Abstract

The Omaha system is one of the most widely used interface terminologies for documentation of community-based care. It is influential in disseminating evidence-based practice and generating data for health care quality research. Thus, it is imperative to ensure that the Omaha system reflects current health care knowledge and practice. The purpose of this study was to evaluate free text associated with Omaha system terms to inform issues with electronic health record system use and future Omaha system standard development. Two years of client records from two diverse sites (a skilled homecare, hospice, and palliative care program and a maternal child health home visiting program) were analyzed for the use of free text as a component of the intervention when structured targets for interventions were not identified. Intervention text entries very commonly contained duplicate “carry forward entries”, multiple concepts, mismatched problem focus, or failure to identify an existing appropriate target. Our findings support the need to better address education gaps for clinicians. We identified additional suggested targets for Omaha system problems, and propose new targets for consideration in future Omaha system revisions.

Keywords: Interface terminology, Omaha system, Content coverage, community health care, nursing assessment

As the overall footprint of healthcare continues to transition from the acute to ambulatory or community-based settings, community-based electronic health record (EHR) systems and interface terminologies will be increasingly used for the documentation and analysis of society’s healthcare. The Omaha system is an interface terminology that represents one of the most widely used classifications within community care. The Omaha system is designed to comprehensively describe client health and to produce meaningful information through its three components: problem classification scheme, intervention scheme, and problem rating scale for outcomes. Currently the Omaha system is used by over 11,000 practitioners in 14 countries through 400 organizations [1] as a means of describing client knowledge, behavior, and status for multiple aspects of health [2].

A majority of research with the Omaha system analyzed associated structured data recorded during client encounters, which compose the bulk of the Omaha System classification [3]. This associated research has been used to understand care trends [4, 5], effectuate the principles of “meaningful use” in community-based care settings [6, 7], and assess patient outcomes [8–12]. As such, the use of interface terminologies with standardized representations within community-based EHR systems can enable accurate and useful healthcare documentation which, in turn, improves patient safety and quality measurement [13]. This effort is part of a larger one aimed at better understanding and utilizing text data with community-based documentation using automated medical natural language processing (NLP) tools.

Others have demonstrated that different types of clinical text can represent sublanguages with distinct characteristics compared to other types of medical text [15, 16]. Community-based and nursing text has been understudied within the medical NLP literature, but several groups have started to look at extracting information from text documenting nursing outcomes and interventions [17] and also for mapping to nursing terminologies [18, 19]. Recently, we described our analysis of the text with the Omaha system associated with signs and symptoms and found user-related issues including the need for more extensive user education with system use and the use “workarounds” with documentation of signs and symptoms. In addition, we proposed several modifications for signs and symptoms in future Omaha system revisions [20].

The goal of the current project is to analyze text associated with Omaha system interventions. In the Omaha system, interventions are defined as activities or actions implemented to address a specific client problem and to improve, maintain or restore health or prevent illness [2]. An intervention statement comprises standardized terms for a problem, a category (action), a target, and a care description.

Problems (n = 42) specify the focus of the intervention (e.g. Pain, Circulation, Nutrition). The categories are four broad actions that provide a structure for describing clinicians’ actions or activities. These categories are teaching, guidance and counseling (TGC), treatment and procedures (TP), case management (CM), and surveillance (S). Targets (n = 75) are defined terms that can be used to further describe interventions in the form of a clinician’s actions or activities. While structured data is critical for automated use by computer systems, text is integral for inter-clinician documentation and tailoring of care. Text adds contextual information for care and research as it allows clinicians to express sophisticated concepts such as clinical interpretation, reasoning, and timing [14].

There is one target which is not defined, called “other”. This target enables free text entry at the target level of the intervention statement. Finally, the care description is a detailed, customizable portion of a plan or intervention statement that can be developed and documented by the clinician [2]. Thus, in addition to structured entry with the Omaha system (problem-category-target), clinicians also have the option to enter free-text during clinical documentation at the target and care description levels to fill information gaps and provide clinical reasoning.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to evaluate free text associated with Omaha system terms to inform issues with electronic health record system use and future Omaha system standard development. Our specific aim was to identify duplicate “carry forward entries”, multiple concepts, mismatched problem focus, or failure to identify an existing appropriate target, and to identify unique new target concepts that could enhance documentation if included in the Omaha system. We hypothesized that text associated with interventions would contain valuable information relevant to the use of EHR documentation systems and to inform ongoing development of the Omaha system terminology. A fuller understanding of the issues encountered with electronic systems and this particular taxonomic documentation standard may help with our understanding of user needs, education gaps, and other issues integral to the classification system itself.

Methods

A multi-disciplinary team in the University of Minnesota School of Nursing and Institute for Health Informatics collaborated on this research as a follow up study to our previous analysis of text entries for ‘other’ signs and symptoms in the Omaha system [20]. Electronic data were obtained from two community based settings: a maternal child health home visiting program at Washington County Public Health, and a skilled homecare, hospice, and palliative care program at Fairview HomeCaring & Hospice. Both community partners use CareFacts™ [St. Paul, Minnesota], a software system that implements the Omaha system for documentation. CareFacts implements the suggested targets provided for each problem, category, and care description combination from the Omaha System user guide [2] and also allows for users to select any target deemed appropriate.

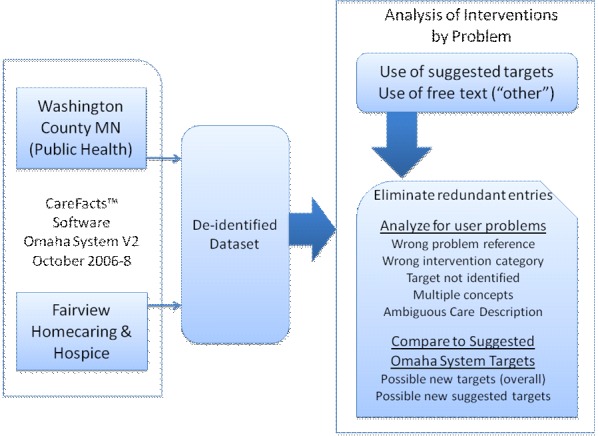

Both user sites agreed to provide structured intervention data over a 2 year period (October 2006–8). After University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board approval was obtained, Care-Facts™ provided a de-identified dataset from both user sites (►Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Overview of methods

Interventions where clinicians used one of the 74 defined targets (not ‘other’) and where there was at least one unique text entry for the care description note associated with ‘other’ as the target were included in the analysis. The interventions were chosen based on the presence of unique text entries in the care description notes as these were used in the analysis to understand the rationale behind the clinicians’ choices of the ‘other’ target over the recommended targets.

Entries were characterized into several overlapping categories: duplicate entry, mismatched problem, mismatched category, target not identified by user, multiple concepts, and ambiguous care description. In the CareFacts™ software, when a visit is created, the active care plan is carried forward from one visit to the next, resulting in duplicate information/entries. This process streamlines documentation but results in duplicate data entries. These duplicate entries were eliminated to generate the frequency of unique entries in care description notes associated with ‘other’ as the target.

Unique care description entries were then analyzed to understand user issues and characterization of entries within the Omaha system framework. Mismatched problem entries were care descriptions that referred to another problem focus and were not relevant to the particular problem. When text entries represented the mismatched intervention category based on the Omaha system definitions these entries were classified as “mismatched intervention category”. Entries where an appropriate target within the Omaha system existed but was not identified by the user (an instead free text was entered) were classified as “target not identified”.

Entries that contained conceptually multiple concepts (multiple targets, intervention categories and/or problems) were classified as “multiple concepts”. Care descriptions that could not be deciphered in terms of the appropriate target, category, problem, or care plan were classified as “ambiguous care descriptions”. Finally, all care description text entries were compared to all 74 defined targets and to the suggested targets for each problem to help identify possible new or modified targets for future Omaha system revisions.

The free text associated with these unique ‘other’ target entries were reviewed over a series of group sessions with four research members experienced in nursing (BW, KM), public health (BW, KM), homecare (BW, KM), health informatics (GM, OF, BW, KM), and medicine (GM, OF). All differences of opinion were settled by group consensus. Descriptive statistics were calculated from this data.

Results

Over the two-year period of the study, there were 6,680 visits (1,079 clients, median age 16 years, 77% female) in public health and 55,021 visits (2,309 clients, median age 70 years, 62% female) in the homecare, hospice, and palliative setting. Twenty-six problems with at least one unique text entry associated with the ‘other’ target were included in the analysis. Initial examination of the study data revealed that 41,273 (99.97%) of the 41,287 entries of ‘other’ target came from the homecare, hospice, and palliative site with a very small number coming from the public health site. Therefore data obtained from the homecare, hospice and palliative site were the main focus of this study.

►Table 1 summarizes frequency of interventions ‘other’ target entries by problem. For almost all problems, the ‘other’ target was entered in a small proportion of clinical encounters. The frequency of unique entries in the care description notes associated with the ‘other’ target was calculated for each problem. Duplicate entries ranged from 0–99%, with the total duplicate entries comprising 91% of the target “other” text entries (►Table 1). The wide range of duplicate entries resulted in an uneven distribution of entries for the target ‘other’ among problems. Problems such as growth and development, postpartum, substance use, role change and mental health had less than 10 entries for the target ‘other’, while problems like medication regimen, skin, pain and neuro-musculo-skeletal function had more than 5000 entries for the target ‘other’.

Table 1.

Frequencies of suggested and other targets by problem. † = Number of interventions for each problem (* = number of interventions using target other for each problem; NMS = neuro-musculo-skeletal; a = health care supervision; b= growth and development).

| Problem | Interventions Total | Interventions with Target ‘Other’ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N† | All Interventions (%) | N* | All target “other” (%) | Interventions for problem (%) | Duplicate care descriptions (N) | Duplicate care description (%) | |

| Medication Regimen | 221917 | 25.3 | 17228 | 41.7 | 7.8 | 15482 | 89.9 |

| Pain | 137421 | 15.7 | 6259 | 15.2 | 4.6 | 5847 | 93.4 |

| Caretaking/parenting | 127825 | 14.6 | 11 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 6 | 54.5 |

| NMS function | 73861 | 8.4 | 5716 | 13.8 | 7.7 | 4913 | 86.0 |

| Skin | 52810 | 6.0 | 6443 | 15.6 | 12.2 | 6237 | 96.8 |

| Hlthcare supervisiona | 36000 | 4.1 | 1957 | 4.7 | 5.4 | 1824 | 93.2 |

| Growth and Devptb | 34937 | 4.0 | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Nutrition | 28632 | 3.3 | 41 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 32 | 78.0 |

| Pregnancy | 23367 | 2.7 | 13 | 0.03 | 0.06 | 9 | 69.2 |

| Respiration | 20635 | 2.4 | 1257 | 3.0 | 6.1 | 1117 | 88.9 |

| Circulation | 20022 | 2.3 | 1138 | 2.8 | 5.7 | 1126 | 98.9 |

| Mental health | 16677 | 1.9 | 7 | 0.02 | 0.04 | 5 | 71.4 |

| Substance Abuse | 16268 | 1.9 | 5 | 0.01 | 0.03 | 4 | 80.0 |

| Bowel function | 13997 | 1.6 | 187 | 0.5 | 1.3 | 143 | 76.5 |

| Postpartum | 12183 | 1.4 | 2 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1 | 50.0 |

| Interpersonal | 9791 | 1.1 | 29 | 0.07 | 0.3 | 27 | 93.1 |

| Residence | 9564 | 1.1 | 165 | 0.4 | 1.7 | 161 | 97.6 |

| Urinary Function | 7486 | 0.9 | 218 | 0.5 | 2.9 | 186 | 85.3 |

| Personal Care | 3552 | 0.4 | 31 | 0.08 | 0.9 | 29 | 93.5 |

| Digestion-Hydration | 3474 | 0.4 | 320 | 0.8 | 9.2 | 212 | 66.3 |

| Communication | 3214 | 0.4 | 13 | 0.03 | 0.4 | 11 | 84.6 |

| Cognition | 2510 | 0.3 | 119 | 0.3 | 4.7 | 97 | 81.5 |

| Speech | 342 | 0.04 | 87 | 0.2 | 25.4 | 71 | 81.6 |

| Sanitation | 199 | 0.02 | 18 | 0.04 | 9.0 | 16 | 88.9 |

| Hearing | 90 | 0.01 | 16 | 0.04 | 17.8 | 15 | 93.8 |

| Role change | 55 | 0.01 | 6 | 0.01 | 10.9 | 5 | 83.3 |

| Total | 876829 | 100.00 | 41287 | 100.00 | 37576 | 91.1 | |

►Table 2 summarizes the unique ‘other’ target findings from our analysis. Of the 225 unique entries, most commonly the user did not identify and enter an existing Omaha system target (209, 93%), while entries with multiple concepts (35, 16%) and mismatched intervention categories (30, 13%) occurred next most frequently. For example, interventions for the digestion-hydration problem had 13 unique care descriptions for the ‘other’ target, with 7 of these care descriptions referring to either the ‘nutrition’ or ‘bowel function’ problem. Also, a significant proportion of care descriptions for the ‘health care supervision’ problem were care plans with multiple aspects that represented multiple concepts, targets, and some ambiguity.

Table 2.

Frequencies for use of the target “other” entries by problem (*blank unique text entries for care description excluded;. a = health care supervision; b = growth and development).

| Problem | *Unique “Other” target entries | Mismatched Problem | Mismatched Intervention Category | Target Not Identified | Multiple Concepts | Ambiguous Care Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medication Regimen | 42 | 1 | 1 | 41 | 2 | 3 |

| Pain | 14 | - | 2 | 9 | - | 5 |

| Caretaking/parenting | 5 | - | - | 5 | - | - |

| NMS function | 10 | - | - | 9 | 1 | 4 |

| Skin | 17 | 1 | 4 | 17 | 4 | 2 |

| Hlth care supervisiona | 33 | 2 | 8 | 32 | 9 | 8 |

| Growth and Devptb | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Nutrition | 8 | - | 2 | 8 | 3 | - |

| Pregnancy | 4 | - | - | 4 | - | 1 |

| Respiration | 7 | - | 2 | 7 | 3 | - |

| Circulation | 16 | 1 | 1 | 15 | 2 | 1 |

| Mental health | 2 | - | - | 2 | - | - |

| Substance Abuse | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Bowel function | 7 | - | - | 7 | 2 | - |

| Postpartum | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Interpersonal | 2 | - | 1 | 2 | 1 | - |

| Residence | 5 | - | - | 5 | - | - |

| Urinary Function | 23 | - | 3 | 23 | 4 | 3 |

| Personal Care | 2 | - | - | 2 | - | - |

| Digestion-Hydration | 13 | 7 | 2 | 6 | - | - |

| Communication | 2 | - | 2 | 2 | - | - |

| Cognition | 5 | - | 1 | 5 | 1 | - |

| Speech | 1 | - | - | 1 | 1 | - |

| Sanitation | 2 | - | 1 | 2 | - | - |

| Hearing | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Role change | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Total | 225 | 12 | 30 | 209 | 35 | 27 |

►Table 3 details recommendations for modifications and proposed targets based on the free text associated with the target ‘other’. For example, we noted that a number of care descriptions with neuro-musculo-skeletal function and health care supervision problems involved interventions aimed at improving the client’s ability to carry out activities of daily living (ADLs), which currently is not a target in the classification. Also, a target concept not well covered by the classification involved the education of the pathophysiology of a medical condition. Currently, the Omaha system does not have targets for interventions focused on the description of the disease process. Overall, in most cases there did exist an Omaha system target appropriate for the care descriptions documented but the clinician did not identify an appropriate target.

Table 3.

Recommendations for modifications and suggested targets for the target ‘other’ entries.

| Problem | Example of Free Text | Category | Unique count | Total count | Additional Suggested Target for Problem-Category in User Guide | Proposed User Guide Modifications and New Targets |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Residence | Supervision of HSA (Health Service Aide) | CM | 5 | 165 | Homemaking/Housekeeping | |

| Sanitation | Assess Safety of environment for Staff and patient | S | 1 | 16 | Safety | |

| Caretaking/Parenting | Supervise HHA (Home Health Aide) per agency protocol | CM | 3 | 4 | Paraprofessional/aide care | |

| Interpersonal Relationship | Update family and/or staff every visit. Address any questions or concerns | CM | 1 | 14 | Continuity of care | |

| Communication with community resources | MSW (masters in social work) assess to help with advanced directive | S | 1 | 12 | Social work/counseling | |

| Growth and Development | Teach re:/refer to Follow Along Program | TGC and CM | 1 | 1 | Screening procedures | |

| Circulation | Supervision of HSA | CM | 1 | 24 | Paraprofessional/aide care | |

| Foot care | TP | 1 | 12 | Personal Hygiene | ||

| Bowel Function | Treatment and prevention of constipation | TGC | 1 | 14 | Bowel care and Dietary management | |

| NMS Function | GOAL; Act as liaison between prosthetist and patient--patient feels prosthesis is loose since hospitalization. Time frame: 3–4 weeks during PT interim | S | 1 | 1 | Continuity of care | The category should be CM |

| GOAL; Monitor compliance with „contract“ for ADUS-- including up and dressed in the morning with breakfast and medications | s | 2 | 2 | Behavior modification | Target may be modified to include ADLs or a new target for ADLs should be created | |

| NMS Function | GOAL: HHA will provide assist with personal cares as ordered. Supervise HHA as required. Time frame: ongoing | TP | 2 | 2323 | Paraprofessional/aide care | |

| Work with the client on massage and ice massage as needed for muscular spasm relief | TP | 1 | 7 | Physical therapy care | ||

| Pain | Teach pain management | TGC | 3 | 94 | Coping skills | A new target of pain management would improve specificity of the intervention |

| Teach alternative pain relief measures | TGC | 1 | 6109 | Relaxation/Breathing techniques | ||

| Skin | Refer to WOCN (Wound, Ostomy and continence nurse) prn (as required) | CM | 1 | 9 | Ostomy care | |

| Assess patient/caregiver ability to manage skin care | S | 1 | 51 | Skin care | ||

| Teach how to notify physician/RN with problem | TGC | 2 | 1189 | Communication | ||

| Teach 1) Balance of rest and activity2) Any restrictions as prescribed by MD | TGC | 1 | 2191 | Mobility/Transfer | ||

| Urinary Function | RN to supervise HHA | CM | 2 | 34 | Paraprofessional/aide care | |

| Assessment of incision site | S | 2 | 10 | Dressing change/wound care | ||

| Assess nutrition | S | 1 | 3 | Dietary management | ||

| Teach pt balance of rest and activity | TGC | 1 | 1 | Behavior modification | ||

| Nurse to instruct wife regarding proper care of nephrostomy tube drainage system | TGC | 1 | 3 | Ostomy care | ||

| Cognition | Assist family by providing information on community resources | CM | 1 | 4 | Communication | |

| Administer mini mental exam weekly | TP | 1 | 5 | Signs and symptoms mental/emotional | ||

| Hearing | Extreme hard of hearing; use pocket talker for all conversations with patient | TP | 1 | 16 | Durable medical equipment | |

| Pregnancy | Monitor compliance with activity restrictions | S | 1 | 3 | Mobility/Transfer | |

| Respiration | HHA to assist with personal care at each home visit | TP | 1 | 1 | Paraprofessional/aide care | |

| Speech | GOAL: Evaluate need for speech therapy intervention and assist in referral as appropriate. See speech therapy documentation for treatment plan and goals | CM and S | 1 | 87 | S&S- Physical and Continuity of care | The treatment plan should be divided into two targets- S&S- Physical (evaluate need for speech therapy) and Continuity of care (referral for care) |

| Healthcare supervision | Assign and supervise HHA plan of care | CM | 3 | 22 | Paraprofessional/aide care | |

| Assess client’s appetite and nutritional needs | S | 1 | 47 | Dietary management | ||

| Assess compliance with Hospice plan of care | S | 1 | 2 | End-of-life care | ||

| Nurse to monitor blood glucose readings at each visit and instruct client regarding diabetic cares as needed | S and TGC | 1 | 41 | Lab. Findings and Nursing care | Care plan should be divided into two targets-lab findings (monitor blood glucose) and nursing care (instructions for diabetic care) | |

| Nutrition/hydration; safety in home; ADL’s; med use | TGC | 1 | 1 | Medication administration and Safety, | Care plan involves multiple targets and possibly a new target for ADLs | |

| Teach client to observe for any sores | TGC | 1 | 11 | Dietary management | ||

| Teach disease process | TGC | 1 | 1 | S&S Physical | A new target for disease process may be necessary | |

| Teach how to meet care needs while in Hospice program | TGC | 3 | 1472 | Coping skills | ||

| B-12 injection monthly | TP | 1 | 6 | Medication Coordination/Ordering | ||

| Foot care | TP | 1 | 16 | Personal Hygiene | ||

| INR to be drawn per MD order | TP | 1 | 16 | Specimen Collection | ||

| RN to check vital signs | TP | 1 | 15 | S&S Physical | ||

| Wound care | TP | 1 | 2 | Dressing change/Wound care | ||

| Medication Regimen | Lab draws | TP | 2 | 12 | Specimen Collection | |

| Teach medications to family | TGC | 1 | 4 | Communication | ||

| Catheter urinary diversion | TP | 1 | 47 | Bladder Care | ||

| Obtain labs | TP | 1 | 1 | Laboratory findings | ||

| Remove PICC line | TP | 5 | 16 | Dressing change/Wound care | ||

| Nutrition | Diabetic cares and management PRN | TGC | 1 | 10 | Dietary Management | |

| Instruct patient and family on effects of tube feedings as cancer progresses. Discuss possible termination of feedings as disease progresses | TGC | 1 | 4 | Feeding procedures and End-of-life care | ||

| RN assess for nutritional status and teaching | TGC and S | 1 | 11 | S&S Physical | ||

| Substance Use | Teach and assess ways to manage anxiety | TGC | 1 | 5 | Stress Management |

Discussion

Community-based EHR systems will become increasingly important as healthcare continues to shift from the acute inpatient setting to outpatient, public-health, and homecare settings. Interface terminologies used in community settings are critical components of the EHR that will enable translation of evidence-based practice and generate data for health care quality improvement. While studies have traditionally utilized structured Omaha system data, investigators are beginning to look at the use of free-text within the context of the classification to help inform future revisions of the terminology and to uncover user issues with utilizing these systems. In this study, we looked at the use of text associated with Omaha system interventions in two diverse community-based settings.

The first notable finding was that text associated with interventions was almost exclusively at the skilled homecare, hospice, and palliative care site and almost never at the public health site. At the public health site, there was a concerted effort to implement and educate clinicians on rigorous use of the Omaha system, with attention to best use of targets as suggested in the Omaha system users guide and purposefully avoiding use of the target ‘other’ in structured intervention pathways.

This documentation practice resulted in very minimal use of target ‘other’ with these maternal-child home health interventions. In contrast, while the homecare, hospice, and palliative care site used pathways for some conditions, text was frequently used to document interventions. This was perhaps in part due to the complexity and variability of clients served by homecare, hospice and palliative care. They often have multiple co-morbid conditions, with the need to tailor interventions for care complexity. However, there may be a need for enhanced end-user training on the effective use of the Omaha system targets, how they are implemented in the software and the ability to tailor these most effectively. Clearer guidelines on use of pathway-based documentation standards can aid with improving documentation consistency and quality.

The target ‘other’ was frequently used to document a complex care plan containing multiple concepts (instead of creating several unique interventions). For example, the free text for one intervention addressing the health care supervision problem was “add phone follow-up between home visits to review emergent care plan” (category-S; target-medical/dental care), continue client/caregiver education regarding disease process (category-TGC; target-unknown), and assess status (category-S; targets-signs and symptoms-physical, and signs and symptoms-mental/emotional)”. This appears as a “work-around” to save time, however this practice presents challenges. If the clinician indicates that an intervention containing multiple tasks was completed, legally this would indicate that each of the tasks in an intervention was addressed, even if it was only partially completed.

There were also several notable examples of interventions having the mismatched problem focus or the user not identifying an existing Omaha system target and instead entering text. For example, clinicians had a hard time differentiating the scope of similar problems such as digestion-hydration, nutrition, and bowel function. Use of a standardized terminology requires considerable study and experience to attain fluency in correct use of terms. Agency support for user training is critical to successful documentation. In some cases, we identified conceptual gaps in the Omaha system targets. In particular, our data suggest that adding targets for activities of daily living, disease pathophysiology, and pain management in a future Omaha system revision. In a parallel study we proposed a conceptual framework for Omaha System targets to provide a foundation for revising the Omaha system targets. Within our proposed theoretical framework, activities of daily living is consistent with the client skills theme, disease pathophysiology is consistent with the client needs theme, and pain management is consistent with the type of care theme [21].

Our study is somewhat limited in its size and scope with only two years of data in two settings. Follow-up studies looking at Intervention text further in other setting will help to confirm our findings, along with identifying additional suggested refinements to the system based off of the needs and use of the Omaha system in other settings. In addition, the analysis of text entries was highly labor intensive and may be added with automated or semi-automated techniques as text-mining and other machine-learning techniques may be applied to streamline this process with future studies.

Conclusions

In this study, we analyzed Omaha system intervention text entries to inform our understanding of how an interface terminology is used for assessing interventions in community care. While the text associated with “other” targets carried some valuable information, these entries very commonly contained duplicate “carry forward entries”, multiple concepts, mismatched problem focus, or the user failed to identify an existing appropriate target. Our findings support the need to better address education gaps for clinicians and identified several areas where additional suggested targets for problems and new targets could be added to the Omaha system with future revisions.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the University of Minnesota Academic Health Center Seed Grant Program. We would also like to thank CareFacts™, Washington County Public Health, and Fairview HomeCaring & Hospice for their partnership in this research and assistance with data.

References

- 1.The Omaha System (Web site) from http://www.omahasystem.org Retrieved December 1, 2010

- 2.Martin KS. The Omaha System – A key to practice, documentation, and information management. 2nd ed: Saunders; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowles KH, Martin KS. Three decades of Omaha System research: Providing the map to discover new directions. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2006; 122: 994 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monsen KA, Fulkerson JA, Lytton AB, Taft LL, Schwichtenberg LD, Martin KS. Comparing maternal child health problems and outcomes across public health nursing agencies. Matern Child Health J 2010; 14: 412–421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Monsen KA, Westra BL, Yu F, Ramadoss VK, Kerr MJ. Data management for intervention effectiveness research: comparing deductive and inductive approaches. Res Nurs Health 2009; 32: 647–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Westra BL, Oancea C, Savik K, Marek KD. The feasibility of integrating the Omaha system data across home care agencies and vendors. Comput Inform Nurs 2010; 28: 162–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Martin KS, Monsen KA, Bowles KH. The Omaha system and meaningful use: applications for practice, education, and research. Comput Inform Nurs 2010; 29: 52–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westra BL, Solomon D, Ashley DM. Use of the Omaha System data to validate Medicare required outcomes in home care. J Healthc Inf Manag 2006; 20: 88–94 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Garvin JH, Martin KS, Stassen DL, Bowles KH. The Omaha System. Coded data that describe patient care. J AHIMA 2008; 79: 44–49; quiz 51–52 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu F, Lang NM. Using the Omaha System to examine outpatient rehabilitation problems, interventions, and outcomes between clients with and without cognitive impairment. Rehabil Nurs 2008; 33: 124–131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Westra BL, Savik K, Oancea C, Choromanski L, Holmes JH, Bliss D. Predicting improvement in urinary and bowel incontinence for home health patients using electronic health record data. Journal of Wounds, Ostomy, & Continence Nursing. Accepted 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westra BL, Dey S, Fang G, Steinbach M, Kumar V, Savik K, et al. Data mining techniques for knowledge discovery from electronic health records. Journal of Healthcare Engineering. Accepted2011; 2(1). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bates DW, Gawande AA. Improving safety with information technology. N Engl J Med 2003; 348: 2526–2534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel VL, Arocha JF, Kushniruk AW. Patients’ and physicians’ understanding of health and biomedical concepts: relationship to the design of EMR systems. J Biomed Inform 2002; 35: 8–16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morrison FP, Kukafka R, Johnson SB. Analyzing the structure and content of public health messages. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2005: 540–544 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stetson PD, Johnson SB, Scotch M, Hripcsak G. The sublanguage of cross-coverage. Proc AMIA Symp 2002: 742–746 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyun S, Johnson SB, Bakken S. Exploring the ability of natural language processing to extract data from nursing narratives. Comput Inform Nurs 2009; 27: 215–223; quiz 24–25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bakken S, Hyun S, Friedman C, Johnson S. A comparison of semantic categories of the ISO reference terminology models for nursing and the MedLEE natural language processing system. Stud Health Technol Inform 2004; 107: 472–476 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bakken S, Hyun S, Friedman C, Johnson SB. ISO reference terminology models for nursing: applicability for natural language processing of nursing narratives. Int J Med Inform 2005; 74: 615–622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Melton GB, Westra BL, Raman N, Monsen KA, Kerr MJ, Hart CH, et al. Informing standard development and understanding user needs with Omaha system signs and symptoms text entries in community-based care settings. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2010: 512–516 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Monsen KM, Melton-Meaux G, Timm J, Westra B, Kerr M, Raman N, Farri O, Hart C, Martin K. An empiric analysis of Omaha System Targets. Appl Clin Inf 2011; 2: 317–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]