Abstract

DypB, a dye-decolorizing peroxidase from the lignolytic soil bacterium Rhodococcus jostii RHA1, catalyzes the peroxide-dependent oxidation of divalent manganese (Mn2+), albeit less efficiently than fungal manganese peroxidases. Substitution of Asn246, a distal heme residue, with alanine, increased the enzyme’s apparent kcat and kcat/Km values for Mn2+ by 80- and 15-fold, respectively. A 2.2 Å resolution X-ray crystal structure of the N246A variant revealed the Mn2+ to be bound within a pocket of acidic residues at the heme edge, reminiscent of the binding site in fungal manganese peroxidase and very different to that of another bacterial Mn2+-oxidizing peroxidase. The first coordination sphere was entirely comprised of solvent, consistent with the variant’s high Km for Mn2+ (17 ± 2 mM). N246A catalyzed the manganese-dependent transformation of hard wood kraft lignin and its solvent-extracted fractions. Two of the major degradation products were identified as 2,6-dimethoxybenzoquinone and 4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde, respectively. These results highlight the potential of bacterial enzymes as biocatalysts to transform lignin.

INTRODUCTION

Lignin is a complex aromatic polymer that comprises approximately 25% of the land-based biomass. It occurs in tight association with cellulose and hemicellulose, to form lignocellulose, the rigid, recalcitrant material in woody plants. Deconstructing this lignocellulose is critical to using biomass as a renewable source of energy and biomaterials(1, 2). Lignin itself is of burgeoning interest as a sustainable source of aromatic compounds, resins and other biomaterials(1). Nevertheless, lignocellulose-derived products are not economically viable due in part to the energy-intensive processes used to deconstruct biomass. Biocatalysts offer a greener, more energy-efficient means to extract increased value from biomass.

The best characterized lignin-degrading enzymes are those secreted by white rot fungi, such as Phanerochaete chrysosporium. These include lignin peroxidase (LiP)(3), manganese peroxidase (MnP)(4), versatile peroxidases and laccases(5). LiP and MnP are believed to oxidize small compounds or metals that function as mediators for lignin oxidation. Thus, LiP oxidizes veratryl alcohol which, in turn, oxidizes non-phenolic structures in lignin. For its part, MnP oxidizes Mn2+ to Mn3+, which is chelated by organic acids and oxidizes phenolic structures present in the lignin. Oxidized Mn3+ also generates peroxy radicals, via lipid peroxidation, which oxidize the non-phenolic structures in lignin(6, 7). Nevertheless, the industrial applications of fungal enzymes have been limited by the challenge of producing these post-translationally modified proteins in commercially viable amounts(8). By contrast, bacterial ligninases should be much easier to produce.

In the 30 years since the bacterial degradation of lignin was first reported(9), at least three classes of lignolytic bacteria have been identified: actinomycetes, α-proteobacteria, and γ-proteobacteria(10). Nevertheless, the genes and the enzymes involved in bacterial lignin degradation are not as well characterized as their fungal counterparts and lignin degradation products have not been identified. Bacterial enzymes that have been implicated in lignin degradation include a lignin-type peroxidase from Streptomyces viridisporus T7A, ALiP-P3(9) and putative laccases and peroxidases from Enterobacter lignolyticus SCF1(11). However, the best characterized are two actinobacterial dye-decolorizing peroxidases (DyP) that share ~20% amino acid sequence identity: DypB of Rhodococcus jostii RHA1(12) and DyP2 of Amycolatopsis sp. 75iv2(13). Both enzymes catalyze the peroxide-dependent oxidation of Mn2+ and the Cα-Cβ bond cleavage of β-aryl ether lignin model compounds(14, 15). DyP2 also possesses oxidase activity, catalyzing the O2-dependent oxidation of Mn2+. Nevertheless, MnP from P. chrysosporium(15) catalyzes the Mn2+ oxidation ~30,000- and 40-fold more efficiently than DypB and DyP2(14), respectively. Structural data identified a Mn2+-binding site in DyP2(14) that is located ~15 Å from the heme, in contrast to the site at the heme edge in MnP. The residues constituting the site in DyP2 are not conserved in other DyPs.

DyPs were first identified in the fungus Thanatephorus cucumeris Dec1 for their ability to degrade anthraquinone dyes(16). Genomic analyses have since revealed their occurrence in a wide range of bacteria and fungi(12, 17). Although the physiological role of DyPs remains unclear, the members of the family catalyze a range of reactions of biotechnological significance, including the oxidation of dyes, methoxylated aromatic compounds(18), carotenoids(19), and lignin(12, 14, 15). DyPs belong to the CDE superfamily of heme peroxidases(20), sharing a ferredoxin-type structural fold with chlorite dismutases, and have been classified into four phylogenetically distinct subfamilies(12, 14, 15): DypB, DyP2 and DyPDec1 belong to the B, C and D subfamilies, respectively. DyPs share three conserved residues in the heme-binding pocket: Asp153 and Arg244 (numbering of DypB from RHA1) on the distal face and His226, the proximal ligand to the heme iron. The peroxidative cycle of DyPs is similar to that of other peroxidases in that the ferric enzyme reacts with H2O2 to produce the highly oxidizing intermediate Compound I ([Fe4+=O Por•]+). However, the catalytic machinery seems to function differently in the different classes of DyPs since the distal aspartate is essential for peroxidase activity in DyPDec1, a D-type Dyp,(17) but not in DypB(21). Indeed, substitution of Asp153 had no effect on the formation of Compound I in DypB, but shortened its half-life by over three orders of magnitude to ~0.13 s(21).

Herein, we characterized the peroxidative oxidation of Mn2+ by DypB and investigated its utility for transforming lignin. The roles of Asp153 and Asn246 in this reaction were studied, and the Mn2+-binding site of the enzyme was elucidated using X-ray crystallography. Finally, the ability of a DypB variant to transform solvent-fractionated hardwood kraft lignin (HKL) was investigated and lignin transformation products were identified.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Mn2+ oxidation by DypB and the variants

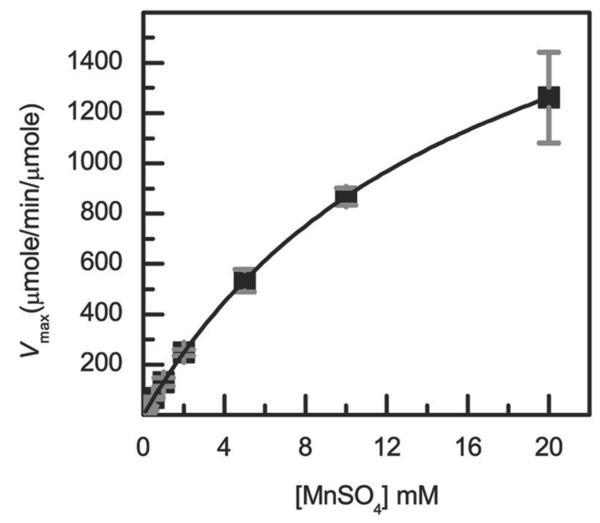

We had previously discovered that the distal heme pocket variants of DypB, D153A and N246A, have higher peroxidase activity than wild-type (WT) DypB using ABTS as a reducing substrate(21). We therefore investigated the ability of these variants to catalyze the peroxide-dependent oxidation of Mn2+ using a steady-state kinetic assay monitoring the production of the Mn3+-malonate complex at 270 nm (Supplementary Figure 1). The WT and variant DypBs each displayed Michaelis-Menten behavior with respect to Mn2+ concentration (e.g., Figure 1). Strikingly, the N246A and D153A variants oxidized Mn2+ at maximal rates (kcat) that were 80- and 3-fold higher, respectively, than WT DypB (Table 1). The Km values for Mn2+ were comparable in WT and D153A, but ~6 fold higher for N246A (Figure 1, Table 1). By contrast, the D153A/N246A double variant did not detectably oxidize Mn2+. This lack of activity is consistent with the very high Km value of this variant for H2O2 (~5 mM)(21).

Figure 1.

Steady-state kinetic analysis of Mn2+ oxidation by N246A. Reactions contained 20 nM N246A and 1 mM H2O2 in 50 mM malonate, pH 5.5 at 25 °C. The solid line represents a best fit of the Michaelis-Menten equation to the data using LEONORA.

Table 1.

Apparent steady-state kinetic parameters of WT DypB and its distal residue variants for Mn2+.a

The increased Mn2+-oxidation activities of N246A and D153A presumably reflect the increased reactivity of Compound I in these variants. More particularly, the kcat/Km values of these variants for H2O2 as well as their second order rate constants with H2O2 are very similar to those of WT DypB (~105 M−1s−1)(21). By contrast, the half-life of Compound I in these variants is ~4,000-fold shorter and their kcat values, determined using either ABTS(21) or Mn2+, are greater. While a variety of factors can affect the reactivity of Compound I, one obvious one is reduction potential. Indeed, the substitution of Asn246 and Asp153, located 3.1 Å and 3.5 Å from the distal solvent ligand of the heme iron, is expected to raise the redox potential of the heme. By analogy, substitution of Val68 in myoglobin, located on the distal face of the heme, with aspartate and asparagine reduced the redox potential by 200 mV and 80 mV, respectively(22). Nevertheless, further characterization of the WT and the variants is required to determine the reason for increased reactivity of N246A. It is also unclear why N246A appears to be a more efficient manganese peroxidase than D153A. However, it is noted that the kcat value of D153A is apparent since this variant’s Km value for H2O2 is 0.5 mM(21).

Although the increase in the Mn2+-oxidation activity of N246A versus the WT (80-fold increase in kcat) is significantly greater than that in the ABTS-oxidation activity (1.7-fold increase in kcat)(21), the specificity (kcat/Km) of N246A for Mn2+ is 50- and 200-fold lower, respectively, than that of DyP2 and MnP (Table 1). This presumably reflects the fact that DypB is not a very efficient peroxidase as judged by its relatively low second order rate constants with H2O (~105 M−1S−1)(21), which is approximately two orders of magnitude lower than that of efficient peroxidases, such as HRP(23).

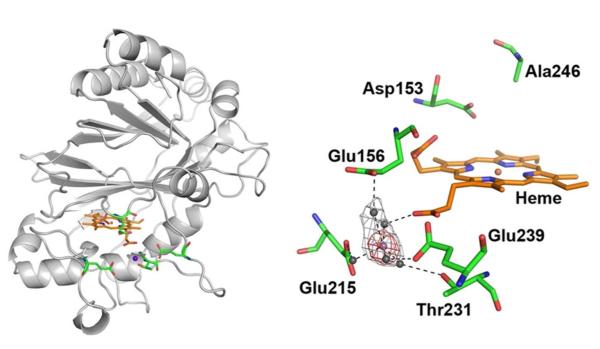

Identification of a Mn2+-binding site

To characterize the interaction between DypB and Mn2+, the N246A variant was crystallized in the presence of the divalent metal ion. X-ray fluorescence scans of the crystals exhibited strong peaks for iron and manganese (not shown). To identify the potential Mn2+-binding site, a 2.2 Å resolution and a manganese K-edge dataset were collected from a single crystal. The structure of the N246A:Mn2+ complex was very similar (r.m.s.d for Cα atoms <0.3 Å) to WT DypB (PDB ID: 3QNR). An anomalous dispersion map generated from Mn2+ K-edge data revealed a large peak (~14 σ) located in an acidic patch adjacent heme propionate-D, comprised of Glu156, Glu215, Thr231, and Glu239 (Figure 2). The 2Fo-Fc electron density map indicates the presence of a hydrated metal coincident with the peak in the anomalous map. Mn2+ was modeled at 50% occupancy to minimize residual difference density and by comparison to anomalous peak heights for full-occupancy iron (~6.5 σ) and sulfur (~7.7 σ) in the structure. The first Mn2+ coordination sphere was occupied exclusively by solvent molecules with distances refined between 1.8 and 2.4 Å; however, poorly defined density for the coordinating waters suggests the solvent species are present in multiple conformations and potentially occupy the Mn2+ site in its absence. The waters refined in distorted octahedral geometry, but due to weak density at the sixth coordination site, only five water molecules could be unambiguously modeled coordinating Mn2+ (Figure 2). The second coordination sphere includes hydrogen bonds between coordinating waters and Glu156, Glu215, Thr231, Glu239 and heme propionate-D(24).

Figure 2.

The active site and Mn2+-binding pocket of N246A. Residues (green) and heme (orange) are shown as sticks. The iron (dark orange), solvent species (grey) and Mn2+ (magenta) are shown as spheres. The Mn2+-binding site is shown with an omit Fo-Fc map (grey mesh) contoured at 4.2σ, and a Mn-anomalous map (red) contoured at 8σ. Figures were made using PyMol.

The differences and similarities between the respective Mn2+-binding sites of N246A, DyP2 and MnP are consistent with the respective reactivities of these enzymes with Mn2+. First, the enzyme with the lowest kcat value for Mn2+ (Table 1) is the one in which the Mn2+-binding site is located furthest from the heme. Thus, the Mn2+-binding sites of N246A and MnP(24) are located close to the heme edge and involve a heme propionate. By contrast, that of DyP2 is ~15 Å away from the heme(14). The lower kcat value of DyP2 for Mn2+ is striking given that it is otherwise a more efficient peroxidase than DypB. The nature of the Mn2+-binding sites in the three enzymes also reflects their relative Km values for Mn2+ (Table 1). Thus, N246A, whose Mn2+-binding site has no carboxylates in the first coordination sphere of the metal ion, has a Km values for Mn2+ that is 300- and 80-fold higher than MnP and DyP2, respectively. Similarly, MnP, whose Mn2+-binding site comprises three glutamates and a heme propionate in the first coordination sphere of the metal ion, has a lower Km value for Mn2+ than DyP2, which has two or three carboxylates in its site. The importance of the first coordination sphere is further illustrated by the effect of substituting Glu39 with Asp in MnP(25): this relatively minor perturbation raised the enzyme’s Km for Mn2+ by ~20-fold (Table 1(25)).

The Mn2+-binding residues in DypB and DyP2 are not well conserved in DyPs(12, 14), suggesting that the binding of the divalent metal ion may not be physiologically relevant. Nevertheless, the structural models of the respective complexes indicate that the Mn2+-oxidation activity of the DyPs could be improved, either by engineering a Mn2+-binding site at the heme edge in DyP2 or engineering a higher affinity site in N246A. Nevertheless, attempts to engineer Mn2+-binding sites into peroxidases have been met with limited success. For example, while cytochrome c peroxidase (CcP) has been engineered (MnCcP) to bind Mn2+ at a similar location as in MnP(26), the kcat and kcat/Km values of the most efficient Mn2+-oxidizing CcP variant were ~102- and 104-fold lower, respectively, than those of MnP from P. chrysosporium(25, 27) (Table 1). The limited success in improving the Mn2+-oxidizing activity of CcP suggests that other factors such as reduction potential of the heme may also have to be engineered.

Mn2+-dependent transformation of solvent-fractionated HKL by N246A

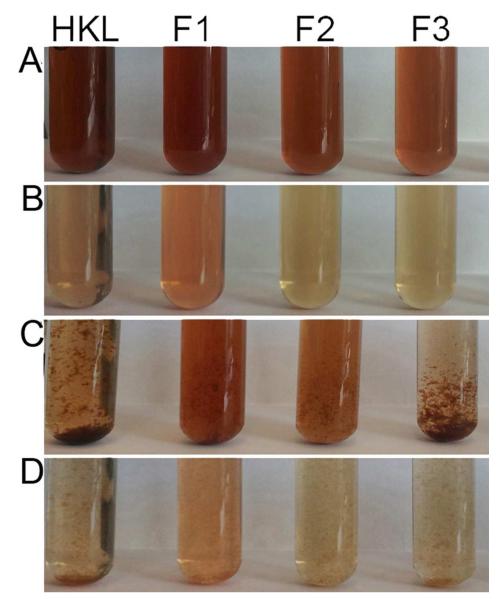

The ability of N246A to catalyze the manganese-dependent transformation of lignin was investigated. In these experiments, the variant was incubated with hardwood kraft lignin (HKL) and each of 3 solvent-fractionated samples (F1 to F3). As will be described elsewhere (Chowdhury, Wei, Kadla, unpublished), the average molecular weights of F1, F2 and F3 were 600, 1200 and 3200 g mol−1, respectively, similar to reported values (28). By comparison, the average molecular weight of unfractionated HKL was 3300 g mol−1. Further, HKL and F3 contained 7.5% and ~1% carbohydrate while F1 and F2 did not contain detectable amounts. All transformations were performed in the presence of MnSO4 (20 mM sodium malonate, pH 5.5, 15% DMSO).

Upon the addition of H2O2, the color of the reaction mixture changed to burgundy within 10 min (Figure 3A). The electronic absorbance spectrum of these samples revealed a maximum at 495 nm and that the highest change in absorbance was observed for samples containing HKL-F1 (data not shown). Control reactions containing no enzyme did not show the same color formation (Figure 3B). Incubation for 60 min resulted in the formation of precipitate in most of the reactions (Figure 3C). The amount of precipitate accounted for up to 90% of the lignin (dry weight) used in the reaction. In general, control incubations with no enzyme developed significantly less precipitate (< 50% of initial lignin content) (Figure 3D). Similar results were obtained using samples of softwood kraft lignin and its solvent-extracted fractions (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Incubation of HKL and its fractions with N246A. Reaction mixtures contained 0.25 mg ml−1 of a preparation of HKL, 100 nM N246A, 20 mM MnSO4, and 0.5 mM H2O2 (20 mM sodium malonate, pH 5.5, 15% DMSO) and were incubated at 30 °C. The Panels (A) and (C) show reactions after 10 and 60 min, respectively. Panels (B) and (D) are the corresponding reactions performed in the absence of enzyme. The lignin preparation used in each reaction is identified at the top of each column.

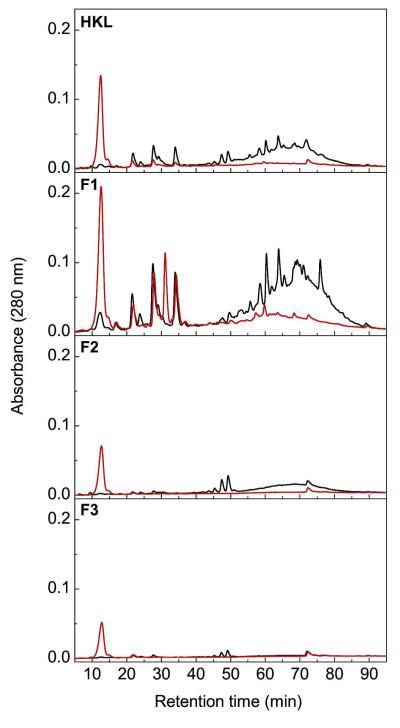

Chromatographic analyses of transformed HKL

The soluble transformation products were characterized chromatographically. Thus, the soluble portion of the reactions described in the previous section was collected after 60 min of incubation and purified using solid-phase extraction. Analysis of this extract using reverse phase HPLC revealed that in enzyme-treated samples a number of peaks with high retention times (tr) disappeared and a number of new peaks with low tr appeared (Figure 4). The new peaks had λmax between 280–310 nm, consistent with them representing aromatic compounds, and were of greater intensity in reactions performed with HKL-F1 than with other samples of HKL. The two most prominent new peaks had tr of ~12 and 31 min and λmax at 289 and 306 nm, respectively. The peak that decreased most noticeably had a tr of ~60 min and a λmax at 270 nm. More generally, the spectral features of this peak closely resemble those of HKL-F1 in solution (data not shown). Time course studies showed that the new peaks appeared with similar kinetics during the transformation of the lignin and that the reaction was essentially complete within 30 min (Supplementary Figure 2). The more efficient transformation of HKL-F1 as compared to the other lignin fractions is consistent with the former’s lower average molecular weight and content of hemicellulose. Further, the formation of precipitate during the enzymatic reactions suggests that some polymerization also occurs, as has been reported in MnP-catalyzed reactions (29). A comparison of the transformation of HKL-F1 by DypB and N246A, respectively, was also consistent with the kinetic data. Thus, the yield of the products with tr ~ 12 and 31 min was ~ 25% and 2%, respectively, in the presence of DypB as compared to N246A (Supplementary Figure 3).

Figure 4.

Chromatographic analyses of the Mn2+-dependent transformation of HKL with N246A. Reactions were performed for 60 min essentially as described for Figure 3. The soluble products were extracted and analyzed using reverse phase HPLC. The elution profiles of reactions incubated with (red traces) and without (black traces) N246A are shown.

Identification of the HKL-F1 degradation products

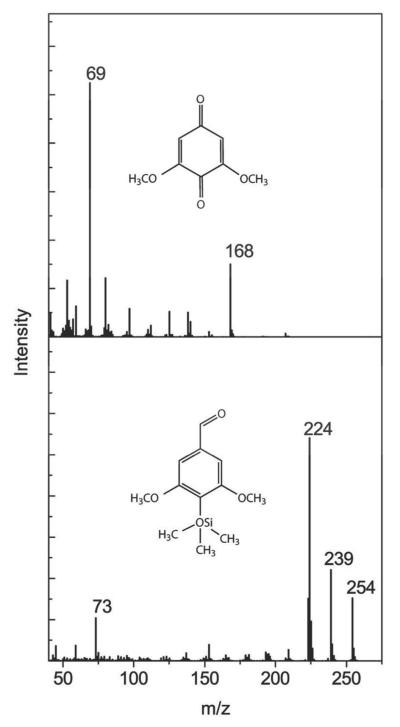

Gas chromatography (GC) coupled mass spectrometry (MS) was used to identify the compounds resulting from the N246A-catalyzed transformation of HKL-F1. Consistent with the HPLC analyses, the GC analyses of the soluble portion of enzyme-treated HKL-F1 revealed the disappearance of several peaks and the appearance of new ones as compared to controls containing no enzyme (Supplementary Figure 4). Mass spectra of the new peaks were consistent with the latter being lignin-derived aromatic compounds (data not shown). The HKL-F1 transformation products eluting at 12 and 31 min, respectively, were purified using semi-preparative HPLC and analyzed using GC-MS. The product with tr = 12 min on the analytical reverse phase column had a tr = 10.8 min on the GC (Supplementary Figure 5A). The mass spectrum of this sample (Figure 5, top panel) was consistent with 2,6-dimethoxy-benzoquinone (2,6-DMBQ) in a catalogue search. Its identity was confirmed using authentic 2,6-DMBQ, which had the same tr (on HPLC and GC (Supplementary Figure 5B)), mass spectrum and electronic absorption spectrum as the lignin-derived product. The product with tr = 31 min on the analytical reverse phase column was similarly purified and identified. Thus, this product had tr = 13.8 min on GC (Supplementary Figure 5C) and a database search revealed that its mass spectrum (Figure 5, bottom panel) corresponded to that of trimethylsilyl derivative of 4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxybenzaldehyde (syringaldehyde). This was confirmed using authentic syringaldehyde, whose tr (on HPLC and GC (Supplementary Figure 5D)), mass spectrum, and electronic absorption spectrum matched those of the lignin-derived compound. Using the authentic standards as control, the yield of 2,6-DMBQ and syringaldehyde was determined, respectively, as 21 and 18 μg mg−1 HKL-F1.

Figure 5.

Structural characterization of transformation products obtained from HKL-F1. The mass spectra of the purified products eluting at tr = 12 min (top) and tr = 31 min (bottom) are shown. Structures corresponding to the fragmentation patterns are shown in inset.

The production of 2,6-DMBQ and syringaldehyde is consistent with previous reports on MnP(30). Thus, MnP has been shown to oxidize phenolic arylglycerol and aryl ether lignin model compounds, producing 2,6-DMBQ and syringaldehyde. Further consistent with our results, syringaldehyde is produced during the non-enzymatic oxidation of HKL as a result of the cleavage of the Cα-Cβ bond (31, 32). The production of benzoquinone structures, including 2,6-DMBQ, indicates the cleavage of the C1-Cα bond (32) and may also explain the burgundy color that develops during incubation of HKL with N246A. Finally, 2,6-DMBQ and syringaldehyde have been produced during the oxidation of the non-phenolic lignin model 2-(2,6-dimethoxy-4-formylphenoxy)-1,3-dihydroxy-1-(4-ethoxy-3-methoxyphenyl)-propane by laccase, a phenol oxidizing enzyme, in the presence of 1-hydroxybenzotriazole (33). It would be interesting to determine if N246A can catalyze similar transformation of non-phenolic lignin in the presence of 1-hydroxybenzotriazole.

CONCLUSIONS

This study shows that a bacterial peroxidase can be engineered to improve its peroxide-dependent Mn2+ oxidation and lignin transformation capabilities. Although the variant DypB is not as efficient as MnP or DyP2, the structural data are consistent with the high Km value of the enzyme for Mn2+ and provide a basis for further optimizing the Mn2+-oxidizing activity of DypB. It is unclear whether Mn2+-oxidation is physiologically relevant in DyPs, or whether DypB or DyP2 are even secreted. Nevertheless, there are DyP homologues which have an alanine residue at the position equivalent to Asn246 in DypB (12), including a DyP-type peroxidase from Streptomyces viridochromogenes. Moreover, the residues involved in binding Mn2+ in DypB are also conserved in the S. viridochromogenes enzyme. Finally, the demonstration that N246A catalyzes the Mn2+-dependent transformation of lignin and that fractionated lignins are transformed more efficiently highlights the potential of bacterial ligninolytic enzymes as biocatalysts.

METHODS

Reagents and Chemicals

HPLC grade DMSO was from Alfa Aesar. All other reagents and chemicals were purchased from SIGMA-Aldrich, ACROS, MP Bio-medicals, or Fisher and were used without further purification. HKL was provided by FPInnovations (Pulp, Paper and Bioproducts) and was solvent-fractionated essentially as will be described elsewhere based on an established protocol (28). Water was purified using a Barnstead NANO pure UV apparatus (Barnstead International) to a resistivity of greater than 17 MΩ cm.

Preparation of recombinant DypB

Wild type DypB (WT), D153A, N246A and D153A/N246A were produced as apo-proteins using pETDB, pETDBD153A, pETDBN246A, and pETDBD153AN246A, respectively, and were reconstituted with hemin chloride as described previously (12, 21).

Steady-state Kinetic Analysis

Apparent steady-state kinetic parameters for Mn2+ were determined by following Mn3+-malonate formation using a previously described spectrophotometric assay(12). The assay was performed in 1 ml of 50 mM sodium malonate, pH 5.5 at 25.0 ± 0.5 °C containing 0.2–40 mM MnSO4 and 20 nM N246A. The reaction was initiated by adding 1 mM H2O2 and the initial rates were monitored at 270 nm (ε270 = 11.9 mM−1cm−1)(34). Steady-state kinetic equations were fit to the data using LEONORA(35).

X-ray crystallography

Crystals of N246A were grown as described previously (15). For co-crystallization of MnCl2 and N246A, protein samples (10 mg ml−1, 20 mM MOPS pH 7.5, 50 mM NaCl) were incubated with 167 mM MnCl2 at room temperature for 1 h. Drops were made from 2 μl of protein-MnCl2 solution and 2 μL of well solution consisting of 0.1 M sodium acetate trihydrate, pH 4.5, 3 M NaCl and crystals formed overnight. To prepare crystals for mounting, they were briefly soaked in well solution supplemented to 16% glycerol and then flash frozen by immersion in liquid nitrogen. Diffraction data were collected on beamline 7-1 at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource. Data were processed using Mosflm (36, 37) and scaled with Scala (38). The structure was solved using N246A (PDB ID: 3VEE) directly in Refmac (39) from the CCP4 program suite (40) and manually edited using Coot(41). Data are deposited in the RCSB PDB under accession number 4HOV.

HPLC-based assay of lignin transformation

Mn2+-dependent lignin transformation was routinely evaluated using reverse-phase HPLC. Analyses were performed using a Waters 2695 Separations module equipped with a Waters 2996 photodiode array detector. Reactions of 5 ml containing 0.25 mg ml−1 preparations of HKL or its fractions were incubated with 20 mM MnSO4 (20 mM sodium malonate, pH 5.5, 15% DMSO) with or without 100 nM N246A. The reaction was initiated by the addition of H2O2 to 0.5 mM. After incubation for 60 min, the precipitate was removed by centrifugation (4,000 g × 30 min) and filtration (0.45 μm), washed 3 times with 1 ml deionized H2O, and dried under vacuum. The soluble portion was acidified using formic acid (0.5% final concentration) and was then extracted using solid-phase extraction (SPE). Briefly, the samples were loaded onto a column packed with a C18 SPE matrix (Phenomenex) equilibrated with 0.5% formic acid. The resin was washed using 5 column volumes of 0.5% formic acid. The reaction products were eluted from the resin using 100% MeOH. The eluate was dried under nitrogen. Air-dried samples were resuspended in 300 μl of 0.5% formic acid, 20% methanol and filtered (0.2 μm). Samples of 90 μl were injected onto a 150 mm × 3.00 mm C18 column (100 Å, 5 μ; Phenomenex) operated at a flow rate of 0.7 ml min−1 and equilibrated with aqueous 0.5% formic acid, 10% methanol. Reaction products were eluted using the following gradient: 10% MeOH for 5 min, 10 to 30% MeOH over 40 min, 30 to 70% MeOH over 45 min, and 100% MeOH for 5 min.

A larger scale, 1L reactions were performed using HKL-F1 to maximize the product yield. This reaction was incubated for 3 h with fresh MnSO4, H2O2 and N246A added every hour. Following incubation, the products were extracted as described above. The eluate from the SPE resin was vacuum-dried and freeze-dried. Dried samples were suspended in 50% MeOH, filtered (0.2 μm) and loaded (100 μl) onto a 100 × 10 mm PFP(2) column (5 μ, 100; Phenomenex) operated at 3 ml min−1. The products were eluted as described above. Fractions eluting at tr = 12 and 31 min were collected separately and dried under nitrogen gas. The fraction eluting at tr = 12 min was dissolved in 100 μl 30% acetonitrile, filtered (0.2 μm) and injected onto the above-described C18 column equilibrated with 70 mM ammonium acetate, pH 8.5 and operated at a flow rate of 1 ml min−1. The sample was eluted using the following gradient: 0% acetonitrile for 2 min; 0 to 15% acetonitrile for 21 min; 15–100 to acetonitrile from 2 min.

Gas chromatography-Mass spectrometry (GC-MS) of HKL

Samples were analyzed directly or were first derivatized using BSTFA+TMCS- (99:1). GC-MS was performed using an HP 6890 series GC system fitted with an HP 5973 mass-selective detector and a 30 m × 250 μm HP-5MS Agilent column. The operating conditions were: TGC (injector), 280 °C; TMS (ion source), 230 °C; oven time program (T0 min), 120 °C; T2 min, 120 °C; T30 min, 260 °C (heating rate 5 °C·min−1; and T37 min, 260 °C.

Accession Code: 4HOV

Supplementary Material

Table 2.

X-ray data collection and refinement statistics for N246A:Mn2+ complex

| Data set | High resolution | Mn K-edge |

|---|---|---|

| Data collectiona | ||

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.97530 | 1.75858 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 46.7 – 2.2 | 51.1 – 2.6 |

| (2.32 – 2.20) | (2.74 – 2.60) | |

| Space group | P3221 | P3221 |

| Unit cell dimensions (Å) |

a = b = 133.0, c = 159.5 |

a = b = 133.1, c = 159.7 |

| Unique reflections | 83068 | 50809 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.8 (99.8) | 99.9 (99.9) |

| Average I/σI | 8.4 (1.9) | 8.3 (1.8) |

| Redundancy | 7.0 (7.1) | 7.0 (7.0) |

| Rmerge | 0.065 (0.376) | 0.075 (0.430) |

| Wilson B (Å2) | 38.2 | 56.4 |

| Refinement | ||

| Rwork (Rfree) | 0.170(0.196) | -- |

| B-factors (Å2) | ||

| All atoms | 36.2 | -- |

| Protein | 35.5 | -- |

| Heme | 26.9 | -- |

| Water | 43.2 | -- |

| r.m.s.d. bond length (Å) | 0.010 | -- |

| Ramachandran plot residues: | ||

| In most-favourable region | 91.5 | -- |

| In disallowed regions | 0.0 | -- |

| PDB accession code | 4HOV | -- |

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a Genome Canada Large-Scale Research Project (to L. D. E. and J. K.), a Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada Strategic Network (LignoWorks) (to L. D. E. and J. K.) and an NSERC Discovery grants (to M. E. P. M.). Portions of this research were carried out at the Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource, a Directorate of SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory and an Office of Science User Facility operated for the U.S. Department of Energy Office of Science by Stanford University. The SSRL Structural Molecular Biology Program is supported by the DOE Office of Biological and Environmental Research, and by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of General Medical Sciences (including P41GM103393) and the National Center for Research Resources (P41RR001209). The contents of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIGMS, NCRR or NIH.

Footnotes

Supporting Information: This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org

REFERENCES

- 1.Stocker M. Biofuels and biomass-to-liquid fuels in the biorefinery: catalytic conversion of lignocellulosic biomass using porous materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2008;47:9200–9211. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zakzeski J, Bruijnincx PC, Jongerius AL, Weckhuysen BM. The catalytic valorization of lignin for the production of renewable chemicals. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:3552–3599. doi: 10.1021/cr900354u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tien M, Kirk TK. Lignin-degrading enzyme from the hymenomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium burds. Science. 1983;221:661–663. doi: 10.1126/science.221.4611.661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Glenn JK, Gold MH. Purification and characterization of an extracellular Mn(II)-dependent peroxidase from the lignin-degrading basidiomycete, Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 1985;242:329–341. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(85)90217-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leonowicz A, Matuszewska A, Luterek J, Ziegenhagen D, Wojtas-Wasilewska M, Cho NS, Hofrichter M, Rogalski J. Biodegradation of lignin by white rot fungi. Fungal. Genet. Biol. 1999;27:175–185. doi: 10.1006/fgbi.1999.1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fernandez-Fueyo E, Ruiz-Duenas FJ, Ferreira P, Floudas D, Hibbett DS, Canessa P, Larrondo LF, James TY, Seelenfreund D, Lobos S, Polanco R, Tello M., Honda, Y., Watanabe T, Watanabe T, San RJ, Kubicek CP, Schmoll M, Gaskell J, Hammel KE, St John FJ, Vanden Wymelenberg A, Sabat G, Splinter Bondurant S, Syed K, Yadav JS, Doddapaneni H, Subramanian V, Lavin JL, Oguiza JA, Perez G, Pisabarro AG, Ramirez L, Santoyo F, Master E, Coutinho PM, Henrissat B, Lombard V, Magnuson JK, Kues U, Hori C, Igarashi K, Samejima M, Held BW, Barry KW, Labutti KM, Lapidus A, Lindquist EA, Lucas SM, Riley R, Salamov AA, Hoffmeister D, Schwenk D, Hadar Y, Yarden O, de Vries RP, Wiebenga A, Stenlid J, Eastwood D, Grigoriev IV, Berka RM, Blanchette RA, Kersten P, Martinez AT, Vicuna R, Cullen D. Comparative genomics of Ceriporiopsis subvermispora and Phanerochaete chrysosporium provide insight into selective ligninolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012;109:5458–5463. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119912109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jensen KA, Bao W, Kawai S, Srebotnik E, Hammel KE. Manganese-dependent cleavage of nonphenolic lignin structures by Ceriporiopsis subvermispora in the absence of lignin peroxidase. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1996;62:3679–3686. doi: 10.1128/aem.62.10.3679-3686.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conesa A, Punt PJ, van den Hondel CA. Fungal peroxidases: molecular aspects and applications. J. Biotechnol. 2002;93:143–158. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(01)00394-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramachandra M, Crawford DL, Hertel G. Characterization of an extracellular lignin peroxidase of the lignocellulolytic actinomycete Streptomyces viridosporus. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1988;54:3057–3063. doi: 10.1128/aem.54.12.3057-3063.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bugg TD, Ahmad M, Hardiman EM, Rahmanpour R. Pathways for degradation of lignin in bacteria and fungi. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011;28:1883–1896. doi: 10.1039/c1np00042j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deangelis KM, D’Haeseleer P, Chivian D, Fortney JL, Khudyakov J, Simmons B, Woo H, Arkin AP, Davenport KW, Goodwin L, Chen A, Ivanova N, Kyrpides NC, Mavromatis K, Woyke T, Hazen TC. Complete genome sequence of “Enterobacter lignolyticus” SCF1. Stand. Genomic. Sci. 2011;5:69–85. doi: 10.4056/sigs.2104875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmad M, Roberts JN, Hardiman EM, Singh R, Eltis LD, Bugg TD. Identification of DypB from Rhodococcus jostii RHA1 as a lignin peroxidase. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5096–5107. doi: 10.1021/bi101892z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown ME, Walker MC, Nakashige TG, Iavarone AT, Chang MC. Discovery and characterization of heme enzymes from unsequenced bacteria: application to microbial lignin degradation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:18006–18009. doi: 10.1021/ja203972q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown ME, Barros T, Chang MC. Identification and characterization of a multifunctional dye peroxidase from a lignin-reactive bacterium. A. C. S. Chem. Biol. 2012 doi: 10.1021/cb300383y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roberts JN, Singh R, Grigg JC, Murphy ME, Bugg TD, Eltis LD. Characterization of dye-decolorizing peroxidases from Rhodococcus jostii RHA1. Biochemistry. 2011;50:5108–5119. doi: 10.1021/bi200427h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sugano Y, Nakano R, Sasaki K, Shoda M. Efficient heterologous expression in Aspergillus oryzae of a unique dye-decolorizing peroxidase, DyP, of Geotrichum candidum Dec 1. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000;66:1754–1758. doi: 10.1128/aem.66.4.1754-1758.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugano Y. DyP-type peroxidases comprise a novel heme peroxidase family. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2009;66:1387–1403. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8651-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liers C, Bobeth C, Pecyna M, Ullrich R, Hofrichter M. DyP-like peroxidases of the jelly fungus Auricularia auricula-judae oxidize nonphenolic lignin model compounds and high-redox potential dyes. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2010;85:1869–1879. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheibner M, Hulsdau B, Zelena K, Nimtz M, de Boer L, Berger RG, Zorn H. Novel peroxidases of Marasmius scorodonius degrade beta-carotene. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2008;77:1241–1250. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1261-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goblirsch B, Kurker RC, Streit BR, Wilmot CM, DuBois JL. Chlorite dismutases, DyPs, and EfeB: 3 microbial heme enzyme families comprise the CDE structural superfamily. J. Mol. Biol. 2011;408:379–398. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh R, Grigg JC, Armstrong Z, Murphy ME, Eltis LD. Distal heme pocket residues of B-type dye-decolorizing peroxidase: arginine but not aspartate is essential for peroxidase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2012;287:10623–10630. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.332171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varadarajan R, Zewert TE, Gray HB, Boxer SG. Effects of buried ionizable amino acids on the reduction potential of recombinant myoglobin. Science. 1989;243:69–72. doi: 10.1126/science.2563171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunford HB. Heme peroxidases. John Wiley; New York: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sundaramoorthy M, Gold MH, Poulos TL. Ultrahigh (0.93A) resolution structure of manganese peroxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium: implications for the catalytic mechanism. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2010;104:683–690. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2010.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Youngs HL, Sollewijn Gelpke MD, Li D, Sundaramoorthy M, Gold MH. The role of Glu39 in Mn(II) binding and oxidation by manganese peroxidase from Phanerochaete chrysoporium. Biochemistry. 2001;40:2243–2250. doi: 10.1021/bi002104s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yeung BK, Wang X, Sigman JA, Petillo PA, Lu Y. Construction and characterization of a manganese-binding site in cytochrome c peroxidase: towards a novel manganese peroxidase. Chem. Biol. 1997;4:215–221. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90291-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gengenbach A, Syn S, Wang X, Lu Y. Redesign of cytochrome c peroxidase into a manganese peroxidase: role of tryptophans in peroxidase activity. Biochemistry. 1999;38:11425–11432. doi: 10.1021/bi990666+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mörck R, Yoshida H, Kringstad Knut P. Fractionation of kraft lignin by successive extraction with organic solvents. Holzforschung. 1986;40:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hofrichter M, Lundell T, Hatakka A. Conversion of milled pine wood by manganese peroxidase from Phlebia radiata. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2001;67:4588–4593. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.10.4588-4593.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tuor U, Wariishi H, Schoemaker HE, Gold MH. Oxidation of phenolic arylglycerol beta-aryl ether lignin model compounds by manganese peroxidase from Phanerochaete chrysosporium: oxidative cleavage of an alpha-carbonyl model compound. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4986–4995. doi: 10.1021/bi00136a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villar JC, Caperos A, García-Ochoa F. Oxidation of hardwood kraftlignin to phenolic derivatives with oxygen as oxidant. Wood Sci. Technol. 2001;35:245–255. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bujanovic B, Ralph S, Reiner R, Hirth K, Atalla R. Polyoxometalates in oxidative delignification of chemical pulps: effect on lignin. Materials. 2010;3:1888–1903. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kawai S, Asukai M, Ohya N, Okita K, Ito T, Ohashi H. Degradation of a non-phenolic β-O-4 substructure and of polymeric lignin model compounds by laccase of Coriolus versicolor in the presence of 1-hydroxybenzotriazole. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 1999;170:51–57. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wariishi H, Valli K, Gold MH. Manganese(II) oxidation by manganese peroxidase from the basidiomycete Phanerochaete chrysosporium - kinetic mechanism and role of chelators. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:23688–23695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cornish-Bowden A. Analysis of enzyme kinetic data. Oxford University Press; Oxford ; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Battye TG, Kontogiannis L, Johnson O, Powell HR, Leslie AG. iMOSFLM: a new graphical interface for diffraction-image processing with MOSFLM. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:271–281. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910048675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leslie AG. The integration of macromolecular diffraction data. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:48–57. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905039107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Evans P. Scaling and assessment of data quality. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2006;62:72–82. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905036693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of macromolecular structures by the maximum-likelihood method. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1997;53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.CCP4 The CCP4 suite: programs for protein crystallography. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 1994;50:760–763. doi: 10.1107/S0907444994003112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta. Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.