Abstract

In individuals with chronic kidney disease surrogates of protein-energy wasting (PEW) including a relatively low serum albumin and fat or muscle wasting are by far the strongest death risk factor than any other condition. There are data to indicate that hypoalbuminemia responds to nutritional interventions, which may save lives in the long run. Monitored, in-center provision of high-protein meals and/or oral nutritional supplements during hemodialysis is a feasible, inexpensive and patient-friendly strategy, despite concerns such as postprandial hypotension, aspiration risk, infection control and hygiene, dialysis staff burden, diabetes and phosphorus control, and financial constraints. Adjunct pharmacologic therapies can be added including appetite stimulators (megesterol, ghrelin, and mirtazapine), anabolic hormones (testosterone and growth factors), anti-myostatin agents, and anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory agents (pentoxiphylline and cytokine modulators) to increase efficiency of intradialytic food and oral supplementation although adequate evidence is still lacking. If more severe hypoalbuminemia (<3.0 g/dL) not amenable to oral interventions prevails or if patient is not capable of enteral interventions, e.g. due to swallowing problems, parenteral interventions such as intra-dialytic parenteral nutrition can be considered. Given the fact that meals and supplements during hemodialysis would require only a small fraction of the funds currently used for the expensive medications of dialysis patients with no proven outcome improvement, this is also an economically feasible strategy.

Keywords: Hypoalbuminemia, protein-energy wasting (PEW), mortality, chronic kidney disease (CKD), muscle wasting

Introduction

Overnutrition is a major problem in the general population and a serious risk of metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular disease and chronic kidney disease (CKD), with subsequent increased death risk. In CKD patients, however, this relationship may be different, especially in those who undergo maintenance dialysis treatment. In the latter patient population the so-called “uremic malnutrition”1 (or “malnutrition-inflammation complex”2 or “renal cachexia”3) which is recently also referred to as “protein-energy wasting” (PEW),4 is by far the strongest risk factor for adverse outcomes and death,5 whereas surrogates of overnutrition such as obesity or hyperlipidemia appear counterintuitively protective.6 Similar associations have been described in individuals with other chronic disease states such as heart failure7 or in the geriatric populations.8 It is believed that in CKD and other chronic diseases that are associated with wasting syndrome, pathophysiologic pathways related to malnutrition act as short-term killers and render such long-term killers as obesity or hypertension practically irrelevant. In other words, dialysis patients die much faster of short-term consequences of PEW, so that they do not live long enough to die of the long-term consequences of overnutrition. This so-called timediscrepancy hypothesis9 suggests that in CKD patient whose short-term mortality is high, interventions that can improve their nutritional status and prevent or correct wasting and sarcopenia have the potential to save lives.10 In addition to longevity, nutritional status is a strong predictor of better health-related quality of life in dialysis patients.11

PEW and Mortality

If the PEW is such as strong death risk factor, one would expect that the PEW surrogates such as low serum albumin or lower protein intake correlate with mortality. Indeed, evidence suggests they do. A low serum albumin concentration is by far the strongest predictor of mortality and poor outcomes in dialysis patients when compared to any other risk factors,12, 13 be it the traditional risk factors (hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, obesity) or nonconventional ones (anemia measures, minerals and bone surrogates, dialysis treatment and technique).5 The sensitivity of serum albumin to predict CKD patients outcomes is relatively high with such a granularity of as little as 0.2 g/dL or even smaller.14-17 In other words, a dialysis patient with a baseline serum albumin of even 0.2 g/dL higher or lower than another patient with similar demographic and comorbidity constellations has a significantly lower or higher death risk, respectively. The albumin-death association is highly incremental and linear with virtually no cutoff level below or above which the association with survival would cease or reverse.14, 15 This is in sharp contradistinction to most other outcome predictors in CKD with U- or J-shape survival associations. Even more importantly, changes in serum albumin over time are associated with proportional and reciprocal alterations in subsequent death risk, in that a rise or drop in serum albumin by as little as 0.1 g/dL over a few month period is associated with improving or worsening survival, respectively.14 Similar mortality predictabilities have also been reported with other nutritional markers such as serum prealbumin18 (e.g. <30 mg/dL) and the “malnutrition-inflammation score” (MIS≥5).19 Nevertheless, serum albumin remains the simple single test that is readily available ubiquitously and has been recommended by most nutritional societies as a first line nutritional marker. Hence, as shown in Table 1, a diverse array of nutritional and dietary interventions are often considered for maintenance hemodialysis patients with serum albumin <4.0 g/dL or other signs of protein energy wasting.

Table 1.

Suggested intervention for maintenance hemodialysis patients with serum albumin <4.0 g/dL or other signs of protein energy wasting

| Oral Nutritional Interventions | In-center, intra-dialytic administration |

Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| – Meals during dialysis treatment | Preferred as routine for all HD patients |

See Table 2 | See Table 2 |

| – Oral nutritional supplements | Preferred esp. if meals not effective |

See Table 2 | See Table 2 |

| – Tube feeding (via temporary nasogastric tubing or PEG) |

Both in- and off-center if oral nutrition not possible |

Convenient access | Can be used for fluid supplements only |

| Parenteral | |||

| – IDPN | Preferred esp. if albumin <3.0 g/dL |

Convenient | Offered only 3 times/week |

| – TPN | Usually administered off dialysis clinic |

Can be used more frequently than IDPN |

Requires an extra access line (e.g. PICC line) |

| Pharmacologic | |||

| – Appetite stimulators | To improve adherence* | Enhances protein/energy intake |

May aggravate obesity, more fat accumulation than muscle? |

| – Anti-depressant | To improve adherence* | May improves appetite | Known side effects |

| – Anti-inflammatory and/or anti-oxidative | To improve adherence* | May improve inflammatory / oxidative profile |

Limited studies, unknown side effects |

| – Anabolic hormones | To improve adherence* | May enhance muscle accretion rather than fat |

Adverse events associated with anabolic steroid |

| – Anti-myostatin and/or other muscle enhancing agents |

To improve adherence* | May enhance muscle accretion |

Limited human studies, unknown side effect profile |

| Other Interventions | |||

| – Dialysis Technique | n/a | Implemented as a part of routine treatment renovation |

May cost more when compared to older techniques |

| – Dialysis Treatment Factors | n/a | Implemented during routine treatment |

Costs/benefits should be weighed |

| – Intradialytic Exercise | Preferred | Improves both muscle mass and function |

Requires instrument provision and maintenance; technically might be challenging |

Not clear whether intra-dialytic (in-center) administration can offer any benefit beyond improving adherence to high protein diet and supplements including during hemodialysis therapy.

Meals and Oral Supplements During Hemodialysis Treatment

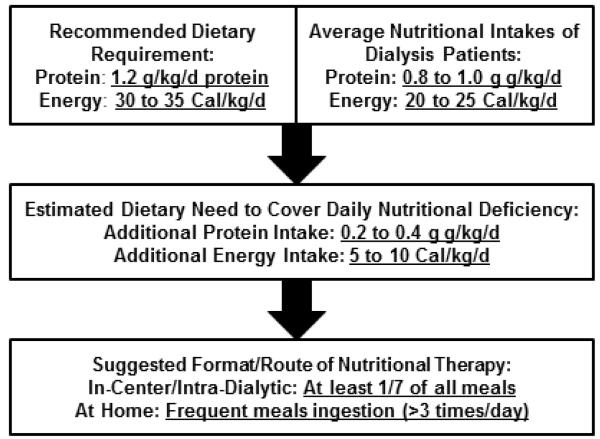

Given the exceptionally high dietary protein requirement of dialysis patients (~1.2 g/kg/day) and given the observation that most dialysis patients eats <1.0 g/kg/day of protein,20 an average dialysis patient needs an additional 0.2 to 0.4g/kg/day of protein supplement21 (see Figure 1). Inadequate food intake especially during hemodialysis treatment days is a common practice among American dialysis patients, while in many other countries meals are routinely served during the hemodialysis treatment sessions. Table 2 summarizes some of the pros and cons pertaining to in-center (in the dialysis clinic) monitored eating and the provision of meals during hemodialysis treatments. In a recent online survey, when we asked nephrologists and dialysis centers in the United States as to why meal trays for patients do not exist during hemodialysis treatment, the common stated concerns include: (1) postprandial hypotension, (2) risk of choking or aspiration, (3) infection control and hygiene issues, including fear of fecal-oral transmission of such diseases as Hepatitis A, (4) staff burden and distraction, and (5) diabetes and phosphorus control (see Table 2).21 It is not unusual to hear statements such as: “They get food everywhere and this is not fair to the next patient that has to sit in their crumbs.”; “I don’t want another lawsuit for choking while eating on dialysis” ; and “Having a full stomach might complicate their management.”22 Conversely, meals are routinely given to dialysis outpatients in most European and South East Asian countries. German dialysis patients eat invariably during their hemodialysis treatments and have higher serum albumin and greater survival than their American counterparts.23 In the past, meals on dialysis were routine in the United States as well. Indeed a few Veteran Administrations hospitals still provide meal trays including breakfast, lunch or supper during all dialysis shifts, be it inpatient or outpatient.

Figure 1.

Justification of the additional need of dialysis patients to supplemented meals and nutrition

Table 2.

Pros and cons of in-center (in the dialysis clinic) monitored eating and provision of meals during hemodialysis treatments

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

|

Impact on nutritional status and clinical outcomes > Meals during HD is practiced routinely in many industrialized nations including Europe and South East Asia > Excellent survival in most countries where meals are served during HD > No major unfavorable outcomes reported in countries offering meals during HD |

Low blood pressure and labile circulation during food ingestion > blood pressure may be lowered during and after eating due to splanchnic circulation expansion even with new dialysis treatment and techniques > Hypotensive episode may lead to shortening dialysis Rx or less efficient fluid removal |

|

Mitigates/corrects intra- and post-dialysis catabolism > HD Rx exerts catabolic effects that can be avoided by eating during HD > Muscle wasting may be mitigated > Effectively increases the frequency of daily meal intakes |

Risk of aspiration and other respiratory complications > Risk of choking is likely higher in patients with a history of neurologic disorders, swallowing problems or other disabilities > Even in sitting position aspiration may happen in patient who cannot feed themselves at home |

|

Better control of dietary phosphorus, potassium, salt and fluid > In-center meals and supplements can be more optimally prepared for the specific needs of CKD patients > In-center meals may improve adherence to restricted salt and fluid intake > Intake of phosphorus binder can be monitored > Improved patient education can be achieved by simultaneous interaction with dietitian and nephrologist while eating |

Infectious control and hygiene issues > Fecal–oral transmission of infection including hepatitis A possible > Food crumbs may lead to infestation > Risk if ingestion of rotten food and food poisoning is possible > Meal tray delivery and storage may pose additional hygiene challenges |

|

Increased adherence with hemodialysis treatment > Increases the likelihood of attending HD treatment >May mitigate the likelihood of HD treatment shortening by hungry patients > Enhances communication between patients and dietitians and other clinic staff |

Burden on dialysis staff and logistics constraints > Overworked dialysis staff face with additional responsibilities > Providing nutrition may not be regarded as an a justifiable part of patient care in dialysis clinics |

|

Improved patient satisfaction and quality of life > In-center meals may make patients more content with dialysis treatment life style > Improved quality of life by means of in-center meal may improve survival |

Only a fraction of required meals are provided > Thrice-weekly meals account for 15% of all meals > The evidence that catabolic effect of HD can be mitigated or reversed by intradialytic nutrition is not convincing |

|

Relatively low costs of meals on HD > The costs of providing in-center meals is a small fraction of expensive medications used in ESRD > Dialysis organizations can adapt this in form of efficient and economical approaches |

Added expenses to dialysis treatment > The costs of meals during dialysis may be small but still not negligible > If costs of meals are factored in by the insurance company or in the bundling equation, this may be at the cost of other more critical treatment components and medications |

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; PEW, protein-energy wasting.

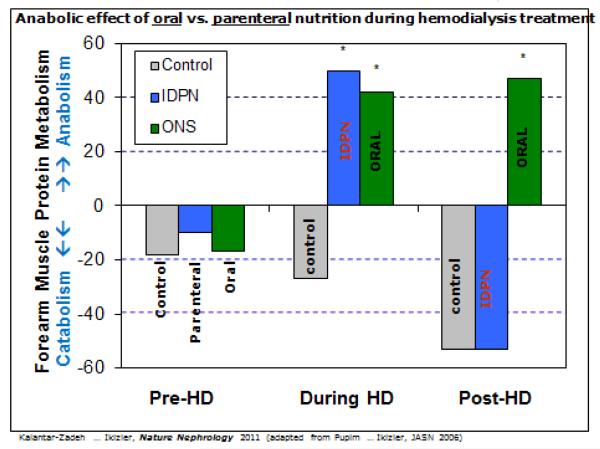

Despite the traditional concerns of North American nephrologists and dialysis care providers, the positive development is that over the past few years increasing numbers of dialysis clinics have allowed and even encourage oral nutritional supplement during the treatment. Indeed several recent pilot and non-randomized studies have indicated that provision of oral nutritional supplements with high protein content during hemodialysis has improved serum albumin.24-27 Indeed an elaborate metabolic study showed that oral protein intake during hemodialysis therapy is effective in opposing the catabolic effect of hemodialysis treatment that would otherwise last even hours after the therapy ended.24 We would also argue that in addition to improving nutritional status, providing in- center meals and/or oral nutritional supplements during hemodialysis treatment would improve patient compliance and satisfaction (see Table 2). Patients may be more motivated to attend the treatments when they know that a lunchbox is awaiting them. Even though in Europe meals on dialysis rarely lead to hypotension, we would argue that it can be considered as an effective strategy against intradialytic hypertension. Many patients may already ignore the eating-prohibitory regulations of some dialysis clinics and still bring in their own foods including ones with high phosphorus content and super-sized soft drinks. Hence, we are in the position to offer them a better and more appropriate food or supplement with higher protein content and lower phosphorus to protein ratio28 and lower potassium content.29 The in-center food can be offered along with directly observed administration of phosphorus binder regimen and required multivitamins at the time of meal or supplement intake.

There are several studies in which oral nutrition has been provided during hemodialysis treatment including studies by Szklarek-Kubicka et al.30 and Moreira et al.31 In a more recent controlled trial known as the “Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidative Nutrition during Dialysis” (AIONID) Study,32 84 adult hypoalbuminemic (albumin<4.0 g/dL) 84 hemodialysis patients were double-blindly randomized to receive 16 weeks of interventions including oral nutritional supplement (ONS), pentoxifylline, ONS with pentoxifylline, or placebos during hemodialysis treatments; and these 4 groups were associated with an average change in serum albumin of +0.21 (p=0.004), +0.14 (p=0.008), +0.18 (p=0.001) and, +0.03 g/dL (p=0.59), respectively. However, in a pre-determined internet-to-treat regression analysis only ONS during hemodialysis without pentoxifylline was associated with a significant albumin rise (+0.17±0.07 g/dL, p=0.018).32 In two recent large observational studies, ONS during hemodialysis was associated with improved survival33 and improved hospitalization.34 In another recent randomized controlled trial known as “Fosrenol for Enhancing Dietary Protein Intake in Hypoalbuminemic Dialysis Patients” (FrEDI) Study35 (ClinicalTrials.gov # NCT0111694110) in 110 hypoalbuminemic (<4.0mg/dL) hemodialysis patients received meals during hemodialysis for 8 weeks, the intervention group received high protein meals as prepared meal boxes (50g protein, 850Cal, phosphorus to protein ratio <10mg/gm) along with 0.5 to 1.5g lanthanum carbonate (Fosrenol) titrated as needed to control phosphorus burden from the high protein meals), whereas the control group received meal boxes containing low calorie (<50 Cal) and almost no protein (<1g, such as salads) during each hemodialysis treatment. Among the 51 intervention and 55 control subjects who qualified for the intention-to-treat analyses, the combined rise in albumin ≥0.2g/dL while maintaining phosphorus in 3.5-<5.5mg/dL range was achieved in 25.5% and 9.8%, respectively (χ2 p-value 0.036). No serious adverse events were reported, and patients reported satisfaction with high protein meals during hemodialysis.35 Hence, in the FREDI Study provision of high protein meals combined with a potent binder during hemodialysis treatment was safe and improved serum albumin while controlling serum phosphorus.35 In summary given the above studies, we suggest provision of maintenance meals (as in FREDI Study)35 or balanced dietary supplement (as in AIONID Study)32 during each and every hemodialysis treatment and dialysis clinic visit. A maintenance regimen can assure adequate protein intake and reinforce similar dietary habits at home. We also recommend the frequent intake of small amount of protein-rich liquid oral supplement with prescribed pills to replace water, which is shown to improve outcomes in geriatric and nursing home patients.36

Other Nutritional Interventions

In addition to meals and nutritional supplements during hemodialysis, there are other potential interventions that can be used in conjunction or alone to improve the nutritional status of dialysis patients. These include, but are not limited to appetite stimulators with or without antidepressant properties such as megesterol37 ghrelin,38 and mirtazapine;39 anabolic hormones such as testosterone and growth factors;40 and anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory agents such as pentoxiphylline and cytokine modulatory agents,41, 42 or omega-3 fatty acid43 (see Table 1). Intradialytic exercise with or without concomitant nutritional supplementation has been proposed as a potential therapy although long-term efficacy of this strategy needs to be confirmed. 44, 45If more severe hypoalbuminemia (e.g. <3.0 g/dL) prevails that is not amenable to oral interventions even with adjunct pharmacologic therapy, or if patient is not capable of enteral interventions, parenteral interventions should be considered such as intra-dialytic parenteral nutrition (IDPN).46, 47 The IDPN is especially effective with such low serum albumin values.48 Finally, nonnutritional interventions should also be considered such as dialysis treatment modalities and techniques that leads to less inflammation or protein loss.49, 50

Impact of Nutritional Interventions on Outcomes

An important question that is still unanswered is whether the PEW-albumin-death association a causal association (and amenable to interventions listed in Table 1) or an epiphenomenon? Whereas the debate continues as to how to find the correct answer to this question,51-53 in our opinion a more clinically relevant and time-sensitive question is the following: “Can a nutritional intervention increase serum albumin in CKD patients and by doing so improve survival and quality of life?” We believe that the answer is positive based on a number of experimental data,48, 54-59 even though to date no single well-designed and well-performed randomized controlled trial with adequate sample size has been performed to answer this simple question. Indeed the entire field of Nutritional support (such as in terminal cancer patients, post-surgical patients or geriatric or disabled populations) is based on the premise that independent of the cause of wasting and cachexia, provision of nutritional support improves patient’s immediate and short-term outcomes, or we would not be practicing it over the past few decades.60 Whereas we do not deny the paucity of the controlled trials and the difficulties sounding the feasibility of nutritional interventions and testing their effects on hard outcomes,61 it is our opinion that keeping hemodialysis patients hungry during dialysis treatment is not an appropriate action, both clinically and ethically.

Conclusion Remarks

There appears to be a consensus pertaining to the important role of favorable nutritional status in dialysis patient outcomes within the nephrology community. As we have moved towards longer hemodialysis sessions62 and in anticipation of drastic changes in practice pattern and dialysis patient care in many countries, we need to rethink the pros and cons of provision of meals and oral supplements during dialysis treatment. While this is a routine practice in Europe and most other countries, Northern American dialysis patients are deprived of nutritional intervention during dialysis. There is consistent, strong and robust association of nutritional status, and in particular serum albumin level, with survival in CKD patients along with data from several studies indicating improvement in response to intradialytic nutritional supplementation. Hence, providing intradialytic meals or oral nutritional supplements to dialysis patients and other nutritional interventions are the most promising intervention to increase serum albumin and to improve longevity and quality of life in this patient population. Since provision of meals and oral supplements would require only a small fraction of the funds currently used for the expensive medications given to dialysis patients with no proven outcome modification, this is also an economically feasible strategy 63

Figure 2.

Anabolic effects of oral versus parenteral nutrition during hemodialysis treatment to justify preference for meals and oral supplements during hemodialysis treatment (this figure is adapted from Kalantar-Zadeh et al21 and Pupim et al24)

Acknowledgments

Funding Source: The manuscript was supported by the research grant R01-DK078106, R21-DK078012 and K24-DK091419 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Disease of the National Institute of Health for the authors.

Footnotes

Potential Conflict of Interest and Disclosures: KKZ has received honoraria and/or research grants from Abbott, Amgen, BBraun, DaVita, Fresenius, Genzyme, Otsuka, Shire and/or Vifor, and has served as an expert witness in legal proceedings that pertain to the role of nutrition in dialysis patients. TAI has received consultant fees from Abbott Renal Care, Abbott Nutrition, Amgen, Inc, Fresenius Medical Care, North America, Renal Advantage, Inc., Baxter Renal and Fresenius-Kabi, Germany.

Practical Application: Meals and oral supplements during hemodialysis treatment session may improve outcomes and offers more benefits than risks.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pupim LB, Caglar K, Hakim RM, et al. Uremic malnutrition is a predictor of death independent of inflammatory status. Kidney Int. 2004;66:2054–2060. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2004.00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Ikizler TA, Block G, et al. Malnutrition-inflammation complex syndrome in dialysis patients: Causes and consequences. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:864–881. doi: 10.1016/j.ajkd.2003.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mak RH, Ikizler AT, Kovesdy CP, et al. Wasting in chronic kidney disease. J Cachex Sarcopenia Muscle. 2011;2:9–25. doi: 10.1007/s13539-011-0019-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fouque D, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple J, et al. A proposed nomenclature and diagnostic criteria for protein-energy wasting in acute and chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2008;73:391–398. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Why is protein-energy wasting associated with mortality in chronic kidney disease? Semin Nephrol. 2009;29:3–14. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP, Derose SF, et al. Racial and survival paradoxes in chronic kidney disease. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol. 2007;3:493–506. doi: 10.1038/ncpneph0570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Oreopoulos A, Padwal R, Kalantar-Zadeh K, et al. Body mass index and mortality in heart failure: a meta-analysis. Am Heart J. 2008;156:13–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oreopoulos A, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Sharma AM, et al. The obesity paradox in the elderly: potential mechanisms and clinical implications. Clin Geriatr Med. 2009;25:643–659. viii. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2009.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Block G, Horwich T, et al. Reverse epidemiology of conventional cardiovascular risk factors in patients with chronic heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1439–1444. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Abbott KC, Salahudeen AK, et al. Survival advantages of obesity in dialysis patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:543–554. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.3.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Feroze U, Noori N, Kovesdy CP, et al. Quality-of-life and mortality in hemodialysis patients: roles of race and nutritional status. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2011;6:1100–1111. doi: 10.2215/CJN.07690910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lacson E, Jr., Wang W, Hakim RM, et al. Associates of mortality and hospitalization in hemodialysis: potentially actionable laboratory variables and vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:79–90. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beddhu S, Kaysen GA, Yan G, et al. Association of serum albumin and atherosclerosis in chronic hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2002;40:721–727. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2002.35679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kilpatrick RD, Kuwae N, et al. Revisiting mortality predictability of serum albumin in the dialysis population: time dependency, longitudinal changes and population-attributable fraction. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2005;20:1880–1888. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfh941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lacson E, Jr., Ikizler TA, Lazarus JM, et al. Potential impact of nutritional intervention on end-stage renal disease hospitalization, death, and treatment costs. J Ren Nutr. 2007;17:363–371. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehrotra R, Duong U, Jiwakanon S, et al. Serum albumin as a predictor of mortality in peritoneal dialysis: comparisons with hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:418–428. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Molnar MZ, Kovesdy CP, Bunnapradist S, et al. Associations of pretransplant serum albumin with post-transplant outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:1006–1015. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2011.03480.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rambod M, Kovesdy CP, Bross R, et al. Association of serum prealbumin and its changes over time with clinical outcomes and survival in patients receiving hemodialysis. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1485–1494. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.25906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rambod M, Bross R, Zitterkoph J, et al. Association of Malnutrition-Inflammation Score with quality of life and mortality in hemodialysis patients: a 5-year prospective cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;53:298–309. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2008.09.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shinaberger CS, Greenland S, Kopple JD, et al. Is controlling phosphorus by decreasing dietary protein intake beneficial or harmful in persons with chronic kidney disease? Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1511–1518. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Cano NJ, Budde K, et al. Diets and enteral supplements for improving outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2011;7:369–384. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2011.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalantar-Zadeh K. Why Not Meals During Dialysis? Renal & Urology News. 2009;9:4. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wizemann V. Regular dialysis treatment in Germany: the role of non-profit organisations. J Nephrol. 2000;13(Suppl 3):S16–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pupim LB, Majchrzak KM, Flakoll PJ, et al. Intradialytic oral nutrition improves protein homeostasis in chronic hemodialysis patients with deranged nutritional status. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;17:3149–3157. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006040413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Caglar K, Fedje L, Dimmitt R, et al. Therapeutic effects of oral nutritional supplementation during hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2002;62:1054–1059. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2002.00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sundell MB, Cavanaugh KL, Wu P, et al. Oral protein supplementation alone improves anabolism in a dose-dependent manner in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2009;19:412–421. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2009.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Oral bicarbonate: renoprotective in CKD? Nat Rev Nephrol. 2010;6:15–17. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Noori N, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP, et al. Association of dietary phosphorus intake and phosphorus to protein ratio with mortality in hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;5:683–692. doi: 10.2215/CJN.08601209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Noori N, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kovesdy CP, et al. Dietary Potassium Intake and Mortality in Long-term Hemodialysis Patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010 doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Szklarek-Kubicka M, Fijalkowska-Morawska J, Zaremba-Drobnik D, et al. Effect of intradialytic intravenous administration of omega-3 fatty acids on nutritional status and inflammatory response in hemodialysis patients: a pilot study. J Ren Nutr. 2009;19:487–493. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moreira AC, Gaspar A, Serra MA, et al. Effect of a sardine supplement on C-reactive protein in patients receiving hemodialysis. J Ren Nutr. 2007;17:205–213. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rattanasompattikul M, Molnar MZ, Lee ML, et al. Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Oxidative Nutrition in Hypoalbuminemic Dialysis Patients (AIONID) Study: Results of the Pilot-Feasibility Double-Blind Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2013 doi: 10.1007/s13539-013-0115-9. [in press] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lacson E, Jr., Wang W, Zebrowski B, et al. Outcomes associated with intradialytic oral nutritional supplements in patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis: a quality improvement report. Am J Kidney Dis. 2012;60:591–600. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2012.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cheu C, Pearson J, Dahlerus C, et al. Association between Oral Nutritional Supplementation and Clinical Outcomes among Patients with ESRD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2012 doi: 10.2215/CJN.13091211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Koontz T, Balikian S, Bross R, et al. Fosrenol for Enhancing Dietary Protein Intake in Hypoalbuminemic Dialysis Patients (FrEDI) Study. Kidney Research and Clinical Practice. 2012;31:A68. [abstract] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Potter JM. Oral supplements in the elderly. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2001;4:21–28. doi: 10.1097/00075197-200101000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rammohan M, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Liang A, et al. Megestrol acetate in a moderate dose for the treatment of malnutrition-inflammation complex in maintenance dialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15:345–355. doi: 10.1016/j.jrn.2004.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rodriguez Ayala E, Pecoits-Filho R, Heimburger O, et al. Associations between plasma ghrelin levels and body composition in end-stage renal disease: a longitudinal study. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2004;19:421–426. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Riechelmann RP, Burman D, Tannock IF, et al. Phase II trial of mirtazapine for cancer-related cachexia and anorexia. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27:106–110. doi: 10.1177/1049909109345685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pupim LB, Flakoll PJ, Yu C, et al. Recombinant human growth hormone improves muscle amino acid uptake and whole-body protein metabolism in chronic hemodialysis patients. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;82:1235–1243. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/82.6.1235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldberg RM, Loprinzi CL, Mailliard JA, et al. Pentoxifylline for treatment of cancer anorexia and cachexia? A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 1995;13:2856–2859. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1995.13.11.2856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kovesdy CP, Kalantar-Zadeh K. Novel targets and new potential: developments in the treatment of inflammation in chronic kidney disease. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2008;17:451–467. doi: 10.1517/13543784.17.4.451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Noori N, Dukkipati R, Kovesdy CP, et al. Dietary omega-3 fatty acid, ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 intake, inflammation, and survival in long-term hemodialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:248–256. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dong J, Sundell MB, Pupim LB, et al. The effect of resistance exercise to augment long-term benefits of intradialytic oral nutritional supplementation in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2011;21:149–159. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pupim LB, Flakoll PJ, Levenhagen DK, et al. Exercise Augments the Acute Anabolic Effects of Intradialytic Parenteral Nutrition in Chronic Hemodialysis Patients. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2004;286:E589–597. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00384.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ikizler TA. Nutrition support for the chronically wasted or acutely catabolic chronic kidney disease patient. Semin Nephrol. 2009;29:75–84. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dukkipati R, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD. Is there a role for intradialytic parenteral nutrition? A review of the evidence. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:352–364. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dezfuli A, Scholl D, Lindenfeld SM, et al. Severity of hypoalbuminemia predicts response to intradialytic parenteral nutrition in hemodialysis patients. J Ren Nutr. 2009;19:291–297. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2009.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ikizler TA, Flakoll PJ, Parker RA, et al. Amino acid and albumin losses during hemodialysis. Kidney International. 1994;46:830–837. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tayeb JS, Provenzano R, El-Ghoroury M, et al. Effect of biocompatibility of hemodialysis membranes on serum albumin levels. Am J Kidney Dis. 2000;35:606–610. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(00)70005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Friedman AN, Fadem SZ. Reassessment of albumin as a nutritional marker in kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:223–230. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009020213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Danielski M, Ikizler TA, McMonagle E, et al. Linkage of hypoalbuminemia, inflammation, and oxidative stress in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis therapy. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42:286–294. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00653-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kaysen GA, Chertow GM, Adhikarla R, et al. Inflammation and dietary protein intake exert competing effects on serum albumin and creatinine in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int. 2001;60:333–340. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pupim LB, Flakoll PJ, Ikizler TA. Nutritional supplementation acutely increases albumin fractional synthetic rate in chronic hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15:1920–1926. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000128969.86268.c0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Braglia A, Chow J, et al. An anti-inflammatory and antioxidant nutritional supplement for hypoalbuminemic hemodialysis patients: a pilot/feasibility study. J Ren Nutr. 2005;15:318–331. doi: 10.1016/j.jrn.2005.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Akpele L, Bailey JL. Nutrition counseling impacts serum albumin levels. J Ren Nutr. 2004;14:143–148. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leon JB, Majerle AD, Soinski JA, et al. Can a nutrition intervention improve albumin levels among hemodialysis patients? A pilot study. J Ren Nutr. 2001;11:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s1051-2276(01)79890-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bronich L, Te T, Shetye K, et al. Successful treatment of hypoalbuminemic hemodialysis patients with a modified regimen of oral essential amino acids. J Ren Nutr. 2001;11:194–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Eustace JA, Coresh J, Kutchey C, et al. Randomized double-blind trial of oral essential amino acids for dialysis-associated hypoalbuminemia. Kidney Int. 2000;57:2527–2538. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00112.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kalantar-Zadeh K, Kopple JD. Relative contributions of nutrition and inflammation to clinical outcome in dialysis patients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2001;38:1343–1350. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2001.29250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kaysen GA. Serum albumin concentration in dialysis patients: why does it remain resistant to therapy? Kidney Int Suppl. 2003:S92–98. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.64.s87.14.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Miller JE, Kovesdy CP, Nissenson AR, et al. Association of hemodialysis treatment time and dose with mortality and the role of race and sex. Am J Kidney Dis. 2010;55:100–112. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lacson E, Jr., Ikizler TA, Lazarus JM, et al. Potential Impact of Nutritional Intervention on ESRD Hospitalization, Death and Treatment Costs. Journal of Renal Nutrition. 2007;17:363–371. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]