Abstract

Splicing of pre-messenger RNA into mature messenger RNA is an essential step for expression of most genes in higher eukaryotes. Defects in this process typically affect cellular function and can have pathological consequences. Many human genetic diseases are caused by mutations that cause splicing defects. Furthermore, a number of diseases are associated with splicing defects that are not attributed to overt mutations. Targeting splicing directly to correct disease-associated aberrant splicing is a logical approach to therapy. Splicing is a favorable intervention point for disease therapeutics, because it is an early step in gene expression and does not alter the genome. Significant advances have been made in the development of approaches to manipulate splicing for therapy. Splicing can be manipulated with a number of tools including antisense oligonucleotides, modified small nuclear RNAs (snRNAs), trans-splicing, and small molecule compounds, all of which have been used to increase specific alternatively spliced isoforms or to correct aberrant gene expression resulting from gene mutations that alter splicing. Here we describe clinically relevant splicing defects in disease states, the current tools used to target and alter splicing, specific mutations and diseases that are being targeted using splice-modulating approaches, and emerging therapeutics.

INTRODUCTION

Pre-mRNA splicing is the process of removing introns from pre-messenger RNA and ligating together exons to produce a mature messenger RNA (mRNA) that represents the template for protein translation. Any splicing errors will result in a disconnection between the coding gene and its encoded protein product. The splicing reaction must occur with high efficiency and fidelity in order to maximize gene expression and avoid the production of aberrant proteins1. A complex macromolecular machine, termed the spliceosome, catalyzes this reaction. The spliceosome consists of a dynamic set of hundreds of proteins and small RNAs2. The complexity of the spliceosome is likely key to achieving the splicing specificity of the diverse set of sequences that define exons and introns1.

The most conserved sequences that define exons and introns are the core splice site elements comprised of the 5′ splice site (5′ss), the branchpoint sequence (BPS), the polypyrimidine (Py) tract and the 3′ splice site (3′ss) (Figure 1a). These intronic sequences demarcate exons and are recognized, in most splicing reactions, by specific base-pairing interactions with the small nuclear RNA (snRNA) components of five ribonucleoproteins (snRNPs), U1, U2, U4, U5 and U62. These snRNPs are essential for orchestrating the splicing reaction, which occurs between bases within the core splicing sequences. The splicing reaction is initiated by U1 snRNP binding to the 5′ss, followed by U2 snRNP interactions at the branchpoint sequence and finally U4, U5 and U6 snRNP interactions near the 5′ and 3′ splice sites. The spliceosome is also made up a large number of other splicing factors, in addition to the snRNPs, including RNA binding proteins which bind in a sequence-specific manner to RNA and either enhance or silence splicing at nearby splice sites1. These so-called splicing enhancers and silencers can be classified by their locations in either exons or introns (ESE and ISE, for exonic or intronic splicing enhancers, and ESS and ISS for exonic or intronic splicing silencers, respectively (Figure 1a)1.

FIGURE 1.

Splicing, alternative splicing and pathogenic mutations that affect splicing outcomes. (a) A model of the splicing sequences and the components involved in their initial recognition during splicing by the major spliceosome. Exons are depicted as boxes and introns are lines. The canonical 5′ splice site (5′ss), branch point sequence (BPS), polypyrimidine tact (py tract) and 3′ splice site (3′ss) sequences are shown along with their interactions with the U1 and U2 snRNPs. The gray-lined snRNA and the major protein components of the snRNPs are labeled. Intronic and exonic splicing silencers (orange, ISS, and red, ESS) and enhancers (dark green, ESE, and light green, ISE) are depicted either with or without their trans-acting proteins bound. Alternative splicing of the middle exon produces mRNA isoforms 1 and 2 and results in two distinct protein isoforms, 1 and 2. (b) Common types of disease causing mutations that disrupt splicing are labeled in red along with their possible outcomes and the aberrant splicing pathway (bottom). De novo cryptic splice site mutations are represented by the terminal dinucleotides, GU (5′ss) and AG (3′ss).

Most pre-mRNAs can be spliced in different ways to produce distinct mature mRNA isoforms in a process called alternative splicing. Alternative splicing most commonly involves skipping of an exon(s)(Figure 1a), though the use of different 5′ss and 3′ss are also common alternative splicing events. In many cases the distinct mRNA isoforms produced from alternative splicing will code for proteins that have anywhere from subtle to dramatic functional differences3. Alternative splicing is an important mechanism to generate the phenotypic diversity of higher eukaryotes in that it expands gene expression complexity without an increase in the overall number of genes3. Alternative splicing is estimated to occur in most pre-mRNAs3, suggesting that splicing of most gene transcripts has an inherent flexibility that promotes modulation of protein expression and activity. Indeed, flanking introns often measure in multiples of the tri-nucleotide code, such that skipping a particular exon maintains the reading frame in the resulting mRNA. This mRNA then codes for a protein with an internal deletion corresponding to the loss of the amino acids encoded by the skipped exon4. Developmental, as well as tissue- and cell-type specific alternative splicing is common, with variations in the relative abundance of different spliced isoforms, which suggests a dynamic regulation5.

This review summarizes the different types of disease-causing genetic mutations that can affect splicing, and discusses other forms of splicing deregulation that are associated with disease. Different approaches that are currently investigated as candidate therapeutics to alter splicing as a means to compensate for or to correct aberrant are highlighted.

SPLICING DEFECTS THAT CAUSE DISEASE: THE PROBLEMS

Mutations that disrupt normal splicing have been estimated to account for up to a third of all disease-causing mutations6, 7. Although diseases and conditions caused by mutations that disrupt normal pre-mRNA splicing are common, it can be difficult to identify a splicing defect as the cause of a disease. Disease-associated mutations that occur within introns are, by default, usually assumed to alter splicing patterns, because they do not alter the coding sequence. Intronic mutations may disrupt the core splice sites (sequences within the 5′ss or 3′ss, the Py tract or BPS). Such mutations typically result in the skipping of the exon(s) upstream or downstream of the mutated splice site or in the retention of the intron (Figure 1b, lower panel). In many cases, when the authentic splice site is mutated a pseudo-splice site (a weak consensus splice site that is not recognized as a splice site under normal conditions) is activated within the flanking exon or intron (Figure 1b)8. Mutations in introns or exons can also disrupt or create de novo splicing silencers and enhancers or de novo cryptic splice sites (splice sites that are created by mutations). These types of mutations can affect splicing in a similar manner as mutations in the consensus splice sites and can also result in deregulation of alternative splicing (Figure 1). Intronic splice site mutations account for approximately 10–15% of annotated disease mutations9.

Mutations within coding exons can also affect splicing. Exonic mutations can result in the creation of a de novo cryptic slice site, disruption of an RNA secondary structure that has a regulatory function, or they can disrupt a splicing silencer or enhancer rendering the site unrecognizable by the sequence-specific RNA-binding protein that is required for splicing at a particular site. Such exonic mutations can be silent mutations or missense mutations and thus, may or may not alter the coding sequence. If a mutation changes coding, the molecular basis for the disease may be mistakenly ascribed to the change in amino acid incorporation rather than to aberrant splicing. Computational analysis of these types of exonic mutations predict that as many as 25% of mutations within exons alter splicing6, 7. Thus, overall, when considering both exonic and intronic locations, more than 30% of known genetic mutations are predicted to alter splicing6. The outcome of splicing mutations is usually the formation of an aberrant mRNA or quantitative changes in alternative mRNA isoform abundance and consequently loss of normal protein expression (Figure 1b). Other causes of aberrant constitutive or alternative splicing include mutations or quantitative changes of a protein that regulates splicing (Figure 1b). In this situation, aberrant splicing can occur in all of the RNA transcripts that are processed by the affected protein.

Rather than correcting aberrant splicing, the splicing reaction can also be targeted to induce aberrant splicing as a way to disrupt gene expression of proteins involved in disease pathogenesis. Similarly, splicing can be targeted to cause the skipping of exons that have nonsense mutations or deletions that disrupt protein coding. Such skipping of exons can be used to reframe and rescue protein expression. Nonsense mutations account for more than 10% of annotated disease-causing mutations9. Even more prevalent are small deletions and insertions, which account for more than 20% of documented mutations9. Given the prevalence of this type of mutation, the approach of splicing induced reading frame correction or reframing has potential to have a significant impact for disease therapeutics.

Whether as a tool to correct aberrant splicing or to induce aberrant splicing, the opportunities and impacts of therapeutics that target splicing are vast and a number of strategies have been developed to successfully treat disease by RNA splicing intervention.

MANIPULATING SPLICING: THE TOOLS

Targeting RNA splicing to correct the effects of a mutation bypasses the need to correct or replace mutated DNA or diseased cells, which is the approach of two other major therapeutic platforms: gene-replacement and some stem-cell therapies. Emerging RNA splicing-targeted therapies are proving to be a promising and powerful therapeutic approach, in part because of the wide range of mutations that can be corrected, the ease of delivery, and the success of the approaches in treating disease. The following section describes some of the basic tools that have been developed to manipulate splicing. For each approach, there have been numerous types of modifications developed to improve therapeutic and delivery methods. These improvements have helped the success of manipulating splicing as a therapy10, but will not be discussed in detail here. The intent of this review is to outline the general functional utility of the tools that have been developed and to provide an overview of specific examples of how these tools have been used to modulate splicing for potential disease therapy.

Antisense Oligonucleotides (ASO, AON)

ASOs are short oligonucleotides, typically 15–25 bases in length, which are the reverse complement sequence of a specific RNA transcript target region. ASOs function by forming Watson-Crick base-pairs with the target RNA10. ASO binding to a target RNA sterically blocks access of splicing factors to the RNA sequence at the target site. Thus, an ASO targeted to a splice site will block splicing at the site, redirecting splicing to an adjacent site (Figure 2a). Alternatively, ASOs targeted to a splicing enhancer or silencer can prevent binding of transacting regulatory splicing factors at the target site and effectively block or promote splicing (Figure 2a). ASOs have also been designed that can base-pair across the base of a splicing regulatory stem-loop in order to strengthen the stem-loop structure11. The sequence specificity of ASOs allows them to bind precisely to endogenous RNAs and, importantly, their fidelity allows targeting of distinct RNA isoforms. ASOs have also been designed to target only mutated gene alleles, which will be particularly valuable in developing therapies for mutations causing autosomal dominant diseases. These features make ASOs a versatile tool that can be used to correct or alter RNA expression for therapeutic benefit.

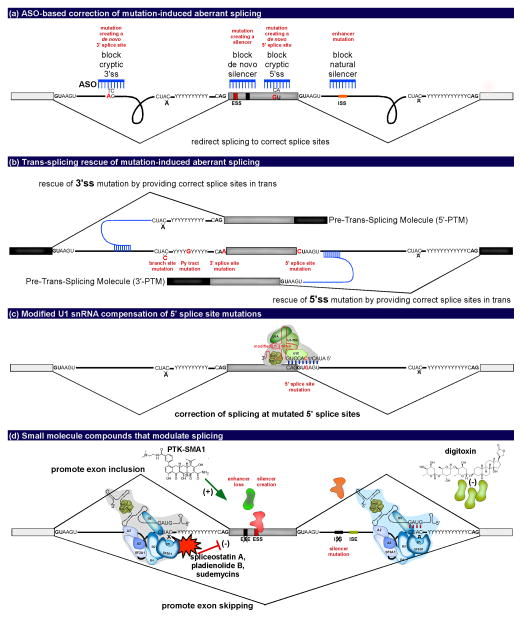

FIGURE 2.

Tools to correct aberrant splicing caused by mutations. (a) ASO-based correction of mutation-induced aberrant splicing depicting ways in which ASOs (blue) can be used to correct for mutations (red) to promote proper splicing and exon inclusion. (b) Trans-splicing rescue of mutation-induced aberrant splicing depicting the replacement of the 3′ or 5′ portion of an RNA with mutated 3′ or 5′ splice sites, respectively, by a pre-trans-splicing molecule (PTM). Core splicing sequence mutations are depicted in red. (c) Modified U1 snRNA compensation for a 5′ splice site mutation (red). Exogenous U1 snRNA with a compensatory mutation allows for base pairing with the 5′ splice site and the restoration of exon recognition and inclusion. (d) Small molecule compounds that modulate alternative splicing. Small molecules act in trans by binding spliceosome components to promote alternative exon inclusion to compensate for a mutation (examples noted in red lettering and represented with an X) or to alter mRNA isoforms for therapeutic benefit. Depicted are examples of small molecules that inhibit splicing (spliceostation A, pladienolide B, and sudemycins) and two small molecules that promote exon inclusion (PTK-SMA1 and digitoxin).

In addition to their specificity, ASOs have many other features that make them an ideal therapeutic tool. For example, ASOs are relatively non-invasive in that they do not alter the genome directly and improvements in chemistries have been developed to improve the utility of ASOs as a therapeutic drug10. Current technologies utilize ASOs that are very stable, are efficiently and spontaneously internalized by cells in vivo, have high substrate specificity and low toxicity, and are not degraded by endogenous RNase H10. The half-life of naked ASOs in mouse and human plasma and many mouse tissues is approximately 10–15 days10. Remarkably, treatment of mice with a single injection of ASOs early in life has been shown to correct splicing and disease-associated phenotypes for up to a year12, 13. The basis of this longevity is unclear. The enduring effect may be attributable to the stability of ASOs in post-mitotic cells where they are maintained and continue to influence splicing long after administration. Given the ease of delivery, favorable toxicity profile and enduring effects, ASOs are emerging as an ideal disease therapeutic10.

A number of variations on the basic ASO technology have been developed in order to tailor activity of the molecules after they base-pair to their target site. Such ASO modifications provide additional functions in cases where base-pairing is not sufficient for therapeutic splicing modification. A number of different dual-function, or bifunctional ASOs have been designed. For example some hybrid ASOs have been developed in which the antisense base-pairing sequence is linked to a consensus binding site sequence for a specific splicing factor. In this way, the ASO can be directed to bind to the target RNA and also recruit a protein. This protein, depending on its function and the location where the ASO binds, can either enhance14 or silence15, 16 splicing. ASOs have also been equipped with peptide sequences that provide an interaction domain to recruit splicing factors17. Recently, another type of bifunctional ASO was designed with a functional group, 2′deoxy-2′fluoro (2′F) nucleotide, that incidentally recruits the ILF2/3 protein, which has no known link to splicing. However, when targeted to bind near a 5′ss, the additional recruitment of ILF2/3 interfered with proper spliceosome assembly, generally resulting in the exclusion of the exon that borders the 5′ss from the mature mRNA18. In these examples, when proteins bind to an extended tail of an ASO or to the ASO backbone itself, the ASO acts as a portable splicing silencer or enhancer element (Figure 3a).

FIGURE 3.

Tools used to induce aberrant splicing for disease therapy. (a) Modulating alternative splicing for disease therapy using ASOs, bifunctional ASOs (e.g. 2′F ASO), or small molecules (SM). These therapeutics can be used to either promote exon inclusion or skipping in the presence or absence of a mutation. (b) Targeting splicing to disrupt gene expression by the use of ASOs to promote exon skipping to disrupt the reading frame (green versus yellow exons) and promote nonsense mediated decay (NMD). This processes is known as forced-splicing-dependent nonsense-mediated-decay (FSD-NMD). (c) Splicing-mediated rescue of gene expression disrupted by nonsense mutations. Top panel: The C to T point mutation that introduces a PTC either resulting in nonsense-mediated decay, or a truncated, nonfunctional protein. Middle panel: The use of ASOs (blue) to block the 5′ and 3′ splice sites promotes exon skipping. The reading frame remains intact (green exons) resulting in a truncated but functional protein. Bottom panel: The use of a PTM to replace the 3′ portion of the mRNA because the exons flanking the exon containing the PTC mutation are not in the same reading frame (green versus yellow exons). The use of the PTM results in a full length and functional protein.

The ultimate goal in the development of many ASO-based therapeutics, traditional, or bifunctional, is to either block the production of a toxic form of a protein, or to restore the production of a protein that is not made or is non-functional. For this, ASOs are designed that base-pair to pre-mRNA and influence splicing in such a way as to alter the protein-coding mRNA (Figure 2a). ASOs can be used to restore a functional protein that was lost due to mutation. To restore function, ASOs can be used to block cryptic or pseudo splice sites or to promote the inclusion of an exon by targeting splicing regulatory sequences (Figure 2a). For example, to eliminate an mRNA isoform that produces a detrimental protein, or in cases where a mutation introduces a nonsense or frame-shift mutation, ASOs can be designed to promote usage of a cryptic splice site, or to induce exon skipping to trigger the formation of a frame-shift and premature termination codon (PTC). Such aberrations typically elicit nonsense mediated decay (NMD) and degradation of the entire mRNA, and hence disallow the production of the protein. An alternative approach is to bypass a mutation that introduces a nonsense or frame-shift mutation. ASOs can accomplish either of these alterations in splicing by base-pairing and blocking the interaction of the region with splicing factors that are required for splicing at a particular splice site (Figure 2,3).

Trans-splicing

Trans-splicing is currently under development as a therapeutic for a number of diseases19. The trans-splicing methodology, often referred to as Spliceosomal-Mediated RNA trans-splicing (SMaRT)19, is designed to replace the entire coding sequence 5′ or 3′ of a target splice site. In this technology, a plasmid expresses a three-component Pre-Trans-Splicing Molecule, PTM. The PTM consists of an ASO that targets the endogenous intron of the mutated splice site, a synthetic splice site that directs splicing to bridge from the endogenous RNA to the PTM, and a copy RNA sequence that will be spliced to the endogenous RNA rather than to the mutated, inactive endogenous splice site. The ASO can be targeted either upstream or downstream of a consensus 3′ss or 5′ss, respectively, depending on the location of the mutation, and the desired mRNA portion to be replaced (Figure 2b). PTMs are most often used to replace the 3′ end of a mutated gene by utilizing the spliceosome to ligate the therapeutic coding sequence to the 5′ sequence of the endogenous RNA. However, this method can also be used to replace an internal exon or the 5′ region of a mutated gene19 (Figure 2b).

Trans-splicing is an effective means to correct expression of genes with mutations in the 5′ss or 3′ss, which cannot be readily corrected using other technologies. In particular, trans-splicing is the best solution if a splice site mutation is in the first or last nucleotides of the intron. The base specificity at these positions is important for the catalytic steps of the splicing reaction, and thus, it is difficult to rescue splice site activity. For these types of mutations, the approach that has been effective at correcting gene expression is trans-splicing.

Trans-splicing approaches necessitate the delivery of DNA expression vectors to cells. Thus, complications in the delivery of PTMs are similar to those seen with the delivery of whole gene replacements19. One benefit to trans-splicing over gene replacement is that the expression of the pre-mRNA of the target gene remains under endogenous control. The PTM only replaces a portion of a gene and therefore the endogenous promoter controls the transcription of the pre-mRNA. The trans-splicing molecule can only interact with an existing pre-mRNA and therefore the tissue, temporal and quantity specific expression of the gene are not altered 19. This technology is particularly useful when only small increases in therapeutic RNA is required, and some read-through of the mutated gene is tolerable. This is because 100% efficiency of trans-splicing may not be guaranteed, in part due to limitations in viral expression and delivery. PTMs can be especially beneficial in cases where an entire gene is too large to package and deliver to cells in a virus, but the gene’s product can be corrected with a replacement of a portion of the RNA.

Modified snRNAs

The U1 snRNA component of U1 snRNPs interacts with the 5′ss by specific base-pairing. A mutation in the 5′ss, which is a common disease-causing mutation, compromises U1 snRNA binding and can prevent spliceosome assembly and subsequent splicing (Figure 1a). To restore splicing, modified versions of the spliceosomal snRNAs have been created with sequence changes that restore base-pairing to the mutated 5′ss (Figure 2c). The complementary mutation allows the snRNA to effectively bind the mutant binding site of the pre-mRNA and restores normal splicing20 (Figure 2c). A drawback of this approach is that the snRNAs must be incorporated into an expression vector and delivered to cells. Thus, this methodology has similar limitations as trans-splicing approaches 20.

Small Molecule Compounds

Small molecules can function by directly modifying the activity of splicing factors or by indirectly altering splicing, frequently by unknown mechanisms (Figure 2d). Small molecule effectors of specific splicing events are often identified using high-throughput screening assays using cells that report alterations in a particular splicing event 21. However, frequently these molecules function in an indirect way on splicing. Thus, one drawback of small molecule therapeutics is the lack of specificity and information regarding the exact mechanism of action, which can lead to off-target effects. Nevertheless, a major benefit of some small molecules is that many are already approved and in use in clinical practice to treat diseases and conditions apart from splicing defects22, 23. Therefore, these molecules have been deemed safe for use in humans, which vastly accelerates their development as a treatment for a disease. In fact, there are numerous classes of small molecules currently being studied for their ability to therapeutically alter splicing. Small molecules provide a valuable therapeutic tool to manipulate splicing, but lack specificity and can have undesirable off-target effects.

TARGETING SPLICING IN DISEASE: THE FIXES

The tools described in the previous section have been used to manipulate splicing to achieve many different outcomes predicted to be therapeutically beneficial. Approaches for therapeutic RNA splicing interventions have focused either on correcting aberrant splicing that is associated with disease, or on inducing aberrant splicing in a way that can ameliorate disease phenotypes.

Correction of Aberrant Splicing

Splice site mutations

Mutations within the consensus sequence of the 5′ss, 3′ss or the branchpoint sequence that inactivate splicing are common. The approaches used to correct these mutations require careful consideration of the location of the mutation and its effect on splicing. Mutations in consensus splice site sequences are often catastrophic for splicing because these nucleotides, in particular the first and last dinucleotides of the intron, function specifically in the catalytic steps of splicing. Several different approaches are being used to correct the defects associated with splice site mutations (Figure 2).

Trans-splicing

Trans-splicing is the only RNA-targeting approach that has been effectively employed to rescue full-length gene expression that has been disrupted by mutations in the terminal dinucleotides of the intron. In trans-splicing approaches, the PMT molecule can be designed to deliver and express in trans the 5′ or 3′ half of the RNA transcript flanking the mutated sequence. This PMT molecule includes a sequence complementary to the intronic RNA for targeting and a consensus splice site which splices the PMT to the endogenous transcript, effectively producing a full-length, functional mRNA (Figure 2b). In trans-splicing, the specific mutation is not relevant because the PMT molecule delivers the wild-type sequence. This approach has been used to replace the first exon of the HBB (β-globin) gene as a therapy for β-thalassemia24 (Table 1, splice site mutations).

TABLE 1.

Examples of splicing-based therapeutic approaches.

| Disease | Human Target Gene | Therapeutic | Stage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CORRECTION OF ABERRANT SPLICING | ||||

|

| ||||

| Splice Site Mutations | ||||

|

| ||||

| Bardet-Biedl syndrome | BBS1 | U1/U6 snRNA* | Patient cells | 20, 28 |

|

| ||||

| Beta-thalassemia | HBB | PTM | Minigene | 24 |

|

| ||||

| Cancer | BRCA1 | ASO | Minigene | 34 |

| PTCH1 | ASO | Minigene | 34 | |

|

| ||||

| Cystic Fibrosis | CFTR | U1 snRNA* | Minigene | 26 |

|

| ||||

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | DMD | ASO | Canine model | 32, 33 |

|

| ||||

| Factor VII deficiency | F7 | U1 snRNA* | Minigene | 27 |

|

| ||||

| Familial dysautonomia | IKBKAP | SM | Patients | 35, 36, 106 |

|

| ||||

| Fanconi anemia | FANCC | U1 snRNA* | Patient cells | 25 |

|

| ||||

| Hemophilia A | F9 | U1 snRNA* | Minigene | 26 |

|

| ||||

| Propionic acidemia | PCCA | U1 snRNA* | Patient cells | 29 |

|

| ||||

| Retinitis pigmentosa | RHO | U1 snRNA* | Minigenes | 30 |

| RPGR | U1 snRNA* | Patient cells | 31 | |

|

| ||||

| Cryptic Splice Sites | ||||

|

| ||||

| Ataxia telangiectasia | ATM | ASO | Patient cells | 107 |

|

| ||||

| Beta-thalassemia | HBB | ASO | Mouse model | 38–42, 108 |

|

| ||||

| Cancer | BRCA2 | ASO | Minigene | 109 |

|

| ||||

| • CDG1A | PMM2 | ASO | Patient cells | 110 |

|

| ||||

| Congenital adrenal insufficiency | CYP11A | ASO | Minigene | 34 |

|

| ||||

| Cystic fibrosis | CFTR | ASO | Cell lines | 111 |

| SM | Patient cells | 47 | ||

|

| ||||

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | DMD | ASO | Patient cells | 100 |

|

| ||||

| Fukuyama congenital muscular dystrophy (FCMD) | FKTN | ASO | Mouse model | 43 |

|

| ||||

| Growth hormone insensitivity | GHR | ASO | Minigene | 112 |

|

| ||||

| • HPABH4A | PTS | ASO | Patient cells | 113 |

|

| ||||

| Hutchinson-Gilford progeria (HGPS) | LMNA | ASO | Mouse model | 44, 114 |

|

| ||||

| • MLC1 | MLC1 | ASO | Minigene | 115 |

|

| ||||

| Methylmalonic aciduria | MUT | ASO | Patient cells | 116, 117 |

|

| ||||

| Myopathy with lactic acidosis | ISCU | ASO | Patient cells | 118, 119 |

|

| ||||

| Myotonic dystrophy | CLC1 | ASO | Mouse model | 45 |

|

| ||||

| Neurofibromatosis | NF1 | ASO | Patient cells | 120 |

|

| ||||

| Niemann-Pick type C | NPC1 | ASO | Patient cells | 121 |

|

| ||||

| Propionic acidemia | PCCB | ASO | Patient cells | 117 |

|

| ||||

| Usher syndrome | USH1C | ASO | Mouse model | 46 |

|

| ||||

| Regulatory Sequence Mutations | ||||

|

| ||||

| Afibrinogenemia | FGB | ASO | Minigene | 48 |

|

| ||||

| Cancer | BRCA1 | ASO | In vitro | 17 |

|

| ||||

| Propionic acidemia | PCCA | ASO | Patient cells | 117 |

|

| ||||

| Neurofibromatosis | NF1 | SM | Patient cells | 50 |

|

| ||||

| Ocular albinism type 1 | GRP143 | ASO | Patient cells | 49 |

|

| ||||

| Deregulated Alternative Splicing | ||||

|

| ||||

| Alzheimer’s disease/FTDP-17 Taupathies | MAPT | ASO | Cell lines | 11, 18, 59 |

| PTM | Minigene | 60 | ||

| SM | Cell lines | 22 | ||

|

| ||||

| Cancer | BCL2L1 | ASO | Mouse model | 18, 62–65 |

| FGFR1 | ASO | Cell lines | 66 | |

| MCL1 | ASO | Cell lines | 67 | |

| MDM2 | ASO | Cell lines | 68 | |

| Multiple | SM | Cell lines | 72, 73 | |

| PKM | ASO | Cell lines | 18, 69 | |

| MST1R | ASO | Cell lines | 70 | |

| USP5 | ASO | Cell lines | 71 | |

|

| ||||

| Spinal muscular atrophy | SMN2 | ASO | Clinical trails phase Ib/IIa, ISIS-SMNRx | 12, 13, 17, 18, 52, 54, 122 |

| SM | Clincal trials | 51, 58 | ||

| U1 snRNA* | Minigene | 26 | ||

| PTM | Mouse model | 123, 124 | ||

|

| ||||

| INDUCTION OF ABERRANT SPLICING | ||||

|

| ||||

| Knock-down of Detrimental Gene Expression | ||||

|

| ||||

| Alzheimer’s disease | BACE1 | ASO | Cell lines | 125 |

|

| ||||

| Cancer | CDKN1A | SM | Cell lines | 126 |

| ERBB2 | ASO | Cell lines | 127, 128 | |

| FLT1 | ASO | Mouse model | 81 | |

| HNRNPH1 | ASO | Patient cells | 75 | |

| KDR | ASO | Mouse model | 76, 77 | |

| MYC | SM | Cell lines | 129 | |

| Multiple | SM | Clinical trials phase I, E7107 | 82–84, 86, 87, 89–91, 130 | |

| PHB | SM | Cell lines | 90 | |

| SRA1 | ASO | Cell lines | 131 | |

| STAT3 | ASO | Mouse model | 74 | |

| TERT | ASO | Cell lines | 132 | |

| WT1 | ASO | Cell lines | 133 | |

|

| ||||

| • FHBL/atherosclerosis | APOB | ASO | Cell lines | 134 |

|

| ||||

| Immune-response | CD40 | ASO | Cell lines | 135 |

|

| ||||

| Inflammatory disease | TNFRSF1B | ASO | Mouse model | 80 |

| IL5RA | ASO | Cell lines | 136 | |

|

| ||||

| Influenza virus | TMPRSS2 | ASO | Cell lines | 137 |

|

| ||||

| Muscle wasting diseases | MSTN | ASO | Mouse model | 78 |

|

| ||||

| Spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 | ATXN1 | ASO | Cell lines | 79 |

|

| ||||

| RNA Reframing | ||||

|

| ||||

| Duchenne muscular dystrophy | DMD | ASO | Clinical trials phase II, PRO051, AVI-4658, PRO044 | 95–105 |

| SM | Cell lines | 138 | ||

|

| ||||

| Dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa | COL7A1 | ASO | Explants | 92 |

| PTM | Patient cells | 93 | ||

|

| ||||

| Miyoshi myopathy | DYSF | ASO | Patient cells | 94 |

SM= small molecule; PTM=pre-trans-splicing molecule; ASO=antisense oligonucleotide;

modified. HUGO gene names are provided. The terms under Stage refers to the systems used in the most advanced studies for a particular gene or disease. Patient cells refers to studies performed using cells isolated from patients with the disease mutation; minigene refers to studies using a cloned portion of the disease gene; cell lines indicates conventional, transformed, high-passage number cell lines; explants refers to mouse tissue.

Full disease names are as follows: CDG1A = Congenital disorder of glycosylation, type Ia, HPABH4A = Hyperphenylalaninemia, BH4-deficient, A, MLC1 = Megalencephalic leukoencephalopathy with subcortical cysts, FHBL = Hypobetalipoproteinemia.

Modified snRNAs

Modified U1 snRNAs have been used to restore splice site recognition25 of the mutated and inactive U1 snRNA binding site in the 5′ss (Figure 2c). In this case, a modified U1 snRNA, which carries the compensatory mutation to the mutation at the pre-mRNA splice site, is introduced to cells. Modified U1 snRNAs have been used successfully to rescue splicing at mutated 5′ss in diseases including cystic fibrosis26, hemophilia B26, F7 deficiency27, Fanconi anemia25, Bardet-Biedl syndrome28, propionic acidemia 29, and retinitis pigmentosa 30, 31 (Table 1, splice site mutations). The restoration of these splicing events allows for the production of functional proteins and has potential to improve disease phenotype. However, to date, modified snRNAs have not successfully corrected splicing at a 5′ss mutated at the first or second nucleotides of the intron, likely due to the requirement of these specific nucleotides in splicing catalysis for function in addition to snRNA binding.

ASOs

ASOs have been used to restore gene expression in the context of a core splice site mutation. For example, ASOs provide a viable therapeutic approach in cases where a disabling splice site mutation activates a cryptic splice site or triggers exon skipping that produces an mRNA with a frameshift. In this situation, an ASO can be designed to redirect splicing to reframe the transcript and produce an mRNA with a restored reading frame that codes for a protein isoform with partial or full function. This approach has been used successfully to correct gene expression disrupted by a 3′ss mutation that causes exon skipping and consequently introduces a PTC in the DMD gene that causes Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy32, 33 (Table 1, splice site mutations).

Splice site mutations can also result in the activation of a pseudo splice site that is recognized by the spliceosome preferentially over the mutated site. In these cases, ASOs can be targeted to hybridize to the pseudo splice site and sterically block its activity. If there are no other cryptic splice sites that are stronger than the mutated authentic splice site, the ASO block may reactivate the mutated authentic splice site. This technique as has been used successfully for 5′ss mutations in BRCA1 and PTCH134. These types of splice site mutations have also been rescued using small molecules that can promote splicing to the inactivated splice site. An example of such a molecule is kinetin, which can partially rescue splicing to a mutated IKBKAP 5′ss in familial dysautonomia35, 36 (Table 1, mutated splice sites).

Cryptic/pseudo splice sites

The creation of de novo cryptic splice sites or activation of pseudo splice sites are common consequences of disease-causing mutations. A cryptic splice site is one created by a mutation, whereas a pseudo site is a site with a weak match to consensus splice site which is activated as a result of a mutation in the authentic site or in regulatory splicing sequences8, 37. The consequences of these types of mutations as well as the potential approaches to compensate for the mutations are similar and thus, the terms should be considered interchangeable as we discuss the approaches to target them (Figure 1).

Cryptic or pseudo splice sites result in the inclusion of intronic sequences typically not included in the mature mRNA (pseudoexons). The resulting aberrant mRNA may have an altered reading frame or may code for a protein with amino acid deletions or additions. Frameshifts can result in PTCs and/or a complete alteration of the amino acid sequence encoded in the mRNA. This is a well-documented phenomenon and mutations in numerous humans genes lead to the use of cryptic splice sites and the inclusion of pseudoexons, resulting in disease37.

ASOs

ASOs are the most common therapeutic approach to correct splicing alterations caused by the creation of a cryptic splice site. ASOs can be designed to bind and thereby occupy the cryptic splice site, which redirects the spliceosome to the authentic splice site. Blocking cryptic 5′ss with ASOs has been used in several disease models to correct splicing (Table 1, cryptic splice sites). ASO-directed blocking of cryptic splice sites caused by mutations in HBB (β-globin), FKTN, LMNA, and CLC1 has been shown to rescue normal splicing in mouse models of β-thalassemia38–42, Fukuyama congenital muscular dystrophy43, Hutchinson-Gilford progeria44 and myotonic dystrophy45, respectively (Table 1, cryptic splice sites). Also, rescue of disease phenotype in a mouse model has been shown using ASOs targeting a mutation the USH1C gene that creates a cryptic 5′ss and causes Usher Syndrome. These ASOs have successfully corrected splicing and rescued congenital deafness and vestibular defects associated with the disease in vivo46.

Small Molecules

Small molecule compounds have also been identified that restore authentic splice site recognition, or prevent the recognition of pseduoexons. For example, the histone deacetylase inhibitor, sodium butyrate, promotes exon inclusion in CFTR, that causes cystic fibrosis, in cell lines carrying the 3849+10kbC>T mutation and restores functional CFTR channels 47 (Table 1, cryptic splice sites). The molecule appears to act by increasing expression of a subset of splicing factors.

Splicing regulatory sequence mutations

Splicing mutations that disrupt cis-acting regulatory sequences such as splicing enhancers and silencers can be difficult to identify and are often designated as missense mutations, or as single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), if located within exons. When these sequence elements are mutated, the recognition of authentic splice sites is affected, resulting in non-canonical exon skipping or pseudo splice site recognition (Figure 1b). Alternatively, de novo cis-acting regulatory sequences can also be generated by mutations. Once a mutation is determined to alter splicing regulatory sequence, a number of approaches can be considered to correct the splicing defect. Approaches can include blocking activated splice sites to balance the loss of the enhancer by identifying and targeting splicing silencers, or by restoring the enhancer or silencer regulation at the mutated site (Figure 2a).

ASOs

ASOs have been the primary tool used to correct splicing defects associated with the loss or creation of regulatory sequences such as splicing silencers and enhancers (Table 1, regulatory sequence mutations). For example, mutations that create binding sites for the splicing factor SRSF1 in the FGB or the GPR143 (OA1) genes cause cryptic splicing that causes afibrinogenemia 48 or ocular albinism 49, respectively. These cryptic sites have been blocked through direct ASO hybridization and to redirect splicing to the authentic splice site. Another SRSF1 site disrupted by a mutation in BRCA1 causes exon skipping, which promotes breast cancer. Bifunctional ASOs that replace the need for SRSF1 binding have also been designed to include an RS peptide sequence that mimics a functional RS domain of SRSF1, and in so doing, effectively restores exon recognition in the mutated BRCA1 gene17.

Small Molecules

Small molecule compounds, often function through interactions with splicing factors. Thus, they are also a viable option for the treatment of diseases caused by mutations that affect cis-acting regulatory sequences (Figure 2d). The small molecule kinetin, for example, can restore splicing of several exons in the NF1 gene that are skipped in neurofibromatosis as a result of mutations in cis-acting sequences 50 (Table 1, regulatory sequence mutations).

Deregulated alternative splicing

For the purposes of this review, disease-associated disruption of alternative splicing refers to any pathological alteration in the relative abundance of alternatively spliced mRNA isoforms. In these cases, the splicing defect is one that disrupts the balance of normally spliced transcripts as opposed to examples discussed earlier which consider mutations that result in the creation of de novo spliced mRNA that is not typically observed. Changes in alternative splicing can be caused by mutations within the sequence of the alternatively spliced gene transcript or in the absence of mutations within the genes. In the latter situation, it is often difficult to assign an exact cause of the change in alternative splicing. Possibilities include the malfunction of a signaling pathway or disruption of some other indirect regulatory event.

ASOs, Trans-splicing and Small Molecules

The utilization of RNA splicing-based approaches to alter spliced isoforms has been particularly successful in the development of therapeutics for spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). SMA patients have lost expression of the survival of motor neuron (SMN) protein transcripts from the SMN1 gene. An SMN1 paralog, SMN2, expresses SMN encoding transcripts. However, a silent mutation in exon 7 of the gene results in the preferential skipping of exon 7 thus generating a truncated and unstable protein. Promoting SMN2 exon 7 inclusion to restore full protein function has been a major focus of SMA therapeutic development51. Most of the tools discussed in this review have been used to manipulate exon 7 splicing in SMA, including ASOs, small molecule compounds and trans-splicing51. ASOs targeting different regions surrounding exon 7, both in the exon and flanking intron, have been developed12, 52–56. One ASO, ISIS-SMNrx, is now in clinical trails 54.

Many small molecules compounds have also been identified that increase the amount of SMN protein from the SMN2 gene in SMA51 (Table 1, deregulated alternative splicing). At least one of these compounds, the tetracycline derivative, PTK-SMA157, acts directly on the splicing reaction through an unknown target, most of these compounds alter splicing indirectly via changes in transcriptional activity or other unknown mechanisms as reviewed in Bebee et al. 51, 58(Table 1). Some of these molecules have progressed to clinical trials51.

Modulating the production of alternatively spliced isoforms for disease therapy has shown promise in other diseases including Alzhiemer’s disease (AD) and numerous cancers (Table 1, deregulated alternative splicing). An increase in MAPT exon 10 splicing is associated with AD and FTDP-17. A number of approaches are aimed at promoting exon 10 skipping to increase the production of the shorter isoform. Platforms include traditional and bifunctional ASOs11, 18, 59, trans-splicing60, and small molecules such the cardionic steroid, digitoxin, that promotes exon 10 skipping by altering expression of key splicing factors 22, 61(Figure 2). Likewise, a number of deregulated alternative splicing events associated with tumor progression have been the focus of ASO-based splicing redirection to promote splicing of anti-tumorigenic isoforms of genes such as BCL2L1 (BCL-X)18, 62–65, FGFR166, MCL-167, MDM268, PKM18, 69, MST1R (RON)70, and USP571 (Figure 3a). In cancer cells, where global aberrant alternative splicing is though to contribute to the oncogenic potential, small molecule compounds have also been identified that promote normalization of alternative splicing events as a potential therapy72, 73.

Induction of Aberrant Splicing

RNA processing can be targeted not only to correct the effects of mutations or deregulated splicing, as discussed above, but also to induce splicing events that do not normally occur. This approach has proven to be an effective and powerful way to deliberately alter or eliminate protein expression in ways that can be therapeutically valuable (Figure 3b,c).

Detrimental gene expression

In some diseases, therapeutic benefit can be achieved by eliminating an mRNA isoform and the encoded protein altogether. In this case, the goal of inducing aberrant splicing is to cause transcript degradation and/or protein truncation yielding no protein or a nonfunctional protein, respectively. The exclusion of specific exons from a transcript can cause a frame-shift and introduce a PTC into the transcript if the exons flanking the skipped exon are not in the same reading frame. An induced PTC is expected to induce the nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) pathway and result in the degradation of the transcript thus preventing protein production (Figure 3b).

ASOs

ASOs have been used effectively to achieve this so-called forced splicing induced nonsense mediated decay (FSD-NMD)74–76. This approach has been used to down-regulate STAT374, HNRNPH175 and KDR76, 77 to mitigate tumor progression, malignancy and angiogenesis. FSD-NMD has also been used in muscle wasting disease and spinocerebellar ataxia type 1 to cause degradation of MSTN78 and ATXN179, respectively (Table 1, detrimental gene expression).

To determine whether knock-down of gene expression using FSD-NMD or splicing redirection will have the greatest therapeutic potential, the two processes can be compared. For example, by comparing these two approaches for STAT374, and KDR76, mentioned above, splicing redirection was more effective at blocking cell proliferation than the complete knock-down. The greater effectiveness was achieved due to the dual effects of eliminating a pathogenic RNA isoform and increasing a beneficial RNA isoform.

In some cases redirection of splicing to an aberrant isoform that is not normally generated from a gene transcript can be an effective means to eliminate a detrimental RNA isoform that is implicated in disease (Table 1, detrimental gene expression). Some of the more advanced studies, showing promise in animal models, include ASOs targeting TNFRSF1B80 for the treatment of inflammatory disease, and FLT181 as a cancer therapy.

Small Molecules

Induction of aberrant splicing for disease benefit has also been achieved using small molecules. Large-scale compound screening has identified many small molecules that regulate splicing, per se, rather than individual genes (Figure 3a). These molecules have been applied to the treatment of cancers. In general, these compounds are non-specific, altering the splicing of multiple genes. For example, the small molecules, spliceostatin A (SSA; a derivative of FR901464) and pladienolide B (E7107) bind the SF3B spliceosomal complex, an essential component of the U2 snRNP82, 83 (Figure, 2d, Table 1, detrimental gene expression). These small molecules and the closely related derivatives, meayamycin and herboxidiene (GEX1A), act as general inhibitors of splicing82–85. However, SSA as well as analogues of SSA, sudemycins, have also been shown to modulate alternative splicing86, 87. One of these inhibitors, E7107, has entered phase I clinical trials83. However, the value of SF3B inhibitors as a therapeutic is not clear because haploinsufficiency of SF3B1, a component of the SF3B complex, causes cancer88, and at least one chemical analog of spliceostatin A, meayamycin, induces abnormalities in normal cells89. Other molecules, such as histone deacetylase inhibitors90 and C6 pyridinium ceramide91, can also induce changes in alternative splicing by altering the expression or activity of specific splicing factors (Table 1). All of these small molecules serve to alter alternative splicing and therefore disrupt the metabolic and proliferative activities of cancerous cells (Table 1, detrimental gene expression).

RNA Reframing

Nonsense and small deletions/insertions can create PTCs or cause frame-shifts, both of which lead to the production of a truncated protein or the loss of gene expression due to nonsense-mediated decay. In cases where the flanking introns are in phase, skipping the exon with the PTC or frameshift mutation will produce an mRNA encoding an in-frame or reframed protein that is partially or fully functional (Figure 3c). Rescuing gene expression in this way has been accomplished using a number of tools including ASOs targeted to the splice sites, small molecule effectors of exon skipping and trans-splicing. Promising results from these frame-correcting approaches have been achieved for dystrophic epidermolysis bullosa92, 93, and Miyoshi myopathy94 (Table 1, reframing RNA).

One of the most actively pursued ASO-based therapeutic has been for the treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD). Nonsense mutations are common in DMD and ASOs designed to skip a variety of exons are being developed95–104. The most advanced ASO-based therapies to treat DMD, PRO051 (GSK 2402968)99, AVI-4658 (Eteplirsen)95, 97 and PRO044101, 105 are currently in phase II clinical trials. PRO051 and AVI-4648 both induce the skipping of exon 51, which restores the reading frame of dystrophin for patients with deletions of either exon(s) 50 or 52; or deletions that span exons 45–50, or 48–50, which represents a patient population that accounts for 13% of DMD cases95, 99. Similarly, PRO044 skips exon 44, which can restore the dystrophin reading frame in patients with deletions of either exons 43, 45, or deletions spanning exons 38–43, 40–43, 42–43, or 45–54, which account for 6% of DMD cases105.

CONCLUSION

This review provides an overview of the different types of aberrant splicing that can occur as a result of mutations or other cellular defects and highlights approaches that can be used to target and correct deficiencies by manipulating RNA splicing. Approaches that induce aberrant splicing for disease therapy are also considered. We have made an effort to be thorough, but acknowledge that this account is by no means comprehensive and we regret the omission of other important work that is not included because of space limitations. Given the success of RNA-based approaches, there will likely be an increasing number of diseases that will benefit from splice-altering therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Alicia Case and Anthony Hinrich for their critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Hearing Health Foundation, Midwest Eye-Banks, Capita Foundation, National Organization for Hearing Research Foundation and NIH NS069759 to MLH, NIH 1F31NS076237 to MAH, and the Schweppe Research Foundation and American Cancer Society, Illinois Division, Research Grant 189903 to DMD.

Contributor Information

Mallory A. Havens, Department of Cell Biology and Anatomy, Chicago Medical School, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science. North Chicago, IL, 60064, USA. No conflicts of interest

Dominik M. Duelli, Department of Cellular and Molecular Pharmacology, Chicago Medical School, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science, North Chicago, IL, 60064, USA. No conflicts of interest

Michelle L. Hastings, Email: Michelle.Hastings@rosalindfranklin.edu, Department of Cell Biology and Anatomy, Chicago Medical School, Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science. North Chicago, IL, 60064, USA, Phone: 847-578-8517 Fax: 847-578-3253. No conflicts of interest

References

- 1.De Conti L, Baralle M, Buratti E. Exon and intron definition in pre-mRNA splicing. Wiley interdisciplinary reviews. RNA. 2012 doi: 10.1002/wrna.1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wahl MC, Will CL, Luhrmann R. The spliceosome: design principles of a dynamic RNP machine. Cell. 2009;136:701–718. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nilsen TW, Graveley BR. Expansion of the eukaryotic proteome by alternative splicing. Nature. 2010;463:457–463. doi: 10.1038/nature08909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kim E, Goren A, Ast G. Alternative splicing: current perspectives. BioEssays : news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2008;30:38–47. doi: 10.1002/bies.20692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelemen O, Convertini P, Zhang Z, Wen Y, Shen M, Falaleeva M, Stamm S. Function of alternative splicing. Gene. 2012 doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.07.083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lim KH, Ferraris L, Filloux ME, Raphael BJ, Fairbrother WG. Using positional distribution to identify splicing elements and predict pre-mRNA processing defects in human genes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:11093–11098. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1101135108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sterne-Weiler T, Howard J, Mort M, Cooper DN, Sanford JR. Loss of exon identity is a common mechanism of human inherited disease. Genome research. 2011;21:1563–1571. doi: 10.1101/gr.118638.110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roca X, Sachidanandam R, Krainer AR. Intrinsic differences between authentic and cryptic 5′ splice sites. Nucleic acids research. 2003;31:6321–6333. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stenson PD, Mort M, Ball EV, Howells K, Phillips AD, Thomas NS, Cooper DN. The Human Gene Mutation Database: 2008 update. Genome medicine. 2009;1:13. doi: 10.1186/gm13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bennett CF, Swayze EE. RNA targeting therapeutics: molecular mechanisms of antisense oligonucleotides as a therapeutic platform. Annual review of pharmacology and toxicology. 2010;50:259–293. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.010909.105654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peacey E, Rodriguez L, Liu Y, Wolfe MS. Targeting a pre-mRNA structure with bipartite antisense molecules modulates tau alternative splicing. Nucleic acids research. 2012;40:9836–9849. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Porensky PN, Mitrpant C, McGovern VL, Bevan AK, Foust KD, Kaspar BK, Wilton SD, Burghes AH. A single administration of morpholino antisense oligomer rescues spinal muscular atrophy in mouse. Human molecular genetics. 2012;21:1625–1638. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hua Y, Sahashi K, Rigo F, Hung G, Horev G, Bennett CF, Krainer AR. Peripheral SMN restoration is essential for long-term rescue of a severe spinal muscular atrophy mouse model. Nature. 2011;478:123–126. doi: 10.1038/nature10485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skordis LA, Dunckley MG, Yue B, Eperon IC, Muntoni F. Bifunctional antisense oligonucleotides provide a trans-acting splicing enhancer that stimulates SMN2 gene expression in patient fibroblasts. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4114–4119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0633863100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Osman EY, Yen PF, Lorson CL. Bifunctional RNAs targeting the intronic splicing silencer N1 increase SMN levels and reduce disease severity in an animal model of spinal muscular atrophy. Mol Ther. 2012;20:119–126. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyer K, Marquis J, Trub J, Nlend Nlend R, Verp S, Ruepp MD, Imboden H, Barde I, Trono D, Schumperli D. Rescue of a severe mouse model for spinal muscular atrophy by U7 snRNA-mediated splicing modulation. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:546–555. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cartegni L, Krainer AR. Correction of disease-associated exon skipping by synthetic exon-specific activators. Nature structural biology. 2003;10:120–125. doi: 10.1038/nsb887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rigo F, Hua Y, Chun SJ, Prakash TP, Krainer AR, Bennett CF. Synthetic oligonucleotides recruit ILF2/3 to RNA transcripts to modulate splicing. Nature chemical biology. 2012;8:555–561. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wally V, Murauer EM, Bauer JW. Spliceosome-mediated trans-splicing: the therapeutic cut and paste. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2012;132:1959–1966. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schmid F, Hiller T, Korner G, Glaus E, Berger W, Neidhardt J. A gene therapeutic approach to correct splice defects with modified U1 and U6 snRNPs. Human gene therapy. 2012 doi: 10.1089/hum.2012.110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Arslan AD, He X, Wang M, Rumschlag-Booms E, Rong L, Beck WT. A High-Throughput Assay to Identify Small-Molecule Modulators of Alternative Pre-mRNA Splicing. Journal of biomolecular screening. 2012 doi: 10.1177/1087057112459901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stoilov P, Lin CH, Damoiseaux R, Nikolic J, Black DL. A high-throughput screening strategy identifies cardiotonic steroids as alternative splicing modulators. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:11218–11223. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801661105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Warf MB, Nakamori M, Matthys CM, Thornton CA, Berglund JA. Pentamidine reverses the splicing defects associated with myotonic dystrophy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:18551–18556. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903234106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kierlin-Duncan MN, Sullenger BA. Using 5′-PTMs to repair mutant beta-globin transcripts. RNA. 2007;13:1317–1327. doi: 10.1261/rna.525607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartmann L, Neveling K, Borkens S, Schneider H, Freund M, Grassman E, Theiss S, Wawer A, Burdach S, Auerbach AD, et al. Correct mRNA processing at a mutant TT splice donor in FANCC ameliorates the clinical phenotype in patients and is enhanced by delivery of suppressor U1 snRNAs. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;87:480–493. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fernandez Alanis E, Pinotti M, Dal Mas A, Balestra D, Cavallari N, Rogalska ME, Bernardi F, Pagani F. An exon-specific U1 small nuclear RNA (snRNA) strategy to correct splicing defects. Human molecular genetics. 2012;21:2389–2398. doi: 10.1093/hmg/dds045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pinotti M, Rizzotto L, Balestra D, Lewandowska MA, Cavallari N, Marchetti G, Bernardi F, Pagani F. U1-snRNA-mediated rescue of mRNA processing in severe factor VII deficiency. Blood. 2008;111:2681–2684. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schmid F, Glaus E, Barthelmes D, Fliegauf M, Gaspar H, Nurnberg G, Nurnberg P, Omran H, Berger W, Neidhardt J. U1 snRNA-mediated gene therapeutic correction of splice defects caused by an exceptionally mild BBS mutation. Human mutation. 2011;32:815–824. doi: 10.1002/humu.21509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanchez-Alcudia R, Perez B, Perez-Cerda C, Ugarte M, Desviat LR. Overexpression of adapted U1snRNA in patients’ cells to correct a 5′ splice site mutation in propionic acidemia. Molecular genetics and metabolism. 2011;102:134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tanner G, Glaus E, Barthelmes D, Ader M, Fleischhauer J, Pagani F, Berger W, Neidhardt J. Therapeutic strategy to rescue mutation-induced exon skipping in rhodopsin by adaptation of U1 snRNA. Human mutation. 2009;30:255–263. doi: 10.1002/humu.20861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Glaus E, Schmid F, Da Costa R, Berger W, Neidhardt J. Gene therapeutic approach using mutation-adapted U1 snRNA to correct a RPGR splice defect in patient-derived cells. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2011;19:936–941. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yokota T, Hoffman E, Takeda S. Antisense oligo-mediated multiple exon skipping in a dog model of duchenne muscular dystrophy. Methods in molecular biology. 2011;709:299–312. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61737-982-6_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bish LT, Sleeper MM, Forbes SC, Wang B, Reynolds C, Singletary GE, Trafny D, Morine KJ, Sanmiguel J, Cecchini S, et al. Long-term restoration of cardiac dystrophin expression in golden retriever muscular dystrophy following rAAV6-mediated exon skipping. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2012;20:580–589. doi: 10.1038/mt.2011.264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uchikawa H, Fujii K, Kohno Y, Katsumata N, Nagao K, Yamada M, Miyashita T. U7 snRNA-mediated correction of aberrant splicing caused by activation of cryptic splice sites. Journal of human genetics. 2007;52:891–897. doi: 10.1007/s10038-007-0192-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Axelrod FB, Liebes L, Gold-Von Simson G, Mendoza S, Mull J, Leyne M, Norcliffe-Kaufmann L, Kaufmann H, Slaugenhaupt SA. Kinetin improves IKBKAP mRNA splicing in patients with familial dysautonomia. Pediatric research. 2011;70:480–483. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31822e1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hims MM, Ibrahim EC, Leyne M, Mull J, Liu L, Lazaro C, Shetty RS, Gill S, Gusella JF, Reed R, et al. Therapeutic potential and mechanism of kinetin as a treatment for the human splicing disease familial dysautonomia. Journal of molecular medicine. 2007;85:149–161. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0137-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dhir A, Buratti E. Alternative splicing: role of pseudoexons in human disease and potential therapeutic strategies. The FEBS journal. 2010;277:841–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07520.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.El-Beshlawy A, Mostafa A, Youssry I, Gabr H, Mansour IM, El-Tablawy M, Aziz M, Hussein IR. Correction of aberrant pre-mRNA splicing by antisense oligonucleotides in beta-thalassemia Egyptian patients with IVSI-110 mutation. Journal of pediatric hematology/oncology. 2008;30:281–284. doi: 10.1097/MPH.0b013e3181639afe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lacerra G, Sierakowska H, Carestia C, Fucharoen S, Summerton J, Weller D, Kole R. Restoration of hemoglobin A synthesis in erythroid cells from peripheral blood of thalassemic patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97:9591–9596. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.17.9591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suwanmanee T, Sierakowska H, Fucharoen S, Kole R. Repair of a splicing defect in erythroid cells from patients with beta-thalassemia/HbE disorder. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2002;6:718–726. doi: 10.1006/mthe.2002.0805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Svasti S, Suwanmanee T, Fucharoen S, Moulton HM, Nelson MH, Maeda N, Smithies O, Kole R. RNA repair restores hemoglobin expression in IVS2-654 thalassemic mice. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:1205–1210. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812436106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vacek MM, Ma H, Gemignani F, Lacerra G, Kafri T, Kole R. High-level expression of hemoglobin A in human thalassemic erythroid progenitor cells following lentiviral vector delivery of an antisense snRNA. Blood. 2003;101:104–111. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-06-1869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Taniguchi-Ikeda M, Kobayashi K, Kanagawa M, Yu CC, Mori K, Oda T, Kuga A, Kurahashi H, Akman HO, DiMauro S, et al. Pathogenic exon-trapping by SVA retrotransposon and rescue in Fukuyama muscular dystrophy. Nature. 2011;478:127–131. doi: 10.1038/nature10456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osorio FG, Navarro CL, Cadinanos J, Lopez-Mejia IC, Quiros PM, Bartoli C, Rivera J, Tazi J, Guzman G, Varela I, et al. Splicing-directed therapy in a new mouse model of human accelerated aging. Science translational medicine. 2011;3:106ra107. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3002847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wheeler TM, Lueck JD, Swanson MS, Dirksen RT, Thornton CA. Correction of ClC-1 splicing eliminates chloride channelopathy and myotonia in mouse models of myotonic dystrophy. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2007;117:3952–3957. doi: 10.1172/JCI33355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lentz JJ, Jodelka FM, Hinrich AJ, McCaffrey KE, Farris HE, Spalitta MJ, Bazan NG, Duelli DM, Rigo F, Hastings ML. Rescue of hearing and vestibular function by antisense oligonucleotides in a mouse model of human deafness. Nature medicine. 2013 doi: 10.1038/nm.3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nissim-Rafinia M, Aviram M, Randell SH, Shushi L, Ozeri E, Chiba-Falek O, Eidelman O, Pollard HB, Yankaskas JR, Kerem B. Restoration of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator function by splicing modulation. EMBO reports. 2004;5:1071–1077. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Davis RL, Homer VM, George PM, Brennan SO. A deep intronic mutation in FGB creates a consensus exonic splicing enhancer motif that results in afibrinogenemia caused by aberrant mRNA splicing, which can be corrected in vitro with antisense oligonucleotide treatment. Human mutation. 2009;30:221–227. doi: 10.1002/humu.20839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vetrini F, Tammaro R, Bondanza S, Surace EM, Auricchio A, De Luca M, Ballabio A, Marigo V. Aberrant splicing in the ocular albinism type 1 gene (OA1/GPR143) is corrected in vitro by morpholino antisense oligonucleotides. Human mutation. 2006;27:420–426. doi: 10.1002/humu.20303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pros E, Fernandez-Rodriguez J, Benito L, Ravella A, Capella G, Blanco I, Serra E, Lazaro C. Modulation of aberrant NF1 pre-mRNA splicing by kinetin treatment. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2010;18:614–617. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bebee TW, Gladman JT, Chandler DS. Splicing regulation of the survival motor neuron genes and implications for treatment of spinal muscular atrophy. Frontiers in bioscience : a journal and virtual library. 2010;15:1191–1204. doi: 10.2741/3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Geib T, Hertel KJ. Restoration of full-length SMN promoted by adenoviral vectors expressing RNA antisense oligonucleotides embedded in U7 snRNAs. PloS one. 2009;4:e8204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hua Y, Vickers TA, Baker BF, Bennett CF, Krainer AR. Enhancement of SMN2 exon 7 inclusion by antisense oligonucleotides targeting the exon. PLoS biology. 2007;5:e73. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Passini MA, Bu J, Richards AM, Kinnecom C, Sardi SP, Stanek LM, Hua Y, Rigo F, Matson J, Hung G, et al. Antisense oligonucleotides delivered to the mouse CNS ameliorate symptoms of severe spinal muscular atrophy. Science translational medicine. 2011;3:72ra18. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3001777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Singh NN, Shishimorova M, Cao LC, Gangwani L, Singh RN. A short antisense oligonucleotide masking a unique intronic motif prevents skipping of a critical exon in spinal muscular atrophy. RNA biology. 2009;6:341–350. doi: 10.4161/rna.6.3.8723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams JH, Schray RC, Patterson CA, Ayitey SO, Tallent MK, Lutz GJ. Oligonucleotide-mediated survival of motor neuron protein expression in CNS improves phenotype in a mouse model of spinal muscular atrophy. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2009;29:7633–7638. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0950-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hastings ML, Berniac J, Liu YH, Abato P, Jodelka FM, Barthel L, Kumar S, Dudley C, Nelson M, Larson K, et al. Tetracyclines that promote SMN2 exon 7 splicing as therapeutics for spinal muscular atrophy. Science translational medicine. 2009;1:5ra12. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang Z, Kelemen O, van Santen MA, Yelton SM, Wendlandt AE, Sviripa VM, Bollen M, Beullens M, Urlaub H, Luhrmann R, et al. Synthesis and characterization of pseudocantharidins, novel phosphatase modulators that promote the inclusion of exon 7 into the SMN (survival of motoneuron) pre-mRNA. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2011;286:10126–10136. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.183970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kalbfuss B, Mabon SA, Misteli T. Correction of alternative splicing of tau in frontotemporal dementia and parkinsonism linked to chromosome 17. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:42986–42993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105113200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rodriguez-Martin T, Anthony K, Garcia-Blanco MA, Mansfield SG, Anderton BH, Gallo JM. Correction of tau mis-splicing caused by FTDP-17 MAPT mutations by spliceosome-mediated RNA trans-splicing. Human molecular genetics. 2009;18:3266–3273. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Anderson ES, Lin CH, Xiao X, Stoilov P, Burge CB, Black DL. The cardiotonic steroid digitoxin regulates alternative splicing through depletion of the splicing factors SRSF3 and TRA2B. RNA. 2012;18:1041–1049. doi: 10.1261/rna.032912.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bauman JA, Li SD, Yang A, Huang L, Kole R. Anti-tumor activity of splice-switching oligonucleotides. Nucleic acids research. 2010;38:8348–8356. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mercatante DR, Mohler JL, Kole R. Cellular response to an antisense-mediated shift of Bcl-x pre-mRNA splicing and antineoplastic agents. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:49374–49382. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209236200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Villemaire J, Dion I, Elela SA, Chabot B. Reprogramming alternative pre-messenger RNA splicing through the use of protein-binding antisense oligonucleotides. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:50031–50039. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308897200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wilusz JE, Devanney SC, Caputi M. Chimeric peptide nucleic acid compounds modulate splicing of the bcl-x gene in vitro and in vivo. Nucleic acids research. 2005;33:6547–6554. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bruno IG, Jin W, Cote GJ. Correction of aberrant FGFR1 alternative RNA splicing through targeting of intronic regulatory elements. Human molecular genetics. 2004;13:2409–2420. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddh272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Shieh JJ, Liu KT, Huang SW, Chen YJ, Hsieh TY. Modification of alternative splicing of Mcl-1 pre-mRNA using antisense morpholino oligonucleotides induces apoptosis in basal cell carcinoma cells. The Journal of investigative dermatology. 2009;129:2497–2506. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shiraishi T, Eysturskarth J, Nielsen PE. Modulation of mdm2 pre-mRNA splicing by 9-aminoacridine-PNA (peptide nucleic acid) conjugates targeting intron-exon junctions. BMC cancer. 2010;10:342. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang Z, Jeon HY, Rigo F, Bennett CF, Krainer AR. Manipulation of PK-M mutually exclusive alternative splicing by antisense oligonucleotides. Open biology. 2012;2:120133. doi: 10.1098/rsob.120133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ghigna C, De Toledo M, Bonomi S, Valacca C, Gallo S, Apicella M, Eperon I, Tazi J, Biamonti G. Pro-metastatic splicing of Ron proto-oncogene mRNA can be reversed: therapeutic potential of bifunctional oligonucleotides and indole derivatives. RNA biology. 2010;7:495–503. doi: 10.4161/rna.7.4.12744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Izaguirre DI, Zhu W, Hai T, Cheung HC, Krahe R, Cote GJ. PTBP1-dependent regulation of USP5 alternative RNA splicing plays a role in glioblastoma tumorigenesis. Molecular carcinogenesis. 2012;51:895–906. doi: 10.1002/mc.20859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chang JG, Yang DM, Chang WH, Chow LP, Chan WL, Lin HH, Huang HD, Chang YS, Hung CH, Yang WK. Small molecule amiloride modulates oncogenic RNA alternative splicing to devitalize human cancer cells. PloS one. 2011;6:e18643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Chang WH, Liu TC, Yang WK, Lee CC, Lin YH, Chen TY, Chang JG. Amiloride modulates alternative splicing in leukemic cells and resensitizes Bcr-AblT315I mutant cells to imatinib. Cancer research. 2011;71:383–392. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zammarchi F, de Stanchina E, Bournazou E, Supakorndej T, Martires K, Riedel E, Corben AD, Bromberg JF, Cartegni L. Antitumorigenic potential of STAT3 alternative splicing modulation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2011;108:17779–17784. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108482108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lefave CV, Squatrito M, Vorlova S, Rocco GL, Brennan CW, Holland EC, Pan YX, Cartegni L. Splicing factor hnRNPH drives an oncogenic splicing switch in gliomas. The EMBO journal. 2011;30:4084–4097. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vorlova S, Rocco G, Lefave CV, Jodelka FM, Hess K, Hastings ML, Henke E, Cartegni L. Induction of antagonistic soluble decoy receptor tyrosine kinases by intronic polyA activation. Molecular cell. 2011;43:927–939. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Uehara H, Cho Y, Simonis J, Cahoon J, Archer B, Luo L, Das SK, Singh N, Ambati J, Ambati BK. Dual suppression of hemangiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis by splice-shifting morpholinos targeting vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (KDR) FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2012 doi: 10.1096/fj.12-213835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kang JK, Malerba A, Popplewell L, Foster K, Dickson G. Antisense-induced myostatin exon skipping leads to muscle hypertrophy in mice following octa-guanidine morpholino oligomer treatment. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2011;19:159–164. doi: 10.1038/mt.2010.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gao Y, Zu T, Low WC, Orr HT, McIvor RS. Antisense RNA sequences modulating the ataxin-1 message: molecular model of gene therapy for spinocerebellar ataxia type 1, a dominant-acting unstable trinucleotide repeat disease. Cell transplantation. 2008;17:723–734. doi: 10.3727/096368908786516729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Graziewicz MA, Tarrant TK, Buckley B, Roberts J, Fulton L, Hansen H, Orum H, Kole R, Sazani P. An endogenous TNF-alpha antagonist induced by splice-switching oligonucleotides reduces inflammation in hepatitis and arthritis mouse models. Molecular therapy : the journal of the American Society of Gene Therapy. 2008;16:1316–1322. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Owen LA, Uehara H, Cahoon J, Huang W, Simonis J, Ambati BK. Morpholino-mediated increase in soluble Flt-1 expression results in decreased ocular and tumor neovascularization. PloS one. 2012;7:e33576. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kaida D, Motoyoshi H, Tashiro E, Nojima T, Hagiwara M, Ishigami K, Watanabe H, Kitahara T, Yoshida T, Nakajima H, et al. Spliceostatin A targets SF3b and inhibits both splicing and nuclear retention of pre-mRNA. Nature chemical biology. 2007;3:576–583. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kotake Y, Sagane K, Owa T, Mimori-Kiyosue Y, Shimizu H, Uesugi M, Ishihama Y, Iwata M, Mizui Y. Splicing factor SF3b as a target of the antitumor natural product pladienolide. Nature chemical biology. 2007;3:570–575. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Furumai R, Uchida K, Komi Y, Yoneyama M, Ishigami K, Watanabe H, Kojima S, Yoshida M. Spliceostatin A blocks angiogenesis by inhibiting global gene expression including VEGF. Cancer science. 2010;101:2483–2489. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01686.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gao Y, Vogt A, Forsyth CJ, Koide K. Comparison of Splicing Factor 3b Inhibitors in Human Cells. Chembiochem : a European journal of chemical biology. 2012 doi: 10.1002/cbic.201200558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Corrionero A, Minana B, Valcarcel J. Reduced fidelity of branch point recognition and alternative splicing induced by the anti-tumor drug spliceostatin A. Genes & development. 2011;25:445–459. doi: 10.1101/gad.2014311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fan L, Lagisetti C, Edwards CC, Webb TR, Potter PM. Sudemycins, novel small molecule analogues of FR901464, induce alternative gene splicing. ACS chemical biology. 2011;6:582–589. doi: 10.1021/cb100356k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Visconte V, Rogers HJ, Singh J, Barnard J, Bupathi M, Traina F, McMahon J, Makishima H, Szpurka H, Jankowska A, et al. SF3B1 haploinsufficiency leads to formation of ring sideroblasts in myelodysplastic syndromes. Blood. 2012;120:3173–3186. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-05-430876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Albert BJ, McPherson PA, O’Brien K, Czaicki NL, Destefino V, Osman S, Li M, Day BW, Grabowski PJ, Moore MJ, et al. Meayamycin inhibits pre-messenger RNA splicing and exhibits picomolar activity against multidrug-resistant cells. Molecular cancer therapeutics. 2009;8:2308–2318. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-09-0051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Puppin C, Passon N, Franzoni A, Russo D, Damante G. Histone deacetylase inhibitors control the transcription and alternative splicing of prohibitin in thyroid tumor cells. Oncology reports. 2011;25:393–397. doi: 10.3892/or.2010.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]