Abstract

Serving as a crucial component of mammalian cells, cholesterol critically regulates the functions of biomembranes. This review focuses on a specific property of cholesterol and other sterols: the tilt modulus χ that quantifies the energetic cost of tilting sterol molecules inside the lipid membrane. We show how χ is involved in determining properties of cholesterol-containing membranes, and detail a novel approach to quantify its value from atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Specifically, we link χ with other structural, thermodynamic, and mechanical properties of cholesterol-containing lipid membranes, and delineate how this useful parameter can be obtained from the sterol tilt probability distributions derived from relatively small-scale unbiased MD simulations. We demonstrate how the tilt modulus quantitatively describes the aligning field that sterol molecules create inside the phospholipid bilayers, and we relate χ to the bending rigidity of the lipid bilayer through effective tilt and splay energy contributions to the elastic deformations. Moreover, we show how χ can conveniently characterize the “condensing effect” of cholesterol on phospholipids. Finally, we demonstrate the importance of this cholesterol aligning field to the proper folding and interactions of membrane peptides. Given the relative ease of obtaining the tilt modulus from atomistic simulations, we propose that χ can be routinely used to characterize the mechanical properties of sterol/lipid bilayers, and can also serve as a required fitting parameter in multi-scaled simulations of lipid membrane models to relate the different levels of coarse-grained details.

Keywords: cholesterol orientation, lipid tilt modulus, transitions in liquid crystals, 7DHC, SLOS, dynorphin, molecular dynamics simulations

1. Introduction

Cholesterol plays a vital role in the function of mammalian cells [1,2,3,4]. Found distributed non-uniformly between leaflets of the plasma membrane [5], and even between different compartments of the same membrane [3,6,7,8,9,10], cholesterol (Chol) tightly regulates the organization and function of these bilayers and of membrane-associated proteins. In fact, cholesterol is so essential that even small inborn errors in cholesterol synthesis can lead to metabolic diseases that often have fatal consequences [11]. A striking example of cholesterols’ singular importance is the Smith–Lemli–Opitz syndrome (SLOS) caused by an inborn deficient activity of the enzyme 3b-hydroxysterol D7-reductase (DHCR7), responsible for the final step in cholesterol synthesis, in which 7-dehydrocholesterol (7DHC) is transformed to cholesterol [12,13], see Fig.1. In SLOS, the deficient function of DHCR7 creates an imbalance in the physiological levels of 7DHC and cholesterol, leading to multiple congenital malformations. However, it is as yet not well understood how these severe consequences result from differences in just one double bond present in 7DHC but not in cholesterol, Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

Transformation of 7-dehydrocholesterol (7DHC) to cholesterol. The final step in cholesterol synthesis from 7DHC is catalyzed by the enzyme 3b-Hydroxysterol D7-reductase (DHCR7). In this enzymatic reaction, one double bond between C7 and C8 atoms in 7DHC is transformed into a saturated bond in cholesterol. The schematic drawing highlights (red oval) C7 and C8 carbons and their associated chemistry on cholesterol and 7DHC.

Why is cholesterol so critical for membrane organization and function, and why is this role so unique to cholesterol and cannot be carried out by other sterols that are chemically nearly identical? There may be more than one possible answer. In this review we focus on one specific hypothesis. It is known that cholesterol and other sterols modify lipid membrane material properties, such as its bending rigidity [14,15]. Evidently, this modification in properties impacts membrane function, including its ability to act as an environment conducive to proper folding, organization, and function of membrane proteins. We discuss the molecular forces that potentially lead to this cholesterol effect and link its impact to a useful metric of cholesterol’s packing and order in the membrane.

Structural, thermodynamic, and mechanical properties of cholesterol-containing lipid bilayers have been extensively studied experimentally and computationally for over half a century (see [4,16,17,18,19] and references therein). These explorations have suggested that cholesterol in lipid membranes is slightly tilted with respect to the bilayer normal configuration, with the hydroxyl group positioned in the lipid headgroup region [20,21,22]. However, recent experimental studies have challenged this view by showing that in the presence of poly-unsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) [23], or even short-chain mono-unsaturated diC14:1 phosphatidylcholine (PC) lipid [24], cholesterol with its hydroxyl group can lie deep inside the hydrocarbon core. Moreover, our recent molecular dynamics investigations [25] of saturated 14:0 DMPC (dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine) lipid and Chol with different Chol content revealed that the tendency for cholesterol to tilt in the lipid membranes is strongly concentration-dependent. Thus, for low sterol concentrations (<10%) we found significant probability for Chol molecules to “lie down” in DMPC membranes. This tendency gradually diminishes with increasing Chol fraction, so that at high concentrations (>30%) cholesterol molecules were more strongly aligned with the normal to the bilayer plane. As detailed later in this Review, this transition, reminiscent of the isotropic-to-nematic transitions in classical liquid crystals in 3-dimensions [26], can be quantitatively rationalized by the interplay between entropic and enthalpic contributions that drive the equilibrium organization of sterols in the lipid membrane.

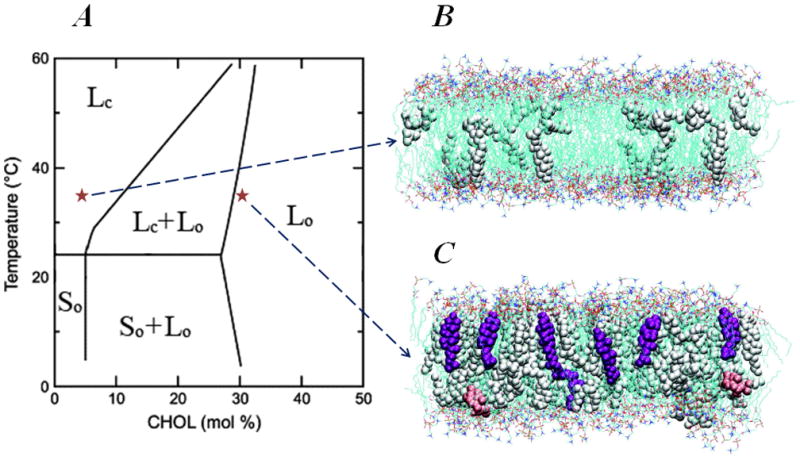

Interestingly, this change of cholesterol tilt with composition appears to closely follow the concentration-dependent phase behavior in PC/Chol binary mixtures [27] (see Figure 2), often interpreted in terms of the “condensing effect” of cholesterol [28]. Specifically, biophysical experiments established [27,29,30,31,32,33,34] (Fig. 2) that above the phase transition temperature (To) of PC and at low Chol fractions (<10%), PC/Chol binary mixtures are liquid crystalline or fluid (Lc), characterized by disordered lipid tails, fast lipid mobility, and relatively thin bilayers. In contrast, at high cholesterol content (>30%) and at T>To, where Chol reduces the area per lipid molecule by ~25% (in DMPC mixtures), a “liquid ordered” (Lo) phase sets in. In the Lo phase, lipids retain their fast diffusion, but the bilayer is thicker, as in the low temperature gel phase (So) membranes, with straight, ordered hydrocarbon lipid chains. At intermediate Chol concentrations, these Lc and Lo phases have been shown to co-exist.

Figure 2.

Phase transformation of DMPC/Cholesterol mixtures. (A) Experimental temperature-composition phase diagram of DMPC/Cholesterol mixture. Adapted from Ref. [27]. Different phases are designated as follows: Lc – liquid disordered (fluid) phase; Lo – liquid ordered phase; So – low temperature gel phase. (B–C) Panels depict snapshots from all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of DMPC/Cholesterol bilayers at 5% (B) and 30% (C) Chol molar compositions and carried out at T=35 C, illustrating the different level of cholesterol organization at high and low Chol content membranes. The corresponding points are marked on the phase diagram with red stars. On both panels DMPC lipids are shown as lines, and cholesterols are depicted in space-fill. For clarity, water molecules are removed. Chols in purple in panel C highlight increased long-range orientational order of cholesterols in 30% mixture compared to that in 5%. However, note that some instances still can be found, even at 30% Chol, when cholesterol molecules transiently orient perpendicular to the bilayer normal (pink colored space-fill in panel C). Snapshots in panels B and C were reproduced with permissions of the American Chemical Society from Ref. [25].

The discovery that cholesterol helps compartmentalize cell membranes in lipid domains [9] steered renewed interest in a comprehensive understanding of the molecular underpinnings of the thermodynamic phases of Chol-containing mixtures. Specifically, studies have identified Chol-enriched functional microdomains, or “rafts”, across plasma membranes (see, for example, [3,9,35,36,37] and references therein) that contain as well saturated lipids such as sphingomyelin (SM). By providing dynamic platforms, where plasma membrane-associated signaling proteins carry out their function, these lipid rafts play a critical role in cell signaling [36,38,39,40,41]. Interestingly, rafts are different from the surrounding lipid matrix in that these domains appear to possess properties common to the Lo phase, whereas outside these rafts the membrane is more fluid (similar to the Lc phase). But in addition to their unique phase behavior, lipid rafts also show distinguished mechanical properties [42,43]. Thus, rafts have been suggested to be thicker, and hence relatively more rigid towards bending (higher elastic modulus), with respect to the Lc phase [14,15]. As we learn how rafts assemble, function, and maintain their integrity, the following fundamental questions emerge: What is the relationship between the structural, thermodynamic, and mechanical properties of Chol-lipid membranes? And, can we define a quantitative measure that links these different characteristics of Chol-containing mixed bilayers?

In this Review, we describe a novel approach to derive an energetic parameter, the sterol tilt modulus χ that quantifies the tilt of sterol molecules inside the lipid membrane. We show how χ can be used as a link between structural, thermodynamic, and mechanical properties of cholesterol-containing lipid membranes, and illustrate how this useful measure can be obtained from sterol tilt probability distributions derived from relatively small-scale unbiased atomistic molecular dynamics simulations. We demonstrate that the tilt modulus can be considered a quantitative measure of the aligning field that sterol molecules induce inside the phospholipid bilayers. Moreover, we show that χ relates to the bending rigidity of the lipid bilayer through the tilt and splay energy contributions and at the same time conveniently characterizes the “condensing effect” of cholesterol on phospholipids. These properties of the χ parameter allow to quantify the effects of structurally similar sterols, such as cholesterol and 7DHC, on phospholipids. Lastly, we illustrate how the sterol aligning field regulates the organization and dynamics of membrane-inserted peptides, such as dynorphin A (1-17) (DynA), an endogenous ligand for κ-opioid receptor (KOR). Given the relative ease of obtaining the tilt modulus from atomistic simulations, we propose that χ could be routinely used to characterize the mechanical properties of sterol/lipid bilayers. The utility of χ is especially appealing since the related lipid tilt modulus property generally is hardly accessible in experiments. This parameter can also serve as a required fitting parameter in multi-scaled simulations of lipid membrane models to relate the different levels of coarse-grained details.

The reminder of this review is arranged as follows: first, we formulate the basic principles of sterol organization in PC membranes and establish the link between structural characteristics describing sterol tilt in phospholipid bilayers and quantitative thermodynamic measures, such as sterol orientational entropy and sterol tilt modulus. We then show how these energetic parameters, particularly the tilt modulus χ, can be used to explain mechanistically the cholesterol condensing effect, and how χ relates to the elastic properties of PC/Chol bilayers. We proceed by comparing trends in the tilt modulus of two structurally related sterols in PC membranes, cholesterol and 7DHC. Even though other thermodynamic and structural properties of PC/Chol and PC/7DHC membranes are very similar, we demonstrate that differential mechanistic effects of Chol and 7DHC on PC bilayers are witnessed in χ,. Finally, we discuss how the special membrane environment, which cholesterol creates through the orientational aligning field, regulates the organization and dynamics of transmembrane insertions such as DynA peptide.

2. Sterol tilt as a measure of membrane organization and lipid ordering

We focus on mixtures of two different sterols, cholesterol and 7DHC (Fig. 1) with DMPC lipid, a 14-carbon disaturated phospholipid that possesses zwitterionic (electrostatically neutral) PC headgroup. To explore the sterol tilt degree of freedom and to connect its effects to the structural, thermodynamic, and elastic properties of PC bilayers, we simulated DMPC/Chol and DMPC/7DHC at different sterol concentrations (ranging from 0% to 40%) and at temperature T=35°C using all-atom MD simulations (see Figure 3A; details of the employed simulation protocols can be found in our recent publications [25,44,45]). In the following sections we describe the primary results from these simulations.

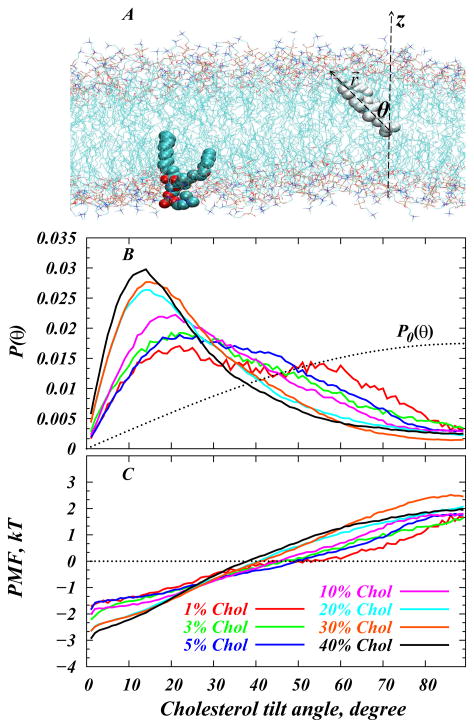

Figure 3.

Quantifying cholesterol tilt in the membrane. (A) Fragment of simulated DMPC-Cholesterol bilayer at 10% Chol concentration showing our definition of cholesterol’s tilt angle. For clarity, only one cholesterol molecule is shown (in white), and water molecules are removed. For illustration purposes, one DMPC lipid molecule is also highlighted in space-fill. The tilt angle θ of cholesterol is defined as the angle between the cholesterol ring plane vector r⃗(connecting Chol C3 and C17 atoms) and the z axis of the simulation box. The simulations were conducted at T=35 °C and on bilayer patches containing 400 lipids (DMPC and Chol) in total, using the gromacs 3.3.1 package and the united atom GROMOS96 43A1 force-field (for more details see Ref. [25]). (B) Normalized probability distributions P(θ) of cholesterol tilt angle from atomistic MD simulations of DMPC/Chol membranes at various sterol concentrations at T=35°C [25]. For each construct, converged trajectories ranging in time length between 17 ns to 35 ns have been used for the analysis. For comparison, the dotted line shows the expected distribution of tilt angles in a non-interacting system of Chol molecules where cholesterols are oriented randomly. This random distribution is given by P0(θ) = sin θ. (C) Potential of mean force (PMF) plots from the distributions in panel B (see text for details). Reproduced with permissions of the American Chemical Society from Ref. [25].

2.1. Organization of Cholesterol in phospholipid bilayers

Figure 3B shows the orientation of cholesterol molecules in DMPC bilayers in terms of the normalized probability densities P(θ) of cholesterol tilt angle in DMPC/Chol membranes for various sterol concentrations. For comparison, the same plot shows also the P0(θ) = sin θ distribution, the expected probability density of tilt angles in a hypothetical system of cholesterols where non-interacting Chol molecules orient randomly, so as to maximize their orientational entropy [25] (see also below).

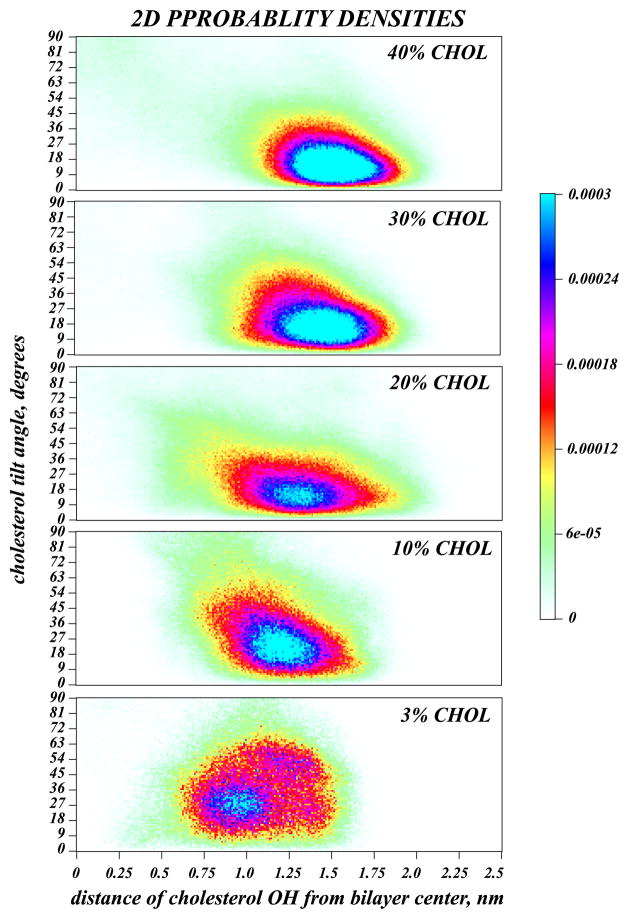

In the low Chol regime (1%–5%), the tilt distributions are broad, and Chol molecules can be found significantly tilted with respect to the membrane normal, Fig. 3B. But, as Chol concentration increases, P(θ) attains a maximum at decreasingly lower tilt angles, and the distributions become narrower. This trend suggests that, as their mole ratio increases, cholesterol molecules tend to align more strongly with respect to the bilayer normal. Interestingly, this strong alignment tendency is accompanied by a repositioning of the Chol hydroxyl group with respect to the bilayer midplane, as shown in Figures 1 and 4,. Thus, at low Chol content, a substantial fraction of sterol -OH groups can be found near the membrane center (broad distributions for 3% system in Fig. 4). However, with increasing concentration, cholesterol molecules position with their hydroxyl moiety closer to lipid headgroup area (distributions become narrower for 20–40% systems in Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Normalized probability densities (color shades) derived from MD simulations of DMPC/Chol systems (see Figure 3 captions), of finding a cholesterol molecule in a configuration with a tilt angle of θ (vertical axis) and with its hydroxyl (OH) group at a vertical distance h from the bilayer midplane (horizontal axis). θ=0 describes cholesterol with its ring plane parallel to the bilayer normal, and h=0 corresponds to the cholesterol OH group at the membrane center. Colors represent values of probability density values shown in the legend. Reproduced with permissions of the American Chemical Society from Ref. [25].

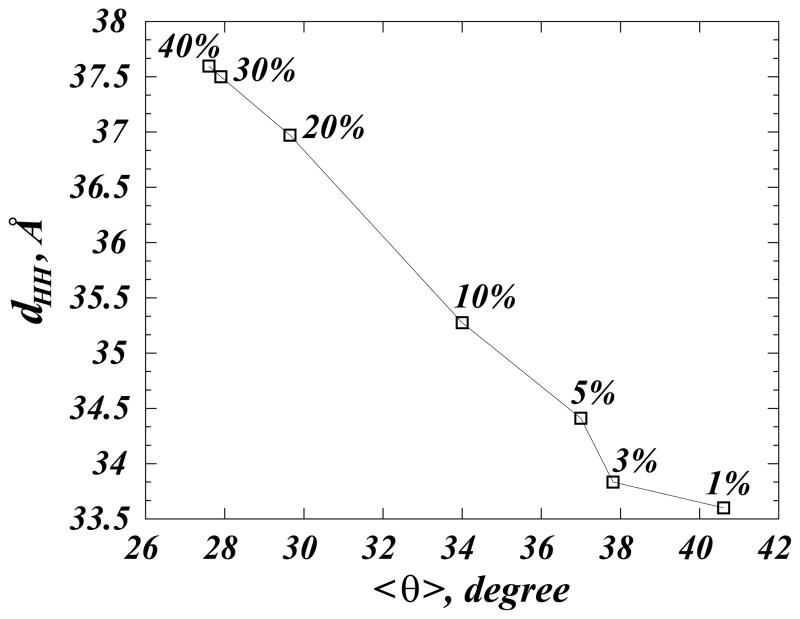

Taken together, our results suggest that cholesterol molecules in DMPC membranes undergo a transition from “lying-down” to “standing-up”. This transition is analogous to the well-studied isotropic-to-nematic (I-N) transition in liquid crystals [26], where hard-rod molecules assume preferred orientation along a common axis upon increased concentration. Concomitant with this Chol alignment, the DMPC bilayer thickens, suggestive of increased ordering of lipid hydrocarbon tails due to the condensing effect of cholesterol on PC membranes, see Figures 5 and 6. Importantly, we find that stronger aligning of Chol (smaller average tilt angle <θ>) is highly correlated with bilayer thickening (larger dHH ) in the entire 1–40% composition range (see Fig. 5 and Ref. [46]). This is important, because over the 1–40% span of cholesterol concentrations and at T=35 °C, DMPC/Chol bilayers also evolve through different thermodynamic phases, Fig. 2. The data in Fig. 5 therefore suggests that cholesterol’s ability to affect membrane ordering in various fluidity states is strongly correlated with cholesterol’s preferred orientation.

Figure 5.

Correlation between average cholesterol tilt <θ> and bilayer thickness dHH in MD simulations of DMPC/Cholesterol systems at different Chol concentrations (corresponding percentages are indicated near each symbol). The line connecting the symbols is a guide to the eye. <θ> was obtained from the P(θ) distributions shown in Figure 3, and dHH was measured as the average distance between the lipid phosphate moieties from the opposing leaflets.

Figure 6.

Comparison of membrane structural measures for cholesterol (closed symbols) and 7DHC (open symbols) at different concentrations obtained from MD simulations conducted at T=35 °C and using the NAMD suite [69] and CHARMM 36 lipid force field [70]. All systems contained 400 lipids (DMPC and sterol) (for more details see Ref. [45]). (A) Area per lipid a(x) as a function of sterol fraction; (B) Average molecular order parameter Smol for DMPC lipid tails as a function of sterol concentration; (C) Peak-to-peak (dHH) distances for different DMPC/Chol and DMPC/7DHC mixtures calculated from the corresponding electron density profiles. These dHH values are reported relative to the thickness d0 of the pure DMPC bilayer in simulations. Note that error bars, calculated from standard deviations, for some data points in all three panels are comparable to the symbol size used to plot these graphs and thus are hardly visible. Reproduced with permissions of the Royal Society of Chemistry from Ref. [45].

2.2 Mechanisms of cholesterol alignment in lipid membranes and sterol orientational order

Our results so far indicate that the structural and thermodynamic properties of sterol/lipid membranes may be correlated with sterol tilt (Fig. 5). It therefore becomes essential to understand the mechanisms that drive Chol alignment in lipid bilayers. To address this mechanistic question, we should consider several critical factors that determine the organization of cholesterol molecules in PC membranes. It is well established that pair-wise interactions between Chol and PC lipid are energetically more favorable than Chol-Chol and PC-PC pair interactions [47]. These preferential interactions give rise to the notion that cholesterols form complexes with phospholipids [48,49]. But in addition to these enthalpic factors, and similar to simple hard-rod molecules, each cholesterol also possesses degrees of freedom associated with the orientational and translational entropy of the molecule within the membrane. Due solely to orientational entropy considerations, Chols will prefer to organize in a tilted orientation with respect to the bilayer normal (see P0(θ) distribution in Fig. 3B). This is because by “lying down” in the membrane (tilting to a large θ angle), cholesterol molecules can maximize the number of possible orientations with respect to the bilayer normal (with proportion to sin θ) and thereby gain rotational degrees of freedom. Remarkably, we observe that this purely entropic consideration leads to distributions close to those we find for low Chol concentrations (1%), Fig. 3B. Here we find that P(θ) and P0(θ) distributions overlap in the 45–60° angular range, indicating that for 1% Chol the probability of finding cholesterol molecules tilted with respect to the vertical within this angular interval is the same as for randomly oriented non-interacting molecules.

As cholesterol concentration increases, there is a tendency for these molecules to “stand up” in the lipid membrane [22] (Fig. 3B and Figs. 4–5). This tendency is largely due to the two following mechanisms: 1) by “standing up” Chol’s gain “free volume” and hence translational entropy; and 2) larger lipid-mediated unfavorable Chol-Chol pair interactions tend to distance cholesterol molecules from each other. As a result of this interplay between all the energetic and entropic factors, as their concentration increases sterols more strongly align along the bilayer normal, and with that they become more strongly engaged in interactions with neighboring lipids. Consequently, condensation of cholesterols on PC lipids is found (Fig. 6A) resulting in an increase in lipid tail order (Fig. 6B) and in bilayer thickening (Figs. 5 and 6C).

Losses in orientational entropy upon increasing Chol concentration can be quantified using the corresponding P(θ) distributions by defining the orientational entropy ΔS [50,51]:

| (1) |

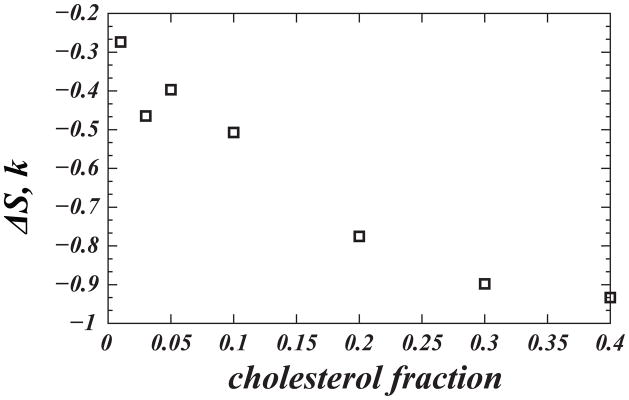

For this definition, ΔS vanishes if cholesterol molecules are oriented randomly, remains relatively high at low sterol fractions, but decreases significantly upon increasing Chol composition, Fig. 7. Importantly, the trend in ΔS appears to closely follow changes in membrane thickness (Fig. 5) and, therefore, provides additional energy-based insights into the condensing effect of cholesterol.

Figure 7.

Loss in cholesterol orientational entropy ΔS (in units of Boltzmann’s constant) with increasing cholesterol concentration. ΔS was calculated from Eq. (1) using P(θ) distributions shown in Figure 3A. Reproduced with permissions of the American Chemical Society from Ref. [25].

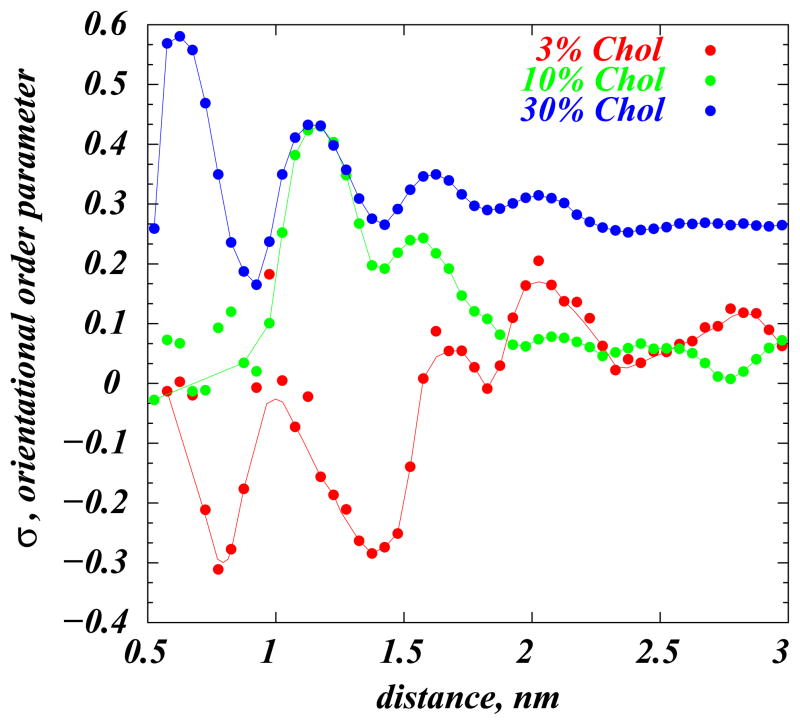

Alignment of Chol molecules in PC bilayers can be further quantified by defining an orientational order parameter for cholesterol:

| (2) |

where β(r) describes the angle between the ring planes of two cholesterol molecules found at a distance r apart. According to Eq. (2), σ is a quantitative measure for the strength of correlation between the orientation of different cholesterol molecules that are separated by a distance r. We find σ=0 for the orientationally isotropic mixture and σ=1 for a perfectly aligned sample of molecules. Figure 8 shows the dependence of σ on r for selected DMPC/Chol mixtures. The plot clearly demonstrates that for high concentrations (30%) the orientational order of Chol molecules persists over large distances (see also Fig. 2C). However, with decreasing Chol concentration, σ decreases, and for small fractions (3%) its value fluctuates around σ=0 suggesting that in the low Chol regime (where cholesterols “lie down”) orientational order is weak, and Chol’s are relatively isotropic. This behavior is somewhat reminiscent of the orientational transformations of Langmuir monolayers of amphiphilic molecules at the air-water interface, that tend to align with increasing surface density [52].

Figure 8.

Cholesterol orientational order parameter σ, Eq. (2), as a function of distance between cholesterols. Results for 3, 10, and 30% DMPC/Chol systems are shown as circles; the lines are guides to the eye. Reproduced with permissions of the American Chemical Society from Ref. [25].

3. Sterol tilt modulus: an energetic measure of preferred sterol orientation in lipid membranes

We have seen that as cholesterol concentration increases in the membrane, a strong orientational aligning field sets in, which tends to order Chol molecules along the bilayer normal. To describe this cholesterol aligning field in quantitative energetic terms, we made use of P(θ), the tilt angle probability distributions, shown in Fig. 3B. This distribution can be used to define a potential of mean force (PMF) and to introduce the sterol tilt modulus, χ, [25]. Specifically, we define PMF as:

| (3) |

Shown in Fig. 3C, this PMF is a measure of the free energy associated with tilting cholesterol molecule by Δθ=θ1−θ2 angle, so that the free energy change in this process is ΔPMF(Δθ)=PMF(θ1) −PMF(θ2). Moreover, the PMF in Eq. (3) is closely related to the empirical free energy functional defined by Kessel et al [53] to describe the energetics of the transfer of a single cholesterol molecule from the aqueous medium into a lipid bilayer at an angle θ. Specifically, based on purely enthalpic considerations, Kessel et al expanded the desolvation free energy G(θ) of cholesterol up to the quadratic term in the tilt angle, G(θ) ~ (1/2)χθ2, a representation that is generally valid only in the limit of small tilt angles. The expansion coefficient χ is termed the sterol tilt modulus, and serves a measure of the force associated with tilting of sterol molecule inside a lipid membrane. Note that G(θ) is measured with respect to the random oreintational distribution, so that for unconstrained Chol molecules G(θ) ≡ 0 for all θ.

Interestingly, the behavior of our PMF plots (Fig. 3B) for high Chol compositional mixtures (20–40%) indeed follows the quadratic form of G(θ) with θ, not only in the low angle regime, but in the entire range of θ angles (see also Ref. [45]). For low sterol concentrations, however, the PMF plots obey quadratic behavior only for lower tilt angles, deviating from θ2 function at higher tilt angles. This is expected since, as discussed above, the sterol dynamics for the low concentration regime is largely dictated by the orientational entropy, terms that are not considered in G(θ) [53]. These observations allow to extract χ from the PMF plots, by fitting the quadratic function for the low angle regime (see also Ref. [25]). The resulting values for the cholesterol tilt modulus obtained from DMPC/Chol MD simulations are shown in Figure 9.

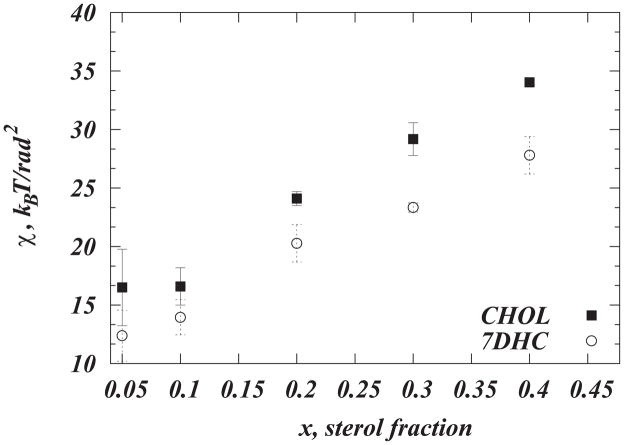

Figure 9.

Tilt modulus χ for cholesterol (solid symbols) and 7DHC (open symbols) as a function of sterol composition from MD simulations of DMPC/Chol and DMPC/7DHC membranes. For each system, χ was obtained by the fitting a quadratic function to the PMF’s shown in Fig. 3C in the [8°;20°] angular range of θ. The error bars represent standard deviations from the similar fits obtained over [8°;20°], [8°;12°], [12°;16°], and [16°;20°] angular intervals. We used bootstrapping to confirm that the values for χ remained within the presented error limits when calculated from different parts of the converged trajectories. Note the sudden increase in χ between 10% and 20% sterol composition in DMPC/Chol bilayers. The all-atom simulations presented in this plot have been conducted using the NAMD suite [69] and CHARMM 36 lipid force field [70] (for more details see Ref. [45]). Reproduced with permissions of the Royal Society of Chemistry from Ref. [45].

Remarkably, we find a strong concentration dependence of χ on cholesterol concentration, as illustrated in Fig. 9. Thus, the cholesterol tilt modulus is relatively low and unchanged up to ~10% Chol. But between 10%–20%, χ appears to exhibit a sudden increase (by ~8 kBT/rad2) and remains large upon cholesterol addition. Because larger χ values indicate a higher energy penalty for Chol to be inserted in a tilted orientation into a lipid bilayer, the trend shown in Fig. 9 also suggests that significantly more free energy must be spent to add an additional Chol molecule in a tilted orientation in high sterol membranes than in membranes lean in Chol. This is likely because membrane thickness reaches saturation levels at ~20% (Fig. 6C), while in low sterol bilayers the membrane is more fluid, and cholesterol molecules are largely non-interacting. Interestingly, an abrupt change in χ also occurs in this region of the DMPC/Chol phase diagram (10–20%, Fig. 2) where the cholesterol-enriched liquid ordered phase sets in. Taken together, our results suggest that a change in cholesterol tilt modulus upon increasing Chol concentration is closely related to the phase properties of lipid-cholesterol membranes.

4. Linking sterol tilt to membrane elastic properties: how different are structurally similar sterols?

Since the sterol tilt modulus is related to the force required to change the orientation of a sterol molecule inside the membrane, we hypothesized that there should exist a link between χ and bilayer elastic properties [45]. Indeed, when a membrane undergoes bending deformations, sterol molecules are forced to rearrange in the membrane, and on average assume a more splayed configuration with respect to one another [54,55]. Important contributions to the elastic free energy, therefore, must be associated with the tilting of a sterol molecule with respect to the bilayer normal (tilt energy) as well as with tilting of one molecule with respect to the other (splay energy). We rationalized that whenever it becomes harder to change sterol’s orientation in the membrane, a stiffening of the membrane should ensue.

The relationship between the bending rigidity and the sterol tilt modulus is perhaps best illustrated using the comparative example of two structurally very similar sterols – cholesterol and 7DHC (see Fig. 1). From experimental measurements [12,13,45] and computer simulations [45], these two sterols have been suggested to modify the elastic modulus of pure DMPC bilayers in dramatically different ways. Thus, we showed that at 30% sterol concentration, DMPC/Chol membranes are ~1.5 times more rigid compared to DMPC/7DHC bilayers. This difference has previously been linked to a cholesterol-mediated mechanism for granule malformation in SLOS disease [12], (see Introduction and Fig. 1).

But what is the mechanistic reasoning for the substantial difference between the two structurally similar molecules in their effect on the elastic properties of lipid membranes? To address this question, we have carried out extensive MD studies of DMPC/7DHC and DMPC/Chol bilayers [45] aiming to compare structural, thermodynamic and elastic properties of these binary mixtures. Our results revealed that 7DHC and cholesterol molecules affect several structural properties of DMPC lipid bilayers in a similar manner, Fig. 6. Indeed, both sterols induce a practically identical decrease in molecular area per lipid upon increasing concentration (Fig. 6A), indicating that 7DHC and Chol both exhibits a similar condensation effect on DMPC lipids. Furthermore, we find insignificant differences in the manner the two sterols affect ordering of lipid hydrocarbon tails (Figs. 6B–C), as both the lipid chain molecular order parameters (Smol) and average thickness of DMPC bilayers (dHH) show similar trends upon variation of 7DHC and cholesterol composition. Only for the 20–30% concentration range, cholesterol appears to affect Smol and dHH somewhat stronger compared to 7DHC (but note that this is probably within the Lo-Lc coexistence region of the membranes, where the simulation can be expected to be least reliable).

These insights at the molecular level, confirmed as well by experimental measurements [45], have suggested that from the structural and thermodynamic perspective, DMPC/7DHC and DMPC/Chol bilayers are very similar. And yet, our MD studies [45], together with simulations from other groups [56,57], showed that 7DHC and Chol could be expected to attain different preferential orientation in PC membranes. Thus, multiple evidences indicate that 7DHC inserts in PC bilayers in a more tilted configuration compared to Chol, suggesting that the two sterols might be characterized by different orientational entropy and tilt modulus. Indeed, we found that χCHOL is substantially higher than χ7DHC in broad range of sterol concentrations, as shown in Figure 9. In fact, the difference Δχ= χCHOL-χ7DHC becomes progressively larger as sterol content increases from 20% to 40%, Fig. 9.

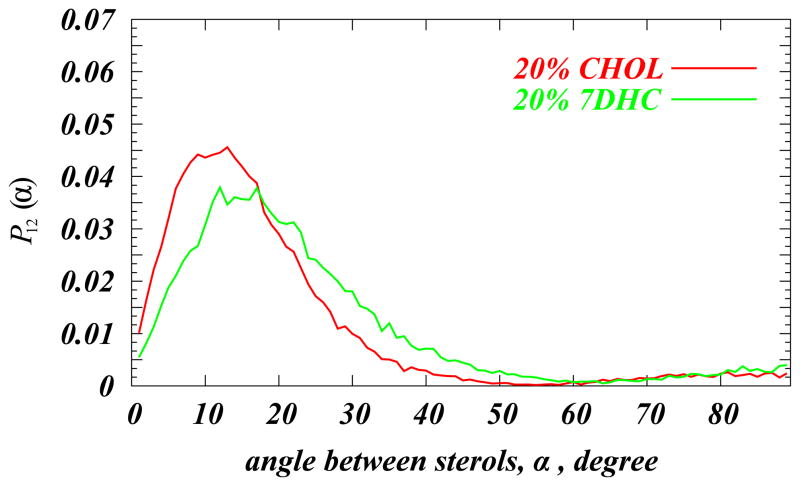

To link these trends in the sterol tilt modulus and the experimentally measured differences in the bending rigidities of DMPC/7DHC and DMPC/Chol bilayers, we first note that the tilt modulus parameter directly relates to the tilt energy component of the phenomenological elastic free energy functional of lipid bilayers [54,55]. In addition, it is useful to consider another related property, the modulus describing the tilting of one sterol molecule with respect to another, χ12, which we term the pair tilt modulus (PTM). To gain access to this parameter, we constructed the normalized density P12(α) that describes the probability of finding two sterol molecules set at an angle α between them (see Figure 10). Using a fitting procedure similar to that implemented for deriving the χ tilt modulus, we then extracted from P12(α) the corresponding χ12, a measure that estimates the free energy penalty for splay, or more precisely, for tilting one sterol molecule with respect to the other (see Ref. [45] for more details). As long as χ12 is derived for small separations between cholesterol molecules, this modulus directly relates to the splay modulus defined for lipids [54,55,58]. Moreover, when the tilt modulus tends to infinity, the splay mode of deformation becomes identical to the bending mode [54]. We found that χ12 is rather large when cholesterols are close (up to 10Å), 25 kBT/rad2 at 20% Chol, compared with 14 kBT/rad2 for 7DHC at the same concentration.

Figure 10.

Normalized probability densities P12(α) of finding pairs of sterol molecules at angle α with respect to each other. The angle α is defined as the angle between the vectors C3–C17 on two sterols, (see Ref. [45] for details). To limit the analysis to near neighbors, for these calculations, only sterol molecules within 1nm distance of each other were considered for 20% DMPC/Cholesterol (red curve) and 20% DMPC/7DHC mixtures (green curve). Reproduced with permissions of the Royal Society of Chemistry from Ref. [45].

These results suggest that the trends in both tilt modulus χ and pair tilt modulus χ12 appear to correlate with that of the bending modulus, so that for stiffer (DMPC/Chol) membranes both χ and χ12 parameters are higher. Taken together, the bending rigidity due to changes in sterol can be traced to the following molecular modes: i) tilting of a sterol molecule with respect to the local membrane normal; and ii) splaying of two sterol molecules with respect to each other. The effect of these two important deformation modes are represented within our framework, which establishes the tilt modulus χ and the pair tilt modulus χ12 as convenient measures for estimating differences in membrane stiffness in sterol-containing membranes.

5. Impact of sterol orientation and ordering on the dynamics and organization of membrane-inserted peptides

The sterol aligning field, which stems from the special arrangement of sterol molecules inside lipid membranes and can be quantified by the tilt modulus (see previous sections), can have consequences for the organization and dynamics of membrane-associated proteins and peptides [59,60]. To demonstrate this principle, we considered dynorphin A (1-17) (DynA), a 17-residue long membrane-penetrating peptide and the endogenous ligand for the κ-opioid receptor (KOR). DynA belongs to a family of GPCR ligands that reach their target receptor via the lipid membrane [61,62]. Interestingly, experimental studies have established that the activity of KOR is dependent on its localization in lipid rafts; i.e., KOR activity is higher in cholesterol-enriched cells compared to that measured in Chol-depleted cells [63].

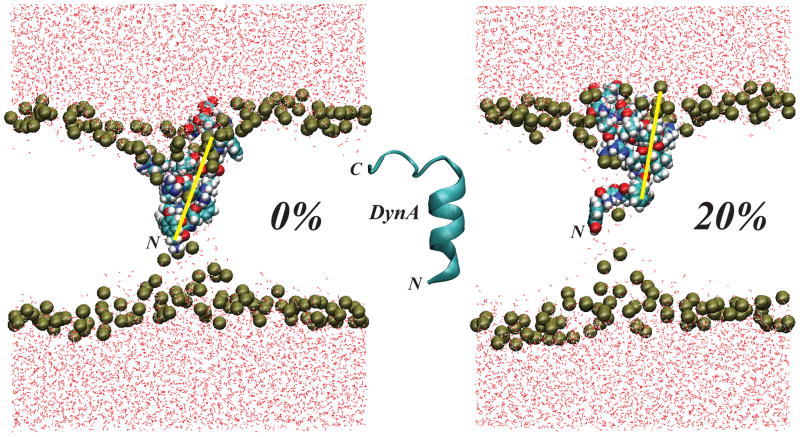

In our studies [44], we posed a mechanistic question regarding the role of cholesterol’s aligning field in positioning of DynA inside lipid membranes for favorable interactions with its target KOR protein. Our MD simulations found DynA penetrating deep inside DMPC bilayers with its N-terminal helix only ~6 Å away from the bilayer midplane, and posed in a tilted orientation, at ~50° angle with respect to the membrane normal. In contrast, DynA in DMPC/Chol membranes with 20% sterol is situated ~5 Å closer to the lipid/water interface and in a more vertical orientation. The DMPC membrane showed greater thinning around the insertion and permitted a stronger influx of water inside the hydrocarbon core than the corresponding DMPC/Chol membranes, see Figure 12.

Figure 12.

DynA-induced water permeation into sterol and DMPC mixtures (A–B) Water electron density profiles in the DMPC/Chol system with 20% sterol (averaged over the three independent simulations, panel A) and in the pure DMPC system (panel B). Shown separately are densities calculated inside a 20 Å radial shell around the inserted DynA (near) and beyond this zone (far). The electron densities were constructed by dividing the simulation cell into slabs in the z direction, and by counting the number of electrons corresponding to the atoms in each slab. The analysis was carried out only on the converged equilibrated trajectories, after 70 ns of simulations. (C) Deformation of the model membranes around DynA. Bilayer thickness (dHH), normalized by its value far from the insertion, is plotted as a function of radial distance from DynA for DMPC and DMPC/Chol systems. For cholesterol-containing bilayers, the profile is the average over three independent calculations, and the error bars indicate standard deviations calculated from the three DMPC/Chol simulations. For this analysis, the simulated box around the insertion was divided into radial slices with δr = 2 Å, and the histogram was constructed of phosphate-to-phosphate distance in each bin, and for all the frames of the converged trajectory (70–150 ns). Final profiles were obtained by proper normalization of the events in each bin of the histogram. These simulations were conducted under conditions of about 150 lipids per DynA peptide, and the time-length of each MD trajectory was ~100ns (see Ref. [44] for more details).

Interestingly, our analysis revealed that the locations of the residues on KOR implicated in interactions with DynA [44,64] correlate with DynA positioning in DMPC/Chol but not in DMPC [44,64]. This suggested that cholesterol creates favorable conditions for DynA to be positioned near the critical residues of the target GPCR, thereby facilitating the entry of DynA into the trans-membrane bundle of the KOR. With that, our predictions offered a plausible explanation for KOR localization and enhanced function in cholesterol-enriched rafts [63].

However, the following question still remains: what is the mechanism by which cholesterol molecules regulate DynA dynamics and organization in lipid membranes? The answer to this question, yet again, can be found in the sterol aligning field concept that we have been tracing in the preceding sections. Thus, the long-range orientational order that is established by Chols (Fig. 8) keeps DynA in a relatively straight orientation. As a result, charged residues on the DynA helix and at the C-terminus of the peptide will engage in strong hydrophilic interactions with the lipid headgroups and water, due to the proximity of these residues to the significant lipid/water interface created when DynA is in the upright conformation. These favorable enthalpic contributions, as well as the losses in the peptide orientational flexibility due to cholesterol condensation will limit DynA’s membrane penetration in DMPC/Chol mixtures.

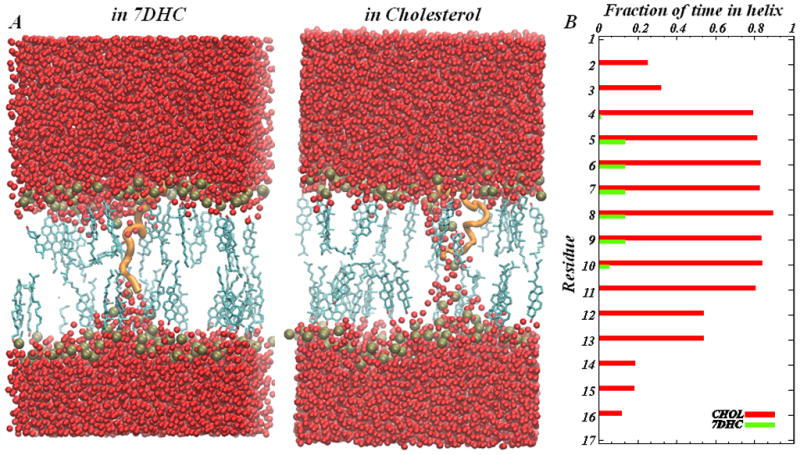

Remarkably, DynA dynamics and organization is completely altered in 7DHC-containing membranes. As illustrated in Figure 13, whereas DynA in DMPC/Chol bilayers retains most of its secondary structure, in DMPC/7DHC the peptide quickly unfolds (within a few nanoseconds). As a result, compared to its position in DMPC/Chol membranes, DynA in DMPC/7DHC bilayers is positioned deeper in the bilayer hydrophobic core (~ 3 Å closer to the bilayer midplane). Interestingly, this differential positioning of DynA in the two membrane environments also leads to somewhat different water penetration near the insertion. Thus, since DynA in DMPC/7DHC equilibrates in an extended unfolded conformation (Fig. 13), its polar N-terminus practically reaches the lipid head-group area in the opposing leaflet, therefore resulting in a lower extent of water influx to the hydrophobic core (note that compared to pure DMPC, DMPC/7DHC membrane is more rigid and therefore more resistant to bending, compare Figs. 13 and 11). On the other hand, in DMPC/Chol membranes, the N-terminus of DynA equilibrates in the vicinity of the bilayer midplane (Fig. 13), and consequently induces stronger water influx due to attractive interactions with the lipid head-groups in the opposing leaflet, and subsequent “pinching” of the bilayer. Taken together, our data clearly demonstrates how two structurally similar sterols can differentially regulate the organization of membrane peptides through the differential order that Chol and 7DHC exert in PC membranes.

Figure 13.

DynA in sterol-DMPC mixtures (A) Two snapshots from MD simulations show organization of DynA (shown in orange cartoon) in 20% DMPC/7DHC (left panel) and in 20% DMPC/Chol (right panel) model membranes. The sterols are shown in licorice representation, the lipid bilayer is depicted by the location of lipid head-group phosphate atoms (spheres in gold), and water oxygen atoms are shown in red. Other atoms are removed for clarity. (B) Helicity of the DynA peptide in the model membranes. The fraction of time each residue of DynA spends in a helix throughout the simulated trajectory is plotted for DMPC/Chol and DMPC/7DHC bilayers.

Figure 11.

Final snapshots, after 150 ns of atomistic MD simulations, of DynA peptide interacting with pure DMPC (left) and DMPC/Chol (right) membranes. DynA is in space-fill, and the membrane shape can be traced from the positions of phosphate atoms (depicted in gold spheres) on the two membrane leaflets. For clarity, the remaining lipid atoms as well as the salt atoms are removed. The water atoms surrounding membranes are shown in red. The location of DynA’s N-terminus is highlighted, and yellow lines are guides that illustrate the different extents of DynA tilting in DMPC and DMPC/Chol membranes. For completeness, a DynA cartoon model is shown in the center. The simulations have been conducted using NAMD suite [69] and CHARMM 27 force field for proteins with CMAP corrections [71]. The DynA peptide was immersed in bilayers consisting of either DMPC or DMPC mixed with 20% sterol (cholesterol or 7DHC). Three separate simulations were conducted for DynA in DMPC/sterol mixtures (for more details see Ref. [44]). Reproduced with permissions of the American Chemical Society from Ref. [44].

A related and widely recognized way in which sterols affect bilayers is to change their permeability. This property has been used routinely in studies on liposomes and their pharmacological applications to control the rate of liposome leakiness in membrane models (see, for example, Ref. [65] and citations therein). Interestingly, our results revealed (Figs. 10–11) that the addition of 20% Chol to DMPC membranes reduces the leakiness of the bilayer near a membrane-inserted DynA peptide, so that significantly fewer waters penetrate the bilayer exterior near DynA in DMPC/Chol bilayers compared to that in pure DMPC membranes. These differences in water penetration behavior can be attributed to the strong cholesterol aligning field inside DMPC/Chol membranes. Comparison between Chol- and 7DHC-containing membranes is non-trivial in this respect because of the dramatically different secondary structure the peptide assumes in each (see Fig.13).

These insights may have implications in relation to the mechanisms for flippases, an important class of membrane proteins that regulate bidirectional movement of lipids between leaflets of cell membranes in an ATP-independent manner. Surprisingly, several GPCR proteins showed ATP-independent flippase activity in in vitro experimental assays [66]. A possible flipping mechanism involves the existence of membrane-spanning water pores [67] that induce rapid flip-flop of phospholipids across bilayers. Our results suggest that the presence of cholesterol in phospholipid bilayers could affect the activity of flippase proteins by regulating the extent of water penetration inside lipid membranes.

6. Concluding Remarks

In this Review, we aimed to formulate several powerful mechanistic paradigms, such as sterol’s aligning field and sterol orientational entropy, that help to describe the organization and material properties of cholesterol-containing lipid membranes. We showed that the emergence of the sterol aligning field is related to the interplay between various crucial energetic factors, namely, orientational and translational entropy of Chol molecules, free volume effects, and pairwise enthalpic interactions between cholesterol and PC lipid molecules. At low concentrations, where the orientational entropy contribution dominates, cholesterol orientation in lipid membranes is relatively random. As Chol concentration increases, translational entropy and enthalpic interaction terms become major determining factors of membrane organization as they tend to align Chols along the bilayer normal, giving rise to the sterol aligning field. Concomitantly, there is loss in Chol orientational entropy and in free volume. It is useful to quantify the strength of the sterol aligning field using the sterol tilt modulus, χ, an empirical parameter related to the force required to tilt a sterol molecule in the lipid membrane. As we have shown, χ can be derived from simple analysis of MD simulations. This χ for Chol is analogous to the tilt modulus sometimes considered for other membrane components such as phospholipids [54,55,58], which, we suggest, can also be easily determined in simulations using a similar strategy.

Remarkably, χ shows strong dependence on sterol concentration; it is relatively small for low sterol compositions, but becomes large for sterol compositions ~20% or higher. The concentration range where χ experiences a sudden increase (10–20% Chol, Fig. 9) coincides with the region on the PC/Chol phase diagram where the Lo phase sets in (Fig. 2). It is, therefore, tempting to conjecture that the sterol tilt modulus parameter provides an important energy-based measure of the condensing effect of Chols on lipids, and with that, complements structural measures such as area per lipid, membrane thickness, or lipid tail order parameter that are routinely used to describe cholesterol condensation.

Importantly, we have demonstrated the link between the sterol tilt modulus and the bending rigidity of sterol-containing membranes. We showed how χ can be conveniently used to distinguish quantitatively mechanistic effects of two structurally very similar sterols, Chol and 7DHC, on PC membranes.

Taken together, using the concepts of sterol orientational entropy and aligning field, we were able to provide mechanistic underpinnings for a wide range of important processes across lipid membranes driven by cholesterol. For example, the emergence of the sterol aligning field and concomitant losses in the sterol orientational entropy at high concentrations of Chol provide quantitative reasoning for the differential rates of cholesterol flip-flop measured in various PC membranes. Specifically, coarse-grained MD studies have established that the rate of Chol flip-flop in model membranes reduces with increasing presence of lipids that have saturated tails [68]. Consistent with our results for low-Chol mixtures, these trends in flip-flop rates are directly related to the fact that cholesterol molecules in disordered environments, as found near polyunsaturated lipids, can more easily orient themselves perpendicular to the bilayer normal and reside close to the membrane center, where they enjoy greater orientational freedom compared to the low orientational entropy “standing up” configuration.

In conclusion, since the sterol aligning field and the sterol tilt modulus link to other structural, thermodynamic, and mechanical properties of lipid bilayers, we suggest that these sterol tilt-related mechanisms should be routinely considered when quantifying the organization of sterol-containing lipid membranes. The usefulness of this analysis is even greater given the relative ease of obtaining these measures from standard atomic MD simulations. In addition, the sterol tilt parameter should conveniently serve for the parameterization of lipid bilayer tilt and splay energy contributions in continuum mean-field based models [54,55] that describe the elastic deformations of lipid membranes.

Highlights.

Specific property related to sterol tilt in lipid membranes, the sterol tilt modulus χ, is derived from molecular dynamics simulations.

The tilt modulus χ quantifies the energetic cost of tilting sterol molecules inside the lipid membrane.

We relate χ to the bending rigidity of the lipid bilayer through effective tilt and splay energy contributions to the elastic deformations.

We demonstrate how the tilt modulus quantitatively describes the aligning field that sterol molecules create inside the phospholipid bilayers.

The cholesterol aligning field is important for the proper folding and interactions of membrane peptides.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge insightful discussions with Harel Weinstein, Ernest Mehler, and Chezy Barenholz. DH acknowledges support from the Israel Science Foundation (grants 1011/07, 1012/07) and the Stephanie Gross intramurial fund. GK is supported by NIH grant U54 GM087519. Computational resources of the David A. Cofrin Center for Biomedical Information in the HRH Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Bin Abdulaziz Alsaud Institute for Computational Biomedicine are gratefully acknowledged. The Fritz Haber Research Center is supported by Minerva Foundation, Munich, Germany.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Liscum L, Underwood KW. Intracellular cholesterol transport and compartmentation. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15443–15446. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.26.15443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liscum L, Munn NJ. Intracellular cholesterol transport. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1999;1438:19–37. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(99)00043-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Simons K, Ikonen E. How cells handle cholesterol. Science. 2000;290:1721–1726. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mouritsen OG, Zuckermann MJ. What’s so special about cholesterol? Lipids. 2004;39:1101–1113. doi: 10.1007/s11745-004-1336-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schroeder F, Nemecz G, Wood WG, Joiner C, Morrot G, et al. Transmembrane distribution of sterol in the human erythrocyte. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1066:183–192. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90185-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rukmini R, Rawat SS, Biswas SC, Chattopadhyay A. Cholesterol organization in membranes at low concentrations: effects of curvature stress and membrane thickness. Biophys J. 2001;81:2122–2134. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75860-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schroeder F, Woodford JK, Kavecansky J, Wood WG, Joiner C. Cholesterol domains in biological membranes. Mol Membr Biol. 1995;12:113–119. doi: 10.3109/09687689509038505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schroeder F, Frolov AA, Murphy EJ, Atshaves BP, Jefferson JR, et al. Recent advances in membrane cholesterol domain dynamics and intracellular cholesterol trafficking. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1996;213:150–177. doi: 10.3181/00379727-213-44047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simons K, Ikonen E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 1997;387:569–572. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xu X, London E. The effect of sterol structure on membrane lipid domains reveals how cholesterol can induce lipid domain formation. Biochemistry. 2000;39:843–849. doi: 10.1021/bi992543v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Porter FD, Herman GE. Malformation syndromes caused by disorders of cholesterol synthesis. J Lipid Res. 2011;52:6–34. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R009548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gondre-Lewis MC, Petrache HI, Wassif CA, Harries D, Parsegian A, et al. Abnormal sterols in cholesterol-deficiency diseases cause secretory granule malformation and decreased membrane curvature. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:1876–1885. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrache HI, Harries DP, Parsegian VA. Alteration of lipid membrane elasticity by cholesterol and its metabolic precursors. Macromol Symp. 2005;219:39–50. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pan J, Tristram-Nagle S, Nagle JF. Effect of cholesterol on structural and mechanical properties of membranes depends on lipid chain saturation. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2009;80:021931. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.80.021931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pan JJ, Mills TT, Tristram-Nagle S, Nagle JF. Cholesterol perturbs lipid bilayers nonuniversally. Physical Review Letters. 2008;100 doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.198103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Veatch SL. From small fluctuations to large-scale phase separation: lateral organization in model membranes containing cholesterol. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2007;18:573–582. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marsh D. Cholesterol-induced fluid membrane domains: a compendium of lipid-raft ternary phase diagrams. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:2114–2123. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elson EL, Fried E, Dolbow JE, Genin GM. Phase separation in biological membranes: integration of theory and experiment. Annu Rev Biophys. 2010;39:207–226. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Korade Z, Kenworthy AK. Lipid rafts, cholesterol, and the brain. Neuropharmacology. 2008;55:1265–1273. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2008.02.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marsan MP, Muller I, Ramos C, Rodriguez F, Dufourc EJ, et al. Cholesterol orientation and dynamics in dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine bilayers: a solid state deuterium NMR analysis. Biophys J. 1999;76:351–359. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77202-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Léonard A, Escrive C, Laguerre M, Pebay-Peyroula E, Neri W, Pott T, Katsaras J, Dufourc EJ. Location of Cholesterol in DMPC Membranes. A Comparative Study by Neutron Diffraction and Molecular Mechanics Simulation. Langmuir. 2001;17:2019–2030. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ivankin A, Kuzmenko I, Gidalevitz D. Cholesterol-phospholipid interactions: new insights from surface x-ray scattering data. Phys Rev Lett. 2010;104:108101. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.104.108101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harroun TA, Katsaras J, Wassall SR. Cholesterol is found to reside in the center of a polyunsaturated lipid membrane. Biochemistry. 2008;47:7090–7096. doi: 10.1021/bi800123b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kucerka N, Perlmutter JD, Pan J, Tristram-Nagle S, Katsaras J, et al. The effect of cholesterol on short- and long-chain monounsaturated lipid bilayers as determined by molecular dynamics simulations and x-ray scattering. Biophysical Journal. 2008;95:2792–2805. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.122465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khelashvili G, Pabst G, Harries D. Cholesterol orientation and tilt modulus in DMPC bilayers. J Phys Chem B. 2010;114:7524–7534. doi: 10.1021/jp101889k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Gennes PGPJ. The physics of liquid crystals. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Almeida PFF, Vaz WLC, Thompson TE. Lateral Diffusion in the Liquid-Phases of Dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine Cholesterol Lipid Bilayers - a Free-Volume Analysis. Biochemistry. 1992;31:6739–6747. doi: 10.1021/bi00144a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hung WC, Lee MT, Chen FY, Huang HW. The condensing effect of cholesterol in lipid bilayers. Biophysical Journal. 2007;92:3960–3967. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.099234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McMullen TPW, Lewis RNAH, McElhaney RN. Cholesterol-phospholipid interactions, the liquid-ordered phase and lipid rafts in model and biological membranes. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science. 2004;8:459–468. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mcmullen TPW, Mcelhaney RN. New Aspects of the Interaction of Cholesterol with Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine Bilayers as Revealed by High-Sensitivity Differential Scanning Calorimetry. Biochimica Et Biophysica Acta-Biomembranes. 1995;1234:90–98. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)00266-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vist MR, Davis JH. Phase-Equilibria of Cholesterol Dipalmitoylphosphatidylcholine Mixtures - H-2 Nuclear Magnetic-Resonance and Differential Scanning Calorimetry. Biochemistry. 1990;29:451–464. doi: 10.1021/bi00454a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huang TH, Lee CWB, Dasgupta SK, Blume A, Griffin RG. A C-13 and H-2 Nuclear-Magnetic-Resonance Study of Phosphatidylcholine Cholesterol Interactions - Characterization of Liquid-Gel Phases. Biochemistry. 1993;32:13277–13287. doi: 10.1021/bi00211a041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mouritsen OG, Bloom M. Mattress Model of Lipid-Protein Interactions in Membranes. Biophysical Journal. 1984;46:141–153. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(84)84007-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shimshick EJ, McConnell HM. Lateral phase separations in binary mixtures of cholesterol and phospholipids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1973;53:446–451. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(73)90682-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Simons K, Vaz WL. Model systems, lipid rafts, and cell membranes. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2004;33:269–295. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.32.110601.141803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lingwood D, Simons K. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science. 2010;327:46–50. doi: 10.1126/science.1174621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simons K, Gerl MJ. Revitalizing membrane rafts: new tools and insights. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:688–699. doi: 10.1038/nrm2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Staubach S, Hanisch FG. Lipid rafts: signaling and sorting platforms of cells and their roles in cancer. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2011;8:263–277. doi: 10.1586/epr.11.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dart C. Lipid microdomains and the regulation of ion channel function. J Physiol. 2010;588:3169–3178. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lajoie P, Goetz JG, Dennis JW, Nabi IR. Lattices, rafts, and scaffolds: domain regulation of receptor signaling at the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2009;185:381–385. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200811059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.George KS, Wu S. Lipid raft: A floating island of death or survival. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2012;259:311–319. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McIntosh TJ, Simon SA. Roles of bilayer material properties in function and distribution of membrane proteins. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2006;35:177–198. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.35.040405.102022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andersen OS, Koeppe RE., 2nd Bilayer thickness and membrane protein function: an energetic perspective. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 2007;36:107–130. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khelashvili G, Mondal S, Andersen OS, Weinstein H. Cholesterol Modulates the Membrane Effects and Spatial Organization of Membrane-Penetrating Ligands for G-Protein Coupled Receptors. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2010;114:12046–12057. doi: 10.1021/jp106373r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Khelashvili GRM, Chiu S-W, Pabst G, Harries D. Impact of sterol tilt on membrane bending rigidity in cholesterol and 7DHC-containing DMPC membranes. Soft Matter. 2011;7:10299–10312. doi: 10.1039/C1SM05937H. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aittoniemi J, Rog T, Niemela P, Pasenkiewicz-Gierula M, Karttunen M, et al. Tilt: major factor in sterols’ ordering capability in membranes. J Phys Chem B. 2006;110:25562–25564. doi: 10.1021/jp064931u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Khelashvili GA, Pandit SA, Scott HL. Self-consistent mean-field model based on molecular dynamics: application to lipid-cholesterol bilayers. J Chem Phys. 2005;123:34910. doi: 10.1063/1.1943412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Subramaniam SM, HM Critical mixing in monolayer mixtures of phospholipid and cholesterol. Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1986;91:1715–1718. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gershfeld NL. Equilibrium studies of lecithin-cholesterol interactions I. Stoichiometry of lecithin-cholesterol complexes in bulk systems. Biophys J. 1978;22:469–488. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(78)85500-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vroege GJL, HNW Phase transitions in lyotropic colloidal and polymer liquid crystals. Reports on Progress in Physics. 1992;55:1241–1309. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Almeida PF, Wiegel FW. A simple theory of peptide interactions on a membrane surface: excluded volume and entropic order. J Theor Biol. 2006;238:269–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2005.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kramer D, Benshaul A, Chen ZY, Gelbart WM. Monte-Carlo and Mean-Field Studies of Successive Phase-Transitions in Rod Monolayers. Journal of Chemical Physics. 1992;96:2236–2252. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kessel A, Ben-Tal N, May S. Interactions of cholesterol with lipid bilayers: The preferred configuration and fluctuations. Biophysical Journal. 2001;81:643–658. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75729-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fosnaric M, Iglic A, May S. Influence of rigid inclusions on the bending elasticity of a lipid membrane. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2006;74:051503. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.74.051503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Watson MC, Penev ES, Welch PM, Brown FL. Thermal fluctuations in shape, thickness, and molecular orientation in lipid bilayers. J Chem Phys. 2011;135:244701. doi: 10.1063/1.3660673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Rog T, Pasenkiewicz-Gierula M, Vattulainen I, Karttunen M. Ordering effects of cholesterol and its analogues. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788:97–121. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.08.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rog T, Vattulainen I, Jansen M, Ikonen E, Karttunen M. Comparison of cholesterol and its direct precursors along the biosynthetic pathway: effects of cholesterol, desmosterol and 7-dehydrocholesterol on saturated and unsaturated lipid bilayers. J Chem Phys. 2008;129:154508. doi: 10.1063/1.2996296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.May S, Kozlovsky Y, Ben-Shaul A, Kozlov MM. Tilt modulus of a lipid monolayer. European Physical Journal E. 2004;14:299–308. doi: 10.1140/epje/i2004-10019-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pucadyil TJCA. Role of cholesterol in the function and organization of G-protein coupled receptors. Progress in Lipid Research. 2006;45:295–333. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Burger K, Gimpl G, Fahrenholz F. Regulation of receptor function by cholesterol. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:1577–1592. doi: 10.1007/PL00000643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Schwyzer R. Peptide-membrane interactions and a new principle in quantitative structure-activity relationships. Biopolymers. 1991;31:785–792. doi: 10.1002/bip.360310624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Schwyzer R. 100 years lock-and-key concept: are peptide keys shaped and guided to their receptors by the target cell membrane? Biopolymers. 1995;37:5–16. doi: 10.1002/bip.360370104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu W, Yoon SI, Huang P, Wang Y, Chen C, et al. Localization of the kappa opioid receptor in lipid rafts. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;317:1295–1306. doi: 10.1124/jpet.105.099507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paterlini G, Portoghese PS, Ferguson DM. Molecular simulation of dynorphin A-(1-10) binding to extracellular loop 2 of the kappa-opioid receptor. A model for receptor activation. J Med Chem. 1997;40:3254–3262. doi: 10.1021/jm970252j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Barenholz Y. Cholesterol and other membrane active sterols: from membrane evolution to “rafts”. Prog Lipid Res. 2002;41:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7827(01)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Menon I, Huber T, Sanyal S, Banerjee S, Barre P, et al. Opsin is a phospholipid flippase. Curr Biol. 2011;21:149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.12.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gurtovenko AA, Vattulainen I. Molecular mechanism for lipid flip-flops. J Phys Chem B. 2007;111:13554–13559. doi: 10.1021/jp077094k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bennett WF, MacCallum JL, Hinner MJ, Marrink SJ, Tieleman DP. Molecular view of cholesterol flipflop and chemical potential in different membrane environments. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:12714–12720. doi: 10.1021/ja903529f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Phillips JC, Braun R, Wang W, Gumbart J, Tajkhorshid E, et al. Scalable molecular dynamics with NAMD. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2005;26:1781–1802. doi: 10.1002/jcc.20289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Klauda JB, Venable RM, Freites JA, O’Connor JW, Tobias DJ, et al. Update of the CHARMM All-Atom Additive Force Field for Lipids: Validation on Six Lipid Types. Journal of Physical Chemistry B. 2010;114:7830–7843. doi: 10.1021/jp101759q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Klauda JB, Brooks BR, MacKerell AD, Jr, Venable RM, Pastor RW. An ab initio study on the torsional surface of alkanes and its effect on molecular simulations of alkanes and a DPPC bilayer. J Phys Chem B. 2005;109:5300–5311. doi: 10.1021/jp0468096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]