Abstract

Nitric oxide synthases (NOSs) comprise three closely related isoforms that catalyze the oxidation of l-arginine to l-citrulline and the important second messenger nitric oxide (NO). Pharmacological selective inhibition of neuronal NOS (nNOS) has the potential to be therapeutically beneficial in various neurodegenerative diseases. Here we present a structure-guided, selective nNOS inhibitor design based on the crystal structure of lead compound 1 in nNOS. The best inhibitor, 7, exhibited low nanomolar inhibitory potency and good isoform selectivities (nNOS over eNOS and iNOS are 472-fold and 239-fold, respectively). Consistent with the good selectivity, 7 binds to nNOS and eNOS with different binding modes. The distinctly different binding modes of 7, driven by the critical residue Asp597 in nNOS, offers compelling insight to explain its isozyme selectivity, which should guide future drug design programs.

Introduction

Nitric oxide (NO) is a widely utilized second messenger for intracellular signaling cascades invoked by a wide variety of biological stimuli and is of particular functional importance in the central nervous system (CNS).1,2 Nitric oxide synthases (NOSs) catalyze the oxidation of l-arginine to NO and l-citrulline with NADPH and O2 as cosubstrates.3,4 Therefore, these enzymes are involved in a number of important biological processes and are implicated in many chronic neurodegenerative pathologies such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and Huntington’s diseases as well as neuronal damage resulting from stroke, cerebral palsy, and migraine headaches.5–8 For this reason, there is interest in the generation of potent small-molecule inhibitors of NOSs.9,10

NOSs comprise three closely related isoforms: neuronal NOS (nNOS), endothelial NOS (eNOS), and inducible NOS (iNOS).1 Each isoform is characterized by unique cellular and subcellular distribution, function, and catalytic properties.11 While a number of NOS inhibitors have been reported with high affinity, the challenging task is to achieve high selectivity. Because nNOS is abundant in neuronal cells but eNOS is vital in maintaining vascular tone in brain, improvement in the inhibitory selectivity of nNOS over eNOS is very important for lowering the risk of side effects.12,13

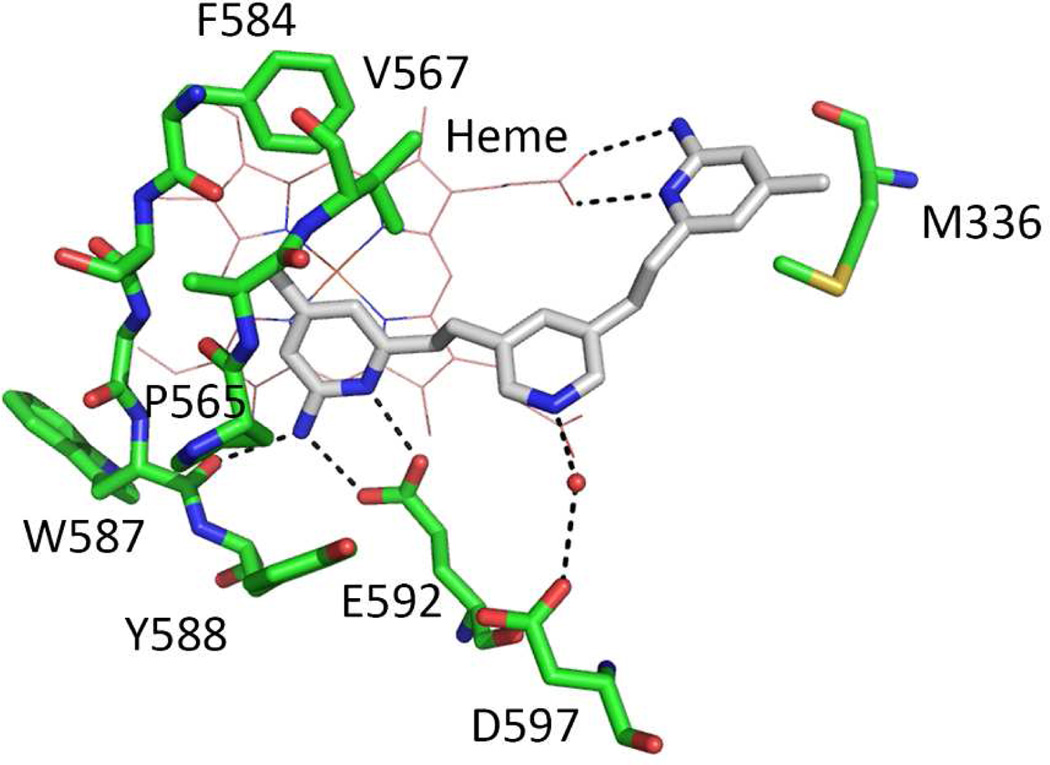

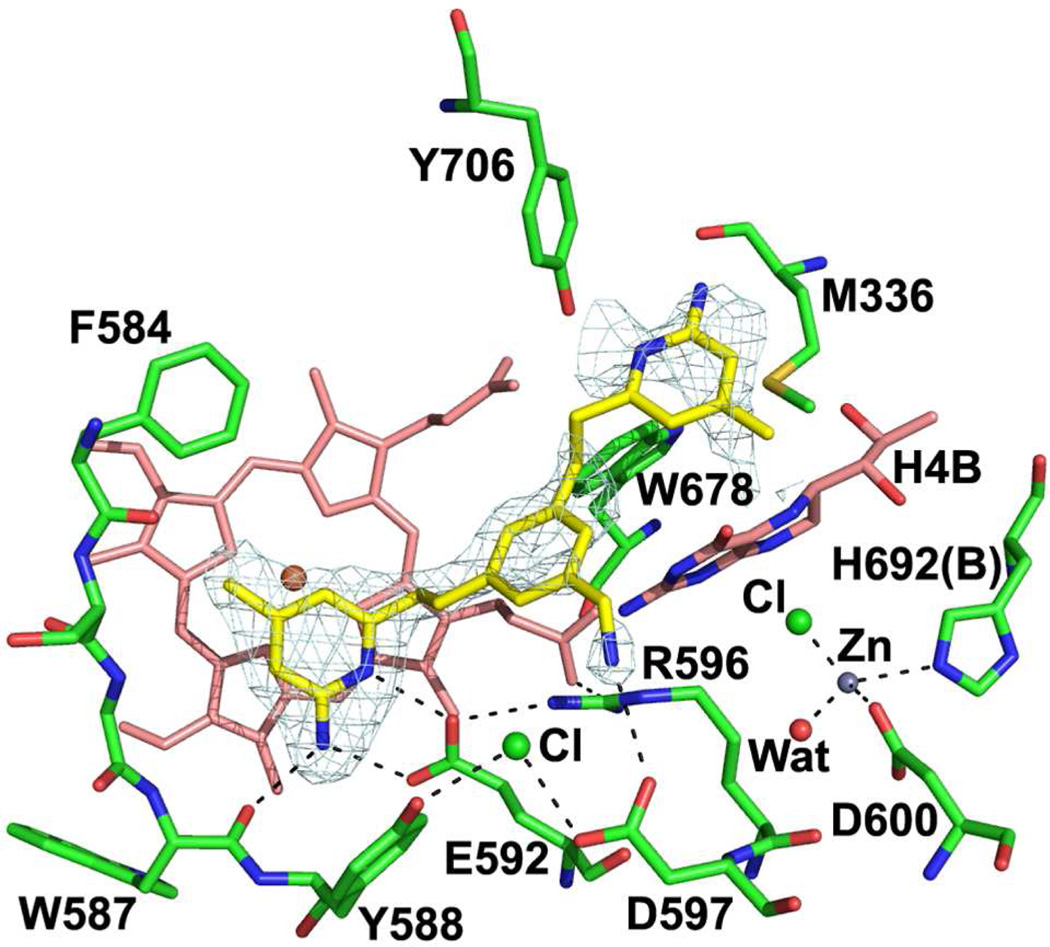

In our continued efforts to develop nNOS selective inhibitors, we discovered a series of highly potent and selective nNOS small molecule inhibitors with a 2-aminopyridinomethyl pyrrolidine scaffold.14,15 Although some of them showed great potency and excellent selectivity for nNOS over eNOS and iNOS, they still suffered from serious limitations, namely, the positive charges derived from the basic groups dramatically impair cell permeability. To overcome this shortcoming, a series of symmetric double-headed aminopyridines without charged groups were designed and synthesized.16 The best inhibitor, 1, shows low nanomolar inhibitory potency and enhanced membrane permeability. However, 1 exhibits low isoform selectivity. We, therefore, used the crystal structure of the nNOS oxygenase domain in complex with 1 as a template to design more selective nNOS inhibitors. As revealed by the crystal structure (Figure 2), while inhibitor 1 shows high affinity to nNOS by utilizing both of its 2-aminopyridine rings to interact with protein residues and heme, it leaves some room near the central pyridine moiety. The central pyridine nitrogen atom of 1 hydrogen bonds via a bridging water molecule with negatively charged residue Asp597. The corresponding residue in eNOS is Asn368. Our studies with a series of dipeptide amide inhibitors had demonstrated23 that the potency of inhibitors can be dramatically increased in eNOS by replacing Asn368 with Asp, while the Ki rises substantially in nNOS if Asp597 is replaced by Asn. Because of the Asp/Asn difference in nNOS and eNOS, the nNOS active site has a more electronegative environment compared to that of eNOS. Therefore, an electropositive functional group is preferred in the vicinity of Asp597 in nNOS. To target interaction with Asp597, here we designed and synthesized a series of nNOS inhibitors (Figure 3) that contain a tail on the central aromatic ring with various lengths and different substitution groups at the terminus.

Figure 2.

Crystallographic binding conformation of 1 (PDB ID 3N5W) with rat nNOS. All structural figures were prepared with PyMol (www.pymol.org).

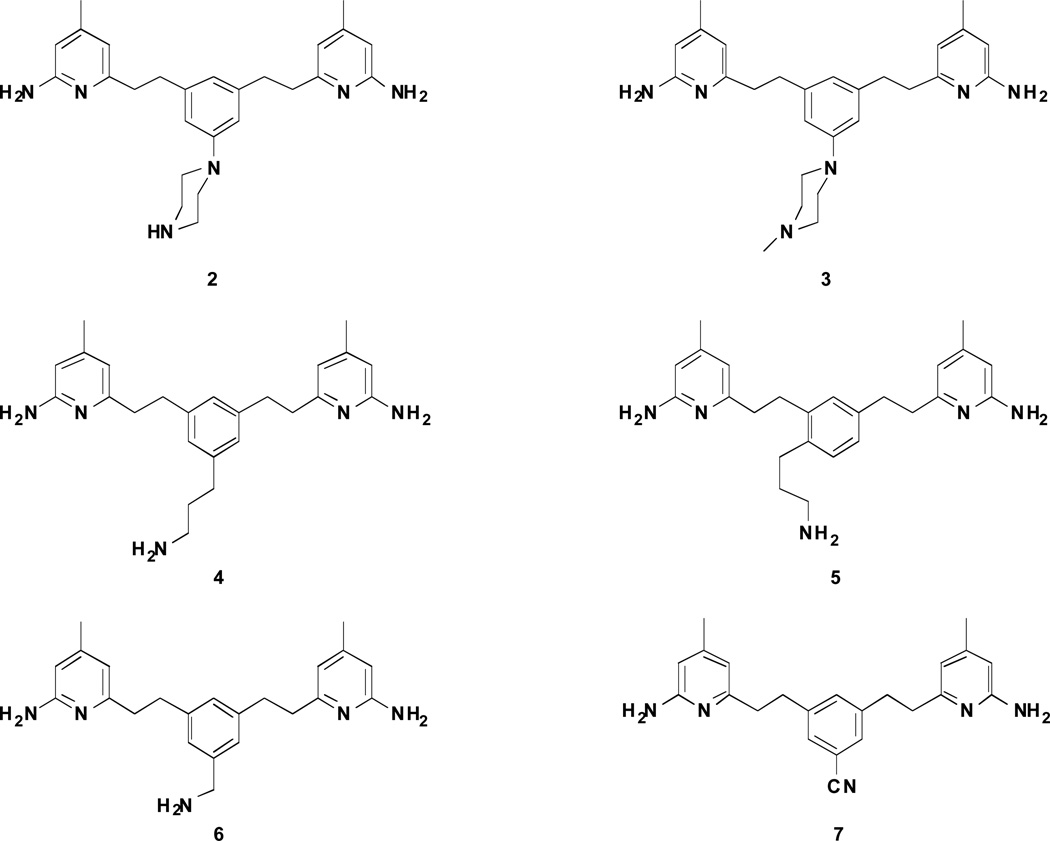

Figure 3.

Target molecules designed and synthesized in this study

To synthesize inhibitors 2–5 (Scheme 1), the carboxyl groups of bromo-substituted isophthalic acids were reduced to alcohols in good yields, and then bromination generated intermediates 9a and 9b. 2-(2,5-Dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-1-yl)-4,6-dimethylpyridine was treated with n-butyllithium and was allowed to react with 9a or 9b. Subsequently, a palladium-catalyzed amination of 10a and 10b with N-monosubstituted piperazines gave corresponding aromatic amines 11 and 12. Deprotection of 11 and 12 gave 13 and target compound 3, respectively. Finally, the removal of the Boc-protecting group of 13 proceeded smoothly, giving a high yield of 2.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of 2–5a

a Reagents and conditions: (a) LiBH4, TMSCl, THF, rt, 12 h, 82–86%; (b) PPh3, CBr4, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, 2 h, 89–92%; (c) 9a or 9b, n-BuLi, THF, −78 °C to rt, 2 h, 48–56%; (d) Pd2(dba)3, BINAP, NaOtBu, PhMe, 80 °C, 8 h, 61–67 %; (e) NH2OH·HCl, EtOH/H2O (2:1), 100 °C, 36 h, 58–69%; (f) 3N HCl/MeOH, rt, 24 h, quantitative; (g) PdCl2, DIEA, Tri(o-tolyl)phosphine, DMF, 120 °C, 8 h, 58–64%; (h) NH2OH·HCl, EtOH/H2O (2:1), 100 °C, 36 h, 49–56%; (i) H2, Pd/C, MeOH, rt, 12 h, quantitative; (j) 3N HCl/MeOH, rt, 24 h, quantitative.

The palladium-catalyzed Heck coupling reactions of tert-butyl allylcarbamate with 10a and 10b gave corresponding alkenes 14a and 14b. The 2,5-dimethylpyrrole protecting groups of 14a and 14b were removed with NH2OH·HCl at 100 °C to generate 15a and 15b in moderate yields. Finally, catalytic hydrogenation and the removal of the Boc-protecting group proceeded smoothly, giving high yields of 4 and 5.

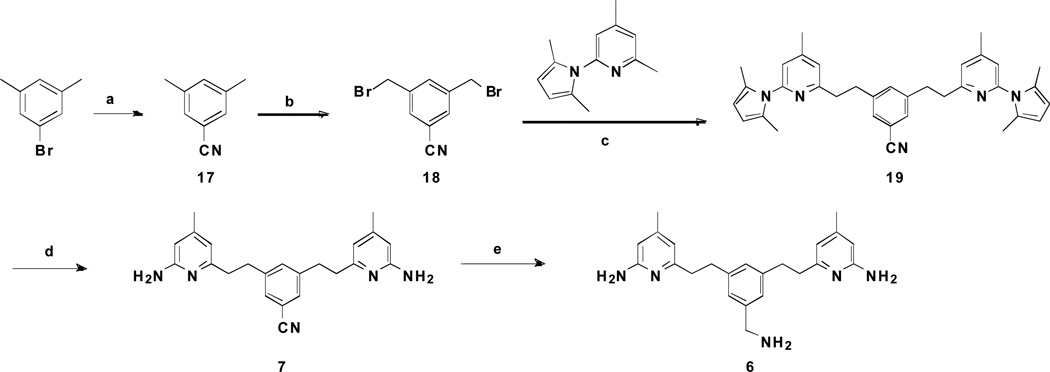

The synthesis of 6 and 7 began with 1-bromo-3,5-dimethylbenzene. It was subjected to cyanation with CuCN, and subsequent bromination with NBS to afford 3,5-bis(bromomethyl)benzonitrile 18 in a 22% yield. 2-(2,5-Dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-1-yl)-4,6-dimethylpyridine was then treated with n-butyllithium and allowed to react with 18 to form 19 in a 48% yield. The 2,5-dimethylpyrrole protecting groups of 19 were removed with NH2OH·HCl at 100 °C to generate 7 in a 31% yield. Reduction of the cyano group in 7 gave 6 in a moderate yield.

Results and Discussion

All of the compounds tested were competitive inhibitors against substrate L-arginine. The first of the analogues prepared (Figure 3, 2) retains the double 2-aminopyridine heads but with a piperazino tail at the 5-position of the central phenyl core. It showed moderate inhibition, with a Ki value of 2.1 µM for nNOS and nNOS selectivities over eNOS and iNOS of 30-fold and 17-fold, respectively (Table 1). Blocking the terminal N atom of the piperazino tail with a methyl group (3) slightly increases the size, which tends to decrease the potency and nNOS selectivity over eNOS, but affords a slight increase in selectivity over iNOS. The nNOS-2 complex crystal structure (data not shown) revealed electron density for only the 2-aminopyridine near Glu592 with the rest of the inhibitor fully disordered. These results suggest that the steric bulk of the piperazino group hinders interaction between the second amino pyridine group and the enzyme.

Table 1.

Inhibition of NOS isozymes by synthetic inhibitorsa

| No. | Ki (µM) | Selectivity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| nNOS | eNOS | iNOS | n/e | n/i | |

| 2 | 2.10 | 63.2 | 36.7 | 30 | 17 |

| 3 | 5.75 | 97.4 | 138.0 | 17 | 24 |

| 4 | 0.54 | 12.1 | 32.5 | 22 | 60 |

| 5 | 0.11 | 33.4 | 21.9 | 303 | 199 |

| 6 | 0.053 | 11.7 | 6.31 | 221 | 119 |

| 7 | 0.056 | 26.4 | 13.4 | 472 | 239 |

The compounds were evaluated for in vitro inhibition against three NOS isozymes: rat nNOS, bovine eNOS, and marine iNOS using known literature methods. (Hevel, J.M.; Marletta, M.A. Nitric-oxide synthase assays. Method Enzymol. 1994, 233, 250–258)

We reasoned that only relatively small substituents would be tolerated at the 5-position of the phenyl core. Moreover, there is more space available between Glu592 and the 4-position of the phenyl core. To test whether smaller and flexible substituents could increase the potency and selectivity, we designed inhibitors 4 and 5. The 5-substituted compound (4) displays a Ki value of 0.54 µM with nNOS, which is 4- and 10-fold lower than those of 2 and 3, respectively. Compared to 2, 4-substituted compound 5 exhibits about 19-fold better inhibitory potency (Ki = 0.11 µM) and 20-fold better selectivity for nNOS over eNOS and iNOS (n/e = 303; n/i = 199).

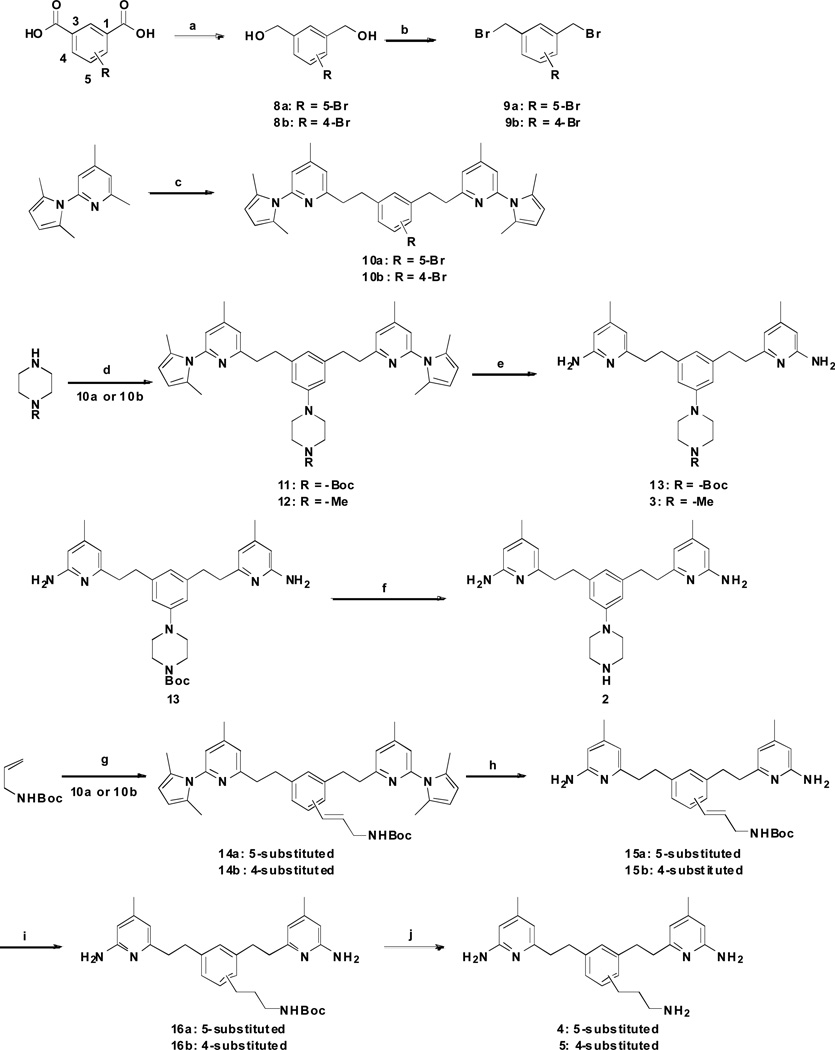

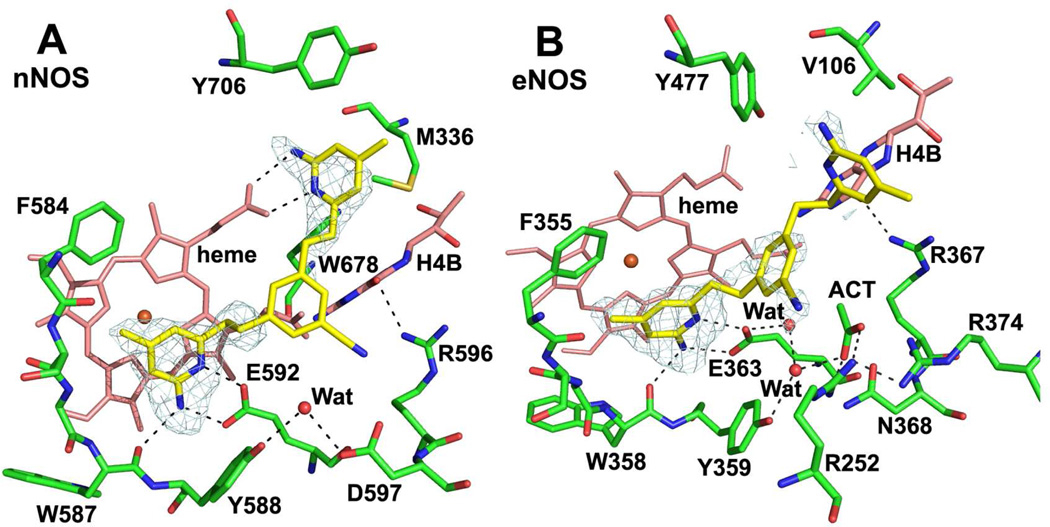

To better understand structure-activity relationships for 4 and 5, the crystal structures of nNOS complexed with these inhibitors were determined. In contrast to the binding mode of 1 where both 2-aminopyridine heads are involved in hydrogen bonds with Glu592 and heme, one of 2-aminopyridine groups of 4 interacts with Glu592 to anchor the inhibitor to the nNOS active site, but the other 2-aminopyridine replaces the cofactor H4B stacking with Trp678. Inhibitor binding also promotes the binding of a new zinc ion ligated by Asp600 and His692 (chain B) along with a chloride ion and a water molecule (Fig. 4A). A similar binding mode that kicks out at 2.5 σ contour level. Binding of 4 replaces H4B and creates a new Zn binding site. Arg596 is then salt bridged to Glu592 rather than to Asp600 as in the Zn-free structure. Interestingly, 4 was found not to be competitive with H4B (data not shown). H4B was also observed with another inhibitor bearing two 2-aminopyridine heads.16 As expected from our design, the terminal N atom of the 3-aminopropyl moiety approaches residue Asp597. However, the density for this side chain is rather poor compared to the other part of inhibitor indicative of flexibility of the tail, suggesting that other positions on the tail that are somewhat distant from Asp597 also are possible sites of attachment of the binding group.

Figure 4.

Crystallographic binding conformations of 4 (A, PDB ID 4IMS) and 5 (B, PDB ID 4IMT) with rat nNOS. The Fo – Fc omit density map for inhibitor is shown

Similar to the binding mode of 1, 4-substituted compound 5 binds to nNOS with one of its 2-aminopyridine heads interacting with Glu592 and the other making bifurcated hydrogen bonds with heme propionate D (Fig. 4B). Again, the density for its 3-aminopropyl tail is so poor that there is ambiguity even at a lower contour level (0.5 σ, 2Fo – Fc map) as to which way the terminal N atom goes. Two different binding modes were modeled with one extending out away from Asp597 in one monomer of the heme domain dimer (Fig. 4B) and the other one interacting with Asp597 in the other monomer.

Note that 4 interacts with Asp597, which was our primary goal. One particularly interesting finding that emerged from the crystal structure is that the 3-aminopropyl tail on the central core is relatively long and flexible and thus tends to be disordered. On the basis of these observations and a desire to further improve the potency and selectivity, we decided to pursue additional changes to the 3-aminopropyl tail of 4. Compound 6, with a shorter tail on the phenyl core, has a 10-fold better nNOS inhibitory potency and 20-fold better selectivity for nNOS over eNOS than those of 4. Crystal structures of nNOS complexed with 6 (Figure 5) shows that the aminomethyl substituent is ordered and small enough to fit within the cavity allowing a weaker hydrogen bond (3.2 – 3.4 Å) with Asp597. However, this time, the interaction between Asp597 and the tail N atom pulls the phenyl core so that the second 2-aminopyridine head cannot make bifurcated hydrogen bonds with the heme propionate of pyrrole ring D, leading to partial disorder (poor density).

Figure 5.

Crystallographic binding conformations of 6 (PDB ID 4IMU) with rat nNOS. The Fo – Fc omit density map for inhibitor is shown at 2.5 σ contour level. Although binding of 6 does not disturb the H4B site it still creates a new Zn binding site. Arg596 is also salt bridged with Glu592.

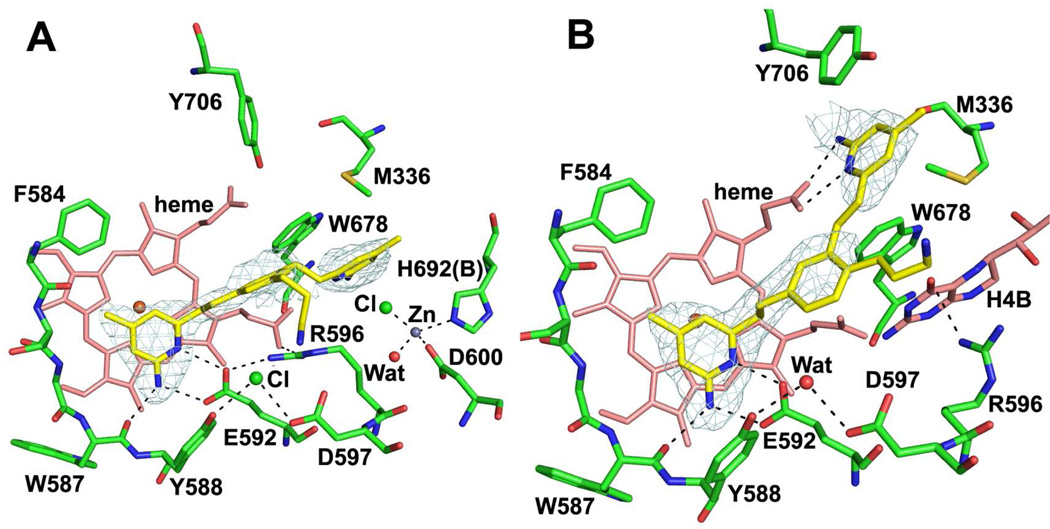

Replacement of the water-mediated pyridine fragment by a cyanophenyl group is a known structure modification;17 therefore, we explored the effect of cyano substitution at the 5-position of the phenyl core. Its Ki value with nNOS is 56 nM, and the selectivities for nNOS over eNOS and iNOS are 472-fold and 239-fold, respectively. We have also determined the crystal structures of 7 complexed to both nNOS and eNOS. As expected from the structure-guided design, the double heads of 7 bind to the active site of nNOS in a similar pattern as those of parent inhibitor 1: one interacts with Glu592, while the other forms bifurcated hydrogen bonds with heme propionate D and has aromatic π-stacking with Tyr706 (Figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Crystallographic binding conformations of 7 with rat nNOS (A, PDB ID 4IMW) and bovine eNOS (B, PDB ID 4IMX). The Fo – Fc omit density map for inhibitor is shown at 2.5 σ contour level. For eNOS an extra acetate ion is shown that is salt bridged between two Arg residues.

Unfortunately, the key part of the inhibitor, the cyanophenyl ring, shows poorer density. The model built is supported by density at the lower contour level (0.5 σ, 2Fo – Fc map), where the N atom of the cyano group faces Asp597 but is a little too far (>3.5 Å) for a strong hydrogen bond.

Consistent with the poorer binding affinity to eNOS, in the eNOS-7 complex (Figure 6B), 7 exhibits a different binding mode with only one 2-aminopyridine hydrogen bonded with Glu363, while the other one is partially disordered showing poor density. In this binding mode the cyanophenyl part folds upwards away from Asn368 with the cyano nitrogen atom hydrogen bonded to Ser248. In the eNOS-7 complex structure there is an acetate ion that is in the vicinity of Asn368 and forms salt bridges with two basic residues, Arg252 and Arg374. This acetate has been observed in many eNOS-inhibitor complex structures. It is possible that this acetate prevents the cyanophenyl group of 7 from interacting with Asn368. However, the presence of a negatively-charged acetate in the vicinity of Asn368 is a consequence of the electropositive nature of the environment at this site. This is most likely the reason for the cyanophenyl to steer away from Asn368 in eNOS. The binding mode with eNOS explains why 7 has better selectivity for nNOS over eNOS than does 1, which showed an identical 2-headed binding mode with both isoforms.16 As noted above, the key differences we targeted between nNOS and eNOS is the Asp597/Asn368 difference in the active site pocket. The distinctly different binding modes of 7 driven by this critical residue in nNOS and eNOS afford a high degree of selectivity.

From our exploration of the structure-activity relationship of the symmetric double-headed 2-aminopyridines, 7 remains the most selective compound we have discovered, while maintaining good potency against nNOS.

Conclusions

The NOS active site is highly conserved; therefore, achieving selectivity for nNOS inhibition is extremely difficult. Through structure-guided design, we confirm that the nNOS inhibitor potency and selectivity can be achieved by introducing electropositive functional groups that can interact with Asp597 in nNOS. In this study we demonstrate that the potent and selective nNOS inhibitor 7 binds to nNOS and eNOS with different binding modes because of the Asp597/Asn368 difference and, thus, exhibits the best selectivity in the series. Furthermore, the active substituent in 7 is a cyano group, which is not basic and not positively charged, as is the case with the amino substituents. This should be favorable for bioavailability. The results imply that inhibitors with a benzonitrile core should be nNOS selective. Our best compound 7, which not only retains the affinity with nNOS but also shows significantly improved selectivity against other NOS isoforms, is a good templete for the further design of selective nNOS inhibitors.

Experimental Section

All reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, Alfa Aesar, or TCI and were used without further purification unless stated otherwise. Analytical thin layer chromatography was visualized by ultraviolet light, ninhydrin, or phosphomolybdic acid. Flash column chromatography was carried out under a positive pressure of air. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on 500 MHz spectrometers. Data are presented as follows: chemical shift (in ppm on the δ scale, and the reference resonance peaks set at 0 ppm [TMS(CDCl3)], 3.31 ppm (CD2HOD), 4.80 ppm (HOD), and 7.26 ppm (CDCl3)), multiplicity (s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, m = multiplet), coupling constant (J/Hz), integration. 13C NMR spectra were recorded at 125 MHz, and all chemical shift values are reported in ppm on the δ scale, with an internal reference of δ 77.0 or 49.0 for CDCl3 or CD3OD, respectively. High-resolution mass spectra were measured on a liquid chromatography/time-of-flight mass spectrometry (LC-TOF). The purity of the tested compounds was determined by HPLC analysis and was >95%.

General procedure A: LiBH4 reduction

TMSCl (2.4 mmol) was added to a suspension of LiBH4 (2.4 mmol) in anhydrous THF (20 mL) at 0 °C. The reaction mixture was stirred under argon for 30 min at room temperature. To this reaction mixture was added dropwise bromo-substituted isophthalic acids or 7 (1.0 mmol) in anhydrous THF (2 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred for 12 h at room temperature. The reaction mixture was then quenched with MeOH in an ice bath, extracted with EtOAc, and washed with water and brine. The organic layer was concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography to yield 8a, 8b, or 6.

General procedure B: Synthesis of 2,5-dimethylpyrrole-protected intermediates

To a solution of 2-(2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrol-1-yl)-4,6-dimethyl-pyridine (1.0 mmol) in THF (20 mL) at −78 °C was added n-BuLi (1.6 M solution in hexanes, 2.5 mmol) dropwise. The resulting dark red solution after the addition was transferred to an ice bath. After 30 min, a solution of bromide 9a, 9b, or 18 (0.5 M in THF) was added dropwise until the dark red color disappeared. The reaction mixture was allowed to stir at 0 °C for an additional 10 min and then quenched with H2O. The solvent was removed by rotary evaporation, and the resulting yellow oil was purified by flash chromatography to yield 2,5-dimethylpyrrole-protected intermediates 10a, 10b, or 19.

General procedure C: 2,5-Dimethylpyrrole deprotection

To a solution of 11, 12, 14a, 14b, or 19 (0.5 mmol) in EtOH (20 mL) was added hydroxylamine hydrochloride (5 mmol) followed by H2O (10 mL). The reaction mixture was heated at 100 °C for 24 h. After cooling to room temperature, the mixture was partitioned between Et2O (25 mL) and 2 N NaOH (50 mL). The aqueous layer was extracted with Et2O (2 × 25 mL), and the combined organic layers were dried over Na2SO4. The solvent was removed by rotary evaporation, and the resulting yellow oil was purified by flash chromatography to yield products 3, 7, 13, 15a or 15b.

General procedure D: Boc deprotection

To a solution of 13, 16a, or 16b (0.2 mmol) in MeOH (1.0 mL) was added 3 N HCl (10.0 mL). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 24 h. Then the reaction mixture was concentrated in vacuo. The crude product was recrystallized with cold diethyl ether to provide 2, 4, or 5.

6,6'-((5-(Piperazin-1-yl)-1,3-phenylene)bis(ethane-2,1-diyl))bis(4-methylpyridin-2-amine) (2)

Intermediate 8a was synthesized by general procedure A using 5-bromoisophthalic acid as the starting material (yield 86%). To a suspension of 8a (1.0 mmol) in dry CH2Cl2 (10 mL) was added PPh3 (2.1 mmol) and CBr4 (2.1 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 2 h and then quenched with H2O, extracted with CH2Cl2, and washed with water and brine. The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography to yield 9a (yield 89%). Compound 10a was synthesized by general procedure B using 9a as the starting material (yield 48%). To a suspension of 10a (1.0 mmol), 1-Boc-piperazine, and NaOtBu (1.0 mmol) in dry toluene (10 mL) was added Pd2(dba)3 (0.05 mmol) and BINAP (0.1 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 8 h. The reaction mixture was then diluted with H2O (20 mL), extracted with EtOAc, and washed with water and brine. The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography to yield 11 (yield 67%). Compound 2 was synthesized by general procedures C and D using 11 as the starting material (yield 58%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O): δ 6.64 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 2H), 6.56 (s, 1H), 6.46 (s, 2H), 6.23 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 2H), 3.29-3.25 (m, 8H), 2.82-2.81 (m, 8H), 2.09 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, D2O): δ 157.75, 153.44, 148.52, 147.93, 141.52, 123.77, 116.34, 114.46, 109.38, 47.47, 42.69, 33.84, 29.49, 20.96. LC-TOF (M + H+) calcd for C26H35N6 431.2923, found 431.2917.

6,6'-((5-(4-Methylpiperazin-1-yl)-1,3-phenylene)bis(ethane-2,1-diyl))bis(4-methylpyridin-2-amine) (3)

Compound 3 was synthesized by the same procedures as those to prepare 2 using 1-methylpiperazine as the starting material. 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 6.63 (s, 3H), 6.348 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 2H), 6.20 (s, 2H), 3.19 (t, J = 5.0 Hz, 4H), 2.95-2.80 (m, 8H), 2.64-2.55 (m, 4H), 2.37 (s, 3H), 2.20 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 157.82, 148.81, 142.64, 141.84, 123.94, 120.45, 114.48, 114.09, 106.69, 55.15, 49.14, 46.07, 39.70, 36.44, 21.08. LC-TOF (M + H+) calcd for C27H37N6 445.3080, found 445.3073.

6,6'-((5-(3-Aminopropyl)-1,3-phenylene)bis(ethane-2,1-diyl))bis(4-methylpyridin-2-amine) (4)

Intermediate 14a was synthesized by the same procedures as those to prepare 2 using Boc-allylamine as the starting material. Compound 15a was synthesized by general procedure C using 14a as the starting material (yield 49%). To a solution of 15a (0.2 mmol) in MeOH (10 mL) was added 10% Pd/C (10 mg). The reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature under a hydrogen atmosphere for 12 h. The catalyst was removed by filtration through Celite, and the resulting solution was concentrated in vacuo. The crude material was purified by column chromatography to yield 16a. 4 was synthesized by general procedure D using 16a as the starting material (quantitative). 1H NMR (500 MHz, D2O): δ 6.77 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 2H), 6.67 (t, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 6.45 (s, 2H), 6.23 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 2H), 2.79 (s, 8H), 2.76-2.70 (m, 2H), 2.48-2.44 (m, 2H), 2.08 (s, 6H), 1.75-1.69 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, D2O): δ 162.68, 157.75, 153.40, 148.08, 141.36, 140.23, 126.67, 114.40, 109.35, 38.95, 33.71, 33.60, 31.56, 29.44, 20.96. LC-TOF (M + H+) calcd for C25H34N5 404.2814, found 404.2808.

6,6'-((4-(3-Aminopropyl)-1,3-phenylene)bis(ethane-2,1-diyl))bis(4-methylpyridin-2-amine) (5)

Compound 5 was synthesized by the same procedure as that to prepare 4 using 4-bromoisophthalic acid as the starting material. 1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD): δ 6.97-6.95 (m, 1H), 6.90-6.87 (m, 2H), 6.20-6.18 (m, 4H), 2.94-2.84 (m, 2H), 2.82-2.75 (m, 4H), 2.68-2.61 (m, 4H), 2.60-2.55 (m, 4H), 2.07 (s, 6H), 1.26-1.23 (m, 2H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, MeOD): δ 160.33, 160.31, 160.12, 158.51, 152.01, 151.95, 151.93, 140.29, 137.19, 130.88, 130.21, 127.64, 127.62, 114.72, 114.62, 108.26, 39.95, 39.85, 36.70, 35.30, 30.35, 29.99, 23.89, 21.16, 21.13. LC-TOF (M + H+) calcd for C25H34N5 404.2814, found 404.2806.

6,6'-((5-(Aminomethyl)-1,3-phenylene)bis(ethane-2,1-diyl))bis(4-methylpyridin-2-amine) (6)

Compound 6 was synthesized by general procedure A using 7 as the starting material (yield 42%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, MeOD): δ 7.06-6.96 (m, 3H), 6.34-6.21 (m, 4H), 2.92-2.88 (m, 4H), 2.85-2.73 (m, 6H), 2.17 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, MeOD): δ 161.51, 160.68, 151.03, 129.67, 129.61, 126.26, 119.69, 114.67, 107.90, 40.66, 37.29, 24.25, 21.05. LC-TOF (M + H+) calcd for C23H30N5 376.2501, found 376.2495.

3,5-Bis(2-(6-amino-4-methylpyridin-2-yl)ethyl)benzonitrile (7)

To a solution of 1-bromo-3,5-dimethylbenzene (5 mmol) in dry DMF (20 mL) was added CuCN (6 mmol). The reaction mixture was stirred at 180 °C under N2 for 6 h. The solid was removed by filtration through Celite, and the resulting solution was diluted by H2O, extracted with EtOAc, and washed with water and brine. The organic layer was dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography to yield 17 (yield 84%). To a suspension of 17 (4.0 mmol) in dry CCl4 (40 mL) was added NBS (8 mmol) and BPO (cat.). The reaction mixture was stirred at 80 °C for 6 h. The mixture was concentrated in vacuo and then purified by column chromatography to yield 18 (yield 22%). Compound 7 was synthesized by general procedures B and C using 18 (0.5 mmol) as the starting material (two-steps yield 14.8%). 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 7.28 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 2H), 7.27-7.26 (m, 1H), 6.25 (s, 2H), 6.18 (s, 2H), 3.00-2.91 (m, 4H), 2.86-2.77 (m, 4H), 2.17 (s, 6H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3): δ 158.23, 158.19, 149.51, 143.10, 133.66, 129.69, 119.33, 114.44, 111.92, 106.86, 39.16, 35.40, 21.00. LC-TOF (M + H+) calcd for C23H26N5 372.2188, found 372.2183.

Enzyme Assays

The three isozymes, rat nNOS, murine macrophage iNOS, and bovine eNOS, were recombinant enzymes, overexpressed (in E. coli) and isolated as reported.18–20 Ki determined for inhibitors 2–7 with the three different isoforms of NOS using l-arginine as a substrate. The formation of nitric oxide was measured using the hemoglobin capture assay described previously.21 All NOS isozymes were assayed using the Synergy H1 Hybrid Multi-Mode Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments, Inc.) at 37 °C in a 100 mM Hepes buffer (pH 7.4) containing 10 µM l-arginine, 0.83 mM CaCl2, 320 units/mL calmodulin, 100 µM NADPH, 10 µM H4B, 3.0 µM oxyhemoglobin (for iNOS assays, no Ca2+ and calmodulin was added). The assay was initiated by the addition of enzyme, and the initial rates of the enzymatic reactions were determined by monitoring the formation of NO-hemoglobin complex at 401 nm for 60 sec. The apparent Ki values were obtained by measuring the percent enzyme inhibition in the presence of 10 µM l-arginine with at least five concentrations of inhibitor. The parameters of the following inhibition equation were fitted to the initial velocity data: % inhibition = 100[I]/{[I] + Ki(1+[S]/Km)}. Km values for l-arginine were 1.3 µM (nNOS), 8.2 µM (iNOS), and 1.7 µM (eNOS). The selectivity of an inhibitor was defined as the ratio of the respective Ki values.

Inhibitor Complex Crystal Preparation

The nNOS or eNOS heme domain proteins used for crystallographic studies were produced by limited trypsin digestion from the corresponding full length enzymes and further purified through a Superdex 200 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare), as described previously.22,23 The nNOS heme domain at 7–9 mg/mL containing 20 mM histidine or the eNOS heme domain at 12 mg/mL containing 2 mM imidazole were used for the sitting drop vapor diffusion crystallization setup under the conditions reported before.23, 24 Fresh crystals (1–2 day old) were first passed stepwise through cryo-protectant solutions as described22, 24 and then soaked with 10 mM inhibitor for 4–6 h at 4 °C before being mounted on nylon loops and flash cooled by plunging into liquid nitrogen.

X-ray Diffraction Data Collection, Processing, and Structure Refinement

The cryogenic (100 K) X-ray diffraction data were collected remotely at various beamlines at Stanford Synchrotron Radiation Lightsource through the data collection control software Blu-Ice24 and a crystal mounting robot. Raw data frames were indexed, integrated, and scaled using HKL2000.25 The binding of inhibitors was detected by the initial difference Fourier maps calculated with REFMAC.26 The inhibitor molecules were then modeled in COOT27 and refined using REFMAC. Water molecules were added in REFMAC and checked by COOT. The TLS28 protocol was implemented in the final stage of refinements with each subunit as one TLS group. The omit Fo – Fc density maps were calculated by repeating the last round of TLS refinement with inhibitor coordinate removed from the input PDB file to generate the coefficients DELFWT and SIGDELFWT. The refined structures were validated in COOT before deposition in the RCSB protein data bank. The crystallographic data collection and structure refinement statistics are summarized in Table 2 with PDB accession codes included.

Table 2.

Crystallographic data collection and refinement statistics.

| Data set a | nNOS-4 | nNOS-5 | nNOS-6 | nNOS-7 | eNOS-7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||||

| PDB code | 4IMS | 4IMT | 4IMU | 4IMW | 4IMX |

| Space group | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 | P212121 |

| Cell dimensions | |||||

| a, b, c (Å) | 51.8 110.4 164.1 | 51.7 110.7 163.7 | 51.9 110.2 163.9 | 51.7 111.4 164.2 | 58.1 106.6 156.5 |

| Resolution (Å) | 2.15 (2.19–2.15) | 2.20 (2.24–2.20) | 2.03 (2.07–2.03) | 2.15 (2.19–2.15) | 2.25 (2.29–2.25) |

| Rsym or Rmerge | 0.093 (0.632) | 0.073 (0.723) | 0.067 (0.618) | 0.075 (0.674) | 0.063 (0.653) |

| I / σI | 18.0 (2.0) | 19.6 (1.8) | 21.8 (2.0) | 23.4 (2.2) | 21.7 (2.2) |

| No. unique reflections | 52,114 | 48,484 | 60,761 | 52,331 | 46,588 |

| Completeness (%) | 99.5 (99.8) | 99.6 (98.5) | 99.0 (96.5) | 99.6 (99.8) | 99.6 (99.8) |

| Redundancy | 3.5 (3.6) | 4.0 (3.9) | 3.6 (3.4) | 4.6 (4.5) | 3.6 (3.7) |

| Refinement | |||||

| Resolution (Å) | 2.15 | 2.20 | 2.03 | 2.20 | 2.25 |

| No. reflections used | 49,363 | 45,951 | 57,686 | 46,313 | 44,205 |

| Rwork / Rfree b | 0.183/0.235 | 0.199/0.248 | 0.184/0.225 | 0.213/0.273 | 0.176/0.222 |

| No. atoms | |||||

| Protein | 6679 | 6674 | 6682 | 6659 | 6446 |

| Ligand/ion | 163 | 189 | 193 | 185 | 211 |

| Water | 244 | 162 | 350 | 158 | 249 |

| R.m.s. deviations | |||||

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.012 | 0.013 | 0.011 | 0.016 | 0.015 |

| Bond angles (deg) | 2.05 | 2.08 | 1.97 | 1.56 | 1.47 |

See Fig. 3 for the inhibitor chemical formula.

Rfree was calculated with the 5% of reflections set aside throughout the refinement. The set of reflections for the Rfree calculation were kept the same for all data sets of each isoform according to those used in the data of the starting model.

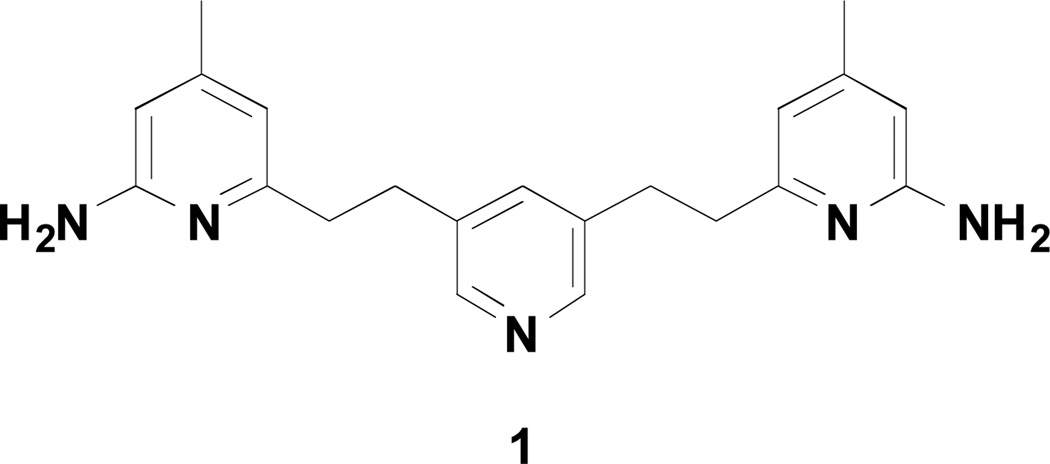

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of 1

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of 6 and 7a

a Reagents and conditions: (a) CuCN, DMF, 180°C, 8 h, 84%; (b) NBS, BPO, CCl4, 80 °C, 6 h, 22%; (c) n-BuLi, THF, −78 °C to rt, 2 h, 48%; (d) NH2OH·HCl, EtOH/H2O (2:1), 100 °C, 24 h, 31%; (e) LiBH4, TMSCl, THF, rt, 12 h, 42%.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for financial support from the National Institutes of Health (GM049725 to RBS and GM057353 to TLP). We thank Dr. Bettie Sue Siler Masters (NIH grant GM52419, with whose laboratory P.M. and L.J.R. are affiliated). B.S.S.M. also acknowledges the Welch Foundation for a Robert A. Welch Distinguished Professorship in Chemistry (AQ0012). P.M. is supported by grants 0021620806 and 1M0520 from MSMT of the Czech Republic. We also thank the beamline staff at SSRL and ALS for their assistance during the remote X-ray diffraction data collections.

Abbreviations

- NOS

nitric oxide synthase

- nNOS

neuronal nitric oxide synthase

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- H4B

(6R)-5,6,7,8-tetrahydro-L-biopterin

- NO

nitric oxide

- NADPH

reduced nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide phosphate

- CNS

central nervous system

- Ph3P

triphenylphospine

- BINAP

2,2'-bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,1'-binaphthyl

- DIAD

diisopropyl azodicarboxylate

- TMSCl

Trimethylsilyl chloride

- DIEA

N,N-Diisopropylethylamine

- DMF

dimethylformamide

Footnotes

Ancillary Information

The coordinates for the five crystal structures reported in this paper have been deposited with RCSB, which will be immediately released upon publication. The PDB entry codes for crystal structures reported in this work are: nNOS-4, 4IMS; nNOS-5, 4IMT; nNOS-6, 4IMU; nNOS-7, 4IMW; eNOS-7, 4IMX.

References

- 1.Vallance P, Leiper J. Blocking NO synthesis: How, where and why? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2002;1:939–950. doi: 10.1038/nrd960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alderton WK, Cooper CE, Knowles RG. Nitric oxide synthases: Structure, function and inhibition. Biochem. J. 2001;357:593–615. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3570593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rosen GM, Tsai P, Pou S. Mechanism of free-radical generation by nitric oxide synthase. Chem Rev. 2002;102:1191–1199. doi: 10.1021/cr010187s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Granik VG, Grigor'ev NA. Nitric oxide synthase inhibitors: Biology and chemistry. Russ. Chem. Bull. 2002;51:1973–1995. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olesen J. Nitric oxide-related drug targets in headache. Neurotherapeutics. 2010;7:183–190. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2010.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Reif DW, McCarthy DJ, Cregan E, MacDonald JE. Discovery and development of neuronal nitric oxide synthase inhibitors. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000;28:1470–1477. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00250-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Villanueva C, Giulivi C. Subcellular and cellular locations of nitric oxide synthase isoforms as determinants of health and disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2010;49:307–316. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.04.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Aquilano K, Baldelli S, Rotilio G, Ciriolo MR. Role of nitric oxide synthases in Parkinson's disease: A review on the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activity of polyphenols. Neurochem. Res. 2008;33:2416–2426. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9697-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Silverman RB. Design of selective neuronal nitric oxide synthase inhibitors. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:439–451. doi: 10.1021/ar800201v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maddaford S, Annedi SC, Ramnauth J, Rakhit S. Advancements in the development of nitric oxide synthase inhibitors. Annu. Rep. Med. Chem. 2009;44:27–50. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Oess S, Icking A, Fulton D, Govers R, Muller-Esterl W. Subcellular targeting and trafficking of nitric oxide synthases. Biochem. J. 2006;396:401–409. doi: 10.1042/BJ20060321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Annedi SC, Ramnauth J, Maddaford SP, Renton P, Rakhit S, Mladenova G, Dove P, Silverman S, Andrews JS, Felice MD, Porreca F. Discovery of cis-N-(1-(4-(methylamino)cyclohexyl)indolin-6-yl)thiophene-2-carboximidamide: A 1,6-disubstituted indoline derivative as a highly selective inhibitor of human neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) without any cardiovascular liabilities. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:943–955. doi: 10.1021/jm201564u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ramnauth J, Renton P, Dove P, Annedi SC, Speed J, Silverman S, Mladenova G, Maddaford SP, Zinghini S, Rakhit S, Andrews J, Lee DK, Zhang D, Porreca F. 1,2,3,4-Tetrahydroquinoline-based selective human neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) inhibitors: Lead optimization studies resulting in the identification of N-(1-(2-(methylamino)ethyl)-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroquinolin-6-yl)thiophene-2-carboximi damide as a preclinical development candidate. J. Med. Chem. 2012;55:2882–2893. doi: 10.1021/jm3000449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ji H, Delker SL, Li H, Martasek P, Roman LJ, Poulos TL, Silverman RB. Exploration of the active site of neuronal nitric oxide synthase by the design and synthesis of pyrrolidinomethyl 2-aminopyridine derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 2010;53:7804–7824. doi: 10.1021/jm100947x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Huang H, Ji H, Li H, Jing Q, Jansen Labby K, Martasek P, Roman LJ, Poulos TL, Silverman RB. Selective monocationic inhibitors of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. Binding mode insights from molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:11559–11572. doi: 10.1021/ja302269r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Xue F, Fang J, Delker SL, Li H, Martasek P, Roman LJ, Poulos TL, Silverman RB. Symmetric double-headed aminopyridines, a novel strategy for potent and membrane-permeable inhibitors of neuronal nitric oxide synthase. J. Med. Chem. 2011;54:2039–2048. doi: 10.1021/jm101071n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, Huang H, Zhang X, Luo X, Lin L, Jiang H, Ding J, Chen K, Liu H. Discovering novel 3-nitroquinolines as a new class of anticancer agents. Acta Pharmacol. Sin. 2008;29:1529. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2008.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hevel JM, White KA, Marletta MA. Purification of the inducible murine macrophage nitric oxide synthase. Identification as a flavoprotein. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:22789–22791. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roman LJ, Sheta EA, Martasek P, Gross SS, Liu Q, Masters BSS. High-level expression of functional rat neuronal nitric oxide synthase in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1995;92:8428–8432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.18.8428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martasek P, Liu Q, Liu JW, Roman LJ, Gross SS, Sessa WC, Masters BSS. Characterization of Bovine Endothelial Nitric Oxide Synthase Expressed in E. coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1996;219:359–365. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hevel JM, Marletta MA. Nitric-oxide synthase assays. Oxygen Radicals in Biological Systems, Pt C. 1994;233:250–258. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)33028-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li H, Shimizu H, Flinspach M, Jamal J, Yang W, Xian M, Cai T, Wen EZ, Jia Q, Wang PG, Poulos TL. The Novel Binding Mode of N-Alkyl-N‘-hydroxyguanidine to Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase Provides Mechanistic Insights into NO Biosynthesis. Biochemistry. 2002;41:13868–13875. doi: 10.1021/bi020417c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flinspach ML, Li H, Jamal J, Yang W, Huang H, Hah JM, Gomez-Vidal JA, Litzinger EA, Silverman RB, Poulos TL. Structural Basis for Dipeptide Amide Isoform-Selective Inhibition of Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004;11:54–59. doi: 10.1038/nsmb704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McPhillips TM, McPhillips SE, Chiu HJ, Cohen AE, Deacon AM, Ellis PJ, Garman E, Gonzalez A, Sauter NK, Phizackerley RP, Soltis SM, Kuhn P. Blu-Ice and the Distributed Control System: Software for Data Acquisition and Instrument Control at Macromolecular Crystallography Beamlines. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2002;9:401–406. doi: 10.1107/s0909049502015170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Otwinowski Z, Minor W. Processing of X-ray Diffraction Data Collected in Oscillation Mode. Methods Enzymol. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murshudov GN, Vagin AA, Dodson EJ. Refinement of Macromolecular Structures by the Maximum-Likelihood Method. Acta Crystallogr. 1997;D53:240–255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444996012255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. 2004;D60:2126–2132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winn MD, Isupov MN, Murshudov GN. Use of TLS Parameters to Model Anisotropic Displacements in Macromolecular Refinement. Acta Crystallogr. 2001;D57:122–133. doi: 10.1107/s0907444900014736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]