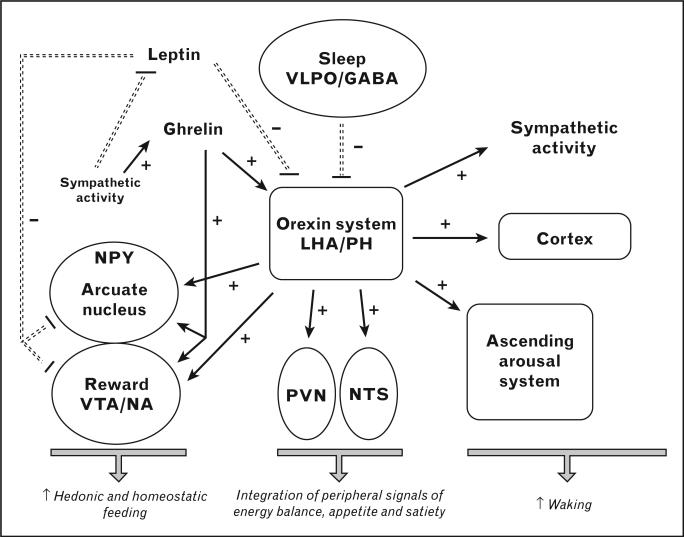

Figure 1. Main pathways connecting sleep–wake regulation and feeding and possible mechanisms for the adverse impact of sleep loss on energy homeostasis.

Central to this hypothesis is the role of the orexin system, which is inhibited by sleep-promoting neurons in the ventrolateral preoptic area (VLPO) containing gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA). The orexigenic neurons, located in the lateral hypothalamic area (LHA) and posterior hypothalamus (PH), play a major role in the maintenance of arousal by activating the ascending arousal system and the entire cerebral cortex and modulating other central nervous system nuclei and structures involved in sleep–wake regulation. Orexin activity is also involved in the regulation of feeding by: (a) increasing the activity of the neuropeptide Y (NPY) neurons in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus, thus, affecting homeostatic food intake; (b) stimulating the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS) and the paraventricular nucleus (PVN), which integrate peripheral signals of energy balance, appetite, and satiety; (c) stimulating the dopaminergic ventrotegmental area (VTA) and nucleus accumbens (NA), the ‘reward centers’, which regulate nonhomeostatic food intake; (d) increasing sympathetic activity, which will in turn inhibit leptin release and stimulate ghrelin release. Lower leptin and higher ghrelin levels will act in concert to further activate orexin neurons resulting in an increased drive for both homeostatic and nonhomeostatic food intake. Adapted with permission from [11].