Abstract

John Alexander Lindsay was born at Fintona, county Tyrone in 1856, and at the age of 23 he graduated in medicine at the Royal University of Ireland. After two years in London and Europe he returned to Belfast to join the staff at the Royal Victoria Hospital and in 1899 he was appointed to the professorship of medicine. He was valued by the students for his clarity and by his colleagues for his many extracurricular contributions to the medical profession in the positions entrusted to him. He published monographs on Diseases of the Lungs, and the Climatic Treatment of Consumption, but his later Medical Axioms show his deep appreciation of studied clinical observation. Although practice was changing in the new century Lindsay displayed an ability to change with the new requirements, as evidenced by his lecture on electrocardiography as president of the section of medicine of the Royal Academy of Medicine in Ireland in 1915. He was impressed by the way the string galvanometer changed attention from stenosis and incompetence of the valves to the cardiac musculature, but rightly suspected that there was more to be told about the state of the myocardium than Einthoven's three leads revealed. His death occurred in Belfast in 1931.

Career

The original James Lindsay emigrated from Ayrshire in 1678 and farmed between Derry and St. Johnstone before his family settled on an extensive farm at Lisnacrieve, one Irish mile south-west of Fintona, county Tyrone, in the middle of the eighteenth century. Spinning was at that time a cottage industry, and in July 1822 his descendants, John and David, established the ‘Woollen, Linen and Haberdashery Warehouse’ in Donegall Place, Belfast. Their business thrived and in October 1858 they opened a retail business at the Ulster Arcade specifically built for the purpose. James Alexander Lindsay, the son of David the successful Belfast textile merchant anxious that his offspring be born at the family homestead, first saw the light at Lisnacrieve House, Fintona, on 20 June 1858.1 He was educated at the Royal Academical Institution, Methodist College and Queen's College Belfast, graduating BA in 1877, MA in ancient classics in 1878 and MD, MCh in the Royal University of Ireland in 1882. After two years in the clinics of London, Paris and Vienna he returned to Belfast where he was appointed assistant physician at the Royal Victoria Hospital in 1884 and full physician in 1888 until 1921. In 1899 he succeeded James Cuming in the chair of medicine, and held that position until 1923, the year he published his Medical Axioms, Aphorisms, and Clinical Memoranda. He took the membership and was elected a fellow of the Royal College of Physicians of London in 1903 where he delivered the Bradshaw Lectures in 1909 on the evolutionary relationships between structure, disease and race in ‘Darwinism and medicine'.2

His duties as a teacher he took seriously, and ‘as a clinical teacher he shone with a rare ability; his clearness of vision and crystal clarity of diction rendered his instruction of rare quality and inestimable worth to the student'. Widely travelled he was of broad scholarly distinction for his reading included philosophy, religion and the classics as well as medicine. Many important positions were entrusted to him in the medical organisations he joined; these included the Ulster Medical Society, the Royal Academy of Medicine in Ireland, the Association of Physicians of Great Britain and Ireland and the Aristotelian Society. He served on the central council of the British Medical Association from 1896 to 1899, was president of the Ulster Branch in 1905, and was president of the Section of Medicine at the Annual Meeting in 1909 when the Queen's University celebrated the centenary of the medical school. Even in retirement he had the development of the Belfast medicine at heart: his efforts contributed to the amalgamation of the Royal Maternity Hospital and the Royal Victoria Hospital. For many years he provided editorial assistance to the British Medical Journal and The Lancet. His death occurred on 14 December 1931 in Belfast from cerebral thrombosis. x 4

In his history of the Royal Victoria Hospital, Richard Clarke records that James Lindsay was the first house physician appointed at the Belfast Royal Hospital, where he became Assistant Physician in 1883 and Attending Physician 1888 (Fig 1). He belonged to the school of physicians who concentrated on accurate diagnosis, and that with the aid of his own senses and acumen, but had little interest in medical treatment; he never took up such artificial aids as electrocardiography, although it has to be said in his defence that he learned how to identify the waves defined by Einthoven. This pedantic approach was crystallised in the instruction cards of technique for examination of patients that he published. His lectures also were precise and old-fashioned, delivered at dictation speed throughout, to provide notes for future reference, as was common until good textbooks became more freely available in the 1950s. Lindsay was succeeded in the chair of medicine by William WD Thomson (8.9.1885-26.11.1950) the last of the old-style professors of medicine, who made their mark not by research but by bed-side teaching, and indeed he was the last of the part-time professors of medicine. 4

Fig 1.

James Alexander Lindsay

Electrocardiography in belfast (1915)

As President of the Section of Medicine of the Royal Academy of Medicine in Ireland he read a paper on ‘Some observations upon the electrocardiograph, with notes on cases’ on 12 November 1915 in The Royal College of Physicians in Dublin.7 Einthoven (1860-1927) around 1905 handed over construction of his string galvanometer to the Cambridge Instrument Company whose cardiographs were delivered to physiological laboratories between 1905 and 1907; this company was preferred by the inventor over Edelmann and Sons of Munich who had manufactured the earlier instruments for him.8

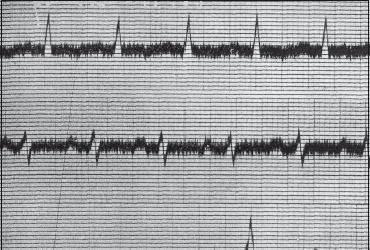

He began his paper by introducing the history and design of Einthoven's string galvanometer, admitting that his ‘own experience with the instrument’ was limited to little more than a year. The Dutchman's invention is ‘sufficiently delicate to give adequate results ... When we examine the photographs of the string movements we observe a series of waves, ‘curves’ or ‘deflections’ which are repeated regularly, each series representing the cardiac complex with the intervening pauses'. (Figures 2 and 3). Without identifying them by name Lindsay paid tribute to Mackenzie and Einthoven:

Fig 2.

Leads I, II and III recorded by the string galvanometer. Spread of electrical excitation into ventricular muscle generates the QRS complex. Left ventricular preponderance is indicated by high R in Lead 1 and deep S in Lead III.

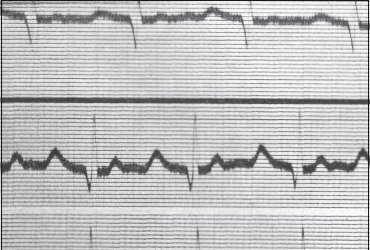

Figure 3.

Mitral stenosis eases the load on the left ventricle and increases the work of the right ventricle. A deep S in Lead I and a high R in Lead III typify right ventricular hypertrophy.

'amongst the recent advances in medicine an important place must be assigned to the development of instrumental methods of observation in connection with the heart in health and disease ... the polygraph and the electrocardiograph add new important facts ... By their instrumentality the heart writes its own message, and the cardiac script can be interpreted ... we get the phenomena of disease at first hand: observation is made for us; our task is that of interpretation. ... In Belfast we are much indebted to Dr. Ilwaine and Professor Milroy.7

Thomas Hugh Milroy (1869-1950) was appointed professor of physiology in 1902. Dr. Ilwaine was in fact the recently appointed assistant physician John Elder MacIlwaine (1874-1930), an electrocardiographic enthusiast who persuaded James Mackie (1864-1943) of the Albert Foundry to purchase the Einthoven machine; in 1921 he was promoted attending physician and succeeded to the chair of materia medica held by Sir William Whitla (1851-1933).6

Further, Lindsay stated openly that he was also much indebted for a large part of his information to the writings of [Thomas] Lewis (1881-1945)7, who says ‘ The records from patients are clear messages writ by the hand of disease, permanent and authentic documents, which silence dogma.'. 9 Lindsay concluded his paper

The electrocardiograph is a marvel of ingenuity ... [that] has compelled us to think out old problems from a new angle. It has helped us to fix attention upon the cardiac musculature, rather than on the cardiac valves: But I should be the first to deprecate any exclusive reliance upon instrumental methods in the study of heart disease. The final test of cardiac sufficiency or insufficiency is the appeal to experience. Clinical observation in the broad sense of the term is in the long run more trustworthy than any form of mechanical or instrumental record, but the two should supplement, not supplant, each other.7

Professor Thompson (c1860-1918), professor of the institutes of medicine at Dublin University who had been Dunville professor of physiology at Queen's College Belfast from 1893-1902 , inquired whether the large number of tracings shown were the work of the President, who answered adroitly that ‘all had been obtained in the Victoria Hospital, Belfast'. He was not a devotee of instrumental methods, but they eliminated ‘the personal factor’ - a most important quality.7

As Author

Robert Koch's identification of the causative organism, though a hugely important landmark did not lead immediately to any change in the treatment of consumption, and Lindsay, seeing cases so frequently, tried to assess the value of the highly popular - and expensive, approach in The Climatic Treatment of Consumption (1887) even travelling twice to New Zealand. Of the Home Sanatoria he decided ‘ Queenstown (now Cobh) and Glengarriff (both in county Cork) are well worth the attention of Irish patients who prefer to remain in their own country. Rostrevor can only be recommended to those living in the neighbourhood who are unwilling to undertake the long journey necessary to reach more desirable sanatoria. 10. Tuberculosis was still rife in Ireland in 1906 and was given one third of the volume when he prepared the second edition of his Lectures on Diseases of the Lungs. The causes and management of haemoptysis, not surprisingly, were considered in detail. He had to admit that ‘most writers affirm the existence of ‘vicarious’ haemoptysis’ but he was doubtful if a true haemoptysis occurs in, for example, patients suffering from amenorrhoea. u

In his answer to professor Thompson's loaded question Lindsay admitted that while he knew his Ps and Qs and the ReST of the trace made with the Einthoven string galvanometer, he was not an electrocardiologist. Of the three categories of physicians recognised by Claude Bernard (1813-1878), Hippocratic, empiric and experimental, he saw himself among the Hippocratists: ‘For their part, the Hippocratic physicians are satisfied when they have succeeded in clearly describing a disease in its source, in learning and foreseeing its various favourable or direful endings by exact signs, so as to be able to intervene, if necessary, to help nature and to guide itto a happy ending'.12 This helps to explain Lindsay's reverence for aphorisms, pithy generalisations embodying clinical wisdom and proverbs, and his practice of distributing aide memoir cards mentioned by Clarke. The experimental enterprise envisaged by Bernard has been so successful that it has led to a flowering of investigative medicine that had so overgrown and outdated clinical aphorisms that it behoves us to recall the wisdom of the ancients that so enthralled Lindsay, (who added his own after making the collection).

Lindsay's Collected Aphorisms (1923)13

Hippocrates (c470- c400)

Life is short, the Art is long, Occasion sudden, Judgment difficult.

The physician should possess the following qualities: learning, wisdom, humanity, probity.

The nature of the body can only be understood as a whole.

To the love of his profession the physician should add a love of humanity.

Whoever is desirous of pursuing his medical studies on a right plan must pay a good deal of attention to the different seasons of the year and their respective influence.

Neither hunger nor anxiety, nor anything that exceeds the natural bounds, can be good and healthful.

Old men easily endure fasting; those who are middle-aged not so well; young men worse than these; and children worst of all, especially those who are of a more lively spirit.

Greek Medicine in Rome

Physic is not always good for the sick, but it is always hurtful to the healthy. (Cicero)

Hippocrates said he must needs succeed well in cures that considers and understands such things as are common and proper. (Celsus)

We ought not to be ignorant that the same remedies are not good for all. (Celsus)

Laziness slackens and dulls the body, but labour strengthens and makes it firm. The former hastens old age; the other prolongs youth. (Celsus)

Idleness and luxury first corrupted men's bodies in Greece, and afterwards afflicted them in Rome. (Celsus)

Rest and abstinence are the best of all remedies, and abstinence alone cures without any danger. (Celsus)

Death is intimated when the patient lies back with knees drawn up [together]. (Galen)

It is a distinguishing human trait to supplicate the gods for good health. (Galen)

The art of healing depends on local conditions / the physician is nature's assistant. (Galen)

The best physician is also a philosopher. (Galen)

Renaissance

If your doctors fail, let these three be your physician: a cheerful mind, rest, and well regulated diet. (Motto of School of Salerno).

Wisdom is the daughter of experience. (Leonardo) The sick should be the doctor's books. (Paracelsus).

Tis a patient and quiet mind (I say it again and again) gives true peace and content. (Cardan)

I dressed him; God cured him. (Paré)

Discuss the coming on of years, and think not to do the same things still; for age will not be denied. (Bacon)

Experience is the mistress of doctors. (Sydenham). Cleanliness is conducive to elegant health. (Sydenham).

Let me be sick myself if sometimes the malady of my patient be not a disease to me (Sir Thomas Browne).

The Clinicians’ century

The whole art of medicine is in observation. (Louis)

Relief should be the aim of the physician when it is not possible to cure. (Trousseau).

The trouble with most doctors is, not that they don't know enough but that they don't see enough. (Corrigan)

Never look surprised at anything. (Syme). Never ask the same question twice. (Syme). The speed of life is not the same for all. (Paget).

Living to old age ‘goes in families'; and so does dying before old age. (Paget)

I am sure of this: that as the justly successful members of our profession grow older and probably wiser, they more and more guide themselves by the study of their patient's constitution, learning more of family histories, and detecting constitutional diseases more skilfully in signs which to others seem trivial. (Paget).

Health is that state of mind in which the body is not consciously present to us; the state in which work is easy and duty not too great a trial; the state in which it is a joy to see, to think, to feel to be. (Clark).

A sane mind consists in a good digestion of experience. (Allbutt).

The best physician is the most conscious of the limitations of his art. (Jowett).

The first qualification for a physician is hopefulness. (Little).

Every medical student should remember that his end is not to make a chemist, or a physiologist, or an anatomist, but to learn how to recognise and treat disease, to become a practical physician. (Osler).

I hold that no man is fit to teach medical students unless he himself is a qualified practitioner and maintains his knowledge in a state which would permit him to ply his real vocation. (Keith).

In acute affections we concentrate our attention upon the diseased organ, while in chronic affections we keep the general condition of the patient more in view. (Van Noorden)

Lindsay the Aphorist / Lindsay's own Aphorisms

And having surveyed the sages he distils wisdom from his own experience (p 48 f)13:

Medicine is an art, but it is an art which is always trying to become a science.

Attack disease at its beginning - obsta principiis

Few studies are more instructive, more full of warning, or more generally neglected than the study of the history of medicine.

Nature is a good physician but a bad surgeon.

Extreme specialism was one of the causes of the decay of medicine in Ancient Egypt.

Think of common diseases first.

'Queer cases’ are usually abnormal types of common conditions.

In searching for the obscure, do not overlook the obvious.

Remember that many symptoms are part of Nature's defensive mechanisms.

In dealing with disease, think of disordered function as much as of damaged structure

It is rarely permissible to base a diagnosis upon a single sign.

For one mistake made for not knowing, ten mistakes are made for not looking.

Weigh your patients, and attach much value to the indications of the weighing machine.

Vulnerability to disease may be local rather than general - i.e. it may be due to some structural defect rather than to general constitutional weakness.

There are few things more difficult than to establish a fact in therapeutics. The post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy is rampant. The history of medicine is full of the records of fictitious cures.

Tell the elderly not to forget Anno Domini. For many patients hope is the best medicine.

At the bedside a great deal too much optimism is a venial error compared with a little too much pessimism.

Get a clear answer from every patient to three fundamental questions:

What do you complain of,

How long have you been ill,

How did it begin?

In every case of serious illness someone, not necessarily the patient, should know the truth.

When disease takes an unexpected turn, or treatment after due trial proves ineffective, reconsider the diagnosis.

Always ask the question, How is the patient reacting to his malady?

Every disease has a psychological as well as a pathological aspect. The patient's mentality counts for much in his response to treatment.

The doctor ‘suggests’ even when he makes no conscious effort at suggestion..

A Closing Warning on Axioms

'Gifted with a mind at once scholarly and judicial, Lindsay believed that the teacher's function was to instruct the student how to learn and how to think’ 2, and his axioms and aphorisms n were intended as clinical memoranda to help the practitioner in making diagnostic decisions in his daily encounters with illness. A man of such gifted clinical acumen cannot have seen them as infallible guides: axioms are subject to the universal law that no rule is free from exceptions, as his younger contemporaries were aware. In a lecture on hyperthyroidism Thomas Gillman Moorhead (1878-1960) reminded his listeners that ‘Graves's disease has been defined as one from which no one can recover, and of which no one ever dies', and remarked ‘The aphorism is useful, though, like most aphorisms it overstates the facts'.14 A few years later, in an international review of medical proverbs, aphorisms and epigrams Fielding H Garrison (1890-1935) warned readers: ‘Apart from the larger aspirations and ideals of great physicians, aphorisms about medicine are to be approached with extreme caution and are best taken in small doses. Science cannot be reduced to a pocket formula'. And he concludes that there is the wisdom of deep feeling in the monody of the Irish poet:

-

The silliest charm gives more comfort to those in sorrow and pain,

Than they will ever get from the knowledge that proves it foolish and vain;

For we know not where we come from and we know not whither we go,

And the best of all our knowledge is how little we can know. 15

The (unidentified) poet was William Edward Hartpole Lecky (1831-1903) whose Friendship and other poems (1859) was so poorly received that he transferred his allegiance to Clio with spectacular success in Dublin University.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Robert Mills, Librarian RCPI and Dr. Ted Keelan, cardiologist, Mater Misericordiae Hospital, Dublin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lindsay JC, Lindsay JA. Belfast: William Strain and Sons; 1884. The Lindsay Memoirs: A a record of the Lisnacrieve and Belfast Lindsay family during the last two hundred years. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown GH. Vol. 4. London: Roy Coll Physician; 1965. Munk’s Roll; pp. 452–3. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obituary; James Alexander Lindsay. Lancet. 1931;5652:1435–6. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Obituary: J A Lindsay. Brit Med J. 1931;2(3703):1201–02. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McAfee CH. The history of the Belfast School of Obstetrics. Ulst Medx J. 1942;11(1):20–50. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clarke RS. Belfast: The Blackstaff Press; 1997. The Royal Victoria Hospital Belfast: a history 1797-1997; p. 42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lindsay JA. Some observations upon the electrocardiograph, with notes of cases. Dublin J Med Sci. 1916;141(2):130–8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frank RG. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1988. The tell-tale heart: physiological instruments, graphic methods, and clinical hopes 1854-1914, In: Coleman WL, Holmes FL, editors. The investigative enterprise; pp. 211–90. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis T. London: Macmillan; 1913. Clinical electrocardiography. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lindsay JA. London: Macmillan; 1887. The climatic treatment of consumption; pp. p. viii, x, 184–94, 228. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lindsay JA. London: Baillière Tindall & Cox; 1906. Lectures on diseases of the lungs. 2nd ed; p. x, 509. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bernard C. New York: Dover Publications; 1957. An introduction to the study of experimental medicine; p. 208. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindsay JA. London: H K Lewis; 1923. Medical Axioms, aphorisms and clinical memoranda; pp. 1–9, 48. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moorhead TG. Remarks on hyperthyroidism. Irish J Med Sci. 1923;82:107–21. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Garrison FH. Medical proverbs, aphorisms and epigrams. Bull New York Acad Med. 1928;4:979–1005. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]