Abstract

The molecular mechanisms that underlie T cell quiescence are poorly understood. Here we report that mature naive CD8+ T cells lacking the transcription factor Foxp1 gained effector phenotype and function and proliferated directly in response to interleukin 7 (IL-7) in vitro. Foxp1 repressed expression of the IL-7 receptor α-chain (IL-7Rα) by antagonizing Foxo1 and negatively regulated signaling by the kinases MEK and Erk. Acute deletion of Foxp1 induced naive T cells to gain an effector phenotype and proliferate in lymphoreplete mice. Foxp1-deficient naive CD8+ T cells proliferated even in lymphopenic mice deficient in major histocompatibility complex class I. Our results demonstrate that Foxp1 exerts essential cell-intrinsic regulation of naive T cell quiescence, providing direct evidence that lymphocyte quiescence is achieved through actively maintained mechanisms that include transcriptional regulation.

Peripheral naive T lymphocytes are considered quiescent, a state thought to be due to a lack of activation signals. Growing evidence, however, suggests that T cell quiescence does not occur by default but is actively maintained by both intrinsic and extrinsic mechanisms1,2. Antigen stimulation can drive quiescent naive T cells to undergo proliferation and gain effector functions, but these same changes can occur without overt antigen challenge in circumstances such as lymphopenia or after ablation of either inhibitory receptors or regulatory T cells3–8. To a large extent, the molecular mechanisms that underlie naive T cell quiescence, especially at the transcriptional level, are poorly understood.

The survival of naive T cells involves both engagement of the T cell antigen receptor (TCR) and stimulation of the IL-7 receptor (IL-7R), which indicates that in a quiescent state, these cells require constant subthreshold signals to persist9–11. Lymphopenia-induced proliferation of naive T cells also requires signals from TCR and IL-7R3,4,9–11. TCR stimulation can trigger three mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways: the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (Erk) pathway; the c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase (Jnk) pathway; and the p38 pathway12–14. Differences in the activation of these signaling pathways lead to distinct functional outcomes in T cell development and activation15,16. Less Erk activity affects both thymocyte maturation and the activation of peripheral mature T cells15–17. IL-7R is also critical for thymocyte development, the survival of naive T cells and homeostasis9–11,18,19. The IL-7R complex is composed of an IL-7R α-chain (IL-7Rα) and the common cytokine receptor γ-chain, but the control of IL-7 signaling is regulated mainly by IL-7Rα expression20. Several transcription factors and an enhancer regulatory element are known to control IL-7Rα expression in T lineage cells21–24. Despite those findings, the nature of the combinatorial signals from TCR and IL-7R and their regulation in naive T cell quiescence and lymphopenia-induced proliferation remain unclear10,11. In particular, little is known about cell-intrinsic transcriptional regulation that may actively dampen such signals and prevent peripheral T cells from being spontaneously activated.

The forkhead box (Fox) proteins constitute a large transcription factor family with diverse functions25–27. Foxo1 has a critical role in regulating IL-7Rα expression and T cell homeostasis28,29. The activated phenotype of Foxo1-deficient T cells seems to be mainly due to secondary, lymphopenia-induced proliferation after more apoptosis of Foxo1-deficient T cells28,29. Foxp1, a member of the ‘Foxp’ subfamily, is expressed in many tissues and is a critical transcriptional regulator in B lymphopoiesis30–32. Conditional deletion of Foxp1 at the CD4+CD8+ double-positive (DP) thymocyte stage has proven that Foxp1 is essential for the generation of quiescent naive T cells during thymocyte development33.

In this study, we circumvented abnormal thymocyte development and studied the function of Foxp1 in mature T cells through the use of an inducible deletion model system. We found that mature naive CD8+ T cells lacking Foxp1 gained effector phenotype and function and proliferated directly in response to IL-7 in vitro. We further demonstrated that Foxp1 antagonized Foxo1 for binding to the same forkhead-binding site in the IL-7Rα enhancer region. By negatively regulating IL-7Rα expression and signaling by MEK and Erk, Foxp1 exerted essential cell-intrinsic transcriptional regulation of the quiescence and homeostasis of mature naive T cells.

RESULTS

Foxp1-deficient naive CD8+ T cells proliferate in response to IL-7

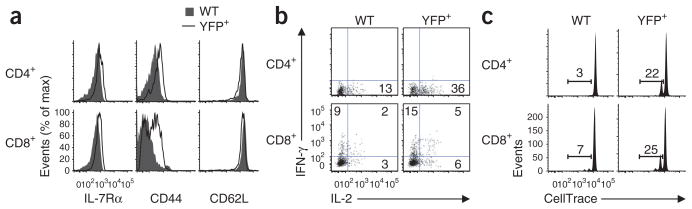

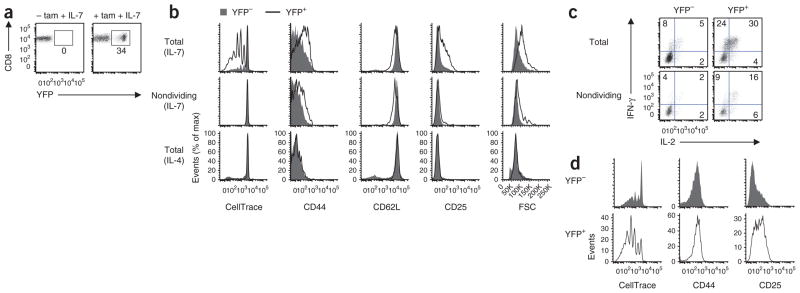

To study Foxp1 function in mature T cells, we generated Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP mice in which Cre recombinase becomes activated by treatment with tamoxifen34 and Cre induces deletion of loxP-flanked Foxp1 alleles (Foxp1f/f) and the expression of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) as a reporter35. We sorted CD44loCD8+ T cells from Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP mice and cultured the cells with or without tamoxifen and IL-7. Without tamoxifen, there was no YFP induction (Fig. 1a) or cell proliferation (Supplementary Fig. 1a) in the culture by day 6. Without IL-7, most cells died in the culture (data not shown). In contrast, in cultures with tamoxifen and IL-7, YFP+ cells started to emerge around day 2 (data not shown). By day 6, in contrast to YFP− cells, most YFP+ cells proliferated, upregulated their expression of CD44 and CD25, slightly downregulated CD62L and increased in size (Fig. 1b). We also observed such phenotypic changes, although to a lesser extent, in nondividing YFP+ cells (Fig. 1b). We also examined CD44loCD8+ T cells sorted from Foxp1f/+Cre-ERT2+RosaYFP mice. Consistent with published observations of only a minor phenotype for CD8+ T cells from Foxp1f/+Cd4-Cre mice (which have one loxP-flanked Foxp1 allele and expression of Cre driven by Cd4)33, YFP+ Foxp1f/+Cre-ERT2+RosaYFP CD8+ T cells still expressed Foxp1 and did not proliferate or change their phenotype (Supplementary Fig. 1b–c). This indicated that complete deletion of Foxp1 in CD8+ T cells was required for the phenotypic changes we observed. These changes occurred by day 6 only in cultures treated with IL-7, but not in those treated with IL-4 (or IL-15; Fig. 1b and data not shown), although there was equally efficient deletion of Foxp1 and induction of YFP+ cells in all cultures by day 4 (Supplementary Fig. 1b,d).

Figure 1.

Foxp1-deficient mature naive CD8+ T cells gain effector phenotype and function and proliferate in response to IL-7 in vitro. (a) Induction of YFP expression in sorted CD44loCD8+ Foxp1f/fCre- ERT2+RosaYFP T cells cultured for 6 d with IL-7 in the presence (+ tam + IL-7) or absence (- tam + IL-7) of tamoxifen. Numbers adjacent to outlined areas indicate percent YFP+ cells. (b) Cell proliferation and phenotype characterization of sorted CD44loCD8+ Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP T cells cultured for 6 d with tamoxifen plus either IL-7 or IL-4; far left, analysis of cell division on the basis of CellTrace dilution. (c) Cytokine production in cells treated with tamoxifen and IL-7 as in b and then stimulated for 4 h with PMA plus ionomycin (cell division assessed by CellTrace dilution). Numbers in quadrants indicate percent cells in each throughout. (d) Cell proliferation and phenotype characterization of sorted CD44hiCD8+ Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP T cells cultured for 6 d with tamoxifen and IL-7; far left, analysis of cell division on the basis of CellTrace dilution. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Functional analysis showed that stimulation with phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) plus ionomycin induced a greater frequency of IFN-γ- and IL-2-producing YFP+ cells than IFN-γ- and IL-2- producing YFP− T cells (Fig. 1c). We also observed such functional changes in nondividing YFP+ cells (Fig. 1c), which indicated that both the phenotypic changes and functional changes in YFP+ cells were induced without proliferation. The proliferation of YFP+ cells in response to IL-7 was not due to contamination by CD44hiCD8+ T cells during the sorting of CD44loCD8+ T cells from the mice, because YFP+ cells from cultures of CD44loCD8+ T cells proliferated much more than did YFP− cells from cultures of sorted CD44hiCD8+ T cells (Fig. 1b,d). YFP+ cells from cultures of sorted CD44hiCD8+ T cells also proliferated substantially and upregulated CD25 expression (Fig. 1d).

To further confirm that Foxp1-deficient naive CD8+ T cells proliferated in response to IL-7, we sorted CD44loCD8+ T cells from Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP mice and control wild-type littermates (Foxp1f/fRosaYFP mice) and cultured them for 2 d, then sorted YFP+ and wild-type control cells and cultured them in equal numbers with IL-7 alone. Because we noted deletion of Foxp1 in some YFP− T cells from Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP mice after tamoxifen treatment (data not shown), we used cultured wild-type T cells as controls in this set of experiments (for the same reason, we used congenic wild-type controls in the in vivo transfer experiments described below). By day 6, YFP+ cells proliferated more, which resulted in more total cells and higher granzyme B expression than that of wild-type control cells (Supplementary Fig. 2a–c). These results suggest that the deletion of Foxp1 leads mature naive CD8+ T cells to gain both effector phenotype and function and proliferate in response to IL-7 in the absence of overt TCR stimulation. Mature naive CD4+ T cells in which Foxp1 was acutely deleted gained effector phenotype and function as well (albeit to a much lesser extent than did CD8+ T cells) but did not proliferate in response to IL-7 or IL-4 in vitro (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c).

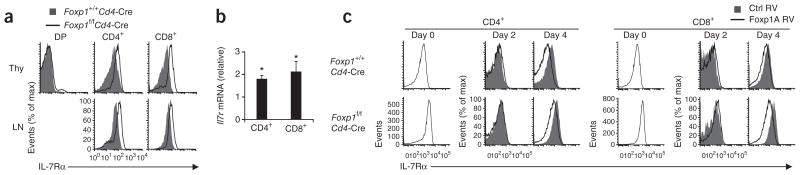

Foxp1 represses IL-7Rα expression

The proliferation of Foxp1-deficient naive CD8+ T cells in response to IL-7 prompted us to investigate IL-7Rα expression. Because IL-7 was required for in vitro culture and IL-7 downregulated IL-7Rα expression36 (data not shown), we assessed IL-7Rα expression in T cells from mice with both loxP-flanked Foxp1 alleles and expression of Cre driven by Cd4 (Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre mice). We found that IL-7Rα expression was higher in Foxp1-deficient CD4+ and CD8+ single-positive thymocytes and peripheral T cells than in wild-type control cells (Fig. 2a). IL-7Rα expression was also higher in Foxp1-deficient T cells in mixed–bone marrow chimeras of lethally irradiated intact recipient mice reconstituted with T cell–depleted bone marrow from Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre and Foxp1+/+Cd4-Cre mice (Supplementary Fig. 4a), which indicated cell-intrinsic control of IL-7Rα expression by Foxp1. In addition, we found enhanced phosphorylation of the transcription factor STAT5 in activated Foxp1-deficient CD4+ T cells cultured with IL-7 (Supplementary Fig. 4b), which suggested that the higher IL-7Rα expression in Foxp1-deficient T cells was functional. Ex vivo, Foxp1-deficient T cells had higher expression of Il7r mRNA than did wild-type control cells (Fig. 2b). We transduced retrovirus expressing Foxp1A, the dominant Foxp1 isoform in T lineage cells33, into T cells in vitro. During the first 2 d of TCR stimulation, IL-7Rα expression was downregulated in both Foxp1-deficient T cells and control T cells (Fig. 2c). By day 4, Foxp1A repressed IL-7Rα expression in both Foxp1-deficient and wild-type control T cells relative to its expression in T cells infected with control retrovirus (Fig. 2c). Thus, although the acute downregulation of IL-7Rα by TCR stimulation is not Foxp1 dependent, Foxp1 represses IL-7Rα expression in both CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells.

Figure 2.

Foxp1 represses IL-7Rα expression in T cells. (a) Cell surface IL-7Rα expression in thymocytes (Thy) and peripheral lymph node T cells (LN) from Foxp1+/+Cd4-Cre control mice and Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre mice. (b) Real-time PCR analysis of Il7r mRNA in peripheral CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre mice; results are normalized to Rpl32 mRNA (which encodes the ribosomal protein L32) and are presented relative to Il7r mRNA in Foxp1+/+Cd4-Cre control cells. *P < 0.01 (Student’s t-test). (c) Cell surface IL-7Rα expression on Foxp1+/+Cd4-Cre and Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre peripheral T cells before (day 0) and after (day 2 and day 4) overexpression in vitro of control retrovirus encoding GFP alone (Ctrl RV) or retrovirus encoding GFP and Foxp1A (Foxp1A RV). Data are representative of three independent experiments (a,c) or are from three independent experiments (b; average and s.d.).

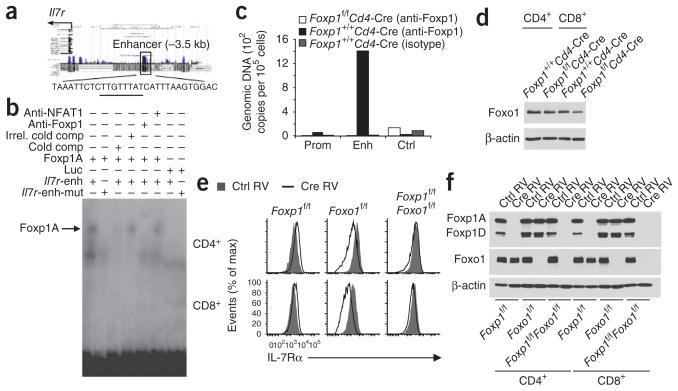

Foxp1 antagonizes Foxo1 in the regulation IL-7Rα expression

Bioinformatics analysis identified three forkhead-binding sites with high scores in the Il7r locus, with one in the Il7r enhancer region23,28,29 (Fig. 3a). By electrophoretic mobility-shift assay (EMSA), we found that Foxp1A translated in vitro bound specifically to the Il7r enhancer fragment containing the predicted forkhead-binding site (Fig. 3b). Binding was inhibited by competition with an identical unlabeled oligonucleotide but not by competition with an irrelevant oligonucleotide. Binding was also inhibited by mutation of the forkhead-binding site. The mobility of the DNA-protein complex shifted after the addition of a Foxp1-specific antibody but not after the addition of control antibodies (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3.

Foxp1 represses Il7r expression by binding to its enhancer, and the downregulation of IL-7Rα expression in Foxo1-deficient T cells is Foxp1 dependent. (a) Predicted forkhead-binding site (underlined) in the known Il7r enhancer, located 3.5 kilobases upstream of the transcription start site (−3.5 kb). (b) EMSA of in vitro–translated Foxp1A with the Il7r enhancer fragment DNA as probe. Anti-NFAT1, control antibody to the transcription factor NFAT1; Irrel. cold comp, irrelevant unlabeled competitor; Cold comp, unlabeled competitor; Luc, control luciferase protein; Il7r-enh, Il7r enhancer oligonucleotide; Il7r-enh-mut, mutated Il7r enhancer oligonucleotide. (c) ChIP analysis of the promoter (Prom), enhancer (Enh) and control regions of the Il7r locus in Foxp1+/+Cd4-Cre and Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre CD8+ T cells, assessed with anti-Foxp1 or isotype-matched control antibody; results are presented as genomic DNA copies relative to standard input DNA dilution. (d) Immunoblot analysis of Foxo1 expression in Foxp1 Cd4-Cre and Foxp1 Cd4-Cre T cells ex vivo; β-actin serves as a loading control throughout. (e) Cell surface IL-7Rα expression in vitro on CD4+ or CD8+ Foxp1f/f, Foxo1f/f and Foxp1f/fFoxo1f/f T cells infected with retrovirus expressing GFP alone (Ctrl RV) or Cre and GFP (Cre RV) and then cultured for 4 d; results are gated on GFP+ (retrovirus-expressing) cells. (f) Immunoblot analysis of the expression of Foxp1 and Foxo1 in sorted GFP+ cells 4 d after retroviral infection as in e. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

Chromatin-immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay of Foxp1 in mature wild-type T cells also showed that Foxp1 bound specifically to the Il7r enhancer region (Fig. 3c), which suggested that IL-7Rα is probably a direct target of Foxp1. Foxo1 is known to upregulate IL-7Rα expression by binding to the same Il7r enhancer region28,29. We did not find an overall increase in Foxo1 protein, or its accumulation in the nucleus, in Foxp1-deficient T cells (Fig. 3d and data not shown), which suggested that the higher IL-7Rα expression in Foxp1-deficient T cells was probably not due to higher Foxo1 expression.

Our EMSA showed that Foxo1 bound to the same forkhead-binding site in the Il7r enhancer region as Foxp1 did (Supplementary Fig. 5a). To address how Foxp1 and Foxo1 interact to control IL-7Rα enhancer activity, we transiently transfected EL4 mouse lymphoma cells with an Il7r enhancer–luciferase reporter construct23. In this context, when tested either alone or together, Foxp1 and Foxo1 had only marginal effects on the Il7r enhancer reporter (data not shown). We were unable to distinguish whether additional cofactors are necessary or whether the antagonism between Foxp1 and Foxo1 can be observed only in the context of native chromatin.

To further address how these two transcription factors interact on the Il7r enhancer, we generated Foxp1f/fFoxo1f/f mice and deleted both Foxp1 and Foxo1 in T cells by in vitro retroviral expression of Cre recombinase (with green fluorescent protein (GFP) as a reporter of retroviral expression; Fig. 3e,f). The amount of IL-7Rα was similar in uninfected (GFP−) T cells in control and Cre-expressing retroviral cultures (Supplementary Fig. 5b). IL-7Rα expression was slightly higher in GFP+ Foxp1f/f T cells infected with Cre-expressing retrovirus than in their GFP+ counterparts infected with control retrovirus but was much lower in GFP+ Foxo1f/f T cells (Fig. 3e). IL-7Rα expression was similar in GFP+ Foxp1f/fFoxo1f/f T cells infected with control retrovirus and those infected with Cre-expressing retrovirus (Fig. 3e). These data suggest that the downregulation of IL-7Rα expression in Foxo1-deficient T cells is Foxp1 dependent and that Foxp1 is a repressor of IL-7Rα expression.

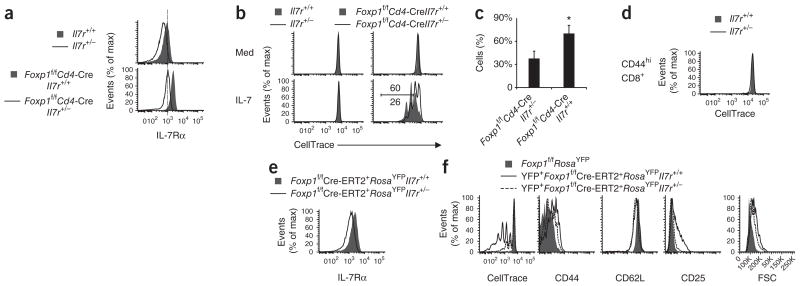

IL-7R in the proliferation of CD8+ T cells

To determine how the amount of IL-7Rα regulates CD8+ T cell proliferation, we took advantage of the differences between wild-type Il7r+/+ T cells and heterozygous Il7r+/− T cells in their expression of IL-7Rα (Fig. 4a) and generated Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre Il7r+/− mice. IL-7Rα expression in Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre Il7r+/− T cells was as low as its expression in normal wild-type (Il7r+/+) T cells (Fig. 4a). We cultured purified CD8+ T cells from Il7r+/+, Il7r+/−, Foxp1f/f Cd4-Cre Il7r+/+ and Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre Il7r+/− mice with IL-7 in vitro. By day 3, only Foxp1-deficient CD8+ T cells proliferated, in a manner dependent on the concentration of IL-7R and IL-7 (Fig. 4b,c and Supplementary Fig. 6a).

Figure 4.

Foxp1-deficient CD8+ T cells with higher expression of IL-7Rα proliferate more in response to IL-7. (a) Cell surface IL-7Rα expression on CD8+ T cells (ex vivo) from Il7r+/+ and Il7r+/− mice (top) and Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre Il7r+/+ and Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre Il7r+/− mice (bottom). (b) Proliferation of CD8+ T cells (genotypes as in a) in response to medium (Med) or IL-7 in vitro, assessed at day 3. Numbers above (Foxp1f/f Cd4-Cre Il7r+/+) and below (Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre Il7r+/−) bracketed line indicate percent cells with more than two divisions. (c) Frequency of the CD8+ Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre Il7r+/+ and Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre Il7r+/− T cells with more than two divisions in response to IL-7 in vitro, assessed at day 3. *P < 0.05 (Student’s t-test). (d) Proliferation of sorted Il7r+/+and Il7r+/− CD44hi CD8+ T cells in response to IL-7 in vitro, assessed at day 6. (e) Cell surface IL-7Rα expression in CD8+ T cells (ex vivo) from Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFPIl7r+/+ and Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFPIl7r+/− mice. (f) Proliferation and phenotype characterization of CD44loCD8+ T cells sorted from Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+ RosaYFPIl7r+/+ mice, Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFPIl7r+/− mice and Foxp1f/fRosaYFP mice and cultured for 6 d with tamoxifen and IL-7. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments (a,b,d–f) or are from three independent experiments (c; average and s.d.).

Although lower IL-7R expression did not correct the abnormal activated phenotype of Foxp1-deficient T cells from Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre mice (Supplementary Fig. 6b), almost no CD44hiCD8+ T cells sorted from Il7r+/+ and Il7r+/− mice proliferated in response to IL-7 (Fig. 4d), which suggested that Foxp1-deficient CD8+ T cells proliferated in response to IL-7 because of the Foxp1 deletion and not because of the activated status. To circumvent the issue of the activated cell status and determine whether IL-7R is essential, we generated Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP Il7r+/− mice in which the IL-7R expression in naive CD8+ T cells was about 60% of its expression in Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP Il7r+/+ control cells (Fig. 4e and data not shown). The lower IL-7R expression alone was sufficient to substantially impair the proliferation and some of the phenotypic changes of naive CD8+ T cells in response to IL-7 after deletion of Foxp1 (Fig. 4f). These results suggest that the amount of IL-7R is critical for the proliferation of naive Foxp1-deficient CD8+ T cells in response to IL-7 in vitro.

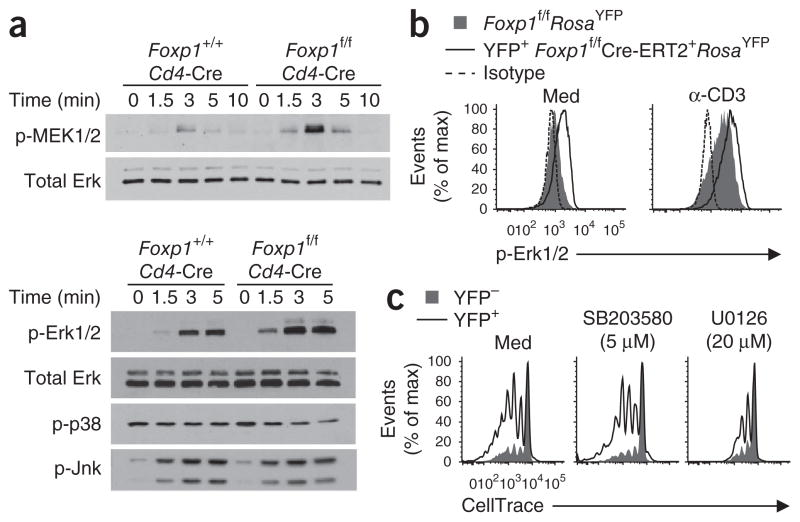

Foxp1 negatively regulates signaling by MEK and Erk

Adjustment of IL-7Rα expression to nearly wild-type amounts did not completely prevent the IL-7-induced proliferation of Foxp1-deficient CD8+ T cells, which suggested that in addition to regulating IL-7R, Foxp1 regulates some other molecule(s) critical for the proliferation of CD8+ T cells ex vivo in response to IL-7. In Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre mice, Foxp1 starts to be deleted in DP thymocytes, but analyses of cell numbers and expression of cell surface markers (including TCRβ and CD3) have indicated that Foxp1-deficient DP thymocytes seem to be normal33. Because the overall activated phenotype of Foxp1-deficient T cells indicated a potential role in TCR signaling, we investigated the activation of MEK, Erk, Jnk and p38 in DP thymocytes. We found that the activation of Jnk and p38 was similar in Foxp1-deficient and wild-type control DP thymocytes, but the activation of MEK and Erk was enhanced in Foxp1-deficient DP thymocytes (Fig. 5a). Notably, IL-7Rα was not expressed in DP thymocytes (Fig. 2a); thus, the regulation of MEK signaling and Erk signaling by Foxp1 was independent of the effect of Foxp1 on IL-7Rα.

Figure 5.

MEK-Erk activation is enhanced in Foxp1-deficient T cells, and blocking MEK activation inhibits the proliferation of Foxp1-deficient naive CD8+ T cells in response to IL-7 in vitro. (a) Immunoblot analysis of phosphorylated (p-) MEK1 and MEK2 (MEK1/2), Erk1 and Erk2 (Erk1/2), p38 and Jnk in CD5lo DP thymocytes sorted from Foxp1+/+Cd4-Cre or Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre mice and then stimulated by crosslinking with anti-CD3 and anti-CD28; total Erk serves as a loading control. (b) Intracellular staining of phosphorylated Erk in CD44loCD8+ T cells sorted from Foxp1f/f Cre-ERT2+RosaYFP or Foxp1f/fRosaYFP mice and cultured with tamoxifen and IL-7 for 4 d before (Med) and after stimulation by crosslinking with anti-CD3 (α-CD3). Isotype, staining with isotype-matched control antibody. (c) Proliferation of CD44loCD8+ T cells sorted from Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP mice and cultured for 6 d with tamoxifen and IL-7 in the presence of the medium alone (Med) or the chemical inhibitors SB203580 (p38 inhibitor) and U0126 (MEK1-MEK2 inhibitor). The inhibitor concentrations used here were the highest that still allowed 90% of the viability in control cultures without inhibitors (data not shown). Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

We also examined Erk activation in mature T cells and found that by day 4 of in vitro culture, Erk phosphorylation was greater in YFP+CD8+ T cells from Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP mice than in wild-type control cells both before and after TCR stimulation (Fig. 5b). The addition of U0126, a chemical inhibitor specific for MEK1 and MEK2, resulted in much less proliferation of Foxp1-deficient naive CD8+ T cells in response to IL-7, but the addition of SB203580, a chemical inhibitor specific for p38, did not (Fig. 5c). These results suggest that MEK and Erk, but not the p38 signaling pathway, are involved in the Foxp1-regulated proliferation of naive CD8+ T cells in response to IL-7 in the absence of overt TCR stimulation.

Foxp1 regulates T cell quiescence and homeostasis in vivo

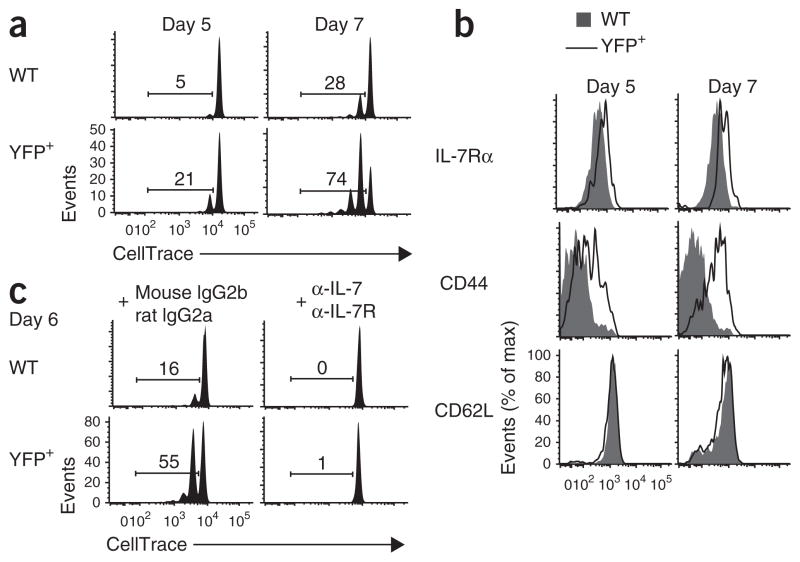

To examine how Foxp1 regulates naive T cell quiescence and homeostasis in vivo, and to avoid potential secondary effects due to the deletion of Foxp1 in non-T cells after tamoxifen treatment in vivo, we used an adoptive-transfer model system. We mixed CD44lo CD8+ or CD4+ T cells sorted from Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP and control CD45.1+ congenic wild-type mice and labeled the cells with the fluorescent dye CellTrace, then transferred them together into intact recipient mice, which received tamoxifen treatment 1 d before the transfer and for the first 3 d after transfer. At 8 d after transfer, most of the YFP+ cells in the recipient mice upregulated their expression of IL-7Rα and CD44 but did not proliferate (Fig. 6a and data not shown). A higher percentage of YFP+ cells than wild-type control cells produced IFN-γ and/or IL-2 after stimulation with PMA plus ionomycin (Fig. 6b). At 15 d after transfer, the deletion of Foxp1 induced the proliferation of a substantial fraction of CD8+ and CD4+ T cells (Fig. 6c). In recipient mice that did not receive any tamoxifen treatment, we detected no proliferation of either Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP T cells or wild-type control T cells at 15 d after transfer (data not shown). These results suggest that Foxp1 is critical for the maintenance of quiescence in both naive CD8+ and CD4+ T cells in lymphoreplete mice.

Figure 6.

Foxp1-deficient mature naive T cells gain effector phenotype and function and proliferate in intact recipient mice. (a) Phenotype characterization of Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP (YFP+) and CD45.1+ control wild-type (WT) donor T cells 8 d after transfer into intact recipient mice. (b) Intracellular staining of the production of IL-2 and IFN-γ in donor T cells as in a after stimulation for 4 h with PMA plus ionomycin. Numbers in quadrants indicate percent cells in each. (c) Proliferation of donor T cells as in a 15 d after transfer into intact recipient mice. Numbers above bracketed lines indicate percent proliferating cells. Data are representative of two independent experiments.

The proliferation of Foxp1-deficient naive CD8+ T cells in response to IL-7 in vitro occurred without TCR stimulation (Fig. 1). To determine whether TCR engagement is important for the regulation of naive T cell quiescence and homeostasis by Foxp1 in vivo, we mixed CD44loCD8+ T cells sorted from Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP and control CD45.1+ congenic wild-type mice, labeled the cells with CellTrace and cultured them for 2 d with tamoxifen in medium. These conditions ensured deletion of Foxp1 before the transfer of cells and subsequent proliferation in the lymphopenic environment of sublethally irradiated mice deficient in H-2Kb and H-2Db. At 7 d after transfer, whereas most of the wild-type control cells did not proliferate, many more Foxp1-deficient naive CD8+ T cells proliferated and upregulated CD44 expression in recipient mice deficient in H-2Kb and H-2Db (Fig. 7a,b). We obtained similar results in parallel experiments in which we first transferred cells into irradiated mice deficient in H-2Kb and H-2Db, then treated the recipient mice with tamoxifen in vivo (Supplementary Fig. 7ab). However, in recipient mice deficient in recombination-activating gene 1, Foxp1-deficient CD8+ T cells proliferated only slightly more than wild-type control cells did (data not shown), which indicated that the enhanced proliferation of Foxp1-deficient CD8+ T cells in lymphopenia was less notable when complexes of self peptide and major histocompatibility complex were available. Nevertheless, inhibition of IL-7R signaling with antibody to IL-7 and antibody to IL-7R almost completely blocked the proliferation of Foxp1-deficient CD8+ T cells in recipient mice deficient in H-2Kb and H-2Db (Fig. 7c). These results suggest that in lymphopenic conditions and in the absence of (or in the presence of considerably less) engagement of the TCR with complexes of self peptide and major histocompatibility complex, Foxp1 is essential for naive T cell quiescence and homeostasis and that this regulation is dependent on IL-7–IL-7R.

Figure 7.

Foxp1-deficient naive CD8+ T cells proliferate in sublethally irradiated mice deficient in H2-Kb and H2-Db. (a) Proliferation of YFP+ Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP and CD45.1+ wild-type control donor CD8+ T cells 5 d and 7 d after transfer into sublethally irradiated recipient mice deficient in H2-Kb and H2-Db. (b) Phenotype characterization of donor CD8+ T cells as in a. (c) Proliferation of donor CD8+ T cells as in a 6 d after transfer into sublethally irradiated recipient mice deficient in H2-Kb and H2-Db treated with monoclonal anti-IL-7 plus monoclonal anti-IL-7Rα (α-IL-7 + α-IL-7R) or with the control antibodies mouse immunoglobulin G2b and rat immunoglobulin G2a (mouse IgG2b + rat IgG2a). Numbers above bracketed lines (a,c) indicate percent proliferating cells. Data are representative of at least two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

The mechanisms that maintain T cell quiescence and homeostasis need to be understood, as they control the balance between eliciting strong immune responses against pathogens and maintaining immunological tolerance to prevent autoimmunity. KLF2, a zinc-finger transcription factor, and Tob, a nuclear protein of the antiproliferative APRO family, have been reported to be important in the regulation of T cell quiescence37–39. Subsequent studies, however, have shown that KLF2 seems to regulate the migration rather than the quiescence of T cells40,41, and spontaneous T cell activation has not been reported in Tob-deficient mice1,42. In our study here, we have provided direct evidence that Foxp1 has an indispensable role in maintaining naive T cell quiescence, in part by repressing IL-7Rα expression. That view was supported by the following results: Foxp1-deficient naive CD8+ T cells gained effector phenotype and function in response to IL-7 but not in response to IL-4, and the amount of IL-7R was critical for the proliferation of Foxp1-deficient CD8+ T cells in response to IL-7 in vitro. In addition, Foxp1-deficient naive CD8+ T cells proliferated in vivo in lymphopenic mice deficient in H-2Kb and H-2Db in an IL-7-dependent manner.

Foxo1 is an activator of IL-7Rα expression in the T cell lineage28,29. Here we have shown that Foxp1 is a repressor of IL-7Rα expression. It also seemed that Foxp1 and Foxo1 had the ability to bind to the same predicted forkhead-binding site in the Il7r enhancer region, which suggests that these two transcription factors may compete for the binding and antagonize each other to regulate IL-7Rα expression in T cells. The finding that downregulation of IL-7Rα expression in the absence of Foxo1 was Foxp1 dependent indicates a potential role of Foxp1 in regulating Foxo1 function.

Foxp1 and Foxo1 have been shown to upregulate the expression of recombination-activating genes during early B cell development by binding to the same ‘Erag’ enhancer region32,43. However, neither transcription factor seems to regulate these genes in T lineage cell development32,43. Foxo1 affects IL-7Rα expression in early B lineage cells44, but deletion of Foxp1 does not affect IL-7Rα expression in pro-B cells32. These results suggest that Foxp1 and Foxo1 may interact in complex and distinct ways in different parts of the immune system. Depending on their interaction with other transcription factor families or various cofactors, Foxo proteins can alter transcriptional regulation by a variety of mechanisms27. It is likely that Foxp1 and Foxo1 act together with other cofactors to exert their functions. As Foxo1 targets many genes encoding molecules involved in important cellular processes, such as the cell cycle and metabolism25–27, further studies are needed to provide a complete picture of the relationship between Foxp1 and Foxo1 (and other Foxo proteins) in regulating T cell quiescence and homeostasis and other important cellular functions.

In addition to regulating IL-7Rα expression, Foxp1 seems to control other molecules critical for regulating T cell quiescence. Our results have shown that Foxp1 negatively regulates the MEK-Erk pathway. Transgenic mice expressing the oncogenic protein K-Ras develop T cell lymphoma and/or leukemia characterized by aberrantly high CD44 expression in thymocytes45, which is consistent with the activated phenotype of Foxp1-deficient thymocytes33. We attempted to introduce a dominant negative K-Ras to inhibit MEK-Erk signaling and determine whether it could restore the activated phenotype of Foxp1-deficient T cells in Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre mice. However, the dominant negative K-Ras almost completely blocked T cell development (data not shown). Nonetheless, we found that blocking MEK-Erk activation impaired the proliferation of Foxp1-deficient naive CD8+ T cells in response to IL-7 in vitro.

It has been shown that the MEK-Erk pathway can be regulated by IL-7R and signaling pathways other than TCR signaling46,47. Because Foxp1-deficient CD8+ T cells in which IL-7Rα expression was adjusted to nearly wild-type amounts still proliferated in response to IL-7 (whereas wild-type CD8+ T cells did not), blocking MEK-Erk activation probably inhibits pathways regulated by Foxp1, but independently of IL-7R-signaling. It has been proposed that constitutive low-intensity TCR signaling, independently of receptor ligation, has an important role in T cell development, and low Erk kinase activity is part of the TCR basal signaling48,49. Therefore, although the proliferation of Foxp1-deficient naive CD8+ T cells in response to IL-7 in vitro and in lymphopenic mice deficient in H-2Kb and H-2Db in vivo would indicate that there is no obvious TCR engagement, Foxp1 may regulate a basal TCR signal involving MEK-Erk activity. It is possible that in the absence of Foxp1, the integration of both enhanced IL-7R and basal TCR signals act together to drive the naive T cells to proliferate. The nature and role of basal TCR signaling in mature T cells remain unknown. Further studies are needed to address how MEK-Erk signaling is involved in the Foxp1 regulation of T cell quiescence in the absence of overt TCR stimulation.

Naive CD4+ T cells with acute deletion of Foxp1 did not proliferate in response to IL-7 in vitro. Although the underlying mechanism is not clear, this observation is consistent with published reports showing that CD8+ T cells are more responsive to IL-7 than CD4+ T cells in in vitro cultures9. Nevertheless, we have shown that naive CD4+ T cells in which Foxp1 was acutely deleted had proliferation in intact recipient mice similar to that of Foxp1-deficient naive CD8+ T cells, which indicates that Foxp1 controls T cell quiescence in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in vivo. In summary, our results have shown that Foxp1 exerts essential cell-intrinsic transcriptional regulation on the quiescence and homeostasis of naive T cells by negatively regulating IL-7Rα expression and MEK-Erk signaling. Our findings have demonstrated coordinated regulation that actively inhibits T cell activation signals and indicate that lymphocyte quiescence does not occur by default but is actively maintained.

ONLINE METHODS

Mice

All animals were maintained in specific pathogen–free barrier facilities and were used in accordance with protocols approved by Institutional Animal Care and User Committee of the Wistar Institute. C57BL/6 mice were from the National Cancer Institute. Cre-ERT2+, RosaYFP and Il7r−/− mice were from Jackson Laboratories. Cd4-Cre–transgenic mice, B6 CD45.1 congenic mice and mice deficient in H-2Kb and H-2Db were from Taconic.

Foxp1f/f mice were generated as described and have been backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice for at least five generations33. Foxp1f/f mice were crossed with Cd4-Cre–transgenic mice to generate Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre mice and control Foxp1+/+Cd4-Cre mice. Foxp1f/f mice were bred with Cre-ERT2+ mice and RosaYFP mice to generate Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP mice. Il7r−/− mice were bred with Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre and Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+ mice to generate Foxp1f/f Cd4-Cre Il7r+/− and Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFPIl7r+/− mice, respectively. Foxo1f/f mice (a gift from R.A. DePinho) were bred with Foxp1f/f mice to generate Foxp1f/fFoxo1f/f mice.

Flow cytometry, cell sorting and intracellular staining

These procedures were done as described33. The sorted populations were > 98% pure. Antibodies were as follows: peridinin chlorophyll protein–cyanine 5.5–conjugated anti-IFN-γ (XMG1.2), and phycoerythrin-conjugated anti-CD8 (H35-17.2), anti-IL-7Rα (A7R43), anti-CD69 (H1.2F3), anti-TCRβ (H57-597) and anti-IL-2 (JES5-5H4; all from eBioscence); and peridinin chlorophyll protein–cyanine 5.5–conjugated anti-CD4 (GK1.5) and anti-CD25 (PC61), Alexa Fluor 700–conjugated anti-CD44 (IM7), and allophycocyanin–conjugated anti-CD45.1 (A20) and anti-CD62L (MEL-14; all from BioLegend). Live/Dead Fixable Aqua Dead Cell fluorescence was from Invitrogen. Phycoerythrin-conjugated mouse antibody to human granzyme B (GB12; Caltag Laboratories) and antibody to phosphorylated Erk1 and Erk2 (41G9; Cell Signaling Technology) were used for intracellular staining of granzyme B and phosphorylated Erk1 and Erk2, respectively.

Cell Trace labeling and cell culture

A CellTrace Violet Cell Proliferation kit (Invitrogen) was used for analysis of cell proliferation. CD44lo (or CD44hi) CD4+ T cells or CD8+ T cells sorted from Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP and Foxp1f/fRosaYFP mice were washed twice with PBS and were incubated for 20 min at 37 °C at a density of 1 × 107 cells per ml in PBS with 1–2 μM CellTrace, then were washed with 10% (vol/vol) FBS in medium. CellTrace-labeled CD4+ T or CD8+ T cells were cultured for 6 d with or without recombinant mouse IL-7 (3 ng/ml, unless specified otherwise; R&D systems) or IL-4 (10 ng/ml), and 0.3 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen (Sigma) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS33. In some experiments, YFP+ cells and YFP− cells were sorted from Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP and Foxp1f/fRosaYFP cell cultures, respectively, at day 2, and were incubated for additional 4 d with IL-7. CellTrace profiles were assessed at various times. For chemical inhibition experiments, SB203580 (p38 inhibitor; Calbiochem) and U0126 (MEK1-MEK2 inhibitor; Cell Signaling Techonology) were added to the culture at day 4, and cell proliferation was analyzed 2 d later.

Real-time reverse-transcription PCR

Peripheral CD4+ or CD8+ T cells were isolated from 4- to 6-week-old Foxp1+/+Cd4-Cre or Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre mice and RNA was purified as described33. The primers for analysis of Il7r expression by real-time RT-PCR were 5′-GGAACAACTATGTAAGAAGCCAAAAACG-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAGATCATTGGGCAGAAAACTTTCC-3′ (reverse).

Immunoblot analysis

Sorted CD5lo DP thymocytes were incubated for 30 min on ice with anti-CD3 (5 μg/ml; 145-2C11; eBioscience) plus anti-CD28 (5 μg/ml; 37.51, eBioscience). After being crosslinked at various time points with goat antibody to hamster immunoglobulin G (20 μg/ml; 55397; MP Biomedicals), cells were lysed and SDS-PAGE was done as described33. Antibodies to phosphorylated Erk1–Erk2 (D13.14.4E), phosphorylated p38 (3D7), phosphorylated Jnk (81E11), phosphorylated MEK1–MEK2 (41G9), phosphorylated STAT5 (14H2), total Erk1–Erk2 (137F5) and total STAT5 (9310) were from Cell Signaling Technology. Rabbit polyclonal antibody to Foxp1 (generated with keyhole limpet hemocyanin–conjugated mouse Foxp1A peptide, amino acids 685–705; Abmart) and to Foxo1 (C29H4; Cell Signaling Technology) were used for immunoblot analysis of Foxp1 and Foxo1.

Retroviral transduction

Foxp1A cDNA was subcloned into the retroviral vector MSCV-IRES-EGFP (MigR1-GFP; a gift from W. Pear). MigR1-Cre-GFP was a gift from N.A. Speck. Purified peripheral CD4+ T and CD8+ T cells were activated for 20 h with anti-CD3 (0.5 μg/ml) plus anti-CD28 (1 μg/ml) in plates precoated with goat antibody to hamster immunoglobulin G (0.3 mg/ml) in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS plus recombinant human IL-2 (100 U/ml). Cells were transduced with virus-containing media supplemented with polybrene and were centrifuged for 2 h at 650g. Then, 24 h later, cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium supplemented with 10% (vol/vol) FBS and recombinant human IL-2 (100 U/ml).

Adoptive transfer and mixed–bone marrow chimeras

CD44lo CD8+ or CD4+ T cells sorted from 6- to 10-week-old Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP and CD45.1+ congenic wild-type mice were mixed and labeled with CellTrace, and about 6 × 106 cells were transferred into intact recipient mice by injection through the tail vein. Recipient mice were given 1 mg tamoxifen (Sigma) on the day before cell transfer and for the first 3 d after transfer. In some experiments, sorted CD44loCD8+ T cells were cultured for 2 d in vitro in medium with 0.3 μM 4-hydroxytamoxifen and 1 × 106 cells were transferred by injection into the tail vein into mice deficient in H-2Kb and H-2Db that had been sublethally irradiated (600 rads) 1 d before transfer. For in vivo blockade of IL-7R signaling50, recipient mice deficient in H-2Kb and H-2Db were treated with the following antibodies (500 ng each; all from Bio X Cell): monoclonal anti-IL-7 (M25) and monoclonal anti-IL-7Rα (A7R34), or control mouse immunoglobulin G2b (MPC11) and rat immunoglobulin G2a (2A3). Antibody ‘cocktails’ were administrated intraperitoneally every other day for a total of four times starting 1 d before cell transfer.

Bone marrow from CD45.1+ congenic Foxp1+/+Cd4-Cre (CD45.1+CD45.2+) mice and Foxp1f/fCd4-Cre (CD45.1−CD45.2+) mice was depleted of T cells and the resultant bone marrow cells were mixed at a ratio of approximately 1:1 before being transferred intravenously into lethally irradiated C57BL/6 CD45.1+ recipient mice as described33. Mixed–bone marrow chimeras were analyzed 6–10 weeks after reconstitution.

ChIP

ChIP assays were done as described32. Precipitated DNA and input DNA were assessed by quantitative real-time PCR with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). The sequences of the primer pairs used were as follows: Il7r promoter region, 5′-AAACCAGCTCTGTGCCTGCTAA AC-3′ and 5′-ACCTCTGCTTACAGCAGCAATCCT-3′; Il7r enhancer region, 5′-AGCCTTTCATGGGCTATCACTCCA-3′ and 5′-GAGCAAACTAGCAC ATGCTGTACC-3′; control region, 5′-ATGCCCTGGTAGGAATCAGAAG CA-3′ and 5′-TGAAGGCAGAACACAGGCTCATCA-3′.

EMSA

In vitro–translated mouse Foxp1A and Foxo1 were generated with the TNT reticulocyte lysate system (Promega). Oligonucleotides corresponding to the forkhead-binding site of the Il7r enhancer (5′-TCCACTTAAATGATAAAC AAGAGAATTTAAAG-3′) and mutated Il7r enhancer (5′-TCCACTTAAATG ATcacCAAGAGAATTTAAAG-3′; mutated bases in lower case) were annealed to their complementary strands and were purified with microspin G25 columns. EMSA was done as described32. In the competition assays, a 25-fold excess of unlabeled competitor primer was used. Supershift assays were done by incubation of in vitro–translated proteins with either monoclonal antibody to Foxp1 (1G1)32 or monoclonal antibody to NFAT1 (4G6-G5; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) at a concentration of 500 ng/ml in EMSA reaction buffer.

Statistics

A two-tailed Student’s t-test was used for calculation of P values.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank R.A. DePinho (Harvard Medical School) for Foxo1f/f mice; W. Pear (University of Pennsylvania) for the retroviral vector MigR1-GFP; N.A. Speck (University of Pennsylvania) for the retroviral vector MigR1-Cre-GFP; E. Pure and J.R. Conejo-Garcia for critical reading of the manuscript; A.J. Caton and A. Bhandoola for discussions; J.S. Faust, D.E. Ambrose and D.J. Hussey for technical help with flow cytometry; and M.S. Wright, M. Houston-Leslie and D. DiFrancesco for help at the Animal Facility of the Wistar Institute. Supported by the National Institutes of Health (1K22AI070317-01A1 to H.H.), American Cancer Society (114937-IRG-96-153-07-IRG to H.H.) and the Wistar Cancer Center (P30 CA10815).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

X.F., H.W. and H.H. designed the experiments; H.W. and X.F. did the phenotypic and functional analysis of Foxp1f/fCre-ERT2+RosaYFP T cells in vitro; X.F. did all analyses of IL-7R expression, EMSA, in vitro proliferation of T cells from various Il7r+/− mice, mixed–bone marrow chimeras and cell transfer into mice deficient in H-2Kb and H-2Db with some help from H.T. and T.J.D.; H.W. did all retroviral infections, ChIP, cell signaling, immunoblot analysis, analysis of Foxp1f/fFoxo1f/f T cells and cell transfer into intact recipient mice with some help from H.T. and T.J.D.; H.T. did the phenotypic analysis of the Il7r+/− mice; T.J.D. did all mouse breeding with help from J.W.; H.H. conceived of the research, directed the study and provided overall supervision; and X.F., H.W., T.J.D. and H.H. prepared the manuscript. Authors with equal contributions are listed in alphabetical order.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Reprints and permissions information is available online at http://www.nature.com/reprints/index.html.

Supplementary information is available on the Nature Immunology website.

References

- 1.Yusuf I, Fruman DA. Regulation of quiescence in lymphocytes. Trends Immunol. 2003;24:380–386. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4906(03)00141-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tzachanis D, Lafuente EM, Li L, Boussiotis VA. Intrinsic and extrinsic regulation of T lymphocyte quiescence. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:1959–1967. doi: 10.1080/1042819042000219494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ernst B, Lee DS, Chang JM, Sprent J, Surh CD. The peptide ligands mediating positive selection in the thymus control T cell survival and homeostatic proliferation in the periphery. Immunity. 1999;11:173–181. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80092-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kieper WC, Jameson SC. Homeostatic expansion and phenotypic conversion of naive T cells in response to self peptide/MHC ligands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:13306–13311. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cho BK, Rao VP, Ge Q, Eisen HN, Chen J. Homeostasis-stimulated proliferation drives naive T cells to differentiate directly into memory T cells. J Exp Med. 2000;192:549–556. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.4.549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Waterhouse P, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in Ctla-4. Science. 1995;270:985–988. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li MO, Sanjabi S, Flavell RA. Transforming growth factor-β controls development, homeostasis, and tolerance of T cells by regulatory T cell-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Immunity. 2006;25:455–471. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:191–197. doi: 10.1038/ni1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tan JT, et al. IL-7 is critical for homeostatic proliferation and survival of naive T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:8732–8737. doi: 10.1073/pnas.161126098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Surh CD, Sprent J. Homeostasis of naive and memory T cells. Immunity. 2008;29:848–862. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takada K, Jameson SC. Naive T cell homeostasis: from awareness of space to a sense of place. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:823–832. doi: 10.1038/nri2657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Su B, Karin M. Mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades and regulation of gene expression. Curr Opin Immunol. 1996;8:402–411. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(96)80131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang J, et al. p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase mediates signal integration of TCR/CD28 costimulation in primary murine T cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:3819–3829. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rincon M, et al. The JNK pathway regulates the In vivo deletion of immature CD4+CD8+ thymocytes. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1817–1830. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.10.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Alberola-Ila J, Forbush KA, Seger R, Krebs EG, Perlmutter RM. Selective requirement for MAP kinase activation in thymocyte differentiation. Nature. 1995;373:620–623. doi: 10.1038/373620a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fischer AM, Katayama CD, Pages G, Pouyssegur J, Hedrick SM. The role of erk1 and erk2 in multiple stages of T cell development. Immunity. 2005;23:431–443. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.D’Souza WN, Chang CF, Fischer AM, Li M, Hedrick SM. The Erk2 MAPK regulates CD8 T cell proliferation and survival. J Immunol. 2008;181:7617–7629. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.11.7617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peschon JJ, et al. Early lymphocyte expansion is severely impaired in interleukin 7 receptor-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1994;180:1955–1960. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schluns KS, Kieper WC, Jameson SC, Lefrancois L. Interleukin-7 mediates the homeostasis of naive and memory CD8 T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:426–432. doi: 10.1038/80868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazzucchelli R, Durum SK. Interleukin-7 receptor expression: intelligent design. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:144–154. doi: 10.1038/nri2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chandele A, et al. Formation of IL-7Rαhigh and IL-7Rαlow CD8 T cells during infection is regulated by the opposing functions of GABPα and Gfi-1. J Immunol. 2008;180:5309–5319. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doan LL, et al. Growth factor independence-1B expression leads to defects in T cell activation, IL-7 receptor α expression, and T cell lineage commitment. J Immunol. 2003;170:2356–2366. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee HC, Shibata H, Ogawa S, Maki K, Ikuta K. Transcriptional regulation of the mouse IL-7 receptor α promoter by glucocorticoid receptor. J Immunol. 2005;174:7800–7806. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.12.7800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xue HH, et al. GA binding protein regulates interleukin 7 receptor α-chain gene expression in T cells. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:1036–1044. doi: 10.1038/ni1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carlsson P, Mahlapuu M. Forkhead transcription factors: key players in development and metabolism. Dev Biol. 2002;250:1–23. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2002.0780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greer EL, Brunet A. FOXO transcription factors at the interface between longevity and tumor suppression. Oncogene. 2005;24:7410–7425. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van der Vos KE, Coffer PJ. FOXO-binding partners: it takes two to tango. Oncogene. 2008;27:2289–2299. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kerdiles YM, et al. Foxo1 links homing and survival of naive T cells by regulating L-selectin, CCR7 and interleukin 7 receptor. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:176–184. doi: 10.1038/ni.1689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ouyang W, Beckett O, Flavell RA, Li MO. An essential role of the Forkhead-box transcription factor Foxo1 in control of T cell homeostasis and tolerance. Immunity. 2009;30:358–371. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li C, Tucker PW. DNA-binding properties and secondary structural model of the hepatocyte nuclear factor 3/fork head domain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:11583–11587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang B, et al. Foxp1 regulates cardiac outflow tract, endocardial cushion morphogenesis and myocyte proliferation and maturation. Development. 2004;131:4477–4487. doi: 10.1242/dev.01287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hu H, et al. Foxp1 is an essential transcriptional regulator of B cell development. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:819–826. doi: 10.1038/ni1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng X, et al. Foxp1 is an essential transcriptional regulator for the generation of quiescent naive T cells during thymocyte development. Blood. 2010;115:510–518. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-232694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ruzankina Y, et al. Deletion of the developmentally essential gene ATR in adult mice leads to age-related phenotypes and stem cell loss. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Srinivas S, et al. Cre reporter strains produced by targeted insertion of EYFP and ECFP into the ROSA26 locus. BMC Dev Biol. 2001;1:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-1-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park JH, et al. Suppression of IL7Rα transcription by IL-7 and other prosurvival cytokines: a novel mechanism for maximizing IL-7-dependent T cell survival. Immunity. 2004;21:289–302. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kuo CT, Veselits ML, Leiden JM. LKLF: a transcriptional regulator of single-positive T cell quiescence and survival. Science. 1997;277:1986–1990. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5334.1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tzachanis D, et al. Tob is a negative regulator of activation that is expressed in anergic and quiescent T cells. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:1174–1182. doi: 10.1038/ni730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Buckley AF, Kuo CT, Leiden JM. Transcription factor LKLF is sufficient to program T cell quiescence via a c-Myc–dependent pathway. Nat Immunol. 2001;2:698–704. doi: 10.1038/90633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carlson CM, et al. Kruppel-like factor 2 regulates thymocyte and T-cell migration. Nature. 2006;442:299–302. doi: 10.1038/nature04882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sebzda E, Zou Z, Lee JS, Wang T, Kahn ML. Transcription factor KLF2 regulates the migration of naive T cells by restricting chemokine receptor expression patterns. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:292–300. doi: 10.1038/ni1565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoshida Y, et al. Negative regulation of BMP/Smad signaling by Tob in osteoblasts. Cell. 2000;103:1085–1097. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00211-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amin RH, Schlissel MS. Foxo1 directly regulates the transcription of recombination-activating genes during B cell development. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:613–622. doi: 10.1038/ni.1612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dengler HS, et al. Distinct functions for the transcription factor Foxo1 at various stages of B cell differentiation. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1388–1398. doi: 10.1038/ni.1667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kindler T, et al. K-RasG12D-induced T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma/leukemias harbor Notch1 mutations and are sensitive to γ-secretase inhibitors. Blood. 2008;112:3373–3382. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-147587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maki K, Ikuta K. MEK1/2 induces STAT5-mediated germline transcription of the TCRγ locus in response to IL-7R signaling. J Immunol. 2008;181:494–502. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peyssonnaux C, Eychene A. The Raf/MEK/ERK pathway: new concepts of activation. Biol Cell. 2001;93:53–62. doi: 10.1016/s0248-4900(01)01125-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Roose JP, et al. T cell receptor-independent basal signaling via Erk and Abl kinases suppresses RAG gene expression. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E53. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zikherman J, et al. CD45-Csk phosphatase-kinase titration uncouples basal and inducible T cell receptor signaling during thymic development. Immunity. 2010;32:342–354. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tan JT, et al. Interleukin (IL)-15 and IL-7 jointly regulate homeostatic proliferation of memory phenotype CD8+ cells but are not required for memory phenotype CD4+ cells. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1523–1532. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.