Abstract

Transfer RNAs (tRNAs) are essential for protein synthesis. In eukaryotes, tRNA biosynthesis employs a specialized RNA polymerase that generates initial transcripts that must be subsequently altered via a multitude of post-transcriptional steps before the tRNAs beome mature molecules that function in protein synthesis. Genetic, genomic, biochemical, and cell biological approaches possible in the powerful Saccharomyces cerevisiae system have led to exciting advances in our understandings of tRNA post-transcriptional processing as well as to novel insights into tRNA turnover and tRNA subcellular dynamics. tRNA processing steps include removal of transcribed leader and trailer sequences, addition of CCA to the 3′ mature sequence and, for tRNAHis, addition of a 5′ G. About 20% of yeast tRNAs are encoded by intron-containing genes. The three-step splicing process to remove the introns surprisingly occurs in the cytoplasm in yeast and each of the splicing enzymes appears to moonlight in functions in addition to tRNA splicing. There are 25 different nucleoside modifications that are added post-transcriptionally, creating tRNAs in which ∼15% of the residues are nucleosides other than A, G, U, or C. These modified nucleosides serve numerous important functions including tRNA discrimination, translation fidelity, and tRNA quality control. Mature tRNAs are very stable, but nevertheless yeast cells possess multiple pathways to degrade inappropriately processed or folded tRNAs. Mature tRNAs are also dynamic in cells, moving from the cytoplasm to the nucleus and back again to the cytoplasm; the mechanism and function of this retrograde process is poorly understood. Here, the state of knowledge for tRNA post-transcriptional processing, turnover, and subcellular dynamics is addressed, highlighting the questions that remain.

THE primary function of eukaryotic transfer RNAs (tRNAs) is the essential role of delivering amino acids, as specified by messenger RNA (mRNA) codons, to the cytoplasmic and organellar protein synthesis machineries. However, it is now appreciated that eukaryotic tRNAs serve additional functions in processes such as targeting proteins for degradation via the N-end rule pathway, signaling in the general amino acid control pathway, and regulation of apoptosis by binding cytochrome C (Varshavsky 1997; Dever and Hinnebusch 2005; Mei et al. 2010). tRNAs are also employed as reverse transcription primers and for strand transfer during retroviral replication (Marquet et al. 1995; Piekna-Przybylska et al. 2010). Newly discovered pathways that generate tRNA fragments document roles of the fragments in translation regulation and cellular responses to stress (Yamasaki et al. 2009; reviewed in Parker 2012). Due to all these functions, alterations in the rate of tRNA transcription or defects in various of the post-transcriptional processing steps results in numerous human diseases including neuronal disorders (reviewed in Lemmens et al. 2010) and pontocerebellar hypoplasia (Budde et al. 2008). Despite the importance and medical implications, much remains to be learned about tRNA biosynthesis, turnover, and subcellular dynamics.

Cytoplasmic tRNAs are transcribed in the nucleus by a DNA-dependent RNA polymerase, Pol III, that is dedicated to transcription of small RNAs. After transcription, tRNAs undergo a bewildering number of post-transcriptional alterations. Recent discoveries have uncovered many roles for tRNA modifications. Since nuclear-encoded tRNAs function in the cytoplasm or in organelles, additional steps are required to deliver the processed or partially processed tRNAs to the correct subcellular location. Subcellular tRNA trafficking is surprisingly complex because it is now known not to be solely unidirectional from the nucleus to the cytoplasm. Finally, although it has been the conventional wisdom that tRNAs are highly stable molecules, recent studies have discovered multiple pathways that degrade partially processed or misfolded tRNAs and therefore serve in tRNA quality control.

This review focuses on post-transcription events that are required for the biogenesis, turnover, and intracellular dynamics of tRNAs. A majority of the recent discoveries have been made through genetic, genomic, biochemical, and cell biological studies employing the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Although this review focuses on the studies from yeast, for perspective and where information is available, similarities and differences of the processes in budding yeast to those in other organisms are described. Many of the subjects considered here have been the subjects of other recent reviews (Hopper and Shaheen 2008; Hopper et al. 2010; Phizicky and Alfonzo 2010; Phizicky and Hopper 2010; Rubio and Hopper 2011; Maraia and Lamichhane 2011; Parker 2012). Therefore, this article emphasizes the use of genetic and genomic analyses in yeast that led to the discoveries and provides information on new discoveries not previously reviewed. Finally, most of the topics discussed concern tRNAs encoded by the nuclear genome, rather than the mitochondrial genome.

tRNA Post-Transcriptional Processing

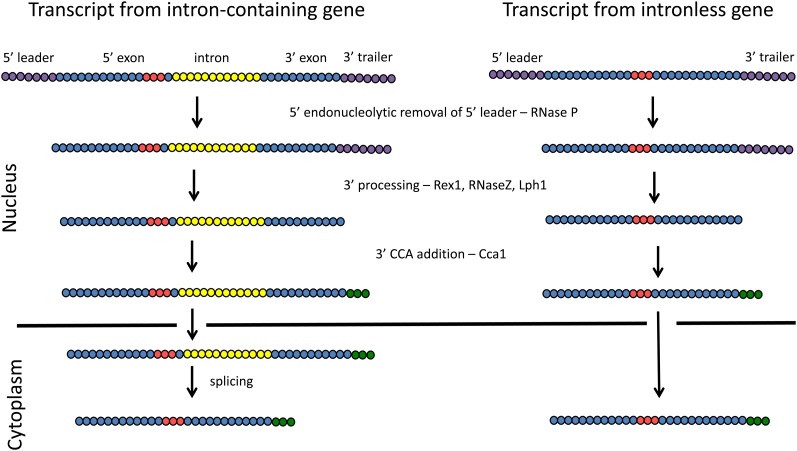

tRNAs are transcribed as precursor molecules (pre-tRNA) that undergo an elaborate set of post-transcriptional alterations to generate mature RNAs. These post-transcriptional steps include: nucleotide removal at both the 5′ and 3′ ends, nucleotide addition to all 3′ ends and to a particular 5′ end, removal of introns from the subset of transcripts transcribed from intron-containing genes, and nucleoside modifications that include 25 different base or sugar methylations, base deaminations, base isomerizations, and exotic moiety additions to bases (Figure 1 to Figure 4). Nearly all the yeast genes involved in these complicated post-transcriptional processes have now been identified and their functions are being clarified (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Steps in tRNA processing involving nucleotide deletion or addition for tRNAs encoded by intron-containing and intron-lacking genes. tRNAs are depicted as linear series of circles that are color coded. Purple circles depict transcribed leader and trailer sequences at the 5′ and 3′ ends, respectively; generally, pre-tRNA leader and trailers contain ∼12 nucleotides. Yellow circles depict intron sequences that vary, depending upon the tRNA species, from 14 to 60 nucleotides. Blue and red-colored nucleosides depict the mature exons, where red indicates the anticodon located at nucleotides 34–36. Green circles depict the post-transcriptionally added CCA nucleotides that are required for aminoacylation. G−1 added to the 5′ end of tRNAHis is not shown.

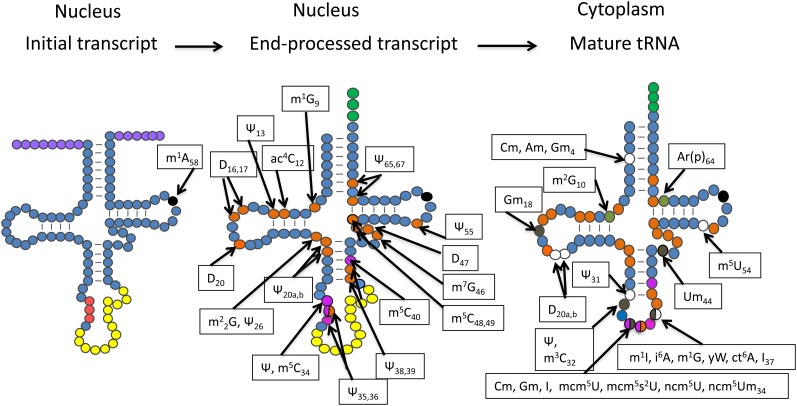

Figure 4.

Cell biology of tRNA modifications. Solid black circle indicates a modification known to occur on initial pre-tRNAs. Several modifications occur in the nucleus; magenta circles indicate those modifications that require the substrate to contain an intron, whereas orange circles indicate modifications that do not appear to require intron-containing tRNAs as substrate. Numerous other modifications occur in the cytoplasm; those that require that the intron first be spliced are brown, whereas those with no known substrate specificity or are restricted to tRNAs encoded by intronless genes are colored khaki. Open circles are catalyzed by enzymes whose subcellular locations are unknown. Different tRNA species possess different subsets of modifications; particular nucleosides that can possess numerous different modifications are indicated; half-colored circles indicate that the modifying enzymes have varying substrate specificity and/or subcellular location. Note that modification of G37 by Trm5 that requires tRNAs to be spliced occurs in the nucleoplasm after retrograde nuclear import.

Table 1. Saccharomyces cerevisiae genes implicated in cytoplasmic tRNA processing, turnover, and subcellular trafficking.

| Yeast gene | Function | Null mutant phenotype | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-tRNA end processing | |||

| POP1, POP3, POP4, POP5, POP6, POP7, POP8, RPP1, RPR2, RPR1 | RNase P – 5′ leader endonuclease | Essential | (Chamberlain et al. 1998) |

| LHP1 | tRNA 3′ trailer processing | Not essential | (Yoo and Wolin 1997) |

| REX1 | 3′ trailer exonuclease | Not essential | (Copela et al. 2008; Ozanick et al. 2009) |

| TRZ1 | RNase Z – 3′ trailer endonuclease | Essential | (Takaku et al. 2003) |

| CCA1 | CCA | Essential | (Aebi et al. 1990) |

| THG1 | G-1 addition to tRNAHis | Essential | (Gu et al. 2003) |

| Pre-tRNA splicing | |||

| SEN2, SEN15, SEN34, SEN54 | Splicing endonuclease | Essential | (Ho et al. 1990; Trotta et al. 1997) |

| TPT1 | 2′-phosphotransferase | Essential | (Culver et al. 1997) |

| TRL1 | tRNA ligase | Essential | (Phizicky et al. 1986) |

| tRNA Modification | |||

| DUS1 | D16, D17 | Not essential | (Bishop et al. 2002; Xing et al. 2002) |

| DUS2 | D20 | Not essential | (Xing et al. 2004) |

| DUS3 | D47 | Not essential | (Xing et al. 2004) |

| DUS4 | D20a, D20b | Not essential | (Xing et al l. 2004) |

| ELP1, ELP2, ELP3, ELP4, ELP5, ELP6, KTI11, KTI12, KTI13, KTI14, SIT4, SAP185, SAP190 | mcm5U34, mcm5s2U34, ncm5U34, ncm5Um34 | Many phenotypes | (Huang et al. 2005; Huang et al. 2008; Jablonowski et al. 2004) |

| NFS1, ISU1, ISU2, CFD1, NBP35, CIA1, URM1, UBA4, NCS2, NCS6, TUM1 | mcm5s2U34 | Not essential | (Bjork et al. 2007; Huang et al. 2008; Nakai et al. 2007; Nakai et al. 2004) |

| MOD5 | i6A37 | Loss of suppression | (Dihanich et al. 1987) |

| PUS1 | Ψ26, Ψ27,Ψ28 Ψ34, Ψ(35), Ψ36, Ψ65, Ψ67 | Not essential | (Motorin et al.. 1998; Simos et al. 1996) |

| PUS3 | Ψ38, Ψ39 | Slow growth | (Lecointe et al.1998) |

| PUS4 | Ψ55 | Not essential | (Becker et al. 1997) |

| PUS6 | Ψ31 | Not essential | (Ansmant et al. 2001) |

| PUS7 | Ψ13, Ψ35 | Not essential | (Behm-Ansmant et al. 2003) |

| PUS8 | Ψ32 | Not essential | (Behm-Ansmant et al. 2004) |

| RIT1 | Ar(p)64 | Not essential | (Astrom and Bystrom 1994) |

| SUA5, KEOPS, TCD1, TCD2 | ct6A37 | Very sick | (El Yacoubi et al. 2009; Miyauchi et al. 2013) |

| TAD1 | I37 | Not essential | (Gerber et al. 1998) |

| TAD2, TAD3 | I34 | Essential | (Gerber and Keller 1999) |

| TAN1 | ac4C12 | Temperature sensitive | (Johansson and Bystrom 2004) |

| TRM1 | m2,2G26 | Not essential | (Ellis et al. 1986) |

| TRM2 | m5U54 | Not essential | (Hopper et al. 1982; Nordlund et al. 2000) |

| TRM3 | Gm18 | Not essential | (Cavaille et al. 1999) |

| TRM4 | m5C34, m5C40, m5C48, m5C49 | Not essential | (Motorin and Grosjean 1999) |

| TRM5 | m1G37, m1I37, yW37 | Very sick | (Bjork et al. 2001) |

| TRM6, TRM61 | m1A58 | Essential | (Anderson et al. 1998) |

| TRM7, TRM732 | Cm32 | Synthetic slow growth with trm734Δ; paromomycin sensitive | (Guy et al. 2012; Pintard et al. 2002) |

| TRM7, TRM734 | Cm34, Gm34, ncm5Um34 | Synthetic slow growth with trm732Δ; paromomycin sensitive | (Guy et al. 2012; Pintard et al. 2002) |

| TRM8, TRM82 | m7G46 | Not essential | (Alexandrov et al. 2002) |

| TRM9, TRM112 | mcm5U34 and mcm5s2U34 | Not essential; paromomycin sensitive | (Kalhor and Clarke 2003; Studte et al. 2008) |

| TRM10 | m1G9 | Not essential | (Jackman et al. 2003) |

| TRM11, TRM112 | m2G10 | Not essential | (Purushothaman et al. 2005) |

| TRM13 | Am4, Gm4, Cm4 | Not essential | (Wilkinson et al. 2007) |

| TRM44 | Um44 | Not essential | (Kotelawala et al. 2008) |

| TRM140 | m3C32 | Not essential | (D’Silva et al. 2011; Noma et al. 2011) |

| TYW1, TYW2, TYW3, TYW4, TRM5 | yW37 | Not essential; reading frame maintenance | (Kalhor et al. 2005; Noma et al. 2006) |

| tRNA turnover/cleavage | |||

| TRF4 | 3′ poly(A) polymerase; TRAMP component | Not essential | (Kadaba et al. 2004, 2006) |

| RRP44 | 3′ to 5′ exonuclease; exosome component | Essential | (Kadaba et al. 2004, 2006) |

| MET22 | Methionine biosynthesis | pAp accumulation; Rat1 and Xrn1 inhibition | (Dichtl et al. 1997; Chernyakov et al. 2008) |

| RAT1 | 5′ to 3′ exonuclease – RTD component | Essential | (Chernyakov et al. 2008) |

| XRN1 | 5′ to 3′ exonuclease – RTD component | Not essential | (Chernyakov et al. 2008) |

| RNY1 | endonuclease generating tRNA ∼halves | Not Essential | (Thompson and Parker 2009b) |

| tRNA subcellular trafficking | |||

| LOS1 | Export, reexport | Not essential | (Hopper et al. 1980; Murthi et al. 2010) |

| MSN5 | Reexport | Not essential | (Murthi et al. 2010) |

| MTR10 | Retrograde import | Sick | (Shaheen and Hopper 2005) |

For complex modifications, underlined portion indicates the part of the modification due to the corresponding gene(s).

Removal of 5′ leader and 3′ trailer sequences from pre-tRNAs

The vast majority of yeast nucleus-encoded tRNAs are transcribed as single pre-tRNAs with ∼12 extra leader nucleotides on the 5′ end and ∼12 extra 3′ trailer nucleotides (O’Connor and Peebles 1991; reviewed in Hopper and Phizicky 2003). However, the yeast genome contains two, and possibly four, copies of DNA sequences that encode tRNAArgUCU and tRNAAsp that are transcribed as dimers, and therefore their transcripts possess extra 3′ and 5′ intergenic sequences (Schmidt et al. 1980) (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/GtRNAdb/). Removal of 5′ leaders from initial tRNA transcripts usually precedes removal of the 3′ end extensions; however, in the case of pre-tRNATrp, 3′ processing precedes 5′ processing (O’Connor and Peebles 1991; Kufel et al. 2003).

Removal of the 5′ extension is catalyzed by the endonuclease RNase P (Figure 1; Table 1). There are three interesting features about RNase P. First, the yeast mitochondrial and nucleolar forms of the enzyme are encoded by separate genes that have different structures and composition, although both enzymes are composed of RNA and protein. Nucleolar RNase P consists of nine proteins (Pop1, Pop3–Pop8, Rpp1, and Rpr2) and a single essential RNA (RPR1) encoded in the nucleus (reviewed in Xiao et al. 2002). In contrast, the mitochondrial enzyme contains only a single nuclear encoded protein, Rpm2, and a single RNA (RPM1) encoded by the mitochondrial genome (Dang and Martin 1993; Martin and Lang 1997). Moreover, RPR1 and RPM1 differ extensively in length and sequence. Second, there are extensive phylogenic differences in RNase P structure. Unlike the bacterial, archaeal, and eukaryotic forms of RNase P, which are ribozymes with varying numbers of protein subunits (reviewed in Jarrous and Gopalan 2010), higher plant mitochondrial and nuclear versions are now known to be protein enzymes (Thomas et al. 2000; Gutmann et al. 2012). Third, most of the protein subunits of the yeast and human RNase P enzymes are shared with RNase MRP, involved in pre-rRNA processing (Xiao et al. 2002; Jarrous and Gopalan 2010).

In both bacteria and yeast, removal of 3′ extensions from pre-tRNA is complicated, involving both exo- and endonucleases (Li and Deutscher 1996; Phizicky and Hopper 2010) (Figure 1; Table 1). Yeast Rex1 is a 3′ to 5′ exonuclease that participates in the processing of pre-tRNA trailers as well as in the processing of other RNAs such as 5S rRNA, 5.8S rRNA, and snRNAs (van Hoof et al. 2000; Copela et al. 2008; Ozanick et al. 2009). RNase Z, Trz1, is the endonuclease that participates in 3′ end processing for both mitochondrial and nuclear encoded tRNAs (Chen et al. 2005; Daoud et al. 2011; Maraia and Lamichhane 2011). The exo- and endonucleases have been proposed to have differential access to particular pre-tRNAs dependent upon tRNA binding by the La protein (Lhp1), such that La binding to tRNA 3′ ends inhibits access to Rex1 and 3′ maturation occurs via Trz1-mediated endonucleolytic cleavage (Yoo and Wolin 1997). Since Lhp1 is unessential and in its absence tRNA 3′ ends are processed (Yoo and Wolin 1994, 1997; Kufel et al. 2003), there is competition between the endonucleolytic and exonucleolytic modes of tRNA 3′ end maturation.

Additions to pre-tRNA 3′ and 5′ termini

All tRNAs contain a 3′ terminal CCA sequence that is required for tRNA aminoacylation. Escherichia coli tRNAs are encoded with a CCA sequence, but nevertheless possess the gene for the CCA adding enzyme, tRNA nucleotidyl transferase, which functions in tRNA 3′ end repair (Zhu and Deutscher 1987 and references therein; Reuven and Deutscher 1993). In contrast, the 3′ CCA sequences of yeast and vertebrates tRNAs are formed strictly post-transcriptionally by nucleotidyl transferase catalysis (Figure 1; Table 1). Yeast tRNA nucleotidyl transferase is encoded by CCA1 (Aebi et al. 1990). CCA1 encodes multiple isoforms. Cca1-I, Cca1-II, and Cca1-III are generated by alternative transcriptional and translational start sites. These isoforms are differently distributed among mitochondria, the cytoplasm, and the nucleoplasm (reviewed in Martin and Hopper 1994). The nuclear pool functions in tRNA 3′ end biogenesis, whereas the cytoplasmic pool functions in tRNA 3′ repair. Yeast cells lacking cytoplasmic Cca1 grow poorly and accumulate 3′ end-shortened tRNAs (Wolfe et al. 1996). The mitochondrial form functions presumably in both biogenesis and 3′ end repair.

For most tRNAs, RNase P generates the mature 5′ end. However, generation of the tRNAHis 5′ end requires an additional step—addition of a 5′ G (“G−1”), catalyzed by Thg1 (Gu et al. 2003). G−1 addition to tRNAHis is essential for its aminoacylation (Gu et al. 2005; Preston and Phizicky 2010). Thg1 is a remarkable enzyme because it catalyzes nucleotide addition in the 3′ to 5′ direction, opposite of the direction for other nucleotide additions to DNA or RNA polymers. In fact, under particular in vitro conditions, Thg1 catalyzes the addition of multiple nucleotides in the 3′ to 5′ direction in a template-dependent fashion (Jackman and Phizicky 2006). Perhaps Thg1 templated 3′ to 5′ polymerization is a remnant of its origins as a RNA repair and editing activity (reviewed in Jackman et al. 2012) or perhaps it has maintained this activity to serve a role in a yet to be discovered process unrelated to tRNA biogenesis. Nevertheless, Thg1’s essential role involves tRNAHis biogenesis as the lethality of thg1Δ strains is suppressed by overexpression of tRNAHis and its synthetase (Preston and Phizicky 2010).

tRNA splicing

Location and distribution of introns in tRNA genes:

tRNA genes often contain introns that must be spliced before tRNAs can function in protein synthesis. Yeast and vertebrate tRNA introns are always located one base 3′ to the anticodon, but introns appear in other locations in tRNA genes in Archaea (Phizicky and Hopper 2010) (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/GtRNAdb/). There is significant phylogenic divergence regarding the percentage of tRNA genes that contain introns, ranging from 0% in bacteria like E. coli, to ∼5% in Drosophila, Caenorhabditis elegans, mouse, and human genomes, to >50% in some archaeal genomes (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/GtRNAdb/). Of the 274 yeast nuclear tRNA genes, 59 (>20%) contain an intron. The phylogenic distribution of introns within particular tRNA genes is not conserved with the exception of tRNATyr that generally possess introns (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/GtRNAdb/). In humans usually only a subset of genes encoding a given isoacceptor contain an intron (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/GtRNAdb/). In contrast, for S. cerevisiae and other fungi, generally all or the majority of duplicated copies of genes encoding a given tRNA isoacceptor will or will not contain an intron. In S. cerevisiae, a total 10 tRNA families contain an intron. They vary from 14 to 60 nucleotides, but for a given family they are nearly identical in length and sequence (http://lowelab.ucsc.edu/GtRNAdb/). Thus, removal of introns by tRNA splicing is an essential process in yeast and other fungi as it is impossible to generate a complete set of tRNAs for decoding without splicing.

Function of tRNA introns:

Studies in which the intron from one (SUP6) of the eight copies of genes encoding tRNATyr was removed showed that the intron was required for a particular nucleoside modification as the mutant SUP6 generated a tRNA missing a pseudouridine modification in the anticodon loop. tRNATyr lacking this modification is defective in tRNA-mediated nonsense suppression (Johnson and Abelson 1983). As detailed below, there are additional examples of modifications occurring only on intron-containing pre-tRNAs.

To determine whether tRNA introns function other than to generate substrates for particular modification enzymes, the Yoshihisa group (Mori et al. 2011) created a yeast strain in which the introns were removed from all six copies of the genes encoding tRNATrp. tRNATrp does not contain modifications that depend on the presence of an intron. Surprisingly, there was very little negative consequence of deleting the introns from all tRNATrp-encoding genes as the strain with only intronless tRNATrp genes grew indistinguishably from wild-type yeast even under coculture competition conditions. Only a few changes in protein composition, as determined by 2-day gel electrophoresis, could be detected (Mori et al. 2011). Thus, the selection for introns in tRNA genes remains unknown.

Pre-tRNA splicing steps:

Initial studies of the pre-tRNA splicing process were aided by use of a yeast strain that possesses a conditional mutation of the Ran GTPase activating protein (RanGAP), rna1-1, which accumulates intron-containing pre-tRNAs that served as splicing substrates (Hopper et al. 1978; Knapp et al. 1978; Corbett et al. 1995). Subsequent studies, described below, showed that accumulation of intron-containing pre-tRNAs occurs because tRNAs are spliced in the cytoplasm and the rna1-1 mutation blocks tRNA export to the cytoplasm (Sarkar and Hopper 1998).

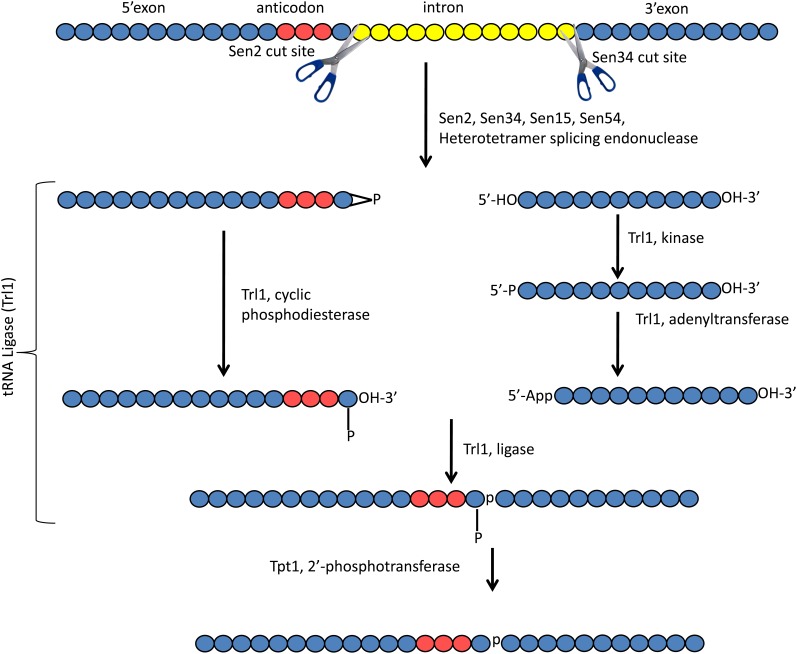

The pre-tRNA splicing reaction occurs in three steps involving three essential protein enzymes (Phizicky et al. 1992; Culver et al. 1997; Trotta et al. 1997) (Figure 2; Table 1). Step one of the splicing reaction is the removal of introns from pre-tRNAs. This step is catalyzed by tRNA splicing endonuclease (Knapp et al. 1978). In yeast and vertebrates, the tRNA splicing endonuclease is a heterotetramer (Trotta et al. 1997; Paushkin et al. 2004). The yeast proteins of the heterotetramer are: Sen2, Sen34, Sen15, and Sen54 (Trotta et al. 1997; Phizicky and Hopper 2010). Sen2 and Sen34 are conserved from Archaea to humans (Kleman-Leyer et al. 1997; Trotta et al. 1997; Paushkin et al. 2004); however, the archaeal endonucleases are composed of α2 homodimers, α4 homotetramers, or (αβ)2 heterodimers (reviewed in Abelson et al. 1998). Sen15 and Sen54 are poorly conserved between yeast and vertebrate cells (Paushkin et al. 2004) and are absent from the archaeal genomes.

Figure 2.

Pre-tRNA splicing in budding yeast. The same color codes are used as for Figure 1. Introns (yellow circles) are located after nucleotide 37 and they are removed in a three-step process—endonucleolytic removal of the intron, ligation, and removal of the residual 2′ phosphate at the splice junction—as detailed in the text.

Studies of the mechanism of the tRNA splicing nuclease were aided by conditional mutations of SEN2 (Winey and Culbertson 1988; Ho et al. 1990). As, at the nonpermissive temperature, cells with the sen2-3 allele accumulated 2/3 molecules containing the tRNA 5′ exon and intron, Sen2 was implicated in cutting at the 5′ splice site (Ho et al. 1990). Indeed, it was subsequently learned that Sen2 and Sen34 are the catalytic subunits of the splicing endonuclease and that they are responsible for cleavage at the 5′ and 3′ splice sites, respectively (Trotta et al. 1997) (Figure 2). Thus, the heterotetramer contains two active subunits with different specificity. Structural studies showed that catalysis requires a composite active site generated by both Sen2 and Sen34 (Trotta et al. 2006). The functions of yeast Sen15 and Sen54 are unknown, but they have been proposed to play roles in establishing the cleavage sites on the pre-tRNA (Trotta et al. 1997; Abelson et al. 1998; Trotta et al. 2006).

Two tRNA half molecules result from step one of the tRNA splicing reaction. The 5′ half possesses a 2′, 3′ cyclic phosphate and the 3′ half possesses a 5′ hydroxyl (Knapp et al. 1979; Peebles et al. 1983). Step two of the reaction is the ligation of the 5′ and 3′ exons and it is catalyzed by the yeast tRNA ligase, Trl1 (previously Rlg1) (Phizicky et al. 1986) (Figure 2). Ligation catalyzed by Trl1 is complicated. First, opening of the cyclic phosphate of the 5′ exon is catalyzed by the Trl1 cyclic phosphodiesterase activity; second, the 5′ terminus of the 3′ exon is phosphorylated via Trl1’s kinase activity using GTP; third, the 5′ terminus is activated by transfer of an AMP to the 5′ phosphate; and fourth, the ligase catalyzes joining of the two halves. The reaction results in the release of AMP and the creation of a splice junction with a 3′, 5′ phosphodiester bond derived from phosphate addition to the 3′ half and a 2′ residual phosphate at the splice junction derived from the 2′, 3′ cyclic phosphate of the 5′ exon (Greer et al. 1983; Abelson et al. 1998) (Figure 2).

The residual 2′ phosphate at the splice junction is removed in the third step of splicing, which is catalyzed by the 2′ phosphotransferase, encoded by TPT1 (Spinelli et al. 1997) (Figure 2). Tpt1 transfers this 2′ phosphate to NAD+ to create a novel metabolic intermediate, ADP-ribose 1′′, 2′′-cyclic phosphate (McCraith and Phizicky 1991; Culver et al. 1993).

The complicated yeast tRNA splicing ligation mechanism is conserved in plants (Gegenheimer et al. 1983; Schwartz et al. 1983; Culver et al. 1994; Englert and Beier 2005). However, vertebrates and Archaea ligate the tRNA halves directly by a 3′–5′ ligase activity. In vertebrates, the reaction is catalyzed by a protein complex with HSPC117 as an essential component (Popow et al. 2011, 2012). The ligase joins the phosphate from the 2′, 3′ cyclic bond to the 5′ hydroxyl on the 3′ half molecule, bypassing the need for a 2′ phosphotransferase. Thus, even though step one of tRNA splicing is conserved from Archaea, to yeast, to plants, to vertebrates, completion of the splicing reaction in yeast and plants requires two steps, 5′–3′ ligation and 2′ phosphotransferase, whereas in Archaea and vertebrates, completion requires a single one-step ligation.

Multiple functions and cellular distribution of yeast splicing enzymes:

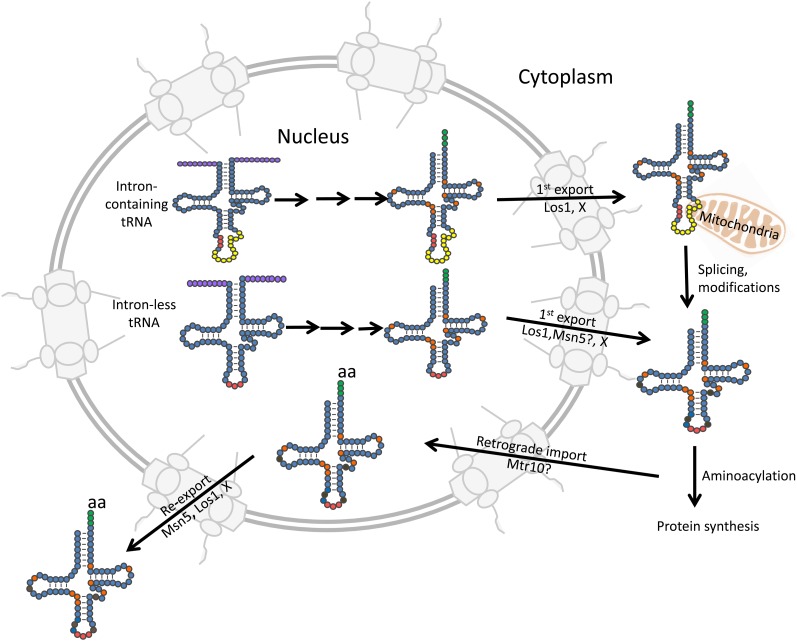

In vertebrates, pre-tRNA splicing occurs in the nucleoplasm (Melton et al. 1980; Lund and Dahlberg 1998). Surprisingly, yeast tRNA splicing endonuclease and tRNA ligase are not located in the nucleus. Rather, tRNA splicing endonuclease is located on the outer surface of mitochondria (Huh et al. 2003; Yoshihisa et al. 2003), the tRNA ligase is distributed throughout the cytoplasm (Huh et al. 2003; Mori et al. 2010), and the 2′ phosphotransferase is located in both the nucleus and the cytoplasm (Dhungel and Hopper 2012). In an elegant series of experiments, Yoshihisa et al. (2007) employed a reversible temperature-sensitive (ts) sen2 allele and a pulse-chase regime to demonstrate that unspliced cytoplasmic pre-tRNAs accumulated at the nonpermissive temperature are spliced when cells are returned to permissive temperature. The combined data provide very strong evidence that tRNA splicing in yeast occurs in the cytoplasm (Yoshihisa et al. 2003, 2007) (Figure 3; Table 1). The results provided an explanation as to why end-matured intron-containing pre-tRNAs accumulate in yeast mutant strains, rna1-1 and los1Δ, with defects in tRNA nuclear export (Hopper et al. 1978, 1980) because in these mutant strains the pre-tRNAs that are located in the nucleus do not have access to the cytoplasmic tRNA splicing machinery.

Figure 3.

tRNA subcellular dynamics. tRNAs are drawn in their second cloverleaf structure. The color coding of nucleotides is the same as for Figure 1 and Figure 2 except some nucleosides that occur in the nucleus are orange, whereas representative nucleoside additions that occur in the cytoplasm are brown. Pre-tRNAs are transcribed in the nucleus where leader and trailer sequences (purple) are removed prior to CCA (green) addition. End matured, partially modified intron-containing pre-tRNAs are exported to the cytoplasm by Los1 and at least one unknown exporter. Those pre-tRNAs encoded by genes lacking introns are likely exported by both Los1 and Msn5. Splicing and additional modifications occur after export to the cytoplasm. Cytoplasmic tRNAs constitutively return to the nucleus via retrograde transport. Mtr10 functions in tRNA retrograde import but it is unknown whether its role is direct or indirect. Imported tRNAs accumulate in the nucleus if cells are deprived of nutrients; otherwise they are reexported to the cytoplasm by Los1, Msn5, and at least one unidentified exporter. See text for details.

To investigate the reason for the different subcellular distributions of the tRNA splicing reaction in yeast vs. vertebrate cells, yeast cells were reengineered to splice tRNAs in the nucleus (Dhungel and Hopper 2012). This was accomplished by providing each Sen subunit with nuclear targeting information. Not surprisingly, if the tRNA splicing machinery is located in the nucleus, pre-tRNAs are spliced at this location. Cells that contain both the nuclear-localized and the cytoplasmic-localized splicing machinery grow well, documenting that pre-tRNA splicing in the nucleus is not harmful to yeast. Yeast possessing only the nuclear-localized splicing machinery splice pre-tRNAs efficiently; the tRNAs are efficiently exported to the cytoplasm and aminoacylated, and are apparently stable. Surprisingly, however, yeast cannot grow without mitochondrial-localized tRNA splicing endonuclease (Dhungel and Hopper 2012).

The data indicate that the tRNA splicing endonuclease has an essential function in the cytoplasm that is unrelated to pre-tRNA splicing. Indeed, cells with defective mitochondrial-located tRNA splicing endonuclease have aberrant pre-ribosomal (pre-rRNA) processing, even when tRNA splicing occurs efficiently in the nucleus (Volta et al. 2005; Dhungel and Hopper 2012). The role of the tRNA splicing endonuclease in this process must be indirect because one of the steps of pre-rRNA processing that is aberrant when the mitochondrial-located tRNA splicing endonuclease is defective normally occurs in the nucleolus (Dhungel and Hopper 2012). One possibility is that the tRNA splicing endonuclease may indirectly function in pre-rRNA processing via maturation of small nucleolar RNAs (snoRNAs) in the cytoplasm.

tRNA ligase also serves a function in addition to ligation of tRNA halves in yeast. It is required for the regulated nonconventional protein catalyzed splicing of HAC1 mRNA that is involved in the unfolded protein response (Sidrauski et al. 1996). Ire1 acts as the site-specific endonuclease that removes the HAC1 mRNA intron, generating a 5′ half with a 2′, 3′ cyclic phosphate and a 3′ half with a 5′ hydroxyl. The mRNA halves are joined by tRNA ligase and the residual 2′ phosphate at the splice junction is presumably removed by Tpt1 (Gonzalez et al. 1999). As the HAC1 mRNA splicing reaction occurs on polyribosomes, Trl1 has the predicted cytoplasmic location. Splicing of the HAC1 mRNA vertebrate homolog XBP1 also occurs by the nonconventional protein catalyzed mechanism, but the ligase has not been defined (Uemura et al. 2009).

The third enzyme for yeast tRNA splicing, Tpt1 − 2′ phosphotransferase, likely also serves a function other than for pre-tRNA splicing. In addition to its cytoplasmic pool, there is a nuclear Tpt1 pool (Dhungel and Hopper 2012). Since pre-tRNA splicing normally occurs in the cytoplasm, the nuclear Tpt1 pool presumably serves a role other than for tRNA splicing. Likewise, the 2′ phosphotransferase is conserved in vertebrates that do not require this enzyme for pre-tRNA splicing (Spinelli et al. 1998; Harding et al. 2008) and in bacterial genomes that do not encode any tRNA genes with introns (Spinelli et al. 1998; Steiger et al. 2001). Thus, it seems very likely that each of the three enzymes required for splicing yeast pre-tRNAs moonlights in a process distinct from tRNA splicing.

tRNA modification

tRNAs are highly modified. There are a plethora of known tRNA nucleoside modifications, ∼85 across all kingdoms (reviewed in El Yacoubi et al. 2012). A subset of 25 occur for yeast tRNAs (Phizicky and Hopper 2010) (Table 1). Sequenced yeast nuclear encoded tRNAs possesses a range of 7–17 modifications (Phizicky and Hopper 2010). Therefore, >15% of the nucleosides in yeast cytoplasmic tRNAs are not A, U, G, or C. The distribution of the modifications among tRNA families has been recently reviewed (Phizicky and Hopper 2010; El Yacoubi et al. 2012) and compiled at http://modomics.genesilico.pl/sequences/list/tRNA. The roles of tRNA modifications were mysterious for decades. However, due to the combination of conventional genetic screens (e.g., Phillips and Kjellin-Straby 1967; Laten et al. 1978), biochemical genomics (Martzen et al. 1999; Winzeler et al. 1999; Phizicky and Hopper 2010), and bioinformatics (e.g., Gustafsson et al. 1996), nearly the entire proteome that catalyzes these post-transcriptional additions to tRNAs has been identified and characterized. However, new discoveries continue to be made; for example, it has very recently been shown that the universally conserved modification N6-threonylcarbamoyladenosine (t6A) is actually an hydrolyzed form of cyclic t6A (ct6A); in vivo conversion of t6A to ct6A requires two newly discovered gene products, Tcd1 and Tcd2 (Miyauchi et al. 2013).

Functions for tRNA modifications:

It is now appreciated that tRNA modifications serve diverse functions including: tRNA discrimination, translational fidelity via codon–anticodon interaction, and maintenance of reading frame, and tRNA stability. Despite the important roles and the fact that many modification enzymes are highly conserved, most of the yeast genes encoding tRNA modification enzymes are unessential. Of the scores of yeast genes that function in tRNA modification, only those responsible for adenosine A34 to inosine I34 deamination (TAD2 and TAD3) and methylation of adenosine m1A58 (TRM6 and TRM61) are essential (Anderson et al. 1998; Gerber and Keller 1999). Deletions of five additional genes encoding other modification enzymes [e.g., TRM5 (m1G37), TRM7 (Cm32, Cm34, Gm34, ncm5Um34), SUA5 (ct6A37), PUS3 (ψ38, ψ39), and TAN1 (ac4C12)] result in slow or conditional growth (Phizicky and Hopper 2010) (Table 1; Figure 4).

Modifications can function in discrimination of tRNAs during translation. For example, all cells encode separate tRNAMet species that function in either the initiation or the elongation steps of translation. The initiator and elongator tRNAMet, tRNAiMet, and tRNAeMet, respectively, have different primary sequences and structures, but both are aminoacylated by a single methionyl tRNA synthetase, Mes1. They are discriminated at translation via their interactions with translation factors—tRNAiMet interaction with initiator factor 2 (eIF2) and tRNAeMet interaction with elongator factor 1 (eEF1α). A genetic screen to identify factors involved in discrimination between tRNAiMet and tRNAeMet identified RIT1. rit1 cells can function without tRNAeMet because in these mutant cells, tRNAiMet can decode internal AUG codons of open reading frames. By interacting with the T-stem loop that is unique to tRNAiMet, Rit1 catalyzes ribosylation of adenosine 64 [Ar(p)64] of tRNAiMet (Astrom and Bystrom 1994). Modified tRNAiMet does not interact with eEF1α, thereby resulting in tRNAiMet functioning only at initiating AUG codons (Shin et al. 2011).

tRNA modifications also function in codon–anticodon interactions and reading frame maintenance. Modifications of the anticodon at positions 34–36 affect decoding. A well-studied example of tRNA modification affecting decoding is the deamination of adenosine (A) to inosine (I) at wobble position 34. As A only base pairs with U, but I base pairs with U, C, and A, tRNAs with I at the wobble position have an extended codon–anticodon interaction capability and the absence of I results in decoding errors (Gerber and Keller 1999 and references therein). Likewise, the absence of pseudouridine (ψ) at tRNATyr position 35 or m5C34 in tRNALeuCAA causes defects in tRNA-mediated nonsense suppression (Johnson and Abelson 1983; Strobel and Abelson 1986). Alterations of other modifications at position 34 such as ncm5Um34 result in sensitivity to the aminoglycoside antibiotic paromomycin that causes misreading of near cognate codons (Kalhor and Clarke 2003). Some of the subunits of the enzyme responsible for ncm5Um34 and ncm5s2U34 modification were previously identified as components of the elongator complex that functions in transcriptional elongation, silencing at telomeres, and DNA damage response; it since has been shown that the phenotypes are indirect consequences of wobble position errors in translation of proteins that function in these processes (Chen et al. 2011). Similarly, mutations of genes encoding proteins of the KEOPS complex cause growth defects and telomere shortening. However, the KEOPS complex along with Sua5 is required for ct6A modification, which functions in decoding ANN codons, including appropriate initiation at AUG (Daugeron et al. 2011; El Yacoubi et al. 2012; reviewed in Hinnebusch 2011; Srinivasan et al. 2011).

Oxidative or heat stress can result in changes in tRNA modification which, in turn, can result in translational reprogramming (Kamenski et al. 2007; Chan et al. 2012). Trm4 catalyzes m5C modification of tRNALeuCAA at the wobble position 34 upon oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide. m5C-modified tRNALeuCAA results in increased translation of UUG, thereby increasing levels of at least one protein whose message is rich in UUG codons (Chan et al. 2012). Loss of Trm4 results in sensitivity to paromomycin and oxidative stress (Wu et al. 1998; Chan et al. 2012).

Modifications in the anticodon loop besides anticodon residues 34–36 also affect decoding. For example, defects of Mod5 that catalyzes isopentylation (i6A37) of a subset of tRNAs causes a decrease in nonsense suppression of UAA by mutant suppressor tRNAsTyr (Laten et al. 1978; Dihanich et al. 1987). Modifications in the anticodon loop can also affect the reading frames during translation. For example, mutations of the genes responsible for (yW) modification of tRNAPhe at position 37 cause increases in −1 frameshifting (Waas et al. 2007).

Some modifications are necessary for tRNA stability. For example, methylation of m1A58 of tRNAiMet, via Trm6/Trm61 catalysis, is essential for its stability (Anderson et al. 1998) (see below for details). Moreover, severe phenotypes are known to occur when cells possess mutations of multiple modification genes. This was first demonstrated for the unessential gene PUS1, required for ψ modification at positions 26–28, 34–36, 65, and 67. Synthetic lethality or temperature-sensitive growth results when pus1Δ cells also possess a mutation of the unessential pseudouridase, PUS4 (required for ψ55) (Grosshans et al. 2001). Such synthetic phenotypes may be rather common as simultaneous trm4Δ trm8Δ mutations (defects in m5C, which, depending on the tRNA, can be located at positions 34, 40, 48, and/or 49, and m7G46, respectively), trm44Δ tan1Δ mutations (defects in Um44 and ac4C12, respectively), or trm1Δ trm4Δ (defects in m22G26 and m5C, respectively) cause temperature-sensitive growth phenotypes (Alexandrov et al. 2006; Dewe et al. 2012). The Phizicky group (Alexandrov et al. 2006; Kotelawala et al. 2008; Dewe et al. 2012) has shown that the temperature-sensitive growth is caused by instability of a subset of the tRNAs bearing modifications normally encoded by both genes of the pairs. Turnover is mediated by the 5′ to 3′ rapid tRNA decay (RTD) pathway (Alexandrov et al. 2006), discussed in detail below. Thus, tRNA modifications are key for tRNA stability.

tRNA modification enzymes serve functions beyond tRNA discrimination, decoding, and tRNA stability. For example, genetic studies uncovered a connection between tRNA modification and the sterol biosynthesis pathway. Mod5, is responsible for modification of A37 to i6A37 via transfer of dimethylallyl pyrophosphate to tRNA. i6A37 is required for efficient nonsense suppression by SUP7 tRNATyr. A selection for high copy genes that resulted in reduced nonsense suppression in cells with a sensitized partially defective Mod5 (mod5-M2) uncovered ERG20 (Benko et al. 2000). Erg20 catalyzes conversion of the same intermediate, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate, to farnesyl pyrophosphate, a precursor of sterols and other products in the mevalonate pathway. Overexpression of Erg20 increases flux of the intermediate into the sterol pathway, resulting in reduced isopentylation of tRNATyr and altered translation (Benko et al. 2000). Moreover, recent studies showed that Mod5 can achieve a prion state and that this regulates the sterol biosynthesis pathway, indicating that environmental alterations impacting upon Mod5 structure affect the sterol biogenesis pathway (Suzuki et al. 2012). Thus, sterol biosynthesis and modification of i6A37 utilize the same intermediate and the two pathways compete, thereby connecting tRNA modification with sterol metabolism.

tRNA modification enzymes:

The majority of tRNA modification enzymes are composed of a single subunit (Table 1). In particular, each of the four dihydrouridine synthetases, each of the six pseudouridine synthetases, the i6A37 isopentenyltransferase, and the Rit1 A64 ribosyltransferase is a monomer or homopolymer. In contrast, some tRNA methyltransferases are composed of a single subunit, whereas others, such as those catalyzing m1A58, m7G46, and m2G10 methylations, are heterodimers. Likewise, A to I37 modification requires a single gene product, Tad1 (Gerber et al. 1998), but A to I34 modification is catalyzed by the Tad2 Tad3 heterodimer; both Tad2 and Tad3 contain deaminase motifs (Gerber and Keller 1999). Other modification activities have complex structures; for example, yW modification requires 5 polypeptides, whereas biosynthesis of mcm5s2U34, mcm5U34, and derivatives requires >25 polypeptides (Phizicky and Hopper 2010). Perhaps the most bizarre modification enzyme is Trm140, responsible for m3C32 modification of tRNASer, tRNAThr, and tRNAArg; it is generated by a programmed +1 frameshift that generates an N-terminal fusion of Abp140, an actin binding protein, to the C-terminal domain responsible for the methyltransferase activity (D’Silva et al. 2011; Noma et al. 2011).

Interestingly, some of the modification activities possess a second subunit that is responsible for site selection on the tRNA or for activation of the modification activity (Table 1). For example, the Trm7 Trm732 heterodimer is responsible for 2′O methylation of C32 (Cm32), whereas the Trm7 Trm734 heterodimer is responsible for 2′O methylation at position 34 (Cm34/Gm34 and ncm5Um34), indicating that Trm734 and Trm732 direct correct nucleoside modification sites (Guy et al. 2012). Moreover, Trm112 is the activating subunit for both Trm9 and Trm11, required for mcm5U34/mcm5s2U34 and m2G10, respectively, as well as for Mtq2, required for methylation of protein termination factor Sup45 and Bud23, required for rRNA G1575 methylation (Phizicky and Hopper 2010; Liger et al. 2011; Figaro et al. 2012). Analyses of the Mtq2 Trm112 complex structure provide insights into how Trm112 might alter Trm9 structure and its activity (Liger et al. 2011).

There are numerous unresolved questions regarding the specificity of the tRNA modification activities, including whether an activity modifies multiple or single types of substrates (e.g., tRNA vs. rRNA), whether an enzyme will catalyze modifications of single or multiple nucleosides on a given tRNA, or whether it will modify only a subset of the same nucleosides at the same position in different tRNAs. Some enzymes modify different types of RNA—“dual substrate specificity.” Examples include Pus1 and Pus7, which are pseudouridine synthases for both U2 snRNA and tRNAs (Massenet et al. 1999; Behm-Ansmant et al. 2003). However, most tRNA modification enzymes have unique specificity for tRNA. Some enzymes can modify a tRNA at multiple positions—“multisite substrate specificity” (Table 1). For example, Pus1 modifies U to ψ at several positions (ψ26–28, 34–36, 65, and 67) (Motorin et al. 1998). Other modification enzymes, like Pus4 and Pus6, which are also pseudouridine synthetases, modify only a single site, ψ55 and ψ31, respectively. Why a subset of modification enzymes might have multisubstrate or multisite specificity, whereas others have a restricted specificity, is unknown.

Another specificity question concerns the presence or absence of introns. Intron-requiring tRNA modification sites are modified only prior to splicing, whereas other modifications require the intron to first be removed. Intron-requiring modification sites include m5C34, m5C40, ψ34, ψ35, and ψ36 (Figure 4, magenta residues); whereas Gm18, Cm32, ψ32, m1G37, i6A37, and Um44 modifications occur only after splicing (Figure 4, brown residues). Numerous other modifications can occur either on intron-containing or intron-lacking substrates in vitro (Grosjean et al. 1997). A final question regarding specificity is whether a given modification requires a prior different modification(s). Until recently there were no known examples of this type of specificity; however, it has now been shown that completion of yW modification at position 37 of tRNAPhe requires prior modification of Gm34 by Trm7 (Guy et al. 2012).

Cell biology of tRNA modifications:

Unlike mRNA processing, which generally occurs on chromatin coupled with transcription, tRNA biogenesis occurs at multiple subcellular sites (Figure 3). The enzymes that modify intron-requiring sites (Figure 4, magenta residues), Pus1 (ψ34–36) and Trm4 (m5C34, m5C40), necessarily reside in the nucleus where intron-containing pre-tRNAs are located; there appears to be no cytoplasmic pools of these proteins (Hopper and Phizicky 2003; Huh et al. 2003). Likewise, Trm6 and Trm61, responsible for m1A58 modification that occurs on some tRNA initial transcripts (Figure 4, solid black circle on initial transcript), are located in the nucleus (Anderson et al. 2000). It was predicted that modifications that occur only after splicing (Figure 4, brown residues) would be catalyzed by enzymes that reside in the cytoplasm. Indeed, many of these enzymes including Trm3 (Gm18), Trm7 (Cm32 and Nm34), Pus8 (ψ32), and Trm44 (Um44) are cytoplasmic (Hopper and Phizicky 2003; Huh et al. 2003). However, part of the cellular pool of Mod5 (i6A37), which modifies only spliced tRNA, is located in the nucleolus (Tolerico et al. 1999) and Trm5 (m1G37, m1I37), which also only modifies spliced tRNA, is paradoxically located in the nucleus and mitochondria, but not the cytoplasm (Lee et al. 2007; Ohira and Suzuki 2011) (see tRNA trafficking below for a discussion). Some modification enzymes able to modify either intron-containing or intron-lacking tRNAs are located in the nucleus [e.g., Trm1 m22G26 (Lai et al. 2009); Dus1 (D16, 17), (Etcheverry et al. 1979; Huh et al. 2003); Pus3 (ψ38, 39) (Etcheverry et al. 1979; Huh et al. 2003)] (Figure 4, orange residues); others appear to be primarily cytoplasmic [e.g., Trm11/Trm112 (m2G10) (Huh et al. 2003)] (Figure 4, khaki residue). The subcellular locations of yet other modification enzymes remain unstudied (Figure 4, open residues). The subcellular distribution of the tRNA modification enzymes dictates an ordered pathway for tRNA modification (Figure 4), even though, with the exception of yW modification, there is no known biochemical requirement for ordered modifications.

Both nuclear-encoded and mitochondrial-encoded tRNAs are modified. Single genes can encode modification activities located in the nucleus/cytoplasm as well as in mitochondria. The first examples of this were Mod5 (i6A37), Trm1 (m22G26), and Trm2 (m5U54) (Hopper et al. 1982; Martin and Hopper 1982), but such dual targeting is now known to be rather common (reviewed in Yogev and Pines 2011). Mod5 is regulated at the translational level to produce two proteins; the N-terminal extended form is targeted to the mitochondria and the shorter form resides in the cytoplasm and nucleolus (Boguta et al. 1994; Tolerico et al. 1999). Trm1 is regulated at the transcriptional level; 5′ extended transcripts encode the N-terminal extended form located in the mitochondria and short transcripts encode the nonextended form located primarily at the inner nuclear membrane (Ellis et al. 1989; Rose et al. 1992, 1995; Lai et al. 2009). Similarly, Pus3, Pus4, Pus6, and Trm5 modify both cytoplasmic and mitochondrial tRNAs (Behm-Ansmant et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2007 and reference therein). To date, only Pus9 (ψ32) and Pus2 (ψ27, 28) appear to be dedicated to mitochondrial tRNA modification (Behm-Ansmant et al. 2004, 2007).

In sum, it is an exciting time for studies of tRNA modification. Not so long ago, tRNA modifications enzymes were known to be rather conserved, but since the genes are generally unessential, the biological functions of the modifications were mysterious. As detailed above, it is now clear that tRNA modifications have numerous roles in tRNA function and tRNA stability. Studies of tRNA modifications have uncovered their roles in important processes and stress responses and their connections with other metabolic processes. Studies of the biochemistry of the modification activities are providing novel information regarding protein–RNA specificity and studies of the cell biology of modification enzymes provide mechanisms for ordered pathways and interesting questions regarding coordination of mitochondrial and cytoplasmic metabolism.

tRNA Turnover and Cleavage

tRNAs are stable with half-lives estimated to be from ∼9 hr to up to days (Anderson et al. 1998; Phizicky and Hopper 2010; Gudipati et al. 2012). So it is surprising that two separate pathways for tRNA turnover have been discovered (reviewed in Phizicky and Hopper 2010; Maraia and Lamichhane 2011; Parker 2012; Wolin et al. 2012). Both tRNA turnover pathways appear to function in tRNA quality control, eliminating tRNAs that are inappropriately processed, modified, or folded (Figure 5).

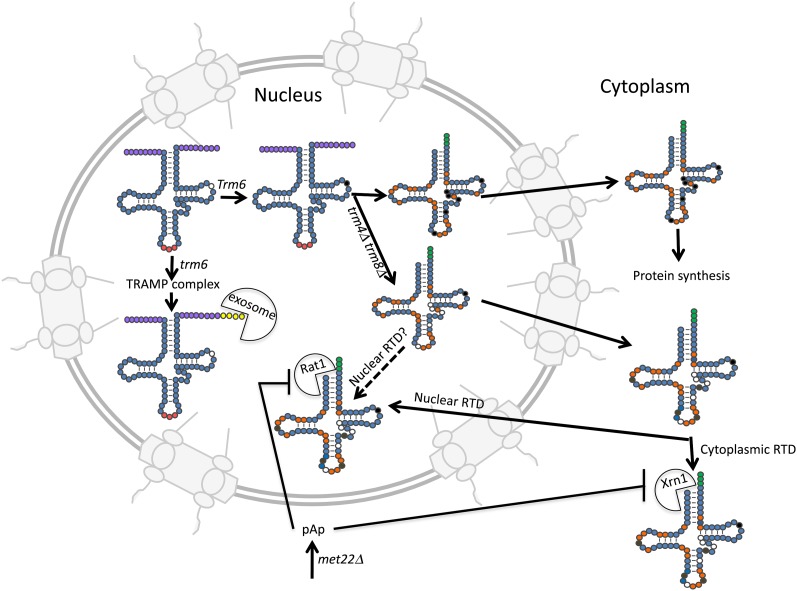

Figure 5.

tRNA turnover pathways in S. cerevisiae. Initial tRNA transcripts with 5′ and 3′ extensions (purple circles) are substrates for 3′ to 5′ exonucleolytic degradation by the nuclear exosome if the transcripts are missing a particular modification, m1A58 (open circle on initial tRNA transcript) or if 3′ processing is aberrant (not shown). The unmodified/aberrant tRNAs first receive A residues at the 3′ end (yellow circles) by the activity of the TRAMP complex and then the tRNAs are degraded by the nuclear exosome (exosome pac-man). Aberrant tRNAs can also be degraded by the rapid tRNA turnover pathway (RTD) in either the nucleus or the cytoplasm. The RTD pathway acts upon tRNAs missing particular multiple modifications or tRNAs that are otherwise unstructured (see text). As an example, tRNAs missing multiple modifications (open circles) due to trm4Δ trm8Δ mutations are subject to 5′ to 3′ degradation by the exonucleases in either the nucleus (RAT1 pac-man) or in the cytoplasm (Xrn1 pac-man). Solid circles are those modifications affected by mutations of TRM6 or TRM4 and TRM8. Orange circles indicate modifications acquired in the nucleus, whereas brown circles indicate modifications acquired in the cytoplasm. CCA nucleotides are indicated by green circles and the anticodon by red circles. Also indicated is pAp, an intermediate of methionine biosynthesis that inhibits Xrn1 and Rat1, thereby connecting tRNA turnover to amino acid biosynthesis.

3′-5′ exonucleolytic degradation by the nuclear exosome

The role of 3′ to 5′ exonucleolytic degradation via the nuclear exosome in tRNA turnover followed the discovery that tRNAiMet is unstable if it lacks m1A58 caused by mutation of TRM6/TRM61 (Anderson et al. 1998, 2000). Selection for suppressors of the conditional lethal phenotype of trm6 ts mutations uncovered rrp44, encoding a nuclease that is a component of the nuclear exosome and trf4, encoding a noncononical poly(A) polymerase. The data led to the model, subsequently proven, that precursor hypomodified tRNAiMet is 3′ polyadenylated by Trf4 and the poly(A)-containing tRNA is degraded by the nuclear exosome (Kadaba et al. 2004, 2006) (Table 1; Figure 5). Poly(A) tails on mRNA generally specify stability; however, in E. coli RNA turnover also proceeds by poly(A) addition (Mohanty and Kushner 1999). Trf4-mediated poly(A) addition is also involved in the turnover of other types of aberrant transcripts (Kadaba et al. 2006). Turnover requires Mtr4, a RNA-dependent helicase (Wang et al. 2008; Jia et al. 2011), and other proteins comprising the TRAMP complex including the two poly(A) polymerases, Trf4 and Trf5, which have overlapping as well as nonoverlapping substrate specificities (San Paolo et al. 2009), and either Air1 or Air2, RNA binding proteins also with both overlapping and nonoverlapping specificities (Schmidt et al. 2012). The activated substrate-containing TRAMP complex interacts with the nuclear exosome that contains two nucleases, Rrp6 and Rrp44, and numerous other proteins (Parker 2012). Interestingly, there appears to be competition between appropriate processing of pre-tRNA 3′ trailer sequences by Rex1 and degradation by the TRAMP/nuclear exosome machinery (Copela et al. 2008; Ozanick et al. 2009). Thus, this 3′ to 5′ turnover machinery likely serves as a quality control pathway that monitors both appropriate tRNA nuclear modification as well as 3′ end maturation. Recent genome-wide studies indicate that as much as 50% of pre-tRNAs may be rapidly degraded by the exosome (Gudipati et al. 2012).

5′ to 3′ exonucleolyic degradation by the RTD pathway

Most yeast genes encoding tRNA modification activities are unessential; however, as discussed above, simultaneous deletion of two such genes can result in synthetic negative phenotypes such as temperature-sensitive growth (Grosshans et al. 2001; Alexandrov et al. 2006; Kotelawala et al. 2008). The Phizicky group showed that the growth defects result from tRNA turnover (Phizicky and Hopper 2010). Remarkably, the targeted mature tRNAs, which normally have half-lives in the order of hours to days, are degraded on the minute to hour time scale, similar to mRNA half-lives. Thus, tRNAValAAC in trm4Δ trm8Δ cells lacking m5C49 and m7G46, or tRNASerCGA and tRNASerUGA in trm44Δ tan1Δ cells lacking Um44 and ac4C12, are rapidly degraded (Alexandrov et al. 2006; Kotelawala et al. 2008). Degradation is not inhibited by alterations of the TRAMP complex, eliminating a role of the 3′ to 5′ exonuclease machinery in this process (Alexandrov et al. 2006). Rather, mutations of rat1 and xrn1, encoding 5′ to 3′ exonucleases and met22 were isolated as suppressors of the temperature-sensitive growth and thereby defined gene products that function in this RTD (Chernyakov et al. 2008) (Table 1; Figure 5). Rat1 resides in the nucleus and Xrn1 in the cytoplasm, indicating that RTD can occur either in the nucleus or the cytoplasm. Met22 is an enzyme in the methionine biosynthesis pathway and met22 cells accumulate a byproduct of the pathway, pAp (adenosine 3′, 5′ bisphosphate), which inhibits Xrn1 and Rat1 activities (Dichtl et al. 1997) (Figure 5). Therefore, tRNA quality control is somehow connected to amino acid biosynthesis.

The specificity of the RTD pathway has been investigated. As predicted, only those unmodified tRNAs that normally contain modifications catalyzed by both Trm8 and Trm4 or Trm44 and Tan1 are substrates for RTD in trm8Δ trm4Δ or trm44Δ tan1Δ cells. However, the RTD machinery does not degrade some unmodified tRNAs that normally bear the relevant modifications. To address this problem, Whipple et al. (2011) compared two tRNASer species, both of which are modified by Trm44 and Tan1, but one, tRNASerIGA, is not a RTD substrate, whereas the other, tRNASerCGA, is a RTD target. In vivo and in vitro data showed that tRNASerCGA gained immunity to RTD when nucleotides of tRNASerCGA were replaced with tRNASerIGA nucleotides that enhanced the stability of the acceptor and T-stems. Thus, Um44 and ac4C12 on tRNASerCGA enhance tRNASerCGA stability, protecting it from RTD. The data underscore the role of the RTD machinery as a monitor of correct tRNA structure and the role of tRNA modification in stabilizing tRNA tertiary structure. The studies likely also provide a possible explanation for earlier studies reporting the temperature-sensitive SUP4 mutation (Whipple et al. 2011), temperature-sensitive growth and reduced tRNAGlnCUG levels in cells with a mutation of pus1 and a destabilized tRNAGlnCUG (Grosshans et al. 2001), and the synthetic effects of defects in tRNA modification and sensitivity to 5-fluorouracil (Gustavsson and Ronne 2008).

Interestingly, there appears to be competition between the RTD pathway and translation factor eEF1α, as elevated eEF1α levels can suppress defects caused by mutations of modification enzymes and decreased levels of eEF1α can result in turnover of tRNAs in cells missing single modification activities such as Trm1 (Dewe et al. 2012; Turowski et al. 2012). Thus, the ability of tRNAs to interact with tRNA binding proteins also provides immunity from the RTD surveillance turnover machinery.

A remaining question regarding the RTD pathway concerns the subcellular location of tRNA degradation. It appears that nuclear Rat1 and cytoplasmic Xrn1 individually contribute to tRNA turnover as tRNAs are partially stabilized in either xrn1Δ or rat1–107 cells and tRNAs are most completely stabilized when Rat1 and Xrn1 are simultaneously altered or when cells are deleted for MET22 (Chernyakov et al. 2008) (Figure 5).

Overlap of the RTD and TRAMP pathways and CCACCA addition?

The addition of CCA nucleotides to mature 3′ tRNA termini is prerequisite for tRNA aminoacylation and therefore required for tRNA biogenesis and function. However, deep sequencing of tRNAs from trm44Δ tan1Δ cells identified tRNASerCGA and tRNASerUGA with CCACCA (or CCAC or CCACC—“extended CCA motifs”) at their 3′ ends; the number of reads of RNAs with such extended CCA motifs was greater for RNAs from trm44Δ tan1Δ cells with hypomodified tRNA than for wild-type cells, which suggests that extended CCA motifs may define a novel intermediate in the RTD turnover process. Thus, surprisingly, the enzyme catalyzing CCA addition, Cca1, can also participate in tRNA quality control by extending tRNA 3′ ends. However, this mode of quality control cannot target all tRNAs because extended CCA motif addition requires that the 5′ end first two nucleotides are GG and only a small subset of yeast tRNAs meet this requirement (Wilusz et al. 2011).

Although both RTD and TRAMP/exosome turnover can occur in the nucleus, it was proposed that the substrate for the former is mature tRNA, whereas the substrate for the latter is pre-tRNA (Figure 5). In support of this, RTD components were not identified as trm6/trm61 suppressors and mutant TRAMP/exosome components have little effect on the stability of RTD tRNA substrates (Kadaba et al. 2004; Alexandrov et al. 2006). However, deep sequencing data detected tRNAs with 3′ extended CCA motifs followed by oligo(A) (Wilusz et al. 2011). The role of Cca1 in the tRNA quality control pathways and the interaction between the RTD and TRAMP/exosome pathways clearly warrants further investigation.

tRNA endonucleolytic cleavage

tRNA endonucleolytic cleavage generating 5′ and 3′ approximately half-size molecules occurs in numerous organisms, as first demonstrated in C. elegans (Lee and Collins 2005; reviewed in Thompson and Parker 2009a; Parker 2012). Generally the half-size tRNA pieces accumulate when cells are nutrient deprived or otherwise stressed. In vertebrate cells, stress induces angiogenin-mediated tRNA cleavage, producing tRNA half molecules that can inhibit initiation of protein synthesis (Ivanov et al. 2011). In budding yeast, tRNA cleavage is induced upon oxidative stress and/or high cell density and it is catalyzed by endonuclease Rny1, an RNase T2 family member, which normally resides in vacuoles (Thompson and Parker 2009b). Either Rny1 is released from the vacuole to access tRNAs in the cytoplasm or tRNA is targeted to the vacuoles where Rny1 is located (Thompson and Parker 2009b; Luhtala and Parker 2012). Curiously, accumulation of tRNA halves in yeast does not appear to affect the pool of mature full-length tRNAs (Thompson et al. 2008; Thompson and Parker 2009a); this is difficult to understand unless there is normally a pool of half molecules that turn over exceedingly fast except under stress conditions. The function of stress-mediated tRNA cleavage in yeast is unclear but may be involved in ribophagy as part of the autophagy process (Thompson et al. 2008; Andersen and Collins 2012).

Interestingly, tRNA anticodon loop modifications can influence tRNA endonucleolytic cleavage. For example, the Kluyveromyces lactis γ-toxin, is a secreted endonuclease that inhibits growth of sensitive microbes such as S. cerevisiae. γ-Toxin cleaves tRNAs that possess mcm5s2U modification at the wobble position. S. cerevisiae with mutations of genes in the mcm5s2U biosynthesis pathway are resistant to γ-toxin (Huang et al. 2008 and references therein). Conversely, tRNAs modified by the Dnmt2 m5C methylase are protected from stress-induced angiogenin-mediated endonucleolytic cleavage in Drosophila and mice (Schaefer et al. 2010). The Dnmt2 methylase is widespread throughout nature, including the yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe, but curiously appears to be absent from S. cerevisiae (Jurkowski and Jeltsch 2011).

In less than a decade the view of tRNAs as exceedingly stable molecules with no known mechanism for turnover has completely changed. It is now clear that there are multiple means of destroying tRNAs. Turnover serves as a quality control pathway to assure that only appropriately mature and functional tRNAs engage with the protein synthesis machinery and also to produce intracellular signaling molecules for stress response. Many questions remain, regarding the cell biology and interaction of the turnover pathways and the function of tRNA cleavage.

tRNA Subcellular Trafficking

Nuclear-encoded tRNAs function in protein synthesis in the cytoplasm. There is a rich history of research, in both yeast and vertebrate cells, exploring the mechanism(s) to export nuclear-encoded tRNAs to the cytoplasm (reviewed in Gorlich and Kutay 1999; Simos and Hurt 1999; Grosshans et al. 2000b; Yoshihisa 2006; Hopper and Shaheen 2008; Hopper et al. 2010; Phizicky and Hopper 2010; Rubio and Hopper 2011; Lee et al. 2011). Moreover, the studies have generated numerous unanticipated discoveries. It is now known that tRNAs can be aminoacylated in the nucleus (Lund and Dahlberg 1998; Sarkar et al. 1999; Grosshans et al. 2000a), that tRNAs can traffic from the cytoplasm to the nucleus via the tRNA retrograde process (Shaheen and Hopper 2005; Takano et al. 2005; Zaitseva et al. 2006), and that tRNAs imported into the nucleus can be reexported to the cytoplasm (Whitney et al. 2007; Eswara et al. 2009) (Figure 3). tRNA subcellular traffic is conserved (Zaitseva et al. 2006; Shaheen et al. 2007; Barhoom et al. 2011), responsive to nutrient availability (Shaheen and Hopper 2005; Hurto et al. 2007; Shaheen et al. 2007; Whitney et al. 2007; Murthi et al. 2010), and, in yeast, is coordinated with the formation of P-bodies in the cytoplasm (Hurto and Hopper 2011). In addition to the trafficking of tRNAs between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, some tRNAs encoded by the nucleus are imported into mitochondria (reviewed in Rubio and Hopper 2011; Schneider 2011). Here the amazing and complex tRNA trafficking machinery is described and the function(s) of the traffic is explored.

tRNA nuclear export

The vast majority of RNA movement from the nucleus to the cytoplasm occurs through nucleopores, aqueous channels connecting the two compartments, in an energy-dependent mechanism. Nuclear export of proteins, ribosomes, and tRNAs, but not mRNA, proceeds via the Ran pathway. Ran is a small GTPase that regulates exit through nuclear pores via its association with importin-β family members. Cells encode numerous importin-β family members, a subset of which is dedicated to the nuclear export process—exportins. The binding of RNA or protein cargo in the nucleus with an exportin family member is Ran-GTP dependent; after the cargo-exportin-Ran-GTP complex reaches the cytoplasm, the cargo is released from the complex via action of the cytoplasmic RanGAP, yeast Rna1, which activates hydrolysis of Ran-GTP to Ran-GDP.

Los1:

In vertebrates, the importin-β family member that functions in tRNA nuclear export is exportin-t (Arts et al. 1998a; Kutay et al. 1998). The yeast homolog is Los1, first identified by the los1 mutant (Hopper et al. 1980; Hellmuth et al. 1998; Sarkar and Hopper 1998). los1Δ cells accumulate end-processed intron-containing tRNAs due to defects in tRNA export from the nucleus to the cytoplasm where the splicing machinery is located (Sarkar and Hopper 1998; Yoshihisa et al. 2003, 2007). Despite the defect in tRNA nuclear export, los1Δ cells are viable, although they demonstrate reduced tRNA-mediated nonsense suppression (Hopper et al. 1980; Hurt et al. 1987). Thus, although exportin-t is regarded to be the major tRNA nuclear exporter in vertebrate cells, in yeast there are other exporters that function in parallel to Los1 to deliver tRNAs to the cytoplasm. The same is true in plants, as the Arabidopsis exportin-t homolog PAUSED is unessential (Hunter et al. 2003; Li and Chen 2003), and in insects that lack the exportin-t homolog (Lippai et al. 2000).

Studies of the binding capability of vertebrate exportin-t and crystallography studies of S. pombe Los1 in complex with tRNA and Ran-GTP showed that this exportin preferentially interacts with the appropriately structured tRNA backbone (the D and TψC loops of the L-shaped tertiary structure) as well as the mature tRNA 5′ and 3′ ends (Arts et al. 1998b; Lipowsky et al. 1999; Cook et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2011). Moreover, in vivo studies in S. cerevisiae demonstrated that tRNAs with altered sequence accumulate in the nucleus (Qiu et al. 2000). Thus, because stable Los1-tRNA complexes require mature structures of the tRNA backbone and aminoacyl stem, Los1 serves a quality control function inhibiting tRNAs with immature termini or misfolded tRNAs from accessing the cytoplasm and the protein synthesis apparatus.

Although exportin-t/Los1 monitors the tRNA backbone and aminoacyl stem, it does not monitor the anticodon stem as vertebrate exportin-t binds intron-containing and spliced tRNAs with equal affinity (Arts et al. 1998b; Lipowsky et al. 1999). In yeast, Los1’s in vivo interaction with intron-containing pre-tRNAs is evidenced by the fact that splicing in yeast occurs only after nuclear export on the outer surface of mitochondria and los1Δ cells accumulate intron-containing tRNA in the nucleus (Sarkar and Hopper 1998; Yoshihisa et al. 2003, 2007). To date, Los1 is the only known protein capable of delivering intron-containing pre-tRNA to the cytoplasm (Murthi et al. 2010). Since it is impossible to generate a complete set of tRNAs required for protein synthesis without delivering unspliced tRNAs to the cytoplasm, there is undoubtedly an undiscovered nuclear exporter for this category of tRNAs.

Under growth conditions with nonfermentable carbon sources or upon certain stresses there is a reduced level of tRNA in the cytoplasm. Part of this regulation is at the level of tRNA transcription and part is likely due to the regulation of Los1’s distribution between the nucleus and the cytoplasm. Maf1 negatively regulates tRNA transcription by its interaction with RNA polymerase III (reviewed in Willis and Moir 2007; Boguta and Graczyk 2011). In favorable growth conditions with fermentable carbon sources, Maf1 is inactive, but under growth conditions with nonfermentable carbon sources or other stresses, Maf1 is active and down-regulates Pol III-mediated tRNA transcription. The level of tRNA available for translation is also regulated by tRNA nuclear export. In wild-type cells grown with a fermentable sugar as the carbon source, Los1 is located primarily in the nucleus where it is able to interact with newly synthesized tRNA cargo, but when cells are grown in a nonfermentable carbon source or when the cells are stressed, Los1 is primarily cytoplasmic and hence unable to access newly transcribed tRNAs and deliver them to the cytoplasm (Quan et al. 2007; Karkusiewicz et al. 2012). The subcellular distribution of Los1 is also affected by DNA damage. Upon DNA damage, Los1 is primarily cytoplasmic (Ghavidel et al. 2007). Cytoplasmic Los1 (or los1Δ) results in activation of the general amino acid control pathway (Qiu et al. 2000; Karkusiewicz et al. 2012) and, in the case of DNA damage, results in damage-induced temporary G1 checkpoint arrest (Ghavidel et al. 2007). Thus, Los1 not only functions in tRNA nuclear export and tRNA quality control, but it also connects tRNA subcellular trafficking to cell physiology.

Msn5:

A second importin-β family member, exportin-5/Msn5, is implicated in the nuclear export of tRNA and other macromolecules. Yeast Msn5 has a well-defined role in nuclear export of particular phosphorylated transcription factors (reviewed in Hopper 1999). Vertebrate exportin-5 interacts with tRNA in a Ran-GTP dependent fashion; however, it is thought to play only a minor role in tRNA nuclear export (Bohnsack et al. 2002; Calado et al. 2002) and, instead, it primarily functions in microRNA nuclear export (Lund et al. 2004; reviewed in Katahira and Yoneda 2011). In contrast, in yeast and Drosophila, Msn5/exportin-5 also functions in tRNA nuclear export (Takano et al. 2005; Shibata et al. 2006; Murthi et al. 2010). In yeast, the role of Msn5 in tRNA nuclear export is evidenced by the demonstrations that msn5Δ cells accumulate nuclear pools of tRNA and that msn5Δ los1Δ cells have larger nuclear pools of tRNA than either mutant alone (Takano et al. 2005; Murthi et al. 2010). Despite defective tRNA nuclear export, msn5Δ cells do not accumulate intron-containing tRNAs (Murthi et al. 2010). Thus, Msn5 likely exports the category of tRNAs that are encoded by intronless genes and does not play an important role in delivering intron-containing pre-tRNAs to the cytoplasm; rather, as discussed below, Msn5 appears to specifically export tRNAs that have been spliced in the cytoplasm and imported from the cytoplasm to the nucleus back to the cytoplasm via the tRNA retrograde reexport process. Although Msn5 functions in tRNA nuclear export, Los1 and Msn5 cannot be the only nuclear exporters for tRNAs in yeast as los1Δ msn5Δ cells are viable (Takano et al. 2005).

tRNA retrograde nuclear import

At the time that the tRNA retrograde pathway was discovered, the view of tRNA movement was that it was unidirectional—nucleus to cytoplasm. The surprising discovery that, in yeast, tRNAs are spliced on the surface of mitochondria rather than in the nucleus as anticipated (Yoshihisa et al. 2003, 2007) provided an explanation as to why intron-containing tRNAs accumulate when cells possess mutations of the Ran pathway (RanGAP–rna1-1 or Ran-GEF–prp20) or the tRNA exportin, Los1 (los1-1) (Hopper et al. 1978, 1980; Kadowaki et al. 1993), as in these mutants the substrate and enzyme are largely in separate subcellular compartments. However, the discovery that pre-tRNAs are spliced in the cytoplasm raised a new conundrum as it failed to account for the phenotype of other mutations (cca1-1 or mes1-1) that accumulate uncharged mature tRNAs in the nucleus (Sarkar et al. 1999; Feng and Hopper 2002). It also failed to account for nuclear accumulation of mature tRNAs upon alteration of physiological conditions such as nutrient deprivation or upon addition of inhibitors of tRNA aminoacylation (Grosshans et al. 2000a; Shaheen and Hopper 2005). In these mutants/conditions where there are large nuclear pools of tRNA, tRNA splicing appears normal. Similar nuclear accumulation of spliced tRNAs occurs when cells are deprived of glucose or phosphate (Hurto et al. 2007; Whitney et al. 2007; Ohira and Suzuki 2011).

To explain the conundrum that tRNA splicing occurs in the cytoplasm, but spliced tRNAs can reside in the nucleus, it was suggested that tRNAs might travel in a retrograde fashion from the cytoplasm to the nucleus (Yoshihisa et al. 2003; Stanford et al. 2004) (Figure 3). Three lines of evidence subsequently supported this counterintuitive suggestion. First, in heterokaryons, foreign tRNA encoded by one nucleus can accumulate in the nucleus that does not encode the tRNA (Shaheen and Hopper 2005; Takano et al. 2005). Second, tRNA accumulates in nuclei of nutrient deprived haploid cells even when new tRNA transcription is inhibited by thiolutin (Takano et al. 2005; Whitney et al. 2007). Third, haploid cells bearing a mutation of MTR10, an importin-β family member that functions in nuclear import (Senger et al. 1998), fail to accumulate spliced tRNA in the nucleus when cells are nutrient deprived (Shaheen and Hopper 2005; Murthi et al. 2010).

tRNA retrograde import is conserved between vertebrates and yeast. HIV likely usurped this process as it provides one means by which HIV retrotranscribed complexes gain access to the nuclear interior in neuronal cells (Zaitseva et al. 2006). tRNA retrograde nuclear accumulation has also been demonstrated in vertebrate rat hepatoma cells after amino acid deprivation (Shaheen et al. 2007), in Chinese hamster ovary cells upon inhibition of protein synthesis by puromycin (Barhoom et al. 2011), and in heat-stressed human cells (Miyagawa et al. 2012). However, another group claims that this process is restricted to S. cerevisiae (Pierce and Mangroo 2011 and references therein).

The tRNA nuclear import process is not well understood and may occur via multiple mechanisms. One pathway appears to be Ran independent and mediated by the heat shock protein, Ssa2 (Takano et al. 2005; T. Yoshihisa, personal communication). Another pathway appears to be dependent upon Ran and Mtr10 (Shaheen and Hopper 2005). It is not clear whether Mtr10 functions directly in this pathway by acting as an importin for cytoplasmic tRNAs or, instead, whether it interacts indirectly by, for example, affecting a signaling factor. Conceivably, Mtr10 could tether tRNA in the nucleus or regulate such a tether; however, genetic data showing that mtr10Δ los1Δ or mtr10Δ msn5Δ do not accumulate nuclear tRNAs are more consistent with Mtr10 functioning in tRNA nuclear import rather than in anchoring tRNA inside the nucleus (Murthi et al. 2010). Further studies are required to delineate the mechanism(s) of tRNA nuclear import.

tRNA reexport to the cytoplasm

tRNAs imported into nuclei from the cytoplasm upon nutrient deprivation return to the cytoplasm upon refeeding by a process termed tRNA reexport (Whitney et al. 2007) (Figure 3). tRNAs can be aminoacylated in the nucleus by the nuclear pool of tRNA aminoacyl synthetases (Lund and Dahlberg 1998; Sarkar et al. 1999; Grosshans et al. 2000a; Azad et al. 2001). Yeast unable to aminoacylate tRNAs in the nucleus due to conditional mutations of genes encoding aminoacyl synthetases or CCA1, to drugs inhibiting tRNA aminoacylation or to amino acid deprivation accumulate in the nucleus tRNAs presumed to be derived from the cytoplasm (Sarkar et al. 1999; Grosshans et al. 2000a; Azad et al. 2001; Feng and Hopper 2002). The results support the notion that nuclear tRNA aminoacylation stimulates the reexport step.

It is poorly understood how appropriately processed and/or aminoacylated tRNAs are recognized by the tRNA reexport step. Since Los1 exports intron-containing tRNAs to the cytoplasm, but these pre-tRNAs cannot be aminoacylated (O’Farrell et al. 1978), Los1 is unlikely to monitor aminoacylation of the tRNAs that are imported into the nucleus. Genetic data indicate that Msn5 may function in the tRNA reexport process because even though there are nuclear pools of tRNAs in msn5Δ cells, there is no apparent accumulation of end-processed intron-containing tRNA in these cells. Thus, it has been proposed that the tRNAs (encoded by intron-containing genes) that accumulate in the nucleus of msn5Δ cells previously accessed the cytoplasm via Los1 where they were spliced; following cytoplasmic splicing the tRNAs are imported into the nucleus and they are retained there due to the lack of Msn5. The data has led to a working model that for those tRNAs encoded by intron-containing tRNAs, Msn5 likely functions in their reexport step. In contrast, Los1 likely functions both in the initial and reexport steps for this class of tRNAs. For tRNAs encoded by genes lacking introns, both Los1 and Msn5 may participate in both their initial tRNA export and reexport steps (Murthi et al. 2010) (Figure 3).

How Msn5 interacts with appropriate substrate tRNAs is unknown. Msn5 can bind uncharged tRNA in vitro (Shibata et al. 2006). The Msn5 vertebrate ortholog, exportin-5, exports pre-microRNAs from the nucleus to the cytoplasm (Lund et al. 2004; Katahira and Yoneda 2011; Lee et al. 2011) and there is a high-resolution 2.9-Å structure of exportin-5 in complex with Ran-GTP and a microRNA (Okada et al. 2009). Based upon the structural data, a prediction for the interaction of Msn5 and tRNA was proposed; however, the proposed structure and in vitro binding studies cannot explain how Msn5 might distinguish in vivo between mature and intron-containing tRNA species or between aminoacylated vs. uncharged mature tRNA (Okada et al. 2009; Lee et al. 2011). Perhaps, Msn5 is modified in vivo and the modification affects its substrate interaction or perhaps Msn5 specificity is aided by another protein in vivo. The biochemical studies challenge the working model for tRNA reexport and future studies are required to rectify in vivo vs. in vitro data to gain an understanding of the mechanism of this step of the tRNA retrograde process.

Regulation of the tRNA retrograde process