SUMMARY

In this investigation, we report on 4 patients affected by incomplete partition type I submitted to cochlear implant at our institutions. Preoperative, surgical, mapping and follow-up issues as well as results in cases with this complex malformation are described. The cases reported in the present study confirm that cochlear implantation in patients with incomplete partition type I may be challenging for cochlear implant teams. The results are variable, but in many cases satisfactory, and are mainly related to the surgical placement of the electrode and residual neural nerve fibres. Moreover, in some cases the association of cochlear nerve abnormalities and other disabilities may significantly affect results.

KEY WORDS: Cochlear implant, Gusher, Incomplete partition, Inner ear malformations

RIASSUNTO

In questo articolo vengono descritte le problematiche e i risultati riguardanti la procedura di impianto cocleare in quattro pazienti affetti da partizione incompleta tipo I, sottoposti ad impianto cocleare nel nostro reparto. Le problematiche pre-operatorie, chirurgiche, di mappaggio e riguardanti il follow-up, così come i risultati vengono affrontate e discusse. I casi riportati nel presente articolo confermano che la procedura di impianto cocleare in pazienti affetti da partizione incompleta tipo I può rappresentare una sfida per i teams che si occupano di impianto cocleare. I risultati sono variabili, ma in molti casi soddisfacenti e sono soprattutto in relazione al posizionamento intra-cocleare dell'elettrodo e ai residui neurali. Inoltre in alcuni casi i risultati possono essere fortemente condizionati dall'associazione di anomalie del nervo acustico e dalla presenza di disabilità associate alla sordità.

Introduction

About 20% of children with sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) have associated malformations of the temporal bone 1, and increased experience in cochlear implantation has led to more children with abnormal cochleo-vestibular anatomy submitted to this procedure.

In 1987, Jaekler et al. proposed a classification of cochleo- vestibular malformations based on politomography and related to embryological genesis 2. More recently, in 2002, Sennaroglu and Saatci suggested an extension based on computed tomography (CT) findings, and provided a detailed classification of cochlear malformations, which is particularly important in the field of cochlear implantation 3. The malformation known as Mondini deformity was defined as incomplete partition (IP) and two types of IP were described by the authors: IP type I and type II 3. Recently, X-linked deafness has been recognized as a third type of IP: IP type III 4.

IP type I is described as "cochleo-vestibular malformation": the cochlea resembles an empty cyst as it lacks the entire modiolus and interscalar septa. It is associated with a large vestibule, while the enlargement of the vestibular aqueduct is rare 3 5. There is a defect between the internal auditory canal (IAC) and the cochlea 3 5.

In the IP type II, the cochlea has the modiolus only at the level of the basal turn and is associated with an enlarged vestibule and vestibular aqueduct. The medial and apical turns are fused into a cystic cavity and the corresponding modiolus and interscalar septa are defective. The external dimensions of the cochlea in IP type I and II are normal, according to Sennaroglu 5 6.

In the IP type III, the interscalar septa are present, but the modiolus is completely absent. The cochlea is placed directly at the lateral end of the IAC instead of its usual antero-lateral position. The external dimensions of the cochlea are also normal in this type of anomaly 4 6.

IP type I patients suffer from profound SNHL and gain little benefit from traditional hearing aids; thus, cochlear implantation is an option in these individuals 7-10. Cochlear implantation in malformed cochlea, and in particular in IP type I, poses greater than normal challenges for cochlear implant (CI) teams, with regards to surgical difficulties as facial nerve anomalies and gusher occurrence, choice and placement of the electrode and post-operative increased risk of meningitis.

In this investigation, we describe 4 cases of IP type I submitted to CI; pre-operative, surgical, programming and follow- up issues as well as results are described. The main clinical data and surgical issues are summarized in Table I.

Table I.

Main surgical issues and clinical data of the cases reported.

| Aetiology | CHARGE syndrome (1 case) Syndromic (1 case) Idiopathic (2 cases) |

| Facial nerve course | Anomalous (2 cases) |

| Cochlear nerve/IAC | Normal (3 cases) Hypoplastic (1 case) |

| Surgical access | Posterior tympanotomy (3 cases) Combined transcanal and posterior tympanotomy (1 case) |

| Round window anatomy | Normal (3 cases) Antero-inferiorly and medially located (1 case) |

| Type of electrode | Nucleus straight (4 cases) |

| Gusher-Oozer | 2 cases |

| Cochleostomy closure/gusher resolution | Temporalis fascia and muscle, with resolution of the gusher (2 cases) |

| Post-operative X ray/petrous bone CT | Good position of the array electrode (4 cases) |

| Post-op meningitis/other complications | No |

| Results | Good in 2 cases, poor in 2 cases |

Case reports

Case 1

G.R., male, was born at term after an uneventful pregnancy. The child was affected by profound SNHL diagnosed at 3 months of life after newborn hearing screening and audiological evaluation. The child was fitted with hearing aids and submitted to speech therapy at 5 months of age. The family history was negative for hearing loss. Any known cause of hearing loss was excluded, including mutations of Connexin 26, Connexin 30, A1555G mutation of mitochondrial DNA and mutations of PDS gene. The karyotype was normal.

Audiological evaluation included Auditory Brainstem Potentials (ABRs), that were not evocable at maximum stimulation levels, otoacoustic emissions that were absent bilaterally, behavioural audiometry without hearing aids, that revealed a profound hearing loss with residual hearing only at low frequencies, behavioural audiometry with hearing aids that revealed a poor gain and impedance audiometry. Tympanometry was bilaterally normal and stapedial reflexes were bilaterally absent at maximum stimulation levels. Speech perception tests with hearing aids revealed detection of voice only at high stimulation levels and no discrimination of words.

The child was a candidate for a CI procedure. Pre-operative radiological evaluation was carried out by means of petrous bone high resolution CT and inner ear and brain magnetic resonance (MR) with gadolinium enhancement with a 3 Tesla machine. Radiological evaluation showed the presence of an empty cystic cochlea and a completely absent modiolus bilaterally, indicating IP type I (Fig. 1a). No other malformations of the inner ear were detected, and the eight nerves were bilaterally normal as well as the brain. The child had vaccinations for Pneumococcus and Haemophilus influenzae.

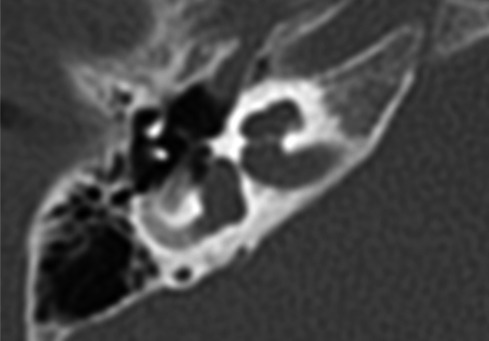

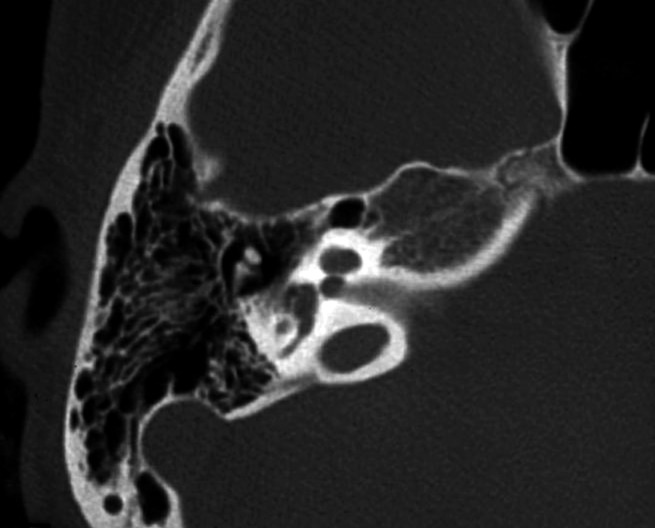

Fig. 1:

A. pre-operative CT of the temporal bone, axial plane in case 1. The cochlea is cystic and the modiolus is totally absent. B. post-operative CT of the temporal bone showing the correct position of the array in the cystic cochlea in the same case.

The child was submitted to CI procedure at 13 months of age, through a facial recess approach. The facial nerve course and the round window anatomy were normal. After the opening of the cochlea, through a small (1 mm) promontorial cochleostomy antero-inferiorly to the round window, a mild pulsating gusher (oozing) 5 occurred. It resolved after the insertion of the array. A straight array with full band electrodes CI24RE(ST) (Cochlear, Australia) was used; the insertion of the array was complete. Close attention was paid to accurately close the cochleostomy with temporalis fascia shaped around the electrode array and muscle. Intraoperative neural response telemetry showed normal responses and the compound action potential (CAP) of the acoustic nerve was evoked by all the tested electrodes. At the end of surgery, the child was submitted to a skull X-ray, confirming correct placement of the array.

Post-implantation results are very good. At 2.5 years after implantation, the speech recognition score in open set is 100% without lip-reading, and oral language skills are improving.

A petrous bone CT, carried out some weeks after surgery, revealed a correct position and no kinking of the array electrode (Fig. 1b).

Case 2

F.V., female, was born at term after an uneventful pregnancy. She was not submitted to newborn hearing screening. The child was affected by CHARGE syndrome and was heterozygous for the mutation c.3379- 1_3385dupGGAACACA in exon 14 of the CHD7 gene. She presented cardiopathy, mild mental retardation and a mood and behavioural disorder as a part of the syndrome. A profound SNHL was diagnosed at 14 months of age.

The child was fitted with hearing aids and submitted to speech therapy at 15 months of age. The family history was negative for hearing loss. Any other known cause of hearing loss had been previously excluded, including mutations of Connexin 26, Connexin 30 and A1555G mutation of mitochondrial DNA. When the child was 3 years and 6 months old, her parents referred to our centre seeking cochlear implantation.

The audiological evaluation included ABRs, that were not evocable at maximum stimulation levels, otoacoustic emissions that were absent bilaterally, behavioural audimetry without hearing aids that revealed a profound hearing loss with residual hearing only at low frequencies, behavioural audiometry with hearing aids that revealed a poor gain and impedence audiometry. Tympanometry was bilaterally normal and stapedial reflexes were bilaterally absent at maximum stimulation levels. Speech perception tests revealed no detection of sounds and voice.

Pre-operative radiological evaluation was carried out by petrous bone high resolutaion CT and petrous bone and brain MR with gadolinium enhancement on a 3 Tesla machine. The radiological evaluation showed the presence of a cystic cochlea, with a basal turn partially formed (Fig. 2) and a completely absent modiolus bilaterally, indicating IP type I. The lateral semicircular canals were hypoplastic bilaterally; the eight nerves were bilaterally normal as well as the brain. The child had vaccinations for Pneumococcus and Haemophilus influenzae.

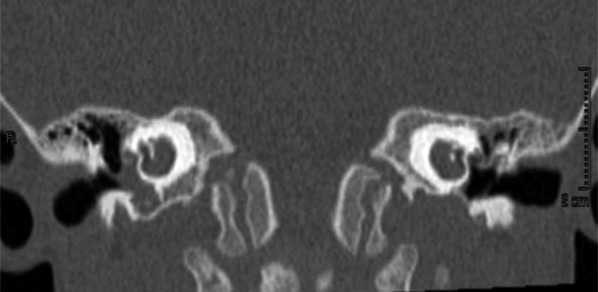

Fig. 2.

Pre-operative CT of the temporal bone, coronal plane in case 2. The modiolus is completely absent, and the basal turn is partially formed.

The child was submitted to CI procedure at 3 years and 8 months of age through a facial recess approach. The facial nerve course was abnormal, being the second and third segment antero-inferiorly displaced. The round window anatomy was normal. A straight array with full band electrodes CI24RE(ST) (Cochlear, Australia) was fully inserted through a small (1 mm) promontorial cochleostomy antero-inferiorly to the round window. No gusher occurred. Much attention was paid to accurately close the cochleostomy with temporalis fascia shaped around the electrode array and muscle.

Intraoperatively neural response telemetry showed the CAP only for the central electrodes and not for the basal and apical ones, while postoperatively the CAP was evoked by all the electrodes along the array. A post-operative skull X-ray, performed at the end of surgery, and CT of the temporal bone, carried out some weeks later, revealed a correct position and no kinking of the array electrode.

Post-implantation results are good. At 1.5 years after implantation, the child is able to identify words in a closed and open set. The child is also able to understand simple phrases and orders. Oral language is very poor and limited to single words.

Case 3

T.A., female, was born at term after an uneventful pregnancy. She was not submitted to newborn hearing screening. The child was affected by SNHL associated to Arnold Chiari type I malformation, vertebral anomalies and mild mental retardation. A profound SNHL was diagnosed at 2.5 years of age. The child was fitted with hearing aids and submitted to speech therapy at 2.5 years of age. The family history was negative for hearing loss. Any other known cause of hearing loss was excluded, including mutations of Connexin 26, Connexin 30 and A1555G mutation of mitochondrial DNA. Karyotype was normal. The child's parents referred to our centre seeking for cochlear implantation.

The audiological evaluation included ABRs that were not evocable at maximum stimulation levels, otoacoustic emissions that were absent bilaterally, behavioural audiometry without hearing aids that revealed a profound hearing loss with residual hearing only at low frequencies, behavioural audiometry with hearing aids that revealed a poor gain and impedence audiometry. Tympanometry was bilaterally normal and stapedial reflexes were bilaterally absent at maximum stimulation levels. Speech perception tests revealed no detection of sounds and voice.

Pre-operative radiological evaluation was carried out by petrous bone high resolution CT and petrous bone and brain MR with gadolinium enhancement using a 3 Tesla machine. The radiological evaluation showed the presence of a cystic cochlea, with a basal turn partially formed and a totally absent modiolus bilaterally, indicating IP type I. The vestibule was bilaterally enlarged, the right lateral semicircular canal was absent, the left one was hypoplasic and the vestibular aqueduct was bilaterally enlarged. The eight nerve was bilaterally hypoplasic, being the left one better visible and with a larger diameter. The child had vaccinations for Pneumococcus and Haemophilus influenzae.

The child was submitted to CI procedure on the left at 3 years of age through a facial recess approach. The facial nerve course and the round window anatomy were both normal. A straight array with full band electrodes CI24RE(ST) (Cochlear, Australia) was fully inserted through a promontorial cochleostomy antero-inferiorly to the round window. No gusher occurred. Close attention was paid to accurately close the cochleostomy with temporalis fascia shaped around the electrode array and muscle.

Intraoperatively neural response telemetry showed the CAP only for the central electrodes at very high stimulation levels and not for the basal and apical ones, while postoperatively the CAP was not evoked for any of the electrodes along the array. An X-ray of the skull, carried out at the end of surgery, confirmed the correct position of the array (Fig. 3).

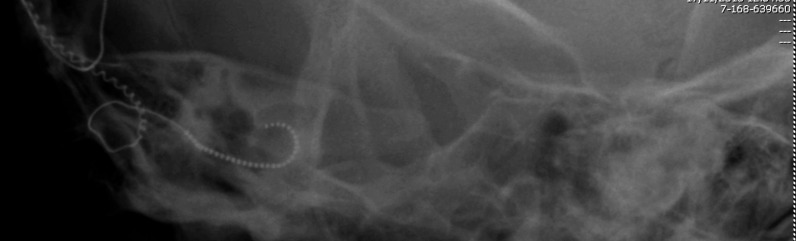

Fig. 3.

Post-operative X ray of the skull showing the correct position of the array in case 3.

After surgery, high stimulation levels and long pulse width were required to evoke an auditory sensation. Postimplantation results are poor and slow. At 1.5 years after implantation the child able to detect sounds and voice and to discriminate sounds. Auditory performance is slowly improving, but oral language development is very poor and limited to a few single words.

Post-operative CT of the temporal bone at 1 year after implantation confirmed the correct position of the array in the malformed cochlea.

Case 4

I.A., female, was born at term after an uneventful pregnancy. She did not undergo hearing screening and severe bilateral SNHL was diagnosed at 3 years of age. The child was then fitted with hearing aids and submitted to speech therapy. Family history was negative and any known case of hearing loss was excluded.

The patient was referred to our centre at 6 years of age, seeking a CI. The audiological evaluation included ABRs that were not evocable at maximum stimulation levels, otoacoustic emissions that were absent bilaterally, behavioural audiometry without hearing aids that revealed a profound hearing loss with residual hearing only at low frequencies, behavioural audiometry with hearing aids that revealed a poor gain and impedence audiometry. Tympanometry was bilaterally normal and stapedial reflexes were bilaterally absent at maximum stimulation levels. Speech perception tests revealed only detection of voice at high levels. She presented mild mental retardation.

Pre-operative radiological evaluation was carried out with HRCT and MR with gadolinium enhancement with a 1.5 Tesla machine. Both CT scan and MR showed a cystic dysplastic cochlea with partially formed basal turn and a totally absent modiulus bilaterally. The posterior labyrinth was normal. The images suggested an IP type I malformation (Fig. 4). The child had vaccinations for Pneumococcus and Haemophilus influenzae.

Fig. 4.

CT of the temporal bone, axial plane, in case 4. The cochlea is cystic and the modiolus is completely absent.

The child was submitted to left CI at 6 years of age through a facial recess approach. The facial nerve course was very lateral and anteriorly dislocated and the round window was medially located. A combined trans-mastoid and trans-canal approach was therefore necessary. A straight array with full band electrodes CI24RE(ST) (Cochlear, Australia) was fully inserted through a small (1 mm diameter) anterior-inferior cochleostomy drilled transcanally. A perilymph oozing occurred, but close attention was paid to accurately close the cochleostomy with temporalis fascia shaped around the electrode array and muscle. Intraoperative impedance measurement was normal for all electrodes. A post-operative Stenver's X-ray of the skull was executed at the end of surgery, confirming the correct position of the array.

A post-operative petrous bone CT showed a correct position and no kinking of electrodes. Psychoacoustic electrical map showed an average T-level of 136 CL and an average C-level of 176 CL.

Post-implantation results were poor. At one year after implantation, free field audiometry showed an average threshold of 40 dB HL, but the patient is only able to detect sound and voice. Oral language development is limited to single words.

Discussion

Increased experience in cochlear implantation has led to more children with anomalous vestibulo-cochlear anatomy being considered as candidates. Nevertheless, some important issues concerning the procedure must be considered and pre-operatively accurately planned. Cochlear implantation in IP type I patients is not widely reported in the literature. Sennaroglu reported on 14 patients with this malformation submitted to CI, describing surgical difficulties 6. More recently, Kontorinis et al. reported on 49 patients with IP, finding more surgical difficulties in those with IP type I than in those with IP type II 11. Papsin had previously reported on surgical issues and results of 42 patients with IP, but no distinction between IP type I and II was made 12. We believe this distinction is particularly important for surgical management and results. IP type I is a more severe cochlear malformation than type II, as the cochlea is a cystic empty cavity, with wide communication between the cochlear base and the IAC; the facial nerve course is often anomalous, sometimes preventing a standard surgical approach to the cochlea. The modiolus is totally lacking and residual neural activity is very poor, and this may affect the results. In contrast, in IP type II the basal turn is formed and the modiolus is present at that level; this is generally related to some residual hearing and progressive hearing loss, allowing generally good results after implantation 6.

The results of cochlear implantation in cases with inner ear malformations are generally good and appear to be related to the history of hearing loss, the degree of malformation and residual neural function 6 12.

Surgery may be challenging in patients with IP type I. Most of the cases can be done via a classical transmastoid- facial recess approach, but in some cases this is not possible due to anomalous facial nerve course. As such, an alternative transcanal approach can be used as reported by Sennaroglu (2010) in two cases 4 6. In addition, Kim et al. (2006) reported a case of IP type I with the facial nerve dislocated anteriorly, preventing the use of a facial recess approach 13. Severe facial nerve anomalies are described in patients with inner ear malformations and for this reason facial nerve monitoring should be used in all CI surgery in the malformed inner ear. Aberrant course of the facial nerve in IP type I is probably not directly related to cochlear malformation, but to the associated enlarged vestibule and anomalous lateral semicircular canal 6.

In three of our four cases, we used a standard transmastoid- facial recess approach; nevertheless, in one case (case 2) the second and third portion of the facial nerve was anteroinferiorly displaced making it difficult to visualize the round window and the cochleostomy site, and in one case a transcanal approach was needed.

In IP type I cochleae, the modiolus is entirely lacking, and the exact location of the ganglion cells is not exactly known, although it is generally on the outer wall 14. For these reasons, straight arrays with circumferential electrodes are preferred to stimulate as much neural tissue as possible. Moreover, Eisenman et al. (2001) suggested using uncoiled unfocused electrodes 10. If a Contour electrode is used, it is better to not remove the stylet. In all the cases herein, we used a straight array with circumferential electrodes.

In IP type I, an aggressive attempt at full insertion of the array may result in misplacement through the deficient modiolus into the IAC; Chadha et al. (2009) overcame this risk by using a straight electrode array gently pushed against the promontory before insertion into the cochleostomy to create a slight curvature over the first 3-5 electrodes. It is our opinion that this allows to steer the electrode array toward the hypothetical modiolus and avoid misplacement into the IAC 15. In the cases herein, we performed a cochleostomy antero-inferiorly to the round window niche, at the level of the crista fenestrae, as previously described 16. This approach allows a direct view of the basal turn, minimizing the risk of misplacement of the electrode. The post-operative X-ray showed good positioning of the electrode in the cystic cochleas. We also performed post-operative CT of the temporal bone in all patients, which confirmed the correct position of the array in the cochleae. Misplacement of the electrode array in the IAC did not occur in any case, as demonstrated by post-operative CT.

Another important issue concerning CI in inner ear malformation, and particularly in IP type I, is the higher incidence of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) gusher, reported in 40-50% of surgeries. The occurrence of CSF gusher is difficult to pre-operatively predict, and sometimes in spite of a wide defect at the lateral end of the IAC, no gusher occurs upon opening the inner ear, probably due to fibrous tissue bands separating the IAC from the labyrinth 4. Kontorinis et al. report that among patients with IP, those with IP type I are more at risk of intraoperative CSF gusher, due to the larger bony defect in the lamina cribrosa 11. None of the 14 IP type I patients implanted by Sennaroglu (2010) had CSF gusher 6. Similar results have been reported by Beltrame et al (2005) 17, Manolidis et al. (2006) 18, McElveen et al. (1997) 19 and Mylanus et al. (2004) 20. In two of our cases, a minimal gusher or oozer occurred that successfully resolved after the insertion of the electrode array. In our cases, a small cochleostomy with 1 mm diameter was made to reduce the risk of CSF leakage. After the insertion of the array, great attention was paid to accurately close the cochleostomy with temporalis fascia shaped around the array electrode and small pieces of temporalis muscle. In this regard, Sennaroglu (2010) proposed a designed and special electrode, with a "cork" feature at the level of the silicon ring that marks the end of the insertion, in order to prevent CSF leakage after electrode insertion 6.

In cases of gusher during CI, Weber et al. (1997) recommended a small cochleostomy, allowing the electrode to partly block the flow of CSF, reinforced by connective tissue, muscle and fibrin glue 21, while Graham et al (2000) suggested a large cochleostomy, which allows easy insertion of the electrode and easier introduction of muscle around the electrode 22.

CI surgery in inner ear malformation is among the most important causes of otogenic recurrent meningitis; CSF fistula in inner ear malformations is associated with recurrent meningitis.

Indeed, IP type I patients are at higher risk of recurrent meningitis due to CSF fistulas as the modiolus and the cribriform plate are absent, resulting in a wide defect between the IAC and the cystic cochlea 6. The majority of fistulas are located at the stapes footplate, and only occasionally at the level of the cochleostomy. Page and Eby (1997) reported a case of meningitis in an implanted patient after minor head trauma in a child with a malformation resembling IP type I malformation; in this case, CSF leakage was identified at the cochleostomy around the electrode of the implant 23. Recently, Sennaroglu reported a case with IP type I with meningitis in the nonoperated ear due to a defect at the level of the stapes footplate 6, demonstrating that meningitis in such cases is not always related to the implant. Pre-operative vaccinations for Pneumococcus and Haemophilus influenzae are recommended for all CI candidates, but have particular relevance for patients with inner ear malformations. None of the cases reported herein experienced post-operative meningitis; all received vaccinations for Pneumococcus and Haemophilus influenzae.

The results after implantation in patients with IP type I are not well-known as a few cases are reported in the literature. Papsin (2005) reported on 42 patients with IP: speech perception scores in IP patients were higher in comparison to those of implanted children with other inner ear malformations, such as common cavity and cochlear hypoplasia, due to the higher amount of residual nerve fibres and to the progression of hearing loss, but no distinction between IP type I and type II was made 12. In addition, Buchman et al. reported better results in patients with IP compared to patients with other malformations, without distinguishing between the two types of IP 24. Nevertheless, Kontorinis et al. reported better results in patients with IP type I than in patients with IP type II 11. Two of the cases (case 1 and 2) reported in the present paper achieved good results, while in two cases (case 3 and 4) the results were poorer. Case 3 presented hypoplasia of the eight nerve bilaterally, and we believe that this played an important role in the outcome achieved; moreover, both cases 3 and 4 presented other negative factors affecting the results, such as a late diagnosis and hearing aid fitting, with long-term hearing deprivation, low socio-economic level and bilingualism. Finally, another important factor affecting the results is the presence of other disabilities associated with deafness, as in cases 2, 3 and 4, who all presented mild mental retardation 9 10 25.

Considering mapping difficulties in patients with inner ear malformations, and specifically in patients with IP type I, there are a few studies. Papsin (2005) reported that patients with cochleo-vestibular anomaly generally present fitting difficulties, such as low dynamic range, instable maps and facial nerve stimulation, especially if affected by common cavity and cochlear hypoplasia 12. Among patients with inner ear malformations, these problems may be less important in IP patients 12. Among the cases herein reported, we experienced mapping difficulties only for patient 3, who presented a hypoplastic nerve associated with IP type I; in this case, high levels of stimulation and a high pulse width were required. We believe this iwas related to hypoplasia of the acoustic nerve more than to the IP.

Conclusions

The cases reported herein confirm that patients with IP type I are suitable for cochlear implantation, even if the procedure may be challenging for CI teams. Accurate preoperative radiological evaluation with high resolution CT and MR is mandatory to assess the facial nerve course, exact internal structure of the cochlea and te anatomy of the IAC and cochlear nerve. The surgeon should be ready to face an anomalous facial nerve course and lack of landmarks that could require modifications in the surgical approach, perilymphatic gusher and difficulties in inserting the electrode with risk of misplacement in the IAC. The results are variable, but in many cases satisfactory, and appear to be mainly related to the surgical placement of the electrode and residual neural nerve fibres. Moreover, in some cases anomalies of the cochlear nerve and associated disabilities may be present, both of which significantly affect the results. Post-operatively, strict follow up is necessary for the risk of meningitis due to CSF fistula that in most of cases seems to be fenestral.

References

- 1.Mc Clay JE, Tandy R, Grundfast K, et al. Major and minor temporal bone abnormalities in children with and without congenital sensorineural hearing loss. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;128:664–671. doi: 10.1001/archotol.128.6.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackler RK, Luxford WM, House WF. Congenital malformations of the inner ear: a classification based on embryogenesis. Laryngoscope. 1987;97:2–14. doi: 10.1002/lary.5540971301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sennaroglu L, Saatci I. A new classification for cochleovestibular malformations. Laryngoscope. 2002;112:2230–2241. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200212000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sennaroglu L, Sarac S, Ergin T. Surgical results of cochlear implantation in malformed cochlea. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27:615–623. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000224090.94882.b4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sennaroglu L, Saatci I. Unpartitioned versus incompletely partitioned cochleae: radiologic differentiation. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:520–529. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200407000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sennaroglu L. Cochlear implantation in inner ear malformations - a review article. Cochlear Implants Int. 2010;11:4–41. doi: 10.1002/cii.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turchetti G, Bellelli S, Palla I, et al. Systematic review of the scientific literature on the economic evaluation of cochlear implants in paediatric patients. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2011;31:311–318. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berrettini S, Baggiani A, Bruschini L, et al. Systematic review of the literature on the clinical effectiveness of the cochlear implant procedure in adult patients. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2011;31:299–310. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forli F, Arslan E, Bellelli S, et al. Systematic review of the literature on the clinical effectiveness of the cochlear implant procedure in paediatric patients. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2011;31:281–298. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berrettini S, Arslan E, Baggiani A, et al. Analysis of the impact of professional involvement in evidence generation for the HTA Process, subproject "cochlear implants": methodology, results and recommendations. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 2011;31:273–280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kontorinis G, Goetz F, Giourgas A, et al. Radiological diagnosis of incomplete partition type I versus type II: significance for cochlear implantation. Eur Radiol. 2012;22:525–532. doi: 10.1007/s00330-011-2301-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Papsin BC. Cochlear implantation in children with anomalous cochleovestibular anatomy. Laryngoscope. 2005;115 :1–26. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200501001-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim LS, Jeong SW, Huh MJ, et al. Cochlear implantation in children with inner ear malformations. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2006;115:205–214. doi: 10.1177/000348940611500309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eisenman DJ, Ashbaugh C, Zwolan TA, et al. Implantation of the malformed cochlea. Otol Neurotol. 2001;22:834–841. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200111000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chadha NK, James AL, Gordon KA, et al. Bilateral cochlear implantation in children with anomalous cochleovestibular anatomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135:903–909. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berrettini S, Forli F, Passetti S. Preservation of residual hearing following cochlear implantation: comparison between three surgical techniques. J Laryngol Otol. 2008;122:246–252. doi: 10.1017/S0022215107000254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beltrame MA, Frau GN, Shanks M, et al. Double posterior labyrinthotomy technique: results in three Med-El patients with common cavity. Otol Neurotol. 2005;26:177–182. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200503000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Manolidis S, Tonini R, Spitzer J. Endoscopically guided placement of prefabricated cochlear implant electrodes in a common cavity malformation. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70:591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.ijporl.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mc Elveen JT, Jr, Carrasco VN, Miyamoto RT, et al. Cochlear implantation in common cavity malformations using a transmastoid labyrinthotomy approach. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:1032–1036. doi: 10.1097/00005537-199708000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mylanus EA, Rotteveel LJ, Leeuw RL. Congenital malformation of the inner ear and pediatric cochlear implantation. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:308–317. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200405000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Weber BP, Lenarz T, Dillo W, et al. Malformations in cochlear implant patients. Am J Otol. 1997;18:S64–S65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Graham JM, Phelps PD, Michaels L. Congenital malformations of the ear and cochlear implantation in children: review and temporal bone report of common cavity. J Laryngol Otol Suppl. 2000;25:1–14. doi: 10.1258/0022215001904842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Page EL, Eby TL. Meningitis after cochlear implantation in Mondini malformation. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;116:104–106. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Buchman CA, Teagle HFB, Roush PA, et al. Cochlear implantation in children with labyrinthine anomalies and cochlear nerve deficiency: implications for auditory brainstem implantation. Laryngoscope. 2011;121:1979–1988. doi: 10.1002/lary.22032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palmieri M, Berrettini S, Forli F, et al. Evaluating benefits of cochlear implantation in deaf children with additional disabilities. Ear Hear. 2012;33:721–730. doi: 10.1097/AUD.0b013e31825b1a69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]