Abstract

The present text exposes a theory of the role of disturbances in the assemblage and evolution of species within ecosystems, based principally, but not exclusively, on terrestrial ecosystems. Two groups of organisms, doted of contrasted strategies when faced with environmental disturbances, are presented, based on the classical r-K dichotomy, but enriched with more modern concepts from community and evolutionary ecology. Both groups participate in the assembly of known animal, plant, and microbial communities, but with different requirements about environmental fluctuations. The so-called “civilized” organisms are doted with efficient anticipatory mechanisms, allowing them to optimize from an energetic point of view their performances in a predictable environment (stable or fluctuating cyclically at the scale of life expectancy), and they developed advanced specializations in the course of evolutionary time. On the opposite side, the so-called “barbarians” are weakly efficient in a stable environment because they waste energy for foraging, growth, and reproduction, but they are well adapted to unpredictably changing conditions, in particular during major ecological crises. Both groups of organisms succeed or alternate each other in the course of spontaneous or geared successional processes, as well as in the course of evolution. The balance of “barbarians” against “civilized” strategies within communities is predicted to shift in favor of the first type under present-day anthropic pressure, exemplified among others by climate warming, land use change, pollution, and biological invasions.

Keywords: Anticipation, disturbances, ecosystems, evolution, global change, species

Introduction

Many studies showed that some species traits were better adapted than others to land use change, pollution, climate warming, or biological invasions (Fisker et al. 2011; Makkonen et al. 2011; Malmström 2012; Shine 2012). Such knowledge could be used to predict which species will survive, become extinct or will have to adapt during the present-day mass extinction (May 2010). Much research effort needs to be conducted in order to have a clear view of the future of plant, animal, and microbial communities face to increasing anthropic pressure (Berg et al. 2010). However, some testable predictions can be made, which is the scope of the present review, based on previous theoretical work already carried out by McArthur and Wilson (1963), Odum (1969) and Pianka (1970), enriched by more modern concepts and adapted to present-day threats to biodiversity in the context of global change. In a first step, anticipation will be considered as a key advantage or disadvantage according to predictability or unpredictability of the environment, respectively. In a second step, species traits, which contribute, or not, to anticipate disturbances will be examined in the light of evolutionary processes. At last, strategies by which organisms and communities can resist, or not, environmental hazards, will be discussed in the frame of global change.

In the present paper, “species” or “traits” are considered indifferently under the generic term of “organisms.” Clearly, traits and species do not evolve at the same rate (Janecka et al. 2012), are not selected or filtered in the same manner (Keddy 1992), and trait representation changes in the course of individual development (Coleman et al. 1994) and within metapopulations and species distribution ranges (Sun and Cheptou 2012).

Anticipation: a key property of organisms and ecosystems in stable environments

Anticipation is the manner in which an organism or a community behaves in advance of a predictable event, whether favorable or unfavorable. Such a mechanism is advantageous, in terms of energetic cost and resource allocation (González-Gómez et al. 2011) in an environment dominated by cyclic processes. Biological clocks (Wang and Wang 2011) participate in this property, as well as all sensory, behavioral, and signaling systems allowing a being or a group of beings to live in harmony with the context (Soler et al. 2011). In this frame, any forwarded event cannot be considered as a disturbance, as the organism or the community reacts in adapted manner. Such adapted reaction norms have been selected and fixed in the genome (Roulin et al. 2011), or are epigenetically induced by the environment (Gorelick 2005). They can also stem from behavioral training, through the memorization of past experiences (González-Gómez et al. 2011), mimicry (Darst 2006), teaching or transmission of knowledge within a familial or social group (Fogarty et al. 2011), or even through clonal reproduction (Trewavas 2005).

Anticipation is progressively established in the course of ontogenesis, more especially when complex locomotory or sensory organs and coordinated nervous and hormonal systems are required (Capellán and Nicieza 2010).

If anticipation is well known in the physiology of organisms (Vitalini et al. 2007), this property has never been cited at the ecosystem or community level, although many processes ensuring the stability of late-successional ecosystems involve anticipation. Bernier and Ponge (1994) showed that the regeneration of mountain coniferous forests is ensured by the recovery of a complete earthworm community under mature trees, following collapse during the pole stage. The reconstitution of the earthworm community occurs well in advance of light arrival, associated with senescence and death of trees, the event previously thought to start regeneration. The complete earthworm community allows spruce recruitment, by creating soil conditions favorable to the establishment of a new generation of spruce (Ponge et al. 1998). Such mechanisms involve feedbacks between soil organisms and plants (Ponge 2013), in particular between the two dominant ecosystem engineers (trees and earthworms). There are serious reasons to believe that such interaction networks, ensuring the long-term stability of habitats, have been selected at the ecosystem level in the course of evolution (Williams and Lenton 2007).

Are all organisms equally efficient in terms of anticipation? The buildup of sensorimotor systems, associated with neuronal and/or chemical mechanisms, is a prerequisite, and needs time. Saving time is possible to a great extent for those organisms taking care of their offspring and/or of members of their group, thereby privileging teaching and mimicry over genetically wired information. Information, in the form of treatment and management of signals, is a key component of anticipation (Patten et al. 1997), but it can work efficiently and durably only in a predictable environment, i.e. in the absence of disturbance.

In the presence of a disturbance (in the restricted sense given to it here, i.e. an unpredictable event), some organisms, less efficient in terms of anticipation, may be favored if they are able to grow, reproduce, and interact with other members of the community in the absence of any refined knowledge of the environment or of the group to which they pertain. Organisms with a short lifespan, able to disperse and reproduce at a high rate, without any need of care and training of juveniles, as well as juveniles of anticipating organisms, will be favored by unpredictable events (Odum 1969; Pianka 1970). Generalists, too, i.e. organisms not specialized on a given environment or a given resource, are also favored by disturbances, when compared with specialists (Devictor et al. 2010; Poisot et al. 2012). At the ecosystem level, pioneer (early-successional) communities are ephemeral, of variable composition, and generally are replaced by more durable communities when and if the environment remains or becomes stable (Isermann 2011).

Stability of the environment may itself result from the development of communities, as in the case of old-growth forests and coral reefs: these ecosystems generate the conditions of their own stability, according to dynamic equilibria (Connell 1978). Ecosystem engineers (trees, earthworms, corals, among many others) play a decisive role in such dynamic equilibria (Bythell and Wild 2011). In the presence of a major disturbance falling out of the range of their tolerance range, durable ecosystems are replaced by ephemeral communities with a high capacity of colonization (Dudgeon et al. 2010).

Can we predict the existence of strategies according to the disturbance regime?

Many species traits have been classified on the base of strategies performed by organisms to ensure their success within communities or in the course of evolution (both concepts are tightly related, see Metz et al. 2008). Table 1 sketches most well-known strategies of plant, animal, and microbial organisms, which all refer to some extent to the r-K continuum. Contrary to most of them, which are dual, The CSR triangle devised by Grime (1977) for plants distinguishes three strategies according to growth rate, site fertility, and competitive ability, thus mixing plant traits and environmental features in a common classificatory endeavor (Craine 2005). Similar continuum triangles of life-history strategies have also been proposed for animals (Winemiller 1992; Vila-Gispert et al. 2002). All these strategies consider stability of the environment as the driving force of their selection, as this was clearly explicit in the seminal work of Levins (1962), but rather implicit in most other studies listed in Table 1. By privileging this aspect and by assembling all traits which are related directly or indirectly to the stability of the environment, two categories of traits/organisms can be suggested. They are called “civilized” and “barbarians,” gathering features related to life history, ecological amplitude and evolution covered by previous classifications (Table 1). Traits classified as “civilized” are those, which allow anticipation of short-term variations in the environment (but not ecological crises), while “barbarian” traits allow life in unpredictable environments and survival of ecological crises. Vicarious categories listed in Table 1 are relative to particular aspects of life history, dispersal, and ecological specialization, which share many properties between them.

Table 1.

Main strategies of ‘barbarian” and “civilized” organisms

| Barbarians | Civilized | References | |

|---|---|---|---|

| r-selected: numerous offspring, early reproduction, high mortality rate | K-selected: reduced offspring, late reproduction, weak mortality rate | Pianka 1970; Fierer et al. 2007; | |

| Generalists: able to reproduce in a wide array of environments | Specialists: able to reproduce in a restricted array of environments | Levins 1968; Egas et al. 2004 | |

| Pioneers: colonizing new environments | Climax species: associated to terminal stages of an ecological succession | Odum 1969; Wehenkel et al. 2006; | |

| Colonizers: short generation time, abundant offspring, high metabolic activity, resistant to pollution | Persisters: long generation time, reduced offspring, low metabolic activity, sensitive to pollution | Ettema and Bongers 1993; Li et al. 2005; | |

| Search strategy by random movements: using coordinated, but never targetted movements | Search strategy by directional movements: using coordinated and targetted | Cain 1985; Armsworth and Roughgarden 2005; | |

| Migrants: without any defined territory | Residents: living in a defined territory (maybe changing seasonally or annually: case of migratory birds and butterflies) | Austin 1970; Holt et al. 2011; | |

| Juveniles and neotenic adults | Adults | Stearns 1976; Johansson et al. 2010; | |

| Natural-selected: small-sized organisms, without sexual dimorphism, with high phenotypic plasticity | Sexual-selected: big-sized organisms, with sexual dimorphism, with poor phenotypic plasticity | McLain 1993; Prinzing et al. 2002a | |

| Density-independence | Density-dependence | Nicholson 1933; Bårdsen and Tveraa 2012; | |

| RuderaIs: fast-growing species inhabiting high-fertility, high-disturbance sites | Competitors: fast-growing species inhabiting high-fertility, low-disturbance sites | Stress-tolerators: slow-growing specie inhabiting low-fertility, low-disturbance sites | Grime 1977; Wilson and Lee 2000 |

Such a dichotomy between “barbarians” and “civilized” does not confer any superiority to one or the other category, according to the tenet by de Montaigne (1595) that barbarism and civilization are two facets of the same endeavor of mankind for surviving in the course of past and future history. The term “barbarians” might seem at first sight reminiscent of “Gengis Khan” species, an expression used by Pimm (1991) to designate struggling invaders. Here, the term of “barbarians” is used in a much broader sense, without focusing on potential species interactions and above all without any negative overtone.

Although widely employed in ecology, the term “strategy” implies a dichotomy between more or less exclusive combinations of life-history and behavioral traits, which can be thought at first sight incompatible with the original r-K continuum (Pianka 1970; Jones 1976). Surprisingly, few workers questioned the existence of a continuum, until Flegr (1997) simulated the impact of environmental fluctuations on mixed populations. He showed that simulated ecosystems switched in the course of time toward either one or the other strategy according to stochastic effects of stability or instability of the environment, r- and K-selection being mutually exclusive in the long-term. Similar conclusions were reached by Arditi et al. (2005) at community level.

Phylogenetic trees based on present species are the net result of macroevolutionary speciation and extinction processes (Morrow et al. 2003) and can be reconstructed using parsimonious methods such as cladistics (Hennig 1975). Species not far from the root of a phylogenetic tree share a majority of basal characters (undifferentiated), contrary to species located far from the root. We may consider that basal characters are present (today) in ancient species or species groups having crossed unpredictable ecological crises, i.e. “barbarians,” and derived characters in more recent species or species groups which did not experience such crises, i.e. “civilized.” According to these definitions, most “civilized” traits are prone to extinction, while most “barbarian” traits would survive a long time across lineages, or would reappear in variable environments (Colles et al. 2009). The idea that mass extinction acts under selective rules different from background extinction has been stressed by Jablonski (2008), pointing to the existence of a fruitful area at the interface of ecology and macroevolution, which still needs to be prospected before clear predictions could be made. Paleoecological studies associating species traits with extinction avoidance or sensitivity are scarce, because life history, physiology, and behavior of fossils are unknown, only ecological specialization and endemism being accessible to paleoecologists. It has been shown that most specialized organisms and endemic species or groups, here classified as “civilized” (Table 1), suffered more from mass extinction than poorly specialized, cosmopolitan species, here classified as “barbarian,” in the course of past ecological crises. This was the case, among many others, for foraminifers at the Cretaceous-Tertiary boundary (Keller et al. 2002) and brachiopods during the End-Permian mass extinction (Rodland and Bottjer 2001). Similar examples can be found in present-day temperature-driven extinction scenarios (Schippers et al. 2011).

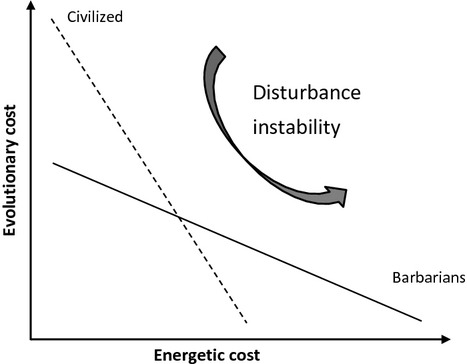

We showed that “barbarians” privilege production by wasting energy for growth and reproduction and “civilized” privilege information by channeling energy on fine tuning. Then a trade-off is possible between two facets of adaptive cost, called “evolutionary cost” (dominant in “civilized”) and “energetic cost” (dominant in “barbarians”). Evolutionary cost is here defined as the number of evolutionary steps (favorable mutations and/or epigenetic events) needed to develop and perform an organizational model in a given environment. Energetic cost is here defined as the amount of energy necessary for survival and reproduction (foraging, avoidance, dispersal, mating, etc.…), which is constrained by food supply and temperature in a given environment. Demonstration of such a trade-off between long-term (evolutionary) and short-term (energetic) costs is difficult to achieve, but a recent study by Bekaert et al. (2012) showed that energetic limitations contributed to fitness costs of glucosinolates, a phylogenetically sensitive class of compounds produced by Brassicales, used here as a proxy of the evolution of herbivory resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana.

Each neuronal and/or hormonal network, needed to reduce the energetic cost of an organism, has an evolutionary cost (Niven and Laughlin 2008). Thereby, long-term stability of the environment is a prerequisite for the evolution of complex functional networks within a community (Vermeij 2012), pointing to (evolutionary) time as a constraint. The complication of organizational templates along lineages is often accompanied by an increase in size, as a result of species interactions (Vermeij 2012). This evolutionary arms race stems in deadlocks, often linked to gigantism and extreme specialization (Myers 1996). Evolutionary stasis is followed by abrupt changes, modifying the “groundplan” to create new lineages starting from “young”, little specialized (dedifferentiated, often neotenic) organisms (Futuyma and Moreno 1988). These newly created lineages are very dynamic from an evolutionary point of view, because of short life cycles and a high ability to colonize new environments (Salzburger et al. 2005). Evolutionary cycles of stability (coordinated stasis) alternating with intense radiation (DiMichele et al. 2004) are similar to successions observed at ecosystem level (Odum 1969). They suppose the existence of a major constraint imposing a correlation between physiology, shape, demography, and dispersal (Reed et al. 2010). Such a correlated response in the evolution of phenotypic plasticity (Scheiner 2002) implies a very limited number of possible (viable) cases, i.e. strategies, which have been detected by simulating virtual communities (Goudard and Loreau 2008). This was experimentally proven to occur in microbial communities (Williams and Lenton 2007).

Figure 1 explains in a scheme how constraints in energy and in time generate the existence of two non-exclusive strategies. Instability of the environment, above a given threshold making it unpredictable to organisms, generates a pressure making the “time” constraint dominant above the “energy” constraint. Only pre-adapted species (Afanasjeva 2010), with a wide tolerance breadth (here called “barbarians”) will subsist, possibly using epigenetic modifications induced by the environment (Angers et al. 2010) in addition to their innate phenotypic plasticity (Reed et al. 2010). On the contrary, when environmental stability recovers for a long period (Marcotte 1999), or when species find stable refuges (Dzik 1999), organisms using their energy for finely tuning with the environment (“civilized”) will take over, replacing “barbarians” (Wilson and Yoshimura 1994).

Figure 1.

Evolutionary and energetic costs favor differently “barbarians” and “civilized” organisms, disturbances and environmental instability increase energy availability and decrease time to adapt.

Although focus has been made above on abiotic environmental conditions, it must be clear that many biotic influences affect traits and/or organisms and their capacity to tolerate disturbances. The example of host–parasite interactions is particularly demonstrative in this respect. The parasite is a specialized organism, which in its way of life is associated with its host by many anticipatory mechanisms, allowing it to maintain viable populations (Tinsley 2004). When the parasite prevents (and thus anticipates) the death of its host by lowering its infectious potential below a threshold of tolerance (Duerr et al. 2004), it clearly belongs to the “civilized” category. More generally, all density-dependent processes, whether negative or positive (including the “Allee effect”), belong to the “civilized” category (Bårdsen and Tveraa 2012). The more an organism will be specialized on a host or a food resource or on conspecifics, the more it will be sensitive to any disturbance affecting the organism(s) on which it depends for its survival and reproduction (Montoya et al. 2009). Density-independent processes escape to such biotic control and thus rather belong to the “barbarian” category, associated with unpredictability (Sinclair and Pech 1996).

“Barbarians” and “civilized” in a changing world: who will win and why?

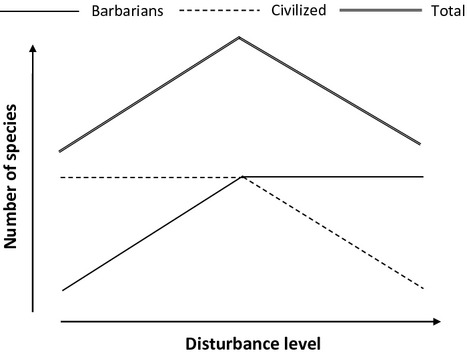

In the presence of environmental instability, “civilized” organisms are at disadvantage compared with “barbarians”, the contrary when conditions become stable again. However, “barbarians” and “civilized” may cohabit within the same community and perform complementary functions (Wilson and Yoshimura 1994) inasmuch as conditions are not those of a major ecological crisis affecting all biotopes present in a given region of the world. Examples of major ecological crises are great glaciations of the Pleistocene, K-T boundary and Permian-Triassic extinctions (Raup 1986). Both categories are just in balance according to the disturbance regime, along a continuum from most to least stable environments (Fig. 2). At an intermediate level of disturbance biodiversity is maximized because it is the ultimate level at which “barbarians” and “civilized” may cohabit within the limits of regional pools (Lessard et al. 2012), immigration waves (Esther et al. 2008) and species interactions (Mason et al. 2008). The fact that intermediate levels of disturbance (Molino and Sabatier 2001) and intermediate stages of succession (Isermann 2011) are favorable to local biodiversity can thus been explained by other hypotheses than resource limitation and competitive exclusion (Connell 1978).

Figure 2.

The “intermediate disturbance hypothesis” explained by the balance between “barbarians” and “civilized” species.

Several aspects of global change have been selected for the following discussion: climate warming, pollution, land use change, biological invasions, and the registered (although still debated) increase in the amplitude and frequency of climatic and geologic catastrophes.

Climate warming, in particular the rapid temperature increase recorded over the last 40–50 years (Thompson et al. 2008), often associated with increased climate instability (Canale and Henry 2010), generates shifts in the distribution of plants and animals over large areas of the world (Thomas 2010). Within the same time lapse, many habitats collapsed (Clarke et al. 2007) or became fragmented (Cormont et al. 2012). Species with a high rate of phenotypic plasticity (Canale et al. 2011) and genetic diversity (Hoffmann and Willi 2008) are favored by climate warming. Species able to disperse and grow rapidly (Makkonen et al. 2011) as well as infectious diseases (Mouritsen et al. 2005) increase, and plant phenology changes in favor of earlier reproduction (Post et al. 2008). All these shifts in species traits point to an advantage given to “barbarian” over “civilized” traits. “Barbarians” are thus thought to increase until a new equilibrium will be reached, which would turn to an advantage given to “civilized” traits, species or phenotypes.

It has been observed that species with a wide geographic range are favored by climate warming (Arribas et al. 2012), as this occurred in the course of past ecological crises (Jablonski 2005). Fonty et al. (2009) showed that all plant life-forms and dispersal modes recorded in a tropical ecotone were affected by local extinctions, in inverse proportion to their rate of presence. Thus, commonness seems to be selected against rarity in the course of extinction events (Reinhardt et al. 2005), another clue to an advantage given to species commonly classified as “generalists” (Remold 2012) and/or with a high dispersal ability (Tedesco et al. 2012) against “specialists” and/or with a low dispersal ability, i.e. on “barbarians” against “civilized”. However, global climate warming is often accompanied by severe drought events which impact dramatically more sensitive environments, such as tropical rainforests (Wright and Calderón 2006), and the more when these forests are disturbed by logging (Curran et al. 1999). In such cases, the stress component (drought) may overwhelm the disturbance component of environmental change (Condit et al. 1995). Selection shifts then in favor of stress-tolerance traits (Read and Stokes 2006), belonging to the “civilized” strategy, rather than of disturbance traits (Jonsson and Esseen 1998), which belong to the “barbarian” strategy.

The effects of pollution and acidification of soil and atmosphere have been studied intensively during the last 40 years. Field studies showed severe disruptions in the composition of communities (Syrek et al. 2006), and irreversible collapses in ecosystem functioning, stemming in organic matter accumulation (Gillet and Ponge 2002). Hågvar (1990) elaborated an elegant hypothesis, highlighting behavioral choice and competition as driving forces of the response of species to soil acidity. But which life-history and dispersal traits are favored by pollution? Sexual reproduction seems to be favored over clonal reproduction in severely polluted conditions (Niklasson et al. 2000), and it has been suspected that some (apparently healthy) communities of polluted areas are maintained by high immigration rates compensating for high mortality (Møller et al. 2012). Both features are typical of unspecialized species privileging phenotypic variety (Poisot et al. 2012), with a high rate of nondirectional random movements to unfavorable places (Auclerc et al. 2010). Comparisons between polluted and nonpolluted areas show that species living in polluted environments are smaller, reproduce earlier and have a shorter lifespan (Prinzing et al. 2002b). All these characters point to many advantages given to “barbarian” over “civilized” traits. However, some studies did not reveal the same trends in aquatic faunas (Postma et al. 1995). This questions pollution as a stress or a press disturbance (Arens and West 2008), for which species can develop special mechanisms for tolerance in a stable environment (Janssens et al. 2009), i.e. of “civilized” type, or as a pulse disturbance, for which species survival must rely on rapid growth, reproduction and active dispersal, i.e. “barbarian” type.

Landuse change and fragmentation are known to favor species displaying a low level of specialization (Barbaro and Van Halder 2009) and/or moving easily through a heterogeneous landscape (Malmström 2012). Both groups of trait attributes belong clearly to the “barbarian” category. Similar shifts in trait representation were observed following the destruction of coral reefs (Feary 2007). However, the case of butterflies deserves a special attention, as some species with a high degree of specialization and efficient directional movements are able to withstand fragmentation, at least up to a certain threshold (Bergerot et al. 2012). These species, which are tolerant of fragmentation despite of their “civilized” characters, are in fact adapted to fragmented habitats in a stable landscape (Schtickzelle et al. 2007). This is also the case of mass migrations through heterogeneous landscapes observed in some collembolan species (Gauer 1997). Such heterogeneous environments can be considered stable at landscape scale (although changing in the course of time at local scale) and thus are predicted to select for “civilized” traits.

Biological invasions are still imperfectly understood from the point of view of threats to biodiversity and community change. In particular, changes in trait distribution of affected communities are poorly documented (Westley 2011). In the plant kingdom, invasive species are characterized by a high production rate (McAlpine et al. 2008), often associated with high phenotypic plasticity and efficient dispersal mechanisms (Thiébaut 2007). Most recorded effects of biological invasions are negative effects, such as habitat loss (Lichstein et al. 2004) and increased nutrient availability (Vitousek et al. 1987). However, high litter input and the ease with which invasive plants exploit soil nutrient resources may also help create new habitats (Maurel et al. 2010). In the animal kingdom, invasive species displace equilibria within communities either by predation or by competing with indigenous species, at least in initial phases of invasion (Morrison 2002), and they benefit from disturbances caused by human activities (Chauvel et al. 1999). They may also change profoundly existing habitats, as in the case of ecosystem engineers such as earthworms (Eisenhauer et al. 2009). In all these cases, indigenous specialists (Almeida-Neto et al. 2010), or species unable to find rapidly safe refuges (Urban and Titus 2010) are at disadvantage, pointing in turn to a selection in favor of “barbarians.” Invasive species themselves can be classified as “barbarians,” given their high investment in growth and reproduction, and more generally their versatility (Prinzing et al. 2002a).

That unprecedented recurrent catastrophes can be attributed to global change, in particular climate warming, is often advocated although still debated (Changnon 2009). If true, this gives strength to several predictions of the Gaia model (Kleidon 2010). Although poorly documented from an adaptive point of view, present-day catastrophic events such as earthquakes, tsunamis or storms destroy habitats to the same extent and with the same rapidity as fires, pollution, deforestation, mining activities, etc. As a consequence, traits associated with catastrophic “natural” disturbances do not differ from those associated with environmental hazards directly caused by human activities: “barbarian” traits (see Table 1) are advantageous, mostly because they do not rely on anticipation for ensuring survival and reproduction of species. Paleontological studies showed that “barbarian” traits were associated with organisms benefiting from mass extinctions which occurred at Permian-Triassic and Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-T) boundaries (Fawcett et al. 2009).

Conclusions

The importance of anticipatory processes occurring in the adaptation of organisms to stable or unstable environments has been stressed. Two categories of traits or of organisms can be identified, called “civilized” and “barbarians,” according to advantage or disadvantage of anticipating disturbing events, respectively. This corresponds to the classical r-K dichotomy (Pianka 1970), here enlarged to several other commonly used classifications, such as “generalists” and “specialists” (see Table 1 for further details). It allows predicting which series of traits are or will be favored by present-day global change and associated disturbances. From a practical point of view, traits can be classified into “barbarians” and “civilized” on the base of properties which define them (absence or presence of anticipatory mechanisms, respectively) or proxies of these properties listed in Table 1. Changes in trait representation are expected to occur first, as a given species can shift rapidly from a strategy to another, as this has been shown to occur in bird species once classified as “specialists” (Barnagaud et al. 2011; see also review by Colles et al. 2009). The place taken by “barbarian” traits within communities, whether due to species replacement or to adaptation (selection or phenotypic plasticity), is thought to increase dramatically, at least until a new equilibrium state, if any, will be reached in a more or less near future (Jump and Peñuelas 2005). This increase does not necessarily cope with a corresponding decrease in “civilized” traits or species except when a threshold of tolerance is attained in the “civilized” category (see Fig. 2). Present-day collapses in global biodiversity (Laurance et al. 2012) seem to indicate that this threshold has been reached (Barnosky et al. 2012).

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- Afanasjeva GA. Large extinctions of articulate brachiopods in the Paleozoic and their ecological and evolutionary consequences. Paleontol. J. 2010;44:1200–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida-Neto M, Prado PI, Kubota U, Bariani JM, Aguirre GH, Lewinsohn TM. Invasive grasses and native Asteraceae in the Brazilian Cerrado. Plant Ecol. 2010;209:109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Angers B, Castonguay E, Massicotte R. Environmentally induced phenotypes and DNA methylation: how to deal with unpredictable conditions until the next generation and after. Mol. Ecol. 2010;19:1283–1295. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2010.04580.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arditi R, Michalski J, Hirzel AH. Rheagogies: modeling non-trophic effects in food webs. Ecol. Complex. 2005;2:249–258. [Google Scholar]

- Arens NC, West ID. Press-pulse: a general theory of mass extinction? Paleobiology. 2008;34:456–471. [Google Scholar]

- Armsworth PR, Roughgarden JE. The impact of directed versus random movements on population dynamics and biodiversity patterns. Am. Nat. 2005;165:449–465. doi: 10.1086/428595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arribas P, Abellán P, Velasco J, Bilton DT, Millán A, Sánchez-Fernández D. Evaluating drivers of vulnerability to climate change: a guide for insect conservation strategies. Glob. Change Biol. 2012;18:2135–2146. [Google Scholar]

- Auclerc A, Libourel PA, Salmon S, Bels V, Ponge JF. Assessment of movement patterns in Folsomia candida (Hexapoda: Collembola) in the presence of food. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010;42:657–659. [Google Scholar]

- Austin GT. Interspecific territoriality of migrant calliope and resident broad-tailed hummingbirds. Condor. 1970;72:234. [Google Scholar]

- Barbaro L, Van Halder I. Linking bird, carabids beetle and butterfly life-history traits to habitat fragmentation in mosaic landscapes. Ecography. 2009;32:321–333. [Google Scholar]

- Bårdsen BJ, Tveraa T. Density-dependence vs. density-independence: linking reproductive allocation to population abundance and vegetation greenness. J. Anim. Ecol. 2012;81:364–376. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2011.01913.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnagaud JY, Devictor V, Jiguet F, Archaux F. When species become generalists: on-going large-scale changes in bird habitat specialization. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2011;20:630–640. [Google Scholar]

- Barnosky AD, Hadly EA, Bascompte J, Berlow AL, Brown JH, Fortlius M, et al. Approaching a state shift in Earth's biosphere. Nature. 2012;486:52–58. doi: 10.1038/nature11018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bekaert M, Edger PP, Hudson CM, Pires JC, Conant GC. Metabolic and evolutionary costs of herbivory defense: systems biology of glucosinolates synthesis. New Phytol. 2012;196:596–605. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2012.04302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg MP, Kiers ET, Driessen G, Kooi M, Van der Heijden BW, Kuenen F, et al. Adapt or disperse: understanding species persistence in a changing world. Glob. Change Biol. 2010;16:587–598. [Google Scholar]

- Bergerot B, Merckx T, Baguette H, Van Dyck M. Habitat fragmentation impacts mobility in a common and widespread woodland butterfly: do sexes respond differently? BMC Ecol. 2012;12:5. doi: 10.1186/1472-6785-12-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernier N, Ponge JF. Humus form dynamics during the sylvogenetic cycle in a mountain spruce forest. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1994;26:183–220. [Google Scholar]

- Bythell JC, Wild C. Biology and ecology of coral mucus release. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2011;408:88–93. [Google Scholar]

- Cain ML. Random search by herbivorous insects: a simulation model. Ecology. 1985;66:876–888. [Google Scholar]

- Canale CI, Henry PY. Adaptive phenotypic plasticity and resilience of vertebrates to increasing climatic unpredictability. Climate Res. 2010;43:135–147. [Google Scholar]

- Canale CI, Perret M, Théry M, Henry PY. Physiological flexibility and acclimation to food shortage in a heterothermic primate. J. Exp. Biol. 2011;214:551–560. doi: 10.1242/jeb.046987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capellán E, Nicieza AG. Constrained plasticity in switching across life stages: pre- and post-switch predators elicit early hatching. Evol. Ecol. 2010;24:49–57. [Google Scholar]

- Changnon SA. Characteristics of severe Atlantic hurricanes in the United States: 1949–2006. J. Hazard. 2009;48:329–337. [Google Scholar]

- Chauvel A, Grimaldi M, Barros E, Blanchart E, Desjardins T, Sarrazin M, et al. Pasture damage by an Amazonian earthworm. Nature. 1999;398:32–33. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke A, Murphy EJ, Meredith MP, King JC, Peck LS, Barnes DKA, et al. Climate change and the marine ecosystem of the western Antarctic Peninsula. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2007;362:149–166. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman JS, McConnaughay KDM, Ackerly DD. Interpreting phenotypic variation in plants. Trends Ecol. Evol. 1994;9:187–191. doi: 10.1016/0169-5347(94)90087-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colles A, Liow LH, Prinzing A. Are specialists at risk under environmental change? Neoecological, paleoecological and phylogenetic approaches. Ecol. Lett. 2009;12:849–863. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01336.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Condit R, Hubbell SP, Foster RB. Mortality rates of 205 neotropical tree and shrub species and the impact of a severe drought. Ecol. Monogr. 1995;65:419–439. [Google Scholar]

- Connell JH. Diversity in tropical rain forests and coral reefs. Science. 1978;199:1302–1310. doi: 10.1126/science.199.4335.1302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cormont A, Jochem R, Malinowska A, Verboom J, WallisDeVries MF, Opdam P. Can phenological shifts compensate for adverse effects of climate change on butterfly metapopulation viability? Ecol. Model. 2012;227:72–81. [Google Scholar]

- Craine JM. Reconciling plant strategy theories of Grime and Tilman. J. Ecol. 2005;93:1041–1052. [Google Scholar]

- Curran LM, Caniago I, Paoli GD, Astianti D, Kusneti M, Leighton M, et al. Impact of El Niño and logging on canopy tree recruitment in Borneo. Science. 1999;286:2184–2188. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5447.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darst CR. Predator learning, experimental psychology and novel predictions for mimicry dynamics. Anim. Behav. 2006;71:743–748. [Google Scholar]

- Devictor V, Clavel J, Julliard R, Lavergne S, Mouillot D, Thuiller W, et al. Defining and measuring ecological specialization. J. Appl. Ecol. 2010;47:15–25. [Google Scholar]

- DiMichele WA, Behrensmeyer AK, Olszewski TD, Labandeira CC, Pandolfi JM, Wing SL, et al. Long-term stasis in ecological assemblages: evidence from the fossil record. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2004;35:285–322. [Google Scholar]

- Dudgeon SR, Aronson RB, Bruno JF, Precht WF. Phase shifts and stable states on coral reefs. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2010;413:201–216. [Google Scholar]

- Duerr HP, Dietz K, Schulz-Key H, Büttner DW, Eichner M. The relationships between the burden of adult parasites, host age and the microfilarial density in human onchocerciasis. Int. J. Parasitol. 2004;34:463–473. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2003.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzik J. Relationship between rates of speciation and phyletic evolution: stratophenetic data on pelagic conodont chordates and benthic ostracods. Geobios. 1999;32:205–221. [Google Scholar]

- Egas M, Dieckmann U, Sabelis MW. Evolution restricts the coexistence of specialists and generalits: the role of trade-off structure. Am. Nat. 2004;163:518–531. doi: 10.1086/382599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenhauer N, Straube D, Johnson EA, Parkinson D, Scheu S. Exotic ecosystem engineers change the emergence of plants from the seed bank of a deciduous forest. Ecosystems. 2009;12:1008–1016. [Google Scholar]

- Esther A, Groeneveld J, Enright NJ, Miller BP, Lamont BB, Perry GLW, et al. Assessing the importance of seed immigration on coexistence of plant functional types in a species-rich ecosystem. Ecol. Model. 2008;213:402–416. [Google Scholar]

- Ettema CH, Bongers T. Characterization of nematode colonization and succession in disturbed soil using the Maturity Index. Biol. Fert. Soils. 1993;16:79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett JA, Maere S, Van de Peer Y. Plants with double genomes might have had a better chance to survive the Cretaceous-Tertiary extinction event. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2009;106:5737–5742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900906106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feary DA. The influence of resource specialization on the response of reef fish to coral disturbance. Mar. Biol. 2007;153:153–161. [Google Scholar]

- Fierer N, Bradford MA, Jackson RB. Toward an ecological classification of soil bacteria. Ecology. 2007;88:1354–1364. doi: 10.1890/05-1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisker KV, Sørensen JG, Damgaard C, Pedersen KL, Holmstrup M. Genetic adaptation of earthworms to copper pollution: is adaptation associated with fitness costs in Dendrobaena octaedra. Ecotoxicology. 2011;20:563–573. doi: 10.1007/s10646-011-0610-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegr J. Two distinct types of natural selection in turbidostat-like and chemostat-like ecosystems. J. Theor. Biol. 1997;188:121–126. [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty L, Strimling P, Laland KN. The evolution of teaching. Evolution. 2011;65:2760–2770. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2011.01370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fonty E, Sarthou C, Larpin D, Ponge JF. A 10-year decrease in plant species richness on a neotropical inselberg: detrimental effects of global warming? Glob. Change Biol. 2009;15:2360–2374. [Google Scholar]

- Futuyma DJ, Moreno G. The evolution of ecological specialization. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1988;19:207–233. [Google Scholar]

- Gauer U. Collembola in Central Amazon inundation forests: strategies for surviving floods. Pedobiologia. 1997;41:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Gillet S, Ponge JF. Humus forms and metal pollution in soil. Eur. J. Soil Sci. 2002;53:529–539. [Google Scholar]

- González-Gómez PL, Bozinovic F, Vasquez RA. Elements of episodic-like memory in free-living hummingbirds, energetic consequences. Anim. Behav. 2011;81:1257–1262. [Google Scholar]

- Gorelick R. Environmentally alterable additive genetic effects. Evol. Ecol. Res. 2005;7:371–379. [Google Scholar]

- Goudard A, Loreau M. Nontrophic interactions, biodiversity, and ecosystem functioning: an interaction web model. Am. Nat. 2008;171:91–106. doi: 10.1086/523945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grime JP. Evidence for the existence of three primary strategies in plants and its relevance to ecological and evolutionary theory. Am. Nat. 1977;111:1169–1194. [Google Scholar]

- Hågvar S. Reactions to soil acidification in microarthropods: is competition a key factor? Biol. Fert. Soils. 1990;9:178–181. [Google Scholar]

- Hennig W. Cladistic analysis or cladistic classification: a reply to Ernst Mayr. Syst. Zool. 1975;24:244–256. [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann AA, Willi Y. Detecting genetic responses to environmental change. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2008;9:421–432. doi: 10.1038/nrg2339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CA, Fuller RJ, Dolman PM. Breeding and post-breeding responses of woodland birds to modification of habitat structure by deer. Biol. Conserv. 2011;144:2151–2162. [Google Scholar]

- Isermann M. Patterns in species diversity during succession of coastal dunes. J. Coastal Res. 2011;27:661–671. [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski D. Mass extinctions and macroevolution. Paleobiology. 2005;31:192–201. [Google Scholar]

- Jablonski D. Extinction and the spatial dynamics of biodiversity. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:11528–11535. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801919105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janecka J, Chowdhary B, Murphy W. Exploring the correlations between sequence evolution rate and phenotypic divergence across the Mammalian tree provides insights into adapative evolution. J. Biosoc. 2012;37:897–909. doi: 10.1007/s12038-012-9254-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens TKS, Roelofs D, Van Straalen NM. Molecular mechanisms of heavy metal tolerance and evolution in invertebrates. Insect Behav. 2009;16:3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson F, Lederer B, Lind MI. Trait performance correlations across life stages under environmental stress conditions in the common grog, Rana temporaria. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e11680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011680. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JM. The r-K-selection continuum. Am. Nat. 1976;110:320–323. [Google Scholar]

- Jonsson BG, Esseen PA. Plant colonization in small forest-floor patches: importance of plant group and disturbance traits. Ecography. 1998;21:518–526. [Google Scholar]

- Jump AS, Peñuelas J. Running to stand still: adaptation and the response of plants to rapid climate change. Ecol. Lett. 2005;8:1010–1020. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00796.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keddy PA. Assembly and response rules: two goals for predictive community ecology. J. Veg. Sci. 1992;3:157–164. [Google Scholar]

- Keller G, Adatte T, Stinnesbeck W, Luciani V, Karoui-Yaakoub N, Zahgib-Turki D. Paleoecology of the Cretaceous-Tertiary mass extinction in planktonic foraminifera. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 2002;178:257–297. [Google Scholar]

- Kleidon A. Life, hierarchy, and the thermodynamic machinery of planet Earth. Phys. Life Rev. 2010;7:424–460. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurance WF, Useche DC, Rendeiro J, Kalka M, Bradshaw CJA, Sloan SP, et al. Averting biodiversity collapse in tropical forest protected areas. Nature. 2012;489:290–294. doi: 10.1038/nature11318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard JP, Borregaard MK, Fordyce JA, Rahbek C, Weiser MD, Dunn RR, et al. String influence of regional species pool on continent-wide structuring of local communities. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lond B Biol. 2012;279:266–274. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2011.0552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levins R. Theory of fitness in a heterogeneous environment. I. The fitness set and its adaptive function. Am. Nat. 1962;96:361–373. [Google Scholar]

- Levins R. Evolution in changing environments. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Li F, Neher DA, Darby BJ, Weicht TR. Observed differences in life history characteristics of nematodes Aphelenchus and Acrobeloides upon exposure to copper and benzo(a)pyrene. Ecotoxicology. 2005;14:419–429. doi: 10.1007/s10646-004-1347-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichstein JW, Grau HR, Aragón R. Recruitment limitation in secondary forests dominated by an exotic tree. J. Veg. Sci. 2004;15:721–728. [Google Scholar]

- Makkonen M, Berg MP, Van Hal JR, Callaghan TV, Press MC, Aerts R. Traits explain the responses of a sub-arctic Collembola community to climate manipulation. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2011;43:377–384. [Google Scholar]

- Malmström A. Life-history traits predict recovery patterns in Collembola species after fire: a 10 year study. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2012;56:35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Marcotte BM. Turbidity, arthropods and the evolution of perception: toward a new paradigm of marine Phanerozoic diversity. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 1999;191:267–288. [Google Scholar]

- Mason NWH, Irz P, Lanoiselée C, Mouillot D, Argillier C. Evidence that niche specialization explains species-energy relationships in lake fish communities. J. Anim. Ecol. 2008;77:285–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2656.2007.01350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurel N, Salmon S, Ponge JF, Machon N, Moret J, Muratet A. Does the invasive species Reynoutria japonica have an impact on soil and flora in urban wastelands? Biol. Invasions. 2010;12:1709–1719. [Google Scholar]

- May RM. Ecological science and tomorrow's world. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2010;365:41–47. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlpine KG, Jesson LK, Kubien DS. Photosynthesis and water-use efficiency: a comparison between invasive (exotic) and non-invasive (native) species. Austral Ecol. 2008;33:10–19. [Google Scholar]

- McArthur RH, Wilson EO. An equilibrium theory of insular zoogeography. Evolution. 1963;17:373–387. [Google Scholar]

- McLain DK. Cope's rules, sexual selection, and the loss of ecological plasticity. Oikos. 1993;68:490–500. [Google Scholar]

- Metz JAJ, Mylius SD, Diekmann O. When does evolution optimize? Evol. Ecol. Res. 2008;10:629–654. [Google Scholar]

- Molino JF, Sabatier D. Tree diversity in tropical rain forests: a validation of the intermediate disturbance hypothesis. Science. 2001;294:1702–1704. doi: 10.1126/science.1060284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Møller AP, Bonisoli-Alquati A, Rudolfsen G, Mousseau TA. Elevated mortality among birds in Chernobyl as judged from skewed age and sex ratios. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35223. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Montaigne ME. Les Essais, Livre I. Abel Langelier, Paris: 1595. [Google Scholar]

- Montoya JM, Woodward G, Emmerson MC, Solé RV. Press perturbations and indirect effects in real food webs. Ecology. 2009;90:2426–2433. doi: 10.1890/08-0657.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison LW. Long-term impacts of an arthropod-community invasion by the imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Ecology. 2002;83:2337–2345. [Google Scholar]

- Morrow EH, Pitcher TE, Arnqvist G. No evidence that sexual selection is an ‘engine of speciation’ in birds. Ecol. Lett. 2003;6:228–234. [Google Scholar]

- Mouritsen KN, Tompkins DM, Poulin R. Climate warming may cause a parasite-induced collapse in coastal amphipod populations. Oecologia. 2005;146:476–483. doi: 10.1007/s00442-005-0223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers N. The biodiversity crisis and the future of evolution. Environmentalist. 1996;16:37–47. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson AJ. The balance of natural populations. J. Anim. Ecol. 1933;2:131–178. [Google Scholar]

- Niklasson M, Petersen H, Parker ED., Jr Environmental stress and reproductive mode in Mesaphorura macrochaeta (Tullbergiinae, Collembola) Pedobiologia. 2000;44:476–488. [Google Scholar]

- Niven JE, Laughlin SB. Energy limitation as a selective pressure on the evolution of sensory systems. J. Exp. Biol. 2008;211:1792–1804. doi: 10.1242/jeb.017574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum EP. The strategy of ecosystem development. Science. 1969;164:262–270. doi: 10.1126/science.164.3877.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patten BC, Straškraba M, Jørgensen SE. Ecosystems emerging. I. Conservation. Ecol. Model. 1997;96:221–284. [Google Scholar]

- Pianka ER. On r- and K-selection. Am. Nat. 1970;104:592–597. [Google Scholar]

- Pimm SL. The Balance of Nature? Ecological Issues in the Conservation of Species and Communities. Chicago: Chicago University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Poisot T, Bever JD, Nemri A, Thrall PH, Hochberg ME. A conceptual framework for the evolution of ecological specialization. Ecol. Lett. 2012;14:841–851. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01645.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponge JF. Plant-soil feedbacks mediated by humus forms: a review. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2013;57:1048–1060. [Google Scholar]

- Ponge JF, André J, Zackrisson O, Bernier N, Nilsson MC, Gallet C. The forest regeneration puzzle. Bioscience. 1998;48:523–530. [Google Scholar]

- Post ES, Pedersen C, Wilmers CC, Forchhammer MC. Phenological sequences reveal aggregate life history response to climatic warming. Ecology. 2008;89:363–370. doi: 10.1890/06-2138.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Postma JF, Admiraal A, Van Kleunen W. Alterations in life-history traits of Chironomus riparius (Diptera) obtained from metal contaminated rivers. Arch. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 1995;29:469–475. [Google Scholar]

- Prinzing A, Brändle M, Pfeifer R, Brandl R. Does sexual selection influence population trends in European birds? Evol. Ecol. Res. 2002a;4:49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Prinzing A, Durka W, Klotz S, Brandl R. Which species become aliens? Evol. Ecol. Res. 2002b;4:385–405. [Google Scholar]

- Prinzing A, Kretzler S, Badejo A, Beck L. Traits of oribatid mite species that tolerate habitat disturbance due to pesticide application. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2002c;34:1655–1661. [Google Scholar]

- Raup DM. Biological extinction in Earth history. Science. 1986;231:1528–1533. doi: 10.1126/science.11542058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read J, Stokes A. Plant biomechanics in an ecological context. Am. J. Bot. 2006;93:1546–1565. doi: 10.3732/ajb.93.10.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed TE, Schindler DE, Waples RS. Interacting effects of phenotypic plasticity and evolution on population persistence in a changing climate. Conserv. Biol. 2010;25:56–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2010.01552.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhardt K, Köhler G, Maas S, Detzel P. Low dispersal ability and habitat specificity promote extinction in rare but not in widespread species: the Orthoptera of Germany. Ecography. 2005;28:593–602. [Google Scholar]

- Remold S. Understanding specialism when the jack of all trades can be the master of all. Proc. Roy. Soc. Lon. Ser. B Biol. Sci. 2012;279:4861–4869. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodland DL, Bottjer DJ. Biotic recovery from the End-Permian mass extinction: behavior of the inarticulate brachiopod Lingula as a disaster taxon. Palaios. 2001;16:95–101. [Google Scholar]

- Roulin A, Emaresi G, Bize P, Gasparini J, Piault R, Ducrest AL. Pale and dark reddish melanic tawny owls differentially regulate the level of blood circulating POMC prohormone in relation to environmental conditions. Oecologia. 2011;166:913–921. doi: 10.1007/s00442-011-1955-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salzburger W, Mack T, Verheyen E, Meyer A. Out of Tanganyika: genesis, explosive speciation, key-innovations and phylogeography of the haplochromine cichlid fishes. BMC Evol. Biol. 2005;5:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheiner SM. Selection experiments and the study of phenotypic plasticity. J. Evol. Biol. 2002;15:889–898. [Google Scholar]

- Schippers P, Verboom J, Vos CC, Jochem R. Metapopulation shift and survival of woodland birds under climate change: will species be able to track? Ecography. 2011;34:909–919. [Google Scholar]

- Schtickzelle N, Joiris A, Baguette H, Van Dyck M. Quantitative analysis of changes in movement behaviour within and outside habitat in a specialist butterfly. BMC Evol. Biol. 2007;7:4. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-7-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shine R. Invasive species as drivers of evolutionary change: cane toads in tropical Australia. Evol. Appl. 2012;5:107–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-4571.2011.00201.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair ARE, Pech RP. Density dependence, stochasticity, compensation and predator regulation. Oikos. 1996;75:164–173. [Google Scholar]

- Soler C, Hossaert-McKey M, Buatois B, Bessière JM, Schatz B, Proffit M. Geographic variation of floral scent in a highly specialized pollination mutualism. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:74–81. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stearns SC. Life-history tactics: a review of the ideas. Q. Rev. Biol. 1976;51:3–47. doi: 10.1086/409052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S, Cheptou PO. Life-history traits evolution across distribution ranges: how the joint evolution of dispersal and mating system favor the evolutionary stability of range limits? Evol. Ecol. 2012;26:771–778. [Google Scholar]

- Syrek D, Weiner WM, Wojtylak M, Olszowska G, Kwapis Z. Species abundance distribution of collembolan communities in forest soils polluted with heavy metals. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2006;31:239–250. [Google Scholar]

- Tedesco PA, Leprieur F, Hugueny B, Brosse S, Dürr HH, Beauchard O, et al. Patterns and processes of global riverine fish endemism. Global Ecol. Biogeogr. 2012;21:977–987. [Google Scholar]

- Thiébaut G. Invasion success of non-indigenous aquatic and semi-aquatic plants in their native and introduced ranges: a comparison between their invasiveness in North America and in France. Biol. Invasions. 2007;9:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CD. Climate, climate change and range boundaries. Divers. Distrib. 2010;16:488–495. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson DWJ, Kennedy JJ, Wallace JM, Jones PD. A large discontinuity in the mid-twentieth century in observed global-mean temperature. Nature. 2008;453:646–649. doi: 10.1038/nature06982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tinsley RC. Platyhelminth parasite reproduction: some general principles derived from monogeneans. Can. J. Zool. 2004;82:270–291. [Google Scholar]

- Trewavas A. Plant intelligence. Naturwissenschaften. 2005;92:401–413. doi: 10.1007/s00114-005-0014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban RA, Titus JE. Exposure provides refuge from a rootless invasive macrophyte. Aquat. Bot. 2010;92:265–272. [Google Scholar]

- Vermeij GJ. The evolution of gigantism on temperate seashores. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 2012;106:776–793. [Google Scholar]

- Vila-Gispert A, Moreno-Amich R, García-Berthou E. Gradients of life-history variation: an intercontinental comparison of fishes. Rev. Fish Biol. Fisher. 2002;12:417–427. [Google Scholar]

- Vitalini MW, Goldsmith RM, de Paula CS, Jones CA, Borkovich KA, Bell-Pedersen D. Circadian rhythmicity mediated by temporal regulation of the activity of p38 MAPK. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:18223–18228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704900104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vitousek PM, Walker LR, Whiteaker LD, Mueller-Dombois D, Matson PA. Biological invasion by Myrica faya alters ecosystem development in Hawaii. Science. 1987;238:802–804. doi: 10.1126/science.238.4828.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Wang T. Dynamic proteomic analysis reveals diurnal homeostasis of key pathways in rice leaves. Proteomics. 2011;11:225–238. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201000065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wehenkel C, Bergmann F, Gregorius HR. Is there a trade-off between species diversity and genetic diversity in forest tree communities? Plant Ecol. 2006;185:151–161. [Google Scholar]

- Westley PAH. What invasive species reveal about the rate and form of contemporary phenotypic change in nature. Am. Nat. 2011;177:496–509. doi: 10.1086/658902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams HTP, Lenton TM. Artificial selection of simulated microbial ecosystems. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:8918–8923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610038104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson JB, Lee WG. C-S-R triangle theory: community-level predictions, tests, evaluation of criticisms, and relations to other theories. Oikos. 2000;91:77–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson DS, Yoshimura J. On the coexistence of specialists and generalists. Am. Nat. 1994;144:692–707. [Google Scholar]

- Winemiller KO. Life-history strategies and the effectiveness of sexual selection. Oikos. 1992;63:318–327. [Google Scholar]

- Wright SJ, Calderón O. Seasonal, El Niño and longer term changes in flower and seed production in a moist tropical forest. Ecol. Lett. 2006;9:35–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00851.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]