Abstract

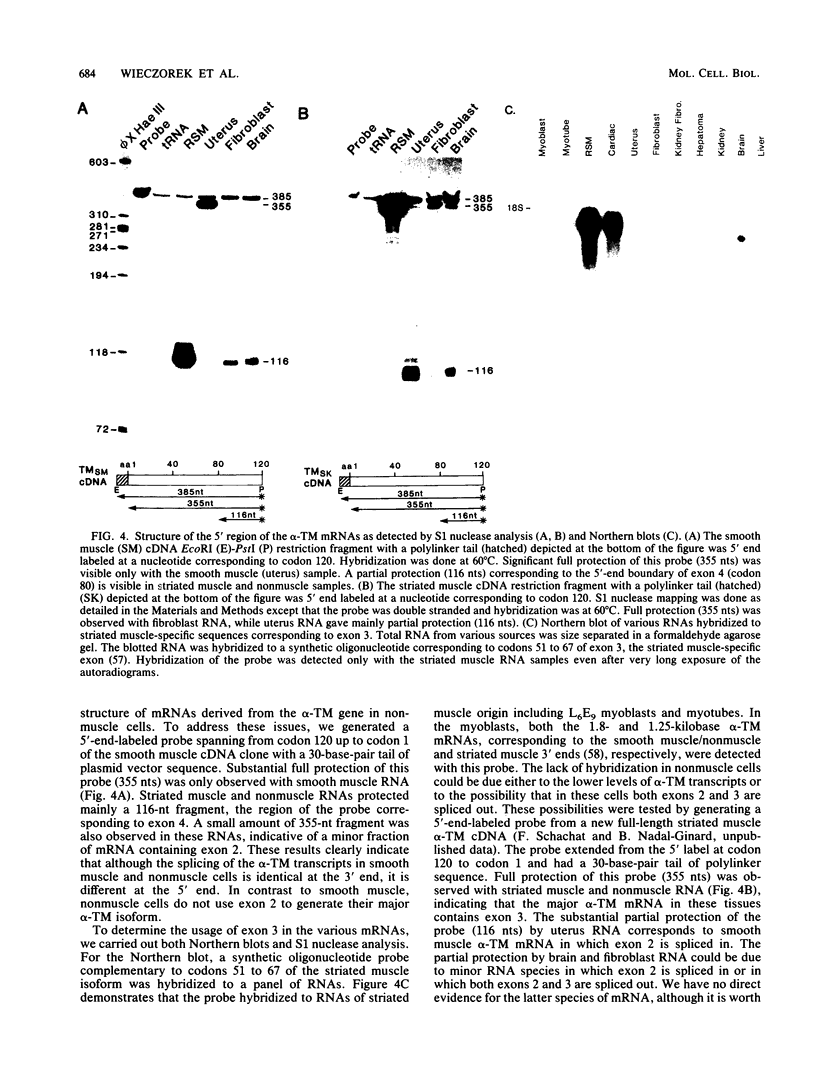

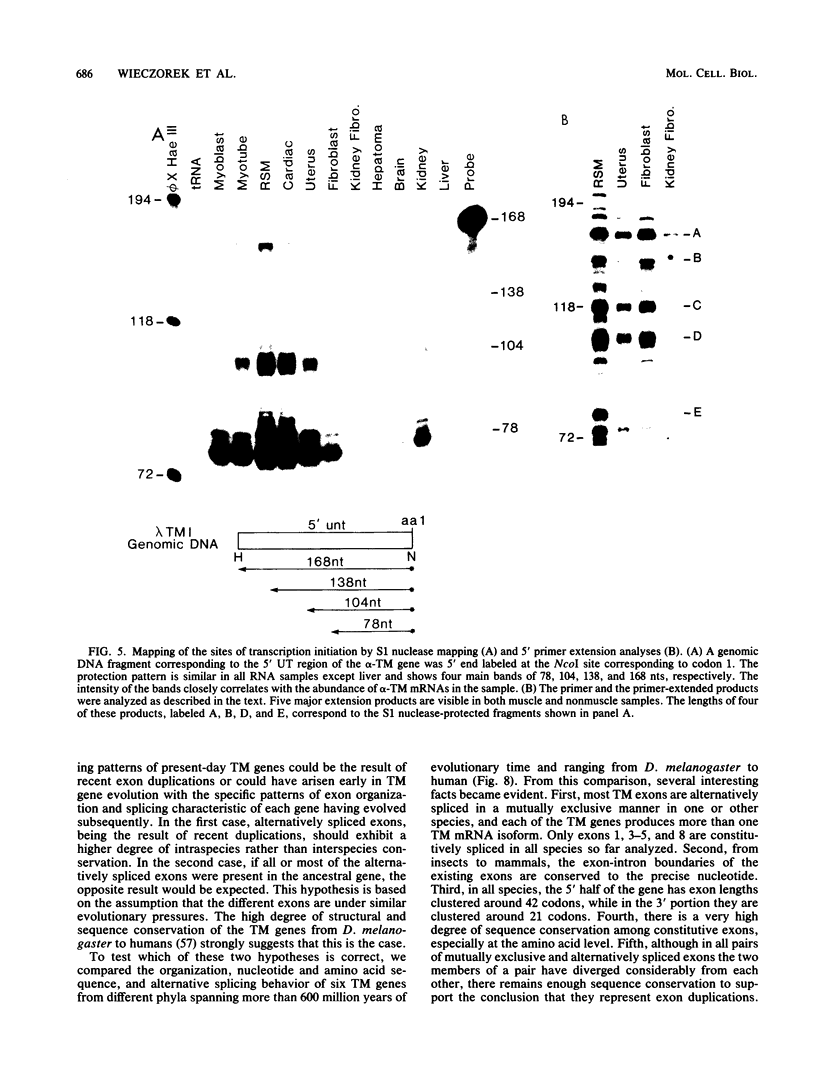

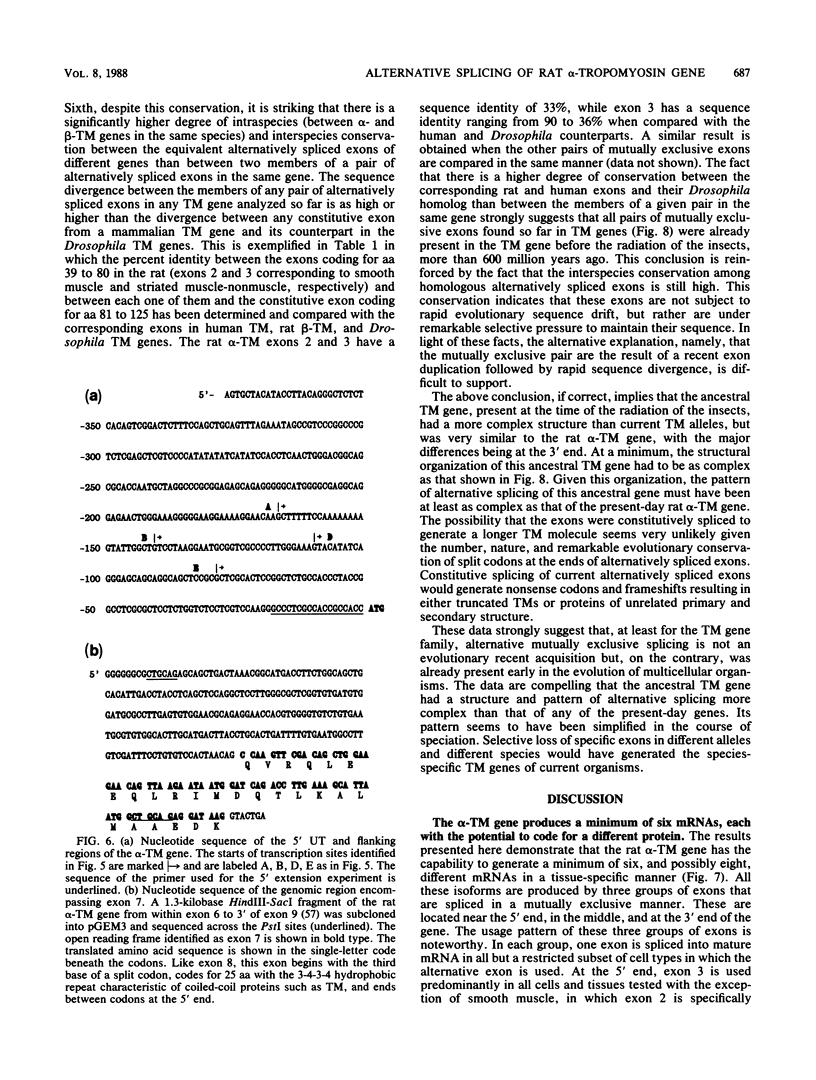

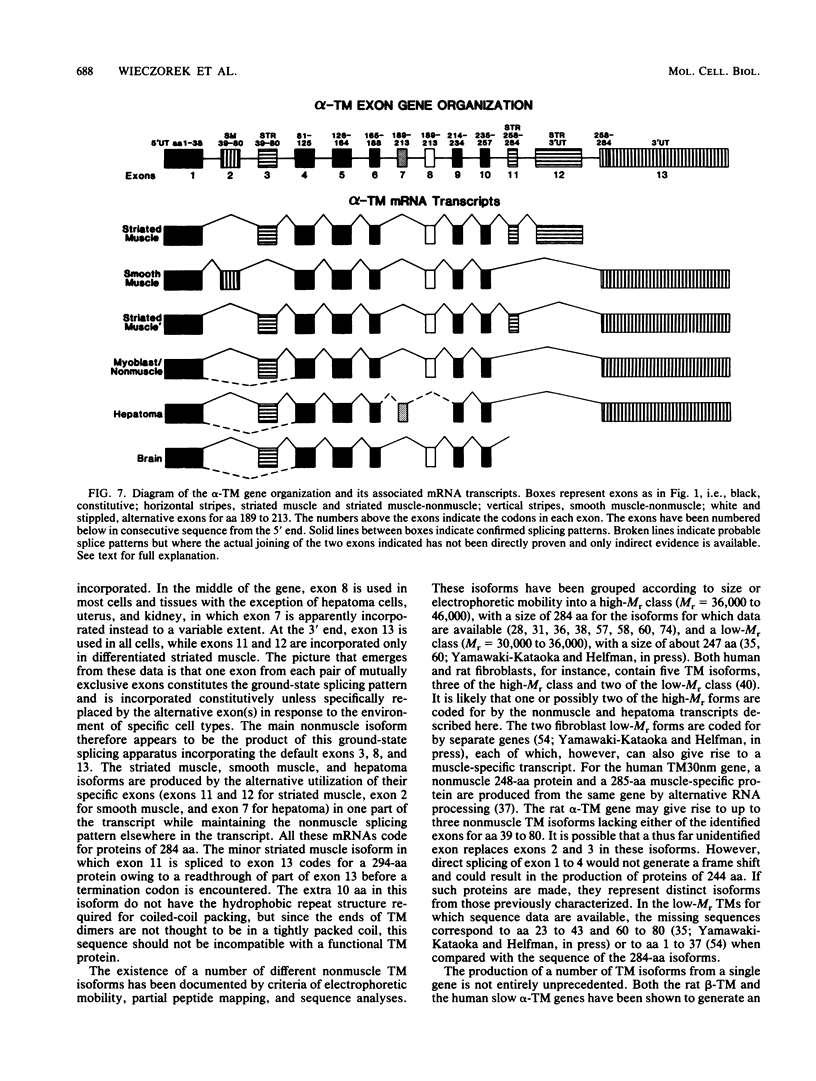

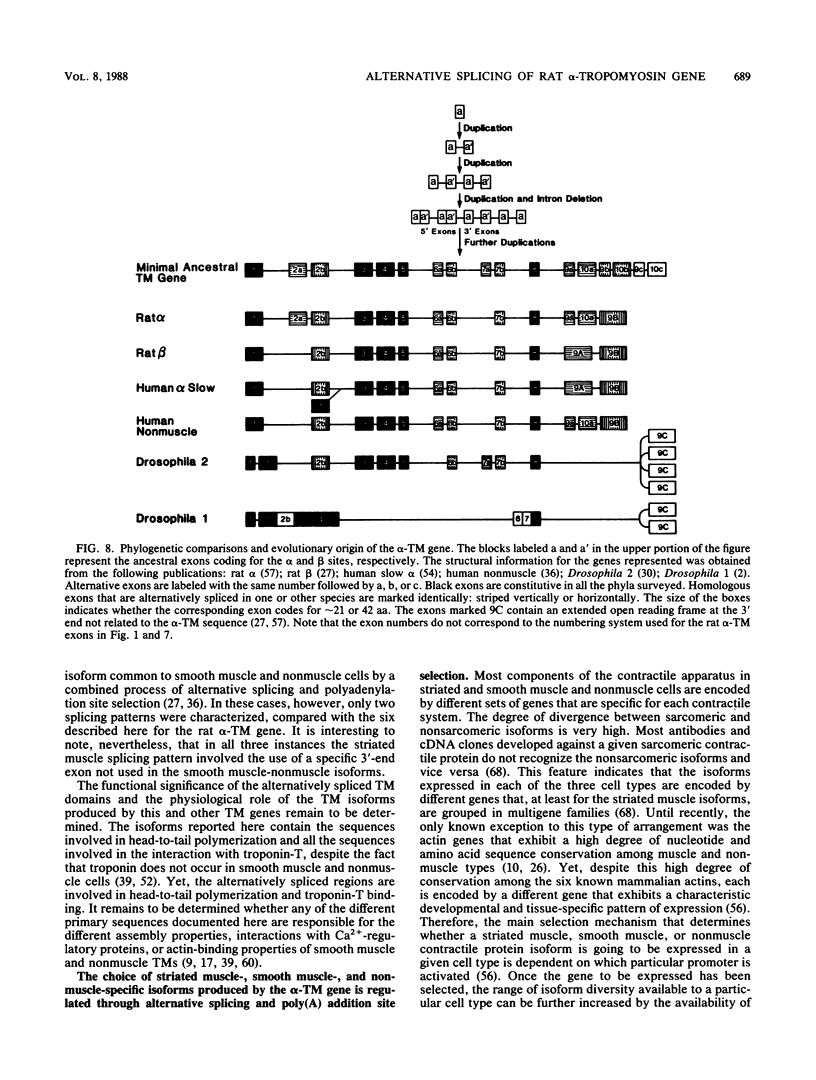

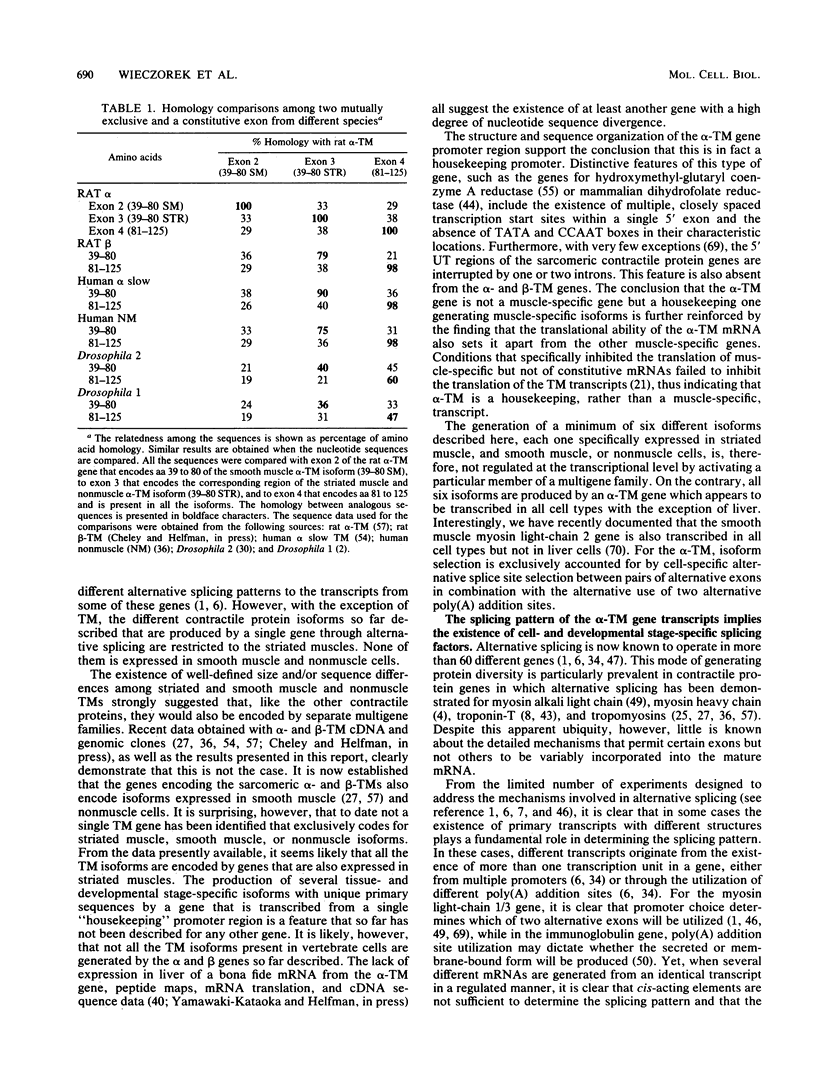

Tropomyosin (TM), a ubiquitous protein, is a component of the contractile apparatus of all cells. In nonmuscle cells, it is found in stress fibers, while in sarcomeric and nonsarcomeric muscle, it is a component of the thin filament. Several different TM isoforms specific for nonmuscle cells and different types of muscle cell have been described. As for other contractile proteins, it was assumed that smooth, striated, and nonmuscle isoforms were each encoded by different sets of genes. Through the use of S1 nuclease mapping, RNA blots, and 5' extension analyses, we showed that the rat alpha-TM gene, whose expression was until now considered to be restricted to muscle cells, generates many different tissue-specific isoforms. The promoter of the gene appears to be very similar to other housekeeping promoters in both its pattern of utilization, being active in most cell types, and its lack of any canonical sequence elements. The rat alpha-TM gene is split into at least 13 exons, 7 of which are alternatively spliced in a tissue-specific manner. This gene arrangement, which also includes two different 3' ends, generates a minimum of six different mRNAs each with the capacity to code for a different protein. These distinct TM isoforms are expressed specifically in nonmuscle and smooth and striated (cardiac and skeletal) muscle cells. The tissue-specific expression and developmental regulation of these isoforms is, therefore, produced by alternative mRNA processing. Moreover, structural and sequence comparisons among TM genes from different phyla suggest that alternative splicing is evolutionarily a very old event that played an important role in gene evolution and might have appeared concomitantly with or even before constitutive splicing.

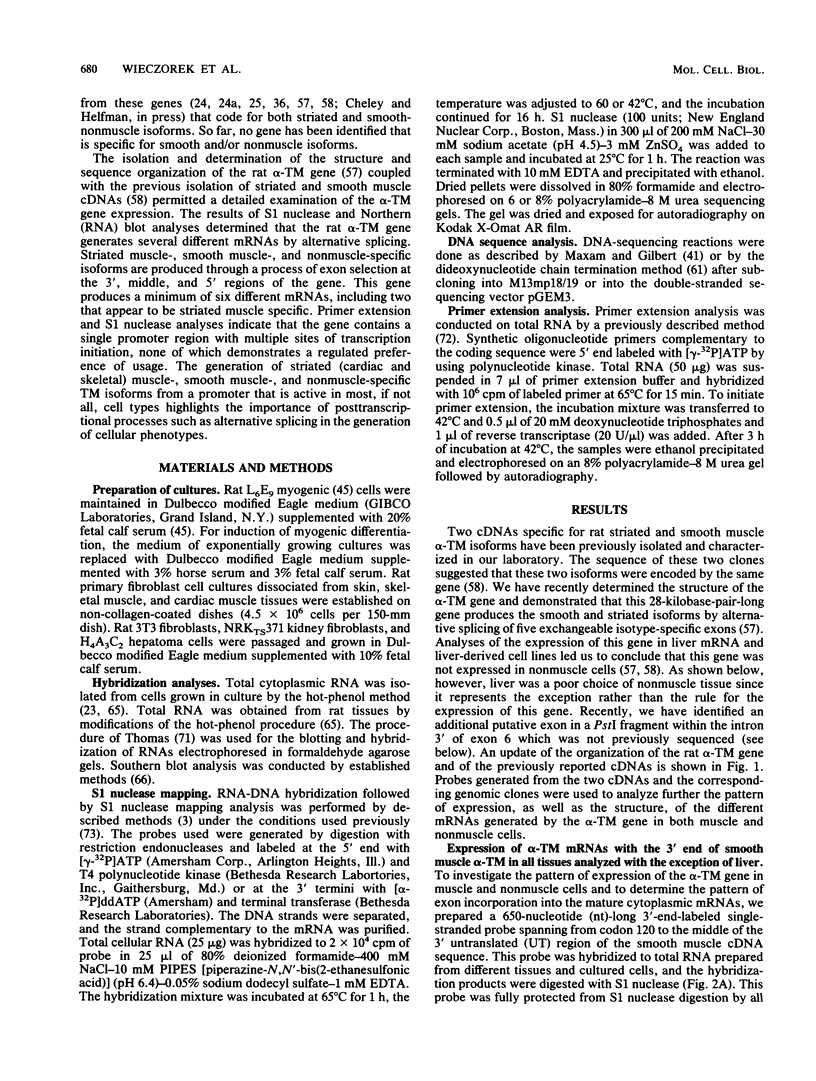

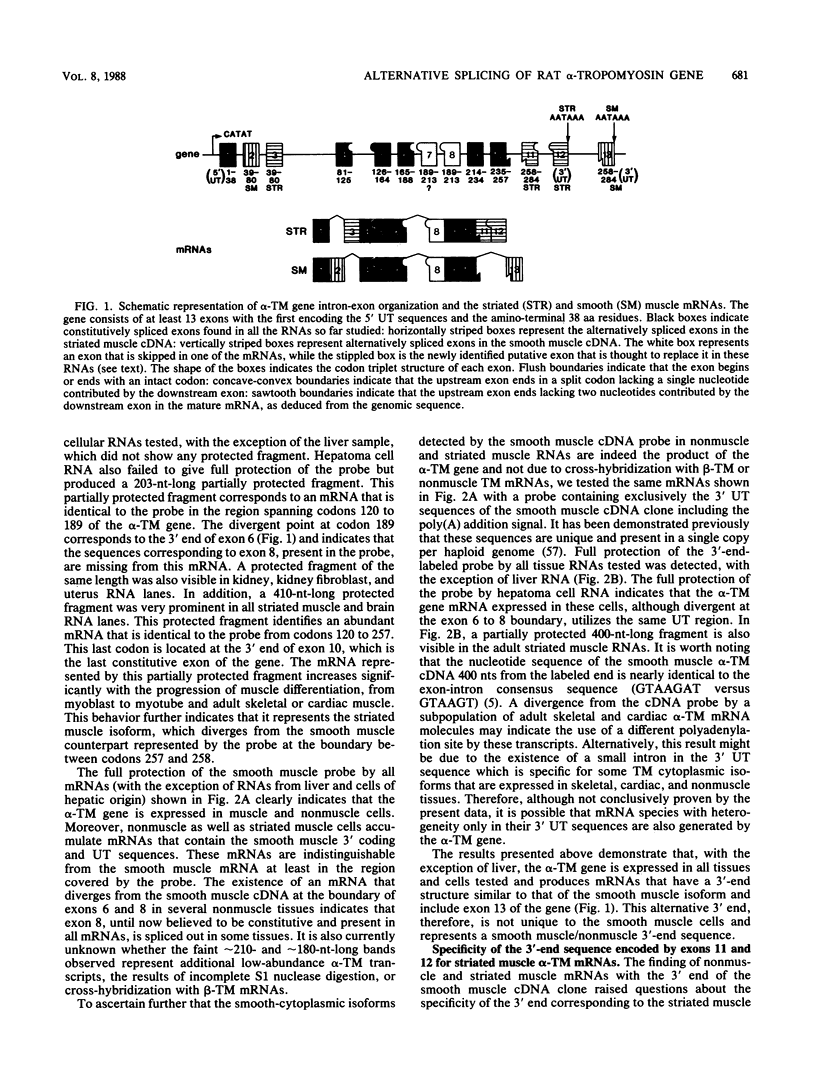

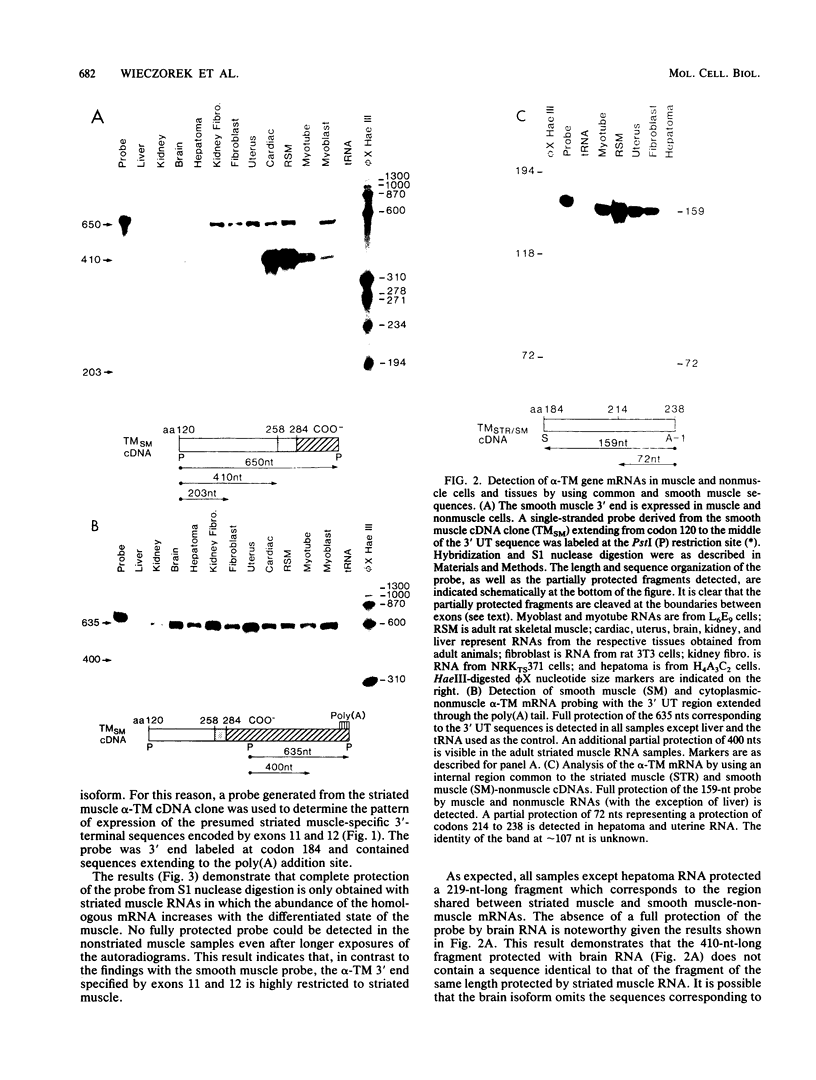

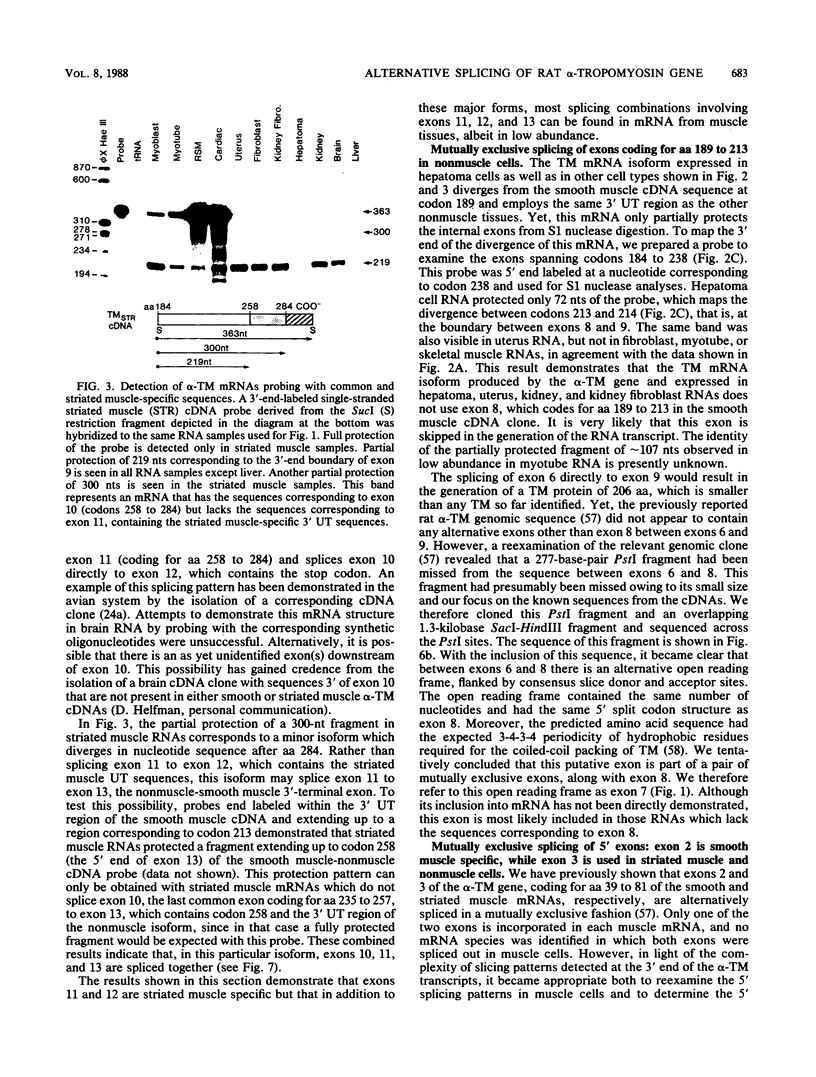

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Andreadis A., Gallego M. E., Nadal-Ginard B. Generation of protein isoform diversity by alternative splicing: mechanistic and biological implications. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1987;3:207–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.03.110187.001231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basi G. S., Boardman M., Storti R. V. Alternative splicing of a Drosophila tropomyosin gene generates muscle tropomyosin isoforms with different carboxy-terminal ends. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Dec;4(12):2828–2836. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.12.2828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berk A. J., Sharp P. A. Sizing and mapping of early adenovirus mRNAs by gel electrophoresis of S1 endonuclease-digested hybrids. Cell. 1977 Nov;12(3):721–732. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90272-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein S. I., Hansen C. J., Becker K. D., Wassenberg D. R., 2nd, Roche E. S., Donady J. J., Emerson C. P., Jr Alternative RNA splicing generates transcripts encoding a thorax-specific isoform of Drosophila melanogaster myosin heavy chain. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Jul;6(7):2511–2519. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.7.2511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breathnach R., Chambon P. Organization and expression of eucaryotic split genes coding for proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1981;50:349–383. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart R. E., Andreadis A., Nadal-Ginard B. Alternative splicing: a ubiquitous mechanism for the generation of multiple protein isoforms from single genes. Annu Rev Biochem. 1987;56:467–495. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.56.070187.002343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart R. E., Nadal-Ginard B. Developmentally induced, muscle-specific trans factors control the differential splicing of alternative and constitutive troponin T exons. Cell. 1987 Jun 19;49(6):793–803. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90617-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breitbart R. E., Nguyen H. T., Medford R. M., Destree A. T., Mahdavi V., Nadal-Ginard B. Intricate combinatorial patterns of exon splicing generate multiple regulated troponin T isoforms from a single gene. Cell. 1985 May;41(1):67–82. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broschat K. O., Burgess D. R. Low Mr tropomyosin isoforms from chicken brain and intestinal epithelium have distinct actin-binding properties. J Biol Chem. 1986 Oct 5;261(28):13350–13359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham M., Alonso S., Bugaisky G., Barton P., Cohen A., Daubas P., Minty A., Robert B., Weydert A. The actin and myosin multigene families. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1985;182:333–344. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-4907-5_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess D. R., Broschat K. O., Hayden J. M. Tropomyosin distinguishes between the two actin-binding sites of villin and affects actin-binding properties of other brush border proteins. J Cell Biol. 1987 Jan;104(1):29–40. doi: 10.1083/jcb.104.1.29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cech T. R., Bass B. L. Biological catalysis by RNA. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:599–629. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.003123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cech T. R. The generality of self-splicing RNA: relationship to nuclear mRNA splicing. Cell. 1986 Jan 31;44(2):207–210. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90751-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu F. K., Maley G. F., Maley F., Belfort M. Intervening sequence in the thymidylate synthase gene of bacteriophage T4. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 May;81(10):3049–3053. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.10.3049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu F. K., Maley G. F., West D. K., Belfort M., Maley F. Characterization of the intron in the phage T4 thymidylate synthase gene and evidence for its self-excision from the primary transcript. Cell. 1986 Apr 25;45(2):157–166. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90379-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins P., Perry S. V. Chemical and immunochemical characteristics of tropomyosins from striated and smooth muscle. Biochem J. 1974 Jul;141(1):43–49. doi: 10.1042/bj1410043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummins P., Perry S. V. The subunits and biological activity of polymorphic forms of tropomyosin. Biochem J. 1973 Aug;133(4):765–777. doi: 10.1042/bj1330765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté G. P., Smillie L. B. Preparation and some properties of equine platelet tropomyosin. J Biol Chem. 1981 Nov 10;256(21):11004–11010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Côté G. P. Structural and functional properties of the non-muscle tropomyosins. Mol Cell Biochem. 1983;57(2):127–146. doi: 10.1007/BF00849190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhoot G. K., Perry S. V. Distribution of polymorphic forms of troponin components and tropomyosin in skeletal muscle. Nature. 1979 Apr 19;278(5706):714–718. doi: 10.1038/278714a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo T., Nadal-Ginard B. Three types of muscle-specific gene expression in fusion-blocked rat skeletal muscle cells: translational control in EGTA-treated cells. Cell. 1987 May 22;49(4):515–526. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90454-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eperon L. P., Estibeiro J. P., Eperon I. C. The role of nucleotide sequences in splice site selection in eukaryotic pre-messenger RNA. Nature. 1986 Nov 20;324(6094):280–282. doi: 10.1038/324280a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaloro J., Treisman R., Kamen R. Transcription maps of polyoma virus-specific RNA: analysis by two-dimensional nuclease S1 gel mapping. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65(1):718–749. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flach J., Lindquester G., Berish S., Hickman K., Devlin R. Analysis of tropomyosin cDNAs isolated from skeletal and smooth muscle mRNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986 Nov 25;14(22):9193–9211. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.22.9193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallauer P. L., Hastings K. E., Baldwin A. S., Pearson-White S., Merrifield P. A., Emerson C. P., Jr Closely related alpha-tropomyosin mRNAs in quail fibroblasts and skeletal muscle cells. J Biol Chem. 1987 Mar 15;262(8):3590–3596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfman D. M., Cheley S., Kuismanen E., Finn L. A., Yamawaki-Kataoka Y. Nonmuscle and muscle tropomyosin isoforms are expressed from a single gene by alternative RNA splicing and polyadenylation. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Nov;6(11):3582–3595. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.11.3582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfman D. M., Feramisco J. R., Ricci W. M., Hughes S. H. Isolation and sequence of a cDNA clone that contains the entire coding region for chicken smooth-muscle alpha-tropomyosin. J Biol Chem. 1984 Nov 25;259(22):14136–14143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaine B. P., Gupta R., Woese C. R. Putative introns in tRNA genes of prokaryotes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Jun;80(11):3309–3312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.11.3309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlik C. C., Fyrberg E. A. Two Drosophila melanogaster tropomyosin genes: structural and functional aspects. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Jun;6(6):1965–1973. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.6.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau S. Y., Sanders C., Smillie L. B. Amino acid sequence of chicken gizzard gamma-tropomyosin. J Biol Chem. 1985 Jun 25;260(12):7257–7263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leavitt J., Latter G., Lutomski L., Goldstein D., Burbeck S. Tropomyosin isoform switching in tumorigenic human fibroblasts. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Jul;6(7):2721–2726. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.7.2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff S. E., Evans R. M., Rosenfeld M. G. Splice commitment dictates neuron-specific alternative RNA processing in calcitonin/CGRP gene expression. Cell. 1987 Feb 13;48(3):517–524. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90202-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff S. E., Rosenfeld M. G., Evans R. M. Complex transcriptional units: diversity in gene expression by alternative RNA processing. Annu Rev Biochem. 1986;55:1091–1117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.55.070186.005303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis W. G., Cote G. P., Mak A. S., Smillie L. B. Amino acid sequence of equine platelet tropomyosin. Correlation with interaction properties. FEBS Lett. 1983 Jun 13;156(2):269–273. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(83)80511-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod A. R., Houlker C., Reinach F. C., Smillie L. B., Talbot K., Modi G., Walsh F. S. A muscle-type tropomyosin in human fibroblasts: evidence for expression by an alternative RNA splicing mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Dec;82(23):7835–7839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.23.7835. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod A. R., Houlker C., Reinach F. C., Talbot K. The mRNA and RNA-copy pseudogenes encoding TM30nm, a human cytoskeletal tropomyosin. Nucleic Acids Res. 1986 Nov 11;14(21):8413–8426. doi: 10.1093/nar/14.21.8413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mak A. S., Smillie L. B., Stewart G. R. A comparison of the amino acid sequences of rabbit skeletal muscle alpha- and beta-tropomyosins. J Biol Chem. 1980 Apr 25;255(8):3647–3655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marston S. B., Smith C. W. The thin filaments of smooth muscles. J Muscle Res Cell Motil. 1985 Dec;6(6):669–708. doi: 10.1007/BF00712237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura F., Yamashiro-Matsumura S., Lin J. J. Isolation and characterization of tropomyosin-containing microfilaments from cultured cells. J Biol Chem. 1983 May 25;258(10):6636–6644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxam A. M., Gilbert W. Sequencing end-labeled DNA with base-specific chemical cleavages. Methods Enzymol. 1980;65(1):499–560. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(80)65059-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan A. D., Stewart M. The 14-fold periodicity in alpha-tropomyosin and the interaction with actin. J Mol Biol. 1976 May 15;103(2):271–298. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90313-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medford R. M., Nguyen H. T., Destree A. T., Summers E., Nadal-Ginard B. A novel mechanism of alternative RNA splicing for the developmentally regulated generation of troponin T isoforms from a single gene. Cell. 1984 Sep;38(2):409–421. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90496-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell P. J., Urlaub G., Chasin L. Spontaneous splicing mutations at the dihydrofolate reductase locus in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Jun;6(6):1926–1935. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.6.1926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nadal-Ginard B. Commitment, fusion and biochemical differentiation of a myogenic cell line in the absence of DNA synthesis. Cell. 1978 Nov;15(3):855–864. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(78)90270-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parry D. A. Analysis of the primary sequence of alpha-tropomyosin from rabbit skeletal muscle. J Mol Biol. 1975 Nov 5;98(3):519–535. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Periasamy M., Strehler E. E., Garfinkel L. I., Gubits R. M., Ruiz-Opazo N., Nadal-Ginard B. Fast skeletal muscle myosin light chains 1 and 3 are produced from a single gene by a combined process of differential RNA transcription and splicing. J Biol Chem. 1984 Nov 10;259(21):13595–13604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson M. L., Perry R. P. Regulated production of mu m and mu s mRNA requires linkage of the poly(A) addition sites and is dependent on the length of the mu s-mu m intron. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 Dec;83(23):8883–8887. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.23.8883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips G. N., Jr Construction of an atomic model for tropomyosin and implications for interactions with actin. J Mol Biol. 1986 Nov 5;192(1):128–131. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90469-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips G. N., Jr, Fillers J. P., Cohen C. Tropomyosin crystal structure and muscle regulation. J Mol Biol. 1986 Nov 5;192(1):111–131. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(86)90468-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed R., Maniatis T. A role for exon sequences and splice-site proximity in splice-site selection. Cell. 1986 Aug 29;46(5):681–690. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinach F. C., MacLeod A. R. Tissue-specific expression of the human tropomyosin gene involved in the generation of the trk oncogene. Nature. 1986 Aug 14;322(6080):648–650. doi: 10.1038/322648a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds G. A., Basu S. K., Osborne T. F., Chin D. J., Gil G., Brown M. S., Goldstein J. L., Luskey K. L. HMG CoA reductase: a negatively regulated gene with unusual promoter and 5' untranslated regions. Cell. 1984 Aug;38(1):275–285. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90549-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Opazo N., Nadal-Ginard B. Alpha-tropomyosin gene organization. Alternative splicing of duplicated isotype-specific exons accounts for the production of smooth and striated muscle isoforms. J Biol Chem. 1987 Apr 5;262(10):4755–4765. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Opazo N., Weinberger J., Nadal-Ginard B. Comparison of alpha-tropomyosin sequences from smooth and striated muscle. Nature. 1985 May 2;315(6014):67–70. doi: 10.1038/315067a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salviati G., Betto R., Danieli Betto D. Polymorphism of myofibrillar proteins of rabbit skeletal-muscle fibres. An electrophoretic study of single fibres. Biochem J. 1982 Nov 1;207(2):261–272. doi: 10.1042/bj2070261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders C., Smillie L. B. Amino acid sequence of chicken gizzard beta-tropomyosin. Comparison of the chicken gizzard, rabbit skeletal, and equine platelet tropomyosins. J Biol Chem. 1985 Jun 25;260(12):7264–7275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanger F., Nicklen S., Coulson A. R. DNA sequencing with chain-terminating inhibitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977 Dec;74(12):5463–5467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.12.5463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schachat F. H., Bronson D. D., McDonald O. B. Heterogeneity of contractile proteins. A continuum of troponin-tropomyosin expression in mammalian skeletal muscle. J Biol Chem. 1985 Jan 25;260(2):1108–1113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodek J., Hodges R. S., Smillie L. B. Amino acid sequence of rabbit skeletal muscle alpha-tropomyosin. The COOH-terminal half (residues 142 to 284). J Biol Chem. 1978 Feb 25;253(4):1129–1136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soeiro R., Birnboim H. C., Darnell J. E. Rapidly labeled HeLa cell nuclear RNA. II. Base composition and cellular localization of a heterogeneous RNA fraction. J Mol Biol. 1966 Aug;19(2):362–372. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(66)80010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Southern E. M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Mol Biol. 1975 Nov 5;98(3):503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone D., Smillie L. B. The amino acid sequence of rabbit skeletal alpha-tropomyosin. The NH2-terminal half and complete sequence. J Biol Chem. 1978 Feb 25;253(4):1137–1148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehler E. E. Multigene families, differential transcription and differential splicing: different origin of contractile isoproteins in muscle. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1985;182:345–355. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-4907-5_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strehler E. E., Periasamy M., Strehler-Page M. A., Nadal-Ginard B. Myosin light-chain 1 and 3 gene has two structurally distinct and differentially regulated promoters evolving at different rates. Mol Cell Biol. 1985 Nov;5(11):3168–3182. doi: 10.1128/mcb.5.11.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P. S. Hybridization of denatured RNA and small DNA fragments transferred to nitrocellulose. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980 Sep;77(9):5201–5205. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.9.5201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker M. D., Edlund T., Boulet A. M., Rutter W. J. Cell-specific expression controlled by the 5'-flanking region of insulin and chymotrypsin genes. Nature. 1983 Dec 8;306(5943):557–561. doi: 10.1038/306557a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieczorek D. F., Periasamy M., Butler-Browne G. S., Whalen R. G., Nadal-Ginard B. Co-expression of multiple myosin heavy chain genes, in addition to a tissue-specific one, in extraocular musculature. J Cell Biol. 1985 Aug;101(2):618–629. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.2.618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamawaki-Kataoka Y., Helfman D. M. Rat embryonic fibroblast tropomyosin 1. cDNA and complete primary amino acid sequence. J Biol Chem. 1985 Nov 25;260(27):14440–14445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]