Abstract

A wide range of musculoskeletal tumours and tumour-like conditions may be encountered when patients undergo radiological examinations. Some malignant musculoskeletal lesions may mimic benign tumours at imaging, being confused with benign cystic lesions or haematomas. Also, inappropriately selected magnetic resonance (MR) image sequences or computed tomography (CT) display windows can lead to misdiagnosis. Many orthopaedic surgeons interpret radiological images themselves, and therefore need to be as aware of these issues as radiologists are. This review describes and illustrates a number of such errors that commonly occur, and provides suggestions for avoiding these pitfalls.

At various points in the medical timeline of a patient with known or suspected cancer—ranging from initial detection of tumour to post-treatment follow-up—radiological examinations may depict a lesion in the musculoskeletal system. Some such lesions may be metastases, but others represent benign or other malignant tumours, or tumour-like conditions. If a suspicious lesion is automatically assumed to represent a metastasis, those patients in whom the lesion is benign may be overtreated, and those in whom the lesion actually represents an unsuspected second type of cancer probably will not receive appropriate treatment for that second cancer. As in all of oncological imaging, accurate characterisation of lesions is essential for proper clinical management. A prior review [1] described pitfalls in MR image interpretation that resulted in referral to an orthopaedic oncology clinic for suspected malignancy. In this second part of a different two-part review [2], we present several interpretive pitfalls that we have commonly encountered in the musculoskeletal system during radiographic, CT, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or positron emission tomography (PET)/CT evaluation of patients with known or suspected cancer, in an effort to increase awareness of these readily correctible issues. These pitfalls have been selected based on the authors’ collective experience working in a dedicated cancer centre.

The focus of this part is on malignant tumours that may mimic benign lesions, and on technical issues at imaging that can result in misdiagnosis.

Malignant tumours that may mimic benign lesions

Malignant soft tissue tumour mimicking a cystic lesion

Those malignant soft tissue tumours that are rich in myxoid or chondroid elements have a very high water content, which results in prolonged T1 and T2 relaxation times similar to those of simple fluid at MRI [3]. As a result, myxoid sarcomas (such as myxoid liposarcoma [4] or myxofibrosarcoma) or chondrosarcoma (such as extraskeletal chondrosarcoma) can be mistaken for a benign cystic lesion, due to their diffuse fluid-like signal intensity at MRI (Figs. 1a and 2a). Administration of intravenous contrast plays an important role in distinguishing between solid and cystic lesions [5], as solid lesions show at least some enhancement (which can be homogenous or heterogeneous, and range from fine and lacy to nodular or diffuse) (Fig. 1b). Although only a thin rim of enhancement is seen in the periphery of an uncomplicated cyst, high-grade chondrosarcoma may show only rim enhancement [6], and thus potentially be confused for a cyst (Fig. 2b) or postoperative fluid collection. Although contrast enhancement is not specific in distinguishing between benign and malignant tumours, it is still useful in characterising tumours, suggesting the most viable portion of a lesion to biopsy, assessing therapeutic response, and monitoring for local tumour recurrence.

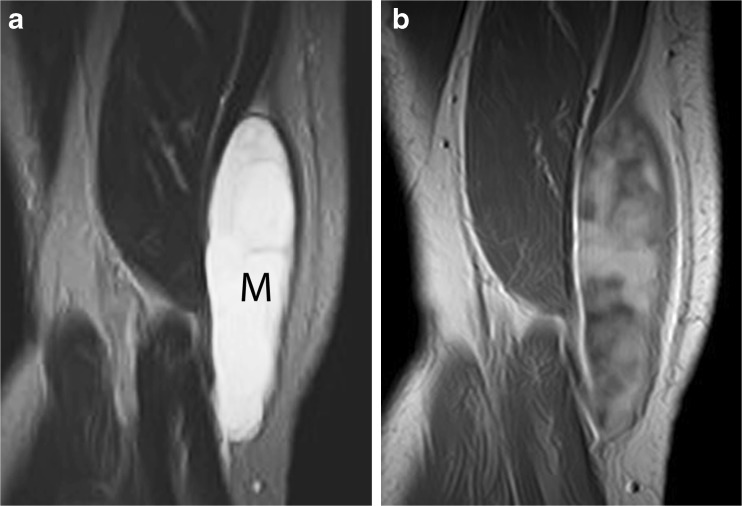

Fig. 1.

Myxoid liposarcoma simulating a cyst on nonenhanced MR images. a Coronal T2-weighted MR image shows a mass (M) in the medial right thigh with very high, fluid-like signal intensity and a few fine septations, mimicking a septated cystic lesion. However, b coronal T1-weighted contrast-enhanced MR image demonstrates extensive, heterogeneous enhancement throughout the mass, proving its solid nature

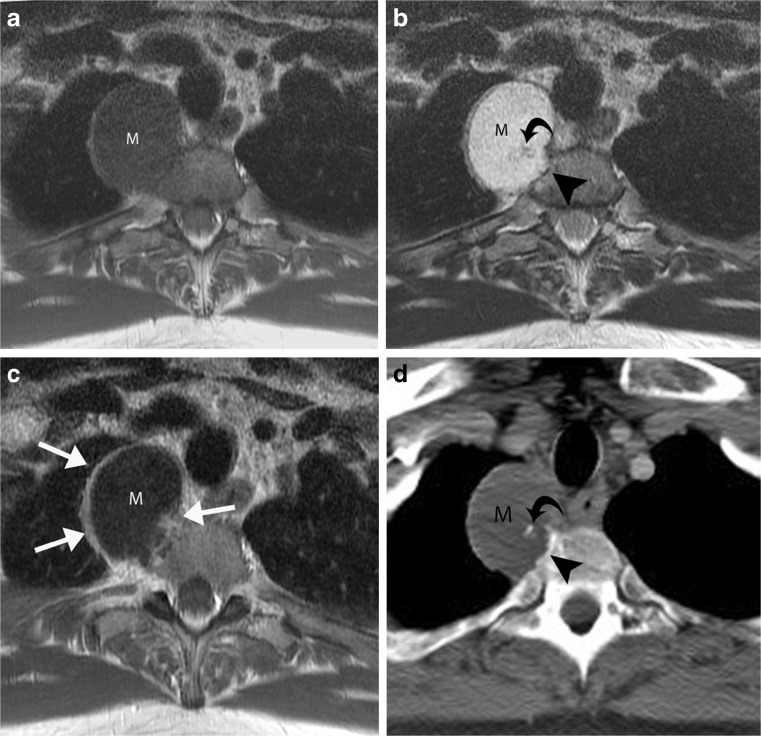

Fig. 2.

Extraskeletal chondrosarcoma mimicking a paraspinal cyst. Axial a T1-weighted MR image and b T2-weighted MR image show a right paraspinal mass (M) at T1 level, with diffuse fluid-like signal intensity, slightly eroding the vertebral body (arrowhead). c Axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted MR image shows predominantly peripheral enhancement as well as a small focus of nodular peripheral enhancement (arrows). This pattern of enhancement and the erosion of vertebral body are consistent with the biopsy-proven diagnosis of extraskeletal chondrosarcoma. d Axial contrast-enhanced CT image shows that mass (M) is of slightly lower attenuation than muscle, corresponding to the high water content of chondroid matrix. Adjacent to the bone erosion (arrowhead), a tiny calcification (curved arrow) is noted within the mass, another clue that the mass is solid rather than a cyst

Soft tissue sarcoma mimicking haematoma after trauma

Soft tissue sarcomas often contain regions of haemorrhage, and may be noticed by a patient only after trauma draws attention to the mass. Such pre-existing tumours may be misinterpreted as haematomas by the radiologist and referring physician (Fig. 3). It is prudent practice to recommend imaging follow-up after one to two months to document resolution of any mass presumed to have resulted from trauma. Alternatively, pre-contrast and post-contrast computed tomography (CT) or MRI could be obtained to determine whether any portion of the mass enhances—which would strongly suggest that the mass represents a solid tumour.

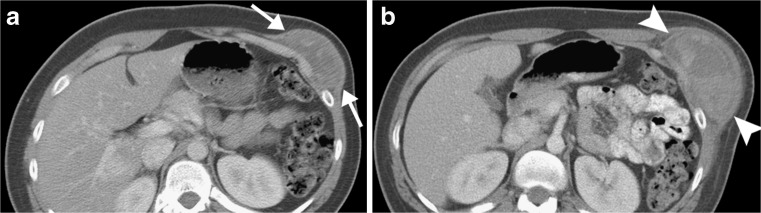

Fig. 3.

Synovial sarcoma, misdiagnosed as haematoma after traumatic event. a Axial contrast-enhanced CT image obtained after trauma to chest wall shows a heterogeneous mass (arrows) that was interpreted at an outside facility as representing a haematoma. b Follow-up CT image obtained 9 months later shows interval enlargement of the mass (arrowheads), which was shown by biopsy to represent synovial sarcoma

Tail-like extensions of myxofibrosarcoma misinterpreted as oedema or postoperative change

Myxofibrosarcoma is one of the most common fibrous sarcomas in elderly patients, often occurring in the extremities and limb girdle [7–9]. Myxofibrosarcoma often spreads along fascial planes for long distances from the primary tumour mass in a curvilinear, tail-like configuration. Failure to recognise that these “tails” actually represent tumour may result in incomplete surgical resection, thus predisposing to local tumour recurrence. Due to its high water content, the myxoid component of myxofibrosarcoma is very bright on fluid-sensitive MR sequences (T2-weighted and STIR), mimicking fluid or oedema [8, 9] (Fig. 4a). Use of intravenous contrast (gadolinium) is very helpful in distinguishing between tails of tumour and oedema/fluid: Tumour will show avid, sharply defined enhancement (Fig. 4b), whereas oedema generally enhances to a lesser degree and appears less well defined. Thus, when staging myxofibrosarcoma or assessing for local myxofibrosarcoma recurrence, all curvilinear enhancing structures at MRI, in addition to the primary mass itself, should be reported as tumour by the radiologist so that the surgeon can include all in the planned resection.

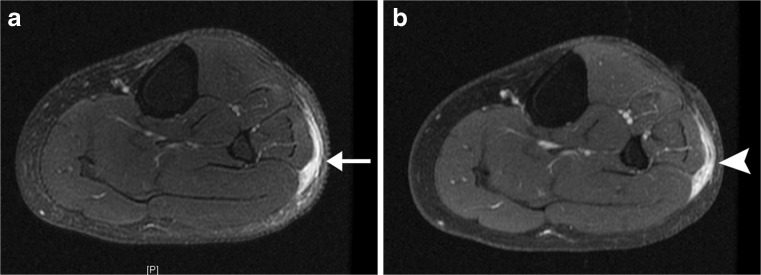

Fig. 4.

Tails of myxofibrosarcoma due to recurrent tumour, which could be mistaken for postoperative changes. a Axial fat-suppressed T2-weighted MR image demonstrates a curvilinear “tail” of very high T2 signal (arrow) in subcutaneous tissues of lateral calf within the surgical resection bed, which could be misinterpreted as postoperative oedema or fluid. However, b axial post-gadolinium fat-suppressed T1-weighted MR image shows that the tail markedly enhances (arrowhead), confirming that it represents tumour rather than fluid

Liposarcoma without substantial uptake at PET

Liposarcomas demonstrate variable fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avidity, depending on their particular histological subtype. Poorly differentiated liposarcomas are usually markedly FDG-avid and are readily evident on FDG positron emission tomography (PET) scans, whereas well-differentiated liposarcomas are unlikely to show appreciable FDG avidity. Myxoid and pleomorphic liposarcomas may or may not show increased activity at FDG PET [10] (Fig. 5).

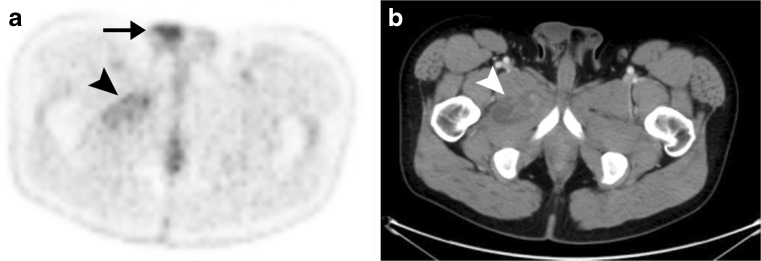

Fig. 5.

Myxoid liposarcoma with only minimal FDG avidity. a Axial FDG PET scan through the lower pelvis demonstrates only minimal FDG avidity in the known myxoid liposarcoma (arrowhead). Such minimal activity should not be misinterpreted as postoperative change, inflammation, or some other benign process. Physiological FDG avidity is noted in the right testis (arrow). b Axial CT at the same level demonstrates the myxoid liposarcoma as a mixed-attenuation mass (arrowhead) with regions of attenuation lower than muscle representing the myxoid component of the tumour

Non-FDG–avid osseous metastases

Osseous metastases are often apparent on FDG PET scans even before they are visible at CT, because bone metastases typically develop within the bone marrow and only subsequently destroy surrounding trabecula and/or elicit a sclerotic response from host bone. Also, some marrow metastases may be occult on FDG PET, due to the nature of the particular non-FDG-avid primary malignancy and/or the small size of the metastasis. Primary malignancies that often are non-FDG-avid include lobular breast cancer, prostate carcinoma, and hepatocellular carcinoma [11, 12] (Fig. 6).

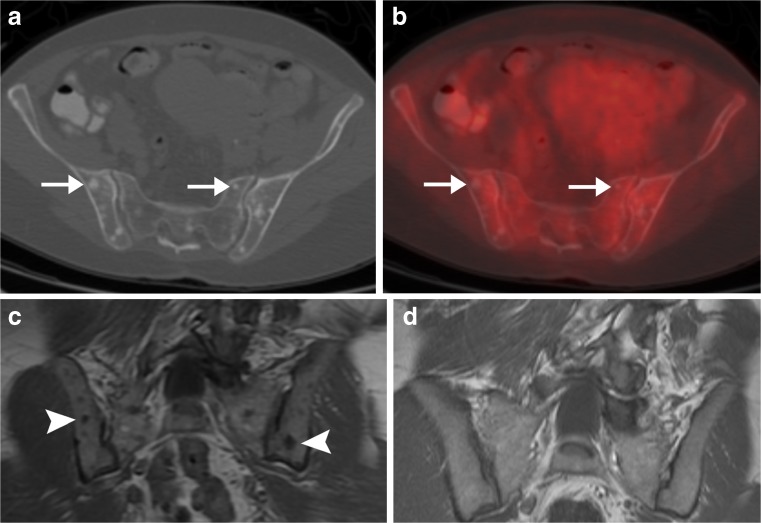

Fig. 6.

Osseous metastases without FDG avidity in woman with newly diagnosed lobular breast cancer. a Axial CT and b hybrid FDG PET/CT scans demonstrate multiple small blastic osseous lesions (arrows) that are not FDG-avid. Such findings could be present in non-FDG-avid osseous metastases or in multiple bone islands (e.g., osteopoikilosis). c Coronal T1-weighted MR image demonstrated that the osseous lesions (arrowheads) are new since d a prior MRI that had been performed 3 years earlier for back pain, and thus the lesions are consistent with osseous metastases

Technical issues

Fatty marrow simulating sacral metastasis on bone windows

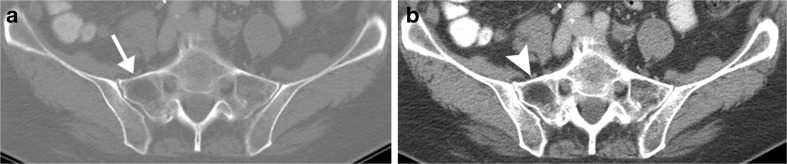

Focal regions of osteoporosis commonly occur in the sacrum, either unilaterally or bilaterally. Particularly when unilateral, such regions can be mistaken for lytic metastases at CT when viewed only on bone window settings (Fig. 7a); the fatty nature of the region is more readily evident on soft tissue window settings, on which the region in question will appear as dark as nearby fat (Fig. 7b). Measurement of the actual CT attenuation of the suspected lesion (with the region-of-interest tool) will yield values in the range of −50 to −100 Hounsfield units, proving that the lesion actually represents normal fat.

Fig. 7.

Asymmetric osteopenia, misinterpreted as a lytic lesion when viewed at CT bone window settings. Axial CT scans of pelvis displayed at a bone and b soft tissue window settings. The asymmetric region of low attenuation in the right sacral ala (arrow) initially was suspected to represent metastasis of patient’s known bladder cancer. However, visual evaluation of the region on b soft tissue windows suggested the presence of fat throughout that region (arrowhead), which was proven by region-of-interest measurement (−52 Hounsfield units; normal fat = −50 to −100 HU)

Use of proton density MR images for evaluation of marrow

Many facilities routinely use proton density MR sequences because of their high sensitivity for evaluating musculoskeletal anatomy, particularly menisci, labra and cartilage [13]. However, a marrow-replacing lesion may demonstrate signal intensity similar to that of surrounding normal marrow on such images, limiting their identification and/or accurate characterisation (Fig. 8a). T1-weighted sequences should always be obtained to evaluate the marrow if tumour is a diagnostic consideration, as a marrow-replacing lesion will show low signal intensity (similar to that of muscle) against a background of high-signal fatty marrow [14] (Fig. 8b).

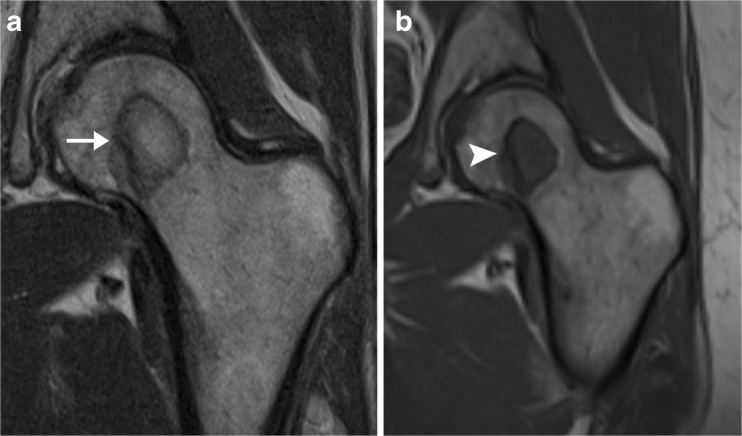

Fig. 8.

Femoral lesion in patient with breast cancer, suboptimally evaluated on proton density images. a Coronal proton density MR image of the left hip demonstrates a low-signal circle in the left femoral head, surrounding a region that has signal similar to that of surrounding marrow (arrow). The findings could be consistent with avascular necrosis. b Corresponding coronal T- weighted MR image clearly shows that the lesion has signal intensity similar to that of muscle (arrowhead), indicating that it represents a marrow-replacing lesion. Biopsy results confirmed metastatic adenocarcinoma of the breast

In conclusion, the various pitfalls described in this review can be avoided through careful evaluation of imaging features, correlation with clinical information, and considering both benign and malignant processes when formulating the differential diagnosis. Caution is advised when making the diagnosis of a benign cystic lesion or haematoma, as similar radiological findings may be encountered in some malignant processes. Lesions that are non-FDG-avid at PET scanning ought not be assumed to be benign, as various malignant processes may show little activity at PET. In addition, some basic technical issues in image acquisition and display need to be assessed to ensure that the image evaluation was performed optimally and appropriately. Gadolinium should be ordered in evaluation of potential musculoskeletal tumours to avoid misdiagnosis, unless a contraindication to its use is present.

References

- 1.Stacy GS, Dixon LB. Pitfalls in MR image interpretation prompting referrals to an orthopedic oncology clinic. RadioGraphics. 2007;27:805–828. doi: 10.1148/rg.273065031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ulaner G, Hwang S, Lefkowitz RA, Landa J, Panicek DM (in press) Musculoskeletal tumors and tumour-like conditions: common and avoidable pitfalls at imaging in patients with known or suspected cancer. PART A: benign conditions that may mimic malignancy. Int Orthop [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 3.Wu JS, Hochman MG. Soft-tissue tumors and tumorlike lesions: a systematic imaging approach. Radiology. 2009;253:297–316. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2532081199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sung M-S, Kang HS, Suh JS, Lee JH, Park JM, Kim JY, Lee HG. Myxoid liposarcoma: appearance at MR imaging with histologic correlation. RadioGraphics. 2000;20:1007–1019. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.4.g00jl021007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.May DA, Good RB, Smith DK, Parsons TW. MR imaging of musculoskeletal tumors and tumor mimickers with intravenous gadolinium: experience with 242 patients. Skeletal Radiol. 1997;26:2–15. doi: 10.1007/s002560050183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yoo HJ, Hong SH, Choi J-Y, Moon KC, Kim H-S, Choi J-A, Kang HS. Differentiating high-grade from low-grade chondrosarcoma with MR imaging. Eur Radiol. 2009;19:3008–3014. doi: 10.1007/s00330-009-1493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huang H-Y, Lal P, Qin J, Antonescu CR. Low-grade myxofibrosarcoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of 49 cases treated at a single institution with simultaneous assessment of the efficacy of 3-tier and 4-tier grading systems. Human Pathol. 2004;5:612–621. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2004.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waters B, Panicek DM, Lefkowitz RA, Antonescu CR, Healey JH, Athanasian EA, Brennan MF. Low-grade myxofibrosarcoma: CT and MRI patterns in recurrent disease. AJR. 2007;188:W193–W198. doi: 10.2214/AJR.05.1130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaya M, Wada T, Nagoya S, Sasaki M, Matsumura T, Yamaguchi T, Hasegawa T, Yamashita T. MRI and histological evaluation of the infiltrative growth pattern of myxofibrosarcoma. Skeletal Radiol. 2008;37:1085–1090. doi: 10.1007/s00256-008-0542-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schwarzbach MH, Dimitrakopoulou-Strauss A, Mechtersheimer G, Hinz U, Willeke F, Cardona S, Attigah N, Strauss LG, Herfarth C, Lehnert T. Assessment of soft tissue lesions suspicious for liposarcoma by F18-deoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET) Anticancer Res. 2001;21:3609–3614. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosen EL, Eubank WB, Mankoff DA. FDG PET, PET/CT, and breast cancer imaging. Radiographics. 2007;27(Suppl 1):S215–S229. doi: 10.1148/rg.27si075517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fletcher JW, Djulbegovic B, Soares HP, Siegel BA, Lowe VJ, Lyman GH, Coleman RE, Wahl R, Paschold JC, Avril N, Einhorn LH, Suh WW, Samson D, Delbeke D, Gorman M, Shields AF. Recommendations on the use of 18F-FDG PET in oncology. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:480–508. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.047787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonin AH, Pensy RA, Mulligan ME, Hatem S. Grading articular cartilage of the knee using fast spin-echo proton density–weighted MR imaging without fat suppression. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1159–1166. doi: 10.2214/ajr.179.5.1791159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richardson ML, Amparo EG, Gillespy T, 3rd, Helms CA, Demas BE, Genant HK. Theoretical considerations for optimizing intensity differences between primary musculoskeletal tumors and normal tissue with spin-echo magnetic resonance imaging. Invest Radiol. 1985;20:492–497. doi: 10.1097/00004424-198508000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]