Abstract

Background and Purpose

To test a hypothesis that: (i) duodenal pH and osmolarity are individually controlled at constant set points by negative feedback control centred in the enteric nervous system (ENS); (ii) the purinergic P2Y1 receptor subtype is expressed by non-cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons, which represent the final common excitatory pathway from the ENS to the bicarbonate secretory glands.

Experimental Approach

Ussing chamber and pH-stat methods investigated involvement of the P2Y1 receptor in neurogenic stimulation of mucosal bicarbonate (HCO3−) secretion in guinea pig duodenum.

Key Results

ATP increased HCO3− secretion with an EC50 of 160 nM. MRS2179, a selective P2Y1 purinergic receptor antagonist, suppressed ATP-evoked HCO3− secretion by 47% and Cl− secretion by 63%. Enteric neuronal blockade by tetrodotoxin or exposure to a selective vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP, VPAC1) receptor antagonist suppressed ATP-evoked HCO3− secretion by 61 and 41%, respectively, and Cl- by 97 and 70% respectively. Pretreatment with the muscarinic antagonist, scopolamine did not alter ATP-evoked HCO3− or Cl− secretion.

Conclusion and Implications

Whereas acid directly stimulates the mucosa to release ATP and stimulate HCO3− secretion in a cytoprotective manner, neurogenically evoked HCO3− secretion accounts for feedback control of optimal luminal pH for digestion. ATP stimulates duodenal HCO3− secretion through an excitatory action at purinergic P2Y1 receptors on neurons in the submucosal division of the ENS. Stimulation of the VIPergic non-cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons, which are one of three classes of secretomotor neurons, accounts for most, if not all, of the neurogenic secretory response evoked by ATP.

Keywords: duodenum, neurogastroenterology, bicarbonate secretion, ATP, ADP, purinergic receptors, vasoactive intestinal peptide, secretomotor neurons, autonomic nervous system, enteric nervous system

Introduction

Purinergic signalling

The extracellular nucleotides, ATP, ADP, UTP and UDP, mediate a multitude of physiological functions by stimulating P2X1–7 and P2Y1,2,4,6,11–14 purinergic receptors in several tissues and organs (Burnstock, 2007; 2008). Cell surface ectonucleotidases act to break these nucleotides down to nucleosides, some of which also bind to purinergic receptors. Adenosine is one of the nucleosides, which has important signalling functions in the enteric nervous system (ENS) and systems elsewhere (Burnstock, 2006; Gourine et al., 2009). Adenosine accumulates spontaneously in guinea pig intestinal preparations where it might activate one or more of four receptors consisting of A1, A2a, A2b and A3 types (Christofi and Wood, 1993; Christofi et al., 2001).

Bicarbonate secretion

Roles for HCO3− secretion, epithelial release of ATP and purinergic P2Y receptor subtypes in mucosal defence against acid injury in the duodenum are implicit historically and have received comprehensive reviews (Kaunitz and Akiba, 2011; Takeuchi et al., 2011; Ham et al., 2012; Seidler and Sjöblom, 2012). Exposure of enterocyte apical surfaces to protons is believed to trigger release of ATP, which acts at P2Y purinergic receptors and their postreceptor signalling pathways to elevate intracellular Ca2+ and open HCO3− secretory channels. Negative feedback regulation, which occurs in this case, involves elevation of HCO3− secretion and stimulation of brush border alkaline phosphatase by the elevated pH. Elevation of alkaline phosphatase activity hydrolyses ATP, which decreases the concentration of ATP at the P2Y receptors and thereby slows acid-associated HCO3− secretion until lowering of the pH again stimulates HCO3− secretion (reviewed by Ham et al., 2012).

The pH for optimal activity of pancreatic enzymes in the small intestine is routinely reported to be in an alkaline range of 6.7–8.0 (Worthington and Zacka, 1994). Aside from mechanisms of mucosal protection, neurogenic control of HCO3− secretion is assumed to establish and maintain optimal pH for the activity of luminal digestive enzymes. Recognition of the ENS as an independent integrative nervous system (i.e. a brain-in-the-gut) presumes that ENS regulatory control, akin to central nervous control of autonomic functions such as blood pressure and body temperature, obeys the principles of automatic cybernetic control theory (Weiner, 1948). These kinds of negative feedback control systems include a controlling system, a controlled system and a detector for the regulated parameter, each of which is believed to be a property of the ENS (Wood, 2010). Determination of a set point and generation of precise control signals to the controlled system are properties of a controlling system. Sensors for output parameters continuously provide information for negative feedback computation of deviation from the set point (i.e. the error signal). Control signals increase or decrease the output from the controlled system to return the detected parameter towards the set point for the parameter, which in the intestine may be osmolarity or pH in the lumen or muscle contractile tension. The ENS, most likely, holds the pH and osmolarity of the digestive milieu at set point by adjusting, in up or down manner, the secretion of HCO3− and Cl− from the intestinal secretory glands in response to perturbations in the lumen. Enteric secretomotor neurons in the submucosal plexus are final motor pathways from the ENS control circuitry to the secretory glands. Secretomotor firing frequency can be adjusted, up or down, to increase or decrease secretory output of HCO3− or Cl− and thereby adjust pH or osmolarity to the set point.

Secretomotor neurons express purinergic P2Y1 receptors as revealed by expression of the P2Y1 mRNA transcript, P2Y1 receptor protein and immunoreactivity for the P2Y1 receptor (Hu et al., 2003; Cooke et al., 2004; Fang et al., 2006). Cloning confirms expression of a functional P2Y1 receptor by secretomotor neurons (Gao et al., 2006). ATP is a neurotransmitter that acts at these receptors to evoke slow EPSPs and elevated firing of the neurons (Hu et al., 2003). Axons that release ATP at synapses with secretomotor neurons are derived from neurons that project from the myenteric plexus, from neighbouring neurons in the submucosal plexus and from sympathetic postganglionic neurons (Hu et al., 2003). The P2Y1-mediated slow EPSPs occur mainly in the non-cholinergic/vasodilator secretomotor neurons that release vasoactive intestinal peptide (VIP) at neuroepithelial junctions.

Chloride secretion

Electrical stimulation of secretomotor neurons in Ussing flux chambers evokes increases in electrogenic short-circuit current (Isc) that reflects Cl− secretion from serosal to luminal sides of the preparations (Hubel, 1978; Cooke et al., 1983a,b; Fang et al., 2006; Fei et al., 2010). Application of ATP evokes increases in Isc that mimic responses to transmural electrical field stimulation (Fang et al., 2006). Neural blockade with tetrodotoxin (TTX), blockade of VIP receptors or exposure to the selective P2Y1 receptor antagonist, MRS2179, suppresses the increases in Isc evoked by electrical field stimulation (Fang et al., 2006; Fei et al., 2010).

In view of the evidence for neurogenic control of Cl− secretion and thereby control of luminal osmolarity and liquidity, and in view of the putative significance of neurogenic HCO3− in set point control of luminal pH, we studied neurally mediated HCO3− secretion in concert with neurogenic Cl− secretion. We concentrated on the duodenum because of the importance of pH control for enzymatic digestion and an earlier finding that transcription levels for P2Y1 receptor mRNA in the guinea pig submucosal plexus varied in different regions with highest expression occurring in the duodenum and the lowest in the proximal and distal colon (Fang et al., 2006). Some of the results have been published in abstract form (Fei et al., 2006).

Methods

Tissue preparation

Male Albino Hartley-strain guinea pigs, 8–10 weeks old and weighing 300–350 g, were used. They were allowed food and water ad libitum until 1 h before each experiment when they were deprived of food and water. Stunning by a sharp blow to the head, followed immediately by exsanguination from the cervical vessels, according to a protocol approved by The Ohio State University Laboratory Animal Care and Use Committee and United States Department of Agriculture Veterinary Inspectors, was used to kill the guinea pigs. A 2 cm segment of proximal duodenum was removed and immediately immersed in ice-cold unbuffered oxygenated bicarbonate-free solution containing indomethacin (1 μM) to suppress trauma-induced prostaglandin release and its effects on HCO3− secretion (Seidler and Sjöblom, 2012). The duodenal segment was opened along the mesenteric border and the muscularis externa, together with the myenteric plexus, was removed in cold bicarbonate-free indomethacin-containing solution. The submucosal plexus remained intact with the mucosa. The ‘stripped’ duodenal submucosal/mucosal preparation from each animal was divided and mounted in four Ussing flux chambers. All studies involving animals are reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals (Kilkenny et al., 2010; McGrath et al., 2010).

Ussing flux chambers and pH-stat

The Ussing chambers were equipped with pairs of Ag/AgCl electrodes connected with Krebs-agar bridges to calomel half-cells for measurement of transmural potential difference (PD). Another pair of electrodes was connected to an automated voltage clamp apparatus, which compensated for the solution resistance between the sensing bridges for voltage potential difference. The flat-sheet preparations were mounted between halves of Ussing chambers that had apertures of 0.64 cm2. The mucosal side of the tissue was bathed with unbuffered bicarbonate-free solution bubbled with 100% O2. The serosal side was bathed with Krebs solution bubbled with 95% O2/5% CO2. Each compartment of the Ussing chambers held a volume of 10 mL warmed to 37°C by circulation from a temperature-controlled water bath.

A pH-stat system (TIM856; Radiometer Analytical, Villeurbanne, France) automatically controlled the luminal solution at pH 7.4 by infusion of 5 mM HCl in response to changes in pH that were monitored in real time. The volume of HCl titrated per unit time was measured and used to quantify the rate of HCO3− secretion. Measurements were recorded at 5 min intervals and averaged for each consecutive 10 min interval. The experiments were done under continuous short-circuit conditions with the DVC-1000 Voltage/Current Clamp System from World Precision Instruments (Sarasota, FL, USA) to maintain the electrical potential difference (PD) at 0. The open-circuit PD was measured for less than 2 s at each time point. Data were normalized to the cross-sectional area of the preparations. Rate of HCO3− secretion was expressed as μmol·cm−2·h−1. Isc was expressed as microamperes (μA)·cm−2. PD was measured in millivolts. Both measurements were recorded at 10 min intervals.

After mounting the tissues in the chambers, HCO3− secretion, Isc and PD were allowed to stabilize for 20–30 min before recording was begun. Basal parameters were then measured for a 30 min period. Reagents were applied to the serosal side of the preparation and the changes in HCO3− secretion and Isc (ΔIsc) were recorded during a 60 min period following application of each reagent. ATP-evoked responses were analysed in the presence or absence of selective reagents (e.g. receptor agonists and antagonists), which might suppress or enhance the responses. Effects of chloride-depleted media were investigated by removing Cl− from the solution in the mucosal and serosal sides of the Ussing chambers.

Chemicals and solutions

ATP, adenosine 5′-diphosphate (ADP), TTX, suramin, scopolamine, indomethacin and ARL67156 (6-N, N-diethyl-β-γ-dibromomethylene-D-adenosine-5-triphosphate) were purchased from Sigma Chemicals (St. Louis, MO, USA). MRS 2179 (2′-deoxy-N6-methyladenosine 3′,5′-bisphosphate tetraammonium salt) and MRS 2500 (1R*,2S*)-4-[2-iodo-6-(methylamino)-9H-purin-9-yl]-2-(phosphonooxy)bicyclo[3.1.0]hexane-1-methanol dihydrogen phosphate ester tetraammonium salt were purchased from Tocris (Elisville, MO, USA). The selective vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VPAC1) receptor antagonist (Gourlet et al., 1997) [Ac-His1, D-Phe2, Lys15, Arg16, Leu27]-VIP (1–7)/GRF (8–27) was purchased from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (Belmont, CA, USA). Stock solutions were prepared in deionized H2O except for indomethacin, which was solubilized in dimethyl sulfoxide. Volumes added to 10 mL bathing solutions did not exceed 30 μL.

The composition of mucosal solution was (in mM): 121 NaCl, 6 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 15.7 Na gluconate, 11.5 mannitol and 0.001 indomethacin. The composition of the serosal solution (Krebs solution) was (in mM): 121 NaCl, 6 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 1.4 NaH2PO4, 14.3 NaHCO3, 11.5 glucose and 0.001 indomethacin. The normal Krebs solution on mucosal and serosal sides was buffered at pH 7.4. Chloride-depleted solution was prepared by substituting NaCl, CaCl2, KCl and MgCl2 with Na gluconate, Ca gluconate, K2SO4 and MgSO4 respectively. The pH of the Cl− depleted solution was pH 7.5–7.6 when gassed with 100% O2.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as means ± SEM with n-values given as numbers of animals. Student's t-test was used to calculate the statistical significance of differences between paired or unpaired data. When more than two means were compared, one-way anova was used to determine the significance of differences among means. When significant differences were indicated by anova, multiple-range testing with the Newman–Keuls test was performed. Values of P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Continuous curves for concentration–response relationships were constructed with the following least-squares fitting routine using Sigmaplot® software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA): V = Vmax/[1 + (EC50/C)nH], where V is the observed increased Isc, Vmax is the maximal response, C is the corresponding drug concentration, EC50 is the concentration that induces the half-maximal response, and nH is the apparent Hill coefficient.

Results

Effects of ATP and ADP on bicarbonate and chloride secretion

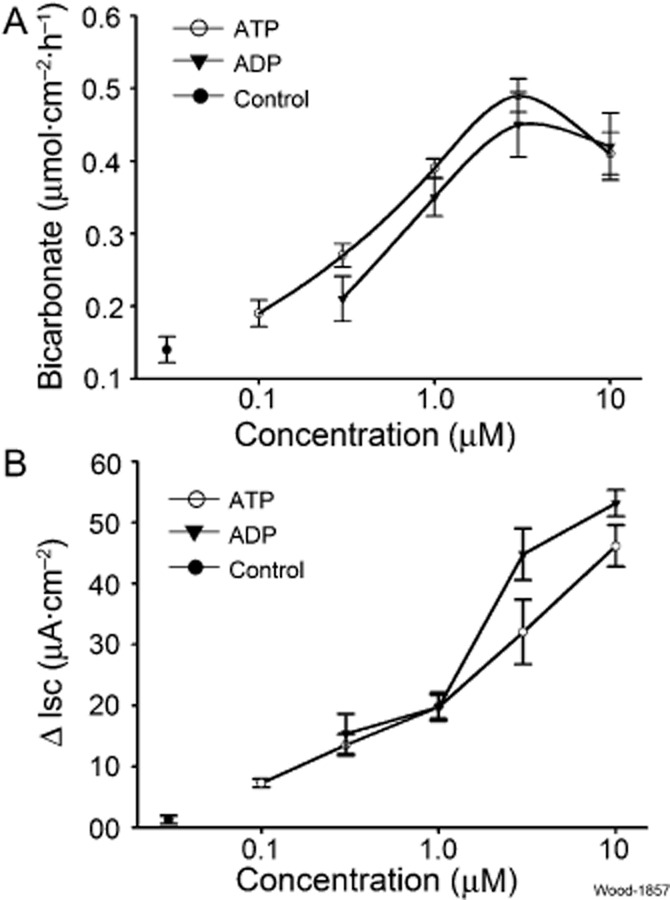

Exposure to ATP, added to the serosal side of the preparations, increased HCO3− secretion over a range of concentrations between 0.1 and 3.0 μM with an EC50 of 0.16 μM (Figure 1A). The maximal response occurred at 3.0 μM followed by a decline between 3.0 and 10 μM. The maximal net increase in HCO3− secretion after application of ATP (3.0 μM) was 0.49 ± 0.023 μmol·cm−2·h−1 (n = 6, P < 0.0001, compared to control). Action of ADP, one of the products of ATP hydrolysis by ATPases, was similar to that of ATP with the exception of lesser relative potency. Exposure to ADP increased HCO3− secretion in a concentration-dependent manner with an EC50 of 0.33 μM calculated for concentrations between 0.5 and 3.0 μM (Figure 1A). There was no significant difference between the maximal responses evoked by ATP or ADP, prior to the fall-off of secretion at the highest concentration (P > 0.05).

Figure 1.

Stimulation of mucosal HCO3− and Cl− (i.e. ΔIsc) secretion by ATP or ADP in guinea pig duodenum. (A) Peak HCO3− secretion evoked by ATP or ADP was concentration dependent with an EC50 of 0.16 μM for ATP and an EC50 of 0.33 μM for ADP. The maximal response to ATP or ADP occurred at 3 μM. (B) Stimulation of Isc as a surrogate for Cl− secretion in the same preparations. Values are expressed as means ± SEM; n = 6 animals for each series of four preparations.

Both ATP and ADP stimulated Cl− secretion (i.e. Isc) in concentration-dependent manner in concentrations between 0.5 and 10 μM (Figure 1B). Nevertheless, the patterns of concentration dependence in this range did not allow calculation of meaningful EC50 values. The relative potency for stimulation of Isc in the range of 1.0–10 μM was greatest for ADP (Figure 1B).

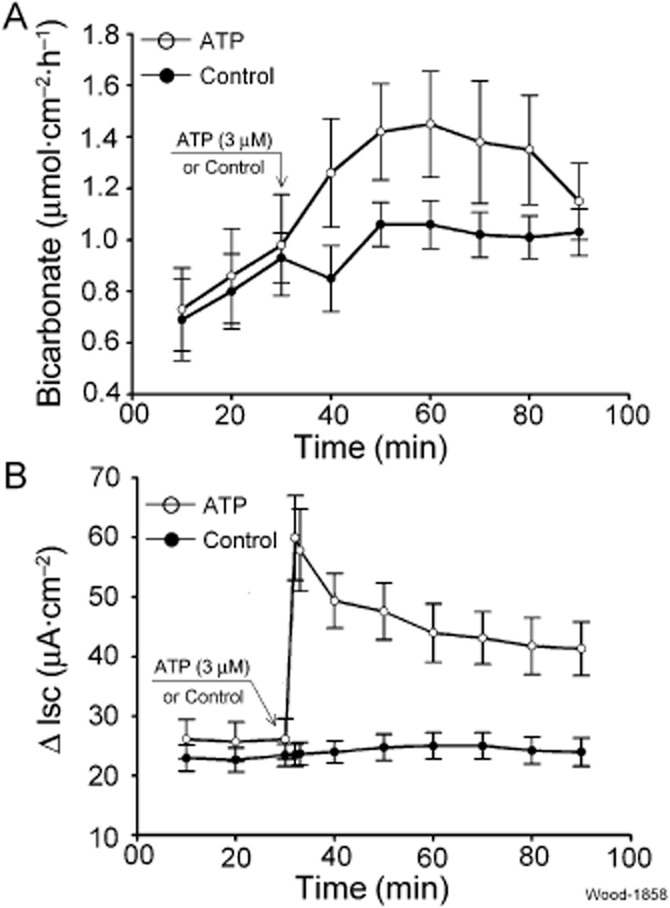

The time courses for HCO3− secretory responses and changes in Isc, in response to ATP, occurred in different patterns. The HCO3− secretory responses were relatively slow, reaching a peak at 20–30 min after application of ATP (Figure 2A). HCO3− secretory rate in the absence of ATP was relatively stable. In adjacent Ussing chambers, ATP (3 μM) evoked a sharp increase in Isc with maximal responses reached within 2 min after application (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Time course for stimulation of mucosal HCO3− and Cl− (i.e. ΔIsc) secretion by ATP and vehicle control in guinea pig duodenum. (A) ATP-evoked HCO3− secretion. ATP (3 μM) or vehicle control was applied to the submucosal side of the preparations at the time indicated by the arrow. HCO3− secretory responses were slow, in the range of 20–30 min for peak responses, relative to evoked changes in Isc, which reflected Cl− secretion. (B) ATP evoked a rapid increase in Isc with a peak being reached within 2 min after application of ATP. Values are expressed as means ± SEM; n = 6 animals for each series of four preparations.

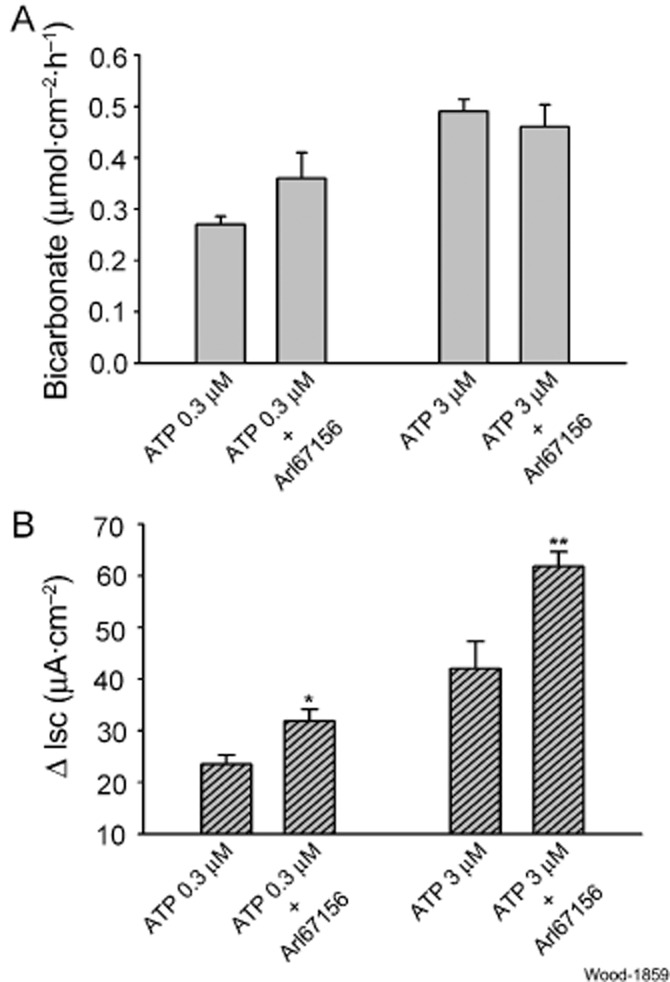

Effects of ARL67156 on ATP-evoked secretory responses

ARL67156, an ecto-ATPase inhibitor, prevents degradation of P2 purinoceptor agonists, including ATP, and thereby prolongs and enhances ATP action at its cell surface receptors (Levesque et al., 2007). We used it as a tool to help distinguish actions of ATP itself from those of its enzymatically generated metabolites (i.e. ADP, AMP or adenosine). ARL67156 (10 μM) was placed in the serosal-side compartment of the chambers 20 min prior to addition of ATP. Secretion of HCO3−, evoked by either 0.3 or 3.0 μM ATP, was not increased significantly (P > 0.05) by pretreatment with ARL67156 (Figure 3A). Pretreatment with ARL67156 did not increase the mean HCO3− secretion evoked by the relatively low concentration of 0.3 μM ATP (ATP: 0.27 ± 0.016 vs. ARL67156 + ATP: 0.36 ± 0.06 μmol·cm−2·h−1, P = 0.15, n = 6). ARL67156 did not change HCO3− secretion evoked by a higher concentration of 3 μM ATP (Figure 3A).

Figure 3.

Effects of suppression of ATP hydrolysis by ARL67156, an ecto-ATPase inhibitor, on ATP-evoked mucosal HCO3− secretion and Isc, as a measure of Cl− secretion. (A) Effects of 10 μM ARL67156 on HCO3− secretory responses to 0.3 or 3.0 μM ATP. ARL67156 was added to the submucosal side of the preparations 20 min before applying ATP. ARL67156 did not alter ATP-evoked secretion of HCO3−. (B) Effects of 10 μM ARL67156 on Isc evoked by 0.3 or 3.0 μM ATP in the same preparations. Suppression of ATP hydrolysis by the ecto-ATPase inhibitor enhanced Isc, which reflected Cl− secretory responses to ATP. Values are expressed as means ± SEM; n = 6 animals for each series of four preparations. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 (compared with response to ATP without pretreatment).

In contrast to ATP-evoked HCO3− secretion, pretreatment with ARL67156 significantly increased ATP-evoked stimulation of Isc (Figure 3B). Isc, evoked by 0.3 μM ATP, increased by 62.2% in the presence of ARL67156 (ATP: 13.5 ± 1.7 vs. ARL67156 + ATP: 21.9 ± 2.3 μA·cm−2, P < 0.05, n = 6). Isc, evoked by 3 μM ATP, was increased by 61.7% (ATP: 32.03 ± 5.3 vs. ARL67156 + ATP: 51.8 ± 2.8 μA·cm−2, P < 0.01, n = 6).

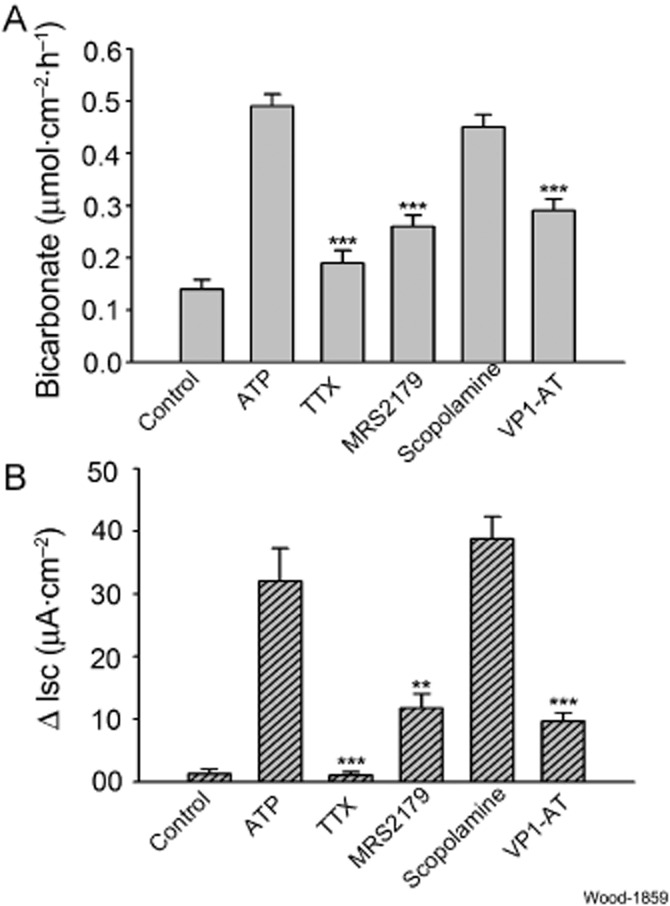

TTX and receptor antagonists

We used the neural blocker, TTX, as a tool to determine if the stimulatory action of ATP on HCO−3 secretion might be mediated through an excitatory action of ATP on secretomotor neurons in the submucosal plexus. TTX (0.5 μM) was placed in the serosal compartment of the chambers 20 min prior to application of 3 μM ATP. The presence of TTX suppressed ATP-evoked HCO3 secretion by 61.2% (ATP: 0.49 ± 0.023 vs. TTX + ATP: 0.19 ± 0.024 μmol·cm−2·h−1, P < 0.001, n = 6) (Figure 4A). TTX suppressed ATP-evoked Isc responses by 96.7% (P < 0.001) (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Effects of neural blockade and pharmacological receptor antagonists on ATP-evoked mucosal HCO3− secretion and Isc, as a measure of Cl− secretion. (A) Effects on ATP-evoked mucosal HCO3− secretion. ATP (3 μM) was applied to the submucosal side of the preparations in each study. Neuronal blockade with 0.5 μM TTX suppressed ATP-evoked secretion of HCO3−. Blockade of purinergic P2Y1 receptors by the selective antagonist, MRS2179 (10 μM) suppressed ATP-evoked HCO3− secretory responses. Blockade of muscarinic receptors by the selective antagonist, scopolamine (10 μM), did not alter ATP-evoked secretion of HCO3−. Blockade of receptors for vasoactive intestinal peptide by the selective antagonist, VP1-AT (1.0 μM), suppressed ATP-evoked HCO3− secretory responses. (B) Effects on ATP-evoked Isc, which served as a surrogate for Cl− secretion. ATP (3 μM) was applied to the submucosal side of the preparations in each case. Neuronal blockade with 0.5 μM TTX suppressed ATP-evoked increases in Isc. Blockade of purinergic P2Y1 receptors by the selective antagonist, MRS2179 (10 μM), suppressed ATP-evoked increases in Isc. Blockade of muscarinic receptors by the selective antagonist, scopolamine (10 μM), did not alter ATP-evoked increases in Isc. Blockade of receptors for vasoactive intestinal peptide by the selective antagonist, VP1-AT (1.0 μM), suppressed ATP-evoked increases in Isc. Values are expressed as means ± SEM; n = 6 animals for each series of four preparations. ***P < 0.001 (compared with response to ATP in physiological Cl−).

We used the selective P2Y1 receptor antagonist, MRS2179, to study P2Y1 receptor involvement in HCO3− secretion evoked by ATP (Boyer et al., 1998). MRS2179 (10 μM) was placed in the bathing solution in the serosal compartment of the Ussing chambers 20 min before applying ATP (3 μM). The presence of MRS2179 suppressed ATP-evoked HCO3− secretion by 47% (ATP: 0.49 ± 0.023 vs. MRS2179 + ATP: 0.26 ± 0.022 μmol·cm−2·h−1, P < 0.001, n = 6), and suppressed Isc by 63% (P < 0.002) (Figure 4A, B).

Firing of secretomotor neurons releases acetylcholine and/or VIP as neurotransmitters at the neuroepithelial junctions and stimulates secretion via cholinergic and VIPergic receptors expressed by the enterocytes (Bornstein et al., 2012). To investigate which of the two kinds of neurotransmitters might be involved in stimulation of HCO3− secretion by ATP, we used the muscarinic receptor antagonist, scopolamine, to selectively inhibit the effects of purinergic stimulation of cholinergic secretomotor neurons, and the selective VIP receptor antagonist, VPAC1, to selectively inhibit the effects of purinergic stimulation of the neurons that release VIP. Pretreatment with 10 μM scopolamine 20 min prior to application of 3 μM ATP had no effect on ATP-evoked stimulation of HCO3− secretion or on changes in Isc (Figure 4A, B). Placement of 1 μM VPAC1 receptor antagonist in the chambers, 10 min before application of 3 μM ATP, suppressed ATP-evoked HCO3− secretion by 41% (ATP: 0.49 ± 0.023 vs. VIP1 antagonist + ATP: 0.2 9 ± 0.022 μmol·cm−2·h−1, P < 0.001, n = 6). The same pretreatment with the VIP receptor antagonist suppressed Isc by 70% (Figure 4A, B). Stimulation of Isc by ATP was unaffected by muscarinic blockade with scopolamine.

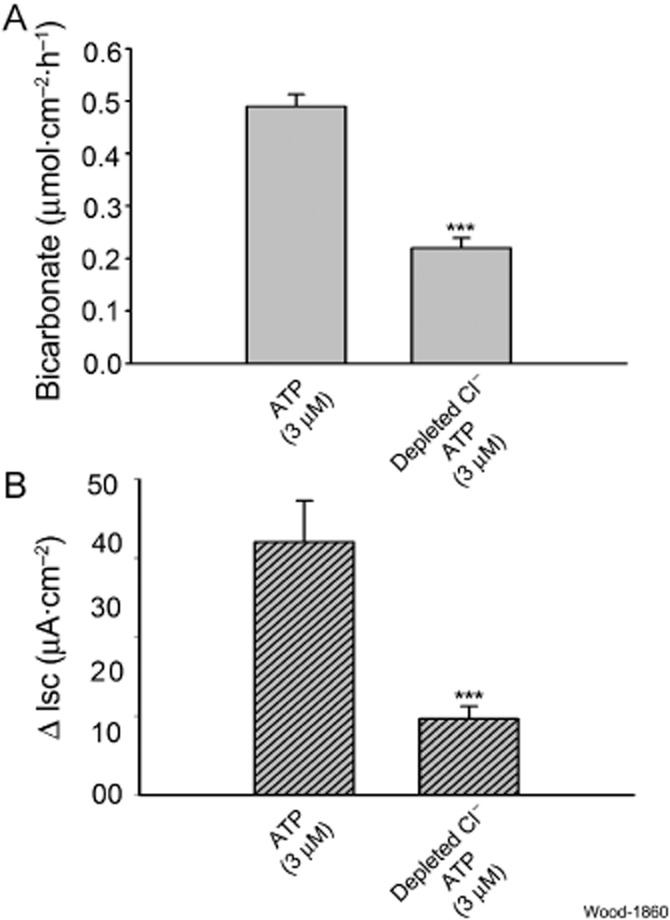

Effects of Cl− removal

Transport proteins mediate the exchange of Cl− for HCO3− across the enterocyte basolateral membrane when HCO3− is extruded from the cell. Exchange is one-to-one and electroneutral. We investigated the putative involvement of HCO3−/Cl− exchange in ATP-evoked HCO3− secretion by substituting gluconate for Cl− in the chambers bathing both sides of the preparations. ATP (3 μM) was added to the serosal side of the preparations after basal parameters were recorded for 30 min in bathing media with depleted Cl−. Reduced Cl− suppressed ATP-evoked HCO3− secretion by 55% (reduced Cl− solution: 0.22 ± 0.02 vs. physiological Cl− solution: 0.49 ± 0.023 μmol·cm−2·h−1, P < 0.001, n = 6). Stimulation of Isc by ATP in Cl−-free solution was suppressed by 70% (P < 0.01, n = 6) (Figure 5A, B).

Figure 5.

Effects of Cl− depletion on ATP-evoked mucosal HCO3− secretion and Isc, as a measure of Cl− secretion. Gluconate was substituted for Cl− in the bathing medium on both sides of the preparations. (A) ATP-evoked increases in secretion of HCO3− were suppressed by 55% in Cl− depleted medium. (B) ATP-evoked increases in Isc were suppressed by 70% in Cl− depleted medium. Values are expressed as means ± SEM; n = 6 animals for each series of four preparations. ***P < 0.001.

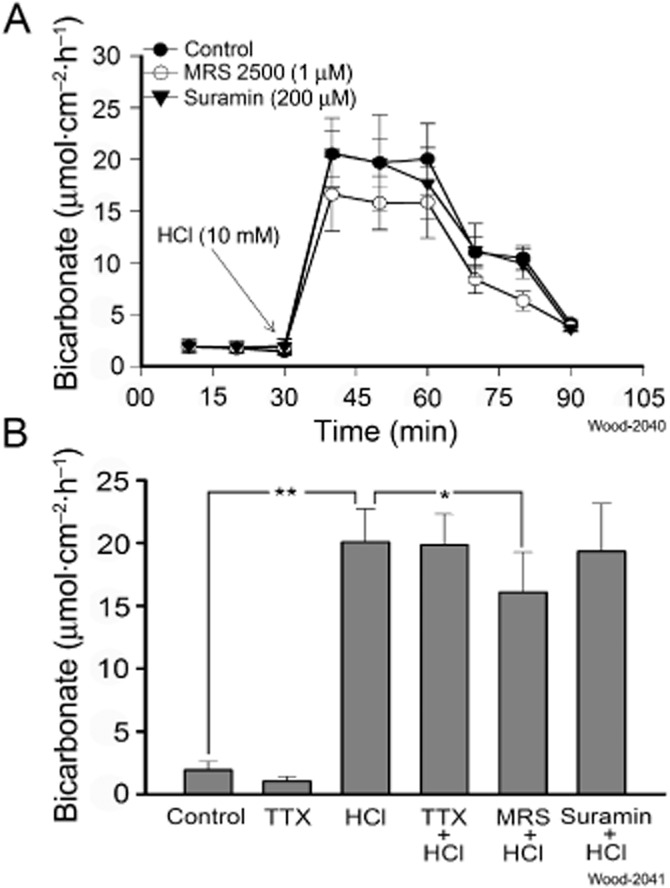

Effects of acid

Exposure to 10 mM HCl, applied to the mucosal sides of the preparations, evoked major increases in HCO3− secretion that exceeded ATP- or ADP-evoked HCO3− secretion by roughly four orders of magnitude (Figure 6A). MRS2500 (1 μM), a potent and selective P2Y1 receptor antagonist (Gil et al., 2010), was placed in the bathing solution in the mucosal compartment of the Ussing chambers 20 min before applying 10 mM HCl. The presence of MRS2500 suppressed HCl-evoked HCO3− secretion by 20% (HCl: 20.08 ± 2.64 vs. MRS25005 + HCl: 16.08 ± 3.19 μmol·cm−2·h−1, P < 0.001, n = 6) (Figure 6A, B). Suramin (200 μM), a broad spectrum P2Y receptor antagonist (Abbracchio et al., 2006), had no effect on HCl-evoked HCO3− secretion (Figure 6A, B). Blockade of intramural neurons by 1 μM TTX did not change HCO3− secretory responses evoked by mucosal application of HCl (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Effects of direct mucosal application of acid on bicarbonate secretion in guinea pig duodenum. Hydrochloric acid (1 M) in a volume of 10 μL was introduced into the 10 mL volume of the mucosal compartment of the Ussing chamber to obtain a final exposure of 10 mM HCl. The pH of the Krebs solution in the compartment was changed from pH 7.4 to pH 4.4 and the working pH of the pH-stat system was set at pH 4.4 for measurement of HCO3− secretion in response to application of HCl. (A) Exposure of the mucosa to 10 mM HCl stimulated secretion of HCO3− in a time-dependent manner. Secretory responses to 10 mM HCl were suppressed by 19.9±% when 1 μM MRS 2500, a selective P2Y1 receptor antagonist, was present in the bathing solution. Secretory responses to 10 mM HCl were unaffected by the presence of 200 μM suramin in the bathing medium. (B) Pharmacological analysis of acid-evoked HCO3− secretion. Suppression of basal secretion (control) by 0.5 μM TTX was a reflection of blockade of spontaneous firing of secretomotor neurons. Neuronal block of intramural neurons by TTX did not alter HCO3− secretory responses to HCl. MRS 2500 (1 μM), but not 200 μM suramin, suppressed HCl-evoked secretory responses.

Discussion

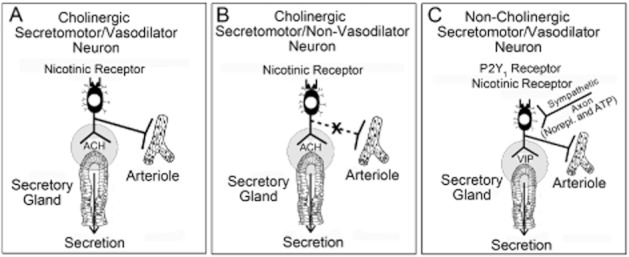

Earlier work of others on duodenal HCO3− secretion was focused on mucosal cytoprotection and roles for purinergic receptor subtypes, which are expressed by enterocytes, in stimulation of HCO3− secretion. Dong et al. (2009) identified the P2Y2 receptor subtype as a major player in acid-evoked epithelial HCO3− secretion. Our work differed in being focused on neurogenic HCO3− secretion. Our results suggest that HCO3− secretion, like Cl− secretion, is under enteric secretomotor neural control (Figure 7). Secretomotor neurons, which evoke Cl− secretion, express excitatory P2Y1 purinergic receptors that are activated by the presynaptic release of ATP from neuronal projections coming from the myenteric plexus, from neighbouring neurons in the submucosal plexus and from sympathetic postganglionic neurons (Hu et al., 2003; Fang et al., 2006). Suppression of ATP-evoked HCO3− secretion during enteric neural blockade with TTX, in the present study, is solid evidence that a component of HCO3− secretion is neurogenic and reminiscent of the neural control for Cl− secretion.

Figure 7.

Three kinds of secretomotor neurons in the submucosal plexus of the enteric nervous system innervate the intestinal secretory glands. (A) Cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons express the immunohistochemical code for the protein, calretinin, and innervate both secretory glands and periglandular arterioles. (B) Cholinergic secretomotor/non-vasodilator neurons express the immunohistochemical code, NPY, and innervate the secretory glands, but not periglandular arterioles. (C) Non-cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons innervate both the secretory glands and periglandular arterioles. These neurons contain VIP in all species. They are the only secretomotor neurons that receive both noradrenergic and purinergic input from sympathetic postganglionic neurons. Non-cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons are responsible for stimulation of bicarbonate secretion. They express P2Y1 purinergic receptors, are stimulated to firing threshold by ATP, and release VIP at their junctions with the secretory epithelium.

The secretomotor neurons that innervate the HCO3− secretory glands express the P2Y1 receptor subtype as evident, in the present study, by suppression of the stimulatory action of ATP by the selective antagonist MRS2179. The evidence suggests that the expression of P2Y1 excitatory neuronal receptors is restricted mainly, if not entirely, to the non-cholinergic/vasodilator secretomotor neurons that release VIP at their junctions with the HCO3− secretory glands. Our finding that a VIP type 1 (VPAC1) receptor antagonist suppressed the stimulatory action of ATP on HCO3− secretion supports a conclusion that non-cholinergic/vasodilator secretomotor neurons are the final common motor output path from the ENS integrative microcircuits to the HCO3− secretory glands. Failure of muscarinic receptor blockade to suppress the ATP-evoked HCO3− secretion practically eliminates the other two of the three types of secretomotor neurons in Figure 7 (i.e. calretinin-containing cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons and neuropeptide Y (NPY)-containing cholinergic secretomotor neurons that do not innervate arterioles) in neurogenic control of HCO3− secretion in the duodenum (Furness, 2006; Wood, 2011; Bornstein et al., 2012).

ADP

ADP, one of the major metabolites of ATP, is a P2Y1 receptor agonist, which has greater potency than ATP in evoking firing of submucosal neurons (Hu et al., 2003). Secretomotor neurons do not express P2Y2 receptors and application of the P2Y2 agonist, UTP does not elicit firing in the neurons (Hu et al., 2003). Dong et al. (2009) reported that ADP did not evoke duodenal HCO3− secretion and that UTP did stimulate duodenal HCO3− secretion. Our finding differed from that of Dong et al. (2009) in that ADP-evoked HCO3− and Cl− secretory responses mimicked those for ATP. This raised the possibility that the ATP-evoked HCO3− secretion, which we observed, might be partly or fully evoked by ADP action on secretomotor neurons, because ATP in the extracellular milieu is known to be hydrolysed rapidly to ADP by membrane bound ecto-ATPases.

We used an ecto-ATPase inhibitor, ARL67156, to examine the possibility that the action of ATP might in fact be mediated by ADP, which accumulated during hydrolysis of ATP. Failure of ecto-ATPase inhibition to suppress ATP-evoked HCO3− secretion indicates that ADP was not a participant in the observed ATP-evoked HCO3− secretory responses. On the other hand, ATP-evoked Cl− secretion, in adjacent chambers, was enhanced significantly when ATP hydrolysis was prevented by ecto-ATPase inhibition.

In view of the work of Levesque et al. (2007) which found only weak inhibition of some ectonucleotidases when concentrations of ATP were high, ARL67156 cannot be assumed to be a global inhibitor of ectonucleotidases. Nevertheless, our findings show with reasonable confidence that ARL67156 effectively inhibits ATP hydrolysis in our preparations. A reflection of ATPase inhibition was a major stimulation of ATP-evoked Isc, which reflects accumulation of ATP and suppression of adenosine formation much as reported for a number of tissues or organs and reviewed by Levesque et al. (2007). According to Levesque et al., the concentrations of ATP used in our study would be expected to prolong the action of ATP at the P2 receptors, even if NTPDase1, NTPDase3 or NPP1 should turn out to be predominant ectonucleotidases in the guinea pig duodenum. This is what we found for neurogenic Isc, but not neurogenic HCO3− secretion. A logical interpretation, supported by the data, is that ADP formation by ectonucleotidases contributes to stimulation of secretomotor P2Y1 receptors in the control circuits for Cl− secretion. On the other hand, failure of inhibition of ectonucleotidases to enhance ATP-evoked HCO3− secretory responses is evidence that ADP formation in the functioning duodenum is probably not involved in stimulation of the secretomotor neurons that innervate the duodenal HCO3− secretory glands.

Effects attributed to ATP can, in fact, often reflect its hydrolysis to adenosine by ectonucleotidases. Ongoing accumulation of adenosine, due to ATPase activity, exerts tonic inhibition of nicotinic synaptic transmission in the ENS, and this is associated with tonic inhibition of neurogenic Cl− secretion in guinea pig intestinal preparations (Christofi and Wood, 1993; Cooke et al., 1999; Fang et al., 2006). Inhibition of ectonucleotidases or removal of newly formed adenosine by treatment with adenosine deaminase enhances nicotinic neurotransmission and elevates neurogenic Cl− secretion (Christofi and Wood, 1993; Cooke et al., 1999; Fang et al., 2006). Application of ARL67156 alone as a part of the present project increased basal Isc, which was evidence that it was behaving as expected in the guinea pig preparations.

Non-cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons

Secretomotor neurons are excitatory ENS motor neurons that represent the final common pathway out of the ENS control circuitry to the secretory glands. Secretomotor neurons evoke secretion by releasing acetylcholine and/or VIP at their junctions with the mucosal epithelium. There are three types of secretomotor neurons: (i) VIP-containing non-cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons; (ii) calretinin-containing cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons; and (iii) neuropeptide (NPY)-containing cholinergic secretomotor neurons that do not innervate periglandular arterioles (Figure 7). We found in earlier electrophysiological studies that P2Y1 receptors mediate excitatory actions of ATP on secretomotor neurons (Hu et al., 2003) and that stimulation of Isc by ATP is suppressed by the P2Y1 receptor antagonist, MRS2179, in guinea pigs (Fang et al., 2006).

Our finding that stimulation of HCO3− secretion by ATP is suppressed by both a P2Y1 receptor antagonist and a VIP receptor antagonist, but not by a cholinergic receptor antagonist, suggests that neurogenic HCO3− secretion results mostly, if not entirely, from activation of P2Y1 purinergic receptors expressed by non-cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons (see Figure 7C). This has functional implications for the role of the sympathetic nervous system in suppressing intestinal secretion.

Sympathetic nervous transmission to the gastrointestinal tract is elevated during physical exercise and environmental and/or psychogenic stress. As much as 25% of the cardiac output can be perfusing the splanchnic circulation at a particular moment. Increased sympathetic activity shunts this blood from the splanchnic to the systemic circulation. Shunting blood flow from the splanchnic circulation occurs in parallel with suppression of digestive functions including motility and secretion.

ATP is stored in synaptic vesicles in sympathetic postganglionic axons. It can be released experimentally by electrical stimulation in guinea pig submucosal plexus where it evokes slow EPSPs, mediated by P2Y1 receptors, in non-cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons (Hu et al., 2003). ATP is stored with norepinephrine in the synaptic vesicles of sympathetic postganglionic neurons in a variety of tissues and organs (Burnstock, 1990; 1995; 2004). Electrical stimulation of the sympathetic nerves in guinea pig submucosal plexus evokes simultaneous slow EPSPs and slow IPSPs that are mediated by alpha2 noradrenergic receptors (Surprenant and North, 1988; Hu et al., 2003). MRS2179 enhances the amplitude of the IPSPs and exposure to alpha2 noradrenergic receptor antagonists enhances the amplitude of the slow EPSPs. Significance of this excitatory–inhibitory ‘push-pull’ effect at synapses on secretomotor neurons, in relation to integrated neural control of mucosal secretion at the whole organ level, is not clear.

Non-cholinergic/vasodilator neurons represent the only kind of secretomotor neuron that is innervated by inhibitory sympathetic noradrenergic neurons (Bornstein and Furness, 1988; Bornstein et al., 1988; Hu et al., 2003; Furness, 2006) (Figure 7C). This implies that ‘shut-down’ of HCO3− secretion, during sympathetic shunting of blood from the splanchnic circulation, is mediated exclusively by sympathetic inhibition of non-cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons. The generalized significance of selective sympathetic targeting of VIP-mediated HCO3− secretion, while excluding cholinergic secretomotor neurons in Cl− secretory pathways, is unclear. Nevertheless, it might relate to mucosal cytoprotection in sympathetically induced ischaemic conditions.

Cholinergic secretomotor and cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons express excitatory receptors including nicotinic receptors, but not the purinergic P2Y1 receptor (Figure 7). Inhibition of nicotinic neurotransmission by well known presynaptic inhibitory action of sympathetically released norepinephrine at these synapses might account for additional suppression of Cl− secretion during sympathetic suppression of splanchnic blood flow (Surprenant and North, 1988).

Non-cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons, in addition to involvement in sympathetic nervous influence in the gut, might also be associated with stress influences on the intestinal tract (reviewed by Wood, 2012). The stress-related neuropeptide, corticotrophin-releasing factor (CRF), is expressed exclusively by these neurons (Liu et al., 2006). They do not express receptors for CRF (Liu et al., 2005). Rather, the receptors for CRF are expressed by neighbouring neurons and enteric mast cells.

Co-expression of CRF with VIP in the non-cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons suggests that CRF is released together with VIP when secretomotor neurons fire and might be integrated with neurogenic HCO3− secretion. That stress increases intestinal Cl− secretion and mucosal permeability to macromolecules, as well as suppression of gastric acid secretion, is clearly documented (Cannon, 1953; Saunders et al., 2002a,b). Furthermore, central administration of CRF stimulates gastric and duodenal HCO3− secretion via the autonomic nervous system and implicates CRF and secretomotor neuronal involvement in mucosal protection (Flemström and Jedstedt, 1989; Gunion et al., 1990).

Chloride/bicarbonate exchange

Multiple mechanisms explain movement of HCO3− across apical membranes of enterocytes, including Cl−/HCO3− exchange, CFTR channels with HCO3- conductance, CFTR coupled to Cl−/HCO3− exchange, and a non-CFTR HCO3− channel (Hogan et al., 1997; Clarke and Harline, 1998; Vidyasagar et al., 2004). We found that ATP-evoked HCO3− secretion was suppressed when Cl− in the bathing medium was depleted, which suggests that ATP-evoked neurogenic HCO3− secretory responses might be partly dependent on apical Cl−/HCO3− exchange. Involvement of other kinds of Cl− channels in the neurogenic HCO3− secretory response to ATP remains to be clarified.

Secretory dynamics

Stimulation of HCO3− by ATP occurred with a significant time lag relative to ATP-evoked Cl− secretion in our study. Time lags of this nature were reported to occur also for stimulation of HCO3− secretion by cyclic nucleotides (Minhas et al., 1993) and 5-hydroxytryptamine (Tuo and Isenberg, 2003). Multiple factors probably underlie the prolonged time course for HCO3− secretion relative to that for Cl−. These might include differences in HCO3− and Cl− channel dynamics and the fact that a change in ionic movement is immediately reflected in Isc while titration of elevated HCO3− is delayed owing to slow diffusion through mucus and other unstirred layers, and by buffer effects in the bulk solution (Tuo and Isenberg, 2003).

Effects of acid

An abbreviated study of properties of acid-induced HCO3− secretion was done to obtain reference data against which neurogenic HCO3− secretion could be evaluated. Our results for exposure to HCl are reminiscent of a review by Flemström (1987), which describes 50–300% increases in HCO3− secretion in response to mucosal exposure to 10 mM HCl for preparations from humans, cats and dogs. On the other hand, neurogenic HCO3− secretion, evoked by electrical stimulation of vagal efferents, produces smaller responses similar to those we have found for stimulation of enteric secretomotor neurons (Granstam et al., 1987; Nylander et al., 1987).

Mucosal HCO3− secretory responses, evoked by direct exposure to acid, appear not to be neurogenic as suggested by our finding that they are unchanged by blockade of intramural neurons. In view of roles for epithelial release of ATP and purinergic P2Y receptor subtypes in mucosal defence against acid injury in the duodenum as reviewed by Ham et al. (2012), Seidler and Sjöblom (2012), Kaunitz and Akiba (2011), and Takeuchi et al. (2011), we explored the action of MRS 2500, a potent and selective P2Y1 receptor antagonist, and suramin, a broad spectrum P2Y receptor antagonist, on acid-evoked HCO3− secretory responses. We found 20% suppression of the acid-evoked HCO3− secretion by MRS 2500, which suggests that this purinergic receptor subtype might have a role in non-neurogenic responses to acid exposure in guinea pigs. Nevertheless, failure of 200 μM suramin to suppress acid-evoked secretion might suggest lesser involvement of purinergic receptors. However, the P2Y2 receptor subtype was reported to have significant involvement in acid-evoked stimulation of HCO3− secretion in mice (Dong et al., 2009).

Conclusion

ATP stimulates duodenal HCO3− secretion mostly through an excitatory action at purinergic P2Y1 receptors expressed by VIPergic non-cholinergic secretomotor/vasodilator neurons in the submucosal division of the ENS. Whereas the ENS continuously ‘fine tunes’ luminal pH and osmolarity, the mucosal epithelium responds to a potentially injurious acid challenge with large protective HCO3− secretory volumes.

Acknowledgments

The National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (Grants RO1 DK 68258 and RO1 DK 37238 to J. D. W. and Grant KO8 DK60468 to Y. X.) and a Pharmaceutical Manufacturers of America Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship to S. L. supported this work.

Glossary

- ENS

enteric nervous system

- Isc

electrogenic short-circuit current

- PD

transmural potential difference

- TTX

tetrodotoxin

- VIP

vasoactive intestinal peptide

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Abbracchio MP, Burnstock G, Boeynaems JM, Barnard EA, Boyer JL, Kennedy C, et al. International Union of Pharmacology LVIII: update on the P2Y G protein-coupled nucleotide receptors: from molecular mechanisms and pathophysiology to therapy. Pharmacol Rev. 2006;58:281–341. doi: 10.1124/pr.58.3.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein JC, Furness JB. Correlated electrophysiological and histochemical studies of submucous neurons and their contribution to understanding enteric neural circuits. J Auton Nerv Syst. 1988;25:1–13. doi: 10.1016/0165-1838(88)90002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein JC, Costa M, Furness JB. Intrinsic and extrinsic inhibitory synaptic inputs to submucous neurones of the guinea-pig small intestine. J Physiol. 1988;398:371–390. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1988.sp017048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein JC, Gwynne RM, Sjovall H. Enteric neural regulation of mucosal secretion. In: Johnson LR, Ghishan FK, Kaunitz JD, Merchant JL, Said HM, Wood JD, editors. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Track. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2012. pp. 769–790. [Google Scholar]

- Boyer JL, Mohanram A, Camaioni E, Jacobson KA, Harden TK. Competitive and selective antagonism of P2Y1 receptors by N6-methyl 2′-deoxyadenosine 3′,5′-bisphosphate. Br J Pharmacol. 1998;124:1–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0701837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Noradrenaline and ATP as cotransmitters in sympathetic nerves. Neurochem Int. 1990;17:357–368. doi: 10.1016/0197-0186(90)90158-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Noradrenaline and ATP: cotransmitters and neuromodulators. J Physiol Pharmacol. 1995;46:365–384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Cotransmission. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004;4:47–52. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147(Suppl. 1):S172–S181. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Physiology and pathophysiology of purinergic neurotransmission. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:659–797. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. The journey to establish purinergic signalling in the gut. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;20(Suppl. 1):8–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2008.01107.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon WB. Bodily Changes in Pain, Hunger, Fear and Rage. Boston, MA: Charles T. Bradford Company; 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Christofi FL, Wood JD. Presynaptic inhibition by adenosine A1 receptors on guinea pig small intestinal myenteric neurons. Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1420–1429. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90351-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christofi FL, Zhang H, Yu JG, Guzman J, Xue J, Kim M, et al. Differential gene expression of adenosine A1, A2a, A2b, and A3 receptors in the human enteric nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2001;439:46–64. doi: 10.1002/cne.1334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke LL, Harline MC. Dual role of CFTR in cAMP-stimulated HCO3- secretion across murine duodenum. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:G718–G726. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1998.274.4.G718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke HJ, Shonnard K, Highison G, Wood JD. Effects of neurotransmitter release on mucosal transport in guinea pig ileum. Am J Physiol. 1983a;245:G745–G750. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1983.245.6.G745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke HJ, Shonnard K, Wood JD. Effects of neuronal stimulation on mucosal transport in guinea pig ileum. Am J Physiol. 1983b;245:G290–G296. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1983.245.2.G290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke HJ, Wang Y, Liu CY, Zhang H, Christofi FL. Activation of neuronal adenosine A1 receptors suppresses secretory reflexes in the guinea pig colon. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:G451–G462. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1999.276.2.G451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke HJ, Xue J, Yu JG, Wunderlich J, Wang YZ, Guzman J, et al. Mechanical stimulation releases nucleotides that activate P2Y1 receptors to trigger neural reflex chloride secretion in guinea pig distal colon. J Comp Neurol. 2004;469:1–15. doi: 10.1002/cne.10960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Smoll EJ, Ko KH, Lee J, Chow JY, Kim HD, et al. P2Y receptors mediate Ca2+ signaling in duodenocytes and contribute to duodenal mucosal bicarbonate secretion. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G424–G432. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90314.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang X, Hu HZ, Gao N, Liu S, Wang GD, Wang XY, et al. Neurogenic secretion mediated by the purinergic P2Y1 receptor in guinea-pig small intestine. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;536:113–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2006.02.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fei G, Fang X, Wang XY, Wang GD, Liu S, Gao N, et al. Neurogenic mucosal bicarbonate secretion mediated by the purinergic P2Y1 receptor in guinea-pig duodenum. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:A380. [Google Scholar]

- Fei G, Raehal K, Liu S, Qu MH, Sun X, Wang GD, et al. Lubiprostone reverses the inhibitory action of morphine on intestinal secretion in guinea pig and mouse. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334:333–340. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.166116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemström G. Gastric and duodenal mucosal bicarbonate secretion. In: Johnson LR, Christensen J, Jackson MJ, Jacobson ED, Walsh JH, editors. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. 2nd edn. New York: Raven Press; 1987. pp. 1011–1029. [Google Scholar]

- Flemström G, Jedstedt G. Stimulation of duodenal mucosal bicarbonate secretion in the rat by brain peptides. Gastroenterology. 1989;97:412–420. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(89)90077-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness JB. The Enteric Nervous System. Oxford: Blackwell; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Gao N, Hu HZ, Zhu MX, Fang X, Liu S, Gao C, et al. The P2Y purinergic receptor expressed by enteric neurones in guinea-pig intestine. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2006;18:316–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2005.00754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil V, Gallego D, Grasa L, Martin MT, Jimenez M. Purinergic and nitrergic neuromuscular transmission mediates spontaneous neuronal activity in the rat colon. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2010;299:G158–G169. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00448.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourine AV, Wood JD, Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling in autonomic control. Trends Neurosci. 2009;32:241–248. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gourlet P, De Neef P, Cnudde J, Waelbroeck M, Robberecht P. In vitro properties of a high affinity selective antagonist of the VIP1 receptor. Peptides. 1997;18:1555–1560. doi: 10.1016/s0196-9781(97)00230-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granstam SO, Flemström G, Nylander O. Bicarbonate secretion by the rabbit duodenum in vivo: effects of prostaglandins, vagal stimulation and some drugs. Acta Physiol Scand. 1987;131:377–385. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1987.tb08253.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunion MW, Kauffman GL, Jr, Tache Y. Intrahypothalamic corticotropin-releasing factor elevates gastric bicarbonate and inhibits stress ulcers in rats. Am J Physiol. 1990;258:G152–G157. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.258.1.G152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham M, Akiba Y, Takeuchi K, Montrose MH, Kaunitz JD. Gastroduodenal mucosal defense. In: Johnson LR, Ghishan FK, Kaunitz JD, Merchant JL, Said HM, Wood JD, editors. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Track. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2012. pp. 1169–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DL, Crombie DL, Isenberg JI, Svendsen P, Schaffalitzky de Muckadell OB, et al. CFTR mediates cAMP- and Ca2+-activated duodenal epithelial HCO3- secretion. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:G872–G878. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1997.272.4.G872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu HZ, Gao N, Zhu MX, Liu S, Ren J, Gao C, et al. Slow excitatory synaptic transmission mediated by P2Y1 receptors in the guinea-pig enteric nervous system. J Physiol. 2003;550:493–504. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.041731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hubel KA. The effects of electrical field stimulation and tetrodotoxin on ion transport by the isolated rabbit ileum. J Clin Invest. 1978;62:1039–1047. doi: 10.1172/JCI109208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaunitz JD, Akiba Y. Purinergic regulation of duodenal surface pH and ATP concentration: implications for mucosal defence, lipid uptake and cystic fibrosis. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2011;201:109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2010.02156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilkenny C, Browne W, Cuthill IC, Emerson M, Altman DG. NC3Rs Reporting Guidelines Working Group. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1577–1579. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00872.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levesque SA, Lavoie EG, Lecka J, Bigonnesse F, Sevigny J. Specificity of the ecto-ATPase inhibitor ARL 67156 on human and mouse ectonucleotidases. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:141–150. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Gao X, Gao N, Wang X, Fang X, Hu HZ, et al. Expression of type 1 corticotropin-releasing factor receptor in the guinea pig enteric nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2005;481:284–298. doi: 10.1002/cne.20370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Gao N, Hu HZ, Wang X, Wang GD, Fang X, et al. Distribution and chemical coding of corticotropin-releasing factor-immunoreactive neurons in the guinea pig enteric nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 2006;494:63–74. doi: 10.1002/cne.20781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGrath J, Drummond G, McLachlan E, Kilkenny C, Wainwright C. Guidelines for reporting experiments involving animals: the ARRIVE guidelines. Br J Pharmacol. 2010;160:1573–1576. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.00873.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minhas BS, Sullivan SK, Field M. Bicarbonate secretion in rabbit ileum: electrogenicity, ion dependence, and effects of cyclic nucleotides. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1617–1629. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)91056-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nylander O, Flemström G, Delbro D, Fandriks L. Vagal influence on gastroduodenal HCO3- secretion in the cat in vivo. Am J Physiol. 1987;252:G522–G528. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1987.252.4.G522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders PR, Maillot C, Million M, Tache Y. Peripheral corticotropin-releasing factor induces diarrhea in rats: role of CRF1 receptor in fecal watery excretion. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002a;435:231–235. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01574-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders PR, Santos J, Hanssen NP, Yates D, Groot JA, Perdue MH. Physical and psychological stress in rats enhances colonic epithelial permeability via peripheral CRH. Dig Dis Sci. 2002b;47:208–215. doi: 10.1023/a:1013204612762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidler U, Sjöblom M. Gastroduodenal bicarbonate secretion. In: Johnson LR, Ghishan FK, Kaunitz JD, Merchant JL, Said HM, Wood JD, editors. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Track. San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press; 2012. pp. 1311–1339. [Google Scholar]

- Surprenant A, North RA. Mechanism of synaptic inhibition by noradrenaline acting at alpha 2-adrenoceptors. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1988;234:85–114. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1988.0039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi K, Kita K, Hayashi S, Aihara E. Regulatory mechanism of duodenal bicarbonate secretion: roles of endogenous prostaglandins and nitric oxide. Pharmacol Ther. 2011;130:59–70. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuo BG, Isenberg JI. Effect of 5-hydroxytryptamine on duodenal mucosal bicarbonate secretion in mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:805–814. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vidyasagar S, Rajendran VM, Binder HJ. Three distinct mechanisms of HCO3- secretion in rat distal colon. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2004;287:C612–C621. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00474.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner N. Cybernetics, Control and Communication in the Animal and the Machine. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Wood JD. Enteric nervous system: sensory physiology, diarrhea and constipation. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2010;26:102–108. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e328334df4f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JD. Enteric Nervous System: The Brain-in-the-Gut. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Wood JD. Enteric neurobiology of stress. In: Johnson LR, Kaunitz JD, Ghishan FK, Merchant JL, Said HM, Wood JD, editors. Physiology of the Gastrointestinal Tract. 5th edn. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2012. pp. 2001–2018. [Google Scholar]

- Worthington V, Zacka J. A comprehensive manual on enzymes and related biochemicals. Am Biotechnol Lab. 1994;12:1–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]