Abstract

Large-scale proteomic approaches have identified numerous mitochondrial acetylated proteins; however in most cases, their regulation by acetyltransferases and deacetylases remains unclear. Sirtuin 3 (SIRT3) is an NAD+-dependent mitochondrial protein deacetylase that has been shown to regulate a limited number of enzymes in key metabolic pathways. Here, we use a rigorous label-free quantitative MS approach (called MS1 Filtering) to analyze changes in lysine acetylation from mouse liver mitochondria in the absence of SIRT3. Among 483 proteins, a total of 2,187 unique sites of lysine acetylation were identified after affinity enrichment. MS1 Filtering revealed that lysine acetylation of 283 sites in 136 proteins was significantly increased in the absence of SIRT3 (at least twofold). A subset of these sites was independently validated using selected reaction monitoring MS. These data show that SIRT3 regulates acetylation on multiple proteins, often at multiple sites, across several metabolic pathways including fatty acid oxidation, ketogenesis, amino acid catabolism, and the urea and tricarboxylic acid cycles, as well as mitochondrial regulatory proteins. The widespread modification of key metabolic pathways greatly expands the number of known substrates and sites that are targeted by SIRT3 and establishes SIRT3 as a global regulator of mitochondrial protein acetylation with the capability of coordinating cellular responses to nutrient status and energy homeostasis.

Lysine acetylation is one of the most common posttranslational modifications among cellular proteins and regulates a variety of physiological processes including enzyme activity, protein–protein interactions, gene expression, and subcellular localization (1). Large-scale proteomic surveys have demonstrated that lysine acetylation is prevalent within mitochondria (2, 3). As the central regulators of cellular energy production, mitochondria require a coordinated response to changes in nutrient availability to respond to metabolic needs. In addition to ATP production, mitochondria are essential for regulation of fatty acid oxidation, apoptosis, and amino acid catabolism. Disruption of these processes is associated with a variety of neurodegenerative disorders and metabolic diseases (4, 5). Understanding the role of lysine acetylation in mitochondrial function will likely provide insight into altered metabolism in dysregulated or disease states.

The sirtuins (SIRT1–7) are an evolutionary conserved family of NAD+-dependent deacetylases (6). SIRT3, SIRT4, and SIRT5 are major, if not exclusively, localized in the mitochondrial matrix (7, 8). SIRT3 is the primary regulator of mitochondrial lysine acetylation (9), whereas SIRT5 regulates lysine malonylation and succinylation (10, 11), and SIRT4 has no well established target except weak ADP ribosyltransferase activity (12). SIRT3 is highly expressed in mitochondria-rich tissues and shows differentially regulated expression in liver and skeletal muscle in response to changes in nutrient availability such as fasting, high-fat diet, and caloric restriction (13–15), suggesting a role in coordinating metabolic responses across these tissues. No mitochondrial acetyltransferase is known to date, and mitochondrial acetylation may be caused by a reaction of lysine residues with acetyl-CoA in a nonenzymatic process.

SIRT3 regulates the acetylation and enzymatic activity of key enzymes in several metabolic pathways. Hyperacetylation of complex I and complex II in the respiratory chain of SIRT3−/− (KO) mice leads to reduced activity, indicating a role for SIRT3 in regulation of oxidative phosphorylation machinery and ATP production (16–18). SIRT3 also regulates ketogenesis through activation of hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA synthase 2 (HMGCS2) in the fasted state (19). KO mice show liver steatosis due to defective fatty acid oxidation through long-chain acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (ACADL) (14), and impaired insulin signaling in skeletal muscle due to increased oxidative stress (15). In addition, SIRT3 directly regulates oxidative stress through deacetylation and activation of superoxide dismutase (SOD2) (20–22). Lack of SIRT3 leads to a pseudohypoxic response associated with induction of hypoxia-inducible factor 1α stabilization and the Warburg effect, consistent with its tumor suppressor activity (23, 24). Finally, increased expression of SIRT3 during caloric restriction protects mice from age-related hearing loss through activation of isocitrate dehydrognease (IDH2) (25).

Recent reports have described widespread hyperacetylation of mitochondrial proteins in KO mice (9, 14, 15); however, the protein substrates and specific lysine residues that are deacetylated by SIRT3 remain largely unknown. To investigate the regulation of lysine acetylation in mitochondria and identify SIRT3 substrates, we used a quantitative proteomic approach to compare lysine acetylation in the fasted state in the liver of SIRT3−/− mice and WT animals. We demonstrate a robust method for enrichment of lysine acetylated peptides from liver mitochondria. Using a unique label-free quantitation method termed MS1 Filtering (26) in combination with a SIRT3−/− mouse model, we show that lysine acetylation increases in the absence of SIRT3 across a wide variety of mitochondrial proteins of critical importance to mitochondrial biology and metabolism.

Results

Enrichment and Identification of Lysine Acetylation Sites in Liver Mitochondria.

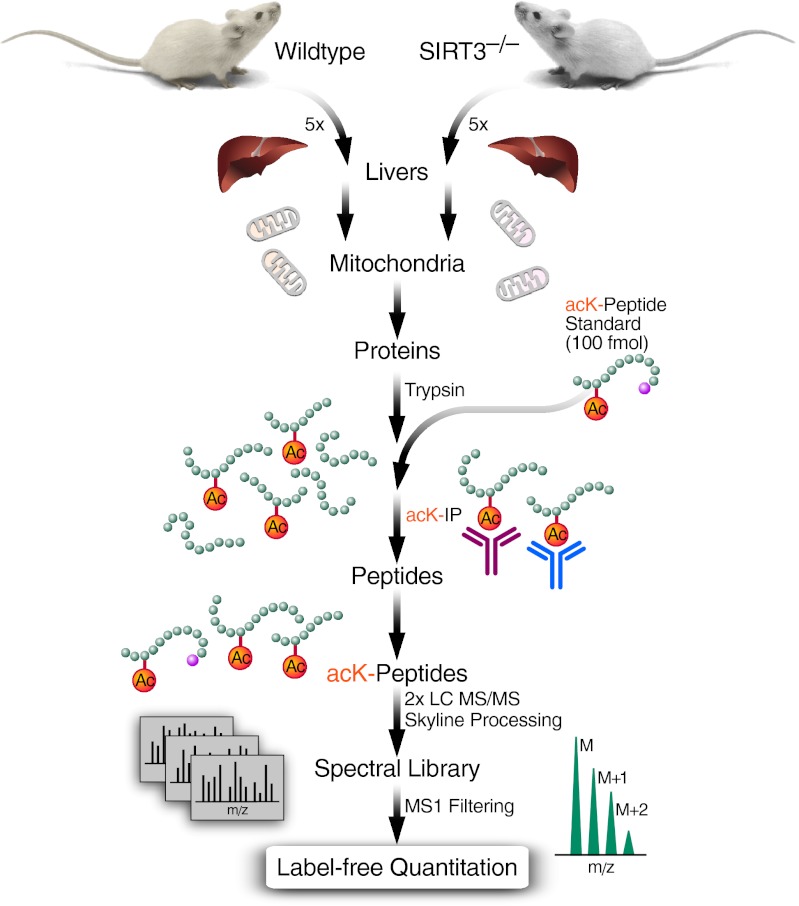

To determine changes in the lysine acetylome in the absence of SIRT3, we developed a robust workflow for the identification and quantitation of acetylated lysine (acK) peptides (Fig. 1). Mice were fasted 24 h before tissue harvest to maximize SIRT3 expression in the WT (14). Liver mitochondria were isolated from five WT and five KO mice by differential centrifugation. Samples were normalized to total mitochondrial and Western analysis using mitochondrial markers confirmed equal amounts of mitochondrial enrichment across animals (Fig. 2A). To control for process variability, two mitochondrial fractions per animal were prepared in parallel for MS analysis. Each sample was digested with trypsin, and 100 fmol of a synthetic heavy labeled acK peptide was spiked-in for normalization (27). Peptides containing acK were immunoprecipitated using a combination of two polyclonal anti-acetyllysine antibodies because we found this increases the diversity and efficiency of acK peptides detected (26). The enriched acK peptides were analyzed in duplicate by LC-MS/MS on a TripleTOF 5600 mass spectrometer, and data were searched against the mouse proteome.

Fig. 1.

Strategy for identification and quantitation of the SIRT3-regulated acetylome in mouse liver mitochondria. Liver mitochondria were isolated from five individual WT and SIRT3−/− male mice. Two process replicates from each of 10 mitochondrial protein isolates were digested separately with trypsin, generating 20 samples. The resulting peptide fractions were desalted, and 100 fmol of a heavy isotope-labeled acK-peptide standard (m/z 626.8604++; LVSSVSDLPacKR-13C615N4) was added. acK peptides were immunoprecipitated using two anti-acK antibodies. Enriched peptides were separated and analyzed in duplicate by HPLC-MS/MS. Data were processed using Skyline to generate a MS/MS spectral library of the identified acK peptides. Precursor ion intensity chromatograms for one or more isotopes (M, M+1, M+2) of each peptide were integrated using Skyline MS1 Filtering and used for label-free quantitation across all samples after normalization to the peak area of the peptide standard.

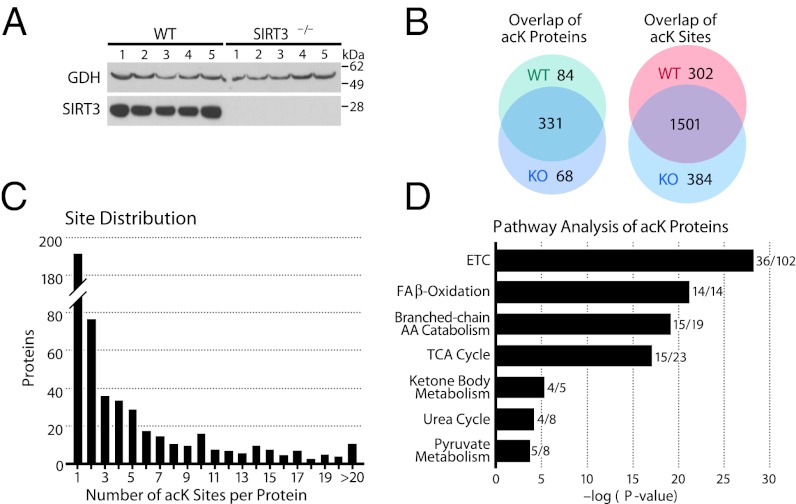

Fig. 2.

Identification of acetylated peptides and proteins by LC-MS/MS. (A) Western blot analysis of glutamate dehydrogenase (GDH) and SIRT3 in mitochondrial lysates from WT and SIRT3−/− mouse livers. (B) Overlap of identified acetylated proteins and peptides from WT and SIRT3−/− mice. (C) Distribution of acK sites identified per protein. (D) Pathway analysis of the mitochondrial acetylome with the number of proteins identified per pathway indicated.

Using a false discovery rate (FDR) cutoff of ≤1%, we identified 2,806 unique acK peptides (Dataset S1) encompassing 2,187 unique acK sites across 483 proteins (Dataset S2), with an overlap of 69% and 66%, respectively, between WT and KO (Fig. 2B). A higher number of unique sites were identified in KO vs. WT mice (384 vs. 302). The majority of proteins were multiacetylated, with 61% having two or more acK sites (Fig. 2C). The most acetylated protein was the highly abundant urea cycle protein carbamoyl phosphate synthase (CPS1) with 70 of 97 lysines acetylated.

To determine whether a particular subset of the mitochondrial proteome was preferentially acetylated, we performed a pathway enrichment analysis of all acetylated proteins (28) (Fig. 2D). Notably, all proteins from the fatty acid oxidation (FAO) pathway were acetylated. In addition to 79% of proteins involved in branched-chain amino acid (BCCA) metabolism (15 of 19 proteins), 65% of proteins in the citric acid cycle (15 of 23 proteins), and 80% of proteins involved in ketone body metabolism (4 of 5 proteins) were acetylated. There was also a significant enrichment for proteins involved in oxidative phosphorylation and pyruvate metabolism, demonstrating specific mitochondrial pathways in acetyl-CoA production and utilization are widely acetylated.

Label-Free Quantitation of acK Peptides in WT and SIRT3−/− Mice.

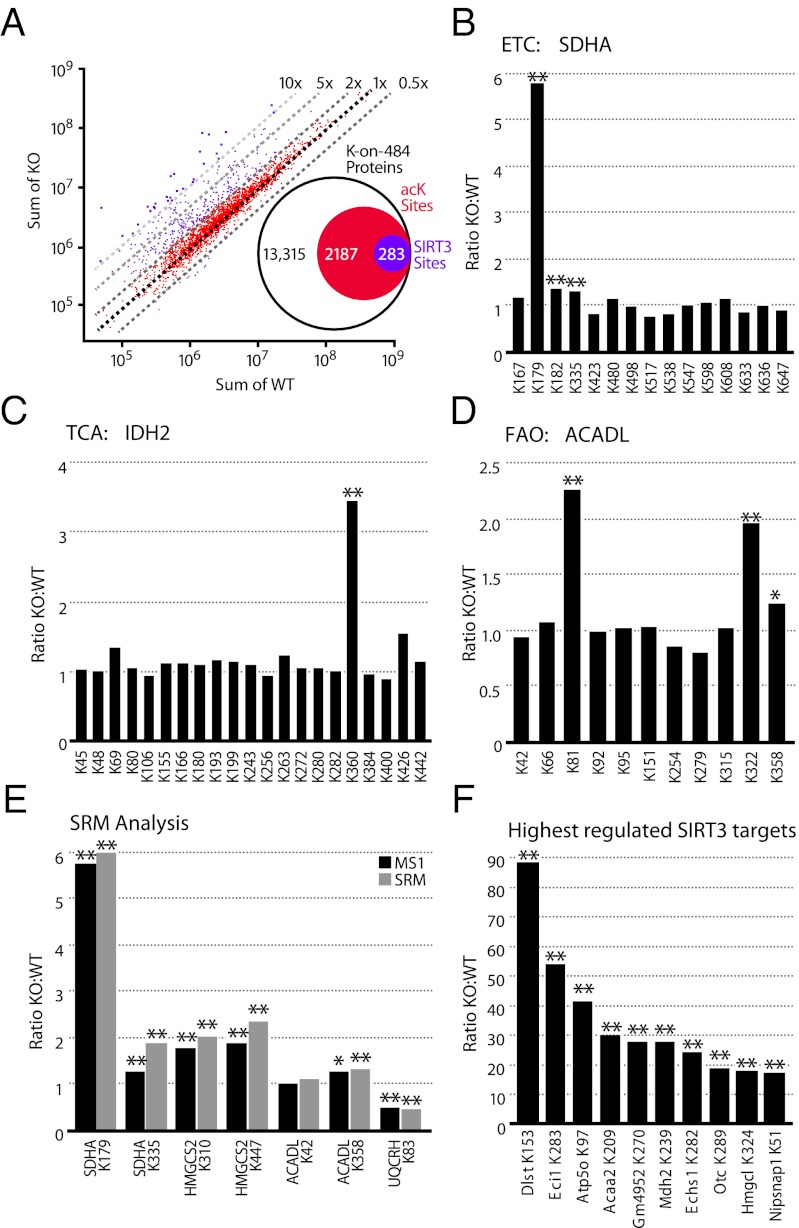

To identify true substrates of SIRT3 among all acetylated proteins and sites, we compared the relative level of acK peptide abundances between WT and KO mice using MS1 Filtering label-free quantitation. Although multiple peptides may be generated for a specific acK residue and targeted for quantitation, representative high-confidence peptides were selected based on having a tryptic cleavage at arginine or a nonacetylated lysine and lacking any secondary modifications. Once selected, the charge state with the highest signal intensity was used for quantitation, as secondary charge states, whereas generally in agreement (Dataset S3), had lower signal to noise and did not improve the overall statistics. Ion intensity measurements were normalized to a synthetic peptide standard, which had a coefficient of variation of 26%, indicating high reproducibility across samples. Of the 2,187 acK sites identified, quantitative data were obtained on 2,087 sites (Fig. 3A; Fig S1; Dataset S4). We found that acetylation at 283 sites present in 136 proteins increased more than twofold (P ≤ 0.01) in KO mice at an FDR of 0.04, whereas only 11 acK peptides showed at least a twofold decrease. To control for possible changes in protein abundance in the SIRT3 KO mice that could contribute to altered levels of acK peptides, we also compared the levels of unmodified peptides from 350 mitochondrial proteins in nonenriched protein fractions (Fig S2; Dataset S5). The vast majority of proteins remained unchanged, suggesting that the absence of SIRT3 in the KO animals did not result in large compensatory changes in protein expression. Therefore, changes in the levels of acK peptides between the WT and KO mice observed after affinity enrichment can be almost exclusively attributed to alterations in acetylation levels at specific lysines.

Fig. 3.

Identification of SIRT3 substrates by label-free quantitation. (A) Scatter plot of the acK peptides quantitated by MS1 Filtering after normalization. Dashed lines indicate the fold change in intensity between WT and KO. Peptides with a significant (P ≤ 0.01) at least twofold change are indicated in purple; all other peptides are in red. Inset summarizes the number of acK sites significantly changed in SIRT3−/− liver mitochondria from the total number of acK sites identified. Acetylation profiles of (B) succinate dehydrogenase subunit A (SDHA) from complex II in the ETC, (C) isocitrate dehydrogenase (IDH2) in the TCA cycle, and (D) long-chain specific acyl-CoA dehydrogenase (ACADL) in the fatty acid oxidation pathway. (E) Relative quantitation measurements resulting from SRM analysis of targeted acK sites using stable isotope dilution with synthetic peptide standards to the indicated proteins/acK sites. The most intense fragment ion was used for analysis and compared with MS1 Filtering results. (F) Largest fold changes (KO:WT) for individual acK sites. From left to right, dihydrolipoyllysine succinyltransferase (DLST), enoyl-CoA isomerase (ECI1), ATP synthase subunit O (ATP5O), 3-ketoacyl-CoA thiolase (ACAA2), Glycine N-acyltransferase-like protein (GM4952), malate dehydrogenase (MDH2), enoyl-CoA hydratase (ECHS1), ornithine carbamoyltransferase (OTC), hydroxymethylglutaryl-CoA lyase (HMGCL), and NipSnap homolog 1 (NIPSNAP1). Two-tailed Student t test (*P ≤ 0.05, **P ≤ 0.01); n = 5 for WT and KO with two injection replicates per sample.

Because there have been limited reports of substrates and sites of SIRT3 regulation, we examined our data against that previously reported for succinate dehydrogenase A (SDHA), IDH2, and ACADL. We quantified 21 acK sites in the succinate dehydrogenase complex, a four-subunit enzyme responsible for oxidizing succinate to fumarate and transferring electrons to ubiquinone. No change in acK levels of subunit B was detected (Dataset S4). However, acetylation at K179 on subunit A (SDHA) showed a robust increase in SIRT3−/− mice (Fig. 3B). The other 14 sites on SDHA were unchanged, indicating increased acetylation at K179 was specific for SIRT3 and not due to altered protein expression. These sites confirm our previous results for SDHA in SIRT3−/− mice from skeletal muscle mitochondria (26). In addition, we monitored 21 sites on the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) enzyme IDH2 and 11 sites on the FAO enzyme ACADL (14, 25) (Fig. 3 C and D). Of the 21 sites identified on IDH2, only K360 showed a significant increase in acetylation in SIRT3−/−, whereas K322 on ACADL had increased acetylation.

Verification of MS1 Filtering Results by SRM/MS Analysis.

To independently validate our label-free quantitative results, we developed selected reaction monitoring (SRM) assays for seven acK peptides identified in our study. SRM is sufficiently sensitive to quantify peptides in the low attomole range over a large dynamic range, and when coupled with stable isotope-labeled peptides, can measure absolute concentrations (29). Stable isotope-labeled synthetic peptides corresponding to seven acK peptides identified in our study were analyzed by SRM on a 5500 QTRAP after optimization of assay conditions. Stable isotope-labeled peptides were added to each of five WT and five KO acK-enriched samples for normalization and quantitation and analyzed in duplicate. SRM quantitative analysis shows nearly identical results to those generated using MS1 Filtering (Fig. 3E).

Pathway Analysis of SIRT3 Substrates Reveals Widespread Metabolic Targets with Multiple Sites.

Site-specific changes measured by MS1 Filtering show the largest increase in acK levels for proteins from the TCA cycle [E2 component (DLST) of the α-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase complex and malate dehydrogenase (MDH2)], the electron transport chain [ATP synthase subunit O (ATP5O)], fatty acid oxidation (ECI1, ECHS1, ACAA2), the urea cycle [ornithine carbamoyltransferase (OTC)], and ketogenesis [hydroxmethylglutaryl-CoA lyase (HMGCL)] (Fig. 3F). To gain additional insight into these and other mitochondrial pathways regulated by SIRT3, we performed a pathway enrichment analysis (28) of all SIRT3 targets (Fig. 4A). We found that 71% of proteins involved in fatty acid oxidation (10 of 14 proteins), 43% of proteins in the TCA cycle (10 of 23 proteins), 53% of proteins involved in branched chain amino acid (BCAA) catabolism (10 of 19 proteins), and 80% of proteins involved in ketogenesis (4 of 5 proteins) have increased acK levels in KO mice. Protein expression levels measured in parallel by MS1 Filtering using up to six peptides from nonenriched mitochondrial digests showed minimal changes (Fig. S2; Dataset S5). For example the average KO:WT ratios of MDH2 and OTC were 1.09 and 1.08, respectively. Notably, of the proteins listed in Fig. 4B, only OTC has been previously reported as a substrate for SIRT3 (30, 31). Thus, SIRT3−/− mice show a profound increase in protein acetylation across mitochondrial pathways without significant alteration in protein expression.

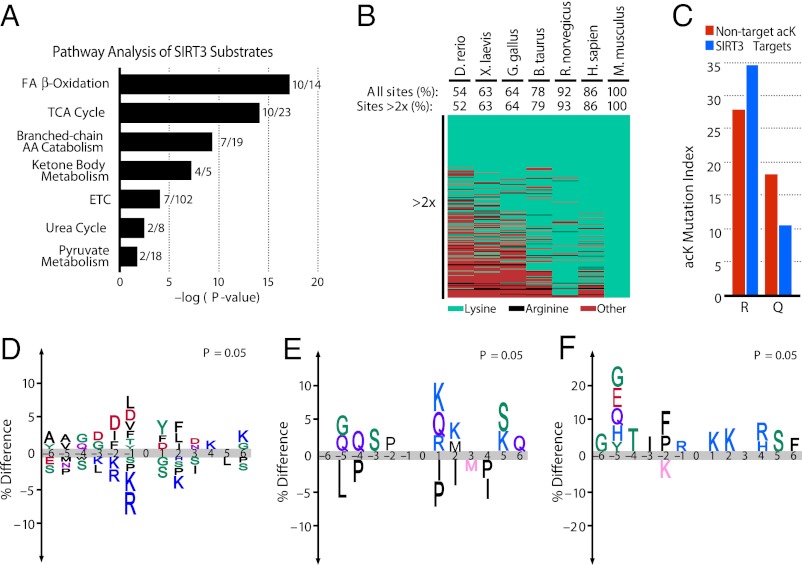

Fig. 4.

Pathway and evolutionary analysis of acetylation sites and consensus motifs. (A) Pathway analysis of the mitochondrial acetylome altered in SIRT3−/− mice with the number of proteins identified per pathway. (B) Heat map depicting the conservation index of SIRT3 substrates (twofold increase) across seven vertebrate species with percent conservation calculated for all acK sites identified and SIRT3 substrates. Conservation index of all nonregulated sites is available in Fig. S3. (C) Percentage of acK residues identified in mouse mutated to arginine (P = 0.01) or glutamine (P = 0.04) across the seven species in Fig. 3B (P values calculated via χ2 test). (D) Consensus sequence logos plot for acetylation sites ± six amino acids from the lysine of all acK sites identified, (E) from the identified lysine residues significantly increased in SIRT3−/− mice, and (F) for highly conserved acetylation sites significantly increased in SIRT3−/− mice.

Conservation of Lysine Acetylation Across Species.

To gain insight into the evolutionary conservation of acK sites regulated by SIRT3, we generated a conservation index across vertebrate proteomes using AL2CO (32). Of the acK sites identified in mice, 87% of lysines were conserved in humans and 54% in Danio rerio (Fig. S3). Among lysines whose acetylation increased in SIRT3−/− mice, 85% were conserved in humans and 51% in Danio rerio (Fig. 4B). Many of the acK sites identified in mouse were mutated to arginine, which has a similar charge to lysine, or to glutamine, which has a similar structure to acetylated lysine and is often used as a mimetic. Notably, targets of SIRT3 are more likely to have mutated to arginine, whereas non–SIRT3-regulated sites are more likely to have mutated to glutamine (Fig. 4C), suggesting selective pressure for maintaining a positively charged residue at sites regulated by SIRT3.

Sequence Motif Analysis of Mitochondrial- and SIRT3-Regulated Acetylation Sites.

To determine whether there is a common sequence motif required for acetylation of mitochondrial proteins, we compared the amino acid sequences of all acetylated and nonacetylated sites using iceLogo (33) (Fig. 4D). A preference was observed for tyrosine at the +1 position and for aspartic acid at positions −1, −2, and −3, whereas positively charged residues are nearly excluded (2, 3, 34). SIRT3 substrates had no partiality to a negative charge preceding the acK site and preferred a positive charge at the +1 position (Fig. 4E). Interestingly, the sequence motif of highly conserved SIRT3 substrates from Fig. 4B showed a stronger preference for K at the +1 and +2 positions (Fig. 4F).

Discussion

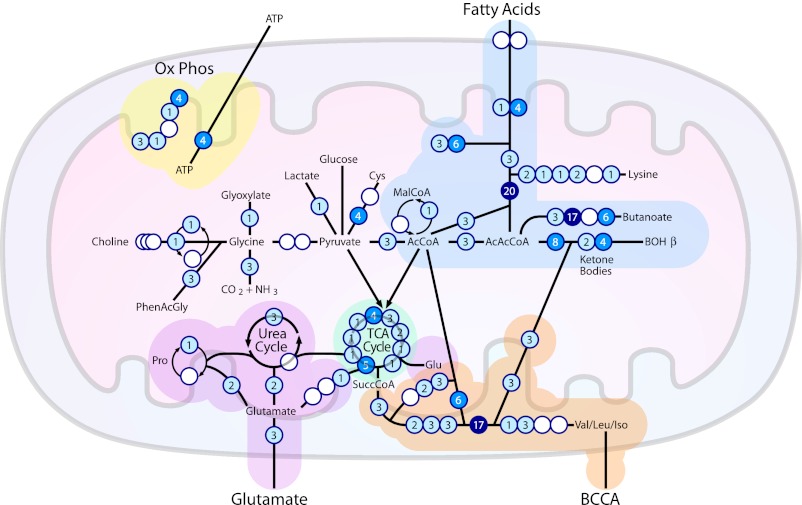

Using a robust acK affinity workflow and label-free quantification, we identified 2,187 unique lysine acetylation sites across 483 proteins from isolated mitochondria, indicating that a majority of the matrix proteins are acetylated. Among acetylated proteins, 61% possess more than one site, suggesting the potential for multiple points of regulation. The absence of SIRT3 in liver leads to the selective hyperacetylation in the fasted mouse at 283 sites, representing 136 of the 483 acetylated mitochondrial proteins (Fig. 5). The largest fold changes in lysine acetylation were observed in key metabolic pathways including ATP synthase involved in oxidative phosphorylation, ECHS1 involved in fatty acid oxidation, OTC in the urea cycle, HMGCL involved in ketogenesis, and MDH2 from the TCA cycle. Last, we demonstrated that changes in acetylation levels were not due to altered protein expression, because quantitative analysis on 350 proteins from total mitochondrial protein hydrolysates was predominantly unchanged in KO mice.

Fig. 5.

Schematic depicting the primary SIRT3 regulated metabolic pathways within mitochondria including oxidative phosphorylation (Ox Phos), fatty acid oxidation, ketogenesis, branched chain amino acid catabolism (BCCA), the TCA cycle, and the urea cycle. Circles represent constituent proteins or protein complexes within each pathway with the number of SIRT3 regulatory sites indicated. Abbreviations include Acetyl-CoA (AcCoA), acetoacetyl-CoA (AcAcCoA), β-hydroxybutyrate (BOHβ), succinyl-CoA (SuccCoA), malonyl-CoA (MalCoA), ammonia (NH3), carbon dioxide (CO2), glutamate (Glu), proline (Pro), valine (Val), leucine (Leu), isoleucine (Iso), cysteine (Cys), adenosine triphosphate (ATP), and phenylacetylglycine (PhenAcGly).

Although acetylation is nearly ubiquitous among mitochondrial proteins, it is not evenly distributed. The pathways involved most directly in production and utilization of acetyl-CoA are heavily acetylated. These pathways are required for maintenance of glucose-poor fasting metabolism: fatty acid oxidation for acetyl CoA production; ketone body synthesis for distribution to other tissues; TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation for generation of ATP from acetyl CoA; amino acid catabolism for generation of TCA cycle intermediates and acetyl CoA; and urea cycle to metabolize nitrogen released by amino acid catabolism. The same pathways are abundant in SIRT3 targets as well, showing how SIRT3 may be a central regulator of mitochondrial adaptation to a fasting metabolic state. Many of these pathways were previously identified as containing a SIRT3 target, but our data show that regulation by SIRT3 is far more comprehensive; for example, every complex in the TCA cycle contains at least one SIRT3 target, as does every enzymatic step leading from fatty acids to the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate (Fig. 5).

We identified three SIRT3-regulated sites on complex I components including NDUFA9 at K370. Previously, NDUFA9 was reported (18) as a SIRT3-interacting protein whose acetylation may reduce activity and decrease basal ATP levels. Additional SIRT3-regulated sites were identified on complex II at K179, one site on complex IV, and four sites on several components of ATP synthase. In the TCA cycle, both the α-ketoglutarate complex (KGDHC) and MDH2 had a ≥20-fold increase in acetylation levels at K153 and K239, respectively. The fact that KGDHC is sensitive to inhibition by oxidative stress (35) and implicated in the pathophysiology of neurodegeneration suggests that acetylation may be a key regulator of these processes (36). Although succinyl CoA synthetase did not have as dramatic an increase in acetylation, this TCA cycle enzyme had five sites with a greater than twofold increase. Interestingly, 40% of SIRT3 target proteins (54 of 136) are regulated at multiple sites, indicating the potential for differential or concerted regulation during fasting. Finally, we observed increased acetylation at 1 of 21 sites on IDH2 (K360). Taken together, our data identify several unique SIRT3-regulated components within the TCA cycle and oxidative phosphorylation pathways.

Proteins involved in fatty acid metabolism also featured prominently. For example, 10 of 14 proteins in the fatty acid oxidation pathway are hyperacetylated at 34 sites in KO mice (Fig. 5; Dataset S4). The most widely regulated SIRT3 substrate was the α-subunit (HADHA) of the trifunctional protein (TFP) complex. HADHA catalyzes two reactions in long-chain acyl-CoA oxidation, and its deficiency leads to hepatic steatosis and sudden death (37). Sixteen of 37 sites of acK on HADHA were significantly increased in SIRT3−/− with no change in protein expression levels, suggesting fine tuning of its regulation through multiple sites of acetylation. ACADL is upstream of TFP and catalyzes the initial step in the breakdown of long-chain acyl-CoAs. Of the proteins involved in fatty acid oxidation, only ACADL was previously reported as a substrate for SIRT3 through regulation at K42 (14). MS1 Filtering showed a 2.1-fold increase in acetylation on ACADL at K322 but no change at K42, which was confirmed by SRM-MS analysis. Taken together, our data suggest SIRT3 regulates acyl-CoA oxidation at multiple points in the pathway for long- and short-chain acyl-CoAs, as well as saturated and unsaturated fatty acids. Indeed, these data support a previous study (14) showing inhibition of the fatty acid oxidation pathway through elevated long-chain acylcarnitine accumulation in liver and plasma and development of hepatic steatosis in SIRT3−/− mice.

The majority of proteins involved in ketone body production had elevated levels of acetylation in SIRT3−/− animals. Mice deficient for SIRT3 were previously shown to have decreased ketone body production and hyperacetylation of HMGCS2 (19). We observed only modest increases in acetylation at K310, K447, and K473 for HMGCS2 in contrast to a previous report (19) that observed robust increases at K46, K83, and K333. To address this discrepancy in HMGCS2, SRM-MS assays were carried out using synthetic peptides that confirmed our MS1 Filtering results. Elevated levels of SIRT3 in the liver during the fasted state may lead to activation of ketogenic enzymes by SIRT3 to meet energetic demands in other tissues.

The BCAA pathway responds to changes in dietary flux when other nutrient sources become limited to maintain energy homeostasis. It is not surprising, therefore, that the acetylation of several proteins from the BCAA pathway was found to increase significantly in the SIRT3−/− mouse. Methylglutaconyl-CoA hydratase (AUH), which catalyzes the breakdown of 3-methylglutaconyl-CoA to 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA, showed moderate to robust increases in acetylation levels at K47, K119, and K304. Likewise, the E2 subunit of the branched-chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase complex, whose deficiency causes maple syrup urine disease, was also hyperacetylated at three sites including K82 within the lipoyl binding domain, suggesting a likely regulation by SIRT3 of the activity of this protein as well and multiple regulated steps in this pathway. The increase in acetylation among enzymes of the BCAA pathway is consistent with the previously reported small increase in BCAAs in the SIRT3 mouse liver, assuming acetylation leads to a decrease in enzymatic activity (14).

SIRT3 is not simply a global deacetylase, because some proteins such as CPS1 and GDH are widely acetylated yet have few SIRT3-regulated sites. CPS1, which catalyzes the synthesis of carbamoyl phosphate from glutamine in the urea cycle, was hyperacetylated at only 2 of 70 acK sites in the KO mouse. Such a large difference suggests that SIRT3 is selective, even for proteins that are extensively acetylated. Conversely, some proteins such as Lon peptidase and the Ts translation elongation factor have a very small number of acetylation sites, yet the majority are SIRT3 regulated. In contrast, HADHA was found to be both highly acetylated (37 sites) and highly regulated, with almost half (16 sites) identified as SIRT3 targets. Thus, SIRT3 appears to target specific lysines among highly acetylated proteins involved in adaptation to fasting metabolism while also having some apparently idiosyncratic targets that may be related more generally to mitochondrial maintenance.

We investigated the conservation of SIRT3-regulated sites across several vertebrate proteomes. Surprisingly, sites regulated by SIRT3 were no more highly conserved than acK sites unchanged in the KO mouse, nor was there a significant conservation of SIRT3 regulated sites in a given pathway. However, there was a noticeable preference towards maintaining a positively charged amino acid at SIRT3-regulated acK sites. Although highly conserved sites provided a greater understanding of the SIRT3-regulated acK motif, it did not dramatically improve our ability to predict a SIRT3 consensus sequence. Thus, SIRT3 may be promiscuous in its primary sequence selectivity, and site-specific regulation may be due to other factors such as solvent accessibility or tertiary structure. In addition, the significance of the non–SIRT3-regulated acetylation sites remains unclear given the absence of alternative mitochondrial deacetylases. Combined with the lack of a clearly identified mitochondrial acetyltransferase(s), acetylation may be derived from nonenzymatic processes due to the high pH (∼7.9) and high concentration of AcCoA (∼5 mM) in this organelle, although no differences were reported in AcCoA levels in the liver of SIRT3 KO mice (38).

Although our experimental approach measures the relative level of acetylation at a given site in the presence and absence of SIRT3, it does not use absolute criteria in identifying (or excluding) a SIRT3-regulated site nor does it use information on stoichiometry. Our threshold of at least twofold (P ≤ 0.01) for a SIRT3-regulated site was chosen primarily to have a low FDR (<0.05), thus ensuring the integrity of the proteome-wide data set. The lack of stoichiometry information presents different challenges. For example, sites that are ≥50% acetylated under basal conditions would not achieve a twofold increase in acetylation. Alternatively, sites at very low levels of acetylation present a problem of biological relevance. However, proteomic experiments carried out without enrichment identify very few acetylation sites, consistent with low to moderate levels of lysine acetylation. Nonetheless, defining the precise stoichiometry of acetylation at individual sites is clearly needed to answer these questions, a process that is currently limited by a lack of robust methodology despite some limited success reported for histones (39).

Although SIRT3 is the predominant mitochondrial deacetylase, recent work has shown SIRT5 to have both lysine desuccinylase and demalonylase activities (10, 11). Proteomic studies identified lysine malonylation of MDH2, GDH, and ADP/ATP translocase 2 that overlap with acK sites identified here (10, 11). Similarly, lysine succinylation was identified on GDH, MDH2, citrate synthase, and HMGCS2 at SIRT3-regulated acK sites (10). Therefore, cross-talk among the different types of lysine acylation in mitochondria may provide complex avenues of regulation similar to that of histone modifications (40).

Conclusion

In summary, we combined a unique label-free quantitative proteomic approach with efficient enrichment of lysine acetylated peptides to identify the SIRT3-regulated acetylome in liver mitochondria. Using a SIRT3−/− mouse model, we identified 283 sites among 136 proteins as SIRT3-specific substrates. Moreover, we independently validated a subset of these peptides using SRM-MS, demonstrating the accuracy of our results. Our data showed broad regulation of multiple proteins and sites across several key mitochondrial pathways involved in nutrient signaling and energy homeostasis. Proteins involved in regulating fatty acid oxidation were particularly targeted by SIRT3 and indicate the potential for regulation during changes in nutrient availability. Surprisingly, a large disparity can exist between the extent of lysine acetylation in a given protein and those sites that are regulated by SIRT3, as demonstrated by CPS1 and HADHA. However, the majority of the 2,187 acetylated sites we identified did not appear to be regulated by SIRT3, suggesting many of these sites may have little or no functional consequence or simply failed to meet our rigorous inclusion threshold. Although our study was designed to be comprehensive, technical and sampling limitations may have limited its completeness. Nonetheless, our large-scale inventory of acetylated proteins and sites in the liver mitochondria significantly expands our understanding of how SIRT3 may regulate mitochondrial function and represents an important step toward elucidating the role of SIRT3 in the liver and other tissues. Future studies will need to address the stoichiometry of acetylation at different sites, possible competition between different acyl modifications, and the functional role of acetylation on protein function under normal and pathological conditions.

Materials and Methods

The experimental workflow of acK peptide enrichment from mitochondria and their MS analysis and quantitation by MS1 Filtering are briefly outlined in Fig. 1 and in Results. Additional information on organelle enrichment, antibodies, chemicals, protein preparation, immunoprecipitation of acK peptides, determination of conservation, experimental MS parameters, label-free quantitation by MS1 Filtering, and SRM are provided in SI Materials and Methods and Dataset S6. All acK peptide spectra are available for viewing online at https://skyline.gs.washington.edu:9443/labkey/project/Gibson/Gibson_Reviewer/begin.view?.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants T32AG000266 (to M.J.R.), PL1 AG032118 (to B.W.G.), and R24 DK085610 (to E.V.). This work was also supported in part by the Shared Instrumentation Grant S10 RR024615 (to B.W.G.) and the generous access of a TripleTOF 5600 by AB SCIEX at the Buck Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data deposition: The raw mass spectrometry data files have been deposited using an FTP site hosted at the Buck Institute, ftp://sftp.buckinstitute.org/Gibson.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1302961110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Glozak MA, Sengupta N, Zhang X, Seto E. Acetylation and deacetylation of non-histone proteins. Gene. 2005;363:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim SC, et al. Substrate and functional diversity of lysine acetylation revealed by a proteomics survey. Mol Cell. 2006;23(4):607–618. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choudhary C, et al. Lysine acetylation targets protein complexes and co-regulates major cellular functions. Science. 2009;325(5942):834–840. doi: 10.1126/science.1175371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.DiMauro S, Schon EA. Mitochondrial respiratory-chain diseases. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(26):2656–2668. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beal MF. Mitochondria take center stage in aging and neurodegeneration. Ann Neurol. 2005;58(4):495–505. doi: 10.1002/ana.20624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schwer B, Verdin E. Conserved metabolic regulatory functions of sirtuins. Cell Metab. 2008;7(2):104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schwer B, North BJ, Frye RA, Ott M, Verdin E. The human silent information regulator (Sir)2 homologue hSIRT3 is a mitochondrial nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide-dependent deacetylase. J Cell Biol. 2002;158(4):647–657. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200205057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Michishita E, Park JY, Burneskis JM, Barrett JC, Horikawa I. Evolutionarily conserved and nonconserved cellular localizations and functions of human SIRT proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(10):4623–4635. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lombard DB, et al. Mammalian Sir2 homolog SIRT3 regulates global mitochondrial lysine acetylation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(24):8807–8814. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01636-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Du J, et al. Sirt5 is a NAD-dependent protein lysine demalonylase and desuccinylase. Science. 2011;334(6057):806–809. doi: 10.1126/science.1207861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peng C, et al. 2011. The first identification of lysine malonylation substrates and its regulatory enzyme. Mol Cell Proteomics 10(12):M111012658.

- 12.Haigis MC, et al. SIRT4 inhibits glutamate dehydrogenase and opposes the effects of calorie restriction in pancreatic beta cells. Cell. 2006;126(5):941–954. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwer B, et al. Calorie restriction alters mitochondrial protein acetylation. Aging Cell. 2009;8(5):604–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00503.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hirschey MD, et al. SIRT3 regulates mitochondrial fatty-acid oxidation by reversible enzyme deacetylation. Nature. 2010;464(7285):121–125. doi: 10.1038/nature08778. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jing E, et al. Sirtuin-3 (Sirt3) regulates skeletal muscle metabolism and insulin signaling via altered mitochondrial oxidation and reactive oxygen species production. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(35):14608–14613. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111308108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cimen H, et al. Regulation of succinate dehydrogenase activity by SIRT3 in mammalian mitochondria. Biochemistry. 2010;49(2):304–311. doi: 10.1021/bi901627u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finley LW, et al. Succinate dehydrogenase is a direct target of sirtuin 3 deacetylase activity. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(8):e23295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ahn BH, et al. A role for the mitochondrial deacetylase Sirt3 in regulating energy homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(38):14447–14452. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803790105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shimazu T, et al. SIRT3 deacetylates mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl CoA synthase 2 and regulates ketone body production. Cell Metab. 2010;12(6):654–661. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen Y, et al. Tumour suppressor SIRT3 deacetylates and activates manganese superoxide dismutase to scavenge ROS. EMBO Rep. 2011;12(6):534–541. doi: 10.1038/embor.2011.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qiu X, Brown K, Hirschey MD, Verdin E, Chen D. Calorie restriction reduces oxidative stress by SIRT3-mediated SOD2 activation. Cell Metab. 2010;12(6):662–667. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tao R, et al. Sirt3-mediated deacetylation of evolutionarily conserved lysine 122 regulates MnSOD activity in response to stress. Mol Cell. 2010;40(6):893–904. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell EL, Emerling BM, Ricoult SJ, Guarente L. SirT3 suppresses hypoxia inducible factor 1α and tumor growth by inhibiting mitochondrial ROS production. Oncogene. 2011;30(26):2986–2996. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Finley LW, et al. SIRT3 opposes reprogramming of cancer cell metabolism through HIF1α destabilization. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(3):416–428. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Someya S, et al. Sirt3 mediates reduction of oxidative damage and prevention of age-related hearing loss under caloric restriction. Cell. 2010;143(5):802–812. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schilling B, et al. Platform-independent and label-free quantitation of proteomic data using MS1 extracted ion chromatograms in skyline: Application to protein acetylation and phosphorylation. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2012;11(5):202–214. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M112.017707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang H, et al. 2011. Methods for peptide and protein quantitation by liquid chromatography-multiple reaction monitoring mass spectrometry. Mol Cell Proteomics 10(6):M110006593.

- 28.Croft D, et al. Reactome: a database of reactions, pathways and biological processes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39(Database issue):D691–D697. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gerber SA, Rush J, Stemman O, Kirschner MW, Gygi SP. Absolute quantification of proteins and phosphoproteins from cell lysates by tandem MS. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(12):6940–6945. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0832254100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hallows WC, et al. Sirt3 promotes the urea cycle and fatty acid oxidation during dietary restriction. Mol Cell. 2011;41(2):139–149. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yu W, et al. Lysine 88 acetylation negatively regulates ornithine carbamoyltransferase activity in response to nutrient signals. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(20):13669–13675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M901921200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pei J, Grishin NV. AL2CO: Calculation of positional conservation in a protein sequence alignment. Bioinformatics. 2001;17(8):700–712. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/17.8.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Colaert N, Helsens K, Martens L, Vandekerckhove J, Gevaert K. Improved visualization of protein consensus sequences by iceLogo. Nat Methods. 2009;6(11):786–787. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1109-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lundby A, et al. Proteomic analysis of lysine acetylation sites in rat tissues reveals organ specificity and subcellular patterns. Cell Rep. 2012;2(2):419–431. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tretter L, Adam-Vizi V. Inhibition of Krebs cycle enzymes by hydrogen peroxide: A key role of [alpha]-ketoglutarate dehydrogenase in limiting NADH production under oxidative stress. J Neurosci. 2000;20(24):8972–8979. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-08972.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gibson GE, Blass JP, Beal MF, Bunik V. The alpha-ketoglutarate-dehydrogenase complex: A mediator between mitochondria and oxidative stress in neurodegeneration. Mol Neurobiol. 2005;31(1-3):43–63. doi: 10.1385/MN:31:1-3:043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ibdah JA, et al. Lack of mitochondrial trifunctional protein in mice causes neonatal hypoglycemia and sudden death. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(11):1403–1409. doi: 10.1172/JCI12590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirschey MD, et al. SIRT3 deficiency and mitochondrial protein hyperacetylation accelerate the development of the metabolic syndrome. Mol Cell. 2011;44(2):177–190. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Smith CM, et al. Mass spectrometric quantification of acetylation at specific lysines within the amino-terminal tail of histone H4. Anal Biochem. 2003;316(1):23–33. doi: 10.1016/s0003-2697(03)00032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Latham JA, Dent SY. Cross-regulation of histone modifications. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14(11):1017–1024. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.