Abstract

Objective

To compare completion rates of colorectal cancer screening tests within a Health Maintenance Organization before and after widespread adoption of a fecal immunochemical test (FIT).

Study Design

Retrospective cohort study

Methods

Using electronic medical records of 113,901 patients eligible for colorectal cancer screening, we examined screening test completion during two successive time periods among those who received an automated call for screening outreach. The time periods were: (1) The “gFOBT era,” a fifteen-month period during which only guaiac fecal occult blood testing was routinely offered through the automated call, and (2) A nine-month “FIT era,” when only a new fecal immunochemical test was routinely offered. In addition to analyzing completion rates, we analyzed the impact of practice-level variables and patient-level variables on overall screening completion during the two different observation periods.

Results

The change from gFOBT to FIT in an integrated care delivery system increased the likelihood of screening completion by 9.5% overall, and the likelihood of screening with a fecal test by 8.9%. The greatest gains in screening completion with FIT were among women and elderly patients. Completion of FIT was not as strongly associated with medical office visits or with having a primary care provider as was screening with gFOBT.

Conclusions

Adoption of a FIT within an integrated care system increased completion of colon cancer screening tests within a 9-month assessment period, compared to a previous 15-month gFOBT era. Higher completion rates of the FIT may allow for more effective dissemination of programs to increase colorectal cancer screening through centralized outreach programs.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States, and affects men and women almost equally.(1-3) The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommends screening with any of three options, including fecal testing, flexible sigmoidoscopy, or colonoscopy. Screening for CRC with fecal occult blood testing done annually or biennially has been shown to decrease mortality from colorectal cancer 15-33%, primarily through detection of early stage cancers.(4-9) Guaiac fecal occult blood testing (gFOBT) has a known positive balance of benefit and risk in screening populations, is the least expensive screening method, and is the preferred method of screening in 30-55% of patients.(10-12) However, gFOBT has limitations in the areas of test adherence and test performance because testing requires dietary and medication restrictions during the three days that three separate stool samples are collected, a cumbersome protocol which can interfere with test completion.(13)

While adherence to test completion in the initial round of screening with gFOBT in three large randomized trials was 59-67%,(5-7) smaller-scale studies have demonstrated lower one-time screening completion rates with gFOBT of 25-30%.(14;15) Retaining patients in annual or biennial gFOBT screening programs has proven challenging, with observed rescreen rates of approximately 50% on a second round.(9;16) Fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) may improve upon these rates. Previous randomized studies have shown that adherence to one-time completion of 1-sample or 2-sample FIT is 10-12% greater than adherence to gFOBT and that sensitivity of FIT is equal to or greater than FOBT.(14;15;17-19). A single (3-sample) guaiac FOBT detects about 12-38% of cancers,(20-22) whereas a 1-sample FIT detects 25-69% of cancers,(22-24) and a 3-sample FIT detects 66-92% of cancers.(22;24-27) As a result, in 2008 multiple professional societies endorsed the use of four types of FITs for colorectal cancer screening as a replacement for guaiac FOBT in the United States.(1;28)

However, it remains unclear to what extent a transition from gFOBT to FIT will improve screening test completion in large community-based populations and which specific populations may benefit the most. We capitalized on a natural experiment by analyzing completion rates before and after the change from gFOBT to FIT.

Methods

The protocol for this study was approved by the Institutional Review Board within the study health maintenance organization (HMO).

Study site and data sources

The study was conducted at Kaiser Permanente Northwest (KPNW), a not-for-profit HMO in the Pacific Northwest with about 485,000 members. KPNW's membership is similar to the local insured community.(29) Electronic records and a patient survey described below provided clinician and patient data.

KPNW maintains a CRC screening clinical practice guideline based upon the recommendations of the USPSTF. Each of the USPSTF-recommended CRC screening modalities is a covered benefit, although fecal testing is encouraged in lower risk individuals. The study site has had an automated call CRC reminder program in place since January 2008; details of the patient selection process for outreach and of the automated call have been published. (30) This program utilizes an automated telephone call to contact patients and offer them a fecal test. Each month, approximately 5,000 eligible HMO members receive this call, with the option to request that a fecal test be sent to their home. Included in the mailed packets are the test, instructions, and a card stock envelope addressed to the KPNW laboratory for return. Those who request the test but do not complete it within six weeks receive up to two reminder phone calls, six weeks apart.

In April of 2009, KPNW switched from sending the three-sample gFOBT to sending a single sample FIT that required no dietary or medication restrictions, the FIT OC-Micro (Polymedco, Cortland Manor, NY), to eligible patients through the outreach program.

Study design overview

The retrospective cohort study examined colorectal cancer screening test completion among those receiving an automated call (ATC) during two successive time periods: (1) The “gFOBT era,” a fifteen-month period during which the guaiac FOBT was routinely offered through ATC outreach, and (2) A nine month “FIT era.” We also analyzed the impact of practice-level variables (e.g., primary care provider assignment, primary-care utilization, specialty-care utilization) and patient-level variables (e.g., age, gender, number of medications, body mass index, length) on overall screening completion during the two different observation periods.

Additionally, we distributed a survey to 2,000 patients who received an ATC during one or both time periods. This survey was designed to understand the barriers and facilitators that patients encountered in their efforts to complete colorectal cancer screening. For the purposes of this analysis, we discuss the specific answers among only those respondents who answered about both tests, because they had had prior experience with each type of fecal test.

Study populations

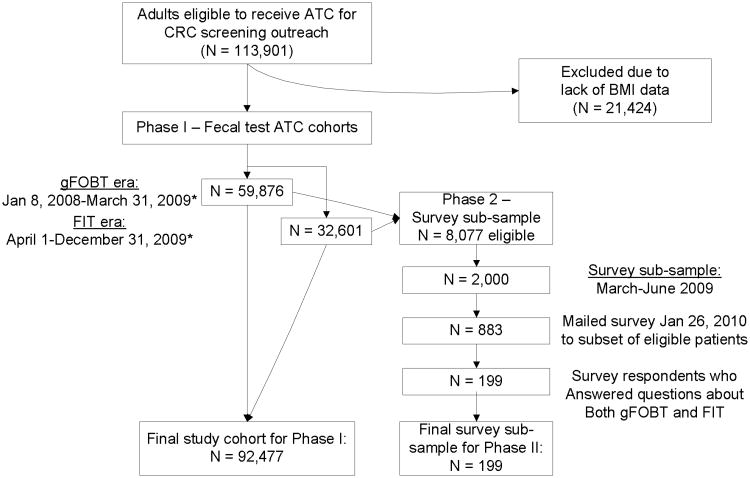

This retrospective cohort study was conducted in two phases. Figure 1 outlines the study population flow.

Figure 1. Study population flow: Cohorts receiving automated telephone call (ATC) reminder program and survey subsample.

*20% of patients (N = 18,508) were in both eras

Cohort population

The cohort consisted of HMO members aged 50–80 who were overdue for CRC screening at the beginning of each month of an observation period, and received an automated telephone call from the CRC screening outreach program at KPNW.

We utilized two observation periods. (1) The “gFOBT era,” a fifteen-month period during which the guaiac FOBT was routinely offered through ATC outreach, from January 1, 2008 thru March 31st, 2009 (n = 59,876). (2) A corresponding “FIT era” from April 1, 2009 through December 31st, 2009 (n = 32,601), excluding a single month (September 2009) in which KPNW was piloting a different type of ATC vendor.

Survey sample

A group of patients received a survey about colorectal cancer screening and answered questions about their experiences with both gFOBT and FIT. Patients eligible to receive the survey included HMO members who had received an automated telephone call for CRC screening between March and June 2009, had a primary care provider (PCP), and did not have a diagnosis of dementia in the EMR. From this population of 8,077, we mailed a random sample of 2,000 adults the survey; of this population, 1,816 (90.8%) were contacted. Reasons for non-contact included: incorrect phone number and/or address. 48.6% (N = 883) responded. We then selected survey respondents (N = 199) who had previously received both types of fecal tests (gFOBT and FIT), and analyzed their responses to questions about barriers and facilitators of fecal test completion.

Survey Design

The goal of the survey was to better understand the barriers and facilitators that patients encounter in their efforts to complete colorectal cancer screening. We utilized questions both from known validated prior questionnaires and questions we designed that were reflective of issues that emerged from four individual patient interviews. Interviewed patients were selected from lists of patients of primary care providers at KPNW who had either the highest screening rates or the lowest screening rates. All four patients who agreed to be interviewed had completed screening. Two had higher-screening-rate PCPs and two had lower-screening-rate PCPs. Interviewees shared their beliefs about and knowledge of colorectal cancer and their perceived individual risk for cancer. Domains of the questionnaire included validated questions about beliefs, worries, and knowledge about CRC screening,(31-36) experiences with specific CRC screening tests, experiences with health-care providers and members of the health care team,(37;38)and perceived barriers and facilitators to CRC screening completion.(13;39-42)

A subset of survey respondents (N = 199) answered specific questions about both gFOBT and FIT, indicating that they had received each test previously and had intended to complete (if had not actually completed) each of them. These questions asked respondents to use a Likert scale, with 1 indicating strong agreement and 5 indicating strong disagreement, to answer questions about specific test perceptions and experiences of gFOBT and FIT (see Table 4 below).

Table 4. Proportions of respondents answering “agree” or “strongly agree” to questions about gFOBT and FIT, respectively, with chi-square analysis of difference between proportions.

| Question | gFOBT | FIT | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| a. The instructions are easy to follow | 64.3 | 81.4 | <.001 |

| b. The stool test is unpleasant to complete | 53.3 | 40.2 | .001 |

| c. I believe the test cards are accurate | 40.7 | 41.8 | .724 |

| d. The stool test is convenient | 38.4 | 58.6 | <.001 |

Study variables for Cox proportional hazards regression

We extracted the following variables from the EMR: The primary outcome of CRC screening completion (any of gFOBT, FIT, flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy, dual contrast barium enema) within 9 months of an automated telephone outreach call, demographic variables (age at the time they received the ATC, gender, race/ethnicity—derived from electronic databases, with missing data geocoded using the census tract block corresponding to each subject's mailing address), health characteristics (Body mass index (BMI), number of medications active at the time of receiving the ATC), “Era” (whether they received the gFOBT or FIT as part of the automated telephone outreach program), and, last, variables describing encounters with the health care system. These latter variables included length of KP membership (by 3 years), whether the participant had a primary care provider (vs. none), and whether s/he had visited their primary care provider (PCP) (vs. no PCP visit) or a different PCP (vs. no “other” PCP visit) within 9 months of the ATC. Health-care encounters also included visits with medical specialists (vs. no visit) or with “other” specialists (e.g., orthopedic surgery, neurosurgery, optometry) within 9 months of the ATC (vs. no “other” specialty visit).

Analysis Approach—cohort analysis

Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess association between factors that may be predictive of completing screening and whether those factors were associated with FIT or FOBT. Factors related to screening completion (using any testing method) were first tested with bivariate models and significant factors were carried forward into the multivariable model. We entered variables into the multivariable model in steps in the following order: 1) “Screening era” were the first two variables examined - FIT versus gFOBT (the latter as the reference variable), 2) Next, we added demographic and health characteristics of the patient (e.g., age, gender, number of medications—as a measure of disease burden) and patient health-care utilization factors (e.g., recent visit to primary care provider) and 3) significant interaction terms (screening era by patient characteristic/utilization). To aid in interpretation of the interactions, we stratified the data by screening era, and estimated separate multivariable Cox proportional hazard models for the FIT and gFOBT eras (data not shown).

Analysis Approach—survey analysis

We assessed the proportions of patients answering either “agree” or “strongly agree” to each question of the four-part questions about gFOBT and FIT (see Table 4 below). We compared the proportions within each question between the answers for gFOBT and for FIT using a chi-square test. We considered p<0.05 to be a statistically significant difference in these proportions for each question.

Results

Table 1 compares patient demographic and utilization characteristics between those in the gFOBT era and the FIT era. The mean values and standard deviations below demonstrate the cohorts to be similar. In the gFOBT era, 28.3% completed stool testing, 4.1% flexible sigmoidoscopy, and 4.9% colonoscopy. In the FIT era, 37.2% completed stool testing, 1.9% flexible sigmoidoscopy and 5.9% colonoscopy.

Table 1. Patient Characteristics and Health Care Utilization Measures.

| gFOBT Era* | FIT Era* | |

|---|---|---|

| Age, yrsΔ | 60.7±7.5 | 59.9±6.8 |

| Female, N (%) | 32,422 (54.2) | 17,682 (54.2) |

| Length of HMO Membership, yrsΔ | 12.1±11.1 | 12.3±10.9 |

| No. of Medications at baselineΔ | 3.8±4.1 | 3.6±3.9 |

| BMIΔδ | 30.4±6.9 | 30.4±6.9 |

| Race - White¥ | 37,837 (93.6) | 19,435 (93.4) |

| Race -Black¥ | 877 (2.2) | 452 (2.2) |

| Ethnicity - Hispanic¥ | 956 (3.0) | 503 (3.1) |

| Race –Ind & geo-coded¥ | 55,825 (94.0) | 30,362 (93.9) |

| Assigned to a PCP,λ N (%) | 57,166 (95.5) | 31,045 (95.2) |

| ≥1 PCP visits, N (%) | 27,136 (45.3) | 14,286 (43.8) |

| ≥1 Non-PCP visits, N (%) | 24,907(41.6) | 13,819 (42.4) |

| ≥1 Specialty Visits—Medical, N (%) | 14,734 (24.6) | 7,481 (23.0) |

| ≥1 Specialty Visits—Other, N (%) | 37,095 (62.0) | 18,817 (57.7) |

There are 18,508 (20.0%) common patients in both eras.

Mean and standard deviation values are reported.

BMI = body mass index

Incomplete data –Percentage of data for Individual Race: FOBT (68%) and FIT (64%), Ethnicity: FOBT (54%) and FIT (49%), Individual and geo-coded Race: 99% in both eras.

PCP = primary care provider

Table 2 displays the results of the Cox proportional hazards regression comparing the association of fecal test (FIT vs. gFOBT) with CRC screening completion within 9 months of an automated telephone outreach call. First, we considered only the association of fecal test era with screening completion; those in the FIT era were more likely to complete screening than those in the gFOBT era (HR=1.33; 95% CI 1.30-1.36, p<.0001). Results of step 2 of the regression model demonstrate that offering FIT was associated with increased screening completion, even when adjusting for any differences in patient characteristics and utilization variables (HR=1.40; 95% CI 1.37-1.43, p<0.0001). Patient age, gender, length of KP membership, number of medications, and body mass index (BMI) were each bivariately associated with screening completion using a fecal test; however race was not significantly related to screening completion and thus race was not included in the model. Being older, male, having a lower BMI, having longer length of KP membership, having an assigned PCP, visiting a PCP other than one's assigned PCP, or having a medical specialty visit or any other type of specialty visit, within nine months following the call were all associated with increased screening completion.

Table 2. Cox Proportional Hazards Regression comparing the association of fecal test (FIT vs. gFOBT) with CRC screening completion within 9 months of an automated telephone outreach call.

| Variable | Hazard Ratio |

95% Hazard Ratio | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence | Limits | |||

| Step 1: Era –FIT (unadjusted) | 1.33 | 1.30 | 1.36 | <0.0001 |

| Step 2: Era –FIT (adjusted for all characteristics below) | 1.40 | 1.37 | 1.43 | <0.0001 |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age by 10 yrs | 1.25 | 1.23 | 1.27 | <0.0001 |

| Female | 0.95 | 0.93 | 0.98 | <0.0001 |

| Membership by 3yrs | 1.01 | 1.01 | 1.02 | <0.0001 |

| No. of medications | 0.999 | 0.996 | 1.002 | 0.4152 |

| BMI by 10 units | 0.95 | 0.94 | 0.97 | <0.0001 |

| Utilization measures | ||||

| Has a PCP | 1.11 | 1.05 | 1.18 | 0.0002 |

| ≥1 Other PCP visits | 1.43 | 1.39 | 1.46 | <0.0001 |

| ≥1 Medical specialty visits | 1.25 | 1.22 | 1.28 | <0.0001 |

| ≥1 Surgical and other specialty visits | 1.70 | 1.65 | 1.74 | <0.0001 |

In step 3 of the analysis, we found significant interactions with “screening era” for certain variables: Age, gender, number of medications, and having a PCP visit within the prior nine months. Table 3 presents the final model, including significant interaction terms. Older age, female gender, and increased number of medications were each more strongly associated with completion of screening in the FIT era than in the gFOBT era. However, visiting a PCP or other non-medical specialist was more strongly associated with screening completion in the gFOBT era than in the FIT era. In stratified models (not shown), the hazard ratio controlling for the other variables in the model for age in the gFOBT era was 1.20—every additional 10 years of age increased the likelihood of completing screening by 20.0% during the gFOBT era. In the FIT era, the hazard ratio for age was 1.35; for every additional 10 years of age a person is 35.0% more likely to complete screening during the FIT era. That is, the change from gFOBT to FIT improved screening likelihood more in older than in younger patients. Females were 7.2% less likely to complete screening than males during the gFOBT era and only 0.6% less likely in the FIT era, controlling for other variables in the model. In other words, women improved more in screening rates between the gFOBT (31.7%) and FIT (39.1%) eras than did men (32.4% versus 37.9%) with screening rates no longer significantly different between men and women in the FIT era (p=0.756). Having a PCP increased the likelihood of screening by 22.4% in the gFOBT era, but decreased this likelihood by 2.6% in the FIT era. However, having a PCP was no longer significant in the FIT era. Last, having at least one “other specialty” visit improved screening completion rates during both eras, but was more strongly associated with completion in the gFOBT era (increasing likelihood of screening by 85.6% in the gFOBT era and by 49.5% in the FIT era.)

Table 3. Cox Proportional Hazards Regression comparing the association of multiple variables, including interactions with type of fecal test (“Era”), with CRC screening completion within 9 months of an automated telephone outreach call.

| Variable | Hazard Ratio |

95% Hazard Ratio | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confidence | Limits | |||

| Era –FIT | 0.89 | 0.70 | 1.13 | 0.3449 |

| Patient characteristics | ||||

| Age by 10 yrs | 1.20 | 1.18 | 1.22 | <0.0001 |

| Era * Age | 1.12 | 1.09 | 1.16 | <0.0001 |

| Female | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.96 | <0.0001 |

| Era * Gender | 1.07 | 1.03 | 1.12 | 0.0002 |

| Membership by 3yrs | 1.01 | 1.009 | 1.02 | <0.0001 |

| No. of medications | 0.996 | 0.992 | 0.999 | 0.0202 |

| Era * No. of medications | 1.01 | 1.00 | 1.01 | 0.0087 |

| BMI by 10 units | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.96 | <0.0001 |

| Era * BMI by 10 units | 1.02 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 0.1575 |

| Utilization measures | ||||

| Has a PCP | 1.23 | 1.14 | 1.33 | <0.0001 |

| Era * Has a PCP | 0.79 | 0.70 | 0.88 | <0.0001 |

| Other PCP visits | 1.43 | 1.39 | 1.46 | <0.0001 |

| Medical specialty visits | 1.25 | 1.22 | 1.29 | <0.0001 |

| Surgical and other specialty visit | 1.86 | 1.79 | 1.92 | <0.0001 |

| Era * Surgical and other specialty visits | 0.81 | 0.77 | 0.85 | <0.0001 |

Table 4 shows the proportion of respondents answering “agree” or “strongly agree” to each of the four survey questions. 81.4% of respondents agreed that the instructions for FIT were easy to follow, whereas 64.3% agreed that the instructions for gFOBT were easy to follow (p < 0.001). A significantly greater proportion of respondents agreed that the stool test was unpleasant to complete for gFOBT (53.3%) than for FIT (40.2%) (p = 0.001). Also, a significantly greater proportion of respondents agreed that the stool test was convenient for FIT (58.6%) than for gFOBT (38.4%) (p < 0.001). There was no difference in the perceived accuracy of the stool test between gFOBT (40.7%) and FIT (41.8%) (p = 0.724).

Discussion

We found that changing from gFOBT to FIT in an integrated care delivery system improved the likelihood of screening by 9.5% overall. Although our study could not show causality, we conclude, based on other literature and our findings, that system-wide adoption of FIT results likely resulted in increased screening rates. Patients' survey responses, indicating that FIT was less unpleasant, more convenient,and easier to complete than gFOBT, bolster this conclusion.

Our retrospective analysis of screening completion rates within a large (N=92,477) cohort illustrates that older age was associated with increased screening utilization after the switch from gFOBT to FIT. Older individuals completed more fecal tests than younger individuals, overall, and tended to screen even more when FIT was offered. This finding may explain the greater uptake of FIT in this population, as prior studies indicate that adults aged 65 and over report unpleasantness and discomfort as barriers to test completion.(43). Also, as less education is also known to be associated with decreased screening in this age group, (40;41;44-52) the increased usability of FIT may also have facilitated screening completion.

Although women tended to complete fewer fecal screening tests than men in both time periods, there was a relative increase in female participation in screening when FIT was offered. This is an important finding because women historically are less inclined to complete endoscopy than men, citing embarrassment,(53) and often requests a female endoscopist.(54-59) Also, enthusiasm for gFOBT in women seems to be waning. In earlier studies, more women reported completing gFOBT than men,(60) whereas in later studies, women reported completing gFOBT and colonoscopy equally(61) or less often(62;63) than did men. The advent of a more accurate stool test that is easier to complete may attract greater numbers of women to CRC screening.

Perhaps the most significant finding of our study relates to the decreased association of FIT screening with an office visit compared to gFOBT. Even as screening completion increased with adoption of FIT, it became more weakly associated with having a primary care provider, or with visits to any type of health-care provider. This finding contrasts with findings of numerous published studies demonstrating the influence of physician recommendation, and of having a usual-care provider, on completion of screening.(60;64-66)

Strengths of this study include robust data from our EMR, large cohort size, and the observation of screening rates in a natural setting. The main limitation of this study is that dissemination of fecal testing in communities where colonoscopy is clearly favored may not be as easy to implement. Also, we did not include measures of socioeconomic status in our analysis, which limits generalizability. Last, the outcome of interest was screening with any test, not fecal testing only (though we did provide analyses of the relative increase in fecal test completion individually after the switch from gFOBT to FIT).

Conclusion

In conclusion, this retrospective study of a large cohort in an integrated care system demonstrates that adoption of a one-sample FIT to replace gFOBT was associated with increased colorectal cancer screening rates. Survey results support the conclusion that this change actually led to higher completion rates because patients indicated that the FIT was easier to complete, more convenient, and less unpleasant than gFOBT testing. A centralized outreach program through the mail may be more feasible with FIT than with gFOBT, and may reach certain populations, specifically women and elderly adults, more readily than gFOBT. Such programs may enable dissemination of fecal tests to rural and underserved populations, with follow-up colonoscopy reserved for those with a positive screening FIT.

Summary.

Fecal immunochemical (FIT) testing resulted in higher colorectal cancer screening rates than did guaiac fecal occult blood tests (gFOBT), with less dependence on office visits.

Take-Away Points.

Dissemination of fecal immunochemical (FIT) testing resulted in higher colorectal cancer screening completion rates than were observed using the guaiac fecal occult blood tests (gFOBT).

Visiting a health care provider may be less important for completion of screening with the use of FIT than it has been with the use of gFOBT

Fecal immunochemical testing may enable broader adoption of centralized outreach programs for CRC screening

Populations less inclined to screen with fecal tests, including women, the elderly and those taking more medications, may more readily complete screening when offered FIT than when offered gFOBT

Acknowledgments

Mary Rix and Lucy Fulton for project management. Leslie Bienen for editing.

Funding Source: National Cancer Institute, R01 CA132709

Contributor Information

Nancy Perrin, Email: Nancy.Perrin@kpchr.org.

Ana Gabriela Rosales, Email: Ana.G.Rosales@kpchr.org.

Adrianne C. Feldstein, Email: Adrianne.C.Feldstein@kp.org.

David H. Smith, Email: David.H.Smith@kpchr.org.

David M. Mosen, Email: David.M.Mosen@kpchr.org.

Jennifer L. Schneider, Email: Jennifer.L.Schneider@kpchr.org.

Reference List

- 1.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008 May;58(3):130–60. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Cancer Society Atlanta. Colorectal cancer facts and figures special edition. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards BK, Ward E, Kohler BA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975-2006, featuring colorectal cancer trends and impact of interventions (risk factors, screening, and treatment) to reduce future rates. Cancer. 2010 Feb 1;116(3):544–73. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandel JS, Church TR, Bond JH, et al. The effect of fecal occult-blood screening on the incidence of colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000 Nov 30;343(22):1603–7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindholm E, Brevinge H, Haglind E. Survival benefit in a randomized clinical trial of faecal occult blood screening for colorectal cancer. Br J Surg. 2008 Aug;95(8):1029–36. doi: 10.1002/bjs.6136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kronborg O, Jorgensen OD, Fenger C, Rasmussen M. Randomized study of biennial screening with a faecal occult blood test: results after nine screening rounds. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2004 Sep;39(9):846–51. doi: 10.1080/00365520410003182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scholefield JH, Moss S, Sufi F, Mangham CM, Hardcastle JD. Effect of faecal occult blood screening on mortality from colorectal cancer: results from a randomised controlled trial. Gut. 2002 Jun;50(6):840–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.50.6.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hewitson P, Glasziou P, Irwig L, Towler B, Watson E. Screening for colorectal cancer using the faecal occult blood test, Hemoccult. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Jan 24;(1):CD001216. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001216.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Faivre J, Dancourt V, Lejeune C, et al. Reduction in colorectal cancer mortality by fecal occult blood screening in a French controlled study. Gastroenterology. 2004 Jun;126(7):1674–80. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeBourcy AC, Lichtenberger S, Felton S, Butterfield KT, Ahnen DJ, Denberg TD. Community-based preferences for stool cards versus colonoscopy in colorectal cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2008 Feb;23(2):169–74. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0480-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Almog R, Ezra G, Lavi I, Rennert G, Hagoel L. The public prefers fecal occult blood test over colonoscopy for colorectal cancer screening. Eur J Cancer Prev. 2008 Oct;17(5):430–7. doi: 10.1097/CEJ.0b013e328305a0fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powell AA, Burgess DJ, Vernon SW, et al. Colorectal cancer screening mode preferences among US veterans. Prev Med. 2009 Nov;49(5):442–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beeker C, Kraft JM, Southwell BG, Jorgensen CM. Colorectal cancer screening in older men and women: qualitative research findings and implications for intervention. J Community Health. 2000 Jun;25(3):263–78. doi: 10.1023/a:1005104406934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole SR, Young GP, Esterman A, Cadd B, Morcom J. A randomised trial of the impact of new faecal haemoglobin test technologies on population participation in screening for colorectal cancer. J Med Screen. 2003;10(3):117–22. doi: 10.1177/096914130301000304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Federici A, Giorgi Rossi P, Borgia P, Bartolozzi F, Farchi S, Gausticchi G. The immunochemical faecal occult blood test leads to higher compliance than the guaiac for colorectal cancer screening programmes: a cluster randomized controlled trial. J Med Screen. 2005;12(2):83–8. doi: 10.1258/0969141053908357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fenton JJ, Elmore JG, Buist DS, Reid RJ, Tancredi DJ, Baldwin LM. Longitudinal adherence with fecal occult blood test screening in community practice. Ann Fam Med. 2010 Sep;8(5):397–401. doi: 10.1370/afm.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.van Rossum LG, van Rijn AF, Laheij RJ, et al. Random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical fecal occult blood tests for colorectal cancer in a screening population. Gastroenterology. 2008 Jul;135(1):82–90. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hol L, Wilschut JA, van Ballegooijen M, et al. Screening for colorectal cancer: random comparison of guaiac and immunochemical faecal occult blood testing at different cut-off levels. Br J Cancer. 2009 Apr 7;100(7):1103–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoffman RM, Steel S, Yee EF, Massie L, Schrader RM, Murata GH. Colorectal cancer screening adherence is higher with fecal immunochemical tests than guaiac-based fecal occult blood tests: a randomized, controlled trial. Prev Med. 2010 May;50(5-6):297–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2010.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burch JA, Soares-Weiser K, St John DJ, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of faecal occult blood tests used in screening for colorectal cancer: a systematic review. J Med Screen. 2007;14(3):132–7. doi: 10.1258/096914107782066220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Imperiale TF, Ransohoff DF, Itzkowitz SH, Turnbull BA, Ross ME. Fecal DNA versus fecal occult blood for colorectal-cancer screening in an average-risk population. N Engl J Med. 2004 Dec 23;351(26):2704–14. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa033403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park DI, Ryu S, Kim YH, et al. Comparison of guaiac-based and quantitative immunochemical fecal occult blood testing in a population at average risk undergoing colorectal cancer screening. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010 Sep;105(9):2017–25. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2010.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sohn DK, Jeong SY, Choi HS, et al. Single immunochemical fecal occult blood test for detection of colorectal neoplasia. Cancer Res Treat. 2005 Feb;37(1):20–3. doi: 10.4143/crt.2005.37.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakama H, Yamamoto M, Kamijo N, et al. Colonoscopic evaluation of immunochemical fecal occult blood test for detection of colorectal neoplasia. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999 Jan;46(25):228–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morikawa T, Kato J, Yamaji Y, et al. Sensitivity of immunochemical fecal occult blood test to small colorectal adenomas. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007 Oct;102(10):2259–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01404.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cheng TI, Wong JM, Hong CF, et al. Colorectal cancer screening in asymptomaic adults: comparison of colonoscopy, sigmoidoscopy and fecal occult blood tests. J Formos Med Assoc. 2002 Oct;101(10):685–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Levi Z, Rozen P, Hazazi R, et al. A quantitative immunochemical fecal occult blood test for colorectal neoplasia. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Feb;146(4):244–55. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-146-4-200702200-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Screening for colorectal cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008 Nov 4;149(9):627–37. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-149-9-200811040-00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freeborn DK, Pope C. Promise and Performance in Managed Care: The Prepaid Group Practice Model. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mosen DM, Feldstein AC, Perrin N, et al. Automated telephone calls improved completion of fecal occult blood testing. Med Care. 2010 Jul;48(7):604–10. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181dbdce7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Costanza ME, Luckmann R, Stoddard AM, et al. Applying a stage model of behavior change to colon cancer screening. Prev Med. 2005 Sep;41(3-4):707–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Denberg TD, Melhado TV, Coombes JM, et al. Predictors of nonadherence to screening colonoscopy. J Gen Intern Med. 2005 Nov;20(11):989–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00164.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Myers RE, Sifri R, Hyslop T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of the impact of targeted and tailored interventions on colorectal cancer screening. Cancer. 2007 Nov 1;110(9):2083–91. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Myers RE, Hyslop T, Sifri R, et al. Tailored navigation in colorectal cancer screening. Med Care. 2008 Sep;46(9 Suppl 1):S123–S131. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817fdf46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ) Health Behavior Constructs: Theory, Measurement & Research. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institue; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lafata JE, Divine G, Moon C, Williams LK. Patient-physician colorectal cancer screening discussions and screening use. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Sep;31(3):202–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.04.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.AHRQ. Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) AHRQ website. 2011 Nov 28; Available from: URL: www.cahps.ahrq.gov.

- 38.Glasgow RE, Magid DJ, Beck A, Ritzwoller D, Estabrooks PA. Practical clinical trials for translating research to practice: Design and measurement recommendations. Med Care. 2005 Jun;43(6):551–7. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163645.41407.09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lafata JE, Williams LK, Ben-Menachem T, Moon C, Divine G. Colorectal carcinoma screening procedure use among primary care patients. Cancer. 2005 Oct 1;104(7):1356–61. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Malley AS, Forrest CB, Feng S, Mandelblatt J. Disparities despite coverage: gaps in colorectal cancer screening among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Oct 10;165(18):2129–35. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.18.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Klabunde CN, Schenck AP, Davis WW. Barriers to colorectal cancer screening among Medicare consumers. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Apr;30(4):313–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Farmer MM, Bastani R, Kwan L, Belman M, Ganz PA. Predictors of colorectal cancer screening from patients enrolled in a managed care health plan. Cancer. 2008 Mar 15;112(6):1230–8. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Guessous I, Dash C, Lapin P, Doroshenk M, Smith RA, Klabunde CN. Colorectal cancer screening barriers and facilitators in older persons. Prev Med. 2010 Jan;50(1-2):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ananthakrishnan AN, Schellhase KG, Sparapani RA, Laud PW, Neuner JM. Disparities in colon cancer screening in the Medicare population. Arch Intern Med. 2007 Feb 12;167(3):258–64. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.3.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cokkinides VE, Chao A, Smith RA, Vernon SW, Thun MJ. Correlates of underutilization of colorectal cancer screening among U.S. adults, age 50 years and older. Prev Med. 2003 Jan;36(1):85–91. doi: 10.1006/pmed.2002.1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cooper GS, Doug KT. Underuse of colorectal cancer screening in a cohort of Medicare beneficiaries. Cancer. 2008 Jan 15;112(2):293–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.23176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Etzioni DA, Ponce NA, Babey SH, et al. A population-based study of colorectal cancer test use: results from the 2001 California Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2004 Dec 1;101(11):2523–32. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Klabunde CN, Meissner HI, Wooten KG, Breen N, Singleton JA. Comparing colorectal cancer screening and immunization status in older americans. Am J Prev Med. 2007 Jul;33(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.02.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Morales LS, Rogowski J, Freedman VA, Wickstrom SL, Adams JL, Escarce JJ. Sociodemographic differences in use of preventive services by women enrolled in Medicare+Choice plans. Prev Med. 2004 Oct;39(4):738–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schneider EC, Rosenthal M, Gatsonis CG, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Is the type of Medicare insurance associated with colorectal cancer screening prevalence and selection of screening strategy? Med Care. 2008 Sep;46(9 Suppl 1):S84–S90. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31817fdf80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shenson D, Bolen J, Adams M. Receipt of preventive services by elders based on composite measures, 1997-2004. Am J Prev Med. 2007 Jan;32(1):11–8. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shenson D, Bolen J, Adams M, Seeff L, Blackman D. Are older adults up-to-date with cancer screening and vaccinations? Prev Chronic Dis. 2005 Jul;2(3):A04. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Elta GH. Women are different from men. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002 Aug;56(2):308–9. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70202-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jimenez B, Palekar N, Schneider A. Issues related to colorectal cancer and colorectal cancer screening practices in women. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2011 Jun;40(2):415–26. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2011.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Menees SB, Inadomi JM, Korsnes S, Elta GH. Women patients' preference for women physicians is a barrier to colon cancer screening. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005 Aug;62(2):219–23. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(05)00540-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Varadarajulu S, Petruff C, Ramsey WH. Patient preferences for gender of endoscopists. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002 Aug;56(2):170–3. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70173-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zapatier JA, Kumar AR, Perez A, Guevara R, Schneider A. Preferences for ethnicity and sex of endoscopists in a Hispanic population in the United States. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Jan;73(1):89–97. 97. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schneider A, Kanagarajan N, Anjelly D, Reynolds JC, Ahmad A. Importance of gender, socioeconomic status, and history of abuse on patient preference for endoscopist. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009 Feb;104(2):340–8. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee SY, Yu SK, Kim JH, et al. Link between a preference for women colonoscopists and social status in Korean women. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008 Feb;67(2):273–7. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Seeff LC, Nadel MR, Klabunde CN, et al. Patterns and predictors of colorectal cancer test use in the adult U.S. population. Cancer. 2004 May 15;100(10):2093–103. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vital signs: colorectal cancer screening among adults aged 50-75 years - United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010 Jul;:808–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Swan J, Breen N, Graubard BI, et al. Data and trends in cancer screening in the United States: results from the 2005 National Health Interview Survey. Cancer. 2010 Oct 15;116(20):4872–81. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brawarsky P, Brooks DR, Mucci LA. Correlates of colorectal cancer testing in Massachusetts men and women. Prev Med. 2003 Jun;36(6):659–68. doi: 10.1016/s0091-7435(03)00046-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Stockwell DH, Woo P, Jacobson BC, et al. Determinants of colorectal cancer screening in women undergoing mammography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 Aug;98(8):1875–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07577.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ioannou GN, Chapko MK, Dominitz JA. Predictors of colorectal cancer screening participation in the United States. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003 Sep;98(9):2082–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Doubeni CA, Laiyemo AO, Young AC, et al. Primary care, economic barriers to health care, and use of colorectal cancer screening tests among Medicare enrollees over time. Ann Fam Med. 2010 Jul;8(4):299–307. doi: 10.1370/afm.1112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]