Abstract

Trabeculation and compaction of the embryonic myocardium are morphogenetic events crucial for the formation and function of the ventricular walls. Fkbp1a (FKBP12) is a ubiquitously expressed cis-trans peptidyl-prolyl isomerase. Fkbp1a-deficient mice develop ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction. To determine the physiological function of Fkbp1a in regulating the intercellular and intracellular signaling pathways involved in ventricular trabeculation and compaction, we generated a series of Fkbp1a conditional knockouts. Surprisingly, cardiomyocyte-restricted ablation of Fkbp1a did not give rise to the ventricular developmental defect, whereas endothelial cell-restricted ablation of Fkbp1a recapitulated the ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction observed in Fkbp1a systemically deficient mice, suggesting an important contribution of Fkbp1a within the developing endocardia in regulating the morphogenesis of ventricular trabeculation and compaction. Further analysis demonstrated that Fkbp1a is a novel negative modulator of activated Notch1. Activated Notch1 (N1ICD) was significantly upregulated in Fkbp1a-ablated endothelial cells in vivo and in vitro. Overexpression of Fkbp1a significantly reduced the stability of N1ICD and direct inhibition of Notch signaling significantly reduced hypertrabeculation in Fkbp1a-deficient mice. Our findings suggest that Fkbp1a-mediated regulation of Notch1 plays an important role in intercellular communication between endocardium and myocardium, which is crucial in controlling the formation of the ventricular walls.

Keywords: FK506 binding protein 12, Ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction, Notch1, Endocardial-myocardial signaling, Mouse

INTRODUCTION

The formation of the ventricular walls is essential to cardiogenesis and is required for normal cardiac function (Moorman and Christoffels, 2003). Ventricular trabeculation and compaction are important morphogenetic events that are controlled by a precise balance between cardiomyocyte proliferation and differentiation during ventricular chamber formation and wall maturation. The trabeculation phase of cardiac development is initiated at the end of cardiac looping (E9.0 to E9.5 in mouse) and is defined as the growth of primitive cardiomyocytes to form the highly organized muscular ridges that are lined by layers of invaginated endocardial cells (Ben-Shachar et al., 1985). The newly formed trabeculae gradually contribute to the formation of the papillary muscles, the interventricular septum and cardiac conductive cells. Concomitant with ventricular septation, the trabeculae start to compact at their base adjacent to the outer myocardium, adding substantially to ventricular wall thickness and coincidently establishing coronary circulation (Wessels and Sedmera, 2003). A significant reduction in trabeculation is closely associated with myocardial growth arrest, whereas persistent trabeculation and/or a reduced level of compaction are associated with left ventricular noncompaction (LVNC) (Towbin, 2010) [also called left ventricular hypertrabeculation (LVHT)] (Finsterer, 2009). LVNC (MIM300183) is a distinct form of inherited cardiomyopathy (Pignatelli et al., 2003; Sandhu et al., 2008). Although some LVNC patients survive into adulthood (Weiford et al., 2004), severe cases accompanied with other cardiac defects (e.g. Ebstein’s anomaly) commonly die at a young age (Koh et al., 2009).

The underlying molecular and cellular mechanisms that orchestrate ventricular trabeculation and compaction, as well as the pathogenesis of LVNC, are poorly understood due to the heterogeneity of the patients and the lack of suitable genetic models (Srivastava and Olson, 2000). Genetic screening of isolated LVNC patients has identified a handful of gene mutations in sarcomere proteins (Klaassen et al., 2008; Xing et al., 2006). However, the genes that are linked to the more severe cases of pediatric LVNC have yet to be identified. Previously, we showed that mutant mice deficient in FK506 binding protein 1a (Fkbp1a, also known as FKBP12) develop multiple abnormal cardiac structures that phenocopy severe cases of LVNC, including a characteristic increase in the number and thickness of ventricular trabeculae (i.e. hypertrabeculation), deep intertrabecular recesses, lack of compaction that leads to a thin left ventricular wall (i.e. noncompaction) and a prominent ventricular septal defect (VSD) (Shou et al., 1998).

Fkbp1a is a ubiquitously expressed 12 kDa peptidyl-prolyl isomerase (Bierer et al., 1990; Schreiber and Crabtree, 1995). It binds to FK506 and rapamycin and inhibits calcineurin and mTOR activity. Fkbp1a is associated with multiple intracellular protein complexes (Ozawa, 2008; Wang and Donahoe, 2004), such as BMP/Activin/TGFβ type I receptors, Ca2+-release channels, and functionally regulates the voltage-gated Na+ channel (Maruyama et al., 2011). Previously, we revealed that Bmp10 is upregulated in Fkbp1a-deficient hearts. Bmp10-deficient mice die by E10.5 and exhibit hypoplastic and thin ventricular walls and impaired ventricular trabeculation (Chen et al., 2004). Transgenic overexpression of Bmp10 in embryonic heart led to ventricular hypertrabeculation (Pashmforoush et al., 2004). The elevated level of Bmp10 observed in both Fkbp1a and Nkx2-5 knockout hearts correlates strongly with the ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction phenotypes displayed in these mutants (Chen et al., 2009). However, the underlying mechanism by which Fkbp1a regulates Bmp10 expression and ventricular wall formation remains elusive.

Recently, it has been shown that endocardial Notch1 provides key spatial-temporal control of myocardial growth via regulation of Bmp10 and neuregulin 1 (Nrg1) (Grego-Bessa et al., 2007). Endocardium is primarily made up of endothelial cells. Activated Notch1 intracellular domain (N1ICD) was found to be more abundant in endocardial cells near the proximal end of the trabecular myocardium, where trabeculation initiates, and was significantly less abundant in the endocardial cells at the distal end of the trabeculae (Grego-Bessa et al., 2007). Ablation of Notch1 or its transcriptional co-factor Rbpjk within endothelial cells results in hypotrabeculation and, subsequently, early embryonic lethality (Del Monte et al., 2007; Grego-Bessa et al., 2007). Interestingly, both endocardially expressed Nrg1 and myocardially expressed Bmp10 were downregulated in endothelial-restricted Notch1 knockout hearts (Grego-Bessa et al., 2007). Collectively, these findings suggested a crucial role for endocardial Notch1 in regulating ventricular trabeculation.

To determine the cellular and molecular mechanism of Fkbp1a in regulating ventricular trabeculation and compaction, and its pathogenetic role in LVNC, we generated Fkbp1a conditional knockouts using the Cre-loxP recombination system. Ablating Fkbp1a in cardiac progenitor cells via the use of Nkx2.5cre mice (Moses et al., 2001), we were able to generate Fkbp1aflox/-:Nkx2.5cre mice that recapitulate the ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction with full penetrance observed in systemic Fkbp1a null mice. By contrast, ablation of Fkbp1a using cardiomyocyte-specific Cre lines did not give rise to abnormal ventricular wall formation. Surprisingly, endothelial-restricted ablation of Fkbp1a phenocopied the ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction observed in Fkbp1a systemically deficient mice, suggesting that endocardium plays an important role in regulating ventricular trabeculation and compaction. Biochemical and molecular analyses demonstrated that Fkbp1a regulates Notch1-mediated signaling within developing endocardial cells. An excess of activated Notch1 is found in Fkbp1a-ablated endothelial cells and is the likely cause of the observed Fkbp1a mutant phenotypes. Treatment of Fkbp1a-deficient mice with Notch inhibitors reduces the hypertrabeculation phenotype. Taken together, we have revealed a mechanism whereby Fkbp1a modulates a critical level of Notch1 activity that is required for regulating ventricular chamber and wall formation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of Fkbp1a floxed and conditional knockout mice

The generation of Fkbp1a floxed mice (Fkbp1aflox) has been described previously (Maruyama et al., 2011). To achieve cell lineage-restricted deletion of Fkbp1a in the developing heart, Fkbp1aflox mice were crossed to various cell type-specific Cre mouse lines. To ensure efficient Cre-loxP recombination in these conditional genetic ablations, we first created Fkbp1a+/-/Cre+ mice followed by an additional intercross onto Fkbp1aflox/flox mice. For the most part, we used Fkbp1aflox/-/Cre+ as an experimental group and Fkbp1aflox/+/Cre+ and Fkbp1aflox/-/Cre- as the control group. Animal protocols were approved by the Indiana University School of Medicine Institutional Animal Care and Research Advisory Committee.

Histological, morphological, whole-mount and section in situ hybridization, and immunohistochemical analyses

Embryos were harvested by cesarean section. Embryos and isolated embryonic hearts at specific stages were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS. The fixed embryos were paraffin embedded, sectioned (7 μm), and stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin. Whole-mount and section in situ hybridization were performed as previously described (Franco et al., 2001). In brief, complementary RNA probes for various cardiac markers were labeled with digoxigenin (DIG)-UTP using the Roche DIG RNA Labeling System according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. Immunohistochemical staining was performed using the staining system from Vector Laboratories according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The primary antibodies used in the immunohistochemical analyses were: anti-Fkbp1a (FKBP12) antibody (Thermo Scientific, PA1-026A), MF-20 anti-myosin heavy chain monoclonal antibody [Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB), University of Iowa], anti-Ki67 antibody (ab15580; Abcam), anti-CD31 (Pecam1) antibody (BD Biosciences, 553370) and anti-cleaved Notch1 (N1ICD) antibody (Cell Signaling, 2421s).

Whole-mount immunofluorescence staining and confocal microscopy imaging

Staining and microscopy procedures were as previously described (Chen et al., 2004). Embryos were harvested and washed three times in ice-cold PBS and fixed for 10 minutes in pre-chilled acetone before being treated with blocking solution containing 3% non-fat dried milk (Bio-Rad) and 0.025% Triton X-100 for 1 hour. Directly conjugated primary antibodies were then added to a final concentration of 1 μg/ml for 12-18 hours at 4°C. The anti-CD31 antibody (BD Biosciences) and the MF-20 monoclonal antibody (DSHB) were labeled with Alexa Fluor 488 and the anti-Fkbp1a antibody (Thermo Scientific) was labeled with Alexa Fluor 647 using a monoclonal antibody labeling kit (Molecular Probes). Samples were analyzed using a Bio-Rad MRC 1024 laser scanning confocal microscope equipped with a krypton-argon laser (488, 647 nm). z-series were obtained by imaging serial confocal planes at 512×512 pixel resolution with a Nikon 20× oil-immersion objective (2 μm intervals).

Echocardiography

Mice were gently anesthetized with 1.5% isoflurane. Two-dimensional short-axis images were obtained with a high-resolution micro-ultrasound system (Vevo 770, VisualSonics) equipped with a 40 MHz mechanical scan probe. Fractional shortening (FS), ejection fraction, left ventricular internal diameter (LVID) during systole, LVID during diastole, end-systolic volume, and end-diastolic volume were calculated with Vevo Analysis software (version 2.2.3) as described previously (Zhu et al., 2009). LVID during systole and diastole were measured from M-mode recording at the level of the mid-papillary muscle, whereas end-systolic and end-diastolic volumes were measured with B-mode recording in a plane containing the aortic and mitral valves.

Cell transfection and protein stability assay

Flag-tagged human FKBP1A cDNA was subcloned into the BamHI and EcoRI sites of the pCDNA3 vector (Invitrogen). N1ICD expression plasmid (N1ICD-PCS2) is a generous gift from Dr Raphael Kopan (Washington University). Western blots employed anti-Flag (Sigma, F1804), anti-N1ICD (Cell Signaling) and anti-tubulin (Sigma, T6199) antibodies. For the protein stability assay, the N1ICD-expressing plasmid was transfected into control HEK293 cells and those stably expressing human FKBP1A tagged with Flag epitope (FKBP1A-HEK293) using FuGENE HD (Roche) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cycloheximide (50 μg/ml, Sigma) was added to the medium for the indicated length of time. To inhibit proteasomes, transfected cells were treated with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (10 μmol, EMD Chemicals) for various time periods. For detection of ubiquitylated N1ICD, histidine-tagged ubiquitin (His-ubiquitin) pCDNA3 plasmid was co-transfected with N1ICD expression plasmid into HEK293 or FKBP1A-HEK293 cells. After 30 hours, transfected cells were incubated with MG-132 (10 μmol) for 8 hours before being lysed in Ni-agarose lysis buffer [50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 0.05% Tween 20, 100 μg/ml N-ethylmaleimide, and Complete Protease Inhibitor (Roche)]. His-ubiquitin-conjugated proteins were enriched using Ni-NTA-agarose (Qiagen) from cells co-transfected with N1ICD and His-ubiquitin. The beads were washed ten times with Ni-agarose wash buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole, 0.05% Tween 20). In order to reduce nonspecific binding to beads as much as possible, nickel-binding proteins were resuspended in 2× sample buffer supplemented with 200 mM imidazole and heated for 10 minutes at 95°C before western blot with anti-N1ICD antibody.

Luciferase assay

Hes1-pGL3 luciferase plasmid and full-length Notch1 and Dll4 expression plasmids have been described previously (McGill and McGlade, 2003). Fkbp1a knockout and control mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and endothelial cells were isolated as described (Weaver et al., 1997). For the luciferase assay, Hes1-pGL3 reporter plasmid was transfected into Fkbp1a knockout or control MEFs and endothelial cells alone or with different combinations of Notch1, Dll4 and Fkbp1a expression plasmids. Renilla luciferase plasmid was co-transfected as an internal control. Transfection efficiency was determined by co-transfection of pCDNA3-EGFP. Luciferase activity was analyzed 36 hours after transfection with the Dual-Luciferase Assay System (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Isolation and culture of endothelial cells

Murine endothelial cells were isolated from lung tissues of Fkbp1aflox/flox neonates (day 10). The harvested lung tissue was minced to small pieces and then digested with 0.25% collagenase A (Stem Cell Technologies) for 40 minutes followed by cell dissociation buffer (Life Technologies) in order to produce a single-cell suspension. The cell suspension was filtered through a 70-μm strainer and stained with anti-CD31, anti-CD45 (Ptprc) and anti-Mac1 (Itgam) antibodies (all eBiosciences). The CD45- Mac1- CD31+ endothelial cells were sorted on a FACS Aria (Becton Dickinson). The sorted endothelial cells were cultured in EGM2 (endothelial growth medium 2, Lonza) with 10% FBS, and 7 days after initiating culture the adherent cells were infected with recombinant retrovirus expressing human telomerase to maintain proliferation potential (Hahn et al., 1999). After 2 weeks of further culture, the endothelial cells were reselected and enriched for CD45- Mac1- CD31+ cells by FACS sorting. The resulting endothelial cells were analyzed by FACS and confirmed by immunofluorescence staining for endothelial cell surface markers including CD31 (eBiosciences), Vcam1 (Santa Cruz) and Flk1 (Kdr) (eBiosciences) (see supplementary material Fig. S3A,B). To further validate the endothelial characteristics of the cells, we used an in vitro MatriGel tube-forming assay (see supplementary material Fig. S3C). As previously described, we plated Fkbp1aflox/flox cells on a thin layer of MatriGel (Stem Cell Technologies) at 1×104 cells/well of a 96-well plate in ECM2 containing 10% FCS and allowed a tubular structure to form. Typical tube formation after 20 hours in culture (supplementary material Fig. S3) suggested that the isolated Fkbp1aflox/flox cells maintained endothelial cell characteristics. To generate Fkbp1a-deficient endothelial cells, Fkbp1aflox/flox endothelial cells were infected with recombinant adenovirus expressing Cre/eGFP (Zhang et al., 2004), in which the eGFP signal was used to evaluate transduction efficiency. Western blot and qRT-PCR analyses were used to confirm the expression levels of Fkbp1a in these cells. For plasmid transfection of endothelial cells, X-tremeGENE HP DNA transfection reagents (Roche Diagnostics) were used according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

To test Notch1 protein stability in endothelial cells, N1ICD-PCS2 was co-transfected into Fkbp1aflox/flox endothelial cells with empty pCDNA3 plasmid at a 10 to 1 ratio using FuGENE HD (Roche Applied Bioscience) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cells stably expressing N1ICD were selected by neomycin resistance with G418 (Invitrogen, 400 ng/ml in culture medium). N1ICD-expressing Fkbp1a-deficient endothelial cells were generated by infection with recombinant adenovirus expressing Cre/eGFP (1×108 pfu). Cycloheximide (25 μg/ml) was added to the medium for the indicated length of time followed by western blot analysis.

γ-Secretase inhibitor injection

The γ-secretase inhibitor DBZ {(S,S)-2-[2-(3,5-difluorophenyl)acetylamino]-N-(5-methyl-6-oxo-6,7-dihydro-5H-dibenzo[b,d]azepin-7-yl)propionamide} (EMD Chemicals, 565789) was given by intraperitoneal injection at 11.5 days of pregnancy (10 μmol/kg) (Milano et al., 2004). Control mice were administered with vehicle (0.5% hydroxypropylmethylcellulose in 0.1% Tween 80). Embryos were harvested at E13.5 and subjected to morphological, histological and in situ hybridization analyses as described above.

Statistical analysis

All values are presented as mean ± s.e.m. Differences between groups were compared by Student’s t-test. P<0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

Cardiac progenitor ablation of Fkbp1a

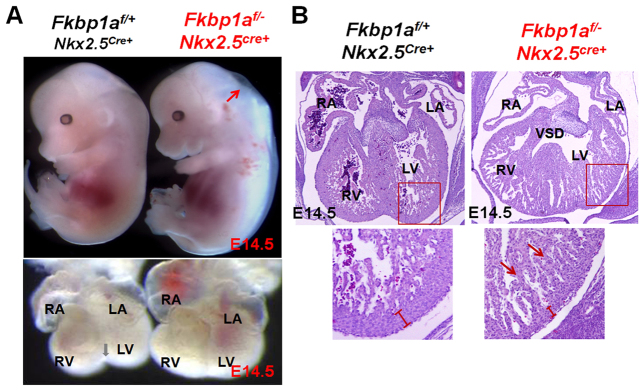

To determine whether the ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction present in Fkbp1a-deficient mice is a primary cardiac defect, we used Nkx2.5cre to ablate the Fkbp1a gene. Nkx2.5cre delivers Cre within cardiac progenitor cells in the cardiac crescent, which give rise to cardiomyocytes, endocardial cells and to a subpopulation of cells from the septum transversum that gives rise to the epicardium, and within cardiac neural crest cells (Moses et al., 2001; Zhou et al., 2008). Fkbp1aflox/-:Nkx2.5cre mice demonstrated fetal lethality, dying in utero between E14.5 and birth. The mutants phenocopied Fkbp1a-deficient mice, with profound hypertrabeculation, noncompaction and VSDs with 100% penetrance (Fig. 1; Table 1) (Shou et al., 1998), indicating that the ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction within Fkbp1a systemic knockouts are primarily derived from defects in the cardiogenic program, and are not secondary to defects in another organ system.

Fig. 1.

Genetic ablation of Fkbp1a using Nkx2.5cre. (A) Comparison of gross morphology of Fkbp1aflox/-:Nkx2.5cre and control mouse embryos (top) and hearts (bottom) at E14.5. Fkbp1aflox/-:Nkx2.5cre embryos appear edematous (red arrow) and die in utero. Gray arrow indicates formation of the ventricular groove in the control heart. (B) Histological analysis of Fkbp1aflox/-:Nkx2.5cre and control hearts at E14.5. Arrows indicate the overgrowth of the trabecular myocardium in Fkbp1a mutant hearts. The width of the ventricular compact wall is indicated. The boxed regions are enlarged beneath. RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

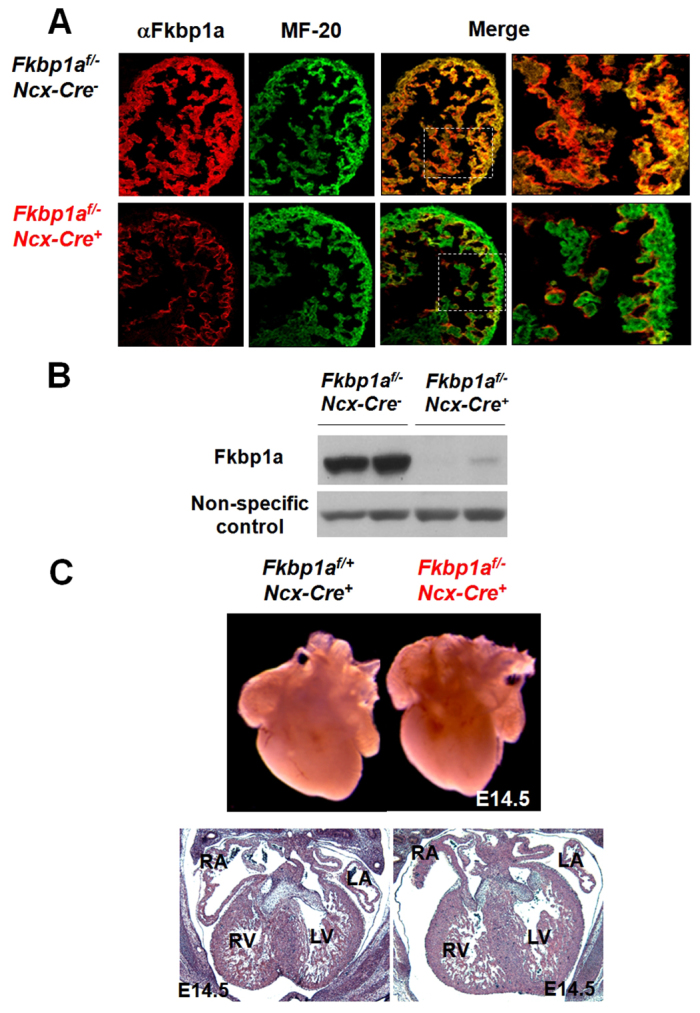

Table 1.

Phenotypes of cell lineage-restricted Fkbp1a mutants

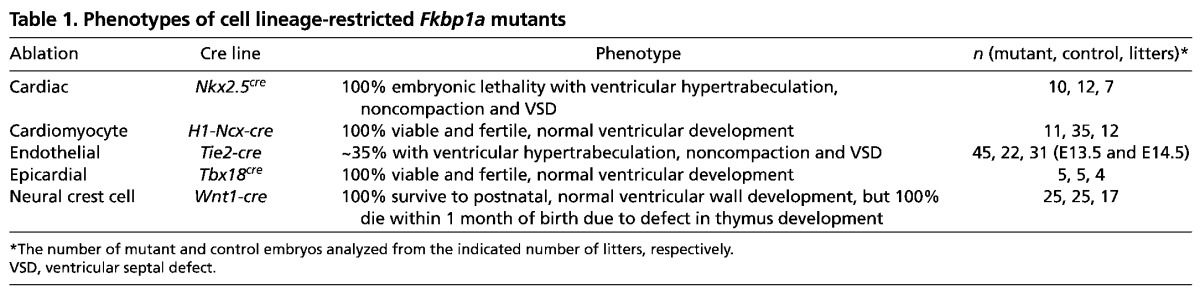

Specific ablation of Fkbp1a within myocardial, epicardial and neural crest cell-restricted cell populations

To further determine the cell-autonomous contribution to the ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction caused by Fkbp1a ablation, we crossbred Fkbp1aflox mice onto the cardiomyocyte-specific sodium-calcium exchanger promoter H1-cre (H1-Ncx-cre) (Müller et al., 2002). The Cre activity in H1-Ncx-cre is observed in developing myocardium as early as E9.5 and in a cardiomyocyte-restricted manner throughout embryonic, fetal and adult life (supplementary material Fig. S1). To our surprise, Fkbp1aflox/-:H1-Ncx-cre mice demonstrated normal ventricular chamber formation and survived to adulthood. Histologically, no hypertrabeculation or noncompaction was found in Fkbp1aflox/-:H1-Ncx-cre hearts (Fig. 2; Table 1). Western blot, qRT-PCR and immunofluorescence analyses confirmed efficient ablation of Fkbp1a within the embryonic myocardium (Fig. 2). This finding suggests that cardiomyocytes are not the primary cell type contributing to the ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction observed in mice with systemic Fkbp1a ablation.

Fig. 2.

Cardiomyocyte-restricted ablation of Fkbp1a using H1-Ncx-cre transgenic mice. (A) Dual immunofluorescence analyses confirm the genetic ablation of Fkbp1a in developing myocardium at E12.5. Representative confocal images of heart sections co-stained with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-Fkbp1a antibody (red) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-myosin heavy chain antibody (MF-20; green). There is a significant reduction in Fkbp1a in Fkbp1aflox/-:H1-Ncx-cre myocardium. The boxed regions of the merge are enlarged to the right. (B) Western blot confirms the efficient removal of Fkbp1a in Fkbp1aflox/-:H1-Ncx-cre heart. (C) Morphological and histological analysis of Fkbp1aflox/-:H1-Ncx-cre and control hearts at E14.5. RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle.

To validate this observation, we crossbred Fkbp1flox mice to other cardiomyocyte-specific Cre transgenic lines, including cTnt-cre (Table 1) (Jiao et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2000). Consistently, all of these mutant mice exhibited normal ventricular chamber formation. cTnt-cre delivers Cre within the developing myocardium as early as E7.5 (Jiao et al., 2003), which is similar to that reported for Nxk2.5cre. Despite this early Cre activity, Fkbp1aflox/-:cTnt-cre mice display normal ventricular trabeculation and compaction (supplementary material Fig. S2), further indicating that the abnormal ventricular development in Fkbp1a-deficient mice is not a direct function of Fkbp1a within cardiomyocytes. Similarly, cardiac development was reported to be normal in studies using MHC-cre and Mck-cre to delete Fkbp1a (Maruyama et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2004). Together, these data rule out cardiomyocytes as the primary contributing cell lineage to ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction in Fkbp1a-deficient mice, and instead imply another cell lineage or lineages as the primary cause.

Epicardium has been implicated to play an important role in supporting ventricular wall growth and, potentially, compaction (Sucov et al., 2009). To test whether epicardial Fkbp1a contributes to hypertrabeculation or noncompaction, we ablated Fkbp1a from epicardial cells using Tbx18cre mice (Cai et al., 2008). Tbx18cre mice deliver Cre activity largely to epicardium, with a low activity in cardiomyocytes refined in ventricular septum (Cai et al., 2008; Christoffels et al., 2009). We found that Fkbp1aflox/-:Tbx18cre mutants had normal ventricular wall formation (Table 1; supplementary material Fig. S2). Previously we showed that, despite low penetrance, Fkbp1a-deficient mice develop exencephaly (Shou et al., 1998), indicating potential involvement of cranial-facial neural crest cells. We used Wnt1-cre to ablate Fkbp1a from neural crest cell lineages (Jiang et al., 2000). Once again, we observed normal ventricular wall formation in Fkbp1aflox/-:Wnt1-cre mutants (Table 1; supplementary material Fig. S2). When considering the cell lineages marked by Nkx2.5cre, the endocardium remained untested. Therefore, we next sought to specifically ablate Fkbp1a from the endocardium.

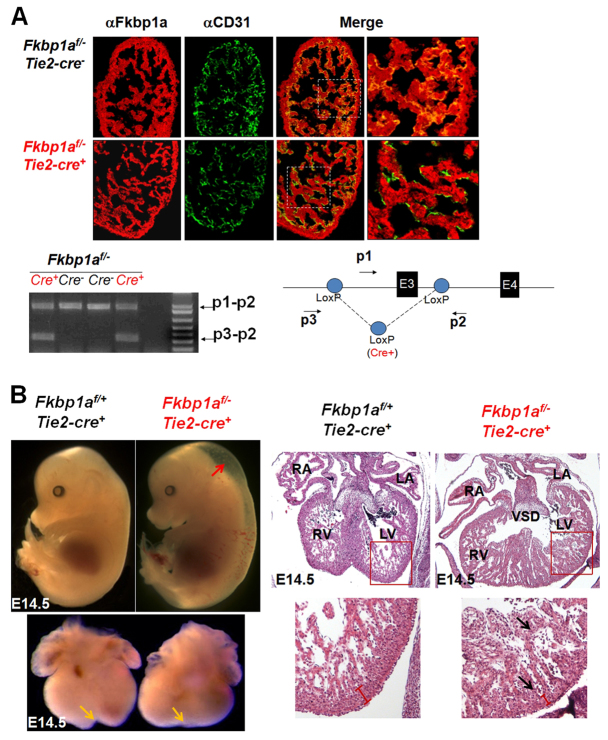

Endothelial-specific ablation of Fkbp1a

The developing endocardium has an important role in regulating ventricular wall formation (Brutsaert, 2003). To test the contribution of endocardium to the hypertrabeculation and noncompaction phenotypes observed with systemic Fkbp1a ablation, we studied the endothelial-specific deletion of Fkbp1a using Tie2-cre (Tie2 is also known as Tek) transgenic mice (Constien et al., 2001; Gitler et al., 2004; Kisanuki et al., 2001). Tie2-cre mice deliver Cre activity to endothelial cells, including endocardial cells, as early as E9.0 (Kisanuki et al., 2001). Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre mice phenocopied the ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction seen in Fkbp1a-deficient hearts (Fig. 3; Table 1). Approximately 35% (15/45) of E13.5-14.5 Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre embryos were edematous and appeared to have failing hearts as evidenced by the absence of effective perfusion. Hearts isolated from these E13.5-14.5 Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre embryos were enlarged and typically ‘pumpkin-shaped’, lacking the normal ventricular groove, a strong indication of abnormal ventricle chamber development (Fig. 3). Histological analysis of these hearts confirmed multiple abnormal cardiac ventricular structures similar to those of Fkbp1a-/- hearts, including various degrees of hypertrabeculation, noncompaction and a thin compact wall. Prominent VSDs, including both membranous and muscular, were also observed in six of these 15 mutant hearts.

Fig. 3.

Endothelial-restricted ablation of Fkbp1a using Tie2-cre transgenic mice. (A) Dual immunofluorescence and PCR analyses to confirm the genetic ablation of Fkbp1a in developing endocardial/endothelial cells at E12.5. Representative confocal images of heart sections are co-stained with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated anti-Fkbp1a antibody (red) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-CD31 antibody (green). There is a significant reduction of Fkbp1a in the CD31-positive endothelial cells in Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre hearts. Beneath is shown a diagnostic genomic PCR analysis of DNA samples isolated from E13.5 heart alongside a schematic of the Fkbp1aflox allele showing the location of diagnostic primers p1, p2 and p3; E, exon. A specific p3-p2 band represents the allele after Cre-loxP-mediated recombination. (B) Morphological and histological analysis of Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre and control embryos and hearts at E14.5. Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre embryos are edematous (red arrow). The mutant hearts lack a normal ventricular groove (yellow arrows) and demonstrate hypertrabeculation and noncompaction (black arrows). RA, right atrium; LA, left atrium; RV, right ventricle; LV, left ventricle; VSD, ventricular septal defect.

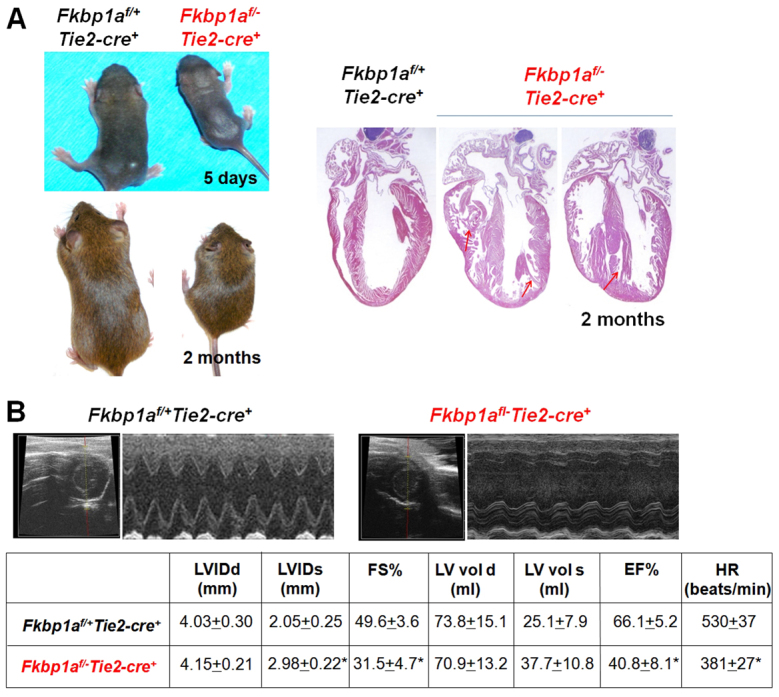

Although the majority of Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre mice (compared with just ∼5% of Fkbp1a-/- mice) survived in utero, most of these survivors died within 8 weeks of birth, probably owing to compromised cardiac function (see below) and defects in T cell function (data not shown); the surviving Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre mice exhibited milder hypertrabeculation and noncompaction phenotypes (Fig. 4). Echocardiographic analysis demonstrated severely compromised cardiac function in these mutants, consistent with the histological findings (Fig. 4). Collectively, our observations indicate that abnormal endocardial function is likely to be the primary cause of the hypertrabeculation and noncompaction phenotypes in Fkbp1a-deficient mutants.

Fig. 4.

Histological and functional analyses of adult Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre mice. (A) (Left) Restricted growth of surviving Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre mice. (Right) Abnormal ventricular wall structure in Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre hearts, with hypertrabeculation and noncompaction. Arrows indicate abnormal trabecular myocardia and ventricular septum. (B) M-mode echocardiographic analysis of 2-month-old adult males. One-second traces are shown. Both fractional shortening and ejection fraction are severely compromised in Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre mutants. Values indicate mean ± s.e.m.; n=12; *P<0.05. LVIDd, left ventricular internal diameter diastolic; LVIDs, left ventricular internal diameter systolic; FS%, fractional shortening; LV vol d, left ventricular volume diastolic; LV vol s, left ventricular volume systolic; EF%, ejection fraction; HR, heart rate.

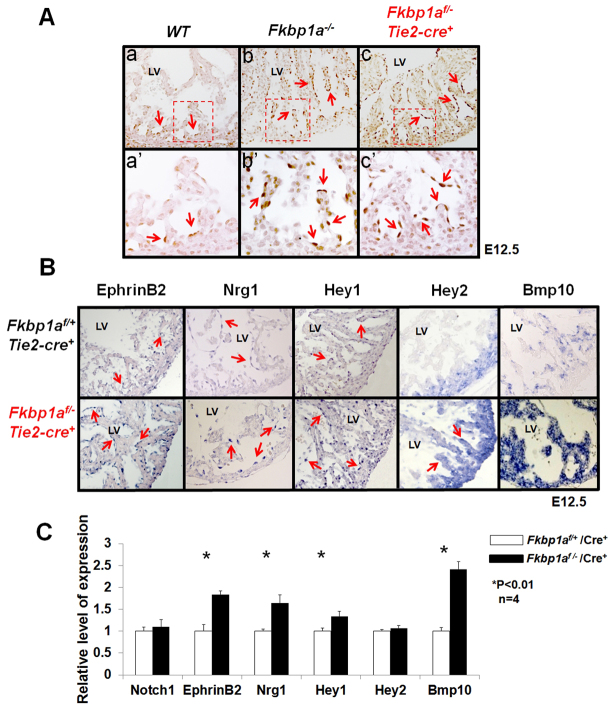

Notch1 and downstream endocardial signaling are altered in Fkbp1a mutant hearts

Recent studies have demonstrated that perturbation of Notch1 signaling within the endocardium impairs cardiomyocyte Bmp10 expression, ventricular trabeculation and wall formation (Grego-Bessa et al., 2007). To define whether Notch1 activation within the endocardium is altered in Fkbp1a mutants, we compared the pattern of activated N1ICD in the developing ventricular endocardial cells of Fkbp1a-deficient, Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre and wild-type control hearts. Using immunohistochemistry, we were able to confirm that nuclear N1ICD was robustly distributed within the endocardial cells close to the proximal end of the trabecular myocardium of control hearts (Fig. 5A). By contrast, this characteristic pattern of N1ICD was clearly altered in Fkbp1a mutant hearts, as N1ICD was found in endocardial cells throughout and alongside the trabecular myocardium (Fig. 5A), suggesting that Notch1 is activated ectopically within Fkbp1a-deficient and Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre endocardium.

Fig. 5.

Assessment of Notch1-mediated signaling in the developing endocardium of Fkbp1a-deficient and Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre mouse hearts. (A) Immunohistological analysis using antibody specific to activated Notch1 (N1ICD). In control heart (WT), nuclear N1ICD is mainly located in endothelial cells at the proximal end of trabeculae (arrows in a′). By contrast, N1ICD was found throughout endothelial cells in both Fkbp1a-deficient and Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre mutant hearts (arrows in b′ and c′). The boxed regions in a-c are magnified in a′-c′. (B) In situ hybridization of downstream targets of Notch1 in Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre and control hearts at E12.5. Ephrin B2 (Efnb2), neuregulin 1 (Nrg1) and Hey1 are upregulated in endocardial cells in Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre hearts. Bmp10 is upregulated in both trabecular and compact myocardium. Interestingly, Hey2 expression is upregulated in trabecular myocardium compared with controls. Arrows indicate positive signals. (C) qRT-PCR confirms the expression levels of Notch1, Efnb2, Nrg1, Hey1, Hey2 and Bmp10 in Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre hearts at E13.5. Interestingly, despite the altered expression pattern, the overall expression level of Hey2 is not altered. Error bars indicate s.e.m. LV, left ventricle.

Furthermore, Hey1 and ephrin B2 (Efnb2), two well-known direct downstream targets of Notch1 that are expressed within endocardium (Grego-Bessa et al., 2007; Hainaud et al., 2006), were found significantly upregulated in the Fkbp1a-deficient endocardial cells, supporting the observation that there is increased Notch1 activity in Fkbp1a mutant endocardium (Fig. 5B,C). Interestingly, although the overall level of Hey2 expression did not appear to differ significantly in Fkbp1a mutant versus control heart (Fig. 5C), its expression pattern was significantly altered (Fig. 5B). In normal myocardium, Hey2 transcript is restricted to compact myocardium. We found that Hey2 expression is expanded into the trabecular myocardium in Fkbp1a mutant heart (Fig. 5B). Endocardial Nrg1 expression is downstream of Efnb2 and is downregulated in Notch1 mutant endocardium (Grego-Bessa et al., 2007). Both in situ hybridization and qRT-PCR analyses confirmed that Nrg1 was upregulated in Fkbp1aflox/-:Tie2-cre heart, as was Bmp10 (Fig. 5B,C). Taken together, our data demonstrate that Fkbp1a is an important regulator for endocardial Notch1-mediated signaling during ventricular wall formation.

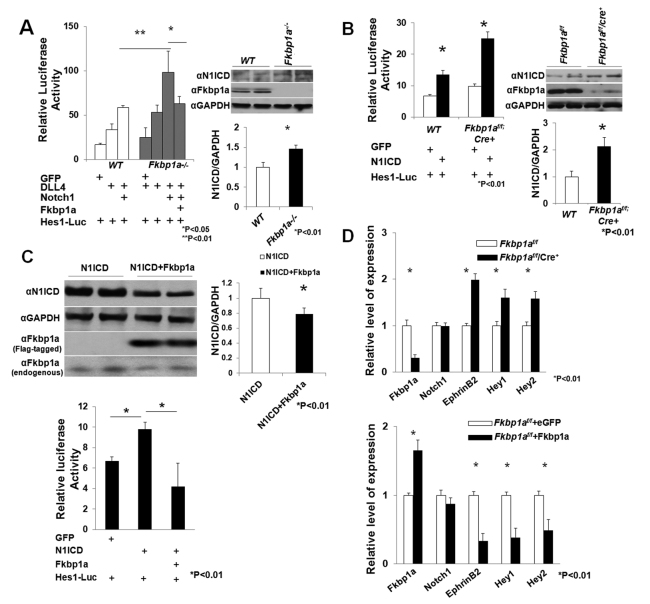

Fkbp1a regulates N1ICD stability and turnover

To further define the role of Fkbp1a in Notch1 activation, we isolated mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from Fkbp1a-deficient and control embryos (E12.5) and analyzed Notch activity. Notch-dependent Hes1-luciferase reporter plasmid was transfected into Fkbp1a-deficient and wild-type control MEFs in combination with Notch1 and delta-like 4 (Dll4) expression plasmids. The level of luciferase activity reflects the level of activated Notch1 (McGill and McGlade, 2003). From four independent sets of experiments, we found that luciferase activities were significantly enhanced in both Dll4-transfected and Dll4/Notch1 co-transfected Fkbp1a-deficient MEFs when compared with transfected wild-type MEFs (Fig. 6A). Re-introduction of Fkbp1a into the Fkbp1a-deficient cells reduced luciferase activity to a level comparable to that in wild-type cells. Consistent with these findings, western blot analysis demonstrated that the endogenous N1ICD level is significantly higher in Fkbp1a-deficient than in wild-type MEFs (Fig. 6A). To validate this finding in endothelial cells, we prepared endothelial cells from Fkbp1aflox/flox neonatal mice (supplementary material Fig. S3). Fkbp1a-deficient endothelial cells were generated by transducing the cells with Ad-Cre/eGFP. Western blot confirmed the efficient ablation of Fkbp1a in Cre-transduced Fkbp1aflox/flox mouse endothelial cells (Fkbp1aflox/flox/Cre) (Fig. 6B). Hes1-luciferase reporter assays were performed in Fkbp1aflox/flox and Fkbp1aflox/flox/Cre cells (Fig. 6B). Similar to the finding in MEFs, Notch-dependent luciferase activities were significantly higher in Fkbp1aflox/flox/Cre than in Fkbp1aflox/flox endothelial cells (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6.

Biochemical analyses of altered Notch1 activity in Fkbp1a mutant cells. (A) (Left) Luciferase assay to determine Notch1 activity in Fkbp1a-deficient and control mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) in which Hes1-luciferase reporter was transfected together with Notch1, Dll4, Fkbp1a and eGFP as indicated. Fkbp1a-deficient cells maintain significantly higher luciferase activity, which is reduced by Fkbp1a re-introduction. (Right) Western blot analysis of endogenous N1ICD levels in Fkbp1a-deficient and wild-type MEFs. (B) (Left) Luciferase assay to determine Notch1 activity in Fkbp1a-deficient and control mouse endothelial cells. (Right) Western blot shows that the N1ICD protein level is significantly higher in Fkbp1a-deficient cells. (C) (Top) Western blot showing that the N1ICD protein level is downregulated in mouse endothelial cells overexpressing human FKBP1A. (Bottom) Luciferase assay to determine Notch1 activity in FKBP1A-overexpressing and control endothelial cells. (D) qRT-PCR analysis shows that Notch1 mRNA levels are not altered in Fkbp1a-deficient or FKBP1A-overexpressing endothelial cells. However, Efnb2, Hey1 and Hey2 expression levels are altered. Error bars indicate s.e.m.

We transfected activated Notch1 (N1ICD-PCS2) into Fkbp1aflox/flox endothelial cells in conjunction with pCDNA3-FKBP1A (human) or control pCDNA3-eGFP vector. The N1ICD protein level in Fkbp1aflox/flox FKBP1A-overexpressing endothelial cells was significantly lower than in Fkbp1aflox/flox eGFP-expressing cells (Fig. 6C, top). As expected, overexpression of FKBP1A reduced Notch-dependent Hes1-luciferase activity (Fig. 6C, bottom).

To determine whether Fkbp1a could affect endogenous Notch1 expression in endothelial cells, we compared Notch1 mRNA levels in Fkbp1a-deficient and human FKBP1A-overexpressing endothelial cells (Fig. 6D). Notch1 mRNA levels were not altered in Fkbp1a-deficient or FKBP1A-overexpressing endothelial cells. However, the mRNA levels of the Notch1 downstream targets Efnb2, Hey1 and Hey2 were upregulated in Fkbp1a-deficient and downregulated in FKBP1A-overexpressing endothelial cells, consistent with the notion that Notch1 activities are impacted directly by the intracellular levels of Fkbp1a.

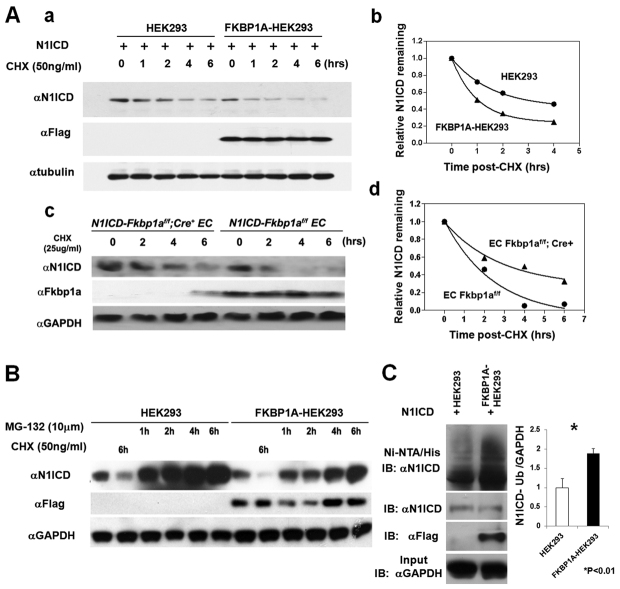

Previously, we established HEK293 cell lines with overexpression of Flag-tagged human FKBP1A (FKBP1A-HEK293). When we attempted to overexpress N1ICD in HEK293 and FKBP1A-HEK293 cells, we found that the N1ICD protein level was significantly reduced in FKBP1A-HEK293 cells when compared with control HEK293 cells (supplementary material Fig. S4). Given that Notch activity is closely associated with ubiquitylation-mediated degradation, this finding, along with the observation that there is no change in Notch1 mRNA levels and that N1ICD protein is significantly higher in Fkbp1a-deficient cells, suggested that, mechanistically, Fkbp1a regulates Notch1 activity by modulating N1ICD stability. To test this hypothesis, we compared the N1ICD protein degradation rate in human FKBP1A-overexpressing (i.e. FKBP1A-HEK293) and control HEK293 cells. The rate of N1ICD degradation was significantly greater in FKBP1A-HEK293 cells (Fig. 7Aa,b). To validate this finding in endothelial cells, we generated stable N1ICD-overexpressing Fkbp1aflox/flox cells (N1ICD-Fkbp1aflox/flox) and compared their N1ICD degradation rate with that of N1ICD-Fkbp1aflox/flox/Cre cells. N1ICD-Fkbp1aflox/flox/Cre cells had a significantly slower degradation rate than that of N1ICD-Fkbp1aflox/flox cells (Fig. 7Ac,d).

Fig. 7.

Biochemical analysis of N1ICD stability and degradation. (A) Assessment of the N1ICD degradation rate in HEK293 versus FKBP1A-HEK293 cells and in N1ICD-Fkbp1aflox/flox versus N1ICD-Fkbp1aflox/flox/Cre mouse endothelial cells. Cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of cycloheximide (CHX). Representative western blots show the N1ICD protein level at different time points after CHX treatment in HEK293 cells and endothelial cells (EC) of different genotype (a and c), and representative analyses of N1ICD degradation in FKBP1A-HEK293 cells versus control HEK293 cells (b) and N1ICD-Fkbp1aflox/flox versus N1ICD-Fkbp1aflox/flox/Cre endothelial cells (d). (B) Representative western blot of three independent experiments showing that N1ICD protein synthesis is not affected in FKBP1A-HEK293 cells. (C) Ubiquitylated N1ICD is significantly more abundant in FKBP1A-HEK293 cells. To detect the ubiquitylated N1ICD protein, 6× histidine-tagged ubiquitin (His-ubiquitin) plasmid was co-transfected with N1ICD expression plasmid into HEK293 or FKBP1A-HEK293 cells. Transfected cells were incubated with the proteasome inhibitor MG-132 (10 μmol) for 8 hours before cell lysis and Ni-NTA pulldown assay. Error bars indicate s.e.m.

We also evaluated the rate of N1ICD translation. There is no noticeable difference in N1ICD protein synthesis between FKBP1A-HEK293 cells and controls (Fig. 7B; supplementary material Fig. S5). We next blocked ubiquitylation-mediated protein degradation using the proteasome inhibitor MG-132, and assessed the amount of ubiquitylated N1ICD in FKBP1A-HEK293 and control cells. The amount of ubiquitylated N1ICD was significantly higher in FKBP1A-HEK293 cells than in HEK293 control cells (Fig. 7C). Taken together, these data indicate that Fkbp1a regulates the level of activated Notch1 by controlling its stability via ubiquitin-mediated protein turnover.

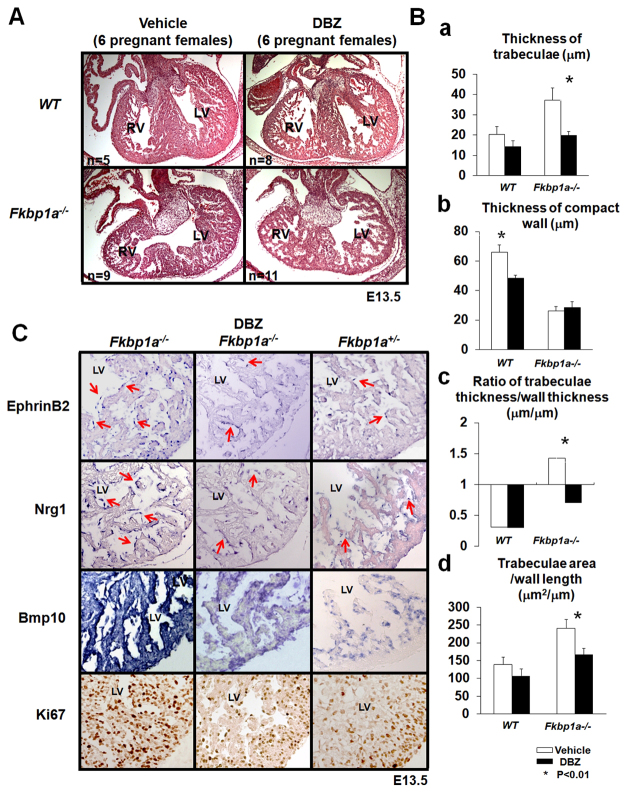

The γ-secretase inhibitor DBZ reduces hypertrabeculation in Fkbp1a-deficient hearts

Clearly, elevated Notch signaling is directly associated with abnormal trabeculation in Fkbp1a mutant embryos. We therefore reasoned that reducing Notch1 activation in vivo would be able to rescue the ventricular morphological defects in Fkbp1a mutant hearts, thereby validating the hypothesized mechanism. We applied the γ-secretase inhibitor DBZ (Milano et al., 2004) to Fkbp1a mutant embryos at E11.5, a stage prior to the appearance of the hypertrabeculation and noncompaction phenotypes (Chen et al., 2009). The pregnant Fkbp1a+/- females that were bred with Fkbp1a+/- males were administrated with DBZ (10 μM/kg via intraperitoneal injection, n=6 females) and vehicle (100 μl, n=6 females). The embryos were harvested at E13.5 and processed for morphological and histological examination. Results show that administration of DBZ significantly diminished the hypertrabeculation phenotypes in Fkbp1a-deficient hearts when compared with vehicle-treated controls (Fig. 8A,Ba). The ratio of trabeculae thickness to compact wall thickness approached a normal morphological distribution (Fig. 8Bc). Remarkably, ventricular septum formation was also greatly improved in all DBZ-treated Fkbp1a-deficient hearts.

Fig. 8.

Rescue of Fkbp1a-deficient mice with the γ-secretase inhibitor DBZ. (A) Representative images of E13.5 hearts isolated from DBZ-treated and control mouse embryos. (B) Quantification of the thickness of trabeculae (a), the thickness of the compact wall (b), the ratio of the thickness of trabeculae and compact wall (c), and the ratio of overall trabecular area versus the length of the compact wall (d). The data demonstrate that the thickness of ventricular trabeculae is reduced in DBZ-treated Fkbp1a-deficient hearts, and the ratio of trabecular thickness versus compact wall thickness is close to normal when compared with controls. Error bars indicate s.e.m. (C) Representative images of three independent sets of Efnb2, Nrg1 and Bmp10 in situ hybridization and Ki67 immunohistological staining of E13.5 hearts from DBZ-treated or vehicle-treated Fkbp1a-deficient and control Fkbp1a heterozygous embryos. LV, left ventricle; RV, right ventricle.

Consistent with the histological findings, in situ hybridization demonstrated that the levels of endocardial Efnb2 and Nrg1, as well as myocardial Bmp10, were significantly reduced in DBZ-treated as compared with vehicle-treated Fkbp1a-/- hearts (Fig. 8C). As further validation, Ki67 immunohistological staining showed that DBZ treatment resulted in strong suppression of cardiomyocyte proliferative activities in both trabecular and compact myocardium within Fkbp1a-/- hearts, showing a more wild-type growth profile (Fig. 8C; supplementary material Fig. S6). However, despite significant reductions in cardiomyocyte hyperproliferation and the myocardial hypertrabeculation phenotype of DBZ-treated mutant hearts, the thickness of the compact wall (ventricular compaction) did not seem to show significant improvement upon DBZ treatment, suggesting that a Notch-independent signaling pathway might contribute in part to the regulation of ventricular wall compaction. Taken together, these findings define an important role for Fkbp1a in regulating Notch1-mediated signaling during ventricular wall development.

DISCUSSION

Ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction are congenital myocardial anomalies that result from disrupted development of the ventricular wall and have been increasingly recognized in the clinic (Chen et al., 2009). Genetic analysis of patients, mostly with isolated forms of ventricular noncompaction without CHDs (congenital heart defects), has demonstrated a broad genetic heterogeneity, suggesting a complex and/or multifactorial network contributing to the etiology and pathogenesis (Chen et al., 2009). Currently, surviving patients carrying FKBP1A mutations have not been reported. Given the pivotal role of Fkbp1a in ventricular wall formation and the embryonic lethal phenotype of Fkbp1a-deficient mice, patients with a germline FKBP1A loss-of-function mutation would seem to have little chance of survival in utero. However, mouse genetic manipulation provides an excellent opportunity to determine the cause and the pathogenetic network that contributes to the ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction, allowing for the identification of genetic pathways that regulate normal ventricular development.

As an isomerase, Fkbp1a presumably functions as a chaperone in maintaining the appropriate conformation of its substrate proteins/peptides, which could be relevant to the regulation of their functional state and/or stability (Lu et al., 2007). Our findings suggest that Fkbp1a has a role in regulating endocardial Notch1 activity, which is crucial to ventricular wall formation. Our findings are entirely consistent with recent reports by Mysliwiec and colleagues that upregulation of Notch1 in endocardial cells leads to ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction (Mysliwiec et al., 2011; Mysliwiec et al., 2012). Most recently, Yang and colleagues demonstrated that upregulated Notch2 activity in Numb/Numb-like compound deficient mutants contributes to Bmp10 upregulation and ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction phenotypes (Yang et al., 2012), further validating our conclusion. However, it should be noted that Tie2-Cre is not endocardial specific, but targets to all endothelial cells including coronary endothelial cells. Nfatc1-Cre expression is initially restricted to the endocardium, and subsequently marks cardiac vascular endothelial cells as the coronary vasculature system develops (Wu et al., 2012). Owing to the spatial-temporal pattern of Cre activity within these lines, we currently cannot distinguish the relative contribution of the different cardiac endothelial cell subtypes. Despite this limitation, it is nonetheless clear that Fkbp1a signaling in cardiac endothelial cells plays a major role in regulating ventricular trabeculation and compaction.

The biochemical mechanism by which Fkbp1a regulates Notch1 activity is likely to involve controlling the stability of N1ICD. Indeed, biochemical analyses in endothelial cells, MEFs and HEK293 cells indicate that Fkbp1a can modulate the stability of activated Notch1. It is well-known that Notch signaling is regulated by post-translational modification events. Activated N1ICD is cleared and thereby inactivated within the cell by ubiquitylation and subsequent proteolysis via the proteasome. This proteasome-dependent degradation of N1ICD is thought to be mediated by interactions of its PEST (proline, glutamic acid, serine and threonine) domain and a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase, Fbxw7 (Oberg et al., 2001). As a known cis-trans peptidyl-prolyl isomerase, one attractive hypothesis is that Fkbp1a regulates the conformation of N1ICD via the proline residues contained within its PEST domain. To test this hypothesis, we used co-immunoprecipitation to determine whether Fkbp1a is able to directly bind N1ICD. However, we have not been able to consistently detect a direct molecular interaction between N1ICD and Fkbp1a (data not shown). This negative result could be due to technical difficulties in capturing transient hit-and-run type interactions between Fkbp1a and N1ICD. Further study employing systematic biochemical analyses will be necessary to determine whether Fkbp1a directly interacts with N1ICD to facilitate its ubiquitylation, or operates via an indirect mechanism. In addition, as Fkbp1a interacts with several other protein complexes, our findings do not exclude the potential involvement of other signaling pathways in contributing to the ventricular wall defects in Fkbp1a mutant hearts. Indeed, although the Notch inhibitor DBZ profoundly reduced cellular hyperproliferation and hypertrabeculation, the noncompaction phenotype was barely affected by DBZ (Fig. 8). This could simply reflect the complex dynamics of ventricular compaction, which involves multiple Notch-mediated signaling pathways in multiple cardiac cell lineages, or there could be an additional unknown parallel signaling pathway(s) that synergistically controls ventricular compaction.

Endothelial cell-restricted ablation of Notch1 and Rbpjk downregulates the expression of both Efnb2 and Nrg1 within endothelial cells and Bmp10 within cardiomyocytes (Grego-Bessa et al., 2007). Both Bmp10 and Nrg1 have been suggested to have a major functional role in the spatial-temporal control of cardiomyocyte proliferation and ventricular trabeculation (Grego-Bessa et al., 2007; Shi et al., 2003). Interestingly, Bmp10 expression can be specifically upregulated by Nrg1 (Kang and Sucov, 2005). In addition, Nrg1 hypomorphic mutants have a significantly reduced Bmp10 expression level (Lai et al., 2010). These findings, both in vitro and in vivo, suggest the interesting idea that Bmp10 is likely to be a downstream target of Nrg1. Endocardial-derived Nrg1 is of particular interest as it signals through its receptor complex, ErbB2/4, which is present only in adjacent cardiomyocytes (Lemmens et al., 2006), providing a unique mechanism for intercellular interactions between two different cardiac cell populations. In zebrafish, the heart is highly trabeculated. A recent study using zebrafish heart as a model system demonstrated that a Nrg1-ErbB2/4 signaling cascade has a dual function: in addition to promoting cardiomyocyte proliferation, it regulates cardiomyocyte delamination and migration (Liu et al., 2010). This dual activity ultimately controls trabeculation in zebrafish. Interestingly, analysis of endocardial-restricted Rbpjk knockouts has shown that exogenous Bmp10 rescues the observed myocardial proliferative defect, whereas Nrg1 does not (Grego-Bessa et al., 2007). Apparently, the Nrg1-ErbB cascade is likely to be part of the evolutionarily conserved mechanism for the regulation of cardiomyocyte delamination that allows for ventricular trabeculation (Liu et al., 2010) or for the regulation of cardiomyocyte differentiation via its pro-differentiation activity (Lai et al., 2010). It would be interesting to determine whether Bmp10 has a similar function in regulating cardiomyocyte proliferation and trabeculation in the highly trabeculated zebrafish heart.

In summary, our study demonstrates a novel genetic and biochemical role for Fkbp1a in regulating Notch1 activity within the endocardium that in part facilitates the intercellular interplay between endocardium and myocardium necessary to define the normal levels of ventricular trabeculation and compaction in the mammalian heart.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Shaoliang Jing and William Carter of Indiana University mouse core for their expert assistance.

Footnotes

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health [grants HL81092 to W.S. and HL85098 to L.J.F., A.B.F., S.J.C. and W.S.]; and by Riley Children’s foundation (to L.J.F., A.B.F., S.J.C. and W.S.). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

Competing interests statement

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material available online at http://dev.biologists.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1242/dev.089920/-/DC1

References

- Ben-Shachar G., Arcilla R. A., Lucas R. V., Manasek F. J. (1985). Ventricular trabeculations in the chick embryo heart and their contribution to ventricular and muscular septal development. Circ. Res. 57, 759–766 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bierer B. E., Mattila P. S., Standaert R. F., Herzenberg L. A., Burakoff S. J., Crabtree G., Schreiber S. L. (1990). Two distinct signal transmission pathways in T lymphocytes are inhibited by complexes formed between an immunophilin and either FK506 or rapamycin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87, 9231–9235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brutsaert D. L. (2003). Cardiac endothelial-myocardial signaling: its role in cardiac growth, contractile performance, and rhythmicity. Physiol. Rev. 83, 59–115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cai C. L., Martin J. C., Sun Y., Cui L., Wang L., Ouyang K., Yang L., Bu L., Liang X., Zhang X., et al. (2008). A myocardial lineage derives from Tbx18 epicardial cells. Nature 454, 104–108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Shi S., Acosta L., Li W., Lu J., Bao S., Chen Z., Yang Z., Schneider M. D., Chien K. R., et al. (2004). BMP10 is essential for maintaining cardiac growth during murine cardiogenesis. Development 131, 2219–2231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen H., Zhang W., Li D., Cordes T. M., Mark Payne R., Shou W. (2009). Analysis of ventricular hypertrabeculation and noncompaction using genetically engineered mouse models. Pediatr. Cardiol. 30, 626–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christoffels V. M., Grieskamp T., Norden J., Mommersteeg M. T., Rudat C., Kispert A. (2009). Tbx18 and the fate of epicardial progenitors. Nature 458, E8–E9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constien R., Forde A., Liliensiek B., Gröne H. J., Nawroth P., Hämmerling G., Arnold B. (2001). Characterization of a novel EGFP reporter mouse to monitor Cre recombination as demonstrated by a Tie2 Cre mouse line. Genesis 30, 36–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Monte G., Grego-Bessa J., González-Rajal A., Bolós V., De La Pompa J. L. (2007). Monitoring Notch1 activity in development: evidence for a feedback regulatory loop. Dev. Dyn. 236, 2594–2614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finsterer J. (2009). Cardiogenetics, neurogenetics, and pathogenetics of left ventricular hypertrabeculation/noncompaction. Pediatr. Cardiol. 30, 659–681 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franco D., de Boer P. A., de Gier-de Vries C., Lamers W. H., Moorman A. F. (2001). Methods on in situ hybridization, immunohistochemistry and beta-galactosidase reporter gene detection. Eur. J. Morphol. 39, 169–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gitler A. D., Kong Y., Choi J. K., Zhu Y., Pear W. S., Epstein J. A. (2004). Tie2-Cre-induced inactivation of a conditional mutant Nf1 allele in mouse results in a myeloproliferative disorder that models juvenile myelomonocytic leukemia. Pediatr. Res. 55, 581–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grego-Bessa J., Luna-Zurita L., del Monte G., Bolós V., Melgar P., Arandilla A., Garratt A. N., Zang H., Mukouyama Y. S., Chen H., et al. (2007). Notch signaling is essential for ventricular chamber development. Dev. Cell 12, 415–429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn W. C., Counter C. M., Lundberg A. S., Beijersbergen R. L., Brooks M. W., Weinberg R. A. (1999). Creation of human tumour cells with defined genetic elements. Nature 400, 464–468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainaud P., Contrerès J. O., Villemain A., Liu L. X., Plouët J., Tobelem G., Dupuy E. (2006). The role of the vascular endothelial growth factor-Delta-like 4 ligand/Notch4-ephrin B2 cascade in tumor vessel remodeling and endothelial cell functions. Cancer Res. 66, 8501–8510 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang X., Rowitch D. H., Soriano P., McMahon A. P., Sucov H. M. (2000). Fate of the mammalian cardiac neural crest. Development 127, 1607–1616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao K., Kulessa H., Tompkins K., Zhou Y., Batts L., Baldwin H. S., Hogan B. L. (2003). An essential role of Bmp4 in the atrioventricular septation of the mouse heart. Genes Dev. 17, 2362–2367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang J. O., Sucov H. M. (2005). Convergent proliferative response and divergent morphogenic pathways induced by epicardial and endocardial signaling in fetal heart development. Mech. Dev. 122, 57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisanuki Y. Y., Hammer R. E., Miyazaki J., Williams S. C., Richardson J. A., Yanagisawa M. (2001). Tie2-Cre transgenic mice: a new model for endothelial cell-lineage analysis in vivo. Dev. Biol. 230, 230–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaassen S., Probst S., Oechslin E., Gerull B., Krings G., Schuler P., Greutmann M., Hürlimann D., Yegitbasi M., Pons L., et al. (2008). Mutations in sarcomere protein genes in left ventricular noncompaction. Circulation 117, 2893–2901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh C., Lee P. W., Yung T. C., Lun K. S., Cheung Y. F. (2009). Left ventricular noncompaction in children. Congenit. Heart Dis. 4, 288–294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai D., Liu X., Forrai A., Wolstein O., Michalicek J., Ahmed I., Garratt A. N., Birchmeier C., Zhou M., Hartley L., et al. (2010). Neuregulin 1 sustains the gene regulatory network in both trabecular and nontrabecular myocardium. Circ. Res. 107, 715–727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemmens K., Segers V. F., Demolder M., De Keulenaer G. W. (2006). Role of neuregulin-1/ErbB2 signaling in endothelium-cardiomyocyte cross-talk. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 19469–19477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Bressan M., Hassel D., Huisken J., Staudt D., Kikuchi K., Poss K. D., Mikawa T., Stainier D. Y. (2010). A dual role for ErbB2 signaling in cardiac trabeculation. Development 137, 3867–3875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu K. P., Finn G., Lee T. H., Nicholson L. K. (2007). Prolyl cis-trans isomerization as a molecular timer. Nat. Chem. Biol. 3, 619–629 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama M., Li B. Y., Chen H., Xu X., Song L. S., Guatimosim S., Zhu W., Yong W., Zhang W., Bu G., et al. (2011). FKBP12 is a critical regulator of the heart rhythm and the cardiac voltage-gated sodium current in mice. Circ. Res. 108, 1042–1052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGill M. A., McGlade C. J. (2003). Mammalian numb proteins promote Notch1 receptor ubiquitination and degradation of the Notch1 intracellular domain. J. Biol. Chem. 278, 23196–23203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milano J., McKay J., Dagenais C., Foster-Brown L., Pognan F., Gadient R., Jacobs R. T., Zacco A., Greenberg B., Ciaccio P. J. (2004). Modulation of notch processing by gamma-secretase inhibitors causes intestinal goblet cell metaplasia and induction of genes known to specify gut secretory lineage differentiation. Toxicol. Sci. 82, 341–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moorman A. F., Christoffels V. M. (2003). Cardiac chamber formation: development, genes, and evolution. Physiol. Rev. 83, 1223–1267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moses K. A., DeMayo F., Braun R. M., Reecy J. L., Schwartz R. J. (2001). Embryonic expression of an Nkx2-5/Cre gene using ROSA26 reporter mice. Genesis 31, 176–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller J. G., Isomatsu Y., Koushik S. V., O’Quinn M., Xu L., Kappler C. S., Hapke E., Zile M. R., Conway S. J., Menick D. R. (2002). Cardiac-specific expression and hypertrophic upregulation of the feline Na(+)-Ca(2+) exchanger gene H1-promoter in a transgenic mouse model. Circ. Res. 90, 158–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mysliwiec M. R., Bresnick E. H., Lee Y. (2011). Endothelial Jarid2/Jumonji is required for normal cardiac development and proper Notch1 expression. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 17193–17204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mysliwiec M. R., Carlson C. D., Tietjen J., Hung H., Ansari A. Z., Lee Y. (2012). Jarid2 (Jumonji, AT rich interactive domain 2) regulates NOTCH1 expression via histone modification in the developing heart. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 1235–1241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oberg C., Li J., Pauley A., Wolf E., Gurney M., Lendahl U. (2001). The Notch intracellular domain is ubiquitinated and negatively regulated by the mammalian Sel-10 homolog. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 35847–35853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozawa T. (2008). Effects of FK506 on Ca release channels. Perspect. Medicin. Chem. 2, 51–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pashmforoush M., Lu J. T., Chen H., Amand T. S., Kondo R., Pradervand S., Evans S. M., Clark B., Feramisco J. R., Giles W., et al. (2004). Nkx2-5 pathways and congenital heart disease; loss of ventricular myocyte lineage specification leads to progressive cardiomyopathy and complete heart block. Cell 117, 373–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pignatelli R. H., McMahon C. J., Dreyer W. J., Denfield S. W., Price J., Belmont J. W., Craigen W. J., Wu J., El Said H., Bezold L. I., et al. (2003). Clinical characterization of left ventricular noncompaction in children: a relatively common form of cardiomyopathy. Circulation 108, 2672–2678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu R., Finkelhor R. S., Gunawardena D. R., Bahler R. C. (2008). Prevalence and characteristics of left ventricular noncompaction in a community hospital cohort of patients with systolic dysfunction. Echocardiography 25, 8–12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber S. L., Crabtree G. R. (1995). Immunophilins, ligands, and the control of signal transduction. Harvey Lect. 91, 99–114 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi W., Chen H., Sun J., Buckley S., Zhao J., Anderson K. D., Williams R. G., Warburton D. (2003). TACE is required for fetal murine cardiac development and modeling. Dev. Biol. 261, 371–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shou W., Aghdasi B., Armstrong D. L., Guo Q., Bao S., Charng M. J., Mathews L. M., Schneider M. D., Hamilton S. L., Matzuk M. M. (1998). Cardiac defects and altered ryanodine receptor function in mice lacking FKBP12. Nature 391, 489–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Srivastava D., Olson E. N. (2000). A genetic blueprint for cardiac development. Nature 407, 221–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sucov H. M., Gu Y., Thomas S., Li P., Pashmforoush M. (2009). Epicardial control of myocardial proliferation and morphogenesis. Pediatr. Cardiol. 30, 617–625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang W., Ingalls C. P., Durham W. J., Snider J., Reid M. B., Wu G., Matzuk M. M., Hamilton S. L. (2004). Altered excitation-contraction coupling with skeletal muscle specific FKBP12 deficiency. FASEB J. 18, 1597–1599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towbin J. A. (2010). Left ventricular noncompaction: a new form of heart failure. Heart Fail. Clin. 6, 453–469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Donahoe P. K. (2004). The immunophilin FKBP12: a molecular guardian of the TGF-beta family type I receptors. Front. Biosci. 9, 619–631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q., Sigmund C. D., Lin J. J. (2000). Identification of cis elements in the cardiac troponin T gene conferring specific expression in cardiac muscle of transgenic mice. Circ. Res. 86, 478–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver A. M., Hussaini I. M., Mazar A., Henkin J., Gonias S. L. (1997). Embryonic fibroblasts that are genetically deficient in low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein demonstrate increased activity of the urokinase receptor system and accelerated migration on vitronectin. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 14372–14379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiford B. C., Subbarao V. D., Mulhern K. M. (2004). Noncompaction of the ventricular myocardium. Circulation 109, 2965–2971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wessels A., Sedmera D. (2003). Developmental anatomy of the heart: a tale of mice and man. Physiol. Genomics 15, 165–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu B., Zhang Z., Lui W., Chen X., Wang Y., Chamberlain A. A., Moreno-Rodriguez R. A., Markwald R. R., O’Rourke B. P., Sharp D. J., et al. (2012). Endocardial cells form the coronary arteries by angiogenesis through myocardial-endocardial VEGF signaling. Cell 151, 1083–1096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y., Ichida F., Matsuoka T., Isobe T., Ikemoto Y., Higaki T., Tsuji T., Haneda N., Kuwabara A., Chen R., et al. (2006). Genetic analysis in patients with left ventricular noncompaction and evidence for genetic heterogeneity. Mol. Genet. Metab. 88, 71–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J., Bücker S., Jungblut B., Böttger T., Cinnamon Y., Tchorz J., Müller M., Bettler B., Harvey R., Sun Q. Y., et al. (2012). Inhibition of Notch2 by Numb/Numblike controls myocardial compaction in the heart. Cardiovasc. Res. 96, 276–285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang S. S., Wei J., Qin H., Zhang L., Xie B., Hui P., Deisseroth A., Barnstable C. J., Fu X. Y. (2004). STAT3-mediated signaling in the determination of rod photoreceptor cell fate in mouse retina. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 45, 2407–2412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B., von Gise A., Ma Q., Rivera-Feliciano J., Pu W. T. (2008). Nkx2-5- and Isl1-expressing cardiac progenitors contribute to proepicardium. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 375, 450–453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W., Soonpaa M. H., Chen H., Shen W., Payne R. M., Liechty E. A., Caldwell R. L., Shou W., Field L. J. (2009). Acute doxorubicin cardiotoxicity is associated with p53-induced inhibition of the mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. Circulation 119, 99–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.