Abstract

According to the author, the Oeuvres, edited as early as 1575 from the first opuscules (little works), produced, even at that time, a comprehensive synthesis of the surgical art by assembling not only the experiences and opinions concerning the surgery of his period as a whole but also contributing essential details about the surgical instrumentation of the sixteenth century. Ambroise Paré contributed much to this thanks to his innate sense of the operative art from which he drew largely from experience gained during his military campaigns.

The earliest surgical operations were probably circumcision (removal of the foreskin of the penis) and trepanation (making a hole in the skull, for release of pressure and/or spirits). Primitive surgical instruments consisted of flint or obsidian knives and saws. Stone Age skulls from around the world have been found with holes from trepanning. Primitive people used knives to remove fingers, and the ancient Mesopotamian cultures practised surgery to some degree. Small copper Sumerian knives of about 3000 B.C. are believed to be surgical instruments. The Babylonian Code of Hammurabi of about 1700 B.C. mentions bronze lancets—sharp-pointed two-edged instruments used to make small incisions (Figs. 1, 2 and 3). The Code of Hammurabi, however, provided harsh penalties for poor treatment outcomes, so surgery was practised only sparingly. Likewise, ancient Chinese and Japanese cultures were opposed to cutting into the human body, so surgical instruments were used very little.

Fig. 1.

Portrait of Ambroise Paré: in the upper right corner is the famous bec de Corbin used for ligature

Fig. 2.

Babylonia was an ancient cultural region in central-southern Mesopotamia (present-day Iraq), with Babylon as its capital. Babylonia emerged as a major power when Hammurabi (1792–1750 B.C. or fl ca. 1696–1654 B.C., short chronology) created an empire out of the territories of the former Akkadian Empire

Fig. 3.

Seal of a Babylonian Azu with reverence to the gods, a self-portrait and depictions of bronze knives, cups and needles. Translation: O Edinmagi, servant of the god Girra, who helps mothers in childhood, Ur-Lugaledina the physician is your servant. (From A. Leix, Medicine and the intellectual life of Babylonia. CIBA Symp 2:663–674, 1940)

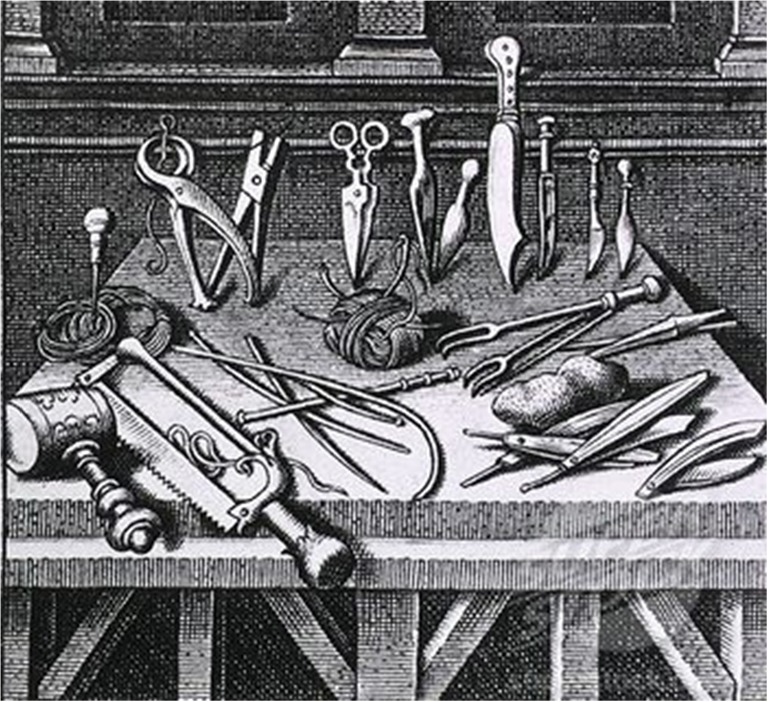

Surgeons of the late Middle Ages were not as ineffective as some modern medical historians would lead us to believe. The constant warfare of the age demanded skilled men who could dress wounds of soldiers, and almost all surgeons of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries had seen military action. On these expeditions the surgeons gained knowledge and experience in treating all forms of wounds and injuries. They served as physicians and apothecaries as well as surgeons. They experimented with various kinds of powders, plasters and fomentations for closing wounds. They invented tools for extracting arrows and bolts (Figs. 4 and 5); they learned techniques for healing fractured limbs and amputating diseased ones. Some successes were had by these surgeons, often brought about by quite ingenious means. On the battlefield, crossbows were used to extract crossbow bolts, and new tools were fashioned to perform difficult surgical operations. Indeed, at the Battle of Shrewsbury, fought in 1403, the English military surgeon John Bradmore made a new surgical apparatus to extract an arrow from the cheek of Prince Henry, later to be crowned Henry V (Fig. 6).

Fig. 4.

Surgical tools around the fifteenth century

Fig. 5.

Tools for extracting arrows and bolts

Fig. 6.

On the battlefield, crossbows were used to extract crossbow bolts. At the Battle of Shrewsbury, fought in 1403, the English military surgeon John Bradmore made a new surgical apparatus to extract an arrow from the cheek of Prince Henry, later to be crowned Henry V

Gunpowder weaponry added a new destructive dimension to the late Middle Ages. Already available in limited quantities throughout Europe in the early fourteenth century, guns began taking on a larger role in warfare as the century progressed. They appeared on the battlefield of Crecy in 1346 used by Edward III ostensibly to create noise and panic. Later that year they also appeared at the English Siege of Calais. By 1377 guns had successfully been used to bring down the walls of a fortification when Philip the Bold, Duke of Burgundy, conquered the fortress of Odruik; and in 1382 they played a significant role in a battlefield victory when the Ghentenaar forces defeated the Brugeois troops at the Battle of Bevershoutsveld fought outside the town of Bruges. By 1400 gunpowder weaponry appeared in nearly every engagement of the war. Large guns were used in sieges and smaller weapons were used in battle and on ships. Eventually handheld gunpowder weapons were made, and these began to be used by the infantry as a more powerful, although less accurate, replacement for archery. By the 1470s infantry units equipped with handheld guns often faced enemy infantry units also equipped with handheld guns.

This interest in gunpowder weaponry increased as the war progressed. As guns became more numerous and more accurate and powerful, more soldiers were killed and wounded. Small guns fired metal balls, usually made of lead or iron, and larger guns fired stone balls, especially fashioned for that purpose. Gunshot wounds from both these weapons could be and were often fatal; metal balls could pierce the skin, while larger stone balls could kill on impact with the body or by splintering into fragments which would then enter the torso or limbs (Figs. 7, 8, 9, and 10).

Fig. 7.

Textbook of Ambroise Paré on the technique of treating war wounds

Fig. 8.

Simple forceps to remove bullets designed by Ambroise Paré

Fig. 9.

Very sophisticated forceps to remove bullets designed by Ambroise Paré; one can remark the similar design as endoscopic tools today

Fig. 10.

One can remark the description given by Ambroise Paré for the use of two instruments for the first time: one forceps is used to open the wound and the other is used to remove the bullet

The trepanning technique was used for many indications before the fifteenth century, and the use of trepanning for military treatment of skull fractures clearly increased with the introduction of guns (Figs. 11, 12, 13, and 14). As guns became more numerous, more accurate and powerful, more soldiers were wounded in the head and treatment of head wounds and trepan use were more frequent. Tools for head surgery and trepanning were improved by Ambroise Paré. In his treatises on surgery, Paré also described “trepans or round saws for cutting out a circular piece of bone with a sharp-pointed nail in the centre projecting beyond the teeth” and another trepan with a transverse handle. Furthermore, Ambroise Paré with appropriate technology sought to ensure safe use, i.e. that the conceived instrument be the least harmful possible even in less skilful or unpracticed hands (Figs. 15 and 16). An example is his trepan à Chaperon with a protective lid. He also improved safety by moving from a two-point bearing (bipod trepan, Gersdorff, Fig. 17) to a three-point bearing trepan (Fig. 18). This instrument was used much in the same way as a modern hand drill—held in one hand and cranked with the other. But it was extremely heavy and cumbersome, and therefore did not become popular among the surgeons of the time [1–10].

Fig. 11.

Trepanation in the fifth century

Fig. 12.

Tools for head wounds

Fig. 13.

Trepanation ceremony (Hieronymus Bosch, The Cure of Folly, from the Prado, Madrid)

Fig. 14.

Trepanation ceremony (Hieronymus Bosch)

Fig. 15.

Ambroise Paré with appropriate technology conceived that an instrument be the least harmful possible even in less skilful or unpracticed hands. An example is his trepan à Chaperon with a protective lid

Fig. 16.

Ambroise Paré’s personal trepan, Laval museum France

Fig. 17.

Gersdorff trepan with two points

Fig. 18.

Ambroise Paré’s trepan with three points

References

- 1.Brun R (1969) Le livre français illustré de la Renaissance. Picard, Paris

- 2.Janet DOE (1976) A. Paré, a bibliography (1545–1940) (avec addenda) Amsterdam, Gérard Th. van Heusden, Philo

- 3.Dumaitre P (1986) Ambroise Paré, chirurgien de 4 rois de France. Paris, Perrin, Fondation Singer-Polignac, 2nd edn, 1990

- 4.Martin HG, Chartier R (sous la direction de) (1982) Histoire de l’édition française. In: Le livre humaniste—Le livre et les propagandes religieuses, vol II. Paris, Promodis

- 5.Huard P, Grmek MD (1966) Mille ans de chirurgie en Occident: V-XVe siècles. Paris, Dacosta

- 6.Paré A (1598) Les oeuvres…, 5th edn. Paris, Buon

- 7.Malgaigne JF (1840–1841) Introduction to Paré A:. OEuvres complètes revues et collationnées sur toutes les éditions. Paris, Baillière

- 8.Ségal A (1987) L’instrumentation chirurgicale au Moyen-Age en Europe—Apport des manuscrits. Sem Hop Paris 46:3641–3651

- 9.Ségal A, Masson J, Pecker A (1985) Propos sur le commentaire du serment d’Hippocrate par Théodor Zwinger, médecin humaniste balois. Actes du colloque “Hippocrate et son héritage”. Lyon, Fondation Marcel Mérieux

- 10.Ségal A (1988) L'influence en médecine de la présentation tabulaire proposée par Pierre de la Ramée. XXXI congrès int. Hist. Méd. Bologne, 30 Août/4 Sept. 1988. In: Actes du XXXI congrès de Bologne. Bologna, Monduzzi Editore, pp 1003–1010