Abstract

Background and Purpose

Ectonucleotidases control extracellular nucleotide levels and consequently, their (patho)physiological responses. Among these enzymes, nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1 (NTPDase1), −2, −3 and −8 are the major ectonucleotidases responsible for nucleotide hydrolysis at the cell surface under physiological conditions, and NTPDase1 is predominantly located at the surface of vascular endothelial cells and leukocytes. Efficacious inhibitors of NTPDase1 are required to modulate responses induced by nucleotides in a number of pathological situations such as thrombosis, inflammation and cancer.

Experimental Approach

Here, we present the synthesis and enzymatic characterization of five 8-BuS-adenine nucleotide derivatives as potent and selective inhibitors of NTPDase1.

Key Results

The compounds 8-BuS-AMP, 8-BuS-ADP and 8-BuS-ATP inhibit recombinant human and mouse NTPDase1 by mixed type inhibition, predominantly competitive with Ki values <1 μM. In contrast to 8-BuS-ATP which could be hydrolyzed by other NTPDases, the other BuS derivatives were resistant to hydrolysis by either NTPDase1, −2, −3 or −8. 8-BuS-AMP and 8-BuS-ADP were the most potent and selective inhibitors of NTPDase1 expressed in human umbilical vein endothelial cells as well as in situ in human and mouse tissues. As expected, as a result of their inhibition of recombinant human NTPDase1, 8-BuS-AMP and 8-BuS-ADP impaired the ability of this enzyme to block platelet aggregation. Importantly, neither of these two inhibitors triggered platelet aggregation nor prevented ADP-induced platelet aggregation, in support of their inactivity towards P2Y1 and P2Y12 receptors.

Conclusions and Implications

The 8-BuS-AMP and 8-BuS-ADP have therefore potential to serve as drugs for the treatment of pathologies regulated by NTPDase1.

Keywords: ectonucleotidase, ectoATPase, adenine nucleotide analogue, inhibitors, ATP, ADP

Introduction

Extracellular nucleotides modulate a variety of functions, including development (Zimmermann, 2001), platelet aggregation (Stafford et al., 2003), pain perception (Burnstock, 2006a; Zylka, 2011), cardiovascular regulation (Erlinge and Burnstock, 2008), airway epithelial transport (Fausther et al., 2010), control of endocrine gland secretion (Stojilkovic and Koshimizu, 2001), neurotransmission and neuromodulation (Burnstock, 2007), inflammation as well as immune reactions (Atkinson et al., 2006; Robson et al., 2006; Borsellino et al., 2007). The effects of these nucleotides are mediated by the activation of several receptors, namely P2X1-7, P2Y1,2,4,6,11–14, and perhaps also cysLT1R, cysLT2R and/or GPR17 (Ciana et al., 2006; Burnstock, 2006b). Three enzyme families have the ability to hydrolyze ATP and ADP at the medium/membrane interface (Zimmermann, ; Robson et al., 2006; Zimmermann et al., 2012), thus keeping free nucleotides at a low extracellular concentration, namely the ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (E-NTPDase) family, the ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase (E-NPP) family (Goding et al., 2003) and non-specific alkaline phosphatases (Picher et al., 2003). The eight members of the E-NTPDase family include four true ectonucleotidases, namely NTPDase1 (also known as CD39, ATPDase, ecto-apyrase, ecto-ADPase), NTPDase2 (ecto-ATPase, CD39L1), NTPDase3 (CD39L3, HB6), and NTPDase8 (Bigonnesse et al., 2004; Kukulski et al., 2011b). The latter ectonucleotidases represent the main enzymes responsible for the hydrolysis of nucleotides in the cellular environment at physiological pH. These subtypes have two plasma membrane-spanning domains and an active site facing the extracellular milieu. These enzymes hydrolyze the γ- and β-phosphates of nucleotides in the presence of divalent cations (Ca2+ or Mg2+) (Kukulski et al., 2005).

NTPDase1 is the main ectonucleotidase in both vascular endothelial and smooth muscle cells, as well as in blood cells that regulate associated biological responses. NTPDase1 has been shown so far to be involved in acute immune responses (Deaglio and Robson, 2011; Kukulski et al., 2011b) and leukocyte migration (Kukulski et al., 2011a), to contribute to the antithrombotic property of endothelial cells (Marcus et al., 1991; Kaczmarek et al., 1996; Enjyoji et al., 1999) and to modulate angiogenesis, vascular permeability (Guckelberger et al., 2004; Yegutkin et al., 2011), and vasoconstriction (Kauffenstein et al., 2010; Li et al., 2011). Also of interest, NTPDase1 expression in sinusoidal endothelial cells from mice livers stimulates tumour cell proliferation and limits cell death triggered by extracellular ATP (Feng et al., 2011). NTPDase1-specific inhibitors would be extremely useful for elucidating the physiological roles of this enzyme and might also be assessed as promising drug candidates for the treatment of some cardiovascular diseases (Sévigny et al., 2002; Marcus et al., 2003; Atkinson et al., 2006; Robson et al., 2006), immune diseases (Borsellino et al., 2007; Moncrieffe et al., 2010) and cancer (Müller et al., 2006; Mandapathil et al., 2009). Therefore, NTPDase1 inhibitors may be valuable to potentiate the effect of P2 receptor agonists present in the vicinity of NTPDase1 by extending the half-life of their ligands.

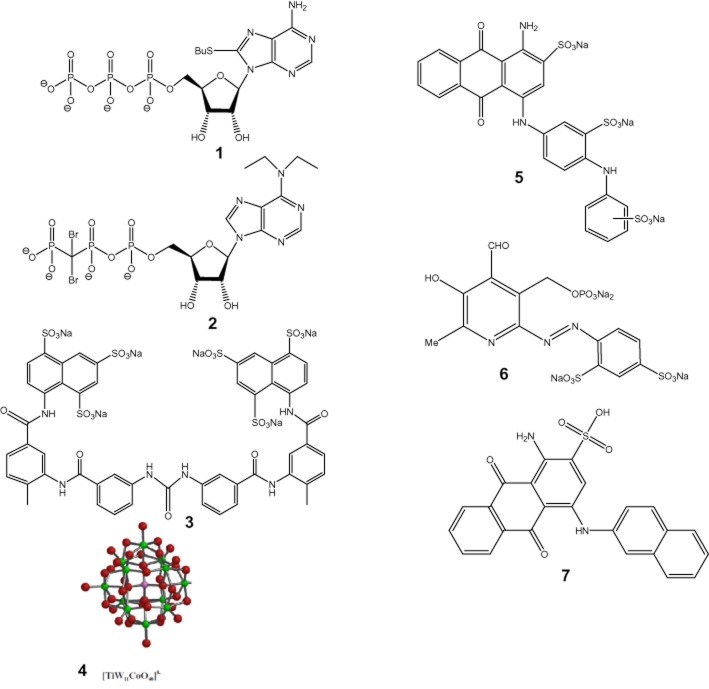

No specific inhibitors of NTPDase1 have yet been reported to this day. The only NTPDase inhibitors known so far are ATP analogues [8-BuS-ATP, 1 (Gendron et al., 2000) and N6,N6-diethyl-D-β-γ-dibromomethylene-ATP (ARL 67156), 2 (Crack et al., 1995; Lévesque et al., 2007)], suramin, 3 and related compounds, polyoxometalates (POM-1), 4 (Müller et al., 2006), sulfonate dyes such as reactive blue 2, 5 and pyridoxal phosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid (PPADS), 6 (Bultmann et al., 1996; Chen et al., 1996; Munkonda et al., 2007; Wittenburg et al., 1996) (Figure 1). We have developed 8-BuS-ATP a decade ago as the first potent NTPDase inhibitor (Ki ∼10 μM) (Gendron et al., 2000), but its subtype selectivity had not been determined thus far. ARL 67156 was found to be a weak and non-selective NPP1, NTPDase1 and NTPDase3 inhibitor. POM-1 is more effective than ARL 67156 at blocking NTPDase1-dependent ATP breakdown but its usefulness is limited by off-target actions on synaptic transmission (Lévesque et al., 2007; Wall et al., 2008). More recently, anthraquinone derivatives have been tested as NTPDase inhibitors. 1-Amino-2-sulfo-4-(2-naphthylamino) anthraquinone, 7 (Figure 1) was shown to be a potent inhibitor of NTPDase1 and NTPDase3 (Ki of 0.33 and 2.22 μM, respectively) (Baqi et al., 2009). Interestingly, monoclonal antibodies have been obtained that specifically inhibit human NTPDase3 (Munkonda et al., 2009) and NTPDase2 (http://ectonucleotidases-ab.com) but to our knowledge, no inhibitory antibody to NTPDase1 has yet been reported thus far.

Figure 1.

NTPDase inhibitors: (1), 8-BuS-ATP; (2), N6,N6-diethyl-D-β-γ-dibromomethylene-ATP (ARL 67156); (3), suramin; (4), polyoxometalates (POM-1); (5), reactive blue 2; (6), pyridoxal phosphate-6-azophenyl-2′,4′-disulfonic acid (PPADS); (7), 1-amino-2-sulfo-4-(2-naphthylamino)anthraquinone.

The need for potent and subtype-specific NTPDase inhibitors prompted us to perform a structure-activity relationship study using the natural substrate ATP. For this purpose, we synthesized and evaluated a series of 8-BuS-ATP analogues, 8–11, towards more stable and specific inhibitors of NTPDase1.

Methods

Enzymatic assays

Materials

Aprotinin, nucleotides, PMSF and Malachite green were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Oakville, ON, Canada). Tris was obtained from VWR (Montreal, QC, Canada). DMEM was obtained from Invitrogen (Burlington, ON, Canada). FBS and antibiotics-antimycotics solution were from Wisent (St-Bruno, QC, Canada). 8-Thiobutyladenosine 5′-triphosphate (8-BuS-ATP) was synthesized as previously described (Gendron et al., 2000).

Plasmids

Plasmids used in this study have all been described previously: human NTPDase1 (GenBank accession no. U87967) (Kaczmarek et al., 1996), human NTPDase2 (NM_203468) (Knowles and Chiang, 2003), human NTPDase3 (AF034840) (Smith and Kirley, 1998), human NTPDase8 (AY430414) (Fausther et al., 2007), human NPP1 (NM_006208) (Belli and Goding, 1994) and human NPP3 (NM_005021) (Jinhua et al., 1997).

Cell transfection and protein preparation

COS-7 cells (in 10 or 15 cm dishes) were transfected with an expression vector (pcDNA3) incorporating the cDNA that encodes each ectonucleotidase using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen) and harvested 40–72 h later, as described (Kukulski et al., 2005). For the preparation of protein extracts, transfected cells were washed three times with 95 mM NaCl and 45 mM Tris, pH 7.5, at 4°C, collected by scraping using the same buffer supplemented with 0.1 mM PMSF and washed twice by centrifugation (300× g, 10 min, 4°C). The cells were then resuspended in harvesting buffer supplemented with 10 μg ml−1 aprotinin and sonicated. Nucleus and cellular debris were discarded after another centrifugation (300× g, 10 min, 4°C) and the resulting supernatant (hereinafter called protein extract) was aliquoted and stored at −80°C until use. Protein concentration was estimated by a Bradford microplate assay using bovine serum albumin as a standard (Bradford, 1976).

Enzymatic reactions

Experiments were carried out with protein extracts of COS-7 cells transfected with an expression vector encoding each ectonucleotidase (1–2 μg proteins per assays in 200 μL reaction buffer), or with intact human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs), which express NTPDase1. Protein extracts from non-transfected COS-7 cells showed negligible ATPase and ADPase activities, representing less than 5 and 1%, respectively, of those found in extracts from COS-7 cells transfected with NTPDase1.

NTPDases (EC 3.6.1.5): Enzyme activity was measured as described (Kukulski et al., 2005) in 0.2 mL of incubation medium (5 mM CaCl2 and 80 mM Tris, pH 7.4) or Tris-Ringer buffer (in mM: 120 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgSO4, 25 NaHCO3, 5 d-glucose, 80 Tris, pH 7.4) at 37°C ± 8-BuS analogues. NTPDase protein extracts were added to the incubation mixture and pre-incubated at 37°C for 3 min. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 10–100 μM ATP and stopped after 10–15 min with 50 μL of Malachite green reagent. Membrane-bound activity was measured with confluent HUVECs at passage two attached to 24-well plates (about 200 000 cells per well). Cells were maintained in endothelial cell growth (EGM) medium supplemented with 10% FBS until the activity assay that was performed in the buffers indicated above supplemented with 125 mM NaCl. The reactions were initiated as above and stopped by transferring an aliquot of the reaction mixture to a tube containing the Malachite green reagent. Net cell-bound enzyme activity was calculated after subtracting the value measured in the control cell reaction mixture where the substrate was added after the Malachite green reagent. Released inorganic phosphate (Pi) was measured at 630 nm according to Baykov et al., (1988). All experiments were performed in triplicate. Note that the presence of 100 μM 8-BuS-ATP, 1, 8-BuS-AMP, 10, or 8-BuS-ADP, 11, did not affect the linearity of the Pi determination up to 40 μM (data not shown) which was accordingly never exceeded in the assays. One unit of enzymatic activity corresponds to the release of 1 μmol Pi·(min·mg of protein)−1 or 1 μmol Pi min−1·well−1 at 37°C for protein extracts and intact cells, respectively. The IC50 parameters were determined from a dose-response non-linear regression analysis. The Ki,app for 8-BuS-AMP, 10 and 8-BuS-ADP, 11, was performed according to Dixon and Cornish-Bowden method (Dixon, 1953; Cornish-Bowden, 1974) and the Ki,app for 8-BuS-ATP was calculated from its IC50 using the Cheng-Prusoff equation. All kinetic values were calculated using the GraphPad Prism software (GraphPad Software Inc. San Diego, CA, USA).

Note that for all NTPDases, the reaction was linear for at least the first 30 min with either ATP or ADP as a substrate. Therefore, all enzymatic assays in this work were carried out for 10–15 min.

NPPs (EC 3.1.4.1; EC 3.6.1.9): Evaluation of the effect of analogues 1 and 8–11 on human NPP1 and NPP3 activity was carried out with p-nitrophenyl thymidine 5′-monophosphate (pnp-TMP) as substrate (Belli and Goding, 1994; Vollmayer et al., 2003). Reactions were carried out at 37°C in 0.2 mL of the incubation mixture (in mM: 1 CaCl2, 140 NaCl, 5 KCl and 50 Tris, pH 8.5, ±test analogues). Substrates and inhibitors were all used at a final concentration of 100 μM. Human NPP1 or NPP3 extract was added to the incubation mixture and pre-incubated at 37°C for 3 min. The reaction was initiated by addition of the substrate. For pnp-TMP, the production of p-nitrophenol was measured at 405 nm, 15 min after initiation of the reaction.

Enzyme histochemistry assays: For histochemical studies, freshly dissected tissues were embedded in O.C.T. freezing medium (Tissue-Tek®; Sakura Finetk, Torrance, CA, USA) and snap-frozen in isopentane in dry ice and stored at −80°C until use. Sections of 6 μm were obtained and fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin mixed with cold acetone (Fisher Scientific, Ottawa, ON, Canada).

Localization of ectonucleotidase activities was determined using the Wachstein/Meisel lead phosphate method (Braun et al., 2003). Fixed slices were pre-incubated for 30 min at room temperature (RT) in 50 mM Tris-maleate buffer, pH 7.4, containing 2 mM CaCl2, 250 mM sucrose and 2.5 mM levamisole as an inhibitor of alkaline phosphatases. Enzymatic reaction was performed for 1 h at 37°C in the same buffer supplemented with 5 mM MnCl2 to inhibit intracellular staining (Dahl and Pratley, 1967), 2 mM Pb(NO3)2, 3% Dextran T-250 and in the presence of 200–500 μM ATP with or without 8-BuS derivatives. For control experiments, substrate was either omitted or added in the absence of divalent cations, which are essential for NTPDase activity. The reaction was revealed by incubation with 1% (NH4)2S v/v for exactly 1 min. Samples were counterstained with aqueous haematoxylin or DAPI, mounted with Mowiol mounting medium, and observed and photographed under a BX51 Olympus microscope.

Platelet aggregation assays

The investigation standards conformed to principles outlined in the Helsinki declaration. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was prepared from the blood of healthy volunteers according to standard procedures (Sévigny et al., 2002). Briefly, whole blood was collected in heparinized tubes, centrifuged at room temperature at 300× g for 12 min and the upper layer, consisting of the platelet-rich plasma (PRP) fraction, was collected. Platelets were used from 1.5 to 2 h after collection from the volunteers. Platelet aggregation was measured in an AggRAM aggregometer. The extent of platelet aggregation corresponded to the decrease in OD600 observed with a 0.6 mL PRP sample maintained at 37°C. PPP, obtained after centrifugation of the PRP for 3 min at 15 000× g, was used as the control of reference. Platelet aggregation was initiated with the addition of 8 μM ADP. Where indicated, NTPDase1-transfected COS-7 cell lysates (6 μg protein diluted in incubation buffer A with 145 mM NaCl) with or without test drugs, were added to PRP. Note that appropriate control experiments contained either incubation buffer with intact COS-7 cells, protein extracts from non-transfected COS-7 cells, or an equivalent amount of water as a control for the tested compounds as they were all diluted in water.

For parallel assays using light microscopy, 100 μL of the above reaction mixture was placed on microscope slides 10 min after initiation of platelet aggregation. Slides were then air-dried at 37°C and stained using Diff-Quick kit (Dade Behring Inc., Newark, DE, USA). The remainder of the reaction mixture was spun at 300× g for 3 min, and free platelets in the supernatant were counted.

Nucleotide synthesis

General

All air- and moisture-sensitive reactions were carried out in flame-dried, argon-flushed, two-necked flasks sealed with rubber septa, and reagents were introduced with a syringe. TLC analysis was performed on pre-coated Merck silica gel plates (60F-254). Visualization was accomplished using a UV light. Nucleosides were separated on a medium pressure liquid chromatography system (Biotage, Uppsala, Sweden) using a silica gel column (12+ M or 25+ M); separation conditions are indicated below for each compound. New compounds were characterized (and resonances assigned) by NMR using Bruker DMX-600, DPX-300, or AC-200 spectrometers. Nucleoside 1H NMR spectra were recorded in CD3OD or in D2O, and the chemical shifts are reported in ppm relative to HDO (4.78 ppm) as an internal standard. Nucleotides were characterized also by 31P NMR in D2O with an AC-200 spectrometer at pH 8, using 85% H3PO4 as an external reference. All final products were characterized by chemical ionization and high-resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) using an AutoSpec-E Fision VG high-resolution mass spectrometer. Nucleotides were desorbed from a glycerol matrix by fast atom bombardment at low and high resolution. Primary purification of nucleotides was achieved on an LC system (Isco UA-6) using a DEAE Sephadex A-25 column that had been swelled in 1 M NaHCO3 at RT overnight. Final purification of nucleotides was achieved on a HPLC system (Hitachi) with a semipreparative reverse-phase (Gemini 5 μm C-18 110 Å, 250 × 10 mm, 5 μm; Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). For analytical purposes, a microcolumn (Gemini 5 μm, C-18 110 Å, 150 × 4.60 mm, 5 μm; Phenomenex) was used. The purity of the nucleotides was evaluated on an analytical column using two different solvent systems. Peaks were detected by UV absorption at 253 nm. Solvent system I was (A) CH3CN and (B) 0.1 M triethylammonium acetate (TEAA) (pH 7). Solvent system II was (A) 5 mM tetrabutylammonium phosphate (TBAP) in MeOH and (B) 60 mM ammonium phosphate and 5 mM TBAP in 90% water/10% MeOH.

8-Butylthio-adenosine (12) (Halbfinger et al., 1999) (100 mg, 0.28 mmol) was dissolved in dry trimethyl phosphate (724 μL), cooled to −15°C and a proton sponge (94 mg, 0.44 mmol, 1.6 eq) was added. After stirring for 20 min, phosphoryl chloride (POCl3) (76.7 μL, 0.36 mmol, 1.3 eq) was added dropwise and the reaction was stirred for 2 h. A 1 M solution of [Bu3NH+]2[CH2(PO3)2]2- in dimethylformamide (DMF; 2.1 mL, 2.1 mmol, 7.5 eq) and Bu3N (275 μL, 1.15 mmol, 4 eq) was added at once. After stirring for 1 min, triethylammonium bicarbonate buffer (pH 7) TEAB (5 mL, 0.2 M) was added and the clear solution was stirred for 45 min at RT. The latter solution was freeze-dried overnight. The semisolid obtained was then purified by chromatography on an activated DEAE Sephadex A-25 column using a NH4HCO3 gradient (0–0.48 M). The relevant fractions were freeze-dried repeatedly to yield the product 8 as a white solid in a 35% yield (58 mg). Final separation was achieved on HPLC applying a linear gradient of TEAA/CH3CN 80:20 to 55:45 in 12 min (flow rate, 6 mL min−1), with a measured retention time (tR) of 12 min (>95% purity) using solvent system II (60 mM ammonium phosphate (A) and 5 mM TBAP in 90% water/10% methanol (B), applying a gradient of 25% A to 75% A in 20 min), tR = 6 min (>97% purity). 1H NMR (D2O, 200 MHz) δ: 8.17 (s, 1H, H2), 6.12 (d, J = 7 Hz, 1H, H1′), 5.19 (t, J = 7 Hz, 1H, H2′), 4.64–4.55 (m, 1H, H3′), 4.40–4.14 (m, 3H, H4′, H5′, H5″), 3.60 (m, 2H, SCH2), 1.73 (m, 2H, SCH2CH2), 1.40 (m, 2H, SCH2CH2CH2), 0.90 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 3H, CH3) ppm; 31P NMR δ: −10.1 (d), −9.9 (d), – 0.2 (s) ppm; MS TOF ES-: 593 (M+H-); HRMS: calculated for C14H21N6O12P3S, 593.0173; found, 593.0163.

Tosylic acid (p-TsOH) (285 mg, 1.5 mmol) was added to dry 8-butylthioadenosine (12) (Halbfinger et al., 1999) (266.5 mg, 0.75 mmol) in a two-neck flask under Ar, followed by the addition of dry DMF (4 mL). 2,2-Dimethoxypropane (2.7 mL) was then added and the clear solution was stirred for 24 h at RT. Volatiles were evaporated and the residue was coevaporated at 40°C with EtOH. After separation on a silica gel column and upon elution with 30% ethyl acetate in ether, product 13 was obtained as a white solid in a 46% yield (100 mg). 1H NMR (D2O, 200 MHz) δ: 8.35 (s, 1H, H2), 6.22 (d, J = 4 Hz, 1H, H1′), 5.35 (t, J = 5 Hz, 1H, H2′), 5.14 (m, 1H, H3′), 4.32 (m, 1H, H4′), 3.90-3.62 (m, 2H, H5′, H5″), 3.42–3.20 (m, 2H, SCH2), 2.93 (s, 3H, CH3C), 2.80 (s, 3H, CH3C), 1.80–1.22 (m, 4H, SCH2CH2CH2CH3), 0.91 (t, J = 6 Hz, 3H, CH3) ppm; MS TOF ES+: 395 (M+H-). HRMS: calculated for C17H25N5O4S: 395.1627; found: 395.1635.

8-Butylthio-2′,3′-isopropylidene-adenosine (13) (100 mg, 0.25 mmol) was dissolved in dry trimethyl phosphate (1.5 mL), cooled to −15°C, and proton sponge was added (178.6 mg, 0.83 mmol, 3.3 eq). After stirring for 20 min, POCl3 (27.4 μL, 0.3 mmol, 1.2 eq) was added dropwise and the reaction was stirred for 2 h at −15°C. A 1 M solution of the bis(tributyl)ammonium salt of methylene diphosphonic acid in DMF (1.7 mL, 1.7 mmol, 6.8 eq) and Bu3N (170 μL, 0.7 mmol, 2.8 eq) were added at once. After stirring for 6 min at −15°C, 1 M TEAB (5 mL) was added and the clear solution was stirred for 45 min at RT. The latter was freeze-dried overnight. The semisolid obtained then purified by chromatography on an activated DEAE Sephadex A-25 column (diameter 1.6 cm and length 15 cm) using a two-step gradient of NH4HCO3 (400 mL for a 0–0.2 M gradient and then 700 mL for a 0.2–0.4 M gradient). The relevant fractions were freeze-dried repeatedly to generate the product 14 as a white solid in a 60% yield. This residue was used without further purification. 1H NMR (D2O, 200 MHz) δ: 8.40 (s, 1H, H2), 6.20 (d, J = 7 Hz, 1H, H1′), 5.61 (t, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, H2′), 5.25 (m, 1H, H3′), 4.20 (m, 1H, H4′), 3.40-3.20 (m, 2H, H5′, H5″), 2.4 (t, J = 14 Hz, 2H, SCH2), 1.90-1.40 (m, 10H, SCH2CH2CH2CH3, CH3C, CH3C), 1.0 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3H, CH3) ppm; 31P NMR (D2O, pH 8.5) δ: 18.0 (m), 10.0 (m), −10.1 (m) ppm; MS TOF ES-: 629 (M+H-).

8-Butylthio-2′,3′-isopropylidene-β,γ-methylene-triphosphate (14) (42 mg, 0.66 mmol) was dissolved in 2 mL of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA). The reaction was stirred at RT for 10 min. The volatiles were evaporated. The semisolid obtained was purified by chromatography on an activated DEAE Sephadex A-25 column using a two-step gradient of NH4HCO3 (700 mL for a 0–0.15 M gradient followed by 700 mL for a 0.15–0.3 M gradient). The relevant fractions were freeze-dried repeatedly to yield the product 9 as a white solid in a 70% yield (27.3 mg). Final separation was achieved on HPLC applying a linear gradient of TEAA/CH3CN 86:14 to 78:22 in 25 min (flow rate, 6 mL min−1), tR = 12.4 min (99.4% purity). Purity was also evaluated using a linear gradient of TEAA/CH3CN (80:20 to 55:45 in 15 min), with a tR = 4.3 min (98% purity) using a linear gradient of phosphate buffer/CH3CN (90:10 to 80:20; flow rate, 1 mL min−1). 1H NMR (D2O, 300 MHz) δ: 8.22 (s, 1H, H2), 6.15 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H, H1′), 5.23 (t, J = 6.5 Hz, 1H, H2′), 6.13 (m, 1H, H3′), 4.32 (m, 3H, H4′, H5′, H5″), 2.26 (m, 2H, SCH2), 1.74 (m, 2H, SCH2CH2), 1.50 (m, 2H, CH2CH3), 0.90 (t, J = 7 Hz, 3H, CH3) ppm; 31P NMR (D2O, 200 MHz, pH 8.5) δ: 15.0 (d), 9.0 (d), −10.1 (d) ppm; MS TOF ES-: 590 (M+H-); HRMS calcd. for C15H22N5O12P3S, 589.0199; found, 589.0220.

|

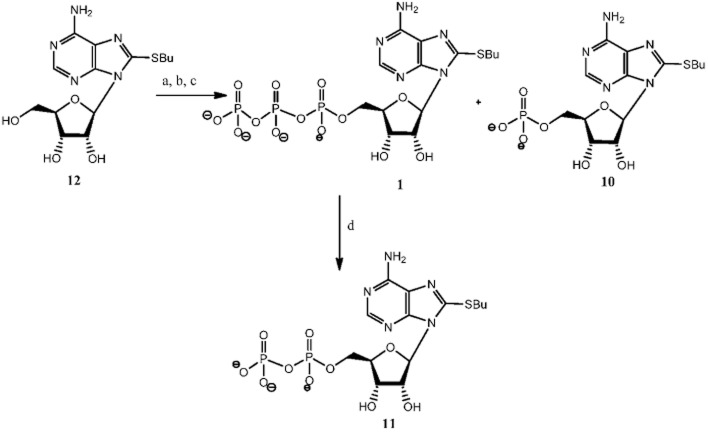

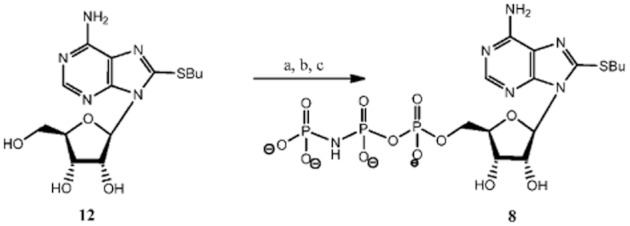

Compounds 1 and 12 were synthesized according to our previously published procedure (Halbfinger et al., 1999). Compound 10 was a by-product of the triphosphorylation of 8-BuS-adenosine (12) and finally, compound 11 was obtained as a result of hydrolysis upon prolonged incubation in water solution at RT of 8-BuS-ATP, 1 (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Synthesis of 8-BuS-AMP 10 and 8-BuS-ADP, 11. a Reagents and conditions: a, POCl3, proton sponge, −15°C, 2 h; b, [Bu3NH+]2[(P2O5)2]2−/NBu3,−10°C, 6 min; c, 1M TEAB, RT, 45 min, 50% overall yield for 1 and 35% for 10; d, H2O, 10 d, RT.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was done using Student's t-test. P-values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Rational design of potential NTPDase inhibitors

To study the structure-activity relationships of ATP analogues towards NTPDases and identify more potent and enzyme subtype-selective inhibitors we synthesized and evaluated a series of adenine nucleotide derivatives, analogues 8–11. Compound 1, 8-BuS-ATP, (Gendron et al., 2000) was reported previously as a potent NTPDase inhibitor. As we show in Table 1 the β, γ-phosphoester bond in 1 is susceptible to hydrolysis by NTPDases. Indeed NTPDase2, −3 and −8 hydrolyzed this compound and ATP with comparable efficacy (Table 1). To prevent hydrolysis of the terminal, β, γ-phosphoester bond, we introduced an imido (8) or a methylene (9) group in the phosphate chain of 8-BuS-ATP. We also generated derivatives with a shorter phosphate chain, namely 8-BuS-AMP (10) and 8-BuS-ADP (11).

Table 1.

Stability of analogues 1 and 8–11 to hydrolysis by human NTPDases

| Compound | NTPDase1 | NTPDase2 | NTPDase3 | NTPDase8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 ± 3 | 55 ± 13 | 36 ± 4 | 64 ± 18 |

| 8 | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 14 ± 1 |

| 9 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | ND | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 4.0 ± 0.2 |

| 10 | ND | ND | ND | 2.0 ± 0.1 |

| 11 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 3.0 ± 0.1 |

Each analogue was tested as a substrate for each NTPDase and was compared with the activity obtained with ATP which was set as 100% and which corresponds to 670 ± 35, 928 ± 55, 202 ± 37, and 129 ± 11 nmol Pi·min·mg protein−1 for NTPDase1, −2, −3 and −8, respectively. Results are expressed in % ±SD of three independent experiments, each performed in duplicate. ND, not detected.

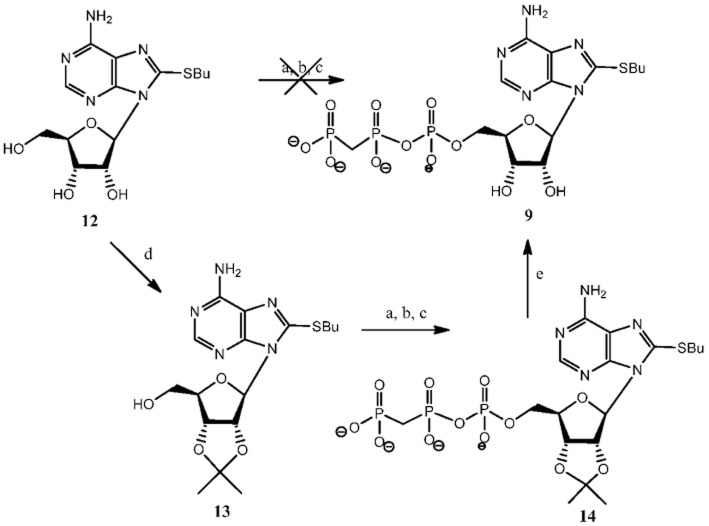

The 8-BuS-β,γ-imido-adenosine-5′-triphosphate analogue, 8, was prepared using imidodiphosphate instead of pyrophosphate in the second step of the Ludwig's 5′-triphosphorylation reaction (Figure 3) (Ludwig, 1981). Our attempt to synthesize 9 directly under 5′-triphosphorylation conditions using methylene diphosphonic acid instead of pyrophosphate resulted in a complex mixture of by-products, making the isolation of the desired product nearly impossible. Thus, we implemented a different strategy (Figure 4): we first protected 2′,3′- hydroxyl groups with an isopropylidene protective group, and then applied our triphosphorylation procedure (Gillerman and Fischer, 2010) with methylene diphosphonic acid. Compound 13, 8-butylthio-2′,3′-isopropylidene-adenosine, was obtained by treatment of 8-BuS-adenosine (12) (Halbfinger et al., 1999) with 2,2-dimethoxypropane in DMF in the presence of p-toluene sulphonic acid for 24 h at RT. In the next step, monophosphorylation with POCl3 at −15°C for 2 h and subsequent triphosphorylation using tetrabutylammonium methylene diphosphonic acid resulted in product 14. Thus, product 9 was obtained in a 60% yield, after deprotection of hydroxyl groups with TFA for 10 min at RT and liquid chromatographic separation.

Figure 3.

Synthesis of 8-BuS-AMP-PNP, 8a. a Reagents and conditions: a, POCl3, proton sponge, −15°C, 2 h; b, [Bu3NH+]2[NH(PO3)2]2−/NBu3,−10°C, 6 min; c, 1M TEAB, RT, 45 min, overall yield 35%.

Figure 4.

Synthesis of 8-BuS-AMP-PCP, 9. a Reagents and conditions: a, POCl3, proton sponge, −15°C, 2 h; b, [Bu3NH+]2[CH2 PO3)2]2−/NBu3,−10°C, 6 min; c, 1M TEAB, RT, 45 min; d, 2,2-dimethoxypropane, p-TsOH, DMF, RT, 24 h; e, TFA, RT, 10 min, 60% overall yield.

Influence of analogues 8–11 on ectonucleotidase activity

The low intrinsic nucleotidase activity found in control COS-7 cell extracts allowed the analysis of each ectonucleotidase in its native membrane-bound form. All tested compounds, substrates and inhibitors were tested at equimolar concentrations (100 μM) unless otherwise indicated.

First, we evaluated the stability of the analogues towards hydrolysis. While 8-BuS-ATP (1) was hydrolyzed quite well by human NTPDase2, −3 and −8 (Table 1), 8-BuS-β,γ-methylene-ATP (9) 8-BuS-AMP (10) and 8-BuS-ADP (11) were stable to hydrolysis by human NTPDase1-3 and −8. Analogue 8 was also resistant to hydrolysis by NTPDase1, −2 and −3 but could be modestly hydrolysed by NTPDase8 (Table 1).

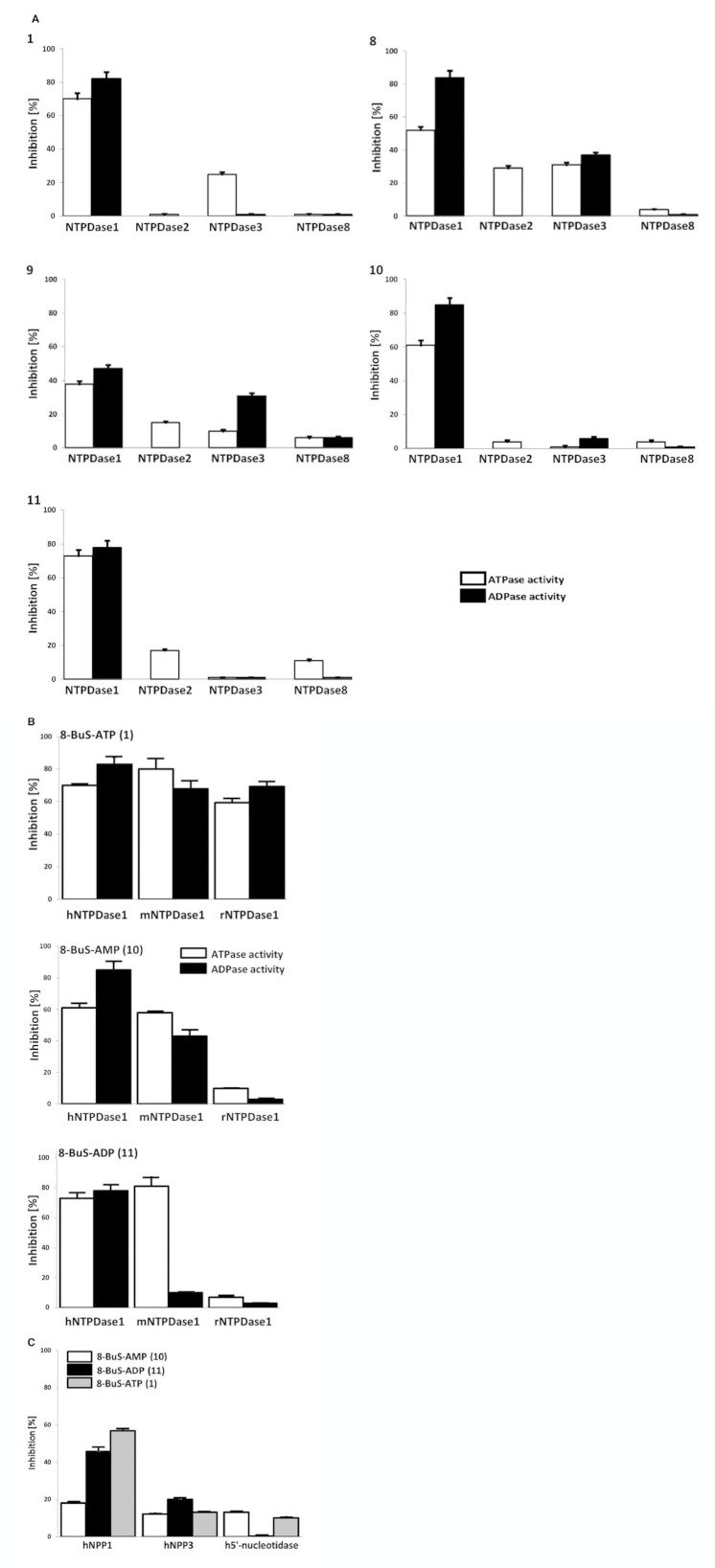

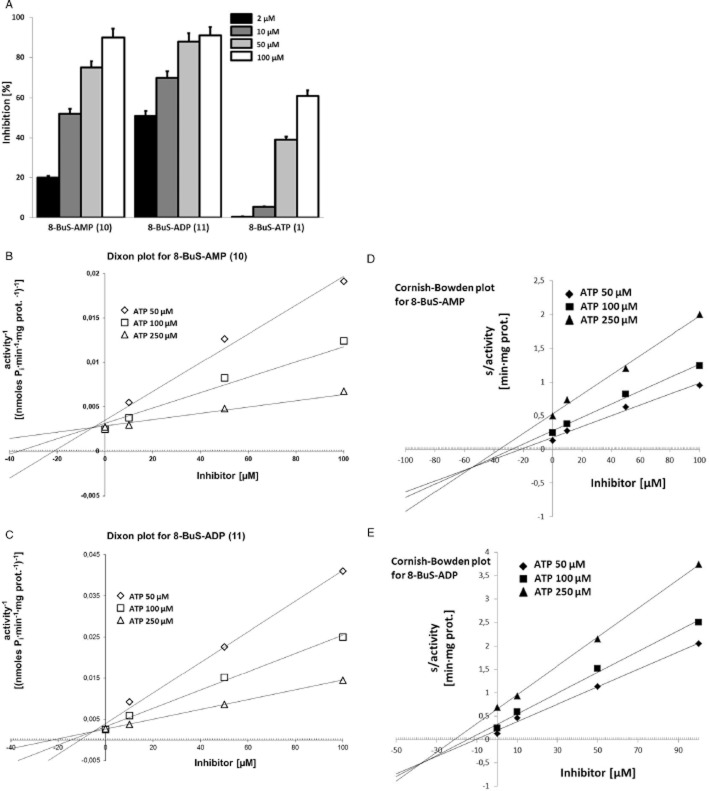

NTPDase1 ATPase activity was inhibited weakly (38–52%) and non-selectively by 8-BuS-ATP derivatives 8 and 9, whereas 1, 10 and 11 were strong inhibitors of NTPDase1 ATPase activity in an exclusive fashion (70, 61 and 73%, respectively) (Figure 5A). The ADPase activity of NTPDase1 was inhibited by these analogues in a manner similar to ATPase activity (Figure 5A). Increasing the pre-incubation time of 1 and 11 with human NTPDase1 for 2, 10 and 20 min did not improve the inhibition (data not shown) suggesting that this effect was rapid. The inhibition of NTPDase1 by 1, 10 and 11 was effective for human and mouse but not for rat NTPDase1 (Figure 5B). These compounds inhibited mouse NTPDase1 activity, with one exception, mouse NTPDase1 ADPase activity was not affected by 11 (Figure 5B). While molecule 11 was specific to mouse NTPDase1, as it did not affect the ATPase activity of mouse NTPDase2, −3 and −8, the activity of the later NTPDases were modestly inhibited by 1 and 10 (data not shown). As analogues 1, 10 and 11 significantly and specifically reduced the activity of human NTPDase1, we tested the kinetic parameters (Ki and IC50) of inhibition with ATP as substrate. The Kis (evaluated by Dixon plot for 10 and 11 (Figure 6), and Cheng-Prusoff equation for 1) were similar for these three analogues, which were in the order of 0.8–0.9 μM, while the IC50 values were in the 6–35 μM range, with the lowest value evaluated for 8-BuS-ATP (Table 2). The type of inhibition was evaluated for the best 2 compounds (10 and 11). Using both methods, Dixon (Figure 6B,C) and Cornish-Bowden (Figure 6D,E), we determined that our inhibitors present mixed type inhibition, predominantly competitive (Dixon, 1953; Cornish-Bowden, 1974).

Figure 5.

Influence of adenine nucleotide analogues 1 and 8–11 on recombinant ectonucleotidase activities. Enzymatic assays were carried out with protein extracts from COS-7 cells transfected with an expression vector encoding the respective enzyme. The substrate (ATP, ADP, AMP or pnp-TMP) was added together with each BuS derivative, both at 100 μM. The 8-BuS derivatives are indicated in the top left of each panel or in the legend. (A) The activity (without inhibitor) with the substrate ATP corresponded to 670 ± 35, 928 ± 55, 202 ± 37, and 129 ± 11 nmol Pi·min−1·mg protein−1 for human NTPDase1, −2, −3 and −8, respectively, and with ADP to 530 ± 22, 110 ± 10, and 30 ± 5 nmol Pi·min−1·mg protein−1 for NTPDase1, −3 and −8, respectively. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 experiments carried out in triplicate. (B) Comparative effect of 8-BuS-ATP (1; top panel), 8-BuS-AMP (10; middle panel) and 8-BuS-ADP (11; lower panel) on the ATPase and ADPase activities of human, mouse and rat NTPDase1. Relative activities are expressed as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. The activity with ATP without inhibitors was 670 ± 35, 990 ± 39 and 750 ± 32 nmol Pi·min−1·mg protein−1 for human, mouse and rat NTPDase1, respectively, and with ADP, 530 ± 22, 878 ± 35 and 690 ± 25 nmol Pi·min−1·mg protein−1 for human, mouse and rat NTPDase1, respectively. (C) Compounds 10 and 11 modestly affect NPP and ecto-5′-nucleotidase activities. The activity without inhibitors with pnp-TMP as substrate were 30 ± 2 and 61 ± 4 nmol p-nitrophenol min−1·mg protein for NPP1 and NPP3, respectively. The activity without inhibitors of ecto-5′-nucleotidase was 1.7 ± 0.1 μmoles Pi min−1·mg protein. Data are presented as the mean ± SD of 3 experiments carried out in triplicate.

Figure 6.

Concentration dependent inhibition (A) and Ki determination (B) of ATPase activity of human NTPDase1 by 8-BuS-AMP (10), 8-BuS-ADP (11) and 8-BuS-ATP (1). (A) The activity with 100 μM ATP without inhibitors was 650 ± 33 nmol Pi·min−1·mg protein−1. Ki determination for (B, D) 8-BuS-AMP (10) and (C, E) 8-BuS-ADP (11) by Dixon (B, C) and Cornish-Bowden (D, E) plot. ATP concentration range was 50, 100 and 250 μM, and the inhibitor's range was 0, 10, 50 and 100 μM. The data of one representative experiment out of 3 is shown.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters of 8-BuS-adenine nucleotide derivatives for human NTPDase1 inhibition

| 8-BuS-ATP (1) | 8-BuS-AMP (10) | 8-BuS-ADP (11) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IC50 [μM] | 5.6 ± 1.2 | 35 ± 2 | 28 ± 2 |

| Ki [μM] | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.2 |

Results are expressed as [μM] ± SEM of three independent experiments, each performed in duplicate.

We then tested the influence of the two most stable and potent inhibitors of NTPDase1, 8-BuS-AMP (10) and 8-BuS-ADP (11) on the activity of other ectonucleotidases, namely NPPs and ecto-5′-nucleotidase. Compound 11, 8-BuS-ADP, inhibited weakly (<50%) the activity of human NPP1 as measured with pnp-TMP (Figure 5C). These derivatives did not, or only modestly, inhibit human ecto-5′-nucleotidase (Figure 5C).

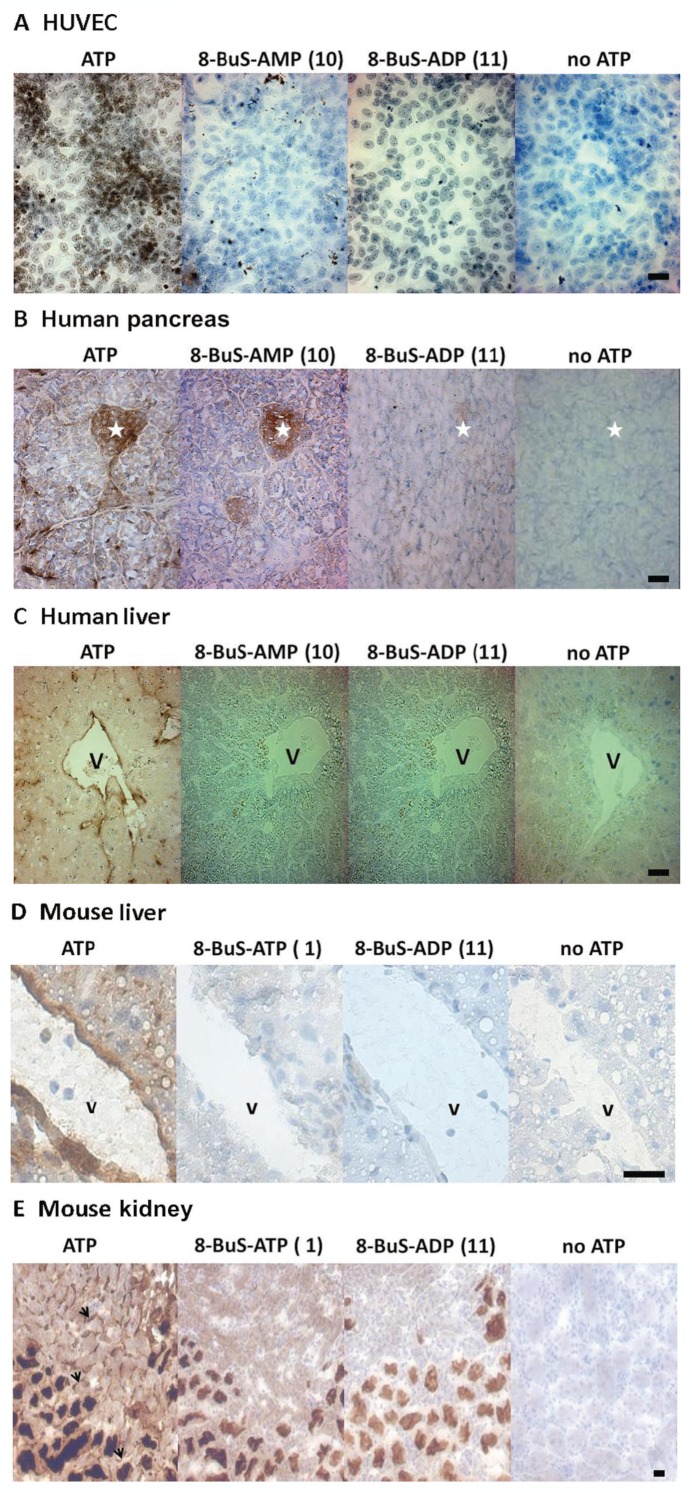

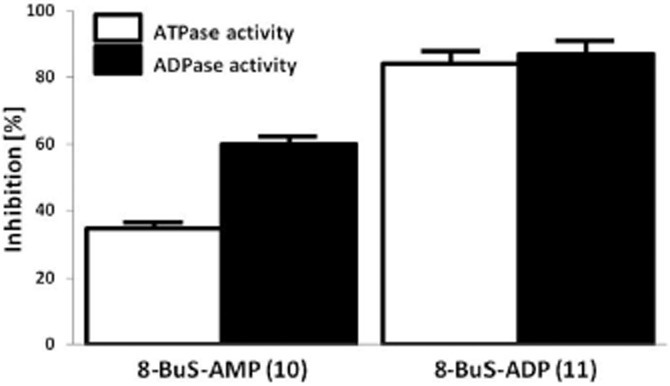

8-BuS derivatives inhibit NTPDase1 activity in tissues and cells

Endothelial cells express high levels of NTPDase1. Both analogues 10 and 11 inhibited the ATPase and ADPase activity of HUVEC cells, with 8-BuS-ADP reducing this activity by >80% (Figure 7) and 8-BuS-AMP by 35 and 60%, respectively (Figure 7). These results were confirmed by cytochemistry with HUVECs (Figure 8A). Analogues 10 and 11 also inhibited the ATPase activity of NTPDase1 in situ in human pancreas and liver (Figure 8B,C) which was mainly found in blood vessels and capillaries/sinusoïds. Importantly, analogue 10 showed strong specificity in histochemistry assays, exclusively inhibiting NTPDase1 activity in liver and pancreas tissues (Figure 8B,C). In mouse liver, pancreas and kidney analogues 1 and 11 also inhibited ATPase activity of NTPDase1 that is exhibited in vascular elements, arteries, veins and capillaries/sinusoïds (Figure 8D,E and data not shown). The ATPase activity due to NTPDase3 (Vekaria et al., 2006) and/or NTPDase8 (Sévigny et al., 2000) in kidney tubules remained (Figure 8E). This experiment showed the specificity of the inhibition by these molecules.

Figure 7.

Compounds 10 and 11 inhibit the ectonucleotidase activity of intact HUVECs. Hydrolysis of 100 μM ATP (open bars) and 100 μM ADP (solid bars) was evaluated in the presence of 100 μM 8-BuS-AMP (10) or 8-BuS-ADP (11). The activity without inhibitors were 2.25 ± 0.01 and 3.31 ± 0.02 nmol Pi·min−1·well−1 for ATP and ADP respectively. Activities are expressed as the mean ± SD of 3 independent experiments with confluent cells from different donors at passage 2, each performed in triplicate, mean cell number in one well was in the order of 250 000.

Figure 8.

Inhibition of ATPase activity in human and mouse cells and tissues by compounds 1, 10 and 11 using enzyme histochemistry. Substrate, ATP, was used at a final concentration of 200 and 500 μM for human and mouse, respectively, and inhibitors at 100 and 500 μM for human and mouse, respectively. (A) ATPase activity is present at the surface of HUVEC due to NTPDase1. (B) In pancreas, ATPase activity is seen as a brown precipitate in Langerhans islets cells due to NTPDase3, and in blood vessels, in the luminal membrane of acinar cells and in zymogen granules due to NTPDase1. (C) In the liver (D for mouse), ATPase activity due to NTPDase1 is present in vascular endothelium, central vein and sinusoids, as well as in Küpffer cells. Inhibition of ATPase activity in mouse liver (D) and kidney (E) by compounds 1 and 11 using enzyme histochemistry. ATPase activity due to NTPDase1 is seen as a brown precipitate in vascular elements, veins and capillaries, which is inhibited by 1 and 11. In contrast, the activity due to NTPDase3 and/or NTPDase8 in kidney tubules remains. Serial sections were used for all tissues. Nuclei were counterstained with Haematoxylin. Scale bar = 50 μm; * = Langerhans islet; V = vein; black arrows = capillaries.

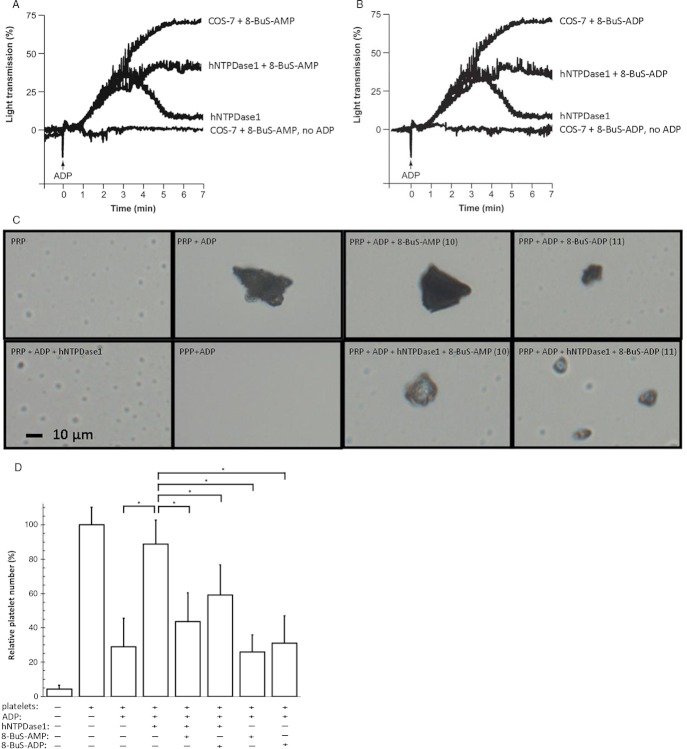

8-BuS-AMP and 8-BuS-ADP inhibit NTPDase1 function in platelet aggregation

We next estimated how the inhibition of NTPDase1 by 8-BuS-adenine nucleotide affects platelet aggregation using the recombinant enzyme. As expected, the inhibition of recombinant NTPDase1 by either 10 or 11 resulted in an impaired ability of this enzyme to prevent platelet aggregation (Figure 9A,B). These analogues did not per se initiate platelet aggregation (Figure 9A,B and data not shown), despite the fact that 8-BuS-ADP is an analogue of ADP that could in principle have activated P2Y1 and P2Y12 in platelets (Gachet, 2012).

Figure 9.

Compounds 10 and 11 inhibit recombinant human NTPDase1 and its ability to block platelet aggregation induced by ADP. Human NTPDase1 was obtained from a protein extract from transfected COS-7 cells (6 μg protein). Proteins from non-transfected COS-7 cells (6 μg) were used as controls. The controls with protein extract from non-transfected COS-7, with and without ADP, were similar to the assays with inhibitors. They were omitted for clarity. Platelet aggregation in the presence or absence of the indicated protein extract and nucleotide analogue was initiated with 8 μM ADP. (A) Platelet aggregation curves of one out of 3 representative experiments with 8-BuS-AMP are shown. (B) Platelet aggregation curves of one out of 3 representative experiments with 8-BuS-ADP are shown. (C) Qualitative assessment of the effect of 8-BuS-AMP (100 μM) and 8-BuS-ADP (100 μM) on platelet aggregation ± hNTPDase1, by light microscopy (40×). The reaction was performed for 10 min. Pictures of one out of 3 representative experiments are shown. The control without platelets is represented by platelet poor plasma (PPP) and with non-aggregated platelets by platelet-rich plasma (PRP). (D) Number of non-aggregated platelets after 10 min of reaction ± nucleotide analogues and hNTPDase1. The 100% value was set at 3.15 × 106 platelets in 1 mL. The significant statistical differences are indicated as *P < 1·10−3.

Light microscopy further confirmed the above observation with a more systematic quantification of these effects. This method showed that in the presence of 10 or 11, human NTPDase1 could not prevent the formation of platelet aggregates initiated by ADP (Figure 9C) and that the number of non-aggregated platelets in the mixture containing human NTPDase1 was reduced to levels observed in absence of the enzyme (Figure 9D).

Discussion

We previously reported 8-BuS-ATP (1) as the first inhibitor of bovine spleen NTPDase activity (Gendron et al., 2000). In the current study, we show that 8-BuS-ATP inhibits NTPDase1 (Figure 5A). Unfortunately, our data also show that this molecule is a substrate for human NTPDase2, −3 and −8 (Table 1), thus limiting the use of 8-BuS-ATP as an NTPDase1 inhibitor in situations where other ectonucleotidase are present. Therefore, we have synthesized four non-hydrolyzable 8-BuS-ATP analogues, 8–11, and tested their potential effect on NTPDase activity.

Two of the stable analogues, namely 8 and 9, decreased the activity of NTPDase1 (Table 1). However, the substitution of a pß, pδ-bridging atom oxygen with an imido group in 8 and by a methylene group in 9 led to a weak and non-specific inhibition (Figure 5A). The next three compounds [8-BuS-ATP (1), 8-BuS-AMP (10) and 8-BuS-ADP (11)] specifically inhibited the activity of NTPDase1, while 10 and 11 were stable to hydrolysis by NTPDases. Indeed, analogues 10 and 11 did not affect the activity of the other ectonuleotidases, namely NTPDase2, −3, −8 and CD73, and only modestly inhibited NPP1 and NPP3 (Figure 5). The inhibition of NTPDase1 by 10 and 11 was effective for the human and mouse enzymes, but not for rat NTPDase1 (Figure 5B). The Ki value of analogues 1, 10 and 11 towards human NTPDase1 was estimated at 0.8, 0.8 and 0.9 μM, respectively (Figure 6 and Table 2). The Ki for 8-BuS-ATP was about 10–fold lower than what we reported before for a particulate fraction from bovine spleen (Gendron et al., 2000). Although NTPDase1 was likely the major NTPDase in this tissue, the relative contribution of other nucleotidase in that fraction was not known. Kinetic analysis, as performed using Dixon and Cornish-Bowden methods (Dixon, 1965; Cornish-Bowden, 1974), revealed that 1, 10 and 11 display a mixed-type, predominantly competitive, inhibition towards recombinant human NTPDase1 (Table 2 and Figure 6B-E).

The kinetic parameters of the present series of NTPDase1 inhibitors are more interesting than those already reported for ARL 67156, a commercial NTPDase inhibitor (Iqbal et al., 2005; Lévesque et al., 2007) and POM-1 (Müller et al., 2006; Yegutkin et al., 2012) as both are less potent inhibitors of NTPDase1 than 8-BuS-derivatives. The Ki,app for ARL 67156 was reported to be 11 ± 5 μM and for POM-1 2.6 μM. Both are also not specific inhibitors for NTPDase1 (Müller et al., 2006; Lévesque et al., 2007).

The most active NTPDase inhibitors described in the present study might reveal to be valuable tools for the treatment of certain cardiovascular and immunological disorders. Indeed, recent studies described adenosine and nucleotides as modulators of the development of cardiovascular and immunological complications (Hourani, 1996; Hechler et al., 2005; Waehre et al., 2006). In this study, we found that both derivatives 10 and 11 facilitate platelet aggregation by inhibiting NTPDase1 activity (Figure 9). In a perspective of drug development, such an ability might well be of key importance for patients with haemophilia A, which is associated with low levels of ATP and ADP in thrombocytes (Mareeva et al., 1987). Increases in ADP levels may be also crucial for the therapy of several platelet dysfunctions such as those found in hereditary giant platelet syndrome (Walsh et al., 1975), Noonan's syndrome (Flick et al., 1991), hypothermia (Straub et al., 2011) or thrombocytopenia (Oliveira et al., 2011).

The data presented here suggest that both compounds 10 (especially) and 11 might be used as selective inhibitors of human and mouse NTPDase1 since they are devoid of activity towards other plasma membrane-bound ectonucleotidases (Figures 5, 7 and 8). It can be noted that all three compounds showed variable inhibition of NTPDases from different species as tested in human, mouse and rat (Figure 5B and data not shown). Species specificity has often been observed and this is why one should always be cautious about the molecule used and in which species. For example, other ectonucleotidase inhibitors such as ARL 67156 (Lévesque et al., 2007) and clopidogrel (J Lecka and J Sévigny, unpbl. obs.) show important species differences. The human NTPDases are more sensitive to P2 antagonists than the murine forms (Munkonda et al., 2007) etc.

Inhibition by the BuS derivatives was efficient not only with recombinant NTPDase1, but also when the enzyme was expressed by vascular endothelial cells, as seen with intact HUVECs in culture as well as in situ with different organs from both human and mouse (Figures 5A,B, 7 and 8). Also of interest, neither 10 nor 11 per se triggered platelet aggregation nor prevented ADP-induced platelet aggregation, suggesting that they are inactive towards P2Y1 and P2Y12 receptors. These data are in keeping with the previous observation that compound 1 (8-BuS-ATP) did not affect P2 receptors (Gendron et al., 2000).

In summary, analogues 8-BuS-AMP (10) and 8-BuS-ADP (11) may be used to specifically address the function of NTPDase1 or merely block its ectonucleotidase activity for various in vitro, and potentially, in vivo purposes. Through the specific blockade of NTPDase1, these novel inhibitors also open potential clinical avenues regarding platelet haemostasis, immune reactions and cancer. They may also serve as prototypical structures for the development of even more potent NTPDase1-specific inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a joint grant from The Canadian Hypertension Society and Pfizer, and by grants from the Heart & Stroke Foundation (HSF) of Quebec and from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) to JS. JS was also a recipient of a New Investigator award from the CIHR and of a Junior 2 Scholarship from the Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ). MM-S was sponsored by FIS-PI10/00305. The authors thank Dr. Richard Poulin (Scientific Proofreading and Writing Service, CHUQ Research Center) for editing this paper.

Glossary

- 8-BuS-ADP

8-Thiobutyladenosine 5′-diphosphate

- 8-BuS-AMP

8-Thiobutyladenosine 5′-monophosphate

- 8-BuS-ATP

8-Thiobutyladenosine 5′-triphosphate

- ARL 67156

N6,N6-diethyl-D-β-γ-dibromomethylene-ATP

- DMF

Dimethylformamide

- EGM

Endothelial Cell Growth

- E-NPP

ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase

- E-NTPDase

ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase

- HRMS

high-resolution mass spectrometry

- Pi

inorganic phosphate

- pnp-TMP

p-nitrophenyl thymidine 5′-monophosphate

- POM-1

polyoxometalates

- PPP

platelet-poor plasma

- TEAA

triethylammonium acetate

- TBAP

tetrabutylammonium phosphate

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Atkinson B, Dwyer K, Enjyoji K, Robson SC. Ecto-nucleotidases of the CD39/NTPDase family modulate platelet activation and thrombus formation: potential as therapeutic targets. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2006;36:217–222. doi: 10.1016/j.bcmd.2005.12.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baqi Y, Atzler K, Kose M, Glanzel M, Muller CE. High-affinity, non-nucleotide-derived competitive antagonists of platelet P2Y12 receptors. J Med Chem. 2009;52:3784–3793. doi: 10.1021/jm9003297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baykov AA, Evtushenko OA, Avaeva SM. A malachite green procedure for orthophosphate determination and its use in alkaline phosphatase-based enzyme immunoassay. Anal Biochem. 1988;171:266–270. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(88)90484-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belli SI, Goding JW. Biochemical characterization of human PC-1, an enzyme possessing alkaline phosphodiesterase I and nucleotide pyrophosphatase activities. Eur J Biochem. 1994;226:433–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb20068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigonnesse F, Lévesque SA, Kukulski F, Lecka J, Robson SC, Fernandes MJG, et al. Cloning and characterization of mouse nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-8. Biochemistry. 2004;43:5511–5519. doi: 10.1021/bi0362222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borsellino G, Kleinewietfeld M, Di Mitri D, Sternjak A, Diamantini A, Giometto R, et al. Expression of ectonucleotidase CD39 by Foxp3+ Treg cells: hydrolysis of extracellular ATP and immune suppression. Blood. 2007;110:1225–1232. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-12-064527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun N, Sévigny J, Mishra SK, Robson SC, Barth SW, Gerstberger R, et al. Expression of the ecto-ATPase NTPDase2 in the germinal zones of the developing and adult rat brain. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:1355–1364. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultmann R, Wittenburg H, Pause B, Kurz G, Nickel P, Starke K. P2-purinoceptor antagonists: III. Blockade of P2-purinoceptor subtypes and ecto-nucleotidases by compounds related to suramin. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1996;354:498–504. doi: 10.1007/BF00168442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Purinergic P2 receptors as targets for novel analgesics. Pharmacol Ther. 2006a;110:433–454. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling. Br J Pharmacol. 2006b;147(Suppl. 1):S172–S181. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burnstock G. Physiology and pathophysiology of purinergic neurotransmission. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:659–797. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen BC, Lee CM, Lin WW. Inhibition of ecto-ATPase by PPADS, suramin and reactive blue in endothelial cells, C6 glioma cells and RAW 264.7 macrophages. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;119:1628–1634. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb16082.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciana P, Fumagalli M, Trincavelli ML, Verderio C, Rosa P, Lecca D, et al. The orphan receptor GPR17 identified as a new dual uracil nucleotides/cysteinyl-leukotrienes receptor. EMBO J. 2006;25:4615–4627. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornish-Bowden A. A simple graphical method for determining the inhibition constants of mixed, uncompetitive and non-competitive inhibitors. Biochem J. 1974;137:143–144. doi: 10.1042/bj1370143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crack BE, Pollard CE, Beukers MW, Roberts SM, Hunt SF, Ingall AH, et al. Pharmacological and biochemical analysis of FPL 67156, a novel, selective inhibitor of ecto-ATPase. Br J Pharmacol. 1995;114:475–481. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1995.tb13251.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl RH, Pratley JN. The effects of magnesium on nucleoside phosphatase activity in frog skin. J Cell Biol. 1967;33:411–418. doi: 10.1083/jcb.33.2.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deaglio S, Robson SC. Ectonucleotidases as regulators of purinergic signaling in thrombosis, inflammation, and immunity. Adv Pharmacol. 2011;61:301–332. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385526-8.00010-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon M. The determination of enzyme inhibitor constants. Biochem J. 1953;55:170–171. doi: 10.1042/bj0550170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon M. Graphical determination of equilibrium constants. Biochem J. 1965;94:760–762. doi: 10.1042/bj0940760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enjyoji K, Sévigny J, Lin Y, Frenette PS, Christie PD, Schulte Am Esch J, II, et al. Targeted disruption of CD39/ATP diphosphohydrolase results in disordered hemostasis and thromboregulation. Nat Med. 1999;5:1010–1017. doi: 10.1038/12447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erlinge D, Burnstock G. P2 receptors in cardiovascular regulation and disease. Purinergic Signal. 2008;4:1–20. doi: 10.1007/s11302-007-9078-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausther M, Lecka J, Kukulski F, Lévesque SA, Pelletier J, Zimmermann H, et al. Cloning, purification and identification of the liver canalicular ecto-ATPase as NTPDase8. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:G785–G795. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00293.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fausther M, Pelletier J, Ribeiro CM, Sévigny J, Picher M. Cystic fibrosis remodels the regulation of purinergic signaling by NTPDase1 (CD39) and NTPDase3. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2010;298:L804–L818. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00019.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng L, Sun X, Csizmadia E, Han L, Bian S, Murakami T, et al. Vascular CD39/ENTPD1 directly promotes tumor cell growth by scavenging extracellular adenosine triphosphate. Neoplasia. 2011;13:206–216. doi: 10.1593/neo.101332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flick JT, Singh AK, Kizer J, Lazarchick J. Platelet dysfunction in Noonan's syndrome. A case with a platelet cyclooxygenase-like deficiency and chronic idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991;95:739–742. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/95.5.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gachet C. P2Y(12) receptors in platelets and other hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:609–619. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9303-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gendron FP, Halbfinger E, Fischer B, Duval M, D'Orleans-Juste P, Beaudoin AR. Novel inhibitors of nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases: chemical synthesis and biochemical and pharmacological characterizations. J Med Chem. 2000;43:2239–2247. doi: 10.1021/jm000020b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillerman I, Fischer B. An improved one-pot synthesis of nucleoside 5′-triphosphate analogues. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2010;29:245–256. doi: 10.1080/15257771003709569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goding JW, Grobben B, Slegers H. Physiological and pathophysiological functions of the ecto-nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase family. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1638:1–19. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(03)00058-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guckelberger O, Sun XF, Sévigny J, Imai M, Kaczmarek E, Enjyoji K, et al. Beneficial effects of CD39/ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase-1 in murine intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Thromb Haemost. 2004;91:576–586. doi: 10.1160/TH03-06-0373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbfinger E, Major DT, Ritzmann M, Ubl J, Reiser G, Boyer JL, et al. Molecular recognition of modified adenine nucleotides by the P2Y(1)-receptor. 1. A synthetic, biochemical, and NMR approach. J Med Chem. 1999;42:5325–5337. doi: 10.1021/jm990156d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hechler B, Cattaneo M, Gachet C. The P2 receptors in platelet function. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2005;31:150–161. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-869520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hourani SM. Purinoceptors and platelet aggregation. J Auton Pharmacol. 1996;16:349–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-8673.1996.tb00051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iqbal J, Vollmayer P, Braun N, Zimmermann H, Muller CE. A capillary electrophoresis method for the characterization of ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolases (NTPDases) and the analysis of inhibitors by in-capillary enzymatic microreaction. Purinergic Signal. 2005;1:349–358. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-8076-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jinhua P, Goding JW, Nakamura H, Sano K. Molecular cloning and chromosomal localization of PD-I-beta (PDNP3), a new member of the human phosphodiesterase I genes. Genomics. 1997;45:412–415. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek E, Koziak K, Sévigny J, Siegel JB, Anrather J, Beaudoin AR, et al. Identification and characterization of CD39 vascular ATP diphosphohydrolase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:33116–33122. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.51.33116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauffenstein G, Drouin A, Thorin-Trescases N, Bachelard H, Robaye B, D'Orléans-Juste P, et al. NTPDase1 (CD39) controls nucleotide-dependent vasoconstriction in mouse. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:204–213. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvp265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles AF, Chiang WC. Enzymatic and transcriptional regulation of human ecto-ATPase/E-NTPDase 2. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;418:217–227. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukulski F, Lévesque SA, Lavoie EG, Lecka J, Bigonnesse F, Knowles AF, et al. Comparative hydrolysis of P2 receptor agonists by NTPDases 1, 2, 3 and 8. Purinergic Signal. 2005;1:193–204. doi: 10.1007/s11302-005-6217-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukulski F, Bahrami F, Ben Yebdri F, Lecka J, Martín-Satué M, Lévesque SA, et al. NTPDase1 controls IL-8 production by buman neutrophils. J Immunol. 2011a;187:644–653. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1002680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kukulski F, Lévesque SA, Sévigny J. Impact of ectoenzymes on P2 and P1 receptor signaling. Adv Pharmacol. 2011b;61:263–299. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385526-8.00009-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lévesque SA, Lavoie EG, Lecka J, Bigonnesse F, Sévigny J. Specificity of the ecto-ATPase inhibitor ARL 67156 on human and mouse ectonucleotidases. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:141–150. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Jia ZH, Chen C, Wei C, Han JK, Wu YL, et al. Physiological significance of P2X receptor-mediated vasoconstriction in five different types of arteries in rats. Purinergic Signal. 2011;7:221–229. doi: 10.1007/s11302-011-9226-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludwig J. A new route to nucleoside 5′-triphosphates. Acta Biochim Biophys Acad Sci Hung. 1981;16:131–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandapathil M, Szczepanski MJ, Szajnik M, Ren J, Lenzner DE, Jackson EK, et al. Increased ectonucleotidase expression and activity in regulatory T cells of patients with head and neck cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:6348–6357. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus AJ, Safier LB, Hajjar KA, Ullman HL, Islam N, Broekman MJ, et al. Inhibition of platelet function by an aspirin-insensitive endothelial cell ADPase. Thromboregulation by endothelial cells. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:1690–1696. doi: 10.1172/JCI115485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus AJ, Broekman MJ, Drosopoulos JH, Islam N, Pinsky DJ, Sesti C, et al. Metabolic control of excessive extracellular nucleotide accumulation by CD39/ecto-nucleotidase-1: implications for ischemic vascular diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;305:9–16. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.043729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mareeva TB, Sokovnina Ia M, Votrin II. The role of adenine nucleotides in the functional activity of platelets in hemophilia A. Vop Med Khim. 1987;33:100–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncrieffe H, Nistala K, Kamhieh Y, Evans J, Eddaoudi A, Eaton S, et al. High expression of the ectonucleotidase CD39 on T cells from the inflamed site identifies two distinct populations, one regulatory and one memory T cell population. J Immunol. 2010;185:134–143. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller CE, Iqbal J, Bagi Y, Zimmermann H, Rollich A, Stephan H. Polyoxometalates – a new class of potent ecto-nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase (NTPDase) inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2006;16:5943–5947. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munkonda MN, Kauffenstein G, Kukulski F, Lévesque SA, Legendre C, Pelletier J, et al. Inhibition of human and mouse plasma membrane bound NTPDases by P2 receptor antagonists. Biochem Pharmacol. 2007;74:1524–1534. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2007.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munkonda MN, Pelletier J, Ivanenkov VV, Fausther M, Tremblay A, Kunzli B, et al. Characterization of a monoclonal antibody as the first specific inhibitor of human NTP diphosphohydrolase-3: partial characterization of the inhibitory epitope and potential applications. FEBS J. 2009;276:479–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06797.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira CB, Da Silva AS, Vargas LB, Bitencourt PE, Souza VC, Costa MM, et al. Activities of adenine nucleotide and nucleoside degradation enzymes in platelets of rats infected by Trypanosoma evansi. Vet Parasitol. 2011;178:9–14. doi: 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.12.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picher M, Burch LH, Hirsh AJ, Spychala J, Boucher RC. Ecto 5′-nucleotidase and nonspecific alkaline phosphatase. Two AMP-hydrolyzing ectoenzymes with distinct roles in human airways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13468–13479. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300569200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robson SC, Sévigny J, Zimmermann H. The E-NTPDase family of ectonucleotidases: structure function relationships and pathophysiological significance. Purinergic Signal. 2006;2:409–430. doi: 10.1007/s11302-006-9003-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sévigny J, Robson SC, Waelkens E, Csizmadia E, Smith RN, Lemmens R. Identification and characterization of a novel hepatic canalicular ATP diphosphohydrolase. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:5640–5647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.8.5640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sévigny J, Sundberg C, Braun N, Guckelberger O, Csizmadia E, Qawi I, et al. Differential catalytic properties and vascular topography of murine nucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase 1 (NTPDase1) and NTPDase2 have implications for thromboregulation. Blood. 2002;99:2801–2809. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.8.2801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith TM, Kirley TL. Cloning, sequencing, and expression of a human brain ecto-apyrase related to both the ecto-ATPases and CD39 ecto-apyrases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1386:65–78. doi: 10.1016/s0167-4838(98)00063-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stafford NP, Pink AE, White AE, Glenn JR, Heptinstall S. Mechanisms involved in adenosine triphosphate–induced platelet aggregation in whole blood. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1928–1933. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000089330.88461.D6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stojilkovic SS, Koshimizu T. Signaling by extracellular nucleotides in anterior pituitary cells. Trends Endocrin Met. 2001;12:218–225. doi: 10.1016/s1043-2760(01)00387-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straub A, Krajewski S, Hohmann JD, Westein E, Jia F, Bassler N, et al. Evidence of platelet activation at medically used hypothermia and mechanistic data indicating ADP as a key mediator and therapeutic target. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31:1607–1616. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.226373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vekaria RM, Shirley DG, Sévigny J, Unwin RJ. Immunolocalization of ectonucleotidases along the rat nephron. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2006;290:F550–F560. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00151.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollmayer P, Clair T, Goding JW, Sano K, Servos J, Zimmermann H. Hydrolysis of diadenosine polyphosphates by nucleotide pyrophosphatases/phosphodiesterases. Eur J Biochem. 2003;270:2971–2978. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waehre T, Damas JK, Pedersen TM, Gullestad L, Yndestad A, Andreassen AK, et al. Clopidogrel increases expression of chemokines in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in patients with coronary artery disease: results of a double-blind placebo-controlled study. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:2140–2147. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall MJ, Chen J, Meegalla S, Ballentine SK, Wilson KJ, DesJarlais RL, et al. Synthesis and evaluation of novel 3,4,6-substituted 2-quinolones as FMS kinase inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2008;18:2097–2102. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2008.01.088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh PN, Mills DC, Pareti FI, Stewart GJ, Macfarlane DE, Johnson MM, et al. Hereditary giant platelet syndrome. Absence of collagen-induced coagulant activity and deficiency of factor-XI binding to platelets. Br J Haematol. 1975;29:639–655. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1975.tb02750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittenburg H, Bultmann R, Pause B, Ganter C, Kurz G, Starke K. P2-purinoceptor antagonists: II. Blockade of P2-purinoceptor subtypes and ecto-nucleotidases by compounds related to Evans blue and trypan blue. Naunyn Schmiedebergs Arch Pharmacol. 1996;354:491–497. doi: 10.1007/BF00168441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yegutkin GG, Helenius M, Kaczmarek E, Burns N, Jalkanen S, Stenmark K, et al. Chronic hypoxia impairs extracellular nucleotide metabolism and barrier function in pulmonary artery vasa vasorum endothelial cells. Angiogenesis. 2011;14:503–513. doi: 10.1007/s10456-011-9234-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yegutkin GG, Wieringa B, Robson SC, Jalkanen S. Metabolism of circulating ADP in the bloodstream is mediated via integrated actions of soluble adenylate kinase-1 and NTPDase1/CD39 Activities. FASEB J. 2012;26:3875–3883. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-205658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann H. Ectonucleotidases: some recent developments and note on nomenclature. Drug Develop Res. 2001;52:44–56. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann H. Nucleotide signaling in nervous system development. Pflugers Arch. 2006;452:573–588. doi: 10.1007/s00424-006-0067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann H, Zebisch M, Strater N. Cellular function and molecular structure of ecto-nucleotidases. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:437–502. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9309-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zylka MJ. Pain-relieving prospects for adenosine receptors and ectonucleotidases. Trends Mol Med. 2011;17:188–196. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]