Abstract

Cells genetically deficient in sphingomyelin synthase-1 (SGMS1) or blocked in their synthesis pharmacologically through exposure to a serine palmitoyltransferase inhibitor (myriocin) show strongly reduced surface display of influenza virus glycoproteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). The transport of HA to the cell surface was assessed by accessibility of HA on intact cells to exogenously added trypsin and to HA-specific antibodies. Rates of de novo synthesis of viral proteins in wild-type and SGMS1-deficient cells were equivalent, and HA negotiated the intracellular trafficking pathway through the Golgi normally. We engineered a strain of influenza virus to allow site-specific labeling of HA and NA using sortase. Accessibility of both HA and NA to sortase was blocked in SGMS1-deficient cells and in cells exposed to myriocin, with a corresponding inhibition of the release of virus particles from infected cells. Generation of influenza virus particles thus critically relies on a functional sphingomyelin biosynthetic pathway, required to drive influenza viral glycoproteins into lipid domains of a composition compatible with virus budding and release.

Keywords: lipid raft, flu assembly, sortagging, virus–host interaction

Release of newly assembled influenza virions requires not only a proper mixture of the viral constituents themselves but also relies on host factors such as endoplasmic reticulum (ER) components, glycosyltransferases, and factors that determine intracellular vesicular transport. Some of these host factors might serve as targets of new antiviral strategies (1). Given the tendency of viruses to acquire resistance under selective pressure exerted by the immune system or imposed by antiviral drugs (2–4), host factors are more likely to escape the emergence of resistance. Genome-wide RNAi screens designed to identify such host factors are predicated on this notion, as exemplified for HIV and influenza virus in several recent reports (5–7). These types of genetic approaches readily establish the involvement of particular proteins or other template-encoded products in viral biogenesis. In contrast, the role of complex carbohydrates and lipids is more difficult to discern, precisely because these are not themselves template-encoded, and rather are the end products of complex biosynthetic pathways. Although it is straightforward to alter by mutation a viral nucleic acid and the products it encodes, it is more difficult to selectively modify the carbohydrate or lipid composition of a virus without affecting many host functions in the process.

Enveloped viruses incorporate host components into their membranes for the construction of new infectious particles. The lipid composition of newly formed virions resembles that of the membrane compartments from which they bud. Vesicular stomatitis virus and influenza virus, which bud from the basolateral and apical domains of polarized epithelial cells, respectively, report on the lipid composition of these membrane domains (8, 9). The targeting signals carried by viral membrane glycoproteins, together with the propensity of viral membrane proteins to interact preferentially with certain classes of (glyco)sphingolipids, help determine the characteristics of the membrane domain(s) from which new particles originate (8).

The influenza virus envelope contains two major membrane glycoproteins, hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA), along with the M2 protein (10, 11). Assembly of new virus particles requires the coalescence of HA and NA in membrane domains of distinct lipid composition, with M2 proposed to play a later role in membrane scission (12) to achieve particle release. High local concentrations of cholesterol, sphingomyelin (SM), and glycosphingolipids impart on these membrane microdomains—also called “rafts”—unique biophysical properties, such as enhanced resistance to extraction by nonionic detergents (13). The debate about the physical size, lifetime, and dynamic behavior of these lipid rafts is unlikely to subside anytime soon (14, 15), nor is it clear whether these are the only membrane specializations controlled by lipid composition.

The role of lipid rafts in cellular processes is a matter of record (16, 17), and perturbation of the homeostasis of its major component, cholesterol, affects membrane behavior (14). Physical extraction of cholesterol with methyl-β-cyclodextrin and/or treatment of cells with drugs that inhibit cholesterol metabolism are common strategies used to perturb cellular pools of cholesterol (18, 19). The use of these compounds is prone to causing off-target effects, and therefore independent approaches, such as genetic manipulation of lipid biosynthetic pathways, are indispensable to extend these observations. Evidence for the role of lipid rafts in viral glycoprotein transport comes mainly from studies that target cholesterol levels. Even though SM is a key component of lipid rafts, its exact role in protein transport and viral biogenesis remains largely unknown. Here we describe the consequences of a defect in SM synthesis caused by inactivation of the SM synthase-1 (SGMS1) gene, as brought about by insertional mutagenesis (20) and pharmacological blockade (21). SGMS1-null cells and their wild-type counterparts are susceptible to infection with influenza and show similar patterns of glycoprotein maturation in transit from the ER through the Golgi apparatus, but SGMS1-deficient cells and myriocin-treated Maldin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells show a major delay in maturation and release of new virus particles.

Results

Characterization of SGMS1-Deficient KBM7 Cells.

SGMS1 catalyzes the transfer of phosphorylcholine from phosphatidylcholine (PC) onto ceramide to produce SM (Fig. 1A); SGMS1 is the major SM synthase in mammalian cells (22). To examine the role of SM in influenza virus infection, we used SGMS1GT (SGMS1-gene trap), a cell line isolated in a screen in a human haploid cell line selected for resistance to cytolethal distending toxins produced by various pathogenic bacteria (20, 23). SGMS1 transcripts are present in the parental cell line KBM7 but are absent from SGMS1GT cells, as shown by RT-PCR (Fig. 1B). We determined the ability of these cells to synthesize SM by metabolic labeling of KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells with the SM precursor N-methyl-[14C]-choline. We extracted total lipids followed by TLC and autoradiography. SGMS1GT cells showed reduced SM synthase activity (∼15%) compared with the KBM7 cells (Fig. 1 C and D). The residual activity is due to the second enzyme, SGMS2, which accounts for 10–20% of SM synthase activity in mammalian cells (24). We found no differences in the synthesis of [14C]-PC between SGMS1GT and KBM7 cells (Fig. 1 C and D).

Fig. 1.

SGMS1GT cells have reduced levels of SM. (A) Schematic representation of the SM biosynthesis pathway in mammalian cells. SGMS1-deficient KBM7 cells and myriocin, an SPT inhibitor (marked in box) show a block in sphingolipid biosynthesis. (B) RT-PCR analysis showing the absence of the SGMS1 transcript in SGMS1GT cells. (C) Autoradiogram of a TLC separation of lipid extracts of KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells metabolically labeled with the SM precursor [14C]-choline. (D) Quantification of the [14C]-SM and [14C]-PC signals from [14C]-choline labeling experiment in C. (E and F) Total lipids were extracted from KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells and subjected to MS/MS. Levels of sphingolipids (E) and glycerophospholipids (F) are expressed as mole percent of total lipid analyzed. (G) Total phosphate and cholesterol levels of KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells were determined and presented as mole percent relative to the control. Error bars represent SD of three (D) or two (E–G) independent experiments. Cer, ceramide; PC, phosphatidylcholine; PS, phosphatidylserine; PI, phosphatidylinositol.

SGMS1-Deficient KBM7 Cells Have Significantly Reduced Levels of SM.

To assess the contribution of SGMS1 to sphingolipid content at steady state, we determined the lipid composition of SGMS1GT and KBM7 cells using liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. We find that SGMS1GT cells have ∼20% of total cellular SM content compared with KBM7 (Fig. 1E), which corroborates our metabolic labeling experiments (Fig. 1 C and D). Lipid analysis of cells that were cultured for more than 2 wk in delipidated media showed a similar reduction of SM level. Hence, the remaining SM produced in SGMS1GT cells must result from the activity of SM synthase-2 (SGMS2). The decrease in SM levels in SGMS1GT cells was accompanied by a twofold increase of its precursor, ceramide (Fig. 1E). Ceramide is also a precursor for the synthesis of lactosylceramide (LacCer) and glucosylceramide (GlcCer). In SGMS1GT cells the level of LacCer increased fourfold, whereas the level of GlcCer increased twofold compared with KBM7 cells (Fig. 1E). The species of SM present in KBM7 and SGMS1-deficient cells were indistinguishable (Fig. S1). Relative to KBM7 cells, PC levels were higher, whereas phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) levels were lower in SGMS1GT cells (Fig. 1F). Cholesterol content and overall phosphate levels remain unchanged (Fig. 1G). Combined, our data show that SGMS1GT cells have significantly reduced levels of SM compared with the parental KBM7 line, consistent with the known defect in SM synthesis.

SGMS1-Deficient Cells Are Defective in Influenza Virus Production.

To examine the role of SM in the context of virus infection, we first assessed the extent to which SGMS1GT cells support an infection with influenza virus. We infected SGMS1GT and KBM7 cells at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 0.1. At 24 h after infection, cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]-methionine/cysteine. We analyzed total cell lysates by SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. We detected slightly more newly synthesized host proteins in SGMS1GT compared with KBM7 cells (Fig. 2A). This suggests a possible defect in viral production and in reduction of host protein synthesis in SGMS1GT cells, which therefore may be less able to sustain virus replication. The major viral proteins detected correspond to nucleoprotein (NP) and M1 (Fig. 2A). This led us to examine virus production by SGMS1GT cells. To this end, KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells were infected at an MOI of 0.1, and at 24 h after infection the media was collected and a fluorescent focus assay performed. SGMS1GT cells produce less than half the amount of virus than do KBM7 cells (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

SGMS1GT cells are defective in influenza viral particles production. (A) Equal numbers of KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells were infected with influenza virus (A/WSN/33) at an MOI of 0.1. At 24 h after infection, cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]-methionine/cysteine for 30 min and total cell lysates were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. (B) Cells were infected as described in A, and viral titers from the supernatant were measured by a fluorescent focus assay on MDCK cells. (C) Cells were incubated at different MOIs with Alexa 647-labeled influenza virus for 30 min on ice, followed by cytofluorimetry. (D) Flow cytometry of Alexa 647-positive cells upon exposure of KBM7, SGMS1GT, and SLC25A2GT with CTx-Alexa647 for 15 min on ice. SLC25A2GT cells are defective in GM1 biosynthesis and hence CTx is unable to bind to these cells. (E) Confocal images of KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells incubated with Alexa 647-labeled influenza virus and Alexa 488-CTx for 30 min on ice. FFU, focus-forming unit.

SGMS1-Deficient Cells Bind Influenza Virus in Amounts Similar to Those Bound by KBM7 Cells.

Because SGMS1GT cells show impaired production of influenza virus, we explored the step at which SM is required in the life cycle of the virus. To compare the extent of virus binding to KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells, we used a modified strain of influenza virus (HA-Srt), labeled site-specifically in its HA1 moiety with Alexa 647 (25). SGMS1GT and KBM7 cells were incubated with an equal amount of Alexa 647-labeled virus and/or cholera toxin (CTx) for 30 min on ice to prevent endocytosis and analyzed by cytofluorimetry or confocal microscopy. SGMS1GT and KBM7 cells bound similar amounts of labeled virus (Fig. 2 C and E), indicating that SM is not essential for adsorption of influenza virus. Additionally, SGMS1GT cells and KBM7 bound similar amounts of labeled CTx, particularly at lower concentrations of CTx (Fig. 3 D and E).

Fig. 3.

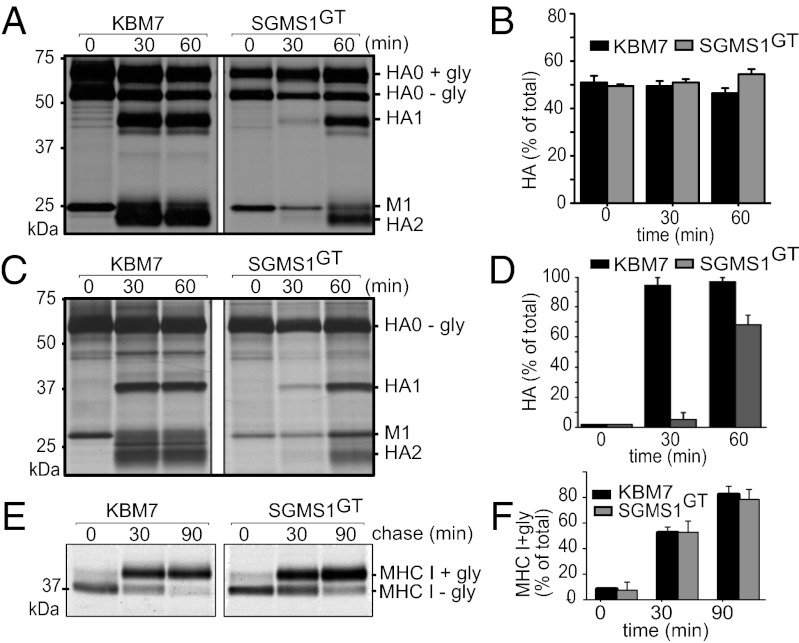

SGMS1GT cells are defective in trafficking of HA from the Golgi to the cell surface but not from the ER to Golgi. (A and C) KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells were infected at an MOI of 0.5. At 5 h after infection, cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]-methionine/cysteine for 10 min and chased for the indicated time points in the presence of trypsin in the chase medium. HA molecules were recovered by immunoprecipitation using anti-HA serum, subjected to Endo H (A) or PNGase F (C) treatment, and analyzed by SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. (E) KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]-methionine/cysteine for 10 min and chased for different time points. Cells were lysed and class I MHC molecules were recovered using W6/32 antibody, treated with Endo H, and analyzed by SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. (B, D, and F) Quantification of experiments performed as described in A, C, and E, respectively. Error bars, SD of three independent experiments.

Influenza Virus HA Transport from the ER to the Golgi Is Not Affected in SGMS1-Deficient KBM7 Cells.

Because initial binding of influenza virus to KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells was similar, we next investigated the trafficking of viral glycoproteins through the secretory pathway. In yeast, sphingolipid synthesis is critical for ER-to-Golgi transport of glycosylphosphatidylinisotol (GPI)-anchored proteins such as Gas1p (26), but the role of sphingolipids in glycoprotein trafficking in mammalian cells is less clear. We therefore examined the synthesis and maturation of influenza HA in KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells. The HA precursor (HA0) trimerizes and traffics through the secretory pathway, en route acquiring complex-type N-linked glycans in the Golgi (27, 28). Transport of HA from the ER to the Golgi apparatus proceeds normally in SGMS1GT cells, as assessed by the rate and extent of acquisition of Endoglycosidase H (Endo H) resistance (Fig. 3 A and B). Similarly, we found no measurable delay in trafficking of HA from the ER to the Golgi in MDCK cells treated with myriocin, a specific inhibitor of serine palmitoyltransferase (see below and Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Myriocin-treated MDCK cells are defective in cell-surface display but not ER to Golgi transport of influenza HA and NA. (A) MDCK cells treated with myriocin for 3 d were labeled with [14C]-choline or [14C]-serine for 4 h and lipids were extracted and analyzed by TLC. (B) MDCK cells treated with myriocin as described in A were infected with influenza virus at an MOI of 0.5. At 5 h after infection, cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]-methionine/cysteine for 10 min and chased for the indicated time points in the presence of trypsin added to the chase medium. Cells were lysed and HA molecules were recovered using anti-HA serum, subjected to Endo H treatment, and analyzed by SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. (C) MDCK cells treated with myriocin as described in A were infected at an MOI of 0.5 with HA-Srt virus, and at 5 h after infection cells were pulse-chased as described in B. At the indicated time points, surface-accessible HA-Srt was labeled with GGGK-biotin in the presence of sortase A for 1 h on ice. Cells were lysed, and biotin-labeled HA was recovered by affinity adsorption on NeutrAvidin agarose beads. (D) MDCK cells treated with myriocin and infected as described in C were pulse-labeled with [35S]-methionine/cysteine for 10 min. At the indicated time points the supernatants were collected and incubated with chicken erythrocytes to recover radiolabeled virus released into the media. Samples were analyzed as described in B. (E) Myriocin-treated MDCK cells were infected with NA-Srt virus and at the indicated time points after infection, cells were labeled with GGGK-biotin in the presence of sortase A for 1 h on ice. Cells were lysed, and biotinylated NA (= surface-exposed) was detected by immunoblotting using streptavidin-HRP (E, Upper), and total NA (= surface + intracellular) was detected using anti-HA epitope tag-HRP (E, Middle). (F) Quantification of experiments performed as described in E. Error bars, SD of three independent experiments. *The identity of this protein band is unknown.

Influenza Virus HA and NA Transport from the Golgi to Cell Surface Is Affected in Cells Defective of SM Biosynthesis.

SGMS1 is localized in the Golgi, where it catalyzes the production of SM on the luminal side of the trans-Golgi network (TGN). On the basis of our analysis of SGMS1GT cells, we hypothesized that a lack of SM in the Golgi compartment might affect membrane organization and hence impede trafficking of HA. To explore this, we infected SGMS1GT and KBM7 cells with influenza virus. We monitored arrival of metabolically labeled HA at the cell surface by trypsin treatment, which cleaves surface-disposed but not intracellular HA0 to yield two fragments, HAl and HA2 (29). Transport of HA from the Golgi to the cell surface was considerably delayed in SGMS1GT cells (Fig. 3 C and D). At 30 min of chase, most of HA in KBM7 cells had reached the cell surface, whereas only ∼5% arrived in SGMS1GT cells. However, at 60 min of chase, the difference was less pronounced, with ∼70% of HA arriving at the cell surface of SGMS1GT cells (Fig. 3 C and D).

We next determined whether SGMS1GT cells have a more general defect in protein transport. We monitored the level of secreted proteins in KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells. KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells were labeled for 30 min with [35S]-methionine/cysteine and chased for different times. Proteins secreted into the media were analyzed by SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. As a negative control, we incubated cells at 4 °C to block secretion. There was no difference in the levels of secreted proteins when comparing SGMS1GT and KBM7 cells (Fig. S2B). In parallel, we monitored the transport of class I MHC proteins—type I membrane glycoproteins that traffic through the constitutive secretory pathway to reach the cell surface (30). SGMS1GT cells show no significant difference in the transport of class I MHC (Fig. 3 E and F), as assessed by rate and extent of acquisition of Endo H resistance.

Myriocin is a potent inhibitor of serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT), an enzyme that catalyzes the first and rate-limiting step of de novo sphingolipid biosynthesis (21). Consequently the levels of ceramide—the substrate for SGMS1 and SGMS2—are expected to be significantly lower in myriocin-treated cells. We treated MDCK cells with 100 nM myriocin for 72 h before virus infection. We determined the extent of inhibition of SM synthesis by metabolic labeling with [14C]-serine or [14C]-choline of myriocin-treated and control MDCK cells and visualized the formation of [14C]-SM by TLC. Cells treated with myriocin showed a near-complete blockade of SM production, whereas the biosynthesis of other phospholipids such as [14C]-PC and [14C]-PS remained unaffected (Fig. 4A).

We monitored the arrival of HA at the cell surface by infecting MDCK cells with a “sortaggable” influenza virus (HA-Srt or NA-Srt), which allows site-specific incorporation of label in surface-displayed HA or NA (25). We infected myriocin-treated and control MDCK cells with HA-Srt and at 5 h after infection labeled them with [35S]-methionine/cysteine. At different chase times, cells were placed on ice and subjected to sortagging with biotin (25). We recovered biotinylated (= surface-disposed) HA using NeutrAvidin beads. We detected no biotinylated HA at the cell surface in myriocin-treated MDCK cells even at the 90-min chase point, whereas the majority of the biotinylated HA had reached the cell surface at 30 min chase point in control cells (Fig. 4C). The effects of SM depletion on surface display of HA are more severe than those recorded for methyl-β-cyclodextrin–mediated reduction of cholesterol levels (31).

We also examined trafficking of NA in myriocin-treated and untreated MDCK cells infected with NA-Srt virus (25), which encodes an NA that carries an HA epitope tag distal to the sortase recognition sequence. Surface-accessible NA was labeled with GGGK-biotin in the presence of sortase A enzyme for 1 h on ice (25). We used this approach because the abundance of NA is far less than that of HA, complicating its detection by metabolic labeling (32). Biotinylated (= surface-disposed) NA was detected in total cell lysate in immunoblots using streptavidin-HRP (Fig. 4E, Upper). Total NA levels (= surface + intracellular pools) were measured using an HRP-conjugated anti-HA epitope antibody, which does not recognize the HA of the A/WSN/33 virus (Fig. 4E, Middle). We observed a significant delay in the arrival of NA at the cell surface in myriocin-treated cells (Fig. 4 E and F). Sphingolipid biosynthesis is thus required for surface display of both HA and NA.

To determine the effect of myriocin treatment on the level of influenza virus production we infected myriocin-treated and control MDCK cells with the virus and performed pulse-chase experiment at 5 h after infection. At different time points during the chase the supernatants were collected and incubated with chicken erythrocytes to recover radiolabeled virus released into the media. Consistent with the SGMS1GT results, we found a strongly reduced level of viral proteins in the supernatants of myriocin-treated MDCK cells (Fig. 4D), indicating that intact sphingolipid biosynthesis is required for the efficient production of influenza virus. Collectively, our data show that proper sphingolipid biosynthesis makes a key contribution to surface display of flu glycoproteins and hence virus particle formation and release.

We then determined whether SM depletion disrupts trafficking of endogenous lipid raft-associated proteins by monitoring the rate of the recovery of Thy1, a glycosylphosphatidyl-anchored membrane glycoprotein, on the cell surface after its removal by phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C (PI-PLC) digestion. Myriocin-treated and control EL4 cells were treated with PI-PLC for 1 h at room temperature. After extensive washing to remove traces of PI-PLC, cells were returned to 37 °C. At different time points, the cells were costained with anti-Thy1-PE and anti-class I MHC-FITC and analyzed by FACS (Fig S2A). We found only slightly less Thy1 on the cell surface of myriocin-treated cells at 3 h incubation point compared with untreated EL4 cells (Fig S2A, Upper) and no difference with respect to class I MHC levels (Fig S2A, Lower).

Influenza Virus HA and NA Show Increased Triton X-100 Solubility upon Blockade of SM Biosynthesis.

Influenza virus HA and NA are known to associate with lipid rafts (17, 19, 33), but the role of SM in this process remains largely unknown. Lipid rafts and their associated proteins show impaired solubility in nonionic detergents such as Triton X-100 (TX-100) or Nonidet P-40 at 4 °C (34). Because transport of HA from the TGN to the cell surface is impaired in SGMS1-deficient cells, we examined the solubility of HA in cold nonionic detergent. For this purpose, virus-infected KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]-methionine/cysteine for 10 min, chased for different time points, and subjected to TX-100 extraction on ice. At the 0-h time point HA resides in the ER, whereas at 2 h the majority of HA localizes to the Golgi/post-Golgi compartment, as assessed by acquisition of Endo H resistance. This helped identify the compartment where SM is necessary for the interaction of HA with lipid rafts. At the 0-h time point, almost all HA was found in the soluble fraction, both in KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells. However, at the 2-h time point HA remained soluble in cold TX-100 in SGMS1GT cells, whereas in KBM7 cells a far greater fraction was detergent-insoluble (Fig. 5C). Treatment of MDCK cells with myriocin also yielded an increased fraction of TX-100 soluble HA (Fig. 5 A and B). Similarly, to measure cold detergent extractability of NA, we probed for NA at various time intervals after infection. At 2 h after infection we found NA to be soluble in cold TX-100 both in myriocin treated and untreated MDCK cells, presumably still residing in the early compartments of the secretory pathway. At 6 h after infection, a large fraction of NA in mock-treated MDCK cells becomes insoluble in cold TX-100, whereas in myriocin-treated cells the bulk of NA remains soluble (Fig. 5 D and E).

Fig. 5.

Influenza virus HA and NA retains TX-100 solubility upon blockade of sphingolipid biosynthesis. (A) Myriocin-treated and control MDCK cells were infected with influenza virus, and at 5 h after infection, cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]-methionine/cysteine for 10 min, chased for indicated time points, and subjected to cold 1% TX-100 extraction. HA molecules from the soluble (S) and insoluble (P) fractions were recovered using anti-HA serum, analyzed by SDS/PAGE, and autoradiography. (B) Quantification of three independent experiments performed as described in A or using KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells (C). (D) Myriocin-treated and control MDCK cells were infected with NA-Srt virus that carries the HA-epitope tag in addition to a sortase recognition motif. At the indicated time after infection, cells were subjected to cold T-X100 extraction. NA molecules from the soluble and insoluble fractions were detected by Western blotting using anti-HA epitope tag-HRP. (E) Quantification of three independent experiments performed as described in D.

Discussion

The assembly of influenza virus particles requires not only viral components themselves but also many host factors essential for glycoprotein maturation, (glyco)lipid synthesis, and vesicular transport. Genome-wide RNAi screens conducted for influenza virus and performed in different cell types have uncovered many host proteins proposed to contribute to virus assembly, but enzymes involved in lipid synthesis have not been identified in such screens (5–7). The SM synthase-1 null cell line (SGMS1GT) used in this study was isolated from the collection of mutants resistant to intoxication by cytolethal distending toxins (20, 23). SGMS1GT cells show a starkly reduced level of SM (15% of wild type) with the concomitant expected increase in its precursors—ceramide and phosphatidylcholine—and in other lipids that use ceramides as a precursor as well. Because of the pronounced preference of influenza virus HA for membrane domains enriched in cholesterol and glycolipids (35), we explored the role of SM content as a parameter that contributes to assembly of new influenza virions. Evidence for the role of lipid rafts in HA and NA trafficking mostly relies on cholesterol depletion by methyl-β-cyclodextrin (18, 31, 36). Although SM is believed to be a major component of rafts, scant evidence exists for a direct role of SM on HA/NA intracellular transport. In addition, contradictory reports on the effect of cholesterol depletion on influenza virus budding indicate that this question is far from solved (37). To this end we used SGMS1GT cells and myriocin, a compound that blocks SM synthesis. Interference with SM synthesis does not affect binding of influenza virus to the cell surface, and only minimally affects the ability of the virus to infect the cell.

HA0 trimerizes in the ER and assumes its native fold as it prepares to exit for the Golgi, a protracted process that involves imposition of the complex disulfide-bonding pattern to stabilize the native trimer (38). How a lipid annulus of defined composition is organized around the membrane anchors of HA and, by extension, NA is not known, but interactions might be through palmitoylation (39) and/or through the polypeptide segments interposed between the transmembrane anchors and the luminal portions with well-defined tertiary structure (18, 36). We show that compromised SM synthesis does not interfere with maturation of the N-linked glycans on HA, indicating that the transport of HA from the ER to the Golgi is not dependent on SM. The block in maturation of viral particles in SGMS1GT cells and myriocin-treated cells therefore must occur at or beyond the trans-Golgi network.

Consistent with this notion, we found that surface display of viral glycoproteins is affected when sphingolipid biosynthesis is compromised. We established this using three independent criteria: access of cell surface-exposed HA or NA to trypsin and sortase, as well as inhibition of release of virus particles. SM thus contributes to protein sorting from the TGN to the cell surface. The formation of protein carrier vesicles that bud from the TGN to deliver their cargo to the cell surface requires SM (40), and perturbation of SM biosynthesis might therefore affect cargo sorting. SM has affinity for cholesterol and forms lipid microdomains with distinct protein composition (41). Depletion of cholesterol through application of compounds such as methyl-β-cyclodextrin and lovastatin/mevalonate affect trafficking of raft-associated proteins, including GPI-anchored and some transmembrane proteins, such as influenza HA (42). As shown here, removal of SM is sufficient to cause a viral glycoprotein trafficking defect in its own right. Although SGMS1GT cells showed increased levels of ceramide and the glycosphingolipids LacCer and GlcCer, known to form lipid microdomains (43), they do not compensate for the reduction of SM as a requirement for proper trafficking of HA and NA, suggesting the possible existence of distinct classes of lipid microdomains with distinct biological roles. Overall, our data demonstrate how influenza virus and possibly other enveloped viruses exploit host factors such as cellular lipids during their life cycle. Interference with these pathways may provide new means of blunting the pathological effects caused by enveloped viruses.

Methods

Virus Propagation, Infection, and Fluorescent Focus Assay.

MDCK cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% serum, whereas KBM7 cells were grown in Iscove's modified Dulbecco's media (IMDM) with 10% serum. Influenza virus A/WSN/33 was propagated in MDCK cells. Infection of KBM7, SGMS1GT, and MDCK cells was performed as follows: cells were washed twice with PBS and subsequently incubated with virus diluted in PBS/0.2%/1 µg/mL of trypsin at room temperature for 30 min at the given MOI. Cells were then washed once in PBS to remove unbound virus and then placed into fresh DMEM supplemented with 0.2% BSA and 1 µg/mL of trypsin and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2. For quantifying virus titer, MDCK cells were infected with serial dilutions of supernatant. After infection, cells were washed and then incubated in 0.8% agar/MEM overlay. After 2 d, the overlay was removed, cells were fixed, and virus foci were detected via immuno-fluorescence using an NP-FITC antibody.

Myriocin Treatment of MDCK Cells.

MDCK cells were either mock treated (only DMSO) or treated with 0.5 µg/mL myriocin (in DMSO; Sigma Aldrich) for 72 h, after which cells were infected with influenza virus. Reduced levels of SM in myriocin-treated cells, was verified by lipid analysis as described. Biosynthetic labeling of viral proteins was unaffected in myriocin-treated cells as observed by total radiolabel incorporated.

Pulse Chase Experiments, Sortase Labeling, and Glycosidase Digestion.

MDCK cells were grown in 10-cm culture dishes and infected with either wild-type influenza virus WSN or engineered HA-Srt or NA-Srt virus (25) at an MOI of 0.5 for 4 h. In addition to sortase recognition sequence (LPETG), NA-Srt carries an HA epitope tag (25). KBM7 cells (wild type and SGMS1-deficient) cells were grown in suspension in 24-well plates to a density of 2 × 106 cells per well before infection. Cells were harvested and resuspended in methionine- and cysteine-free DMEM and starved for 45 min at 37 °C followed by a 10-min pulse labeling with [35S]-methionine/cysteine at 0.77 mCi/mL and chase in complete media for 0, 30, and 60 min. Where indicated, 1 µg/mL trypsin was added in the chase media. To probe for surface exposed HA at indicated time points during the chase, cell-surface HA molecules were labeled with 250 µM GGGK-biotin and 100 µM SrtA for 1 h at 4 °C. To measure total intracellular HA, cell pellets were collected, lysed in Tris buffer [150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM Tris (pH 7.4)] containing 0.5% Nonidet P-40 followed by immunoprecipitation with influenza virus anti-HA serum. For MDCK cells infected with NA-Srt virus, at indicated times after infection, cells were incubated for 1 h with 100 µM SrtA and 250 µM GGGK-biotin. Cells were lysed in buffer containing SDS, and biotinylated NA (= surface-disposed) was detected by Western blotting from the total lysate using streptavidin-HRP. The total NA (= surface + intracellular) was determined using anti-HA epitope tag-HRP (3F10). This antibody (3E10) does not recognize the HA of A/WSN/33.

For class I MHC pulse chase experiment, 10 × 106 KBM7 and SGMS1GT cells were labeled with [35S]-methionine/cysteine for 10 min and chased as indicated in the figure legend. At different time points during the chase cells were collected, washed once with cold PBS, and lysed in Tris buffer [150 mM NaCl, 5 mM MgCl2, 25 mM Tris (pH 7.4)] containing 0.5% Nonidet P-40. The lysates were precleared with immobilized protein G beads for 3 h, and class I MHC molecules were recovered using the monoclonal antibody (W6/32) to class I MHC. For all experiments, where indicated, immunoprecipitated samples were subjected to Endo H or PNGase F treatment according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Immunoprecipitates were eluted with SDS sample buffer and resolved by SDS/PAGE. Samples were visualized with autoradiography using DMSO/PPO (2,5-diphenyloxazole) and exposure to Kodak XAR-5 film. Densitometric quantification of radiograms and immunoblots were performed using Photoshop/Image J software.

TX-100 Extraction.

TX-100 extraction was performed according to refs. 13 and 35. For HA extraction, virus-infected cells were pulse-labeled with [35S]-methionine/cysteine at 0.77 mCi/mL for 10 min and chased for different time points. Cells were harvested, washed once with cold PBS, and resuspended in 0.5 mL of ice-cold Hepes-plus buffer [25 mM Hepes (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, and a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche)]. Extraction was initiated by addition of 0.5 mL 2% (wt/vol) TX-100 in Hepes-plus buffer (1% TX-100 final concentration) for 30 min on ice. To separate the soluble from the insoluble fraction, cells were centrifuged at 12,000 × g in an Eppendorf microfuge for 20 min at 4 °C. The pellet fraction was solubilized in a Hepes-plus buffer containing 1% digitonin with vigorous vortexing, and HA was immunoprecipitated from both fractions using anti-HA serum and analyzed by SDS/PAGE and autoradiography. To determine the detergent solubility of NA protein, cells were infected with NA-Srt virus (25). At different times after infection, cells were harvested and TX-100 extraction was done as described for HA. The pellet fraction of NA was solubilized in SDS sample buffer, and the amount of NA in soluble and insoluble fractions was detected by Western blotting. The insoluble fraction was calculated as the percentage relative to the total fraction (soluble and insoluble).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health R01 Awards AI033456 and AI087879. Funding has also been received from The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (F.G.T.) and from Sanofi Pasteur.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1219909110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Shaw ML. The host interactome of influenza virus presents new potential targets for antiviral drugs. Rev Med Virol. 2011;21(6):358–369. doi: 10.1002/rmv.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meliopoulos VA, et al. Host gene targets for novel influenza therapies elucidated by high-throughput RNA interference screens. FASEB J. 2012;26(4):1372–1386. doi: 10.1096/fj.11-193466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee SM, Yen HL. Targeting the host or the virus: Current and novel concepts for antiviral approaches against influenza virus infection. Antiviral Res. 2012;96(3):391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Müller KH, et al. Emerging cellular targets for influenza antiviral agents. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2012;33(2):89–99. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brass AL, et al. The IFITM proteins mediate cellular resistance to influenza A H1N1 virus, West Nile virus, and dengue virus. Cell. 2009;139(7):1243–1254. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.König R, et al. Human host factors required for influenza virus replication. Nature. 2010;463(7282):813–817. doi: 10.1038/nature08699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hao L, et al. Drosophila RNAi screen identifies host genes important for influenza virus replication. Nature. 2008;454(7206):890–893. doi: 10.1038/nature07151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerl MJ, et al. Quantitative analysis of the lipidomes of the influenza virus envelope and MDCK cell apical membrane. J Cell Biol. 2012;196(2):213–221. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201108175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalvodova L, et al. The lipidomes of vesicular stomatitis virus, semliki forest virus, and the host plasma membrane analyzed by quantitative shotgun mass spectrometry. J Virol. 2009;83(16):7996–8003. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00635-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Enami M, Enami K. Influenza virus hemagglutinin and neuraminidase glycoproteins stimulate the membrane association of the matrix protein. J Virol. 1996;70(10):6653–6657. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6653-6657.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gamblin SJ, Skehel JJ. Influenza hemagglutinin and neuraminidase membrane glycoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2010;285(37):28403–28409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R110.129809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rossman JS, Jing X, Leser GP, Lamb RA. Influenza virus M2 protein mediates ESCRT-independent membrane scission. Cell. 2010;142(6):902–913. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Skibbens JE, Roth MG, Matlin KS. Differential extractability of influenza virus hemagglutinin during intracellular transport in polarized epithelial cells and nonpolar fibroblasts. J Cell Biol. 1989;108(3):821–832. doi: 10.1083/jcb.108.3.821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simons K, Gerl MJ. Revitalizing membrane rafts: New tools and insights. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11(10):688–699. doi: 10.1038/nrm2977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Munro S. Lipid rafts: Elusive or illusive? Cell. 2003;115(4):377–388. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00882-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lingwood D, Kaiser HJ, Levental I, Simons K. Lipid rafts as functional heterogeneity in cell membranes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37(Pt 5):955–960. doi: 10.1042/BST0370955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simons K, Ikonen E. Functional rafts in cell membranes. Nature. 1997;387(6633):569–572. doi: 10.1038/42408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takeda M, Leser GP, Russell CJ, Lamb RA. Influenza virus hemagglutinin concentrates in lipid raft microdomains for efficient viral fusion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(25):14610–14617. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235620100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheiffele P, Roth MG, Simons K. Interaction of influenza virus haemagglutinin with sphingolipid-cholesterol membrane domains via its transmembrane domain. EMBO J. 1997;16(18):5501–5508. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Carette JE, et al. Haploid genetic screens in human cells identify host factors used by pathogens. Science. 2009;326(5957):1231–1235. doi: 10.1126/science.1178955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hojjati MR, et al. Effect of myriocin on plasma sphingolipid metabolism and atherosclerosis in apoE-deficient mice. J Biol Chem. 2005;280(11):10284–10289. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412348200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tafesse FG, Ternes P, Holthuis JC. The multigenic sphingomyelin synthase family. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(40):29421–29425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R600021200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carette JE, et al. Global gene disruption in human cells to assign genes to phenotypes by deep sequencing. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(6):542–546. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tafesse FG, et al. Both sphingomyelin synthases SMS1 and SMS2 are required for sphingomyelin homeostasis and growth in human HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282(24):17537–17547. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702423200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Popp MW, Karssemeijer RA, Ploegh HL. Chemoenzymatic site-specific labeling of influenza glycoproteins as a tool to observe virus budding in real time. PLoS Pathog. 2012;8(3):e1002604. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bagnat M, Keränen S, Shevchenko A, Shevchenko A, Simons K. Lipid rafts function in biosynthetic delivery of proteins to the cell surface in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97(7):3254–3259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.060034697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rossman JS, Lamb RA. Influenza virus assembly and budding. Virology. 2011;411(2):229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nayak DP, Hui EK, Barman S. Assembly and budding of influenza virus. Virus Res. 2004;106(2):147–165. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2004.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wiley DC, Skehel JJ. The structure and function of the hemagglutinin membrane glycoprotein of influenza virus. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:365–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.002053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiertz EJ, et al. The human cytomegalovirus US11 gene product dislocates MHC class I heavy chains from the endoplasmic reticulum to the cytosol. Cell. 1996;84(5):769–779. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81054-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller P, Simons K. Cholesterol is required for surface transport of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Cell Biol. 1998;140(6):1357–1367. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.6.1357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shaw ML, Stone KL, Colangelo CM, Gulcicek EE, Palese P. Cellular proteins in influenza virus particles. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4(6):e1000085. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang J, Pekosz A, Lamb RA. Influenza virus assembly and lipid raft microdomains: A role for the cytoplasmic tails of the spike glycoproteins. J Virol. 2000;74(10):4634–4644. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4634-4644.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lingwood D, Simons K. Detergent resistance as a tool in membrane research. Nat Protoc. 2007;2(9):2159–2165. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fiedler K, Kobayashi T, Kurzchalia TV, Simons K. Glycosphingolipid-enriched, detergent-insoluble complexes in protein sorting in epithelial cells. Biochemistry. 1993;32(25):6365–6373. doi: 10.1021/bi00076a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Barman S, Nayak DP. Analysis of the transmembrane domain of influenza virus neuraminidase, a type II transmembrane glycoprotein, for apical sorting and raft association. J Virol. 2000;74(14):6538–6545. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.14.6538-6545.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barman S, Nayak DP. Lipid raft disruption by cholesterol depletion enhances influenza A virus budding from MDCK cells. J Virol. 2007;81(22):12169–12178. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00835-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Receptor binding and membrane fusion in virus entry: The influenza hemagglutinin. Annu Rev Biochem. 2000;69:531–569. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.69.1.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen BJ, Takeda M, Lamb RA. Influenza virus hemagglutinin (H3 subtype) requires palmitoylation of its cytoplasmic tail for assembly: M1 proteins of two subtypes differ in their ability to support assembly. J Virol. 2005;79(21):13673–13684. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.21.13673-13684.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Holthuis JC, Levine TP. Lipid traffic: Floppy drives and a superhighway. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6(3):209–220. doi: 10.1038/nrm1591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Foster LJ, De Hoog CL, Mann M. Unbiased quantitative proteomics of lipid rafts reveals high specificity for signaling factors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100(10):5813–5818. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631608100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mayor S, Riezman H. Sorting GPI-anchored proteins. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5(2):110–120. doi: 10.1038/nrm1309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhang Y, Li X, Becker KA, Gulbins E. Ceramide-enriched membrane domains—structure and function. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1788(1):178–183. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.