Abstract

AIM: To identify the diagnostic value of colonoscopy for diverticulosis as determined by barium enema.

METHODS: A total of 65 patients with hematochezia who underwent colonoscopy and barium enema were analyzed, and the diagnostic value of colonoscopy for diverticula was assessed. The receiver operating characteristic area under the curve was compared in relation to age (< 70 or ≥ 70 years), sex, and colon location. The number of diverticula was counted, and the detection ratio was calculated.

RESULTS: Colonic diverticula were observed in 46 patients with barium enema. Colonoscopy had a sensitivity of 91% and specificity of 90%. No significant differences were found in the receiver operating characteristic area under the curve (ROC-AUC) for age group or sex. The ROC-AUC of the left colon was significantly lower than that of the right colon (0.81 vs 0.96, P = 0.02). Colonoscopy identified 486 colonic diverticula, while barium enema identified 1186. The detection ratio for the entire colon was therefore 0.41 (486/1186). The detection ratio in the left colon (0.32, 189/588) was significantly lower than that of the right colon (0.50, 297/598) (P < 0.01).

CONCLUSION: Compared with barium enema, only half the number of colonic diverticula can be detected by colonoscopy in the entire colon and even less in the left colon.

Keywords: Colonoscopic diagnosis, Colonic diverticulosis, Colonic diverticular bleeding, Barium enema, Receiver operating characteristic area under the curve

Core tip: We identified the diagnostic value of colonoscopy for colonic diverticulosis as determined by barium enema. The only half the number of colonic diverticula can be detected in the entire colon and even less in the left colon. By revealing the diagnostic value of colonoscopy for colonic diverticula, it may contribute to further therapeutic interventions strategies for the treatment of colonic diverticular disease.

INTRODUCTION

Colonic diverticulosis is a common disease that occurs in approximately one third of the population older than 45 years and in up to two thirds of the population older than 85 years in the United States[1,2]. In Asia, the prevalence of colonic diverticula is 28% and is increasing[3]. The prevalence of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding has also been increasing[4].

Diverticulosis of the colon is often diagnosed during routine screening colonoscopy. In clinical practice, severe diverticulosis anatomically increases the risk of perforation because of fixed angulations, deep folds, and peristalsis of the colon[5-7]. Therefore, the true lumen can sometimes be confused with diverticulosis when multiple large diverticular orifices are encountered. Moreover, circular muscular atrophy with severe diverticula can also create deep crevices in the colonic wall, making polyp detection more difficult[8]. Colonoscopy is usually used to diagnose colonic diverticular bleeding[9,10]. Identification of the bleeding site of colonic diverticula on colonoscopy enables endoscopic treatment with clips[11], epinephrine injection, heat probing[10], and ligation[12]. These modalities can circumvent complications such as hemorrhagic shock and rebleeding[10]. Therefore, identifying the diagnostic value of colonoscopy for colonic diverticula is important but has remained unclear.

By contrast, barium enema can clearly detect colonic diverticula[3] because barium fills the entire colon in diverticulosis. Consequently, we evaluated the diagnostic value of colonoscopy for colonic diverticula in patients with hematochezia who underwent both colonoscopy and barium enema. In addition, differences in diagnostic value with regard to age, sex, and colonic location were assessed.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

We retrospectively selected 436 patients from the electronic endoscopic database who had undergone colonoscopy for hematochezia from 2008 to 2011 at the National Center for Global Health and Medicine. We excluded 355 patients who did not receive barium enema and 16 who did not undergo total colonoscopy. After exclusion, 65 patients were enrolled.

Colonoscopic assessment

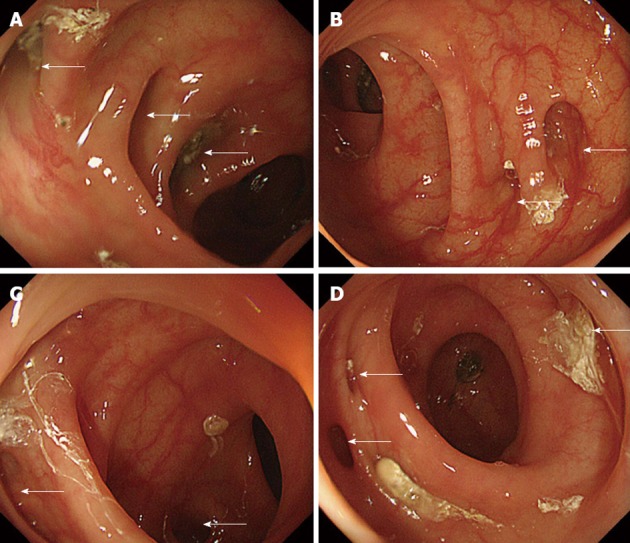

Intestinal lavage for endoscopic examination was performed using 2 L of a solution containing polyethylene glycol. An electronic video endoscope (high-resolution scope, model CFH260; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) was used for the diagnosis of hematochezia by expert endoscopists. The results of the endoscopic examination were saved in the electronic database. Upon detecting diverticula, the location (cecum and ascending, transverse, descending, and sigmoid colon) and number were recorded (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Colonic diverticula in the left colon on endoscopy. The colon location was classified as the right colon (cecum and ascending and transverse colon) or the left colon (descending colon and sigmoid colon). A: Sigmoid-descending colon junction; B: Proximal sigmoid colon; C: Sigmoid top; D: Distal sigmoid colon. Arrows show colonic diverticula determined by colonoscopy.

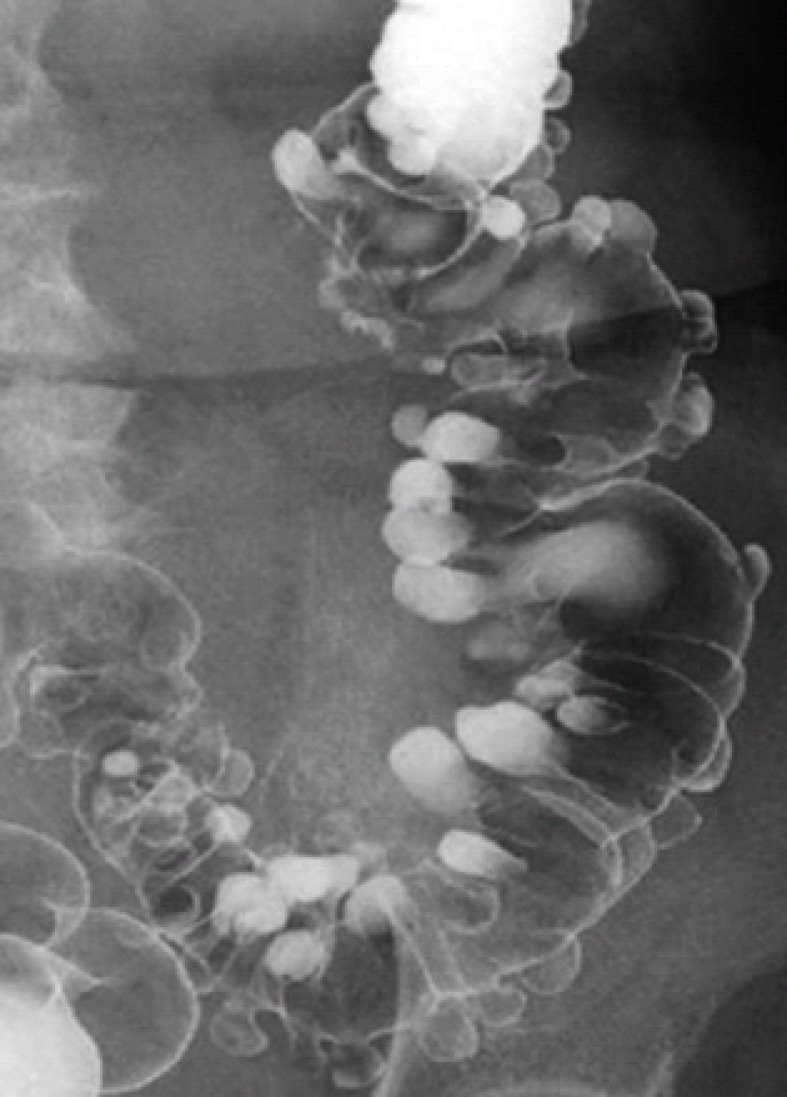

Barium enema examination

Barium enema is a diagnostic imaging modality of the colon that has been used previously to evaluate diverticula[13,14]. Barium enema was indicated for patients with colorectal cancer or to prevent recurrence of colonic diverticular bleeding[6,15,16] and was performed within three days after colonoscopy. Intestinal lavage for the barium enema examination was performed using sodium picosulfate (1 mL) and magnesium citrate (250 mL) the day before the assessment and bisacodyl suppositories (10 mg) on the day of assessment. The barium solution (200-400 mL) was 70%-200%. Barium was injected from the anus to the cecum in all patients to visualize the entire colon tract in different positions. The presence, location, and number of colonic diverticula were determined by radiography (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Colonic diverticula in the left colon on radiography with barium enema. The colonic location was classified as the right colon (cecum and ascending and transverse colon) or the left colon (descending colon and sigmoid colon).

Ethics

This study was approved by the institutional review board of the National Center for Global Health and Medicine (approval number: 765).

Statistical analysis

The gold standard for detecting colonic diverticula is barium enema radiography. To identify the diagnostic value of colonoscopy for colonic diverticula, we calculated the sensitivity, specificity, receiver operating characteristic area under the curve (ROC-AUC), positive likelihood ratio (PLR), and negative likelihood ratio (NLR). In a subgroup analysis, we assessed the diagnostic value of colonoscopy with regard to age, sex, and colonic location. Subjects were divided into two groups according to age: ≥ 70 years old and < 70 years old. The colon location was classified as the left colon (descending and sigmoid colon) and the right colon (cecum and ascending and transverse colon). Differences in the ROC-AUCs were compared in relation to age, sex, and location.

The receiver operating characteristic is a diagnostic test that presents its results as a plot of sensitivity vs 1-specificity (often called the false-positive rate). The ROC-AUC indicates the probability of a measure or predicted risk being higher for patients with disease than for those without disease[17-19]. The detection ratio (colonoscopy/barium enema) of colonic diverticula was assessed and also compared between the left and right colon using the χ2 test. A P value < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 10 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States).

RESULTS

Patient characteristics

Sufficient imaging by colonoscopy and barium enema was obtained for all patients due to adequate stool cleaning. No patients experienced perforation during air insufflation to expand the colon, and none showed a worsened condition such as abdominal pain or nausea after colonoscopy or barium enema. The median age was 73 years, and many patients were elderly men (Table 1). The causes of hematochezia included colonic diverticular bleeding, colonic cancer, and rectal cancer.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (n = 65)

| Sex (male/female) | 40/25 |

| Mean age (IQR) | 73 (66–78) |

| Median duration (IQR) between the onset of hematochezia and colonoscopy | 4 (2–8) |

| Cause of hematochezia | |

| Colonic diverticular bleeding | 30 |

| Colon cancer (cecum/ascending/transverse/sigmoid colon) | 19 (3/8/2/6) |

| Rectal cancer | 14 |

| Unknown | 2 |

IQR: Interquartile range.

Diagnostic value of colonoscopy for colonic diverticula

Colonic diverticula were observed in 46 patients (71%) using barium enema. The number of colonic diverticula identified by colonoscopy was 486, whereas that by barium enema was 1186. Colonoscopy had a sensitivity of 91%, a specificity of 90%, a PLR of 8.7, and an NLR of 0.097 for the diagnosis of colonic diverticula (Table 2).

Table 2.

Diagnostic value of colonoscopy for colonic diverticula in 65 patients

| Number1 | Sens, % (95%CI) | Spec, % (95%CI) | LR (+) (95%CI) | LR (-) (95%CI) | ROC-AUC (95%CI) | P value |

| All (44/21) | 91 (79-98) | 90 (67-99) | 8.7 (2.3-32) | 0.097 (0.038-0.52) | 0.90 (0.82-0.99) | |

| Age (yr) | ||||||

| < 70 (18/9) | 90 (67-99) | 88 (47-100) | 7.2 (1.1-45) | 0.12 (0.032-0.46) | 0.89 (0.74-1) | |

| ≥ 70 (26/12) | 93 (76-99) | 91 (59-100) | 10 (1.6-66) | 0.082 (0.021-0.31) | 0.92 (0.82-1) | 0.68 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female (13/12) | 100 (72-100) | 86 (57-98) | 5.8 (1.8-18) | 0.05 (0.0033-0.76) | 0.93 (0.83-1) | |

| Male (31/9) | 89 (73-97) | 100 (48-100) | 11 (0.74-150) | 0.14 (0.056-0.33) | 0.94 (0.89-1) | 0.47 |

| Location | ||||||

| Right colon (40/25) | 95 (84-99) | 96 (79-100) | 23 (3.4-156) | 0.051 (0.013-0.20) | 0.96 (0.90-1) | |

| Left colon (26/39) | 66 (49-80) | 96 (81-100) | 18 (2.6-123) | 0.36 (0.23-0.56) | 0.81 (0.73-0.90) | 0.02 |

With/without diverticulosis. P values were calculated using the receiver operating characteristic curve area under the curve (ROC-AUC) for comparisons in this category. Sens: Sensitivity; Spec: Specificity; LR: Likelihood ratio.

In a subgroup analysis, no significant differences were found in the ROC-AUCs between age groups and sex. However, the ROC-AUC of the left colon was significantly lower than that of the right colon (0.96 vs 0.81, P = 0.02).

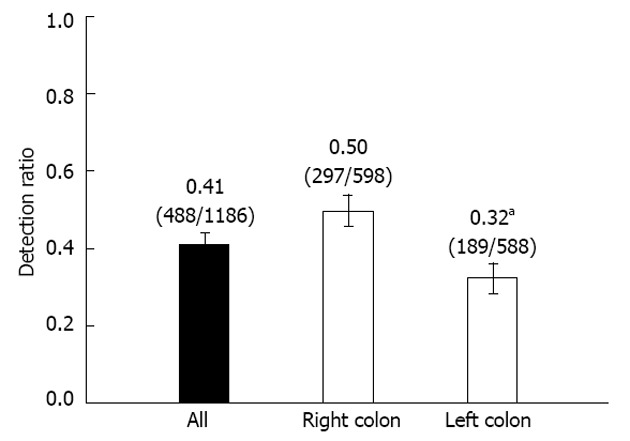

Detection ratio (colonoscopy/barium enema) of colonic diverticula

The detection ratio for the entire colon was 0.41 (486/1186) (Figure 3). The detection ratio for the left colon (0.32, 189/588) was significantly lower than that of the right colon (0.50, 297/598) (P < 0.01).

Figure 3.

Detection ratio (colonoscopy/barium) of colonic diverticula in 65 patients. Right colon denotes the cecum, ascending colon, and transverse colon. Left colon denotes the descending colon and sigmoid colon. aP < 0.05 by χ2 test. Error bars show the 95%CI of the detection ratio.

DISCUSSION

No previous study has reported the diagnostic value of colonoscopy for colonic diverticulosis. Colonoscopy has been used worldwide as a standard tool for the screening of colonic cancer and the diagnosis of other lower gastrointestinal tract diseases[20]. Colonic diverticulosis is a common disease in Asia, Europe, and the United States[2], occurring in approximately one third of the population older than 45 years[1]. The prevalence of colonic diverticulosis increases with age, and serious complications with diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding have been on the rise in recent years[1]. To address these problems, we investigated the diagnostic value of colonoscopy in colonic diverticulosis.

While the detection rate for diverticula with colonoscopy was acceptable, our results showed that the diagnostic value decreased significantly for detection in the left colon. In addition to detecting the presence of diverticula, we counted the number of diverticula in 65 patients and found that colonoscopy detected only one third of the diverticula in the left colon identified by barium enema. The detection rate for diverticula by colonoscopy was higher than that reported previously[21], and this is presumably because a different group of patients was used in this study; Song et al[21] enrolled patients screened by colonoscopy, while the present study investigated patients with hematochezia.

We believe these results were influenced greatly by anatomical factors of the colon, and we thus propose two hypotheses for the poor diagnostic value of colonoscopy in the left colon. First, the diameters of the ascending and transverse colons on the right side of the body are reportedly 4.9 and 4.2 cm, respectively[22]. However, the diameters of the descending and sigmoid colons constituting the left colon are both 3.3 cm, notably narrower than the right colon[22]. Because of the narrower diameter, the field of view in colonoscopy is expected to be lower in the left colon, making the detection of diverticula more difficult. In addition, the sigmoid colon, which accounts for one third of the left colon and is not supported by the mesentery, bends sharply[22]. Intestinal bending not only creates blind spots for colonoscopy but also complicates distinguishing diverticula from the true lumen[5,23], thus greatly affecting the accuracy of diagnosis with colonoscopy.

Although the present study also investigated other factors such as age and sex in addition to anatomical factors, no significant differences were observed. Sadahiro et al[22] investigated age- and sex-related differences in the surface area of the large intestine with barium enema. They found that the mean surface area of the large intestine in men aged ≥ 70 years was 1569.4 cm2, while that in men aged ≤ 69 years was 1566 cm2, with no significant difference. The mean surface area in women aged ≥ 70 years was 1575.4 cm2, while that in women aged ≤ 69 years was 1628 cm2. These results support our finding that the anatomy of the colon is rarely influenced by age or sex. In a previous study on the detection of colonic polyps, it was reported that the degree of bowel preparation[24] and observation time[25] were associated with missed colonic polyps. Although we were unable to evaluate this issue in the present study, we plan to investigate it in the future.

We believe the present findings will influence the diagnosis and treatment of colonic diverticulosis and complications including diverticular bleeding. Knowing the areas of the colon where it is easy to overlook the presence of diverticula or to confuse a diverticulum with a true lumen may help endoscopists perform proper screening colonoscopy and reduce the risk of perforation[5,7,23]. It is important to identify the stigmata of recent hemorrhage (SRH) when diagnosing or treating diverticular bleeding[23]. To date, diagnosis and treatment have been conducted under the assumption that colonoscopy will identify all colonic diverticula regardless of the anatomical factors of the colon. However, our study showed that colonoscopy detected only 32% of all diverticula in the left colon. This suggests that the SRH were overlooked, which is supported by a previous study reporting that colonoscopy identified the SRH in only one third of patients with colonic diverticular bleeding[23].

Here, we evaluated colonic diverticula using static images, but it proved difficult to determine the exact number of colonic diverticula using these images. We therefore plan to perform a prospective study of colonic diverticula using video of live endoscopy procedures.

In the present study, the diagnostic value of colonoscopy for the left colon was relatively low, revealing only one third of the diverticula observed by barium enema. The diagnosis and treatment of colonic diverticulosis and complications, such as diverticular bleeding, should be performed with consideration of the findings of this study.

COMMENTS

Background

Colonic diverticulosis is a common disease, and the prevalence of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding has been increasing. Colonoscopy is useful for diagnosing colonic diverticula and colonic diverticular bleeding. However, the diagnostic value of colonoscopy has remained unclear.

Research frontiers

Colonoscopy is often used to diagnose colonic diverticular bleeding and therefore can be useful for subsequent endoscopic treatment if the bleeding site can be identified. Determining the diagnostic value of colonic diverticula is important. In this study, the authors revealed the diagnostic value of colonic diverticula by colonoscopy.

Innovations and breakthroughs

Previous reports have highlighted the prevalence of diverticula by barium enema. The authors identified the diagnostic value of colonoscopy for colonic diverticulosis as determined by barium enema. The only half the number of colonic diverticula can be detected in the entire colon and even less in the left colon.

Applications

By revealing the diagnostic value of colonoscopy for colonic diverticula, the results of this study may contribute to future therapeutic intervention strategies for the treatment of patients with colonic diverticular disease.

Terminology

The receiver operating characteristic is a diagnostic testing modality that presents its results as a plot of sensitivity vs 1-specificity (often called the false-positive rate). The receiver operating characteristic area under the curve indicates the probability of a measure or predicted risk being higher for patients with disease than for those without disease.

Peer review

The authors evaluated the diagnostic value of colonic diverticula by colonoscopy compared with barium enema. This study revealed that threefold more diverticula can be detected by barium enema than by colonoscopy.

Footnotes

Supported by A grant from the National Center for Global Health and Medicine

P- Reviewers Rajendran VM, Blank G S- Editor Huang XZ L- Editor A E- Editor Li JY

References

- 1.Roberts P, Abel M, Rosen L, Cirocco W, Fleshman J, Leff E, Levien D, Pritchard T, Wexner S, Hicks T. Practice parameters for sigmoid diverticulitis. The Standards Task Force American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Dis Colon Rectum. 1995;38:125–132. doi: 10.1007/BF02052438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WELCH CE, ALLEN AW, DONALDSON GA. An appraisal of resection of the colon for diverticulitis of the sigmoid. Ann Surg. 1953;138:332–343. doi: 10.1097/00000658-195313830-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Miura S, Kodaira S, Shatari T, Nishioka M, Hosoda Y, Hisa TK. Recent trends in diverticulosis of the right colon in Japan: retrospective review in a regional hospital. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:1383–1389. doi: 10.1007/BF02236634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Strate LL, Liu YL, Aldoori WH, Syngal S, Giovannucci EL. Obesity increases the risks of diverticulitis and diverticular bleeding. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:115–122.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kavin H, Sinicrope F, Esker AH. Management of perforation of the colon at colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 1992;87:161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koperna T, Kisser M, Reiner G, Schulz F. Diagnosis and treatment of bleeding colonic diverticula. Hepatogastroenterology. 2001;48:702–705. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brayko CM, Kozarek RA, Sanowski RA, Howells T. Diverticular rupture during colonoscopy. Fact or fancy? Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29:427–431. doi: 10.1007/BF01296218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hale WB. Colonoscopy in the diagnosis and management of diverticular disease. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:1142–1144. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e3181862ab1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossini FP, Ferrari A, Spandre M, Cavallero M, Gemme C, Loverci C, Bertone A, Pinna Pintor M. Emergency colonoscopy. World J Surg. 1989;13:190–192. doi: 10.1007/BF01658398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jensen DM, Machicado GA, Jutabha R, Kovacs TO. Urgent colonoscopy for the diagnosis and treatment of severe diverticular hemorrhage. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:78–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200001133420202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Strate LL, Naumann CR. The role of colonoscopy and radiological procedures in the management of acute lower intestinal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:333–343; quiz e44. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ishii N, Setoyama T, Deshpande GA, Omata F, Matsuda M, Suzuki S, Uemura M, Iizuka Y, Fukuda K, Suzuki K, et al. Endoscopic band ligation for colonic diverticular hemorrhage. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:382–387. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Halligan S, Saunders B. Imaging diverticular disease. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2002;16:595–610. doi: 10.1053/bega.2002.0323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vosse-Matagne G. [Radiologic and endoscopic diagnosis of diverticulosis] Rev Med Liege. 1980;35:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matsuhashi N, Akahane M, Nakajima A. Barium impaction therapy for refractory colonic diverticular bleeding. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;180:490–492. doi: 10.2214/ajr.180.2.1800490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Adams JT. Therapeutic barium enema for massive diverticular bleeding. Arch Surg. 1970;101:457–460. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1970.01340280009003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanley JA. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) methodology: the state of the art. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1989;29:307–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanley JA, McNeil BJ. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982;143:29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Greiner M, Pfeiffer D, Smith RD. Principles and practical application of the receiver-operating characteristic analysis for diagnostic tests. Prev Vet Med. 2000;45:23–41. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5877(00)00115-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schoen RE, Pinsky PF, Weissfeld JL, Yokochi LA, Church T, Laiyemo AO, Bresalier R, Andriole GL, Buys SS, Crawford ED, et al. Colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality with screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2345–2357. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Song JH, Kim YS, Lee JH, Ok KS, Ryu SH, Lee JH, Moon JS. Clinical characteristics of colonic diverticulosis in Korea: a prospective study. Korean J Intern Med. 2010;25:140–146. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2010.25.2.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sadahiro S, Ohmura T, Yamada Y, Saito T, Taki Y. Analysis of length and surface area of each segment of the large intestine according to age, sex and physique. Surg Radiol Anat. 1992;14:251–257. doi: 10.1007/BF01794949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kozarek RA, Earnest DL, Silverstein ME, Smith RG. Air-pressure-induced colon injury during diagnostic colonoscopy. Gastroenterology. 1980;78:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marmo R, Rotondano G, Riccio G, Marone A, Bianco MA, Stroppa I, Caruso A, Pandolfo N, Sansone S, Gregorio E, et al. Effective bowel cleansing before colonoscopy: a randomized study of split-dosage versus non-split dosage regimens of high-volume versus low-volume polyethylene glycol solutions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;72:313–320. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2010.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Barclay RL, Vicari JJ, Doughty AS, Johanson JF, Greenlaw RL. Colonoscopic withdrawal times and adenoma detection during screening colonoscopy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2533–2541. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]