Abstract

Objective

To use measures of CSF 5HIAA and MAOA-uVNTR genotype to study the role of central nervous system (CNS) serotonin in clustering of hostility, and other psychosocial, metabolic and cardiovascular endophenotypes.

Methods

In 86 healthy men, we evaluated cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) levels of the primary serotonin metabolite 5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5HIAA) and genotype on a functional promoter polymorphism of the monoamine oxidase A gene (M-uVNTR) for association with 29 variables assessing hostility, other psychosocial, metabolic, neuroendocrine and cardiovascular endophenotypes.

Results

The correlations of 5HIAA with these endophenotypes in men with more active MAOA-uVNTR alleles were significantly different from those with less active alleles for 15 of 29 endophenotypes. MAOA-uVNTR phenotype and CSF 5HIAA interacted to explain 20% and 22% of the variance, respectively, in scores on one factor wherein high scores reflected a less healthy psychosocial profile and a second factor wherein high score reflected increased insulin resistance, BMI, blood pressure and hostility. In men with less active alleles, higher 5HIAA was associated with more favorable profiles of hostility, other psychosocial, metabolic and cardiovascular endophenotypes; in men with more active alleles, higher 5HIAA was associated with less favorable profiles.

Conclusions

These findings indicate that in men indices of CNS serotonin function influence the expression and clustering of hostility, other psychosocial, metabolic and cardiovascular endophenotypes that have been shown to increase risk of developing cardiovascular disease. The findings are consistent with the hypothesis that increased CNS serotonin is associated with a more favorable psychosocial/metabolic/cardiovascular profile, while decreased CNS serotonin function is associated with a less favorable profile.

Keywords: central nervous system, serotonin, cardiovascular risk factors, hostility, metabolic syndrome components, MAOA-uVNTR polymorphism

Introduction

Hostility is a psychosocial characteristic that has been shown to predict increased risk of developing coronary heart disease (CHD) and increased all-cause mortality in prospective epidemiological studies. (1-5) Recent research (6, 7) has shown that hostility also predicts higher mortality in CHD patients over a 9-year follow-up period. Hostility does not occur in isolation, however, from other psychosocial factors that have been found to predict increased rates of CHD and other health problems. It has been shown, for example, that hostility, anger, depression, anxiety and social isolation are all elevated in women who report high strain at work (8), and hostility, depression and social isolation are all elevated in persons of lower socioeconomic status (9, 10). And as with physical risk factors, when psychosocial risk factors co-occur in the same persons or groups, their impact on CHD risk is compounded. (11)

The mechanisms whereby hostility and other psychosocial risk factors affect the etiology and course of CHD have not been definitively determined, but research has identified several biologically plausible pathogenic behavioral and biological characteristics that cluster in persons with high hostility levels. Among the potential mediators that have been found to co-occur with hostility and other psychosocial risk factors are increased risky health behaviors (12, 13), increased cardiovascular and neuroendocrine reactivity to stress (14), increased platelet activation (15), increased inflammatory cytokines (16, 17), and increased expression of impaired glucose tolerance and other components of the metabolic syndrome in non-diabetic patients (18, 19).

During the rest of this report we shall use the term endophenotype to refer to these psychosocial and biological risk characteristics that tend to cluster in certain individuals. According to Leboyer et al. (20), endophenotypes are “traits that are associated with the expression of an illness and are believed to represent the genetic liability of the disorder among non-affected subjects.” (P. 104, emphasis added) Endophenotypes are thus vulnerability traits that can be biochemical, endocrinological, neurophysiological, neuroanatomical, cognitive, or neuropsychological.

An extensive body of research shows that CNS serotonin function influences the expression of many of the psychosocial and biological endophenotypes described above. (21-23), It has been proposed (24, 25), therefore, that reduced CNS serotonin function could be responsible for the clustering of hostility and other psychosocial risk factors with behavioral and biological endophenotypes that affect the development and course of CHD. There are several means of assessing CNS serotonin function that can be used to test this hypothesis. The plasma prolactin response to drugs that enhance serotonergic neurotransmission has been used as an indirect measure CNS serotonin function. Muldoon and coworkers. have found a smaller prolactin response to these drugs to be correlated, for example, with increased resting blood pressure (26) and increased levels of the metabolic syndrome and its components (27).

Another, perhaps more direct means of assessing CNS serotonin function is measurement of CSF levels of the major serotonin metabolite, 5-hydroxyindolacetic acid (5HIAA). CSF 5HIAA levels have been found associated with CNS serotonin turnover, especially in the frontal cortex (23, 29). Low CNS serotonin function, as indexed by CSF 5HIAA, is under both genetic and environmental control and correlates with impulsive and aggressive behaviors, as well as tendencies toward alcohol abuse, in nonhuman (30) and human primates (31,32).

CSF 5HIAA levels have been found to vary as a result of functional polymorphisms of genes that regulate serotonin function. The serotonin promoter polymorphism (5HTTLPR) has been found associated with CSF 5HIAA levels, but in ways that vary as a function of both sex and race, with the S/S genotype associated with higher 5HIAA levels in women and blacks but with lower levels in men and whites. (33) A functional polymorphism of the MAOA gene promoter (MAOA-uVNTR) has also been found associated with CSF 5HIAA levels in men, with those who have the more active (3.5/4 repeats) alleles exhibiting higher 5HIAA levels, presumably reflecting increased breakdown of serotonin into 5HIAA, than those with less active (2/3/5 repeats) alleles.(33) Given the sample size in that study, it is possible that there was insufficient power to detect a similar association in the females. However, because the MAOA gene is located on the X chromosome, with men having a single copy and women having two copies, and given the phenomenon of X-inactivation – whereby in women one variant of a gene on one X chromosome inactivates, in a variable pattern from tissue to tissue, a different variant of that gene on the other X (34) – it is also plausible that the association is limited to the males.

Our goal in this study is to test the hypothesis (24, 25) that CNS serotonin function influences the expression of hostility, other psychosocial risk factors, metabolic and CV endophenotypes and their tendency to cluster in the same individuals and groups. Because CSF 5HIAA levels can be increased as a result of both the rates of serotonin synthesis and release and the rate of serotonin breakdown by MAOA, CSF 5HIAA levels cannot be used as a simple, direct index of CNS serotonin function. Based on our previous research (33), we posit that in men with the less active MAOA-uVNTR alleles (2/3/5 repeats), a high CSF 5HIAA level most likely reflects a higher rate of serotonin synthesis and release in the CNS. In men with the more active alleles, however, a high CSF 5HIAA level could reflect primarily increased serotonin breakdown into 5HIAA and hence indicate a reduction in CNS serotonin function. Based on this rationale, we predict that CSF 5HIAA will be associated in men with hostility, other psychosocial, metabolic and cardiovascular endophenotypes that have been found, as reviewed above, to cluster in the same individuals and groups, but that this association will be moderated by MAOA-uVNTR genotype. More specifically, we predict that in men with less active MAOA-uVNTR alleles, in whom a high CSF 5HIAA levels probably reflects increased serotonin synthesis and release, high 5HIAA levels will be associated with a positive, healthier profile of hostility, psychosocial, metabolic and cardiovascular endophenotypes. In contrast, among those with more active alleles, in whom high 5HIAA could reflect reduced functional serotonin due to increased degradation by MAOA, we expect to see a less positive, less healthy profile of these endophenotypes.

Methods

Subjects

The subjects in this study (all men) were drawn from the larger Community Health and Stress Evaluation study (CHASE) (35). Subjects were admitted during the years 1999-2003 to the General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) at Duke University Medical Center for a 2.5 day protocol that included lumbar puncture to obtain CSF, followed by randomization to either CNS serotonin enhancement (using tryptophan infusion) or CNS serotonin depletion (using tryptophan depletion) arms, with sham infusion or depletion on the first test day followed by active depletion or infusion on the second test day. Subjects also underwent mental stress testing at the point of expected maximal serotonin enhancement or depletion, with monitoring of cardiovascular function and collection of blood samples to assess neuroendocrine and immune system parameters. Results relating to serotonin manipulations and responses to stress testing are being reported elsewhere.

Subjects were recruited via advertisements in the public media, inclusion in the community newsletter as part of the county water bill, flyers posted throughout the community, via outreach screening events at civic organizations and other public events, and in paid advertisements such as the back of supermarket tapes. This protocol required that subjects not be at risk due to the study procedures and that subject characteristics not hamper interpretation of the findings, making it important to ensure a sample population in good current health. Therefore, all subjects underwent a comprehensive examination using a modified SCID as well as medical history, physical exam, electrocardiogram, chest radiograph, hemoglobin, hematocrit, white cell count, and blood chemistries to rule out current psychiatric and medical disorders. Use of any prescription drugs as well as use of illegal drugs (as detected by a urine screen prior to entry into study) were grounds for exclusion. (35)

The final sample consisted of 86 males (38 white and 48 black, based on self-description), had a mean age of 34.2 (SD, 8.7), 14.4 (SD, 2.7) years of education, BMI of 26.2 (SD, 4.7). A form approved by the Duke University Medical Center Institutional Review Board was used to obtain informed consent from all subjects.

Procedures

Subjects reported to the GCRC during the early afternoon. After completing admission procedures, and without a period of bed rest, lumbar puncture was performed by a board-certified anesthesiologist (K.G. or M.S.-S.). Initially, as in published studies (31, 32), we obtained 10-12 mililiters (ml) of CSF, which was mixed (to abolish the expected gradient across successive samples during the collection) and then separated into 2-ml aliquots and frozen for later assay of monoamine metabolites. The unsurprising 10-15% incidence of post-tap headaches among the first subjects, especially the females when the CHASE study was starting led us to determine whether there was a gradient of 5HIAA levels across aliquots in the next two subjects. There was no gradient, with 5HIAA concentrations in ml 11-12 being virtually identical to those in ml 1-2. A previous study (36) showed that without strict bed rest prior to the lumbar puncture, body height is only weakly correlated with CSF 5HIAA levels. Since our subjects had been ambulatory prior to lumbar puncture, it appears that CSF in the lumbar column had been mixed by their movements, thereby abolishing any gradient due to height. Therefore, we used a smaller needle to obtain only 3-4 ml of CSF, thereby preventing post-tap headaches. To ensure that findings are not affected by height differences, however, in all analyses evaluating effects of CSF 5HIAA height was covaried.

Measures

Genotyping

Fresh blood samples were collected in EDTA tubes and signed into the Center for Human Genetics DNA Bank. DNA was extracted and stored according to methods and quality checks as previously reported (37). An aliquot of DNA was used for MAOA genotyping. The MAOA-u VNTR region was amplified with primers: Forward-FAM-CAGCCTGACCGTGGAGAAG and Reverse-GAACGGACGCTCCATTCGGA as described before (38). PCR products were separated by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and visualized on a Hitachi FMBIO IIT Multi-View Scanner. Greater than 95% genotyping efficiency was required before data were submitted for further analysis. In addition, blinded duplicate samples were included on all gels and required to match 100% prior to data submission.

5-Hydroxyindoleacetic acid (5HIAA) in CSF was measured by high-pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC) with electrochemical detection. The method used is a trace-enrichment method that utilized sequential C-18 columns for samples cleanup and analytical separation (39). Samples were diluted in 0.2 N PCA containing 0.5 mM EDTA and 0.5 mM sodium metabisulfite, and injected directly onto the HPLC. The sample is enriched on a C18 precolumn using an aqueous mobile phase composed of 0.05 M citrate, 0.05 M dibasic sodium phosphate, 0.5 mM EDTA at pH 3.5. Then the sample is eluted onto a Waters Spherisorb 3 uM ODS2 C18 column with a mobile phase containing 4-8% acetonitrile in addition to the components of the enrichment mobile phase. Samples are detected by electrochemical detection, with a detector potential set at +.55 mV vs. Ag/AgCl reference electrode. Data are collected with a computer-based data collection system, and quantitated with the use of internal standard and external standard curves. Sensitivity of the assay is 0.5 ng/sample, and values are reported as ng/ml.

Blood was drawn after an overnight fast and assayed for glucose using a Beckman Glucose Analyzer (Beckman Instruments, Chicago, IL) and insulin using the Linco immunoassay kit (Linco Labs, St. Louis, MO). Insulin resistance using homeostatic model assessment (HOMA) was calculated using the formula HOMA = glucose (mg/dl) × insulin (μU)/22.5. A plasma lipid panel was measured by LabCorp.

Hostility was measured using the 27-items found by Barefoot et al. (40) to yield indicators of the hostility components cynicism, hostile affect and aggressiveness that are stronger predictors of health outcomes than the full Cook-Medley Ho scale. Other measures of trait hostility included BPQ(41) and the Acting Out Hostility HDHQ Subscale (42). Subjects also completed a battery of questionnaires to yield measures of other psychosocial risk factors. Depression was assessed using the Obvious Depression Scale from the MMPI (43), the Beck Depression Inventory (44) and a Hopelessness scale by Anda et al (45). The big five personality domains were assessed using. the NEO Personality Inventory- Revised (46). Social support was assessed using Berkman's Social Network Scale (47) and the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (48). The protective factor optimism was assessed using the Life Orientation Test (49).

Statistical Analysis

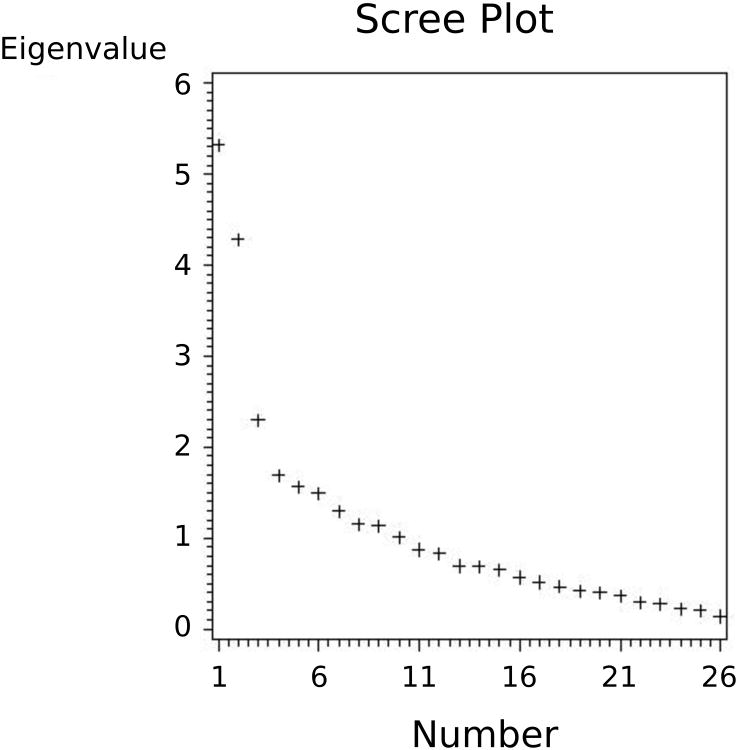

To determine whether MAOA-uVNTR genotype was associated with levels of hostility, other psychosocial, metabolic and cardiovascular endophenotypes measured in this sample, linear models were used to compare levels between MAOA-uVNTR genotypes. The next step in testing the hypothesis that CSF 5HIAA associations with these endophenotypes would differ as a function or MAOA-uVNTR genotype was accomplished by computing Pearson correlations of the endophenotypes with CSF 5HIAA separately for subjects with more versus less active MAOA-uVNTR alleles. To determine whether these correlations differed as a function of MAOA-uVNTR genotype, the CSF 5HIAA × MAOA-vNTR genotype interaction was evaluated using multiple regression models. Next, to determine whether the hostility, other psychosocial, metabolic, neuroendocrine and cardiovascular endophenotypes cluster into easily interpretable factors that can be evaluated in the same way as the individual endophenotypes, we performed a factor analysis. Through examination of the scree diagram (Figure 1) representing our set of data and imposing minimum eigenvalues on our solution, we determined three to be the appropriate number of factors (eigenvalues of 5.3, 4.2 and 2.3) to extract for further evaluation. Beginning with a principal components solution, we rotated first to an orthogonal varimax, then an oblique promax solution. The varimax rotation enabled better definition of each factor's loadings, while the promax solution resulted in a slight easing of the requirement of factor independence. In fact, there were no great differences in the loadings from the two rotations. Final solutions for the three factors explained over 39% of the total variance among the set of endophenotypes while still remaining only minimally correlated with each other (r's of -0.19, 0.05 and 0.08). Five of the 29 endophenotypes did not load appreciably on any of these factors and will not be included further in the presentation of results. Factor extractions on the subset of men were virtually identical to those on the entire sample.

Figure 1. Scree plot of factors by eigenvalues.

Given complications related to X-inactivation in females (34), we confined our analyses to the males in this sample There was a trend (chi-square = 3.638, P=0.057) for the inactive MAOA-uVNTR alleles to be more frequent in blacks (52%) than whites (32%). To ensure that effects of CSF 5HIAA and MAOA-uVNTR genotype did not vary as a function of race, models were run testing effects of the race × CSF 5HIAA, race × MAOA-uVNTR and race × CSF 5HIAA × MAOA-uVNTR interactions on the measured endophenotypes. None of these interactions was significant, and control for them had minimal effects on the CSF 5HIAA × MAOA-uVNTR interaction effects on the endophenotypes or derived factors. Therefore, analyses were run using the combined sample of white and black men. To control for differences in perfusion distance from the brain to the lumbar area, height was partialled out in all analyses.

Results

We first evaluated in all 86 men associations of CSF 5HIAA and MAOA-uVNTR genotype separately with the 24 hostility, other psychosocial, metabolic and cardiovascular endophenotypes that loaded on Factors 1-3 (Table 1). Only one of 24 correlations involving CSF 5HIAA – with insulin, r = 0.23 – was significant at the 0.05 level, no more than would be expected by chance. Similarly, only the Acting Out Hostility scale was associated (P=0.03) with MAOA-uVNTR genotype as a main effect.

Table 1.

Correlations – r(P) – between CSF 5HIAA levels and metabolic, cardiovascular and psychosocial variables in all male subjects, those with more active MAOA-uVNTR (3.5/4 repeats) alleles and those with less active MAOA-uVNTR (2/3/5 repeats) alleles, adjusted for height.

| Variable | All Male Subjects N=86 | Subjects With More Active Alleles N=49 | Subjects With Less Active Alleles N=37 | P for CSF 5HAAA × MAOA-uVNTR interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic/Cardiovascular | ||||

| Fasting Glucose | 0.06(0.58) | 0.25(0.12) | −0.22(0.22) | 0.06 |

| Fasting Insulin | 0.23(0.05) | 0.47(0.002) | −0.26(0.14) | 0.005 |

| LN HOMA | 0.20(0.08) | 0.46(0.003) | −0.22(0.22) | 0.008 |

| BMI | 0.13(0.23) | 0.22(0.15) | 0.13(0.47) | 0.83 |

| SBP (Baseline) | 0.20(0.08) | 0.39(0.008) | −0.13(0.46) | 0.02 |

| DBP (Baseline) | 0.05(0.68) | 0.13(0.38) | −0.08(0.64) | 0.68 |

| Triglycerides | −0.08(0.46) | 0.22(0.14) | −0.43(0.01) | 0.002 |

| VLDL-Cholesterol | 0.02(0.87) | 0.22(0.14) | −0.38(0.03) | 0.007 |

| HDL-Cholesterol | 0.06(0.57) | 0.06(0.68) | 0.12(0.51) | 0.57 |

| Apolipoprotein A | 0.04(0.69) | 0.09(0.56) | 0.01(0.93) | 0.69 |

| Psychosocial | ||||

| Neuroticism | −0.05(0.63) | 0.25(0.10) | −0.46(0.006) | 0.003 |

| Extroversion | 0.07(0.52) | −0.12(0.45) | 0.30(0.08) | 0.03 |

| Openness | −0.09(0.45) | −0.16(0.30) | 0.19(0.28) | 0.10 |

| Agreeableness | −0.02(0.87) | -0.05(0.75) | 0.10(0.58) | 0.55 |

| Conscientiousness | −0.06(0.57) | −0.30(0.05) | 0.29(0.10) | 0.005 |

| Cook-Medley Ho-37 | 0.06(0.57) | 0.43(0.003) | −0.30(0.09) | 0.003 |

| Buss-Perry Hostility | 0.21(0.07) | 0.44(0.003) | −0.40(0.05) | 0.0009 |

| Acting Out Hostility (HDHQ) | -0.04(0.72) | 0.26(0.10) | −0.29(0.12) | 0.04 |

| Obvious Depression Scale | 0.00(0.99) | 0.30(0.04) | −0.52(0.002) | 0.002 |

| Hoplessness (Anda) | −0.14(0.22) | −0.02(0.88) | −0.27(0.12) | 0.26 |

| Beck Depression Inventory | 0.13(0.25) | 0.31(0.04) | −0.33(0.06) | 0.009 |

| Berkman Social Network Inventory | 0.16(0.16) | 0.17(0.27) | 0.01(0.95) | 0.40 |

| Interperson Support Evaluation List | 0.10(0.36) | −0.42(0.004) | 0.44(0.009) | 0.0006 |

| Optimism (LOT) | 0.01(0.93) | −0.18(0.22) | 0.34(0.05) | 0.03 |

| Factor Scores | ||||

| Factor 1 | 0.06(0.67) | 0.44(0.01) | −0.55(0.005) | 0.0004 |

| Factor 2 | 0.30(0.02) | 0.58(0.0005) | −0.16(0.45) | 0.008 |

| Factor 3 | −0.01(0.95) | −0.02(0.92) | 0.05(0.81) | 0.95 |

As shown in Table 1, when correlations of CSF 5HIAA with the 24 endophenotypes were run separately for men with more vs less active MAOA-uVNTR alleles, the pattern of associations between CSF 5HIAA level and endophenotypes was remarkably different. Among men with more active alleles, 9 of 24 correlations were significant at the 0.05 level; among those with the less active alleles, 7 of 24 were significant at the 0.05 level. The CSF 5HIAA × MAOA-uVNTR interaction showed that these different correlations as a function of MAOA-uVNTR genotype was significant for 15 of the 24 endophenotypes, significantly more than would be expected by chance. The pattern of correlations was remarkably consistent and in line with our initial hypotheses. In men with more active alleles higher CSF 5HIAA was correlated significantly with less healthy levels of metabolic and CV endophenotypes -- higher fasting glucose, insulin, HOMA, SBP -- as well as hostility and psychosocial endophenotypes – higher scores on Cook-Medley Ho, Buss-Perry Hostility, Obvious Depression scale, Beck Depression Inventory and lower scores on Conscientiousness and Interpersonal Support Evaluation List. In marked contrast, among men with less active alleles, higher CSF 5HIAA was correlated significantly with a more positive, healthier pattern -- lower triglycerides, VLDL-cholesterol, Neuroticism, Buss-Perry Hostility, Obvious Depression and higher Interpersonal support and Optimism.

To estimate power to detect differences in correlations between CSF 5HIAA and the endophenotypes, we used Cohen's (50) definition of effect sizes, wherein comparison of correlations coefficients in the two genotype groups are determined both by size of the difference and where on the scale comparisons are made. Thus, power comparisons are based on Z-transformation -- i.e., power, q, =Z1 – Z2, where Z1=[log(1+ri/1-r1)]/2 -- of the differences to make them location invariant. With 49 men having the more active alleles and 37 having the less active alleles, if we assume the two compared correlations are of equal size but opposite sign, a “large” effect size (q=0.50) would back translate into r1=0.24 and r2=-0.24. As can be readily appreciated from inspection of Table 1, most of the correlation differences between men with more vs less active alleles were of this magnitude or greater.

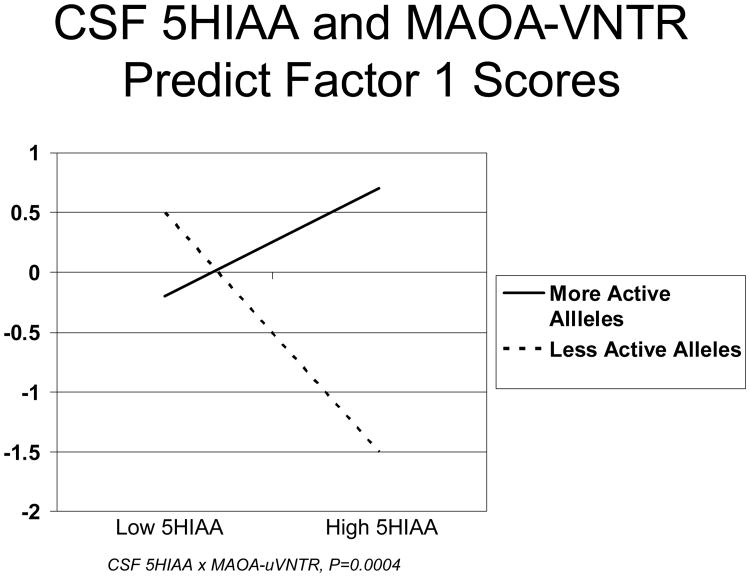

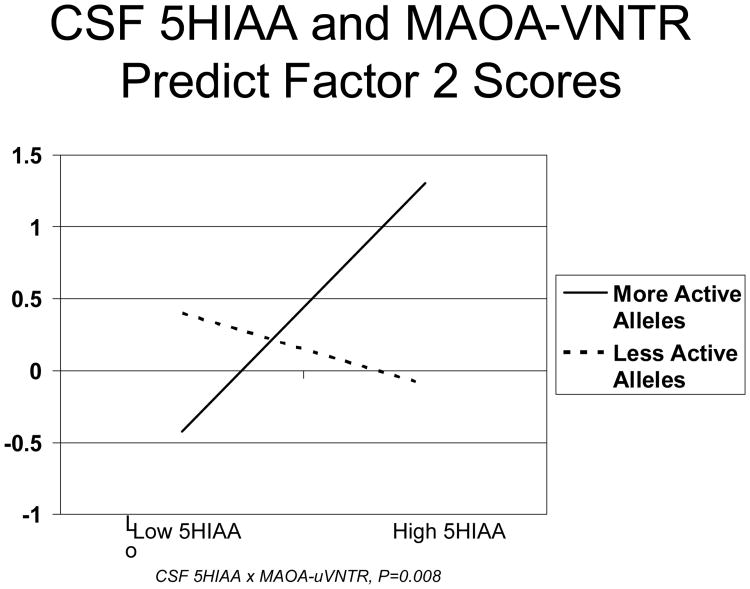

As shown in Table 2, Factor 1 had loadings >0.40 on 13 of 14 hostility and other psychosocial endophenotypes, with a high score on this Factor indicating a more negative, less healthy psychosocial profile – higher hostility, Neuroticism, depression, and lower Extraversion, Agreeableness, Conscientiousness, social support and optimism. Factor 2 had positive loadings on fasting glucose and insulin, HOMA, BMI, SBP, DBP and Cook-Medley Hostility, with a high Factor score indicating a more negative, less healthy metabolic, cardiovascular and hostility profile consisting of increased fasting glucose and insulin, insulin resistance, higher blood pressure, BMI and hostility. Factor 3 had positive loadings on HDL-cholesterol and Apolipoprotein A and negative loadings on tryglycerides and VLDL-cholesterol, with high Factor scores indicating a healthier lipid profile. As also shown in Table 1, CSF 5HIAA × MAOA-uVNTR genotype interactions were robustly associated with scores on Factor 1 (P<0.001) and Factor 2 (P=0.008). As shown in Figures 2 and 3, scores on both Factor 1 and Factor 2, respectively, increased with increasing CSF 5HIAA in men with more active MAOA-uVNTR alleles, while in those with less active alleles Factor 1 and 2 scores decreased with increasing 5HIAA level. This pattern of associations indicates that in men with more active MAOA-uVNTR alleles, higher CSF 5HIAA was associated with a more negative, less healthy levels both of psychosocial endophenotypes that clustered in Factor 1 and hostility, insulin resistance, BMI and SBP and DBP that clustered in Factor 2. In contrast, among those with less active alleles, higher CSF 5HIAA was associated with more positive, healthier scores on Factors 1 and 2.

Table 2. Metabolic, cardiovascular and psychosocial variables with loadings >0.40 on three factors that emerged from principal components factor analysis.

| Variable | Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metabolic/Cardiovascular | |||

| Fasting Glucose | 0.65 | ||

| Fasting Insulin | 0.78 | ||

| LN HOMA | 0.83 | ||

| BMI | 0.49 | ||

| SBP (Baseline) | 0.58 | ||

| DBP (Baseline) | 0.57 | ||

| Triglycerides | −0.79 | ||

| VLDL-Cholesterol | −0.79 | ||

| HDL-Cholesterol | 0.83 | ||

| Apolipoprotein A | 0.67 | ||

| Psychosocial | |||

| Neuroticism | 0.62 | ||

| Extroversion | −0.44 | ||

| Openness | |||

| Agreeableness | −0.48 | ||

| Conscientiousness | −0.42 | ||

| Cook-Medley Ho-37 | 0.67 | 0.42 | |

| Buss-Perry Hostility | 0.69 | ||

| Acting Out Hostility (HDHQ) | 0.60 | ||

| Obvious Depression Scale | 0.71 | ||

| Hoplessness (Anda) | 0.54 | ||

| Beck Depression Inventory | 0.74 | ||

| Berkman Social Network Inventory | −0.42 | ||

| Interpersonal Support Evaluation List | −0.79 | ||

| Optimism (LOT) | −0.71 |

Figure 2.

Relationship between CSF 5HIAA levels and Factor 1 Scores in men with more vs less active MAOA-uVNTR Alleles.

Figure 3.

Relationship between CSF 5HIAA levels and Factor 2 Scores in men with more vs less active MAOA-uVNTR Alleles.

The CSF 5HIAA × MAOA-uVNTR interaction explained no more than 18% of the variance in any of the 24 hostility, psychosocial, metabolic and CV endophenotypes that loaded on the the three factors extracted, with the mean variance explained being 8.46%. In contrast, the CSF 5HIAA × MAOA-uVNTR interaction explained 20% of the variance in Factor 1 scores and 22% in Factor 2, but 0% of Factor 3.

Discussion

These findings show that neither CSF 5HIAA nor MAOA-uVNTR genotype independently predict psychosocial or physiological endophenotypes that increase cardiovascular disease risk. When they are considered jointly, however, CSF 5HIAA and MAOA-uVNTR genotype are strongly associated with several of the hostility, other psychosocial, metabolic and cardiovascular endophenotypes, and even more strongly with clusters of them derived by principal components factor analysis with varimax and promax rotations. Thus, high CSF 5HIAA was associated with a more negative, less healthy profile of endophenotypes in those with more active MAOA-uVNTR alleles and a more positive, healthier profile in those with less active alleles.

This differential association between CSF 5HIAA and hostility, psychosocial, metabolic and cardiovascular endophenotypes was confirmed when principal components factor analysis identified three interpretable factors with two that were robustly associated with CSF 5HIAA in ways that, like the individual endophenotypes themselves, differed as a function of MAOA-uVNTR genotype. Thus, as shown in Figure 2, among men with more active alleles, higher CSF 5HIAA levels were associated with a higher score on Factor 1, where high scores reflect a less healthy profile characterized by increased hostility/aggression and depression and reduced social support and optimism, In contrast, among those with less active alleles higher CSF 5HIAA was associated with a lower Factor 1 score, indicative of a healthier, more positive hostility/psychosocial profile. A similar pattern was observed for Factor 2 (Figure 3) where in men with more active alleles higher CSF 5HIAA was associated with high scores reflecting a less healthy profile characterized by increased hostility, fasting glucose and insulin, insulin resistance, BMI, SBP and DBP. The CSF 5HIAA × MAOA-uVNTR interaction was not associated with Factor 3, where high scores reflect a “good” profile characterized by low triglycerides and VLDL-cholesterol and high HDL-cholesterol and Apolipoprotein A..

What could account for these opposite effects of CSF 5HIAA on the expression of these two endophenotype clusters -- one reflecting a general pattern of psychosocial distress and the other reflecting a pattern of increased insulin resistance, hostility and blood pressure – as a function of MAOA-uVNTR genotype? As we reported previously in this same sample (33), men with more active MAOA-uVNTR alleles exhibit significantly higher levels of CSF 5HIAA, an association that is consistent with increased MAOA enzymatic activity resulting in increased degradation of serotonin into 5HIAA. We postulate, therefore, that in men with more active alleles a higher CSF 5HIAA levels can be an indicator of increased serotonin breakdown, which would result in a reduced level of functional serotonin. In contrast, among those with less active alleles a higher 5HIAA level most likely reflects increased serotonin synthesis and/or release. The adverse patterns of hostility, psychosocial, metabolic and CV endophenotypes indexed by higher Factor 1 and 2 scores observed in men with more active alleles and higher 5HIAA could be the result, therefore, of reduced CNS serotonin function, while the more favorable patterns indexed by lower Factor 1 and 2 scores in men with less active alleles and higher 5HIAA could stem from increased CNS serotonin function among them.

We also found that the CSF 5HIAA × MAOA-uVNTR interaction explained 20% of the variance in Factor 1 scores and 22% for Factor 2 scores. In contrast, in no case was the variance explained by the CSF 5HIAA × MAOA-uVNTR interaction for individual hostility, psychosocial, metabolic and CV endophenotypes larger than 18%, and the average variance explained across the 24 endophenotypes examined was only 8.5%. Taken together, these findings in our male subjects are consistent with the principle suggested by Stoll et al.(51) that larger amounts of variance in “physiological profiles” of “functionally related clusters” would be explained, pleiotropically, by genetic variants than the amount of variance explained in single endophenotypes.

This is the first report that an association between what has been thought (28, 29) to be a direct measure of CNS serotonin turnover – CSF 5HIAA – and clusters of endophenotypes that have been associated themselves with increased risk of CV disease varies as a function of genotype on a functional polymorphism (MAOA-uVNTR) of the gene that makes the enzyme that is responsible for converting sertonin into 5HIAA. The robustness of the effects of the CSF 5HIAA × MAOA-uVNTR interaction on these empirically derived clusters of hostility, psychosocial, metabolic and CV endophenotypes in the men in this study combines with the remarkable consistency of the effects – high 5HIAA in men with more active alleles associated with less healthy physiological/psychosocial profiles; high 5HIAA in men with less active alleles with healthier profiles – to increase our confidence in their validity.

An additional point to note is that, although the principal components factor analysis also yielded a third factor reflecting high triglycerides and low HDL-cholesterol, this factor was unrelated to the CSF 5HIAA × MAOA-uVNTR interaction, suggesting that some components of what has been termed the “metabolic syndrome” may be mediated by altered CNS serotonin function, while others are not.

In conclusion, we have found that assessment of CSF 5HIAA and MAOA-uVNTR genotypes enables us to identify a group of men in whom there is a clustering of adverse levels of hostility, psychosocial, metabolic and CV endophenotypes that would be expected to increase risk of developing CV disease as well as Type II diabetes. The association of high and low scores on Factor 2 with CSF 5HIAA and MAOA-uVNTR patterns that reflect low and high levels of CNS serotonin function, respectively, could account for the previously reported (18, 19) associations of high hostility with components of the metabolic syndrome. And finally, the current findings are consistent with the previously stated hypothesis that the clustering of adverse behavioral and biological characteristics observed in persons with high hostility levels “could be the result of a single underlying neurochemical condition: deficient central nervous system (CNS) serotonergic function.” (24, 25)

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding: This work was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant P01HL36587 (RBW), Clinical Research Unit grant M01RR30, and the Duke University Behavioral Medicine Research Center.

Disclosures: Redford Williams holds a patent on use of 5HTTLPR L allele as a marker of increased CVD risk due to stress; Redford Williams is a founder and major stockholder in Williams LifeSkills, Inc.

Abbreviations used within the text

- MAOA

monoamine oxidase A

- CSF

cerebrospinal fluid

- 5HIAA

5-hydroxyindoleacetic acid

- CNS

central nervous system

- CHD

coronary heart disease

- GCRC

General Clinical Research Center

- SCID

structured interview for depression

- SD

standard deviation

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to the subject matter of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- 1.Williams RB, Haney TL, Lee KL, Blumenthal JA, Kong Y. Type A behavior, hostility, and coronary atherosclerosis. Psychosom Med. 1980;42:539–549. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198011000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barefoot JC, Dahlstrom WG, Williams RB. Hostility, CHD incidence, and total mortality: A 25-year follow-up study of 255 physicians. Psychosom Med. 1983;45:59–63. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198303000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shekelle RB, Gale M, Ostfeld AM, Paul O. Hostility, risk of coronary disease, and mortality. Psychosom Med. 1983;45:219–228. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198305000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dembroski T, MacDougall J, Costa P, Grandits G. Components of hostility as predictors of sudden death and myocardial infarction in the Multiple Risk Factor Intervention Trial. Psychsom Med. 1989;51:514–522. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198909000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chida Y, Steptoe A. The association of anger and hostility with future coronary heart disease: A meta-analytic review of prospective evidence. J Am Col Cardiology. 2009;53:936–946. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boyle SH, Williams RB, Mark DB, Brummett BH, Siegler IC, Barefoot JC. Hostility, age, and mortality in a sample of cardiac patients. Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:64–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2005.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boyle SH, Williams RB, Mark DB, Brummett BH, Siegler IC, Helms MJ, Barefoot JC. Hostility as a predictor of survival in patients with coronary artery disease. Psychosom Med. 2004 Sep-Oct;66(5):629–32. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000138122.93942.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Williams RB, Barefoot JC, Blumenthal JA, Helms MJ, Luecken L, Pieper CF, Siegler IC, Suarez EC. Psychosocial correlates of job strain in a sample of working women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:543–548. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830180061007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barefoot JC, Peterson BL, Dahlstrom WG, Siegler IC, Anderson NB, Williams RB., Jr Hostility patterns and health implications: Correlates of Cook-Medley Hostility scale scores in a national survey. Health Psychol. 1991;10:18–24. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.1.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matthews KA, Kelsey SF, Meilahn EN, et al. Educational attainment and behavioral and biologic risk factors for coronary heart disease in middle-aged women. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129:1132–1144. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a115235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan GA. Where do shared pathways lead? Some reflections on a research agenda. Psychosom Med. 1995;57:208–212. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199505000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scherwitz KW, Perkins LL, Chesney MA, Hughes GH, Sidney S, Manolio TA. Hostility and health behaviors in young adults: the CARDIA study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:136–145. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Siegler IC, Peterson BL, Barefoot JC, Williams RB. Hostility during late adolescence predicts coronary risk factors at midlife. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:146–154. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suarez EC, Kuhn CM, Schanberg SM, Williams RB, Zimmermann EA. Neuroendocrine, cardiovascular, and emotional responses of hostile men: The role of interpersonal challenge. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:78–88. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199801000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Markovitz JH. Hostility is associated with increased platelet activation in coronary heart disease. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:586–591. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199809000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Musselman DL, Miller AH, Porter MR, Manatunga A, Gao F, Penna S, Pearce BD, Landry J, Glover S, McDaniel JS, Nemeroff CB. Higher than normal plasma interleukin-6 concentrations in cancer patients with depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1252–1257. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rothermundt M, Arolt V, Peters M, Gutbrodt H, Fenker J, Kersting A, Kirchner H. Inflammatory markers in major depression and melancholia. J Affect Disorders. 2001;63:93–102. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00157-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Surwit RS, Williams RB, Siegler IC, Lane JD, Helms M, Applegate KL, Zucker N, Feinglos MN, McCaskill CM, Barefoot JC. Hostility, race, and glucose metabolism in nondiabetic individuals. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:835–839. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.5.835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niaura R, Banks SM, Ward KD, Stoney CM, Spiro A, 3rd, Aldwin CM, Landsberg L, Weiss ST. Hostility and the metabolic syndrome in older males: the normative aging study. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:7–16. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200001000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leboyer M, Bellivier F, Nosten-Bertrand M, Jouvent R, Pauls D, Mallet J. Psychiatric genetics: search for phenotypes. Trends Neurosci. 1998;21:102–105. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01187-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lucki I. The spectrum of behaviors influenced by serotonin. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:151–62. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ramage AG. Central cardiovasclar regulation and 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors. Brain Res Bull. 2001;56:425–39. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00612-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horacek J, Kuzmiakova M, Hoschi C, Andel M, Bahbonh R. The relationship between central serotonergic activity and insulin sensitivity in healthy volunteers. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1999;24:785–97. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4530(99)00026-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams RB. Neurobiology, cellular and molecular biology, and psychosomatic medicine. Psychosom Med. 1994;56:308–315. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199407000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Williams RB. Lower socioeconomic status and increased mortality. Early childhood roots and the potential for successful interventions. JAMA. 1998;279:1745–1746. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.21.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muldoon MR, Sved AF, Flory JD, Perel JM, Matthews KA, Manuck SB. Inverse relationship between fenfluramine-induced prolactin release and blood pressure in humans. Hypertension. 1998;32:972–5. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.32.6.972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muldoon MF, Mackey RH, Williams KV, Korytkowski MT, Flory JD, Manuck SB. Low centeral nervous system serotonergic responsivity is associated with the metabolic syndrome and physical inactivity. J Clin Endocrinology Metabolism. 2004;89:266–71. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stanley M, Traskman-Benz L, Dorovini-Zis K. Correlations between aminergic metabolites simultaneously obtained from human CSF and brain. Life Sci. 1985;37:1279–1286. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(85)90242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Doudet D, Hommer D, Higley JD, Andreason PJ, Moneman R, Suomi SJ, Linnoila M. Cerebral glucose metabolism, CSF 5-HIAA levels, and aggressive behavior in rhesus monkeys. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1782–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.12.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Higley JD, Linnoila M. Low central nervous system serotonergic activity is traitlike and correlates with impulsive behavior. A nonhuman primate model investigating genetic and environmental influences on neurotransmission. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1997;29:39–56. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb52354.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Roy A, Adinoff B, Linnoila M. Acting out hostility in normal volunteers. Negative correlation with levels of 5-HIAA in cerebrospinal fluid. Psychiatry Res. 1988;24:187–194. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(88)90061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ballenger J, Goodwin FK, Major LF, Brown GL. Alcohol and central serotonin metabolism in man. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1979;36:224–227. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1979.01780020114013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams RB, Marchuk DA, Gadde KM, Barefoot JC, Grichnik K, Helms MJ, Kuhn CM, Lewis JG, Schanberg SM, Stafford-Smith M, Suarez EC, Clary GL, Svenson IK, Siegler IC. Serotonin-Related gene polymorphisms and central nervous system serotonin function. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2003;28:533–541. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Valley CM, Willard HF. Genomic and epigenomic approaches to the study of X chromosome inactivation. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16:240–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burroughs AR, Visscher WA, Haney T, Efland JR, Barefoot JC, Williams RB, Siegler IC. Community recruitment process by race, gender and SES gradient: Lessons learned from the Community Health and Stress Evaluation (CHASE) study experience. J Community Health. 2003;28:421–437. doi: 10.1023/a:1026029723762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nordin C, Lindstrom L, Wieselgren IM. Acid monoamine metabolites in the CSF of healthy controls punctured without preceding strict bedrest: A retrospective study. J Psychiatr Res. 1996;30:127–133. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(95)00038-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rimmler J, McDowell G. Development of a data coordinating center (DCC): Data quality control for complex disease studies. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;63:240–6. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sabol SZ, Hu S, Hamer D. A functional polymorphism in the monoamine oxidase A gene promoter. Hum Genet. 1998;103:273–279. doi: 10.1007/s004390050816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doudet D, Hommer D, Higley JD, Andreason PJ, Moneman R, Suomi SJ, Linnoila M. Cerebral glucose metabolism, CSF 5-HIAA levels, and aggressive behavior in rhesus monkeys. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1782–7. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.12.1782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barefoot JC, Dodge KA, Peterson BL, Dahlstrom WG, Williams RB. The Cook-Medley hostility scale: Item content and ability to predict survival. PSYCHOSOMATIC MEDICINE. 1989;51:46–57. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198901000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buss AH, Perry M. The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1992;63:452–459. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.63.3.452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roy A, Adinoff B, Linnoila M. Acting out hostility in normal voluteers: negative correlation with levels of 5HIAA in cerebrospinal fluid. Psychiatry Res. 1988;24:187–194. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(88)90061-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weiner D. Subtle and obvious keys for the MMPI. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1948;12:164–170. doi: 10.1037/h0055594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beck AT, Ward CB, Mendelson M, Mock J, Erbaugh J. An inventory for Measuring Depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:53–61. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anda R, Williamson D, Jones D, Macera C, Eaker E, Glassman A, Marks J. Depressed Affect, Hopelessness, and the Risk of Ischemic Heart Dissease in a Cohort of U.S. Adults. Epidemiology. 1993;4:285–294. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199307000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Costa PT, McCrae RR. NEO-PI-R Professional Manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berkman L, Breslow L, Wingard D. Health practices and mortality risk. In: Berkman L, Breslow L, editors. Health and ways of living The Alameda County Study, (pp 61-112) New York: Oxford University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cohen S, Hoberman HM. Positive events and Social Support as Buffers of Life Change Stress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1983;13:99–125. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schier MF, Carver CS. Optimism, coping and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavoral Sciences. New York: Academic Press; 1969. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoll M, Cowley AW, Tonellato PJ, et al. A genomic-systems biology map for cardiovascular function. Science. 2001;294:1723–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1062117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]