Abstract

Context

Antipsychotic drugs are limited in their ability to improve the overall outcome of schizophrenia. Adding psychosocial treatment may produce greater improvement in functional outcome than does medication treatment alone.

Objective

To evaluate the effectiveness of antipsychotic medication alone versus combined with psychosocial intervention on outcomes of early stage schizophrenia.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Randomized controlled trial of a clinical sample of 1268 patients with early stage schizophrenia, conducted at 10 clinical sites in China from 2005–2007.

Intervention

Patients were randomly assigned to antipsychotic medication treatment only or antipsychotic medication plus 12 months of psychosocial intervention, consisting of psycho-education, family intervention, skills training and cognitive-behavioral therapy, administered over 48 group sessions.

Main Outcome Measures

The rate of treatment discontinuation or change due to any cause, relapse or remission, and assessments of insight, treatment adherence, quality of life and social functioning.

Results

The rates of treatment discontinuation or change due to any cause were 32.8% in the combined treatment group and 46.8% in the medication alone group. Comparisons with medication treatment alone showed lower risk for any cause discontinuation with combined treatment (hazard ratios [HR], 0.62; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.52–0.74; p<0.001); and lower risk for relapse with combined treatment (HR, 0.57; 95%CI, 0.44–0.74; p<0.001). The combined treatment group exhibited greater improvement in insight (p<0.001), social functioning (p=0.002), activities of daily living (p<0.001), and in 4 domains of quality of life as measured by Medical Outcome Study Short-Form 36-item questionnaire (all p-values<0.02). Furthermore, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving combined treatment obtained employment or accessed education (p=0.001).

Conclusions

Compared to those receiving medications only, early stage schizophrenia patients receiving medications and psychosocial intervention had a lower rate of treatment discontinuation or change, lower risk of relapse, and improved insight, quality of life and social functioning.

Introduction

Antipsychotic drugs have been shown to be effective against psychotic symptoms, and they are now the mainstay of therapy for patients with schizophrenia.1, 2 However, long-term therapy with antipsychotics is associated with a range of side effects, poor adherence and high rates of medication discontinuation.2–4 Most patients, even those with a good response to medication, continue to suffer from disabling residual symptoms, impaired social and occupational functioning, and a high risk of relapse. Certain psychosocial treatments have been shown to have beneficial effects on clinical and functional outcomes.5–9 For instance, family intervention reduces relapse rate5; cognitive behavioral therapy reduces positive symptoms5, 8; social skills training improves social competence7. The combination of pharmacotherapy and psychosocial intervention has been recommended for treatment of schizophrenia by practice guidelines for psychiatrists.10 Psychosocial interventions can be best implemented when acute symptoms have been reduced and the patient can be successfully engaged in treatment. The goals of intervention are to reduce stress on the patient, provide support to minimize the likelihood of relapse, enhance the patient’s adaptation to life in the community, and facilitate continued reduction in symptoms and consolidation of remission.10 However, the effectiveness of psychosocial intervention approaches has been considered separately. Each intervention has been directed towards one of the components of the problem: the patient’s symptoms, relapse, or social skills. Few comprehensive psychosocial intervention packages have been developed that can address several problems simultaneously in schizophrenia.

Early illness course is an important predictive factor for the long-term outcome; intervention during this critical period is considered important.11 As with the published literature on chronic schizophrenia treatment, studies of first episode and early schizophrenia samples have shown that they benefit from medication management integrated with a variety of psychosocial treatments. For example, the OPUS trial used an intensive early intervention approach combining assertive community treatment, family psycho-education, and social skills training, with positive effects on hospitalization rates, living independence, symptom severity, and family burden.12, 13 Integrated treatment with medication, skills training, and cognitive behavioral therapy has been another approach used, with positive effects on symptom severity.14 Finally, medication has also been integrated with cognitive behavioral therapy, family support, and vocational services, with positive effects on hospital readmission, functioning, and medication adherence.15, 16

In this article, we report on a study named the Antipsychotic Combination with Psychosocial Intervention on the Outcome of Schizophrenia (ACPIOS, funded by Ministry of Science and Technology of China), which was a 1-year randomized clinical trial that tested the effect of medication combined with a group psychosocial intervention versus medication treatment alone on outcomes of early stage schizophrenia patients.17 The outcomes measured included the rate of treatment discontinuation or change due to any cause, relapse or remission, and assessments of insight, treatment adherence, quality of life and social functioning. We hypothesized that combined medication and comprehensive psychosocial treatment would result in lower rates of treatment discontinuation or relapse than would medication treatment alone, which would reflect variations in efficacy, insight and compliance, quality of life, social outcome, and adverse effects.

Methods

Participants

The study was conducted between January 2005 and October 2007 at 10 clinical sites in China (6 university clinics and 4 province mental health agencies). All patients were enrolled from outpatient psychiatric clinics and under maintenance treatment. Eligible patients were 16 to 50 years of age who had to meet following enrollment criteria: 1) DSM-IV diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder within the past five years, as determined by the Structured Clinical Interview of the Diagnosis (SCID) administered by study investigators or trained staff; 2) living with family members who could be involved in the patient’s care; 3) PANSS (Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale)18 total scores were ≤60; 4) on maintenance treatment with one of the following 7 oral antipsychotics: chlorpromazine, sulpiride, clozapine, risperidone, olanzapine, quetiapine or aripiprazole. We selected these 7 antipsychotics because over 90% of schizophrenia patients in China were prescribed one of these antipsychotics.19 Patients were excluded if they were: 1) prescribed two or more antipsychotics or long-acting injectable antipsychotics; 2) participating in other therapy programs; 3) pregnant or breastfeeding; or 4) diagnosed with a serious and unstable medical condition. This study was approved by the institutional review board at each site, and written informed consent was obtained from the patients or their legal guardians.

Procedure

Following baseline assessment, participants were randomly assigned to receive combined medication and psychosocial treatment versus medication treatment alone and followed for up to 12 months or until medication treatment was discontinued for any reason. Group assignment was based on a 1:1 randomization scheme balanced by sites and medication prescribed. All medication visits and interventions took place in the outpatient psychiatric clinics in these participating institutes. Both study groups came to medication management visits once a month and the therapy was given on the same day for the combined treatment group. The family members had to bring the patient to each appointment, regardless of treatment group. All patients and their family members from both study groups came to the clinic once a month and received the same compensation for participating in the study. No transportation, outreach, or other logistic supports were provided by this study. In both groups, patients and family members could ask medication or treatment-related questions of the treating clinicians during their 30-minute visit as standard of outpatient care for medication management. To better keep the assessors and clinicians blind, the psychotherapy rooms, clinicians’ offices, and assessors’ offices were isolated from each other, patients and family members were reminded at enrollment and follow up visits not to discuss treatment assignment with their clinicians and assessors, and investigators and staff were restricted in the discussion of patients within research teams. Further detail about the study rationale, design, and methods have been described previously.17

Interventions

Pharmacotherapy

Because all patients were on maintenance treatment, we encouraged clinicians to try to keep patients on the same medication for at least 3–6 months in order to gauge treatment efficacy and minimize early discontinuation. However, medications could be changed at any time during the course of the study if the change was clinically warranted. If a patient’s medication was stopped or switched, patients were classified as discontinued and terminated from the study. No further assessments were required for these patients. Mood stabilizers, benzodiazepines, antidepressants, and anticholinergic medications were permitted, and daily doses of all medications were recorded throughout the study.

Psychosocial intervention

Patients assigned to the combined treatment group received medication treatment and were enrolled in a psychosocial intervention program. The psychosocial intervention strictly followed a detailed treatment manual designed by the principal investigators and included four evidence-based practices: psycho-education, family intervention, skills training and cognitive-behavioral therapy.20 Psychosocial intervention participants were seen 12 times (once per month for 12 months), receiving each of the four group treatments on the same day, for a total of 48 one-hour sessions (see Table 1 for topics covered). A lunch break and two half-hour breaks were provided to maintain engagement and attention. We designed this comprehensive psychosocial intervention to be delivered on the same day once a month mainly due to the care structure in China, the potential time and cost burden to patients and their family members, as well as feasibility of being adopted by other care settings. In China, the vast majority of schizophrenia patients live with their family members because of limited social welfare for severe mentally ill patients. Many of these family members also work full time so it is not convenient for them to take time off every week and bring the patients for therapy. In addition, all of our psychosocial interventions were group based, so having many patients and their family members come in once a week at the same time was not feasible and practical. Weekly intervention visits also would have increased the costs of transportation and therapist time, making the overall cost of the psychosocial intervention higher. Finally, psychosocial interventions have become more popular in recent decades in China, but the number of well-trained therapists remains limited in many Chinese psychiatric settings. More frequent therapy sessions could not only be difficult for patients and family members, but also hard to adopt by many psychiatric settings.

Table 1.

Content of monthly psychosocial treatment sessions

| Psycho-education Topics | Family Intervention Topics | Skills Training Topics | Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Topics | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month 1 | Introduction into the program Discussion of goals and questions | Introduction into the program Discussion of goals and questions | Medication management(1)Identifying benefits of antipsychotic medication | Develop the therapeutic alliance |

| Month 2 | What is schizophrenia? | The role of the family in schizophrenia | Medication management(2) self- administration and evaluation of medication | Using the ‘ABC’ Model to find connections between Activating Events, Beliefs, and Consequences. |

| Month 3 | Causal and triggering factors | Relatives shared the experiences of caring for patients | Medication management(3) side effects of antipsychotic medication | Intervening with Auditory Hallucinations (Voices) |

| Month 4 | A description of the various symptoms | Coping Strategies. Identify, describe, clarify, and teach coping strategies are used by families. | Symptom management (1)identifying warning signs of relapse | Intervening with Auditory Hallucinations (Voices) |

| Month 5 | Patients’ concepts of illness and the Vulnerability-stress-coping-model | Coping Strategies. Identify, describe, clarify, and teach coping strategies are used by families. | Symptom management (2) developing a relapse prevention plan | Intervening with Delusions (1) |

| Month 6 | Course and outcome | Help families with problem-solving | Verbal and nonverbal communication (1) | Intervening with Delusions (2) |

| Month 7 | Treatment recommendations concerning pharmacotherapy | Help families with problem-solving. | Verbal and nonverbal communication (2) | Intervening with anxiety, depression, and self-esteem |

| Month 8 | Risks associated with treatment withdrawal | Family communication | Learn and practice problem solving skills | Intervening with anxiety, depression, and self-esteem |

| Month 9 | Early detection of relapse | Family communication | Learn and practice problem solving skills | Relapse prevention |

| Month 10 | Pregnancy and genetic counseling | Behavior management | Job-finding skills | Relapse prevention |

| Month 11 | Talking over of open questions | Behavior management | Independent living skills | Enhancing medication adherence |

| Month 12 | Final session – review of content | Final session – review of content | Independent living skills | Enhancing medication adherence |

Psycho-education included teaching patients and caregivers about the symptoms, treatment and course of mental illness, and afforded patients and family members the opportunity to ask questions about psychiatric disorders and treatment options. This group provided a forum in which to discuss concerns and obtain support from the group in order to reduce the stigma of mental illness. The purpose of psycho-education was to increase patients’ and caregivers’ knowledge and understanding of the illness and treatment.21–23

Family intervention included developing collaboration with the family; socializing about non-illness-related topics; monthly updates on each family’s situation; enhancing family communication; teaching patients and their families to cope with stressful situations and the illness; and teaching patients and their families to detect signs of relapse and intervene in crises.21, 24, 25

Skills training included modules on medication management and symptom self-management, dealing with stigma, social problem solving and independent living skills. The training included teaching complex interpersonal skills by breaking down the targeted behaviors into component steps and systematically using modeling, behavioral rehearsal, positive and corrective feedback, and in-vivo practice to shape the acquisition and generalization of skills.7, 26–28

Cognitive-behavioral therapy involved treatment of auditory hallucinations and delusions, associated symptoms and problems (i.e. anxiety, depression, and self-esteem), relapse prevention, and enhancing medication adherence. Treatment included an assessment and engagement phase, education, and building a therapeutic alliance; functional analysis of key symptoms, leading to formulation of a problem list; development of a normalizing rationale for the patients’ psychotic experiences; exploration and enhancement of coping strategies; and addressed concomitant affective symptoms using relaxation training.29, 30

Therapists who had at least two years of clinical experience after earning an M.D. or Ph.D. or at least five years’ experience after earning a masters degree in clinical psychology delivered the psychosocial intervention. They attended training workshops until they had mastered all treatment procedures. Treatment fidelity was maintained by having the therapists’ supervisors assess adherence to the treatment manual after each monthly session by reviewing videotapes.

Outcome assessments

All subjects were assessed monthly by the study psychiatrists and every 2 weeks by a research assistant who had instructions to contact the psychiatrist if medication discontinuation, relapse or other problems were suspected. The psychiatrists assessed patients mainly for medication management purposes, evaluating for clinical response to medications, medication compliance, and major side effects. The research assistants assessed patients, patients’ caregivers, and other sources every two weeks by phone for any hospitalizations, relapses, or other causes of treatment discontinuation. The research assistants also administered the symptom and functioning rating scales at scheduled intervals. The primary measure was rate of treatment discontinuation or change and time to treatment discontinuation. Once a patient discontinued the study, no further assessments were completed. Our criteria for treatment discontinuation or change were somewhat broader than those of the CATIE study2 and included: 1) clinical relapse/hospital admission; 2) lost to follow-up or patient’s refusal; 3) noncompliance, defined as taking less than 70% of prescribed medications, detected either by the treating psychiatrist or research assistants during follow-up assessments; 4) changing or stopping of initial antipsychotic by doctor or patient request and 5) intolerability, defined as severe side effects that caused the treating psychiatrists to stop the medications.

Clinical relapse was defined by any one of the following31: (1) psychiatric hospitalization; (2) an increase in the level of psychiatric care (e.g., from clinic visits to day treatment) and a 25% or more increase in the PANSS total score (or 10 points if the initial score was 40 or less); (3) a Clinical Global Impressions (CGI) Scale score of “much worse” or “very much worse”32; (4) deliberate self-injury; (5) emergence of clinically significant suicidal or homicidal ideation; or (6) violent behavior resulting in significant injury to another person or significant property damage.

Secondary outcomes further assessed treatment effectiveness by measuring symptom severity (PANSS), insight (Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire, ITAQ)33, treatment adherence (appointment compliance), quality of life (Medical Outcome Study Short-Form 36-item questionnaire, SF-36)34, 35, and social function on the Global Assessment Scale (GAS)36, 37 and the Activities of Daily Living Scale (ADL)38, 39. The SF-36 consists of 8 domains that assess the following: bodily pain (BP), general health (GH), general mental health (MH), physical functioning (PF), role-emotional (RE), role-physical (RP), social functioning (SF), and vitality (VT). GAS is a single-item rating scale for evaluation of overall patient functioning.36, 37 The 14-item independent activity of daily living (ADL) scale assesses a person's ability perform basic (i.e. dressing, walking and bathing) and instrumental (i.e. using a telephone, doing laundry, and handling finances) activities of daily living.38, 39 This scale has been widely used and has demonstrated validity in studies of medically ill and dementia populations in China.40, 41 The rate of obtained work or education during the 12 months was also used to assess role functioning and community integration. The physical examination and the effect of antipsychotic treatment on weight gain were recorded regularly. The Treatment Emergent Symptom Scale (TESS)42 was used for monitoring adverse effects.

All interviewers trained and received reassessments of inter-rater reliability based on videotaped demonstration interviews. Agreement among the raters was high for the PANSS, ITAQ, GAS and ADL (Pearson’s correlation coefficient=0.78 to 0.86) at baseline and every 6 months.

Statistical analysis

Analyses were performed according to the intention-to-treat principle. Randomized patients who had at least one assessment during treatment made up the intention-to-treat population. The sample sizes were selected to make possible the detection of a 15 percent difference in discontinuation rates after one year with 85 percent power and a two-tailed alpha level of significance of 0.05.

Baseline characteristics were compared between the two groups by analysis of variance, Pearson’s chi-square test, or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate. We used Kaplan-Meier survival curves to estimate the time to discontinuation of treatment in the sample. Factors associated with treatment discontinuation were determined by multivariate analysis using a Cox proportional hazards model with stepwise reduction and a log-rank test with control for site.43 Data were presented as hazard ratios (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI). Time course and treatment differences for change in the PANSS, ITAQ, SF-36 domain scores, GAS, and ADL were analyzed using Mixed-Effects Model for Repeated-Measures analyses (MMRM) with effects of treatment, time, and treatment by time interaction with unrestricted covariance of baseline scores.44 Time was classified into months (baseline, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months). Other categorical outcomes (including data regarding adverse events) were compared with the use of Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test. All statistical tests were two-tailed.

Results

Disposition and baseline characteristics of patients

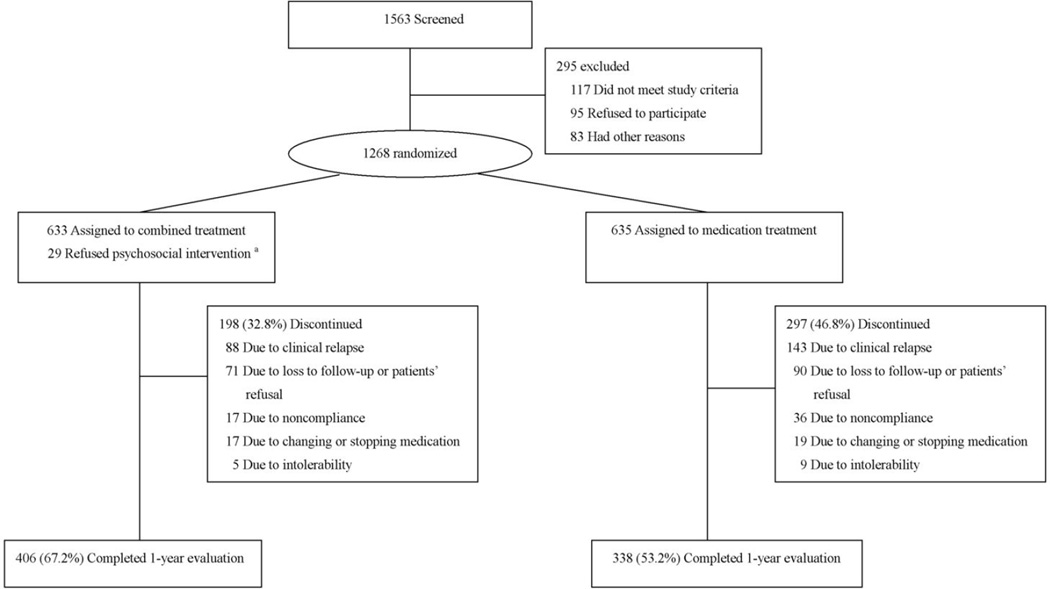

A total of 1563 potentially eligible subjects were screened. Of these subjects, 1268 patients completed the baseline assessment and underwent randomization; 633 were assigned to receive antipsychotics combined with psychosocial intervention, and 635 to receive antipsychotics alone. Overall, 744 (60.0%) patients completed the one-year follow-up: 406 (67.2%) in the combined intervention group and 338 (53.2 %) in the antipsychotic alone group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study flowchart. The figure showed the numbers of patients screened for potential inclusion, the reasons for exclusions from randomization, and primary outcome in one-year followed-up. 29 patients refused psychosocial intervention were excluded from the final analysis because their follow-up was not carried out.

There were no significant differences among study groups with respect to baseline demographic and clinical characteristics. The mean age was 26 years; 55 percent of the patients were male and most patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia (84.6%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Randomized Patients a

| Characteristics | Combined treatment (n=633) |

Medication treatment (n=635) |

|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||

| Age, y | 26.1(25.5–26.8) | 26.4(25.7–27.0) |

| Male No.(%) | 344 (54.3) | 354 (55.7) |

| Marital status No.(%) | ||

| Married | 167 (26.4) | 173 (27.2) |

| Previously married b | 39 (6.2) | 28 (4.4) |

| Never married | 427 (67.5) | 434 (68.3) |

| Education, y | 12.2(11.9–12.5) | 12.0(11.7–12.3) |

| Clinical | ||

| DSM-IV diagnosis No.(%) | ||

| Schizophrenia | 535(84.5) | 538(84.7) |

| Schizophreniform disorder | 98(15.5) | 97(15.3) |

| PANSS total score | 44.7(43.7–45.7) | 45.6(44.5–46.7) |

| CGI severity score | 2.5(2.4–2.6) | 2.6(2.5–2.7) |

| Age at onset, y | 23.8(23.2–24.4) | 24.2(23.4–24.6) |

| Duration of schizophrenia, mo | 24.6(23.0–26.3) | 23.3(21.7–24.9) |

| Daily dose of antipsychotic agents, mg/total No. | ||

| Chlorpromazine | 332.1(305.0–359.2)/95 | 344.9(319.0–370.8)/94 |

| Sulpiride | 720.3(673.2–767.4)/98 | 732.8(683.2–782.4)/97 |

| Clozapine | 267.0(244.0–290.0)/99 | 269.9(246.7–293.1)/99 |

| Risperidone | 3.5(3.3–3.7)/111 | 3.7(3.4–3.9)/112 |

| Olanzpine | 11.9(10.9–12.9)/79 | 12.4(11.1–13.7)/80 |

| Quetiapine | 538.2(490.2–586.2)/80 | 524.5(467.3–581.7)/81 |

| Aripiprazole | 18.5(16.9–20.1)/71 | 18.5(16.6–20.4)/72 |

Abbreviation: PANSS, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; CGI, Clinical Global Impressions; DSM-IV, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fourth Edition

Data are presented as mean (95% confidence interval) unless otherwise indicated. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

This category includes patients who were widowed, divorced, or separated.

Among the 406 combined treatment participants who completed the study, the mean number of sessions attended was 44.2±4.4 (92.1%), whereas among the 198 combined treatment participants who discontinued or changed treatment, the mean number was 18.1±4.9 (37.7%).

Rates of Treatment Discontinuation

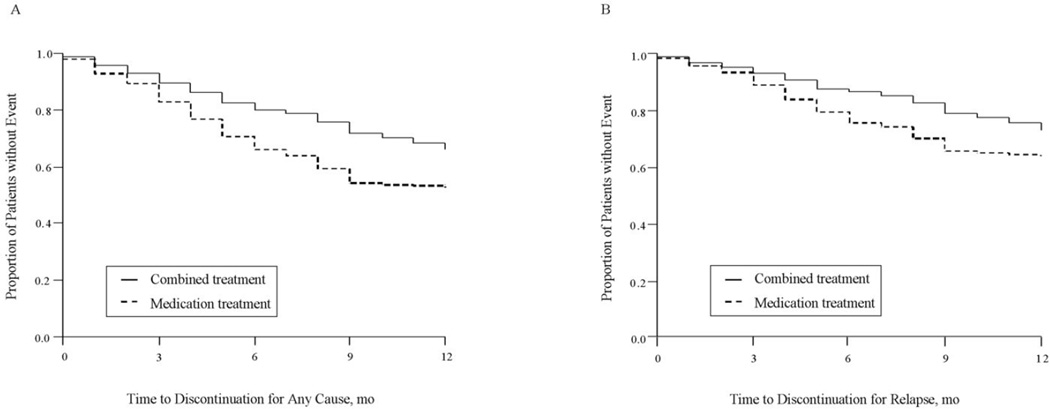

Forty percent of patients in the final analysis (495 of 1239) discontinued their treatment during the 12-month treatment period (32.8 percent of patients in the combined group and 46.8 percent of patients in the medication alone group). The difference between groups in treatment discontinuation for any cause was significant (HR=0.62; 95% CI, 0.52 to 0.74; p<0.001, Table 3 and Figure 2).

Table 3.

Outcome measures of effectiveness in patients with combined treatment or medication treatment

| Outcome | Combined treatment (n=604) |

Medication treatment (n=635) |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discontinuation of treatment for any cause No. (%) | 198(32.8%) | 297 (46.8%) | |

| Cox–model treatment comparisons (HR[95%CI]) | 0.62(0.52—0.74) | <0.001 | |

| Discontinuation of treatment for any causea No. (%) | 176(29.1%) | 269(42.4%) | |

| Cox–model treatment comparisons (HR[95%CI]) | 0.57(0.46—0.70) | <0.001 | |

| Discontinuation of treatment due to clinical relapse No. (%) | 88(14.6%) | 143(22.5%) | |

| Cox–model treatment comparisons (HR[95%CI]) | 0.57(0.44—0.74) | <0.001 | |

| Discontinuation of treatment for lost to follow-up or patient’s refusal No. (%) | 71(11.8%) | 90(14.2%) | |

| Cox–model treatment comparisons (HR[95%CI]) | 0.74(0.54—1.01) | 0.054 | |

| Discontinuation of treatment for noncompliance No. (%) | 17(2.8%) | 36(5.7%) | |

| Cox–model treatment comparisons (HR[95%CI]) | 0.45(0.25—0.79) | 0.006 | |

| Discontinuation of treatment for changing or stopping medication No. (%) | 17(2.8%) | 19(3.0%) | |

| Cox–model treatment comparisons (HR[95%CI]) | 0.84(0.44—1.62) | 0.60 | |

| Discontinuation of treatment due to intolerability No. (%) | 5(0.8%) | 9(1.4%) | |

| Cox–model treatment comparisons (HR[95%CI]) | 0.66(0.22—1.99) | 0.46 | |

| Discontinuation of treatment due to readmission No. (%) | 39(6.5%) | 71(11.2%) | |

| Cox–model treatment comparisons (HR[95%CI]) | 0.50(0.34—0.74) | 0.007 | |

Abbreviation: HR, hazard ratios; CI, confidence interval;

excluding those discontinued due to change of medication or intolerability

Figure 2.

(A)Time to treatment discontinuation because of any cause. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed a significant difference between medication treatment group and combined medication and psychosocial intervention group (Log-rank test: χ2=28.846, df=1, p<0.001). (B)Time to treatment discontinuation because of relapse. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis showed a significant difference between medication treatment group and combined medication and psychosocial intervention group (Log-rank test: χ2=18.115, df=1, p<0.001).

14.6 percent of patients in the combined group and 22.5 percent of patients in the medication alone group had relapsed. The risk of relapse was lower among patients assigned to combined treatment (HR=0.57; 95% CI, 0.44 to 0.74; p<0.001, Table 3 and Figure 2).

2.8 percent of patients in the combined group and 5.7 percent of patients in the medication group were noncompliant; rates of these events were lower among patients assigned to combined treatment (HR=0.45; 95% CI, 0.25 to 0.79; p=0.006).

6.5 percent of patients in the combined group and 11.2 percent of patients in the medication group had readmission. The risk of readmission was substantially lower among patients assigned to combined treatment (HR=0.50; 95% CI, 0.34 to 0.74; p=0.007).

We also analyzed all causes of discontinuation for poor outcomes only by excluding intolerance and changing medication (as these events do not always indicate poor outcomes). The results showed that 29.1% in the combined treatment group and 42.4% in medication alone group discontinued treatment due to poor outcomes; this difference was statistically significant (HR=0.57; 95% CI, 0.46 to 0.70; p<0.001).

Changes in Scale Scores

The results of the MMRM analyses of change in psychopathology and daily functioning assessments between the two treatment groups are presented in Table 4. Although the analyses used data from the baseline, 3, 6, 9, and 12 month assessments, we present only the baseline, 6 and 12 month mean scores in the table. Analyses revealed a significant improvement in total PANSS and ITAQ scores over time in both groups (both Fs>89.673; both p-values<0.001), however, the change in total ITAQ scores was greater in the combined group than in the medication alone group (F=25.945, p<0.001). Improvements in GA S (F=4.332, p=0.002) and ADL scores (F=12.699, p<0.001) were also greater over time for the combined group than for the medication only group. Compared with those in the medication alone group, those receiving combined treatment showed significantly greater improvement on four domains of the SF-36 (Role-Physical, General Health, Vitality, and Role-Emotional; all Fs>3.985; all p-values<0.02).

Table 4.

Mixed-Effects Model for Repeated Measures (MMRM) analysis on clinical and functioning outcomes in patients with combined treatment or medication treatment a

| Assessment | Mean (95% CI) | Analyses b | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| baseline | 6 months | 12 months | Group-by-Time Interaction Effect |

|||||

| CT (n=580) |

MT (n=604) |

CT (n=512) |

MT (n=472) |

CT (n=406) |

MT (n=338) |

F | p | |

| PANSS | 44.6(43.5–45.7) | 45.3(44.2–46.5) | 37.3(36.5–38.1) | 38.8(38.0–39.7) | 34.7(34.2–35.2) | 36.4(35.7–37.1) | 0.406 | 0.81 |

| ITAQ | 12.8(12.4–13.2) | 12.7(12.2–13.1) | 17.9(17.5–18.3) | 14.2(13.7–14.8) | 19.5(19.1–19.8) | 15.9(15.4–16.5) | 25.945 | <0.001 |

| GAS | 74.1(73.2–75.1) | 74.2(73.2–75.1) | 79.8(78.9–80.6) | 77.9(77.0–78.8) | 82.9(82.0–83.7) | 80.8(79.9–81.8) | 4.332 | 0.002 |

| ADL | 17.2(17.0–17.4) | 17.2(17.0–17.4) | 15.7(15.5–15.8) | 16.6(16.5–16.8) | 15.4(15.3–15.5) | 16.4(16.3–16.5) | 12.699 | <0.001 |

| SF-36 | ||||||||

| Physical Functioning | 90.8(89.7–91.8) | 90.6(89.5–91.6) | 92.9(91.8–93.9) | 92.3(91.3–93.2) | 95.2(94.3–96.1) | 94.9(94.1–95.7) | 0.121 | 0.87 |

| Role-Physical | 54.1(50.8–57.3) | 57.3(54.1–60.6) | 67.1(63.9–70.2) | 65.8(62.5–69.2) | 78.1(74.9–81.3) | 73.4(69.6–77.1) | 5.129 | 0.006 |

| Bodily Pain | 77.2(74.7–79.8) | 78.8(76.4–81.2) | 83.0(80.5–85.6) | 84.4(81.9–86.9) | 89.9(87.9–91.9) | 89.3(87.0–91.6) | 2.795 | 0.06 |

| General Health | 61.7(60.3–63.2) | 63.5(62.1–65.0) | 67.5(66.1–69.0) | 65.8(64.2–67.4) | 71.3(69.8–72.8) | 67.9(66.2–69.7) | 11.094 | <0.001 |

| Vitality | 59.5(58.0–61.1) | 58.0(56.4–59.5) | 65.6(64.1–67.1) | 60.1(58.4–61.9) | 66.7(65.0–68.4) | 60.5(58.4–62.7) | 5.327 | 0.005 |

| Social Functioning | 74.5(72.5–76.5) | 74.5(72.6–76.4) | 82.2(80.4–84.0) | 81.2(79.3–83.0) | 86.5(84.5–88.4) | 85.0(82.9–87.1) | 1.003 | 0.37 |

| Role-Emotional | 57.5(54.2–60.7) | 56.5(53.1–59.8) | 68.0(64.7–71.2) | 63.8(60.2–67.4) | 80.1(76.9–83.2) | 72.1(68.1–76.1) | 3.985 | 0.02 |

| Mental Health | 65.2(63.8–66.6) | 64.5(63.2–65.8) | 69.1(67.7–70.6) | 67.2(65.8–68.6) | 71.9(70.4–73.5) | 70.2(68.5–71.8) | 1.573 | 0.21 |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval; PANSS, the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; ITAQ, Insight and Treatment Attitudes Questionnaire; SF-36, Medical Outcome Study Short-Form 36-item questionnaire; GAS, Global Assessment Scale; ADL, the Activities of Daily Living Scale; CT, combined treatment; MT, medication treatment.

Analyses are based on Mixed-Effects Model for Repeated Measures (MMRM) in unstructured variance matrix. Baseline value was included as covariates.

Analyses used data from the baseline, 3, 6, 9, and 12 month assessments, only the baseline, 6 and 12 month results were presented in the table.

In addition, a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving combined treatment obtained employment or accessed education (combined treatment group 30.1% vs. medication alone group 22.2%; χ2=10.094, p=0.001).

Adverse Events

There were no significant differences in the frequency and types of adverse events reported between two groups (all p-values>0.05, Table 5). The treatment group effect at the end of treatment (determined by analysis of variance with the baseline value as a covariate) was not significant for the dose of antipsychotic medication (p>0.05). There were no differences between two groups in the rates or types of medications added during the study (all p-values>0.05, Table 5).

Table 5.

Safety outcomes of patients with combined treatment or medication treatment in one-year follow-up

| Safety measure | No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Combined treatment (n=633) |

Medication treatment (n=635) |

χ2 Testa | p Value |

|

| Adverse events | ||||

| Extrapyramidal symptoms | 135(21.3) | 142(22.4) | 0.199 | 0.66 |

| Hypersomnia, sleepiness | 202(31.9) | 216(34.0) | 0.635 | 0.43 |

| Dry month, constipation, Urinary hestitancy | 277(43.8) | 301(47.4) | 1.695 | 0.19 |

| Menstrual irregularitiesb | 46(15.9) | 47(16.7) | 0.068 | 0.79 |

| Dizziness | 76(12.0) | 82(12.9) | 0.239 | 0.63 |

| Insomnia | 35(5.5) | 50(7.9) | 2.787 | 0.10 |

| Weight gain>7% (from baseline to last observation) | 149 (23.5) | 132 (20.8) | 1.391 | 0.24 |

| Medication added | ||||

| Lithium/anticonvulsants | 15(2.4) | 20(3.1) | 0.718 | 0.40 |

| Antidepressants | 49(7.7) | 58(9.1) | 0.796 | 0.37 |

| Anxiolytics | 35(5.5) | 40(6.3) | 0.338 | 0.56 |

| Anticholinergic agents | 161(25.4) | 176(27.7) | 0.846 | 0.36 |

| β-Adrenergic receptor antagonists | 41(6.5) | 54(8.5) | 1.879 | 0.20 |

| Other drugs | 41(6.5) | 40(6.3) | 0.017 | 0.91 |

χ2 for categorical variables

Percentages are based on the number of female patients: 289 in combined treatment group and 281 in medication treatment group.

Comment

Treatment for schizophrenia should focus on improving real-world effectiveness outcomes, including functional capacity and health-related quality of life. This study was designed to provide information on psychosocial intervention on outcome of early stage schizophrenia, in particular on functional outcome in real-world practice. We found that combined treatment improved medication adherence, risk of relapse and hospital admission, insight, quality of life, and social/occupational functioning.

Treatment discontinuation in patients with schizophrenia is strikingly common; the CATIE study reported that 74 percent of patients discontinued their medications in the 18-month study2 and the EUFEST study reported that an average of 42 percent discontinued their medications at 1 year follow-up.45 Discontinuing medication is associated with symptom exacerbation, relapse, increased hospitalization, and poor long-term course of illness.46,47 Our study showed a lower rate of medication discontinuation compared to the above studies. One reason could be that our psychosocial intervention reduced the risk of treatment discontinuation and improved insight and medication compliance; another reason could be that family members are more involved patients’ care in China, similar to other Asian or developing countries. This kind of family involvement and support could further reduce medication discontinuation rates and subsequently improve outcomes. Another potential reason for better outcomes in the combined treatment group was that medication and psychosocial treatments occurred on the same day each month for patients, allowing the psychiatrists and other care providers reinforce the importance of participation in all components of treatment.

Prevention of relapse is the cornerstone to improving all areas of long-term outcome and achieving long-term improvements in quality of life and level of functioning. The risks of relapse and hospital admission were significantly lower in the combined treatment group than in the medication alone group in this study.

Improvements in quality of life represent evidence of a good treatment outcome for patients with schizophrenia. After 12 months of treatment, more improvements of quality of life were seen in patients who received combined treatment. Better quality of life outcomes in the combined treatment group were demonstrated not only in mental health domains, but also in physical health domains, suggesting that combined treatment may afford the best combination of effectiveness and improved quality of life.

Social outcomes reflect how patients live, function in society and perform their various roles (e.g., having a job, going to school, or having friends). Our study showed that a significantly higher proportion of patients receiving combined treatment obtained employment or accessed education. Thus, the findings support the results from previous studies that patients with schizophrenia receiving combined treatment had better outcomes.12, 13, 50–53 In particular, integrating a comprehensive therapy with medication treatment in early stage schizophrenia patients before to the disease becomes chronic and disabling could improve long-term outcomes.

Psycho-education, family intervention, skills training and CBT have proven to be effective in treating people with schizophrenia.5,7–10, 30, 53 To our knowledge, this is one of a very few studies to take this integrated intervention approach and address outcome as a whole, with the goal of improving overall outcome in early stage schizophrenia patients. Our once-monthly comprehensive psychosocial intervention approach is different from the common therapy model used in the US and other western countries. Though this study cannot indicate whether this intensive therapy model can be applied in other countries, it did provide evidence that the model was practical and showed better efficacy compared to medications alone in improving overall outcome for early stage patients with schizophrenia. This result may be particularly informative to Asian, African, or Latin American countries, where schizophrenia patients tend to live with their families and family members are often involved in patient care.

This study has several limitations. First, this was a 12-month trial; a longer-term randomized clinical trial would contribute substantially to understanding the longer-term effects of psychosocial intervention on outcomes. Second, although measures were taken to maintain the blinding, it is not known how effective the blinding was. However, several outcome measures were not vulnerable to bias, such as rehospitalization, lost to follow-up, and treatment non-compliance. Third, although the combined psychosocial intervention showed better overall efficacy than medications alone, we do not know whether the effects of the combined intervention were equally attributable to all of the modules.

Conclusions

In summary, our study suggested that combined treatment in early stage schizophrenia patients reduced rate of treatment discontinuation and risk of relapse. It also improved insight, adherence to treatment, quality of life, and social function. Integrating comprehensive therapy with medication treatment in the early stage of schizophrenia is critically important and should be recommended as the standard of care.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This research was supported by National Key Technologies R&D Program in the 10th 5-year-plan of China (grant No. 2004BA720A22); by National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant No.30630062); and by National Basic Research Program of China (grant No.2010CB529601).

Role of the Sponsor: The funding organizations played no role in the design, conduct, analysis, or interpretation of the research or in any aspect of preparation or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr Zhao had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Guo, Zhai, Liu, Wang, Jin, and Zhao.

Acquisition of data: Guo, Zhai, Liu, Fang, Wang, Hu, Sun, Lv, Lu, Ma, He, Xie, Wu, Xue, Chen, and Zhao.

Analysis and interpretation of data: Guo, Zhai, Liu, Fang, Wu, Xue, Chen, Twamley, Jin, and Zhao

Drafting of the manuscript: Guo, Zhai, Jin, Twamley, and Zhao.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Guo, Zhai, Liu, Fang, Wang, Hu, Sun, Lv, Lu, Ma, He, Xie, Wu, Xue, Chen, Jin, Twamley, and Zhao.

Statistical analysis: Guo, Zhai, and Zhao.

Obtained funding: Zhao.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Guo, Zhai, Liu, Fang, Wang, Wu, Xue, and Chen.

Study supervision: Guo, Zhai, Zhao, Liu, Fang, and Wu.

Financial Disclosures: None reported.

Additional Contributions: The following individuals collected data at participating sites: Yan Yu, MD, Zhanchou Zhang, PhD, Mental Health Institute of the Second Xiangya Hospital Central South University; Jianchu Zhou, MD, Jie Ning, MD, Juhong Qiu, PhD, Chongqing Mental Health Centre; Qi Chen, MD, Ying Wang, MD, Qing Huang, PhD, Beijing Anding Hospital Affiliated to Capital Medical University; Fajin Gong, MD, Fang Yu, MD, Shuiquan Xu, MD, Psychiatric Hospital of Jiangxi Province; Hong Deng, MD, Qinglan Tao, MD, Yun Wan, PhD, Mental Health Center of West China Hospital, Sichuan University; Ruiling Zhang, MD, Yingli Zhang, MD, Chuansheng Wang, MD, Mental Hospital of Henan Province; Na Liu, MD, Jie Zhang, MD, Jun Cai, MD, Shanghai Mental Health Centre; Ting Li, MD, Guiying Mai, MD, Guangzhou Brain Hospital; Xiyan Zhang, PhD, Xuejun Liu, MD, Hunan Brain Hospital; Xiaofang Shang, MD, Yu Cheng, MD, Min Zhou, PhD, Nanjing Brain Hospital. Statistical support was provided by Zhenqiu Sun, PhD, School of Public Health, Central South University.

References

- 1.Freedman R. Schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(18):1738–1749. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lieberman JA, Stroup TS, McEvoy JP, Swartz MS, Rosenheck RA, Perkins DO, Keefe RS, Davis SM, Davis CE, Lebowitz BD, Severe J, Hsiao JK Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) Investigators. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in patients with chronic schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(12):1209–1223. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mojtabai R, Lavelle J, Gibson PJ, Bromet EJ. Atypical antipsychotics in first admission schizophrenia: medication continuation and outcomes. Schizophr Bull. 2003;29(3):519–530. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weiden PJ, Kozma C, Grogg A, Locklear J. Partial compliance and risk of rehospitalization among California Medicaid patients with schizophrenia. Psyiatr Serv. 2004;55(8):886–891. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.8.886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Penn DL, Waldheter EJ, Perkins DO, Mueser KT, Lieberman JA. Psychosocial treatment for first-episode psychosis: a research update. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(12):2220–2232. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.12.2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenbaum B, Valbak K, Harder S, Knudsen P, Køster A, Lajer M, Lindhardt A, Winther G, Petersen L, Jørgensen P, Nordentoft M, Andreasen AH. The Danish National Schizophrenia Project: prospective, comparative longitudinal treatment study of first-episode psychosis. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186(9):394–399. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.5.394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marder SR, Wirshing WC, Mintz J, McKenzie J, Johnston K, Eckman TA, Lebell M, Zimmerman K, Liberman RP. Two-year outcome of social skills training and group psychotherapy for outpatients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1996;153(12):1585–1592. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.12.1585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turkington D, Kingdon D, Weiden PJ. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):365–373. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.3.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Granholm E, McQuaid JR, McClure FS, Link PC, Perivoliotis D, Gottlieb JD, Patterson TL, Jeste DV. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive behavioral social skills training for older people with schizophrenia: 12-month follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(5):730–737. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n0510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehman AF, Lieberman JA, Dixon LB, McGlashan TH, Miller AL, Perkins DO, Kreyenbuhl J. American Psychiatric Association; Steering Committee on Practice Guidelines. Practice guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, second edition. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(Suppl 2):s1–s56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birchwood M, Todd P, Jackson C. Early intervention in psychosis. The critical period hypothesis. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172(Suppl 33):s53–s59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, Thorup A, Øhlenschlaeger J, le Quach P, Christensen TØ, Krarup G, Jørgensen P, Nordentoft M. Five-year follow-up of a randomized multicenter trial of intensive early intervention vs standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. The OPUS trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65(7):762–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeppesen P, Petersen L, Thorup A, Abel MB, Oehlenschlaeger J, Christensen TØ, Krarup G, Hemmingsen R, Jørgensen P, Nordentoft M. Integrated treatment of first-episode psychosis: effect of treatment on family burden. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187(suppl 48):s85–s90. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.48.s85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grawe RW, Falloon IR, Widen JH, Skogvoll E. Two years of continued early treatment for recent-onset schizophrenia: a randomized controlled study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;114(5):328–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00799.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Craig TK, Garety P, Power P, Rahaman N, Colbert S, Fornells-Ambrojo M, Dunn G. The Lambeth Early Onset (LEO) Team: randomised controlled trial of the effectiveness of specialised care for early psychosis. BMJ. 2004;329(7474):1067–1072. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38246.594873.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garety PA, Craig TK, Dunn G, Fornells-Ambrojo M, Colbert S, Rahaman N, Read J, Power P. Specialised care for early psychosis: symptoms, social functioning, and patient satisfaction. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188(1):37–45. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.104.007286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guo XF, Zhao JP, Liu ZN, Zhai JG, Xue ZM, Chen JD. Antipsychotic combination with psychosocial intervention on outcome of schizophrenia (ACPIOS): rationale and design of the clinical trial. Clinical Schizophrenia & Related Psychoses. 2007;1(2):185–192. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Si TM, Shu L, Yu X, Ma C, Wang GH, Bai PS, Liu XH, Ji LP, Shi JG, Chen XS, Mei QY, Su KQ, Zhang HY, Ma H. Antipsychotic drug patterns of schizophrenia in china: a cross-sectioned study [in Chinese] Chinese Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;37(3):152–155. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lehman AF, Kreyenbuhl J, Buchanan RW, Dickerson FB, Dixon LB, Goldberg R, Green-Paden LD, Tenhula WN, Boerescu D, Tek C, Sandson N, Steinwachs DM. The schizophrenia patient outcomes research team (PORT): updated treatment recommendations 2003. Schizophr Bull. 2004;30(2):193–217. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a007071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gleeson J, Jackson H, Stavely H, Burnett P. Family interventions in early psychosis. In: McGorry PD, Henry HJ, editors. The Recognition and Management of Early Psychosis: A Preventive Approach. Combridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1999. pp. 306–406. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang M, He Y, Gittelman M, Wong Z, Yan H. Group psychoeducation of relatives of schizophrenic patients: Two-year experiences. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;52(Suppl):s344–s347. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1998.tb03264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bäuml J, Froböse T, Kraemer S, Rentrop M, Pitschel-Walz G. Psychoeducation: A basic psychotherapeutic intervention for patients with schizophrenia and their families. Schizophr Bull. 2006;32(Suppl 1):s1–s9. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Askey R, Gamble C, Gray R. Family work in first-onset psychosis: a literature review. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2007;14(4):356–365. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2850.2007.01093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Addington J, Burnett P. Working with families in the early stages of psychosis. In: McGorry PD, Gleeson JF, editors. Psychological Interventions in Early Psychosis: A Practical Treatment Handbook. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd; 2004. pp. 99–116. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Liberman RP, Eckman TA, Marder SR. Rehab rounds: Training in social problem solving among persons with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(1):31–33. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liberman RP, Wallace CJ, Blackwell G, Eckman TA, Vaccaro JV, Kuehnel TG. Innovations in skills training for the seriously mentally ill: the UCLA Social and Independent Living Skills Modules. Innovations & Research. 1993;2(2):43–60. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bellack AS, Mueser KT, Gingerich S, Agresta J. Social Skills Training for Schizophrenia, Second Edition: A Step-by-Step Guide. New York, US: Guilford Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fowler D, Garety PA, Kuipers L. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy for Psychosis: Theory and Practice. Chichester, UK: John Wiley&Sons Ltd; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Turkington D, Sensky T, Scott J, Barnes TR, Nur U, Siddle R, Hammond K, Samarasekara N, Kingdon D. A randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavior therapy for persistent symptoms in schizophrenia: a five-year follow-up. Schizophr Res. 2008;98(1–3):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Csernansky JG, Mahmoud R, Brenner R. A comparison of risperidone and haloperidol for the prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(1):16–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa002028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. pp. 76–338. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McEvoy JP, Apperson LJ, Appelbaum PS, Ortlip P, Brecosky J, Hammill K, Geller JL, Roth L. Insight in schizophrenia: Its relationship to acute psychopathology. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177(1):43–47. doi: 10.1097/00005053-198901000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ware JE, Snow KK, Kosisnki M, Gandek B. SF-36 Health Survey Manual and Interpretation Guide. Boston, Mass: The Health Institute, New England Medical Center; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. pp. 583–585. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Endicott J, Spitzer RL, Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The global assessment scale. A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33(6):766–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770060086012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: A standardized Measure of Biological and Psychosocial Function. JAMA. 1963;185(12):914–919. doi: 10.1001/jama.1963.03060120024016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lawton WP. Assessment of older people self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang MY. Chinese Version of ADL [in Chinese] Shanghai Archive of Psychiatry. 1989;1(2):68–71. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang MY, Katzman R, Salmon D, Jin H, Cai GJ, Wang ZY, Qu GY, Grant I, Yu E, Levy P, Klauber MR, Liu WT. The prevalence of dementia and Alzheimer's disease in Shanghai, China: impact of age, gender, and education. Ann Neurol. 1990;27(4):428–437. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology, Revised. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; 1976. pp. 341–350. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cox D, Oakes D. Analysis of Survival Data. London, UK: Chapman & Hall; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Everitt BS. Analysis of longitudinal data. Beyond MANOVA. Br J Psychiatry. 1998;172(1):7–10. doi: 10.1192/bjp.172.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kahn RS, Fleischhacker WW, Boter H, Davidson M, Vergouwe Y, Keet IP, Gheorghe MD, Rybakowski JK, Galderisi S, Libiger J, Hummer M, Dollfus S, López-Ibor JJ, Hranov LG, Gaebel W, Peuskens J, Lindefors N, Riecher-Rössler A, Grobbee DE EUFEST study group. Effectiveness of antipsychotic drugs in first-episode schizophrenia and schizophreniform disorder: an open randomised clinical trial. Lancet. 2008;371(9618):1085–1097. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ascher-Svanum H, Faries DE, Zhu B, Ernst FR, Swartz MS, Swanson JW. Medication adherence and long-term functional outcomes in the treatment of schizophrenia in usual care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(3):453–460. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v67n0317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Osterberg L, Blaschke T. Adherence to medication. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(5):487–497. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tunis SL, Croghan TW, Heilman DK, Johnstone BM, Obenchain RL. Reliability, validity, and application of the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short-Form Health survey (SF-36) in schizophrenic patients treated with olanzapine versus haloperidol. Med Care. 1999;37(7):678–691. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199907000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nasrallah HA, Duchesne I, Mehnert A, Janagap C, Eerdekens M. Health-Related Quality of Life in patients with schizophrenia during treatment with long-acting, injectable risperidone. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(4):531–536. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v65n0412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lewis S, Tarrier N, Haddock G, Bentall R, Kinderman P, Kingdon D, Siddle R, Drake R, Everitt J, Leadley K, Benn A, Grazebrook K, Haley C, Akhtar S, Davies L, Palmer S, Faragher B, Dunn G. Randomized controlled trial of cognitive-behavioural therapy in early schizophrenia: acute-phase outcomes. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;181(Suppl 43):s91–s97. doi: 10.1192/bjp.181.43.s91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Petersen L, Jeppesen P, Thorup A, Abel MB, Øhlenschlaeger J, Christensen TØ, Krarup G, Jørgensen P, Nordentoft M. A randomised multicentre trial of integrated versus standard treatment for patients with a first episode of psychotic illness. BMJ. 2005;331(7517):602–608. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38565.415000.E01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Petersen L, Nordentoft M, Jeppesen P, Ohlenschaeger J, Thorup A, Christensen TØ, Krarup G, Dahlstrøm J, Haastrup B, Jørgensen P. Improving 1-year outcome in first-episode psychosis: OPUS trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;187(Suppl 48):s98–s103. doi: 10.1192/bjp.187.48.s98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tarrier N, Lewis S, Haddock G, Bentall R, Drake R, Kinderman P, Kingdon D, Siddle R, Everitt J, Leadley K, Benn A, Grazebrook K, Haley C, Akhtar S, Davies L, Palmer S, Dunn G. Cognitive-behavioural therapy in first-episode and early schizophrenia: 18-month follow-up of a randomized controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184(3):231–239. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]