Abstract

Interpretation of cognitive change has been complicated because different influences on change are not easily distinguished. In this study, longitudinal cognitive change was decomposed into a component related to the length of the interval between test occasions (i.e., time-dependent change) and a component unrelated to the test-retest interval (i.e., time-independent change). Influences of age on the two hypothesized components were investigated in a sample of more than 1,500 adults for whom the intervals between test occasions ranged from less than 1 year to more than 8 years. Although overall change was negatively related to age for all seven composite cognitive variables, little or no effect of age was apparent for the time-dependent component of change. The results suggest that the relations between age and cognitive change over intervals of less than 8 years are largely influenced by factors operating at or near the initial test occasion.

Keywords: longitudinal, cognitive change, aging, retest interval

It has been recognized for many years that measures of longitudinal change can be affected by a number of factors. For example, Campbell and Stanley (1963) identified history, maturation, testing, and instrumentation as possible influences on measures of change. These authors characterized the influences as threats to validity because they can be viewed as alternative interpretations of what might be producing the observed change. Various research designs for evaluating the contribution of different influences have been proposed; for example, the scores of individuals who are tested for the first time can be compared with the scores of same-age individuals who are tested for the second time to estimate effects associated with prior test experience (e.g., Baltes, Reese, & Nesselroade, 1977; Salthouse, 2010b).

However, an alternative approach to distinguishing influences on longitudinal change involves attempting to isolate meaningful components of change. For example, observed change can be postulated to consist of a component that varies as a function of the time between the two test occasions (i.e., T1 and T2) and a component unrelated to the length of the interval between the test occasions. Influences on time-independent changes will often be apparent at very short intervals and, by definition, will remain relatively constant as the interval between test occasions increases. Such influences may reflect aspects of test familiarity, anxiety reduction, or possibly instrumentation or period effects not systematically related to the test-retest interval. In contrast, influences on time-dependent change vary as a function of the interval between test occasions, and could reflect either a gradual change in magnitude over time of effects apparent at short intervals or the emergence of qualitatively different effects. For example, change may become more negative as the interval between test occasions increases because the benefits associated with the initial test experience gradually decay over time, or because other influences, such as factors related to maturation, become more pronounced as the T1-T2 interval increases.

Although not previously examined, the distinction between time-dependent and time-independent components of change could prove valuable in understanding the basis of individual differences in longitudinal change. For example, the direction and magnitude of cognitive change have been found to be systematically related to age among adults (e.g., Salthouse, 2010b, 2010c, 2011; Fig. 2.2 in Salthouse, 2010c), but the reasons why increased age is associated with progressively more negative change are not yet clear. Examining the effects of age on the time-dependent and time-independent components of change may therefore help in identifying the nature, and possibly the causes, of the relations between age and cognitive change. For example, a discovery that only time-independent aspects of change were related to age would suggest that effects associated with aging are attributable to factors whose influences remain constant across the interval between occasions, whereas dynamic, time-related, influences on change would presumably be implicated if increased age were found to be associated with progressively more negative change as the T1-T2 interval increased.

Two issues need to be considered when attempting to study the relation of change to the interval between test occasions. First, because any given individual can have only one interval between his or her first and second test occasions, examination of interval effects necessarily involves between-individual comparisons, which raises the possibility that interval differences could be confounded with various characteristics of the individuals. Although this type of confound is difficult to rule out completely, its potential contribution can be evaluated by examining the correlation between the length of the T1-T2 interval and the individual difference variable of primary interest. For example, if the correlation between age and the length of the interval were found to be close to zero, it could be inferred that interval comparisons are not confounded with variables associated with age.

A second complicating issue is that because everyone in a typical longitudinal study has nearly the same interval between successive assessments, investigating the relation of change to the length of the interval between test occasions is often not possible. Effects of the test-retest interval might be examined across separate studies involving different intervals between test occasions (as done by Thorndike, 1933), but comparisons of this type are not ideal because studies frequently differ with respect to the specific cognitive variables examined and the characteristics of the samples of research participants. Interval effects can be investigated more directly if the interval between test occasions varies across participants within the same study, such that the magnitude of change can be compared in the same cognitive variables and in similar participants. Only a few studies of this type have been published (e.g., McArdle, Ferrer-Caja, Hamagami, & Woodcock, 2002; McArdle & Woodcock, 1997; Salthouse, Schroeder, & Ferrer, 2004), and only one of these (Salthouse et al., 2004) directly examined the relation of change to the length of the retest interval. Although that study found significant negative relations between the T1-T2 interval and the magnitude of longitudinal change for all six variables examined, possibly because of the restricted age range (i.e., 18 to 58 years of age) or the relatively small sample sizes (i.e., between 120 and 284 individuals), none of the effects of age, or the interactions of age and interval, were significant.

Because the longitudinal data collection in the Virginia Cognitive Aging Project (Salthouse, 2010a, 2010b, 2010d) was deliberately designed to include across-participant variation in the test-retest intervals, the data from this project provide a unique opportunity to examine the proposed distinction between time-dependent and time-independent change. The current study therefore investigated the relations between age and two hypothesized components of longitudinal cognitive change. The average change across all test-retest intervals was used as an estimate of the combined effects of both components, and the slope of the function relating change to the interval between test occasions was used as an estimate of time-dependent change. The assessment of cognitive functioning was relatively broad, based on seven different composite variables representing a variety of cognitive abilities, and the samples were moderately large, comprising more than 1,000 adults across a wide age range for each ability.

Method

The 1,576 adults for whom data were available on two occasions ranged from 19 to 95 years of age (M = 53.6, SD = 17.1). The participants were initially recruited between 2001 and 2008 from newspaper advertisements, flyers, and referrals from other participants; longitudinal retesting began in 2004 and continued through 2009. Approximately 83% of the participants identified themselves as White and 9% as Black, with the remainder distributed in small percentages across different races and ethnicities. The range of test-retest intervals was 0.8 to 8.4 years, with a mean of 2.5 and a standard deviation of 1.1. The participants averaged 15.7 years of education (SD = 2.7), and their average self-rated health was in the very good range (i.e., an average of 2.2 on a scale ranging from 1, excellent, to 5, poor). Increased age was associated with higher levels of education (r = .22) and slightly lower self-rated health (r = .21). However, there was no correlation between age and the length of the T1-T2 interval (r = .02).

Average scores of the participants on four standardized tests (Vocabulary, Digit Symbol, Word Recall, and Logical Memory from the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale and Wechsler Memory Scale) ranged from 0.5 to 0.9 standard deviations above the age-adjusted values of the normative samples (Wechsler, 1997a, 1997b). Thus, the participants were functioning at relatively high levels. Attrition was selective for individuals over 40 years of age, as the returning participants in this age group had somewhat higher cognitive scores than nonreturning participants (Salthouse, 2010b).

Seven composite cognitive variables were created from data on participants' performance on a number of tests. Each composite was calculated by averaging z scores for two to four variables. Four variables were used to assess vocabulary, three assessed inductive reasoning, three assessed spatial visualization, three assessed verbal episodic memory, three assessed perceptual speed, and two each were used to assess performance in the A (simple) and B (alternating) conditions in the Connections variant of the Trail Making Test. The variables all had relatively high loadings on their respective constructs in confirmatory factor analyses, and correlations among the constructs (with the exception of the correlation between the Connections A and B constructs) were significantly less than 1; thus, the evidence supported both convergent and discriminant validity of the constructs. The variables are listed in Table 1 and are described in detail in other publications (e.g., Salthouse, 2010a, 2010b, 2011). Because some cognitive tests were not administered to all participants, the sample sizes for the composite variables ranged from 1,098 to 1,535.

Table 1. Description of the Cognitive Variables.

| Variable | Description |

|---|---|

| Connections–Simple | |

| Numbers | Draw lines to connect circled numbers in numeric sequence as rapidly as possible |

| Letters | Draw lines to connect circled letters in alphabetic sequence as rapidly as possible |

| Connections–Alternating | |

| Numbers-letters | Draw lines to connect circled numbers and letters in alternating numeric and alphabetic sequence as rapidly as possible, beginning with a number |

| Letters-numbers | Draw lines to connect circled numbers and letters in alternating numeric and alphabetic sequence as rapidly as possible, beginning with a letter |

| Vocabulary | |

| WAIS vocabulary | Provide definitions of words |

| WJ-R picture vocabulary | Name pictured objects |

| Antonym vocabulary | Select the best antonym of a target word |

| Synonym vocabulary | Select the best synonym of a target word |

| Reasoning | |

| Matrix reasoning | Determine which pattern best completes the missing cell in a matrix |

| Shipley abstraction | Determine the words or numbers that are the best continuation of a sequence |

| Letter sets | Identify which of five groups of letters is different from the others |

| Spatial Visualization | |

| Spatial relations | Determine the correspondence between a 3–D figure and alternative 2–D figures |

| Paper folding | Determine the pattern of holes that would result from a sequence of folding a paper and punching a hole through it |

| Form boards | Determine which combinations of shapes are needed to fill a larger shape |

| Memory | |

| Logical memory | Recall ideas in three stories |

| Word recall | Recall words from a word list over four trials |

| Paired associates | Recall response terms when presented with a stimulus item |

| Perceptual Speed | |

| Digit symbol | Use a code table to write the correct symbol below each digit |

| Letter comparison | Compare pairs of letter strings (same/different) |

| Pattern comparison | Compare pairs of line patterns (same/different) |

Note: WAIS = Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (Wechsler, 1997a); WJ-R = Woodcock–Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery: Revised (Woodcock & Johnson, 1990); Shipley = Shipley Institute of Living Scale: Revised (Zachary, 1986).

Results1

The initial step in the analyses consisted of converting the composite scores at T1 and T2 into z scores based on the mean and standard deviation at T1, and then subtracting the T1 scores from the T2 scores to derive measures of longitudinal change. Because of the direction of the subtraction, positive values represent an increase in performance from the first to the second occasion, whereas negative values correspond to a decrease.

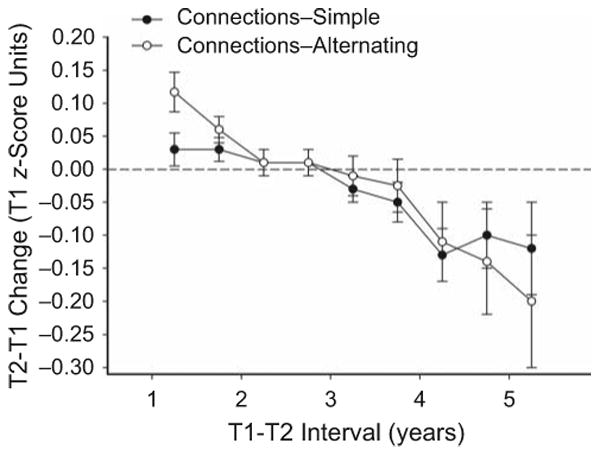

Figure 1 illustrates the relation between T1-T2 interval and change, portraying longitudinal change in the two composite variables from the Connections test as a function of the interval between the two test occasions. Because the data were somewhat noisy, the figure was created with a smoothing procedure. The plotted values are from partially overlapping groups, each with a T1-T2 range of 1.5 years; the range of each group differs from that of the previous group by 0.5 years (e.g., the first group includes intervals from 0.5 to 2.0 years, the second group includes intervals from 1.0 to 2.5 years, etc.). The important point to note in the figure is that there was a systematic relation between the value of longitudinal change and the length of the interval, with the change becoming progressively more negative as the T1-T2 interval increased.

Fig. 1.

Mean change, with standard errors, for the two Connections variables as a function of test-retest (T1-T2) interval. Successive data points are based on partially overlapping samples; each sample has a T1-T2 range of 1.5 years, and the ranges of successive samples begin 0.5 years apart.

The relation between age and T1-T2 interval was investigated next. The first step involved centering the age and interval variables, and then squaring each to create quadratic terms in which there was minimal collinearity with the corresponding linear terms (cf. J. Cohen, Cohen, West, & Aiken, 2003). Both the linear and the quadratic terms were then entered into regression equations predicting change in each cognitive variable. All increments in R2 associated with the quadratic influences were less than .002, and none of the quadratic terms was significantly different from zero. Because this suggests that the longitudinal changes were primarily linear across both age and test-retest interval, only linear relations were considered in subsequent analyses.

For each composite cognitive variable, a separate regression analysis examined T2-T1 change as a function of age, test-retest interval, and the interaction of age and test-retest interval (with the cross-product interaction term created after centering both the age and the interval variables to minimize collinearity). The unstandardized regression coefficients for each predictor in these analyses are reported in Table 2.2

Table 2. Unstandardized Coefficients From Multiple Regression Analyses With Age, Test-Retest Interval, and the Age-by-Interval Interaction as Simultaneous Predictors of Cognitive Change.

| Variable | Sample size | Predictor | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Age | Interval | Age × Interval | ||

| Connections–Simple | 1,535 | −0.006* | −0.048* | −0.002 |

| Connections–Alternating | 1,531 | −0.004* | −0.081* | −0.001 |

| Vocabulary | 1,453 | −0.004* | −0.024* | −0.002* |

| Reasoning | 1,098 | −0.002* | −0.052* | −0.001 |

| Spatial Visualization | 1,380 | −0.006* | −0.024 | 0.000 |

| Memory | 1,326 | −0.009* | −0.100* | −0.004* |

| Perceptual Speed | 1,531 | −0.005* | −0.081* | 0.000 |

p < .01.

Inspection of the entries in Table 2 reveals that the age and interval effects were all negative. Thus, the T2-T1 change was less positive with increases in age, and with increases in the interval between the two test occasions. Because the age and interval effects were both in units of change per year, the interval effects on cognitive change can be inferred to be between 4 and 25 times larger than the effects associated with 1 year of age.

The interaction of age and interval in the prediction of change was significant for the Vocabulary and Memory composite variables. However, in each case, the proportion of variance associated with the interaction was small relative to that associated with age (i.e., R2 of .007 for the interaction and .042 for age in the case of Vocabulary, and R2 of .012 for the interaction and .059 for age in the case of Memory). Age differences in the interval effects were also examined after dividing the sample at the median age, with participants between 18 and 53 in the young group and participants between 54 and 95 in the old group. None of the t tests comparing the groups' slopes for the regression equations relating change to the T1-T2 interval was significant, and the effect sizes were all quite small, ranging from −0.11 to 0.04 d units across the composite cognitive variables.

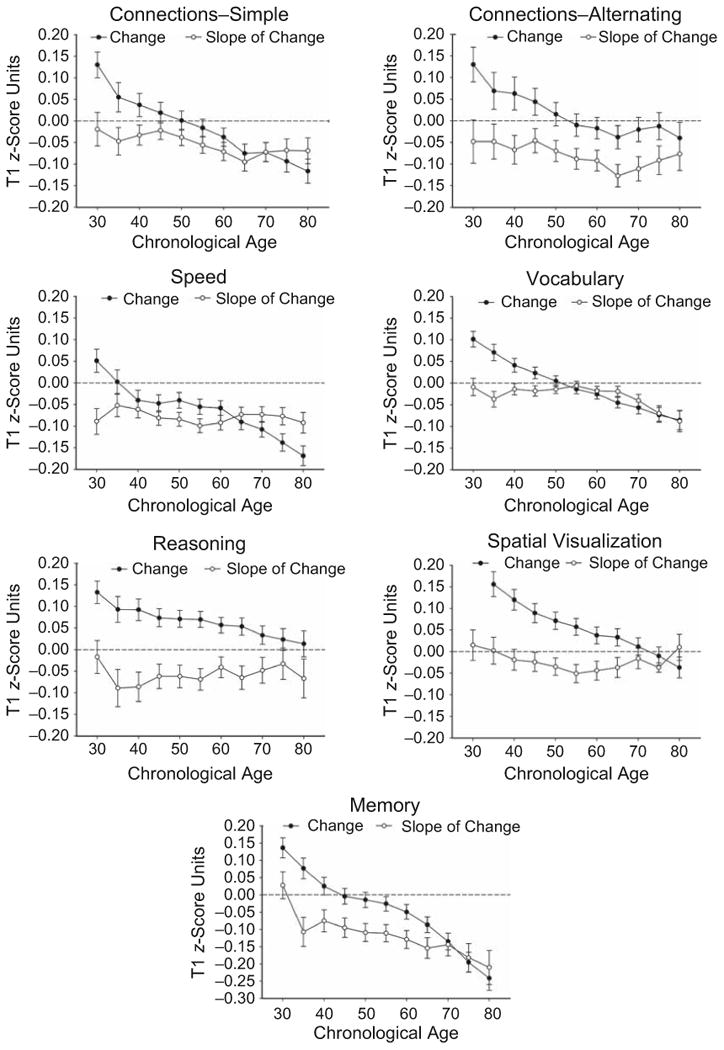

Figure 2 portrays the average T2-T1 change across all intervals as a function of age. The data were noisy, so they were smoothed to emphasize the trends; the plotted values are for overlapping age groups, with each group comprising a range of 20 years and differing from the previous group by 5 years (e.g., the youngest group ranged from 19 to 40 years old, the next youngest from 25 to 45 years old, etc.). Figure 2 also shows estimates of the time-dependent change as a function of age. The time-dependent values correspond to the slopes of functions such as those in Figure 1, derived separately for each age group.

Fig. 2.

Mean changes, and slopes of change as a function of test-retest (T1-T2) interval, as a function of age. Results are shown separately for each composite cognitive variable. Error bars indicate standard errors. Change was calculated by subtracting T1 performance from T2 performance. Successive data points are based on partially overlapping samples, each comprising a range of 20 years and differing from the previous group by 5 years. No data point is provided for overall change in Spatial Visualization at the youngest age because the value (0.24) is outside the range of the y-axis.

Consistent with the regression coefficients for age in Table 2, the graphs in Figure 2 reveal that increased age was associated with more negative change in every composite cognitive variable. In contrast, the functions relating the slope of change to age were all relatively flat, showing little or no relation between time-dependent change and age. The slopes for the Vocabulary and Memory variables, which had significant age-by-interval interactions in the regression analyses, were slightly more negative at the oldest ages than at other ages, but for every variable, the age trends were flatter for the estimates of time-dependent (i.e., slope) change than for the overall change measure.

A final set of analyses was conducted to examine whether the T1-T2 interval interacted with self-rated health, years of education, or global cognitive ability (as assessed by average z score across all abilities at T1) in predicting cognitive change. Although several main effects were significant (e.g., higher general cognitive ability was associated with more positive change in Spatial Visualization and Memory), none of the two-way interactions with interval or the three-way interactions with age and interval were significant, and all R2 values were less than .004.

Discussion

It is clear from these results that there is a systematic relation between the magnitude of longitudinal cognitive change and the length of the interval between the two test occasions. The interval effects were not large relative to the total change variance, as the R2 values for the simple interval effects (based on zero-order correlations) ranged from .007 to .033 for the six variables showing significant relations between change and T1-T2 interval. Nevertheless, these R2 values were all different from zero, and in each case the absolute magnitude of the effect was considerably larger than the effect associated with 1 year of age.

Increased age was associated with more negative longitudinal change for every cognitive variable, and for all variables except Spatial Visualization, the longitudinal changes became more negative as the interval between test occasions increased. However, only the composite Vocabulary and Memory variables exhibited a pattern in which increased age was associated with more negative change as the T1-T2 interval increased, and the results in Figure 2 indicate that the interactive effects were relatively small. Thus, one can infer that increased age has weak, and possibly nonexistent, relations with the time-dependent component of cognitive change.

Although this inference is based on acceptance of the null hypothesis, several aspects of the results suggest that it is justified. First, most of the smoothed age trends in Figure 2 are relatively flat, giving little indication of more negative slopes at older ages. Second, the observed effect sizes in the median-split analyses were all close to zero, and much smaller than the value often considered to represent a small effect size (i.e., d of 0.20). And third, there was substantial power to detect even small age differences in the rate at which longitudinal change varied as a function of the interval between test occasions, as the power to detect an increment in R2 of .02 in the regression analyses with a sample of 1,000 was greater than .95 (i.e., G*Power 3.1; Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner, & Lang, 2009).

The finding that age was related to overall change, but not to the time-dependent component of change, implies that increased age is associated with more negative values of time-independent change. More direct evidence for an age-related influence on the time-independent component is available in the negative age effects in the regression equations predicting change, as these effects correspond to constant, rather than time-varying, influences on change. Furthermore, separate analyses on the data from the approximately 200 adults in the current study with test-retest intervals of less than 1.5 years revealed that all of the correlations between age and change were negative. Neither of these results by itself is definitive, but they are both consistent with the existence of negative effects of age on time-independent change.

Two likely explanations for the time-independent influences are a reduction in anxiety, which might have hampered initial performance, and an increase in familiarity with the general testing environment or the specific test requirements, which could have contributed to better performance on a subsequent test. Such effects can be expected to be manifest immediately after the initial test experience.

The distinguishing feature of time-dependent influences is that they affect the slope, rather than the intercept, of the interval-change function. One plausible interpretation of time-dependent influences is that they are attributable to maturational changes becoming more pronounced with increases in the length of the interval. However, it is important to note that the average interval between test occasions in the current study was only 2.5 years, and therefore maturational changes may not have had much time to operate. Future research is needed to determine whether maturational declines might have a greater influence on time-dependent cognitive change with longer average intervals between test occasions.

Another factor that might contribute to more negative change with increases in the interval between test occasions is a loss of the benefits of prior test experience, including decays in memory for strategies and possibly even memory of specific test items. That is, a gradual dissipation of the positive effects associated with the previous testing could lead to cognitive change becoming more negative as the interval between test occasions increases. Because there was little or no influence of age on the time-dependent component of change in this study, a surprising implication of this interpretation is that increased age (with the possible exception of the oldest ages) does not appear to be associated with more rapid loss of test-relevant information over time.

The few prior studies in which recall of adults of different ages has been compared using retention intervals as long as months or years have reached similar conclusions. For example, Earles and Coon (1994) telephoned individuals who had participated in a test battery between 2 days and 6 months earlier and asked them to describe the specific tests they had performed. Accuracy of recall was significantly lower with increases in the length of the interval since the test (i.e., r = −.42) and with increases in the age of the participant (i.e., r = −.45). However, the interaction of age and retention interval was not significant, which suggests that there was little or no age difference in the rate of forgetting. Two other studies also reported no age differences in forgetting rates; one tested information learned during a college course and retention intervals ranging from 3 months to 12 years (G. Cohen, Stanhope, & Conway, 1992), and the other tested news events and retention intervals ranging from 1 day to 2 years (Meeter, Murre, & Janssen, 2005). In each of these studies, age differences in the rate at which the information was forgotten over time were small to nonexistent.

Although one might have expected that negative relations between age and cognitive change are attributable to progressively more negative change as the T1-T2 interval increases, the results of the analyses described in this article suggest that this is not the case. That is, with the possible exception of change in vocabulary and memory abilities, there was little evidence of an association between increased age and more pronounced time-dependent change. Thus, at least within a sample of healthy adults across a wide range of ages and test-retest intervals ranging between 1 and 8 years, most of the relation between age and longitudinal change appears to be associated with influences that remain relatively constant as the interval between test occasions increases.

The discovery that large proportions of the effects of age on short-term longitudinal change are associated with influences operating at or near the initial test occasion has both methodological and theoretical implications. For example, a methodological implication is that it may be valuable for longitudinal studies to obtain measures of change after an interval of days or weeks in addition to measures after intervals of years, to allow immediate effects to be distinguished from effects evolving over time. Perhaps the most important theoretical implication of the current results is that merely because change is measured over an interval does not necessarily mean that any observed influences on change operated across the entire interval. Indeed, the results of this study suggest that in some cases, age-related differences in longitudinal change may reflect age-related differences in processes related to learning and immediate retention as much as or more than age-related differences in processes that operate continuously during the interval between test occasions. Finally, because the change evident immediately after the initial test occasion could have a different meaning than the change that accumulates as a function of the length of the interval between test occasions, the distinction between time-dependent and time-independent longitudinal change will likely prove informative in decomposing other types of change, such as that associated with interventions or disease progression.

Acknowledgments

Funding: This research was supported by National Institute on Aging Grant R37AG024270.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author declared that he had no conflicts of interest with respect to his authorship or the publication of this article.

Because of the relatively large sample sizes, a significance level of .01 was used in all analyses.

Parallel analyses carried out with latent change models (e.g., Ferrer & McArdle, 2010) revealed a similar pattern of results: much larger interval than age effects on every cognitive ability, and significant interactions between age and interval only in the case of vocabulary and memory abilities.

References

- Baltes PB, Reese HW, Nesselroade JR. Life-span developmental psychology: Introduction to research methods. Monterey, CA: Brooks-Cole; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell DT, Stanley JC. Experimental and quasiexperimental designs for research. Chicago, IL: Rand McNally & Co.; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen G, Stanhope N, Conway MA. Age differences in the retention of knowledge by young and elderly students. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1992;10:153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Earles JL, Coon VE. Adult age differences in long-term memory for performed activities. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 1994;49:P32–P34. doi: 10.1093/geronj/49.1.p32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A, Lang AG. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41:1149–1160. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer E, McArdle JJ. Longitudinal modeling of developmental changes in psychological research. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2010;19:149–154. [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Ferrer-Caja E, Hamagami F, Woodcock RW. Comparative longitudinal structural analyses of the growth and decline of multiple intellectual abilities over the life span. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:115–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle JJ, Woodcock RW. Expanding test-retest designs to include developmental time-lag components. Psychological Methods. 1997;2:403–435. [Google Scholar]

- Meeter M, Murre JMJ, Janssen SMJ. Remembering the news: Modeling retention data from a study with 14,000 participants. Memory & Cognition. 2005;33:793–810. doi: 10.3758/bf03193075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Does the meaning of neurocognitive change change with age? Neuropsychology. 2010a;24:273–278. doi: 10.1037/a0017284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Influence of age on practice effects in longitudinal neurocognitive change. Neuropsychology. 2010b;24:563–572. doi: 10.1037/a0019026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Major issues in cognitive aging. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010c. [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. The paradox of cognitive change. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2010d;32:622–629. doi: 10.1080/13803390903401310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA. Cognitive correlates of cross-sectional differences and longitudinal changes in trail making performance. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology. 2011;33:242–248. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2010.509922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse TA, Schroeder DH, Ferrer E. Estimating retest effects in longitudinal assessments of cognitive functioning in adults between 18 and 60 years of age. Developmental Psychology. 2004;40:813–822. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.40.5.813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorndike RL. The effect of the interval between test and retest on the constancy of the IQ. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1933;24:543–549. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–Third Edition. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp; 1997a. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Memory Scale–Third Edition. San Antonio, TX: Psychological Corp; 1997b. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, Johnson MB. Woodcock–Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery: Revised. Allen, TX: DLM; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Zachary RA. Shipley Institute of Living Scale: Revised. Los Angeles, CA: Western Psychological Services; 1986. [Google Scholar]