Abstract

Regulatory programs that control the specification of serotonergic neurons have been investigated by genetic mutant screens in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Loss of a previously uncloned gene, ham-3, affects migration and serotonin antibody staining of the hermaphrodite-specific neuron (HSN) pair. We characterize these defects here in more detail, showing that the defects in serotonin antibody staining are paralleled by a loss of the transcription of all genes involved in serotonin synthesis and transport. This loss is specific to the HSN class as other serotonergic neurons appear to differentiate normally in ham-3 null mutants. Besides failing to migrate appropriately, the HSNs also display axon pathfinding defects in ham-3 mutants. However, the HSNs are still generated and express a subset of their terminal differentiation features in ham-3 null mutants, demonstrating that ham-3 is a specific regulator of select features of the HSNs. We show that ham-3 codes for the C. elegans ortholog of human BAF60, Drosophila Bap60, and yeast Swp73/Rsc6, which are subunits of the yeast SWI/SNF and vertebrate BAF chromatin remodeling complex. We show that the effect of ham-3 on serotonergic fate can be explained by ham-3 regulating the expression of the Spalt/SALL-type Zn finger transcription factor sem-4, a previously identified regulator of serotonin expression in HSNs and of the ham-2 Zn transcription factor, a previously identified regulator of HSN migration and axon outgrowth. Our findings provide the first evidence for the involvement of the BAF complex in the acquisition of terminal neuronal identity and constitute genetic proof by germline knockout that a BAF complex component can have cell-type-specific roles during development.

Keywords: C. elegans, chromatin remodeling, neuronal development

NEURONS that express the neurotransmitter serotonin fulfill a number of critical functions in all nervous systems examined to date. In vertebrates, serotonergic neurons modulate anxiety, cognitive processes, mood, body temperature, sleep, sexual behavior, appetite, and metabolism, and their dysfunction has been connected to a variety of human disorders (Muller and Jacobs 2010). In the hermaphroditic Caenorhabditis elegans nervous system, serotonin also controls a number of distinct behaviors (Schafer 2005; Chase and Koelle 2007). Serotonin is utilized as a neurotransmitter under normal conditions by seven neuron types, the sensory neuron ADF; the interneurons AIM and RIH; the motor neurons hermaphrodite-specific neurons (HSNs), the ventral cord motor neurons VC4 and VC5; and the neurosecretory NSM cells (Schafer 2005; Chase and Koelle 2007). Under stress conditions, serotonin is used by an additional neuron type, ASG (Pocock and Hobert 2010). One of the serotonergic neurons, the hermaphrodite-specific motor neuron, HSN, utilizes serotonin to signal to vulval muscles to control egg-laying behavior (Schafer 2005). Unlike most other neurons in the C. elegans nervous system, the two bilaterally symmetric HSNs undergo long-range migration. After terminating migration, they extend their axons postembryonically in a highly stereotyped pattern along the ventral nerve cord into the nerve ring (White et al. 1986).

The ability to easily visualize HSN migration, morphology, serotonin expression, axon outgrowth, and functional output (i.e., egg laying) has prompted large-scale genetic mutant screens in which these features are disrupted (Trent et al. 1983; Desai et al. 1988; Desai and Horvitz 1989). These mutant analyses revealed genes that are involved in controlling multiple aspects of HSN development and function, and genes that control only a select number of HSN features (Desai et al. 1988) (Table 1). For example, the egl-5 HOX cluster gene controls all known aspects of HSN development and function, while the unc-86 POU homeobox and sem-4 Zn finger transcription factor control serotonin expression and axon pathfinding, but not neuronal migration (Basson and Horvitz 1996; Sze et al. 2002). Conversely, the ham-2 Zn finger transcription factor controls HSN migration, but not serotonin expression (Baum et al. 1999). Migratory phenotypes can be further genetically separated. In animals lacking ham-2 or egl-43 (another Zn finger transcription factor) (Garriga et al. 1993), the HSNs fail to reach their correct position in the midbody region, while in animals lacking egl-44 (a TEF-type transcription factor) (Wu et al. 2001) or egl-46 (another Zn finger transcription factor) (Wu et al. 2001), HSNs migrate beyond their normal position.

Table 1. Comparing role of gene regulatory factors in hermaphrodite-specific neuron (HSN) development.

| Mutant gene |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phenotype | egl-5 HOX | egl-43 Zn | egl-44 TEF | egl-46 Zn | unc-86 POU-HD | sem-4 Zn | ham-2 Zn | ham-3 |

| Completing migration | − | − | + | + | + | + | − | − |

| Terminating migration | ? | ? | − | − | + | + | ? | − |

| Axonal pathfinding | − | − | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Expressing serotonin | − | + | − | − | − | − | + | − |

| Hood formation | − | + | + | + | − | − | + | + |

| Sex-specific survival | − | + | + | + | + | + | + | ? |

−, defective; +, like wild type; ?, not examined; HOX, Hox transcription factor; Zn, zinc finger transcription factor; POU-HD, POU homeodomain transcription factor. All data shown here is from Desai et al. 1988 with the exception of the ham-3 axon pathfinding defects, which are described in this paper for the first time and with the exception of ham-2, which was originally reported to affect serotonin expression (Desai et al. 1988); closer inspection revealed this not to be the case (Baum et al. 1999). Not shown is another transcription factor, zag-1, with mutant phenotypes very similar to that of unc-86 and sem-4 (Clark and Chiu 2003).

ham-3 mutants were retrieved from previous screens for mutants affecting HSN development but the molecular lesion in ham-3 mutants has not yet been molecularly identified (Desai et al. 1988). ham-3 mutant animals show abnormal HSN migration (hence “ham” for HSN abnormal migration), an egg-laying defect and loss of serotonin antibody staining in the HSNs (Desai et al. 1988). However, within their cell bodies HSNs still form a characteristic hood structure in ham-3 mutants, a sign of morphological maturation (Desai et al. 1988). Axon pathfinding could not be examined due to the loss of serotonin staining (and resulting loss of the ability to visualize axons) in the HSNs. No other mutant isolated from previous screens showed a similar combination of phenotypes (Table 1), which prompted our interest in studying ham-3 in more detail.

Phenotypic analysis of ham-3 mutants reveals neuronal defects

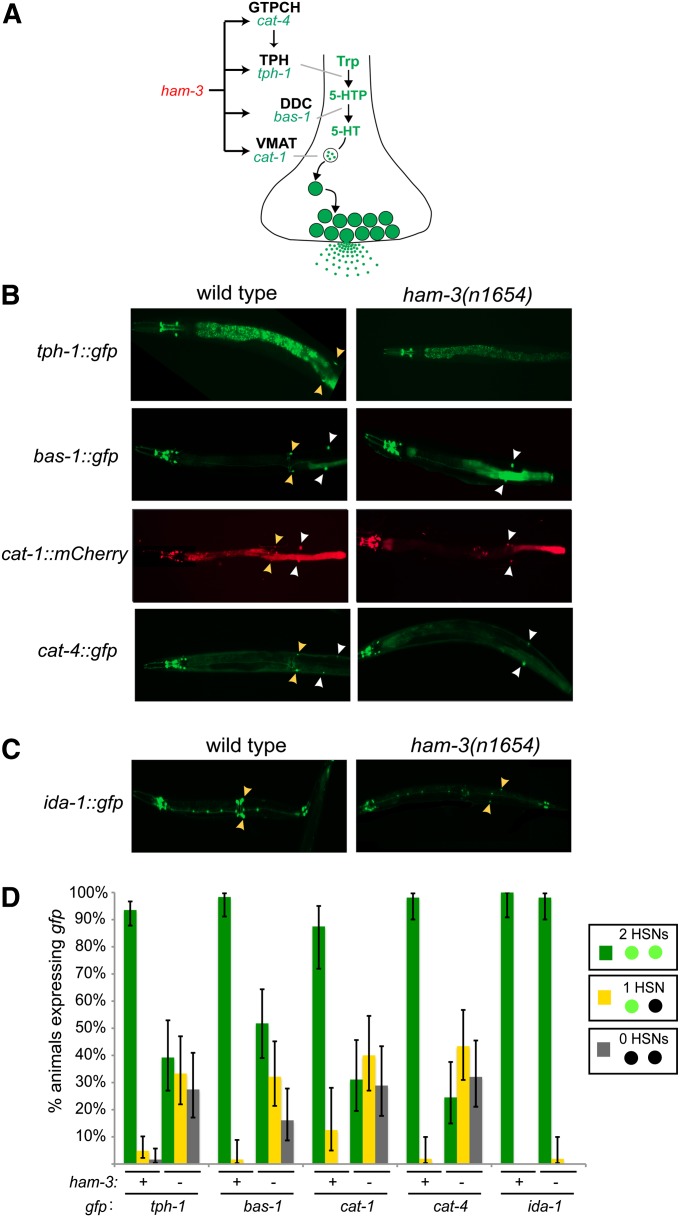

As a first step to a more detailed analysis of ham-3(n1654) mutant animals, we focused on the lack of serotonin antibody staining in the HSNs of ham-3 mutants that has been previously reported (Desai et al. 1988). Such a phenotype could be due to loss of expression of the rate limiting enzyme in the biosynthesis of serotonin, tryptophan hydroxylase, encoded by the tph-1 locus in C. elegans (Sze et al. 2000). We examined the expression of a tph-1::gfp reporter gene in ham-3 mutant animals and found tph-1::gfp expression to be severely affected (Figure 1). Expression was affected only in the HSNs, not in any other tph-1-expressing cell.

Figure 1.

ham-3 affects expression of the entire serotonin pathway. (A) Schematic representation of the serotonin biosynthetic pathway. (B) HSN expression of tph-1, cat-1, cat-4, and bas-1 reporters are affected in ham-3(n1654) mutants. Yellow arrowheads point to the serotonergic HSNs and white arrowhead point to the dopaminergic PDE neurons, which are also labeled with several of the markers used. (C) Expression of an ida-1 reporter construct is unaffected in ham-3(n1654) animals. (D) Quantification of defects. Error bars are 95% confidence interval of the proportion. Sample sizes range from n = 32 to n = 124. See File S1 for information on transgenes.

We next examined whether the expression of other components of the pathway required for synthesis and transport of serotonin were also affected (this pathway is shown in Figure 1A). We examined the expression of bas-1, which codes for the aromatic amino acid decarboxylase that converts the TPH-1 product 5-hydroxytryptophan to serotonin (Hare and Loer 2004), the cat-4 gene, which is required to generate a co-factor for TPH-1, and the vesicular monoamine transporter encoded by cat-1 (Duerr et al. 1999) (note that the serotonin reuptake transporter mod-5 is not expressed in HSN) (Jafari et al. 2011). We found that expression of the entire serotonin pathway is strongly affected in the HSNs of ham-3(n1654) mutants (Figure 1, B and D). Expression of these genes in other serotonergic neurons is not affected (Figure 1B).

Given the striking defects in neurotransmitter synthesis and transport, we next examined whether other signaling features not directly related to the serotonin pathway, such as components of the machinery required for neuropeptide signaling, are affected by ham-3. The HSNs are known to express several neuropeptides and the machinery involved in neuropeptide release (Li and Kim 2008). Specifically, we examined expression of the ida-1 gene, a phosphatase that is involved in neuropeptidergic dense core vesicle biology (Zahn et al. 2001). We found that ida-1 expression is largely unaffected in ham-3(n1654) mutants (Figure 1, C and D). This is not because there is residual ham-3 activity in n1654 animals; n1654 is a null allele, as we will show below.

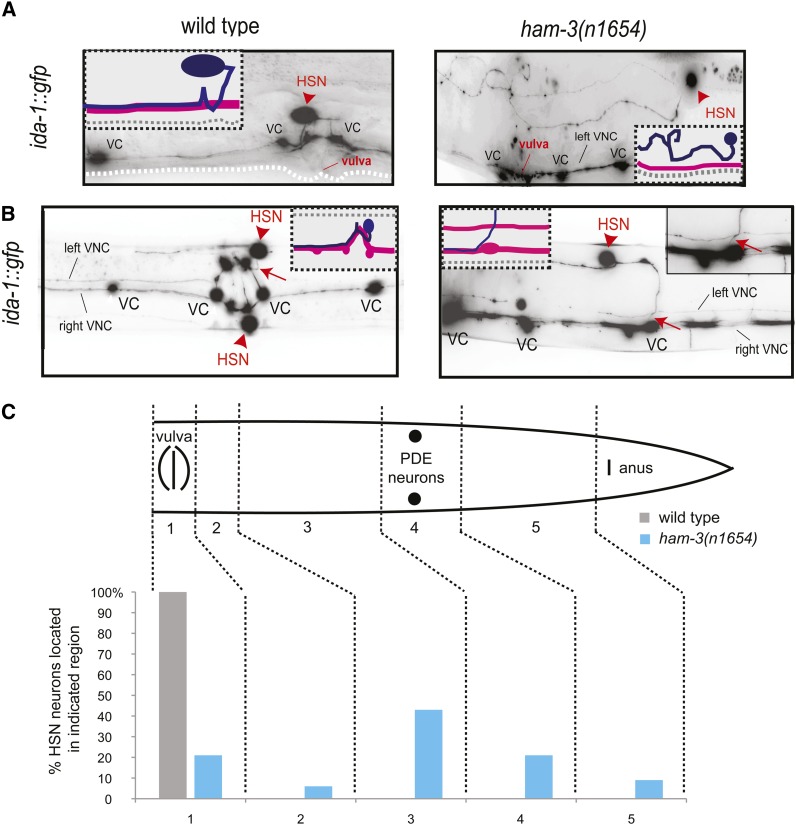

We next examined the HSN migration defects in ham-3 mutants. Abnormal HSN migration patterns are already apparent in ham-3(n1654) animals that still maintain expression of serotonin pathway genes, as previously reported (Desai et al. 1988), but the migratory patterns of the cells not expressing serotonin have not previously been examined. Since ida-1 expression was unaffected in ham-3 mutant animals, we used ida-1::gfp-labeled animals to precisely score HSN migration. We find severe migration defects, with either one or both HSNs failing to migrate properly to their final position near the vulva. Mismigrated HSNs tend to stop in specific zones in the posterior of the animal, with the majority (∼40% of HSNs) prematurely terminating migration between the postdeirid and the vulva (Figure 2, A and C). Overall, 94% of mutant animals examined show a migration defect in at least one HSN (n = 70).

Figure 2.

HSN migration and axon pathfinding in ham-3 mutants. HSN migration and axon pathfinding were scored with an ida-1::gfp transgene in ham-3(n1654) mutant animals. Images in A and B are inverted to sharpen the contrast for viewing axons. (A) HSN migration. Lateral view of an adult in the midbody region around the vulva. Red arrowheads indicate HSN cell body. Insets depict schematized HSN axon migration path. Note the aberrant position of the HSN cell body relative to the indicated vulva. (B) HSN axon pathfinding along midline. Ventral view of an adult in the midbody region. Red arrowheads indicate HSN cell body. Red arrow indicates HSN axon joining the left ventral nerve cord (VNC) in wild-type animals and aberrantly joining the opposite VNC fascicle in ham-3(n1654) animals. Insets depict schematized HSN axon path. (C) Quantification of migration defects. A schematic of the posterior half of a worm is shown, partitioned by region. The cell body left position (HSNL) and right position (HSNR) were scored in wild-type and ham-3(n1654) mutant animals and the number of HSNL or HSNR in any of the indicated regions is shown.

The intact expression of ida-1::gfp expression in ham-3 mutants also enabled us to score HSN axon pathfinding, a feature that has not previously been examined in ham-3 mutants. We find a number of distinct defects in axon migration. In the most extreme cases, the axon appears to wander back and forth in search of the vulva, never reaching its target. In other cases, the axon fails to proceed ventrally from the HSN cell body and does not synapse onto the vulval muscles, instead proceeding directly to the nerve ring. Overall, we find that 34% of ham-3(n1654) mutant animals possess HSN axons that fail to reach their synaptic targets in the vulval muscles. Once in the ventral nerve cord, HSN axons make frequent errors in respecting the midline structure. A total of 30% of animals (n = 86) show axons that have aberrantly crossed the midline (Figure 2B). Cell migration and axonal defects are not obligatorily linked. Of the 47 cases where we found HSNs to have migrated correctly, seven HSNs still make axon pathfinding errors.

ida-1::gfp also labels the VC class of ventral cord motor neurons, two of which (VC4 and VC5) are serotonergic. A total of 43% of ham-3 mutant animals show fasciculation defects of the VC neurons (n = 141; wild-type animals never show this defect; n = 102). Axon guidance defects of ventral nerve cord interneurons have also been detected upon reduction of ham-3 by RNAi in a chromosome-wide RNAi screen (Schmitz et al. 2007).

Three other neuronal cell types undergo long-range migrations in C. elegans, namely the CAN and ALM neurons (which migrate embryonically) and the Q neuroblasts (which migrate postembryonically). After terminating migration, the Q neuroblasts will generate touch receptor neurons. We find that ham-3 affects CAN cell migration, as assessed with a kal-1::gfp reporter transgene. In 53% of animals, we observe CAN cells with overmigration defects, (n = 94) while only 12% of control animals show this defect (n = 107). This overmigration of the CAN is correlated with HSN mismigration in ham-3(n1654); kal-1::gfp animals, but the converse is not necessarily true. While all of the scoreable animals with a CAN that migrate past the vulva also show defects in HSN migration, only 80% (61/76) of animals with mismigrated HSNs also show CAN migration defects. In contrast to the embryonic CAN and HSN migration defects, the postembryonic migration of the Q neuroblasts is not affected, as assessed with a mec-3::gfp reporter transgene that visualizes the ALM and AVM and PVM, the touch neuron descendants of the Q neuroblasts.

We also examined whether ham-3 may affect the development of the HSN sister cell, the PHB sensory neuron. The development of this neuron is affected in another ham mutant, ham-1, which is required for asymmetric cell division (Guenther and Garriga 1996). Through dye filling and examining the expression of ida-1::gfp, we find that PHB neurons appear normal in ham-3 mutants (n = 25).

ham-3 encodes an ortholog of the BAF60 subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex

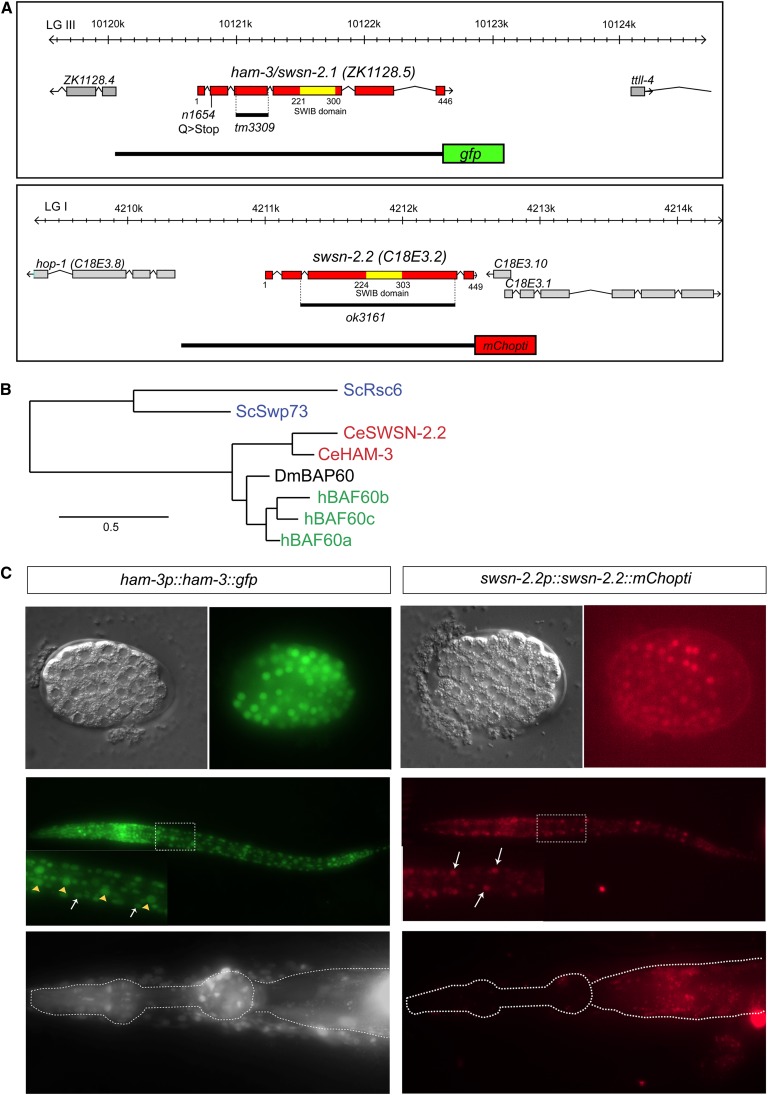

ham-3(n1654) was mapped by conventional three-factor mapping between unc-32 and dpy-18 on LGIII, which corresponds to a 2.5-Mb physical interval. Whole genome sequencing and ensuing sequence analysis using MAQGene (Bigelow et al. 2009) revealed only two sequence variants in this interval that are predicted to change protein coding sequences, a nonsense mutation in ZK1128.5 (previously called tag-246 or swsn-2.1) (Figure 3A), and a missense mutation in bbs-5. Animals carrying a deletion allele of ZK1128.5, tm3309 (kindly provided by Shohei Mitani, Tokyo Women's Medical University School of Medicine, Tokyo, Japan), display a similar HSN phenotype as ham-3(n1654) mutant animals (supporting information, Table S1). RNAi of ZK1128.5 also produced a ham-3 like phenotype (30% of tph-1::gfp-expressing animals show a migration defect, compared to 11% of wild-type controls; n = 33 and 124, respectively). Moreover, the serotonin-deficient phenotype of ham-3(n1654) mutant animals can be rescued with a fosmid, WRM0626dF04, that covers ZK1128.5, but not bbs-5 (Table S1). We conclude that ZK1128.5/tag-246/swsn-2.1 corresponds to ham-3.

Figure 3.

The C. elegans genome encodes two broadly but differentially expressed BAF60/Bap60 orthologs. (A) The ham-3 and swsn-2.2 loci, mutant alleles and reporter gene constructs. Reporter constructs were generated by PCR fusion (Hobert 2002). (B) The BAF60 family in yeast, worms, flies, and humans. The phylogenetic tree was generated at www.phylogeny.fr using default parameters. (C) Animals expressing reporter constructs. ham-3 and swsn-2.2 reporter expression is first observed after gastrulation (top), where expression is broad. Expression of both reporters persists into the first larval stages (middle). In the adult (bottom) expression of ham-3, but not swsn-2.2, persists. Red signals in the adult swsn-2.2 reporter worms are gut autofluorescence. Three independent lines of each reporter construct show similar expression pattern. Sample sizes range from n = 131 to n = 204. See File S1 for information on transgenes.

ham-3 is one of two C. elegans orthologs of human BAF60 proteins (Figure 3B). Humans contain three BAF60 paralogs, BAF60a, -b, and -c. BAF60 proteins are a component of an ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling complex, called SWI/SNF in yeast or BAF in vertebrates (Wang et al. 1996; Yoo and Crabtree 2009). This complex mobilizes nucleosomes both by sliding and by catalyzing the ejection and insertion of histone octamers (Wilson and Roberts 2011). A reconstituted human complex lacking the BAF60 subunit shows full remodeling activity, suggesting that BAF60 is not essential for the core remodeling function of the BAF complex (Phelan et al. 1999). Rather, based on its physical interaction with various transcription factors, the BAF60 subunit is thought to be involved in the recruitment of the BAF complex to specific transcription factors (Sudarsanam and Winston 2000). In vertebrates, the three BAF60 homologs, BAF60a, BAF60b, and BAF60c, are each tissue-specifically expressed (Wang et al. 1996). No germline knockout of any BAF60 gene has been described in vertebrates, but RNAi of BAF60c affects heart development (Lickert et al. 2004). The fly BAF60 ortholog Bap60 is a haploinsufficient, essential gene, since the elimination a single copy of the locus results in lethality, but the cause of lethality is not known (Moller et al. 2005).

The early stop codon of ham-3(n1654) animals suggests that the allele is a molecular null allele. At 15° and 20°, both ham-3(n1654) and the deletion allele ham-3(tm3309) are viable and display roughly similar HSN phenotypes (Table S1). However, we find that when shifted to 25° at any time in their life cycle, both ham-3(n1654) and ham-3(tm3309) animals will die within a few hours for unknown reasons. This argues that ham-3 is required for viability only under specific circumstances. In other words, ham-3 somehow buffers animals from what is an apparently detrimental effect of elevated temperatures.

Like vertebrates, but unlike flies, the C. elegans genome contains more than one BAF60 ortholog (Figure 3B). The ham-3 paralog, swsn-2.2, is located on a different chromosome and its protein product is 66.8% identical in amino acid sequence to HAM-3. The degree of similarity between the ham-3 and swsn-2.2 paralogs is comparable to the similarity between human BAF60 paralogs (BAF60a vs. BAF60b: 59.8% identical; BAF60b vs. BAF60c: 60.4% identical). The ham-3 and swsn-2.2 paralogs are not orthologs of specific BAF60 subunits but have duplicated independently of the duplication in the vertebrate lineage (Figure 3B).

There are two very distant relatives of the ham-3 and swsn-2.2 genes in the C. elegans genome. One is the uncharacterized T24G10.2 gene, which is the only other gene in the C. elegans genome besides ham-3 and swsn-2.2 that contains a SWIB domain (for SWI/SNF complex B; IPR019835), an ancient chromatin-associated domain of unknown function. However, T24G10.2 has acquired an additional domain, a DEK–C-terminal domain (IPR014876) and this domain combination is unique to flies and worms. The other distant ham-3/swsn-2.2 homolog is the K03B8.4 gene, which codes for small protein of 96 amino acids (HAM-3 and SWSN-2.2 are >400 amino acids) that shows high sequence homology to the C-terminal ends of HAM-3 and SWSN-2.2, past the respective SWIB domains. K03B8.4 orthologs cannot be found in other currently sequenced nematode genome sequences and the gene may be a remnant of a C. elegans-specific partial gene duplication event. We conclude that based on sequence relation ham-3 and swsn-2.2 are likely the only genes in the C. elegans genome that act as BAF60-like BAF complex components.

The ham-3 paralog swsn-2.2 is an essential gene

The ham-3 paralog swsn-2.2 has not been characterized to date. We obtained a deletion allele of swsn-2.2, ok3161, from the C. elegans knockout consortium. ok3161 eliminates most of the gene (Figure 3A). Animals carrying this allele are not homozygous viable. The swsn-2.2(ok3161) lethality can be rescued with a segment of genomic DNA that contains exclusively the swsn-2.2 locus (construct shown in Figure 3A). Null mutant animals that have not received the extrachromosomal array from their parents arrest at the first larval stage for unknown reasons. The HSNs have normally migrated in these arrested animals. Since serotonin pathway genes are not normally expressed at this time point in the HSNs, we could not easily assess serotonergic differentiation of the HSNs in these mutant animals. swsn-2.2(RNAi) does not result in HSN phenotypes and swsn-2.2(RNAi) in a ham-3(n1654) mutant background does not enhance the ham-3(n1654) HSN phenotypes in a notable manner.

The two BAF60 orthologs ham-3 and swsn-2.2 are broadly expressed

To compare ham-3 expression with the tissue-specific expression pattern of BAF60 paralogs in vertebrates (Wang et al. 1996) and in flies, where Bap60 expression is restricted to the ventral nerve cord and the brain (Moller et al. 2005), we generated reporter constructs for ham-3 and its paralog, swsn-2.2. Both constructs are translational fusions in which the entire intergenic region and all exons and introns are fused to a gfp reporter (Figure 3A). Expression patterns of each reporter were similar over three independent lines. By crossing one line each into ham-3 or swsn-2.2 mutant backgrounds, respectively, we confirmed that each reporter line rescues the respective mutant phenotype.

ham-3::gfp animals show broad gfp expression starting at gastrulation and persisting through larval and adult stages (Figure 3C) in what appear to be all cells of the worm, including HSNs. swsn-2.2::mChOpti expression also commences at gastrulation (Figure 3C), but its expression appears more restricted. In the first larval stage, expression can be observed in all tissues (including HSNs) with the prominent exception of the intestine (Figure 3C). Expression of swsn-2.2::mChOpti fades during larval stages and is no longer observed in adult animals (Figure 3C).

Comparing phenotypes of C. elegans SWI/SNF mutants

C. elegans homologs of several core components of the SWI/SNF complex were previously analyzed in C. elegans and shown to be required for asymmetric cell division, gonad and vulval development, and early embryonic morphogenesis (Sawa et al. 2000; Cui et al. 2004; Shibata et al. 2012). Complete removal of core SWI/SNF complex components (psa-4/Brahma, psa-1/Moira/BAF155, snfc-5/BAF47, swsn-6/BAF53, swsn-3/BAF57) results in sterility or embryonic lethality. Viable, hypomorphic alleles of the Brahma/Brg1 homolog psa-4 or the BAF155/SRG3/Moira homolog psa-1 display HSN migration defects (22–26% penetrant; n > 53), but no significant defects in tph-1 or cat-4 expression (n > 53), possibly due to the hypomorphic activity of these genes.

swsn-7/BAF200 and let-526/BAF250 are defining components of two different types of BAF complexes, called the PBAF and BAF complexes, respectively (Hargreaves and Crabtree 2011). let-526/BAF250 null mutant animals die at the first larval stage, preventing the analysis of serotonergic phenotypes in the HSN (which is expressed only later in larval development). However, in 4/29 let-526(gk816) arrested L1 larvae, we observed mismigrated HSNs (marker: kal-1::gfp) and in 15/29 animals we were not able to observe kal-1-expressing HSNs, either because the marker fails to be expressed or because kal-1-expressing HSNs have failed to migrate out of the tail region where they cannot be distinguished from other kal-1-expressing neurons. We also examined swsn-7(gk1041) homozygous deletion mutants derived from heterozygous parents. 27% of those animals (n = 44) show defects in HSN migration. Because of potential issues of maternal rescue and the inability to score HSN in more detail in these mutants, a specific role of the BAF vs. the PBAF complexes in HSN development cannot yet be firmly concluded.

We next examined whether ham-3 mutants display three specific non-HSN phenotypes shared by core BAF/psa hypomorphic alleles—a phasmid socket absent (Psa) phenotype (Sawa et al. 2000), a Pvl phenotype (Cui et al. 2004), and a gonad migration phenotype (Shibata et al. 2012). We find that ham-3(n1654) animals only show a 1% penetrant Psa phenotype (n = 226; wild-type animals show no such phenotype) (Sawa et al. 2000). This is significantly less than core SWI/SNF components (e.g., even a hypomorphic allele of psa-1 shows a 74% penetrant phenotype) (Sawa et al. 2000). Like psa-1 and psa-4 mutants, ham-3(n1654) mutants also display a Pvl phenotype (26%; n = 107), but again to a lesser degree (psa-1 mutants display a 100% penetrant Pvl phenotype; Cui et al. 2004). In addition, ham-3(n1654) mutants show abnormal folding and/or overmigration of the gonad arms (18 and 47%, respectively, n = 38; no such defect was observed in the wild type, n = 28). This is comparable in penetrance to the previously reported psa-1 phenotype (52% penetrant; Cui et al. 2004). However, ham-3(n1654) animals show no “missing gonad arm” phenotype previously observed upon loss of other SWI/SNF complex components (Shibata et al. 2012). The observation that ham-3 null mutants do not phenocopy the complete spectrum of SWI/SNF complex components suggests that for specific cellular functions ham-3 is not required and that its paralog swsn-2.2 may rather be a component of the SWI/SNF complex in such instances. Given the early larval arrest phenotype of swsn-2.2 mutants, we cannot readily assess these postembryonic phenotypes in swsn-2.2 mutants.

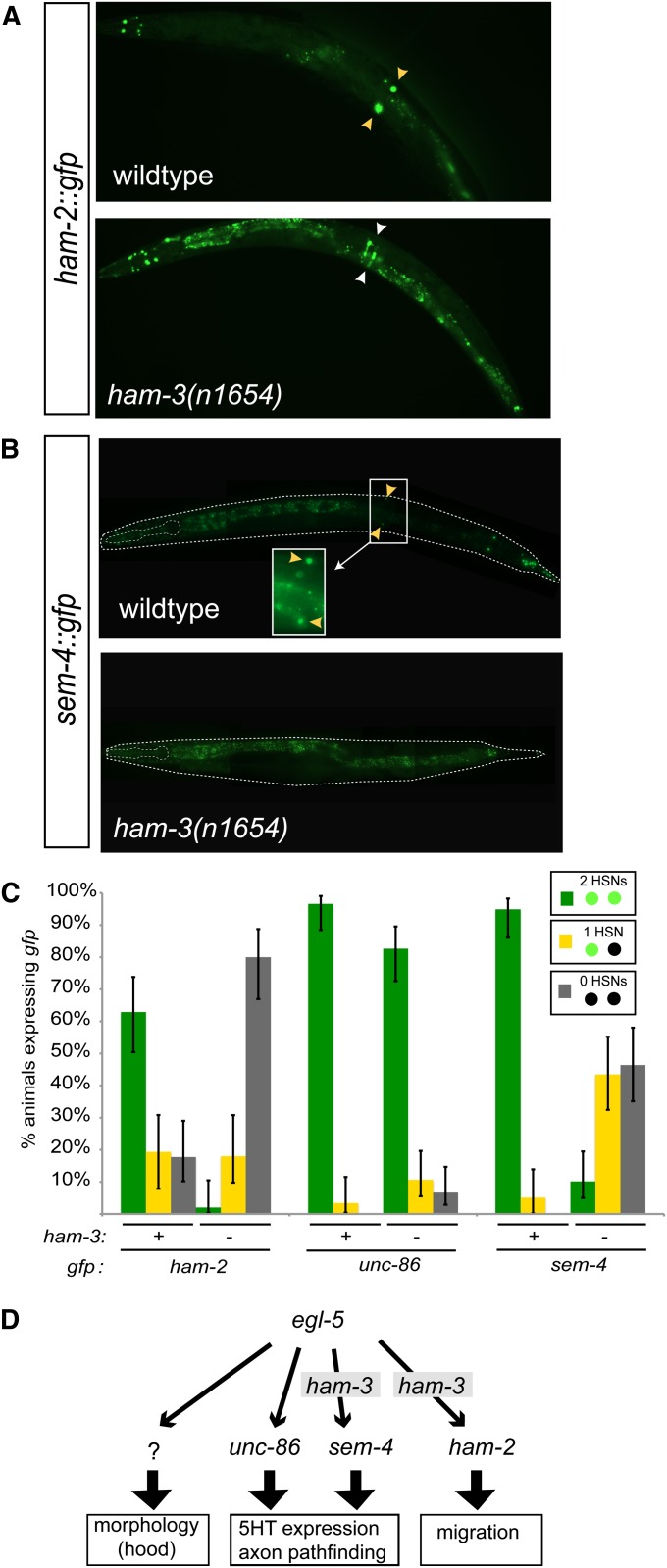

ham-3 regulates the expression of transcription factors known to be required for HSN development

To examine how ham-3 may affect HSN development, we asked how its function relates to the function of other transcription factors known to be involved in various aspects of HSN development (Table 1). We focused on transcription factors that have been previously shown to display either all or a subset of the ham-3 phenotypes (Table 1): unc-86, a Brn3-type POU homeobox gene (Finney et al. 1988); sem-4, a Spalt/SALL-type Zn finger transcription factor (Basson and Horvitz 1996); and ham-2, a member of a divergent C2H2 Zn finger family that expanded specifically in C.elegans (Baum et al. 1999; Zhang et al. 2011). unc-86 and sem-4 are known to be required for expression of serotonin in HSN, but not for HSN migration (Desai et al. 1988; Basson and Horvitz 1996; Sze et al. 2002), and ham-2 is known to be required for HSN migration, but not serotonin pathway expression (Baum et al. 1999). We find that the expression of sem-4 and ham-2 expression is strongly defective in the HSNs of ham-3(n1654) mutants, while unc-86 expression is barely affected (Figure 4, A–C). These results suggest that the specific phenotypes of ham-3 mutants may be explained through the loss of expression of the two Zn finger transcription factors ham-2 and sem-4.

Figure 4.

ham-3 affects expression of the transcription factors sem-4, unc-86, and ham-2. (A and B) sem-4, unc-86, and ham-2 reporter gene constructs expressed in wild-type and ham-3(n1654) mutant animals. Yellow arrowheads point to the HSN and white arrowheads point to ham-2 expression in the vulval epithelium. See File S1 for information on transgenes. (C) Quantification of defects. Error bars are 95% confidence interval of the proportion. Sample sizes range from n = 50 to n = 75. (D) Data summary depicting the relation of ham-3 with transcriptional regulatory events during HSN development. Arrows denote genetic activities, not necessarily direct physical interactions. See text for details.

BAF complexes are recruited to DNA via association with specific transcription factors. The respective BAF60 subunit present in the BAF complex appears to be a commonly employed recruiter via its direct interaction with specific transcription factors (Ito et al. 2001; Hsiao et al. 2003; Debril et al. 2004; Takeuchi et al. 2007; Li et al. 2008; Oh et al. 2008; Chen et al. 2012; Forcales et al. 2012; Gallagher et al. 2012). Such recruitment is thought to be a prerequisite to enable transcription or to allow access of additional trans-acting factors (Sudarsanam and Winston 2000). The loss of sem-4 and ham-2 expression in ham-3 mutants could be explained by ham-3 cooperating with the egl-5 homeodomain transcription factor, a known upstream regulator of sem-4 and ham-2 (Baum et al. 1999). Since the spectrum of ham-3 phenotypes is more restricted than the spectrum of egl-5 mutants (e.g., egl-5 affects hood formation, but ham-3 does not; Table 1), ham-3 may cooperate with egl-5 to regulate only a subset of the egl-5 targets, such as sem-4 and ham-2, but not targets involved in, for example, hood formation (Figure 4D). We can also exclude the possibility that ham-3 operates upstream of egl-5 through our observation that egl-5 expression is unaffected in ham-3 mutants (data not shown).

Conclusions

BAF complexes are known to play important roles in various cellular differentiation processes and their involvement in several different cancers defines them as important tumor suppressor genes (de la Serna et al. 2006; Yoo and Crabtree 2009; Hargreaves and Crabtree 2011; Wilson and Roberts 2011). One process that these complexes have not been described as being involved in yet is the terminal differentiation of specific neuronal subtypes. Our work implicates several BAF subunits in the differentiation of a specific subtype of serotonergic neurons in C. elegans. A number of sequence-specific transcription factors have been identified in several distinct organisms that control serotonergic neuron fate (Flames and Hobert 2011; Deneris and Wyler 2012), but to our knowledge, no chromatin remodeling factor has yet been implicated in serotonergic neuron development. The role of ham-3 in HSN development is broad but not ubiquitous. Neurotransmitter phenotype, cell migration, and axon pathfinding are affected, but not some other signs of morphological differentiation. Moreover, ham-3 does not affect the serotonergic neurotransmitter phenotype of any other serotonergic neuron class aside from HSN.

Our findings underscore the cell-type specificity of the function of the BAF nucleosome remodeling complex. The yeast version of the BAF complex (called SWI/SNF) is involved in the regulation of a relatively small number of genes (Sudarsanam and Winston 2000). In metazoans, the specificity of BAF complex function has further increased through the dynamic use of alternative BAF subunits (Yoo and Crabtree 2009; Hargreaves and Crabtree 2011). For example, in vertebrates, the BAF53 subunit is encoded by two distinct genes, BAF53a and BAF53b. During neuronal development, the BAF53a subunit is switched for the BAF53b subunit (Lessard et al. 2007). Knocking out BAF53b does not result in the lethality observed upon knocking out general subunits, but results in specific dendritic patterning defects (Wu et al. 2007). The BAF60 subunit paralogs BAF60a, BAF60b, and BAF60c also likely have cell-type-specific functions based on their distinctive expression patterns (Wang et al. 1996) and based on the cell-type-specific assembly of BAF complexes with different BAF60 subunits (Lickert et al. 2004; Ho et al. 2009). However, ultimate proof for cell-type-specific functions of specific BAF60 paralogs in the form of germline knockout that results in cell-type-specific phenotypes has been lacking. RNAi-mediated knockdown of BAF60c results in muscle defects, but RNAi results only in an incomplete elimination of gene activity (Lickert et al. 2004). The fly BAF60 homolog (Bap60) has been knocked out (resulting in lethality) (Moller et al. 2005), but this case is not informative due to the fact that unlike vertebrates and worms, flies only contain a single BAF60 ortholog.

Like vertebrates, C. elegans contains multiple BAF60-type subunits that display broad, but nevertheless distinct expression patterns, pointing to tissue/time-specific function. Moreover, the genetic analysis of null mutations in one of the homologs, ham-3, indeed demonstrates cell-type-specific functions of a BAF60 subunit. First, unlike loss of core BAF complex components (i.e., psa-4 or psa-1, the Brg1/Brm and BAF155/BAF170 orthologs, respectively), complete loss of ham-3 does not affect viability under standard conditions (i.e., 15° or 20°) and ham-3 null mutant animals look morphologically grossly normal. On a cellular level, ham-3 null mutants show defects in the differentiation of a specific subset of serotonergic neurons (HSNs), but not the differentiation of other serotonergic neurons. On a molecular level, ham-3 null mutants show selective effects on the expression of terminal differentiation markers of HSNs. While genes involved in serotonergic neurotransmission are affected, a gene involved in neuropeptidergic signaling is not. The selective phenotype of ham-3 could be explained by ham-3 and its paralog swsn-2.2 having distinct functions (e.g., they could recruit the BAF complex to distinct transcription factors). Alternatively, they may act in a partially redundant manner. Since the expression of ham-3 and swsn-2.2 do not overlap in all cells at all stages (e.g., swsn-2.2 fades in adults while ham-3 does not), any redundancies in gene function may be at most partial.

The overall importance of the BAF complex in humans is not only evidenced by mutations in the Snf5 subunit that lead to childhood tumors (Wilson and Roberts 2011), but also by the recent finding that haploinsufficiency of other BAF subunits result in various neurological conditions, including nonsyndromic intellectual disability, Coffin-Siris syndrome, and Nicolaides-Baraitser syndrome (Santen et al. 2012). Understanding basic features of the function of this complex, including its tissue-specific mode of action, is therefore an important future goal.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Qi Chen for expert assistance in generating transgenic strains; Alexander Boyanov for whole genome sequencing; Erin Conlon for help with building strains; Pat Gordon, Min Han, and the Caenorhabditis elegans Genetics Center (CGC) for kindly providing strains; the Caenorhabditis elegans Reverse Genetics Core Facility at the University of British Columbia for the ok3161, gk1041, and gk816 alleles; and Shohei Mitani at Tokyo Women’s Medical University School of Medicine for the tm3309 allele. This work was funded by the National Institutes of Health (R01NS039996-05; R01NS050266-03). O.H. is an investigator of the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Footnotes

Communicating editor: P. Sengupta

Literature Cited

- Basson M., Horvitz H. R., 1996. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene sem-4 controls neuronal and mesodermal cell development and encodes a zinc finger protein. Genes Dev. 10: 1953–1965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum P. D., Guenther C., Frank C. A., Pham B. V., Garriga G., 1999. The Caenorhabditis elegans gene ham-2 links Hox patterning to migration of the HSN motor neuron. Genes Dev. 13: 472–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow H., Doitsidou M., Sarin S., Hobert O., 2009. MAQGene: software to facilitate C. elegans mutant genome sequence analysis. Nat. Methods 6: 549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chase D. L., Koelle M. R., 2007. Biogenic amine neurotransmitters in C. elegans. Neuropeptides (February 20, 2007), WormBook, ed. The C. elegans Research Community WormBook, /10.1895/wormbook.1.132.1. http://www.wormbook.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L., Fulcoli F. G., Ferrentino R., Martucciello S., Illingworth E. A., et al. , 2012. Transcriptional control in cardiac progenitors: Tbx1 interacts with the BAF chromatin remodeling complex and regulates Wnt5a. PLoS Genet. 8: e1002571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark S. G., Chiu C., 2003. C. elegans ZAG-1, a Zn-finger-homeodomain protein, regulates axonal development and neuronal differentiation. Development 130: 3781–3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui M., Fay D. S., Han M., 2004. lin-35/Rb cooperates with the SWI/SNF complex to control Caenorhabditis elegans larval development. Genetics 167: 1177–1185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Serna I. L., Ohkawa Y., Imbalzano A. N., 2006. Chromatin remodelling in mammalian differentiation: lessons from ATP-dependent remodellers. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7: 461–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debril M. B., Gelman L., Fayard E., Annicotte J. S., Rocchi S., et al. , 2004. Transcription factors and nuclear receptors interact with the SWI/SNF complex through the BAF60c subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 279: 16677–16686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deneris E. S., Wyler S. C., 2012. Serotonergic transcriptional networks and potential importance to mental health. Nat. Neurosci. 15: 519–527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai C., Garriga G., McIntire S. L., Horvitz H. R., 1988. A genetic pathway for the development of the Caenorhabditis elegans HSN motor neurons. Nature 336: 638–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai C., Horvitz H. R., 1989. Caenorhabditis elegans mutants defective in the functioning of the motor neurons responsible for egg laying. Genetics 121: 703–721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duerr J. S., Frisby D. L., Gaskin J., Duke A., Asermely K., et al. , 1999. The cat-1 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans encodes a vesicular monoamine transporter required for specific monoamine-dependent behaviors. J. Neurosci. 19: 72–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finney M., Ruvkun G., Horvitz H. R., 1988. The C. elegans cell lineage and differentiation gene unc-86 encodes a protein with a homeodomain and extended similarity to transcription factors. Cell 55: 757–769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flames N., Hobert O., 2011. Transcriptional control of the terminal fate of monoaminergic neurons. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 34: 153–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forcales S. V., Albini S., Giordani L., Malecova B., Cignolo L., et al. , 2012. Signal-dependent incorporation of MyoD-BAF60c into Brg1-based SWI/SNF chromatin-remodelling complex. EMBO J. 31: 301–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher J. M., Komati H., Roy E., Nemer M., Latinkic B. V., 2012. Dissociation of cardiogenic and postnatal myocardial activities of GATA4. Mol. Cell. Biol. 32: 2214–2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garriga G., Guenther C., Horvitz H. R., 1993. Migrations of the Caenorhabditis elegans HSNs are regulated by egl-43, a gene encoding two zinc finger proteins. Genes Dev. 7: 2097–2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenther C., Garriga G., 1996. Asymmetric distribution of the C. elegans HAM-1 protein in neuroblasts enables daughter cells to adopt distinct fates. Development 122: 3509–3518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare E. E., Loer C. M., 2004. Function and evolution of the serotonin-synthetic bas-1 gene and other aromatic amino acid decarboxylase genes in Caenorhabditis. BMC Evol. Biol. 4: 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hargreaves D. C., Crabtree G. R., 2011. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling: genetics, genomics and mechanisms. Cell Res. 21: 396–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho L., Jothi R., Ronan J. L., Cui K., Zhao K., et al. , 2009. An embryonic stem cell chromatin remodeling complex, esBAF, is an essential component of the core pluripotency transcriptional network. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106: 5187–5191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobert O., 2002. PCR fusion-based approach to create reporter gene constructs for expression analysis in transgenic C. elegans. Biotechniques 32: 728–730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsiao P. W., Fryer C. J., Trotter K. W., Wang W., Archer T. K., 2003. BAF60a mediates critical interactions between nuclear receptors and the BRG1 chromatin-remodeling complex for transactivation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23: 6210–6220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito T., Yamauchi M., Nishina M., Yamamichi N., Mizutani T., et al. , 2001. Identification of SWI.SNF complex subunit BAF60a as a determinant of the transactivation potential of Fos/Jun dimers. J. Biol. Chem. 276: 2852–2857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jafari G., Xie Y., Kullyev A., Liang B., Sze J. Y., 2011. Regulation of extrasynaptic 5-HT by serotonin reuptake transporter function in 5-HT-absorbing neurons underscores adaptation behavior in Caenorhabditis elegans. J. Neurosci. 31: 8948–8957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lessard J., Wu J. I., Ranish J. A., Wan M., Winslow M. M., et al. , 2007. An essential switch in subunit composition of a chromatin remodeling complex during neural development. Neuron 55: 201–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, C., and K. Kim, 2008 Neuropeptides (September 25, 2008), WormBook, ed. The C. elegans Research Community WormBook, /10.1895/wormbook.1.142.1. http://www.wormbook.org.

- Li S., Liu C., Li N., Hao T., Han T., et al. , 2008. Genome-wide coactivation analysis of PGC-1alpha identifies BAF60a as a regulator of hepatic lipid metabolism. Cell Metab. 8: 105–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lickert H., Takeuchi J. K., Von Both I., Walls J. R., McAuliffe F., et al. , 2004. Baf60c is essential for function of BAF chromatin remodelling complexes in heart development. Nature 432: 107–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller A., Avila F. W., Erickson J. W., Jackle H., 2005. Drosophila BAP60 is an essential component of the Brahma complex, required for gene activation and repression. J. Mol. Biol. 352: 329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller C. P., Jacobs B. L., 2010. Handbook of the Behavioral Neurobiology of Serotonin, Academic Press, San Diego. [Google Scholar]

- Oh J., Sohn D. H., Ko M., Chung H., Jeon S. H., et al. , 2008. BAF60a interacts with p53 to recruit the SWI/SNF complex. J. Biol. Chem. 283: 11924–11934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan M. L., Sif S., Narlikar G. J., Kingston R. E., 1999. Reconstitution of a core chromatin remodeling complex from SWI/SNF subunits. Mol. Cell 3: 247–253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pocock R., Hobert O., 2010. Hypoxia activates a latent circuit for processing gustatory information in C. elegans. Nat. Neurosci. 13: 610–614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santen G. W., Kriek M., van Attikum H., 2012. SWI/SNF complex in disorder: SWItching from malignancies to intellectual disability. Epigenetics 7.: 1219–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarin S., Bertrand V., Bigelow H., Boyanov A., Doitsidou M., et al. , 2010. Analysis of multiple ethyl methanesulfonate-mutagenized caenorhabditis elegans strains by whole-genome sequencing. Genetics 185: 417–430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawa H., Kouike H., Okano H., 2000. Components of the SWI/SNF complex are required for asymmetric cell division in C. elegans. Mol. Cell 6: 617–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer, W. R., 2005 Egg-laying. (December 14, 2005), WormBook, ed. The C. elegans Research Community WormBook, /10.1895/wormbook.1.38.1. http://www.wormbook.org.

- Schmitz C., Kinge P., Hutter H., 2007. Axon guidance genes identified in a large-scale RNAi screen using the RNAi-hypersensitive Caenorhabditis elegans strain nre-1(hd20) lin-15b(hd126). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 834–839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata Y., Uchida M., Takeshita H., Nishiwaki K., Sawa H., 2012. Multiple functions of PBRM-1/Polybromo- and LET-526/Osa-containing chromatin remodeling complexes in C. elegans development. Dev. Biol. 361: 349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sudarsanam P., Winston F., 2000. The Swi/Snf family nucleosome-remodeling complexes and transcriptional control. Trends Genet. 16: 345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze J. Y., Victor M., Loer C., Shi Y., Ruvkun G., 2000. Food and metabolic signalling defects in a Caenorhabditis elegans serotonin-synthesis mutant. Nature 403: 560–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sze J. Y., Zhang S., Li J., Ruvkun G., 2002. The C. elegans POU-domain transcription factor UNC-86 regulates the tph-1 tryptophan hydroxylase gene and neurite outgrowth in specific serotonergic neurons. Development 129: 3901–3911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi J. K., Lickert H., Bisgrove B. W., Sun X., Yamamoto M., et al. , 2007. Baf60c is a nuclear Notch signaling component required for the establishment of left-right asymmetry. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 846–851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trent C., Tsuing N., Horvitz H. R., 1983. Egg-laying defective mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 104: 619–647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W., Xue Y., Zhou S., Kuo A., Cairns B. R., et al. , 1996. Diversity and specialization of mammalian SWI/SNF complexes. Genes Dev. 10: 2117–2130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J. G., Southgate E., Thomson J. N., Brenner S., 1986. The structure of the nervous system of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 314: 1–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson B. G., Roberts C. W., 2011. SWI/SNF nucleosome remodellers and cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 11: 481–492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J., Duggan A., Chalfie M., 2001. Inhibition of touch cell fate by egl-44 and egl-46 in C. elegans. Genes Dev. 15: 789–802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J. I., Lessard J., Olave I. A., Qiu Z., Ghosh A., et al. , 2007. Regulation of dendritic development by neuron-specific chromatin remodeling complexes. Neuron 56: 94–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo A. S., Crabtree G. R., 2009. ATP-dependent chromatin remodeling in neural development. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 19: 120–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahn T. R., Macmorris M. A., Dong W., Day R., Hutton J. C., 2001. IDA-1, a caenorhabditis elegans homolog of the diabetic autoantigens IA- 2 and phogrin, is expressed in peptidergic neurons in the worm. J. Comp. Neurol. 429: 127–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang F., O'Meara M. M., Hobert O., 2001. A left/right asymmetric neuronal differentiation program is controlled by the C. elegans LSY-27 Zn finger transcription factor. Genetics 188: 753–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.