Abstract

Understanding the causes of variation in clinical manifestations of disease should allow for design of new or improved therapeutic strategies to treat the disease. If variation is caused by genetic differences between individuals, identifying the genes involved should present therapeutic targets, either in the proteins encoded by those genes or the pathways in which they function. The technology to identify and genotype the millions of variants present in the human genome has evolved rapidly over the past two decades. Originally only a small number of polymorphisms in a small number of subjects could be studied realistically, but speed and scope have increased nearly as dramatically as cost has decreased, making it feasible to determine genotypes of hundreds of thousands of polymorphisms in thousands of subjects. The use of such genetic technology has been applied to cystic fibrosis (CF) to identify genetic variation that alters the outcome of this single gene disorder. Candidate gene strategies to identify these variants, referred to as “modifier genes,” has yielded several genes that act in pathways known to be important in CF and for these the clinical implications are relatively clear. More recently, whole-genome surveys that probe hundreds of thousands of variants have been carried out and have identified genes and chromosomal regions for which a role in CF is not at all clear. Identification of these genes is exciting, as it provides the possibility for new areas of therapeutic development.

Keywords: polymorphism, genotype, phenotype

Cystic Fibrosis Background

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common lethal autosomal recessive disease in Caucasians, affecting an estimated 1 in 3,300 live-born infants (Davis et al., 1996). Affected individuals have variants in both copies of the 230-kb CF transmembrane conductance regulator gene (CFTR), that result in significant reduction or absence of CFTR function. The CFTR gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 7 at position 7q31and encodes a 1,480 amino acid protein (Riordan et al., 1989; Rommens et al., 1989) with cAMP-dependent anion channel activity (Bear et al., 1992) found in the apical membranes of epithelial cells in the lungs, olfactory sinuses, pancreas, intestines, vas deferens, and sweat ducts, as well as non-epithelial cells such as immune cells (myeloid and lymphocytes) and various muscle cell types (Yoshimura et al., 1991; Krauss et al., 1992; McDonald et al., 1992; Dong et al., 1995; Moss et al., 2000; Robert et al., 2005; Di et al., 2006; Vandebrouck et al., 2006; Divangahi et al., 2009; Lamhonwah et al., 2010). Low or absent CFTR function in the airway epithelium not only results in decreased chloride permeability, but also in increased sodium absorption across the epithelium, impairing hydration of the airway mucosal surface and resulting in thick, sticky mucus and an environment for bacteria to thrive. Thus, typical clinical features of CF include chronic infection and inflammation of the airways. Accordingly, a hallmark characteristic of the CF airways is progressive bronchiectasis; this destruction and dilation of the airways is the primary cause of morbidity and mortality of CF patients. In addition to the airway manifestations, most CF patients will experience exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, males are most often sterile, and other co-morbidities such as liver disease and diabetes are common as well. Previously considered almost exclusively a pediatric disease, CF babies now have a predicted median survival of nearly 40 years (Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry, 2009).

Heterogeneity of CFTR

To date, over 1,800 CF-associated mutations have been described1 and the effects of these mutations have been grouped into six general classes based on the consequence to CFTR message and/or protein (Zielenski, 2000). These range from complete absence of full-length, functional CFTR protein (class I), proteins that do not traffic to the membrane well due to misfolding (class II), proteins that reach the membrane but do not respond to activation stimuli such as phosphorylation (class III), proteins that reach the membrane and activate, but do not conduct anions sufficiently to prevent disease (class IV), mutations that reduce the amount of functional CFTR, such as by gene expression regulation or protein trafficking (class V), and proteins that are unstable and experience increased turnover in the plasma membrane (class VI). It should be noted that these classes are not mutually exclusive, as a single change may have multiple effects on the protein.

Given the diversity of mutations, it is perhaps not surprising that there is a wide range of phenotypic variability in CF simply due to variation in CFTR. Many reports of correlations between CFTR genotype and clinical phenotype exist (Kerem et al., 1990a; Stuhrmann et al., 1991; The Cystic Fibrosis Genotype-Phenotype Consortium, 1993; Tsui and Durie, 1997; Zielenski, 2000), with the most extensive catalog to date carried out as an international effort2 and currently includes data on over 35,000 patients. Because most CF mutations are rare, surveying such a large number of individuals makes it possible to most reliably assess the phenotypic effects associated with a genotype, rather than extrapolate from individual cases.

In addition to CFTR genotype, there is evidence that gender contributes to phenotypic variability (Davis, 1999). Females are reported to have a reduced median survival age (by approximately 3 years), an earlier average age of Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in the lungs, greater rates of pulmonary decline, and elevated resting energy expenditure when compared to males (Demko et al., 1995; Corey et al., 1997; Allen et al., 2003). Although some current studies replicate these findings (Barr et al., 2011; Reid et al., 2011), others show no evidence of a gender gap and propose that phenotypic variability could be attributed to non-uniformity of care or the need to account for other factors such as body habitus, presence of diabetes, or the finding that females are more likely to be diagnosed later in life than males (Widerman et al., 2000; Milla et al., 2005; Rodman et al., 2005; Verma et al., 2005; Stern et al., 2008; Fogarty et al., 2012).

Genomic Heterogeneity and Clinical Variation

Even among patients with the same CFTR genotype, there is a wide range of phenotypic variability (Kerem et al., 1990a; Tsui and Durie, 1997). Perhaps most notably, there is remarkable variation of pulmonary phenotype, with some patients maintaining normal lung function well into adolescence and adulthood while others do quite poorly even at a very young age (Kerem et al., 1990a). Understanding the causes of this variation is important, as it provides insight into developing new therapies, or improving existing ones.

Clearly environmental factors contribute to clinical variation; exposure to tobacco smoke, bacterial infections, and socioeconomic status have all been implicated as having detrimental effects on pulmonary phenotype of CF patients (Kerem et al., 1990b; Rubin, 1990; Corey and Farewell, 1996; Schechter et al., 2001; O’Connor et al., 2003) while improvement of nutritional status, through aggressive treatment, has been associated with improvements in pulmonary phenotype (Steinkamp and von der Hardt, 1994). Each of the environmental sources of clinical variation provide potential intervention points, but it is also clear that there are heritable sources (Mekus et al., 2000; Vanscoy et al., 2007) of variation as well and that may provide insight into even more therapeutic targets.

Evidence of Genetic Modifiers of Disease

Human twin and sibling studies have been useful in verifying the role of modifier genes, and quantifying their contribution to phenotypic variation. Mekus et al. (2000) found in a survey of 277 sibling pairs, with 29 monozygous and 12 dizygous pairs, that a combined index of lung function and body mass was more concordant among monozygous twins (sharing 100% of genetic material) than dizygous twins or other sibling pairs (sharing 50% of genetic material), pointing to a genetic etiology of variation. Similarly, Vanscoy et al. (2007) examined the pulmonary phenotype of 57 twin pairs and 231 sibling pairs with CF. Lung function measurements were significantly more concordant between monozygous twins than dizygous twins, also indicating the presence of genetic modifiers. The similarity in lung function between sibling pairs was compared to the similarity in lung function in unrelated patients, and again was found to be more similar. Heritability estimates were calculated from these data, and it was determined that non-CFTR genetic variation could account for approximately 50–80% of the pulmonary phenotypic variability in CF patients with the same CFTR genotype (homozygous F508del) (Vanscoy et al., 2007).

Genetic Approaches

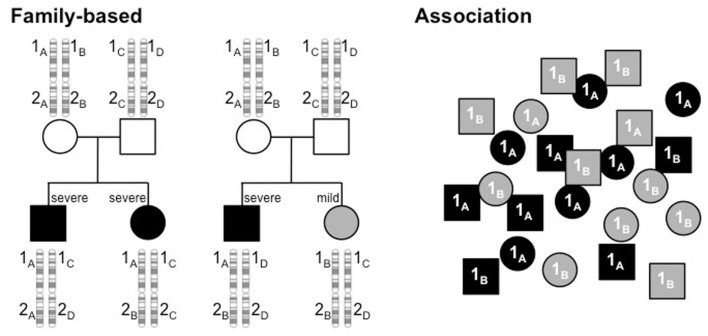

With a genetic component established, the next task at hand was to identify the genes responsible. There are two fundamental strategies by which to accomplish this. One requires family information and is often referred to as linkage analysis. Through this approach, one determines whether a polymorphism’s genotype is concordant in siblings with similar clinical profiles, discordant when clinical features are discordant or show no pattern. The other approach is association, determining if particular alleles of a polymorphism are distributed randomly among patients or have skewed distributions that track with clinical characteristics. These two approaches are outlined in Figure 1 and the findings that these strategies have produced are listed in Table 1 with several examples described in more detail below.

Figure 1.

Linkage analysis tracks alleles of polymorphisms through families to determine if an allele is linked to a phenotype. In this example, alleles of gene 1, 1A, 1B, 1C, and 1D, track with severity (black, severe; gray, mild), showing concordant genotypes between siblings with similar phenotypes (left pedigree) and discordant genotypes when phenotypes are dissimilar (right pedigree). In contrast, genotype and phenotype show no relationship at polymorphism 2. Association studies examine a population of unrelated individuals to determine if particular alleles of a polymorphism are found in different proportions, depending on the disease profile. In the example here, alleles 1A and 1B have equal frequencies in the population, but 1A is much higher in the severely affected subjects (black) and 1B higher in the mildly affected subset (gray).

Table 1.

Summary of published cystic fibrosis pulmonary modifiers.

| Gene/locus | Genes involved | Variant aliases | Variant position (rs no.) | Phenotypes tested | Association p-value | Source n (reference) | Replication n (reference) | Tested, not replicated n (reference) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8.1AH |

LTA TNF |

+252 A > G −308 G > A |

909253 1800629 |

FEV1 % pred Chronic P. aeruginosa colonization |

<0.04 0.99 |

404 (Corvol et al., 2012) | ||

|

HSP70-2 RAGE |

1267 A > G −429 T > C |

106158 1800625 |

||||||

| 8.1MHC |

AGER HSP70-2 |

−429 T > C 1267 A > G |

106158 | Age at onset of colonization Frequency of colonization | 0.036 0.012 |

72 (Laki et al., 2006) | ||

| TNFA | G-308A | |||||||

| 11p13 |

APIP EHF |

12793173 | FEV1 % pred (adjusted) | 3.34 × 10−8 | 1,978 (Wright et al., 2011) | 557 (Wright et al., 2011) | ||

| 19q13 | hCFM1 | APOC2, D19S219, D19S112 haplotype | FEV1 % pred | 0.779 | 197 sib pairs (Zielenski et al., 1999) | |||

| A1AT | SERPINA1 | 1237 G > A | 11568814 | FEV1 % pred CXR score Age at onset of P. aeruginosa | 0.368 0.813 0.146 |

157 (Mahadeva et al., 1998b) | 716 (Frangolias et al., 2003) | 124 (Henry et al., 2001) 320(Courtney et al., 2006) 808 (Drumm et al., 2005) |

| S allele Z allele | 17580 28929474 |

FEV1% pred CXR score Age at onset of P. aeruginosa | 0.043 0.127 0.899 |

157 (Mahadeva et al., 1998b) | 215 (Doring et al., 1994) 79 (Mahadeva et al., 1998a) | 124 (Henry et al., 2001) 269 (Meyer et al., 2002) 808 (Drumm et al., 2005) | ||

| ABCC1 | MRP-1 | 4741 C > G | 504348 | Age at onset of P. aeruginosa Age at which FEV1 < 60% | 0.0644 <0.05 |

203 (Mafficini et al., 2011) | ||

| FEV1 % pred | 0.52 | |||||||

| ABO | T99T 21404 C > A |

8176719 8176720 1053878 |

Pulmonary disease severity Age at onset of P. aeruginosa | No association No association | 778 (Taylor-Cousar et al., 2009) | |||

| R176G | 7853989 | |||||||

| 21583 T > A | 8176740 | |||||||

| H219H | 8176741 | |||||||

| P227P | 8176742 | |||||||

| 816750 | ||||||||

| 66119 G > A | 8176472 | |||||||

| ACE | Insertion or deletion | Age of first P. aeruginosa infection | 0.9 | 261 (Arkwright et al., 2003) | 808 (Drumm et al., 2005) | |||

| Age at which FEV1 < 50% | 0.03 (0.04)§ | |||||||

| Age of death | No association | |||||||

| ADRB2 | Arg16Gly | 1042713 | FEV1 % pred FVC | <0.05 <0.05 |

126 (Buscher et al., 2002) | 808 (Drumm et al., 2005) | ||

| Flows at lower lung volumes | <0.01 | |||||||

| 5 year decline in pulmonary function | <0.01 | |||||||

| Gln27Glu Thr164Ile |

1042714 1800888 |

Bronchodilator responses to albuterol | NS | |||||

| Pulmonary function | Reduced | |||||||

| AGER | −429T > C | 1800625 | FEV1 Kulich CF-specific percentile z-score | 0.02 0.03 |

967 (Beucher et al., 2012) | |||

| KNoRMA | 0.03 | |||||||

| AGTR2 | 1403543 | FEV1 % pred (adjusted) | 1.61 × 10−5 | 1,978 (Wright et al., 2011) | 557 (Wright et al., 2011) | |||

| AHRR | 12188164 | FEV1% pred (adjusted) | 5.92 × 10−4 | 1,978 (Wright et al., 2011) | 557 (Wright et al., 2011) | |||

| C3 | 31778 G > A | 393770 | FEV1 % pred | 0.75 (0.05) | 755 (Park et al., 2011) | |||

| 4023 T > G | 11569393 | 0.66 (0.03) | ||||||

| 39718 G > A | 7257062 | 0.78 (0.52) | ||||||

| CD14 | −159 C > T | Pulmonary disease severity | No association | 105 (Faria et al., 2009) | ||||

| CDH8 | 11645366 | FEV1 % pred (adjusted) | 1.23 × 10−5 | 1,978 (Wright et al., 2011) | 557 (Wright et al., 2011) | |||

| CEACAM3 | 19q13 | 6508999–10414823 | Disease severity | 0.0469 | 37 nuclear families (Stanke et al., 2010) | |||

| CEACAM6 | 19q13 | 1549960–11548735 | Disease severity | 0.0106 | 37 nuclear families (Stanke et al., 2010) | |||

| CFB | 7680 A > G | 537160 | FEV1 % pred | 0.50 (0.83) | 755 (Park et al., 2011) | |||

| 10858 A > G | 2072633 | 0.68 (0.74) | ||||||

| CLCN2 | CLC-2 | −693 A > G | FEV1 % pred | 0.72 | 74 (Blaisdell et al., 2004) | |||

| 358 G > C | 0.32 | |||||||

| 427 A > G | 0.32 | |||||||

| 1089 T > C | 0.21 | |||||||

| 1909 G > C | 0.22 | |||||||

| DCTN4 | Any missense variant | 11954652 | Age at onset of chronic P. aeruginosa infection | 0.05 0.002 |

91 (Emond et al., 2012) | |||

| 35772018 | Age of first P. aeruginosa infection | 0.01 | 645 (Emond et al., 2012)⊙ | |||||

| Age at onset of chronic P. aeruginosa infection | 0.004 | 530○ | ||||||

| Age at onset of mucoid P. aeruginosa infection | 0.03 | |||||||

| Time from first detection of P. aeruginosa infection to mucoid P. aeruginosa | 0.01 | |||||||

| DEFB1 | Frequent polymorphisms | Age of first P. aeruginosa infection | No association | 210 (Vankeerberghen et al., 2005) | 62 (Segat et al., 2010) | 224 (Tesse et al., 2008) 92 (Crovella et al., 2011)+ | ||

| FEV1% | No association | |||||||

| DEFB4 | Genomic copy number (2–12) of repeat unit | Pulmonary disease (mean and current FEV1, mean and current FVC) | No association | 355 (Hollox et al., 2005) | ||||

| EDNRA | 6672 G > C | 5335 | Pulmonary function (FEV1) | 0.002 | 1,577 (Darrah et al., 2010) | |||

| EEA1 | 4760506 | FEV1 % pred (adjusted) | 6.77 × 10−6 | 1,978 (Wright et al., 2011) | 557 (Wright et al., 2011) | |||

| FCGR2 | FcγRII | R131H | Chronic P. aeruginosa colonization | 0.042 | 167 (De Rose et al., 2005) | |||

| FUT2 | G428A | 601338 | Impairment of lung function (FEV1) | 0.569 | 806 (Taylor-Cousar et al., 2009) | |||

| FUT3 | T59G | 28362459 | Impairment of lung function (FEV1) | 0.544 | 707 (Taylor-Cousar et al., 2009) | |||

| T202C | 812936 | 0.491 | ||||||

| C314T | 778986 | 0.615 | ||||||

| T1067A | 3894326 | 0.792 | ||||||

| GCLC | (GAG)n | FEV1 % pred | 0.097 | 440 (McKone et al., 2006) | ||||

| 0.001 (mild) | ||||||||

| 0.533 (severe) | ||||||||

| GSTM1 | GSTM1*0/ GSTM1*0 |

FEV1 % pred | 0.16 | 53 (Hull and Thomson, 1998) | 194 (Baranov et al., 1996) | 146 (Flamant et al., 2004) | ||

| Chrispin–Norman score | 0.02 | 808 (Drumm et al., 2005) | ||||||

| Shwachman score | 0.04 | 60 (Korytina et al., 2004) | ||||||

| Positive for P. aeruginosa | 0.12 | |||||||

| No. of ΔF508 homozygotes | 0.43 | |||||||

| GSTM3 | GSTM3*A | 1799735 | FEV1 | 0.01 | 146 (Flamant et al., 2004) | |||

| GSTM3*B | FVC | 0.002 | ||||||

| GSTP1 | 1375 A > G | 947894 | Spirometry | NS | 146 (Flamant et al., 2004) | 808 (Drumm et al., 2005) | 60 (Korytina et al., 2004) | |

| I105V | ||||||||

| GSTT1 | GSTT1*0/ | Spirometry | NS | 146 (Flamant et al., 2004) | ||||

| GSTT1*0 | ||||||||

| HFE | C282Y and/or H63D |

1800562 and/or 1799945 |

Positive for P. aeruginosa | 0.81 | 82 (Pratap et al., 2010) | |||

| FEV1% pred | 0.03 | |||||||

| FVC% pred | 0.02 | |||||||

| Annual change in FEV1% pred | 0.003 | |||||||

| Annual change in FVC% pred | 0.001 | |||||||

| HLA | DRA | 9268905 | FEV1 % pred (adjusted) | 1.42 × 10−5 | 1,978 (Wright et al., 2011) | 557 (Wright et al., 2011) | ||

| DR4 | Chronic P. aeruginosa colonization | ≤0.03 | 98 (Aron et al., 1999) | 72 (Laki et al., 2006) | ||||

| DR7/DQA*0201 | Chronic P. aeruginosa colonization | <0.03 | ||||||

| HMOX1 | 11354 A > G | 2071749 | FEV1 % pred | 0.01 (0.29) | 755 (Park et al., 2011) | |||

| 4613 A > T | 2071746 | 0.40 (0.03) | ||||||

| IFNG | IFNγ | +874 A > T | Age of first P. aeruginosa infection | No association | 261 (Arkwright et al., 2003) | |||

| Age at which FEV1 < 50% | 0.09 | |||||||

| Age of death | No association | |||||||

| IFRD1 | 57460 C > T | 7817 | Cross-sectional measures of lung function | 0.004 (0.0168)£ | 320 (Gu et al., 2009) | |||

| Longitudinal measures of lung function | 0.016 (0.0187)£ | |||||||

| FEV1% pred (adjusted) | No association | 1,978 (Wright et al., 2011) | ||||||

| 47556 G > T | 3807213 | Longitudinal measures of lung function | 0.080 | |||||

| 38923 C > T | 6968084 | Cross-sectional measures of lung function | 0.082 | |||||

| IL8 | 2227306 | Pulmonary disease severity | 0.19 | 737 | 385 (Hillian et al., 2008) | |||

| 2227307 | 0.04 | 727 | ||||||

| 2227543 | 0.06 | 732 | 329 (Corvol et al., 2008)♦ | |||||

| −251 A > T | 4073 | 0.07 | 733 (Hillian et al., 2008) | |||||

| IL-10 | −592 CC/- | 1800872 | Pulmonary function decline | No association | 261 (Arkwright et al., 2003) | |||

| −592 CC/TA | Age of first P. aeruginosa or B. cepacia infection | No association | ||||||

| Age of death | No association | |||||||

| −1082 G > A | 1800896 | Colonization with A. fumigatus | 0.06 (0.03)§ 0.02 (0.01)§ | 378 (Brouard et al., 2005) | 808 (Drumm et al., 2005) | |||

| Development of ABPA | No association | |||||||

| Colonization with P. aeruginosa | ||||||||

| KRT8/KRT18 | 1907671 | Disease severity | Associates | 49 (24 sib pairs) (Stanke et al., 2011) | ||||

| 4300473 | Associates | |||||||

| 8608 | Associates | |||||||

| 7952 T > C | 2035875 | 0.00131 | ||||||

| 1907671-4300473- 2035878-2035875 haplotype |

Disease severity | 0.0051 | ||||||

| 2638526 | Disease severity | NS | ||||||

| 2070876 | NS | |||||||

| KRT19 | c.90T > C | 11550883 | Effective specific airway resistance | 0.0093 | 95 (Gisler et al., 2012) | |||

| c.179G > C | 4602 | 0.0052 | ||||||

| 11550883-4602 haplotype |

0.0097 | |||||||

| MASP-2 | Exon 3 A > G, D120G |

72550870 | Pulmonary function | No association | 112 (Carlsson et al., 2005) | 109 (Olesen et al., 2006) | ||

| Need for transplantation | No association | |||||||

| Colonization with P. aeruginosa | 0.04 | |||||||

| Lung function in patients colonized with S. aureus | 0.04 | |||||||

| MBL2 | X1 – B (A > G) X1 – C (A > G) X1 – D (C > T) (A/A, A/O, O/O) −221 G > C (X/Y) |

1800450 1800451 5030737 7096206 |

FEV1% FVC% Age of onset of P. aeruginosa |

0.003 0.03 0.07 |

149 (Garred et al., 1999) | 164 (Gabolde et al., 1999) 179 (Yarden et al., 2004) 298 (Davies et al., 2004)Θ 47 (Trevisiol et al., 2005) 135 (Choi et al., 2006) 254 (Buranawuti et al., 2007) |

112 (Carlsson et al., 2005) 260 (Davies et al., 2004)Θ 47 (Trevisiol et al., 2005) 808 (Drumm et al., 2005) 105 (Faria et al., 2009) 788 (McDougal et al., 2010) 123 (Olesen et al., 2006) |

|

| Lung function | No association | 112 (Carlsson et al., 2005) | 105 (Faria et al., 2009) | |||||

| −550 G > C (H/L) | Colonization | No association | ||||||

| MIF | −794 presence of absence of 5-CATT | Colonization with P. aeruginosa | 0.004 | 167 (Plant et al., 2005) | ||||

| Colonization with S. aureus | 0.50 | |||||||

| Colonization with Candida | 0.36 | |||||||

| FEV1 ≥ 80% | 0.14 | |||||||

| NOS1 | (AAT)9–15 | Colonization with P. aeruginosa | 0.0358 | 75 (Grasemann et al., 2000) | 40 (Grasemann et al., 2002) | |||

| Mean FENO | 0.027 | |||||||

| (GT)18–36 | Colonization with A. fumigatus | 0.8505 0.025 |

59 (Texereau et al., 2004) | |||||

| 5 year decline of pulmonary function | ||||||||

| NOS3 | 894 G > T | FENO | 0.07 (0.02 in females) | 70 (Grasemann et al., 2003) | ||||

| FEV1 | 0.08 (in females) | |||||||

| Colonization with P. aeruginosa | <0.05 | |||||||

| T5220G | 1799983 | Impairment of lung function (FEV1) | 0.54 | 808 (Drumm et al., 2005) | ||||

| PPP2R1A | c.*465T > A | 2162779 | Functional residual capacity | 0.0033 | 95 (Gisler et al., 2012) | |||

| PPP2R4 | c.−185A > C | 3118625 | FEV1 | 0.0048 | 95 (Gisler et al., 2012) | |||

| Lung clearance index | 0.0059 | |||||||

| Effective specific airway resistance | 0.0064 | |||||||

| SCNN1B | ENaCβ | T313M 938 C > T G589S 1765 G > A |

Disease severity | 56 (Viel et al., 2008) | ||||

| SCNN1G | ENaCγ | L481G 1442 T > A V546I 1636 G > A |

5735–5723 haplotype | Disease severity | 56 (Viel et al., 2008) | |||

| SERPINA3 | ACT, A1ACT | T-15A | 4934 | FEV1% pred | 0.04 | 157 (Mahadeva et al., 2001) | ||

| Radiography score | 0.03 | |||||||

| SFTPA1 | 6A3 (and 6A3/1A1 haplotype) | FEV1% pred | 0.01 | 135 (Choi et al., 2006) | ||||

| DLCO | 0.10 | |||||||

| ATS score | 0.006 | |||||||

| AMA score | 0.02 | |||||||

| Dyspnea score | 0.20 | |||||||

| Physical score | 0.002 | |||||||

| Severity score | 0.005 | |||||||

| SFTPA2 | 1A1 (and 6A3/1A1 haplotype) | FEV1% pred | 0.009 | 135 (Choi et al., 2006) | ||||

| DLCO | 0.13 | |||||||

| ATS score | 0.007 | |||||||

| AMA score | 0.06 | |||||||

| Dyspnea score | 0.07 | |||||||

| Physical score | 0.12 | |||||||

| Severity score | 0.10 | |||||||

| SLC8A3 | 12883884 | FEV1% pred (adjusted) | 1.20 × 10−6 | 1,978 (Wright et al., 2011) | 557 (Wright et al., 2011) | |||

| SLC9A3 | 521096 C > T | 4957061 | Age of first P. aeruginosa infection | 0.02 | 1,004 | |||

| Decline of lung function (FEV1) | 0.05 | 752 (Dorfman et al., 2011) | ||||||

| SNAP23 | c.267-9T > C | 9302112 | FEF50 | 0.0088 | 95 (Gisler et al., 2012) | |||

| Functional residual capacity | 0.011 | |||||||

| Volume of trapped gas | 0.0043 | |||||||

| TGFB1 | codon 10 C29T | 1800470 | Age at which FEV1 < 50% Age at which FVC < 70% | <0.02 <0.005 |

171 (Arkwright et al., 2000)* | 261 (Arkwright et al., 2003) | 118 (Brazova et al., 2006) 1,978 (Wright et al., 2011) | |

| codon 25 G74C | 1800471 | Age at which FEV1 < 50% Age at which FVC < 70% | NS NS | 808 (Drumm et al., 2005)* | ||||

| C-509T | 1800469 | Impairment of lung function (FEV1) | 0.006 | 808 (Drumm et al., 2005) | 498 (Drumm et al., 2005) 329 (Corvol et al., 2008) 105 (Faria et al., 2009) 472 (Bremer et al., 2008) |

254 (Buranawuti et al., 2007) | ||

| TLR4 | D299G | 4986790 | Mean FEV1% pred | 0.55 | 100 (Urquhart et al., 2006) | |||

| Mean FVC% pred | 0.52 | |||||||

| Age of first P. aeruginosa infection | 0.78 | |||||||

| Chrispin–Norman X-ray score | 0.16 | |||||||

| 2688 G > A | 10759931 | Rate of change of FEV1% pred per year | 0.12 | |||||

| FEV1 % pred | 0.84 (0.55) | 755 (Park et al., 2011) | ||||||

| TLR5 | R392X | 5744168 | Mean FEV1 % pred | 0.77 | 2219 (Blohmke et al., 2010) | |||

| TNFA | TNFa | G-308A (TNF2) | 1800629 | Mean FEV1% pred Mean Chrispin–Norman X-ray score |

0.02 0.17 |

53 (Hull and Thomson, 1998) 180 (Yarden et al., 2005) |

261 (Arkwright et al., 2003) 180 (Yarden et al., 2005) 53 (Schmitt-Grohe et al., 2006) |

|

| Mean Shwachman score | 0.17 | |||||||

| No. positive for P. aeruginosa | 0.72 | 808 (Drumm et al., 2005) | ||||||

| C-851T | Mean FEV1% pred Age of first P. aeruginosa infection |

0.25 0.60 |

||||||

| G-238A | Mean FEV1% pred Age of first P. aeruginosa infection |

0.8 0.64 |

||||||

| +691g ins/del | Mean FEV1% pred Age of first P. aeruginosa infection |

0.008 0.018 |

||||||

| TNFR1 | TNFRSF1A | intron 1 haplotype | Disease severity | Associates | 37 sib pairs (Stanke et al., 2006) | |||

§The number in parenthesis indicates the p-value for the association found in F508del homozygotes.

Only multivariate p-values are reported. The number outside the parenthesis is the p-value for pediatrics and the number in parenthesis is the p-value for adults.

Only multivariate p-values are reported. The number outside the parenthesis is the p-value for pediatrics and the number in parenthesis is the p-value for adults.

⊙The association of missense variants with age at first P. aeruginosa-positive culture and age at onset of chronic P. aeruginosa was replicated in a population of only European American patients.

○The association of missense variants with age at first P. aeruginosa-positive culture and age at onset of chronic P. aeruginosa was replicated in a population excluding patients with non-European ancestry.

+Found that only the c.−20G > A SNP associated with disease severity.

£The number in parenthesis indicates the p-value after a Bonferroni correction.

♦Found that −251 TT, +396TT, and +781CC may be associated with an earlier occurrence of chronic P. aeruginosa colonization, which is an indicator of disease severity, but this was not examined in the study by Hillian et al. (2008).

ΘThe association of MBL2 deficiency alleles with indicators of pulmonary disease severity was replicated in a population of 298 adults, but refuted in a population of 260 children.

The Trevisiol et al. (2005) study replicated an association of MBL2 deficiency alleles with pulmonary function, but not with PA colonization.

The Trevisiol et al. (2005) study replicated an association of MBL2 deficiency alleles with pulmonary function, but not with PA colonization.

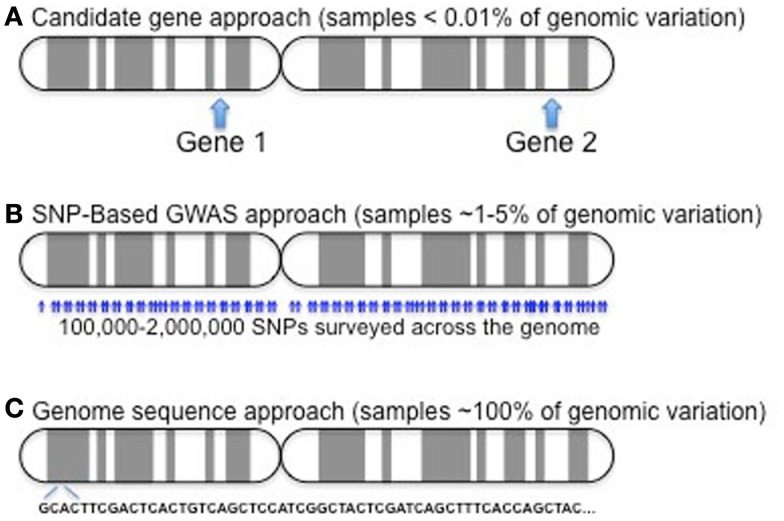

The vast majority of studies have been of the association design, predominantly due to the small number of families with multiple, affected children. These studies have evolved over time; cost and time restricted most early studies to screen for potential disease-modifying genes by candidate gene approaches with later studies utilizing array-based methods and soon whole-genome sequencing will be the state of the art. These three approaches are compared in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Candidate gene approaches (A) have only involved a few variants in one to several dozen genes. Given a genome of roughly 25,000 genes, this represents a very small sampling (∼0.01% or less). GWAS (B) samples a much larger component of the genome, probing more than 90% of the genes, but it still only examines less than 5% of the over 50 million reference SNPs (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/mailman/pipermail/dbsnp-announce/2012q2/000123.html) curated as of June, 2012. As costs come down, exome (not shown) and whole-genome sequencing (C) provide the potential to capture all variation in study subjects.

Phenotypic considerations

As lung disease is the major source of CF-related mortality, most studies have focused on some measure of lung function as a phenotype to examine for association. As most CF care centers carry out standard pulmonary function tests, spirometry has most commonly been used. Other tests may, in fact, be more specific for particular modifying functions, such as lung clearance index, but these are not as widely used and thus less practical for multi-center studies.

Candidate genes

Candidate genes are those suspected to have a role in some aspect of CF pathophysiology and variants in those genes are then tested for association with disease manifestations. Those traits may be represented by a continuum of values (lung disease severity, for example) or discrete traits, such as the occurrence of intestinal obstruction. Candidate gene selections for study involved many areas because of the complex pathophysiology of CF, including bacterial infections, inflammation, and lung remodeling/deterioration. This approach yielded multiple reports of putative modifiers of the CF pulmonary phenotype. For example, mannose-binding lectin (MBL), a gene involved in innate immunity, was one of the first potential modifier genes described. Low-expressing MBL alleles were found to associate with a more severe pulmonary disease course than those with higher expression (Garred et al., 1999). HLA haplotypes were also investigated as modifiers due to the role of the genes in this complex in innate defense and inflammation. Carriers of the HLA II DR7 haplotype were found to have a higher incidence of P. aeruginosa colonization (Aron et al., 1999).

Polymorphisms within cytokines and other inflammatory mediators were investigated as potential modifiers of CF pulmonary disease due to their role in immune response as well. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) is a pro-inflammatory cytokine that is stimulated by NF-κB as a first line of defense against infection. The minor allele of a TNFα promoter polymorphism associated with worse pulmonary function in a small set of CF patients (Hull and Thomson, 1998). Interestingly, the TNFα minor allele that associated with a worse CF prognosis was also associated with an increase in mRNA expression level when measured using a reporter construct (Wilson et al., 1992). Interleukin-10 (IL-10), an anti-inflammatory cytokine was also investigated. Like TNFα, an IL-10 promoter polymorphism was also associated with differences in IL-10 expression (Turner et al., 1997). In this case, the lower expressing IL-10 allele was associated with worse CF disease. These studies supported a model in which higher levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα, and lower levels of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 contribute to more severe CF lung disease.

Challenges of early candidate gene modifier studies

Early studies that attempted to identify potential modifiers were challenged by small numbers of study subjects. Typically, pulmonary function data using standard spirometry are not available on children younger than age 6, and multiple measures over time are needed to assess a subject’s trajectory, as an indicator of current and future disease severity. Nonetheless, numerous studies compared pulmonary function of subjects over a range of ages, statistically adjusting for age. Younger patients were included in order to maximize participation, but epidemiologic studies indicated that much of the pulmonary phenotypic variability was not present until after puberty (Zemel et al., 2000).

An additional constraint is that not all mutations in CFTR have the same consequences on protein function and thus it is likely to confound interpretation if CFTR genotype is not accounted for. Consequently, after limiting to patients with sufficient lung function measurements and comparable CFTR genotypes, the number of available subjects is low, making it unfeasible for any single center to carry out an association study that would have the statistical power to detect anything but a very major effect of a modifier gene.

Consortium approaches

The ability to effectively carry out genetic studies is limited by numbers of subjects. As a means to increase numbers, the European CF Twin and Sibling Study mentioned earlier was conceived and compared morphometric and pulmonary function indices of sib pairs. Using lung function measurements from patients in North America and Europe, this study was the first to compare lung function using a CF population for reference (Mekus et al., 2000).

Subsequently, the CF Gene Modifier Study (GMS) was conceived in 1999 to carry out a genetic study on a large group of patients for which longitudinal lung function data were available and genotype was restricted. In its inception, the study design was to use a candidate gene approach to search for potential genetic modifiers of CF pulmonary disease. The unique study design reduced genetic heterogeneity by using only patients who were homozygous for F508del (commonly referred to as ΔF508), and maximized the number of patients available by including patients from CF centers nationwide, comparing the most mild and most severe patients for differences in allele or genotype frequencies of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or other gene-associated variants as markers of potential modifier genes.

Phenotypic categories of disease severity were defined using a patient’s forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1), a pulmonary function index based on age, sex, and height, and used clinically to monitor CF disease progression and therapeutic efficacy. Subjects with FEV1 values in the upper quintile were classified as “mild” and those in the lower quintile as “severe.” Those subjects surviving beyond the age of 34 were classified as mild regardless of pulmonary function, as they represented the upper quintile of their birth cohort (Schluchter, 1992; Schluchter et al., 2002). DNA was obtained from these individuals and genotyped for a variety of variants in or near genes that were considered candidate modifiers.

In the initial candidate gene approach, 1,064 SNPs were tested in over 300 genes/gene regions that were chosen in the following ways: (1) they were SNPs that had previously been reported in the literature as associating with CF phenotype, (2) they were SNPs that were reportedly associated with similar pulmonary disease phenotypes, (3) they were genes that were known to play a key role in CF pathophysiology (Drumm et al., 2005).

Experience using this approach has shed light on the challenges involved in conducting modifier studies. Early studies struggled to achieve statistical power due to small sample sizes. Long and Langley (1999) calculated that the sample size must include at least 500 individuals in order to detect a causative polymorphism and for its association to be replicable. To accommodate the ability to replicate and maximize power, the GMS expanded to a North American Consortium that included a family-based genetic study at the Johns Hopkins University and a population-based study of Canadian CF patients being led by investigators at the University of Toronto and the Hospital for Sick Kids (Taylor et al., 2006). This consortium grew from the need to increase sample size and carry out replication studies and demonstrated its utility in a report that showed variants in the TGFB1 gene associate with pulmonary disease (Drumm et al., 2005) (discussed in more detail below).

The union of the three large studies provided a cohort of unprecedented size for studying modifiers of a single gene disorder, but also presented logistical issues due to the nature of the designs as each group had developed their own methods for assessing pulmonary phenotypes. Kulich et al. (2005) generated CF-specific reference equations for FEV1 that compare a CF subject’s lung function to CF subjects of the same age, sex, and height, as a more appropriate reference than the non-CF population and those values, adjusted for survival, were used to develop a phenotypic index that all three designs could incorporate.

The candidate gene approach showed the effectiveness of genetic studies, but a limitation is that it does not identify genetic locations other than those suspected to influence disease. That is, it will not detect modifying genes or pathways beyond those involved in our limited understanding of the disease. Understanding the functional effects of a modifier and its protein product fuel future studies to provide mechanistic insight of disease pathophysiology and how it might be dealt with (Cutting, 2010).

Associating Genes and Insight into their Modifying Mechanisms

One of the powerful attributes of genetics is that it allows one to identify clinically relevant genes, proteins, or pathways by virtue of the effect that variation in the gene produces on a clinical trait. However, the mechanisms by which genetic variation acts on the phenotype is not necessarily obvious. Thus, for any associating gene an obligatory step is to carry out functional studies to understand how it imparts its effect on disease presentation or outcome. Some examples are given below.

Associating genes: MBL

Mannose-binding lectin is a serum protein involved in innate immunity. MBL enhances phagocytosis of infectious organisms, especially during infancy, when adaptive immune response is immature (Eisen and Minchinton, 2003). Variant alleles that decrease MBL serum levels increase risk for many different infections (Garred et al., 1995, 1997; Summerfield et al., 1995, 1997) and have been shown to play a role in autoimmune diseases (Davies et al., 1995; Graudal et al., 1998). MBL has been suggested to regulate inflammatory responses, perhaps by delaying one of the first steps in inflammation or by reducing the levels of inflammatory cytokines (Jack et al., 2001). MBL is an attractive CF modifier candidate because it protects against infection and has some role in modulating inflammation.

Three amino acid substitutions in exon 1 (alleles B, C, and D) each contribute to decreased MBL plasma concentrations and are collectively referred to as 0, or null, alleles with the functional allele, containing none of the above variants, designated A. There are also variants with quantitative effects on mRNA expression, termed X, that also result in low MBL serum levels. Genotypes resulting in low MBL levels are designated low-producing or deficient alleles, but there are also genotype combinations associated with high and intermediate serum levels of MBL as well. Using the rationale that MBL protects against bacterial infection or somehow suppresses inflammation, then MBL deficiency alleles would be predicted to associate with a more severe CF lung disease.

In support of such a model, Garred et al. (1999) found that patients with higher expression MBL genotypes had a higher FEV1 and forced vital capacity (FVC). In other words, there was an additive effect of poor pulmonary function in the presence of an X allele. After further analysis, the cumulative adverse effects of low expression alleles were restricted to patients with chronic P. aeruginosa and were more pronounced in adults. MBL deficiency did not significantly associate with chronic colonization of P. aeruginosa. A study by Gabolde et al. found that cirrhosis of the liver was more common in CF patients carrying deficiency alleles, but other sources are conflicting about the association with CF liver disease (Gabolde et al., 2001; Bartlett et al., 2009; Tomaiuolo et al., 2009).

Several studies agree that MBL low expression alleles associate with lung function (Gabolde et al., 1999; Davies et al., 2004; Yarden et al., 2004; Trevisiol et al., 2005; Choi et al., 2006; Buranawuti et al., 2007; Dorfman et al., 2008), but there is no consensus as to whether this effect is only seen in patients colonized with P. aeruginosa, and whether a heterozygous genotype is sufficient to cause such impairment. Two studies found an association with chronic P. aeruginosa colonization (Trevisiol et al., 2005; McDougal et al., 2010), whereas others failed to detect an association between MBL alleles and colonization of any kind. Buranawuti et al. (2007) found that MBL high expression alleles predicted survival; the null genotype was underrepresented in adult populations and over represented in patients who died late in adolescence. This is consistent with multiple observations that the adverse effect of deficiency alleles is more pronounced in adults (Garred et al., 1999; Yarden et al., 2004; Buranawuti et al., 2007). In fact, a study by Davies et al. (2004) found no association between pulmonary function and MBL genotype in children. Despite replications, not all studies have detected associations between MBL alleles and lung disease severity (Carlsson et al., 2005; Drumm et al., 2005; Faria et al., 2009; McDougal et al., 2010).

Associating genes: TGFB1

As alluded to above, the first significant association identified by the consortium approach demonstrated that severity of pulmonary disease tracked with variants in the TGFB1 gene (Drumm et al., 2005). TGFB1 encodes transforming growth factor beta-1 (TGFβ1), a protein with complex function, involved in several cellular processes from differentiation and proliferation to innate immunity, and has been studied in relation to many disorders including Alzheimer’s disease, cancer, Marfan disease, and heart disease (Waltenberger et al., 1993; Yamamoto et al., 1993; Dickson et al., 2005; Brooke et al., 2008). Interest in investigating TGFβ1 as a potential modifier of CF pulmonary disease stemmed from both its biologic plausibility, and its identification as a modifier of asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (Pulleyn et al., 2001; Celedon et al., 2004; Silverman et al., 2004; Wu et al., 2004).

TGFβ1 is biologically relevant to CF for several reasons. Leukocytes secrete TGFβ1 in response to infectious agents. TGFβ1 participates in the immune process by regulating the production of cytokines, and is generally thought to be pro-inflammatory in nature (Omer et al., 2003). TGFβ1 also increases the formation of extracellular tissue during injury repair by increasing production of connective tissue by altered gene regulation (Bartram and Speer, 2004). Post-injury repair in the lung is a delicate balance; inadequate remodeling leads to poor wound healing, whereas excessive remodeling leads to pathogenic fibrosis and scarring. There is strong evidence to suggest that the difference between these outcomes is at least in part related to TGFβ1 expression levels (Bartram and Speer, 2004).

Variation in TGFβ1 has been shown to modify asthma and COPD. A variant in the promoter region (C-509T), thought to be associated with increased TGFβ1 expression, was studied as a potential contributor to asthma disease severity. In two separate studies homozygosity for the T allele (associated with increased TGFβ1 production) was found to be more common among severe asthmatics when compared to mild asthmatics or healthy controls (Pulleyn et al., 2001; Silverman et al., 2004). Variation in codon 10 was studied in patients with COPD. In this case, the allele associated with increased TGFβ1 production was found more commonly in control patients, suggesting a protective role for TGFβ1 in COPD (Wu et al., 2004). Contrasting with associations found in asthma patients, the T allele of -509 was more prevalent in those with mild COPD (Celedon et al., 2004).

The TGFβ1 variants that have been implicated in other airway diseases have become a source of interest in CF as well. A study by Arkwright et al. (2000) found that the T allele (high producer genotype) in codon 10 associated with more rapid deterioration in lung function, while the genotype at codon 25 did not correlate with survival or lung function. Another study confirmed the codon 10 association found by Arkwright but interestingly, it was the C allele (low producer genotype) that prevailed in severe patients (Drumm et al., 2005). This finding, replicated in a second population of 498 patients, is counterintuitive given the protective role of TGFβ1 in COPD. The same study, by Drumm et al. found that the -509 T allele also associated with a severe pulmonary phenotype, which is the same adverse effect seen in asthma populations. There have been several attempts to resolve these conflicting data (Arkwright et al., 2000, 2003; Drumm et al., 2005; Brazova et al., 2006; Buranawuti et al., 2007; Bremer et al., 2008; Corvol et al., 2008; Faria et al., 2009), but only one study has used a relatively large cohort to accommodate the statistical power needed. It found that a haplotype of a 3′ C allele (rs8179181), -509 C, and codon 10 T associated with improved lung function to a greater degree than any SNP alone (Bremer et al., 2008). It would appear from these studies that CF more closely mimics the type of disease seen in asthma and that the same polymorphisms may be protective or adverse, depending on the genetic and environmental context.

Associating genes: IFRD1

Gu et al. (2009) applied a novel strategy by pooling equal amounts of DNA from similarly affected subjects into “mild” and “severe” pools and examined 320 patients in the GMS population (160 with severe lung disease, 160 with mild lung disease) with much lower cost and time than the other efforts. By quantifying the signal for each allele (rather than a yes/no output) the genotyping arrays were used to estimate allele frequencies in the pools. Discordant allele frequencies were identified between the pools using this strategy (Gu et al., 2009) and indicated that alleles of IFRD1 may contribute to pulmonary disease severity. In a subsequent study, however, IFRD1 variants did not significantly associate with lung disease (Wright et al., 2011).

The IFRD1 protein acts in a histone deacetylase (HDAC)-dependent manner to regulate gene expression (Vietor et al., 2002) and the IFRD1 gene is up-regulated during cell differentiation and regeneration in response to stress (Vietor and Huber, 2007). Previous studies found high expression in human blood cells (SymAtlas, 2008) and Gu et al. found highest expression in neutrophils, where up-regulation occurs during the final differentiation steps (Ehrnhoefer, 2009; Gu et al., 2009). The authors suggested that IFRD1 modulates CF lung disease through the regulation of neutrophil effector function, but that other explanations, involving different cell types, should not be ignored.

Genome-Wide Association Studies

Although the cost of large-scale genotyping had fallen more than a 1000-fold since these studies were initiated, genome sequencing was still well out of range by price and feasibility. Thus, it became feasible to think about whole genome, or genome-wide association studies (GWAS). A GWAS would rapidly interrogate hundreds of thousands of SNPs for association in large populations (Manolio, 2010) without bias imposed by pre-existing models and provide the opportunity to identify novel genes, regulatory loci, and pathways not previously considered. The disadvantage to testing so many variants is that there are statistical penalties that increase as the number of comparisons rises, and thus power is a major limitation (Cutting, 2010). This is less of a concern if the effect of a locus is large, but as common population variants are being examined in these studies, it is likely that the effects of any one locus are not large, perhaps with each accounting for only a few percent of the variation, for example (Long and Langley, 1999). It is an important concept to understand that these studies are conceptually analogous to those designed to find disease-causing genes, which would have major effects if they do, in fact, cause disease.

GWAS-identified associations

In a combined GWAS and family-based (linkage) study, 3,467 CF patients were tested for associations between lung disease severity and more than half a million SNPs (Wright et al., 2011). To accommodate the various study designs and data acquisition protocols, yet another method to examine pulmonary function, with age-specific CF percentile values of FEV1 (Kulich et al., 2005; Taylor et al., 2011), was developed and which accounted for mortality and longitudinal changes. With this phenotype and over 500,000 common genetic variants to assess for association, two new loci, one on chromosome 11p13 and one on chromosome 20q13 were identified as having variants that associate with lung function in CF.

The region on chromosome 11p13 of most significant association lies between two annotated genes, APIP and EHF. APIP encodes Apaf-1-interacting protein and EHF is a member of the epithelial-specific Ets transcription factors, both of which provide interesting candidates as disease modifiers, but through very different models, all of which must yet be worked out. It is important to understand that despite the power of genetics to identify such disease-relevant locations in the genome, it does not provide information regarding mechanisms and these must be examined empirically. APIP, for example, has been shown to suppress apoptosis in the presence of hypoxia (Cho et al., 2007), a context experienced by CF tissues. At this point, it is not clear if the adverse allele provides less or greater activity than the protective allele, but one could construct models either way. For example, one hypothesis is that excessive anti-apoptotic activity, resulting from increased APIP, could prolong neutrophilic inflammation and therefore lead to more severe lung disease (Wright et al., 2011). Similarly, EHF is reported to serve as a regulator of epithelial cell differentiation under conditions of stress and inflammation (Tugores et al., 2001; Wright et al., 2011) and thus could be modeled to have very important effects during airway development or remodeling from disease-related damage. Finally, it must be considered that the modifying locus could be working at a distance, involving a regulatory site such as a transcriptional enhancer or non-coding RNA.

The other associating region on chromosome 20 was detected by linkage analysis and then refined by association. The linkage signal includes several genes including MC3R, encoding the melanocortin-3 receptor, CBLN4 encoding cerebellin-like 4, CASS4, encoding Crk-associated substrate scaffolding (CASS) 4, and AURKA, encoding Aurora kinase A (Wright et al., 2011). With the exception of MC3R, which is a receptor involved in metabolic control, models to explain the other candidates are not presently clear.

Certainly functional studies will help sort out which genes in these associating intervals are responsible for their modifying effects, but these findings illustrate both the power and some of the challenges of genetic studies. On one hand, the unbiased approach provides the opportunity to identify novel disease modulators, but on the other hand identifying the source of the modifying effect and the mechanisms through with it acts are challenging tasks.

The Impact of Disease-Modifying Genes

The implications of disease-modifying genes are multiple. First, understanding the genetic contribution to phenotypic variation has the potential to provide insight into prognosis. Second, understanding the mechanisms by which these genes and their alleles are exerting their effects will likely suggest new therapeutic approaches or ways to optimize existing ones. Third, it opens the door to personalized medicine, as a given patient’s treatment regimen could conceivably be developed around a genetic profile. Using inflammation as an example, one could imagine a patient whose modifier panel predicts a lessened inflammatory response, and another patient whose modifier panel predicts a heightened inflammatory response. Inflammation is part of the immune response that is necessary to fight infection, however its prolonged state in CF patients can cause lung damage. The patient with the heightened response may benefit from anti-inflammatory drugs earlier, and the patient with the reduced inflammatory response may benefit from increased antibiotic usage. Both are common treatments for CF, but they may be used more beneficially with the help of modifier identification and mechanistic understanding.

Summary

Cystic fibrosis is a simple, Mendelian disorder with complex clinical manifestations that are consequences of CFTR genotype, environmental factors (Boyle, 2007), and heterogeneity throughout the entire genome. The discovery of genetic modifiers may help account for the broad spectrum of disease severity observed in patients, especially those with the same CFTR genotype. Modifying loci identified thus far each appear to contribute only a small percentage to overall disease profile and thus it is likely the combination of these variants in different permutations shape an individual’s outcome, an outcome that is also significantly influenced by non-genetic factors, as well as the interaction of genetic and non-genetic factors. There are few genes whose modifying effects withstand the test of replication and further studies must elucidate the role of each one in CF. Additional research about gene-environment interactions and gene–gene interactions will certainly demonstrate how complex these genetic effects are. With the careful use of candidate gene approaches and now, genome-wide scans (and soon whole-genome sequencing), it is realistic to believe that modifiers of CF disease will be identified and from which interventions tailored around an individual’s genetic profile will be developed. This fine-tuning of therapeutic strategies could contribute to better quality of life and ultimately, improved survival in CF.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Footnotes

References

- Allen J. R., McCauley J. C., Selby A. M., Waters D. L., Gruca M. A., Baur L. A., et al. (2003). Differences in resting energy expenditure between male and female children with cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. 142, 15–19 10.1067/mpd.2003.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkwright P. D., Laurie S., Super M., Pravica V., Schwarz M. J., Webb A. K., et al. (2000). TGF-beta(1) genotype and accelerated decline in lung function of patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 55, 459–462 10.1136/thorax.55.6.459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arkwright P. D., Pravica V., Geraghty P. J., Super M., Webb A. K., Schwarz M., et al. (2003). End-organ dysfunction in cystic fibrosis: association with angiotensin I converting enzyme and cytokine gene polymorphisms. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 167, 384–389 10.1164/rccm.200204-364OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aron Y., Polla B. S., Bienvenu T., Dall’ava J., Dusser D., Hubert D. (1999). HLA class II polymorphism in cystic fibrosis. A possible modifier of pulmonary phenotype. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 159, 1464–1468 10.1164/ajrccm.159.5.9807046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baranov V. S., Ivaschenko T., Bakay B., Aseev M., Belotserkovskaya R., Baranova H., et al. (1996). Proportion of the GSTM1 0/0 genotype in some Slavic populations and its correlation with cystic fibrosis and some multifactorial diseases. Hum. Genet. 97, 516–520 10.1007/BF02267078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr H. L., Britton J., Smyth A. R., Fogarty A. W. (2011). Association between socioeconomic status, sex, and age at death from cystic fibrosis in England and Wales (1959 to 2008): cross sectional study. BMJ 343, d4662. 10.1136/bmj.d4662 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartlett J. R., Friedman K. J., Ling S. C., Pace R. G., Bell S. C., Bourke B., et al. (2009). Genetic modifiers of liver disease in cystic fibrosis. JAMA 302, 1076–1083 10.1001/jama.2009.1295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartram U., Speer C. P. (2004). The role of transforming growth factor beta in lung development and disease. Chest 125, 754–765 10.1378/chest.125.2.754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bear C. E., Li C. H., Kartner N., Bridges R. J., Jensen T. J., Ramjeesingh M., et al. (1992). Purification and functional reconstitution of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR). Cell 68, 809–818 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90155-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beucher J., Boelle P. Y., Busson P. F., Muselet-Charlier C., Clement A., Corvol H., et al. (2012). AGER-429T/C is associated with an increased lung disease severity in cystic fibrosis. PLoS ONE 7:e41913. 10.1371/journal.pone.0041913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaisdell C. J., Howard T. D., Stern A., Bamford P., Bleecker E. R., Stine O. C. (2004). CLC-2 single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) as potential modifiers of cystic fibrosis disease severity. BMC Med. Genet. 5:26. 10.1186/1471-2350-5-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blohmke C. J., Park J., Hirschfeld A. F., Victor R. E., Schneiderman J., Stefanowicz D., et al. (2010). TLR5 as an anti-inflammatory target and modifier gene in cystic fibrosis. J. Immunol. 185, 7731–7738 10.4049/jimmunol.1001513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyle M. P. (2007). Strategies for identifying modifier genes in cystic fibrosis. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 4, 52–57 10.1513/pats.200605-129JG [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brazova J., Sismova K., Vavrova V., Bartosova J., Macek M., Jr., Lauschman H., et al. (2006). Polymorphisms of TGF-beta1 in cystic fibrosis patients. Clin. Immunol. 121, 350–357 10.1016/j.clim.2006.08.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bremer L. A., Blackman S. M., Vanscoy L. L., McDougal K. E., Bowers A., Naughton K. M., et al. (2008). Interaction between a novel TGFB1 haplotype and CFTR genotype is associated with improved lung function in cystic fibrosis. Hum. Mol. Genet. 17, 2228–2237 10.1093/hmg/ddn123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke B. S., Habashi J. P., Judge D. P., Patel N., Loeys B., Dietz H. C., III. (2008). Angiotensin II blockade and aortic-root dilation in Marfan’s syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 358, 2787–2795 10.1056/NEJMoa0706585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouard J., Knauer N., Boelle P. Y., Corvol H., Henrion-Caude A., Flamant C., et al. (2005). Influence of interleukin-10 on Aspergillus fumigatus infection in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Infect. Dis. 191, 1988–1991 10.1086/429964 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buranawuti K., Boyle M. P., Cheng S., Steiner L. L., McDougal K., Fallin M. D., et al. (2007). Variants in mannose-binding lectin and tumour necrosis factor alpha affect survival in cystic fibrosis. J. Med. Genet. 44, 209–214 10.1136/jmg.2006.046318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buscher R., Eilmes K. J., Grasemann H., Torres B., Knauer N., Sroka K., et al. (2002). Beta2 adrenoceptor gene polymorphisms in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Pharmacogenetics 12, 347–353 10.1097/00008571-200207000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson M., Sjoholm A. G., Eriksson L., Thiel S., Jensenius J. C., Segelmark M., et al. (2005). Deficiency of the mannan-binding lectin pathway of complement and poor outcome in cystic fibrosis: bacterial colonization may be decisive for a relationship. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 139, 306–313 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02690.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celedon J. C., Lange C., Raby B. A., Litonjua A. A., Palmer L. J., DeMeo D. L., et al. (2004). The transforming growth factor-beta1 (TGFB1) gene is associated with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Hum. Mol. Genet. 13, 1649–1656 10.1093/hmg/ddh171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho D. H., Lee H. J., Kim H. J., Hong S. H., Pyo J. O., Cho C., et al. (2007). Suppression of hypoxic cell death by APIP-induced sustained activation of AKT and ERK1/2. Oncogene 26, 2809–2814 10.1038/sj.onc.1210080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi E. H., Ehrmantraut M., Foster C. B., Moss J., Chanock S. J. (2006). Association of common haplotypes of surfactant protein A1 and A2 (SFTPA1 and SFTPA2) genes with severity of lung disease in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 41, 255–262 10.1002/ppul.20361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey M., Edwards L., Levison H., Knowles M. (1997). Longitudinal analysis of pulmonary function decline in patients with cystic fibrosis. J. Pediatr. 131, 809–814 10.1016/S0022-3476(97)70025-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey M., Farewell V. (1996). Determinants of mortality from cystic fibrosis in Canada, 1970-1989. Am. J. Epidemiol. 143, 1007–1017 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corvol H., Beucher J., Boelle P. Y., Busson P. F., Muselet-Charlier C., Clement A., et al. (2012). Ancestral haplotype 8.1 and lung disease severity in European cystic fibrosis patients. J. Cyst. Fibros. 11, 63–67 10.1016/j.jcf.2011.09.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corvol H., Boelle P. Y., Brouard J., Knauer N., Chadelat K., Henrion-Caude A., et al. (2008). Genetic variations in inflammatory mediators influence lung disease progression in cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 43, 1224–1232 10.1002/ppul.20935 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney J. M., Plant B. J., Morgan K., Rendall J., Gallagher C., Ennis M., et al. (2006). Association of improved pulmonary phenotype in Irish cystic fibrosis patients with a 3′ enhancer polymorphism in alpha-1-antitrypsin. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 41, 584–591 10.1002/ppul.20416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crovella S., Segat L., Amato A., Athanasakis E., Bezzerri V., Braggion C., et al. (2011). A polymorphism in the 5′ UTR of the DEFB1 gene is associated with the lung phenotype in F508del homozygous Italian cystic fibrosis patients. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 49, 49–54 10.1515/cclm.2011.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutting G. R. (2010). Modifier genes in Mendelian disorders: the example of cystic fibrosis. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1214, 57–69 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05879.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Patient Registry. (2009). 2008 Annual Data Report, Bethesda: Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Darrah R., McKone E., O’Connor C., Rodgers C., Genatossio A., McNamara S., et al. (2010). EDNRA variants associate with smooth muscle mRNA levels, cell proliferation rates, and cystic fibrosis pulmonary disease severity. Physiol. Genomics 41, 71–77 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00185.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies E. J., Snowden N., Hillarby M. C., Carthy D., Grennan D. M., Thomson W., et al. (1995). Mannose-binding protein gene polymorphism in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 38, 110–114 10.1002/art.1780380117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies J. C., Turner M. W., Klein N. (2004). Impaired pulmonary status in cystic fibrosis adults with two mutated MBL-2 alleles. Eur. Respir. J. 24, 798–804 10.1183/09031936.04.00055404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis P. B. (1999). The gender gap in cystic fibrosis survival. J. Gend. Specif. Med. 2, 47–51 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis P. B., Drumm M., Konstan M. W. (1996). Cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 154, 1229–1256 10.1164/ajrccm.154.5.8912731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Rose V., Arduino C., Cappello N., Piana R., Salmin P., Bardessono M., et al. (2005). Fcgamma receptor IIA genotype and susceptibility to P. aeruginosa infection in patients with cystic fibrosis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 13, 96–101 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Demko C. A., Byard P. J., Davis P. B. (1995). Gender differences in cystic fibrosis: Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 48, 1041–1049 10.1016/0895-4356(94)00230-N [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di A., Brown M. E., Deriy L. V., Li C., Szeto F. L., Chen Y., et al. (2006). CFTR regulates phagosome acidification in macrophages and alters bactericidal activity. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 933–944 10.1038/ncb1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickson M. R., Perry R. T., Wiener H., Go R. C. (2005). Association studies of transforming growth factor-beta 1 and Alzheimer’s disease. Am. J. Med. Genet. B Neuropsychiatr. Genet. 139B, 38–41 10.1002/ajmg.b.30218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divangahi M., Balghi H., Danialou G., Comtois A. S., Demoule A., Ernest S., et al. (2009). Lack of CFTR in skeletal muscle predisposes to muscle wasting and diaphragm muscle pump failure in cystic fibrosis mice. PLoS Genet. 5:e1000586. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000586 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Y. J., Chao A. C., Kouyama K., Hsu Y. P., Bocian R. C., Moss R. B., et al. (1995). Activation of CFTR chloride current by nitric oxide in human T lymphocytes. EMBO J. 14, 2700–2707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman R., Sandford A., Taylor C., Huang B., Frangolias D., Wang Y., et al. (2008). Complex two-gene modulation of lung disease severity in children with cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 118, 1040–1049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorfman R., Taylor C., Lin F., Sun L., Sandford A., Pare P., et al. (2011). Modulatory effect of the SLC9A3 gene on susceptibility to infections and pulmonary function in children with cystic fibrosis. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 46, 385–392 10.1002/ppul.21372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doring G., Krogh-Johansen H., Weidinger S., Hoiby N. (1994). Allotypes of alpha 1-antitrypsin in patients with cystic fibrosis, homozygous and heterozygous for deltaF508. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 18, 3–7 10.1002/ppul.1950180104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drumm M. L., Konstan M. W., Schluchter M. D., Handler A., Pace R., Zou F., et al. (2005). Genetic modifiers of lung disease in cystic fibrosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 353, 1443–1453 10.1056/NEJMoa051469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrnhoefer D. E. (2009). IFRD1 modulates disease severity in cystic fibrosis through the regulation of neutrophil effector function. Clin. Genet. 76, 148–149 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2009.01247_2.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisen D. P., Minchinton R. M. (2003). Impact of mannose-binding lectin on susceptibility to infectious diseases. Clin. Infect. Dis. 37, 1496–1505 10.1086/379324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emond M. J., Louie T., Emerson J., Zhao W., Mathias R. A., Knowles M. R., et al. (2012). Exome sequencing of extreme phenotypes identifies DCTN4 as a modifier of chronic Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection in cystic fibrosis. Nat. Genet. 44, 886–889 10.1038/ng.2344 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faria E. J., Faria I. C., Ribeiro J. D., Ribeiro A. F., Hessel G., Bertuzzo C. S. (2009). Association of MBL2, TGF-beta1 and CD14 gene polymorphisms with lung disease severity in cystic fibrosis. J. Bras. Pneumol. 35, 334–342 10.1590/S1806-37132009000400007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flamant C., Henrion-Caude A., Boelle P. Y., Bremont F., Brouard J., Delaisi B., et al. (2004). Glutathione-S-transferase M1, M3, P1 and T1 polymorphisms and severity of lung disease in children with cystic fibrosis. Pharmacogenetics 14, 295–301 10.1097/00008571-200405000-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogarty A. W., Britton J., Clayton A., Smyth A. R. (2012). Are measures of body habitus associated with mortality in cystic fibrosis? Chest 142, 712–717 10.1378/chest.11-2124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangolias D. D., Ruan J., Wilcox P. J., Davidson A. G., Wong L. T., Berthiaume Y., et al. (2003). Alpha 1-antitrypsin deficiency alleles in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 29, 390–396 10.1165/rcmb.2002-0271OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabolde M., Guilloud-Bataille M., Feingold J., Besmond C. (1999). Association of variant alleles of mannose binding lectin with severity of pulmonary disease in cystic fibrosis: cohort study. BMJ 319, 1166–1167 10.1136/bmj.319.7218.1166a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabolde M., Hubert D., Guilloud-Bataille M., Lenaerts C., Feingold J., Besmond C. (2001). The mannose binding lectin gene influences the severity of chronic liver disease in cystic fibrosis. J. Med. Genet. 38, 310–311 10.1136/jmg.38.5.310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garred P., Madsen H. O., Balslev U., Hofmann B., Pedersen C., Gerstoft J., et al. (1997). Susceptibility to HIV infection and progression of AIDS in relation to variant alleles of mannose-binding lectin. Lancet 349, 236–240 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)08440-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garred P., Madsen H. O., Hofmann B., Svejgaard A. (1995). Increased frequency of homozygosity of abnormal mannan-binding-protein alleles in patients with suspected immunodeficiency. Lancet 346, 941–943 10.1016/S0140-6736(95)91559-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garred P., Pressler T., Madsen H. O., Frederiksen B., Svejgaard A., Hoiby N., et al. (1999). Association of mannose-binding lectin gene heterogeneity with severity of lung disease and survival in cystic fibrosis. J. Clin. Invest. 104, 431–437 10.1172/JCI6861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gisler F. M., von Kanel T., Kraemer R., Schaller A., Gallati S. (2012). Identification of SNPs in the cystic fibrosis interactome influencing pulmonary progression in cystic fibrosis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 21, 397–403 10.1038/ejhg.2012.181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasemann H., Knauer N., Buscher R., Hubner K., Drazen J. M., Ratjen F. (2000). Airway nitric oxide levels in cystic fibrosis patients are related to a polymorphism in the neuronal nitric oxide synthase gene. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 162, 2172–2176 10.1164/ajrccm.162.6.2003106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasemann H., Storm van’s Gravesande K., Buscher R., Knauer N., Silverman E. S., Palmer L. J., et al. (2003). Endothelial nitric oxide synthase variants in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 167, 390–394 10.1164/rccm.200202-155OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grasemann H., Storm van’s Gravesande K., Gartig S., Kirsch M., Buscher R., Drazen J. M., et al. (2002). Nasal nitric oxide levels in cystic fibrosis patients are associated with a neuronal NO synthase (NOS1) gene polymorphism. Nitric Oxide 6, 236–241 10.1006/niox.2001.0408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graudal N. A., Homann C., Madsen H. O., Svejgaard A., Jurik A. G., Graudal H. K., et al. (1998). Mannan binding lectin in rheumatoid arthritis. A longitudinal study. J. Rheumatol. 25, 629–635 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu Y., Harley I. T., Henderson L. B., Aronow B. J., Vietor I., Huber L. A., et al. (2009). Identification of IFRD1 as a modifier gene for cystic fibrosis lung disease. Nature 458, 1039–1042 10.1038/nature07811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry M. T., Cave S., Rendall J., O’Connor C. M., Morgan K., FitzGerald M. X., et al. (2001). An alpha1-antitrypsin enhancer polymorphism is a genetic modifier of pulmonary outcome in cystic fibrosis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 9, 273–278 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillian A. D., Londono D., Dunn J. M., Goddard K. A., Pace R. G., Knowles M. R., et al. (2008). Modulation of cystic fibrosis lung disease by variants in interleukin-8. Genes Immun. 9, 501–508 10.1038/gene.2008.42 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollox E. J., Davies J., Griesenbach U., Burgess J., Alton E. W., Armour J. A. (2005). Beta-defensin genomic copy number is not a modifier locus for cystic fibrosis. J. Negat. Results Biomed. 4, 9. 10.1186/1477-5751-4-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hull J., Thomson A. H. (1998). Contribution of genetic factors other than CFTR to disease severity in cystic fibrosis. Thorax 53, 1018–1021 10.1136/thx.53.12.1018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jack D. L., Read R. C., Tenner A. J., Frosch M., Turner M. W., Klein N. J. (2001). Mannose-binding lectin regulates the inflammatory response of human professional phagocytes to Neisseria meningitidis serogroup B. J. Infect. Dis. 184, 1152–1162 10.1086/323803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerem E., Corey M., Kerem B. S., Rommens J., Markiewicz D., Levison H., et al. (1990a). The relation between genotype and phenotype in cystic fibrosis – analysis of the most common mutation (delta F508). N. Engl. J. Med. 323, 1517–1522 10.1056/NEJM199011293232203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerem E., Corey M., Gold R., Levison H. (1990b). Pulmonary function and clinical course in patients with cystic fibrosis after pulmonary colonization with Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Pediatr. 116, 714–719 10.1016/S0022-3476(05)82653-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korytina G. F., Iaibaeva D. G., Viktorova T. V. (2004). Polymorphism of glutathione-S-transferase M1 and P1 genes in patients with cystic fibrosis and chronic respiratory tract diseases. Genetika 40, 401–408 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krauss R. D., Berta G., Rado T. A., Bubien J. K. (1992). Antisense oligonucleotides to CFTR confer a cystic fibrosis phenotype on B lymphocytes. Am. J. Physiol. 263, C1147–C1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulich M., Rosenfeld M., Campbell J., Kronmal R., Gibson R. L., Goss C. H., et al. (2005). Disease-specific reference equations for lung function in patients with cystic fibrosis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 172, 885–891 10.1164/rccm.200410-1335OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laki J., Laki I., Nemeth K., Ujhelyi R., Bede O., Endreffy E., et al. (2006). The 8.1 ancestral MHC haplotype is associated with delayed onset of colonization in cystic fibrosis. Int. Immunol. 18, 1585–1590 10.1093/intimm/dxl091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamhonwah A. M., Bear C. E., Huan L. J., Kim Chiaw P., Ackerley C. A., Tein I. (2010). Cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator in human muscle: dysfunction causes abnormal metabolic recovery in exercise. Ann. Neurol. 67, 802–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long A. D., Langley C. H. (1999). The power of association studies to detect the contribution of candidate genetic loci to variation in complex traits. Genome Res. 9, 720–731 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mafficini A., Ortombina M., Sermet-Gaudelius I., Lebecque P., Leal T., Iansa P., et al. (2011). Impact of polymorphism of multidrug resistance-associated protein 1 (ABCC1) gene on the severity of cystic fibrosis. J. Cyst. Fibros. 10, 228–233 10.1016/j.jcf.2010.10.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadeva R., Sharples L., Ross-Russell R. I., Webb A. K., Bilton D., Lomas D. A. (2001). Association of alpha(1)-antichymotrypsin deficiency with milder lung disease in patients with cystic fibrosis. Thorax 56, 53–58 10.1136/thorax.56.1.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadeva R., Westerbeek R. C., Perry D. J., Lovegrove J. U., Whitehouse D. B., Carroll N. R., et al. (1998a). Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency alleles and the Taq-I G→A allele in cystic fibrosis lung disease. Eur. Respir. J. 11, 873–879 10.1183/09031936.98.11040873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahadeva R., Stewart S., Bilton D., Lomas D. A. (1998b). Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency alleles and severe cystic fibrosis lung disease. Thorax 53, 1022–1024 10.1136/thx.53.6.501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manolio T. A. (2010). Genomewide association studies and assessment of the risk of disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 363, 166–176 10.1056/NEJMra0905980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald T. V., Nghiem P. T., Gardner P., Martens C. L. (1992). Human lymphocytes transcribe the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator gene and exhibit CF-defective cAMP-regulated chloride current. J. Biol. Chem. 267, 3242–3248 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDougal K. E., Green D. M., Vanscoy L. L., Fallin M. D., Grow M., Cheng S., et al. (2010). Use of a modeling framework to evaluate the effect of a modifier gene (MBL2) on variation in cystic fibrosis. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 18, 680–684 10.1038/ejhg.2009.226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKone E. F., Shao J., Frangolias D. D., Keener C. L., Shephard C. A., Farin F. M., et al. (2006). Variants in the glutamate-cysteine-ligase gene are associated with cystic fibrosis lung disease. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 174, 415–419 10.1164/rccm.200508-1281OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mekus F., Ballmann M., Bronsveld I., Bijman J., Veeze H., Tummler B. (2000). Categories of deltaF508 homozygous cystic fibrosis twin and sibling pairs with distinct phenotypic characteristics. Twin Res. 3, 277–293 10.1375/136905200320565256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer P., Braun A., Roscher A. A. (2002). Analysis of the two common alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency alleles PiMS and PiMZ as modifiers of Pseudomonas aeruginosa susceptibility in cystic fibrosis. Clin. Genet. 62, 325–327 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2002.620413.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milla C. E., Billings J., Moran A. (2005). Diabetes is associated with dramatically decreased survival in female but not male subjects with cystic fibrosis. Diabetes Care 28, 2141–2144 10.2337/diacare.28.9.2141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss R. B., Hsu Y. P., Olds L. (2000). Cytokine dysregulation in activated cystic fibrosis (CF) peripheral lymphocytes. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 120, 518–525 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2000.01232.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor G. T., Quinton H. B., Kneeland T., Kahn R., Lever T., Maddock J., et al. (2003). Median household income and mortality rate in cystic fibrosis. Pediatrics 111, e333–e339 10.1542/peds.111.2.e109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]