Abstract

Background

As adolescents grow, protective parental influences become less important and peer influences take precedence in adolescent’s initiation of smoking. It is unknown how and when this occurs. We sought to: prospectively estimate incidence rates of smoking initiation from late childhood through mid-adolescence, identify important risk and protective parental influences on smoking initiation, and examine their dynamic nature in order to identify key ages.

Methods

Longitudinal data from the National Survey of Parents and Youth of 8 nationally representative age cohorts (9–16 years) of never smokers in the U.S. were used (N=5705 dyads at baseline). Analysis involved a series of lagged logistic regression models using a cohort-sequential design.

Results

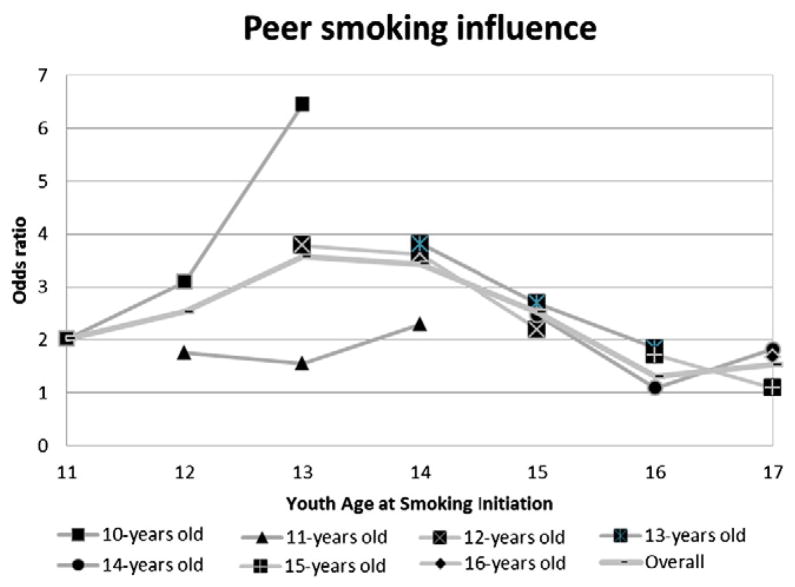

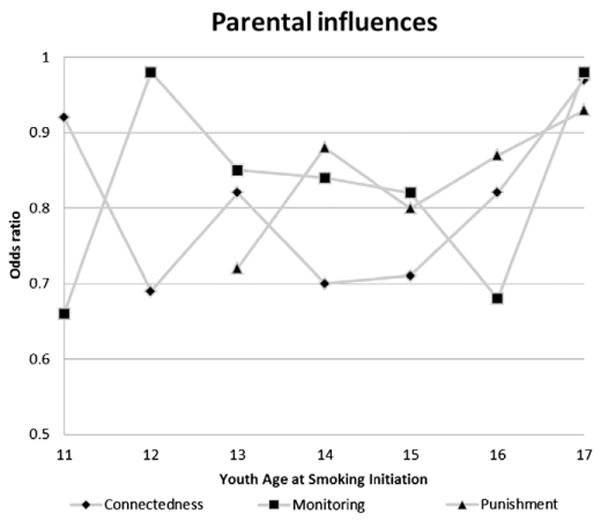

The mean sample cumulative incidence rates of tobacco use increased from 1.8% to 22.5% between the 9 and 16 years old age cohorts. Among risk factors, peer smoking was the most important across all ages; 11–15 year-olds who spent time with peers who smoked had 2 to 6.5 times higher odds of initiating smoking. Parent–youth connectedness significantly decreased the odds of smoking initiation by 14–37% in 11–14 year-olds; parental monitoring and punishment for smoking decreased the odds of smoking initiation risk by 36–59% in 10–15 year-olds, and by 15–28% in 12–14 year-olds, respectively.

Conclusions

Parental influences are important in protecting against smoking initiation across adolescence. At the same time, association with peers who smoke is a very strong risk factor. Our findings provide empirical evidence to suggest that in order to prevent youth from initiating smoking, parents should be actively involved in their adolescents’ lives and guard them against association with peers who smoke.

Keywords: Smoking prevention, Adolescent smoking, Adolescent parenting, Parent–child relationship

1. Introduction

Tobacco use is considered to be a pediatric disease because most adult tobacco dependence starts before the age of 18 years (American Academy of Pediatrics, 2009; Prokhorov et al., 2006). Although there has recently been a decline in teen smoking (Johnston, O’Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2011) we have not met the Healthy People 2020 objectives of reducing teen smoking initiation to 4.2% (U.S Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). This is troubling since early smoking initiation increases the likelihood of development of future tobacco related morbidity (U.S Department of Health and Human Services, 2010; United States Public Health Service Office of the Surgeon General, 2006). Thus, it is crucial to develop effective directed teen tobacco prevention interventions in order to avoid smoking initiation.

A large body of research indicates that both peers and parents play a crucial role in adolescent smoking initiation (Bricker, Peterson, Andersen et al., 2007; Bricker, Peterson, Sarason, Andersen, & Rajan, 2007; Bricker et al., 2009; Otten, Engels, van de Ven, & Bricker, 2007). Adolescence is characterized as a period of development when youth seek increased emotional security and social connectedness from their peers and hope to gain autonomy from their parents (Bauman, Carver, & Gleiter, 2001). Theory suggests that this need for adolescents to feel connected to their friends may explain why peer smoking is a strong risk factor for smoking initiation as youth may want to model their friend’s smoking behavior (Bernat, Erickson, Widome, Perry, & Forster, 2008; Hoffman, Monge, Chou, & Valente, 2007; Kim, Fleming, & Catalano, 2009; Simons-Morton, Chen, Abroms, & Haynie, 2004; Simons-Morton & Farhat, 2010). Theorists posit that adolescents with strong bonds to their parents are more likely to respect and follow parental rules and are less likely to initiate smoking (Krohn, Massey, Skinner, & Lauer, 1983; Matsueda & Heimer, 1987). These theories are supported by recent research which demonstrates the risk posed by peer smoking and the protective effect that high levels of parental influences such as monitoring and anti-tobacco rules have on preventing adolescent smoking initiation (Harakeh, Scholte, de Vries, & Engels, 2005; Simons-Morton, 2004; Simons-Morton & Farhat, 2010; Stanton et al., 2004).

Despite advances in our understanding of peer and parent influences on smoking initiation, there are many important gaps in the literature. While it is known that smoking initiation increases with age (Johnston et al., 2011; Kim et al., 2009; Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2011), it is unclear at what age peer smoking influences gain importance as a risk factor for smoking initiation and parent influences lose or retain their importance in protecting against initiation. Furthermore, it is unclear what other risk factors such as parental smoking and socioeconomic factors remain important in predicting smoking initiation. Without such knowledge, tobacco prevention researchers cannot determine age-appropriate interventions and parents may not know the best strategies for preventing tobacco use among their adolescents.

We sought to decrease these gaps by conducting a longitudinal examination of the National Survey of Parents and Youth (NSPY) to determine which parental influences remain important as youth grow during adolescence. The aim of this study was threefold: (1) to prospectively estimate incidence rates of smoking initiation from late childhood through mid-adolescence, (2) to identify important risk and protective parental influences for smoking initiation and the concomitant effect of peer influence, and (3) to examine the dynamic nature of the relationship between smoking initiation and risk and protective influences. Two developmental hypotheses were tested in this study: Hypothesis 1: Youth with consistently strong parental influences during adolescence will have lower rates of smoking initiation, and Hypothesis 2: Peer influence on smoking initiation increases during adolescence as parental influences decrease.

2. Materials and method

2.1. Sample and measures

2.1.1. Sample

Data are from the Restricted Use Files (RUF) of the NSPY, a longitudinal, nationally representative household-based survey of adolescent and parent dyads conducted in 90 locations across the US. A multistage sampling design was used to provide a representative cross-section of America’s 9–18 year-old youth. One parent was chosen from each eligible household. Detailed information about the sampling and methodology of the NSPY can be found elsewhere (Westat, 2003, 2006, Chaps. 1–7). Dyads were recruited for the study and interviewed during T1 and subsequently tracked and re-contacted for interview in yearly follow-up rounds. We analyzed data from rounds 1 (T1), 2 (T2), 3 (T3), and 4 (T4), collected from November 1999 to June 2004 in order to evaluate smoking initiation patterns in youth as they progressed from late childhood to mid-adolescence.

Although the overall survey consisted of 9–18 year old youth, in order to have three rounds of follow-up, the sample for this analysis consisted of the 9–16 year-old youth who reported that they had “Never smoked” and had a parent/guardian who also answered the T1 survey at baseline (n=5705 dyads). Thus, our cohort was 9–16 years of age at baseline and 10–17 years of age at the first year of follow-up for incidence of smoking initiation. Total sample size for dyads at T2, T3, and T4 was: 4875, 4372, and 3829, respectively. Table 1 provides the detailed information for the sample. Data analysis activities were approved by our institutional review board.

Table 1.

Sample descriptive statistics for the main variables at baseline (T1).

| Measures | N | Weighted percent/weighted mean | Weighted std error | Min | Max | Missing (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Youth age at baseline | 5705 | 12.03 | 0.03 | 9 | 16 | 0 |

| Gender | 5705 | |||||

| Male | 2969 | 51% | 0 | |||

| Race/ethnicity | 5705 | |||||

| White (Non-Hispanic) | 3737 | 63% | 0 | |||

| Black or African American | 896 | 17% | 0 | |||

| Hispanic | 857 | 16% | 0 | |||

| Other | 215 | 4% | 0 | |||

| Parental education | 5661 | |||||

| College or higher | 2607 | 46% | 0.77 | |||

| Family structure | 5705 | |||||

| Two parents | 4114 | 72% | 0 | |||

| Tobacco variables | ||||||

| Parental smoking status | 5694 | |||||

| Ever | 3901 | 68% | 0.2 | |||

| Peer smoking influence: | 5672 | |||||

| Time spent with friends who smoked Ever | 648 | 13% | 0.58 | |||

| Parental influences | ||||||

| Parent-adolescent connectedness (Y) | 5561 | 1.24 | 0.03 | 0 | 3 | 2.52 |

| Parental monitoring (Y) | 5599 | 1.47 | 0.03 | 0 | 3 | 1.85 |

| Perceived parental punishment (T) | 2971 | 4.6 | 0.02 | 1 | 5 | 0.74 |

T1=round 1 of the NSPY survey.

Y=as reported by all youth in the sample who were 9–18 years of age.

T=as reported by all youth in the sample who were 14–18 years of age.

2.1.2. Assessment

The NSPY questions were chosen to resemble questions from the Monitoring the Future, National Household Education Survey, and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (Thomas & Perera, 2006). Parental consent and youth assent to conduct the interviews were obtained.

2.1.3. Measures

2.1.3.1. Outcome variable

The outcome variable of interest was smoking status after T1. Responses to the questions regarding smoking behavior within each round T2 to T4 were combined to create a tobacco use index broadly based on the categories used by Bernat et al. (2008) and Leatherdale (2008). The categories were then re-defined as: (1) Never Smoker: someone who has never smoked or (2) Smoking Initiators: included both Ever Smokers (defined as someone who smoked some or regularly but not in the last 30 days) and Current Smokers (defined as someone who reported any smoking in the last 30 days). In order to estimate cumulative rates, the first “yes” answer during any of the follow-up interviews marked the smoking initiation for never smokers and was used for the estimation of incidence rates.

2.1.3.2. Sociodemographic variables

Race/ethnicity was defined by self-report on the adolescent questionnaire. For the analyses, youth were categorized as Black/Non-Hispanic, White/Non-Hispanic, Hispanic, or other race/ethnicity. Adolescent age at interview was derived from the respondent’s date of birth. Gender was noted by the interviewer. Highest parent education level and family structure (defined as 1 vs. 2 parent household) were obtained by parent self-report at T1.

2.1.3.3. Tobacco variables

Parental smoking status was determined by asking: “Have you ever smoked a cigarette?” Peer smoking influence was collected longitudinally from T1–T4 and was assessed by asking: “How many times have you spent with friends who smoke cigarettes in the last 7 days?” This was categorized as never (0 days) and ever (at least once) for analysis.

2.1.3.4. Parental influence measures

Parental influences as reported by youth were evaluated, and composite scores for each measure were created based on construction by NSPY (Hornik et al., 2003; Orwin et al., 2005): connectedness, monitoring, and perceived punishment for smoking in youth. It should be noted that perceived parental punishment referred to both smoking and drinking, and was asked only of youth ages 14–18 (please see Table 2). Internal consistency was checked for constructed measures with more than one question per measure (Cronbach’s alpha: 0.78–0.80). For all measures, the minimum score was zero, where a higher score represented a higher degree of the characteristics of the measure.

Table 2.

Family influence variables to be assessed within the NSPY database.

| Family influences | Youth/parent report | Sample questions | # questions | Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent–adolescent connectedness | Y | In the last 30 days, I really enjoyed being with my parents/caregivers | 3 | 0.80 |

| Parental monitoring | Y | How often does at least one of your parents know what you are doing when you are away from home? | 2 | 0.78 |

| Perceived parental punishment | T | If one of your parents knew that you used tobacco or alcohol, how likely is it that he or she would punish you in some way? | 1 | N/A |

Y=as reported by the youth (ages 9–18 years).

T=as reported by the teens (ages 14–18 years).

N/A=not applicable – only one question per variable.

2.2. Data analysis

All analyses were based on using weighted data sampling techniques, the pairwise longitudinal weights were used for all analyses. The use of weighted sample data in our analysis takes into account the disproportionate representation of certain subgroups in the raw sample and accounts for varying selection probabilities (Westat, 2006, Chaps. 1–7). All of the weights included have been adjusted for differential response rates and have been calibrated (post-stratified) to independent estimates of population counts, to compensate for differences between the weighted sample distributions and the corresponding population distributions that result from differential nonresponse and under coverage (Hornik et al., 2003; Orwin et al., 2005). These adjustments are taken into account in the sample weights provided in the NSPY RUF dataset. A cohort-sequential design was selected as an appropriate analysis in keeping with the analysis strategy of Tang and Orwin (2009). This design was selected as it can be used to disentangle age-cohort confounds, by allowing incorporation of multiple cohorts to describe a common trend over a longer period of time than is covered by each cohort individually. The technique involves the use of successive logistic regressions; specifically, baseline (T1) risk factors were used to predict smoking initiation at T2, T2 and T3 risk factors were used to predict smoking initiation at T3 and T4, respectively. The Never Smoking group was consistently used as the reference group. The covariates controlled in modeling parental influence variables were race/ethnicity, youth gender, parental education, parental smoking status, family structure, and peer smoking, as these were considered clinically important covariates (Ellickson, Orlando, Tucker, & Klein, 2004a; Griesler & Kandel, 1998), a priori. Similarly when considering peer smoking as the independent variable of interest; race/ethnicity, youth gender, parental education, parental smoking status, and family structure were included as covariates in the model. An attrition analysis was done to examine the association of the variables of interest, parental influence and peer smoking, on loss to follow-up. SUDAAN®, release 10 was used in all analyses to incorporate the replicate weights and account for the complex survey design, using the Jackknife method recommended by NSPY.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive statistics and sample numbers

Table 1 shows the descriptive statistics for the sample at T1. There are 5705 dyads for analysis with the youth reporting never smoking; the sample is approximately evenly split with respect to gender, and is 63% White non-Hispanic, 17% African American, and 16% Hispanic. The youth have a mean age of 12, and 72% are in a two-parent household. Forty-six percent of the parents have a college education or higher, and 68% are ever smokers. Table 3 shows the number of adolescents who remained never smokers by age. Attrition analysis revealed no statistically significant association of the parental influence variables and peer smoking at T1 with attrition. However, there were statistically signiflcant effects of child gender (OR=1.17; 95% CI 1.02–1.34 for female), age (OR=1.33; 1–27—1.38 for each year increase), and family income (0.88; 0.83–0.94 for each $20,000 increase in household income).

Table 3.

Sample N by age.

| Sample N (number of never smokers)

| ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age cohorts (years) | Number of youth who remained never smokers by age

|

|||||||

| 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | |

| 9 | 761 | 740 | 651 | 604 | ||||

| 10 | 838 | 779 | 696 | 603 | ||||

| 11 | 750 | 679 | 564 | 467 | ||||

| 12 | 866 | 746 | 642 | 523 | ||||

| 13 | 757 | 620 | 506 | 420 | ||||

| 14 | 400 | 314 | 261 | |||||

| 15 | 306 | 244 | ||||||

| 16 | 197 | |||||||

The analysis sample consisted of the 9–16 year-old youth who reported that they had “Never smoked” at T1 and were then followed for up to three subsequent rounds (T2–T4).

3.2. Incidence rates of smoking initiation

Table 4 presents the estimates of population cumulative incidence rates of smoking from age 10 to age 17; the estimates were based on the eight age cohorts (9–16 years of age at baseline) who were never smokers at baseline (N=5705). Although the youngest age at the first round was 9 years old, for our analysis, our first outcome was at the one year follow-up, and thus those children were now 10 years old at the time. Overall, the incidence rates increase from 1.4% at age 10 to 23.8% at age 17, with approximate doubling between ages 11 and 13, 12 and 14 and between 13 and 15 years.

Table 4.

Cumulative population incidence rates (%) of smoking initiation.

| Age cohorts (years) | Youth Age at smoking initiation

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | |

| 9 | 1.39 | 4.64 | 8.56 | |||||

| 10 | 3.51 | 7.06 | 10.9 | |||||

| 11 | 7.25 | 8.74 | 14.33 | |||||

| 12 | 12.55 | 14.38 | 18.38 | |||||

| 13 | 14.65 | 22.05 | 21.36 | |||||

| 14 | 20.41 | 28.84 | 26.7 | |||||

| 15 | 18.65 | 23.27 | ||||||

| 16 | 21.36 | |||||||

| Mean | 1.39 | 4.08 | 7.62 | 10.73 | 14.45 | 20.28 | 22.95 | 23.78 |

| 95% CI | (0.39, 2.39) | (2.28, 5.87) | (5.77, 9.47) | (8.36, 13.1) | (11.8, 17.1) | (17.3, 23.2) | (19.0, 27.0) | (19.1, 28.4) |

CI=confidence interval.

3.3. Risk and protective influences of smoking initiation and examination of the dynamic nature of the relationship

3.3.1. Risk and protective influences in initial models

We identified the independent risk and protective influences of smoking initiation by age. Among the six risk factors (youth race/ethnicity and gender; parental: education and smoking status; peer smoking, and family structure), peer smoking was the most important. The most dramatic effect may be seen in the earlier teenage years, but there appears to be contribution to smoking initiation across all ages; this is seen in Fig. 1.1.

Fig. 1.1.

Population trajectories of smoking initiation and the risk factor of peer smoking.

Apart from peer smoking, only family structure, parental education and parental smoking were significant risk factors in any of the models. Living in a household without two parents approximately doubled the odds of smoking initiation in those adolescents less than 15 years; range 1.5 to 2.9. Similarly, having a parent that ever smoked approximately doubled the odds of initiating smoking between 12 and 16 years of age; range 1.5 to 2.9. For those adolescents whose parents had less than some college education, the odds of initiating smoking was about 50% higher; range 1.3 to 1.8.

3.3.2. Examination of the dynamic nature of the relationship

The adjusted odds ratios for the parental influence measures at each age by cohort are shown in Table 5 and Figs. 1.1 and 1.2. Estimates show the effect of risk (peer smoking) or protective (parental influences) factors for each of the age cohorts at a given age on predicting smoking initiation a year later; the statistically significant odds ratios are in bold print. This demonstrates the dynamic, changing effect of adolescent perception of both parental influence and peer influence on smoking initiation as the adolescent ages. The odds ratios reveal the significant protective effects of parent connectedness and punishment and to a degree monitoring, while simultaneously peer smoking is having a significant opposite effect. Parental connectedness appears to have the most consistent protective effect during the earlier to mid teenage years from 13 to 16, where, at the same time peer smoking is having the most influence in the opposite direction. It should be noted that not all of these are statistically significant. The overall odds for each age and the associated 95% confidence interval are shown, those odds ratios ≤0.8 are statistically significant.

Table 5.

Odds of smoking initiation in former never smokers between ages 11 and 17 for (a) peer smoking, and the protective parental influences of: (b) connectedness, (c) punishment, and (d) monitoring control for other risk factors.

| Youth Age at smoking initiation

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Never smoker at age | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 |

| (a) Peer smoking (Y) | |||||||

| 10 | 2.02 | 3.1 | 6.46 | ||||

| 11 | 1.76 | 1.56 | 2.3 | ||||

| 12 | 3.79 | 3.62 | 2.2 | ||||

| 13 | 3.81 | 2.69 | 1.84 | ||||

| 14 | 2.47 | 1.09 | 1.83 | ||||

| 15 | 1.71 | 1.09 | |||||

| 16 | 1.67 | ||||||

| Overall OR (95% CI) | 2.02 (0.92, 3.12) | 2.53 (2.39,2.66) | 3.57 (2.48, 4.66) | 3.43 (2.36, 4.5) | 2.52 (2.38,2.65) | 1.31 (1.13, 1.49) | 1.53 (1.26, 1.8) |

| (b) Connectedness (Y) | |||||||

| 10 | 0.92 | 0.6 | 1.18 | ||||

| 11 | 0.79 | 0.83 | 0.64 | ||||

| 12 | 0.66 | 0.86 | 0.63 | ||||

| 13 | 0.74 | 0.67 | 0.73 | ||||

| 14 | 1 | 0.6 | 0.96 | ||||

| 15 | 1.11 | 0.64 | |||||

| 16 | 0.83 | ||||||

| Overall OR (95% CI) | 0.92 (0.78, 1.06) | 0.69 (0.62, 0.76) | 0.82 (0.6,1.04) | 0.7 (0.62, 0.8) | 0.71 (0.61, 0.82) | 0.82 (0.53, 1.11) | 0.97 (0.74, 1.2) |

| (c) Monitoring (Y) | |||||||

| 10 | 0.66 | 1.08 | 0.81 | ||||

| 11 | 0.9 | 0.75 | 0.73 | ||||

| 12 | 0.97 | 0.93 | 0.75 | ||||

| 13 | 0.85 | 0.98 | 0.74 | ||||

| 14 | 0.84 | 0.64 | 0.31 | ||||

| 15 | 0.74 | 1.3 | |||||

| 16 | 1.07 | ||||||

| Overall OR (95% CI) | 0.66 (0.42, 0.9) | 0.98 (0.86, 1.1) | 0.85 (0.66, 1.05) | 0.84 (0.66, 1.03) | 0.82 (0.6, 1.04) | 0.68 (0.52, 0.83) | 0.98 (0.69, 1.27) |

| (d) Punishment (T)a | |||||||

| 12 | 0.72 | 0.75 | 0.73 | ||||

| 13 | 1.12 | 0.84 | 0.9 | ||||

| 14 | 0.85 | 0.95 | 1.36 | ||||

| 15 | 0.83 | 0.81 | |||||

| 16 | 0.78 | ||||||

| Overall OR (95% CI) | 0.72 (0.52, 0.9) | 0.88 (0.76, 1) | 0.8 (0.67, 0.94) | 0.87 (0.6, 1.12) | 0.93 (0.68, 1.18) | ||

OR=adjusted odds ratio.

CI=confidence interval.

Bold print signifies that OR was statistically significant at p<.05.

Y=as reported by all youth in the sample who were 9–18 years of age.

T=as reported by all youth in the sample who were 14–18 years of age.

All analyses were controlled for race/ethnicity, youth gender, highest parent education, family structure, and parental smoking status. Tables b, c, and d were also controlled for peer smoking. Please note that in Tables a–d, the 9 year-old cohort is actually represented by “Never Smoker at age 10.” As we had so few that initiated smoking between 9 and 10 years of age, we did not analyze this group; thus only 7 age groups are shown in these tables.

The parental punishment questionnaire was only administered to youth who were 14–18 years old, although apparently a portion of the questionnaire was administered to those of at least 13 years of age from the 12 year old cohort; thus Table d presents the results for “Youth Age at smoking initiation” for 13–17 year old youth only.

Fig. 1.2.

Population trajectories of smoking initiation and the protective parental influences of connectedness, monitoring, and punishment.

Our analysis has found support for both of our hypotheses: Hypothesis 1. Youth with consistently strong parental influences overall from late childhood throughout mid-adolescence will have lower rates of smoking initiation. Significant parental influence was found in the early teenage years (ages 12 to 15) with higher levels of the three influences being protective against smoking initiation. Parent–youth connectedness significantly decreased the odds of smoking initiation by 14–40% in 12–15 year-olds. Parental monitoring decreased smoking initiation risk by 36–54% in 11–16 year-old youth, and increased punishment decreased the odds of initiation by 15–28% in 13–15 year-olds. Hypothesis 2. Peer influence on smoking initiation increases overall during adolescence as parental influences decrease. It appears that having friends who smoked played a sustained role during early to middle adolescence (age 12–15 years). The odds ratios ranged from 1.76 to 6.46 during this period. Significant odds were consistently produced by age cohorts 10, 11, 12, 13, and 14 years. The estimates were nonsignificant in the 15 years and older age cohorts. Thus, instead of observing an increasing peer influence during adolescence, it appeared that the peer influence as measured by reported association with friends who smoked diminished during later adolescence.

4. Discussion

This study provides important population incidence rates of smoking initiation among American youth ages 10 through 17 during the study years 1999–2004. The results suggest that the risk of smoking initiation spans early to mid-adolescence. A doubling of the rates occurred during early adolescence, between ages 11 and 13, between 12 and 14 and between 13 and 15 years. Among the seven identified important risk factors, based on prior studies of smoking initiation (Ellickson et al., 2004a; Gilman, Abrams, & Buka, 2003; Griesler & Kandel, 1998; Kim et al., 2009), the single most important across nearly all ages and age cohorts was the association with peers who smoked. This influence continued to be a risk factor up until age 16 and it is especially striking that this association resulted in an increased odds of initiation of 6.5 in the 10 year-old cohort at age 13. These findings were consistent with prior work which showed that adolescents with friends who smoke are more likely to smoke themselves or take up smoking with time (Simons-Morton & Farhat, 2010), and underscore the need to develop prevention interventions that emphasize the importance of adolescent’s choices of friends (Bricker, Peterson, Sarason, et al., 2007; Bricker et al., 2006a; Kim et al., 2009). While prior studies have supported the notion of the increasing importance of peer influences at one point in time in predicting tobacco initiation patterns at a later time in adolescence (Bricker, Peterson, Sarason, et al., 2007; Bricker et al., 2006a), our findings add to the literature by examining the concurrent effects of peer smoking influences at each of the 4 time points examined. This is important because friends’ smoking is highly variable in the same way that smoking behavior and friendships are highly variable and unstable during adolescence (Bricker et al., 2006b; Kandel, 1996; Petraitis, Flay, & Miller, 1995). Thus, our study takes these changes into account during the highly fluctuant adolescent period and showed consistency in the continued risk represented by peer smoking associations.

Similar to prior work, we found an increased risk of smoking initiation in youth from single parent homes, and youth whose parents had lower education or a history of prior smoking (Ellickson et al., 2004a; Gilman et al., 2003; Griesler & Kandel, 1998; Kim et al., 2009). Our results can be used to determine the best target population of parents and adolescents in future prevention intervention work. Unlike prior research which has shown that smoking initiation is more likely in boys (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 2010; Johnston et al., 2011) and increasingly more likely in Caucasians and then Hispanics, with African Americans showing decreased risk of initiation (Ellickson, Orlando, Tucker, & Klein, 2004b; Orlando, Tucker, Ellickson, & Klein, 2004), we did not find differences in smoking initiation risk by gender or race/ethnicity.

Our primary research interest was to see if there was empirical evidence of a shift of importance of parental influence and/or peer influence by age. Just as parental influences change during adolescence as the teen strives towards independence, we examined each of the protective influences at each time point. Our analysis was unlike prior studies where influences were evaluated at one time point to determine if they were predictive of smoking at multiple later time points (Avenevoli & Merikangas, 2003; Bauman et al., 2001; Bernat et al., 2008). We found that the parental influences of connectedness and punishment for smoking remained important to youth up until age 15 (mid-adolescence), and that parental monitoring continued to be important in protecting against smoking through age 16. Peer smoking associations continued to be a risk factor for smoking initiation through age 16, and even though these influences appeared to be higher than the protective nature of parenting practices, it is important to see that youth reported parental influence was significantly protective despite the effect of the peers. Parental connectedness was most consistently associated with protection of smoking initiation between the ages of 12 and 15, consistent with the strongest influence of peers on initiation of smoking. Parental monitoring brought significant influence at the younger and older ages of 11 and 16 with punishment having influence in between at 13 to 15 years. As all these protective influences on smoking initiation were measured as perceived by the adolescent it seems convincing that parental influences are an important consideration as a deterrent. Other important factors, family structure, parental education and history of smoking, are not modifiable, yet contribute to greater smoking initiation in the adolescent years.

The study was not intended to evaluate all possible risks or protective factors associated with adolescent smoking initiation and we were limited by the NSPY questions themselves. Thus, important parental influences that may be protective against smoking initiation such as parental supportiveness and acceptance, or frequency and quality of antismoking messages were not included in the NSPY. While our analysis looked at the risk factor of time spent with peers who smoked, NSPY did not include questions that specifically examined the association of peer influences that are associated with smoking uptake such as best friends, peer groups, and crowd affiliations (Simons-Morton & Farhat, 2010). In addition, since the assessment of parental smoking status was a measure of ever smoking, it is not possible to assess the time period in which the parent smoked; thus it is unknown if the child directly observed the parent’s smoking behavior. However, this measure may under represent the effect of parental smoking on the child’s smoking status. It is not possible to determine if our finding of protection by perceived parental punishment referred exclusively to smoking, as this NSPY question queried youth about the likelihood that their parent would punish them for smoking cigarettes or drinking alcohol. Lastly, the underlying assumption of the cohort-sequential design is that there is no cohort effect. The estimated cumulative incidence rates track very well within the ages for each cohort. Additionally, for each parental influence and peer smoking we see good consistency, with the final year for each cohort potentially being the outlier, with the smaller denominator. The advantage of this design for this cohort is that we can examine and present this detail due to adequate sample size and that at each age of smoking initiation we have representation from each round of the survey. We feel that there is minimal evidence of a cohort effect and that we followed appropriate methods to address this assumption. Despite these limitations, our study adds to the literature by identifying specific parental influences that were protective against initiation in a triethnic sample of youth. In addition, the strengths of the present study are that it focuses on perception of influence as reported by the adolescent, is a longitudinal design that allows examination of four time points and thus the change in smoking behavior over a period of four years, and also has a large sample size.

The findings from this study provide insight into changes in risk factors for smoking initiation over time, and suggest protective factors that should be augmented in smoking prevention research for youth at different ages. First, to reduce incidence rates of smoking among adolescents, prevention programs should be designed to include both parent and peer components. Peer components may be used to establish a culture of non-tobacco use and provide peer reinforcement for a tobacco-free life. Parent components may help parents to learn strategies to connect with their child, set rules and consequences for smoking, monitor their adolescents, and even ways to help parents quit tobacco use. The peer component should be delivered throughout adolescence, and the parent component should be delivered as early as possible (e.g., preadolescence to early adolescence).

HIGHLIGHTS.

Longitudinal data from 8 nationally representative age cohorts of nonsmokers used.

Examined the timing of parental and peer influences on youth smoking initiation.

Analysis was a cohort-sequential design, using lagged logistic regression models.

Association with peers who smoke remains a strong risk factor of smoking initiation.

Connectedness, monitoring, and punishment remain important in reducing smoking risk.

Acknowledgments

Role of funding sources

This research was supported by grant #5R03CA142099 from the National Cancer Institute awarded to the first author.

The National Survey of Parents and Youth was conducted by the National Institute on Drug Abuse through a cooperative agreement that calls for scientific collaboration between the grantees and the National Institute on Drug Abuse staff. Data was provided by the Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research (ICPSR).

Abbreviations

- NSPY

National Survey of Parents and Youth

- RUF

Restricted Use Files

- T1

round 1

- T2

round 2

- T3

round 3

- T4

round 4

- Y

responses as reported by all youth in the sample who were 9–18 years of age

- T

responses as reported by all youth in the sample who were 14–18 years of age

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

Footnotes

Contributors

All authors have contributed significantly to the paper and endorse the final manuscript. Specifically, the first author (E.M. Mahabee-Gittens) conducted the literature review, contributed to the development of hypotheses, and wrote the manuscript with input from the second, third, and fourth authors. The second author (Yang Xiao) contributed to the study design, ran the statistical analyses and assisted in writing the manuscript. The third author (J.S. Gordon) provided consultation on hypothesis development and assisted in writing the manuscript. The fourth author (J.C. Khoury) contributed to the development of hypotheses, was responsible for the study design, directly supervised the statistical analyses, and assisted in writing the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

All authors declare that they have no con3icts of interest.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Policy statement—Tobacco use: A pediatric disease. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1474–1487. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2114. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-2114 (peds.2009–2114 [pii]) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S, Merikangas KR. Familial influences on adolescent smoking. [Research Support, U.S. Gov’t, P.H.S. Review] Addiction. 2003;98(Suppl 1):1–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.2.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman KE, Carver K, Gleiter K. Trends in parent and friend influence during adolescence: The case of adolescent cigarette smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2001;26(3):349–361. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00110-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernat DH, Erickson DJ, Widome R, Perry CL, Forster JL. Adolescent smoking trajectories: Results from a population-based cohort study. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;43(4):334–340. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.014 (S1054-139X(08)00157-2 [pii]) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Peterson AV, Robyn Andersen M, Leroux BG, Bharat Rajan K, Sarason IG. Close friends’, parents’, and older siblings’ smoking: Reevaluating their influence on children’s smoking. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006a;8(2):217–226. doi: 10.1080/14622200600576339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14622200600576339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Peterson AV, Robyn Andersen M, Leroux BG, Bharat Rajan K, Sarason IG. Close friends’, parents’, and older siblings’ smoking: Reevaluating their influence on children’s smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2006b;8(2):217–226. doi: 10.1080/14622200600576339. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14622200600576339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Peterson AV, Jr, Andersen MR, Sarason IG, Rajan KB, Leroux BG. Parents’ and older siblings’ smoking during childhood: Changing influences on smoking acquisition and escalation over the course of adolescence. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2007;9(9):915–926. doi: 10.1080/14622200701488400. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14622200701488400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Peterson AV, Jr, Sarason IG, Andersen MR, Rajan KB. Changes in the influence of parents’ and close friends’ smoking on adolescent smoking transitions. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(4):740–757. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.020. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker JB, Rajan KB, Zalewski M, Ramey M, Peterson AV, Andersen MR. Psychological and social risk factors in adolescent smoking transitions: A population-based longitudinal study. Health Psychology. 2009;28(4):439–447. doi: 10.1037/a0014568. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0014568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Tobacco use among middle and high school students — United States, 2000–2009. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2010;59(33):1063–1068. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Orlando M, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. From adolescence to young adulthood: Racial/ethnic disparities in smoking. American Journal of Public Health. 2004a;94(2):293–299. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.293. http://dx.doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellickson PL, Orlando M, Tucker JS, Klein DJ. From adolescence to young adulthood: Racial/ethnic disparities in smoking. [Comparative Study Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] American Journal of Public Health. 2004b;94(2):293–299. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.2.293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman SE, Abrams DB, Buka SL. Socioeconomic status over the life course and stages of cigarette use: Initiation, regular use, and cessation. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 2003;57(10):802–808. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.10.802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griesler PC, Kandel DB. Ethnic differences in correlates of adolescent cigarette smoking. The Journal of Adolescent Health. 1998;23(3):167–180. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harakeh Z, Scholte RH, de Vries H, Engels RC. Parental rules and communication: Their association with adolescent smoking. Addiction. 2005;100(6):862–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01067.x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01067.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffman BR, Monge PR, Chou CP, Valente TW. Perceived peer influence and peer selection on adolescent smoking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32(8):1546–1554. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.11.016 (S0306-4603(06)00349-2 [pii]) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornik R, Maklan D, Cadell D, Barmada C, Jacobsohn L, Henderson V, et al. Evaluation of the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign: 2003 Report of Findings. 2003 Retrieved from http://www.nida.nih.gov/PDF/DESPR/1203report.pdf.

- Johnston LD, O’Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2010. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, The University of Michigan; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kandel DB. The parental and peer contexts of adolescent deviance: An algebra of interpersonal influences. Journal of Drug Issues. 1996;26(2):289–315. [Google Scholar]

- Kim MJ, Fleming CB, Catalano RF. Individual and social influences on progression to daily smoking during adolescence. Pediatrics. 2009;124(3):895–902. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2015. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krohn MD, Massey JL, Skinner WF, Lauer RM. Social bonding theory and adolescent cigarette smoking: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1983;24(4):337–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherdale ST. What modifiable factors are associated with cessation intentions among smoking youth? Addictive Behaviors. 2008;33(1):217–223. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsueda RL, Heimer K. Race, family structure and delinquency: A test of differential association and social control theories. [Article] American Sociological Review. 1987;52(6):826–840. [Google Scholar]

- Orlando M, Tucker JS, Ellickson PL, Klein DJ. Developmental trajectories of cigarette smoking and their correlates from early adolescence to young adulthood. [Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov’t] Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004;72(3):400–410. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.400. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.3.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orwin R, Cadell D, Chu A, Kalton G, Maklan D, Morin C, et al. Evaluation of the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign: 2004 Report of Findings. Report prepared for the National Institute of Drug Abuse. 2005 (Contract No. N01DA-8-5063. Retrieved from http://www.drugabuse.gov/about/organization/despr/westat/NSPY2004Report/ExecSumVolume.pdf)

- Otten R, Engels RC, van de Ven MO, Bricker JB. Parental smoking and adolescent smoking stages: The role of parents’ current and former smoking, and family structure. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;30(2):143–154. doi: 10.1007/s10865-006-9090-3. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10865-006-9090-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petraitis J, Flay BR, Miller TQ. Reviewing theories of adolescent substance use: Organizing pieces in the puzzle. Psychological Bulletin. 1995;117(1):67–86. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.117.1.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prokhorov AV, Winickoff JP, Ahluwalia JS, Ossip-Klein D, Tanski S, Lando HA, et al. Youth tobacco use: A global perspective for child health care clinicians. [Review] Pediatrics. 2006;118(3):e890–e903. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0810. http://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-0810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG. The protective effect of parental expectations against early adolescent smoking initiation. Health Education Research. 2004;19(5):561–569. doi: 10.1093/her/cyg071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton BG, Farhat T. Recent findings on peer group influences on adolescent smoking. Journal of Primary Prevention. 2010;31(4):191–208. doi: 10.1007/s10935-010-0220-x. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s10935-010-0220-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons-Morton B, Chen R, Abroms L, Haynie DL. Latent growth curve analyses of peer and parent influences on smoking progression among early adolescents. Health Psychology. 2004;23(6):612–621. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.6.612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton B, Cole M, Galbraith J, Li X, Pendleton S, Cottrel L, et al. Randomized trial of a parent intervention: Parents can make a difference in long-term adolescent risk behaviors, perceptions, and knowledge. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine. 2004;158(10):947–955. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.10.947. http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.158.10.947 (158/10/947 [pii]) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. NSDUH series H-41. 2011 (Retrieved February 21, 2012, from http://www.samhsa.gov/data/NSDUH/2k10NSDUH/2k10Results.pdf)

- Tang Z, Orwin RG. Marijuana initiation among American youth and its risks as dynamic processes: Prospective findings from a national longitudinal study. Substance Use & Misuse. 2009;44(2):195–211. doi: 10.1080/10826080802347636. [Research Support, N.I.H., Extramural] http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10826080802347636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas R, Perera R. School-based programmes for preventing smoking. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006;3:CD001293. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001293.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S Department of Health and Human Services. The biology and behavioral basis for smoking-attributable disease: A report of the Surgeon General. 2010 Retrieved February 21, 2012, from http://www.surgeongeneral.gov/library/tobaccosmoke/report/executivesummary.pdf. [PubMed]

- U.S Department of Health and Human Services. Tobacco objectives. 2012 Retrieved February 21, 2012, from http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topicsobjectives2020/objectiveslist.aspx?topicId=41.

- United States Public Health Service Office of the Surgeon General. The health consequences of involuntary exposure to tobacco smoke: A report of the Surgeon General [Atlanta, Ga] Rockville, MD: U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Coordinating Center for Health Promotion, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health, Office of the Surgeon General; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Westat. User’s guide for the evaluation of the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign. Vol. 1. Rockville, MD: National Survey of Parents and Youth; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Westat. Restricted Use Files for the National Survey of Parents and Youth (NSPY), Rounds 1, 2, 3, and 4. Vol. 1. Rockville, MD: 2006. User’s guide for the evaluation of the National Youth Anti-Drug Media Campaign. [Google Scholar]