Abstract

Neurotransmitters and neuromodulators are molecules within the nervous system that play key roles in cell-to-cell communication. Upon stimulation, neurons release these signaling molecules, which then act at local or distant locations to elicit a physiological response. Ranging from small molecules, such as diatomic gases and amino acids, to larger peptides, these chemical messengers are involved in many functional processes including growth, reproduction, memory and behavior. Understanding signaling molecules and the conditions that govern their release in healthy or damaged networks promises to deliver insights into neural network formation and function. Microfluidic devices can provide optimal cell culture conditions, reduced volume systems, and precise control over the chemical and physical nature of the extracellular environment, making them well-suited for studying neurotransmission and other forms of cell-to-cell signaling. Here we review selected microfluidic approaches that are suitable for monitoring cell-to-cell signaling molecules. We highlight devices that improve in vivo sample collection as well as compartmentalized devices designed to isolate individual neurons or co-cultures in vitro, including a focus on systems used for studying neural injury and regeneration, and devices that allow selective chemical stimulations and the characterization of released molecules.

Introduction

Animal behavior and physiology is, to some extent, controlled by the interactions between networks of neurons and glia within the central and peripheral nervous systems. Within these networks, large numbers of molecules act to maintain, inhibit, and excite neurons. After an appropriate electrical or chemical signal is received, a neuron may release compounds that range from gases to small molecules and peptides. These signaling molecules—neurotransmitters and neuromodulators—are involved in an extensive variety of physiological processes including learning, memory, sleep, and response to disease.1 Damage or injury to these networks can lead to abnormal, limited, or non-existent function, which has been implicated in a wide range of conditions including depression and neurodegenerative diseases.1-5 Understanding the extracellular environment, as well as identifying the signaling molecules that form the basis of these connections, could allow us to implement strategies to restore function to damaged neural networks.

To address these challenges, a wealth of sample handling and analysis methods have been applied to examine neurotransmission.6 Capillary electrophoresis (CE) and liquid chromatography provide analyte fractionation/separation, while methods such as laser-induced fluorescence, immunoassay, and mass spectrometry (MS) are employed for detection.6 Direct electrochemical methods and microdialysis are widely used to probe cellular networks in vivo to examine molecular changes within the brain and determine correlations between chemical dependency and behavior.7-9 While in vivo methods are used to sample specific regions of the brain, the sample volumes obtained effectively involve at least tens of thousands or more cells, resulting in an “averaging” of the extracellular milieu. As neurons (and glia) in a spatially defined location oftentimes have distinct chemical constituents and functions, important information is often lost. Alternatively, one can isolate individual cells from a defined region and either assay them or culture them in vitro, allowing for the detection of mass-limited molecules that may not be detected in bulk averages. For in vitro measurements, care must be taken to create an extracellular environment that mimics in vivo conditions.

In vitro and in vivo methods can yield complimentary information. In vivo analytical measurements provide information on the molecules present in a specific region in the brain, providing a basis for identification in vitro. The most common in vivo monitoring techniques are microdialysis and electrochemistry.7-9 Microdialysis is a technique that continuously monitors the chemical environment at the location of a probe inserted into the tissue of interest. The approach has been useful for examining activity-dependent (and pharmacological-dependent) changes in specific brain regions, although it can be limited to monitoring neurochemical changes on the second time scale.10,11 Electrochemical sensors implanted into the brain provide information from a specific location and can be scaled to the micron level, and have been especially useful for examining electroactive transmitters such as dopamine 7,12 and serotonin.13 As an example, fast-scan cyclic voltammetry can monitor changes in release and uptake rates in near real time.14 In vitro analyses of tissues from specific brain regions or cells can involve the isolation and investigation of molecules within a specific cellular network, single cells,15-17 or brain slices.18,19 Dish-based cultures and brain slice chambers are the more common methods used for culturing neural networks and brain slices in vitro, and have resulted in exciting advances in our knowledge of neurochemical release and the pathways involved.

In recent years, microfluidics has been incorporated into the field of neuroscience, providing a unique set of capabilities that enable selected measurements, such as spatially well-defined cell cultures, axonal/dendritic growth guidance, reduced sample volumes, and improved control and manipulation over the extracellular environment.20,21 Both perfusion and compartmentalized devices have been created to maintain long-term, healthy cultures in small-volume devices.22-24 Physical barriers, gradients, and surface patterning aid in guiding neuron growth and investigating processes separately.23,25-28 With the advent of microvalves29 and precise fluid handling, the extracellular space can be precisely tuned and controlled to mimic in vivo environments; as a result, the conditions required for neurotransmitter release can be determined.29,30

Microfluidics has been implemented for in vivo analyses, including microdialysis, to shorten analysis times and integrate on-line sample derivatization.11 Many of the same detection platforms used in traditional neurotransmitter analyses have been coupled to microfluidics. With these attributes, microfluidics is becoming an enabling technology for investigating cellular environments and for identifying key signaling molecules that are involved in both healthy and damaged networks. This review is not comprehensive, but rather, highlights recent advances in microfluidics that have furthered our ability to understand the complex nature of cell-to-cell signaling in the brain. We also speculate on how devices that have been used for several related measurements can be adapted for measuring neurotransmission.

In vivo Analyses

As mentioned earlier, many in vivo analyses measure the signaling molecules released from a defined region. Microdialysis is an effective tissue sampling strategy that has been applied to study many areas of the brain.11,31 A probe with a semipermeable, size-selective membrane with a molecular weight cutoff is surgically implanted into the brain and a solution is continuously perfused into and out of the probe; compounds that diffuse across the membrane in the probe are thus sampled. Changes in the chemical makeup of the perfusate are monitored by selective detection (such as antibodies), or by coupling the output to separation techniques such as liquid chromatography or CE with laser-induced fluorescence, MS, ultraviolet or electrochemical detection.10,32 Microdialysis sampling is currently not assayed in real time, therefore the approach does not provide information on changes in neurotransmitter levels on the millisecond to second time scale. Several groups have worked to integrate microfluidics into microdialysis probes, enabling faster analysis times and the ability to sample at lower flow rates, leading to higher sample recovery and greater temporal resolution.

As an example, Nandi et al.33 reported a serpentine channel system that couples microdialysis and microchip electrophoresis for the detection of amino acid neurotransmitters from the rat striatum. Glutamate and aspartate were sampled from the brain and derivatized online prior to laser-induced fluorescence detection. The channel was fabricated in polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) to allow for more complex designs and to remove the bonding challenges associated with glass chips. The serpentine channel increased the separation length over traditional microchip CE setups and improved the resolution. Following offline optimization, the device was applied in vivo to continuously monitor glutamate and aspartate from the rat brain.

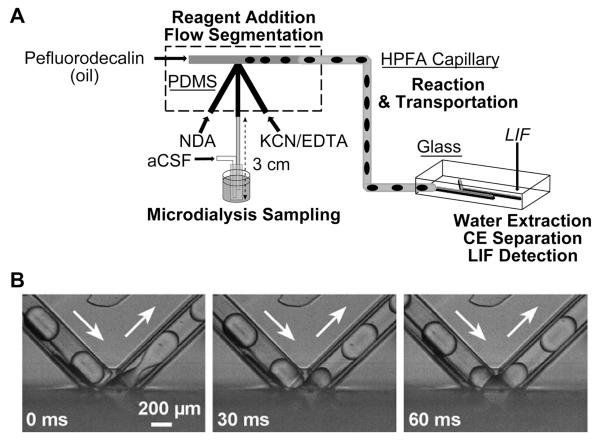

As analytes migrate along a channel, dispersion will occur within that channel, leading to a reduction in temporal resolution. To reduce the effects of this dispersion, the Kennedy group34 introduced an ingenious segmented flow system into an online microdialysis setup. Aqueous microdialysates were collected from rat brain and segmented into aqueous droplets surrounded by an oil phase, creating thousands of discrete analyte plugs. As analytes traveled along the channels, diffusional broadening was limited to a droplet and so for a longer analysis, the total broadening was greatly reduced. They described a two-device system to collect amino acids from rat striatum with 35 s temporal resolution. The system consisted of a PDMS flow chip, which created the plugs, that was connected to a glass electrophoresis chip (Fig. 1A). The plugs were derivatized online and extracted into a glass CE microchip where the plug contents were analyzed by laser-induced fluorescence.

Fig. 1.

Microfluidic device designs that incorporate segmented flow for improved cellular sampling. (A) Schematic of a dual-chip design for in vivo monitoring of amino acid transmitters from the rat striatum. The first chip creates plugs that contain dialysate and a fluorogenic reagent. Plugs flow to the glass electrophoresis chip for separation and detection with fluorescence (aCSF = artificial cerebral spinal fluid; NDA = naphthalene-2,3-dicarboxaldehyde; KCN = potassium cyanide; LIF = laser induced fluorescence). Adapted with permission from M. Wang, G. T. Roman, M. L. Perry and R. T. Kennedy, Anal. Chem., 2009, 81, 9072–9078. Copyright 2009 American Chemical Society. (B) Bright field images of chemistrode stimulation plugs contacting the surface and forming a response plug. Used with permission from D. Chen, W. Du, Y. Liu, W. Liu, A. Kuznetsov, F. E. Mendez, L. H. Philipson and R. F. Ismagilov, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., 2008, 105, 16843-16848. Copyright 2008 National Academy of Sciences, USA.

In a subsequent study by Kennedy’s group,35 they described a technique that directly combined microdialysis and segmented flow with electrospray ionization MS for in vivo monitoring of acetylcholine. The setup consisted of a microdialysis probe connected to the brain of a live rat, an oil channel interface for creating segmented plugs, and a diluent for MS. MS is well suited for neurotransmitter study as it allows for detection of a wide range of neurotransmitters within a single mass spectrum without a need for analyte pre-selection. The authors were able to measure basal and elevated acetylcholine levels and achieve a temporal resolution of 5 s. Since neurotransmission occurs on the millisecond to minute time scale, the enhancements shown in the previous two examples represent important advances toward real-time analysis over the physiological range of transmission.

Low-flow, push-pull perfusion devices offer an alternative to microdialysis sampling. Instead of analyte migration taking place across a membrane, push-pull perfusion requires two different tubes, one that infuses artificial cerebrospinal fluid into tissue and one that withdraws solution from the region.6,36 While push-pull perfusion was previously shown to damage tissue within the sampling region, smaller capillaries and lower flow rates have greatly improved the application of perfusion devices.6 Sampling areas are smaller than microdialysis probes and thus yield better spatial resolution, an important consideration because of the cell-to-cell heterogeneity that exists among different regions and within the same region of the brain. To improve spatial resolution, Kennedy and colleagues37 coupled a push-pull perfusion system with a segmented flow system to monitor L-glutamate release from an elevated K+ stimulation. They were able to achieve a temporal resolution of 7 s with a spatial resolution of 0.016 mm2, an 80-fold improvement over a relatively small microdialysis probe. As the extracellular fluid was withdrawn from the tissue, it was combined with an oil to form the plugs, and the Teflon tubing with the sample plugs was stored. The sample plugs in the tubing were then combined with another microfabricated unit that added enzyme and fluorogenic dye to the plugs, and then analysis was performed by fluorescence. This offline storage and analysis system is flexible and can be applied to a number of detection platforms and cell-sampling schemes.

The final device system highlighted in this section has application for both in vivo tissue analysis and in vitro cellular analysis. The chemistrode is a microfluidic platform that consists of a droplet-based device with a delivery channel, a droplet and sample interface, and collection and analysis channels.38 Stimulation solutions are delivered by a plug and contact the hydrophilic surface. The released molecules are captured and reformed into a segmented plug format (Fig. 1B). The plugs contain aqueous solutions surrounded by a fluorocarbon carrier fluid. Channels within the device are functionalized with hydrophobic and fluorophilic coatings to retain the carrier fluid on the wall of the chemistrode when it comes into contact with the hydrophilic surface. Analyte plugs reform in an exit channel and then can split into different channels for analysis. With high spatial (<15 μm) and temporal resolution (~50 ms), the chemistrode has a wide range of potential applications related to stimulating and analyzing neurotransmission. This system was applied to study insulin release from a single glucose-stimulated islets of Langerhans, demonstrating its applicability to live cell studies. The chemistrode could allow for precise control of stimulation addition and analyte collection and detection for both in vivo and in vitro neurotransmission experiments.

Overall, we expect that microfluidic systems specifically designed to study neurotransmission in vivo will continue to be advanced. The greater our ability to sample and stimulate at high spatial and temporal resolution in vivo, the more likely we are to attain a better understanding of neurotransmitter signaling in defined brain regions.

In Vitro Analyses

In what follows, we describe a number of microfluidic devices that have been used for cell culturing, selected sampling from defined locations, examining network formation, injury and repair, and characterization of the extracellular media. Although these examples have relevance to cell-to-cell signaling research, several of them have not yet been used in this context.

Refining neuron culture

To study neurotransmission in vitro, it is important to create an extracellular environment that closely mimics physiological conditions. The effective culture of cellular networks and single cells requires careful O2, CO2, and temperature control, delivery of essential nutrients, and waste removal. The optimization and study of cell growth and culture in dishes has greatly improved our understanding of the precise environmental conditions necessary to grow healthy, viable cultures that can be interrogated using a number of approaches.39 Microfluidics expands on the ability to culture neurons by providing spatially defined and temporally controlled culturing environments.

Many microfluidic systems have been used to culture a wide range of neuronal types, from the mammalian hippocampus27,40,41 to molluscan neurons of Aplysia californica.26,27 There are two particularly noteworthy device types, perfusion and compartmentalized, that enhance cell culture and allow access to the cells within the device. Perfusion culture platforms, such as the one detailed by Tourovskaia et al.,42,43 continuously deliver media and remove cellular waste, which allows for long-term culturing. Compartmentalized devices isolate cell bodies and axons, enabling the investigation of a wide range of physiological processes.44

While cell culture in devices offers ease of fluid handling, optical transparency, and gas permeability, the approach also presents several challenges that are unique to small-scale culturing due to the materials used. For example, PDMS has long been the material of choice in fabricating microfluidic devices, but contamination caused by uncrossed oligomers and metal catalysts entering bulk solutions have been noted as issues that affect cell viability.45 The absorption of small molecules and essential media components into the polymer has also been reported.45-49 To combat these challenges, a number of groups have instituted extraction procedures that render the PDMS more amenable to cell growth,40,45 allowing long-term, low density cultures. Continuing to improve neural culturing approaches that better mimic in vivo conditions should yield more physiologically accurate results when studying a wide range of processes.

Investigating signaling molecules at defined cellular locations

The brain consists of billions of individual neurons and glia, and much of the chemical communication between these cells occurs through synapses. Neurons are typically composed of a cell body with an axon and multiple dendrites. In many cases, chemical messengers are released across the synapse from the presynaptic side of one neuron to the dendritic spine of another. However, some signaling molecules can be released at other locations; as examples, neuropeptide release can occur at the soma or dendrites, and nitric oxide diffuses across membranes and so can modify signaling at a range of target cells. Receptors for the transmitters are located at the postsynaptic neuron, or in some cases, on distant cells; they can be located on axons, dendrites, or the cell soma.50-52

The past decade has seen the design of compartmentalized devices that isolate individual cell bodies from their axons so that each region (soma, axon and dendrite) can be investigated separately.44 These devices typically consist of two main channels with small (~10 μm high), fluidically isolated interconnects. Cell bodies are loaded into the somal compartments and axons grow through the small channel interconnects into the axonal side. Fluidic isolation allows for the selective stimulation of one region of the neuron and collection of released molecules in other compartments. In some cases, two separate cultures are investigated within the same device. Compartmentalized devices have been used to examine a wide range of neural functions, from axonal transport to injury and regeneration.44 Although these devices have not always been applied to studying neurotransmission, they are adaptable to examining signaling molecules found in individual neurons as well as those found at neuron-neuron and neuron-glia synapses. The ability to access both the somal and synaptic compartments should allow for separate stimulation and investigation of released molecules during growth, development, and network formation.

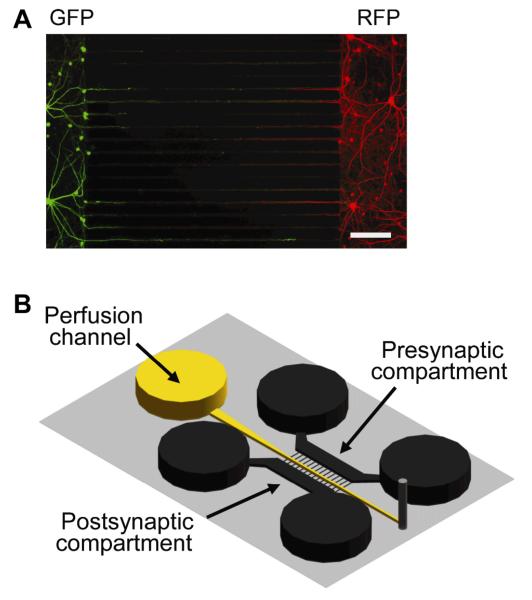

In 2005, the Jeon group23 demonstrated that axons could be selectively interrogated from cell bodies by the growth of a high density neuronal culture. The platform and its subsequent modifications polarized the growth of axons through interconnects into a fluidically isolated axonal compartment. The device was originally applied to study injury and regeneration, axonal mRNA and transport, and co-cultures of oligodendrocytes and neurons. Since then, the device design has been modified for a variety of applications, including the investigation of synapse formation within compartmentalized microgrooves (Fig. 2).41 The device has been used to allow segregation of two neuronal populations and to deliver essential nutrients to neuronal connections, but can be adapted for analyte collection at the connections between two cell cultures to study neuron-neuron, glia-neuron, or even glia-glia interactions. Glia-neuron interactions are particularly interesting because communication between both cells can be chemical and their two-way communication is considered to be essential for the central nervous system to function properly.53 Nevertheless, the current molecular information regarding glia-neuron communication is limited and investigations are needed to understand the full extent of their interactions.

Fig. 2.

Microfluidic devices that use a series of small interconnects to allow independent control of solutions in the larger channels and to separate cell soma from processes. (A) An example of synapse formation between two neuron cultures within a compartmentalized device. Cell bodies expressed green and red fluorescent protein on the left and right, respectively, with processes extending into interconnects between the two cultures. (B) Compartmentalized device with a perfusion channel in between somal compartments. Adapted with permission from A. M. Taylor, D. C. Dieterich, H. T. Ito, S. A. Kim and E. M. Schuman, Neuron, 2010, 66, 57-68.

More recently, new devices have been designed to effectively co-culture axons and glia. Hosmane et al.54 incorporated open, circular access ports to reduce the difficulty in cell loading and improve access to cell bodies for chemical or electrophysiological studies. Similar to previous designs, axons are guided through interconnects to an axonal compartment where they are then co-cultured with glia through a PDMS microstencil. H2O2 was applied to one access port to study the response of glia to axonal degeneration, when compared to non-damaged cells.

In a device described by Majumdar et al.,55 a co-culture of primary hippocampal neurons and glia was accomplished by placing the cultures into two different chambers that were separated with a microvalve-controlled channel. During culture, the valve was deactivated so that chemical interactions between the two cultures were possible. Following culture, the valve was activated and both compartments were fluidically isolated for specific investigations. The authors observed that in the absence of glia or glia-conditioned media, neuron viability was limited to one week, whereas cultures were healthy for more than three weeks during the co-culture conditions.

Compartmentalized devices offer a unique way to isolate individual neurons and co-cultures, allowing processes and synapses to be interrogated. These systems have not yet been used to monitor neurotransmission, but we believe that the addition of channels for analyte collection, or modification of these devices for online analysis, will be implemented in the not so distant future.

Neuronal injury and regeneration

Damage or injury to neural networks has been implicated in a number of neurodegenerative diseases. Comparisons between healthy and diseased nervous systems, and identifications of molecules involved in repair, will provide essential information for repairing a damaged network. When studying injury and regeneration in vitro, different means of injury have been used, including chemical and mechanical. Chemical injury involves focusing an injury stream or directly applying the chemical of interest to the entire channel. These solutions can be localized to a small region or can dissolve the entire neural process. Mechanical injury involves severing processes with a knife or needle, aspirating the channel, or applying a laser for transection. One of the first applications demonstrated in a compartmentalized device by Taylor et al.23 was to vacuum aspirate the axonal compartment and collect somal fractions to study changes in mRNA expression.

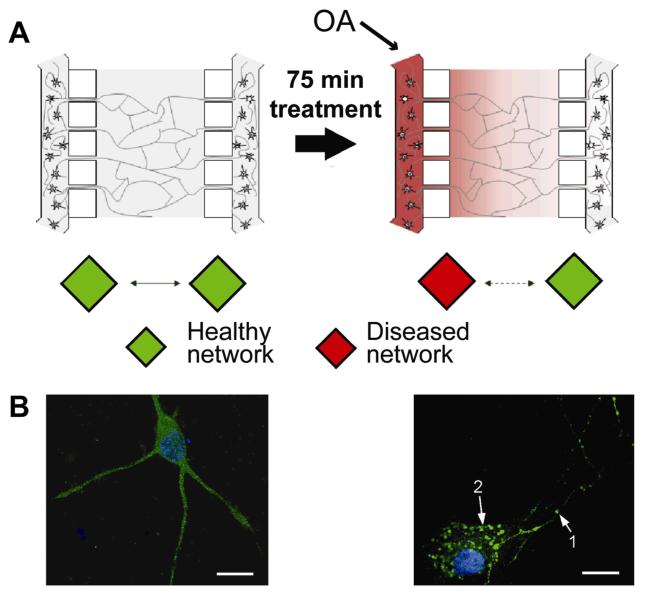

Compartmentalized devices offer many advantages for modeling disease in vitro. When neurons are isolated, any chemical or mechanical injury that is induced in the axonal compartment will be specific for axons only. Therefore, using compartmentalized devices to study axon injury and regeneration can aid in the understanding of what factors and environmental conditionals are essential for repair during process regeneration. Kunze et al.56 modified a compartmentalized device to model Alzheimer’s disease by creating healthy and diseased cortical neuron cultures (Fig. 3A). Two identical cultures were loaded into separate somal compartments, and neurites then extended through small interconnects to the main channel. One set of cells (located on one side of the device) were exposed to okadaic acid, which induces hyperphosphorylation in tau proteins, a condition implicated in Alzheimer’s disease; the other culture remained healthy and viable (Fig. 3B). Although signaling molecules were not studied in this device, slight modifications for sample collection would be straightforward and could provide molecular information on healthy and diseased cell populations for comparisons.

Fig. 3.

A compartmentalized device used to model disease by creating healthy and diseased neuron cultures. (A) Schematic showing the culture of two healthy neural networks and the application of okadaic acid (OA) to create a diseased network with phosphorylated tau proteins, a condition implicated in Alzheimer’s disease. (B) Two cells representing (left) healthy and (right) diseased cultures. The diseased neurons show the clustering of phosphorylated tau clusters in (1) neurites and (2) soma. Adapted with permission from A. Kunze, R. Meissner, S. Brando and P. Renaud, Biotechnol. Bioeng., 2011, 108, 2241-2245.

To mechanically induce injury, a device was designed that incorporated a 180 ps duration laser to either partially or fully transect an axon of interest.57 The design contained alternating micropatterned substrates fabricated on glass to facilitate cell growth. Cortical cells were loaded into a PDMS channel and grew down the micropatterned substrate. Following injury, neuron regrowth and regeneration was monitored in standard and ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid media to study the effects of extracellular calcium on axonal degeneration.

Hosmane and colleagues58 designed a system that induced axonal injury on hippocampal neurons through a micro-compression platform. The platform was connected to a valve system that delivered varying amounts of pressure to an axon to induce injury. Degeneration and growth were monitored under mild to severe injury conditions.

Each of these devices offers a different approach for inducing injury to a neural culture. With modification for molecular collection and detection, these devices will offer a significant contribution toward understanding the molecular interactions within a diseased network and identifying essential molecules for repair.

Engineering the extracellular microenvironment

Tissue and cell homogenates, single cell analyses, and in vivo collections give insight into the molecular complement of a given region or cell type. However, the presence or even the release of a molecule does not prove its function as a neurotransmitter. The classification of a molecule as a neurotransmitter requires that it fit several criteria, including its synthesis within a neuron, its release upon appropriate physiological stimulations, and the creation of the appropriate response in the postsynaptic cell. Microfluidics offers unique advantages for addressing these criteria as these devices can provide an appropriate environment for exposing specific cells to putative transmitters, allowing one to follow the cells’ response, while also aiding the collection and characterization of transmitter releasate. The ability to precisely control the extracellular environment through nutrient delivery, fluid flow, and surface gradients helps to create a milieu that more closely mimics in vivo conditions. Studying neurotransmission, controlling and understanding the application of chemical stimulations that result in transmitter release, and engineering the environment for better neurotransmitter identification, will give further insight into the conditions that govern cell-to-cell communication. To that end, this section is in two parts: designs that primarily address chemical stimulation and those that focus on identifying released molecules.

Selective chemical stimulations

Chemical communication within the nervous system is dynamic, adjusting to the extracellular environment and the input and output of molecular signals. Neurons are constantly exposed to a complex chemical milieu. Whether or not a neuron will release its contents depends on the amount and length of exposure and whether a particular chemical initiates inhibitory or excitatory responses in the cell. It is important to consider both the concentration and duration of exposure when creating a chemical stimulation delivery system. The relative ease of operation of the fluid handling and valve systems in microfluidic devices enables precise control and localized additions of chemical stimulations. Several groups have developed devices that precisely deliver chemical stimulations to cells or brain slices. Sabounchi et al.59 reported a biochemical pulse generator that traps cells onto one side of a channel by negative pressure. An upstream pulse channel delivered a reagent pulse to several adjacent cells. During the entire experiment, cells were subjected to a constant buffer stream that both directed and removed reagent from the cells. If this device were modified for cell culture, cells could be stimulated in a localized fashion and collected downstream.

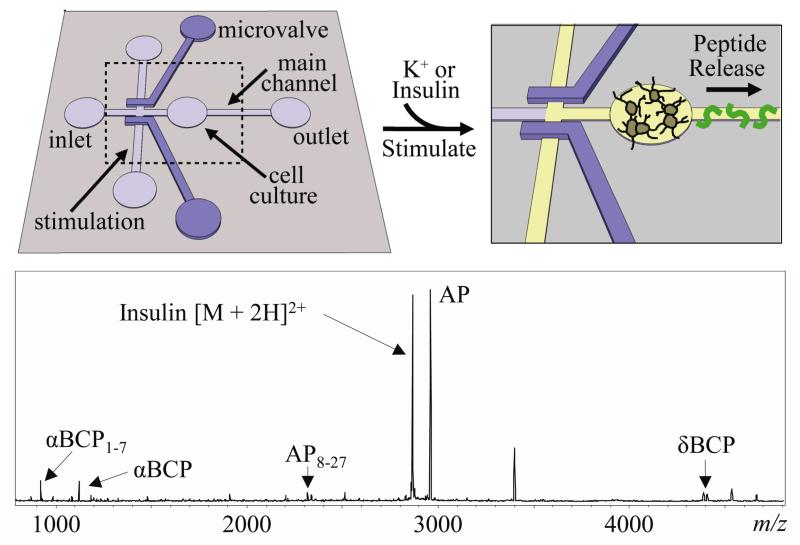

Our group recently described a device that used microvalve-controlled stimulation channels to administer controlled and increasing periods of chemical stimulations to a cultured network of Aplyisa californica bag cell neurons (Fig. 4).60 Following stimulation, neuropeptide solutions were collected off-line and characterized with MS. When providing additional temporal control over the duration of stimulation, the amount of chemical stimulation necessary for release can be determined. A robust difference in the temporal dynamics of peptide release was observed for two different chemical stimulations, elevated K+ and insulin, demonstrating the importance of temporally controlling the secretogogue duration. A bath application of both stimulations would not have identified the difference in extracellular conditions necessary for release. This device can be applied to a variety of cell types, including amino acid and small molecule transmitters.

Fig. 4.

Top. Schematic of a device used to selectively apply chemical stimulations to neuronal networks maintained in the device. Microvalve-controlled channels are opened to apply increasing periods of stimulation to determine the temporal dynamics of release. Bottom. Mass spectrum shows the detection of peptides released from the bag cell neurons of Aplysia upon insulin stimulation (AP = acidic peptide; BCP = bag cell peptide). Adapted with permission from C. A. Croushore, S. Supharoek, C. Y. Lee, J. Jakmunee and J. V. Sweedler, Anal. Chem., 2012, 84, 9446-9452. Copyright 2012 American Chemical Society.

Brain slice analysis is a reliable neuroscience tool used to isolate and conserve local connections within a brain region of interest under a precisely controlled environment.18,61 The open nature of brain slice chambers simplifies investigations using microscopic or electrophysiological approaches.19 In traditional brain slice analysis, the efficient delivery of essential nutrients and finely controlling the environment around the entire slice can be challenging.19 Microfluidics has been incorporated into the approach to achieve added control over the neurochemical environment and to improve nutrient delivery and waste removal. For neurotransmitter studies, microfluidics has enabled the selective delivery of chemical stimulations to localized regions within the slice.

One such strategy developed by Mohammed et al.62 employed a series of vertical openings underneath the brain slice that perfused solutions to precise regions on the slice. The specific addition of solutions was used to stimulate microscale areas of the brain slice. The setup monitored dopamine delivery into the tissue with cyclic voltammetry. One of the major benefits of this technique is the ease with which it can be integrated with standard brain slice chambers.

In another approach to couple brain slice analysis with microfluidics, Tang et al.63 used microposts to support the slice. Several posts were replaced with fluid ports, which were used to selectively deliver or withdraw stimulation solutions to regions of the brain slice. To demonstrate the utility of the device, cortical spreading depression was induced by applying elevated potassium to the tissue, which depolarizes the cell membrane. With this design, specific brain regions could be selectively stimulated and the molecules of interest collected and analyzed. The ability to selectively stimulate brain regions can yield molecular information about a precisely controlled region while preserving morphology. As discussed above, both microvalves and fluid ports can be fabricated to better interrogate networks and brain slices.

Designing a system that allows precise stimulation addition to a neural network or brain slice will provide information regarding the duration and concentration of stimulation necessary to elicit neurotransmitter release. Brain slice chambers that allow the user to selectively interrogate specific brain regions will yield details about the molecular content of the region of study. By modifying these devices to enable molecular collections, we can assay the complex chemical environment dictating inhibitory or excitatory responses from a cell.

Identifying and quantifying released molecules

The previous section described selective chemical stimulations of single cells, networks, or brain slices. Here we highlight approaches to measure and identify released neurotransmitters. The small volumes afforded by microfluidics lead to a reduction in dilution, allowing for the collection and detection of mass-limited neurotransmitters. Through the incorporation of optimized designs and surface modifications, more efficient analyte collections become feasible compared with bulk dish-based methods. Several of these devices are discussed below.

One challenge in neurotransmitter analysis involves chemically complex samples, where, for example, matrix effects and high salt concentrations often limit detection capabilities. To reduce sample complexity, cleanup/preparation steps involving separation-based methods such as liquid chromatography, CE, spin columns and packed pipet tips are often used. Incorporating sample clean-up and analyte detection on chip is particularly advantageous for reducing sample loss and minimizing the time spent in sample cleanup. Lin and colleagues64 reported a method that connected a cell culture device to an extraction device to study changes in glutamate transmission. The first device maintained and stimulated PC12 cells in culture, while the second consisted of an extraction region to capture glutamate within a packed column. After extraction, the cell chip was removed and the extraction chip directly connected to an electrospray-quadrupole-time of flight mass spectrometer. This approach reduced sample loss by collecting secretions in-line with the cell chamber. Additionally, a wide range of cell types can be cultured in the cell culture chip. Combining these capabilities into one device and adding additional extraction chips would further reduce sample loss and allow for temporally-resolved collections.

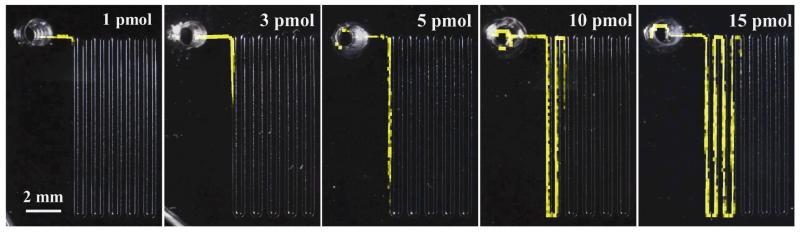

Our group has published two device designs for collecting and analyzing neuropeptide release on-chip with mass spectrometry imaging. In an initial study, Aplysia bag cell neurons were cultured on a silicon wafer and stimulated with elevated K+.65 Released peptides migrated down PDMS channels across a C18 functionalized silicon wafer and were adsorbed to the surface through hydrophobic interactions. The PDMS channels were removed and matrix was applied to the surface. The entire chip was imaged via matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization MS. A mass spectrum was generated at each laser spot and the peptide localization was visualized throughout the channels. By increasing the number of collection channels, better insight into the qualitative and temporal aspects of release can be determined using this approach. Since matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization MS is not inherently quantitative, the device was modified to quantify peptide release on chip by correlating the peptide adsorption length down a channel to the amount of peptide present.47 Figure 5 shows false color images of peptide localization throughout the channels for increasing amounts of peptide. Each pixel corresponds to a mass spectrum containing the peptide of interest. After the creation of a standard curve relating the two variables, peptides from the bag cell neurons were collected and quantified and the results were in agreement with previous data. One advantage of this technique is that both device designs are amenable to multiple cell types, enabling the study of a variety of neuropeptides and neurotransmitters.

Fig. 5.

False color mass spectrometry images demonstrating the length of peptide adsorption down a C18 functionalized substrate corresponds to the amount of peptide present. Each pixel corresponds to a mass spectrum containing the peptide of interest. Used with permission from M. Zhong, C. Y. Lee, C. A. Croushore and J. V. Sweedler, Lab Chip, 2012, 12, 2037-2045.

Further reductions in sample complexity to isolate and study single clusters or even individuals cells within a network should provide added insight into the heterogeneity of a cell population. An automated approach has been described that simultaneously quantified insulin release from 15 islets of Langerhans on-line by microchip electrophoresis and fluorescence detection.66 Individual islets were loaded into a reservoir containing 10 mM glucose to evoke release. The sample stream was then derivatized on-line and periodically injected into an electrophoresis channel. Immunoassasys were performed at 10 s intervals. This design offers a high-throughput approach to quantify release. Alternatively, measuring the effects of different stimulations on single cells could be possible.

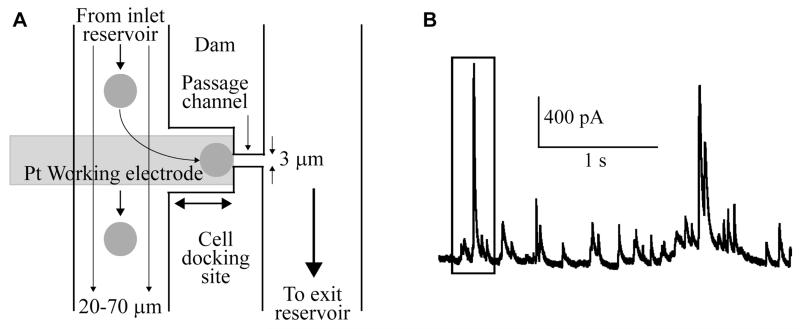

Gao et al.67 created a system that measures catecholamine exocytosis from single chromaffin cells trapped on electrodes by amperometric detection. Cells were loaded into one cellular channel, which was connected to an exit channel through interconnects. At each interconnect, there was a docking station that acted as a cell trap and contained an amperometric sensor fabricated underneath the docking station (Fig. 6A). When stimulated, catecholamine release was detected on chip, reducing the need for off-line sample preparation and analysis (Fig. 6B). The on-chip analysis offers reduced sample cleanup or loss that occurs when samples are analyzed off chip. This device has the potential to more closely mimic in vivo interactions if the cells are cultured in the device and allowed to form networks.

Fig. 6.

(A) Schematic of a microfluidic device used for cell capture with amperometric detection of catecholamines. Cells are loaded into the device and negative pressure is applied to the exit reservoir, drawing cells down the channel and into the cell docking sites. (B) Recording of catecholamine exocytosis over several second intervals, with each spike representing release of an individual granule. Adapted with permission from Y. Gao, S. Bhattacharya, X. Chen, S. Barizuddin, S. Gangopadhyay and K. D. Gillis, Lab Chip, 2009, 9, 3442-3446.

In a device that combined on-chip sample preparation with off-line ion-mobility MS, Enders et al.68 examined a wide range of biological responses of cell populations in near-real time. These preliminary experiments were done with yeast and Jurkat cells. The device consisted of two sets of channels and valves that directed cell effluents into a pre-treated C18 column to collect peptides, metabolites, etc. While the material was eluted from the first column, the new cellular effluent flowed through a different C18 column in an alternating fashion to reduce sample loss. Samples were spotted onto a mass spectrometry target prior to ion mobility MS detection. While not employed for neurotransmitter analysis, with the ability to collect and concentrate cellular effluents on chip, this device could be modified to temporally study neurotransmitter release.

The Martin group has reported several approaches for on-chip detection of release from PC12 cells. A study by Li et al.69 temporally quantified catecholamine release on-chip with a carbon microelectrode. Cells were loaded into collagen coated PDMS microchannels and were exposed to calcium to elicit release. Catecholamine release was measured and showed an increase in response to larger cell populations. Bowen and Martin70 reported a culture and analysis system where PC12 cells were cultured on a thin PDMS micropallet. After culture, the entire micropallet was loaded into the reservoir. Dopamine and norepinephrine secretions were injected into a microvalve-controlled electrophoresis channel. Detection was performed with a carbon microelectrode. Culturing neurons on a micropallet utilizes the benefits of established dish-based culture methods. Placing micropallets into the device is a unique idea to reuse devices and analyze multiple micropallets.

Thus far, most of this review has focused on classical and neuropeptide transmitters. However, several gases meet some of the definitions of a neurotransmitter. These unconventional transmitters include H2S, CO, and NO. Few studies have incorporated microfluidics into the study of gas release from neurons. In cell culture applications, the gas permeable nature of PDMS allows for necessary gas exchange in culture. However, when studying release, these molecules can escape from the channels prior to detection. Therefore, alternative materials are required for such studies or detection must be performed close to the cells of interest. Halpin and Spence71 fabricated a microfluidic device for the detection of NO on chip by a standard microtiter plate reader. The device design consisted of two PDMS layers with a porous polycarbonate membrane placed in between. Following device optimization, erythrocytes were pumped into L-shaped channels and any released NO flowed through the polycarbonate membrane into wells. The wells were then aligned to the microplate reader and NO concentrations were determined by fluorescence. This device offers the ability to detect and quantify NO and to incorporate a standard laboratory technique for detection.

Amatore and colleagues72 reported another study that investigated NO and other reactive nitrogen species by amperometry on a low density macrophage culture. The microfluidic device consisted of three microelectrode bands on a glass substrate that were oriented orthogonally to the flow channel. They observed a robust response in oxygen and nitrogen species production following the introduction of a calcium ionophore. This device design offers a method for studying NO release from a low-density culture directly on-chip with real time analysis.

By developing approaches that enhance the ability to identify neurotransmitters we can expect to gain further insight into the signaling molecules found within neurons. Reducing sample preparation time and performing analyses directly on chip can facilitate the detection of mass-limited samples, which are often lost in off-line sample preparation procedures. Incorporating temporal control that better mimics in vivo conditions and quantifying neurotransmitters will provide a better understanding of release. Finally, designing devices that readily adapt to existing detection platforms streamlines the integration of microfluidics technology into neuroscience laboratories.

Conclusions and Future Directions

In this tutorial review, we have highlighted a number of microfluidic device designs that we believe have contributed, or have the potential to contribute, to the study of neurotransmission both in vivo and in vitro. Microfluidics offers improved analysis times and spatial resolution when coupled to microdialysis and electrophoresis, allowing for more real-time analyses of released molecules. Compartmentalized devices provide the fluidic isolation features that are necessary for interrogating release at synapses, furthering the study of neuron-neuron and neuron-glia interactions. Several groups have created methods to examine injury, regeneration, and disease within microfluidic devices. Comparisons can be made between damaged and normal cultures, as well identification of factors that affect regeneration. A number of groups have focused their efforts on engineering the extracellular environment for better stimulation delivery or improved identification of released molecules.

While many of the devices discussed herein are good candidates for studying neurotransmission, not all of them have been applied for this purpose. One complicating factor is the requirement of having to maintain mammalian cultures outside of an incubator. Oftentimes, long-term signaling experiments take several hours and require complicated setups of syringe pumps and valve systems, combined with the need to monitor cell viability under a microscope. Performing long-term studies outside of an incubator requires that the appropriate CO2 and temperature levels for viability be maintained. Commercial or home-built incubators can be used to enclose a microfluidics setup or provide access ports for fluid entry, and a number of devices have been developed that incorporate these considerations into their design.73-76 Needed developments include more robust designs that can be applied to current neuroscience measurement and characterization approaches. As mentioned earlier, designs that readily adapt to existing techniques will facilitate their incorporation into neuroscience research laboratories.

Challenges aside, we have highlighted the substantial progress made in the implementation of microfluidics in the investigation of neurotransmission. With continued advances in device designs that improve upon traditional methods of detection, microfluidics promises to be an excellent, more widely used platform for understanding the complex nature of neurotransmission within the nervous system. While the use of microfluidics in academic laboratories is widespread, it has yet to be applied in many industrial settings. We expect this to change as these devices become more robust and readily available. Their ability to provide efficient sample preparation and be interfaced to on- or off-chip detectors are key factors driving the future of this technology.

Acknowledgements

The project described was supported by Award No. P30 DA018310 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Award No. NS031609 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, and Award No. DMI 0328162 from the National Science Foundation. C.A.C. was supported by the NIH Cellular and Molecular Biology Training Grant T32 GM007283. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the official views of the award agencies.

Biography

Jonathan Sweedler received his Ph.D. in Chemistry from the University of Arizona in 1988, spent several years at Stanford before moving to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, where he is currently the Eiszner Family Professor of Chemistry, Director of the School of Chemical Sciences, and affiliated with the Institute of Genomic Biology and the Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology. His research interests include the development of techniques for assaying complex microenvironments, new small-volume separation and detection methods, and micro/nanofluidic sampling approaches, and applying these technologies to studying novel neurochemical pathways in a cell-specific manner.

Callie Croushore is currently pursuing her Ph.D. in analytical chemistry from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She obtained her B.S. in chemistry from Westminster College in 2008. Her research is centered around the development of microfluidic devices for studying neurotransmitter release from low-density neuronal cultures with mass spectrometry detection.

References

- 1.Strand FL. In: Prog. Drug Res. Prokai L, Prokai-Tatrai K, editors. Vol. 61. 2003. pp. 1–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Querfurth HW, LaFerla FM. New Engl. J. Med. 2010;362:329–344. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0909142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dagyte G, Den Boer JA, Trentani A. Behav. Brain Res. 2011;221:574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Holmes A, Heilig M, Rupniak NMJ, Steckler T, Griebel G. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2003;24:580–588. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huot P, Fox SH, Brotchie JM. Prog. Neurobiol. 2011;95:163–212. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Perry M, Li Q, Kennedy RT. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2009;653:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.08.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson DL, Hermans A, Seipel AT, Wightman RM. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2554–2584. doi: 10.1021/cr068081q. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trouillon R, Svensson MI, Berglund EC, Cans AS, Ewing AG. Electrochim. Acta. 2012;84:84–95. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Watson CJ, Venton BJ, Kennedy RT. Anal. Chem. 2006;78:1391–1399. doi: 10.1021/ac0693722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guihen E, O’Connor WT. Electrophoresis. 2010;31:55–64. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nandi P, Lunte SM. Anal. Chim. Acta. 2009;651:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2009.07.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wightman RM. Science. 2006;311:1570–1574. doi: 10.1126/science.1120027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Perez XA, Andrews AM. Anal. Chem. 2005;77:818–826. doi: 10.1021/ac049103g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kile BM, Walsh PL, McElligott ZA, Bucher ES, Guillot TS, Salahpour A, Caron MG, Wightman RM. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2012;3:285–292. doi: 10.1021/cn200119u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rubakhin SS, Romanova EV, Nemes P, Sweedler JV. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:S20–S29. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lanni EJ, Rubakhin SS, Sweedler JV. J. Proteomics. 2012;75:5036–5051. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2012.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin Y, Trouillon R, Safina G, Ewing AG. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:4369–4392. doi: 10.1021/ac2009838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cho S, Wood A, Bowlby MR. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2007;5:19–33. doi: 10.2174/157015907780077105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang Y, Williams JC, Johnson SM. Lab Chip. 2012;12:2103–2117. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21142d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor AM, Jeon NL. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2010;20:640–647. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang J, Ren L, Li L, Liu W, Zhou J, Yu W, Tong D, Chen S. Lab Chip. 2009;9:644–652. doi: 10.1039/b813495b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.E Leclerc, Sakai Y, Fujii T. Biotechnol. Prog. 2004;20:750–755. doi: 10.1021/bp0300568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Taylor AM, Blurton-Jones M, Rhee SW, Cribbs DH, Cotman CW, Jeon NL. Nat. Methods. 2005;2:599–605. doi: 10.1038/nmeth777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hung PJ, Lee PJ, Sabounchi P, Lin R, Lee LP. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2005;89:1–8. doi: 10.1002/bit.20289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Millet LJ, Stewart ME, Nuzzo RG, Gillette MU. Lab Chip. 2010;10:1525–1535. doi: 10.1039/c001552k. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Romanova EV, Fosser KA, Rubakhin SS, Nuzzo RG, Sweedler JV. FASEB J. 2004;18:1267–1269. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1368fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hanson JN, Motala MJ, Heien ML, Gillette M, Sweedler J, Nuzzo RG. Lab Chip. 2009;9:122–131. doi: 10.1039/b803595d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Falconnet D, Csucs G, Michelle Grandin H, Textor M. Biomaterials. 2006;27:3044–3063. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Unger MA, Chou HP, Thorsen T, Scherer A, Quake SR. Science. 2000;288:113–116. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5463.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shaikh KA, Ryu KS, Goluch ED, Nam JM, Liu J, Thaxton CS, Chiesl TN, Barron AE, Lu Y, Mirkin CA, Liu C. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2005;102:9745–9750. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504082102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharp T, Zetterström T, Westerink BHC, Cremers TIFH. Handbook of Behavioral Neuroscience. Vol. 16. Elsevier; 2006. pp. 5–16. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uchiyama K, Nakajima H, Hobo T. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2004;379:375–382. doi: 10.1007/s00216-004-2616-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nandi P, Desai DP, Lunte SM. Electrophoresis. 2010;31:1414–1422. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang M, Roman GT, Perry ML, Kennedy RT. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:9072–9078. doi: 10.1021/ac901731v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Song P, Hershey ND, Mabrouk OS, Slaney TR, Kennedy RT. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:4659–4664. doi: 10.1021/ac301203m. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Patterson EE, Pritchett JS, Shippy SA. Analyst. 2009;134:401–406. doi: 10.1039/b813887g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slaney TR, Nie J, Hershey ND, Thwar PK, Linderman J, Burns MA, Kennedy RT. Anal. Chem. 2011;83:5207–5213. doi: 10.1021/ac2003938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen D, Du W, Liu Y, Liu W, Kuznetsov A, Mendez FE, Philipson LH, Ismagilov RF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:16843–16848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807916105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Millet LJ, Bora A, Sweedler JV, Gillette MU. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2010;1:36–48. doi: 10.1021/cn9000022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Millet LJ, Stewart ME, Sweedler JV, Nuzzo RG, Gillette MU. Lab Chip. 2007;7:987–994. doi: 10.1039/b705266a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Taylor AM, Dieterich DC, Ito HT, Kim SA, Schuman EM. Neuron. 2010;66:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tourovskaia A, Figueroa-Masot X, Folch A. Lab Chip. 2005;5:14–19. doi: 10.1039/b405719h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tourovskaia A, Figueroa-Masot X, Folch A. Nat. Protoc. 2006;1:1092–1104. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor AM, Jeon NL. Crit. Rev. Biomed. Eng. 2011;39:185–200. doi: 10.1615/critrevbiomedeng.v39.i3.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Regehr KJ, Domenech M, Koepsel JT, Carver KC, Ellison-Zelski SJ, Murphy WL, Schuler LA, Alarid ET, Beebe DJ. Lab Chip. 2009;9:2132–2139. doi: 10.1039/b903043c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Toepke MW, Beebe DJ. Lab Chip. 2006;6:1484–1486. doi: 10.1039/b612140c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhong M, Lee CY, Croushore CA, Sweedler JV. Lab Chip. 2012;12:2037–2045. doi: 10.1039/c2lc21085a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van Midwoud PM, Janse A, Merema MT, Groothuis GMM, Verpoorte E. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:3938–3944. doi: 10.1021/ac300771z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang JD, Douville NJ, Takayama S, ElSayed M. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2012:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0562-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ludwig M, Leng G. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2006;7:126–136. doi: 10.1038/nrn1845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rajagopal C, Mains RE, Eipper BA. Crit. Rev. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2012;47:391–406. doi: 10.3109/10409238.2012.694845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ludwig M, Pittman QJ. Trends Neurosci. 2003;26:255–261. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(03)00072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fields RD, Stevens-Graham B. Science. 2002;298:556–562. doi: 10.1126/science.298.5593.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hosmane S, Yang IH, Ruffin A, Thakor N, Venkatesan A. Lab Chip. 2010;10:741–747. doi: 10.1039/b918640a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Majumdar D, Gao Y, Li D, Webb DJ. J. Neurosci. Methods. 2011;196:38–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kunze A, Meissner R, Brando S, Renaud P. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2011;108:2241–2245. doi: 10.1002/bit.23128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hellman AN, Vahidi B, Kim HJ, Mismar W, Steward O, Jeon NL, Venugopalan V. Lab Chip. 2010;10:2083–2092. doi: 10.1039/b927153h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hosmane S, Fournier A, Wright R, Rajbhandari L, Siddique R, Yang IH, Ramesh KT, Venkatesan A, Thakor N. Lab Chip. 2011;11:3888–3895. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20549h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sabounchi P, Ionescu-Zanetti C, Chen R, Karandikar M, Seo J, Lee LP. Appl. Phys. Lett. 2006;88:183901. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Croushore CA, Supharoek S, Lee CY, Jakmunee J, Sweedler JV. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:9446–9452. doi: 10.1021/ac302283u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Gähwiler BH, Capogna M, Debanne D, McKinney RA, Thompson SM. Trends Neurosci. 1997;20:471–477. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(97)01122-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mohammed JS, Caicedo HH, Fall CP, Eddington DT. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1048–1055. doi: 10.1039/b802037j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tang YT, Kim J, López-Valdés HE, Brennan KC, Ju YS. Lab Chip. 2011;11:2247–2254. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20197b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wei H, Li H, Gao D, Lin JM. Analyst. 2010;135:2043–2050. doi: 10.1039/c0an00162g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jo K, Heien ML, Thompson LB, Zhong M, Nuzzo RG, Sweedler JV. Lab Chip. 2007;7:1454–1460. doi: 10.1039/b706940e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dishinger JF, Reid KR, Kennedy RT. Anal. Chem. 2009;81:3119–3127. doi: 10.1021/ac900109t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gao Y, Bhattacharya S, Chen X, Barizuddin S, Gangopadhyay S, Gillis KD. Lab Chip. 2009;9:3442–3446. doi: 10.1039/b913216c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Enders JR, Marasco CC, Kole A, Nguyen B, Sevugarajan S, Seale KT, Wikswo JP, McLean JA. IET Systems Biology. 2010;4:416–427. doi: 10.1049/iet-syb.2010.0012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li MW, Spence DM, Martin RS. Electroanal. 2005;17:1171–1180. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bowen AL, Martin RS. Electrophoresis. 2010;31:2534–2540. doi: 10.1002/elps.201000029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Halpin ST, Spence DM. Anal. Chem. 2010;82:7492–7497. doi: 10.1021/ac101130s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Amatore C, Arbault S, Chen Y, Crozatier C, Tapsoba I. Lab Chip. 2007;7:233–238. doi: 10.1039/b611569a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hung PJ, Lee PJ, Sabounchi P, Aghdam N, Lin R, Lee LP. Lab Chip. 2005;5:44–48. doi: 10.1039/b410743h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Forry SP, Locascio LE. Lab Chip. 2011;11:4041–4046. doi: 10.1039/c1lc20505f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Skafte-Pedersen P, Hemmingsen M, Sabourin D, Blaga FS, Bruus H, Dufva M. Biomed. Microdevices. 2012;14:385–399. doi: 10.1007/s10544-011-9615-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kim YT, Karthikeyan K, Chirvi S, Dave DP. Lab Chip. 2009;9:2576–2581. doi: 10.1039/b903720a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]