Abstract

Among its many functions, the ubiquitin–proteasome system regulates substrate-specific proteolysis during the cell cycle, apoptosis, and fertilization and in pathologies such as Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, and liver cirrhosis. Proteasomes are present in human and boar spermatozoa, but little is known about the interactions of proteasomal subunits with other sperm proteins or structures. We have created a transgenic boar with green fluorescent protein (GFP) tagged 20S proteasomal core subunit α-type 1 (PSMA1-GFP), hypothesizing that the PSMA1-GFP fusion protein will be incorporated into functional sperm proteasomes. Using direct epifluorescence imaging and indirect immunofluorescence detection, we have confirmed the presence of PSMA1-GFP in the sperm acrosome. Western blotting revealed a protein band corresponding to the predicted mass of PSMA1-GFP fusion protein (57 kDa) in transgenic spermatozoa. Transgenic boar fertility was confirmed by in vitro fertilization, resulting in transgenic blastocysts, and by mating, resulting in healthy transgenic offspring. Immunoprecipitation and proteomic analysis revealed that PSMA1-GFP copurifies with several acrosomal membrane-associated proteins (e.g., lactadherin/milk fat globule E8 and spermadhesin alanine-tryptophan-asparagine). The interaction of MFGE8 with PSMA1-GFP was confirmed through cross-immunoprecipitation. The identified proteasome-interacting proteins may regulate sperm proteasomal activity during fertilization or may be the substrates of proteasomal proteolysis during fertilization. Proteomic analysis also confirmed the interaction/coimmunoprecipitation of PSMA1-GFP with 13/14 proteasomal core subunits. These results demonstrate that the PSMA1-GFP was incorporated in the assembled sperm proteasomes. This mammal carrying green fluorescent proteasomes will be useful for studies of fertilization and wherever the ubiquitin–proteasome system plays a role in cellular function or pathology.

There has been growing acceptance of the essential role of the ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) in many aspects of the fertilization process in mammals, lower vertebrates, and invertebrates (reviewed by refs. 1–3). Sperm capacitation, acrosomal exocytosis, sperm binding to and penetration through the zona pellucida, and degradation of the sperm-borne mitochondria and mtDNA inside the zygote all involve proteasomal proteolysis in mammals (4–6). Multiple laboratories have reported the presence and involvement of sperm-borne proteasomes in human, mouse, porcine, bovine, avian, ascidian, and echinoderm (5, 7–11). Sperm-borne proteasomes and associated enzymes have been detected in the cytosol/matrix of the acrosome and bound to the inner and outer acrosomal membranes of the sperm head (5, 7, 12–14). Proteasome-specific proteolytic and deubiquitinating activities have been measured in live, intact spermatozoa by using specific fluorometric substrates (5, 15). Fertilization has been shown to rely on proteasomal proteolysis by the application of a variety of proteasome-specific inhibitors and antibodies (7, 12, 16–18). Phosphoproteome studies detected many UPS proteins undergoing phosphorylation during sperm capacitation and acrosome reaction in the mouse, boar, and rat (2, 19, 20).

The UPS tags outlived or damaged intracellular proteins through a multistep process with a small chaperone protein ubiquitin (8.5 kDa) that targets them for degradation by the 26S proteasome, a multisubunit protease (21). A substrate protein first is marked for degradation by the covalent attachment of a single 76-amino acid ubiquitin molecule. Subsequent ubiquitin molecules are covalently attached, typically to the K48 or K63 residue of the previous ubiquitin molecule through a series of enzymatic reactions. This process is initiated by the activation of an unconjugated monoubiquitin with phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 (UBE1). UBE1 then is replaced with ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2. Simultaneously, the targeted substrate protein is located and secured by ubiquitin ligase E3, which is the enzyme responsible for substrate specificity of protein ubiquitination. The E3 ligase catalyzes the covalent binding of the C-terminal Gly residue (G76) of ubiquitin to an internal Lys residue of the substrate protein. Subsequently, tandem ligation of additional ubiquitin molecules results in the formation of a multiubiquitin chain (four or more ubiquitin molecules) that makes the substrate protein recognizable to the PSMD4 subunit of the 19S regulatory complex of the 26S proteasome.

The canonical 26S proteasome is a large cylindrical multisubunit protease containing a 20S core catalytic particle capped at one or both ends by a 19S regulatory particle. The 20S core is composed of 28 subunit molecules of 14 different kinds, arranged in four heptamerically stacked rings in an α7β7β7α7 pattern. The inner two β rings each contain seven β-type/PSMB subunits, three of which have active protease sites responsible for proteolysis. Subunit β1/PSMB6 has a caspase-like peptidase activity, subunit β2/PSMB7 has a trypsin-like peptidase activity, and subunit β5/PSMB5 displays a chymotrypsin-like peptidase activity (8, 22). The α-type subunits connect the 20S core to the 19S regulatory particle and have no known protease activity; however, some are reported to have RNase/endonuclease activities (reviewed by ref. 23). The 19S regulatory particle contains 19 subunits divided between the lid and base subcomplexes. The lid contains up to 14 non-ATPase subunits (PSMD1–14) that recognize the polyubiquitin chain linked to the target protein, which then is removed by the Rpn11/PSMD14 subunit’s deubiquitinating activity. The base contains six ATPase subunits (Rpt1–6/PSMC1–6) that unfold and translocate the substrate protein and regulate proteasome activity (22).

Little is known about the interactions of specific proteasomal subunits with proteasome-interacting proteins (PIPs) and the mechanisms behind these proteasome-dependent events. To give insight into the identity of these PIPs and their mechanisms during fertilization, a transgenic boar was created carrying the fluorescently tagged 20S core particles with the enhanced green fluorescent protein (GFP) fused to the proteasomal subunit α-6/PSMA1 (PSMA1-GFP transgene). The purpose of this study is to report the localization and subunit composition of the sperm-borne proteasomes, and to promote the use of this unique transgenic pig model in the investigation of the cellular mechanism and pathologies associated with the function or dysfunction of UPS, respectively. By using the transgenic boar spermatozoa for epifluorescence, immunofluorescence, Western blotting, immunoprecipitation, and tandem mass spectrometry (MS/MS), we provide evidence that the subunits of the sperm acrosome-borne proteasomes interact with acrosomal membrane proteins that may anchor proteasomes to the acrosomal structures and/or depend on proteasomes for their function during fertilization. These results might provide insight into the proteasome-dependent mechanisms behind the UPS’s role in fertilization and encourage the use of this unique transgenic boar model for the study of the UPS in all areas of research (fertilization, neurodegenerative disorders, and genetic diseases).

Results

Creation and Validation of the PSMA1-GFP Transgenic Pig.

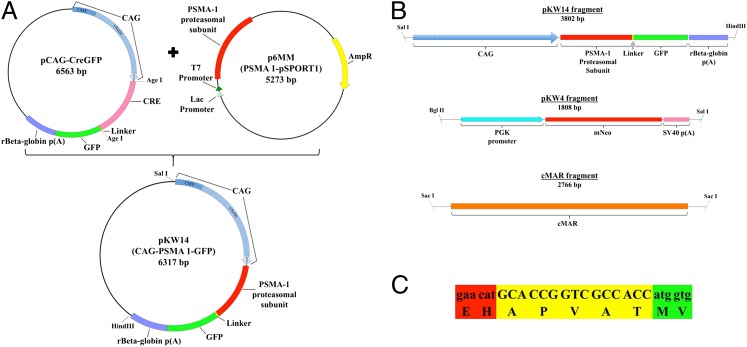

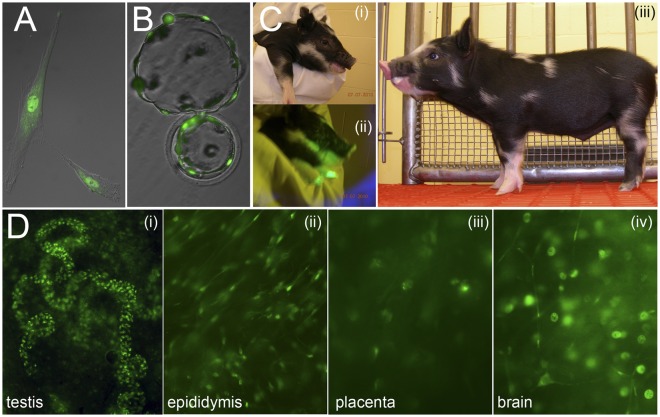

To create a transgene-carrying proteasomal subunit PSMA1 fused to the GFP, a porcine PSMA1 sequence was assembled in silico from public data and used to identify an EST that appeared to be full length (GenBank accession no. CO946059). Primers were designed to remove the stop codon and create homology for cloning with In-Fusion (Clontech). The CO946059 amplimer was inserted into pCAG-CreGFP (Addgene, 13776) replacing the Cre coding region (Fig. 1A). The resulting plasmid (pKW14) was functionally validated in porcine fetal fibroblasts. After insert purification, GFP-PSMA1, a selectable marker, and the chicken egg-white matrix attachment region (Fig. 1 B and C) were coelectroporated into male fetal fibroblasts (10 µg total DNA; 5:2:2 ratio, respectively). Transfected cells were cultured in DMEM (10% FBS) for 12 d in 400 mg/L G418, during which time they developed a diffuse cytoplasmic and concentrated nuclear fluorescence of GFP (Fig. 2A). Embryos were reconstructed from pooled integration events via somatic cell nuclear transfer (Fig. 2B) and transferred to two surrogates (120–125 clones per surrogate). Two females delivered two piglets each on day 114 by caesarean section. One live piglet was produced from each litter. One male piglet survived beyond day 3 and reached adulthood; this piglet became the founder piglet of our PSMA1-GFP line. A third surrogate delivered a litter of five piglets, but the four surviving piglets did not harbor the transgene. Expression of PSMA1-GFP initially was confirmed by black light exposure of the founder piglet (Fig. 2C) and by epifluorescence imaging of the reproductive and other tissues collected from stillborn transgenic siblings (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 1.

(A) pKW14 plasmid construction. Cre was removed from pCAG-CreGFP using AgeI restriction sites, and used as vector backbone. Generation of the insert was done via PCR. Primers were designed to amplify the PSMA1 coding region from p6MM, to remove the stop codon, and to create a homology for cloning with In-Fusion (Clontech). (B) Linearized DNA fragments used for cotransfection of porcine fetal fibroblasts. pKW14 (PSMA1-GFP), pKW4 (mNeo, selectable marker), and cMAR (insulator). (C) Sequence of the linker used between the PSMA1 proteasomal subunit and GFP. The linker sequence (yellow) is flanked upstream by PSMA1 (red) and downstream by GFP (green), corresponding to B.

Fig. 2.

(A) Donor cell fibroblast expressing the PSMA1-GFP fusion protein; note the accumulation of GFP fluorescence in the nucleus. (B) Hatching in vitro blastocyst on day 6, obtained by nuclear transfer from the donor cell fibroblast line shown in A. (C) Minnesota miniature pig cloned from fetal fibroblasts expressing GFP-labeled proteasomes, the founder of the PSMA1-GFP line. (C, i and ii) Sequential photographs of the head taken with conventional (i) and black light (ii) illumination. (C, iii) The whole body photographed at 2 wk of age. (D) PSMA1-GFP fluorescence in various tissues collected from newborn positive clones. Prominent green fluorescence is seen in the spermatogonia within the newborn seminiferous tubules (D, i), in the principal cells of the epididymis (D, ii), in the placental cell nuclei (D, iii), and in the nuclei and axons of some of the neurons in the brain (D, iv).

Fertility Testing of the Founder Boar and Its Progeny.

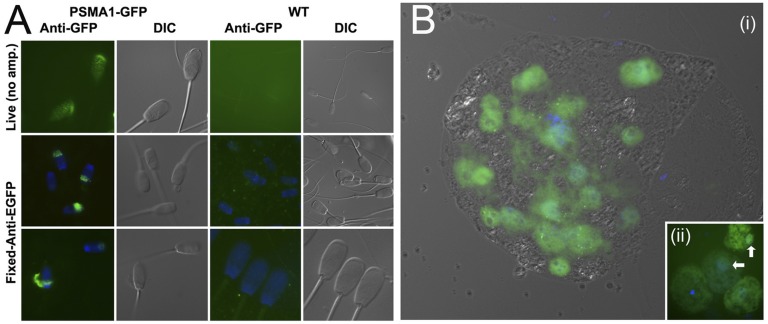

Upon reaching puberty, the transgenic founder boar was trained for semen collection and mated with fertile gilts to develop the PSMA1-GFP line available through the National Swine Resource and Research Center (NSRRC; www.nsrrc.missouri.edu). Epifluorescence imaging revealed GFP fluorescence in the sperm head acrosomal region of live spermatozoa (Fig. 3A), which was confirmed further by amplification with a monoclonal anti-GFP antibody in the fixed and permeabilized spermatozoa (Fig. 3A). Histology of the adult transgenic boar gonads revealed normal testicular and epididymal tissue architecture, normal spermatogenesis in the testis, and abundant spermatozoa within the epididymal tubule lumen (SI Appendix, Fig. 1 A and B). Analysis of adult spermatids and spermatocytes revealed the accumulation of GFP-PSMA1 in the hotspots of proteasomal degradation, such as the nucleus, caudal manchette, acrosomal cap, and cytoplasmic droplet (SI Appendix, Fig. 1 C and D). Localization of a proteasomal subunit to the chromatoid body was observed. In vitro fertilization (IVF) was performed successfully by using semen from the founder as well as from one of his transgenic sons: a wild-type boar used as a control. The semen characteristics of transgenic offspring were examined after semen collection (SI Appendix, Table 1). The sperm concentration and motility of PSMA1-GFP offspring were significantly lower than those of the wild-type boar (P < 0.05) (SI Appendix, Table 2), but there was no significant difference in monospermic fertilization (polyspermy was significantly lower; P < 0.05; SI Appendix, Table 3). Proteasomal–proteolytic activities of transgenic spermatozoa were comparable with those of wild-type spermatozoa, whereas the deubiquitinating activity associated with transgenic spermatozoa was slightly lower than that of the wild type (SI Appendix, Fig. 2). The percentage of cleaving oocytes was higher in the wild-type boar (P < 0.05). Although there was no significant difference in blastocyst rate, the mean cell number per blastocyst was significantly higher in the transgenic offspring (P < 0.05; SI Appendix, Table 4). Consistent with the onset of maternal–embryonic transition of the control of gene expression, the expression of PSMA1-GFP first was observed at late two-cell and four-cell embryos, and increased to the blastocyst stage (Fig. 3B). Consequently, we could confirm that the male of GFP offspring is fertile by IVF trials. This founder male subsequently transmitted the transgene to offspring via artificial insemination.

Fig. 3.

(A) GFP fluorescence in live spermatozoa imaged directly under epifluorescence illumination (Top) and in the fixed spermatozoa processed with anti-GFP antibody (Middle and Bottom); spermatozoa from a wild-type boar (WT) served as a negative control. (B) GFP fluorescence is strongest in the nuclei of a live day 6 blastocyst created by in vitro fertilization of wild-type oocytes with spermatozoa from a GFP boar (homozygous son of the PSMA1-GFP line founder). (Inset) Onset of PSMA1-GFP gene expression at the four-cell stage, coinciding with the major MZT of transcription control.

Characterization of Transgenic Spermatozoa.

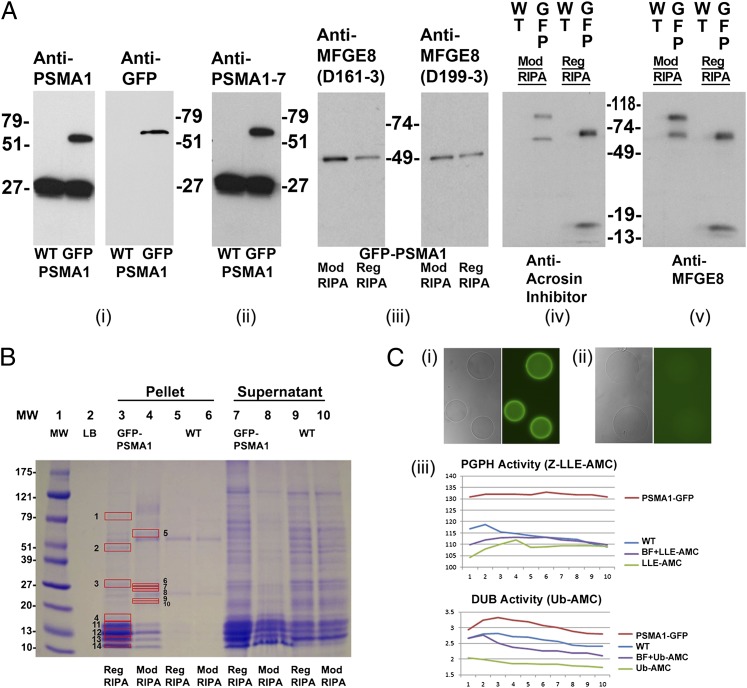

Western blotting was used to establish the successful fusion of the GFP to the PSMA1 protein in the transgenic boar spermatozoa. Semen samples from a fertile wild-type boar and the transgenic, PSMA1-GFP boar were processed for Western blotting experiments (Fig. 4). Mouse monoclonal anti-GFP antibodies from two different purveyors, anti-PSMA1 antibody, and an antibody recognizing the conserved domain shared by 20S core α-type subunits 1–7 (anti-PSMA1–7) were used to confirm the presence of the PSMA1-GFP fusion protein in the transgenic boar spermatozoa (Fig. 4 A, i and ii). The anti-GFP antibody revealed a single band of ∼57 kDa specific to transgenic boar spermatozoa, with no corresponding band in wild-type boar spermatozoa. The migration pattern of this band corresponds to the calculated mass of the PSMA1-GFP fusion protein (263-aa residues PSMA1 + 238-aa residues GFP). This band also corresponds to PAGE protein band identified as PSMA1-GFP fusion protein by MS/MS (SI Appendix, Table 5A and Fig. 4B). The anti-PSMA1 (Fig. 4 A, i) and anti-PSMA1–7 antibodies (Fig. 4 A, ii) also revealed a 57-kDa band unique to transgenic boar spermatozoa, in addition to the anticipated wild-type PSMA1 band at 25–27 kDa. A larger group of proteins also was detected in the 27–30-kDa range for both wild-type and transgenic boar sperm, corresponding to the calculated masses of α-type subunits PSMA1–7. Based on the comparison of band densities, it is concluded that transgenic boar spermatozoa carried the PSMA1-GFP fusion protein as well as the more abundant wild-type PSMA1 protein.

Fig. 4.

Proteomic analysis of PSMA1-GFP fusion protein and the coimmunoprecipitated proteins in the transgenic spermatozoa. (A) A unique band of ∼57 kDa, corresponding to the calculated mass of PSMA1-GFP, is detected in the sperm extracts of the transgenic boar (GFP lane), but not in those from a wild-type boar (WT lane) (A, i). Anti-PSMA1 antibody detected both the wild-type PSMA1 band of ∼27 kDa and the PSMA1-GFP fusion protein of ∼57 kDa (A, i, Left), whereas the anti-GFP antibody detected the PSMA1-GFP band in the transgenic boar only (A, i, Right). A polyclonal antibody recognizing six of seven 20S proteasomal core α-type/PSMA subunits confirms the presence of PSMA1-GFP in the transgenic boar and of the six wild-type PSMA subunits, all of which comigrate in the 25–30-kDa range in both WT and transgenic spermatozoa (A, ii). Western blotting was used to confirm the coimmunoprecipitation of lactadherin MFGE8 with sperm proteasomes from transgenic sperm extracts, using two different anti-MFGE8 antibodies, D161-3 and D199-3 (A, iii). Spermatozoa were lysed with regular RIPA buffer (Reg RIPA) or modified RIPA buffer (Mod RIPA), immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibodies, and probed with anti-MFGE8 antibodies. A single 51-kDa band was revealed in each lane and corresponds to the calculated mass of MFGE8. A modified RIPA buffer (Nonidet P-40) was included because the regular RIPA buffer (Triton X-100) may disrupt some protein–protein interactions. A cross-precipitation experiment was performed to confirm the interaction of MFGE8 (one of the identified interacting proteins from the proteomics results shown in B) with GFP-tagged proteasomes. Wild-type and transgenic boar spermatozoa were lysed with regular or modified RIPA buffer and immunoprecipitated with anti-MFGE8 antibodies (A, iv). The precipitations then were probed with anti-GFP antibodies. Bands were revealed in all transgenic boar lanes, with no bands detected in the wild-type lanes. (B) Band patterns of the putative proteasome-interacting proteins coimmunoprecipitated from the transgenic boar spermatozoa by using an anti-GFP antibody. Wild-type boar and transgenic boar spermatozoa were solubilized with RIPA or modified RIPA buffer and then immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibodies. Red boxes mark proteins unique to transgenic boar sperm that were analyzed by MS. Protein numbers correspond to the protein numbers in SI Appendix, Table 5B. (C) Affinity purification of the enzymatically active green fluorescent proteasomes. The GFP purification matrix beads show high fluorescence intensity after incubation with the PSMA1-GFP sperm extracts (C, i); there is no fluorescence in the beads incubated with the wild-type sperm extract (C, ii). Both types of beads were photographed at an identical magnification and acquisition time. (C, iii) Proteasomal PGPH activity (Upper; measured using the fluorometric proteasomal substrate Z-LLE-AMC) and deubiquitinating activity [Lower; measured by fluorometric substrate ubiquitin (Ub)-AMC] in the eluted fraction from beads incubated with PSMA1-GFP sperm extracts (PSMA1-GFP), in the eluted fraction from beads incubated with wild-type sperm extract (WT), in the assay solution including elution buffer and fluorometric substrate (BF+LLE-AMC or BF+Ub-AMC), or in the assay solution containing only the fluorometric substrate (Z-LLE-AMC or Ub-AMC). Proteasomal activities were measured every 2 min for 20 min.

Identification of Sperm Proteins That Copurify with PSMA1-GFP.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) was used to identify the sperm-associated proteins interacting with the PSMA1-GFP protein, including proteins of spermatogenic origin and proteins adhering to the sperm surface that originate from epididymal fluid or seminal plasma. Semen from a fertile wild-type boar and the transgenic, PSMA1-GFP boar were processed for immunoprecipitation experiments. Anti-GFP antibodies were used to immunoprecipitate the PSMA1-GFP protein and to coimmunoprecipitate possible interacting proteins. The transgenic boar sperm extracts were prepared with two different variants of extortion buffer; wild-type semen not carrying GFP was used as a negative control. The putative PSMA1-interacting protein bands then were resolved on PAGE (Fig. 4B), excised, and submitted for proteomic analysis by MS/MS. As anticipated, proteomics confirmed the presence of the PSMA1-GFP fusion protein and identified most of the coimmunoprecipitated 20S proteasomal core subunit α-type 1, 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7 and β-type 2, 5, 6, and 7, and isoforms of α-type 3, 4, and 7 and β-type 2 (SI Appendix, Table 5A; peptide coverage also shown in SI Appendix, Table 5B). This shows that the PSMA1-GFP fusion protein was incorporated into fully assembled 20S proteasomes. Additional proteins identified as possible interacting proteins of 20S core, or substrates of proteasomal proteolysis, included predominantly the known acrosomal membrane proteins (e.g., lactadherin/milk fat globule E8 (MFGE8) and spermadhesin alanine-tryptophan-asparagine (AWN); complete list in SI Appendix, Table 5B). This list of proteins supports the acrosomal origin of immunoprecipitated 20S proteasomes and corroborates the live GFP imaging and immunolocalization data. Importantly, only two weak protein bands were found in immunoprecipitates of wild-type spermatozoa lacking the PSMA1-GFP fusion protein even though the same IP method, protein load, and antibodies were used (Fig. 4B). The band patterns of immunoprecipitated wild-type and transgenic sperm proteins were identical in multiple repeats of IP procedure.

The most prevalent protein identified among known acrosomal proteins was lactadherin MFGE8 because of its high score of 1,264 and high sequence coverage of 74% (SI Appendix, Table 5B). Western blotting was used to confirm MFGE8’s presence in transgenic boar spermatozoa. Two different anti-MFGE8 antibodies (D161-3 and D199-3) were used, and both revealed a 51-kDa band corresponding to the calculated mass of MFGE8 (Fig. 4 A, iii). Acrosin inhibitor serine protease inhibitor kazal-type 2 (SPINK2) was another prominent acrosomal protein with a significant score and percent coverage that coimmunoprecipitated with PSMA1-GFP. To confirm the interaction of MFGE8 with the PSMA1-GFP protein, cross-immunoprecipitation trials were performed. Wild-type and transgenic boar sperm extracts were immunoprecipitated with anti-MFGE8 antibodies, resolved by PAGE at identical protein loads, transferred, and probed with anti-GFP antibody (Fig. 4 A, iv). This cross-precipitation assay revealed the anticipated PSMA1-GFP band of ∼57 kDa. Based on extraction buffer variant, one additional GFP-immunoreactive band was observed in the transgenic immunoprecipitates at ∼15 kDa [regular radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer (RIPA) extraction] or ∼100 kDa (modified RIPA). No GFP bands were observed in the control wild-type immunoprecipitates at a protein load identical to the transgene (Fig. 4 A, iv). Altogether, proteomic analysis confirmed the incorporation of PSMA1-GFP subunit in the assembled 20S proteasomes and identified several potential proteasome-interacting proteins/proteasomal substrates in the sperm acrosome.

The affinity purification method described above was modified further to allow for the isolation of the enzymatically active, green fluorescent proteasomes (Fig. 4C). The GFP purification matrix beads showed high fluorescence intensity after incubation with PSMA1-GFP sperm acrosomal extracts (Fig. 4 C, ii), but not after incubation wild-type sperm extract (Fig. 4 C, ii). Eluted fraction revealed the presence of PSMA1-GFP fusion protein by Western blotting (WB) (Fig. 4 C, iii), and the proteasomal proteolytic activity in the eluted fraction was detected by proteasomal substrate fluorometry (Fig. 4 C, iv).

Discussion

This study shows that the PSMA1-GFP fusion protein is incorporated in the assembled 20S proteasomes of the PSMA1-GFP transgenic pig created as a tool to study the UPS in the reproductive system, brain, and any other organs or tissues. The PSMA1-GFP founder boar and his male and female offspring are fertile in vivo and in vitro. Robust GFP fluorescence from the expression of PSMA1-GFP construct at the four-cell stage of preimplantation development agrees with the time of major maternal-to-zygotic transition (MZT) of transcriptional control in porcine in vitro and in vivo embryos, determined by autoradiographic studies and transcriptional analysis (24–26). Occasionally, we detected weak GFP fluorescence already at the two-cell stage, which might indicate minor transcriptional reactivation at this early stage of development. Similarly, minor transcription from the male pronucleus already is observed at the one-cell, zygote stage in the mouse (27), a species in which minor transcription is initiated at the one-cell stage and the MZT occurs at the two-cell stage (28). Transcriptional and translational activity already is detectable in one- and two-cell–stage bovine embryos, a species in which the major MZT occurs at the four- to eight-cell stage (29).

Although acrosomal fluorescence was difficult to detect in the live PSMA1-GFP spermatozoa, the presence of the GFP-proteasomes in the transgenic sperm acrosome was documented by immunofluorescence with anti-GFP antibodies, and by WB of whole spermatozoa and acrosomal extract fractions. Natural GFP expression in live spermatozoa from the transgenic boar was weaker than we had intended, but this was overcome through GFP amplification methods and the GFP-proteasome location was confirmed to reside in the sperm acrosome. Lower expression in the mature spermatozoa most likely is the result of a reduced expression of the transgene during meiotic and postmeiotic phases of spermatogenesis. Also, it should be noted that the wild-type PSMA1 subunit was expressed from both maternal and paternal copies of the wild-type gene, whereas the transgene expression was only from the paternally contributed chromosome. In the future, the fluorescence intensity of PSMA1-GFP fusion protein in fully differentiated spermatozoa might be improved by using a promoter specific to the late part of spermatogenesis, such as protamine 1 or protamine 2. In WB, the PSMA1-GFP proteasomal subunit comigrated with the acrosomal membrane fraction. Conversely, the PSMA1-GFP subunit was not detected in the whole wild-type boar spermatozoa and acrosomal extract fractions or the soluble acrosomal matrix fraction obtained after the removal of wild-type acrosomal membranes. The appearance of a high-density band at the 25–30-kDa range corresponds to the molecular mass of the wild-type PSMA1 and, when antibodies against a shared domain of α-subunits are used, of the six other 20S proteasomal core α-subunits. The pattern of proteasome compartmentalization in the sperm head supports the proposed role of proteasomes in acrosomal function during fertilization (1, 3).

The GFP-tagged proteasomes copurify with known acrosomal/acrosome-binding proteins, including lactadherin MFGE8, spermadhesin AWN, and glycoprotein porcine seminal plasma-I (PSP-I). These findings are consistent with the deposition of MFGE8 and spermadhesins on the sperm acrosomal surface during passage or after ejaculation (30–32), and with the presence of proteasomes in the sperm acrosome and on the acrosomal surface (5, 7, 8). Both lactadherin MFGE8 and the aforementioned spermadhesins/seminal plasma proteins have been implicated in the formation of the oviductal sperm reservoir, in sperm capacitation, and in sperm–zona pellucida binding (33, 34). These structural proteins also might be the substrates of resident acrosomal proteasomes. Some of the proteins identified in SI Appendix, Table 5B also might serve to anchor the proteasome to acrosomal membranes, or participate in proteasome-assisted acrosomal remodeling during sperm capacitation and acrosomal exocytosis.

The 20S proteasome is composed of four concentric rings. The outer rings on each side of the “barrel” are composed of seven α-type subunits (PSMA1–7), whereas the inner rings, in which the proteolytic activity resides, are composed of seven β-type subunits (PSMB1–7) (3, 22). Unsurprisingly, the GFP-tagged proteasomes copurified with most of the 20S proteasomal core subunits, including all seven α-type subunits and six of seven β-type subunits as well as several isoforms thereof. The anti-GFP antibody was used for immunopurification, indicating that the PSMA1-GFP fusion protein is incorporated in the structurally sound 20S proteasomes during spermatogenesis. This also indicates that the copurification of GFP-proteasomes with other 20S proteasomal core subunits reveals the successful isolation of the 20S core. No 19S regulatory complex subunits were copurified, probably because of the detachment of the 19S subunit during sperm extract processing. This is consistent with results from protocols that use repeated freeze-thawing and sonication of source cells before immunopurification of proteasomes (35, 36). Whether any of the identified subunit isoforms are testis specific remains to be determined. An estimated one-third of sperm proteosomal subunits in Drosophila are testis specific (37), and there is at least one testis-specific α-type subunit isoform, designated PSMA8, in human testis (22).

As anticipated based on the coimmunopurification of PSMA1-GFP with other proteasomal subunits, we were able to isolate enzymatically active GFP-proteasomes. With further optimization of the purification and elution protocols, these fractions will be useful for studies in cell-free systems, including but not limited to research on sperm–oocyte interactions. Upcoming experiments will study the interactions of the sperm proteasome with MFGE8, spermadhesins, and other acrosomal proteins that copurify with sperm proteasomes. In addition to the study of fertilization, the PSMA1-GFP pig model might be used to study a variety of reproductive technologies and disorders, such as germ cell transplantation (38), ovarian/oocyte function (39), and endometriosis (40). The transgenic animal model described in the present study is available through the National Institutes of Health-sponsored NSRRC and may be used to study the functioning of the UPS in a variety of cellular pathways and pathologies, such as Alzheimer’s disease, Huntington disease, Parkinson disease, cancer, immune and inflammatory disorders, and liver cirrhosis. The deregulation of the UPS also has been implicated in the pathogenesis of genetic diseases such as cystic fibrosis, Angelman syndrome, and Liddle syndrome (41). In the case of cystic fibrosis, the PSMA1-GFP pigs might be crossed with the cystic fribrosis transmembrane conductance receptor null (CFTR−/−) pig (42) (www.exemplargenetics.com/cftr/). The fusion of GFP to the proteasome does not appear to interfere with proteasome function in male gametes or in other systems. Consequently, the PSMA1-GFP transgenic pigs are healthy, reach sexual maturity in a timely manner, and produce healthy, fertile offspring. The use of this transgenic pig model to advance the understanding of the role of the UPS has the potential to identify and validate therapeutic targets for the treatment and prevention of several diseases.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid Constructs and DNA Preparation.

The full-length sequence for porcine PSMA1 subunit of 20S proteasomal core was first constructed in silico from public data. This sequence was used to identify a GenBank EST sequence that appeared to be full length (accession no. CO946059), which was then retrieved from cryopreserved archive. The PSMA1 coding region was modified for cloning and recovered from the plasmid by PCR (primers: TTTTGGCAAAGAATTCGGAACCATGTTTCGCAACCAGT, CATGGTGGCGACCGGTGCATGTTCCATTGGTTCAT). The amplimer was cloned into pCAG-CreGFP (Addgene plasmid 13776) at the AgeI sites. Both vector and insert were gel purified, incubated in In-Fusion (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and transformed into NEB 5-alpha chemically competent cells (New England BioLabs). Positive colonies were sequenced to confirm correct ligation and the absence of PCR-induced point mutations. The PSMA1-GFP transgene, a selectable marker (pKW4, AphII) (43), and the chicken egg-white lysozyme matrix attachment region (cMAR) (44) were purified from vector sequence for cotransfection. The resulting linearized DNA fragments were transfected using 10 µg of total DNA at a ratio of 5:2:2 (PSMA1-GFP:AphII:cMAR).

Fibroblast Cell Culture, Transfection, and Selection.

Male porcine fetal fibroblast (104821, NSRRC) cells were cultured for 72 h before electroporation in DMEM with pyruvate and 12% FBS at 38.5 °C in 5% CO2, 5% O2, 90% air, and 100% humidity. Culture, transfection, and selection were performed as described previously (45). Following selection, fluorescent colonies were harvested. Approximately two-thirds of each colony was placed back into culture and one-third was used for cell lysis and PCR analysis of positive clones.

Somatic Cell Nuclear Transfer.

Mature oocytes were purchased from ART, Inc. and used for somatic cell nuclear transfer essentially as described (46, 47). The oocytes were shipped overnight in maturation medium no. 1 (48). After 24 h of culture, they were transferred to medium no. 2. After 40 h of maturation, they were enucleated and fused with a single intact donor cell by using two direct pulses of 1.2 kV/cm for 30 µs (BTX Electro Cell Manipulator 200) in 0.3 M mannitol, 1.0 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM MgCl2, and 0.5 mM Hepes (pH adjusted to 7.0–7.4). Fused oocytes were placed in 500 µL porcine zygote medium-3 (PZM3) containing 500 nM Scriptaid, a histone deacetylase inhibitor (47), and cultured for 14–16 h at 38.5 °C in humidified 5% CO2, 5% O2, and 90% N2. Cloned zygotes were transferred surgically to the oviducts of gilts in standing estrus. Six embryo transfers were performed, transferring 881 embryos. Eight piglets were recovered at caesarian section (six breathed). Five of the eight did not express, and one healthy expressing founder was identified (SI Appendix). Animal care followed a protocol approved by Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Missouri.

Acrosomal Extracts of Boar Spermatozoa.

Fresh boar spermatozoa were transferred to 15-mL Falcon tubes and centrifuged at 350 × g in a Fisher Scientific centrifuge for 5 min to remove the seminal plasma. The supernatant was removed, and the pellet was resuspended and washed in 9 mL of TL-Hepes containing 0.1% polyvinyl alcohol and 0.5% hyaluronidase, each time collected by centrifugation at 350 × g for 5 min. After washing, sperm pellets were resuspended in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8; 150 mM NaCl; 1% Triton; 0.5% sodium deoxycholate; 0.1% SDS; and PMSF, 1:200) or modified RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris⋅HCl, pH 8; 150 mM NaCl; 1% Nonidet P-40; 0.5% sodium deoxycholate; 1 mg/mL leupeptin; and 1 mg/mL pepstatin); resuspended samples were sonicated by using Digital Sonifier (Branson) for 1 min at 30% intensity. To prepare the acrosome extract, the disrupted spermatozoa were centrifuged at 5,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and supernatants were collected free of sperm head/tail fragments, as determined by light microscopy. The final supernatant fraction was stored at −80 °C.

Isolation of Enzymatically Active Proteasomes.

The GFP-binding agarose beads from the Fusion-Aid GFP Kit (MB-0732; Vector Laboratories) were washed with PBS (10 mM phosphate, 150 mM NaCL, pH 7.5) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Then, 0.5 mL of boar sperm acrosomal extract prepared by sonication, as described above, was added to the gel in the spin column, supplemented with 1 mM ATP and incubated for 2 h at room temperature. The spin column was centrifuged for 1 min at 350 × g, and the anti-GFP beads were washed in 0.4 mL of PBS once. The anti-GFP beads were transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube with 0.1 mL of elution buffer (PBS with 0.5% SDS) and incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. The spin column was centrifuged for 1 min at 350 × g, and the flow-through was collected. This elution procedure was repeated to maximize recovery. The purified GFP flow-through fraction was analyzed by fluorometry with specific proteasomal substrates. In some replicates, the eluted fractions were heated to 55 °C for 20 min to activate proteasomes before measurement.

Measurement of Proteasomal Activity.

Eluted proteasomal fractions were loaded onto a 96-well black plate (final concentration 1 × 106 spermatozoa per milliliter or equivalent eluted GFP fraction) and incubated at 37.5 °C with Z-Leu-Leu-Glu-AMC (Z-LLE-AMC) [a specific substrate for 20S chymotrypsin-like peptidyl-glutamyl peptide hydrolase (PGPH), final conc. 100 µM; Enzo Life Sciences] or ubiquitin-AMC (specific substrate for ubiquitin-C-terminal hydrolase activity, final conc. 1 µM; Enzo). Each well was supplemented with 2.5 mM ATP. The emitted fluorescence (no units) was measured every 2 min for a period of 20 min in a Thermo Fluoroskan fluorometer (Thermo/Fisher Scientific; excitation: 355 nm, emission: 460), yielding a curve of relative fluorescence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Connie Cepko for development of pCAG-CreGFP for Addgene deposit. This work was supported by National Research Initiative Competitive Grant 2011-67015-20025 from the US Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture (to P.S.), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grant U42 RR018877/OD011140 (to R.S.P. and K.D.W.), and seed funding from the Food for the 21st Century Program of the University of Missouri–Columbia (to P.S., K.D.W. and R.S.P.). P.S. is also supported by NIH–National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant 1R21HD066333-01A1.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Animal, germ cell, and tissue requests should be directed to the National Swine Resource and Research Center, www.nsrrc.missouri.edu.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1220910110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Sakai N, Sawada MT, Sawada H. Non-traditional roles of ubiquitin-proteasome system in fertilization and gametogenesis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2004;36(5):776–784. doi: 10.1016/S1357-2725(03)00263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Signorelli J, Diaz ES, Morales P. Kinases, phosphatases and proteases during sperm capacitation. Cell Tissue Res. 2012;349(3):765–782. doi: 10.1007/s00441-012-1370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sutovsky P. Sperm proteasome and fertilization. Reproduction. 2011;142(1):1–14. doi: 10.1530/REP-11-0041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sutovsky P, Van Leyen K, McCauley T, Day BN, Sutovsky M. Degradation of paternal mitochondria after fertilization: Implications for heteroplasmy, assisted reproductive technologies and mtDNA inheritance. Reprod Biomed Online. 2004;8(1):24–33. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60495-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmerman SW, et al. Sperm proteasomes degrade sperm receptor on the egg zona pellucida during mammalian fertilization. PLoS ONE. 2011;6(2):e17256. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Redgrove KA, et al. Involvement of multimeric protein complexes in mediating the capacitation-dependent binding of human spermatozoa to homologous zonae pellucidae. Dev Biol. 2011;356(2):460–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.05.674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morales P, Pizarro E, Kong M, Jara M. Extracellular localization of proteasomes in human sperm. Mol Reprod Dev. 2004;68(1):115–124. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pasten C, Morales P, Kong M. Role of the sperm proteasome during fertilization and gamete interaction in the mouse. Mol Reprod Dev. 2005;71(2):209–219. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sasanami T, et al. Sperm proteasome degrades egg envelope glycoprotein ZP1 during fertilization of Japanese quail (Coturnix japonica) Reproduction. 2012;144(4):423–431. doi: 10.1530/REP-12-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawada H, et al. Extracellular ubiquitination and proteasome-mediated degradation of the ascidian sperm receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99(3):1223–1228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032389499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kong M, Diaz ES, Morales P. Participation of the human sperm proteasome in the capacitation process and its regulation by protein kinase A and tyrosine kinase. Biol Reprod. 2009;80(5):1026–1035. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sutovsky P, et al. Proteasomal interference prevents zona pellucida penetration and fertilization in mammals. Biol Reprod. 2004;71(5):1625–1637. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.104.032532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yi YJ, et al. Inhibition of 19S proteasomal regulatory complex subunit PSMD8 increases polyspermy during porcine fertilization in vitro. J Reprod Immunol. 2010;84(2):154–163. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2009.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yi YJ, et al. Interference with the 19S proteasomal regulatory complex subunit PSMD4 on the sperm surface inhibits sperm-zona pellucida penetration during porcine fertilization. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;341(2):325–340. doi: 10.1007/s00441-010-0988-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yi YJ, et al. Ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase-activity is involved in sperm acrosomal function and anti-polyspermy defense during porcine fertilization. Biol Reprod. 2007;77(5):780–793. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.107.061275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morales P, Kong M, Pizarro E, Pasten C. Participation of the sperm proteasome in human fertilization. Hum Reprod. 2003;18(5):1010–1017. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deg111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chakravarty S, Bansal P, Sutovsky P, Gupta SK. Role of proteasomal activity in the induction of acrosomal exocytosis in human spermatozoa. Reprod Biomed Online. 2008;16(3):391–400. doi: 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60601-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diaz ES, Kong M, Morales P. Effect of fibronectin on proteasome activity, acrosome reaction, tyrosine phosphorylation and intracellular calcium concentrations of human sperm. Hum Reprod. 2007;22(5):1420–1430. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ficarro S, et al. Phosphoproteome analysis of capacitated human sperm. Evidence of tyrosine phosphorylation of a kinase-anchoring protein 3 and valosin-containing protein/p97 during capacitation. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(13):11579–11589. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202325200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baker MA, Reeves G, Hetherington L, Aitken RJ. Analysis of proteomic changes associated with sperm capacitation through the combined use of IPG-strip pre-fractionation followed by RP chromatography LC-MS/MS analysis. Proteomics. 2010;10(3):482–495. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glickman MH, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: Destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol Rev. 2002;82(2):373–428. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tanaka K. The proteasome: Overview of structure and functions. Proc Jpn Acad, Ser B, Phys Biol Sci. 2009;85(1):12–36. doi: 10.2183/pjab.85.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brooks SA. Functional interactions between mRNA turnover and surveillance and the ubiquitin proteasome system. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2010;1(2):240–252. doi: 10.1002/wrna.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hyttel P, et al. Nucleolar proteins and ultrastructure in preimplantation porcine embryos developed in vivo. Biol Reprod. 2000;63(6):1848–1856. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod63.6.1848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jarrell VL, Day BN, Prather RS. The transition from maternal to zygotic control of development occurs during the 4-cell stage in the domestic pig, Sus scrofa: Quantitative and qualitative aspects of protein synthesis. Biol Reprod. 1991;44(1):62–68. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod44.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson JE, Matteri RL, Abeydeera LR, Day BN, Prather RS. Degradation of maternal cdc25c during the maternal to zygotic transition is dependent upon embryonic transcription. Mol Reprod Dev. 2001;60(2):181–188. doi: 10.1002/mrd.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Adenot PG, Mercier Y, Renard JP, Thompson EM. Differential H4 acetylation of paternal and maternal chromatin precedes DNA replication and differential transcriptional activity in pronuclei of 1-cell mouse embryos. Development. 1997;124(22):4615–4625. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.22.4615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zeng F, Schultz RM. RNA transcript profiling during zygotic gene activation in the preimplantation mouse embryo. Dev Biol. 2005;283(1):40–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Memili E, First NL. Zygotic and embryonic gene expression in cow: a review of timing and mechanisms of early gene expression as compared with other species. Zygote. 2000;8(1):87–96. doi: 10.1017/s0967199400000861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Petrunkina AM, et al. Fate of lactadherin P47 during post-testicular maturation and capacitation of boar spermatozoa. Reproduction. 2003;125(3):377–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manaskova P, et al. Origin, localization and binding abilities of boar DQH sperm surface protein tested by specific monoclonal antibodies. J Reprod Immunol. 2007;74(1-2):103–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manaskova-Postlerova P, et al. Biochemical and binding characteristics of boar epididymal fluid proteins. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci. 2010;879(1):100–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2010.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liberda J, et al. Saccharide-mediated interactions of boar sperm surface proteins with components of the porcine oviduct. J Reprod Immunol. 2006;71(2):112–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2006.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Raymond A, et al. SED1/MFG-E8: a bi-motif protein that orchestrates diverse cellular interactions. J Cell Biochem. 2009;106(6):957–66. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bousquet-Dubouch MP, et al. Purification and proteomic analysis of 20S proteasomes from human cells. Methods Mol Biol. 2008;432:301–320. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-028-7_21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ducoux-Petit M, et al. Scaled-down purification protocol to access proteomic analysis of 20S proteasome from human tissue samples: Comparison of normal and tumor colorectal cells. J Proteome Res. 2008;7(7):2852–2859. doi: 10.1021/pr8000749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong L, Belote JM. The testis-specific proteasome subunit Prosalpha6T of D. melanogaster is required for individualization and nuclear maturation during spermatogenesis. Development. 2007;134(19):3517–3525. doi: 10.1242/dev.004770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Luo J, Megee S, Rathi R, Dobrinski I. Protein gene product 9.5 is a spermatogonia-specific marker in the pig testis: Application to enrichment and culture of porcine spermatogonia. Mol Reprod Dev. 2006;73(12):1531–1540. doi: 10.1002/mrd.20529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nagyova E, et al. Inhibition of proteasomal proteolysis affects expression of extracellular matrix components and steroidogenesis in porcine oocyte-cumulus complexes. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 2012;42(1):50–62. doi: 10.1016/j.domaniend.2011.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Celik O, et al. Combating endometriosis by blocking proteasome and nuclear factor-kappaB pathways. Hum Reprod. 2008;23(11):2458–2465. doi: 10.1093/humrep/den246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schwartz AL, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and pathogenesis of human diseases. Annu Rev Med. 1999;50:57–74. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.50.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rogers CS, et al. Disruption of the CFTR gene produces a model of cystic fibrosis in newborn pigs. Science. 2008;321(5897):1837–1841. doi: 10.1126/science.1163600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lorson MA, et al. Disruption of the Survival Motor Neuron (SMN) gene in pigs using ssDNA. Transgenic Res. 2011;20(6):1293–1304. doi: 10.1007/s11248-011-9496-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wells KD, Foster JA, Moore K, Pursel VG, Wall RJ. Codon optimization, genetic insulation, and an rtTA reporter improve performance of the tetracycline switch. Transgenic Res. 1999;8(5):371–381. doi: 10.1023/a:1008952302539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ross JW, et al. Optimization of square-wave electroporation for transfection of porcine fetal fibroblasts. Transgenic Res. 2010;19(4):611–620. doi: 10.1007/s11248-009-9345-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhao J, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitors improve in vitro and in vivo developmental competence of somatic cell nuclear transfer porcine embryos. Cell Reprogram. 2010;12(1):75–83. doi: 10.1089/cell.2009.0038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao J, et al. Significant improvement in cloning efficiency of an inbred miniature pig by histone deacetylase inhibitor treatment after somatic cell nuclear transfer. Biol Reprod. 2009;81(3):525–530. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.109.077016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li R, et al. Production of piglets after cryopreservation of embryos using a centrifugation-based method for delipation without micromanipulation. Biol Reprod. 2009;80(3):563–571. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.108.073387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.