need for implementation

Unfortunately, the gaps in survivorship care are well-established [13, 96]. The result of the gaps in care is that lifestyle management of cancer-related endpoints is also not adequately addressed. Most cancer survivors do not follow the cancer prevention guidelines [11, 65, 66] that have existed for some time [3, 97]. Yet, survivors do make behavior changes and are more likely to make positive than negative changes [3, 98]. Thus, the challenge is implementing survivorship programming that directs survivors to the lifestyle behavior choices most likely to benefit them [4–7, 13, 39].

Implementation of lifestyle interventions is subject to the same challenges that cancer care faces as survivors transition from active treatment to ongoing disease monitoring and management. These were detailed extensively in the Institute of Medicine report on the challenges in cancer survivor care [99] and include not just patient challenges, but those faced by providers and institutions. Similarly, Stanton details some of the key challenges to implementing psychosocial care for quality of life after treatment, including the heterogeneity of patient trajectories, the transition from the treatment to posttreatment phase, long-term effects that differ from those in the period more proximal to treatment, and demographic differences in physical and psychosocial outcomes [100].

Implementation of lifestyle interventions may be subject to additional burdens as they occur outside of treatment facilities, are often not covered by insurance for those who have it, and often lack support outside of urban areas and major medical centers. Fortunately, many aspects of the eight ways for cancer survivors can be implemented without expensive facilities or medical support. The brochure in Fig. 1 provides a starting point for initiating this counseling. For example, choosing a whole food diet based on fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and lean proteins can be done anywhere. Most cancer survivors can engage in walking, starting with a low dose and low intensity and progressing as tolerated to meet recommendations. Phone and Internet-based supports exist for smoking cessation and weight management through websites like www.becomeanex.org. Evidence suggests that a physician recommendation for change is associated with an increased likelihood of behavior change adoption among cancer survivors [4, 8, 101]. The implementation of these guidelines, like those for prevention, can also be considered in the broader context of shared decision-making [102].

Conclusion

The cancer diagnosis often provides a moment of opportunity to consider lifestyle choices as survivors seek guidance from clinicians on what lifestyle choices are most beneficial. In a time where both high- and low-quality health information are readily available through the Internet- and nonevidence-based sources, patients benefit from simple messages grounded in a strong scientific evidence base. It was this premise that led to the expansion of the “Eight Ways to Stay Healthy and Prevent Cancer” to the new “Cancer Survivors’ Eight Ways to Stay Healthy After Cancer.” Reflecting the secular trend toward growing interest in survivorship health, several similar guidelines were developed and released at this time, including the American Cancer Society’s (ACS) Nutrition and Physical Activity Guidelines for Cancer Survivors, a report intended to provide health care providers with information to support informed choices among survivors and their families [103]. Both the ACS guidelines and ours emphasize the importance of exercise and weight management, but differ in the level of attention given to diet, tobacco, and social support. These recommendations provide a starting point for engaging in lifestyle counseling and can be used by patients, providers, cancer centers, and community support groups to focus on strategies most likely to yield benefit with minimal risks and side effects.

Acknowledgments

Drs. Wolin and Colditz are supported by Grant U54 CA155496 from the National Cancer Institute. This work was also supported by the Barnes Jewish Hospital Foundation.

References

- 1.Kim DJ, Rockhill B, Colditz GA. Validation of the Harvard Cancer Risk Index: a prediction tool for individual cancer risk. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57:332–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2003.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dart H, Wolin KY, Colditz GA. Commentary: eight ways to prevent cancer: a framework for effective prevention messages for the public. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:601–608. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9924-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC): Cancer survivors–United States, 2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60:269–272. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown BWB, Brauner CC, Minnotte MCM. Noncancer deaths in white adult cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1993;85:979–987. doi: 10.1093/jnci/85.12.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hewitt M, Rowland JH, Yancik R. Cancer survivors in the United States: age, health, and disability. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:82–91. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.M82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wingo PA, Ries LA, Parker SL, Heath CW. Long-term cancer patient survival in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1998;7:271–282. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones L, Demark-Wahnefried W. Recommendations for health behavior and wellness following primary treatment for cancer. In: Hewitt M, Ganz PA, editors. Implementing survivorship care planning. Washington, D.C.: Institute of Medicine of the National Academies; The National Academies Press; 2007. pp. 166–205. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Enright KA, Krzyzanowska MK. Control of cardiovascular risk factors among adult cancer survivors: a population-based survey. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:1867–1874. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9614-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stovell E. Resources for completing the care plan. In: Hewitt M, Ganz PA, editors. Implementing cancer survivorship care planning. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2007. pp. 64–106. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Koroukian SM, Murray P, Madigan E. Comorbidity, disability, and geriatric syndromes in elderly cancer patients receiving home health care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2304–2310. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dart H, Wolin KY, Colditz GA. Commentary: eight ways to prevent cancer: a framework for effective prevention messages for the public. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23(4):601–608. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9924-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogle KS, Swanson GM, Woods N, Azzouz F. Cancer and comorbidity: redefining chronic diseases. Cancer. 2000;88:653–663. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(20000201)88:3<653::AID-CNCR24>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolin KY, Colditz GA, Proctor EK (2011) Maximizing benefits for effective cancer survivorship programming: defining a dissemination and implementation plan. Oncologist 16(8):1189–1196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.http://www.canceradvocacy.org

- 15.Ostroff JS, Dhingra LK. Smoking cessation and cancer survivors. In: Feuerstein M, editor. Handbook of cancer survivorship. New York, NY: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Day GL, Blot WJ, Shore RE, McLaughlin JK, Austin DF, Greenberg RS, Liff JM, Preston-Martin S, Sarkar S, Schoenberg JB, et al. Second cancers following oral and pharyngeal cancers: role of tobacco and alcohol. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1994;86:131–137. doi: 10.1093/jnci/86.2.131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Khuri FR, Kim ES, Lee JJ, Winn RJ, Benner SE, Lippman SM, Fu KK, Cooper JS, Vokes EE, Chamberlain RM, Williams B, Pajak TF, Goepfert H, Hong WK. The impact of smoking status, disease stage, and index tumor site on second primary tumor incidence and tumor recurrence in the head and neck retinoid chemoprevention trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2001;10:823–829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Do K-A, Johnson MM, Doherty DA, Lee JJ, Wu XF, Dong Q, Hong WK, Khuri FR, Fu KK, Spitz MR. Second primary tumors in patients with upper aerodigestive tract cancers: joint effects of smoking and alcohol (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:131–138. doi: 10.1023/A:1023060315781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bluman LG, Mosca L, Newman N, Simon DG. Preoperative smoking habits and postoperative pulmonary complications. Chest. 1998;113:883–889. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.4.883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fujisawa T, Iizasa T, Saitoh Y, Sekine Y, Motohashi S, Yasukawa T, Shibuya K, Hiroshima K, Ohwada H. Smoking before surgery predicts poor long-term survival in patients with stage I non-small-cell lung carcinomas. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:2086–2091. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.7.2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Videtic GMM, Stitt LW, Dar AR, Kocha WI, Tomiak AT, Truong PT, Vincent MD, Yu EW. Continued cigarette smoking by patients receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy for limited-stage small-cell lung cancer is associated with decreased survival. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1544–1549. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.10.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alsadius D, Hedelin M, Johansson K-A, Pettersson N, Wilderäng U, Lundstedt D, Steineck G. Tobacco smoking and long-lasting symptoms from the bowel and the anal-sphincter region after radiotherapy for prostate cancer. Radiother Oncol. 2011;101(3):495–501. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tucker MA, Murray N, Shaw EG, Ettinger DS, Mabry M, Huber MH, Feld R, Shepherd FA, Johnson DH, Grant SC, Aisner J, Johnson BE. Second primary cancers related to smoking and treatment of small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer Working Cadre. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1782–1788. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.23.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jang S, Prizment A, Haddad T, Robien K, Lazovich D. Smoking and quality of life among female survivors of breast, colorectal and endometrial cancers in a prospective cohort study. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:115–122. doi: 10.1007/s11764-010-0147-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Department of Health and Human Services (2004) The health consequences of smoking: a report of the surgeon general. US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Atlanta, GA

- 26.Kanis JA, Johnell O, Oden A, Johansson H, de Laet C, Eisman JA, Fujiwara S, Kroger H, McCloskey EV, Mellstrom D, Melton LJ, Pols H, Reeve J, Silman A, Tenenhouse A. Smoking and fracture risk: a meta-analysis. Osteoporos Int. 2005;16:155–162. doi: 10.1007/s00198-004-1640-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall AE, Boyes AW, Bowman J, Walsh RA, James EL, Girgis A. Young adult cancer survivors’ psychosocial well-being: a cross-sectional study assessing quality of life, unmet needs, and health behaviors. Support Care Cancer. 2011;20(6):1333–1341. doi: 10.1007/s00520-011-1221-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellizzi KM. Health Behaviors of cancer survivors: examining opportunities for cancer control intervention. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8884–8893. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.2343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Coups EJ, Ostroff JS. A population-based estimate of the prevalence of behavioral risk factors among adult cancer survivors and noncancer controls. Prev Med. 2005;40:702–711. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park ER, Japuntich SJ, Rigotti NA, Traeger L, He Y, Wallace RB, Malin JL, Zallen JP, Keating NL. A snapshot of smokers after lung and colorectal cancer diagnosis. Cancer. 2012;118(12):3153–3164. doi: 10.1002/cncr.26545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gritz ER, Carr CR, Rapkin D, Abemayor E, Chang LJ, Wong WK, Belin TR, Calcaterra T, Robbins KT, Chonkich G, et al. Predictors of long-term smoking cessation in head and neck cancer patients. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1993;2:261–270. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Emmons KM, Puleo E, Park E, Gritz ER, Butterfield RM, Weeks JC, Mertens A, Li FP. Peer-delivered smoking counseling for childhood cancer survivors increases rate of cessation: the partnership for health study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6516–6523. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.07.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Goldstein MG, Niaura R, Willey C, Kazura A, Rakowski W, DePue J, Park E. An academic detailing intervention to disseminate physician-delivered smoking cessation counseling: smoking cessation outcomes of the Physicians Counseling Smokers Project. Prev Med. 2003;36:185–196. doi: 10.1016/S0091-7435(02)00018-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.de Moor JS, Puleo E, Ford JS, Greenberg M, Hodgson DC, Tyc VL, Ostroff J, Diller LR, Levy AG, Sprunck-Harrild K, Emmons KM. Disseminating a smoking cessation intervention to childhood and young adult cancer survivors: baseline characteristics and study design of the partnership for health-2 study. BMC Cancer. 2011;11:165. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-11-165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dresler CM (2012) Oncologists should intervene. Cancer 118(12):3012–3013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Evangelista LS, Sarna L, Brecht ML, Padilla G, Chen J. Health perceptions and risk behaviors of lung cancer survivors. Heart Lung. 2003;32:131–139. doi: 10.1067/mhl.2003.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Surgeon General No safe level for secondhand smoke. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:320. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.6.320. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmitz KH, Courneya KS, Matthews C, Demark-Wahnefried W, Galvão DA, Pinto BM, Irwin ML, Wolin KY, Segal RJ, Lucia A, Schneider CM, von Gruenigen VE, Schwartz AL. American college of sports medicine: American college of sports medicine roundtable on exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2010;42:1409–1426. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181e0c112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolin KY, Schwartz AL, Matthews CE, Courneya KS, Schmitz KH. Implementing the exercise guidelines for cancer survivors. J Support Oncol. 2012;10(5):171–177. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2012.02.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meyerhardt JA, Heseltine D, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, Thomas J, Nelson H, Whittom R, Hantel A, Schilsky RL, Fuchs CS. Impact of physical activity on cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from CALGB 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3535–3541. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meyerhardt JA, Giovannucci EL, Holmes MD, Chan AT, Chan JA, Colditz GA, Fuchs CS. Physical activity and survival after colorectal cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3527–3534. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.0855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ibrahim EM, Al-Homaidh A (2011) Physical activity and survival after breast cancer diagnosis: meta-analysis of published studies. Med Oncol 28(3):753–765 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Speck RM, Courneya KS, Mâsse LC, Duval S, Schmitz KH. An update of controlled physical activity trials in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:87–100. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee . Physical activity guidelines advisory committee. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 45.National Comprehensive Cancer Network NCCN: NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology (NCCN Guidelines): Cancer-Related Fatigue. National Comprehensive Cancer Network, Inc; 2010, version 1.2011

- 46.Wolin KY, Carson K, Colditz GA. Obesity and cancer. Oncologist. 2010;15:556–565. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2009-0285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Demark-Wahnefried W, Platz EA, Ligibel JA, Blair CK, Courneya KS, Meyerhardt JA, Ganz PA, Rock CL, Schmitz KH, Wadden T, Philip EJ, Wolfe B, Gapstur SM, Ballard-Barbash R, McTiernan A, Minasian L, Nebeling L, Goodwin PJ. The role of obesity in cancer survival and recurrence. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1244–1259. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fine JT, Colditz GA, Coakley EH, Moseley G, Manson JE, Willett WC, Kawachi I. A prospective study of weight change and health-related quality of life in women. JAMA. 1999;282:2136–2142. doi: 10.1001/jama.282.22.2136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kroenke CH, Chen WY, Rosner B, Holmes MD. Weight, weight gain, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1370–1378. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyerhardt JA, Ma J, Courneya KS (2010) Energetics in colorectal and prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol 28(26):4066–4073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Meyerhardt JA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Mayer RJ, Nelson H, Whittom R, Hantel A, Thomas J, Fuchs CS. Impact of body mass index and weight change after treatment on cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer: findings from Cancer and Leukemia Group B 89803. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4109–4115. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.6687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meyerhardt JA, Tepper JE, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis DR, McCollum AD, Brady D, O’Connell MJ, Mayer RJ, Cummings B, Willett C, Macdonald JS, Benson AB, Fuchs CS. Impact of body mass index on outcomes and treatment-related toxicity in patients with stage II and III rectal cancer: findings from Intergroup Trial 0114. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:648–657. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.07.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dignam JJ, Polite BN, Yothers G, Raich P, Colangelo L, O’Connell MJ, Wolmark N. Body mass index and outcomes in patients who receive adjuvant chemotherapy for colon cancer. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1647–1654. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mosher CE, Sloane R, Morey MC, Snyder DC, Cohen HJ, Miller PE, Demark-Wahnefried W. Associations between lifestyle factors and quality of life among older long-term breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer. 2009;115:4001–4009. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ahmed RL, Schmitz KH, Prizment AE, Folsom AR. Risk factors for lymphedema in breast cancer survivors, the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;130:981–991. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1667-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meeske KA, Sullivan-Halley J, Smith AW, McTiernan A, Baumgartner KB, Harlan LC, Bernstein L. Risk factors for arm lymphedema following breast cancer diagnosis in Black women and White women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;113:383–391. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-9940-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Djuric Z, DiLaura NM, Jenkins I, Darga L, Jen CK, Mood D, Bradley E, Hryniuk WM. Combining weight-loss counseling with the weight watchers plan for obese breast cancer survivors. Obes Res. 2002;10:657–665. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mefferd K, Nichols JF, Pakiz B, Rock CL. A cognitive behavioral therapy intervention to promote weight loss improves body composition and blood lipid profiles among overweight breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;104:145–152. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9410-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Demark-Wahnefried W, Morey MC, Sloane R, Snyder DC, Miller PE, Hartman TJ, Cohen HJ. Reach out to enhance wellness home-based diet-exercise intervention promotes reproducible and sustainable long-term improvements in health behaviors, body weight, and physical functioning in older, overweight/obese cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2354–2361. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.40.0895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Befort CA, Klemp JR, Austin HL, Perri MG, Schmitz KH, Sullivan DK, Fabian CJ. Outcomes of a weight loss intervention among rural breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;132:631–639. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1922-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Greenlee HA, Crew KD, Mata JM, McKinley PS, Rundle AG, Zhang W, Liao Y, Tsai WY, Hershman DL (2012) A pilot randomized controlled trial of a commercial diet and exercise weight loss program in minority breast cancer survivors. Obesity. doi:10.1038/oby.2012.177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Agriculture UDO, Services UDOHH (2010) Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2010. 7(null) edn. US Government Printing Office, Washington DC

- 63.Chlebowski RT, Blackburn GL, Thomson CA, Nixon DW, Shapiro A, Hoy MK, Goodman MT, Giuliano AE, Karanja N, McAndrew P, Hudis C, Butler J, Merkel D, Kristal A, Caan B, Michaelson R, Vinciguerra V, Del Prete S, Winkler M, Hall R, Simon M, Winters BL, Elashoff RM. Dietary fat reduction and breast cancer outcome: interim efficacy results from the Women’s Intervention Nutrition Study. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:1767–1776. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pierce JP, Natarajan L, Caan BJ, Parker BA, Greenberg ER, Flatt SW, Rock CL, Kealey S, Al-Delaimy WK, Bardwell WA, Carlson RW, Emond JA, Faerber S, Gold EB, Hajek RA, Hollenbach K, Jones LA, Karanja N, Madlensky L, Marshall J, Newman VA, Ritenbaugh C, Thomson CA, Wasserman L, Stefanick ML. Influence of a diet very high in vegetables, fruit, and fiber and low in fat on prognosis following treatment for breast cancer: the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) randomized trial. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2007;298:289–298. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.World Cancer Research Fund/American Institute for Cancer Research . Food, nutrition, physical activity and the prevention of cancer: a global perspective. Washington, DC: AICR; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kushi LH, Byers T, Doyle C, Bandera EV, McCullough M, McTiernan A, Gansler T, Andrews KS, Thun MJ. American Cancer Society 2006 Nutrition and Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee: American Cancer Society Guidelines on Nutrition and Physical Activity for cancer prevention: reducing the risk of cancer with healthy food choices and physical activity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:254–281. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.5.254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kroenke CH, Fung TT, Hu FB, Holmes MD. Dietary patterns and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:9295–9303. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.0198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Holmes MD, Stampfer MJ, Colditz GA, Rosner B, Hunter DJ, Willett WC. Dietary factors and the survival of women with breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1999;86:826–835. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19990901)86:5<826::AID-CNCR19>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Beasley JM, Newcomb PA, Trentham-Dietz A, Hampton JM, Bersch AJ, Passarelli MN, Holick CN, Titus-Ernstoff L, Egan KM, Holmes MD, Willett WC. Post-diagnosis dietary factors and survival after invasive breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128:229–236. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-1323-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Meyerhardt JA, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, Saltz LB, Hu FB, Mayer RJ, Nelson H, Whittom R, Hantel A, Thomas J, Fuchs CS. Association of dietary patterns with cancer recurrence and survival in patients with stage III colon cancer. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2007;298:754–764. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.7.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pierce JP, Stefanick ML, Flatt SW, Natarajan L, Sternfeld B, Madlensky L, Al-Delaimy WK, Thomson CA, Kealey S, Hajek R, Parker BA, Newman VA, Caan B, Rock CL. Greater survival after breast cancer in physically active women with high vegetable-fruit intake regardless of obesity. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2345–2351. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.6819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chan JM, Holick CN, Leitzmann MF, Rimm EB, Willett WC, Stampfer MJ, Giovannucci EL. Diet after diagnosis and the risk of prostate cancer progression, recurrence, and death (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2006;17:199–208. doi: 10.1007/s10552-005-0413-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Belle FN, Kampman E, McTiernan A, Bernstein L, Baumgartner K, Baumgartner R, Ambs A, Ballard-Barbash R, Neuhouser ML. Dietary fiber, carbohydrates, glycemic index, and glycemic load in relation to breast cancer prognosis in the HEAL cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20:890–899. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-10-1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Kim DJ, Gallagher RP, Hislop TG, Holowaty EJ, Howe GR, Jain M, McLaughlin JR, Teh CZ, Rohan TE. Premorbid diet in relation to survival from prostate cancer (Canada) Cancer Causes Control. 2000;11:65–77. doi: 10.1023/A:1008913620344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Grimmett C, Bridgewater J, Steptoe A, Wardle J. Lifestyle and quality of life in colorectal cancer survivors. Qual Life Res. 2011;20:1237–1245. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9855-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Robien K, Demark-Wahnefried W, Rock CL. Evidence-based nutrition guidelines for cancer survivors: current guidelines, knowledge gaps, and future research directions. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:368–375. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2010.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gralow JR, Biermann JS, Farooki A, Fornier MN, Gagel RF, Kumar RN, Shapiro CL, Shields A, Smith MR, Srinivas S, Van Poznak CH. NCCN task force report: bone health in cancer care. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2009;7(suppl 3):S1–S32. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2009.0076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Doyle C, Kushi LH, Byers T, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Grant B, McTiernan A, Rock CL, Thompson C, Gansler T, Andrews KS. Nutrition, Physical Activity and Cancer Survivorship Advisory Committee, American Cancer Society: nutrition and physical activity during and after cancer treatment: an American Cancer Society guide for informed choices. CA Cancer J Clin. 2006;56:323–353. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.56.6.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Christy SM, Mosher CE, Sloane R, Snyder DC, Lobach DF, Demark-Wahnefried W. Long-term dietary outcomes of the FRESH START intervention for breast and prostate cancer survivors. J Am Diet Assoc. 2011;111:1844–1851. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Demark-Wahnefried W, Clipp EC, Lipkus IM, Lobach D, Snyder DC, Sloane R, Peterson B, Macri JM, Rock CL, McBride CM, Kraus WE. Main outcomes of the FRESH START trial: a sequentially tailored, diet and exercise mailed print intervention among breast and prostate cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2709–2718. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.10.7094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thun MJ, Peto R, Lopez AD, Monaco JH, Henley SJ, Heath CW, Doll R. Alcohol consumption and mortality among middle-aged and elderly U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1705–1714. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199712113372401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Rimm EB, Williams P, Fosher K, Criqui M, Stampfer MJ. Moderate alcohol intake and lower risk of coronary heart disease: meta-analysis of effects on lipids and haemostatic factors. BMJ. 1999;319:1523–1528. doi: 10.1136/bmj.319.7224.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Deleyiannis FW, Thomas DB, Vaughan TL, Davis S. Alcoholism: independent predictor of survival in patients with head and neck cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1996;88:542–549. doi: 10.1093/jnci/88.8.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jacobs L, Alavi J, DeMichel A, Palmers S, Stricker C, Vaughn D. Comprehensive long-term follow-up. Cancer survivorship centers. In: Feuerstein M, editor. Handbook of cancer survivorship. New York, NY: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Goodwin PJ, Leszcz M, Ennis M, Koopmans J, Vincent L, Guther H, Drysdale E, Hundleby M, Chochinov HM, Navarro M, Speca M, Hunter J. The effect of group psychosocial support on survival in metastatic breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:1719–1726. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Høyer M, Johansson B, Nordin K, Bergkvist L, Ahlgren J, Lidin-Lindqvist A, Lambe M, Lampic C. Health-related quality of life among women with breast cancer—a population-based study. Acta Oncol. 2011;50:1015–1026. doi: 10.3109/0284186X.2011.577446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Kwan ML, Ergas IJ, Somkin CP, Quesenberry CP, Neugut AI, Hershman DL, Mandelblatt J, Pelayo MP, Timperi AW, Miles SQ, Kushi LH. Quality of life among women recently diagnosed with invasive breast cancer: the Pathways Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:507–524. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0764-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Andersen BL. Psychological interventions for cancer patients to enhance the quality of life. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:552–568. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.60.4.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Campbell LC, Keefe FJ, Scipio C, McKee DC, Edwards CL, Herman SH, Johnson LE, Colvin OM, McBride CM, Donatucci C. Facilitating research participation and improving quality of life for African American prostate cancer survivors and their intimate partners. A pilot study of telephone-based coping skills training. Cancer. 2007;109:414–424. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kroenke CH, Kubzansky LD, Schernhammer ES, Holmes MD, Kawachi I. Social networks, social support, and survival after breast cancer diagnosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:1105–1111. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.2846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Epplein M, Zheng Y, Zheng W, Chen Z, Gu K, Penson D, Lu W, Shu X-O. Quality of life after breast cancer diagnosis and survival. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:406–412. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.6951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Edwards AG, Hulbert-Williams N, Neal RD (2008) Psychological interventions for women with metastatic breast cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 3. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18646104 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 93.Alfano CM, Day JM, Katz ML, Herndon JE, Bittoni MA, Oliveri JM, Donohue K, Paskett ED. Exercise and dietary change after diagnosis and cancer-related symptoms in long-term survivors of breast cancer: CALGB 79804. Psycho-Oncology. 2009;18:128–133. doi: 10.1002/pon.1378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Snyder CF, Frick KD, Herbert RJ, Blackford AL, Neville BA, Carducci MA, Earle CC. Preventive care in prostate cancer patients: following diagnosis and for five-year survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2011;5:283–291. doi: 10.1007/s11764-011-0181-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Kunitake H, Zheng P, Yothers G, Land SR, Fehrenbacher L, Giguere JK, Wickerham DL, Wickerham L, Ganz PA, Ko CY. Routine preventive care and cancer surveillance in long-term survivors of colorectal cancer: results from National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project Protocol LTS-01. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5274–5279. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Institute of Medicine (2007) Implementing cancer survivorship care planning. Washington, DC: National Academies Press

- 97.Blanchard CM, Courneya KS, Stein K. American Cancer Society’s SCS-II: cancer survivors “adherence to lifestyle behavior recommendations and associations with health-related quality of life: results from the American Cancer Society”s SCS-II. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:2198–2204. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.6217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hawkins NA, Smith T, Zhao L, Rodriguez J, Berkowitz Z, Stein KD. Health-related behavior change after cancer: results of the American cancer society’s studies of cancer survivors (SCS) J Cancer Surviv. 2010;4:20–32. doi: 10.1007/s11764-009-0104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. Delivering Cancer Survivorship Care. In: Board NCP, editor. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: lost in transition. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine and National Research Council of the National Academies; 2006. pp. 187–321. [Google Scholar]

- 100.Stanton AL. What happens now? Psychosocial care for cancer survivors after medical treatment completion. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1215–1220. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.7406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Jones LW, Courneya KS, Fairey AS, Mackey JR. Effects of an oncologist’s recommendation to exercise on self-reported exercise behavior in newly diagnosed breast cancer survivors: a single-blind, randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2004;28:105–113. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2802_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Politi MC, Wolin KY, Légaré F (2013) Implementing clinical practice guidelines about health promotion and disease prevention through shared decision making. J Gen Intern Med. doi:10.1007/s11606-012-2321-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 103.Rock CLC, Doyle CC, Demark-Wahnefried WW, Meyerhardt JJ, Courneya KSK, Schwartz ALA, Bandera EVE, Hamilton KKK, Grant BB, McCullough MM, Byers TT, Gansler TT. Nutrition and physical activity guidelines for cancer survivors. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:275–276. doi: 10.3322/caac.21142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]